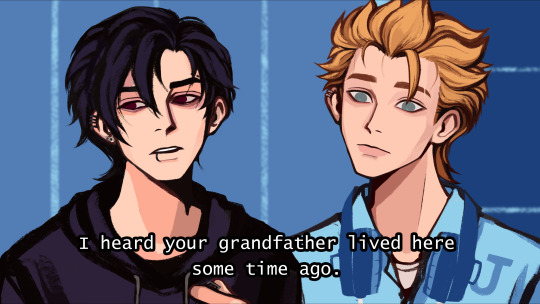

#to create a documentary about a newly opened location in a small town

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"can i ask YOU a question?"

[ jojamart mockumentary #15 ]

[ prev || next ]

#stardew valley#stardew valley fanart#sdv sebastian#sdv sam#jojamart mockumentary#my art#so this one was basically made to answer the question:#“where is the farmer during all of this?”#behind the camera of course#visiting pelican town as part of a company project#to create a documentary about a newly opened location in a small town#(you were the one to propose stardew valley)#also re: sebastian's eye color#i don't think any of his portraits/sprites have it#it's just the same color i use for maru

4K notes

·

View notes

Link

In 1997 the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) purchased Yin Yu Tang (Hall of Plentiful Shelter), a historic Huizhou residence in the town of Huang Cun in China's east-central Anhui Province. It then dismantled the structure, shipped it to the United States, and rebuilt it on the grounds of the museum in Salem, Massachusetts. The transplantation of Yin Yu Tang provides a unique vantage point from which to reconsider the appropriation of Chinese architectural heritage by institutions in the U.S. This article examines a series of issues related to the relocation and exhibition of Yin Yu Tang in a new geocultural context. It also looks into changes in Huang Cun in the aftermath of the Yin Yu Tang project to understand the challenges of heritage preservation in the Huizhou area.

Han Li. "Transplanting Yin Yu Tang to America: Preservation, Value, and Cultural Heritage." Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, Vol. 25, No. 2 (SPRING 2014), pp. 53-64.

Although Yin Yu Tang was not initially classified as a protected relic, its value certainly changed when PEM launched the Yin Yu Tang project. For the local authorities of Xiuning County, Yin Yu Tang went from being an ordinary old residence to being a symbol of Huizhou architectural heritage. Just as importantly, it provided an opportunity to con nect Xiuning with the rest of the world. In May 1997, when the Xiuning County Cultural Relics Administration and PEM agreed to transfer Yin Yu Tang to the museum, the nature of the transaction was therefore defined as a cultural exchange that would promote international awareness of traditional Huizhou heritage. As I will discuss, this transaction led to a series of follow-up activities between Salem and Xiuning County that had socioeconomic implications for both locales. These activities included publishing educational materials, hosting international forums, organizing and promoting a "Xiuning-Salem" tourist route, and supporting other conservation works in Huang Cun. For local officials in Xiuning, "exporting" Yin Yu Tang has proven to be more than just a cultural exchange; it has represented a significant political and economic achievement.

[...]

Conservation of the timber frame provides a good case in point. To strengthen the deteriorated pieces, architects called for supporting the original wood planks with new boards made from a species of American wood with similar character and strength. Thus, while the new planks provide structural support, the original planks retain their role in the structure's historic fabric. Appropriating the authority of native craftsmen is another strategy commonly used by American museums to construct a sense of authenticity for their Chinese structures.8 PEM invited Huizhou carpenters, masons, and other craftsmen to demonstrate and apply tradi tional techniques to the reconstruction of Yin Yu Tang, and, rather than using nails, components were connected using dovetail tenons, a traditional method of Chinese joinery. By deliberately foregrounding these activities in its documentary film about Yin Yu Tang, PEM was able to successfully con struct this aura of authenticity ( f i g . 3 ).

The roof was another feature of Yin Yu Tang that required a creative solution, since the house was moved from the relatively warm climate of eastern China to a coastal town in the northern U.S. To protect the interior of Yin Tang from harsh winter weather in its new location, a clear paneled skylight is lifted by crane onto the roof in the fall, and removed each spring. The clear shield enables natural daylight to permeate Yin Yu Tang's central courtyard all year round so visitors can appreciate it as the outdoor space it was designed to be. Other than its interior courtyard, Yin Yu Tang's unglazed ceramic roof tiles were also exposed to winter weather in its new location. In this case, the conservation team replaced the base tiles with more durable, newly manufactured ones, while retaining the original cap tiles. Thus, the original appearance of Yin Yu Tang's roof has been maintained while it has also been modified to withstand harsh new winter conditions.9

Along with these measures, new features ensuring visi tor safety and accessibility were needed to comply with Massa chusetts building codes. These include a comprehensive fire detection and suppression system, heating and ventilation for visitor comfort and building conservation, new plumbing for drainage and water supply for the two skywell pools, and wiring for lighting and other purposes. These new elements were installed in the most inconspicuous and reversible fash ion possible so as not to preclude future preservation efforts.10 Further, in order to meet seismic requirements, electrical conduits, mechanical ductwork, and piping were fabricated using structural-grade stainless steel.11 And thresholds were reinstalled with electric screw jacks to allow disabled visitors to access interior spaces, while preserving the original look of the house.12 All things considered, then, the Yin Yu Tang that now stands at PEM, with its "authentic" Huizhou char acteristics, is not simply a physical entity transported intact from Huang Cun. It is a living reflection of a particular un derstanding of Huizhou architectural heritage and a negotia tion with contemporary American culture to re-present this in a new physical environment.

[...]

A second issue with the comparative approach is that it creates an inherent paradox of "paralleling" and "othering." Studies of museums have consistently pointed out how the very act of juxtaposing two items "others" the differences between them with regard to race, gender, class, etc.17 Apart from the obvious parallels in terms of class and business activity between the owners of the two houses, the differences between them — e.g., the unique lives and careers of merchants in the East and West and the dramatic differences between their respective cultures and levels of economic prosperity — inevitably create the trap of "exoticizing" the other. Realistically, while visitors may appreciate the furnishings as well as the manners and domestic spatial politics in these two houses, how can their juxtaposition not result in "exoticizing" Yin Yu Tang as a representation of the East? Or is reckoning with the unavoidability of this dilemma the only solution? Interestingly, while each PEM docent infuses the tour with his or her own understanding and personality, the institutional agenda is also in a constant interplay with the individual craft of curation.

[...]

Traditional Huizhou dwellings resemble fortresses from the outside, with tall, solid, white washed walls and small windows for ventilation and safety. Closed to the outside and open to the inside, such a house stands as a self-sufficient microcosm Since the austere facade and white exterior walls do not immediately reveal as much about the house as do the pictures of the other three houses, PEM's choice to emphasize Yin Yu Tang's horsehead walls effectively heightens the importance of this characteristic feature of the Huizhou dwelling. The importance of the horsehead wall to Huizhou architecture is also demonstrated in a separate Yin Yu Tang brochure. Here the image of the whitewashed exterior not only stands alone as the signature element of Yin Yu Tang, but it provides a background for four other pictures ( r i g . 5 ). These show Huang Cun, an old photo of an earlier generation in the Huang family, the second story of the house structure, and the interior of one room. Together, these photos attempt to provide a snippet preview of the environment where Yin Yu Tang originated, of the Huang family, and of the architecture and everyday life of the house.

[...]

The carefully arranged self-guided house tour also high lights this intertwining of the micro (everyday practices) and macro (social-economic changes). The rooms and items that visitors see on this timed excursion integrate characteristics of Huizhou vernacular architecture and decorative art with Huang family history and a brief explication of China's nine teenth- and twentieth-century history. Also interesting is that while the owners of the other historic houses at PEM are long gone, leaving only their legacy for others to interpret, the previous inhabitants of Yin Yu Tang become co-curators of their lives. In other words, through the audio track that visi tors are provided, they become both the subject and medium of interpretation.

The description of the main hall is a telling example. When visitors arrive here, the audio track (with interpretive narration available in both English and Mandarin) includes the chanting of a memorial essay from an ancestral worship ritual and the simulated sound of daily activities such as peo ple chatting, moving around, and relaxing.2' Visitors are thus encouraged to see how the main hall served both as a solemn public place for important family rituals and a casual space for everyday activities. The main hall also contains items bearing the imprint of a particular era — a speaker used for broadcasting propaganda during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and the portrait of Lei Feng (1940-1962), a socialist soldier-hero — and these items are called out in the spoken narration. In addition to the explanations provided by PEM staff, the audio track contains the voices of Huang family members, who recount their memories. For instance, visitors hear Huang Xiqi's personal recollections of childhood in this room, adding a layer of miscellaneous sensibility to the grand narrative.

Such stories combine personal and private family memo ries with the collective memory of cultural and social values to demonstrate the perennial yet changing roles of the main reception room. Indeed, throughout the self-guided tour of selected rooms and household items, PEM helps visitors experience the physical space of Yin Yu Tang, imagine quo tidian life there, and understand the ethics and social and cultural values behind the lives of Huang family members over time.14

The various genres and means through which PEM has restored and reimagined the Huang family's domestic life and its interaction with larger historical events ultimately transform Yin Yu Tang from a singular dwelling into a matrix of living scholarship of Huizhou architectural, cultural and social legacies. The interpretations integrate powerful and compelling micro and macro views from the past. They also reveal the gaps and fissures in the narratives surround ing otherwise homogeneous and timeless "heritage." Together, such efforts provide a panoramic view of the architecture, inhabitants and heirlooms in the house over the course of several generations. However, this has only been made possible by stripping the house of its original social context and transforming it into an object in a museum, exposed to the gaze of outsiders. Yin Yu Tang's history, constructed through interpretative narratives, is thus presented as a "lived" his tory that conforms to the established grand historiography of twentieth-century Chinese history. This naturally differs from the preservation of "living" history in Yin Yu Tang's home region, Huizhou. In particular, the deliberately choreographed traditional ceremonies included in explications of the house are imbued with an ersatz performative aura bespeaking the fact that the authenticity PEM constructs is actually a perfect simulation.

2 notes

·

View notes