#we cannot apply modern standards to this medieval fantasy story

Text

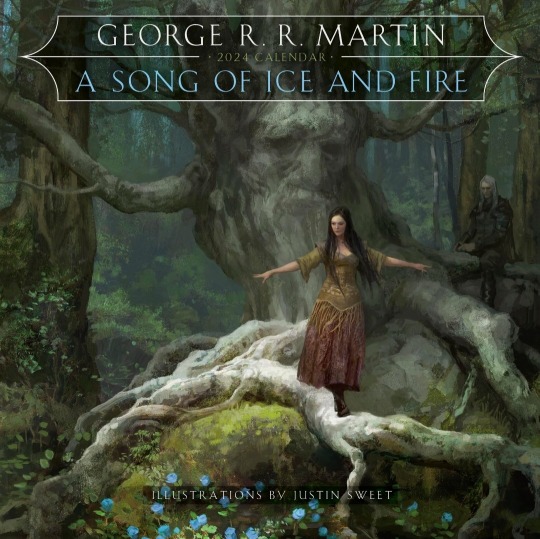

New art by Justin Sweet depicting Rhaegar and Lyanna! It's so pretty 😍

Lyanna doesn't look distressed or kidnapped to me, in fact, she seems to be enjoying herself walking on the giant tree roots in the woods with Rhaegar watching over her.

#justin sweet#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#lyanna stark#rhaegar targaryen#I'm so sick of the kidnapping claims#all of GRRM's protagonists are young#hes an old man#we cannot apply modern standards to this medieval fantasy story#pro daenerys targaryen#pro daenerys#just in case

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Last Unicorn - Blog #1

When you think of a book with unicorns, you probably think of picture books for little girls, and you likely wouldn’t expect it to mix with things like critical thinking or literary significance. However, if you’d prefer a more interesting text starring our favourite mythical equestrians, I’d like to introduce you to The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle. This book has sold more than five million copies worldwide since its original publication, and is often said to be one of the best fantasy novels written of all time. I’m here to show you how this book, or at least the first half of it, has proven its beauty and significance to me.

The Last Unicorn can at face value be identified as a fantasy novel, shown through the medieval setting, an inclusion of supernatural and magical forces, and the titular unicorn. But if we look a little harder at the text, we can begin to argue how it fits the genre and literary movement of magical realism. We can define it as such:

“Magical realism, or magic realism, is an approach to literature that weaves fantasy and myth into everyday life,” (ThoughtCo).

Typically, literary works under magical realism are given a setting which matches the one we live in, but I believe that the juxtaposition of magic and reality in Beagle’s work are a unique nod towards this literary movement. This genre ends up contributing heavily towards the setting, and the setting reinforces the presence of the genre, and talking about them separately would bring up lots of the same points.

While on the topic of setting, we are given a beautiful one in The Last Unicorn. We don’t have an exact period in history, but we can infer through the first half of the story that it’s based off of medieval Europe, especially through the language and vocabulary used by Beagle. We are given a magical version of this period in time where mythical creatures (see: unicorns) used to be a big thing, but have either gone extinct or unrecognized by society. Beagle builds the world in The Last Unicorn with a kind of middle ground between enchantment and disenchantment. For example, he includes wizards and unicorns, but the wizards are disgraced and the unicorns are thought to be nearly extinct. This is important because unicorns as a species are forgotten by the world, further driving home the themes of finding one's own identity and self-realization. The setting is a stark contrast from the usual one, which most frequently is a fantasy world at its peak, containing magic in every aspect. We can see a similarity between this world and our own, with the cynical nature of many characters as well as the disbelief in magic. The idea of a world between fantasy and reality can be connected to the idea of growing up, for example, having society tell us that beings we believed to be magical (Santa Claus, the Tooth Fairy, etc) aren’t real. We become so used to these figures, and when we are told that they’re merely fabrications, we have to cope with the reality while also questioning the legitimacy of what we already believe we know.

Through applying an LGBT* lens to this text, we can begin to extract concepts of significant depth and meaning in reference to this literary work of fiction. The character of the Unicorn is richly profound, especially when connected to themes and motifs of identity and the self, which is much of what LGBT theory concerns itself with. First off, we can see an immediate and obvious connection between the traditional concept of unicorns and the nature of femininity, but we can further connect their species to the lesbian continuum, especially separatist lesbianism. The Unicorn stays in her lilac wood alone, in seclusion from anyone who isn’t like her, and specifically hides from humanity, which she refers to as men. In the first chapter, the Unicorn hides from men out of discomfort and fear:

“One day it happened that two men with long bows rode through her forest, hunting for deer. The unicorn followed them, moving so warily that not even the horses knew she was near. The sight of men filled her with an old, slow, strange mixture of tenderness and terror,” (Beagle 3).

She is apprehensive of leaving her forest in fear of coming in contact with humanity, but is motivated to venture out in order to find other unicorns like her who share her identity. In her journey into the outside world, she encounters an ignorant heterocentric society which is completely unaware of unicorns, assuming they’re a myth and that the Unicorn is simply a white mare. This further develops her inner conflict, resulting in her becoming angry whenever her species is ignored and identified incorrectly as just a horse. Flipping the coin of homosexuality, we can analyze the character of Schmendrick the magician through seeing him as a coded gay man. On an immediate level, we can connect his character to the traditional American definition and stereotype of a closeted gay male. Schmendrick is generally seen as an inferior and bumbling wizard who tries and often fails to successfully perform magic, leading to a struggle with his identity of a magician. We can see Schmendrick struggling in his attempts in chapter 3 to free the unicorn from her cage, saying,

“‘I dreamed it differently, but I knew… You deserve the services of a great wizard,’ he said to the unicorn, ‘but I’m afraid you’ll have to be glad of the aid of a second-rate pickpocket,’” (Beagle 48).

He is shunned constantly by the societal norms in this world for his lack of skill in magic, which we can connect to internalized homophobia in his failure to live up to the standards set by the heteropatriarchy. His struggle to live up to the acceptable title of a great magician can be connected to the struggle held within compulsory heterosexuality, and he wishes to change his identity while the Unicorn embraces it. The Unicorn at first is opposed to allowing a man to come with her, leading for the magician to plead to her to allow him to assist her in the journey. Gay coded Schmendrick is seen as inferior to the lesbian coded Unicorn, even further relating their dynamic towards the imbalance and mirrored concepts of masculine/feminine gender identity addressed in queer* theory. In chapter 4, Beagle tackles the idea of identity at its crux with an interaction between the Unicorn and Schmendrick the magician,

“‘There it is’, the unicorn thought, feeling the first spidery touch of sorrow on the inside of her skin. That is how it will be to travel with a mortal, all the time. ‘No,’ she replied. ‘I cannot turn you into something you are not, no more than the witch could. I cannot turn you into a true magician.’” (Beagle 60).

Schmendrick wants to be a more acceptable version of what he is, and strives to perform in ways deemed by society to be fitting for a wizard, but falls short. This aspect of self hate is far too common in internal conflicts of LGBT individuals, and we can see the conflicts that face Schmendrick the magician as literary parallels to this experience.

In conclusion, The Last Unicorn has proven itself to be a lovely text so far, and I believe it will carry that through the next half of the story. For what it lacks in obvious real world parallels and connections to our modern world, it more than makes up for that in thematic elements, as well as interesting and complex characters, masterfully crafted environments, and most importantly, unicorns. Who wouldn’t take the time to read an epic tale about unicorns? Surely, nobody I would associate myself with.

*I personally will refer to lesbian, gay, and queer criticism as LGBT criticism for these specific reasons: First, I hold the right to find the term queer to still be incredibly discriminatory and oppressive. I believe that we are able to reclaim it, but myself and a vast majority of the community agree on it being a slur. Opinions may differ and this is definitely debatable, but as a transgender lesbian woman, I don’t think we’re at that point yet. Second, it’s just easier and shorter than saying “lesbian, gay, and queer” theory, as well as how that title leaves out transgender and bisexual, a very significant portion of the community which shouldn’t be left out, but I digress. Should write an essay on this sometime? Perhaps! Only time will tell.

2 notes

·

View notes