#trying to write an image description for a decision tree like this is a challenge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

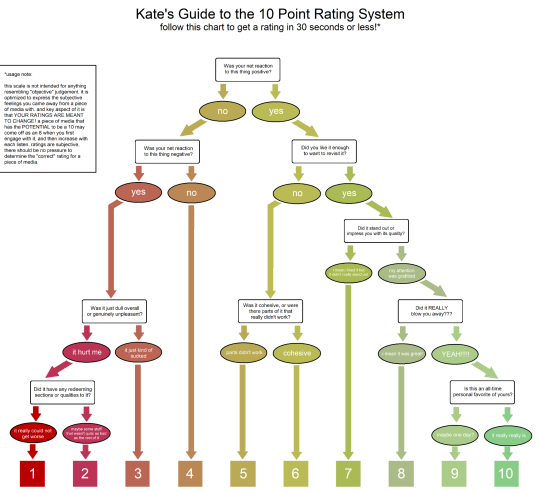

[ID: decision tree with a red-yellow-gradient from left to right. The title is "Kate's Guide to the 10 Point Rating System" and subtitled "follow this chart to get a rating in 30 seconds or less! (*see usage footnote)"

Was your net reaction to this thing positive?

The root node asks "Was your net reaction to this thing positive?" If no, "Was your net reaction to this thing negative?" If yes, "Did you like it enough to revisit it?"

Was your net reaction to this thing negative?

If yes, then "Was it just dull overall or genuinely unpleasant?" If yes, then "Was it just a dull overall or genuinely unpleasant?" If no, then rate as a "4".

Was it just dull overall or genuinely unpleasant?

If "it hurt me", then "Did it have any redeeming sections or qualities to it?" If "it just kind of sucked", rate as a "3".

Did it have any redeeming qualities to it?

If "it really could not get worse", rate as a "1". If "maybe some stuff that wasn't quite as bad as the rest of it", rate as a "2".

Did you like it enough to want to revisit it?

If no, then "Was it cohesive, or were there parts of it that really didn't work?" If yes, then "Did it stand out or impress you with its quality?"

Was it cohesive, or were there parts of it that really didn't work?

If "parts that didn't work", rate as a "5". If "cohesive", then rate as a "6".

Did it stand out or impress you with its quality?

If "i mean i liked it but it didn't really stand out", then rate as a "7". If "my attention was grabbed", then

Did it REALLY blow you away???

If "I mean it was great!!!", then rate as an "8". If "YEAH!!!!" then

Is this an all-time personal favorite of yours?

If "maybe one day?" then rate as a "9". If "it really really is" then rate as a "10".

*usage note

this scale is not intended for anything resembling "objective" judgement. it is optimized to express the subjective feelings you came away from a piece of media with. and key aspect of it is that YOU RATINGS ARE MEANT TO CHANGE! a piece of media that has the POTENTIAL to be a 10 may come off as an 8 when you first engage with it, and then increase with each listen. ratings are subjective, there should be no pressure to determine the "correct" rating for a piece of media.

/end ID]

i just made this for myself, but multiple people have told me they find it really useful so i thought id share it!

#rating scale#decision tree#flowchart#trying to write an image description for a decision tree like this is a challenge#I decided to go with the order that I read it#used headers because screen readers should be able to jump to and from headers. I think.#id by me

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

Floating World

by Wardog

Tuesday, 06 September 2011

Like everyone else, Wardog has been playing Bastion.~

Kid sits down, tries to write a review, but the words ain't coming.

Let's try this.

A silent, nameless, white-haired protagonist wakes up one morning in a bed in a shattered room floating de-anchored in a swirl of coloured space. “Proper stories supposed to start at the beginning,” growls a narrator reminiscent of the cowboy in The Big Lebowski, “here a kid whose whole world got all twisted, leaving him stranded on a rock in the sky.” A tap on the gamepad and the kid is out of bed. “He gets up,” continues the Narrator, “sets off to The Bastion, where everyone agreed to go in case of trouble.” There's nowhere to go except a door-shaped hole in the hole so that's where the analogue stick takes him. Coloured paving stones fly into a path. “Ground forms up to point the way,” comments the Narrator. “He don't stop to wonder why.”

So begins Bastion, an isometric action-RPG, available for PC or Xbox for just under a tenner. It seems to be the game everyone is talking about at the moment (even a

surprisingly uncritical Yahtzee

) and I can see why. There's lots to love about Bastion, from its gorgeous presentation to the elegance of its mechanics, and, make no mistake, I do love it. Best “just under a tenner” I've spent for a while.

In terms of gameplay, it's a fairly standard action-RPG. You run along, gathering up XP, and laying the smackdown on a variety of rapidly spawning enemies but the various places you visit, are sufficiently streamlined and differentiated that the experience never grows stale. Everything is beautifully detailed and carefully contextualised: you start to recognise the various creatures, and learn something of their background. The places, ruined as they are, all have their own history and the visual device of the forming and breaking pathways creates a atmosphere of change, variety and transience. And there are so many exciting ways of tweaking your character, spending your XP and customising your weapons that you're always finding new ways of approaching the game's challenges. XP is a straightforward bar; every level allows you consume a new “spirit” created in your distillery. These have a range of interesting effects, as well as characterful descriptions and amusing names – my personal favourite being “Stabsinthe.” Over the course of the game the Kid acquires a small arsenal of weapons, ranging from his “old friend” (a big hammer) to a chaos cannon, all of which play slightly differently, and have a wide array of strengths, and weaknesses, and can be upgraded by collecting memory fragments, found by exploring the world and defeating monsters. You get a choice of two alternative paths per weapon, and a total of five upgrades, each requiring the appropriate material and enough fragments, but the game is wonderfully liberating in letting you change your upgrades around once you've paid the cost. This encourages experimentation and makes you genuinely fond of your equipment – since you're never just swapping one generic longsword of the badger for another generic broadsword of the piranha. The Bastion serves as the main gameplay hub. From here, you'll explore the game map while bringing back the cores and fragments that allow you to build, and then upgrade, the various structures of The Bastion. The pattern is slightly repetitive, and the plot is basically a series of not very subtle MacGuffin hunts, but the pleasure of restoring The Bastion, and deciding whether you want to build a shrine or upgrade your forge, keeps the experience engaging. The emphasis seems to be very much on choice. You can choose to worship one of the Gods, for example, when you've built a shrine, which will make battles harder (in a variety of ways) but give you greater rewards. The point is, this offers you an extensive degree of customisation for your game experience, right down to how challenging, and in what ways, you want to make it. The thing is, the gameplay is sleek and non-offensive, but at its heart its a straight-down-the-line action-RPG. You go places, you collect things, you kill stuff, you get more powerful, you make your equipment more powerful, you rinse and repeat. But there's been such an amount of love and attention poured into the game that playing is a constant delight. I absolutely loved the colourful, shifting world, the charming descriptions of pretty much everything you encounter, and the soundtrack is a little piece of a perfection all on its own, contributing such a lot to the mood of the game. There's even a song:

youtube

This song absolutely typifies Bastion: you have the juxtaposition of the country guitar and the Eastern strings, melding two unlikely traditions, deceptively simple lyrics underscoring a theme of racial division, and that poignant combination of beauty and melancholy, bitterness and hope.

The story of Bastion, which I will shall try to explain without too much spoilering, concerns the mysterious “Calamity” which has led to the shattered world in which the Kid first awakes. As you progress through the game, your goals are simple enough: find survivors, restore The Bastion, stay alive. But the Narrator mixes commentary with memory so that the further into the future you get, the more you understand about the past. I've mentioned the Narrator already – you meet him soon enough, a old man called Rucks – and he is the primary mechanism through which the story is delivered and filtered. And it works astonishingly well, bridging the gap between ludo and narrative (ouch, can't believe I wrote that) in a coherent and cohesive way. Rucks tells you about the places you visit and the people you encounter, making the world, and its ruination, feel real, but he also validates and contextualises your in-game actions. For example, the first time I missed my step and plummeted off the edge of a path, he observed “And then he falls to his death. I'm just fooling” which made me chuckle and on subsequent occasions, he would throw out some circumstance-specific statement, such as “Kid had to watch his step in The Cauldron” or whatever.

He also makes your game-play choices feel like genuine in-world choices, as the narration seems to dynamically react to how you play. For example, early on you come to a crossroads while searching for one of the cores. I set off randomly in any old direction because there didn't seem any reason to act otherwise: “Kid figured heading down would take him to the core...” explained Rucks. I loved having my gamerish disregard transformed into strategy by the alchemy of narrative. Rucks will also comment on your weapon choices and combinations, and on your general approach to the game, among other things, which, once again, embeds gameplay in storytelling, providing a diegetic framework for the decisions you make. There's also an extent to which it functions almost as a meta-commentary on the tropes of gameplay. As I mentioned earlier, the first weapon you find in the game is your trusty hammer. And, like any action-rpg player, the first thing I did on discovering a weapon was run around in circles, mashing the attack button, until I'd pretty much smashed up every piece of scenery on the screen. “Kid just raged for a while,” said Ruck, darkly.

It is possible, of course, to overstate the value of this device. It is assuredly one of the most successful marriages of gameplay and story I've ever encountered, but not every game can be narrated by a whiskey-voiced cowboy. It's something that works beautifully in Bastion – and makes the game truly something remarkable – but it's not, y'know, the great gameplay/story revolution or whatever.

The other thing that took me by surprise was the decision that hit me at the end of the game. Actually, there were two but the first was a relatively simple one. The second, however, was so vast and morally complex that I actually had to put the gamepad down, walk away and think about it for a bit. That probably sounds either mad or pretentious, or mad and pretentious, but firstly I wasn't prepared to have to make a decision in a “simple” action-RPG and secondly the decision was literally world-changing. And I realised suddenly how much I had come to care for the four companions I'd met in this broken world. They are not voiced, they don't join your party, there are no complicated dialogue trees, or lengthy textual descriptions but somehow they'd become my friends. I was, when I finally made it, happy with my final decision. I don't think, on consideration, I would have done otherwise given the choice again (although, of course, I could always play the game again to see). But it has nevertheless haunted me for days.

I'm going to talk about this decision, and some of the game's stylistic choices, after a massive honking spoiler spoiler spoiler spoiler warning. But if this is as far as you're going to read: I will simply urge you to the play the game. It's delightful. I would probably also recommend you play on Xbox, or with a gamepad, if you have the option since the diagonals are a killer.

So...

yeah...

spoilers...

spoilers...

spoilers...

spoilers...

spoilers....

....

....

....

....

The Calamity comes about because the Caelondians (your people) basically try to genocide the Ura (some other people). Essentially the Caelondians come up with a device that will seal the Ura forever underground, except an Ura sabotages it and this causes the Calamity.

On a very basic level, the Caelondians live in the sky, the Ura live underground but there seem to be massively complex ideological differences underpinning all this as well. The Caelondians seem all into tech, and the Ura are more naturalistic, the Caelondians comercialise their religion, the Ura are offended by graven images (at one point you pick up an adorable Pyth plushie – Pyth being the bull-God of order and commotion, and Zulf, one of your companions, disdains it), and so on and so forth. The thing is, I think the Caelondins are very broadly meant to be associated with the the west and the Ura with the east. They way the Ura dress (long robes) and look (pale and dark haired) suggests this to me, as well as the slightly higher-pitched sound effects and the weaponry they use (like the naginata and the repeating crossbow). I don't mean to get my minority warrior freak on, but I think when you stylistically set up an east-west dichotomy like that you're opening a can of worms that you might not entirely want to be opened. Or rather that you might not be able to deal with appropriately within the limitations of a computer game.

The thing is, there's plenty of evidence that the Caelondians were not so great actually. As a Caelondian, Rucks' narration generally communicates nostalgia and affection, and a yearning to go back to the way things were, but there's plenty of darkness in there too. There's a general suggestion of moral and social decay, and the lives of the Kid, Zia and Zulf have been far from happy in the city. But both as a westerner, and as the gamer behind the Kid from Caelondia, the Ura are portrayed as being, in many ways, profoundly other. Of course, you transcend this perception of otherness through your friendship with Zia and Zulf but there comes a point when you go up against hordes of interchangeable Ura, waving naginata at you, and I genuinely felt like I'd been sent forth to kill the nasty foreigners. I don't know if it was meant to be making me deliberately uncomfortable but I would have been more at ease with the moral message if there'd been less of a real world race correspondence. As a game about racial division it's interesting and at least reasonable subtle (since the cultural hostility is deep and endemic and nobody at any point says how much they hate those white-faced Ura), but as a game about how we should be nicer to Japanese people it's a bit embarrassing. I just think it's inherently problematic to use stylistic markers associated with the Western perception of the East to denote “the exotic other.”

The Ura, incidentally, are trying to stop you from restoring The Bastion and, once Zulf discovers the truth about the Calamity, he betrays you to rejoin his people. It's hard to really blame Ura for being a bit pissed off about the proposed genocide, but, again, I felt the moral pendulum started swinging a bit awkwardly at the point at which, once their plan fails and you overcome them, they turn on Zulf and attack him too. Those foreigners, eh? No loyalty or honour. Again, I understand that the situation is meant to be morally ambiguous, with good and bad on both sides, and the tragedy being ultimately a very human tragedy of individuals making mistakes rather than a specific villain ruining the world – but, once again, that ambiguity would be more meaningful if hadn't ended on a gigantic cop-out. Having Zulf's own people turn on him when things go wrong essentially undermines his motivation for trying to save them in the first place. Also, this leads to the noble-hearted Caelondian saving the Ura from his own treacherous people.

The reason Rucks is so eager to restore The Bastion is because it contains a fail-safe device that essentially re-sets time, putting everything back to how it was before the calamity. But, you also discover, The Bastion has one other function: it can jettison the city core, transforming it into a sort of fully functional floating city that could take you anywhere. The choice you face, therefore, is putting the world back to the way it was, saving thousands upon thousands of morally degenerate genocidal racists (or “lives” if you prefer) or live in the world as is, with your new found friends in your floating city. Okay, I've been slightly harsh on the morally degenerate genocidal racist score: there is no real evil in Bastion, just mistakes, humanity and bad choices. The point is, it's a city full of people, and there's no evidence the Calamity is an inevitable consequence of, well, anything . Also, on the eve of the calamity, Zulf had just proposed to the woman he loved (a Caelondian) so going back to the past would not be a future without hope or happiness for some, perhaps for many.

I have to admit, race concerns aside, I found this decision genuinely fascinating. It came slightly out of left field because the fluid, emergent form of the game in general hadn't led me to expect a sudden either/or, but it was embedded so well in the context of everything preceding it, that I was stymied. I've been reading around in the Internet since I made my decision and one popular (but stupid) opinion seems to be that it's about personal selflessness, putting the needs of others above your own, saving thousands of lives at the cost of maybe three. How Peter Molyneux. Thankfully, I believe the decision is much more interesting than that and, in the end, I jettisoned the core. I will not lie: love did play a part in my decision. I wanted the Kid to be with Zia, and Ruck and Zulf. But one of the major themes of the game seemed to me to be the importance of memory: Ruck's narration, the act of constructing memorials for the lost, the literal collecting of memory shards to upgrade your character, and, of course, the constantly shifting, reforming and re-shaping of the world itself. From the old ruins, come new paths. This is how the past shapes the future. And if we do not remember the mistakes we have made, then we are doomed to repeat them.

Of course that's just my take. It's deliciously arguable either way. And it's possible that I'm just over-compensating for the unbearable guilt of having sacrificed thousands of imaginary people to fly around a world with my friends: the cowboy, the singer and the survivor.

Either way, it was deeply refreshing to play an RPG in which I neither defeated a villain nor saved the world.Themes:

Computer Games

,

CRPGs

,

Minority Warrior

~

bookmark this with - facebook - delicious - digg - stumbleupon - reddit

~Comments (

go to latest

)

valse de la lune

at 06:39 on 2011-09-07I'll post more thought on this later; like you I found the ending quite moving and I have Many Thoughts about Bastion. But--what did you think of Zia getting a voice (literally!) to speak with only at the very end, when hitherto you only heard her in the song and the narrative is entirely shaped by Ruck?

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 09:11 on 2011-09-07I, too, found the ending very moving - and I've been thinking about the game a lot since I've finished it, which is comparatively rare for me.

I wasn't actually mad keen on Zia getting a voice, it was a bit sudden and incongruous and I felt it impacted too much on the final decision. I mean it seemed to setting it up to be Rucks versus Zia, and whether you want to save lives or shack up with a girl you fancy. I mean I think there are many interesting philosophical reasons to jettison the core; because it Zia's life was sad before is not necessarily one of them.

Looking forward to your thoughts :)

permalink

-

go to top

valse de la lune

at 14:01 on 2011-09-07It's kind of irritating that she finally gets to say something for herself and it's mostly to confirm her role as a kinda-sorta designated romantic interest.

Anyway, about the Ura, I'm... very touchy about fantasy analogues for racial minorities, for obvious reasons--and doubly so when the analogue in question is so fucking pasty I thought they were vampires. It's intellectually dishonest and doesn't read to me as anything like a serious attempt to tackle the issue of colonialism. The final bits where they show up to do their noble savages thing made me

really angry

(what the hell is this even supposed to be? A mix of Roma and what, Zulu warriors? They didn't read as Chinese to me; the style of dress is way off; see Zia's head scarf. If, however, they were meant to be an East Asian analogue, well, I'm going to mail Supergiant rotten fish). It's out of place for such a cute game and I wish the author(s) hadn't taken this angle at all. Please writers, unless you have the intelligence and perspective and insight of say Octavia Butler, stop it right the hell now with the race thing.

Stop it forever.

Fucking Minority Warriors.

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 15:41 on 2011-09-07For what it's worth, I don't think they were specifically trying to write an East versus West thang. I mean, it's clearly just a fantasy story with a racial division theme, not somebody trying to be insightful about the west being a bunch of big meanies.

I did, however, read the style of the Ura as being faintly Japanese but that could just mean the racist here is me - the way they dress suggested kimono, they seem to fight with nagainatas, and everything you learn about their culture suggests that it's quite Mysterious TM and Ritualistic.

I mean, for God's sake Kyra, it's just a game, and it's cuuuute, so I could have totally over-reacted but I just worry that every time a text wants to mark exoticism or difference they, consciously or otherwise, reflect perceptions of real world difference.

I mean they could have made the Caelondians bears and the Ura moles, y'know. Or whatever. I just sort of felt they were heading towards Cowboys Versus the Japanese without really being aware of it.

Loved the game though, loved it.

permalink

-

go to top

valse de la lune

at 16:22 on 2011-09-07No, I'm not exactly commenting on the Ura bouncing off what you've said--my remarks are based on my own reactions (i.e. I don't think you're overthinking this etc), and the combination of "marginalized people" and "noble savages" hugely puts me off. Without that I could have liked the game without reservations. :/

I must say that the PC port was pretty well done, with higher-res art assets for PC resolutions and everything.

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 16:50 on 2011-09-07Like I say, it's really not my place to point at depictions of other races and made loud minority warrior comments; I just felt a bit uncomfortable and, as you've pointed out, the whole noble savage thing on its own is the ick.

I played on Xbox from the comfort of sofa - the graphics were lovely enough it probably didn't do it justice, admiring them from the other side of the room.

permalink

-

go to top

valse de la lune

at 17:09 on 2011-09-10One more thing: I can't be the only one who's put the ending theme on repeat and listened to it like a gazillion times, right?

:'(

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 22:51 on 2011-09-10Guilty.

I was listening to it while writing the review.

permalink

-

go to top

Bryn

at 17:18 on 2013-03-19

Look, new thing!

Female protagonist is a nice change, especially in light of some

points

raised about Bastion's use of gender. I hope they do as good a job writing for this character as they did for the guys in Bastion.

permalink

-

go to top

Wardog

at 14:39 on 2013-03-23I am super excited for this. I loved Bastion.

permalink

-

go to top

http://lalunatique.livejournal.com/

at 02:04 on 2013-10-22Confession time: I found out about Bastion through this article and played it just so I could get past the spoiler alerts. (Of course the game itself sounded appealing, otherwise I wouldn't have minded being spoiled.) The story is short and sweet, and gameplay was hugely enjoyable. The final choice left me boggled and thoughtful, too.

I also chose to dump the core, for several reasons. Like you said, without memory people will just make the same mistakes. Rucks himself admitted there was no guarantee the Calamity wouldn't happen all over again. And if it wasn't the same chain of events it would be something else, given the hatred that existed. The way I saw it, the least-worst choice in this utterly crapsack situation was to preserve the memories and mistakes of the four fatally flawed failures on board the Bastion so they can travel around telling people to avoid the pratfalls they and their civilizations made.

In the end I just didn't buy Rucks' idea for the eternal reset button, and I hated how it served as justification for the Kid's slaughtering countless creatures and people. With this ending they're all going to have to live with what they did--Rucks for being complicit in the Calamity in the first place and for cheerleading the Kid through the killing fields, Zulf for seeking mindless revenge in the shattered remains of his world, Zia for her selfishness in not giving a shit about the countless people who died, and the Kid for the destruction he caused to no account. I hope it hurts them all. I hope it hurts good, because pain is the only natural and moral reaction to all they've seen and done.

Perhaps paradoxically, I also wish all of them good lives, lots of adventure, companionship, and love. I hope their mistakes have made them wiser, and I hope they'll spread that wisdom to others so not only they but the world can grow and learn.

As an Asian woman I give my Official Minority Stamp of Approval to the awful handling of race and gender in Bastion, wonderful as the game and story are. The Ura did in fact strike me as Asian-influenced--their culture seemed interesting and I would have liked to learn more, but this external view didn't do much other than exoticize them in the tired old tropes. Also I really could have done without having to mow through hordes and hordes of them. At the end of all that, rescuing Zulf for me was more about tiredness than anything else; I wanted my Kid to be tired of all the death and destruction when there had been too much of both already, and no longer caring if he died without the almighty Ram (not the first Ura invention in the game to be appropriated by Caelondians.).

Also, Zia. Ugh, Zia. The character, together with Zulf, managed to combine Racefail and Genderfail into a giant ball of suck. Because obviously the males of the Other Culture (plus females who are not really characters but interchangeable, disposable sprites) are threats to fight against, but the females are harmless and docile love interests. OBVIOUSLY. At the very least she wasn't kidnapped, but it also seems (though it was vague) that she managed to get herself locked up anyway, because everyone knows Those People will turn on their own at the drop of a hat. I felt like throwing my keyboard across the room from the offensiveness of it all, all the more because the overall story is compelling and engaging--my frustration was all the greater because I'd gotten hooked, whereas if the story had alienated or bored me I would just have rolled my eyes.

So thanks for introducing me to this great, thought-provoking game. I might have spent too many hours of my life fiddling with the keyboard and mouse controls and given myself repetitive stress injury, but with the increased blood pressure from some aspects of the story, my body was probably tricked into thinking it was getting a much-overdue workout.

0 notes

Text

The Minds of Plants

At first glance, the Cornish mallow (Lavatera cretica) is little more than an unprepossessing weed. It has pinkish flowers and broad, flat leaves that track sunlight throughout the day. However, it’s what the mallow does at night that has propelled this humble plant into the scientific spotlight. Hours before the dawn, it springs into action, turning its leaves to face the anticipated direction of the sunrise. The mallow seems to remember where and when the Sun has come up on previous days, and acts to make sure it can gather as much light energy as possible each morning. When scientists try to confuse mallows in their laboratories by swapping the location of the light source, the plants simply learn the new orientation.

What does it even mean to say that a mallow can learn and remember the location of the sunrise? The idea that plants can behave intelligently, let alone learn or form memories, was a fringe notion until quite recently. Memories are thought to be so fundamentally cognitive that some theorists argue that they’re a necessary and sufficient marker of whether an organism can do the most basic kinds of thinking. Surely memory requires a brain, and plants lack even the rudimentary nervous systems of bugs and worms.

However, over the past decade or so this view has been forcefully challenged. The mallow isn’t an anomaly. Plants are not simply organic, passive automata. We now know that they can sense and integrate information about dozens of different environmental variables, and that they use this knowledge to guide flexible, adaptive behaviour.

For example, plants can recognise whether nearby plants are kin or unrelated, and adjust their foraging strategies accordingly. The flower Impatiens pallida, also known as pale jewelweed, is one of several species that tends to devote a greater share of resources to growing leaves rather than roots when put with strangers – a tactic apparently geared towards competing for sunlight, an imperative that is diminished when you are growing next to your siblings. Plants also mount complex, targeted defences in response to recognising specific predators. The small, flowering Arabidopsis thaliana, also known as thale or mouse-ear cress, can detect the vibrations caused by caterpillars munching on it and so release oils and chemicals to repel the insects.

Plants also communicate with one another and other organisms, such as parasites and microbes, using a variety of channels – including ‘mycorrhizal networks’ of fungus that link up the root systems of multiple plants, like some kind of subterranean internet. Perhaps it’s not really so surprising, then, that plants learn and use memories for prediction and decision-making.

What does learning and memory involve for a plant? An example that’s front and centre of the debate is vernalisation, a process in which certain plants must be exposed to the cold before they can flower in the spring. The ‘memory of winter’ is what helps plants to distinguish between spring (when pollinators, such as bees, are busy) and autumn (when they are not, and when the decision to flower at the wrong time of year could be reproductively disastrous).

In the biologists’ favourite experimental plant, A thaliana, a gene called FLC produces a chemical that stops its little white blooms from opening. However, when the plant is exposed to a long winter, the by-products of other genes measure the length of time it has been cold, and close down or repress the FLC in an increasing number of cells as the cold persists. When spring comes and the days start to lengthen, the plant, primed by the cold to have low FLC, can now flower. But to be effective, the anti-FLC mechanism needs an extended chilly spell, rather than shorter periods of fluctuating temperatures.

This involves what’s called epigenetic memory. Even after vernalised plants are returned to warm conditions, FLC is kept low via the remodelling of what are called chromatin marks. These are proteins and small chemical groups that attach to DNA within cells and influence gene activity. Chromatin remodelling can even be transmitted to subsequent generations of divided cells, such that these later produced cells ‘remember’ past winters. If the cold period has been long enough, plants with some cells that never went through a cold period can still flower in spring, because the chromatin modification continues to inhibit the action of FLC.

But is this really memory? Plant scientists who study ‘epigenetic memory’ will be the first to admit that it’s fundamentally different from the sort of thing studied by cognitive scientists. Is this use of language just metaphorical shorthand, bridging the gap between the familiar world of memory and the unfamiliar domain of epigenetics? Or do the similarities between cellular changes and organism-level memories reveal something deeper about what memory really is?

Both epigenetic and ‘brainy’ memories have one thing in common: a persistent change in the behaviour or state of a system, caused by an environmental stimulus that’s no longer present. Yet this description seems too broad, since it would also capture processes such as tissue damage, wounding or metabolic changes. Perhaps the interesting question isn’t really whether or not memories are needed for cognition, but rather which types of memories indicate the existence of underlying cognitive processes, and whether these processes exist in plants. In other words, rather than looking at ‘memory’ itself, it might be better to examine the more foundational question of how memories are acquired, formed or learned.

When the plant was dropped from a height, it learned that this was harmless and didn’t demand a folding response.

‘The plants remember,’ said the behavioural ecologist Monica Gagliano in a recent radio interview, ‘they know exactly what’s going on.’ Gagliano is a researcher at the University of Western Australia, who studies plants by applying behavioural learning techniques developed for animals. She reasons that if plants can produce the results that lead us to believe other organisms can learn and remember, we should similarly conclude that plants share these cognitive capacities. One form of learning that’s been studied extensively is habituation, in which creatures exposed to an unexpected but harmless stimulus (a noise, a flash of light) will have a cautionary response that slowly diminishes over time. Think of entering a room with a humming refrigerator: it’s initially annoying, but usually you’ll get used to it and perhaps not even notice after a while. True habituation is stimulus-specific, so with the introduction of a different and potentially dangerous stimulus, the animal will be re-triggered. Even in a humming room, you will probably startle at the sound of a loud bang. This is called dishabituation, and distinguishes genuine learning from other kinds of change, such as fatigue.

In 2014, Gagliano and her colleagues tested the learning capacities of a little plant called Mimosa pudica, a creeping annual also known as touch-me-not. Its name comes from the way its leaves snap shut defensively in response to a threat. When Gagliano and her colleagues dropped M pudica from a height (something the plant would never have encountered in its evolutionary history), the plants learned that this was harmless and didn’t demand a folding response. However, they maintained responsiveness when shaken suddenly. Moreover, the researchers found that M pudica’s habitation was also context-sensitive. The plants learnt faster in low-lit environments, where it was more costly to close their leaves because of the scarcity of light and the attendant need to conserve energy. (Gagliano’s research group was not the first to apply behavioural learning approaches to plants such as M pudica, but earlier studies were not always well-controlled so findings were inconsistent.)

But what about more complex learning? Most animals are also capable of conditioned or associative learning, in which they figure out that two stimuli tend to go hand in hand. This is what allows you to train your dog to come when you whistle, since the dog comes to associate that behaviour with treats or affection. In another study, published in 2016, Gagliano and colleagues tested whether Pisum sativum, or the garden pea, could link the movement of air with the availability of light. They placed seedlings at the base of a Y-maze, to be buffeted by air coming from only one of the forks – the brighter one. The plants were then allowed to grow into either fork of the Y-maze, to test whether they had learned the association. The results were positive – showing that the plants learned the conditioned response in a situationally relevant manner.

The evidence is mounting that plants share some of the treasured learning capacities of animals. Why has it taken so long to figure this out? We can start to understand the causes by running a little experiment. Take a look at this image. What does it depict?

Most people will respond either by naming the general class of animals present (‘dinosaurs’) and what they are doing (‘fighting’, ‘jumping’), or if they are dinosaur fans, by identifying the specific animals (‘genus Dryptosaurus’). Rarely will the mosses, grasses, shrubs and trees in the picture get a mention – at most they might be referred to as the background or setting to the main event, which comprises the animals present ‘in a field’.

In 1999, the biology educators James Wandersee and Elisabeth Schussler called this phenomenon plant blindness – a tendency to overlook plant capacities, behaviour and the unique and active environmental roles that they play. We treat them as part of the background, not as active agents in an ecosystem.

Some reasons for plant blindness are historical – philosophical hangovers from long-dismantled paradigms that continue to infect our thinking about the natural world. Many researchers still write under the influence of Aristotle’s influential notion of the scala naturae, a ladder of life, with plants at the bottom of the hierarchy of capacity and value, and Man at the peak. Aristotle emphasised the fundamental conceptual divide between immobile, insensitive plant life, and the active, sensory realm of animals. For him, the divide between animals and humankind was just as stark; he didn’t think animals thought, in any meaningful way. After the reintroduction of such ideas into Western European education in the early 1200s and throughout the Renaissance, Aristotelean thinking has remained remarkably persistent.

It’s often adaptive for humans to treat plants as object-like, or simply filter them out.

Today, we might call this systematic bias against non-animals zoochauvinism. It’s well-documented in the education system, in biology textbooks, in publication trends, and media representation. Furthermore, children growing up in cities tend to lack exposure to plants through interactive observation, plant care, and a situated plant appreciation and knowledge by acquaintance.

Particularities of the way our bodies work – our perceptual, attentional and cognitive systems – contribute to plant blindness and biases. Plants don’t usually jump out at us suddenly, present an imminent threat, or behave in ways that obviously impact upon us. Empirical findings show that they aren’t detected as often as animals, they don’t capture our attention as quickly, and we forget them more readily than animals. It’s often adaptive to treat them as object-like, or simply filter them out. Furthermore, plant behaviour frequently involves chemical and structural changes that are simply too small, too fast or too slow for us to perceive without equipment.

As we are animals ourselves, it’s also easier for us to recognise animal-like behaviour as behaviour. Recent findings in robotics indicate that human participants are more likely to attribute properties such as emotion, intentionality and behaviour to systems when those systems conform to animal or human-like behaviour. It seems that, when we’re deciding whether to interpret behaviour as intelligent, we rely on anthropomorphic prototypes. This helps to explain our intuitive reluctance to attribute cognitive capacities to plants.

But perhaps prejudice is not the only reason that plant cognition has been dismissed. Some theorists worry that concepts such as ‘plant memory’ are nothing but obfuscating metaphors. When we try to apply cognitive theory to plants in a less vague way, they say, it seems that plants are doing something quite unlike animals. Plant mechanisms are complex and fascinating, they agree, but not cognitive. There’s a concern that we’re defining memory so broadly as to be meaningless, or that things such as habituation are not, in themselves, cognitive mechanisms.

One way of probing the meaning of cognition is to consider whether a system trades in representations. Generally, representations are states that are about other things, and can stand in for those things. A set of coloured lines can form a picture representing a cat, as does the word ‘cat’ on this page. States of the brain are also generally taken to represent parts of our environment, and so to enable us to navigate the world around us. When things go awry with our representations, we might represent things that aren’t there at all, such as when we hallucinate. Less drastically, sometimes we get things slightly wrong, or misrepresent, parts of the world. I might mishear lyrics in amusing ways (sometimes called ‘mondegreens’), or startle violently thinking that a spider is crawling on my arm, when it’s only a fly. The capacity to get it wrong in this way, to misrepresent something, is a good indication that a system is using information-laden representations to navigate the world; that is, that it’s a cognitive system.

When we create memories, arguably we retain of some of this represented information for later use ‘offline’. The philosopher Francisco Calvo Garzón at the University of Murcia in Spain has argued that, for a physical state or mechanism to be representational, it must ‘stand for things or events that are temporarily unavailable’. The capacity for representations to stand in for something that’s not there, he claims, is the reason that memory is taken to be the mark of cognition. Unless it can operate offline, a state or mechanism is not genuinely cognitive.

The mallow learns a new location when plant physiologists mess with its ‘head’ by changing the light’s direction.

On the other hand, some theorists allow that certain representations can only operate ‘online’ – that is, they represent and track parts of the environment in real time. The mallow’s nocturnal capacity to predict where the Sun will rise, before it even appears, seems to involve ‘offline’ representations; other heliotropic plants, which track the Sun only while it is moving across the sky, arguably involve a kind of ‘online’ representation. Organisms that use only such online representation, theorists say, might still be cognitive. But offline processes and memory provide stronger evidence that organisms are not just responding reflexively to their immediate environment. This is particularly important for establishing claims about organisms that we are not intuitively inclined to think are cognitive – such as plants.

Is there evidence that plants do represent and store information about their environment for later use? During the day, the mallow uses motor tissue at the base of its stalks to turn its leaves towards the Sun, a process that’s actively controlled by changes in water pressure inside the plant (called turgor). The magnitude and direction of the sunlight is encoded in light-sensitive tissue, spread over the mallow’s geometric arrangement of leaf veins, and stored overnight. The plant also tracks information about the cycle of day and night via its internal circadian clocks, which are sensitive to environmental cues that signal dawn and dusk.

Overnight, using information from all these sources, the mallow can predict where and when the Sun will rise the next day. It might not have concepts such as ‘the Sun’ or ‘sunrise’, but it stores information about the light vector and day/night cycles that allows it to reorient its leaves before dawn so that their surfaces face the Sun as it climbs in the sky. This also allows it to re-learn a new location when plant physiologists mess with its ‘head’ by changing the direction of the light source. When the plants are shut in the dark, the anticipatory mechanism also works offline for a few days. Like other foraging strategies, this is about optimising available resources – in this case, sunlight.

Does this mechanism count as a ‘representation’ – standing in for parts of the world that are relevant to the plant’s behaviour? Yes, in my view. Just as neuroscientists try to uncover the mechanisms in nervous systems in order to understand the operation of memory in animals, plant research is beginning to unravel the memory substrates that allow plants to store and access information, and use that memory to guide behaviour.

Plants are a diverse and flexible group of organisms whose extraordinary capacities we are only just beginning to understand. Once we expand the vista of our curiosity beyond animal and even plant kingdoms – to look at fungi, bacteria, protozoa – we might be surprised to find that many of these organisms share many of the same basic behavioural strategies and principles as us, including the capacity for kinds of learning and memory.

To make effective progress, we need to pay careful attention to plant mechanisms. We need to be clear about when, how and why we are using metaphor. We need to be precise about our theoretical claims. And where the evidence points in a direction, even when it is away from common consensus, we need to boldly follow where it leads. These research programmes are still in their infancy, but they will no doubt continue to lead to new discoveries that challenge and expand human perspectives on plants, blurring some of the traditional boundaries that separated the plant and animal realms.

Of course, it’s a stretch of the imagination to try to think about what thinking might even mean for these organisms, lacking as they do the brain(mind)/body(motor) divide. However, by pushing ourselves, we might end up expanding the concepts – such as ‘memory’, ‘learning’ and ‘thought’ – that initially motivated our enquiry. Having done so, we see that in many cases, talk of plant learning and memory is not just metaphorical, but also matter-of-fact. Next time you stumble upon a kerbside mallow bobbing in the sunlight, take a moment to look at it with new eyes, and to appreciate the window this little weed provides into the extraordinary cognitive capacities of plants.

Laura Ruggles is a philosophy PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide in Australia.

Kathryn McNeer, LPC specializes in Couples Counseling Dallas with her sound, practical and sincere advice. Kathryn's areas of focus include individual counseling, relationship and couples counseling Dallas. Kathryn has helped countless individuals find their way through life's inevitable transitions; especially that tricky patch of life known as "the mid life crisis." Kathryn's solution-focused, no- nonsense counseling works wonders for men and women in the midst of feeling, "stuck," or "unhappy." Kathryn believes her fresh perspective allows her clients find the better days that are ahead. When working with couples, it is Kathryn's direct yet non-judgmental approach that helps determine which patterns are holding them back and then helps them establish new, more productive patterns. Kathryn draws from Gottman and Cognitive behavioral therapy. When appropriate Kathryn works with couples on trust, intimacy, forgiveness, and communication.

0 notes

Link

AN INTERVIEW WITH SHAUN TAN

There aren't many artists who have the ability to both write and illustrate their own work; but Shaun Tan is an exception. The Australian artist began working as a freelance illustrator, collaborating with well-known authors, Gary Crew and John Marsden before eventually turning his hand to writing his own books which include: The Lost Thing (1999); The Red Tree (2001); The Arrival (2006) and his latest work, Tales From Outer Suburbia, a collection of stories set in the remote Western Australia, where he grew up. Filled with magical realism, humour and poignancy, it is also the longest book he has written and comes after his acclaimed and controversial The Arrival, a 128-page picture book documenting the migrant experience, without using any words at all. See http://www.shauntan.net/.

To start with, could you tell me about your background as an artist? Have you been drawing and writing since you were young? When did you decide that you wanted to be writer/book illustrator?

I think I'm like most people, I don't remember when I started drawing: most likely as a crayon-gripping toddler. I think everyone starts out as an avid drawer, it's just a primal kind of instinct, and raises the more interesting question: "When do people stop drawing?" I guess the interest wanes, or is replaced by other skills. Some people, like myself, just keep doing it as a form of extended play from early childhood, using this simple craft to express complex adult concerns.

But - to answer the question! - I did exhibit some early talent as a child, or at least found a way of drawing 'convincing' images by the age of three, so that a bird really looked like a bird, rather than a bird-ish scribble. By five I think I understood a set of techniques and tricks at a basic level, that drawing was about finding simple elements in things. My parents, while not artists themselves, both had an interest in the visual arts (my Mum could draw quite well and my Dad is an architect), and I think their encouragement of drawing was far more important than any innate skill. It was always fun to draw something and then show it to them - they would always act incredibly surprised and amazed! Part of a parent's job description, I think. My brother's talent at the age of six was to collect, identify and label rocks: he's now a very successful geologist. I'm sure it's because of that same unqualified encouragement.

The interest in writing probably came from being read to as a child, both at home and school. I think I was quite a late reader and writer, but did find books fascinating, both as stories and physical objects, so I was compelled to create my own. Some of these ended up in the school library, being quite good imitations of real books, which other kids could borrow. They were usually stories about adventurers travelling to another world, finding treasure, and blowing everything up, inspired mostly by movies and TV, with titles like 'The Land Beneath the Sea' and 'Mission to Mars'. One or two went missing from the school library, which may or may not be a good thing as far as my artistic reputation goes.

I had no serious intentions of becoming a writer or illustrator, even though I thought that would be a fantastic job. Growing up in the West Australian suburbs, it simply did not seem like a real occupation. It was only in my late teens that I became very focused on two things: painting landscapes and writing science fiction short stories. I always thought I might end up as a painter or writer, but for a long time saw these as completely separate practices, somewhat incompatible. Generally, I did not know what career I might pursue, and going into university, it was a toss up between biotechnology (another big interest), and an arts degree. I chose the latter.

As a student I funded my studies in part by picking up various small illustration jobs, such as brochures for campus departments and the university's graduate magazine. I was also having some success illustrating stories in science fiction magazines. When I finished my degree, I still did not have any career convictions, but decided to try doing this kind of freelance illustration full-time for about a year, and see if I could make a go of it. It turned out that I could, especially illustrating children's educational and trade books, and fantasy novel covers. That eventually led into picture books, which is where I am at currently, with some recent forays into theatre and film.

A lot of your work deals with displacement. The Lost Thing and the main character in The Arrival: travelling through a foreign land and learning a new way of life. Many of your illustrations also show the characters as miniscule in comparison to the landscape which they inhabit. Where does this interest come from? Do you, like your characters, share a general sense of disconnected-ness from the world?

That's an interesting observation: I'm not so consciously aware of my preoccupations until they resolve into stories and images, so it's a complex one to answer. A psychologist might have a better crack at that! I just find myself strongly attracted, in an empathetic way, to images of isolated figures moving through vast, often confounding landscapes. My intellectual self would say that this is a metaphor for a basic existential condition: we all find ourselves in landscapes that we don't fully understand, even if they are familiar, that everything is philosophically challenging. There is also an idea that any creative thinking carries some problem of identity and meaning, that individuality needs to be endless negotiated, that we are always trying to figure out how we connect to the things around us.

I also always have this sense - perhaps gleaned from science fiction - that our current time and place is quite accidental, one of many possible alternatives, and also that humans are not at the centre of the universe. I grew up in a peripheral suburb of metropolitan Perth, one of the most isolated cities in the world, surrounded by the Indian Ocean on one side and flat, semi-arid bush on the other. Our world was (and still is) a small human incursion into something enormous, ancient, quiet and mysterious: small houses surrounded by dunes and dark, tangled trees; parks and schoolyards populated mainly by crows, parrots and prehistoric-looking bugs. That's since changed as huge malls and carparks have moved in, but the basic fact of a 'transplanted' world remains, one with an unclear sense of place or history. It's full of stuff but it's all somehow insubstantial.

A lot of my early work, whether paintings or stories, have at there core some issue of disconnection between the natural and built environment, which I think is actually a defining characteristic of our time. It's most clearly stated in The Rabbits for instance; and implicitly in The Lost Thing with its awkward and depressing world-by-numbers. That same feeling filters into all sorts of other ideas and themes, a sense of disconnection between people in relationships, issues of cultural misunderstanding, gaps between ideology and reality, intentions and results, language and objects. These things are all great fuel for the imagination too. I would go so far as to say that all art and literature is about some kind of disconnection, brokenness or discrepancy.

Do you like to travel and explore different countries/worlds, or are you happier creating worlds of your own?

Well, both really. I get plenty of inspiration from being in unfamiliar places, and being reminded of the different ways people can think and live, that nothing is 'normal'. Interestingly, though, I rarely feel the urge to draw when travelling, as if travelling alone offers enough weirdness. Likewise, I find it much easier to do creative work 'in tranquillity,' back in my studio which feels very plain and prosaic, working best when little else is going on. Travelling and drawing are very similar activities, in that they force you to look at everything carefully: one is an outward adventure, the other an inward adventure. They are both equally interesting and enjoyable, as well as sometimes being difficult pleasures.

If you could visit any fantasy world, what one would it be?

As a younger person, I would have loved to enter a Tolkien-esque world (and could easily pass for a hobbit too!), and some of the imaginary worlds I was drawing as a teenager, but I don't really have those kind of escapist longings any more. More and more I see fantasy worlds - as in The Arrival - as a way of tapping into the real world, of trying to understand reality better through a speculative lens. If I was to visit that world, I would immediately lose my bearings, like entering a metaphor without its real-world anchorage. I prefer to visit using only a pencil on paper.

A lot of the fantasy worlds that fascinate me the most are ones I would not like to visit at all, like Orwell's 1984, Swift's Gulliver's Travels or McCarthy's The Road. Once again, I'm interesting in places where things are somehow broken or disconnected.

Many of your illustrations are montages of scraps from the everyday that might normally be disregarded or thrown away: stamps; receipts; notes; newspaper headlines. Are you a collector? Do you have an interest in highlighting and preserving these transient objects?

Yes, I do. I'm very interested in things that are overlooked, and in trying to find value in things that are not considered valuable. Collage also introduces an important element of random chance into an image, much like a good brush mark, it's not entirely controlled. It's also a good way to break the 'surface tension' of a blank canvas - just start sticking things on, almost without letting conscious decision-making get in the way.

I do have a tendency to collect things, which I have to control a little bit, limiting it to things that are actually useful to avoid being a pack rat. I have a large cardboard box full of small papery bits, which are always useful. I also have a collection of disposable books and magazines that I use as collage material. The less this material has to do with anything aesthetic, the more useful it seems to be - hence lots of physics, maths and engineering textbooks. In my picture book The Lost Thing, this collage helped develop the central theme of the story, of what happens when playfulness enters a world that only knows calculated certainty.

There's also a lot of optimism in your books, particularly The Red Tree. Similarly, some of the stories in Tales From Outer Suburbia are critical of the paranoia that exists as a result of the 'War on Terrorism'. Do you like to assure your readers or at least let them know that the world is really not out to get them?

I feel no need at all to reassure readers or myself of anything, I'm just trying to be realistic. I don't have a message as such, just some recurring observations, which leave me feeling a little ambivalent actually. The story 'Amnesia Machine' [from Tales From Outer Suburbia] really laments the way mass media can degrade an otherwise good democratic system - and that people fall for it every time, without seeming to learn any broad lessons. But just after that is the story about how citizens find a way to cleverly disarm an absurd government policy (by literally disarming missiles) and being compassionate and conscientious, by refusing to be afraid. I feel that both of these are realistic representations, that there is a constant tension in the world between ignorant acceptance and a higher consciousness (which requires effort). This is also a tension that exists within us as individuals, competing forces of darkness and light, both of which need to be acknowledged.

Many of your characters have no names: the main character in The Lost Thing is referred to merely as "a thing," for example. Do you not name your characters on purpose? Do you think that not naming gives the work a greater universality?

Yes, I think that's it, trying to find the best universal metaphor. Though it's not really a strategy, it just always feels right to me to have characters that don't have a specific identity, to the point of not even being recognisable creatures.

Your most recent work, Tales From Outer Suburbia, is also your most text-heavy book to date. Did this come as a reaction to your previous book, The Arrival, which featured no writing at all?

I don't see Tales From Outer Suburbia as having any real relation to The Arrival, as they seem to me to be quite different books - it might have been good to produce them under pseudonyms! But as far as creative process goes, you are right, there was a certain reaction going on there. I was often sneaking off to write the stories in Tales in between the long hours of rigorous pencil shading that went into each page of The Arrival, so it became a kind of outlet for pent-up words and conceptual playfulness, as well as humour.

I was keen to try something that was very fragmented and varied, grabbing whatever tools I thought might best do the job, mixing words, images and layout designs. Before being a full-time illustrator, I used to write piles of (unpublished) short stories, so it felt as though I was returning to fairly comfortable territory, and finding a good balance.

Could you ever imagine writing a book without illustrations?

Yes, I can't see why not. Some stories don't need illustrations, and are in fact much better off without them. However, because I tend to use visual images as my starting point, I have a feeling they will always infiltrate anything I do one way or another.

Tales From Outer Suburbia was inspired by your childhood growing up in Western Australia, but you also manage to transform a suburban setting into a place of magic and miracles. In some of the stories, Water Buffalos take up residence in vacant lots and Dugongs appear in backyards. A lot of people imagine suburbia as banal and generic; do you believe it has the potential to be something else?

Yes, anything has the potential to be something else. As a child and teenager, I used to think that the place I lived in was far too boring to comment upon, that all the good, interesting stuff was somewhere else. It was only when I started painting local suburban scenes in my twenties that I realised the subject was not so important, it was how much thought and imagination you applied to it. So a painting of a simple suburban footpath could be as fascinating as the most exotic landscape, given enough emotional investment (I often think of Van Gogh's paintings of a chair for guidance, or Morandi's little groups of bone-coloured bottles, brilliant paintings of banal objects).

Of course, I do introduce a lot of exotic, surrealist elements into my suburban visual stories in a seemingly artificial way, as a kind of 'what if?' exercise, but the initial inspiration for these comes from observing pretty ordinary things; like looking at an overgrown vacant lot, for instance, and asking 'who lives there?,' or a walnut shell and wondering if it would make a good little suitcase, or a TV aerial and imagining people decorating for some special occasion. Suburbia is definitely bland and generic, but there's also a suppressed strangeness there, a culture foreign to itself. And the fact that it does, on the surface, seem uninspiring, or escapes creative attention, means that it's an excellent canvas to be painting (or writing) upon; it's blank, quiet and opens up quite easily to absurd intrusions.

When you are working on a story what tends to come first: the words or the pictures?

It's hard to say, but generally a story is triggered by a visual image, either vaguely sketched, or vaguely imagined in my mind. Words may follow, then another image, then more words, so it's backwards and forwards - each element plays with or against the other, prompting new ideas. Words are good for playing with abstract concepts, summarising storylines and outlining structure. Images seem to bring a kind of mystery and atmosphere that can greatly expand a written idea.

Yet the main thing for me is that one does not 'explain' the other, but more often questions the ambiguities of both word and image. In hindsight, many of the stories in Tales are to do with the slipperiness of understanding or naming things, hence a nameless holiday, a Japanese diver who cannot make himself understood; an exchange student with a name that nobody can pronounce; a water buffalo who points without speaking, and so on. Images build upon the mystery that's already present in language, realising that all these sounds and symbols are quite provisional, and can mean different things to different people.

Finally, what are you working on at the moment?

An animated adaptation of an older picture book The Lost Thing, with a production company based in Melbourne, Pasion Pictures Australia. It's 15 minutes long, and due to be completed at the end of the year; animated digitally with hand-painted textures. I'm responsible for writing, directing and designing much of the film, which has been an interesting learning curve over a period of some years - it's all coming together quite well thanks to a small, dedicated team.

I'm also trying to do a little more painting of large canvases, which use to be my main pastime before illustration took over as a profession. These are not for exhibition or sale, rather a means of keeping in practise, and learning how to see and paint, something that you never really accomplish fully. I still feel very much like an art student every time I pick up a pencil or brush, not entirely knowing how things will end up.

celebrity or !�=3�nT

0 notes