#white europeans and carried the colonial baggage of that with them

Text

not to be political but I've seen a lot of people saying that those who call Israel an apartheid don't know what they're talking about and um. As someone who has studied South African apartheid as well as grown up in a Jewish community. This claim has more merit than you think

#this post is brought to you by an article i read “debunking” the claim that israel is an apartheid and their “evidence”#included several policies that are the same if not more intense than apartheid era policies against black south africans#there are comparisons that hold weight here#although one thing i dont get and havent had explained to me yet. it looks to me as though both arabs and jews are indigenous to the region#in the way that both the hopewell culture and lenape people are indigenous to my state of pennsylvania#and thats a flimsy comparison i suppose since the hopewell culture (who lived here first chronologically) has died out#but anyway theres a case for indigeneity for both jews and arabs#its so silly to me that we dont consider both to be indigenous? yes many jews that came into israel in the early 20th century were#white europeans and carried the colonial baggage of that with them#but idk why its so hard to believe that an oppressed group can also be an oppressor?? like where's the intersectionality babes#anyway. the original point of this post was that maybe more of yall need to look into what south african apartheid was actually like#much like h*m*s leadership a lot of the ANC leadership was forced into exile and had to live and work outside of their country#(and this comparison is not perfect im aware. the tactics of the anc and h*m*s are totally different. however i think this comparison has#weight in that they are both one of the biggest names in opposition to the government. they do this in different ways at different levels o#intensity and violence. that is not to be ignored. but there are some comparisons that we can make and exile doesnt strike me as a bad one)#the bantustans in south africa were also constructed in a way that much like the west bank makes it highly difficult for an actual real#state to form#and the way that theyre set up invites puppet governments and corruption. this gives a major advantage to the apartheid state#id recommend reading Trevor Noah's Born A Crime if you havent#its a great introduction to what daily life in aparthid and after was like (its a memoir from about 1990-2005ish)#(apartheid was legally ended in 1994 but there are still remnants of it today and there were even more at the time of Born a Crime)#anyway these are my political thoughts of the day#edit: to my tangent about both groups being able to have some sort of claim to indigeneity. that in no way justifies any of the brutality#going on#i think its espeically cringe of israel to claim indigeneity and a sacred relationship with the land then create an environmental#catastrophe like they have in gaza. making the land unliveable is a bit of a perversion of the relationship you have with that land innit#in case it wasnt clear: ceasefire now and free palestine

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently, a copy of Alpines & Bog Plants by Reginald Farrer fell into my hands (thank you, antiquarian bookseller). At first I thought it would be botany but it is actually a mix of hobbyist naturalist & horticultural anecdotes.

It’s a first edition, published in 1908 -- remarkably well kept, pretty obvious spotting & foxing and one plate appears to be detaching from the spine. The book is remarkably poetic, but it would be free verse with binomial nomenclature, which I haven’t seen before,

The dedication is an excerpt from Hippolytus by Eurypides, roughly (according to my friend who studies classics):

“For you, lady, I bring this plaited garland I have made, gathered from an inviolate meadow,

a place where the shepherd does not dare to pasture his flocks (except rabbits), where the iron scythe has never come;”

In Hippolytus this is spoken to Artemis, but in this case the dedication is to Farrier’s mother which is heartwarming :)

Here I will note that the idea of “nature” as something undisturbed (ungrazed, unharvested) is central to the colonial conceptualisation of ecology and has contributed to the forceful removal of indigenous peoples from their land (and the subsequent loss of biodiversity, as humans are not separate from nature and we can play an important role in ecosystems)

Not calling Eurypides or this book inherently bad/colonial (more on the book & colonialism later) but this idea is def present in modern ecology and colonialism and important to highlight when present.

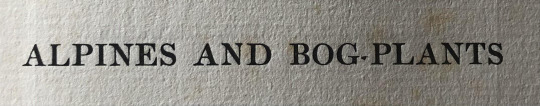

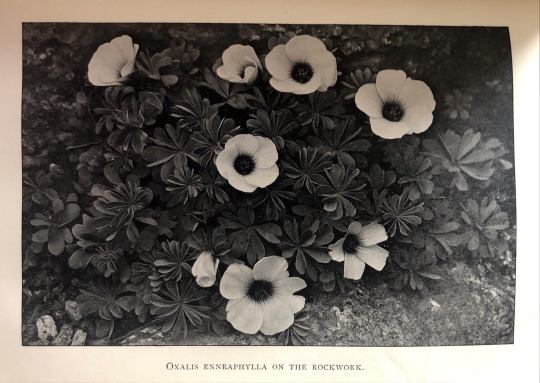

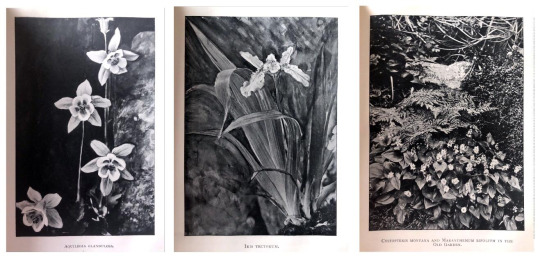

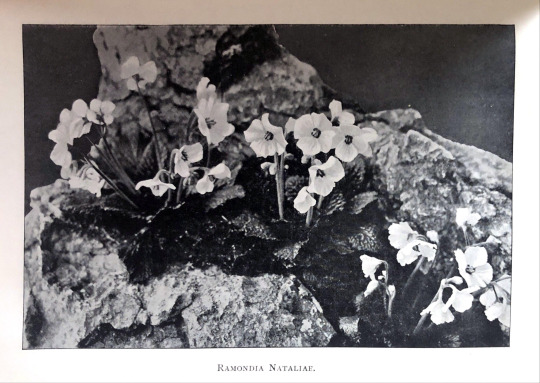

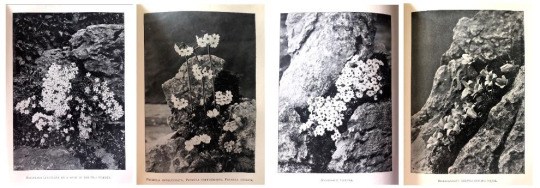

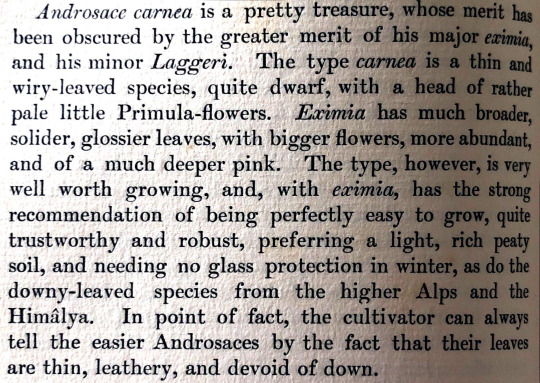

The book is full of black&white photographic plates which have held up really well for being over a century old. The plates themselves are beautiful:

The photographs were taken in Farrer’s own garden. Little snapshots of the past :)!!

The text content of the book is quite intriguing and not all good, definitely carries heavy cultural baggage as does modern Western biology in general. I will preface this by saying I have absolutely not battled my way through this book, but I have read sections. there is a definite 1900s-Englishman tone in all the ways that can mean. part of that is most certainly a degree of both xenophobia and orientalism. When venerating the beauty of the wilderness and of Japanese/Chinese garden design, there is obvious othering in the language used & Farrer is dismayed at the effects of cultural transmission (this is most notably in European gardens attempting to mimic the artistic style of east Asian gardens but using the “wrong” plants, usually European plants rather than importing non-native varieties that are more “authentic”). Farrer was deeply in love with Asian biota and was notable for collecting plants to bring back to Europe, and while I cannot speak on Farrer’s techniques specifically, such practices are deeply intwined in racism and colonialism. In many cases, economic systems & resulting hardships forced on other cultures by Europeans allowed them to exert control over certain groups, stripping them of agency and employing them to extirpate “uncooperative” groups. I haven’t found anything re:Farrer in this context but it is essential to place the entire book within this context!!

However the majority of the book is Farrer describing gardening as well as his travels to collect plants for propagation in the UK (notably he died while on one such plant-collection travel). Apparently (& corroborated by the preface) the plants he searched for were ones that would grow well in the UK w/o much care, to make having a cool garden more accessible regardless of income. so if a plant needed extensive care and things like hothouses, it was not his priority.

The way he describes plants is vaguely anthropomorphised in a generally appealing way, trying to make the reader appreciate the plant for things such as hardiness and robustness, which I suppose would align w/ the idea of making gardening easier. also in the sense that the robustness is tied in with beauty as well, as these features are of course not opposed to one another.

I may snoop through this book further to see anything else , we will see.

#library#antique books#antiquarian books#natural history#antique photography#history#books#old books#botany#gardening#horticulture#ecology#dark academia#miaow#osedax bookblog

65 notes

·

View notes

Link

...It’s this baggage that often complicates American Jews’ attempts to reflect on their relative privilege. In the current environment, many Ashkenazi Jews—i.e. those tracing their heritage through the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe—struggle to acknowledge their whiteness and role in broader systems of racism because anti-Semitism from the Left and Right distracts them, clouding their judgment, creating little space for them to exercise the vulnerability necessary for reflection.

Two recent examples illuminate the ways Jews are being squeezed by anti-Semitism from both sides of the political spectrum, complicating efforts at introspection. When Emily Bazelon wrote in The New York Times Magazine in June about the ways whites are finally noticing their whiteness and associated privilege, she was inundated with responses from right-wing Twitter trolls insisting that she was not white, but Jewish. The very same day, leftist activist Shaun King tweeted an article from the Israeli daily, Haaretz, about a Jewish group in Israel protesting an Arab family that had moved into a Jewish neighborhood. Rather than pointing out Jewish racism, he called the protesters “white supremacists” who only wanted “white Jews” in their neighborhood, ignoring the racial diversity within the accompanying picture as well as the Mizrahi (North African and the Middle Eastern Jewish) names of the Jewish organizers. In both of these cases, critics defined Jews for their own purposes.

Right-wing anti-Semites see Jews only as insidious ethnic people whose Ashkenazi members try to assimilate, muddling the purity of the white race. ...For some right-wing Americans, the existence of Israel is not just okay, but good, both because this is where the Jews “belong”—an anti-Semitic version of certain Zionist tropes—and also because Israel’s strident nationalism represents a type of ethnic purity white nationalists would like to see in Europe and the United States. Others are just straight-up Jew-haters who would be happy for Jews to go to the gas chambers.

Besides the obvious problem this brand of anti-Semitism presents for Jews, it also inspires a backlash of Jewish victimhood that undermines any attempt to reckon in a thoughtful and rigorous way with simultaneous Jewish privilege: Jews can’t be racist, the thinking goes, because they aren’t allowed to be white. Any time an Ashkenazi Jew begins to sort through their role in American white supremacy, the flurry of anti-Semitic noise in response causes many Jews to revert to victim mentality—a mentality which makes it very hard to think clearly about the full range of social justice. As the late Rabbi David Hartman wrote in his seminal 1982 essay, “Auschwitz or Sinai,” the person who sees the Holocaust in every anti-Semitic barb begins to think that “We need not take the moral criticism of the world seriously, because the uniqueness of our suffering places us above the moral judgment of an immoral world.”

Meanwhile, on the Left, Jews are seen as a religious minority within the superstructure of European Christian colonialism that has dominated the globe since Columbus. Yes, Jews have faced oppression, this narrative acknowledges, but they are ultimately a European byproduct: They are white people with a little flair—a belief system draped over the same racial material. When King tweeted about the “White Jews” who protested against the sale of a home in Afula (inside the Green line) to Palestinians with Israeli citizenship, he was following in this tradition, and in so doing erasing Jewish peoplehood. This was not Jewish racism against Arabs, in his view: It was white colonialist racism.

Jewish history, in fact, profoundly complicates the idea that all conflicts can be boiled down to modern Western European “white” Christian imperialism. But this trend on the left is increasingly strong. The term supersessionism has traditionally referred to the primacy of the New Testament for Christians, its teachings taking precedence over the Old Covenant between God and the Jews featured in the Old Testament. Recently, Bryan Cheyette, an English professor specializing in textual representations of Jewish identity, suggested that the insistence on a specifically postcolonial lens for evaluating oppression is a new kind of supersessionism: Kicked off by venerable postcolonial studies founder Edward Said, who believed Palestinians were the new Jews, it is now carried forward by progressives such as King, or Women’s March founders Tamika Mallory and Linda Sarsour, the latter of whom recently said Jews who feel unwelcome among today’s progressives “are going to have to come to terms with being uncomfortable,” because the Palestinian cause is too important—akin to South African apartheid. Implicitly, the story of the Palestinians and the story of African Americans are part of the same story of injustice, and the injustice against them has superseded Europe’s Holocaust. Cheyette instead suggested we move away from seeing these histories as exceptional: supersessionism “makes it impossible to find connections in the past and our most urgent present between different forms of dehumanization—Orientalism, anti-Semitism, and Islamophobia—and between shared forms of suffering (not least as refugees) alongside an often-violent agency.”

The 20th century demonstrated the tremendous capacity humans have to disregard and extinguish others’ lives, and the 21st century has yet to break that pattern. It is possible to recognize the persecution and violence, in modern memory, of Jews while recognizing the racism that exists within Jewish communities. It is also possible to recognize the deep and violent history of marginalization, oppression, and enslavement faced by African Americans and other people of color in America; and to see that both Israelis and Palestinians have been traumatized by wars, military occupation, and terrorist campaigns. The existence of each of these traumas does not delegitimize the others. In her intellectual history of intersectionality, gender studies professor Ange-Marie Hancock Alfaro argued that in making an intersectional shift, one begins to take subaltern communities as seriously as the mainstream. But doing so also means recognizing that “one is neither purely an oppressor nor purely oppressed”—a lesson both Jews and their critics have yet to internalize...

Read Joshua Ladon’s full piece at The New Republic.

(h/t @pointmerose)

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1.1, The Confession: Where are We? (Also, F___ the Queen)

The Third Policeman (hereinafter, “3P”) begins with the coldest of cold opens. The unnamed narrator confesses to the murder of a man named Mathers. In doing so, however, he deflects some guilt by implicating his friend, Divney. To understand this murder fully, as well as the book, as well as any book, it is important to understand the setting. In 3P, the setting is malleable and fantastical, paranormal and unreal, but grounded in some strange reality. Ironically, I think the fact that the setting is so fluid as largely detatched from reality makes understanding the setting more important to 3P than to other books that are set in modern day New York, say, but which take place in the dialogue or the plot. In 3P, on the contrary, the fantastical setting is a character itself. Yet it is easily relegated to the background. I think it is worth a few words. So where are we anyway?

The book is set in Ireland. Mathers, the name of the murder victim, is of English origin though. The relationship between England and Ireland is fraught with tension and resentment on the part of the Irish, and for good reason. England occupied Ireland for centuries. It arguably still does, in the form of Northern Ireland. It was there that Presbyterian Scottish settlers congregated, but English colonists spread over the whole of Ireland. So while most Anglo- or Scots-Irish are in Northern Ireland, in the late-1800s, there would have been Anglo-Irish all over the island. And though many may have identified as Irish, among the Gaelic underclass, they would likely have been easily identifiable, even after intermarriage, etc. So Mathers’s Englishness does not necessarily indicate the book is set in northern Ireland, it is some indication. (Note that the Presbyterian Scots-Irish suffered discrimination and maltreatment by the Anglican English too, in Ulster, they filled the same plantation-master-monopolist role that the Anglo-Irish did in the rest of the Emerald Isle. Whether Mathers is an Ulsterman or an run-of-the-mill Anglo-Irish colonist can’t be discerned from what is in the book.)

To step aside from the setting for a moment, the fact the Mathers is an English name may offer some insight into the author. Mathers is described as a rich old man who made his fortune in the “artificial manures" (a/k/a fertilizer) business. There is a clear undercurrent of resentment on behalf of the narrator against Mathers, which is likely held by many other locals too. Mathers lives in an old, isolated mansion in the countryside. His house is a physical manifestation of his wealth plopped down in the middle of a poor, desolate Gaelic Irish county. It is emblematic of England’s colonial history in Ireland. And Mathers himself is depicted as utterly alone except for his wealth and his mansion, a caricature of the wealth-obsessed Englishman accumulating his fortune by exploiting monopolistic connections to England and wider European commerce unavailable to the Irish living around him. It is implied that Mathers takes advantage of the Irish around him by selling these artificial manures, which give a huge advantage... to farmers who can afford them. The parallels to Monsanto and the like today are obvious and exacerbated by the fact that Mathers is just a middleman, a dealer if you will. Reference is made to a “Dutch ring” driving up the prices of the fertilizers by cornering the market in some fashion. So the locals have plenty of reason to hate or resent Mathers and his ilk.

O’Brien makes these Irish resentments painfully clear by having the brutal murder of the Englishman Mathers by two Irishmen, the narrator and his partner, Divney, not only be carried out completely casually and without reflection, but to act as the very plot motor and incipient act for 3P. Neither the narrator nor Divney ever come out and say, “We’re killing this English asshole because he deserves it because he and his kind have been fucking over us Irish for centuries.” But Mathers is killed purely for his money, and the killers’ motives are illustrative of the broader overtones of the killing: Divney wants money so he can get married to Pegeen Meers, and the narrator wants money so he can follow his dream of studying the enigmatic “academic” De Selby. Implicitly then, despite the fact that he inherits a working farm and tavern, it does not generate sufficient funds for either of them to do anything beyond continuing to till the land and serve ale to passersby--a subsistence living. They are, in essence, serfs. And just down the road is an Englishman with money. And without compunction or a criminal history, these otherwise mild-mannered Irishmen brutally beat him to death on the side of a road for his cash box. Moreover, no repentance is ever shown from the killing. The alternate dimension the narrator finds himself in his some kind of purgatory, presumably inflicted upon him for killing Mathers. But the narrator never apologizes or experiences any sense of remorse beyond a general guilt. And even that guilt seems to stem from the narrator not enjoying the various punishments inflicted upon him for the killing, not from a sense of true consciousness of wrong. (And, it should be said, the punishment are fairly light compared to the fire, brimstone, and gnashing teeth-type of hell that the narrator, an Irish Catholic, may have expected. Even if it is Purgatory, it seems to be sparing the rod as punishment for a premeditated, brutal, murder. Although, I suppose anything made to be consciously endured forever could be debilitatingly terrible from a subjective perspective. But even then, what is worse: Dealing with two idiotic policeman annoying and almost hanging you or eternity or getting your balls chewed off by pirhanas and being set on fire for eternity?) The nature of the heinous incipient crime, the casualness with which it was done, and the lack of any true remorse for it certainly indicates to me that the author, like many of his countrymen, had no love for the English. This would make sense, too, for O’Brian’s father was an Irish nationalist and civil servant who changed his family’s name from O’Nolan to the Gaelic original, O Nuallain. Presumably, in the O Nuallain household they did not celebrate St. George’s feast day and sing Rule Brittania, to put it lightly.

And why would he? The English are the definitive “white people” of the modern Western world. Their royal family are the whitest people you know or that you or anyone could ever know. And their historical record carries with it all the baggage that the word “imperialism” does today. Sure, the Belgians were more brutal in the Congo, the Dutch more craven in the West Indies, and the French more relentless in the end, but the English invented, at least in the popular imagination, colonialism, imperialism, white privilege, xenophobia, genocide. This is a cultural so full of that stuff that the colonized Ireland, a people today considered firmly a part of the white West, and treated them a poorly as they did any aboriginal tribe elsewhere in the world. The English were so “white” that the Irish weren’t even white to them.

This may have owed a lot to the religious schism between Protestant England and Catholic Ireland. But even if the Reformation had taken hold in Ireland, the English colonization may still have happened. There were also language differences and the very separation of the Irish Sea, a geographic interstate dividing gentrified England from the rough and tumble Hibernian ghetto on the other side. I am not an expert on Anglo-Irish historical relations, but the murder of Mathers, to me, waves a flag that this schism was on the author’s mind. And the fact that no one, the narrator included, seems to have any remorse or care for the murder of Mathers beyond the most prosaic procedural concerns of the policemen seems to back the idea that at least for the sake of a hyperbolic statement of Irish revenge, Mathers, the greedy English bastard, got what was coming to him, from the author’s perspective.

0 notes