#trad/ivy

Text

Happy St.Paddy’s Day! ☘️

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

#traditional peanut#trad#style#mensfashion#vintagestyle#tailoring#preppy#ivystyle#ivy league#vintage#mens style#1960s

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I wore today Wednesday February 14, 2024

#prepdom#preppy#wiwt#ootd#ivy style#ivy league style#trad style#take ivy#ivy look#enclothed cognition#collegiate style#saddle oxfords

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

harlivy shitpistin

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Corduroy Jacket: All-American Ivy/Trad Staple

#mature style#classic menswear#vintage style#classic style#utah#corduroy#ivy style#trad#brooks brothers#polo ralph lauren#ll bean#winter style#winter vibes

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Seersucker Jacket: Turist, Made in Italy, thrifted

Cotton Pocket Square: Tie Bar, thrifted

Shirt: Brooks Brothers, vintage, thrifted

Jeans: Levis, thrifted

#ptoman#styleforum#turist#brooksbrothers#levis#styleformen#mensstyle#theblackivybook#blackivy#ivyleaguelook#ivy#trad

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

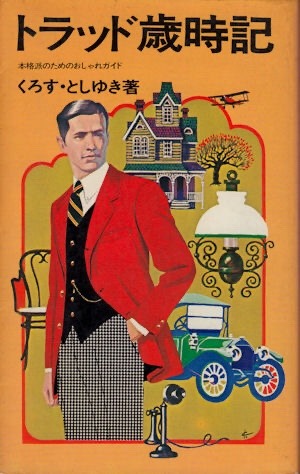

How Ivy Fashion Shaped Oshare Culture

A common thread connects lifestyle-oriented brands, dokumos, and the contemporary Japanese fashion world: the historical menswear brand VAN.

“Shopping hauls,” #OOTD (outfit of the day), “what’s in my bag,” “my nightly beauty routine,” daily vlogs, traveling vlogs… Seeing life-sized influencers and ordinary people sharing their purchases, day-to-day life, and lifestyle tips is a popular form of content on global social media, from the days of blogging to Youtube, Instagram, and now, TikTok.

In this, Japan has been far ahead of the curve. Decades before the existence of social media, Japanese fashion magazines were already using relatable personalities to explore these topics.

The role of professional models in magazines, for example, isn't only to look beautiful on their pages. They also serve as muses to readers, sharing a glimpse into their daily looks, shopping habits, glamorous trips, and beauty tips. Publications are also full of non-professional "dokumos" (reader models), satisfying readers' curiosity about how ordinary people adapt the magazine's ethos and trends into their day-to-day life.

The editorial appeal of this content is straightforward: it is a direct link between the trends and ideas advocated in theory by a magazine and the real practical world. But to understand how magazine editors and the fashion world realized how potent this strategy was, we have to go back to the 1960s and to the trend that started it all, Ivy fashion.

Ivy Style and the First Fashion Magazine

The book "Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style" by W. David Marx explains how Japan adopted the "American traditional" fashion, made its own, and ultimately saved it. The starting point was the popularization of the "Ivy style" -- a look inspired by preppy, affluent students in US Ivy League universities -- in 1960s Japan.

"AmeTora" is predominantly about male fashion. On "Oshare Nippon," on the contrary, I talk primarily about women's fashion and trends. Still, W. David Marx's book, which serves as the basis for almost everything in this post, is a must-read for Japanese fashion lovers. Understanding the rise of "AmeTora" is an essential insight into contemporary Japanese fashion as a whole.

The origin of the Japanese "American Trad" can be traced back to Kensuke Ishizu, heir to a paper wholesaler company, born in 1911 in Okayama. He came of age during the Taisho Era when Japan opened to the world and society adopted Western customs.

Growing up, Ishizu was a fashionable playboy with a passion for Western clothes who lived a fun-filled college life in Tokyo. When the considerably stricter first half of the Showa Era began, Ishizu moved back to Okayama to marry his girlfriend, taking over his father's business. His dream, however, was to make clothes for a living.

Things would become tumultuous during the war period. He avoided most of the initial hard times by moving to China (then partially under Japanese control) to help control a department store owned by a friend's family. Living in the then-cosmopolitan Tianjin and working with his true passion, fashion, the young Ishizu was happy. Even after Japan's defeat, he befriended American soldiers, which helped him live sheltered from the misery of war. Eventually, however, he was put in a cargo boat to return, with no money, to war-thorn Japan.

After living through the most dramatic periods of the conflict, with constant aerial attacks and food shortages, the war was finally over. Defeated, Japan was in poverty. But Ishizu, who had a lot of fashion expertise, soon found a job as a menswear designer for a high-end clothing showroom in Osaka.

With misery everywhere, it was an odd time to sell upscale clothes. But, it was also a watershed moment for the perception of the US by the Japanese public, as the population started admiring the sheer affluence of what was, until recently, their enemies. Everyone aspired to a wealthy "American lifestyle." And who had an advantage in this scenario? Ishizu, with his lifelong passion for Western culture, experience living abroad, cosmopolitan taste, and knowledge of Western clothing.

In 1949, Ishizu started his own business, Ishizu Shoten, which he would later rename VAN. In 1950, cash started flowing to Japan due to the Korean Peninsula War. The war made the country a key manufacturing base for the US military, creating a sizable moneyed elite. In 1952, the country regained its sovereign status. Transitioning to a new period, the population wanted to leave traditional garments behind and dress in Western fashion.

At the time, almost everyone in Japan wore custom-made clothes. But Ishizu's ready-to-wear brand became popular with the elites. Osaka's biggest department store, Hankyu, gave his brand a corner; from there, he found loyal customers from the affluent suburb of Ashiya.

Ambitious, he wanted more. But, to keep growing, he needed the expanding "new middle class." But there was a significant obstacle: it was taboo for men to show interest in fashion. In conservative Japan, that was a sign of delinquency. Serious men had a uniform: tailor-made suits. And that was more than enough. For his ready-to-wear brand, VAN, to succeed, Ishizu had to change this mentality.

Women, on the contrary, could freely enjoy following global trends. They didn't buy Pret-a-porter either, but dressmaking guides had the latest styles from the USA and France, and movie stars like Audrey Hepburn influenced trends in clothes and beauty. And this discrepancy was starting to bother a few of them, who resented that they were going to parties and weddings in the latest Parisian fashion accompanied by their husbands in bland suits.

In early 1954, editors of women's magazine Fujin Gaho decided to respond to these complaints and started developing a fashion magazine for men. For the sake of his brand, Ishizu also had an urgent interest in educating Japanese men on fashion.

In search of men with fashion knowledge, editors found Ishizu. And from their partnership, Otoko no Fukushoku (Men's Clothing) was born.

Educating Men

While researching Japanese fashion, one can notice an interesting pattern. Many historical developments started with men before being taken over by women. For example, women are the fuel of the Japanese fashion industry. But it can be argued Ivy fashion was the origin of contemporary Japanese fashion, and Ivy was, initially, men's fashion. Likewise, fashion magazines are historically a vital segment of the Japanese publishing (and fashion) industry, and women are behind its success. But the first fashion magazine had men as its target.

In late 1954, when the first issue of Otoko no Fukushoku was published, there were fashion-specific titles for women. But they were all utilitarian, full of dressmaking patterns. There were still some significant differences, but Otoko no Fukoshoku was much closer to what a standard Japanese fashion magazine became than the dressmaking titles.

In any case, Ishizu used the magazine as a vehicle for his brand. As W. Marx puts it, "Ishizu did more than just help write articles; he turned Otoko no Fukushoku into a VAN media organ." VAN's clothes and philosophy were all over the magazine.

But more than promoting VAN, the magazine had to educate men on what clothes are. Japanese men had no clue about anything fashion-related. They simply transitioned from their school uniforms to tailor-made dark suits. It was up to editors to teach them all the intricacies of style.

Once again, this underlines the role and influence of fashion magazines in Japanese history. While social media and the digital takeover have made them obsolete, the Japanese fashion industry was built on its back, and up to very recently, they enjoyed almost unparalleled power.

Back in the mid-1950s, Ishizu and the editors of Otoko no Fukushu achieved their goals. Men started showing more interest in fashion, and coupled with the improvement in the Japanese economy and living standards, VAN grew exponentially.

But there were still some challenges ahead, starting with the fact the Japanese simply didn't like off-the-rack clothing. Men would see something that pleased them on Otoko no Fukushu and ask their tailors for something similar.

Resigned to the fact he wouldn't be able to change the minds of middle-aged men, Kensuke Ishizu decided to turn his attention to young people.

The Future is Ivy

VAN wasn't a brand suited for students. It was expensive, formal, and very niche. But Ishizu forged ahead with his plan to make it more appealing to this group, starting with changes in the magazine he used to fuel his brand.

Firstly, the descriptive name Otoko no Fukushu was changed for the catchier, more informal "Men's Club." While every issue had a small section dedicated to university students, Ishizu asked editors to expand youth-centered content.

As for the clothing itself, he was ready to develop a new line for younger men. Unsatisfied with the contemporary trends in Japan, he went on a world trip to find inspiration, culminating in his first visit to the USA. He was suspicious of American taste, believing Europeans were much more refined. But, even though he didn't think Japanese men could wear the style, he was curious about US Ivy League fashion which Men's Club routinely covered.

But, as soon as he arrived at the Princeton campus, he fell in love with the neat traditional, Old Money fashion and its use of natural materials such as cotton. Being Old Money himself, he felt an emotional attachment to the style. So, overflown with emotions, he decided he would make Japanese youth fall in love with Ivy fashion.

Converting the Youth

At 49 years old, Ishizu felt he needed younger people around him to truly understand how to sell VAN to another generation. Soon, he found the perfect ally to help him: Toshiyuki Kurosu, an Ivy-style convert since his late teens.

Kurosu, much like young Ishizu himself, loved fashion and foreign culture. His parents wanted him to dedicate himself to studying, and he attended the prestigious Keio University, but what he cared about was cool American clothes, fashion, and jazz. He bought "Otoko no Fukushoku" from its first issue and immediately fell in love with the "Ivy League" style he read about in the "Dictionary of Men's Fashion Terms" feature. There were no illustrations or pictures, but he became fixated on the look.

His obsession deepened when he befriended Kazuo Hozumi, an architect who left his full-time job to become a freelance fashion illustrator for Otoko no Fukushoku. Together, they'd study the style from imported magazines Hozumi got from the editorial house's office. Soon, the two became the first Ivy Leaguers in Japan.

After leaving college, Kurosu started writing about jazz and fashion for Otoko no Fukushoku, then rebranded as Men's Club. At the magazine, Kurosu befriended a young editor who soon left to join his father's company. It was Shosuke Ishizu, the son of none other than Kensuke Ishizu from VAN. Eager to have someone younger in charge of the youth line, Ishizu appointed his son for the job. And the son recruited Kurosu, Japan's foremost Ivy expert, to help him.

After a lot of trial and error, deep research of American magazines, and an arduous quest to find a factory to produce the intricate pieces, the full Ivy line came together in 1962. And then, one more obstacle: department store buyers hated it. The gold buttons, essential to turn an ordinary suit into an Ivy-style blazer, had nothing to do with Japanese taste. "This is Japan -- not America," they proclaimed.

Ishizu was sure that, given a chance, the youth would be seduced by the Ivy style. So, he decided to cut the middle man, believing young males were more influenced by magazines than department stores. From 1963, Men's Club would be overtaken by the Ivy style, explaining every small detail around it and reprinting all pictures of American college students they could get their hands on.

There was just one small problem: the Ivy universe was contained within the pages of Men's Club. Outside, in the real world, young men were still in their uniforms and bland suits.

The Emergence of the Street Snaps

In society, we feel the need to belong. It's an inherent part of human nature. Hivemind behavior and mentality are one of the results of that. It can be argued those impulses can be potentialized in a collective-driven society such as Japan. A famous Japanese proverb, often deployed to describe its culture, is "the nail that sticks out, gets hammered down."

For Ivy fashion to become mainstream, it needed to exist in the real world. But, more importantly, for Japanese youth to have the confidence to wear it, it needs assurance others are wearing it too.

So, one turning point for the style was when Kurosu did an "Ivy Leaguers on the Street" column in the Spring 1963 issue of "Men's Club." Accompanied by a photographer, he went to the glitzy district of Ginza to snap young passers-by dressed in East Coast preppy style. It was a tremendously difficult task: hardly anyone was dressed suitably. Still, they had enough pictures to run the feature. The feedback was explosive: readers loved it. Soon, fashionable Ivy teens took over Ginza's main avenues in the hopes of catching Men Club's photographer's eye.

The column, nicknamed Machi-ai (from the Japanese title: "Machi no Aibii Riigazu"), became the most popular part of the magazine. Since then, "street snaps" have become a staple of Japanese fashion magazines, one of the most effective ways of disseminating trends.

"Street snaps" showed that trend-conscious Japanese wanted to see themselves in magazines. They wanted to see the trends in real-life settings and in practical situations. It's fair to assume "dokumos" and the heavy use of "ordinary" boys and girls in domestic fashion magazines came as a consequence.

In trying to sell its youth line, VAN helped mold Japanese fashion magazines and consumer behaviors.

Clear Instructions

Compared to what was available at the time, Men's Club was much closer to what became the definitive Japanese fashion magazine style. In its attempts to sell VAN clothes, Men's Club set standards for the segment, with street snaps being just one of the many examples.

Japanese fashion magazines are full of authoritative figures readers look up to. Models, dokumos, stylists, beauty artists. Men's Club came directly from VAN employees and had Kensuke Ishizu, his son, Shosuke Ishizu, Toshiyuki Kurosu, and Kazuo Hozumi.

By 1964, VAN was in optimal condition, with editorial control of Japan's top menswear magazine and available in boutiques nationwide. Still, the high prices remained an obstacle for most, and the VAN consumer base was formed entirely by rich kids, creatives at top advertising firms, and celebrities. Japan growing middle class was instead spending their money on the "three sacred treasures" (black-and-white TVs; electric washing machines; refrigerators) before moving on to the "three Cs" (color TVs, cars, and coolers -- a.k.a., air conditioners). Fashionable ready-to-wear clothes were still an afterthought.

For VAN, the challenge was immense because they were literally creating a market from scratch. The average Japanese didn't buy ready-to-wear clothes, the average man couldn't have an interest in fashion, and youth fashion barely existed.

Step by step, VAN was overcoming each of these obstacles. And, to make Ivy more palatable to the average young man, they decided to minutely break the style down in the pages of Men's Club. As per "Ametora," they compared clothes with medicine to summarize their mission.

When you buy medicine, the instructions are always included. There is a proper way of taking the medicine, and if you do not take the medicine correctly, there may be adverse effects. The same goes for dressing up -- there are rules you cannot ignore. Rules teach you style orthodoxy and help you follow the correct conventions for dress.

The Ivy Q&A became a column in the magazine, where Kurosu explained every tiny detail related to how to dress appropriately in Ivy style. Some explanations were essential. For example, the controversial golden buttons department store buyers railed against were precisely what made that suit into a blazer, a quintessential Ivy piece. And would-be consumers needed to be educated about that. On the other hand, some rules were made up as he went along. After all, there was way too much space to fill.

What's important to note is that this rules-based way VAN and Men's Club used to sell the Ivy line had a tremendous impact on how fashion is consumed and sold. Compared to Western fashion magazines, full of conceptual editorials and light suggestions, the standard Japanese fashion magazine is basically a manual. It's not "look at these cute jeans" but "here are the 80 correct ways of matching jean pants in accordance with current trends". It's less "be inspired by these party looks," and more "here are 50 party looks for you to copy step-by-step". The correct rules are emphasized every step of the way.

Of course, this goes much further than VAN. It reflects Japan's fixation on rules. It also outlines significant differences between the West, where people follow trends unconsciously, and Japan, where there's extreme awareness among the trend-conscious portion of the population. Kurosu himself noticed this when a visit to a US Ivy campus had students confused by his questions. "Are these short pants in style?" he'd ask a college student, only to be met with blank stares and "I've never thought about it" answers.

In Japan, on the contrary, there's quite a lot of overthinking involved in following fashion. And in the pages of Men's Club, Ishizu, Kuroza, et al. were among the first ones to make that clear.

Ivy Goes Mainstream

In 1964, Tokyo hosted the Summer Olympics in what became a milestone year in post-war Japanese history. It was also a historical year for VAN and its Ivy Style.

In April, Heibon Publishing launched Heibon Punch, a weekly magazine for urbanite young men. Loosely inspired by Playboy, it had a bit of everything: general interest articles, full-colored pictures of naked girls, and fashion. Fashion, in that case, meant "Ivy fashion." As the emerging youth trend, heavily pushed by the top menswear magazine, Men's Club, it was the natural choice for Heibon's editors to choose the style as its focus. Kensuke Ishizu had a column on menswear with illustrations from Kazuo Hozumi.

Another interesting touch in the magazine was the covers, which had an artistic edgy. They were all illustrated by Ayumi Ohashi, who contributed a few times with Men's Club before getting the Heibon Punch's gig. Her drawings often had boys in Ivy, including the first issue cover.

Heibon Punch was an immediate success. The first issue sold 620k copies and, in two years, circulation reached one million. Men's Club was a popular title but niche, with a reach limited to fashion-loving boys. Heibon Punch was as mainstream as it could be. Suddenly, almost every young man in Japan knew Ivy was the trendiest style.

The Tumultuous Boom

What happened next (in a short few months) was tumultuous and a good display of the contradictions in Japanese society.

For starters, the emerging trend caused a moral panic. Out of nowhere, young men went crazy for Ivy fashion. Those who could not afford the expensive VAN clothes made do with the VAN shopping bags, which also became a status symbol. The home electronics company SANYO partnered with VAN to release branded razors, hair dryers, and tape recorders.

Adults were scandalized by the kids leaving their uniforms behind and hanging around town in weird Western trends. In many small towns, teens were prohibited from carrying VAN bags or entering shops selling the brand. Parent-teacher associations sent formal requests asking retailers to stop selling VAN clothes to students. All this panic only made the brand even more desirable.

The massive group of boys who'd spend all day in the luxurious Tokyo district of Ginza was of particular concern. Nicknamed Miyuki-zoku (Miyuki Tribe, named after Ginza's Miyuki street), they were seen as delinquents for caring about clothes and adopting feminine habits, such as grooming and styling their hair. After the number of Miyuki-zoku boys kept growing, police were deployed to liberate Ginza from these dangerous trend-conscious men. They were answering pressure from the media, and authorities worried these rebel teens would be a source of embarrassment to the nation during the incoming Olympics.

Ironically, take a guess on who was tasked with planning the official Japanese uniform for the Olympics. VAN's Kensuke Ishizu himself. And he decided to dress the athletes with the quintessential Ivy piece department store buyers had no time for, the blazer. Not any blazer, mind you, but a red blazer. In hindsight, it wasn't such a groundbreaking idea: most international delegations wore something similar. But, in Japan, panic ensued: journalists complained the color was too feminine, and the head Olympic tailor was so enraged with the design he ended up in the hospital.

It all seemed significantly over the top, right? And the Japanese public agreed. There was no shock as soon as they saw the athletes marching down in their blazers. The general reaction was: "cute! I want a blazer too!". And so, all the department store buyers came rushing back, flooding VAN with orders.

Between Heibon Punch and the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, VAN and its Ivy fashion were on their way to becoming a national phenomenon.

Setting the Standards

Of course, nothing lasts forever. Especially when it comes to fashion. VAN would eventually go bankrupt, Ivy would go out of style, and even the editorial phenomenon Heibon Punch would be discontinued in 1988 (Men's Club, on the other hand, is still in print).

But, there'd be a long way between 1964 -- which was only the beginning of the phenomenon -- and Ivy's demise. In the meantime, VAN would reach the equivalent of 600 million dollars in sales and open the doors in Japan for sneakers, T-shirts, and Anglo-American fashion in general. For a complete picture of the rise of "American traditional," W. David Marx's book is essential reading.

Here, I decided to focus on the first few years of VAN because its rise set the standard for contemporary Japanese fashion. While trying to establish the brand, VAN's team created essential parts of oshare culture.

Firstly, there's the concept of the fashion magazine. What they did to Men's Club to help sell their clothes -- street snaps, detailed instructions, partnered content -- was the basis for the editorial guidelines of the billionaire Japanese fashion magazine industry.

Then there was this whole lifestyle created around their label. Of course, trying to convey a lifestyle with your brand is a standard marketing technique. But VAN took it to a whole other level. And the Japanese fashion market took note.

Until UNIQLO and fast fashion came along, clothing in Japan was expensive. For the prices to be justified, there was a need to create an experience for clients. In this scenario, conveying a clear lifestyle with your label is necessary for those who want to succeed. It's also a country where customers can be extremely loyal and can really buy into the experience provided by your brand. Therefore, rewards and a direct line with patrons are essential. VAN was a pioneer in dominating these techniques.

There's also the fact the Japanese trend-conscious public look up to authoritative figures. Store clerks, P.R., and everyone involved with a brand need to be an expert on the lifestyle being sold. Charismatic producers and designers representing the company and its ethos on traditional and social media can boost a label's image. From the beginning, VAN did an excellent job turning its leadership figures (and everyone else involved with the brand) into celebrities among its customer base.

Finally, the VAN crew was directly responsible for creating the "trad" style.

With Ivy fashion causing controversy and becoming popular with teenagers, the original customers started turning their back on the company. To attract them back, Kurosu decided to give a new moniker to the style sold by its adult-oriented line, Kent. Instead of "Ivy", Kent sold "trad" (from "traditional") clothes.

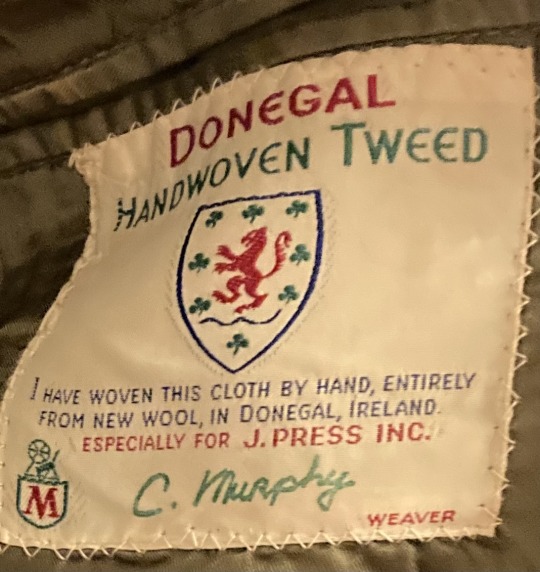

"Ivy" is a style directly tied to US campus fashion, with strict rules. "Trad" is a much broader style, encompassing classic looks and heritage brands beyond the US (a Burberry trench coat, for example, is "trad"). While in Japan, "Ivy fashion" proved itself somewhat ephemeral, a trend from the past (which comes back in style cyclically;) "trad" remains a cornerstone style of local fashion.

The original Ivy fashion was a menswear trend. At Oshare Nippon, I focus on the much more dynamic female fashion world. But, as the origin of contemporary Japanese style, VAN and its Ivy culture is part of the DNA of oshare culture regardless of gender. It's the starting point for everything I plan to cover here.

The First Issue of Heibon Punch

Ivy Boys and Iconic Ivy Illustration

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alden Fayetteville Snuff

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sid Mashburn

Sid Mashburn

1198 Howell Mill Rd. NW, Atlanta

Sid Mashburn the brand started as Sid Mashburn the shop, in Atlanta.

While that may be true of the brand name as a business, perhaps it helps one understand the sort of look Sid Mashburn creates if the CV of Sid Mashburn the man is explained.

Mashburn has been a designer for J. Crew, then a designer for Polo, then Tommy Hilfiger, and then on to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

9/11. Remembering those who lost their lives, and those whose lives were forever changed that day. Never forget. 🙏🏼

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

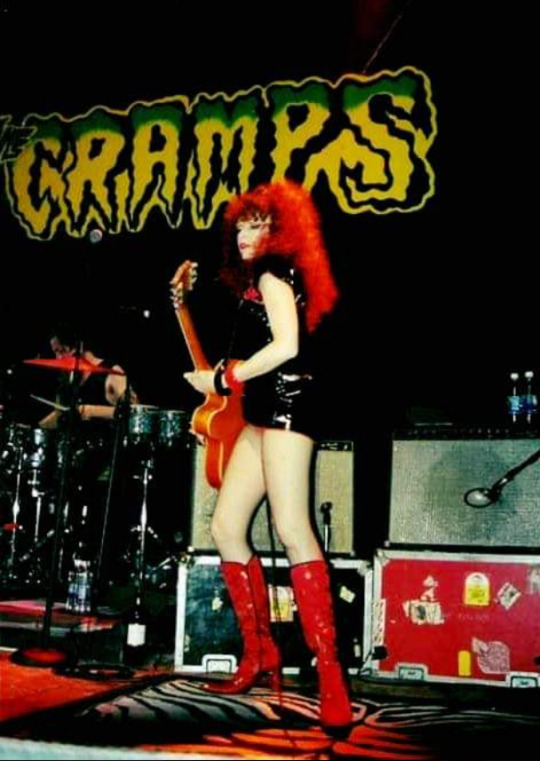

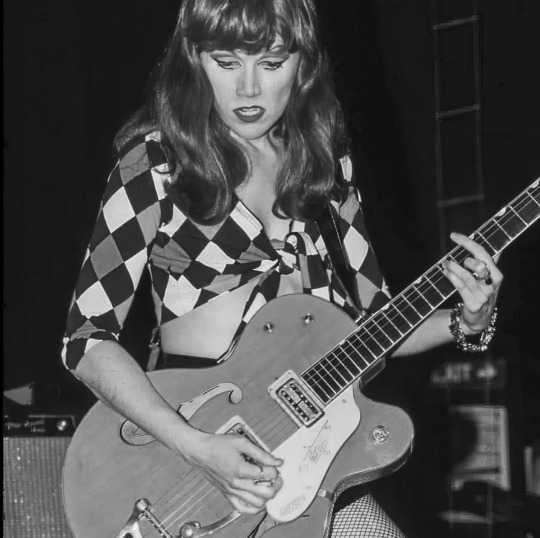

Poison Ivy / The Cramps

pic: Steve Taylor

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I wore today Wednesday March 27, 2024

#prepdom#preppy#wiwt#ootd#ivy style#ivy league style#trad style#ocbd#knit tie#weejuns#take ivy#ivy look#enclothed cognition#collegiate style#seersucker

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dad has had this Birdwell cardigan on his list for over a year, so when the bonus came through, he pulled the trigger. Dress it up or (way) down. Hey, it was Friday, fools. Cardigan: @birdwellbeachbritches Henley: @bronsonmfg Bandana: Army Surplus down the street Cap: @lrgclothing Chinos: @jcrewmens Watch: @casio_us with a silicon strap Coffee cup: @stanley_brand … #menswear #streetwear #prep #preppy #mensstyle #dapperdad #wiwt #ootd #ootdmen #mensblog #mensweardaily #ivy #ivystyle #trad #tradstyle #birdwellbeachbritches https://www.instagram.com/p/CdEd6iTLKdy/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#menswear#streetwear#prep#preppy#mensstyle#dapperdad#wiwt#ootd#ootdmen#mensblog#mensweardaily#ivy#ivystyle#trad#tradstyle#birdwellbeachbritches

0 notes