« Are you not the author of my elevation? » · pfp: @josephponiatowski

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Two letters from Fouché to his sister (and proof that he never enriched himself during his missions?)

Letter 1

Paris, 27 Floréal [probably in Year III, as the death of Julien, Fouché's brother, is briefly mentioned] I thank you, my dear sister, for the details you have provided me regarding our shared matters. I will send my power of attorney to Croizet so that he may sign, review, calculate, and act on my behalf as I would myself if I could be by your side. That moment is still far from us, my dear sister. I am saddened to see that our Convention session is not yet complete, that we will still have many storms to face and many factions to combat in order to consolidate the Republic on solid and compliant foundations that will bring happiness to all. Whatever happens, nothing can weaken the bonds of sincere friendship and tender affection that will bind me to you until my last breath. They are strengthened by the losses we suffer, by the need we feel to draw closer together to repair some of our misfortunes, to console ourselves by mourning together. Take care of your health, my dear sister, for your husband, for your children, and for the only brother you have left. I embrace you all on behalf of my wife and child. P.S.: As we are faced with the risk of demonetization of assignats, I believe it would be wise to keep only what is absolutely necessary for everyday use. Please send those that belong to me to the office of Citizen Duchesne, merchant at Fosse No. 13. Once you have counted them, please mark them for me. I will have Duchesne pay me back here. Those who are in a position to acquire national property have nothing to fear; the Republic will never fail in its loyalty. However, those who have only the bare necessities must carefully take the most prompt measures in these circumstances. Best regards to our relatives and friends, especially Croizet.

Letter 2

Saint-Leu, 13 Nivôse, Year V I have just received your letter, my dear sister, and I thank you for it on behalf of myself and my wife. I received a letter from your husband some time ago, and it is the one you mentioned. […] I have just learned of allegations that I have beautiful castles in Nantes. They are undoubtedly in Spain*. The wretched individuals! If I were anything like them, I would indeed have a great deal of wealth. In my position, they would have amassed an immense fortune. How could they conceive that I have sacrificed everything for my country, and that all I have left is my work and my talents? Those scoundrels no longer have the right to believe in virtue. Blessed are those who can shelter themselves from their persecutions! It was not up to them to cover the Republic in blood, and it is a miracle that you, my dear Broband, and I escaped their fury. [* remark : "castles in Spain" (des châteaux en Espagne) is a French expression referring to an unrealistic project] Tell all those who believe the tales they deliberately spread that I am giving away all the castles and everything I have bought since the Revolution to anyone who wants them; I am bequeathing everything without reservation. I confess that it is not without pride that I contemplate my situation; I would blush to be rich, but I will be rich enough from my work and all my savings. Farewell. I await your reply as soon as possible on all the items I have asked you for. I embrace you.

Source for the letters : Dominique Caillé, Joseph Fouché d’après une correspondance inédite

My analysis :

Fouché indeed sent the fruits of his plundering to the National Convention, as shown in the reports of the sessions of 11 Brumaire (“17 trunks filled with gold, silver, and silverware of all kinds taken from churches, castles, and also donations from the sans-culottes”) and 17 Brumaire (“I am sending you a fourth convoy of gold and silver worth several million”). According to his biographer Louis Madelin, he did not take advantage of his position as a représentant en mission to enrich himself personally:

“Fouché, who lived soberly, does not seem to have tried to speculate from his position. […] He showed disinterestedness: what did not go to the unfortunate should go to the nation.”

And I agree with this statement for several reasons:

Fouché's quality of life did not improve significantly after his recall to Paris in 1794. If he owned hidden money, he would not have lived in such poverty after 9 Thermidor, to the point of being forced to spin flax and fatten pigs to support his family, and he certainly would not have let his daughters Nièvre and Evelina die of illness and lack of proper medical care. Maybe he could pretend if he only had himself to take care of. But there is no shortage of evidence to show that he loved his wife and children more than anything else, and if he had the resources to do something for their health or comfort, he would have done so. His letters to Barras announcing the death of his children show his grief but also his powerlessness (“I have just lost the only child I had left to console me for the injustices and wickedness of men”)

In the first letter to his sister, he warns her that assignats will lose value and that they should only keep what is necessary to sustain themselves, and therefore dispose of the rest. However, he adds that those who can afford to buy national property have nothing to fear for the future (especially because private property is an inalienable right under the Republic). So he hasn't bought any property and does not intend to do so, precisely because he cannot afford it (In another letter, again to his sister, he expresses concern about the condition of his childhood home in Le Pellerin, which he believes has been ravaged by the Vendée wars and which he has conceded to his nieces)

In his second letter to his sister, he is genuinely outraged at being accused of owning castles. You're going to tell me that maybe he is lying or exaggerating but at the time of his writing, he is hiding in Saint-Leu with his family, forced to endure the humiliation of asking Barras for help, and the latter does not hesitate to mock him for it (“I have given him some assistance, as to an unfortunate revolutionary. To earn his money, he acts as a police officer for me, calling it devotion”) (Mémoires de Barras, vol. 3, p. 273). I don't think he would have agreed to endure all this if he had had the means to avoid it, especially since I am convinced that he always hated Barras and only approached him when it was a vital necessity.

We know that from November 1797, a year after this letter was written, Fouché began investing in military supply companies through one of his friends, an easy way to make money quickly at the time, and began to amass the fortune that was known to him during the Empire. More specifically, he was a shareholder in the Ouin company, which had “exclusive rights for one year to supply, transport, and handle food, bread, meat, and fodder for ten military divisions, including those of the brand-new army intended for the invasion of England, whose provisional command had just been entrusted to Bonaparte.” (Waresquiel)

We know that he also enriched himself with lottery money, and of course with the income from his ministry and his future titles of nobility, which he effectively bought properties with, particularly in Provence, etc.

But it was later. I still believe he never enriched himself from his pillaging in 1793 and 1794.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joseph Fouché suggesting to tax the rich : a compilation

“It was necessary to provide all at once for the fair compensation granted to the patriots who were robbed by bandits, for the needs of the brave soldiers who fought for freedom, and for the relief of their wives and children who were besieged by all the scourges of poverty. The Republic's coffers could not sustain this enormous expense for long. Action had to be taken, and it had to be swift, effective, and guaranteed. Funds could not be solicited from the poor, who did not have the necessities to live, nor from those who had only a modest fortune: both groups had paid the full price of the Revolution. They were still sacrificing their sweat and blood to wrest the immense properties of the rich from the brigands. It seems to me that it was towards the latter [the rich] that we should have turned. It was from him alone that I wanted us to ask for all the funds we might need, and all the unused beds in his luxurious homes to furnish the barracks.” - Rapport de Fouché envoyé par la Convention Nationale dans les départements de la Mayenne et de la Loire-Inférieure, imprimé par ordre de la Convention à la mi-mai 1793 (?), Écrits révolutionnaires de Fouché, p. 50

“Rich selfish men, if you are deaf to the cries of humanity, if you are insensitive to the anguish of the destitute, at least listen to the advice of your own self-interest, and ponder: […] let your excess of wealth atone for the crimes of opulence, let it put an end to the revolting inequality between your many pleasures and the excessive privations of the poor.” - Nevers, le 25 août 1793, Pièces relatives à la mission du citoyen Fouché de Nantes pour ramener le calme et faire triompher le patriotisme dans le district de Clamecy, ibid., p. 61

“The rich have in their hands a powerful way to make people love the regime of freedom: it is their surplus. If, in circumstances where citizens are tormented by all the scourges of poverty, this surplus is not used to relieve them, the Republic has the right to seize it for that purpose. This measure of public salvation is also a measure of personal safety against the just indignation of the people, who can no longer tolerate the extent of their misery.” - Nevers, le 29 août 1793, Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public, avec la correspondance officielle des représentants en mission et le registre du conseil exécutif provisoire, t. 6, p. 117

“Wealth is the most terrible weapon against the Republic when it is in the hands of its enemies: it has long caused scarcity amid abundance and kept all the weapons factories in appalling poverty, paying workers to do nothing. […] It would be unwise to leave such powerful means in their hands any longer.” - Nevers, le 6 octobre 1793, Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public, avec la correspondance officielle des représentants en mission et le registre du conseil exécutif provisoire, t. 7, p. 266

“It is with gold that they open our cities to bandits who are as cowardly as they are ferocious, and lead our brave armies under the knives of murderers. Well! We must take away from them this powerful metal, this terrible lever with which they stir up all vile and despicable passions. […] All the property of those declared suspects will be seized, and they will be left with only what is strictly necessary for themselves and their families.” - Archives Parlementaires Tome LXXVI - Du 4 Octobre 1793 au 27e jour du Premier Mois de l’An II, séance du 18 octobre 1793, Proclamation de Fouché, représentant en mission près les départements du Centre et de l'Ouest, informant les habitants de la Nièvre de son arrêté contre l'accaparement, pp. 685-687

“We are taking advantage,” he [Fouché] said, “of the sending of six members of the Nièvre Departmental Committee of Public Safety to the Revolutionary Tribunal to pass on to you 1,081 marks and 8 ounces of silver and 12,000 pounds in gold. These are tributes from the dying aristocracy, seeking to expiate its crimes.” - Mercure universel du 30 Vendémiaire an II (21 octobre 1793), p. 334

“Gold and silver have done more harm to the Republic than the iron and fire of the ferocious Austrians and cowardly English. I do not understand the complacent stupidity that allows these metals to remain in the hands of suspicious men. Can we not see that this is leaving a last hope for malice and greed? Let us demean gold and silver, let us drag these gods of monarchy through the mud, if we want to worship the god of the Republic and establish the cult of the austere virtues of liberty.” - Nevers, le 8 Brumaire an II (29 octobre 1793), Recueil des actes du Comité de salut public, avec la correspondance officielle des représentants en mission et le registre du conseil exécutif provisoire, t. 8, p. 113

“Who will come to the rescue of the Homeland and its needs, if not the rich? […] If they are patriots, you will anticipate their wishes by asking them to use their wealth for the only purpose befitting republicans, that is, for the benefit of the Republic. Thus, nothing can exempt you from promptly establishing this tax. There must be no exemptions here: every man who is above need must contribute to this extraordinary effort. […] Act accordingly, take everything that a citizen has that is unnecessary, for surplus is a clear and gratuitous violation of the rights of the people. Any man who has more than he needs cannot use, he can only abuse. Thus, by leaving him only what is strictly necessary, everything else belongs to the Republic and its unfortunate citizens. […] [The National Convention] decreed, or rather proclaimed, the great principle that the products of French territory belong to France, at the expense of the indemnity owed to the farmer. The people therefore have a guaranteed right to the fruits of their labor. They are no longer exposed to seeing the grain produced by their work enrich a few privileged tyrants and a few dozen oppressive landowners. It is therefore no longer permitted for a single owner to lay down the law to the people and to keep in his employ the hard-working men on whom his existence depends.” - Ville-Affranchie, 26 Brumaire an II (16 novembre 1793), Instruction adressée aux autorités constituées des départemens de Rhône et de Loire

“Every day we discover new treasures. At Tolozan [de Montfort]'s house, we found some of his tableware hidden in a wall.” - Commune-Affranchie, le 5 Frimaire an II (25 novembre 1793), op. cit., t.8, p. 709

“Opulence, which for so long was the exclusive preserve of vice and crime, has been restored to the people. You are its providers. The properties of the wealthy conspirators from Lyon, acquired by the Republic, are immense, and they can bring well-being and prosperity to thousands of republicans. Order this distribution promptly.” - Archives Parlementaires Tome LXXXVI - Du 13 au 30 ventôse an II, Séance du 25 Ventôse an II (15 mars 1794), Lettre des représentants Méaulle, Laporte et Fouché, en mission dans Commune-Affranchie, qui proposent des moyens pour secourir les infortunés que l'aristocratie a fait dans Lyon, p. 495

#joseph fouché#frev#french revolution#“ if you are deaf to the cries of humanity if you are insensitive to the anguish of the destitute ”#DAAAAAMN

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

very cringepilled napoleonic era x warriors designs

edit: i redesigned josephine cuz im extremely indecisive... sorry

#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars#joachim murat#jean andoche junot#josephine de beauharnais#napoleon bonaparte#I have made names for like almost all of them#we live for warrior cat aus

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

I still think this is so fucking funny

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharing this bit of a dialogue I imagined between Napoleon and Carnot when the latter resigned from his position of Minister of War.

I came up with the whole dialogue while listening to music, but since I didn't write it down, I eventually forgot it and the following lines are all I remember...

CARNOT. [...] Then, I resign!

NAPOLEON. You can't resign. You are my minister: you belong to me.

CARNOT. I belong to no one but France itself, First Consul.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

General Jean Andoche Junot ,Duke of Abrantes writing a letter for Napoléon Bonaparte at the siege of Toulon in December 1793.

#atleast this version has the mustache#an UGLY mustache but.. we dont judge /j#napoleon bonaparte#jean andoche junot

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

I wish I could make educational posts but I feel like I'll get cancelled for existing and not being good enough and not being a "real historian"

◆◈◆

(Do what you want and don't give AF, as long as you're not spreading misinfo you should be fine)

#literally how i feel#theyre going to pelt me with rocks#im about to get pelted with rocks#ohhh im getting pelted with rocks#ouchieee owwww

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi!! I don't know if you are open to more questions about Fouché, but I am curious and would like your opinion/knowledge: Did Fouché have any consistent ideology?? Or was staying in power(?) his consistent motivation

This is an extremely interesting and complex question that I've been asking myself a lot!

Let me just get one thing straight first: I don't give any credit to the dubious articles and biographical essays that portray Fouché as an empty shell with no values or principles whatsoever and who just betrays everything and everyone because why not. It's an extremely romanticized vision of Fouché that would fit perfectly into a Balzac novel (by the way, you should read Une ténébreuse affaire, it's my favorite historical novel!) but not into a serious thesis based on historical sources.

In my opinion, Fouché is a republican and has remained so pretty consistently throughout his life. Yes, he had opportunistic attitudes and yes, he sometimes (often) betrayed his allies and friends, we'll come back to that later, but it doesn't mean that he was a complete cynic who didn't believe in anything. I don't know exactly when it started, but my guess is that he radicalized and embraced republicanism during 1792. This may seem late, but it's worth remembering that even Robespierre and Saint-Just were in favour of constitutional monarchy in the early years, until the disappointments and betrayals of Louis XVI finally convinced them that this regime would not be sustainable and that the king and the Revolution could not both be saved.

Oh and also, I'm going to put an end to an extremely widespread myth by quoting from Stefan Zweig's disastrous biography:

“Fouché's position on January 15 was still very clear. His adherence to the Girondins and the wishes of his electors, who were essentially moderates, obliged him to ask for the King's pardon. He questioned his friends, especially Condorcet, and found that they were all prepared to avoid a measure as irrevocable as execution. And, as the majority were, on principle, against the death penalty, Fouché naturally rallied to their opinion; just the day before, on the evening of January 15, he read to a friend the speech he intended to give on the occasion, in order to justify the decision to pardon. When you sit on the benches of the moderates, you are bound to moderation, and as long as the majority rejects any extremity, Joseph Fouché, whose convictions carry little weight, rejects them too.”

Imma hold your hand when I say this : everything you've just read is wrong.

No, Fouché did not spectacularly and cowardly betray the Girondins overnight by voting for the King's death when he had promised the opposite, and no, his position “on January 15” was not in favor of the King's pardon. In fact, we know that he already wanted the king dead since at least January 7, if not much earlier, since the 7th was the day his speech Réflexions de Joseph Fouché (de Nantes), sur le jugement de Louis Capet was added to the appendices of that day's session of the National Convention. I've translated it and published it as a whole here, but I'll give you a few extracts to show you just how clear and unambiguous his position is:

“Citizens, I did not expect to express, from this rostrum, any opinion against the tyrant other than his death warrant. By what event, by what invisible hand, have we been led to put in issue what a general conscience, an intimate feeling, the good sense of the people at last, had decided when he sent us? We seem to be frightened by the courage with which we abolished royalty: we are faltering before the shadow of a king, and the first lights of republican virtue are ready to be extinguished in our hands.” (Archives Parlementaires de 1787 à 1860, première série (1787 à 1799), Convention Nationale. Séance de la Convention Nationale du lundi 7 janvier 1793 au matin, Annexe n°54, p. 405-406)

It is therefore reasonable to assume that on January 15, more than a week after this speech was written, printed and brought to the attention of the National Convention, his Girondin colleagues were already well aware of his position in favor of the King's death.

Moreover, this story was told by a single witness, Pierre Daunou, who worked with Fouché on the Comité d'Instruction Publique (Jean Savant even goes so far as to imagine a rather unlikely dialogue between the two), which was later reported by Auguste-Louis Taillandier and repeated by Maurice Gaillard in a clumsy attempt to justify Fouché's vote (at a much later date, when he was already Duke of Otranto).

Secondly, Fouché was a radical republican, who believed more in a Revolution through equality than liberty (so in favor of price controls and taxing the rich, to put it succinctly), close to the ideology of the Hébertistes. In fact, he was a friend of Hébert and especially Chaumette, who supported Fouché in the most obvious part of his republicanism: his atheism and fight against the influence of the clergy, particularly in the field of education. Fouché's atheism also inspired some people to write a great deal of nonsense: in 1816, Antoine Sérieys sought to discredit the Duke of Otranto in the context of the royal family's return to power and published Fouché (de Nantes): Sa vie privée, politique et morale, depuis son entrée à la Convention jusqu'à ce jour, in which he doesn't hesitate to assert that Fouché's mother, with whom he had an excellent relationship, lamented “having produced such a being” when faced with his alleged “precocious impiety” (it's giving Disney villain energy lol).

In fact, to better understand Fouché's ideology, we need to read his own writings, starting with his Réflexions sur l'instruction publique. As we know, he had a long career as a pupil and then as a teacher at the Oratoire institution. His position on the Comité d'Instruction Publique and his deep concern for the education of children, but also of citizens in general, show that he has kept this teaching mindset. This is a very important text in which he stresses that the education of children must be taken away from priests and entrusted to lay people. He considers religion to be an obstacle that blinds future citizens of the Republic, lowering them into the darkness of the fear of God and preventing them from seeing “the truth” and cultivating their reason and reflection. For him, the influence of the clergy was a danger to the Republic that had to be annihilated as a matter of urgency, hence the numerous acts of violence committed against priests and churches.

Furthermore, he was accused of having personally enriched himself during these plunders (notably by Barras in his Mémoires, who claims to have seen Fouché's wife leaving Ville-Affranchie in a carriage filled with goldish stuff), which Louis Madelin refutes:

“Fouché, who lived soberly, does not seem to have tried to speculate from his position. […] He showed disinterestedness: what did not go to the unfortunate should go to the nation.”

Let's fast-forward to the Consulate and Empire. We know that Fouché has a vested interest in supporting Napoléon's rise to power as, if the royal family returns, the death sentence awaits the regicides who voted for Louis XVI's death. We also know very well that Fouché was never a fervent Bonapartist, and that Napoleon only kept him around out of necessity. But did Fouché help the Republicans, did he protect them, was he useful to them?

This answer is getting far too long I am so sorry Anon, I'm going to proceed in the form of a list to make it more digest to read:

Fouché closed the Club du Manège, the last Jacobin gathering still active in Paris in 1799. A few days before, he summoned Bernadotte, of whom he was a close friend, to convince him not to attend their next meeting:

“Imbecile! where are you going to, and what do you want to do? It would have been all right back in [17]93, when there was everything to gain by unmaking and remaking. But, what we wanted then, we possess today. And as we have got what we wanted, and should only lose by going on, why do so? [...] Do as you please, but just remember this that after tomorrow, when I shall have something to say to your club, if I find you at the head of it, your own shall tumble off your shoulders. I give you my word of honour, and I shall keep it.” (Le comte de Ségur, Histoire et Mémoires, Tome 3, p. 417)

On August 14, 1799, he permanently dissolved the club, and Bernadotte wisely stayed at home.

This story is recounted by the Comte de Ségur, who claims that Fouché told it to him many years after the event. Except that Bernadotte, though openly Jacobin, was not involved in the activities of the Club du Manège, it was definitely not “his club” and so it wouldn't make sense for Fouché to tell him all this (an immense thank you to my best friend @theblackrook for finding this extract and contextualizing it for me). In any case, the fact that he took part in this operation can be seen as a huge betrayal of his former allies and of his own republican principles. And to make things worse, according to Waresquiel, after this operation, a former Jacobin spotted Fouché in the street and threatened to ���walk his head through the streets of Paris”, to which Fouché replied: “Let me take a look in the mirror to get an idea of the effect my head will have when you place it on the iron of a pike”. Yeah… great vibe.

But three months later, Fouché protected these same Jacobins from the proscription lists: “The day after the coup d'état [of 18 Brumaire], Sieyès requested the deportation to Guyana of some sixty Jacobins, including some former deputies excluded from the Councils. Fouché complied, but did his utmost to oppose Sieyès underhandedly, until he obtained from Bonaparte, with the help of Cambacérès, the repeal of the proscription decree a few days later” (Waresquiel, “Chap. 15 : Brumaire : dans les coulisses d’un coup d’Etat”, Fouché : les silences de la pieuvre)

Fouché was also convinced of the Jacobins' innocence and protected them when they were accused of being responsible for the Rue Saint-Nicaise bomb attack: he knows full well that they do not have sufficient means to carry out an action of such magnitude, while the royalists are numerous, infiltrated into Paris and financed by foreign coalitions. The republicans are accused by Bonaparte, by his brothers and sisters, by the Prefect of Police, by the Senate, everyone is suddenly out to get them, and Fouché is quickly also accused. When Jean Rossignol was arrested, his first instinct was to immediately ask Fouché for help. The latter gave him “orders and advice”, which didn't prevent him from being deported (@nesiacha shows Rossignol's letters, which are extremely moving, in this post). He did, however, manage to help a few of them emigrate, including Barère, and arrested a handful to please Bonaparte, but released them as soon as his back was turned, and especially as soon as the real culprits were found.

It would seem, however, that he made all these efforts more out of a search for truth and justice than to protect his “old friends”, but the fact that they immediately turned to him for assistance shows that he was still seen as a figure with both the desire and the ability to help them.

Of course, there's also the case of the Walcheren expedition, one of Fouché's greatest radiance boost, in the summer of 1809 (he had just got the Ministry of Internal Affairs ad interim in addition to the Ministry of Police, which made him, in Napoleon's absence fighting in Wagram, the most powerful man in France). A fleet of 30,000 English troops headed for Anvers, which was French territory at the time. Opposing himself to the ministers Cambacérès and Clarke, Fouché wanted to intervene immediately, without waiting for Napoleon's orders. He had the support of two men: the Minister of the Marine and Marshal Bernadotte, whom he put in command despite the fact that the Emperor already disliked him. Waresquiel points out that, in order to raise troops for the defense of the coast, Fouché invoked the “patriotism of the citizens”, that he chose officers from “the well-off bourgeoisie” (the same social class that had a majority in the Convention), and that on October 4, after successfully raising 200,000 men, he reportedly wrote to Murat: “The success of these raisings proves that the Revolution is not dead and that Napoleon's armies are not all the forces of the nation”, so the Naional Guard was definitely not an innocuous choice. Clarke, himself an aristocrat, calls him “a dirty Jacobin from '93”.

It's worth noting that Fouché had friendships, sometimes opportunistic and sometimes sincere, with members of the nobility, but I don't think this had the slightest influence on his political ideas.

In 1815, after Napoleon's abdication, Fouché headed the provisional government, where he had no intention of legitimizing Napoleon II's reign (acts were rendered “in the name of the French people”, not in the name of the young heir). On July 5, while in Neuilly with the Duke of Wellington to negotiate the terms of a return to the monarchy in the person of Louis XVIII, Fouché continued tirelessly to try to save the achievements of the Republic, starting with the tricolor flag, seen by Wellington as the flag of rallying to Napoleon. While Talleyrand immediately accepts this condition, probably reluctantly, Fouché refuses, making the flag “a non-negotiable condition for the return of the King”.

But Fouché's admission to the King's ministry remains, for me, the most unforgivable of his betrayals. I have no excuses for him, but I do have theories to try and understand what led him to make such a decision.

There has been an observable evolution since he obtained the title of Duke of Otranto, but even more so since he further legitimized his entry into the aristocracy by marrying his second wife, Ernestine de Castellane-Majastre, in the same year of 1815. Fouché, who was known for not spending much, offered her sumptuous objects when he courted her, and decorated his carriages with coats of arms that mixed his own and those of his wife (A.E. Moulin, Le grand amour de Fouché : Ernestine de Castellane). Presumably, this new status and the wealth that came with it went to his head (his income as Count of the Empire and Duke, Minister of Police and Senator of Aix alone earned him more than 260,000 francs, not counting the money he earned from church assets, gambling and his private properties). In Aix, between 1810 and 1811, the municipal archives showed me that he presented himself only as “Monseigneur Joseph, Duke of Otranto”, and his family name disappeared. Perhaps he thought that time had done its work and that the French nobility, but above all the royal family, would forget or forgive his crimes now that he was “one of them”.

Beyond betraying his fellows, he betrayed himself for a Ministry post he was tired of and did not even want in the first place, and that cost him everything he had.

I hope I answered your question :)

#joseph fouché#napoleonic era#frev#Beautiful Answer#There's a lot of nuance in history#Everybody sees things their own way#Its ok Fouché i still love you ❤️#(not as much as mathilde does though)#(that would be impossible)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sure Napoleon, he's being "Tsundere" .. You'll get him soon I'm sure.

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not-So-Father of the Year: Bernadotte in 1789

In the summer of 1789, amid the early days of the French Revolution, Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte—then a 26-year-old sergeant in the Royal-La-Marine regiment—appears to have fathered a child in Grenoble, France.

On August 4, 1789, a baby girl named Olympe-Louise-Catherine Lamour was born to Cathérine Josèphe Lamour, a 17-year-old seamstress and daughter of a grocer. The baptismal certificate, recorded at Saint-Louis Church on August 5, unambiguously names "Bernardotte, sergeant au régiment Royal-la-Marine" as the father. It reads:

"On August 5, 1789, I baptized Olympe-Louise-Catherine, born yesterday, the natural daughter of Cathérine Lamour and of one named Bernardotte, sergeant in the Royal-la-Marine regiment; declaration received from Mr. Girard, notary in Grenoble. The godfather was Louis Rolland, music master; the godmother, Mademoiselle Cathérine Jacob. The witnesses have signed. — Rolland."

More tellingly, a notarial declaration dated May 8, 1789, confirms that Bernadotte had already acknowledged paternity three months before the child’s birth.

Lamour’s youth and social position—along with Bernadotte’s military movements—make it unlikely the relationship was enduring or particularly significant.

Tragically, the infant Olympe-Louise was placed in a local orphanage shortly after birth and died less than a month later, on September 2, 1789. Her mother, Catherine Lamour, lived until October 27, 1808, dying at the age of 37 after an illness that lasted two months. She is recorded as a glove seamstress ("couseuse de gants") at the time of her death.

The primary documents��baptismal, hospital, and notarial records—offer a sobering and factual account of what was likely a short-lived liaison in Bernadotte’s pre-imperial life. Though seldom mentioned in biographies, this moment stands as a poignant and very human footnote in the life of a man who would later become King Charles XIV John of Sweden and Norway.

Source : Wikitree + Fredrik Ulrik Wrangels Från Jean Bernadottes ungdom published in 1889 ALSO @major-knighton HE WAS THE ONE WHO TOLD ME ABOUT THE DAUGHTER SO TECHNICALLY HE IS A SOURCE AS WELL

#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#jean baptiste bernadotte#bernadotte#murat.txt#my analysis#my writing

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Call me cringe but I think Fabre would be rocking with old 2017 animation meme songs

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

thank yooouu @mathildeaquisexta and @aedislumen !! Ohhh look at you two gooo.. what goals /j

I really don't know who to tag so um sure @ishido-enjoyer this is what you get for tagging me in the movie one /j

tag game!!

Do this picrew of yourself, and tell me one thing you did today!

I got to say hi to all my friends and catch up on stuff after not having my phone for a week :]

@mintymooshroom @onyxofc @pandagobrr @amethysttable @theembergazer @silverdragon889 @sylki221b-of-the-shire @saltinegam @sleepywillowo0o

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

We know Fabre was executed on charges of plotting with enemy nations and being involved in the Compagnie des Indes case.

And for being corrupted, basically. But he denied everything.

How much responsibility did he really bear in all this? What was he actually guilty of?

Alright, let me start by saying right off the bat that I love you and you are my bestest friend, BUT ALSO — @anotherhumaninthisworld and @edgysaintjust HAVE BOTH made a REALLY really like SUPER amazing and good and spectacular post explaining everything.

I'm so serious PLEASE go read it, this post is bound to be just as long as both of theirs combined.

I will more or less be regurgitating what they so eloquently laid out — just in a more "feeding a baby bird" manner of speaking.

On top of this, I'd also like to gently remind everyone that most of my historical brainpower goes into obsessing over the personalities and feelings of these historical figures — so when it comes to the exact logistics of various executions and political events and all that… I’m just a tiny bit fuzzier. But hey, you can’t win 'em all, right?

ANYWAYS THE POST :

Context is very important so we'll touch on that first and foremost. If you're already well versed in all of this hokey-pokey I advise you to scroll down a bit to the read more.

The French East India Company, founded under Louis XIV, was a major trading monopoly with colonial and financial interests. By the time of the Revolution, it had become heavily corrupt and bankrupt.

In 1793, all joint-stock companies were banned by decree, and the company was to be liquidated.

A finance commission was created to oversee the liquidation: members included Fabre d'Églantine, François Chabot, Joseph Delaunay, Julien de Toulouse, Ramel, and Cambon.

Only the first four of them — Fabre, Chabot, Delaunay, and Julien — became involved in the scandal.

So What Happened?

Delaunay, Chabot, and Julien devised a plan: have the East India Company liquidate itself (which allowed for embezzlement and secrecy), in exchange for bribes. Fabre, initially, opposed this idea and proposed government-led liquidation, backed by Robespierre.

Delaunay attempted to bribe Fabre via Chabot (offering a WHOPPING 100,000 livres!!) — Fabre still ended up rejecting the decree draft and reinstated his amendments supporting government control.

Enter THE TRAP ™ !!

Chabot returned later with a supposed "clean" copy, which Fabre, half-asleep, signed without reviewing, assuming it was the version with his corrections.

Delaunay then altered the signed decree, making it look like Fabre had authored and endorsed a version favorable to the company. This decree was submitted to the Convention, and none of the fraud was noticed immediately.

Then We Get The Unraveling ™

Chabot, who was clearly having second thoughts, fearing exposure (and after being accused of moderation by the Jacobins), bursts into Robespierre's room and confesses the entire thing to him, using the excuse that he had only joined the scheme to expose it.

He went to the Committee of General Security, turned over the 100,000 livres (yes, the same money Fabre never actually touched), and spilled the whole scheme — pinning most of it on Delaunay, Julien, and of course, Fabre.

Now, was that a betrayal? Absolutely. Was it the truth? That's the part we're not so sure about.

The committee arrested the main players, including Fabre, and started investigating. And this is where things get even messier.

Fabre was genuinely surprised when shown the decree. He remembered the one Chabot gave him didn't have any of those suspicious cross-outs. Cambon even backed him up on this — he had seen Fabre's real corrections earlier, and they weren't the ones on the final document.

BUT: by this point, Fabre's name was all over the version that had been submitted. It had his signature. It looked like he had written the thing. It didn't help that Delaunay had literally copied the other signatures under his, and edited it to make it look finalized.

And Fabre, poor guy, never even got to see the original documents during his trial. When he asked? Denied!! 🙃

SO WHAT WAS FABRE ACTUALLY GUILTY OF??

okay, one, damn, calm down! Oy gevalt I'm getting there!! In any case, this is where things get very hazy — and where historians have been arguing for well over a century.

There are two (yes TWO!!!) main schools of thought:

The "He Did It" Camp (Albert Mathiez et al) This group sees Fabre as genuinely corrupt. They argue he accepted the bribe, helped manipulate the decree in favor of the East India Company, and basically sold out his revolutionary principles for cash. This view paints Fabre as an opportunist who finally got caught.

The "He Was Framed" Camp (Henri Houben, Michel Eude, and most modern biographers) This camp argues that Fabre was not guilty of corruption, and that he was manipulated and then scapegoated. According to this view, he never took the bribe, tried to prevent the fraud, and was misled into signing a falsified version of the decree. When things blew up, he became a convenient fall guy — partly due to his position, and very largely due to his reputation.

Which brings us to a key point:

Fabre's Reputation

I imagine that when most of you picture this 'first prize'–winning poet, you don't exactly envision an angelic cherub strumming a tiny lute. And would you have it — not many people during his time did, either.

Fabre had what we might call… a reputation. He was a dramatist by profession, known for scandals, affairs, and some shady side gigs (like the iNfAmOuS shoe supply controversy), basically the works. He was close to Danton and had long been seen as too flamboyant and maybe a little too slippery for comfort.

So when his name popped up in a scandal, people were more than ready to believe the worst as he naturally had enemies. He was already associated with the "Indulgents," and in a political climate as volatile as the year they were in, that was more than enough.

It's actually heartbreaking: he may have been undone more by who he was perceived to be than by anything he definitively did.

Also worth noting: he wasn't just executed for the East India stuff. The charges thrown at him also included vague stuff like "plotting with enemy nations" and being part of a conspiracy. It was the same broad, paranoia-fueled wave of accusations that he himself had thrown at Hérault. But in the end, it didn't help: it just added more fuel to the fire, and all those names got pulled into the same whirlwind.. Poor Hérault.

What Do I Think?

I think Fabre was careless, possibly just a TAD naïve, and almost definitely not the main conspirator.

He didn't handle the situation well — that much is clear. Signing a document without checking it was a massive blunder. But the evidence we do have suggests that:

he opposed the company-friendly plan from the start,

he didn't accept the bribe,

and the version of the decree he saw and corrected was not the one that went to the Convention.

Add in the fact that he was denied the chance to even see the document he was accused over during his trial? That smells a lot more like political expediency than due process.. Ahem ahem coughh coughhhh...

So to answer your original question:

How much responsibility did he really bear in all this?

Not none — but not nearly as much as he was punished for. He wasn't blameless, but I don't believe he was the architect of the scheme either.

What was he actually guilty of?

At most? Being reckless, being too trusting, and — as always — being in the exact wrong place at the wrong time. And, of course, being Fabre d’Églantine. That alone was sometimes enough.

#sorry this is so unserious#I'm literally just tldring this shit except it might be longer than what i am tldring#murat.txt#frev#fabre d'eglantine#my writing#my analysis

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!

Here Fouché is often drawn having red hair and blue eyes. Are there any official sources on his physical appearance that confirm he really had these features?

Hello to you too! Thank you so much for this question and for giving me another opportunity to yap about my favourite man. ♥

Indeed, this description has become predominant and even inspired the most exquisite Fouché fanarts I know, starting with michel-feuilly's masterpieces, which are my personal favorites and deserve more visibility.

As for the historical sources, some people in the frevblr and napoblr pointed out the existence of this portrait (third image, with Carnot's) but no author or date is associated with it and as far as I know, it's nowhere to be found other than in this article, so I'd rather not state with certainty that Fouché is the one depicted here.

In fact, sources that describe Fouché as a redhead are… quite rare, actually.

First of all, there are Barras' Mémoires, and I believe it's here that this description of red hair was first noticed by the frev/napoleonic era fandom. It should be noted that they were published after his death, and we can't even be sure that it was actually him who even wrote them. And even if he did, we shouldn't necessarily trust everything he says, because, well… it's Barras. Anyway, when it comes to Fouché, he describes :

“[Fouché's] tiny red-rimmed eyes, which had given him for me the nickname of the Red Partridge, [which] were even redder, smaller and veiled than usual”

But he doesn't specify whether his eyes are blue or not. Further on, he mentions :

“[...] his ugly wife called the ‘virtuous woman’, her child red-haired and ugly like them”

The child to whom he refers here is not Nièvre, as I have read in some posts, but Evelina Fouché, his second daughter, born in January 1795 and deceased in July 1796, for Nièvre was no longer alive by the time of the Thermidorian Convention/early Directory, and it is at this point in his life that Fouché is described.

Of his many biographers, only Stefan Zweig describes him with “russet eyebrows”, and for many reasons, including his refusal to substantiate his biographies with a single damn source and his lack of mastery of the historical method, I don't give this author any credit.

And then… that's it. Or, well, I've found other physical descriptions of Fouché, but he appears more as… blondish?

For example, his biographer Emmanuel de Waresquiel pictures Fouché as follows: “He has a glabrous face half eaten with freckles, very pale, of a waxy and livid pallor, almost diaphanous, down to the hair of a bland blond, bleached as are those of albinos.” (Fouché, les silences de la pieuvre, Chapter 4: “Vous tremblez devant l'ombre d'un roi”)

Maxime du Camp, too young to have seen Fouché with his own eyes, describes him in the dusk of his life, in 1820 during his exile in Prague in Souvenirs d'un demi-siècle :

“Emaciated, wrapped in a blanket, with his yellow hair, his white eyebrows, his weak albino eyes, he looked like a ghost ready to disappear.”

Lastly, there's a description in the Mémoires of Mathieu Molé, who knew him during his lifetime and even met him at several occasions :

“His whole person reflects the passions that agitated his life; his height is tall, his limbs spindly, his fiber dry, his movements very swift, his physiognomy fiery, his features thin, his eyes scratched and piercing, his hair those of an albino; something fierce, elegant and agile makes him look like a panther”.

Then there's the problem of Fouché's pictorial representations. Most of those were probably not made during his lifetime. His two best-known paintings are currently part of the collections of the Versailles Castle (where they are not on display, much to my regret. And the curators refused to show them to me when I was begging on my knees. Rude people). The first, Claude Dubufe's painting of Fouché in 1809 dressed in his Duke of Otranto clothes, was allegedly commissioned by Fouché's children after his death, but we don't even know its date, and according to an article by the art historian Jérémie Benoît, it was painted by another artist, René Berthon, then recuperated and extensively retouched: “the whole background was repainted, hiding a drapery and some furniture”. Once again, I can't prove anything, even if it's true that this black background, as if something were hidden inside, gives this painting a rather strange mystery. We don't know either who painted this one, and for this one, we suspect the portraitist Marie-Thérèse de Noireterre, who even painted two representations of him.

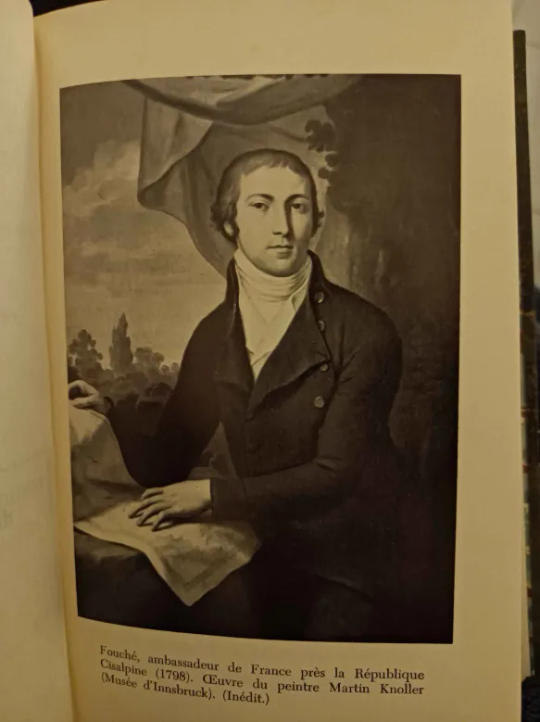

Then there's my favorite of all: this engraving in Henri Buisson's biography of Fouché, which is said to have been made in 1798 and bears a striking resemblance to all the descriptions above, not to mention the fact that he looks like he has blond (or red!) hair :

Aaaaand, that's all I know about it. In conclusion, I can't assert anything with certainty when it comes to Chéché's hair and eyes colour. I am sorry if this long answer is a disappointment. :(

But I can give you my theory : maybe Barras doesn't describe Fouché as a redhead because he has red hair, but for more philosophical, more symbolic reasons, linked to the way in which the figure of the redhead was represented in art, literature and overall the public imagination :

“Certainly, throughout the Middle Ages, to be ginger was still, as in Antiquity, to be cruel, bloody, ugly, inferior or ridiculous; but over time it became primarily to be false, cunning, a liar, a deceiver, disloyal, perfidious or a renegade. To the traitors and felons of literature and iconography, already mentioned, are added the discredited gingers of didactic works, encyclopedias, books on manners and, above all, proverbs.” (Michel Pastoureau, Une Histoire Symbolique du Moyen-Âge)

This vision of things was particularly true in ancient and medieval times, but it's not implausible to suppose that it continued to exist in people's thoughts as well as in art (Cabanel's 1847 painting The Fallen Angel depicts Lucifer with red hair).

But again, this is just one of my theories, and unfortunately I can't read Barras' mind to verify the veracity of my hypotheses.

Still, I think it would be interesting to discuss it together, and ask if any of you have found other physical descriptions of Fouché that would help us shed more light on this mystery!

#joseph fouché#napoleonic era#fouche#frev#his hair only becomes red when he is thinking of murder#I never realized he was actually blonde#I thought he was just so evil his hair became white all the time /j#< he would've saved a lot of money on powder regardless#great post!#bird fouche

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

THAT TREND but it's Désirée Clary & Bernadotte propaganda

With a Napoléon cameo

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Mme Murat avait désiré long-temps, avoir deux Anglaises auprès de ses enfans. »

Madame Murat had long wished to have two Englishwomen at her children’s side. The eldest, Achille, was about four years old; the second, Lætitia, was two; and the third was only nine months old. Later, a daughter was born, who was named Louise. Mme Pulsdorf, my fellow countrywoman, and I were received with great kindness. The eldest of the little boys was entrusted to my care. We spent all our time in the apartments assigned to us; we rarely interacted with other staff in the household. The Italian and French servants showed us little sympathy and continually ganged up on us. Even those whose position ought to have placed them above such pettiness did not hesitate to organize little intrigues to discredit us in the eyes of our excellent mistress, because, being English, we belonged to the enemy’s side. But although their conduct caused us great distress, we nonetheless showed zeal in carrying out our duties, and we had the satisfaction of hearing Madame Murat express her desire to have more English people in her service. I rarely had the opportunity to see Bonaparte. The visits he paid to his sister were so secret that few in the household knew when he was there. However, he did learn that his sister had two Englishwomen in her service; and when he had resolved to attempt a landing in England, he wanted us to be sent away, saying that women could, like men, maintain correspondences. But the children were so attached to us that their mother tried to evade this order. For three months, we were not allowed to go to the palace or to appear in public.

Note: The source is a French translation of an English text which I then proceeded to translate back into English! How great! In any case, I will continue to analyze this source and make more posts about it, stay tuned ^_^

My Thoughts ↴

Caroline is described as having received the English governesses "with great kindness" and expressed a desire for more English staff despite England being at war with France at the time. This suggests she was more focused on practical and emotional needs (e.g. care for her children) than on ideological loyalty to the nation.

When Napoleon ordered the dismissal of the Englishwomen due to fears of espionage, Caroline tried to defy or at least delay the order, because her children were attached to their governesses. This shows that she was independent-minded and willing to (quietly) resist her brother's orders and that she most likely prioritized the well-being and stability of her children over that obedience.

Though the fact that the Englishwomen were mistreated by other servants but remained in Caroline's good graces suggests she may have been unaware or unable (or perhaps unwilling) to fully intervene in the pettiness within her staff.

But by embracing English staff, Caroline implicitly signals that ideology (in this case, loyalty to France in a war against England) was not her dominant guiding principle in domestic affairs. Instead, she prioritized practical considerations: childcare, household management, and her children's happiness. (.. Isn't that a repeat of what I just said ??? take a shot every time i repeat what I just said guys !!)

Murat himself is not mentioned directly in this passage by a woman who presumably spent a LOT of time around his children, which probably indicates the obvious; that Murat played little a role in household management or child-rearing and that he left the domestic sphere to Caroline, or even more likely, that he was occupied with his military/political duties. (Because as we know, Murat was very attached to his children, so I doubt he'd be at home and just not care about them and their upbringing.)

On a broader historical level, Caroline's choices reflect what is most likely wider patterns among the European aristocracy during times of war. Aristocratic families often employed foreign servants, tutors, and governesses regardless of national tensions, because education, language skills, and cultural refinement were highly valued. While nationalism existed, the aristocracy was often insulated from its harsher effects. The presence of English staff in a French household highlights how practical concerns often took precedence over political alignment.

#murat.txt#caroline murat#caroline bonaparte#joachim murat#<- just a lil#napoleonic wars#napoleonic era#my analysis#my writing

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joachim Murat, by Pierre Charles Cior, around 1808.

(I’ve actually never seen this one before. It was posted on Facebook from an unnamed auction listing.)

89 notes

·

View notes