#to ethnic boundary maintenance theory

Text

multidisciplinary fields i love you

#going from reading hard science isotopic studies#to ethnic boundary maintenance theory#to labour and capitalism#to the hierarchical intimacies of the senses#sometimes i get so stressed about deadlines i forget that this is actually fun and interesting#archaeology :)))#like yes tilley i know youre talking about phenomenology but talking about how taste is the most intimate of the senses because#it requires taking things into your own body#vs sight which is the most distanced and is basically just remote sensing and therefore less intimate#like.... alright king let me use my academics for my art#To be a good phenomenologist is to try to develop an intimacy of contact with the landscape akin to that between lovers. like okay......

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

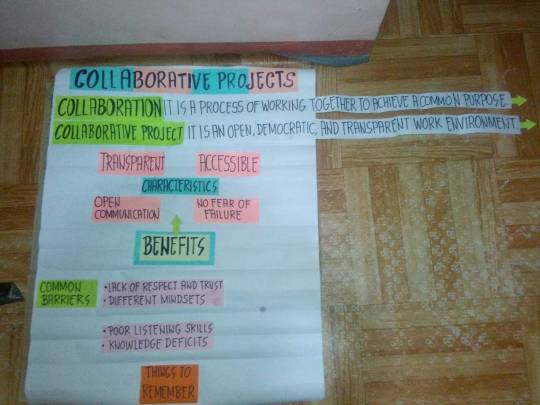

COLLABORATIVE PROJECT

Collaboration is the act or process of working together with other people or organizations to achieve a common purpose such as creating something or pursuing an intellectual endeavor. Thus, collaboration requires a cohesive team to follow a common process in working toward a shared goal.

Collaborative work or project means an open, transparent, and democratic work environment where all projects participants have access to the entire projects information at any time and from anywhere.

Characteristics of Collaborative Project

1. The work is open and transparent to everyone in the project

The project scope and the goals are known to all project participants.

2. Everyone in the project has access to the same data at anytime from anywhere.

Everyone can contribute to every part of the project. There are no boundaries on contributing and discussing ideas.

3. The project has open communication channels for all. Managers and contributors communicate and collaborate freely.

All ideas are heard and discussed without the fear of ridicule or put down.

No idea is deemed crazy; every idea is checked and discussed.

4. There is no fear of failure, people are encouraged to take risks and work on new ideas.

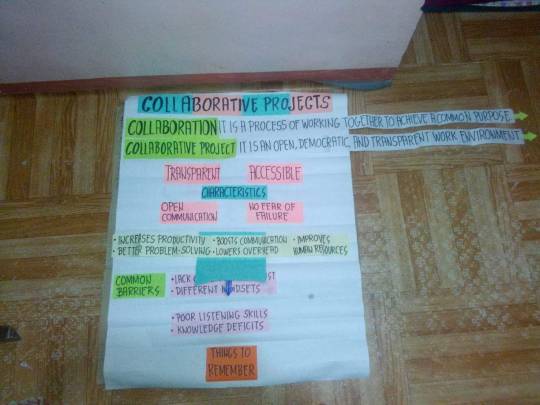

Benefits of Collaboration

Increases productivity

By distributing tasks to team members, who have the time and skills to complete them, rather than burdening one team member with too much work and neglecting others, you work more efficiently.

Better Problem-Solving

Giving team members the autonomy to work together to solve problems offers more avenues to success, as well as building team loyalty and morale.

Boosts Communication

The lines of communication need constant maintenance or misdirection can sidetrack a project. Collaboration facilitates clear communication and provides a solution to communicate effectively among even remote teams.

Lowers Overhead

One of the bigger costs in any organization is renting or buying a physical space in which everyone can work. With collaboration, however, team members dont need to be in the same place.

Improves Human Resources

By fostering collaboration between your team members youre not only building relationships but creating loyalty that helps with employee retention.

Common Barriers to Collaboration

A lack of respect and trust

Successful interpersonal relationships and, thus, the ability to collaborate effectively require mutual trust and respect. In todays diverse workplaces, trust and respect are vital. However, people sometimes lack respect for others who are different from themwhether because of differences in age, gender, race, or ethnicity.

Different mindsets

Diversity of viewpoint is an asset for collaborative teams. People with different perspectives see different dimensions of the problems teams are trying to solve and come up with unique solutions for them. However, diverse mindsets can also present challenges to teams. Our psychological types, needs, power bases, conflict styles, and stress quotients differ, leaving us open to potential misunderstandings.

Poor listening skills

The key to good communication is the ability to listen wellaccurately receiving and interpreting what people sayand good communication is an essential element of collaboration. However, there may still be some team members with big egos who dont really value the opinions of their peers and, thus, may be unwilling to listen to others.

Knowledge deficits

Knowledge deficits can negatively impact teams ability to collaborative effectively. Because teammates lack a common frame of reference, they may have difficulty understanding how best to communicate effectively and work well together.

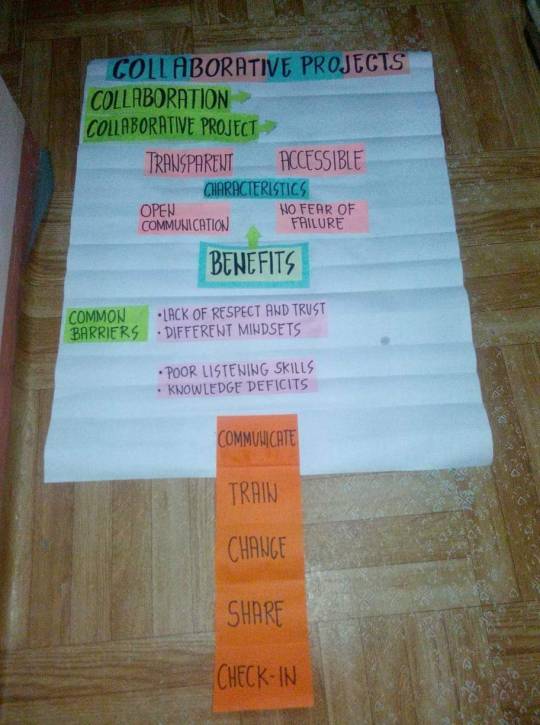

Things to Remember that will Give Collaboration a Healthy Start

Communicate

Good communication is the foundation of everything, so it goes with installing a collaborative environment.

Train

Set up a training session for the team.

Change

The team needs to move away from old methods of communications, like emails, and get comfortable with more interactive and collaborative communications.

Share

Break down the virtual walls that have separated team members.

Check-in

The team must monitor the projects and have regular meetings to track the progress of the project.

Collaborative Project-Based Learning

It is an instructional method based on constructivist learning theory, in which learners work on an authentic, ill- defined project in a group and demonstrate their understanding by performing the project. In CPBL, learners constantly involve in problem solving in which they apply their content knowledge to address real-world issues.

Collaborative Problem-Based learning

It is a student-centered pedagogy in which students learn about a subject through the experience of solving an open-ended problem found in trigger material. The PBL process does not focus on problem solving with a defined solution, but it allows for the development of other desirable skills and attributes. This includes knowledge acquisition, enhanced group collaboration and communication.

Online Collaborative Space

Wikis

It allows researchers to share data files, edit documents, and discuss content. The online collaborative space serves as a central location for research documents, so individuals no longer need to clog their email inboxes with large data files or wonder if the file they're working on is the most recent version. Researchers can work together to build and share collections of internet links, citations, and articles.

REERENCES:

Robins D. (2018) Collaborative Project Management Explained. Retrieved from https://www.binfire.com

Landau P. (2016) What is Project Collaboration. Retrieved from https://www.projectmanager.com

Pabini G. (2017) Overcoming Common Barriers To Collaboration. Retrieved from

https://www.uxmatters.c

1 note

·

View note

Text

Notes on Labor, Maternity, and the Institution

March 9, 2011

by Jaleh Mansoor

I.

Pro labor activism will not begin to overcome the injustices and indignities it purports to redress until it addresses an irreducibly (for now) gendered form of labor: labor, as in, going into labor, giving birth (or adopting). While much recent discourse attempts to account for the industrial or “fordist” to post-industrial shift in forms of labor, patterns into which workers are set, employment, and unemployment (I am thinking of the Italian Autonomist Marxists and Virno, Negri and Hardt in particular), and while so many statistics tell us that more women are in the workforce than men (in the aftermath of the economic crisis of 2008 to the present), maternity is scotomized. Is this just another not-so-subtle form of gynophobia? A fear on the part of feminists of essentialism? A critique of the emphasis French Feminists of the 70s placed on maternity? An innocent oversight in recent iterations of Marxist analyses?

Artistic practices of the last decade highlight the remunerative system of a global service industry, one in which “art” takes its place fully embedded in–rather than at an interval of either autonomy or imminence–the fluid, continuous circulation of goods and services: Andrea Fraser’s Untitled (2002) in which Fraser had her gallery, Friedrich Petzel, arrange to have a collector purchase her sexual services for one night, Santiago Sierra’s 250 cm Line Tattooed on Six Paid People (1999) in which the artist paid six unemployed men in Old Havana, Cuba thirty dollars each to have a line tattooed across their back. Fraser’s work was characteristically “controversial” in the most rehearsed ways, and Sierra’s drew criticism for having permanently disfigured six human beings. The misprision and naivete of the critics spectacularized both, of course. Sierra’s retort involved a set of references to global economic conditions that the critics may not have liked to hear: “The tattoo is not the problem. The problem is the existence of social conditions that allow me to make this work. You could make this tattooed line a kilometer long, using thousands and thousands of willing people.”1 Both Fraser and Sierra point to the quasi-universality of what autonomist Marxist theorist Paolo Virno calls a “post-fordist” regime of “intellectual labor” to describe the shift from the assembly line to a wide range of labor in which traditional boundaries and borders no longer apply. Virno says, “By post-Fordism, I mean instead a set of characteristics that are related to the entire contemporary workforce, including fruit pickers and the poorest of immigrants.”2 This post-fordist regime is characterized by flexibility, deracination, and the shift from habituated work to contingency. Concomitantly, the post-fordist laborer does not take his or her place in the ranks of he masses, but flows into a multitude, differentiated by numerous factors, among them, post-coloniality, endless permutations at the level of gender, ethnicity, race.

For Virno and the autonomists, art and culture are no longer instantiations of exemplarity and exceptionality, as for Adorno, but rather “are the place in which praxis reflects on itself and results in self-representation.” In other words, the cultural work operates as a supplement, a parergonal addition to an already existing logic. It neither passively reflects nor openly resists. There is no vantage or “outside” from which art could dialectically reflect and resists, as Adorno would have it. Long since the work came off its pedestal and out of its frame, from the gallery to the street, the ostensibly non-site to the site as Robert Smithson put it, cultural production is too embedded in social and economic circulation to reflect let alone critique. Virno sees this limitation—the absence of an outside—as one shared with that of activism and other forms of tactical resistance: “The impasse that seizes the global movement comes from its inherent implication in the modes of production. Not from its estrangement or marginality, as some people think.”3 Ironically, the luxury of estrangement and marginalization enjoyed by the avant-garde and neo avant-garde is no longer available.And yet, it is “precisely because, rather than in spite, of this fact that it presents itself on the public scene as an ethical movement.”4 For if work puts life itself to work, dissolving boundaries between labor and leisure, rest and work, any action against it occupies the same fabric.

Among others, a problem that surfaces [too quietly and too politely, with a kind of ashamed and embarrassed reserve] is that of gender. The issue is not merely that Fraser puts her body at risk while Sierra remunerates others to place at risk, and in pain, their bodies, that corpus on which habeus corpus is founded. Needless to say, Sierra has organized projects around male prostitutes, such as that of 160 cm Line Tattooed on Four People, executed for the contemporary art museum in Salamanca, Spain, in 1999.

The problem is that the category of disembodied labor, or intellectual labor as Virno alternately calls it to describe its reliance on abstraction, scotomizes a form of irreducibly gendered embodied labor: labor. Now let the cries of essentialism! ring. Where is Julia Kristeva when you need her? Hélène Cixous telling us to allegorically write with our breast milk?5

Many feminist artists of the 1970s—in a historical moment that has both formed and been occluded by the artistic pratices of the last decade which I mention above–explicitly addressed the category of unremunerated labor: Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1973-4), for instance; Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman which explicitly draws an analogy between house-work and prostitution. Mary Kelly’s Post Partum Document (1979) elevates maternity to the level of analytical research, part of the putative archival impulse. Merle Laderman Ukeles tacitly situates domestic work in a category with the service industry understood historically, before all labor became maintenance labor, as “maintenance.”6 Ukeles’s differentiation of production and maintenance almost seems romantic in hindsight. As though there were creation/production rather than reproduction. And yet…..

Radical Marxist and feminist activist Silvia Federici, author of Genoa and the Anti Globalization Movement (2001) andPrecarious Labor: A Feminist Viewpoint (2008) argues against the gender neutrality of precarious labor theory, that of the Marxist autonomists Paolo Virno and Antonio Negri.7 Federici situates the commonality of rape and prostitution as well as violence against women within a systematized appropriation of female labor that operates as accumulation, much as accumulation did atavistically, long before the formation of commodity economies, or the development of general equivalence. Atavism as a repressed matrix for putative modernity—a modernity in which gender determination describes one of the greatest forms of uneven development—supports Ariella Azoulay’s claim, in The Civil Contract of Photography, that modernity did little to alter women’s positions in relation to discourse, the institution, and civil rights greater than the vote. Just as for Foucault the modern biopolitical regime compounds the old to achieve a more thorough penetration of everyday life, modernity permutes previous hegemonies “shaped and institutionalized over thousands of years.” In twentieth-century battles for the right to corporeal self-determination, to reproductive rights, for instance, “the body itself underwent a process of secularization, …this body came into the world without any of the normative defenses of citizenship to regulate it.”8 Under “Universal” rights, the contingencies of the body, deemed particular, did not become part of the discourse around citizenship, thus abandoning it to a renaturalized precariousness. Premised on a set of Enlightenment Universalist claims purportedly neutral to the particularities of corporeality, modernity failed to account for the specificities of women’s lives. Instead, the body, or “bare life” tacitly continues to be the way women are viewed, here commodified and sexually fetishized (neo-liberal “Western” democracies), there regulated within disciplinary, and often violent, parameters, as in Islamist cultures.9 These differences in hegemonic models of femininity may be theorized;10 the process of biological labor, however, slips the grasp of discourse, and, with it, policy. This last term would include international policies in which Enlightened self-interest are legitimated by the roles of women, of women’s bodies to be more precise.

Federici links her notion of atavistic forms of reserve—the accumulation of women’s labor—to colonial expropriation. She argues that the IMF, World Bank and other proxy institutions as engaging in a renewed cycle of primitive accumulation, by which everything held in common from water to seeds, to our genetic code become privatized in what amounts to a new round of enclosures.

Pop culture, as always a place where cultural articulations happen within normative parameters that may differ from “discourse,” presents the most direct expression of this that I have yet to come across. The high/low binary was a false product of fordism, one that no longer operates. When a famous male rapper says, “gonna get a child outta her,” he is speaking hegemony, not “marginalization.”

II.

Labor: If Virno is “correct,” in his analysis, there can be no “perspective” from which to think labor. From what fold within labor might I think it? I’ve worked as an hourly wage earner, a mother, and a salaried “professional.” One of these three terms is incongruous; discourse has hit a false note. My description of something about which I should know a great deal, my own history as a laborer, has already committed a rather egregious crime according to the law of discourse. As De Man has famously said, “abuse of language is, of course, itself the name of a trope: catachresis. …something monstrous lurks in the most innocent of catachreses: when one speaks of the legs of a table or the face of a mountain, catachresis is already turning into prosopopeia and one begins to perceive a world of potential ghosts and monsters.” What thwarted terms, or monsters, are barred from an account of my accounts? Discourse be damned, or in this case, personified; I am using “I.”

At 13, 22 years ago, I was what Siegfred Kracauer might have referred to as “a little shop girl,” working at a T shirt store for 3.75 an hour, selling 20 dollar Joy Division T-shirts and 5 dollar Grateful Dead stickers to other, older, teenagers [with allowances or their own jobs]. My mom had to accompany me to the first day to make good on PA labor laws. 7 hours of my labor/boredom would have bought me one of the T-shirts I sold. I’ve worked, like so many artists and academics, as a museum guard, 17 years ago, for 7/hr, or 10.50/hr for working past the 8-hour shift. Needless to say, none of these jobs had benefits. I’ve written articles for prominent scholarly journals where the pay may roughly be calculated at 3 cents/word, 1 percent of what a glossy magazine would pay for non-scholarly work. Let’s not get distracted by the amount of time that scholarship requires: travel; archives; dozens if not hundreds of books read; writing; and editing. But that “let’s not” is a sliding glass door of sorts: it articulates the injustice of unremunerated work, but it also stands as a reminder that the pleasure [and/or displeasure] of some work is irreducible to money, acts as an irreducible quality. But isn’t everything held in the matrix of currency [fiction]? All process, a term inclusive of work, skilled or unskilled, is irreducible to the monetary value assigned it. A bibliography supportive of that last statement alone would entail a foray into a discursive terrain bordered by Vico, Marx, Weber, The Frankfurt School, Foucault, Post Structuralism and practically every title in Verso, Stanford’s Crossing the Meridian and the University of Minnesota press, and the work of countless others. Irreducible labor. Or as Thomas Keenan has recently put it, the irreducible “jelly” of work that remains after the abstractions of exchange value is “accounted.”11

I’ve worked for 19 thousand a year as a gallery receptionist 14 years ago; for nothing, in monetary terms, writing a proto-book as a PhD candidate to produce a dissertation, partially about labor and art in reconstruction era Italy; for a stipend of 18 thousand per annum teaching college students courses that full [celebrity] professors were also teaching; for one glorious year at 55+ thousand a year as a “term” assistant professor at a prominent women’s college affiliated with an ivy league university; and some ten k (+) less a year as a tenure track assistant professor at a state institution. The latter ostensibly includes compensation for teaching Art History to undergraduates and studio practitioners, directing advises toward theirs MAs or MFAs, and coming to countless faculty meetings. I can retain that salaried position if I produce enough of those journal articles, at 3 cents a word, so let us include the latter, now that I HAVE a tenure track position, in that before-taxes salary. And I get benefits. I am by all [ac]counts VERY lucky and yet the contradictions in the remunerative system are too many to count. I am not compensated in any way—including in University evaluations and other assorted forms of self-regulative beaurocracy—for the 5 or so, sometimes more, hour (+)-long studio visits I conduct every week. An aside on the studio visit: it is by far more intense than an equal measure of time, the hour, of teaching, advising, or any other form of labor but one. And that latter, around which I skirt, is a term from which I steal to work. “Robbing peter to pay Paul.” Wait, I thought I was the one getting paid?

And I “speak” from a vantage of extreme privilege, of multiple privileges, of all privileges but one, to which I stand in a relation of excess and lack. That excess and lack revolves a particular embodied form of labor, a production that is a non productive labor unlike the non accumulative labor of which the autonomists speak…

The discursively impossible: I have given birth through the labor process to a child. “Let’s not,” in the interest of not getting caught in the sliding glass door, “count” pregnancy, or post pardum recovery or breast-feeding. Let’s try to isolate labor in order to attempt to, tautologically, quantify it, as the issue of labor conventionally requires us to do. That labor was 32 hours long. Not one of those 32 hours was commensurable with any other hour. Time contracted, not necessarily in rhythm with those of my womb (hystery in Greek), time dilated, not necessarily in tandem with my cervix. It was working parallel to me; no, those organs were working in tension against me. Dissonance. I have never been capable of thinking my body’s labor in what I will call, despite the need to shore it up by the labor of discursive legitimation, my experiential time. This time shrank and stretched like hot taffy. I would need the proper name “Deleuze” here, and The Logic of Sense, to get the discursive sanction I need to support this last claim. That would take a little labor, labor time I could punch in as academics will no doubt do some time soon, or rather do now however elliptically in requisite annual self reports. But those 32 child labor hours defy break down into 32 units of 60 minutes, 1920 units of 60 seconds, etc. This form of labor slips the grip of discourse; even metaphor.

Catachresis is not monstrous enough to operate as a medium for the articulation of this [non] event. There was, however, a quantifyable cost for the hospital ante-chamber, the delivery room, the “recovery” room, and the first examination of the infant. And there were more complex “costs;” I was “let go” of the second year of my position as a term assistant professor at a prominent women’s college associated with an ivy-league university. The Chair responsible for my firing, I mean, liberation, is a “feminist,” and a mother of two. She thought it would be “for the best,” for me to have time off. I never asked for time off. This did allow her to win a point or two for her annual docket; I was hired back on the adjunct salary of 3 thousand per class the next semester. This allowed the department to save 50 thousand dollars in 2007-2008, and the cost of benefits. Did I mention that the semester after giving birth, after having been “let go,” I still made it to campus to attend all advising sessions? 50K in savings that the institution no doubt never even registered, my loss. But who cares, I had a healthy beautiful bright baby!….. to love AND support. BTW, diapers are 20/box. Currently, I calculate that I make about 12 dollars and fifty cents an hour given that I work at least sixty hours a week. Ergo, a box of diapers is equal to over an hour and a half of work. I go through many of these per month still. At the time of being fired/demoted/whatever, I lived in NYC, where diapers cost more than 20/box. And I made, about 4.16 and hour. A box of diapers cost 5 hours of work. But like many women, and unlike many others, I had assistance, that of a partner and that of a parent. Let’s not address the emotional and psychological cost of the latter; let’s please not address the price dignity paid. Oops, prosopopeia. Does dignity have agency? I hope the reader knows by now that I find calculations to be absurd. “How do I love Thee, [dear child, dear student, dear reader,] Let me count the ways….” I am, however, serious in the following query: how do others less lucky than I make it in the global service industry (in which education and so called higher education now takes it place, now that Professors at State schools are classified as mid level managers?) How do women who have babies and work make it? They pay to work; they pay with their children. Sacrificial economies.

Now again, let’s not get caught in that door by even discussing the 24/7 labor of parenting. The pleasures of this last, and the agonies, are irreducible. But, again, isn’t everything? So: Suspended. Bracketed, a priori. A discursive delimitation or repression? It is in such poor taste to discuss this: bad form. Just a note, daycare is 10 thousand dollars per anum. A baby sitter charges 10-15 an hour. I over identify with the sitter and guiltily–as though I even had the luxury of being a fat cat liberal riddled with guilt–pay said sitter 20. But no worries: I don’t believe in baby-sitting. I have no life outside of the working and the parenting, no leisure. I mistrust the latter. I dislike being appeased. No compensatory blah blah for me. I do, however, want the hours taken away from my child by studio visits and the like to be remunerated HER. She keeps track of when I am missing. I can’t keep count. Guilty interstitial pleasure: Facebook, whom (uh oh) I can credit for the honor [snarkery free] of labor on the present piece.

III.

Like most institutions of its kind, the University at which I have a tenure track position, for which I am reminded to be eternally thankful—and I AM—does not have maternity leave. Were I to choose to have a second child (this statement requires an exegesis into the word “choice”), I would take sick-leave, as though giving-birth were an illness; as though [biological] labor were a subtraction from the forward march of time, of production and productivity, of progress. Sick-leave, time taken while ill ad ostensibly unproductive. Sick leave, the concept if not the necessary practice, is sick. More perverse still is the idea that populating the next generation, however selfish this may or may not be in many way, however narcissistic or not, is not a form of non-productivity. The double negative in this last should raise some flags in the space of textual analysis, labor analysis, gender analysis. An aside: I never felt less ill than during pregnancy, childbirth, and so called recovery. The use of the word biology will deliver the present text, again, to the accusation of essentialism. I will add that it goes without saying that maternity need not be biological. But it is still labor. A colleague recently adopted a child. Said colleague travelled to a distant continent to retrieve the child with whom she had spent a year establishing an intimate, if painfully digitally mediated, long term relationship. She took family medical (sick) leave. It, apparently, is against an ethics of work to be preoccupied with a new baby.

Moreover, were I to have a second child, my tenure clock would stop if I took that odiously named family/sick leave. My opportunity to make a case for my own worth via tenure review would be deferred. Of course, were we unionized, there may be a fighting chance, were our esteemed male colleagues to support us, for maternity leave, or, more unthinkably, paid maternity leave and no punitive tenure clock [beyond the normative punitive parameters]. “We” are our worst obstacle. As a prominent political science academic and feminist recently pointed out to me, one of the greatest obstacles to unionization or any form of collectivization, for artists and academics, is that they think of themselves as “professionals” and associate unions with blue color workers. Were they to peek around, they would note that these workers are practically extinct. We are all in an endless lateral plane of service. As one student told me, “my parents pay your salary,” to which I responded, “like the cleaning lady.” Note that there is no “liberal elitism” lurking here. We are all, to some extent, unless we work for JPMorgan Chase or some hedge fund, the cleaning lady (many nannies, like many cabbies, have a string of PhDs. My republican aunt once told me with delight that her cleaning lady had worked with my dissertation adviser when she, “the cleaning lady” was in grad school). Anyway, the student just nodded. I told him he should work to get his parents’ money’s worth.

Professors and academics like to think that they transcend as they were believed to do in a previous disciplinary socio-cultural regime. Jackson Pollock thought that too. He was an easy puppet in Cold War politics. Teaching undergrads in a core curriculum of an ivy league university that shores its superiority and identity around said core curriculum of old master literature, art and music—in other words, utterly dependent on a labor pool of graduate students—I participated in the effort to unionize. The threats were not subtle. The University’s counter argument was that students study; they don’t labor.

And women work, they don’t labor. There is no language.

1 Marc Spiegler. “When Human Beings are the Canvas.” Art News. June, 2003.

2 Interview with Paolo Virno. Branden W. Joseph, , Alessia Ricciardi trans. Grey Room No. 21 (Fall 2005): 26-37.

3 Ibid. P. 35.

4 Ibid.

5 The Laugh of Medusa.

6 For an excellent panoramic overview of these practices, see Helen Molesworth. “House Work and Art Work.” October No. 92 (Spring 2000).

7 Reprinted in Occupy Everything January 2011. http://occupyeverything.com/news/precarious-labor-a-feminist-viewpoint/

8 Ariella Azoulay. The Civil Contract Of Photography. New York: Zone Books, 2008. P. 226.

9 Ibid. For a discussion of the blind spot of sexuality and embodiment in Enlightenment thinking, see Jacques Lacan’s “seminal” “Kant with Sade.” Critique (April, 1963).

10 “Nothing, we are told by Western Hegemonic discourse, so differentiates “us” from “them” as the lack of freedom for women in Islamist societies. It needs to be noted, however, that far from silencing the power of women, Islamist regimes highlight it, acknowledging through severe and violent restrictions that what women do is crucial to political and social order. The argument justifying the strict codes of conduct, based on respect for women (in contrast to the Western commodification of women and their disparagement as sex objects), has a dialectical dynamic that can lead to its own undoing.” Susan Buck-Morss. Thinking Past Terror. P. 12. London: Verso, 2003. P. 12.

11 Thomas Keenan. “The Point is to (Ex) Change It: Reading ‘Capital’ Rhetorically.” Fables of Responsibility. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2007.

0 notes

Text

Architecture in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union

2014

Kimberly E. Zarecor

Iowa State University, [email protected]

Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union are often associated with grey, anonymous, and poorly constructed post-war buildings. Despite this reputation, the regional architectural developments that produced these buildings are critical to understanding global paradigm shifts in architectural theory and practice in the last 50 years. The vast territory of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union covers about one-sixth of the world’s landmass and currently contains all or part of 30 countries. Since 1960 other national boundaries have existed in this space, including East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the Soviet Union. Given the region’s large size, numerous languages, and tumultuous recent history—communist and authoritarian regimes, democratic revolutions, civil war and ethnic strife, political corruption, prosperity, EU accession, and economic instability—a comprehensive summary of 50 years of architectural developments cannot be achieved in one chapter. Rather than survey individual architects or projects in depth, this chapter instead explores the shared transformation in architectural discourse and practice that resulted from the region’s political and economic shift to communism after World War II, and the changes that followed the fall of communism in the 1990s.

Countries include Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, East Germany (now considered Western European as part of a unified Germany), Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Architectural Practice during Communism

After World War II and the rise of Communist parties across the region, architects living in Eastern Europe and the new territories of the Soviet Union found themselves in a novel position. Unlike the lean years of the Great Depression in the 1930s, when most architects were left without work, they now had guaranteed employment and their services were in high demand for post-war reconstruction. Many were politically leftwing and supported the social agenda of the Communist Party, such as providing a minimum standard of housing for all citizens, whether or not they were party members. In territories that had been part of the Soviet Union before the war, architects also prospered due to the growth of the Soviet economy, a benefit of the expansion into Eastern Europe and the Baltics, and new investment in industrial infrastructure. Soon, however, the initial enthusiasm was tempered in Eastern Europe by the realization of the authoritarian nature of the regimes and the lack of professional freedom.

The professional lives of architects in communist economies differed significantly from the experiences of architects in capitalist countries. In this system, architects worked directly for the state or for state-owned enterprises; private practice was abolished. These changes first occurred in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and after World War II in Eastern Europe and the new Soviet territories. Communist economics relied on planning—the prediction of future input and output needs for all sectors, typically in a five-year increment called “the five-year plan.” This system relied on quantifiable targets and quotas, which forced architects to evaluate building projects in terms of material and labor costs—quantities of concrete and steel, number of units, volume of skilled and unskilled labor, and so forth. The experiential and formal aspects of architecture had no measurable value, and therefore had little relevance to design decision- making, except for one-off projects with political significance to the various regimes. As a result, architects across the region became technicians producing an industrial commodity, rather than creative artists executing an individual vision.

At the same time, and perhaps as a result, the social status of the architect diminished. Architects had once been at the center of the avant-garde (one can think of the Russian Constructivists and the Yugoslav Zenitists, as well as other groups such as Devě tsil in Czechoslovakia and Blok and Praesens in Poland), but during the communist period architects typically worked anonymously at state design offices where they functioned as engineers and managers more than designers. Those unwilling to accept new working conditions or unsuited to the professional environment took less visible positions at universities, historic preservation offices, archives, or consumer product enterprises such as furniture and industrial design companies. By the late 1960s, few practicing architects had any personal memory of architectural practice before World War II.

Because of this shared set of priorities emphasizing typification, standardization, and mass production, architectural practice across the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc shared more similarities than differences among the various countries by the 1950s. This represented a significant shift since Eastern Bloc countries like Czechoslovakia, East Germany, and Hungary had sophisticated building industries before World War II, while the construction sector in the Soviet Union had been underdeveloped and largely unmechanized. New methods and processes for design, finance, and building construction were developed and shared between professionals in the various countries, often through travel exchanges and research visits. These architects also shared the everyday economic realities of communism: unyielding labor and material shortages; the push toward faster and cheaper construction methods; and the lack of long-term investment in public space and building maintenance. As János Kornai and others have noted, shortage was the system’s defining characteristic. Therefore, as in other sectors, architects focused on strategies to address the problems including prefabricated building elements, lightweight building materials, and the mechanization of work on building sites.

The consistency of architectural strategies across the region was remarkable both for the discipline that the economic model imposed on production and for the scale of construction (over 50 million standardized housing units were constructed in the Soviet Union alone from 1957 to 1984). Manufacturing and distribution were streamlined to such a degree that one was likely to find the same building and hardware components across large swathes of the region.

Stephen Kotkin, author of two books on the Soviet steel city of Magnitogorsk, writes this about the general conditions:

The Soviet phenomenon created a deeply unified material culture. I am thinking not just of the cheap track suits worn by seemingly every male in Uzbekistan or Bulgaria, Ukraine or Mongolia. Consider the children’s playgrounds in those places, erected over the same cracked concrete panel surfaces and with the same twisted metal piping—all made at the same factories, to uniform codes. This was also true of apartment buildings (outside and inside), schools, indeed entire cities, even villages. Despite some folk ornamentation here and there (Islamic flourishes on prefab concrete panels for a few apartment complexes in Kazan or Baku) a traveler encounters identical designs and materials.

R.A. French and F.E. Ian Hamilton made similar observations in their 1979 book, The Socialist City: Spatial Structure and Urban Policy, writing that “if one were transported into any residential area built since the Second World War in the socialist countries, it would be easier at first glance to tell when it was constructed than to determine in which country it was.”

This stress on sameness was also ideological, since the communist ethos of a minimum standard for all was integral to thinking about designing cities with undifferentiated class structures. Housing was the most indicative of this approach as a homogeneous housing stock of mainly two- and three-room apartments was built from East Germany to the Soviet Far East. The resulting buildings were not valued as architectural objects, but rather as indicators of production performance. Meeting quantitative targets was more important than evaluating what had been produced, thus removing any incentive to improve architecture on aesthetic or functional grounds. Mark B. Smith writes that “to some extent, this [mass-produced similitude] was the end of architecture” and “the final takeover of the profession by construction experts.”9 After decades of conforming to this system, Polish architect Maciej Krasiński had this to say in 1988, “the Polish architecture of the present is bad ... The idea of “maintaining a building” both as regards its function and its technological state practically is non-existent, and if here we add, to put it gently—the hopeless quality of the work—then the general picture provides us with no reason for optimism.”

This sentiment was widespread in the Communist Bloc, particularly in the 1980s, when economic and political crises led to even more acute material and labor shortages and worsening construction quality. The building technologies and construction practices developed for prefabrication and panel construction in the 1960s had not changed much by 1989. Economic planning in multi-year increments slowed down processes of change and innovation. Given the myriad architectural developments in the capitalist West in the same decades, this stagnation and failure to keep up with international standards became more apparent with each passing year.

Design Culture in Communist Europe

From the perspective of architectural form making, the buildings of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, have their origins in earlier struggles to find an appropriate architectural language for the “ideal” communist society. The Russian avant-garde provided the first images of the potential for communist architecture in the 1920s, but the style was later denounced as “bourgeois formalism,” and replaced in the Soviet Union by historicist Socialist Realism after 1933. Eastern European architects, many of whom had been trained and practiced as modernists in the interwar period, faced a similar crisis when pressure mounted in the late 1940s to embrace the principles of Socialist Realism to symbolize their countries’ new affiliations with the Soviet Union. The necessity to work in a Socialist Realist style was short-lived, however. After Stalin’s death in 1953 and Khrushchev’s 1954 call to reject Stalinist aesthetics and “useless things in architecture,” Socialist Realism quickly receded.11

Khrushchev’s “thaw” followed—the liberalization of the most repressive policies of Stalinism in politics, culture, and everyday life. With this change to official discourse, architects

5

were able to return to avant-garde forms from the 1920s and re-embrace the Constructivist legacy. A highlight from this period was Expo ’58 in Brussels when the Soviet, Czechoslovak, Hungarian, and Yugoslav pavilions showcased an unexpected new communist style expressed in glass, concrete, and steel. The change was striking to many given how recently the region had been associated with Socialist Realism with its monumental scale and opaque materiality. This new version of modernism was not a reimagining of post-war practice as something akin to the interwar years, but rather a revival of forms and concepts that had figured prominently in avant-garde circles such as functionalism, mass production, and prefabrication, now deployed in support of the communist system by architects working for state design institutes. (Figure 13.1) 13.1 Vjenceslav Richter, Pavilion of Yugoslavia at EXPO ’58, Brussels, 1958. (Photo: Archive of Yugoslavia in Belgrade)

In these years, architects once again adopted an internationalist perspective that sought out universal, rather than regional or national, principles for modern architecture including standardized building types and industrial building methods. This transformation occurred in many countries outside the Soviet Bloc, notably in Western Europe, but on a much more limited scale. Virág Molnár writes that by the early 1960s, Hungarian “architects were ready to accept their subjugation to industrialized mass production because they envisaged state socialism as an alternative route to modernity.”12 In fact, Western ideas about architecture and urban planning, particularly those derived from CIAM and Le Corbusier, were widely promoted and implemented by architects and planners working in communist countries. Exemplary manifestations of tower in the park urbanism and zoned cities can be found throughout the region. (Figure 13.2) As James Scott discusses in his book, Seeing like a State, this was part of the global phenomenon of post-war high-modernist city building, examples of which were found in capitalist and communist countries, and in developed and developing economies.13

6

13.2 Tower in the Park Urbanism in Bucharest, Romania. (Photo: Arhitectura 4 (1966): 31)

Architects in communist countries, however, had no choice about the direction of their work. The generation whose careers started around 1960 had few opportunities to challenge a consistent and systemic preference for typified, standardized, and mass-produced buildings. Prefabricated concrete—used for structural elements, facade panels, and exterior landscaping—was the primary building material available for the majority of projects, forcing architects to find creative ways to work with its limitations. Other components, such as windows, doors, and fixtures, were industrially produced in mass quantities, and in limited sizes and finishes, adding to the repetitive and uniform nature of the environment. Concrete facades were often left grey and undecorated, although better examples incorporated colored panels or carefully detailed window assemblies. For new housing developments in many countries, a portion of the budget had to be spent on public art, thus fountains, sculptures, and murals, often made of concrete and tile, were common elements in public spaces.14 Unfortunately these attempts to beautify neighborhoods were undermined in many cases by poor workmanship during construction and a total lack of maintenance in subsequent years that hastened deterioration.

Despite these challenges, there are many examples of good design work executed in communist Europe, although the architects themselves remain largely unknown. Rather than radically departing from conventions or expectations, these projects succeeded by using a restricted palette of building elements and materials in exciting and novel ways. Noteworthy examples in the Soviet Union include the Palace of Sports in Minsk by Sergey Filimonov and Valentin Malyshev from 1966; the Lenin Museum (now the Museum of the History of Uzbekistan) by V. Muratov in Tashkent from 1970; the Cinema Hall “Rossia” in Yerevan, Armenia by Artur Tarkhanyan, Grachya Pogosyan, and Spartak Khachikyan from 1975; as well

7

as the venues built for the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games which included the Dynamo Sports Palace and the Druzhba Multipurpose Arena (Figures 13.3–13.4).

13.3 Sergey Filimonov and Valentin Malyshev, Palace of Sports, Minsk, Belarus, 1966. (Photo: © Hanna Zelenko / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL)

13.4 V. Muratov, Lenin Museum (now the Museum of the History of Uzbekistan), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 1970. (Photo: © Stefan Munder / Flickr / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL)

In Eastern Europe, the reliance on prefabricated and standard elements was just as fundamental. A few representative examples are the Spodek Stadium in Katowice, Poland by Maciej Gintowt and Maciej Krasiń ski from 1960; Przyczółek Grochowski housing estate in Warsaw by Oskar Hansen from 1963; the Federal Assembly of Czechoslovakia in Prague by Karel Prager from 1966; the Czechoslovak Radio Building (now the Slovak Radio Building) in Bratislava by Štefan Svetko, Štefan Ď urkovičč and Barnabáš Kissling from 1967; the National Gallery in Bratislava by Vladimir Dě dečč ek from 1969; the Palace of Culture in Dresden by Wolfgang Hänsch and Herbert Löschau from 1969; and Republic Square in Ljubljana by Edvard Ravnikar from 1977 (Figures 13.5–13.6).

13.5 Spodek Multipurpose Sports Arena, Katowice, Poland, 1960. (Photo: © Jan Mehlich / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL)

13.6 Štefan Svetko, Štefan Ď urkovičč and Barnabáš Kissling, Czechoslovak Radio Building (now the Slovak Radio Building), Bratislava, Slovakia, 1967. (Photo: Kimberly Elman Zarecor)

In terms of square meters, the design of housing and community buildings in new neighborhoods dominated architectural practice in this period. The planned economy

8

fundamentally changed approaches to housing design and construction as repeated apartment buildings organized in large districts replaced virtually all other residential types in most countries.15 Starting in the early 1970s, when the regimes finally acknowledged their collective failure to adequately raise living standards for the majority of residents, these new methods were deployed on a massive scale. In cities and towns across the region, low-cost prefabricated apartment towers sprung up creating whole new urban districts, and even new cities (Figure 13.7). In Bratislava, for example, more than 90 percent of the city’s 430,000 residents lived in post-war industrialized housing by the late 1980s.16 In the Soviet case, whole post-war cities, such as the 1960s-era car-manufacturing city of Togliatti, were built with prefabricated concrete.17

13.7 Housing Estate in Bratislava, Slovakia. (Photo: Kimberly Elman Zarecor)

A small intellectual class of architects rebelled against this standardization, and instead turned toward postmodernism and High-Tech in the 1970s and 1980s. They knew of these developments through architectural journals, either smuggled into the countries or available in the libraries of the state design institutes. The work of the Czechoslovak SIAL group (The Association of Engineers and Architects of Liberec) is one example. Following the Prague Spring in 1968, Karel Hubáč ek and Miroslav Masák, from the state-run design office in Liberec, established an independent design studio and began to train young architects. They called their operation the SIAL Kindergarten (SIAL-Školka). The studio’s work coupled the legacy of the avant-garde in central Europe with an interest in contemporary British High-Tech and engineered buildings. Hubáč ek’s own science-fiction-inspired Ještě d Hotel and Television Transmitter won the 1969 Perret Prize, awarded by the International Union of Architects (UIA) for its application of architectural technology (Figure 13.8). In the aftermath of the Soviet invasion in 1968 and the “normalization” period that followed, SIAL lost its independence and again became part of the state-run system in Liberec in 1971. But its architects continued

9

working and a group from the SIAL Kindergarten won the competition for the now iconic Máj Department Store in the center of Prague in the early 1970s.18

13.8 Karel Hubáč ek, Hotel and Television Transmitter, Ještě d Mountain near Liberec, Czech Republic. (Photo: © Ondř ej Žváčč ek / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL)

Unlike SIAL, which operated publicly and with state consent, many architects who wanted to challenge the official discourse were forced into secrecy. Ines Weizman writes about East German and Soviet architects who gathered in private apartments to discuss magazines illicitly brought into the country and to prepare competition designs that would then be smuggled to the West or sent to international architecture competitions, such as those sponsored by the Japanese journals, Japan Architect and Architecture and Urbanism (A + U).19 She positions these practices within the culture of dissidence, more often associated with literature and music, which was a critical development in establishing a theoretical basis for intellectuals’ opposition to the regimes in the 1970s and 1980s. Depending on the local political situation in their respective countries, these “dissident” architects were subject to various levels of retribution for their lack of cooperation. Some like John Eisler from SIAL went into exile in the West, while others, like Imre Makovec in Hungary, were forced to live in rural isolation. In extreme cases, architects, including Maks Velo from Albania, and Christian Enzmann and Bernd Ettel in East Germany, were imprisoned for their perceived architectural actions against the regime (Figure 13.9).20

13.9 Maks Velo, Apartment Building, Tirana, Albania, 1971. (Photo: Elidor Mëhilli) Architecture after Communism

This was the state of things in the late 1980s when the various regimes began to fall. By the early 1990s, the European communist experiment was over and countries went through a period of turbulent change, including the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the

10

Soviet Union, as well as vast transfers of state wealth into the hands of individuals through privatization programs. The architectural profession, centered for more than 40 years around a system of state-run design offices, had to be reinvented.

The transition was both conceptual and practical. Architects went from salaried employment in large public offices with regimented cultures to the capitalist model of private practice. Architects now had to find clients and financial backing for projects on their own, but they gained creative and conceptual freedom. The lack of intellectual rigor that characterized the state design system also had to be overcome. A high level of architectural discourse emerged into this void, particularly in Eastern Europe where many theorists and designers had continued writing in the communist period. Professional organizations and cultural institutions continued, active galleries and ambitious publishers dedicated to architecture appeared and numerous online venues for disseminating information sprung up in regional languages. All of which created a fertile intellectual context for the profession to make the difficult transition into the capitalist system.

Once the political and professional situation stabilized in the early 1990s, domestic and foreign investors were eager to tap into the region’s appetite for new buildings, especially in large cities like Budapest, Moscow, Prague, and Warsaw. By the early 2000s, this demand even reached smaller cities in less developed regions, like Baku in Azerbaijan, Bucharest in Romania, and Kiev in Ukraine, making this a truly region-wide phenomenon, except perhaps east of Moscow where the financial and social situation remained difficult.

In terms of building typologies, production since the early 1990s has focused on types neglected in the communist period or which never existed at all in the region—commercial skyscrapers, office parks, luxury apartments, suburban houses, boutique hotels, high-end commercial properties, and shopping malls. Such buildings fulfill residents’ yearnings to have what they missed during communism, not only the physical presence of new, colorful, and well-

11

made buildings, but also architecture practiced as a creative act by a known author. Financing for these projects came from multiple sources, both legal and illegal. Some were spurred by the concentrated wealth, influence, and political power that the privatization process generated, including money gained through criminal, deceptive, and corrupt means. This includes villas and vacation homes for rich oligarchs and ex-Communist officials, and office buildings, condominiums, and cultural centers financed with suspicious funds.

Investors in legitimate projects were often large international real estate companies, many headquartered in Western European, looking to take advantage of pent-up demand in the region. The real estate arm of the Dutch Bank ING was typical. In 1992, ING commissioned Frank Gehry’s Dancing House in Prague and then two years later hired the Dutch architect Erick van Egeraat from Mecanoo to renovate a nineteenth-century palace in Budapest for its Hungarian offices (Figure 13.10). In 2001, ING went back to Van Egeraat for the design of a newer 41,000-square-meter (441,000-square-foot) headquarters in Budapest. In the last 10 years, ING has funded a number of large mixed-use urban developments in cities such as Warsaw, and Liberec and Olomouc in the Czech Republic. Local entrepreneurs were also rich enough as the global building boom started in the early 2000s to commission commercial and residential projects, on their own or with international partners.

13.10 Frank Gehry with Vlado Milunić , Dancing House, Prague, Czech Republic, 1996. (Photo: Kimberly Elman Zarecor)

Rather than hire the local architects trained in the communist system, many large developers hired Western “starchitects” for their speculative projects, such as Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, Jean Nouvel and Renzo Piano. Their work in the region included Nouvel’s Galeries Lafayette (1996) and the Potsdamerplatz redevelopment (2000) by Renzo Piano and others in the former East Berlin, Gehry’s Dancing House (1996) and Nouvel’s Zlatý

12

Andě l/Golden Angel Building (2000) in Prague, and Foster’s Metropolitan Building (2003) in Warsaw (Figure 13.11).

13.11 Jean Nouvel, Zlatý Andě l/Golden Angel Building, Prague, Czech Republic, 2000. (Photo: © Petr Novák / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-2.5 / GFDL)

Successful émigrés such as the Czechs Eva Jiř ícná and Jan Kaplický, and Polish-born Daniel Libeskind, also returned to the region and built successful practices using their knowledge of the region’s languages and building culture. More recently, specialist architects such as American retail designers Jerde Partnership and Austrian housing designers Baumschlager and Eberle, have also been brought in to raise the notoriety and technical level of new projects. Other developers, like the Dutch Multi Corporation, have stopped hiring outside architects altogether, and rely, instead, on an in-house team of unnamed designers to spread its global brand of commercial modernism (Figure 13.12).

13.12 Construction of Forum Nová Karolina by Multi Corporation, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2011. (Photo: Kimberly Elman Zarecor)

A continuing interest in international architects can certainly be seen as a reaction against decades of anonymous design culture, but it is also reflects a desire to have some global status and proof of economic viability in the post-communist era. Not surprisingly, some starchitect proposals remain unbuilt because of inexperienced developers with overly ambitious designs. For example, Norman Foster had at least seven large Russian projects cancelled during the recent economic crisis, including the Crystal Island (2006) in Moscow, which would have been the world’s largest building with 2.5 million square meters (27 million square feet) of floor area and the Russia Tower (2006), designed to be the world’s tallest naturally ventilated building with 118 floors. There is also a scarcity of highly qualified workers in the construction industry and a

13

lack of government transparency and corruption in some countries. Recently this pattern—the preference for starchitects, corrupt politics, labor shortages, and a high rate of failed projects— has been repeated in Asia and the Middle East on an even larger scale.

Local architects have started to prove their potential to do work equal to their international peers. Some trained in the 1970s and 1980s have been able to adapt to the new conditions successfully, such as Vinko Penezić and Krešimir Rogina in Croatia and Josef Pleskot in the Czech Republic. There are also young practitioners, many educated both at home and in Western Europe or the United States, who are building reputations through small commissions and architectural competitions. One standout is the Slovene firm, Ofis Arhitekti, who started by designing innovative low-income housing in Slovenia and now have a global practice. Those looking to sample the region’s young talent can often encounter their work at the national pavilions of the Venice Biennale where the small size of the region’s countries allows for the work of many of the best designers to be exhibited. The ubiquity of English-language skills and the digitization of architectural practice mean that young Eastern European and Russian designers can now compete for projects outside their own countries, but so far few have made a name internationally.

Not surprisingly, the recent economic downturn has slowed the pace of development across the region and stopped the progress of young practitioners who are now struggling to find work. Some countries, including Latvia and Hungary, were especially hard hit by the 2008 collapse of the financial markets and subsequent crash of real estate prices. Cities and towns across the region were overconfident in the demand for new residential construction and currently have thousands of unsold units on the market. In many countries, residents have stayed in their communist-era apartments, spending money to renovate kitchens and bathrooms, instead of investing in costly new construction. The current situation is by far the worst in the former Soviet Union. Unlike countries that have joined the European Union, or the

14

former Yugoslavia which has finally recovered from the destructive 1990s, much of Russia and its former territories suffer from poverty and severe social problems. Little investment has reached beyond the large Russian cities on the Western side of the country or the oil-rich nations in the Caucasus Region like Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. Most Russians still live in unrenovated communist-era housing that continues to deteriorate with few options for financing improvements.

Contemporary Practice

Two examples suggest the diversity and complexity of contemporary practice in the region. The Jerde Partnership’s Złote Tarasy/Golden Terraces (2007), next to the Main Train Station in Warsaw’s central business district, is a mixed-use development with 232,000 square meters (2.4 million square feet) of office, retail, entertainment, and hotel space and 1,400 underground parking spaces. The complex brought an American-style mall experience to Warsaw with brands like Victoria’s Secret, The Body Shop, and Levi’s, as well as a multiplex cinema, Burger King, the Hard Rock Cafe, and two food courts. Its signature architectural feature is an undulating glass roof, one of the largest in the world, which emerges amoeba-like from among the complex’s more traditional office and hotel towers to enclose the retail space (Figure 13.13).

13.13 Jerde Partnership, Złote Tarasy/Golden Terraces, Warsaw, Poland, 2007. (Photo: © Kescior / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL)

Like many similar mixed-use projects in the region, including Jerde’s own WestEnd City Center (1999) in Budapest, it was designed to enhance the commercial infrastructure of a city that had previously relied on networks of small, poorly stocked shops and dismal office spaces. The city and ING Real Estate jointly financed the project, which was led by Chicago-based

15

Epstein in consultation with Jerde Partnership. Epstein opened a Warsaw office in the 1980s and helped shepherd the project through the complexities of local building codes and contractors. Like other large cities in the region, new construction is a point of pride for the city’s image. Złote Tarasy is just one of many new projects by international architects in Warsaw including an office building by Norman Foster, residential towers by Helmut Jahn and Daniel Libeskind, a museum by Finnish architect Rainer Mahlemaeki, and the German Embassy by Kleine Metz Architekten. In speaking about the boom in new buildings, and reflective of a general regional attitude, T omasz Zemla, Deputy Director of Warsaw’s Department of Architecture and City Planning, recently said, “we intend to build skyscrapers, yes ... to be honest, we want to show off.”21

A different view of contemporary practice comes through in a Russian example that shows the challenges of working in the region, especially when a building has national cultural significance. The new stage for the Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg finally opened in May 2013 after 11 years of planning and construction. In 2002, Los Angeles-based architect Eric Owen Moss was hired to expand the theater by adding a second stage to the existing historical complex. His proposal, which included an exuberant glass façade that appeared to explode out of a rectangular volume, drew ire from the citizens of St. Petersburg and theater professionals and worried the Ministry of Culture who had to pay the bill. The ministry decided to fire Moss and then announced an international design competition for the same site. Moss was invited to submit a new design, but did not prevail. Instead, French architect Dominique Perrault won with his vision for a new theater volume encased in a web of gold filigree. Construction started on the project and work continued for five years, but by then only the foundations were complete. At that point, the government abandoned the design due to cost and scheduling concerns.

Finally in 2009, a second competition was held and the commission awarded to Toronto- based Diamond and Schmitt Architects who had to partner with local architects, KB ViPS, who

16

had been working on the foundations of the Perrault proposal. The new design, which had to be adjusted slightly to incorporate some already-built foundation walls, is a contextual and comparatively conservative project with a masonry facade that matches the existing streetscape. According to the architects, its curved metal roof with a glass canopy “gives the building a contemporary identity rooted within the context of St. Petersburg’s exceptional architectural heritage.”22 Unhappy with its less ambitious design, some locals have likened it to a “supermarket.”23 Even so, it is notable that the theater actually opened in 2013 after such a protracted design process.

Conclusion

The history of architecture in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union in the last 50 years offers instructive lessons about the relationships between models of architectural practice and design culture. Communist economic planning imposed a set of priorities and restrictions on architects that were not formal, or even material, but rather established a professional culture through which a set of practices and standards emerged. This building culture operated for more than 70 years in the Soviet Union and 40 years in Eastern Europe. In this period, cities were created, expanded, and remade. Millions of modern apartments were built that still house the majority of the region’s citizens. However these environments were left to deteriorate without proper maintenance or investment. The last 20 years have been a period of reinvigoration and stabilization of these degraded spaces. For the most part, this has been a massive rehabilitation project, rather than the widespread demolition that some predicted. Thus Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union have an imprint of their communist years that will not easily be erased, even as new building types and international architectural trends become the norm.

Scholars use the terms communism, socialism, and state socialism to refer to the systems in these countries. For clarity, communism will be used here. Political scientist Andrew Roberts describes communist countries as “ruled by a single mass party that placed severe restrictions on all forms of civil society and free expression ... [had] almost complete prohibition of private ownership of the means of production and a high degree of central planning ... [and] were committed to revolution and the massive transformation of existing society.” Andrew Roberts, “The State of Socialism: A Note on Terminology,” Slavic Review 63/2 (Summer 2004): 359.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Good and the Good Looking: Exploring the Mediated Representation of the Aesthetic/Athletic Hierarchy in Women’s Professional Tennis

Carol Wical

A thesis submitted (Unsuccessfully) for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at

The University of Queensland in January 2010

School of Journalism & Communications

Declaration by author

This thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly-authored works that I have included in my thesis.

I have clearly stated the contribution of others to my thesis as a whole, including statistical assistance, survey design, data analysis, significant technical procedures, professional editorial advice, and any other original research work used or reported in my thesis. The content of my thesis is the result of work I have carried out since the commencement of my research higher degree candidature and does not include a substantial part of work that has been submitted to qualify for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution. I have clearly stated which parts of my thesis, if any, have been submitted to qualify for another award.

I acknowledge that an electronic copy of my thesis must be lodged with the University Library and, subject to the General Award Rules of The University of Queensland, immediately made available for research and study in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968.

I acknowledge that copyright of all material contained in my thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of that material.

Statement of Contributions to Jointly Authored Works Contained in the Thesis

“No jointly-authored works.”

Statement of Contributions by Others to the Thesis as a Whole

“No contributions by others.”

Statement of Parts of the Thesis Submitted to Qualify for the Award of Another Degree

“None.”

Published Works by the Author Incorporated into the Thesis

“Out at the Open : Amelie Mauresmo and the Australian Press ”. Sexualities. Special Issue: European Culture, European Queer. Lisa Downing and Robert Gillet (Eds.). Forthcoming.

Additional Published Works by the Author Relevant to the Thesis but not Forming Part of it

Stand Still, Look Pretty : Representation and Tradition in Mainstream American Women's Country Music 1972-2005. Saarbrucken: VDM, 2009.

“Disguised as ‘One of the Guys’? The Contribution of Terri Clark to an American Country Music Women’s Tradition”. Rhizomes : Connecting Languages, Cultures and Literatures. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2006.

Acknowledgements

This project would have been impossible without the support of an Australian Postgraduate Award and the smooth machinations that saw it make its way into my account – my enduring respect to the folk at the Graduate School and the School of Journalism & Communication. It would also have been impossible without the following folk to who boundless thanks are due:

Firstly to the Drs John Cokley and Murray Phillips who patiently waited for me to discover what story I wanted to tell then cheered from the sidelines until it was done. My colleagues at AustLit: The Resource for Australian Literature, especially The Boss Kerry Kilner. To the Gordon Greenwood/ Room 317 gang – it could have gone very wrong without you all there to remind me of the reasons for my love affair with diversity. Particular thanks to AL and Ellen who kept 2.0 from forgetting to have fun and the importance of cake. To Emma, who has managed to share a flat with me all the way through it and still thinks I’m an OK Aunt – thanks for the company and the cleaning and the cat wrangling. Thanks to my mother who in her eighties continues to learn something new every day. And to the staff of 6N.

Abstract

This project concludes that different narratives need to be built around sportswomen if their elite level competitions are ever to have a sustainable future on broadcast television. Particularly, I suggest avoiding dependence on the instability of a single, accredited model to which all other players must conform.

I have taken up a strategic position at the intersections between feminist theory and queer theory in order to re-read how broadcasters, journalists and other stakeholders in women’s tennis events participate in the constructions of sportswomen’s identities, especially in elite professional tennis. Theoretically underpinned by Foucault, Butler, Halberstam, Tasker and McRobbie this project uses a high-functioning popular culture to disconnect notions of sex, gender and sexuality in order to advocate for the representation of diversity. Taking cues from the boundaries placed on public performances of gender by women in the public eye, the narrative themes present in the Channel 7 broadcast of the 2007 Australian Open tennis championship match between Serena Williams and Maria Sharapova are identified and analysed. I especially note themes supported by the major stakeholders in women’s tennis: infantilisation, the erasure of difference, the denial of effort, and the insistence on normative performances of femininity.

I use theoretical approaches in an exploratory way to try to unearth areas of cultural uncertainty such as gender performance where the vernacular might best be exploited to align female professional athleticism as an accepted cultural practice. Attention to broadcasters’ vocabulary is not the issue but that entire narratives must be renovated or constructed in the broadcast of women’s sport. Players, I argue following Peterson, need to actively engage with authenticity work – plundering their own life facts and the tradition of their sport to build intertwining narratives of self – as a part of their job that needs constant maintenance. Narrative cohesion and sustainability on the individual, community and cross-cultural levels are suggested as a viable basis for a stable cultural profile. Ultimately, I question whether increasing the quantity of women’s sport available to be viewed on television can have the positive impact government and NGOs seek. I suggest that unless the content and presentation of these broadcasts are first addressed, increased broadcast quantity may have a detrimental overall effect.

Keywords

Queer theory, feminist theory, sports broadcast, gender, narrative, tennis, women, journalism

Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classifications (ANZSRC)

20 Language, Communication and Culture 100%

With diversity there is strength. In the end, we have to celebrate our differences, not tolerate them. – Billie Jean King (Steele, 2007: 93)

Contents

Abstract. 4

Keywords. 5

Chapter 1: Introduction. 10

Beginnings and Underpinnings. 10

Defining Some Key Terms. 13

Systemic Diminution. 14

A Cultural Studies Approach. 15

Quantity v Quality of Exposure. 17

Other Backgrounding Factors: A Cluster of Anxieties and Tensions. 20

Chapter 2: Outline: Sport, Women, Media. 23

Research Purpose. 23

Research Objectives. 23

Research Questions. 24

Rationale of Study. 24

Operational Definitions. 24

Women, sport, media. 25

Theoretical Framework. 28

Image maintenance: narratives of self, tradition and progression. 28

A Queer Feminist Perspective. 30

Methodology. 31

Thesis Outline. 32

Chapter 3: Literature Review.. 34

Women in popular culture. 34

Positioning the media. 34

Positioning the audience. 37

Gender Identity. 39

Gender, sexuality, sport. 41

Cohesion and credibility. 45

Chapter 4: Findings: Stereotype and the Authentic. 49

The Performer and the Authentic. 49

Adapting and Applying Petersen’s Authentic – Problems and Possibilities. 50

Connections to the Authentic. 52

The Player and Stereotype. 53

The Stereotype/Authentic Connection. 55

The Narrative Power of Authenticity and Stereotype. 56

Celebrity and Authenticity. 57

Amplification of Uncertainty. 58

The Model/Player. 60

A Problem Like Maria. 60

The Trouble With Serena. 63

Straight Sets : Heterosexual Cohesion. 64

Role Models. 65

Conclusion. 66

Chapter 5: Discussion: Chosen Narratives: Wasters, Low Stakes and Divas. 69

Some Prevalent Concerns: Race, Power, Ease. 69

Race. 70

Power. 70

Ease. 73

Same-ing the Players?. 75

Divafication: What’s ethnicity got to do with it?. 78

Prima Divas: Waste and Work. 79

Origin mythologies. 81

Innovators. 82

Noise and Silence. 86

Theme Songs : Singing The Survivor and the Object of Desire. 87

Feminised Uber Narrative. 91

The Incident at the End of the First Set. 94

Conclusion. 97

Chapter 6: Conclusions: Towards a Sustainable Female Sporting Stereotype. 98

The Model/Player Dichotomy. 99

A Cluster of Promises. 103

Constrictions to the Search for a Cohesive Identity. 106

Gender, Sex and Sexuality Anxieties in the Contemporary Australian Context. 107

Gendered Space. 112

Space. 112

Individuation. 115

Economy and Culture. 119

Race. 120

Nation. 121

Class. 122

Conclusion. 123

Chapter 7: Cohesion, Community, Difference: Setting Other Imageries. 124

Same-ing. 125

The Importance of Being Earnest. 126

A Clear and Present Legacy. 128

Overregulated Identities. 129

Agency and the Constructed. 131

The Promise of Community?. 133

On the Margins of What May Be Represented. 134

Really?: “Reader” Sanctioned “Authenticity”. 136

Conclusion. 138

Where Does It Hurt? : Towards Identifying and Utilising Porous Boundaries. 138

Chapter 8: Conclusion and Recommendations. 142

Stories Told Well 1: Organisational Narratives. 143

Stories Told Well 2: Player Identity Narratives. 145

Stories Told Well 3: (Hardly) Sporting Narratives. 146

What Does It Matter?. 147

References. 149

Chapter 1: Introduction

This thesis explores and exposes sites of access to sporting narratives towards sportswomen and women’s sports being represented via a non-heterosexist, non-misogynistic broadcast culture. The main text interrogated is the “live” free-to-air Australian broadcast by Channel 7’s 7Sport of the championship match of the women’s draw of the 2007 Australian Open tennis tournament (see Figure 2). For comparison I also analyse the internet home pages of Serena Williams and Maria Sharapova (the antagonists in the match of the main text) and also that of Ana Ivanovic. My approach is from the intersection of feminist and queer theory. My particular interest is in what is said in the broadcast before the action on court began to override the pre-prepared narrative trajectory. This turning point occurs just over an hour into the broadcast (see Appendix 1 – Transcript at 1:04:00).

Beginnings and Underpinnings

The two following quotes hold within them the concerns that initially generated this project. The first quote succinctly encapsulates the ascendency of aesthetics over the ability of sportswomen and challenges heterosexism particularly as it is linked with the confusion

Match

Championship Game, Women’s Draw, Australian Open

Date Played

26 January, Australia Day, 2007