Note

Hello Mister, I hope this ask find you in good health!

I am a fan of your work, the Khuzdul lessons, the library, the website and the translations.

I am trying to learn Khuzdul, for mi love to the dwarrow culture and seeking some peace of mind on this modern life. I watch your lessons on YouTube, and then I take a look on the website searching for the pronouns (something to start) and notice that some are diferent.

The videos were made 10 years ago (the first), and, like is said, that the Neo-Khuzdul is something variable (there are more forms) and something in development, is correct the assumption that the version of the pronouns in the website is the current version?

Beforehand, thank you for take the time to read this ask.🙇

Well met, friend — and thank you for your kind words! I’m delighted to hear that the lessons and resources have been helpful.

🪓 On the Old YouTube Lessons

Yes — you’re absolutely right — the YouTube lessons are over a decade old now (how time flies!). They were an attempt at structuring Neo-Khuzdul for beginners, and while they still cover useful ground, they no longer reflect the most up-to-date approach.

Since then, I’ve developed a completely new Beginner Lesson Plan, currently consisting of 9 lessons, which I’ve taught live four times now via Discord. These newer lessons are far more structured, cover refined grammar, and reflect the evolution of the system after many years of feedback, questions, and… well, hard-won grammatical wrangling.

❓Why aren’t those newer lessons on YouTube?

Good question. Two reasons, really:

Privacy — These lessons were taught live with students, and recording would’ve meant capturing their voices and questions. Not everyone is comfortable with that, especially in a language-learning setting.

YouTube Demonetisation — YouTube unexpectedly removed monetisation from my channel last year, citing "copyright" issues — despite the fact that I’d already marked every video containing movie clips as non-monetised from their upload date. Hence I’ve disputed this, but with no success thus far. While the income was never much, it did help a little with the costs of running the site, server, and related materials.

As a result, I’ve stopped uploading to YouTube — partly out of principle, and partly because I’m considering other options. The most likely path forward is hosting future recordings via Patreon, so that supporters can access updated materials and recorded lessons directly.

And yes — if interest is strong enough, I might schedule another live session later this year (or early next). Feel free to email me at [email protected] if you'd like to be added to the “interested in future lessons” list.

📚 On the Pronoun Differences You Noticed

Great eye! Yes, there are a few changes between the YouTube-era materials and the more recent versions on the website.

One major example: in older lessons, you’ll often find pronouns written separately from the noun they modify, especially for clarity in beginner examples. For example, instead of writing a full compound, I'd break it up to show the parts more visibly.

Since then, I’ve shifted away from that approach. In Neo-Khuzdul, proper compound formation matters — and pronouns are often suffixes rather than separate words. So, the website version is the most accurate and current.

✅ In short: when in doubt, trust the website version — or feel free to reach out via Tumblr or Discord. I’m always happy to clarify!

Thank you again for reaching out — and may your study of the Dwarrow-tongue bring you new insights!

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Of Fans and Scholars"

🎓 A Note Before We Begin

This post was sparked by a recent conversation — a friendly and supportive exchange with a Tolkien-studies academic I’m collaborating with on a project (whom I won’t name, as none of this is meant personally). During our chat, they mentioned something in passing: “but that’s just fan postulating.” It wasn’t directed at me, nor was it meant unkindly. Yet it stayed with me — not because it was harsh, but because it reminded me how easily the academic world can, often unintentionally, slip into gatekeeping. And how quickly the word fan can be used to diminish rather than describe.

And as the queue is finally more manageable than it has been in many months (dare I say, years), I thought to write a few lines on the matter — some musings, not in bitterness, but in reflection. And with hope for how the line between fan and academic might one day blur in all the right ways.

🎒 What’s in a Title?

I don’t have a degree in Tolkien studies. I didn’t walk the academic path. Life steered me elsewhere — those options were never really on the menu — and frankly, I have no regrets.

I’ve spent over thirty years studying the Dwarves of Arda in every conceivable way. Not broadly across the Legendarium, but deeply — obsessively — into one corner of it. And as someone who collects trivia that never leaves their brain, I dare say I know a thing or two about these bearded creatures.

So when I hear the word fan, I try to embrace it, not shy away. Because I am a fan — a fan who writes, cross-references, reconstructs, teaches, and shares. A fan who aims to build bridges between what Tolkien wrote and what others dream in its wake.

But it’s that little word just — just a fan — that more academics might reflect on. The word fan can enrich, but just can so easily be used to dismiss.

🎓 Why Some Academics Seemingly Look Down on Fandom Contributions

To be clear, most academics are not gatekeepers. Many are kind, generous, and open to dialogue. But patterns do exist — and they’re worth naming.

🏛 Professional Conditioning Academia teaches scholars to value peer-reviewed, institutionally sanctioned work. If it’s not published in a journal or presented at a conference, it’s seen as less serious — even when it’s more insightful than some published work.

🏆 Protecting Prestige Tolkien studies is a small field. Some scholars carve careers out of narrow areas of expertise. When a fan without credentials publishes a piece that reaches more people — or offers a fresh insight — it can feel threatening. Not necessarily intellectually, but socially. So they lean on tone and credentials as shields.

📐 Assumptions About Method There’s a common belief that fans are emotional, subjective, or casual in their engagement. While some are, many aren’t. In fact, I’ve found fan essays are often more rigorous and linguistically aware than their academic counterparts. But if it's posted on a blog, Tumblr, or forum? It’s often dismissed without a second glance.

🗣️ Tone and Power Imbalance Academics often speak declaratively: “this is what it means.” Fans more often speak collaboratively: “could it mean this?” That tonal difference — authoritative vs. exploratory — can feel condescending, even when unintended.

🛠 The Irony…

Tolkien himself was, in many ways, a fan too.

He drew from ancient and medieval myth — Beowulf, the Kalevala, the Eddas — and reimagined them through his own linguistic and philosophical lens. What he created wasn’t just academic — it was deeply personal. Myth-making driven by passion, not publication.

In a 1951 letter, he described creating “a body of more or less connected legend… which I could dedicate simply to: to England; to my country.” By then Middle-earth was alive on the page, but the soul of it remained devotion — not dissertation.

His languages too began not with a fixed blueprint, but curiosity. While he applied philological rigour, many of his tongues grew organically — scraps in margins, evolving ideas. It was world-building through love.

Today, that process — if not bearing Tolkien’s name — might be ridiculed as fan-fiction, overreach, or headcanon.

🌟 Fans Illuminate, Not Compete

Some hear “fan” and think “lesser.” But that’s not the role fan-scholars play. They’re not rivals — they’re windows.

A Tumblr post about the symbolism of Durin’s Crown might inspire an academic paper on Tolkien’s constellations. A linguistic deep dive into Neo-Khuzdul — often dismissed for not being canon — might provoke serious inquiry into how constructed languages evolve after an author’s death.

This doesn’t threaten scholarship — it expands it.

Yes, we must distinguish what Tolkien wrote from what is interpretation, invention, or reconstruction. That line matters. But one does not cancel the other. Creativity need not come at the expense of rigour — and vice versa.

⚒️ What I’ve Learned

I’ve written thousands of words on Dwarves. Studied everything I could find. Tracked terms through decades of drafts, letters, footnotes. Corrected myself. Rewritten. Built. Trashed. Began again.

Not for a title. Not for a citation count. But because it matters to me.

Am I a fan? A scholar? Something in between? Honestly, why does it matter?

The name “Dwarrow Scholar” was chosen carefully. Not to claim authority — but to honour an older meaning of scholar: Not expert. Not professor. But student. A learner. One who studies.

That’s what I hope to be — in every post, every translation, every overly-long Khuzdul footnote. Someone who shares love through learning. Someone who, through obsession, patience, and a little stubbornness, can help one small corner of Arda shine a little brighter.

Not to close the door — but to open a window. For fans. For scholars. For all who care enough to read this far.

So yes — I’m a fan. Gladly. A fan-scholar, if you will. Not standing apart from the conversation, but hoping to be part of it — and maybe, in some small way, helping it grow.

If that means I’m “just” a fan, then let that “just” carry the weight of years of study, joy, and shared discovery. Because being a fan — curious, dedicated, and collaborative — has never been a lesser thing.

And if we’re lucky, maybe the walls between titles can give way to shared purpose.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I am going to be playing an rpg soon using the One Ring system, and am planning to play a dwarf. I found your blog and it has been so helpful and interesting, thank you for all of your work!

I have a question about culture - I would like to play a healer/doctor-type character, I’m thinking along the lines of somebody who was a first port of call to treat mining injuries and the like. I’m wondering if you have any info about what kind of role doctors would play in dwarven society considering their immunity to illness, if this is referred to at all in Tolkien’s work, or anything similar?

Well met, and what a fine character concept!

Dwarves as doctors — it might sound contradictory at first, but let’s dig a little deeper (pun absolutely intended).

🪓 First, What Tolkien Tells Us

Dwarves, according to Tolkien, are:

Largely immune to disease — Human illnesses don’t afflict them.

Resistant to fire and corruption — Stronger even than Elves or Men.

Largely Unmoved by enchantment — Gimli famously resists Saruman’s voice when others are swayed.

Exceptionally hardy — They live long lives and are remarkably sturdy.

So no, they’re not seeing healers for the flu or a cough. However…

⛏️ Where Dwarves Do Need Healers

While illness is rare, injury is a daily reality. Consider the life of a Dwarf:

Mining accidents: cave-ins, broken limbs, burns, crushed digits

Forging mishaps: molten metal, sharp tools, inhaled fumes

Warfare: axe wounds, fractures, slashes, arrow injuries

Travels through wild lands: venom, broken bones, frostbite

A Dwarven "doctor" would thus be more like a wound-stitcher, bone-setter, or battlefield medic — part surgeon, part herbalist.

Imagine them with hardened fingers, singed eyebrows, a belt full of salves and clamps, shouting at young miners to "bite on the haft and hold still."

They'd also be skilled in:

Neutralising poison from spider bites, barbed arrows, or toxic fumes

Crafting protective salves for burns or frostbite

Using roots, mushrooms, and mosses gathered in the deep places of the world— the kind of ingredients other peoples have never heard of.

🧪 Healing in a Culture Without Disease

This unique Dwarven near-immunity actually shapes the healer's role differently than among other folk.

Think of it this way:

Dwarves don’t fight decay — they fight damage

A Dwarven healer is likely not your typical soft-voiced herbalist — that which they treat often needs to happen fast - hence they are practical and direct (and no doubt deeply respected).

In a Hall, they might be part of the mining guild, responsible for overseeing safe work and patching up the wounded.

👁 A Word on Dwarven Eyesight

It’s also worth noting that Dwarves are often described (or implied) to be nearsighted — their eyes well-suited to dark tunnels and close work, but less sharp at great distances. While not a "disability" per se, this trait likely influenced their perception-based injuries:

Falling rocks unseen till too late

Missed signs of a cave-in or fault line

Eye strain from fine rune-carving or gem work

Thus, Dwarven healers may also specialise in treating vision strain, developing magnifying lenses, or even crafting protective goggles for forge and mine alike. Though note, none of the Dwarves in the Company of Thorin wore any kind of goggles or lenses (though they were mentioned as being nearsighted) - so perhaps this was "not done" and a mark of some shame amongst them.

🧬 The Two Dwarven Illnesses

While Dwarves were famously resistant to disease — immune to human ailments and untouched by pestilence — two conditions were known to affect them:

Obesity (NKh: “fantagbâsh” - literally "broad fortune") Described by Tolkien that in times of plenty, many Dwarves would grow very fat, becoming physically inept and unable to do much besides eat. This wasn’t framed as a health issue, per se, but it had clear mobility consequences (later in life Bombur had to be carried around by six young dwarves). A good Dwarven healer might be called upon to craft walking aids, prescribe salves, or adjust armour to fit an increasingly portly Lord. Though keep in mind that these "broader" dwarves wouldn't be regarded as ill, but that those with the widest belts would in fact carry considerable status in the hall.

An Older Bombur, as seen in LotRO, next to his carrier-dwarves.

Dragon-sickness (NKh: "uslukh-satas") Not a literal ailment, but a mental affliction — a consuming lust for gold and treasure, often triggered by proximity to a great hoard that had been brooded on by a Dragon. Most famously seen in Thorin Oakenshield, it clouds judgement, isolates the sufferer, and can lead to destructive paranoia. A healer might not be able to cure this sickness, but a top healer might study calming herbs. To what extent that might help is another matter entirely. The Dragon-sickness affected some more than others, and its effects were especially powerful on those who were already greedy and selfish. The most extreme case of this was the Master of Lake-town, who was given a part of Smaug's hoard to help in the rebuilding of Lake-town. Instead the Master took the gold and fled into the Waste, eventually dying of starvation.

Thorin's Dragon-sickness as depicted in The Hobbit movies

🎭 And in Your RPG?

Your Dwarven doctor could easily be:

The old-hand healer at the mining front

A former soldier’s medic who now treats injuries in peace

A herbmaster of the Deep Halls — one of the few who knows where healing mushrooms grow in the Roots of the Mountain

Or even a poison expert, who’s saved more than one axe-brother from a snake’s bite

You won’t need to think about diseases much (with the exception of dragon-sickness and obesity), but you will be the person everyone looks to when the stone cracks or a foe bites.

🩺 Dwarvish Healing Lore —Some Key Terms

If you wish to give your healer character some linguistic depth, here are a few Neo-Khuzdul terms relevant to healing, herbs, and recovery:

Healers & Patients

absâtrathkh – healer (leech); often a traditional, hands-on mender.

basatâl – professional healer; the equivalent of “doctor.”

mamahlikûn – he who is (or has been) treated; a patient under care.

Healing Practices

anradraiblêl – the practice of healing lore, especially bone-setting and cut-binding.

absata'lâz – recovery, the improvement of health after injury or trauma.

Medicinal Plants

ibsêtmajd - Athelas, Kingsfoil

zarsûnakhsag – entscloak, found near the mouths of the Entwash, known to ease the pains of the elderly.

i'bêdkhalf – tunglewort, a healing weed found along the Anduin in Gondor.

itmêm-mujd – settlegang, a Gondorian herb used in wound care.

jalaimgêmshelak – cranesbill, used for treating sores.

kalmunaith – maiden’s helm, a flower with soothing properties, found in Lossarnach.

sedezyusth – plantain herb, a common and reliable weed used in poultices.

Gem-Based Healing & Divination

kâminumkab – earth-reader, a Dwarf who uses gemstones as a focus for prophecy, healing, or magic.

kaminimkêb – earth-reading, a divinatory or ritual technique involving stones and crystals.

Treatments

ibrêzneked – poultice, a heated herbal paste spread on cloth and applied to the skin to draw out pain or infection.

In short: 🛑 No flu, no plague. ✅ Plenty of wounds, burns, bites, and breaks.

And the Dwarves — ever respectful of skill and grit — would honour such a healer greatly.

May your tools be sharp, your salves strong, and your beard never get caught in a splint.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m looking at potential tattoo ideas, and would love Thorin’s line “if more of us valued food and cheer and song above hoarded gold, it would be a merrier world” in runes, but if I’m being honest the more I try to look into it the more confused I’m becoming! Is it even possible? 😅

Could you please help?

Well met,

You’ll find your requested transcription in a previous post: https://thedwarrowscholar.tumblr.com/post/187676991974/hi-there-im-getting-a-tattoo-and-would-love-to

Cheers,

Roy

The Dwarrow Scholar

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I am attempting to construct a word that means "unfinished" or, more specifically, "we are in a state of being unfinished".

For context, the work is a story wherein Thorin is attempting to make amends to Bilbo via a ritual of atonement. I've been using the words 'ultânul and altân to refer to the act of service that he is performing as atonement (escorting Bilbo back to the Shire), but I'm looking for a word that he can use to explain that until that atonement is complete, their friendship is in a kind of limbo, with unfinished business between them. When completing the ritual, I plan to have Thorin use a phrase that you posted in a previous ask, ai-latunsuwê, meaning, "I request that you forgive me (when addressing a male) - formal (archaic))"

For my current need, I thought to take the word majalanattân (They who (males) continue to finish / (again/excessively)) and make it negative by adding the modifier bin- (without (-less), used for nouns or abstract concepts. Example: mute ("binaglâb" - literally: "without language")), but realized that if I used it as binmajalanattân it would probably mean without those who continue to finish. I settled on majalabinnattân to mean "they who continue to be unfinished (without finish)", used in the phrase "We are majalabinnattân" from Thorin to Bilbo.

Am I on the right track? Thanks, as always, for your assistance and fabulous resources!

Well met again, my friend!

Ah, what a linguistically rich question indeed. Let’s dive in.

🪓 Heads-up for casual readers: this one gets deep into Neo-Khuzdul morphology — so unless you're here for a full grammatical spelunking session, you may want to grab an ale and head back to one of the previous posts (or hold on for an upcoming one). But for those of you still with me: onward!

🛠️ The Core Term: majalanattân

This is what's called an Energetic Noun — a noun with repeated consonants that add intensity or continuity to the meaning. And in this case, it’s built with an allied verb in a passive structure.

Let’s break it down:

Structure: Ma(x)Ca2CC(x)ân (Don’t panic — I’ll walk you through this.)

ma– → passive participle prefix

(x) → slot for an allied verb. In this case: jala–, meaning “whole / at once / in one go”

jala– + nat → the verb base [NT] (from anat, “to end”) becomes “to finish” - literally "to end whole".

natt → use of a doubled consonant (the “2CC” part) to mark it as an energetic noun, giving the sense of continuation, repetition or even excess.

–ân → plural personified suffix: “those who” (males or mixed group)

So majalanattân literally means:

“They who continue to be finished” or more poetically: “Those who persist in completing.”

🧱 But what if we want the opposite?

Your goal — “unfinished” — is the opposite concept. The instinct to use bin– (the negative particle meaning “without”) is absolutely right.

However, there’s a rule in Neo-Khuzdul when it comes to allied verbs:

✴️ You can’t split an allied verb compound. The allied verb jala– is fused to the verb root nat. If you try to wedge bin– between them, you break the compound and lose the meaning.

So while majalabinnattân might seem like a good idea, the fact that we cut the allied verb from the verb construction makes it lose its allied meaning, and as "jala" doesn't mean anything on its own, the word itself becomes gibberish.

And as you correctly indicated the option binmajalanattân would make it into:

“Without those who persist in completing” (Which implies these folks are missing — not that they are unfinished.)

Thus, the only proper form is:

mabinjalanattân “Those who continue to be unfinished.”

🧾 In Full: Thorin’s Lament

If Thorin wishes to acknowledge the space between wrongdoing and reconciliation — the full phrase could thus be:

’Atmâ mabinjalanattân. We are those who are still unfinished.

or - from a single person perspective:

’Atmi mabinjalanattûn. I am he who is still unfinished.

Where:

’Atmâ / 'Atmi → “We are / I am” (dependable/Perfect form)

mabinjalanattân/ûn → “those/I who continue to be unfinished”

✅ Final Thoughts

You were already on the right path — only a small structural correction was needed to align with Neo-Khuzdul's compound rules on allied verbs. And truly, this is an advanced bit of grammatical structure, so no shame whatsoever in being only slightly off.

Honestly, this is a beautiful use of the language. When Thorin finally speaks ai-latunsuwê (“I request that you forgive me”), it will ring all the more deeply — because we’ve seen the unfinished journey that led him there.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! Love your work here. I was wondering what would a toast look like in Khuzdul? Something that is the equivalent of “cheers!” and “drink up!” before downing some ale?

Well met, and what a fine question — one best answered over a good pint, no doubt. So: how do Dwarves say cheers? What toast rings through a Dwarven tavern before the first sip of ale?

Let’s get to it.

🍻 “Cheers!” in Neo-Khuzdul

There is an entry listed as:

“yof” — marked as cheers! in the Neo-Khuzdul dictionary. But let’s be clear: this is not a drinking toast. It’s a casual expression of thanks, used in informal, friendly contexts — like "much obliged".

Another term, “amanâth”, appears too — meaning “cheers” in the plural sense (literally, more than one “cheer”). Again: not a toast in the ale-raising sense.

So, if you're looking for a true Dwarven toast before downing a mug — the kind shouted across stone-walled halls or growled over firelit tables — there’s one word that carries the weight:

👉 Ayadurzu!

Pronounced: [ɑjɑdʊrzʊ] Literally: Upon your appearance! Used as: A proper Dwarven cheers!

The toast itself is called an amnâthazlal — a compound meaning “cheer-drinker”.

🪓 Wait... Upon your face?

It may sound odd at first, but here’s the story behind it.

In West-Flemish, particularly where I grew up, there’s a somewhat rowdy tradition during toasts. Before the first drink (and often several after too), the host might call out:

“Op je mulle!” (“Upon your face!” in English — but meaning more like "down your face", and "to your health" at the same time)

It’s a cheer shouted with laughter, camaraderie, and - obviously - a raised glass — a staple of evenings at the pub, darts nights, and warm, noisy gatherings. And that unbridled energy? That, in my opinion, is the Dwarven spirit, through and through.

So when I needed a Dwarvish toast, I reached back to that childhood memory — sitting in the corner of the pub (waiting for my dad to start his darts match), enjoying my lemonade and scribbling in my sketchbook, while grown men shouted "op je mulle!" and laughed like brothers. Hence, “ayadurzu!” — upon your appearance — a somewhat personal nod, perhaps, but one that captures exactly the feeling I was aiming for.

🧭 Breaking Down Ayadurzu

Let’s take a closer look at the construction of Ayadurzu — the Neo-Khuzdul toast meaning “Upon your appearance”:

Aya — “on” or “upon”

Dur — a reduced form of adrâz (“appearance")

It drops its final -z due to the attached pronoun

And its initial a- is absorbed by the aya that comes before it

-zu — the 2nd person singular masculine possessive suffix: “your”

⚠️ Even when addressing a mixed or female crowd, the form -zu stays put — this is a fixed expression, not altered by gender.

Ayadurzu = “Upon your appearance!”

On an internal note - Originally, durzu meant “face” in the earliest version of Neo-Khuzdul (now referred to as Blue Mountain Khuzdul — the earliest branch I developed). Over time, however, the word ’akt became the preferred term for “face”, and durzu, became adrâz reinterpreted as “appearance”. 📌 Side Note: “Ayakt!” — Slang Variant The Neo-Khuzdul dictionary also lists “ayakt!” as a toasting expression. It combines:

aya (“upon”)

’akt (“face”)

This phrase is flagged as slang or juvenile argot, typically used among younger dwarves or in very casual settings. Think of it like shouting “Bottoms up!” — lighthearted, a bit rough around the edges, and more fitting for rowdy drinking games than solemn toasts in noble company.

By contrast, “ayadurzu” is more traditional, though still informal — a robust, everyday tavern toast rather than an academic phrase.

"Ayakt!" is what the apprentices shout. The masters stick with "Ayadurzu!" — at least until the third round.

🔍 Another Vital Side Note: Don’t confuse dur (from adrâz) with dûr — which in Neo-Khuzdul means “naked.” So if you ever find yourself shouting Ayadûrzu! instead of Ayadurzu!... Well, let’s just say the mood at the tavern might shift rather dramatically.

🍺 Tavern Talk: A Few Useful Phrases

Here are some extra lines you might hear in a Dwarvish-speaking tavern, may they serve you well!

One beer please. - Zull ze' kasamhili. [zʊləl] [zɛʔ] [kɑsɑmhɪlɪ]

Make that two! - Sakhjamiye nu' namnâg! [sɑkʰd͡ʒɑmɪjɛ] [nʊʔ] [nɑmnɑ:ɡ]

Can I see the menu? - Kâsakhi ablâgkedas? [kɑ:sɑkʰɪ] [ɑblɑ:ɡkɛdʌs]

I only eat dwarvish food. - Ablagi izul ablâg khuzdul. [ɑblɑɡɪ] [ɪzʊl] [ɑblɑ:ɡ] [kʰʊzdʊl]

This is not what I ordered! - 'Ala lu masajrabul! [ʔɑlɑ] [lʊ] [mʌsʌd͡ʒrɑbʊl]

Can I have the bill? - Kabirâzriri makhashul? [kɑbɪrɑ:zrɪrɪ] [mɑkʰʌʃʊl]

These are just a few of the 200+ phrases in the Deckademy resource: 📚 200 Everyday Neo-Khuzdul Phrases

So, when next you find yourself at the point of toasting, tankard in hand — whether among pillars of a great Hall, your local pub or your very own kitchen — remember the proper toast:

Ayadurzu! Cheers!

And may the ale be strong, the company hearty, and your beard ever be foam-drenched!

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello there!

I got so happy when I noticed you've been answering asks. I love your work and I'm very thankful for all you've done, as a fellow dwarves' lover! Your posts have been great help for my own worldbuilding on dwarvish communities.

Now, I was wondering (and I hope this hasn't been answered yet) if there's any way we can know what Thorin's rings say/mean in the movies of The Hobbit. There's probably info. on that already, on WETA Workshop's "The Hobbit Chronicles", but I haven't been able get my hands on those books.

I know one of them have a sort of mix of runes that represent the first letters of his name, but you are my last hope to try to descipher what the others mean.

(Some pictures of the rings down here)

Anyways, I know this may be a hard question and I really don't want to bother you with it. I'm silently rooting for you to find the balance to complete all your projects and live a long joyous life!

May all your stories be glad ones, and your roads be smooth and short.

-Thorne

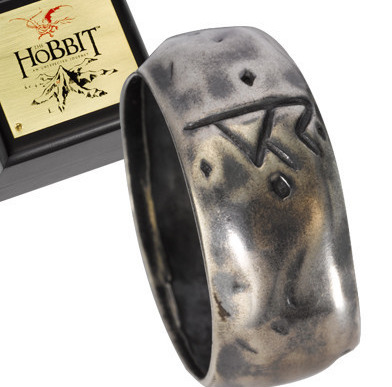

Well met, Thorne! Ah, Thorin’s rings — a fine question, and one that requires a bit of rune-chasing and patience. Let’s delve into it.

🔹 The Silver Ring with the Blue Stone This five-sided sterling silver ring, set with a sodalite stone inside a silver “cage,” spells out Thorin — one letter on each face. Wētā describes it as “a seal and symbol of his status,” proclaiming him King Under the Mountain; though no additional Dwarvish or Erebor symbols are present. The sodalite stone, however, is worth a second look. In gemstone lore drawn from esoteric traditions, sodalite is associated with deep introspection and truth. It is said to help the bearer perceive their strengths and flaws clearly, to still mental noise, and to offer insight during times of internal struggle — qualities that resonate strikingly with Thorin’s arc. Whether that symbolism was intentional or a happy accident, it adds a thoughtful undercurrent to the piece.

A second, nearly identical version of this ring exists (but without stone), with a slightly different band that merges seamlessly into the face. Reduced number of markings, but same meaning.

🔹 The Simpler Silver Ring This rougher, somewhat plain sterling ring is said to bear “a simple Dwarf rune.” Except… there’s no such rune in either of the canonical Dwarvish scripts. However, when viewed through the Hobbit-style runes (Anglo-Saxon Futhark variants used in the original book), the symbol appears to be a fusion of Th and O — the first two letters of Thorin’s name. Very likely a personal monogram.

🔹 The Gold Ring Here’s where the real runic headache begins. This ring has two inscribed lines: an upper and lower band, using Hobbit runes.

🡒 The top line clearly contains the word rune, and what precedes it appears to be a stylized moon ("mmoon") — likely forming moon rune, a fine nod to Erebor’s hidden door.

🡒 The lower line is less clear. It seems to contain two "o" runes, an upside-down "l", a "u", and an "H" — possibly forming huloo, a phonetic hello. A little hidden humour, perhaps?

So, in short:

The rings name him, hint at legacy... or might just say "hello".

Let’s be fair — for all the gravitas Thorin’s character holds, the rings themselves are more props than relics. The inscriptions aren’t exactly heirlooms of Khazad-dûm. Still, they’re interesting artefacts in how they try (with varying success) to gesture at identity, kingship, and Dwarven symbolism — even if just on the surface.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, Loremaster! First let me start by thanking you for this wonderful resource and all the work you've given to the fandom, you are truly a lord of gifts to us all. (And thanks especially for the lovely Dwarven Lament that I recently used in my fanfiction, it was the perfect addition to that scene!)

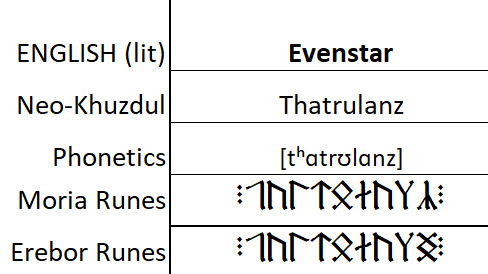

On the subject of your work, I was wondering if you'd be willing to take a look at a translation for me? I am planning on a scene where Arwen earns the praise of the Dwarves of the Lonely Mountain, and they chant "Evenstar" — but in Khuzdul.

Looking through your work, I think that either "thatr-lanzulkhud" or "thatr-lunzel" would be the most likely translation, am I anywhere near the mark or way off?

I know you mentioned having a lengthy queue and a lot of things to do, so no pressure on getting to this in any sort of timely fashion (or even at all), I appreciate your help when/if you ever get around to it; and if not, I remain very grateful for all the wonderful work you've done so far regardless. Thank you! Hope you're having a good day.

Well met tathrin — and thank you kindly for your generous words! I’m honoured the Dwarven Lament found a home in your story — that’s the kind of resonance I hope these works inspire.

Regarding your question about a Neo-Khuzdul rendering of “Evenstar”, I must say your proposed forms aren’t far off the mark at all. Quite the opposite — they show an excellent understanding of Neo-Khuzdul.

✨ On “Evenstar” in Neo-Khuzdul

The most direct form would likely be: Thatrulanz Lit. "Star of Evening"

thatru – star-of ("thatr" being star)

lanz – evening

It’s short, clear, and plausible as a chant or exclamation — especially if used in a formal or poetic moment.

That said, your alternate form “thatr-lanzulkhud” (star-eveninglight) is also conceptually sound, though perhaps the construct state (thatru, "star-of") would be more accurate, making it thatrulanzulkhud. Your alternate form creates a slightly more poetic compound and evokes a stronger visual metaphor — though longer, it might be a better fit for ceremonial prose or inscription than for a chant.

Arwen, as depicted in The Lord of the Rings movies.

🕯 Tolkien’s Layers: The Evenstar as Symbol

Worth noting is that Tolkien himself used Evenstar with deeply symbolic intent (as with all of the names he crafted).

In his 1916 poem O Lady Mother throned amid the stars (alternately titled Consolatrix Afflictorum or Stella Vespertina), he invokes the Evening Star as a Marian image — an emblem of hope and consolation in the darkness of the trenches. While Stella Matutina (“morning star”) is a traditional Marian title, Tolkien’s poetic instinct drew him toward the Evening Star, in this case, which he perhaps found more fitting amidst the shadow of war.

This adds a beautiful resonance to Arwen’s epessë Undómiel, meaning “Evenstar”, derived from undómë (“evening twilight”) + el (“star”).

In that name, Arwen becomes not just a symbolic light, but the last, soft light before nightfall — the end of the Elves, and the glimmer of beauty before their passing from Middle-earth.

“There are the emblems of Durin!” cried Gimli.

⚒️ Dwarves and the Stars

Though Dwarves are not quick to offer lofty praise, the weight of Arwen’s deeds — her sacrifice, her union with Aragorn, her gift to Frodo — might well earn her a rare honour. A chant of “Thatrulanz!” would not be empty flattery, but the acknowledgement of a light not born of their folk, yet worthy of deep respect.

Dwarves, though bound to stone and deep places, are not blind to the sky. Perhaps they do not revere the stars as the Elves do — but instead hold a select few in profound esteem. Among these, Durin’s Crown stands foremost: a constellation said to have appeared to Durin the Deathless as he gazed into the Mirror Mere (Kheled-zâram), marking him as chosen. This sacred crown — likely the Northern Crown (Corona Borealis) — is not just admired, but bound to legacy and destiny.

Thus, when a Dwarf invokes a star, it is no casual compliment. It is a rare and weighty gesture — to liken someone to a sacred sign, a bearer of deep memory and mythic significance.

So when the Dwarves in your tale chant Thatrulanz (“Star of the Evening”) in Arwen’s honour, they are perhaps not merely echoing Elvish poetry, but offering one of their highest forms of praise — likening her to a light revered even in the halls of stone.

🪓 A Final Thought In the event you need the transcription into runes, or wonder how it would be pronounced, the details below:

May your fic gleam like mithril in starlight — bright and enduring!

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey if you get a chance, would you mind translating the poem, The King Beneath The Mountains, into Khuzdul? I couldn't find any pre-existing translations yet so I figured I'd ask. No pressue! :)

Well met — and what a worthy request!

The poem you’re referring to, The King Beneath the Mountains, is one of the most iconic lyrical pieces in The Hobbit, originally sung by the people of Lake-town upon the arrival of Thorin and Company. It serves both as a prophecy and an underlying eulogy of sorts for the fallen glory of Erebor, steeped in hope and longing for restoration.

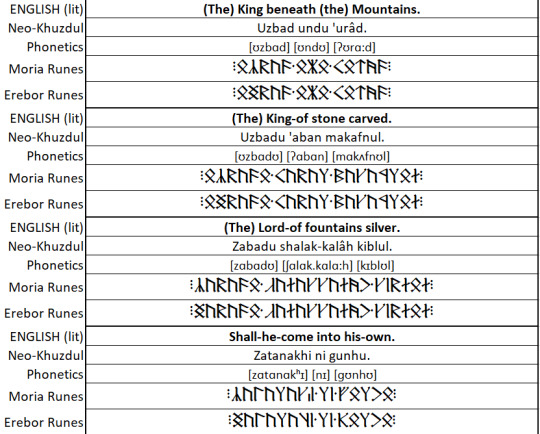

For completeness, let’s begin with the canonical version as printed in The Hobbit:

The King beneath the mountains, The King of carven stone, The lord of silver fountains Shall come into his own! His crown shall be upholden, His harp shall be restrung, His halls shall echo golden To songs of yore re-sung. The woods shall wave on mountains And grass beneath the sun; His wealth shall flow in fountains And the rivers golden run. The streams shall run in gladness, The lakes shall shine and burn, All sorrow fail and sadness At the Mountain-king's return!

Erebor as seen in The Hobbit movies

🔍 A Closer Look at the Stanza’s Meaning

Though short, each stanza of The King Beneath the Mountains carries layers of meaning—particularly when viewed through a Dwarven lens.

Stanza 1 paints a vision of restoration and rightful return. The King (Thorin—metaphorically echoing Durin reborn) is not merely of noble blood, but one whose return has long been prophesied. “Carven stone” and “silver fountains” invoke Erebor’s history, artistry, and abundance. “Shall come into his own” suggests destiny reclaiming its rightful place.

Stanza 2 shifts to symbols of rulership and culture: a crown upheld, a harp restrung—not just the return of power, but the revival of song, heritage, and ancestral memory. “Songs of yore re-sung” places Dwarven tradition at the centre of this rebirth.

Stanza 3 brings nature into harmony with the returning king. Trees, grass, rivers—all flourish. His wealth isn’t static gold in vaults, but flowing, like life itself. It envisions a world where prosperity is shared and visible, not hoarded (somewhat un-Dwarven, even). The very land surrounding Erebor responds—almost as a character in its own right—to the King’s return.

Stanza 4 culminates in joy and healing. Water glows, sorrow fails. It’s both elegy and eucatastrophe: the scars of exile and ruin are—at long last—undone with the return of the King. It suggests not just political restoration, but also emotional and cultural renewal, completing the poem’s arc from loss to wholeness.

🎥 Film Adaptation Notes Peter Jackson’s adaptation takes some liberty with the wording. The first and fourth stanzas are rearranged and subtly altered, transforming a hopeful prophecy into a more ominous foretelling — Bard recalls the lines during a moment of dread rather than celebration:

The lord of silver fountains The King of carven stone, The King beneath the mountains Shall come into his own. And the bells shall ring in gladness At the Mountain-king’s return! But all shall fail in sadness And the lake will shine and burn.

Scene from ''The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug''

Additionally, there’s a short outburst in the book (as Thorin appears), where the townsfolk exclaim:

“The King beneath the mountain!” they shouted. “His wealth is like the Sun, His silver like a fountain, His rivers golden run!”

These lines suggest the poem may be longer than what’s printed—or that additional stanzas were remembered or passed down in Lake-town’s oral tradition. 📜 About the Translation

Translating it into Neo-Khuzdul is no small feat — you’ll find the first stanza fully rendered in Neo-Khuzdul, phonetics, and both Moria and Erebor runes in the image below:

That said, I’ll be honest: translating the entire poem faithfully isn’t something I can commit to right now, for a few reasons.

🪓 Firstly, it’s a sizeable task. A direct, literal translation is relatively straightforward (as you see above), but that quickly becomes... clunky. These lines rhyme and flow beautifully in English — but when directly translated into Neo-Khuzdul, they lose their rhythm, structure, and sometimes even their emotional punch.

🪓 Secondly, and mainly, doing it properly would mean much more than just translating. It would require completely reconstructing the poem: choosing rhyming pairs, finding suitable metaphors, adjusting for stress and meter, and generally composing something that sounds and feels like a Dwarvish song/poem — not just an English translation.

That’s a task I’d genuinely love to undertake… when time allows. But as it stands, to do it justice (and I wouldn't dream of taking shortcuts here), it would take several weeks of iteration, editing and testing. So, one of these days...

Still, I hope this first stanza brings a bit of Khuzdul flair to your fanfic, project, or inspiration corner.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello there! you're the reason I created a tumbler!

Your work is amazing!!

I have several questions, writing a few Hobbit-focused fanfics rn and need some Khuzdul help if you could?

First, I am creating dark-names and was wondering how to translate "Wind song" or "Song of the wind", "Rising sun", "The endurer", "laughing wolf" or "smiling wolf", "Iron hope"?

(Can you guess who they are for? One of them is a OC tho)

Second, I keep looking but cannot find adjectives and animal names to create nicknames, (I only found little dove), but something like "kitten", "my lion", "lionheart", "puppy" and such as "beautiful/pretty/handsome", "smart/intelligent/wise"

Any kind of appellation really, or ways to use descriptions as nicknames in Khuzdul, and think of the stage "pining, in love, not yet courting/ freshly courting, friends, found family".

I would greatly appreciate the help!

Lots of Love 💕💕💕

Well met, Distinguished Dwarf Friend — and thank you for the kind words and support! I’m honoured you created a Tumblr account for this — welcome to the community!

You’ve touched on a number of themes — naming, endearments, and emotional expression. The translations below are primarily sourced from existing resources like the Neo-Khuzdul Dictionary and the Sentence Maker Tool, which I highly recommend for future reference. To save you the trouble of gathering everything from multiple posts and documents, I’ve compiled the most relevant material here, along with a few clarifying notes and additions.

Let’s break your question into three parts:

🪶 I. Requested Names / Translations

Wind: bagd

Wind Song: bagd-akmâth (compound: wind-song)

Song of the Wind: akmâthu bagd

Rising (general): a'lazul (used for objects or the sun, not water)

Rising Sun: ibriz a'lazul

Sun: ibriz (“The bright red-one”)

The Endurer (person): ukhthaz

The Endurer (non-person): akhthaz

Wolf: kund

Smiling Wolf: kund biraithul

Laughing Wolf: kund athul

Iron (adjective): zirnul

Hope: adjân

Iron Hope: adjân zirnul Link to the Deckademy course on animal names

🧸 II. Terms of Endearment and Adjectives

Beautiful / Handsome: abnâmul, banm, or banim (Erebor variant)

Kind: gulukh (from GLKh, “good”)

Wise: bahir

Smart / Clever / Witty: kutub

Heart (physical): kurdu

Heart (non-physical): mudtu

Dove: gaih

Lion: ibrizbunt (“sun-cat”)

Little Lion (affectionate): ibrizbuntanut

Kitten (age diminutive): bantith (from bunt, “cat”)

Kitty (intimate diminutive): buntanut

Puppy / Doggie: kunbanub Examples:

Sâti ibrizbuntanutê → “You are my little lion” (to a male)

Sâtiya gaihê → “You are my dove” (to a female)

Keep in mind that nouns precede adjectives when combining some of the above. For a detailed explanation on diminutives, and the likes, I recommend reading this full breakdown post: 🔗 Little Lion in Neo-Khuzdul

💞 III. Courtship & Emotional Stages

In Love with: ni amrâl aya (lit. “in love upon” – not "with" - uses a different metaphor than English)

Friends: buhâ

Courtship (noun): targidrêd (lit. “beard-swooning”)

Courting (adjective): targidrêdul

Unsuccessful courtship: îrêzasran (lit. “crushing-dance”)

Pining / Longing (adjective): azrâlul (from azrâl, “longing (noun)”)

📚 Final Note

Most of the terms you asked about — and a great many more — already reside in the Neo-Khuzdul Dictionary or can be summoned through the Sentence Maker Tool. These are freely available (via the Library on the site) and a lot faster than waiting for an old scholar to dig through these (especially when there's a lengthy ask queue).

So, before sending your next raven, please do check the archives athe available tools. That said, it warms the heart to see Dwarvish used in thoughtful storytelling. May your characters bear names worthy of song — and may your writing echo longer than Durin’s line.

With axe, quill, and a well-worn copy of the lexicon, The Dwarrow Scholar

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I see that there is a direct translation for an apology, but is that something dwarves often say? Or do they see it as a debt/something tangible must be done to make amends? I have seen in fanfiction where they are forced to cut their hair/beards but I wasn't sure if that is a custom? For context, if one dwarf wrongs another person in a non-violent way, how do they/how are they expected to right the wrong?

Well met—and thank you for that multifaceted question! Let’s dive into it from both a linguistic and cultural perspective.

🗣️ Apology in Neo-Khuzdul

The direct translation for "an apology" is "ushgum", derived from the radicals [ShGM], which mean "to be mistaken", "to make a mistake", "to apologise", "to regret", "to rue", "to repent".

Here are a few key phrases:

shagamruki – "I apologise" in the Perfect form. This makes it a dependable statement, essential in conveying sincere regret.

ashgamruki – "I apologise" in the Imperfect form, hence would not commonly be the go-to form, as this form could potentially be interpreted as lacking sincerity.

birashagammi – “I regret, I repent.” A strong, unambiguous expression of remorse, again using the Perfect form.

These verbs make use of allied forms, a feature of Neo-Khuzdul grammar where a modifying element is attached directly to the verbal root to alter its core meaning:

In shagamruki, the allied form "-ruk" ("over") is joined to the verb tashagami (“to be mistaken”), conveying the sense of acknowledging fault over a matter — thus, a declaration of wrongdoing.

In birashagammi, the allied form bira- ("clear" or "through") is used, intensifying the meaning to "I am clearly/thoroughly mistaken," interpreted as a formal, deeply sincere form of apology and regret.

This structural choice in the language is significant. By using these allied verb forms, a Dwarf doesn’t just express general regret — they make it clear that they both recognize the mistake and genuinely regret it. This dual layer of meaning (acknowledgement + remorse) is baked into the apology, aligning with Dwarvish values of honour.

🕎 Hebraic Influence

Tolkien based many elements of Dwarven culture on ancient Hebrew customs. In Jewish tradition, apologies are foundational. Before Yom Kippur, it's customary to seek forgiveness for any wrongs committed over the past year. The medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides (Rambam) codified a four-step path to atonement:

Confess and ask for forgiveness.

Express sincere remorse.

Make amends.

Do not repeat the offense.

This ties beautifully into the Dwarvish concept of honour through action, not just words.

⚔️ Norse Influence

In Old Norse culture (another go-to source for Tolkien's Dwarves), apologies were embedded in ritual and restitution. Forgiveness could involve public confessions, compensation (wergild), or even exile. Honour was everything.

Forgiveness wasn't just verbal—it was a societal negotiation. The wrongdoer was expected to make things right visibly (often for all to see) and tangibly.

📜 Tolkien’s Lore

Dwarves in Tolkien’s writings are famously proud and slow to trust—but they are not incapable of remorse or reconciliation.

A striking example appears in The Hobbit, when Thorin Oakenshield, on his deathbed, turns to Bilbo and says:

"I go now to the halls of waiting to sit beside my fathers, until the world is renewed. Since I leave now all gold and silver, and go where it is of little worth, I wish to part in friendship from you, and I would take back my words and deeds at the Gate."

A profoundly moving apology.

While Gimli may not always express his remorse through direct apologies, his actions and relationships with others show that he is capable of feeling remorse and seeking to make amends.

💼 Beard-Cutting in Fanon

To my knowledge, there’s no canonical precedent for Dwarves cutting or shaving their beards as penance. However, there is evidence linking beard-rending to grief:

“When Thráin heard Nár's recounting of what had become of his father and that an Orc was ruling their ancestral home, he wept and tore his beard and then fell silent.”

This echoes ancient Hebraic customs, where tearing one’s garments marked mourning.

Additionally, in Concerning the Dwarves, we’re told:

"No Man or Elf has ever seen a beardless Dwarf—unless he were shaven in mockery, and would then be more like to die of shame than of many other hurts that would to us seem more deadly."

So while Tolkien never explicitly links beard-cutting to guilt or shame, the symbolic weight of a Dwarf modifying their beard is clearly immense. It’s not unreasonable that fanfiction has adopted it as a visual metaphor for deep remorse.

A drastically shortened beard—not shaved, but visibly altered—might be interpreted as a powerful personal vow of contrition, rather than a societal norm.

🗓️ In Conclusion

Yes, Dwarves have various words for an apology. But true repentance in their culture would likely mirror both Hebraic and Norse roots: honest speech followed by meaningful action. They likely would not say it often, but only when they meant it wholeheartedly. So, no quick-fix "sorry".

They might say "shagamruki" or "birashagammi", but to make things right, a Dwarf would offer their time, labour, or a physical token of restitution. Honour, after all, is not restored through sentiment alone.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

🧾A Note From Behind the Beard

Every now and then, I receive questions that stray a bit (or a lot) from Tolkien, Dwarves, or (Neo-) Khuzdul. Nothing too intrusive—don’t worry—but more personal curiosities: “What are your hobbies?”, “What’s your background?”, and even, after the release of our semi-nude calendar (yes, that happened), “What’s your orientation?”

I’ve always made it a point to keep my personal life in the background here. Not out of secrecy, but simply because I wanted The Dwarrow Scholar to focus on the Dwarves, their language, and lore—not on the one behind the curtain. With the possible exception of my end-of-year rambles, I’ve tried to stay behind the runes, so to speak.

I never set out to make this about me. But after years of questions—and kindness from this community—I figured it was time to offer a little glimpse at the one behind the stone wall. Heads-up: if you're just here for Dwarves, Khuzdul, and the like—feel free to skip this one entirely.

📆 About that Calendar...

Let’s address the elephant in the forge.

Yes, there was a semi-nude Dwarvish calendar. No, it wasn’t entirely serious.

It started as a simple, genuine idea—I wanted to create a physical Dwarvish calendar with proper Neo-Khuzdul months, cultural motifs, the whole nine yards.

Then a friend casually joked:

“Oh, like those fireman calendars?”

And I couldn’t unsee it: Half-naked dwarves posing with hammers, anvil glistening, beard windswept. Too absurd not to bring to life. So we did. You’re welcome. Or I’m sorry. Possibly both.

🌱 Hobbies

Over the past few years, gardening has become my main thing ("obsession"?). I now live in a beautiful, hilly part of Flanders called the Flemish Ardennes—a land of rolling hills (Think The Shire—but with better beer. Truth. Deal with it, Hobbits.), known for its cycling mainly.

A look at a section of the garden I've created

Plum trees are abundant in my garden (amongst other trees), and I've even started making homemade plum liqueur from them. It’s surprisingly decent. Brewing beer has somewhat crept into the background too (when in Rome).

I don’t watch sports often, but I do have a few faithful loyalties:

As a somewhat fierce fan, I’ve resigned myself to the Toronto Maple Leafs’ yearly playoff disappointment.

Luckily, my joy levels were high thanks to Wrexham’s earlier promotion to the EFL Championship. (And no—I didn’t hop on the Hollywood bandwagon. I’ve followed Wrexham since I was a kid. Still, I’m cheering them on.)

Why these two teams, far from the Belgian coast where I grew up? Well, trips to Wales and fanatic hockey-fan uncles go a long way toward explaining that.

And I’d be remiss not to mention Lili, my white Chow Chow—a four-year-old ball of fluff and sunshine who’s easily the friendliest creature in the entire Flemish Ardennes. She supervises all garden activity with quiet dignity (and frequent naps).

These past two years I’ve also been developing a fantasy management game—a single-player project where you run a Dwarven fighting stable.

You’ll train warriors, forge gear, negotiate with sponsors, go on quests, learn the lore of the land, mine for resources, and aim to win the Emperor’s Cup. It’s a blend of tactics, unique rich lore, and stubborn Dwarven grit, naturally.

More on that when it's ready to leave the mountain.

🎭 Background

Believe it or not, my background has nothing to do with linguistics, fantasy, or Tolkien studies. I actually studied the arts, and ended up in a completely unrelated career. But languages? That’s been a passion since childhood.

Long before I knew the word “conlang,” I was creating imaginary languages in my notebooks for fun. I grew up in a multilingual family and country, which helped—but really, I just enjoyed puzzling through grammar systems like some people enjoy crossword puzzles.

I speak Dutch, English, French, some German, and have dabbled in Japanese, Italian, Spanish, Arabic, and Hebrew.

🪓 Why Khuzdul?

Khuzdul pulled me in not just because it’s the language of the Dwarves, but because it’s very unlike anything else in Middle-earth.

It’s Semitic in structure—structured, yet mysterious and methodical. There’s beauty and hidden meaning in every root. Yes, it can be daunting at first—especially without a Semitic background. But you don’t need to be a trained linguist to enjoy or explore it. Curiosity and patience go further than any degree.

🌈 The Other Question...

Some asked about orientation—fair question, given the tone of my calendar. I’m a straight fellow, with an open and accepting mind. Been happily married to my wife for nearly ten years (together for twenty), and I deeply respect the spectrum of identities others bring to this community. You're all welcome here.

✨ Fun Fact Speed-Round!

First Dwarvish word I ever coined? Honestly, I can’t recall—it’s been thirty years...

Favourite Khuzdul root? Probably [KhGR], which is one of the rare winks to my local childhood dialect. A “kegge” is West-Flemish for “big nose,” and that’s exactly where KhGR came from—it’s now the Neo-Khuzdul root for “nose.” Most personal Khuzdul word I’ve coined? That would be ugloriskhûna—meaning “wise woman known for kindness, humour, and the ability to enjoy life.” The word (and its meaning) was inspired by the nickname of a dear friend of mine.

Most surprising moment? When I visited HobbitCon in Bonn, Germany. I dropped by the booth of the German Tolkien Society to say hello to a kind acquaintance—only she wasn’t there. Instead, someone had a full-on fan moment and asked for a picture with me.

Most moving request I’ve ever received? Someone once asked me to translate a poem for the funeral of their brother.

Best compliment I’ve received? I get more praise than I feel I deserve—but one that truly warmed my heart was:

“You would have made Tolkien proud.”

Most ridiculous runic request? Well, aside from someone asking me to translate The Hobbit in its entirety (which would take me years), nothing truly “ridiculous.” Folks ask because they’re curious—and that’s never a bad thing. That said... the biggest chuckle? A tattoo request for “Meat is back on the menu”—to be inked on a very private part of the body.

And just so you know who’s been rambling behind the beard all this time—here’s a noble mashup a friend made of me, in full Gimli regalia. (Yes, that’s me. No, I don’t imagine I swing an axe nearly as well.)

If you’ve read this far—thank you. Thank you all for being part of this strange and wonderful journey. Your curiosity, kindness, and shared love for Dwarves have kept the forge warm. I hope this answers some of the more personal questions that found their way into the queue. Now, let’s get back to the runes, shall we?

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!

I was hoping you could help me 😭 I read your translation of I See Fire by Ed Sheeran and I was hoping you could show me how “Keep watching over Durin’s sons” would be in Erebor runes…

I tried doing it myself but as I want it tattooed I don’t trust my poor skills 😂😅

Well met!, I’m very glad the translation found you—and I’m honoured you’d consider using it for something as meaningful as a tattoo!

The translated line you mentioned comes from a translation I created for Rebekah’s rendition of I See Fire, set to Neo-Khuzdul. Looking back, I might have liked more time to shape it with proper meter and rhyme, but the piece needed to go live, and I completely understood the push to release it. I'm still grateful for the trust placed in me for that project.

As a small side note—some years prior to that, Matthew Sheeran (Ed’s brother) reached out to request a Neo-Khuzdul translation as a gift for Ed. In return, he composed a themed track for my video/audio work, which I still use to this day: 🎧 The Dwarrow Scholar Theme – SoundCloud I also think I recall some friendly back-and-forth about a runic tattoo at the time, which I believe Ed may have gone through with. (And sorry for the shameless name-dropping. It’s not every day a Sheeran shows up in the inbox.)

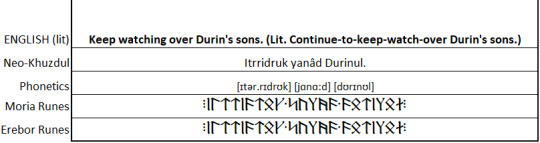

🔤 “Keep watching over Durin’s sons”

Below you'll find the translation/transcription of this line.

Since Khuzdul was traditionally carved in the Angerthas Moria rune set, but you requested the Ereborian variant, I've provided both, - but as you can see, in this case they are identical.

👁 A Closer Look at the Translation

🗣️ Itrridruk Yanâd Durinul (Keep watching over Durin’s sons)

Itrridruk

This is a singular imperative—a command directed to one person ("keep watch over!")

The double r marks the energetic mood, conveying continuity or emphasis: not just “watch,” but "continue to keep watch".

The suffix -ruk makes this an allied verb and means “over”, using the same metaphorical structure as in English (not always the case in Neo-Khuzdul). So in this case, the phrase mirrors the source language remarkably closely.

Yanâd

"Sons", using the Erebor form, which seemed fitting given the background of the line.

Durinul

A possessive compound: Durin + ul, meaning “Durin’s.

As one might imagine the scene after the Sack of Erebor. "I see Fire" would have been very apt indeed.

⚠️ The Usual Word of Caution Before Inking

The Khuzdul used here is Neo-Khuzdul—a reconstructed form I’ve developed further from Tolkien’s limited material, shaped by linguistic principles, previously established versions and respect for the lore. While rooted in canon, much of it is my own invention.

If you’re planning to make this permanent, take a moment to reflect (if you haven't already). Like on stone, runes should be carved with tremendous care—and on skin even more so.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Let me preface my ask with a big Thank You! for all your efforts over these years! I recently discovered the language of Dwarves and your dictionary and online resources have been so helpful to me! Now for my question: in regards to the multiple words/translations for the noble words "King", "Ruler" and "Lord", what circumstances would they be most appropriately used? Is there a difference between a Dwarf Lord of Ered Luin vs King of Erebor, Queen vs Noble Lady, Prince vs Dwarf Lord's son, etc?

Well met ravnarieldurin! Thank you so much for the kind words. Your question touches on both linguistic nuance and structural realities of Dwarven kingship, and I'm glad to dig into both.

🪓 Neo-Khuzdul Terms for Kings, Lords, and Nobility

Many rulership terms in Khuzdul are built from the root ZBD, associated with authority, leadership, and command:

Uzbad – Lord, King, or Commander

A formal title, used for both clan kings and local lords, depending on rank. Example: Uzbad Khazaddûmu - Lord of Moria

Also used in a military sense (more info on military ranks here)

Zabad – Lord (more general)

An honorific or descriptor and respectful form of address, not a title as such. Used in phrases like "'Ala Zabad Uthrâyin, Uzbad 'Urdu" (“This is Lord Thráin, Lord of Erebor.")

Zabdûna – Lady or Queen

The wife of a lord or king, not a ruling title in itself.

There are many, many more terms in Neo-Khuzdul related to royalty and nobility. Here is a non-exhaustive list of related vocabulary:

adshanamrâdul - (adj.) died while in service to nobility or royalty

akandum - mountain hall that has more than one clan lord living in it

Asjâruthrag council of lords from the seven dwarvish clans, that assembles on demand, concerned with commerce and craft

'azghahrâm - mention by a Lord of a praiseworthy act of a warrior in wartime

bahafaklihlêt - repeal of privileges (often trade privileges) granted to a dwarf by a lord

bazrabab - ordinance or decree of a dwarf lord, family leader or clan elder

bunmûfsak - dwarf lady who is influential within the royal sphere

êrâsiziz - yearly tribute paid by a lord to his king

fabsbulku - right of presentation to dwarven royalty

ikrêsifzudnu - land under the power of a lord owing allegiance in turn to a higher lord or king (fief)

kalmudammûn - person of noble rank or birth (noble)

kidizbâha - close, trusted friend and confidant to the head of a dwarvish family, one who acts as an adviser or counsellor to the Lord, with the additional responsibility of representing the Lord in important gatherings.

kuzrûlgab - mediator between the king or lord and the people of a realm

mahizbêdmakargul - (adj.) honoured by a king, queen, lord or lady

nidlugulbulku - excuse or exemption, especially from attending court of a dwarf Lord

radnubsan - person who runs errands within the hall for a Lord (usually a young dwarf)

Ulnaznê - honourific title (acronym meaning "my light in the darkness") given to an adviser (often of a king or lord) whose guidance is often regarded to be of practical value and grounded in wisdom

undukhudsh - person bound by feudal alliance, either as a lord or a vassal (liege)

uzbadishmêz - seeking support of a lord or royal (the act of)

uzbadkayal - royalty

uzbadmahd - letter of appointment from a king or lord

zabadablâg - food good enough for royalty

zabadadmâs - right of the lord of a hall to try and to punish a thief caught within the limits of his hall or realm

zabadashmârul - (adj.) under royal protection

zibdîn - general term for the hall (or noble estate) of the Lord

zudrâdum - town hall; mansion of the Lord

zudraisjêrra - managing royal affairs (the act of)

A "bunmûfsak" at the Royal court.

👑 The Structure of Dwarven Kingship

There is no “King of the Dwarves.” There are seven Dwarven clans, and each has its own king.

When Tolkien wrote “Seven Rings for the Seven Kings of the Dwarves,” it wasn’t poetic—it was literal.

Each clan king rules over various halls and holds, each governed by local lords (uzbad) who owe fealty to that clan’s king.

For instance: The King of Durin’s Folk (Longbeards) rules Erebor and its direct (and near) satellite holds.

But the Lord of the Iron Hills, while sovereign within his territory, ultimately still answers to his clan king. (but more on the special "Iron Hills-King of DF relation" below).

⚒️ Kings Among Kings: Hidden Hierarchy

While each clan king is independent, not all Dwarven thrones hold equal influence.

A notable case: Khazad-dûm during the early Second Age.

In S.A. 40, the Firebeards and Broadbeams migrated (after the destruction of their Halls at the end of the First Age) to Khazad-dûm—originally founded and ruled by the Longbeards (Durin’s Folk). They didn’t merge into one kingdom, but retained their own clan identities and kings, as evidenced by the “Seven Rings for Seven Kings.”

Thus, Khazad-dûm came to house three kings:

The King of the Longbeards, ruling Moria itself;

The King of the Firebeards;

The King of the Broadbeams.

These were co-sovereigns, but not equals. Within the bounds of Moria, the Uzbad Khazaddûmu—Lord of Moria—was the senior sovereign. The others may have ruled over their own clans, but the throne of the Silvertine took precedence.

It is likely that the geography of the region reflected this arrangement, seeing that Khazad-dûm was carved beneath the roots of three titanic peaks of the Misty Mountains:

Zirakzigil (Silvertine) – westmost, under which the Longbeards founded Khazad-dûm (and - even by the third age- would have housed the vast majority of its halls)

Barazinbar (Redhorn) – northmost;

Bundushathûr (Cloudyhead) – eastmost.

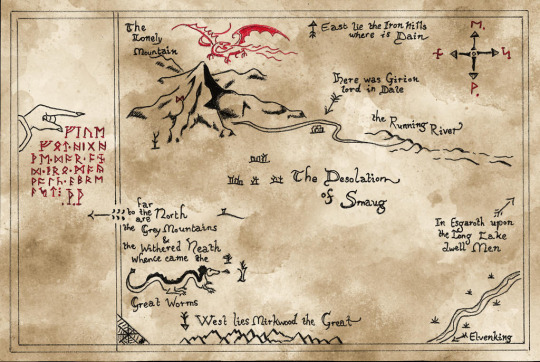

Map from The Encyclopedia of Arda showing Moria and its surroundings. Certain elements of this map are conjectural.

It is not inconceivable that each of these mountains may have housed one of the three clan halls:

The Silvertine range (Zirakzigil) held the oldest and greatest halls—those of the Longbeards, including the East-gate and the grandest delvings - of that we are certain.

Barazinbar and Bundushathûr may have served as the respective centers for the Broadbeams and Firebeards.

Together, these three peaks formed a tri-crowned kingdom, with the Lord of Khazad-dûm as the central, if not exclusive, authority.

Afterall, when dwarves (such as Gimli) talk about Moria, they speak of these three Mountains, while we know the vast majority (if not nearly all) of the known structures were build under only one of these mountains, so why refer to "the Three Mountains of Moria" then, why not simply to Zirakzigil? Well, I believe that each of these Mountains housed these three clans, as such all an integral part of Khazad-dûm.

In this structure of three Kings in one location, allegiance may have been practical rather than ceremonial—each king ruling his own folk, yet deferring to the Longbeard sovereign in matters of shared defense and even law.

So yes—even among kings, there was a pecking order.

The Dwarves may not speak of “high kings,” but in practice, certain thrones—like the one beneath Zirakzigil—stood higher than others.

Zirakzigil, one of the great peaks in the Misty Mountains. On its peak stood Durin's Tower.

[Note in Hindsight:] This reply turned out much longer than I had initially imagined—but then again, so do most of my replies. The nuances deserved the room, and if you’ve made it this far, you’re exactly the kind of reader who’d appreciate it. Dwarves may at times take shortcuts, but I rarely do.

🛡️ On Local Power and Autonomy

Even beneath clan kings, local lords (also an "uzbad") could wield immense power—especially those far from the central court or ruling over resource-rich regions.

Dáin Ironfoot is a prime example:

At just 32 years old (barely of age for Dwarves), he defeated Azog in the Battle of Azanulbizar.

He then refused to lead his people into Moria, despite his king’s command—and his judgment stood.

Though his grandfather Grór was still official lord of the Iron Hills, Dáin was already acting with unquestionable authority.

This demonstrates that autonomy, military strength, and ancestral legacy could raise a local lord’s standing even above what his title might imply.

As such, a Lord of that standing could even have other Lords reporting to them (in a manner making them a High Lord). For instance, considering the distance between the West and East parts of the Iron Hills, it would not be inconceivable that many of the more distant mining colonies would have their local Lords, which would in turn fall under the leadership of the Lord of the Iron Hills. They would all bear the same title—Uzbad—but not the same authority.

Thráin said: ‘Good! We have the victory. Khazad-dûm is ours!’ But they answered: ‘Durin’s Heir you may be, but even with one eye you should see clearer. We fought this war for vengeance, and vengeance we have taken. But it is not sweet. If this is victory, then our hands are too small to hold it.’ And those who were not of Durin’s Folk said also: ‘Khazad-dûm was not our Fathers’ house. What is it to us, unless a hope of treasure? But now, if we must go without the rewards and the weregilds that are owed to us, the sooner we return to our own lands the better pleased we shall be.’ Then Thráin turned to Dáin, and said: ‘But surely my own kin will not desert me?’ ‘No,’ said Dáin. ‘You are the father of our Folk, and we have bled for you, and will again. But we will not enter Khazad-dûm. You will not enter Khazad-dûm. Only I have looked through the shadow of the Gate. Beyond the shadow it waits for you still: Durin’s Bane. The world must change and some other power than ours must come before Durin’s Folk walk again in Moria.’

Dáin Ironfoot after the Battle of Azanulbizar, commanding his King Thráin II not to enter Moria.

⚔️Note on the aftermath of the Battle of Azanulbizar

Tolkien writes:

“And those who were not of Durin’s Folk said also: ‘Khazad-dûm was not our Fathers’ house. What is it to us, unless a hope of treasure?’”

At first glance, this line seems puzzling—particularly given that the Broadbeams and Firebeards had called Khazad-dûm home for over five millennia. That such clans would dismiss it so readily appears, on the surface, inconsistent. One might view this as a rare oversight on Tolkien's part.

But there are other possible explanations:

Perhaps “those who were not of Durin’s Folk” refers not to the other six clans as a whole, but to the four clans of the east that had no ancestral tie to Khazad-dûm.

Alternatively, by the time of Azanulbizar, Khazad-dûm had already been abandoned for over 800 years, its halls darkened by the Balrog. The Broadbeams and Firebeards, though long settled there, had since established new realms elsewhere. And unlike the Longbeards, Khazad-dûm was not the home of their First Father, nor the seat of their current king.

Thus, by the Third Age, even if the Broadbeams and Firebeards remembered Khazad-dûm fondly, it may have no longer held the symbolic weight it did for Durin’s Folk—especially when reclaiming it would mean war with a terror still engraved in their memories through story.

👑 Princes, Heirs, and the Line of Succession

Neo-Khuzdul provides precise terms for various levels of noble succession:

uzbadyand – prince (used chiefly in Erebor and among Durin’s Folk) Lit. "lord-son", using the Ereborian form yand = son. As seen in "Yanâd Durinul" (sons of Durin).

uzbad-dashat – prince (as used generally)

rayad – heir A designated successor to a throne.

sanrayad – crown prince (lit. “perfect heir”) A specific title used for the heir apparent of a Dwarven clan king. Here the prefix san- implies formal recognition.

More details of the succession of Dwarven Royalty (and if Dís could have been Queen, amongst other related questions) can be found in an older post HERE.

👑 On Nobility and Royalty

Among the Dwarves, nobility and royalty are distinct.

Nobility refers to those who hold hereditary lordships—the lords of halls and regions, along with their spouse and direct descendants (sons and daughters). These are Uzbad (and their immediate families) in service to a clan king.

Royalty, by contrast, refers to those of direct kingly blood—the immediate family of a reigning king within one of the Seven Clans. This includes not only the king’s children, but also his siblings, first cousins, uncles, aunts, and grandparents. These royal houses form the core bloodlines of the Dwarves’ ancestral thrones.

While both may be addressed as Uzbad or Zabdûna, the difference lies in scope and proximity to the clan kingship.

As an example: At the time of the Reclaiming of Erebor, Gimli would have been considered nobility—as he was second cousin once removed to the King, both descended from King Náin II, Thorin’s great-great-grandfather. However, Dís and her sons (Fíli and Kíli) would have been considered royalty.

🧠 Summary

So yes—there are clear and deliberate distinctions between kings, lords, princes, royalty, nobility, etc... Even among kings, not all thrones sit at the same height, and even among lords, some carry more than a hall’s worth of power.

Thank you for reading through to the end. Dwarven matters are rarely simple—and even more rarely brief.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, and good day. I want to ask for an translation for my username. Little tailor or little dressmaker. I haven't found something like tailor in your libary, or I haven't searced deep enough. In this case I need to excuse.

Is there a khuzdul word for someone who make clothing?

I would be very happy if you could help me.

Thank you.

And a very good day to you as well!

You're absolutely right that “tailor” isn’t obvious in the dictionary—but it is in there (though not specified as such). And, there’s some nuance to how it's expressed in Neo-Khuzdul.

🧵 Terms for Clothing-Makers in Neo-Khuzdul

Neo-Khuzdul actually features several distinct terms for different roles related to garments and clothing:

baratâl – “changer” A tailor’s assistant: one who alters or repairs garments.

lakasâl – “stainer” A slopseller: one who deals in cheap, ready-made clothing.

faradâl – “suiter” or “fitter” A clothier for nobles, versed in fine materials and cuts.

nakadâl – “wearer” Though it literally means “wearer,” this is the correct word for a professional tailor—someone who makes clothing as their trade.

The form nakadâl follows the CaCaCâl pattern used for professionals (e.g., zaharâl = builder), derived from the NKD root associated with clothing and wearing.

🧶 What if they’re not a professional?

Commonly we use the agent form (uCCaC) for this. However... here’s where the language gets interesting: the standard agent form of the same root—unkad—means “wearer,” not “tailor.” So it doesn’t refer to someone making garments for others, but rather someone who simply wears them.

If we want to describe someone who makes clothing but not professionally (e.g., a parent sewing for their child, or someone making a ceremonial garment), Neo-Khuzdul uses an allied agent form:

mahunkad – literally “make-wearer”, meaning: he/she who makes something wearable.

It’s a neat construction, combining the allied construction mah- (“to make, to create”) with the agent form of the root. It’s worth noting that these entries "nakadâl" + "mahunkad" do not follow the standard agent-professional pairing (like zaharâl and uzhar).

The dictionary currently doesn’t list allied agent forms, but I’m glad you asked—because this is literally the last structural category on the to-do list. And yes... after nearly two decades, that means the full lexicon project is finally approaching completion. On the horizon at last!

🪡 Your Username: “Little Tailor”

In Neo-Khuzdul, “little” is mim, and it follows the noun it describes. ("mim" is a wink at Mîm, one of the last Petty-dwarves, by the way)

So the correct translation of “little tailor” or “little dressmaker” is:

nakadâl mim

May your thread never fray, and your seams hold proud.

Ever at your service, The Dwarrow Scholar

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

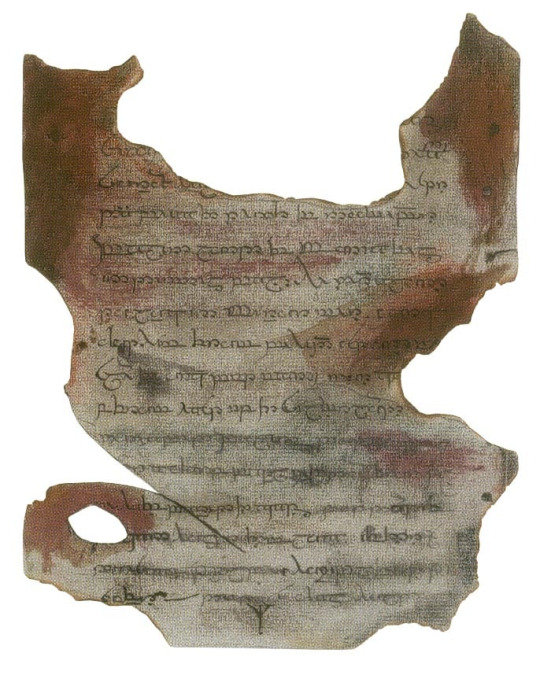

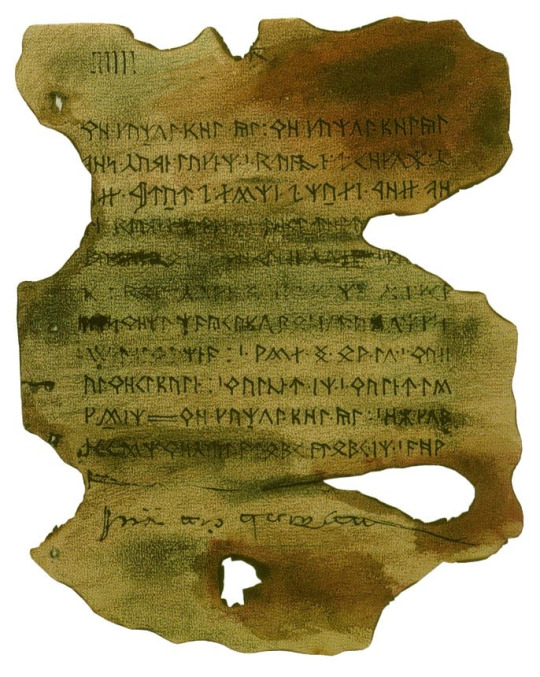

Hello! For scholars/scribes or everyday use, which writing system would be used, Cirth or Tengwar? The Dwarves adopt Cirth for their stone carving, but I would imagine that writing exclusively in cirth would put a lot of strain on writing instruments and, well, wrists because of how stiff and angular it is. IRL, cursive scripts are developed to write faster. In the film, the book of Mazarbul starts off in cirth but the last line is a messy cursive (poor Ori...). Do you have any thoughts?

Well met!