#vue.js tutorial 2019

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Wie Du mit Vue.js richtig durchstartest | Vue.js in a Nutshell In dieser Serie werden wir Vue.js behandeln und verstehen. Wir werden in dieser Serie alles behandeln, was es zu Vue.js zu wissen gibt. In diesem Video ... source

#durchstartest#mit#Nutshell#richtig#vue#vue cdn#vue cli#vue german#vue js#vue js tutorial#vue mastery#vue programmieren lernen#vue tutorial 2019#vue tutorial 2020#vue.js german#vue.js programmieren#vue.js tutorial 2019#vue.js tutorial 2020#vuejs#Wie

0 notes

Photo

The Vue Tutorial (2019) - Learn Vue.js from scratch ☞ https://school.geekwall.in/p/H126-j4wE/the-vue-tutorial-2019-learn-vue-js-from-scratch #vuejs #javascript

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Vue Tutorial (2019) - Learn Vue.js from scratch ☞ http://dev.geekwall.in/4ea6419dc8 #vuejs #javascript

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Vue.js Tutorial for Beginners 2019 - Vue.js Crash Course ☞ http://codequs.com/p/rytMBOrME?utm_source=86 #java BJql0V2nrfN

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Vue.js Tutorial for Beginners 2019 - Vue.js Crash Course ☞ http://codequs.com/p/rytMBOrME?utm_source=86 #code #learntocode #developer ryOU9rirGN

1 note

·

View note

Photo

6 Top JavaScript UI Frameworks & Libraries for 2020

This article was created in partnership with Sencha. Thank you for supporting the partners who make SitePoint possible.

JavaScript is the technology at the heart of today’s snappy and fast web apps. There are countless UI frameworks and libraries for building complex, reactive apps that scale well.

Some will help you write more efficient, maintainable code. Or you need help designing a set of consistent, interoperable, and fast UI components. In almost any situation, you can find an option that does much of the heavy lifting for you. There’s no need to start from scratch and reinvent the wheel.

The most popular JavaScript frameworks available present some common capabilities. In particular, they:

can keep state and view synchronized

offer routing functionality

let developers build, reuse, and maintain user interface components…

… that are efficient and fast to respond to user interaction.

The number of JS frameworks available is high and that number continues to grow. Take a look at these options. I’ve listed both stable, popular libraries and newer options for the curious.

Let’s jump in with a sleek, enterprise-level JavaScript framework — Ext JS by Sencha.

1. Ext JS by Sencha

Need to build a web app that handles large amounts of data, and need powerful, flexible front-end tools for displaying and working with it?

Sencha Ext JS is described as the…

most comprehensive JavaScript framework for building data-intensive, cross-platform web and mobile applications for any modern device. Ext JS includes 140+ pre-integrated and tested high-performance UI components.

Some of these components include:

a HTML5 calendar

grids

trees

lists

forms

menus

toolbars

and much more

Ext JS is a reliable, paid framework that comes with outstanding docs, tutorials, and support packages. Recent tests showed that the Ext JS data grid was 300x faster than leading competitors. In fact, its Virtual Scrolling experience retrieves and shows large quantities of data in under a second.

Advantages of Ext JS include:

quick, smooth development. Enjoy seamless integration between an enterprise framework and state-of-the-art components and tools.

comprehensive set of secure components. You’ll never have to go out of the framework to find any missing widget or functionality.

great design capabilities due to included integrated tools. Sencha Architect offers drag and drop capabilities. Sencha Stencils lets developers mock up, style, prototype and test UI concepts.

awesome unit and end-to-end testing tools with Sencha Test.

a layout manager. Manage the display of data and content across different browsers and screen sizes. A responsive config system adapts the interface to device orientation and browser window sizes.

easy to achieve accessibility compliance with the Ext JS ARIA package

a robust data package that decouples the UI components from the data layer.

You can find out more about Ext JS on the framework’s site.

2. React

React is enormously popular among front-end developers. It’s an open-source JavaScript library for building blazingly fast, interactive UIs. React was first created by Jordan Walke, a software engineer working for Facebook. It was first deployed on Facebook’s newsfeed in 2011, and on Instagram in 2012. It’s used by the likes of Netflix, Airbnb, Instagram, and the New York Times, to name a few.

Reasons for choosing React to power your next project include:

React is quick to learn and use. It’s JavaScript with a small API.

code components are stable and reusable. They’re a breeze to create and maintain using the API’s declarative syntax.

A big company and a strong community support React.

The library is stack agnostic, can also render on the server using Node.js, and on mobile apps with React Native.

3. Angular

Angular is a free, open-source framework by Google that works for both desktop and mobile.

There’s a learning curve, including getting familiar with TypeScript, a superset of JavaScript. Despite that, Angular remains a great framework to work with. Here are some of the reasons for using it:

cross-platform – progressive web apps, native mobile apps, and desktop

offers speed and performance

has great features like filters, two-way data binding, directives, and more

makes available awesome tooling for faster development

has full support from Google and a strong community of developers behind it.

For more details, don’t miss Angular Introduction: What It Is, and Why You Should Use It by Ilya Bodrov-Krukowski.

4. Vue

Vue JS is a free and open-source progressive JavaScript framework created by Evan You. It uses a template syntax (like Angular) and relies on a component-based architecture (like React).

Here’s how Vue describes itself in its own GitHub repository page:

Vue (pronounced /vjuː/, like view) is a progressive framework for building user interfaces. It is designed from the ground up to be incrementally adoptable, and can easily scale between a library and a framework depending on different use cases. It consists of an approachable core library that focuses on the view layer only, and an ecosystem of supporting libraries that helps you tackle complexity in large Single-Page Applications.

Here are some of Vue’s strongest points:

developer-friendly. If you know the languages of the web (HTML, CSS and JavaScript), the Vue docs are all you need to start building right away.

you can integrate it within a project progressively. It easily scales from a library to a full-fledged framework.

small and comes with a super-fast virtual DOM.

has an amazing community behind it, which makes it a stable framework to adopt.

offers great documentation.

If you’d like to delve deeper, read How to Tell If Vue.js Is the Right Framework for Your Next Project by Karolina Gawron.

5. Ember

Released in December 2011 by Yehuda Katz and Tom Dale, Ember is:

A framework for ambitious web developers.

Ember.js is a productive, battle-tested JavaScript framework for building modern web applications. It includes everything you need to build rich UIs that work on any device.

This JavaScript framework is free, open-source, and has a strong community behind it. Here are some of the reasons why Ember is successful among developers:

leverages the convention over configuration approach championed by David Heinemeier Hansson. It aims to lower the number of decisions that a developer has to make (without sacrificing flexibility).

almost all you need to set up your app comes with Ember out of the box.

backwards-compatible.

quick to adopt the latest web standards and JavaScript features.

offers great docs and resources.

6. Svelte 3

Though it’s growing up quickly, Svelte 3 is the new kid on the frameworks block. Rich Harris released Svelte in November 2016 as an open-source project. Version 3 came out in April 2019 and was a complete overhaul.

Svelte works differently from most frameworks listed so far. In particular:

Whereas traditional frameworks like React and Vue do the bulk of their work in the browser, Svelte shifts that work into a compile step that happens when you build your app.

Many frameworks use using techniques like virtual DOM diffing. Instead, Svelte surgically updates the DOM when the state of your app changes. Compiling code creates noticeable performance benefits.

Svelte is quick for beginners to get started with. You can build components without lots of boilerplate code. Just use HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. The Svelte site features beginner-friendly resources. These include a tutorial, examples, and a detailed API for more seasoned Svelte devs. For help and support, you’re invited to join the dedicated Discord server.

Conclusion

Choosing a framework is always a circumstancial decision. It involves paying attention to what your specific project’s challenges are. It also means considering your team’s experience and preferences.

For example, if your team needs to build data-intensive, enterprise-level projects that need a secure, reliable, and comprehensive framework with a large set of components that work well with each other, Ext JS by Sencha is a great option. You’ll never have to go out of the framework to search for components. For projects that start small but need flexibility and scaling capabilities, Vue could work well. And if your front-end team has extensive React expertise, going with React could be your best bet.

Do you have any other JS UI frameworks or library you’d like to suggest? Which ones have you found yourself using the most as a developer? Let us know on Twitter.

Continue reading 6 Top JavaScript UI Frameworks & Libraries for 2020 on SitePoint.

by Maria Antonietta Perna via SitePoint https://ift.tt/31RCs81

1 note

·

View note

Link

Vue.jsの人気がす���いですね。 いくつかの企業はすでにVue.jsを使い始めており、一部はメインのプロダクトに、一部は二次的なプロジェクトに使用しています。 Vue.jsへの関心が高まる中、人気が高いフレームワーク、そしてVue.jsをすでに採用している企業サイトを紹介します。 画像: vuejs.org Google, Apple and Other Users of Vue.js by Luca Spezzano 下記は各ポイントを意訳したものです。 ※当ブログでの翻訳記事は、元サイト様にライセンスを得て翻訳しています。 Vue.jsはGoogleも採用している 先日、Googleの人材募集サイトにアクセスした際に私が注目したのは、Chromeの機能拡張でVue.jsのアイコンがアクティブになったことです! これは、GoogleがVue.jsを使用していることを意味し、私は非常に驚きました。実際ここ数年で、Vue.jsへの関心が高まりましたが、Googleのような会社がすでに使い始めているとは思っていませんでした。 Vue.jsは現在最も注目されているJavaScriptフレームワークの1つで、Vue.jsの詳細については、公式ドキュメントをご覧ください。 人気が高いフレームワークは? Most Loved, Dreaded, and Wanted Web Frameworks Stackoverflow(デベロッパーの最大のコミュニティ)が2019年に行った調査によると、React.jsとVue.jsが最も愛され、最も望まれているフレームワークです。 Vue.jsを信頼している10大企業 Google, Apple, Behance, Oval, Nintendo, Gitlab, 9gag, Font Awesome, Trivago, Trustpilot Vue.jsを実際に使用している企業について調査を始めた結果、世界で有名な企業のいくつかが既にVue.jsを採用している事実が分かりました。 Google まずはGoogle、前述した通り人材募集のページにVue.jsが使用されています。 careers.google.com Apple Appleはプレゼンテーションを必要とせず、SwiftUIのチュートリアルでVue.jsが使用されています。 developer.apple.com/tutorials/swiftui Nintendo 人展度うはゲームに特化した日本最大の企業の1つで、自社のロイヤリティプログラムMy NintendoでVue.jsを使用しているのを見つけました。 my.nintendo.com Behance BehanceはAdobeファミリーの一員で、クリエイティブな作品と出会えるプラットフォームです。WebアプリにVue.jsが使用され、これはメインのプロダクトであることを意味します。 behance.net Oval Money Ovalはヨーロッパで最も有望なスタートアップの1つで、ここ3年で急成長をとげ、ユーザー数は350kを超えています。ファイナンシャルコーチング、投資、計画のためのアプリを提供しています。公式サイトやWebプロジェクトにVue.jsとNuxtを使用しています。 ovalmoney.com Trivago Trivagoは世界最大のホテル検索サイトの1つで、マガジンにNuxtとVue.jsが使用されています。 magazine.trivago.com Font Awesome Font Awesomeは、フロントエンドのデベロッパーやデザイナーによく知られているアイコンサイトで、Vue.jsが使用されています。 fontawesome.com Gitlab Gitlabは主にソフトウェアのエンジニアが利用しているサイトで、ソースコードの管理とモニタリングで最も人気のある1つです。GitlabはVue.jsで開発された単一のアプリケーションとして提供されています。 gitlab.com 9GAG Vue.jsはWeb上で最も人気のあるプラットフォームの1つである9GAGにも使用され、月に1億6000万人以上のユーザーを獲得しています。同社のFacebookページは4100万の「いいね」があり、Instagramには5100万人のフォロワーがいます。 9gag.com Trustpilot Trustpilotは世界最大級の消費者レビューサイトで、世界中の企業のレビューをホストしており、Vue.jsを使用しています。 trustpilot.com いくつかのブログでNetflix、Facebook、AlibabaがVue.jsを使用し始めたという記事を見かけましたが、私はそれを見つけることができませんでした。 Vue.jsを使用しているかは、Chromeの機能拡張で確認できます。 Vue.js devtool -chrome ウェブストア まとめ あなたもお気づきのように、いくつかの大企業はVue.jsを使い始め、一部はメインのプロダクトに、一部は二次的なプロジェクトに使用しています。 これはVue.jsへの関心が高まっていることを意味し、2020年にリリース予定のVue 3.0により、このフレームワークはReactの最大の競合になると思われます。 参考: Vue 3.0 Updates もしあなたがVue.jsを使用している他の大企業を知っているなら、@93lucaspまでメッセージをください。リストを更新します😃😉

0 notes

Text

Pitching Your Writing To Publications

Pitching Your Writing To Publications

Rachel Andrew

2019-08-19T14:00:59+02:002019-08-19T12:28:45+00:00

Recently, I had a chat with Chris Coyier and Dave Rupert over on the Shoptalk Podcast about writing for publications such as Smashing Magazine and CSS-Tricks. One of the things we talked about was submitting ideas to publications — something that can feel quite daunting even as an experienced writer.

In this article, I’m going to go through the process for pitching, heavily based on my own experience as a writer and as Editor in Chief of Smashing. However, I’ve also taken a look at the guidelines for other publications in order to help you find the right places to pitch your article ideas.

Do Your Research

Read existing articles on the site that you would like to write for. Who do they seem to be aimed at? What tone of voice do the writers take? Does the publication tend to publish news pieces, opinion, or how-to tutorials? Check to see if there are already other pieces which are on the same subject as your idea, i.e. will your piece add to the conversation already started by those articles? If you can show that you are aware of existing content on a particular subject, and explain how you will reference it or add to that information, the editor will know you have done some research.

Research more widely; are there already good pieces on the subject that an editor will consider your piece to be a repeat of? There is always space for a new take on an issue, but in general, publications want fresh material. You should be ready to explain how your piece will reference this earlier work and build upon it, or introduce the subject to a new audience.

A good example from our own archives is the piece, “Replacing jQuery With Vue.js”. There are a lot of introductions to Vue.js, however, this piece was squarely aimed at the web developer who knows jQuery. It introduced the subject in a familiar way specifically for the target audience.

Find The Submission Guide

The next thing to do is to find the submission information on the site you want to write for. Most publications will have information about who to contact and what information to include. From my point of view, simply following that information and demonstrating you have done some research puts you pretty high up the queue to be taken seriously. At Smashing Magazine, we have a link to the guide to writing for us right there on the contact form. I’d estimate that only 20% of people read and follow those instructions.

The link to our submission guide on our Contact Us page.

When you submit your idea, it is up to you to sell it to the publication. Why should I run with your idea over the many others that will show up today? Spending time over your submissions will make a huge difference in how many pieces you have accepted.

Different publications have different requirements. At Smashing Magazine, we ask you to send an outline first, along with some information about you so that we can understand your expertise in the subject matter. We’re very keen to feature new voices, and so we’ll accept pieces from writers who haven’t got a huge string of writing credentials.

The information we request helps us to decide if you are likely to be able to deliver a coherent piece. As our articles are technical in nature (often tutorials), I find that an outline is the best way to quickly see the shape of the proposal and the scope it will cover. A good outline will include the main headings or sections of the article, along with an explanation of what will be taught in that section.

For many other publications, a common request is for you to send a pitch for the article. This would typically be a couple of paragraphs explaining the direction your piece will take. Once again, check the submission guide for any specific details that publication is interested to see.

The Verge has an excellent submission guide which explains exactly what they want to see in a pitch:

"A good pitch contains a story, a narrative backbone. Pitches should clearly and concisely convey the story you plan to write and why it matters. The best pitches display promising pre-reporting and deep knowledge of the topic as well as a sense of the angle or insight you plan to pursue. If your story depends on access to a person or company, you should say whether you have obtained it already (and if not, what your prospects are). Pitches should also be written in the style you expect to write the story." — “How To Pitch The Verge,” The Verge

A List Apart explains what they will accept in their contribution page:

"... a rough draft, a partial draft, or a short pitch (a paragraph or two summarizing your argument and why it matters to our readers) paired with an outline. The more complete your submission is, the better feedback we can give you." — “Write For Us,” A List Apart

The Slate has a list of Do’s and Don’ts for pitching:

"Do distill your idea into a pitch, even if you have a full draft already written. If you happen to have a draft ready, feel free to attach it, but please make sure you still include a full pitch describing the piece in the body of the email." — “How To Pitch Slate,” The Slate

Including your pitch or outline in the body of the email is a common theme of pitch guidelines. Remember that your aim is to make it as easy as possible for the editor to think, “that looks interesting”.

Include A Short Biography

The editor doesn’t need your life story, however, a couple of sentences about you is helpful. This is especially useful if you are a newer writer who has subject matter expertise but fewer writing credentials. If you are proposing an article to me about moving a site from WordPress to Gatsby, and tell me that the article is based on your experience of doing this on a large site, that is more interesting to me than a more experienced writer who has just thought it would be a good topic to write about.

If you do have writing credits, a few relevant links are more helpful than a link to your entire portfolio.

When You Can’t Find A Submission Guide

Some publications will publish an email address or contact form for submissions, but have no obvious guide. In that case, assume that a short pitch as described above is appropriate. Include the pitch in the body of the email rather than an attachment, and make sure you include contact details in addition to your email address.

If you can’t find any information about submitting, then check to see if the publication is actually accepting external posts. Are all the articles written by staff? If unsure, then get in touch via a published contact method and ask if they accept pitches.

I’ve Already Written My Article, Why Should I Send An Outline Or Pitch?

We ask for an outline for a few reasons. Firstly, we’re a very small team. Each proposal is assessed by me, and I don’t have time in the day to read numerous 3000-word first draft proposals. In addition, we often have around 100 articles in the writing process at any one time. It’s quite likely that two authors will want to write on the same subject.

On receiving an outline, if it is going in a similar direction to something we already have in the pipeline, I can often spot something that would add to — rather than repeat — the other piece. We can then guide you towards that direction, and be able to accept the proposal where a completed piece may have been rejected as too similar.

If you are a new writer, the ability to structure an outline tells me a lot about your ability to deliver us something useful. We are going to spend time and energy working with you on your article, and I want to know it will be worthwhile for all of us.

If you are an experienced writer, the fact that you have read and worked with our guidelines tells me a lot about you as a professional. Are you going to be difficult for our editorial team to work with and refuse to make requested changes? Or are you keen to work with us to shape a piece that will be most useful and practical for the audience?

In The Verge submission guide included above, they ask you to “clearly and concisely” convey the story you plan to write. Your pitch shouldn’t be an article with bits removed or about the first two paragraphs. It’s literally a sales pitch for your proposed article; your job is to make the editor excited to read your full proposal! Some publications — in particular those that publish timely pieces on news topics — will ask you to attach your draft along with the pitch, however, you still need to get the editor to think it is worth opening that document.

Promoting Yourself Or Your Business

In many guides to self-promotion or bootstrapping the promotion of a startup, writing guest posts is something that will often be suggested. Be aware that the majority of publications are not going to publish an advert and pay you for the privilege.

Writing an article that refers to your product may be appropriate, as most of our expertise comes from doing the job that we do. It is worth being upfront when proposing a piece that would need to mention your product or the product of the company you work for. Explain how your idea will not be an advert for the company and that the product will only be mentioned in the context of the experience gained in your work.

Some publications will accept a trade of an article for some promotion. CSS-Tricks is one such publication, and describes what they are looking for as follows:

“The article is intended to promote something. In that case, no money changes hands. In this scenario, your pitch must be different from a sponsored post in that you aren’t just straight up pitching your product or service and that you’re writing a useful article about the web; it just so happens to be something that the promotion you’ll get from this article is valuable to you.” — “Guest Posting,” CSS-Tricks

Writing for a popular publication will give you a byline, i.e. your credit as an author. That will generally give you at least one link to your own site. Writing well-received articles can be a way to build up your reputation and even introduce people to your products and services, but if you try and slide an advert in as an article, you can be sure that editors are very well used to spotting that!

Pitching The Same Idea To Multiple Publications

For time-sensitive pieces, you might be keen to spread the net. In that case, you should make publications aware of submitting that you have submitted it elsewhere. Otherwise, it is generally good practice to wait for a response before offering the piece to another publication. The Slate writes,

"Do be mindful if you pitch your idea to multiple publications. We try to reply to everyone in a timely manner, typically within one to two days. As a general rule, and if the story isn’t too timely, it’s best to wait that amount of time before sharing the pitch with another publication. If you do decide to cast a wide net, it’s always helpful to let us know ahead of time so we can respond accordingly." — “How To Pitch Slate,” The Slate

If Your Pitch Is Rejected

You will have ideas rejected. Sometimes, the editor will let you know why, but most often you’ll get a quick no, thanks. Try not to take these to heart; there are many reasons why the piece might be rejected that have nothing to do with the article idea or the quality of your proposal.

The main reasons I reject pitches are as follows:

Obvious Spam This is the easy one. People wanting to publish a “guest post” on vague subjects, and people wanting “do-follow links”. We don’t tend to reply to these as they are essentially spam.

No Attempt At A Serious Outline I can’t tell anything about an idea from two sentences or three bullet points, and if the author can’t spend the time to write an outline, I don’t think I want to have a team member working with them.

Not A Good Topic For Us There are some outlines that I can’t ever see being a great fit for our readers.

An Attempt To Hide An Advert In this case, I’ll suggest that you talk to our advertising team!

Difficult To Work With Last but not least, authors who have behaved so badly during the pitch process that I can’t bring myself to inflict them on anyone else. Don’t be that person!

If I have a decent outline on a relevant subject in front of me, then one of two things are going to happen: I’ll accept the outline and get the author into the writing process or I’ll reply to the author because there is some reason why we can’t accept the outline as it is. That will usually be because the target audience or tone is wrong, or we already have a very similar piece in development.

Quite often in these scenarios, I will suggest changes or a different approach. Many of those initial soft rejections become an accepted idea, or the author comes back with a different idea that does indeed work.

Ultimately, those of us who need to fill a publication with content really want you to bring us good ideas. To open my inbox and find interesting pitches for Smashing is a genuine highlight of my day. So please do write for us.

Things To Do

Research the publication, and the type of articles they publish;

Read their submissions guide, and follow it;

Be upfront if you have sent the pitch to other publications;

Include a couple of sentences about you, and why you are the person to write the article. Link to some other relevant writing if you have it;

Be polite and friendly, but concise.

Things To Avoid

Sending a complete draft along with the words, “How do I publish this on your site?”;

Sending things in a format other than suggested in the submissions guide;

Pitching a piece that is already published somewhere else;

Pitching a hidden advert for your product or services;

Following up aggressively, or sending the pitch to multiple editors, Facebook messenger, and Twitter, in an attempt to get noticed. We publish a pitch contact, because we want pitches. It might take a day or two to follow up though!

More Pitching Tips

“How To Write A Pitch That Gets You Published,” Format with tips for creatives pitching to magazines

“How To Successfully Pitch The New York Times (Or, Well, Anyone Else),” Tim Herrera, NiemanLab some excellent tips on writing good pitches

(il)

0 notes

Text

[ Part 01 VueJs Introduction ] Complete Vue.JS Tutorial Series for beginners in اردو / हिंदी

[ad_1] Hello Friends,

Welcome to Part 01 VueJs Introduction by Perfect Web Solutions, This is a Complete Vue.JS Tutorial Series for Beginners in Urdu and Hindi Language 2018.

Vue (pronounced /vjuː/, like view) is a progressive framework for building user interfaces. Unlike other monolithic frameworks, Vue is designed from the ground up to be incrementally adoptable. The core library is focused on…

View On WordPress

#beginners#complete#Introduction#javascript#javascript functions#learn vue.js#learn vuejs#Part#perfect web solutions#series#tutorial#vue js#vue js 2#vue js 2 tutorial#vue js 2018#vue js 2019#vue js in hindi 2017#vue js in urdu#vue js tutorial#vue js tutorial 2018#vue js tutorial for beginners#vue js tutorial hindi#vue js tutorial in urdu 2018#vue js tutorial urdu#vue.js components#vuejs#vuejs components#vuejs hindi#VueJs Introduction#vuejs todo

1 note

·

View note

Photo

10+ Best Vue.js Courses & Tutorials in 2019! Everybody talks about Vue.js, why is it so popular? Yes, I know. You often ask this question.

0 notes

Link

JavaScript Essentials 2019 Mini Course ##100%FREEUdemyDiscountCoupons ##FreeOnlineTraining #Essentials #JavaScript #MINI JavaScript Essentials 2019 Mini Course This is the perfect introduction course to JavaScript to learn JavaScript from scratch and become an intermediate frontend developer. In this course you will learn all the JavaScript fundamentals that will launch you into a career as a web developer. JavaScript Essentials was designed to give your transferable programming skills so you can learn Node.js, Vue.js, React.js and even Python/PHP, so you can become a full stack developer. We'll go over variables, query selectors, functions and much much more! View the list of lessons below. 👉 Activate Udemy Coupon 👈 Free Tutorials Udemy Review Real Discount Udemy Free Courses Udemy Coupon Udemy Francais Coupon Udemy gratuit Coursera and Edx ELearningFree Course Free Online Training Udemy Udemy Free Coupons Udemy Free Discount Coupons Udemy Online Course Udemy Online Training 100% FREE Udemy Discount Coupons https://www.couponudemy.com/blog/javascript-essentials-2019-mini-course/

0 notes

Photo

The Vue Tutorial (2019) - Learn Vue.js from scratch ☞ https://school.geekwall.in/p/H126-j4wE/the-vue-tutorial-2019-learn-vue-js-from-scratch #vuejs #javascript

0 notes

Photo

The Vue Tutorial (2019) - Learn Vue.js from scratch ☞ https://school.geekwall.in/p/H126-j4wE/the-vue-tutorial-2019-learn-vue-js-from-scratch #vuejs #javascript

0 notes

Text

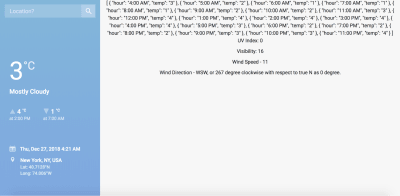

Using Vue.js To Create An Interactive Weather Dashboard With APIs

Using Vue.js To Create An Interactive Weather Dashboard With APIs

Souvik Sarkar

2019-02-01T13:00:18+01:002019-02-01T11:48:39+00:00

(This is a sponsored article.) In this tutorial, you will build a simple weather dashboard from scratch. It will be a client-end application that is neither a “Hello World” example, nor too intimidating in its size and complexity.

The entire project will be developed using tools from the Node.js + npm ecosystem. In particular, we will be heavily relying on the Dark Sky API for the data, Vue.js for all the heavy lifting, and FusionCharts for data visualization.

Prerequisites

We expect that you are familiar with the following:

HTML5 and CSS3 (we will also be using the basic features provided by Bootstrap;

JavaScript (especially ES6 way of using the language);

Node.js and npm (the basics of the environment and package management is just fine).

Apart from the ones mentioned above, it would be great if you have familiarity with Vue.js, or any other similar JavaScript framework. We don’t expect you to know about FusionCharts — it’s so easy to use that you will learn it on the fly!

Expected Learnings

Your key learnings from this project will be:

How to plan about implementing a good dashboard

How to develop applications with Vue.js

How to create data-driven applications

How to visualize data using FusionCharts

In particular, each of the sections take you a step closer to the learning goals:

An Introduction To The Weather Dashboard This chapter gives you an overview of different aspects of the undertaking.

Create The Project In this section, you learn about creating a project from scratch using the Vue command-line tool.

Customize The Default Project Structure The default project scaffolding that you get in the previous section is not enough; here you learn the additional stuff needed for the project from a structural point of view.

Data Acquisition And Processing This section is the meat of the project; all the critical code for acquiring and processing data from the API is showcased here. Expect to spend maximum time on this section.

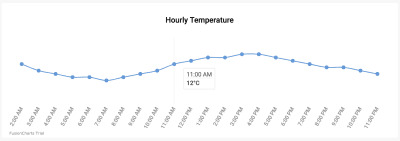

Data Visualization With FusionCharts Once we have all the data and other moving parts of the project stabilized, this section is dedicated towards visualizing the data using FusionCharts and a bit of CSS.

1. The Dashboard Workflow

Before we dive into the implementation, it is important to be clear about our plan. We break our plan into four distinct aspects:

Requirements

What are our requirements for this project? In other words, what are the things that we want to showcase through our Weather Dashboard? Keeping in mind that our intended audience are probably mere mortals with simple tastes, we would like to show them the following:

Details of the location for which they want to see the weather, along with some primary information about the weather. Since there are no stringent requirements, we will figure out the boring details later. However, at this stage, it is important to note that we will have to provide the audience a search box, so that they can provide input for the location of their interest.

Graphical information about the weather of their location of interest, such as:

Temperature variation for the day of query

Highlights of today’s weather:

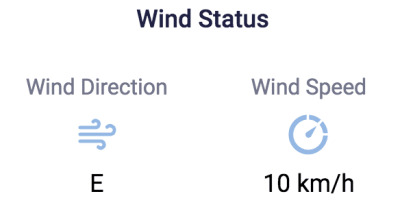

Wind Speed and Direction

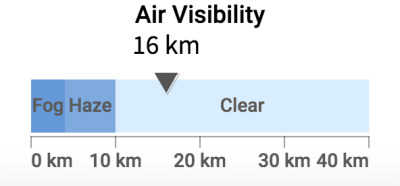

Visibility

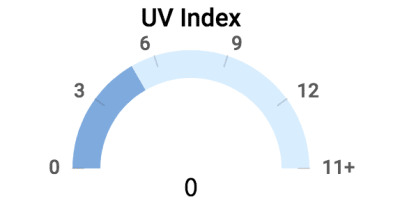

UV Index

Note: The data obtained from the API provides information regarding many other aspects of the weather. We choose not to use all of them for the sake of keeping the code to a minimum.

Structure

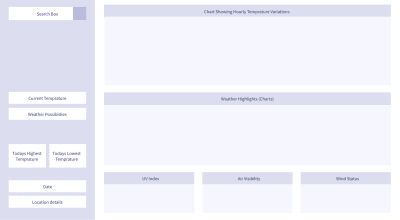

Based on the requirements, we can structure our dashboard as shown below:

(Large preview)

Data

Our dashboard is as good as the data we get, because there will be no pretty visualizations without proper data. There are plenty of public APIs that provide weather data — some of them are free, and some are not. For our project, we will collect data from the Dark Sky API. However, we will not be able to poll the API endpoint from the client end directly. Don’t worry, we have a workaround that will be revealed just at the right time! Once we get the data for the searched location, we will do some data processing and formatting — you know, the type of technicalities that helps us pay the bills.

Visualization

Once we get clean and formatted data, we plug it in to FusionCharts. There are very few JavaScript libraries in the world as capable as FusionCharts. Out of the vast number of offerings from FusionCharts, we will use only a few — all written in JavaScript, but works seamlessly when integrated with the Vue wrapper for FusionCharts.

Armed with the bigger picture, let’s get our hands dirty — it’s time to make things concrete! In the next section, you will create the basic Vue project, on top of which we will build further.

2. Creating The Project

To create the project, execute the following steps:

Install Node.js + npm (If you have Node.js installed on your computer, skip this step.) Node.js comes with npm bundled with it, so you don’t need to install npm separately. Depending on the operating system, download and install Node.js according to the instructions given here. Once installed, it’s probably a good idea to verify if the software is working correctly, and what are their versions. To test that, open the command-line/terminal and execute the following commands:

node --version npm --version

Install packages with npm Once you have npm up and running, execute the following command to install the basic packages necessary for our project.

npm install -g vue@2 vue-cli@2

Initialize project scaffolding with vue-cli Assuming that the previous step has gone all well, the next step is to use the vue-cli — a command-line tool from Vue.js, to initialize the project. To do that, execute the following:

Initialize the scaffolding with webpack-simple template.

vue init webpack-simple vue_weather_dashboard

You will be asked a bunch of questions — accepting the defaults for all but the last question will be good enough for this project; answer N for the last one.

(Large preview)

Keep in mind that although webpack-simple is excellent for quick prototyping and light application like ours, it is not particularly suited for serious applications or production deployment. If you want to use any other template (although we would advise against it if you are a newbie), or would like to name your project something else, the syntax is:

vue init [template-name] [project-name]

Navigate to the directory created by vue-cli for the project.

cd vue_weather_dashboard

Install all the packages mentioned in the package.json, which has been created by the vue-cli tool for the webpack-simple template.

npm install

Start the development server and see your default Vue project working in the browser!

npm run dev

If you are new to Vue.js, take a moment to savor your latest achievement — you have created a small Vue application and its running at localhost:8080!

(Large preview)

Brief Explanation Of The Default Project Structure

It’s time to take a look at the structure inside the directory vue_weather_dashboard, so that you have an understanding of the basics before we start modifying it.

The structure looks something like this:

vue_weather_dashboard |--- README.md |--- node_modules/ | |--- ... | |--- ... | |--- [many npm packages we installed] | |--- ... | |--- ... |--- package.json |--- package-lock.json |--- webpack.config.js |--- index.html |--- src | |--- App.vue | |--- assets | | |--- logo.png | |--- main.js

Although it might be tempting to skip getting familiar with the default files and directories, if you are new to Vue, we strongly recommend at least taking a look at the contents of the files. It can be a good educational session and trigger questions that you should pursue on your own, especially the following files:

package.json, and just a glance at its cousin package-lock.json

webpack.config.js

index.html

src/main.js

src/App.vue

A brief explanation of each of the files and directories shown in the tree diagram are given below:

README.md No prize for guessing — it is primarily for humans to read and understand the steps necessary for creating the project scaffolding.

node_modules/ This is the directory where npm downloads the packages necessary for kickstarting the project. The information about the packages necessary are available in the package.json file.

package.json This file is created by the vue-cli tool based on the requirements of the webpack-simple template, and contains information about the npm packages (including with their versions and other details) that must be installed. Take a hard look at the content of this file — this is where you should visit and perhaps edit to add/delete packages necessary for the project, and then run npm install. Read more about package.json here.

package-lock.json This file is created by npm itself, and is primarily meant for keeping a log of things that npm downloaded and installed.

webpack.config.js This a JavaScript file that contains the configuration of webpack — a tool that bundles different aspects of our project together (code, static assets, configuration, environments, mode of use, etc.), and minifies before serving it to the user. The benefit is that all things are tied together automatically, and the user experience enhances greatly because of the improvement in the application’s performance (pages are served quickly and loads faster on the browser). As you might encounter later, this is the file that needs to be inspected when something in the build system does not works the way it is intended to be. Also, when you want to deploy the application, this is one of the key files that needs to be edited (read more here).

index.html This HTML file serves as the matrix (or you can say, template) where data and code is to be embedded dynamically (that’s what Vue primarily does), and then served to the user.

src/main.js This JavaScript file contains code that primarily manages top/project level dependencies, and defines the topmost level Vue component. In short, it orchestrates the JavaScript for the entire project, and serves as the entry point of the application. Edit this file when you need to declare project-wide dependencies on certain node modules, or you want something to be changed about the topmost Vue component in the project.

src/App.vue In the previous point, when we were talking about the “topmost Vue component”, we were essentially talking about this file. Each .vue file in the project is a component, and components are hierarchically related. At the start, we have only one .vue file, i.e. App.vue, as our only component. But shortly we will add more components to our project (primarily following the structure of the dashboard), and link them in accordance to our desired hierarchy, with App.vue being the ancestor of all. These .vue files will contain code in a format that Vue wants us to write. Don’t worry, they are JavaScript code written maintaining a structure that can keep us sane and organized. You have been warned — by the end of this project, if you are new to Vue, you may get addicted to the template — script — style way of organizing code!

Now that we have created the foundation, it’s time to:

Modify the templates and tweak the configuration files a bit, so that the project behaves just the way we want.

Create new .vue files, and implement the dashboard structure with Vue code.

We will learn them in the next section, which is going to be a bit long and demands some attention. If you need caffeine or water, or want to discharge — now is the time!

3. Customizing The Default Project Structure

It’s time to tinker with the foundation that the scaffolded project has given us. Before you start, ensure that the development server provided by webpack is running. The advantage of running this server continuously is that any changes you make in the source code — one you save it and refresh the web page — it gets immediately reflected on the browser.

If you want to start the development server, just execute the following command from the terminal (assuming your current directory is the project directory):

npm run dev

In the following sections, we will modify some of the existing files, and add some new files. It will be followed by brief explanations of the content of those files, so that you have an idea of what those changes are meant to do.

Modify Existing Files

index.html

Our application is literally a single page application, because there is just one webpage that gets displayed on the browser. We will talk about this later, but first let’s just make our first change — altering the text within the <title> tag.

With this small revision, the HTML file looks like the following:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <!-- Modify the text of the title tag below --> <title>Vue Weather Dashboard</title> </head> <body> <div id="app"></div> <script src="/dist/build.js"></script> </body> </html>

Take a moment to refresh the webpage at localhost:8080, and see the change reflected on the title bar of the tab on the browser — it should say “Vue Weather Dashboard”. However, this was just to demonstrate you the process of making changes and verifying if it’s working. We have more things to do!

This simple HTML page lacks many things that we want in our project, especially the following:

Some meta information

CDN links to Bootstrap (CSS framework)

link to custom stylesheet (yet to be added in the project)

Pointers to the Google Maps Geolocation API from <script> tag

After adding those things, the final index.html has the following content:

<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html;charset=utf-8" /> <meta http-equiv="X-UA-Compatible" content="IE=edge"> <meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1, shrink-to-fit=no"> <link rel="stylesheet" href="//maxcdn.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/4.0.0/css/bootstrap.min.css"> <link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="src/css/style.css"> <title>Weather Dashboard</title> <script src="https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/js?key=AIzaSyC-lCjpg1xbw-nsCc11Si8Ldg2LKYizqI4&libraries=places"></script> </head> <body> <div id="app"></div> <script src="/dist/build.js"></script> </body> </html>

Save the file, and refresh the webpage. You might have noticed a slight bump while the page was getting loaded — it is primarily due to the fact that the page style is now being controlled by Bootstrap, and the style elements like fonts, spacing, etc. are different from the default we had earlier (if you are not sure, roll back to the default and see the difference).

(Large preview)

Note: One important thing before we move on — the URL for the Google Maps API contains a key which is a property of FusionCharts. For now, you can use this key to build the project, as we don’t want you to get bogged down by these type of minute details (which can be distractions while you are new). However, we strongly urge you to generate and use your own Google Maps API key once you have made some progress and feel comfortable to pay attention to these tiny details.

package.json

At the time of writing this, we used certain versions of the npm packages for our project, and we know for sure that those things work together. However, by the time you are executing the project, it is very much possible that the latest stable versions of the packages that npm downloads for you are not the same as we used, and this might break the code (or do things that are beyond our control). Thus, it is very important to have the exact same package.json file that was used to build this project, so that our code/explanations and the results you get are consistent.

The content of the package.json file should be:

{ "name": "vue_weather_dashboard", "description": "A Vue.js project", "version": "1.0.0", "author": "FusionCharts", "license": "MIT", "private": true, "scripts": { "dev": "cross-env NODE_ENV=development webpack-dev-server --open --hot", "build": "cross-env NODE_ENV=production webpack --progress --hide-modules" }, "dependencies": { "axios": "^0.18.0", "babel": "^6.23.0", "babel-cli": "^6.26.0", "babel-polyfill": "^6.26.0", "fusioncharts": "^3.13.3", "moment": "^2.22.2", "moment-timezone": "^0.5.21", "vue": "^2.5.11", "vue-fusioncharts": "^2.0.4" }, "browserslist": [ "> 1%", "last 2 versions", "not ie

We encourage you to go through the new package.json, and figure out what are functions of different objects in the json. You may prefer changing the value of the “author” key to your name. Also, the packages mentioned in the dependencies will reveal themselves at the right time in the code. For the time being, it’s sufficient to know that:

babel-related packages are for properly handling the ES6 style code by the browser;

axios deals with Promise-based HTTP requests;

moment and moment-timezone are for date/time manipulation;

fusioncharts and vue-fusioncharts are responsible for rendering charts:

vue, for obvious reasons.

webpack.config.js

As with package.json, we suggest you to maintain a webpack.config.js file that is consistent with the one we used for building the project. However, before making any changes, we recommend you to carefully compare the default code in the webpack.config.js, and the code we have provided below. You will notice quite a few differences — google them and have a basic idea of what they mean. Since explaining webpack configurations in depth is out of the scope of this article, you are on your own in this regard.

The customized webpack.config.js file is as follows:

var path = require('path') var webpack = require('webpack') module.exports = { entry: ['babel-polyfill', './src/main.js'], output: { path: path.resolve(__dirname, './dist'), publicPath: '/dist/', filename: 'build.js' }, module: { rules: [ { test: /\.css$/, use: [ 'vue-style-loader', 'css-loader' ], }, { test: /\.vue$/, loader: 'vue-loader', options: { loaders: { } // other vue-loader options go here } }, { test: /\.js$/, loader: 'babel-loader', exclude: /node_modules/ }, { test: /\.(png|jpg|gif|svg)$/, loader: 'file-loader', options: { name: '[name].[ext]?[hash]' } } ] }, resolve: { alias: { 'vue$': 'vue/dist/vue.esm.js' }, extensions: ['*', '.js', '.vue', '.json'] }, devServer: { historyApiFallback: true, noInfo: true, overlay: true, host: '0.0.0.0', port: 8080 }, performance: { hints: false }, devtool: '#eval-source-map' } if (process.env.NODE_ENV === 'production') { module.exports.devtool = '#source-map' // http://vue-loader.vuejs.org/en/workflow/production.html module.exports.plugins = (module.exports.plugins || []).concat([ new webpack.DefinePlugin({ 'process.env': { NODE_ENV: '"production"' } }), new webpack.optimize.UglifyJsPlugin({ sourceMap: true, compress: { warnings: false } }), new webpack.LoaderOptionsPlugin({ minimize: true }) ]) }

With changes made to the project’s webpack.config.js, it’s imperative that you stop the development server which is running (Ctrl + C), and restart it with the following command executed from the project’s directory after installing all the packages mentioned in the package.json file:

npm install npm run dev

With this, the ordeal of tweaking the configurations and ensuring that the right packages are in place ends. However, this also marks the journey of modifying and writing code, which is a bit long but also very rewarding!

src/main.js

This file is the key to top-level orchestration of the project — it is here that we define:

What the top level dependencies are (where to get the most important npm packages necessary);

How to resolve the dependencies, along with instructions to Vue on using plugins/wrappers, if any;

A Vue instance that manages the topmost component in the project: src/App.vue (the nodal .vue file).

In line with our goals for the src/main.js file, the code should be:

// Import the dependencies and necessary modules import Vue from 'vue'; import App from './App.vue'; import FusionCharts from 'fusioncharts'; import Charts from 'fusioncharts/fusioncharts.charts'; import Widgets from 'fusioncharts/fusioncharts.widgets'; import PowerCharts from 'fusioncharts/fusioncharts.powercharts'; import FusionTheme from 'fusioncharts/themes/fusioncharts.theme.fusion'; import VueFusionCharts from 'vue-fusioncharts'; // Resolve the dependencies Charts(FusionCharts); PowerCharts(FusionCharts); Widgets(FusionCharts); FusionTheme(FusionCharts); // Globally register the components for project-wide use Vue.use(VueFusionCharts, FusionCharts); // Instantiate the Vue instance that controls the application new Vue({ el: '#app', render: h => h(App) })

src/App.vue

This is one of the most important files in the entire project, and represents the topmost component in the hierarchy — the entire application itself, as a whole. For our project, this component will do all the heavy lifting, which we will explore later. For now, we want to get rid of the default boilerplate, and put something of our own.

If you are new to Vue’s way of organizing code, it would be better to get an idea of the general structure within the .vue files. The .vue files comprises of three sections:

Template This is where the HTML template for the page is defined. Apart from the static HTML, this section also contains Vue’s way of embedding dynamic content, using the double curly braces .

Script JavaScript rules this section, and is responsible for generating dynamic content that goes and sits within the HTML template at appropriate places. This section is primarily an object that is exported, and consists of:

Data This is a function itself, and usually it returns some desired data encapsulated within a nice data structure.

Methods An object that consists of one or more functions/methods, each of which usually manipulates data in some way or the other, and also controls the dynamic content of the HTML template.

Computed Much like the method object discussed above with one important distinction — while all the functions within the method object are executed whenever any one of them is called, the functions within the computed object behaves much more sensibly, and executes if and only if it has been called.

Style This section is for CSS styling that applies to the HTML of the page (written within template) — put the good old CSS here to make your pages beautiful!

Keeping the above paradigm in mind, let’s minimally customize the code in App.vue:

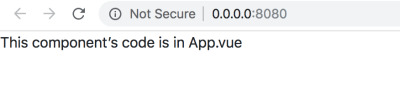

<template> <div id="app"> <p>This component’s code is in </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { data() { return { filename: 'App.vue' } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

Remember that the above code snippet is simply for testing out that App.vue is working with our own code in it. It will later go on through a lot of changes, but first save the file and refresh the page on the browser.

(Large preview)

At this point, it’s probably a good idea to get some help in tooling. Check out the Vue devtools for Chrome, and if you don’t have much problems in using Google Chrome as your default browser for development, install the tool and play around with it a bit. It will come in extremely handy for further development and debugging, when things becomes more complicated.

Additional Directories And Files

The next step would be to add additional files, so that the structure of our project becomes complete. We would add the following directories and files:

src/css/ — style.css

src/assets/ — calendar.svg — vlocation.svg — search.svg — winddirection.svg — windspeed.svg

src/components/ — Content.vue — Highlights.vue — TempVarChart.vue — UVIndex.vue — Visibility.vue — WindStatus.vue

Note: Save the hyperlinked .svg files in your project.

Create the directories and files mentioned above. The final project structure should like look (remember to delete folders and files from the default structure that are now unnecessary):

vue_weather_dashboard/ |--- README.md |--- node_modules/ | |--- ... | |--- ... | |--- [many npm packages we installed] | |--- ... | |--- ... |--- package.json |--- package-lock.json |--- webpack.config.js |--- index.html |--- src/ | |--- App.vue | |--- css/ | | |--- style.css | |--- assets/ | | |--- calendar.svg | | |--- location.svg | | |--- location.svg | | |--- winddirection.svg | | |--- windspeed.svg | |--- main.js | |--- components/ | | |--- Content.vue | | |--- Highlights.vue | | |--- TempVarChart.vue | | |--- UVIndex.vue | | |--- Visibility.vue | | |--- WindStatus.vue

There might be some other files, like .babelrc, .gitignore, .editorconfig, etc. in the project’s root folder. You may ignore them safely for now.

In the following section, we will add minimal content to the newly added files, and test whether they are properly working.

src/css/style.css

Although it will not be of much use immediately, copy the following code to the file:

@import url("https://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Roboto:300,400,500"); :root { font-size: 62.5%; } body { font-family: Roboto; font-weight: 400; width: 100%; margin: 0; font-size: 1.6rem; } #sidebar { position: relative; display: flex; flex-direction: column; background-image: linear-gradient(-180deg, #80b6db 0%, #7da7e2 100%); } #search { text-align: center; height: 20vh; position: relative; } #location-input { height: 42px; width: 100%; opacity: 1; border: 0; border-radius: 2px; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.2); margin-top: 16px; padding-left: 16px; color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.8rem; line-height: 21px; } #location-input:focus { outline: none; } ::placeholder { color: #FFFFFF; opacity: 0.6; } #current-weather { color: #ffffff; font-size: 8rem; line-height: 106px; position: relative; } #current-weather>span { color: #ffffff; font-size: 3.6rem; line-height: 42px; vertical-align: super; opacity: 0.8; top: 15px; position: absolute; } #weather-desc { font-size: 2.0rem; color: #ffffff; font-weight: 500; line-height: 24px; } #possibility { color: #ffffff; font-size: 16px; font-weight: 500; line-height: 19px; } #max-detail, #min-detail { color: #ffffff; font-size: 2.0rem; font-weight: 500; line-height: 24px; } #max-detail>i, #min-detail>i { font-style: normal; height: 13.27px; width: 16.5px; opacity: 0.4; } #max-detail>span, #min-detail>span { color: #ffffff; font-family: Roboto; font-size: 1.2rem; line-height: 10px; vertical-align: super; } #max-summary, #min-summary { opacity: 0.9; color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.4rem; line-height: 16px; margin-top: 2px; opacity: 0.7; } #search-btn { position: absolute; right: 0; top: 16px; padding: 2px; z-index: 999; height: 42px; width: 45px; background-color: rgba(255, 255, 255, 0.2); border: none; } #dashboard-content { text-align: center; height: 100vh; } #date-desc, #location-desc { color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.6rem; font-weight: 500; line-height: 19px; margin-bottom: 15px; } #date-desc>img { top: -3px; position: relative; margin-right: 10px; } #location-desc>img { top: -3px; position: relative; margin-left: 5px; margin-right: 15px; } #location-detail { opacity: 0.7; color: #ffffff; font-size: 1.4rem; line-height: 20px; margin-left: 35px; } .centered { position: fixed; top: 45%; left: 50%; transform: translate(-50%, -50%); } .max-desc { width: 80px; float: left; margin-right: 28px; } .temp-max-min { margin-top: 40px } #dashboard-content { background-color: #F7F7F7; } .custom-card { background-color: #FFFFFF !important; border: 0 !important; margin-top: 16px !important; margin-bottom: 20px !important; } .custom-content-card { background-color: #FFFFFF !important; border: 0 !important; margin-top: 16px !important; margin-bottom: 0px !important; } .header-card { height: 50vh; } .content-card { height: 43vh; } .card-divider { margin-top: 0; } .content-header { color: #8786A4; font-size: 1.4rem; line-height: 16px; font-weight: 500; padding: 15px 10px 5px 15px; } .highlights-item { min-height: 37vh; max-height: 38vh; background-color: #FFFFFF; } .card-heading { color: rgb(33, 34, 68); font-size: 1.8rem; font-weight: 500; line-height: 21px; text-align: center; } .card-sub-heading { color: #73748C; font-size: 1.6rem; line-height: 19px; } .card-value { color: #000000; font-size: 1.8rem; line-height: 21px; } span text { font-weight: 500 !important; } hr { padding-top: 1.5px; padding-bottom: 1px; margin-bottom: 0; margin-top: 0; line-height: 0.5px; } @media only screen and (min-width: 768px) { #sidebar { height: 100vh; } #info { position: fixed; bottom: 50px; width: 100%; padding-left: 15px; } .wrapper-right { margin-top: 80px; } } @media only screen and (min-width:1440px) { #sidebar { width: 350px; max-width: 350px; flex: auto; } #dashboard-content { width: calc(100% — 350px); max-width: calc(100% — 350px); flex: auto; } }

src/assets/

In this directory, download and save the .svg files mentioned below:

calendar.svg

location.svg

search.svg

winddirection.svg

windspeed.svg

src/components/Content.vue

This is what we call a dumb component — a placeholder, that is there just to maintain the hierarchy, and essentially passes on data to its child components.

Remember that there is no technical bar for writing all our code in the App.vue file, but we take the approach of splitting up the code by nesting the components for two reasons:

To write clean code, which aids readability and maintainability;

To replicate the same structure that we will see on screen, i.e., the hierarchy.

Before we nest the component defined in Content.vue within the root component App.vue, let’s write some toy (but educational) code for Content.vue:

<template> <div> <p>This child components of Content.vue are:</p> <ul> <li v-for="child in childComponents"></li> </ul> </div> </template> <script> export default { data () { return { childComponents: ['TempVarChart.vue', 'Highlights.vue'] } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

In the code, carefully observe and understand the following:

Within the <script> tag (where we obviously write some JavaScript code), we define an object that is exported (made available to other files) by default. This object contains a function data(), that returns an array object called childComponents, with its elements being names of the component files that should be nested further.

Within the <template> tag (where we write some HTML template), the thing of interest is the <ul>.

Within the unordered list, each list item should be names of the intended child components, as defined in the array object childComponents. Moreover, the list should automatically extend till the last element of the array. Seems like we should write a for-loop, isn’t it? We do that by using the v-for directive provided by Vue.js. The v-for directive:

Acts as an attribute of the <li> tag, iterates through the array, renders the names of the child components where the iterator is mentioned within the brackets (where we write the text for the list items).

The code and the explanation above forms the basis of your subsequent understanding of how the script and the template are interrelated, and how we can use the directives provided by Vue.js.

We have learnt quite a lot, but even after all these, we have one thing left to learn about seamlessly connecting components in hierarchy — passing data down from the parent component to its children. For now, we need to learn how to pass some data from src/App.vue to src/components/Content.vue, so that we can use the same techniques for the rest of the component nesting in this project.

Data trickling down from the parent to the child components might sound simple, but the devil is in the details! As briefly explained below, there are multiple steps involved in making it work:

Defining and the data For now, we want some static data to play with — an object containing hard-coded values about different aspects of weather will just be fine! We create an object called weather_data and return it from the data() function of App.vue. The weather_data object is given in the snippet below:

weather_data: { location: "California", temperature: { current: "35 C", }, highlights: { uvindex: "3", windstatus: { speed: "20 km/h", direction: "N-E", }, visibility: "12 km", }, },

Passing the data from the parent To pass the data, we need a destination where we want to send the data! In this case, the destination is the Content.vue component, and the way to implement it is to:

Assign the weather_data object to a custom attribute of the <Content> tag

Bind the attribute with the data using the v-bind: directive provided by Vue.js, which makes the attribute value dynamic (responsive to changes made in the original data).

<Content v-bind:weather_data=“weather_data”></Content>

Defining and passing the data is handled at the source side of the handshake, which in our case is the App.vue file.

The code for the App.vue file, at its current status, is given below:

<template> <div id="app"> <p>This component’s code is in </p> <Content v-bind:weather_data="weather_data"></Content> </div> </template> <script> import Content from './components/Content.vue' export default { name: 'app', components: { 'Content': Content }, data () { return { filename: 'App.vue', weather_data: { location: "California", temperature: { current: "35 C", }, highlights: { uvindex: "3", windstatus: { speed: "20 km/h", direction: "N-E", }, visibility: "12 km", }, }, } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

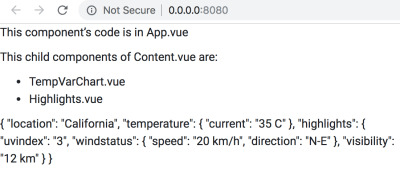

(Large preview)

With the data defined and passed from the source (parent component), it is now the child’s responsibility to receive the data and render it appropriately, as explained in the next two steps.

Receiving the data by the child The child component, in this case Content.vue, must receive the weather_data object send to it by the parent component App.vue. Vue.js provides a mechanism to do so — all you need is an array object called props, defined in the default object exported by Content.vue. Each element of the array props is a name of the data objects it wants to receive from its parent. For now, the only data object that it is supposed to receive is weather_data from App.vue. Thus, the props array looks like:

<template> // HTML template code here </template> <script> export default { props: ["weather_data"], data () { return { // data here } }, } </script> <style> // component specific CSS here </style>

Rendering the data in the page Now that we have ensured receiving the data, the last task we need to complete is to render the data. For this example, we will directly dump the received data on the web page, just to illustrate the technique. However, in real applications (like the one we are about to build), data normally goes through lots of processing, and only the relevant parts of it are displayed in ways that suits the purpose. For example, in this project we will eventually get raw data from the weather API, clean and format it, feed the data to the data structures necessary for the charts, and then visualize it. Anyway, to display the raw data dump, we will just use the brackets that Vue understands, as shown in the snippet below:

<template> <div id="pagecontent"> // other template code here </div> </template>

It’s now time to assimilate all the bits and pieces. The code for Content.vue — at its current status — is given below:

<template> <div id="pagecontent"> <p>This child components of Content.vue are:</p> <ul> <li v-for="child in childComponents"></li> </ul> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["weather_data"], data () { return { childComponents: ['TempVarChart.vue', 'Highlights.vue'] } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> #pagecontent { border: 1px solid black; padding: 2px; } </style>

(Large preview)

After making the changes discussed above, refresh the webpage on the browser and see how it looks. Take a moment to appreciate the complexity that Vue handles — if you modify the weather_data object in App.vue, it gets silently conveyed to Content.vue, and eventually to the browser displaying the webpage! Try by changing the value for the key location.

Although we have learned about props and data binding using static data, we will be using dynamic data collected using web APIs in the application, and will change the code accordingly.

Summary

Before we move on to the rest of the .vue files, let’s summarize what we have learnt while we wrote the code for App.vue and components/Content.vue:

The App.vue file is what we call the root component — the one that sits at the top of the component hierarchy. The rest of the .vue files represents components that are its direct child, grandchild, and so on.

The Content.vue file is a dummy component — its responsibility is to pass on the data to levels below and maintain the structural hierarchy, so that our code remains consistent with the philosophy “*what we see is what we implement*”.

The parent-child relationship of component does not happen out of thin air — you must register a component (either globally or locally, depending on the intended usage of the component), and then nest it using custom HTML tags (whose spellings are the exact same as that of the names with which the components has been registered).

Once registered and nested, data is passed on from parent to child components, and the flow is never reverse (bad things will happen if the project architecture allows backflow). The parent component is the relative source of the data, and it passes down relevant data to its children using the v-bind directive for the attributes of the custom HTML elements. The child receives the data intended for it using props, and then decides on its own what to do with the data.

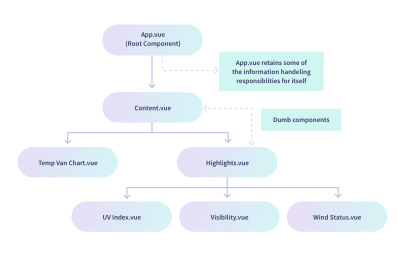

For the rest of the components, we will not indulge in detailed explanation — we will just write the code based on the learnings from the above summary. The code will be self-evident, and if you get confused about the hierarchy, refer to the diagram below:

(Large preview)

The diagram says that TempVarChart.vue and Highlights.vue are the direct child of Content.vue. Thus, it might be a good idea to prepare Content.vue for sending data to those components, which we do using the code below:

<template> <div id="pagecontent"> <p>This child components of Content.vue are:</p> <ul> <li v-for="child in childComponents"></li> </ul> <temp-var-chart :tempVar="tempVar"></temp-var-chart> <today-highlights :highlights="highlights"></today-highlights> </div> </template> <script> import TempVarChart from './TempVarChart.vue' import Highlights from './Highlights.vue' export default { props: ["weather_data"], components: { 'temp-var-chart': TempVarChart, 'today-highlights': Highlights }, data () { return { childComponents: ['TempVarChart.vue', 'Highlights.vue'], tempVar: this.weather_data.temperature, highlights: this.weather_data.highlights, } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

Once you save this code, you will get errors — don’t worry, it is expected. It will be fixed once you have the rest of the component files ready. If it bothers you not to be able to see the output, comment out the lines containing the custom element tags <temp-var-chart> and <today-highlights>.

For this section, this is the final code of Content.vue. For the rest of this section, we will reference to this code, and not the previous ones that we wrote for learning.

src/components/TempVarChart.vue

With its parent component Content.vue passing on the data, TempVarChart.vue must be set up to receive and render the data, as shown in the code below:

<template> <div id="tempvarchart"> <p>Temperature Information:</p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["tempVar"], data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

src/components/Highlights.vue

This component will also receive data from App.vue — its parent component. After that, it should be linked with its child components, and relevant data should be passed on to them.

Let’s first see the code for receiving data from the parent:

<template> <div id="highlights"> <p>Weather Highlights:</p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

At this point, the web page looks like the image below:

(Large preview)

Now we need to modify the code of Highlights.vue to register and nest its child components, followed by passing the data to children. The code for it is as follows:

<template> <div id="highlights"> <p>Weather Highlights:</p> <uv-index :highlights="highlights"></uv-index> <visibility :highlights="highlights"></visibility> <wind-status :highlights="highlights"></wind-status> </div> </template> <script> import UVIndex from './UVIndex.vue'; import Visibility from './Visibility.vue'; import WindStatus from './WindStatus.vue'; export default { props: ["highlights"], components: { 'uv-index': UVIndex, 'visibility': Visibility, 'wind-status': WindStatus, }, data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

Once you save the code and see the web page, you are expected to see errors in the Developer Console tool provided by the browser; they appear because although Highlights.vue is sending data, nobody is receiving them. We are yet to write the code for the children of Highlights.vue.

Observe that we have not done much of the data processing, i.e, we have not extracted the individual factors of weather data that goes under the Highlights section of the dashboard. We could have done that in the data() function, but we preferred to keep Highlights.vue a dumb component that just passes on the entire data dump it receives to each of the children, who then own their own extracts what is necessary for them. However, we encourage you to try out extracting data in the Highlights.vue, and send relevant data down to each child component — it’s a good practice exercise nonetheless!

src/components/UVIndex.vue

The code for this component receives the data dump of highlights from Highlights.vue, extracts the data for UV Index, and renders it on the page.

<template> <div id="uvindex"> <p>UV Index: </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { uvindex: this.highlights.uvindex } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

src/components/Visibility.vue

The code for this component receives the data dump of highlights from Highlights.vue, extracts the data for Visibility, and renders it on the page.

<template> <div id="visibility"> <p>Visibility: </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { visibility: this.highlights.visibility, } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

src/components/WindStatus.vue

The code for this component receives the data dump of highlights from Highlights.vue, extracts the data for Wind Status (speed and direction), and renders it on the page.

<template> <div id="windstatus"> <p>Wind Status:</p> <p>Speed — ; Direction — </p> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["highlights"], data () { return { speed: this.highlights.windstatus.speed, direction: this.highlights.windstatus.direction } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

After adding the code for all the components, take a look at the web page on the browser.

(Large preview)

Not to dishearten, but all these toiling was just to link the components in hierarchy, and test out whether data flow is happening between them or not! In the next section, we will throw away most of the code we have written so far, and add a lot more pertaining to the actual project. However, we will certainly retain the structure and nesting of the components; the learnings from this section will allow us to build a decent dashboard with Vue.js.

4. Data Acquisition And Processing

Remember the weather_data object in App.vue? It had some hard-coded data that we used to test whether all the components are working correctly, and also to help you learn some basic aspects of Vue application without getting bogged down in the details of real-world data. However, it’s now time that we shed our shell, and step out into the real world, where data from the API will dominate most of our code.

Preparing Child Components To Receive And Process Real Data

In this section, you will get code dump for all the components except App.vue. The code will handle receiving real data from App.vue (unlike the code we wrote in the previous section to receive and render dummy data).

We strongly encourage to read the code of each component carefully, so that you form an idea of what data each of those components are expecting, and will eventually use in visualization.

Some of the code, and the overall structure, will be similar to the ones you have seen in the previous structure — so you will not face something drastically different. However, the devil is in the details! So examine the code carefully, and when you have understood them reasonably well, copy the code to the respective component files in your project.

Note: All the components in this section are in the src/components/ directory. So each time, the path will not be mentioned — only the .vue file name will be mentioned to identify the component.

Content.vue

<template> <div style="position: relative;"> <temp-var-chart :tempVar="tempVar"></temp-var-chart> <today-highlights :highlights="highlights"></today-highlights> </div> </template> <script> import TempVarChart from './TempVarChart.vue'; import Highlights from './Highlights.vue'; export default { props: ['highlights', 'tempVar'], components: { 'temp-var-chart': TempVarChart, 'today-highlights': Highlights }, } </script>

The following changes have been made from the previous code:

In the <template>, text and data within has been removed, since we are now just receiving data and passing down to the children, with no rendering specific this component.

In the export default {}:

The props have been changed to match the data objects that will be send by the parent: App.vue. The reason for changing the props is that App.vue itself will display some of the data it acquires from the weather API and other online resources, based on the search query of the user, and pass on the rest of the data. In the dummy code we wrote earlier, App.vue was passing on the entire dummy data dump, without any discrimination, and the props of Content.vue was set up accordingly.

The data() function now returns nothing, as we are not doing any data manipulation in this component.

TempVarChart.vue

This component is supposed to receive detailed temperature projections for the rest of the current day, and eventually display them using FusionCharts. But for the time being, we will display them only as text on the webpage.

<template> <div> </div> </template> <script> export default { props: ["tempVar"], components: {}, data() { return { }; }, methods: { }, }; </script> <style> </style>

Highlights.vue

<template> <div> <uv-index :highlights="highlights"></uv-index> <visibility :highlights="highlights"></visibility> <wind-status :highlights="highlights"></wind-status> </div> </template> <script> import UVIndex from './UVIndex.vue'; import Visibility from './Visibility.vue'; import WindStatus from './WindStatus.vue'; export default { props: ["highlights"], components: { 'uv-index': UVIndex, 'visibility': Visibility, 'wind-status': WindStatus, }, data () { return { } }, methods: { }, computed: { }, } </script> <style> </style>

The changes made from the previous code are:

In the <template>, the text and the data within has been removed, because this is a dumb component, just like Content.vue, whose only job is to pass on the data to children while maintaining the structural hierarchy. Remember that dumb components like Highlights.vue and Content.vue exists to maintain the parity between the visual structure of the dashboard, and the code we write.

UVIndex.vue

The changes made to the previous code are as follows:

In the <template> and <style>, the div id has been changed to uvIndex, which is more readable.