#window film christchurch

Text

Professional Window Tinting Solutions in New Zealand | Tint-A-Window

Tint-A-Window offers professional window tinting solutions for homes throughout New Zealand. Enhance your privacy, reduce heat, and add style to your windows with our high-quality window film. Discover the benefits of our expert tinting services for a more comfortable and energy-efficient living space.

https://www.tintawindow.co.nz/

0 notes

Text

Window Tinting for Houses | Window Film in Christchurch | Tint a Window

Enhance your home with professional window tinting in Christchurch. Tint a Window offers top-quality window film solutions to provide privacy, reduce heat and glare, and protect against UV rays. Transform your living space while enjoying energy savings. Contact us today!

0 notes

Text

Experience the Ultimate Car Tint Style Meets Functionality

Elevate your driving experience with our top-notch car tinting services, designed to blend style, comfort, and functionality. Tint a car Our expert team provides precision car tinting that not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of your vehicle but also offers superior UV protection and glare reduction. Using only the finest materials, we ensure a flawless application that stands the test of time. Whether you’re looking to add a sleek look, improve privacy, or stay cooler on the road, our customised tinting solutions deliver exceptional results. Transform your car with our professional tinting services and enjoy the perfect combination of elegance and efficiency.

#commercial machines window tints#commercial window film canterbury#glare reduction films christchurch#glass film for windows christchurch

0 notes

Text

Forgot to post this earlier, went to the ‘Gothic Returns’ exhibition at the Auckland Art Gallery, and the ‘Medieval Manuscripts’ exhibition at the Auckland Library! Thanks Phoebe for going with me, this was such an awesome experience and I plan to go again soon- specifically to the gothic exhibition, it has etchings from Goya, beautiful!

Gothic Returns: Fuseli to Fomison

“This exhibition explores the persistent appeal of ‘the gothic’, a broad term that embraces some of the most darkly charismatic imagery ever produced. Incorporating all things febrile, esoteric, sombre and downright scary, this nebulous genre has its origins in the late 18th century British Romantic movement. First defined by thee medievalising novels of Horace Walpole (1717-1797) and the disturbingly sensual paintings of Swiss artist Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), it has since proven almost virus-like in its capacity to adapt and thrive across centuries. Whatever outward form it assumes, the gothic has also shown itself remarkably true to its essential character: ominous moods, unsettling themes and a melancholy engagement with the past.”

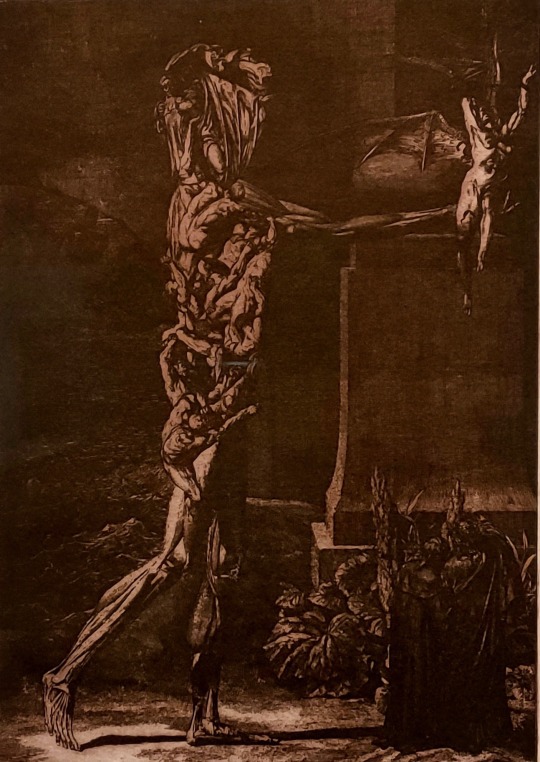

(Above left) Barry Cleavin, NZ, Menage a trois, etching and photo-engraving

“Inspired by predecessors such as Francisco Goya, Barry Cleavin utilises historical imagery to expose society’s dark, seedy underbelly. Both the lean, muscular figure standing in contrapposto pose and the work’s scenic, Neoclassical background are drawn from an 18th-century anatomical manual. Superimposing onto those images a harpy and a group of drowning figures culled from a 19th-century Romanticist depiction of a passage from Dante’s Inferno (1314), Cleavin implies that the Enlightenment project to understand and visualise the interior of the human body is not a disinterested science but a sick and twisted fantasy.”

(Above right) Henry Fuseli, The Serpent Tempting Eve (Satan’s First Address to Eve), 1802, oil on panel

“With its themes of confused morality and seductive evil, Paradise Lost (1667) by the revolutionary poet John Milton (1608-1674) had a profound influence on gothic art and fiction. Henry Fuseli painted numerous subjects from Milton’s poem, including this scene, in which a handsome Satan with the body of a serpent beguiles Eve into eating the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Eve then persuades Adam to do the same, leading to their expulsion from Paradise. The biblical story of Eve’s gullibility was often used as proof of women’s weaker minds and moral character and to explain their susceptibility to the dark arts of witchcraft.”

(Above) Ronnie van Hout, Psycho, 1999, house model

“The Victorian mansion, with its too-many rooms, has been imagined time and again as a living tomb for outcasts as it has declined into a forlorn relic of urban and social change. Identified by filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock as a structure that can literally breed insanity, few who have seen his 1960 horror film Psycho can enter such places without a feeling of stifled dread. In an overt nod to the cinematic classic, Christchurch-born Ronnie van Hout’s miniature sculpture of a Gothic villa reclaims the idea of the lonely Victorian mansion as a metaphor for the tormented artist’s mind. Through an upstairs window, the artist can be seen going knife-wielding mad in a tiny film, trapped in a mental and auditory landscape of B-grade horror movie tropes.”

(Above left) Edmund Sullivan, Persephone, 1906, lithograph

“A century after the birth of ‘the gothic’, an interest in its lurid themes and irrational energy resurfaced in the Symbolist movement and its related decorative style, known as Art Nouveau. The mythological story of Persephone was widely known through Ovid’s Metamorphosis. In it, Persephone, daughter of the goddess of the harvest, is abducted by her uncle Hades while smelling narcissi in the fields of Enna. Enjoyed for its thrillingly transgressive themes of illicit love and the Underworld, in this image British illustrator E J Sullivan exploits the erotic tension of two bodies merging into one continuous outline as Persephone embraces her lustful captor in a dreamlike ecstasy.”

(Above right) Henry Armstead, Satan Dismayed, circa 1852, bronze

“Henry Armstead’s sculptures captivated proponents of the Gothic Revival in mid-19th-century England. A depiction of a celebrated passage from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), this bronze shows a lithe, sensuously rendered Satan recoiling as the Son of God transforms the Devil’s benighted followers into slithering, serpentine demons. Milton’s Satan was the prototype of many hero-villains in Victorian Gothic novels. Proud, vain and driven by a perverted desire to corrupt and destroy others, he is here insidiously portrayed as a figure of alluring, angelic beauty.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Essential Packaging and Safety Solutions in New Zealand

In today’s fast-paced world, having reliable packaging and safety materials is crucial for businesses across various industries. In New Zealand, products such as plastic packaging film, plastic warning tape, and adhesive butyl pads are essential for ensuring the protection and integrity of goods. Whether you're based in Christchurch or anywhere else in the country, these materials play a vital role in everyday operations. This blog will explore the importance and applications of these products, highlighting their benefits and uses.

Plastic Packaging Film in New Zealand

Plastic packaging film in New Zealand is a versatile and widely used material in New Zealand. It serves multiple purposes, from protecting products during transit to preserving freshness and extending shelf life.

Versatility and Applications

Plastic packaging film is used across various industries, including food and beverage, pharmaceuticals, and retail. Its flexibility and durability make it ideal for wrapping and securing products of different shapes and sizes. In the food industry, this film helps maintain the freshness of perishable goods, ensuring they reach consumers in optimal condition.

Environmental Considerations

While plastic packaging film offers many benefits, it's essential to consider its environmental impact. Many manufacturers in New Zealand are now producing eco-friendly options, such as biodegradable and recyclable films. These alternatives help reduce waste and support sustainability efforts, making them an excellent choice for environmentally conscious businesses.

Plastic Warning Tape

Plastic warning tape is another crucial safety and packaging material. It is used to mark hazardous areas, provide instructions, and ensure safety in various environments.

Safety and Compliance

In industries such as construction, manufacturing, and logistics, safety is paramount. Plastic warning tape is an effective way to communicate warnings and instructions clearly. Its bright colors and bold prints make it easily noticeable, helping prevent accidents and ensuring compliance with safety regulations.

Versatile Uses

Plastic warning tape is not only for industrial use. It is also valuable in event management, crowd control, and even in residential settings. For example, it can be used to mark off areas during renovations or repairs, keeping people safe and informed.

Adhesive Butyl Pads in Christchurch

Adhesive butyl pads are a specialized product widely used in Christchurch and other parts of New Zealand. These pads offer superior sealing and adhesive properties, making them ideal for a variety of applications.

Superior Sealing Properties

Adhesive butyl pads are known for their excellent sealing capabilities. They are commonly used in the automotive, construction, and marine industries to seal joints, seams, and gaps. The butyl rubber material is highly resistant to water, air, and chemical ingress, ensuring a long-lasting seal.

Easy Application and Versatility

One of the significant advantages of adhesive butyl pads is their ease of application. They come in various sizes and shapes, making them suitable for different projects. Whether you need to seal a roof joint, a vehicle window, or a marine hatch, these pads provide a reliable solution.

Conclusion

In New Zealand, essential materials like plastic packaging film, plastic warning tape, and adhesive butyl pads play a crucial role in various industries. These products ensure the safety, protection, and integrity of goods and environments.

Plastic packaging film offers versatility and durability, making it a staple in the food, pharmaceutical, and retail industries. As businesses become more environmentally conscious, the availability of eco-friendly options helps reduce the environmental impact of packaging materials.

Plastic warning tape is indispensable for maintaining safety in industrial, event management, and residential settings. It’s clear and bold warnings help prevent accidents and ensure compliance with safety standards.

Adhesive butyl pads in Christchurch provide superior sealing solutions for automotive, construction, and marine applications. Their excellent sealing properties and ease of application make them a go-to choose for professionals.

By understanding the benefits and applications of these materials, businesses in New Zealand can make informed decisions and choose the right products for their needs. Whether you’re looking to protect your products, ensure safety, or achieve a reliable seal, these essential materials are crucial for success.

0 notes

Text

How Movie Theatres Are Adapting to Changing Viewing Habits?

In an era dominated by streaming services and on-demand content, traditional movie theatres are facing the challenge of evolving to meet the changing needs and preferences of audiences.

However, far from fading into obscurity, movie theatres are proving to be resilient entities, finding innovative ways to attract patrons and enhance the cinematic experience. Let's explore how Christchurch movie theatres are adapting to these shifting viewing habits.

Creating Immersive Experiences

One of the key strategies movie theatres are employing to stay relevant is offering immersive experiences that cannot be replicated at home. From state-of-the-art sound systems to larger-than-life screens, movie theatres are investing in technologies that enhance the cinematic journey.

Whether it's the thrill of watching an action-packed blockbuster or the awe-inspiring visuals of cutting-edge animation, movie theatres are committed to delivering an experience that goes beyond what can be achieved in a living room.

Diversifying Content

Recognising the diverse interests of audiences, movie theatres are expanding their repertoire beyond mainstream Hollywood releases. Independent films, foreign cinema, documentaries, and niche genres are finding a home on the big screen, catering to a wide range of tastes.

By diversifying their content offerings, movie theatres are not only attracting new audiences but also fostering a sense of community among film enthusiasts.

Enhancing Comfort and Convenience

Gone are the days of uncomfortable seating and long lines at the concession stand. Today's movie theatres are prioritising comfort and convenience, with plush recliners, reserved seating options, and gourmet food offerings becoming increasingly common.

Additionally, advancements in online ticketing and mobile apps have streamlined the movie theatre experience, allowing patrons to skip the queues and enjoy a hassle-free outing.

Embracing Technology

Technology is playing a significant role in the evolution of movie theatres. From digital projection systems to virtual reality experiences, Christchurch movie theatres are leveraging technology to captivate audiences in new and exciting ways.

Interactive lobby displays, augmented reality games, and immersive pre-show experiences are just a few examples of how movie theatres are embracing the digital age to create memorable moments for moviegoers.

Fostering Community Engagement

Movie theatres are more than just venues for watching films—they are hubs for cultural exchange and community engagement. Through special events, film festivals, and Q&A sessions with filmmakers, movie theatres are fostering connections between audiences and the art of cinema.

By actively engaging with their communities, movie theatres cultivate loyal followings and solidify their place as cultural institutions.

Adapting to Hybrid Models

In response to the rise of streaming platforms, some movie theatres are embracing hybrid models that combine traditional theatrical releases with simultaneous digital releases. By offering flexibility and choice to audiences, movie theatres are staying competitive in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

Whether it's through day-and-date releases or exclusive theatrical windows, movie theatres are finding ways to coexist with streaming services while preserving the magic of the big-screen experience.

Conclusion

Movie theatres are undergoing a transformation to meet the evolving needs of modern audiences. By prioritising immersive experiences, diversifying content, enhancing comfort and convenience, embracing technology, fostering community engagement, and adapting to hybrid models, Christchurch movie theatres are not only surviving but thriving in an ever-changing landscape.

So, the next time you're in the mood for a cinematic adventure, consider stepping out to your local movie theatre and rediscovering the magic of the silver screen.

0 notes

Text

If one needs reminding of the controversy (because all of this went down in 2018 and the internet's memory is notoriously short), this article from the New Yorker covers it.

Dan Mallory, a book editor turned novelist, is tall, good-looking, and clever. His novel, “The Woman in the Window,” which was published under a lightly worn pseudonym, A. J. Finn, was the hit psychological thriller of the past year. Like “Gone Girl,” by Gillian Flynn (2012), and “The Girl on the Train,” by Paula Hawkins (2015), each of which has sold millions of copies, Mallory’s novel, published in January, 2018, features an unreliable first-person female narrator, an apparent murder, and a possible psychopath.

Mallory sold the novel in a two-book, two-million-dollar deal. He dedicated it to a man he has described as an ex-boyfriend, and secured a blurb from Stephen King: “One of those rare books that really is unputdownable.” Mallory was profiled in the Times, and the novel was reviewed in this magazine. A Washington Post critic contended that Mallory’s prose “caresses us.” The novel entered the Times best-seller list at No. 1—the first time in twelve years that a début novel had done so. A film adaptation, starring Amy Adams and Gary Oldman, was shot in New York last year. Mallory has said that his second novel is likely to appear in early 2020—coinciding, he hopes, with the Oscar ceremony at which the film of “The Woman in the Window” will be honored. Translation rights have been acquired in more than forty foreign markets.

Mallory can be delightful company. Jonathan Karp, the publisher of Simon & Schuster, recently recalled that Mallory, as a junior colleague in the New York book world, had been “charming, brilliant,” and a “terrific writer of e-mail.” Tess Gerritsen, the crime writer, met Mallory more than a decade ago, when he was an editorial assistant; she remembers him as “a charming young man” who wrote deft jacket copy. Craig Raine, the British poet and academic, told me that Mallory had been a “charming and talented” graduate student at Oxford; there, Mallory had focussed his studies on Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley novels, which are about a charming, brilliant impostor.

Now thirty-nine, Mallory lives in New York, in Chelsea. He spent much of the past year travelling—Spain, Bulgaria, Estonia—for interviews and panel discussions. He repeated entertaining, upbeat remarks about his love of Alfred Hitchcock and French bulldogs. When he made an unscheduled appearance at a gathering of bloggers in São Paulo, he was greeted with pop-star screams.

One evening in September, in Christchurch, New Zealand, Mallory sat down in the bar of the hotel where he and other guests of a literary festival were staying. Tom Scott, an editorial cartoonist and a screenwriter, was struck by Mallory’s self-assurance, which reminded him of Sam Shepard’s representation of Chuck Yeager, the test pilot, in the film “The Right Stuff.” “He came in wearing the same kind of bomber jacket,” Scott said recently, in a fondly teasing tone. “An incredibly good-looking guy. He sat down and plonked one leg over the arm of his chair, and swung that leg casually, and within two minutes he’d mentioned that he had the best-selling novel in the world this year.” Mallory also noted that he’d been paid a million dollars for the movie rights to “The Woman in the Window.” Scott said, “He was enjoying his success so much. It was almost like an outsider looking in on his own success.”

Mallory and Scott later appeared at a festival event that took the form of a lighthearted debate between two teams. The audience was rowdy; Scott recalled that, when it was Mallory’s turn to speak, he flipped the room’s mood. He announced that he was going “off script” to share something personal—for what Scott understood to be the first time. Mallory said that once, in order to alleviate depression, he had undergone electroconvulsive therapy, three times a week, for one or two months. It had “worked,” Mallory noted, adding, “I’m very grateful.” He said that he still had ECT treatments once a year. “You knew he was telling us something that was really true,” Scott recalled. In the room, there was “a huge surge of sympathy.”

Mallory had frequently referred to electroconvulsive therapy before. But, in those instances, he had included it in a list of therapies that he had considered unsatisfactory in the years between 2001, when he graduated from Duke University, and 2015, when he was given a diagnosis of bipolar II disorder, and found relief through medication. In a talk that Mallory gave at a library in Centennial, Colorado, soon after his book’s publication, he said, “I resorted to hypnotherapy, to electroconvulsive therapy, to ketamine therapy, to retail therapy.”

In that talk, as in dozens of appearances, Mallory adopted a tone of witty self-deprecation. (An audience member asked him if he’d considered a career in standup comedy.) But Mallory’s central theme was that, although depression may have caused him to think poorly of himself, he was in fact a tremendous success. “I’ve thrived on both sides of the Atlantic,” he said. “I’m like Adele!” He’d reached a mass readership with a first novel that, he said, had honored E. M. Forster’s exhortation in “Howards End”: “Only connect.” Mallory described himself as a man “of discipline and compassion.”

Mallory also explained that he had come to accept that he was attractive—or “semi-fit to be viewed by the semi-naked eye.” On a trip to China, he had been told so by his “host family.” At a talk two weeks later, he repeated the anecdote but identified the host family as Japanese.

Such storytelling is hardly scandalous. Mallory was taking his first steps as a public figure. Most people have jazzed up an anecdote, and it is a novelist’s job to manipulate an audience.

But in Colorado Mallory went further. He said that, while he was working at an imprint of the publisher Little, Brown, in London, between 2009 and 2012, “The Cuckoo’s Calling,” a thriller submitted pseudonymously by J. K. Rowling, had been published on his recommendation. He said that he had taught at Oxford University, where he had received a doctorate. “You got a problem with that?” he added, to laughter.

Mallory doesn’t have a doctorate from Oxford. Although he may have read Rowling’s manuscript, it was not published on his recommendation. (And he never “worked with” Tina Fey at Little, Brown, as an official biography of Mallory claimed; a representative for Fey recently said that “he was not an editor in any capacity on Tina’s book.”)

Moreover, according to many people who know him, Mallory has a history of imposture, and of duping people with false stories about disease and death. Long before he wrote fiction professionally, Mallory was experimenting with gothic personal fictions, apparently designed to get attention, bring him advancement, or to explain away failings. “Money and power were important to him,” a former publishing colleague told me. “But so was drama, and securing people’s sympathies.”

In 2001, Jeffrey Archer, the British novelist, began a two-year prison sentence for perjury and perverting the course of justice. Nobody has accused Dan Mallory of breaking the law, or of lying under oath, but his behavior has struck many as calculated and extreme. The former colleague said that Mallory was “clever and careful” in his “ruthless” deceptions: “If there was something that he wanted and there was a way he could position himself to get it, he would. If there was a story to tell that would help him, he would tell it.” This doesn’t look like poetic license, ordinary cockiness, or Nabokovian game-playing; nor is it behavior associated with bipolar II disorder.

In 2016, midway through the auction for “The Woman in the Window,” the author’s real name was revealed to bidders. At that point, most publishing houses dropped out. This move reflected an industry-wide unease with Mallory that never became public, and that did not stand in the way of his enrichment: William Morrow, Mallory’s employer at the time, kept bidding, and bought his book.

Mallory had by then spent a decade in publishing, in London and New York, and many people in the profession had heard rumors about him, including the suggestion that he had left jobs under peculiar circumstances. Several former colleagues of Mallory’s who were interviewed for this article recalled feeling deeply unnerved by him. One, in London, said, “He exploited people who were sweet-natured.” A colleague at William Morrow told friends, “There’s this guy in my office who’s got a ‘Talented Mr. Ripley’ thing going on.” In 2013, Sophie Hannah, the esteemed British crime-fiction writer, whose work includes the sanctioned continuation of Agatha Christie’s series of detective novels, was one of Mallory’s authors; she came to distrust accounts that he had given about being gravely ill.

I recently called a senior editor at a New York publishing company to discuss the experience of working with Mallory. “My God,” the editor said, with a laugh. “I knew I’d get this call. I didn’t know if it would be you or the F.B.I.”

Craig Raine taught English literature at New College, Oxford, for twenty years, until his retirement, in 2010. Every spring, he read applications from students who, having been accepted by Oxford to pursue a doctorate in English, hoped to be attached to New College during their studies. A decade or so ago, Raine read an application from Dan Mallory, which described a proposed thesis on homoeroticism in Patricia Highsmith’s fiction. Unusually, the application included an extended personal statement.

Raine, telling me about the essay during a phone conversation a few months ago, called it an astonishing piece of writing that described almost unbearable family suffering. The essay sought to explain why Mallory’s performance as a master’s student at Oxford, a few years earlier, had been good but not brilliant. Mallory said that his studies had been disrupted by visits to America, to nurse his mother, who had breast cancer. Raine recalled, “He had a brother, who was mentally disadvantaged, and also had cystic fibrosis. The brother died while being nursed by him. And Dan was supporting the family as well. And the mother gradually died.” According to Raine, Mallory had described how his mother rejected the idea of suffering without complaint. Mallory often read aloud to her the passage in “Little Women” in which Beth dies, with meek, tidy stoicism, so that his mother “could sneer at it, basically.”

Raine went on, “At some point, when Dan was nursing her, he got a brain tumor, which he didn’t tell her about, because he thought it would be upsetting to her. And, evidently, that sort of cleared up. And then she died. The brother had already died.”

Raine admired the essay because it “knew it was moving but didn’t exaggerate—it was written calmly.” Raine is the longtime editor of Areté, a literary magazine, and he not only helped Mallory secure a place at New College; he invited him to expand the essay for publication. “He worked at it for a couple of months,” Raine said. “Then he said that, after all, he didn’t think he could do it.” Mallory explained that his mother, a private person, might have preferred that he not publish. Instead, he reviewed a collection of essays by the poet Geoffrey Hill.

Pamela Mallory, Dan’s mother, does seem to be a private person: her Instagram account is locked. When I briefly met her, some weeks after I’d spoken to Raine, she declined to be interviewed. She lives for at least part of the year in a large house in Amagansett, near the Devon Yacht Club, where a celebratory lunch was held for Mallory last year. (On Instagram, he once posted a video clip of the club’s exterior, captioned, “The first rule of yacht club is: you do not talk about yacht club.”) In 2013, at a country club in Charlotte, North Carolina, Pamela Mallory attended the wedding reception of her younger son, John, who goes by Jake, and who was then working at Wells Fargo. At the wedding, she and Dan danced. This year, Pamela and other family members were photographed at a talk that Dan gave at Queens University of Charlotte. Dan has described travelling with his mother on a publicity trip to New Zealand. “Only one of us will make it back alive,” he joked to a reporter. “She’s quite spirited.”

I told Raine that Mallory’s mother was not dead. There was a pause, and then he said, “If she’s alive, he lied.” Raine underscored that he had taken Mallory’s essay to be factual. He asked me, “Is the father alive? In the account I read, I’m almost a hundred per cent certain that the father is dead.” The senior John Mallory, once an executive at the Bank of America in Charlotte, also attended the event at Queens University. He and Pamela have been married for more than forty years.

Dan Mallory, who turned down requests to be interviewed for this article, was born in 1979, into a family that he has called “very, very Waspy,” even though his parents both had a Catholic education and he has described himself as having been a “precocious Catholic” in childhood. His maternal grandfather, John Barton Poor, was the chairman and chief executive of R.K.O. General, which owned TV and radio stations. Mallory was perhaps referring to Poor when, as an undergraduate at Duke, he wrote in a student paper that, at the age of nine, he had “slammed the keyboard cover of my grandfather’s Steinway onto my exposed penis.” The article continued, “As I beheld the flushed member pinned against the ivories like the snakeling in Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, I immediately feared my urinating days were over.”

Dan and Jake Mallory have two sisters, Hope and Elizabeth. When Dan was nine or so, the family moved from Garden City, on Long Island, to Virginia, and then to Charlotte, where he attended Charlotte Latin, a private school. The family spent summers in Amagansett. In interviews, Mallory has sometimes joked that he was unpopular as a teen-ager, but Matt Cloud, a Charlotte Latin classmate, recently told me, by e-mail, that “Dan’s the best,” and was “a stellar performer” in a school production of “Arsenic and Old Lace.”

In 1999, at the end of Mallory’s sophomore year in college, he published an article in the Duke Chronicle which purported to describe events that had occurred a few years earlier, when he was seventeen; he wrote that he was then living in a single-parent household. The piece, titled “Take Full Advantage of Suffering,” began:

From a dim corner of her hospital room I surveyed the patient, who appeared, tucked primly under the crisp sheets, not so much recouping from surgery as steeped in a late-evening reverie. Her blank face registered none of the pristine grimness which so often pervades medical environs; hopeful hints of rose could be discerned in her pale skin; and with each gentle inhalation, her chest lifted slowly but reassuringly heavenward. Mine, by contrast, palpitated so furiously that I braced myself for cardiac arrest.

I do not know whether she spied me as I gazed downward, contemplating the unjustly colloquial sound of “lumpectomy,” or if some primally maternal instinct alerted her to my presence, but in a coarse, ragged voice, she breathed my name: “Dan.”

His mother, he wrote, urged him “to write to your colleges and tell them your mother has cancer.” Mallory said that he complied, adding, “I hardly feel I capitalized on tragedy—rather, I merely squeezed lemonade from the proverbial lemons.” In college applications, he noted, “I lamented, in the sweeping, tragic prose of a Brontë sister, the unsettling darkness of the master bedroom, where my mother, reeling from bombardments of chemotherapy, lay for days huddled in a fetal position.”

This strategy apparently failed with Princeton. In the article, Mallory recalled writing to Fred Hargadon, then Princeton’s dean of admissions. “You heartless bastard,” the letter supposedly began. “What kind of latter-day Stalin refuses admission to someone in my plight? Not that I ever seriously considered gracing your godforsaken institution with my presence—you should be so lucky—but I’m nonetheless relieved to know that I won’t be attending a university whose administrators opt to ignore oncological afflictions; perhaps if I’d followed the example of your prized student Lyle Menendez and killed my mother, things would have turned out differently.”

Mallory ended his article with an exhortation to his readers: “Make suffering worth it. When the silver lining proves elusive, when the situation cannot be helped, nothing empowers so much as working for one’s own advantage.”

At some point in Mallory’s teen years, I learned, his mother did have cancer. But the essay feels like a blueprint for the manipulations later exerted on Craig Raine and others: inspiring pity and furthering ambition while holding a pose of insouciance.

In the summer of 1999, Mallory interned at New Line Cinema, in New York. He later claimed, in the Duke Chronicle, that he “whiled away” the summer “polishing” the horror film “Final Destination,” directed by James Wong. “We need a young person like you to sex it up,” Mallory recalled being told. Wong told me that Mallory did not work on the script.

Mallory spent his junior year abroad, at Oxford, and the experience “changed my attitude toward life,” he told Duke Today in 2001. “I discovered British youth culture, went out clubbing. . . . I learned it was O.K. to have fun.” While there, he published a dispatch, in the Duke student publication TowerView, describing an encounter with a would-be mugger, who asked him, “Want me to shoot your motherfucking mouth off?” Mallory responded with witty aplomb, and the mugger, cowed, scuttled “down some anonymous alley to reflect on why it is Bad To Threaten Other People, especially pushy Americans who doubt he has a gun.”

Before Oxford, Mallory had been self-contained—Jeffery West, who taught Mallory in a Duke acting class, and cast him in a production of Tom Stoppard’s “Arcadia,” said that he was then a “gawky, lanky kind of boy, an Other.” After Oxford, Mallory was bolder. Mary Carmichael, a Duke classmate and his editor at TowerView, told me that Mallory was now likely to sweep into a room. An article in the Chronicle proposed that “being center stage is a joy for Mallory.” He directed plays, which were well received, and he became a film critic for the Chronicle. He ruled that Matt Damon had been “miserably graceless” as the star of “The Talented Mr. Ripley.”

In 2001, Mallory was the student speaker at Duke’s commencement. As in his cancer article, he made a debater’s case for temerity, in part by deploying temerity. He called himself a “novelist,” and said that he had missed out on a Rhodes Scholarship only because he’d been too cutely candid in an interview: when asked what made him laugh, he’d said, “My dog,” rather than something rarefied. He described talking his way into the thesis program of Duke’s English Department, despite not having done the qualifying work. He compared his stubborn “attitude” on this matter to struggles over civil rights. In college, he said, “I had honed my personality to a fine lance, and could deploy my character as I did my intellect.”

“The Woman in the Window” is narrated by Anna Fox, an agoraphobic middle-aged woman, living alone in a Harlem brownstone, who believes that she has witnessed a violent act occurring in a neighbor’s living room. Early in 2018, when Mallory began promoting the novel, he sometimes said that he, too, had “suffered from” agoraphobia. He later said that he had never had the condition.

In an interview last January, on “Thrill Seekers,” an online radio show, the writer Alex Dolan asked Mallory about the novel’s Harlem setting. Mallory said that, when describing Anna’s house, he had kept in mind the uptown home of a family friend, with whom he had stayed when he interned in New York. After a rare hesitation, Mallory shared an anecdote: he said that he’d once accidentally locked himself in the house’s ground-floor bathroom. When he was eventually rescued, by his host, he had been trapped “for twenty-two hours and ten minutes.”

“Wow!” Dolan said.

Mallory said, “So perhaps that contributed to my fascination with agoraphobia.”

Dolan asked, “You had the discipline to, say, not kick the door down?”

Mallory, committed to twenty-two hours and ten minutes, said that he had torn a brass towel ring off the wall, straightened it into a pipe, “and sort of hacked away at the area right above the doorknob.” He continued, “I did eventually bore my way through it, but by that point my fingers were bloody, I was screaming obscenities. This is the point—of course—at which the father of the house walked in!” After Dolan asked him if he’d resorted to eating toothpaste, Mallory steered the conversation to Hitchcock.

In subsequent interviews, Mallory does not seem to have brought up this bathroom again. But the exchange gives a glimpse of the temptations and risks of hyperbole: how, under even slight pressure, an exaggeration can become further exaggerated. For a speaker more invested in advantage than in accuracy, such fabulation could be exhilarating—and might even lead to the dispatch, by disease, of a family member. I was recently told about two former publishing colleagues of Mallory’s who called him after he didn’t show up for a meeting. Mallory said that he was at home, taking care of someone’s dog. The meeting continued, as a conference call. Mallory now and then shouted, “No! Get down!” After hanging up, the two colleagues looked at each other. “There’s no dog, right?” “No.”

Between 2002 and 2004, Mallory studied for a master’s degree at Oxford. He took courses on twentieth-century literature and wrote a thesis on detective fiction. Professor John Kelly, a Yeats scholar who taught him, told me, “He wrote very challenging and creative essays. I said to him once, ‘It can be a little florid.’ I always think that’s a wonderful fault, if it is a fault—constantly looking for not just the mot juste, as it were, but to give a spin on the mot juste. And his e-mails to me were like that, too; they were always very amusing.” Chris Parris-Lamb, a New York literary agent, similarly impressed by Mallory’s e-mails, once suggested that he write a collection of humorous essays, in the mode of David Sedaris.

As Kelly recalled, by the end of the two-year course Mallory was making frequent trips to America, apparently to address serious medical issues. Kelly didn’t know the details of Mallory’s illness. “We talked in general terms,” Kelly said. “I didn’t ever press him.” Kelly also understood that Mallory’s mother had a life-threatening illness. “Alas, she did die,” Kelly told me, adding that he respected Mallory’s “forbearance.”

Mallory received his master’s in 2004 and moved to New York. He applied to be an assistant to Linda Marrow, the editorial director of Ballantine, an imprint of Random House known for commercial fiction. At his interview, he said that he had a love of popular women’s fiction, which derived from his having read it with his mother when she was gravely ill with cancer. He later said that he had once had brain cancer himself.

Mallory was given the job. He impressed Tess Gerritsen and others with his writing; he contributed a smart afterword to a reprint of “From Doon with Death,” Ruth Rendell’s first novel. Adam Korn, then a Random House assistant, who saw a lot of Mallory socially, told me that Mallory was “a good guy, lovely to talk to, very informed,” and already “serious about being a writer.” Another colleague recalled that Mallory immediately “gave off a vibe of ‘I’m too good for this.’ ” Ballantine’s books were too down-market; Mallory’s role was too administrative.

As if impatient for advancement, Mallory often used his boss’s office late at night, and worked on her computer. On a few occasions in 2007, after Mallory had announced that he would soon be leaving the company to take up doctoral studies at Oxford, people found plastic cups, filled with urine, in and near Linda Marrow’s office. These registered as messages of disdain, or as territorial marking. Mallory was suspected of responsibility but was not challenged. No similar cups were found after he quit. (Mallory, through a spokesperson, said, “I was not responsible for this.”)

A few months later, after Mallory had moved to Oxford, his former employers noticed unexplained spending, at Amazon.co.uk, on a corporate American Express card. When confronted, Mallory acknowledged that he had used the card, but insisted that it was in error. He added that he was experiencing a recurrence of cancer.

In an interview with the Duke alumni magazine last spring, Mallory said that, as someone who was “very rules-conscious,” he found Patricia Highsmith’s representation of Tom Ripley, across five novels, to be “thrilling and disturbing in equal measure.” He went on, “When you read a Sherlock Holmes story, you know that, by the end, the innocent will be redeemed or rewarded, the guilty will be punished, and justice will be upheld or restored. Highsmith subverts all that. Through some alchemy, she persuades us to root for sociopaths.”

When, in a scene partway through “The Woman in the Window,” Anna Fox thinks about another character, “He could kiss me. He could kill me,” Mallory is alluding to a pivotal moment in “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” On the Italian Riviera, Ripley and Dickie Greenleaf, a dazzling friend who is tiring of Ripley’s company, hire a motorboat and head out to sea. In the boat, Ripley considers that he “could have hit Dickie, sprung on him, or kissed him, or thrown him overboard, and nobody could have seen him.” He then beats him to death with an oar.

Back at Oxford, Mallory has said, he “anointed” Highsmith as the primary subject of his dissertation. But he doesn’t seem to have published any scholarly articles on Highsmith, and it’s not clear how much of a thesis he wrote. An Oxford arts doctorate generally takes at least three or four years; in 2009, midway through his second year, Mallory was signing e-mails, untruthfully, “Dr. Daniel Mallory.” Oxford recently confirmed to me that Mallory never completed the degree.

At Oxford, Mallory became a student-welfare officer. In a guide for New College students, he introduced himself with brio, and invited students to approach him with any issues, “even if it’s on Eurovision night.” According to Tess Gerritsen, who had drinks with him and others in Oxford one night, Mallory mentioned that he was “working on a mystery novel,” which “might have been set in Oxford, the world of the dons.”

Mallory sometimes saw John Kelly, his former professor, for drinks or dinner. “They were very, very merry occasions,” Kelly told me. He recalled that Mallory once declined an invitation to a party, saying that he would be tied up in London, supporting a cancer-related organization. Kelly was struck by Mallory’s public-spiritedness, and by his modesty. “I would have never found out about it, except he wrote to me to say, ‘I’d love to be there, but it’s going to be a long day in London.’ ” (When Kelly learned that I had some doubts about Mallory’s accounts of cancer, he said that he was “astonished.”)

At one point, Kelly noticed that Mallory no longer responded to notes sent to him through Oxford’s internal mail system: he had left the university. Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, his doctoral supervisor, recently said of Mallory, “I’m very sorry that illness interrupted his studies.” Mallory had begun looking for work in London publishing, describing himself as a former editor at Ballantine, not as an assistant. He claimed that he had two Ph.D.s: his Highsmith-related dissertation, from Oxford, and one from the psychology department of an American university, for research into Munchausen syndrome. There’s no evidence that Mallory ever undertook such research. A former colleague recalls Mallory referring to himself as a “double-doctor.”

Toward the end of 2009, he was hired as a mid-level editor at Sphere, a commercial imprint of Little, Brown. In New York, news of this event caused puzzlement: an editor then at Ballantine recalled feeling that Mallory “hadn’t done enough” to earn such a position.

One of Mallory’s London colleagues to whom I spoke at length described publishing as “a soft industry—and much more so in London than in New York.” Hiring standards in London have improved in the past decade, this colleague said, but at the time of Mallory’s hiring “it was much more a case of ‘I like the cut of your jib, you can have a job,’ rather than ‘Have you actually got a Ph.D. from Oxford, and were you an editor at Ballantine?’ ”

Mallory was amusing, well read, and ebullient, and could make a memorable first impression, over lunch, on literary agents and authors. He tended to speak almost without pause. He’d begin with rapturous flattery—he told Louise Penny, the Canadian mystery writer, that he’d read her manuscript three times, once “just for fun”—and then shift to self-regard. He wittily skewered acquaintances and seemed always conscious of his physical allure. He’d say, in passing, that he’d modelled for Guess jeans—“runway only”—or that he’d appeared on the cover of Russian Vogue. He mentioned a friendship with Ricky Martin.

This display was at times professionally effective. In a blog post written after signing with Little, Brown, Penny excitedly described Mallory as a former “Oxford professor of literature.” Referring to the bond between author and editor, she added, “It is such an intimate relationship, there needs to be trust.”

Others found his behavior off-putting; it seemed unsuited to building long-term professional relationships. The London colleague said, “He was so full-on. I thought, My God, what’s going on? It was performative and calculating.” A Little, Brown colleague, who was initially impressed by Mallory, said, “He was not modest, ever.” The colleague noted that many editors got into trouble by disregarding sales and focussing only on books that they loved, adding, “That certainly never happened with him.” Little, Brown authors were often “seduced by Dan” at first but then “became disenchanted” when he was “late with his edits or got someone else to do them.”

Mallory, who had just turned thirty, told colleagues that he was impatient to rise. He found friends in the company’s higher ranks. Having acquired a princeling status, he used it to denigrate colleagues. The London colleague said that Mallory would tell his superiors, “This is a bunch of dullards working for you.” Another colleague said of Mallory, “When he likes you, it’s like the sun shining on you.” But Mallory’s contempt for perceived enemies was disconcertingly sharp. “You don’t want to get on the wrong side of that,” the colleague recalled thinking.

Mallory moved into an apartment in Shoreditch, in East London. He wasn’t seen at publishing parties, and one colleague wondered if his extroversion at lunch meetings served “to disguise crippling shyness” and habits of solitude. On his book tour, Mallory has said that depression “blighted, blotted, and blackened” his adult life. A former colleague of his told me that Mallory seemed to be driven by fears of no longer being seen as a “golden boy.”

In the summer of 2010, Mallory told Little, Brown about a job offer from a London competitor. He was promised a raise and a promotion. A press release announcing Mallory’s elevation described him as “entrepreneurial and a true team player.”

By then, Mallory had made it widely known to co-workers that he had an inoperable brain tumor. He’d survived earlier bouts with cancer, but now a doctor had told him that a tumor would kill him by the age of forty. He seemed to be saying that cancer—already identified and unequivocally fatal—would allow him to live for almost another decade. The claim sounds more like a goblin’s curse than like a prognosis, but Mallory was persuasive; the colleague who was initially supportive of him recently said, with a shake of the head, “Yes, I believed that.”

Some co-workers wept after hearing the news. Mallory told people that he was seeking experimental treatments. He took time off. In Little, Brown’s open-plan office, helium-filled “Get Well” balloons swayed over Mallory’s desk. For a while, he wore a baseball cap, even indoors, which was thought to hide hair loss from chemotherapy. He explained that he hadn’t yet told his parents about his diagnosis, as they were aloof and unaffectionate. Before the office closed for Christmas in 2011, Mallory said that, as his parents had no interest in seeing him, he would instead make an exploratory visit to the facilities of Dignitas, the assisted-death nonprofit based in Switzerland. A Dignitas death occurs in a small house next to a machine-parts factory; there’s no tradition of showing this space to possible future patients. Mallory said that he had found his visit peaceful.

Sources told me that, a few months later, Ursula Mackenzie, then Little, Brown’s C.E.O., attended a dinner where she sat next to the C.E.O. of the publishing house whose job offer had led to Mallory’s promotion. The rival C.E.O. told Mackenzie that there had been no such offer. (Mackenzie declined to comment. The rival C.E.O. did not reply to requests for comment.) When challenged at Little, Brown, Mallory claimed that the rival C.E.O. was lying, in reprisal for Mallory’s having once rejected a sexual proposition.

In August, 2012, Mallory left Little, Brown. The terms of his departure are covered by a nondisclosure agreement. But it’s clear that Little, Brown did not find Mallory’s response about the job offer convincing. “And, once that fell away, then you obviously think, Is he really ill?” the once supportive colleague said. Everything now looked doubtful, “even to the extent of ‘Does his family exist?’ and ‘Is he even called Dan Mallory?’ ”

Mallory was not fired. This fact points to the strength of employee protections in the U.K.—it’s hard to prove the absence of a job offer—but also, perhaps, to a sense of embarrassment and dread. The prospect of Mallory’s public antagonism was evidently alarming: Little, Brown was conscious of the risks of “a fantasist walking around telling lies,” an employee at the company told me. Another source made a joking reference to “The Talented Mr. Ripley”: “He could come at me with an axe. Or an oar.”

In protecting his career, Mallory held the advantage of his own failings: Little, Brown’s reputation would have been harmed by the knowledge that it had hired, and then promoted, a habitual liar. When Mallory left, many of his colleagues were unaware of any unpleasantness. There was even a small, awkward dinner in his honor.

Two weeks before Mallory left Little, Brown, it was announced that he had accepted a job in New York, as an executive editor at William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins. Publishing professionals estimate that his starting salary was at least two hundred thousand dollars a year. That fall, he moved into an apartment in a sixty-floor tower, with a pool, in midtown, and into an office at Morrow, on Fifty-third Street.

He had been hired by Liate Stehlik, Morrow’s widely admired publisher. It’s not clear if Stehlik heard rumors about Mallory’s unreliability—or, to use the words of a former Morrow colleague, the fact that “London had ended in some sort of ball of flame.” Stehlik did not reply to requests for comment for this article.

Whereas in London Mallory had sometimes seemed like a British satire of American bluster, in New York he came off as British. He spoke with an English accent and said “brilliant,” “bloody,” and “Where’s the loo?”—as one colleague put it, he was “a grown man walking around with a fake accent that everyone knows is fake.” The habit lasted for years, and one can find a postman, not a mailman, in “The Woman in the Window.”

Some book editors immerse themselves in text; others focus on making deals. Mallory was firmly of the latter type, and specialized in acquiring established authors who had an international reach. Before the end of 2012, he had signed Wilbur Smith—once a giant in popular historical fiction (and now, as Mallory put it in an e-mail to friends, “approximately four centuries old”).

At some point that winter, Mallory stopped coming into the office. This mystified colleagues, who were given no explanation.

On February 12, 2013, some people in London who knew Mallory professionally received a group e-mail from Jake Mallory, Dan’s brother, whom they’d never met. Writing from a Gmail address, Jake said that Dan would be going to the hospital the next day, for the removal of a tumor. He’d be having “complicated surgery with several high risk factors, including the possibility of paralysis and/or the loss of function below the waist.” But, Jake went on, “Dan has been through worse and has pointed out that if he could make it through Love Actually alive, this surgery holds no terrors.” Dan would eat “an early dinner of sashimi and will then read a book about dogs until bedtime,” Jake wrote, adding, “Dan was treated terribly by people throughout his childhood and teenage years and into his twenties, which left him a very deeply lonely person, so he does not like/trust many people. Please keep him in your thoughts.”

That e-mail appears to have been addressed exclusively to contacts in the U.K. The next day, Jake sent an e-mail to acquaintances of Dan’s in the New York publishing world. It noted that Dan would soon be undergoing surgery to address “a tumor in his spine,” adding, “This isn’t the first (or even second) time that Dan has had to undergo this sort of treatment, so he knows the drill, although it’s still an unpleasant and frightening proposition. He says that he is looking forward to being fitted with a spinal-fluid drain and that this will render him half-man, half-machine.”

Recipients wrote back in distress. An editor at a rival publishing house told me, “I totally fell for it. After all, who would fabricate such a story? I sent books and sympathies.” In time, Jake’s exchanges with this editor became “quippy and upbeat.” Another correspondent told Jake that his writing was as droll as Dan’s.

Jake’s styling of “e.mail” was unusual. The next week, Dan wrote to Chris Parris-Lamb, the agent. He began, “Wanted to thank you for your very lovely e.mail to my brother.”

Given the idiosyncrasy of “e.mail”—and given Dan’s taste for crafted zingers, and his history of fabrication—it’s now easy to suppose, as one recipient put it, that “something crazy was going on,” and that “Jake” was Dan. Like Tom Ripley writing letters that were taken as the work of the murdered Dickie Greenleaf, Dan was apparently communicating with friends in a fictional voice. (Online impersonations also figure in the plot of “The Woman in the Window.”)

Jake Mallory is thirty-five. He’s a little shorter than Dan, and doesn’t have the same lacrosse-player combination of strong chin and floppy hair. The week of Dan’s alleged surgery, while Jake was supposedly by his side in New York, Jake’s fiancée posted on Facebook a professional “pre-wedding” photograph of the couple. In it, she and Jake, who got married that summer, look happy and hopeful. Jake Mallory did not respond to requests for comment. Dan Mallory, through the spokesperson, said that he was “not the author of the e-mails” sent by “Jake.”

On February 14, 2013, a “Jake” message to New York contacts described overnight surgery—uncommon timing for a scheduled procedure—in an unspecified hospital. “My brother’s 7-hour surgery ended early this morning,” the e-mail began. “He experienced significant blood loss—more so than is common during spinal surgeries, so it required two transfusions. However, the tumor appears to have been completely removed. His very first words upon waking up were ‘I need vodka.’ ” I was told that a recipient sent vodka to Dan’s apartment, and was thanked by “Jake,” who reported that his brother roused himself just long enough to say that the sender was a goddess.

The ventriloquism is halfhearted. Dan’s own voice keeps intruding, and the hurried sequence of events suggests anxiety about getting the patient home, and returning him to a sparer, mythic narrative of endurance and wit. While in a New York hospital, Dan was a dot on the map, exposed to visitors. Reports from the ward would require the clutter of realist fiction: medical devices, doctors with names.

“Jake” continued, “He has been fitted with a ‘lumbar drain’ in his back to drain his spinal fluid. The pain is apparently quite severe, but he is on medicine.” (A Britishism.) “He is not in great shape but did manage to ask if he could keep the tumor as a pet. He will most likely be going home today.”

On February 15th, “Jake” wrote an e-mail to Parris-Lamb: “We’re anticipating a week or so of concentrated rest, the only trick will be finding enough reading material to keep his brain occupied.” A week later, Dan Mallory, writing from his own e-mail address, sent Parris-Lamb the note thanking him for the “very lovely e.mail”—which, he said, had “warmed my black heart.” Mallory went on, “Today I start weaning myself—I’ll just let that clause stand on its own for a minute; are you gagging yet?—off my sweet sweet Vicodin, so am at last fit to correspond. Feeling quite spry; the wound is healing nicely, and I’m no longer wobbly on my feet. Not when sober, at any rate.”

Mallory suggested meeting the agent for drinks, or dinner, a week or two later. Writing to another contact, he described an impending trip to London, for which he was packing little more than “a motheaten jumper.” On February 26th, twelve days after seven-hour spinal surgery, Mallory wrote to Parris-Lamb to say that he was in Nashville, for work.

Three days later, “Jake” wrote another group e-mail, saying that “an allergic reaction to a new pain killer” had caused Dan “to go into shock and cardiac arrest.” He went on, “He was taken to the hospital on time and treated immediately and is out of intensive care (still on a respirator and under sedation). While this setback is not welcome it is not permanent either, and at least Dan can now say he has had two lucky escapes in the space of two months.” “Jake” went on, “The worst is past and we are hoping he can go back to his apartment this weekend and then pick up where he left off. This would daunt a mere mortal but not my brother.”

At the end of March, late at night, “Jake” wrote again to London contacts. Dan was “in decent physical shape,” but was upset about the “painful upheaval” of the previous year—and about an e-mail, written by an unnamed Little, Brown executive, that seemed to “poke fun at him.” Dan felt “utterly let down” and was “withdrawing into himself like a turtle.”

“Jake” noted that Dan had been “working with abused children and infants at the hospital where he was treated.” The previous week, “Jake” had seen Dan “talking to a little girl whose arm had been broken for her,” he wrote, adding, “My brother’s arm was broken for him when he was a baby.” This phrasing seems to stop just short of alleging parental abuse. (The theme of childhood victimization, sometimes an element of “Jake” e-mails sent to London associates, did not appear in the New York e-mails.) “Jake” went on, “He wrote the little girl a story about a hedgehog in his nicest handwriting to show her how she could rebound from a bad experience. I want for him to do the same, although I understand that he is tired of having to rebound from things.”

The same night the “Jake” e-mail was sent, an ex-colleague of Mallory’s at Little, Brown received an anonymous e-mail calling her one of the “nastiest c*nts in publishing.” Mallory was asked about the e-mail, and was told that Little, Brown would contact law enforcement if anything similar happened again. It didn’t. (Through the spokesperson, Mallory said that he did not write the message and “does not recall being warned” about it.) In “The Woman in the Window,” Anna Fox seeks advice about a threatening anonymous e-mail, and is told that “there’s no way to trace a Gmail account.”

A week later, in an apparent attempt at a reset, Dan Mallory wrote a breezy group e-mail under his own name. The cancer surgery, he said, had been “a total success.” A metal contraption was attached to his spine, so he was now “half-man, half-machine.” He noted that he’d just seen “Matilda” with his parents.

When Mallory returned to work that spring, after several weeks, nothing was said. A former co-worker at Morrow, who admires him and still has only the vaguest sense of a health issue, told me that Mallory “seemed the same as before.” He hadn’t lost any weight or hair.

After his return, Mallory came to work on a highly irregular schedule. Unlike other editors, he rarely attended Wednesday-afternoon editorial meetings. At one point, another co-worker began keeping a log of Mallory’s absences.

Mallory bought a one-bedroom apartment in Chelsea, for six hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars. He decorated it with images and models of dogs, a framed sign reading “Amagansett,” and a reproduction of a seventeenth-century engraving of New College, Oxford.

Morrow executives either believed that Mallory’s cancer story was real or decided to live with the fact that it was not. Explaining Morrow’s accommodation of its employee, a former colleague said that Mallory’s focus on international deals protected him, adding, “Nothing’s more important than global authors.” The co-worker went on, “There’s a horror movie where all the teachers in a school have been infected by an alien parasite. The kids realize it, and of course nobody believes them. That’s what it felt like.” The co-worker described Mallory’s “gaslighting, lying, and manipulation” in the workplace as cruel, but noted, “People don’t care, if it’s not sexual harassment.” A Morrow spokesperson released a statement: “We don’t comment on the personal lives of our employees or authors. Professionally, Dan was a highly valued editor, and the publication of ‘The Woman in the Window’—a #1 New York Times bestseller out of the gate, and the bestselling debut novel of 2018—speaks for itself.”

An acquaintance of Mallory’s recently said that “there’s not a lot of confrontation” in publishing. “It’s a business based on hope. You never know what’s going to work.” In the industry, rumors about the “Jake” e-mails were contained—perhaps by discretion or out of people’s embarrassment about having been taken in.

I recently spoke with Victoria Sanders, an agent who represents Karin Slaughter, the thriller writer. In 2015, Slaughter signed a three-book deal, for more than ten million dollars, involving Mallory and a British counterpart. Sanders viewed Mallory as Slaughter’s “quarterback,” adding, “His level of engagement made him really quite extraordinary.”

The editor at a rival publishing house who’d had “quippy” exchanges with the Jake persona said of the episode, “Even now it seems a bizarre, eccentric game, but not threatening.” “Jake” hadn’t asked for cash, so it wasn’t an “injurious scam.” The editor said, “This seemed almost performance art.” Chris Parris-Lamb, however, was affronted, in part because someone close to him had recently died from cancer.

The acquaintance who described an industry “based on hope” didn’t see Mallory for a few years, then made plans to meet him for a work-related drink, in Manhattan. Mallory said that he was now well, except for an eye problem. His eye began to twitch. Mallory’s companion asked after Jake. “Oh, he’s dead,” Mallory said. “Yes, he committed suicide.” The acquaintance recalled to me that, at that moment, “I just knew I was never going to correspond or deal with him again.”

In 2013, Sophie Hannah met Mallory for the first time, over lunch in New York. They discussed plans, already set in motion in London, for Hannah to write the first official Agatha Christie continuation novel. William Morrow would publish it in the U.S. They also discussed Hannah’s non-Christie fiction, which later also came to Morrow. Hannah, who lives in Cambridge, recently said by phone that they quickly became friends. Mallory “renewed my creative energy,” she said. He had a knack for “giving feedback in the form of praise for exactly the things I’m proud of.”

Hannah seems to have found, in Mallory, a remarkable source of material. In 2015, she completed her second Hercule Poirot novel, “Closed Casket.” Poirot is a guest at an Irish country house, and meets Joseph Scotcher, a character whose role can’t be described without spoilers. Scotcher is a charming young flatterer who has told everyone that he is terminally ill, with kidney disease. During Poirot’s visit, Scotcher is murdered, and an autopsy reveals that his kidneys were healthy.

After the murder, Randall Kimpton, an American doctor who is also staying in the house, tells Poirot that he’d become friendly with Scotcher years earlier, at Oxford; he had begun to doubt Scotcher’s dire prognosis, while thinking that “surely no one would tell a lie of such enormity.” Kimpton tells Poirot that he was once approached by someone claiming to be Scotcher’s brother. This brother, who looked identical to Scotcher except for darker skin and a wild beard, had confirmed the kidney disease, and Kimpton had decided “no man of honor would agree to tell a stranger that his brother was dying if it were not so.” But the supposed brother had then accidentally revealed himself to be Scotcher, wearing a beard glued to his face.

A seductive man lies about a fatal disease, then defends the lie by pretending to be his brother. The brother’s name is Blake. When I asked Hannah if the plot was inspired by real events, she was evasive, and more than once she said, “I really like Dan, and he’s only ever been good to me.” She also noted that, before starting to write “Closed Casket,” she described its plot to Mallory: “He said, ‘Yes, that sounds amazing!’ ” Hannah, then, can’t be accused of discourtesy.

But she acknowledged that there were “obvious parallels” between “Closed Casket” and “rumors that circulated” about Mallory. She also admitted that the character of Kimpton, the American doctor, owes something to her former editor. I had noticed that Kimpton speaks with an affected English accent and—in what works as a fine portrait of Mallory, mid-flow—has eyes that “seemed to flare and subside as his lips moved.” The passage continues, “These wide-eyed flares were only seconds apart, and appeared to want to convey enthusiastic emphasis. One was left with the impression that every third or fourth word he uttered was a source of delight to him.” (Chris Parris-Lamb, shown these sentences, said, “My God! That’s so good.”) While Hannah was writing “Closed Casket,” her private working title for the novel was “You’re So Vain, You Probably Think This Poirot’s About You.”

A publishing employee in New York told me that, in 2013, Hannah had become suspicious that Mallory wasn��t telling the truth when he spoke of making a trip to the U.K. for cancer treatment, and had hired a detective to investigate. This suggestion seemed to be supported by an account, on Hannah’s blog, of hiring a private detective that summer. Hannah wrote that she had called him to describe a “weird conundrum.” Later, during a vacation with her husband in Agatha Christie’s country house, in Devon, she called to check on the detective’s progress; he told her that “there was a rumor going round that X is the case.”

“You’re supposed to be finding out if X is true,” Hannah told the detective.

“I’m not sure how we could really do that,” he replied. “Not without hacking e-mail accounts and things like that—and that’s illegal.”

Asked about the blog post, Hannah told me that she had thought of hiring a detective to check on Mallory, and had discussed the idea with friends, but hadn’t followed through. She had, however, hired a detective to investigate a graffiti problem in Cambridge. I said that I found this hard to believe. She went on to say that she had forgotten the detective’s name, she had deleted all her old e-mails, and she didn’t want to bother her husband and ask him to confirm the graffiti story. All this encouraged the thought that the novelist now writing as Agatha Christie had hired a detective to investigate her editor, whom she suspected of lying about a fatal disease.

Hannah—who, according to several people who know her, has a great appetite for discussing Mallory at parties—also seems to have made fictional use of him in her non-Poirot writing. “The Warning,” a short story about psychopathic manipulations, includes an extraordinarily charming man, Tom Rigbey, who loves bull terriers. Hannah recently co-wrote a musical mystery, “The Generalist”; its plot features a successful romance novelist who feels that her publisher has become neglectful, after writing a best-seller of his own.

An American woman in mid-career, a psychologist with a Ph.D. and professional experience of psychopathy, is trapped in her large home by agoraphobia. She has been there for about a year, after a personal trauma. If she tries to go outside, the world spins. She drinks too much, and recklessly combines alcohol and anti-anxiety medication. Police officers distrust her judgment. Online, she plays chess and contributes to a forum for stress-sufferers, a place where danger lies.

This is the setup for “Copycat,” a spirited 1995 thriller, set in San Francisco, starring Sigourney Weaver and Holly Hunter. It also describes “The Woman in the Window.” In “Copycat,” the psychologist’s forum log-in is She Doc. In “Window,” it’s THEDOCTORISIN.

“The Woman in the Window” acknowledges a debt to the film “Rear Window,” by making Anna Fox a fan of noir movies and Hitchcock. And Mallory has publicly referred a few times to “The Girl on the Train,” a well-told story about a boozily unreliable witness, a woman much like Mallory’s boozily unreliable witness. But he hasn’t acknowledged “Copycat”—unless one decides that when, in “The Woman in the Window,” a photograph with a time stamp in its corner downloads from the Internet at a suspenseful, dial-up speed, it is an homage to the same scene in “Copycat,” rather than an indictment of Internet service providers in Manhattan.

When I e-mailed Jon Amiel, the director of “Copycat,” about parallels between the two narratives, he replied, “Wow.” Later, on the phone, he proposed that the debt was probably “not actionable, but certainly worth noting, and one would have hoped that the author might have noted it himself.”

The official origin myth of “The Woman in the Window” feels underwritten. In the summer of 2015, Mallory has said, he was at home for some weeks, adjusting to a new medication. He rewatched “Rear Window,” and noticed a neighbor in the apartment across the street. “How funny,” he said to himself. “Voyeurism dies hard!” A story suggested itself. Mallory is more cogent when reflecting on his shrewdness regarding the marketplace—when he talks about his novel in the voice of a startup C.E.O. pitching for funds. “I bring to ‘The Woman in the Window’ more than thirty years of experience in the genre,” he told a crime-fiction blogger last winter. He explained to a podcast host that, before “Gone Girl,” there had been “no branding” for psychological suspense; afterward, there was vast commercial opportunity. Mallory has said that he favored the pseudonym A. J. Finn in part for its legibility on a small screen, “at reduced pixelation.” He came up with the name Anna Fox after looking for something that was easy to pronounce in many languages.

Mallory has described writing a seventy-five-hundred-word outline and showing it to Jennifer Joel, a literary agent at I.C.M., who is a friend of his; she encouraged him to continue. He has said that he then worked for a year, sustained by Adderall, Coca-Cola, and electronic music. Mallory told the Times that he wrote at night and on the weekends. Former colleagues who had taken note of his office absences were skeptical of this claim.

Paula Hawkins’s “The Girl on the Train” was published in January, 2015. By the summer of 2016, it had sold 4.25 million copies in the U.S. Early that September, just before the release of the film adaptation, it was No. 1 on the Times paperback best-seller list. On September 22nd and 23rd, a PDF of “The Woman in the Window,” by A. J. Finn, was e-mailed to editors in New York and London. Mallory has said that he adopted a pseudonym because he wanted publishers to assess the manuscript without “taking into account my standing in the industry.” This isn’t true, as Mallory has himself acknowledged in some interviews: Jennifer Joel told editors that the author worked at a senior level in publishing.

The editors started reading: “Her husband’s almost home. He’ll catch her this time. There isn’t a scrap of curtain, not a blade of blind, in number 212—the rust-red townhome that once housed the newlywed Motts, until recently, until they un-wed.”

The story feels transposed to New York from a more tranquil place, like North Oxford. The nights are dark; the sound of a cello, or a scream, carries. At the center of the plot are two neighboring houses, on the same side of a street, with side windows that face each other across a garden. This arrangement is easy to find in most parts of the world that aren’t Manhattan.

Mallory cannily set himself the task of popularizing the already wildly popular plot of “The Girl on the Train.” His book consists of a hundred very short chapters, and reads like a film script that has been novelized, on a deadline, under severe vocabulary restrictions: sunshine “bolts in” through a door; eyebrows “bolt into each other”; eyes “bolt open”; one character is “bolted to the sofa”; another has “strong teeth bolting from strong gums.” He then gilded his text with references to Tennyson, Nabokov, and the Pitt Rivers Museum, in Oxford. The over-all effect is a little like reading the e-mails sent by “Jake”: Anna, the narrator, feels subordinate to Mallory’s struttingly insistent voice. It’s much more a Tom Ripley novel than a Patricia Highsmith novel. Instead of Highsmith’s disorienting, erotic discovery of character, “Window” is an enactment of Ripleyan manipulation. It’s a thriller excited about getting away with writing a thriller. In a recent e-mail, Joan Schenkar, the author of “The Talented Miss Highsmith,” an acclaimed biography, described “Window” as a “novel of strategies, not psychologies.” It was, she said, “the most self-conscious thriller I’ve ever opened.”

The selling of “The Woman in the Window” was a perfectly calibrated maneuver, and caused the kind of hoopla that happens only once or twice a year in American publishing. One publisher offered hundreds of thousands of dollars in an effort to preëmpt an auction. This was rejected, and at least eight publishing imprints, including Morrow, began to bid for the North American rights. Meanwhile, offers were being made for European editions, and Fox 2000 bought the film rights.

When the bidding reached seven hundred and fifty thousand dollars, Mallory revealed his name. A former Morrow employee recalled, “I’d wondered why this person in publishing wants to be anonymous. Then: Oh, that’s why!” Mallory has said that “nobody dropped out” at that point; but many, including Little, Brown, did. When it was announced that Mallory’s employer had won the auction, one joke in New York was “The call was coming from inside the house!”

Morrow sent out a press release saying that Mallory had been “profiled in USA Today”—he hadn’t—and quoting Jennifer Brehl, the Morrow editor who had won the auction. “A. J. Finn’s voice and story were like nothing I’d ever heard before,” she said. “So creepy, sad, twisty-turny, and cunning.” She said that she had not recognized this voice as Mallory’s, and added, “He’s already known as an esteemed editor; I predict a long career as a brilliant novelist, too.” Liate Stehlik, the Morrow publisher, later wrote to booksellers, “I love it, and the only thing I thought when I was reading it was that Morrow must publish this book.”

Mallory stayed on as an editor at Morrow for another year. He set up a corporation, A. J. Finn, Inc., using an Amagansett P.O. box. A photograph of him smiling and unshaven, taken by Hope Brooks, the older of his sisters, began appearing in stories about his success.

The Mallory house in Amagansett is set back from a quiet road; trees line the driveway, joining overhead to form a tunnel. On an overcast morning just before Thanksgiving, I walked up to the house, and reached a garage whose doors were open. An S.U.V. was parked in front; two dogs leaped, barking, from its back seat. (I recalled that, according to Dan Mallory, his mother had, on separate occasions, killed two dogs by backing up over them.)

John Mallory, Dan’s father, came out of the garage, wearing a denim shirt. He is in his mid-sixties, and has a handsome, squarish face. He apologized for the pandemonium, and joked, “I’m just the lawn guy.”

I explained why I was there. “Dan does not want me commenting,” he said. “He’s my son, so I have to respect his privacy.” But his manner was friendly, and the dogs calmed down, and we stood talking for a few minutes. “He’s a wonderful young man, he truly is,” John said.

I said that I’d become interested in Dan’s accounts of cancer—the claim that he’d had a malignant tumor, and that his mother had died of cancer.

“No, no,” he said. He didn’t sound surprised or annoyed—rather, he was obliged to correct a misapprehension. When Dan was a teen-ager, he said, “his mother did have cancer. Stage V, so she was next to death. But, no, Dan didn’t have it. He’s just been an absolutely perfect son. He has his faults, like we all do, he’s just a tremendous young man.”

Did Dan have cancer later? “No, no,” John said, adding that Dan had told him that “he’d been misquoted several times, and it really bothers him when things come out that are negative about him.”

I began to describe the “Jake” e-mails. “Dan and his brother, Jake, are very close,” John said, adding that “Jake would never, ever say” Dan had fallen ill with cancer, because it wasn’t true. I wondered if John had been told that such e-mails existed, and could be explained as the work of a scurrilous third party. They can’t—Dan saw replies written to the “Jake” e-mail address, and responded to them.

When Dan wrote about living in a single-parent family when he was seventeen, was that true?

“No,” John said. “Well, in a way I guess it was, because my wife and I were separated.” They were apart for two and a half years, he said. “She made me come back,” he went on, laughing. “We had our differences. We didn’t file for divorce or anything like that.” He added, “Pam was saying, ‘I think you made a mistake. But it’s up to you.’ And then I realized I’m being an idiot.”

I asked if the separation was difficult for Dan. “Very difficult,” he said. “The family’s very closely knit and to see the dad not there on Thanksgiving or Christmas—Ian, it’s my fault. I hate to this day to think they had a Thanksgiving dinner without me.”