Tam | 🇦🇲 | Late 20s | I accept any and all pronouns | AroAce | Nerd | Musician | Writer | Artist | Generally incorrigible

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

being the last one to send a message before the chat falls into sudden silence always feels like u just made the worst faux pas of your life and you go sorry guys was that weird and they're all like no sorry I was just looking at a leaf on tbe ground leaf.jpg like oh ok

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

the older i get the more sensitive i become to warm genuine words, like wow you really think that kindly of me? hold up, lemme cry

95K notes

·

View notes

Text

Emoji Prompts

🎂 : A birthday headcanon.

💩 : An embarrassing headcanon

💀 : An injury headcanon

👄 : A kiss headcanon

💔 : A breakup headcanon

🌟 : A secret wish headcanon

💍 : A marriage headcanon

👶 : A family headcanon

💧 : A sad headcanon

🛁 : A bathing headcanon

🛏 : A sleeping headcanon

💥 : A fighting headcanon

😳 : A confessing headcanon

👔 : A clothing headcanon

❤ : A romantic headcanon

☁️ : A soft headcanon

🌑 : A dark headcanon

😜 : A random headcanon

🎃 : A halloween headcanon

😤 : A jealousy headcanon

⌛ : A final headcanon

🌡: A sick headcanon

🍺 : A drunk headcanon

🧨 : An unexpected headcanon

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

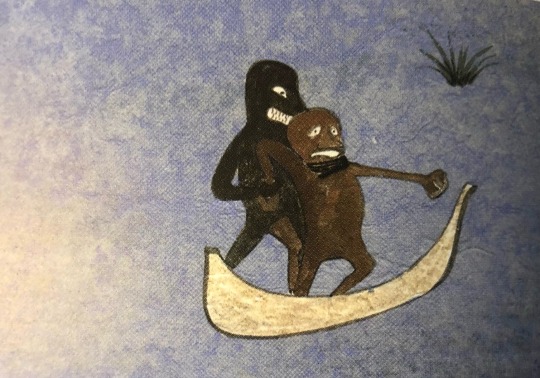

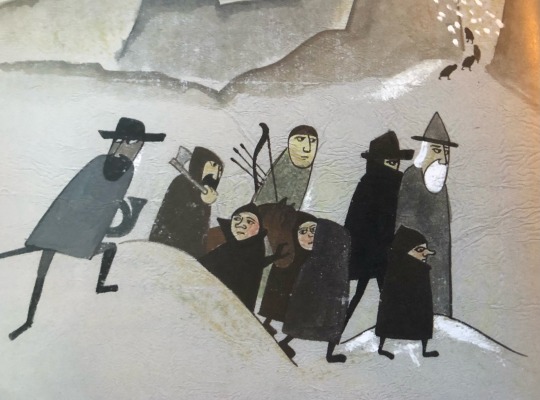

My favorite Tolkien illustrations by Cor Blok in no particular order:

Bilbo and Gollum. Bilbo is the moon for some reason which is cool i guess

Smeagol and Deagol. I love the seaweed in the background, great attention to detail

Frodo serving Robin Hood-realness at his and Bilbo’s birthday party. Literally iconic

Isildur taking the ring from Sauron. Its great but I would like to see more of Sauron than just his hand, because I think he has the potential to look really cool

Pippin jumping into the bath at Crickhollow… no comment

Bilbo gives the Mithril coat to Frodo. Great poses, very stiff and awkward. I like it.

The fellowship. This one is a classic.

Gandalf and the balrog. Amazing

Boromir trying to take the ring from Frodo. I love the way he reaches for his sword, it looks very natural

Merry and Pippin and Treebeard. I like his legs and the fact that it looks like he’s wearing shorts.

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

emails suck. unless they are from ao3, then they are the best thing to ever happen to me

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

lookit mah art (fic) boi pt 2

Boromir Week Day 2: Maternal Family, Grief/Loss

Written for Boromir Week 2025 (@boromir-week), for the day 2 prompts ‘maternal family’ and ‘grief/loss.’ I’ve been a lurker in the LotR fandom for about a decade but have always been too intimidated by the prospect of actually writing fic for it, but Boromir is The Guy Of All Time and I couldn’t resist crawling out of the woodwork for this event. Couldn't manage to do something for the full week, but this is the most fic writing I've done in almost two years, so that feels like progress!

The Houses of Healing. Warped. Halls stretched, an impossible, impassable distance, light at each end like two mirrors placed at odds. A pallor, moon-bright, beyond the shadowed corridor; a bustle of faceless folk in Healers’ robes, wicked knives in hand.

His mother, lying upon a small cot. Dirty, dingy. Fraying linen. No good for a sick woman. No good for even the most wretched swine.

The Healers that were not surrounded her, a murder of crows at a carrion feast, and their hands were no more, they were only knives. Knives in and of them, cutting his mother open. All up the veins of her arms, down her legs, but she did not bleed, for those veins disgorged a black stuff like pitch as they cried to be opened, cried when it dripped, splattered, crumbled over the floor, like wet ash. Shadow inside her, screaming its death throes on the filthy floor.

At the end of the corridor, a small washroom. The black stuff welled up in the cistern in great heaving clumps, endless. He tried to shove it down: first with his hands, but it broke apart beneath them, clinging to his skin, a second skin, in and of him, too, and no matter how he clawed at himself he could not cast it off.

In one corner of the room there was a well, and there was too much mess to question why. Bucket after bucket of moss-filmed, brackish water he drew up from its depths, to try and wash the ash away, but when the water touched it it only grew as some foul beast, like a tick gorging itself on blood, and clogged up the works. Clogged up the works, and clung to his skin, spattered over his white shirt and his bloodied lips, and tasted not of Mordor-ash but sweet rot, meat gone off, dead flesh. He spit, retched, tried to rid himself of the taste, but blood spilled from his mouth when he opened it, painting his chest all awash in red, marred by clumps of black.

Back to the well. His arms burned. His whole body burned. But he had to fetch more water.

No one could see him. No one could hear him. And it was better they couldn’t, he needed to clean up the mess. The ash was in the pipes and on the floor and in the water and all over him, and it would only make his mother sicker, if it welled up faster than they could cut it out of her, and no one could see him, to know he was making it worse. No one would help him, if they knew he was making it worse.

He had to fetch more water. Had to get up, to fetch more water. Had to clean up the mess.

He staggered the few steps, the few miles, to the door. Slammed it shut. None turned to mark the noise. That was good.

To the well. To the rope. His hands burned, flayed open on the rope, and the ash stung him, where it touched his skin. His hands shook too badly to bear the bucket aloft, he could only drag it, and now the whole of him was shaking, too much strain on weary limbs, and the water slopped out. Hissed where it touched the ash and the blood upon the floor. The whole of him, what was left of him, shaking from the inside out, and it’s all he could do to keep hold of the bucket as he retched again, innards wrenched up out of him with the blood that burned his skin. But he does not let go of the bucket. Cannot let go of the bucket. For the water was filthy, unfit for even a dog to drink, but it was all he had left, to try and wash away the stink of Shadow.

Boromir blinks awake.

Too loud. Too bright.

For a moment he doesn’t know where he is, or when. Knows only that he’s trapped, suffocating, weight and heat pinning him down, and he cannot breathe as he ought, and whatever he’s lying in is damp, salt-damp, like he was one of the bloody crabs they had buried beneath sand and seaweed to steam the way Imrahil dátheg taught them, Valar above, but he was being cooked alive–

Breathe. Breathe as the soldiers did. In four hold four out four hold four. Until the breaths stop jabbing needles down the back of his throat, stop sticking in his chest and shivering on the air. Like he’d caught his finger in a door frame, or beneath the blow of a hammer, everything in his chest clutched up tight. Blood rushes in his right ear, in time with the thundering of his heart. Out of time with the rush and roar of the waves, that never stopped, the crashing push-pull he could feel tugging at his limbs, his very blood, even now, some days since they’d disembarked.

Dol Amroth. Prince Adrahil’s hold. His mother’s home.

There’s nails piercing his skull. Just above his ear on the left side. Above his right eye. Nails piercing his skull, a yawning pit in his stomach, hollow hunger and swirling sickness killing the itch under his skin that never went away, to move, to do, to be. He does not think he could move even if he tried. Does not think he wants to. Not here, where the cold light of the moon shone brighter than even the summer sun back home in Minas Tirith, burning away the shadows he longed to hide in, that none might trouble themselves to look on the mess of him. The shadows where the fading vestiges of the dream tried to hide themselves, but they could find no purchase there, and so slunk back to him, where shadow lay curled round him, the only thing left in this world that would hold him.

His head hurts. Everything hurts.

It might be hours, that he lies there. Might be but minutes. Maybe just seconds. Just…breathing. Breathing, breathing, until his heart slows, and the rushing in his ear with it, but never in time with the waves. It would be better, if they beat in time. His body in tune with nature, not pulled every which way away from it, it would be better if they sounded as one. He could sleep, then. But they remain out of time, out of tune, ever out of line, and it makes him…

It should make him angry. Would have, before. But nothing had felt real, since their mother had last taken to her bed, nothing had–felt. It was all just…dim. Muffled. Like sea-fog, that crept in out of nowhere until all the world was grey and cold, and you felt the only soul in the world, adrift, because the fog covered all, and you could see nothing, touch nothing, and nothing could touch you. Until you forgot what it was to see, to touch, to be touched, because the fog covered all, and you forgot it had ever been else.

The ship had run afoul of a storm on the way. A squall. Everything shrouded in fog, the weight of lightning in the air like chains winding all round his limbs, freezing him in place. That was how the world was, now. And it was better that way. Better to live outside himself, locked away from himself. He could stay standing, if he didn’t look at the way the ground under his feet had been torn away. Could stay strong, if he told himself he had always been cold, and couldn’t reach for the memory of what it was to be warm. Everything that had burned, now a mere itch. Everything that had hurt, now a dull ache. Like an old bruise, half-healed, nigh-forgotten, that you had to press on to feel.

But now everything hurts.

A part of him wishes his brother were here. Though Boromir had not slept in the nursery in Minas Tirith for months, for it was no fit place for one already a squire, too soon to be a man, for as many months Faramir had been sneaking into his room a-nights, or Boromir back into the nursery, and he would hold it in himself till he died that he preferred it that way. But Faramir was in the nursery with baby Elphir, and though there was room enough for Boromir there, too, he had spent the past nights there, he could not bear the thought of any eyes on him, tonight, could not bear the weight of another being in the room, that ever-present pressure to be in the presence of any other, and in any case if Faramir had had nightmares of his own he would have snuck in by now. Not that he wanted his brother to have nightmares. If he had his way nothing would ever harm the little one: not man nor Orc nor foul sickness nor fell dream. But his way was not the world’s way, if he had no power to change it, he could at least fight it. Strike a blow against it with one arm, and bear his shield in the other, to shelter those he loved from the worst of the pain he would fain they never knew at all. Let the lad hide himself from the world in his arms, that he might see with his own eyes that he was, if not wholly well, at least unharmed.

And naught would harm him, while Boromir was there to protect him. So he had vowed from the moment of his birth, standing by his mother’s side as she looked down upon the babe in her arms, eyes too bright with fever and tears like jewels and a kind of love so desperate it frightened him.

This is your brother, Boromir, she had said, when he held the babe in his own arms, and marvelled at how this little person, not yet an hour old, was a soul all his own, who had buried himself deep in Boromir’s heart where he would live beyond death. No matter what poison the years of toil and trial work on you both, he will always be your brother. You must protect him; you must guide his hands and feet, and ever walk beside him, though the years would bid you walk before. Do not let the shadows claim him.

Not the Shadow in the East, that devoured more of their home with every passing year; nor Boromir’s shadow, for when the ash and the haze bloodied the sun, their people looked to him instead. The winter babe, the miracle child, who had railed against the Shadow from the very moment of his own birth, so all the folk of the houses said. Twisted round in the arms that held him, for babes were born in chambers facing West, and screamed, and kicked out at the black stain marring his sight, as though he had any hope of striking some lasting blow against it. It was a fair omen, the people whispered. Born to fight, the land’s born protector. A beacon of hope, a light in a darkness without end. He would shine, he would burn, for the people wished it of him, and their father needed something bright in the world he drew dark curtains over in his despair, and someone had to. Why not him, he who was older, stronger, he whose duty was to serve Gondor to the last, even if it meant the last of his lifeblood might water her fallow fields just that bit longer? Why not him, if it meant Faramir could step out of the shadow he cast and into the peace he had fought to give him?

It was the least he could do, when he had failed to protect Faramir now. Better that he die, if it meant Faramir could live. Better that he leave Faramir to sleep now, if it meant he might find reprieve from the sickness of grief for a little while, and none might be by to see Boromir’s weakness. For his hands still shake, when he tries to shift the choking covers off. And everything still hurts.

Just one night. Just one night alone, unseen, unasked for, unneeded. Just one night, when no one needed him to be strong, or cheerful, no one needed him to be anything at all, that he might break apart in peace, and piece himself back together with none the wiser once his hands grew steady again. Make himself whole again, that he might be of use. For broken pieces left only mess, and he had to clean up the mess. He could not, would not let the dream come to pass.

Just one night. Surely it was not so gross a sin, to not be strong for just one night.

X X X

So much their mother’s sons.

Imrahil of Dol Amroth had wasted no time after his sister had been laid to rest in the Silent Street, to ask whether he might bring her sons back with him to spend the summer as they had every year ere the last, when Finduilas had been too weak to travel. In part because Finduilas would have wished it, but in larger part because it would do them well, to have at least one thing that was familiar in which they could take comfort, amidst such terrible upheaval. So he had said to Denethor, pleading his case in the small hall. Had said, too, that it might serve Denethor better if he could mourn and marshal himself without the need to coddle the children’s tears, though the words burned like bile in his throat to utter. But he knew they would sway the intractable Steward, who had no patience for his own sentiment, that he was ever quick to deem weakness, and less for the like in any other. Even his own children, who for all their eyes were dark with grief as those of men grown, were still so young.

How could he leave them in Minas Tirith, when Denethor’s eyes fair burned with hatred to look on them? They who carried so much of their mother in them: Faramir with Finduilas’ eyes, her probing questions, her sensitive spirit and way of seeing deeper into men’s hearts than they knew what to do with, so much sharper yet so much kinder than Denethor’s own Sight; Boromir with her sea-carved features, her gentle heart, her fiery passion that burned too bright, burned out too quickly. He could hardly even blame their father for being wary to look on them, when just the sight of them brought the image of Finduilas back to fractured life.

They had tried so hard, that wretched day. To be small. To be good. Faramir buried his sobs in his brother’s tunic, thumb in his mouth as though he wished to silence himself, the questions that were ever wont to pour from him as clear water welling up from a mountain spring, muddied now by this storm of feeling he might not even remember, in the years to come. He had followed the procession like a faithful shadow, though his legs grew evermore unsteady with the unaccustomed toil, and when he stumbled, Boromir was there to steady him; when he fell, there to catch him. Boromir had had one hand up to help bear the bier, though his child’s strength, too great for his age though it was, could do little that the six grown pallbearers, his father among them, could not. And with his other hand he had carried the little one, when he could walk no longer. Had carried him down through all seven levels and back again, and stood at his father’s shoulder as if to guard Denethor from the weight of a thousand tearful eyes, or perhaps to guard the people from the poison of their Steward’s silent grief, and all the while had shed no tear, nor spoke a word but to comfort his brother, and stood rigidly upright. Unbowed, though the weight of the broken yoke of his family would have borne a lesser man to the ground.

No. Better they come to Dol Amroth, and be among those would would give place to their grief; would weather the storms of confusion and rage and sorrow that would sicken them to keep inside themselves, the way their father would counsel them. The way such things had sickened that father, such that his heart had turned to stone, and he looked at his sons as though he wished to cast them and himself into the grave with his wife, for the light of his world had been buried with her.

Imrahil grieved with him. No matter than Ivriniel and Adrahil their father could not bear to look on him, and railed that he and his city and heart of stone had killed Finduilas, even as the vase killed the wildflower no matter what care he who tore it from the free earth lavished on it. But Denethor had loved Finduilas as best he could, and she had loved him, as much as he would let her, and for all he felt they all had failed her, to let her go, she had had her own pride. Would never have countenanced leaving Minas Tirith when the greatest shares of her heart were there.

He grieved with Denethor. But more than that he grieved for the boys. So he had pleaded, and cajoled, and Denethor had not protested quite so much as he had expected. The grey weeks aboradships had passed in a haze, unmarked by them all, but once the squall had blown over the skies had cleared, and it felt a great weight off his heart, to breathe clean air again, and to see the blue of the true sky.

The air smells like summer, Faramir had whispered when they pulled into port. The first words he had spoken since he had asked his brother in the tomb whether their mother’s spirit would disappear from Mandos’ Halls after her body rotted.

Faramir, at least, slept peacefully this night. Curled up upon the cushions of the window-seat like a little cat, his book of wonder tales carefully closed. He did not wake, when Imrahil bent to gather him up: only hummed softly, and cuddled closer to the body that held him, clinging like a limpet when he tried to set him down in bed. So he sits himself down, instead, and rocks the boy gently in his arms, and tries to ignore the way his heart feels too large, of a sudden, for his chest, digging into the cage of his ribs with a sharp pain like the bone was splintering into the soft tissue.

Finduilas, too, had always slept better by the sea. Soothed by the song of wind and sea and stars. And neither of the boys slept much on the ship, and they had not slept at all the first night here, nor the night prior. Idhreniel had gone both nights to check on them, and reported that they had sat up together the whole night in the window-seat: Faramir curled up in Boromir’s arms as the elder talked himself hoarse, too low to disturb Elphir or to make out any words from the doorway, though he had fallen silent when he’d marked the shadow upon the threshold. Silent and grave as the stone of his home, and Idhreniel had wept, a little, when she had told Imrahil the boy had glared at her like he wished to run her through, before he had realised who she was. Like a wary guard dog, hackles raised against the slightest hint of a threat to what was his to protect, a look no child ever ought to wear. And it was only in deference to that look, that terrible, red-eyed, cold resolve, that she had left them without a word.

But Faramir slept, this third endless night, and Boromir was not here.

Idhreniel and Ivriniel had argued hotly against giving him his own room. It mattered not what the custom was in Minas Tirith, it would be better for both boys to be near each other. And on the ship Boromir himself had said that he was a soldier of Gondor, he would know far worse billets soon enough, and he would sooner sleep on the rug before the hearth like a dog than leave Faramir on his own in a strange place. None had had the heart to dissuade him. But Imrahil had argued, instead, that it would do them both well to have some private place to retreat to, if they needed it, and so they had made up the little anteroom adjacent to the nursery for Boromir, not expecting it would see much use. But it was to that room that he had retired after supper, after eating too little and saying less. Faramir, with a strange glint in his eyes that bespoke of knowing far beyond his years, had laid a hand on Imrahil’s arm, and whispered that they were best leave him alone till morning, he would be alright by then. He always was.

Faramir had scowled, as he’d said it. Like he couldn’t quite believe anyone could always be alright, not even his bold brother. Which meant it was Boromir who believed it. Boromir who felt he had to be so, and Faramir who let him wrap himself in the falsehood like armour, for to try to be otherwise after so long being only strong would break him.

Ai, sister, what has become of your boys? But she would never again answer him.

The barred nursery window had been opened as wide as it could go, though no breath of wind off the sea stirred the heavy air this night. The window in Boromir’s room, though, was shut up tight, though Boromir had ever been the one to throw open the windows of any chamber he found himself penned up in; to run to escape the confines of those chambers, because he claimed he could not breathe, in places where nothing moved. The window had no curtains, and in the bright moonlight the blanket-covered lump huddled up on the bed makes Imrahil frown. It was far too close in here, far too warm, for what seemed to be every spare blanket from the sea-chest at the foot of the bed. But Boromir had always been thus, preferring to sleep half-crushed beneath weight that would have suffocated a less robust child. Well Imrahil remembers Finduilas writing them of this peculiarity of her firstborn: how he had used to burl up under his father’s hauberk in those distant tender years before Denethor had taken to wearing it beneath his robes like a second skin, training his body and mind wholly for war and hardening himself to all in the world that was gentle.

Imrahil had asked Boromir once, why he did it. Boromir had said only that he needed something to keep his soul from drifting out of his body, because he feared he might fly too far from himself and not be able to come back, and his family needed him here. He had not met Imrahil’s eyes as he said it, and Imrahil had never asked again.

The lump on the bed lies still. Too still. Even when Imrahil sits gingerly on the edge of the bed, Boromir does not stir at all. Boromir who was never still, not even in sleep: too much energy in him, too hot a fire burning under his skin. And he was not asleep now. His breathing betrayed him. Too shallow, too measured, as one fighting with all his strength to keep silent. But when Imrahil reaches out to lay a hand over his brow, he flinches away. Buries his face in the sweat-soaked pillow so not a bit of him remains exposed to the air, as though the world were too much to bear unarmoured.

“Your brother fell asleep over his books,” he says quietly, drawing his hand back. Clenching it into a tight fist, pressing it hard into the meat of his thigh, letting the sting of it draw his mind away from the way his heart feels as though it were cracking in two. “Wonder Tales of Sea and Stone. I think they must have brought some wonder to his dreams, for he was smiling when I left him.”

“Good.” Boromir relaxes, just a shade. Ever the elder brother. Seeking reassurance of the wellbeing of the younger, heedless of his own. But there’s something faintly bitter in the word, muffled though it is. As though he begrudged Imrahil the knowledge that should have been his–or berated himself, that he had not been there to gentle Faramir into sleep himself.

“He said we ought to leave you be.” Never before had Imrahil felt himself so at a less. But never before had Boromir closed himself off so deep inside himself he could not be reached, either. “It can be our secret, that I did not heed him.”

Boromir breathes in, long and slow. Silent, but Imrahil watches the way his back heaves, beneath the mess of blankets. Watches the way it shudders a little, as he breathes out. “You should have.”

“He sees much.”

“More than anyone ought.”

The gifts of the blood of Númenor ran true in Faramir, as they did in Denethor. So, too, did the clear Sight of Mithrellas’ line, that Imrahil himself knew something of, that had so weighed on Finduilas’ heart. Boromir, as far as any of them could tell, had no such gift, no Sight, and Imrahil’s heart breaks for him, so caught between forces and powers he knew nothing of, except that they seemed a curse upon those he loved, with no power of his own to wield against them but the meagre strength of wretchedly mortal hands and heart.

“It is a gift of a hollow sort,” Imrahil says carefully, feeling as though he were but a youth again, new learning to swim, trying not to gasp as the seafloor fell out from under his feet. “A heavy burden to bear, yet it is a gift all the same.”

“It is a curse,” Boromir snaps. Fabric rustles sharply, crumpled between a suddenly clenched fist. Yet still he does not rise. “How can you of all people call it a gift, when I know you dream as Faramir does? Is it not enough he suffers to see in sleep what he cannot comprehend when he wakes, that he must dream of drowning, too, and a horror of a future he doesn’t even have the words to name?”

“And so you watch the nights out, that you might shield him from that horror?” Drawing in an unsteady breath, Imrahil carefully settles a hand over Boromir’s back, instead. Hoping the weight of it might prove a comfort, with enough layers between it and the boy’s skin not to chafe. “A lone soldier cannot hold a picket, lad.”

Boromir sighs, weary as a man four times his age, and curls in a little on himself. Defensive. As though he were tucking the soft heart of himself away, deep within where naught could touch it.

“Not all foes bear weapons,” he mutters through gritted teeth. “The least I can do for him is try.”

A boy’s voice. A man’s words. But Boromir had held a sword in his hand even before he could walk; had wielded that sword with skill far beyond his years before he could read. He knew his duty to his house, to his kin, to his land, better by far than he knew his own wants and needs, and he had not been a child since he had taken it upon himself to bear up father and brother both, blinding himself gladly to his own grief that he might better see and serve theirs.

Little wonder it reared up to bite him now. There was no shadow here to steal his sight.

“And what of you, sweet bear?” Imrahil murmurs, almost too low for Boromir to hear. “Who will try for you?”

Who will you let near enough that they might take you in their arms as you would comfort your brother, when your own dreams go ill? Who will you let see what you would bury within your heart as you bury your body now, shrouded and armoured so naught might touch you? Who will you let hold you, lest you forget you, too, are but human?

He cannot bring himself to speak. But the least he can do is try.

“It is no weakness, to grieve,” he whispers, holding himself stiff against the flood of tears that stream unbidden from burning eyes. He tastes salt upon his lips. Wishes, so much it hurts, that it were the salt of the sea. “To weep. Will you think your men weak, when they shed tears over their fallen comrades in arms, when the fever of battle drains from their limbs and leaves them trembling and raw like green squires again? Do you think your brother weak, when he seeks you out night after night, fearing the dreams that plague him? Your father, when he could not bring himself to rise from your mother’s side, even when the doors to the tomb would have closed on him? Your uncle, who weeps before you now? Why, then, call you it weakness in yourself? Is it not a sort of arrogance, instead, to hold yourself so far above every other person in your life, to whom you would extend such grace, to fall so much harder?”

Boromir lies silent for a long time. Long enough Imrahil thinks he must have overstepped; wonders, desperately, if he might have dropped into sleep at last. But all at once the boy uncurls himself just long enough to grab hold of Imrahil’s arm and huddle up close to it as he had not since he was but a babe, and Imrahil realises too late that he is sobbing: great, heaving cries, so hard he fears he might make himself sick with it, utterly silent. Weeping still himself, Imrahil shifts to lie atop the covers: curling up around Boromir, making his own body into a shield, that his nephew might finally cry, finally feel, without fear of the weight of eyes against his back. No longer upright, nor unbowed, that proud back. It had borne too many blows.

By the morrow he would stand tall again. Force himself to it. But just for tonight, he let himself be held.

Boromir’s nightmare was based pretty much beat for beat on a nightmare I had the night before I wrote the draft of this, although it was either a stranger or another manifestation of myself, not my mother, in the bed, and it took place in family home’s basement (so the cistern was a bathroom sink and we needn’t go into detail about what was clogging the pipes).

The process of writing this was absolutely CURSED: I handwrote about half of it in a park while dissociated as hell, then didn’t manage to write the other half for several weeks. I never wound up finishing the handwritten draft at all, and was resigned to winging the rest. Typed up the first half: I edit as I type, so much was added/changed from the handwritten text; this will prove significant. Brought my fanfic notebook to work yesterday (Friday), intending to type up the rest, and managed to do that, up to where I’d stopped writing. Amazing, I think to myself! I have a whole Friday evening free to finish it! Only to get home from work and realise that NOTHING of what I had typed during the entirety of the day had saved (I was typing it into a draft email in Outlook Web because that’s what I use for work, and this isn’t even the first time it’s happened, but I forgot to send the draft to myself because normally it Does succeed in auto-saving and I was banking on that happening this time). Because I hadn’t deleted the draft, I couldn’t recover it, so I’ve had to now retype the entire second half pretty much from memory. Fun times.

I stole the name of Imrahil’s wife (Idhreniel) from the_ocean_weekender’s fics; go check them out on Ao3, they’ve written some absolutely top-tier LotR fic.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

lookit mah art (fic) boi pt 1

Boromir Week Day 3: Thorongil

Written for Boromir Week 2025 (@boromir-week), for the day 3 prompt ‘Thorongil’ (as well as the day 2 prompt ‘son of Finduilas’). Hope y'all enjoy!

Read it on Ao3

“I forgive you,” Boromir says, just as grave as the captain before him, accepting his demotion to knighthood with far more grace than most would afford a too-bold babe. “An’ I dub you Sir ‘Rongil, so you must help protect nana. ‘Cos you’ve a real sword an’ can cut down real foes, until I have one, too, and can protect her better.”

So saying, he drives the point of the sword into the ground, and turns to face Finduilas, legs trembling a little with the effort to hold himself back from bouncing.

“No fear. No harm. Not while we’re here. So swear I.”

“So swear I,” Thorongil intones, after the fashion of the knights of old. Boromir turns back to him, taking both his hands to wrap them about the hilt of the toy sword, and for one selfish moment Finduilas is glad her son no longer faces her, that he might not see the tears spilling from her eyes.

The love that heals the wound (after the war is through)

“Nana, nana, look!”

The day had dawned clear–as clear as it could, at least, beneath the shadows of the Ephel Duáth with their ashen fingers clawing ever closer to Minas Tirith–for the first time that week, and though its rays were weak and pale, the return of the sun brought with it a surge of strength at which Finduilas rejoiced near as ebulliently as Boromir, who had drawn many a fond and as many a reproving eye as he chattered and squealed and jumped for joy the whole way to his mother’s garden. Though she had brought his little hand loom out with hers, she could not altogether blame him when he gave its strings but a cursory strum, as though it were a harp, before tearing away from her side to run about their little haven.

She made no move to hush him, nor bid him still, the way she knew his father and many of the household would have, thinking her too frail to manage his exuberance, his wild energy that made his grandfather Ecthelion shake his head in utter bemusement. Such spirit came not from his sire, nor from his mother, I deem, he would say to himself, with a measuring look in his eye, and to Boromir, when he begged his grandsire to roughhouse with him, he would lament, Too much for my old bones, boy. Too much for me.

They did not see how the creeping shadows drained her far more than motherhood’s honest toil ever could. Or mayhap they did, and chose not to mark it, and Finduilas could not think which was worse. How could she ever think him too much, her bright spark of a child who was so like to her, who warmed her heart with joy even in the depths of coldest night? How could she stifle him, dampen his spirit, dim his light, when this land of cursed stone would take him, and every other mother’s son with him, from her too soon, mould and carve and crush him into the shape it needed its Captain and Heir to be, with no care for what parts of him were lost to that need?

The spring wind tears through the clouds and the new leaves alike. Its constant rushing was a sort of music, one that soothed the restlessness that had built unto itself over the dreich and damp days like a stone upon her chest. Boromir had felt the same, she knew, fair flinging himself against the nursery walls to satisfy that need to move, and now he runs between the small birch trees, and threw himself into the soft grass, and struck out with feet and fists and the small wooden sword he only ever let go of to eat or bathe or sleep against invisible foes and hapless trunks alike, laughing and laughing until Finduilas could not help but laugh with him, feeling her heart overflow with warmth. What a blessing it was, such abandon, such joy, such life. What a blessing it was, to be here, sheltered from the shadows of the world, in this place of green and growing things with nary a creeping vine to choke them.

“What have you found, bear?” she asks, setting her own weaving aside. Brushing her fingers over her heart, as if that gentle touch had any hope of soothing the twinge of pain therein, a sudden melancholy for which she had no name.

Boromir hastens back to her side, plucking her hand from her breast and leaning forward to press his brow against it, instead. As though he could sense his mother’s hurt, though she spoke not a word, and sought to heal it, and Finduilas feels her breath catch in her throat.

“I found babies,” he says, tilting his head back to beam at her, tugging at her hand to bid her rise and bouncing up and down on the spot. His free hand flaps with excitement, taking wing where his feet could not, for he stayed staunchly by her until she rose, ere finally making to run towards a stand of birches, their leaves still reddish, half-furled inside their buds. “Baby trees, nana, come look!”

With all his strength, more than she had ever known in a child scarce two years of age, he pulls her towards his treasured find. But partway to the trees, he pulls himself up short, and tugs at her hand again, gently knocking his head against her arm until she bends a little to stand level with him.

“Keep mum,” he whispers (as much as he could, anyhow). Says it with just the same inflection as the stern Warden of the Houses of Healing, who would ever extort the young lord to be quiet when he accompanied Finduilas to visit the convalescents. Finduilas smiles, to hear it, and Boromir, taking that smile to mean she would not take him seriously, frowns. “We hafta be quiet, nana, the babies are sleeping. See? All tucked in.”

And he points to a little patch of athelas growing beneath the birches. Not yet in flower, its leaves not quite unfurled, and Finduilas has to press her lips together to keep from laughing, for with its white stems and saw-toothed, teardrop-shaped leaves, the precious herb does look rather like the trees in miniature.

“That is athelas, young Boromir,” a new voice says softly, startling them both.

Finduilas jumps. Gasps, a little, as she spins round, but before she can move Boromir has stepped in front of her, baring his teeth, and before she can make to stop him, draws his wooden sword.

“Back,” he growls, so like the bear she could call him in jest, a fierce scowl twisting his face.

A few paces away, Thorongil stops. Holds his hands out, palms up, so they both can see he holds no weapon. His sword is sheathed at one side, his dagger at the other, and slowly, holding Boromir’s gaze the while, he goes to one knee.

“In the common tongue,” he says, low and even, “it is known as kingsfoil. No weed, as many would deem it, but a potent medicine, made more powerful in the hands of those of the blood of kings. But you are right,” he adds, tilting his head a little to one side, lips curling up on one side in a way that tugged at the small, silvered scar cleaving them. “It does look very like the proud birches that stand guard over it. What a bright boy you are.”

Finduilas smiles softly at the captain, though he wore no armour now, no device of tree or tower. No captain now, then, but her dear friend. Only her friend, who had crept into the garden with his Ranger’s stealth, for she had bid him ever be welcome there.

“It is only Thorongil, bear,” she says, curling one hand into a fist to keep from resting it on Boromir’s back, for tense as he was then, he would surely flinch away from even a comforting touch. “He means us no harm.”

“He scared you!” Boromir protests hotly, sword never wavering, though he turns a little to catch her eye. Not enough, however, to lose sight of Thorongil, and Finduilas’ heart twists. Even so young, so dauntless before a foe. And something of her grief must show in her face, for Boromir sets his jaw, advancing on the kneeling captain, making as though to strike him, though he comes shy of actually making contact. A deliberate motion, and they both know it. “You scared nana, ‘Rongil, ‘twasn’t nice!”

“Nay, it was not,” Thorongil agrees gravely, bowing his head. “There, too, you are right, for fear is a kind of harm, as much as a blow from a sword.” Glancing up at Finduilas, though he keeps his head bowed, he adds, eyes twinkling, “Forgive me.”

“Promise you won’t do it again,” Boromir growls, before Finduilas can say aught, and he jabs the blunted point of his sword lightly into Thorongil’s chest. “Won’t scare nana. Won’t hurt her.”

Thorongil closes his eyes, just for a moment. When he opens them, the spark of mischief is gone, and in its place an earnest warmth burns, as he meets Boromir’s gaze unflinching. “I promise.”

Boromir, scowling still, studies him. He could never abide teasing, nor tricks, nor lies, and especially not false promises. Was so careful, even so young, never to make a promise he could not keep, and he expected everyone else to keep to just as strict a standard of honesty. And so many, too many, would not, or could not, and Finduilas feared for him. For the Council, damned vultures all, would eat him alive if he learned not the art and artifice of dissembling. Not that she doubted he could learn, in time, for he could less abide knowing he had failed at any part of his duty, and as much as he would hate it, as she hated it now, bandying words with vipers would form a great part of that duty. She only feared what it would do to him, how it would tear at him, to kill that part of his soul in which honour and justice burned as twin fires.

It was a sacrifice no man ought ever to make. But this was no place for men of honour to dwell.

But Thorongil had never reneged on any promise he had yet made to the boy, no matter how small. And Boromir knew it well, for he nods slightly, as if to himself, and when he raises his sword again the motion is gentle. Careful. Slowly, as he must have seen his grandfather Adrahil do, swearing in new Swan Knights, he taps Thorongil upon both shoulders, then atop his bowed head.

“I forgive you,” he says, just as grave as the captain before him, accepting his demotion to knighthood with far more grace than most would afford a too-bold babe. “An’ I dub you Sir ‘Rongil, so you must help protect nana. ‘Cos you’ve a real sword an’ can cut down real foes, until I have one, too, and can protect her better.”

So saying, he drives the point of the sword into the ground, and turns to face Finduilas, legs trembling a little with the effort to hold himself back from bouncing.

“No fear. No harm. Not while we’s here. So swear I.”

“So swear I,” Thorongil intones, after the fashion of the knights of old. Boromir turns back to him, taking both his hands to wrap them about the hilt of the toy sword, and for one selfish moment Finduilas is glad her son no longer faces her, that he might not see the tears spilling from her eyes.

He kept that sword ever to hand. Would never have let it get dirty, were he not so determined to perform this small ceremony correctly. Wore it buckled about his waist, small hands copying the motions Thorongil and the other guards had shown him with the fierce concentration he devoted to every task he took on, or by his bedside when he slept, the first thing he could touch if he reached out. Denethor noted it with pride, fair preened about it, though he harboured little patience for his son’s other strangeness: the way he could not sit still for more than a minute at a time, could not fix his attention on aught that did not demand at least some part of him to be moving, or else grew so absorbed in whatever task he had set himself to that to pull him away ere he had finished to his satisfaction would send him raging. But his boundless energy, the robustness that seemed only to laugh at pain if ever he marked it at all, the delight with which he studied and imitated the maneuvers of the soldiers he begged to watch at training whenever he could, though he had a year yet at least ere he would begin himself–aye, those things, her husband, and his father the Steward, would praise, seek to nurture. A strong son, they crowed to any and sundry. A born soldier. Gondor’s finest, sure to be, already with his duty firm in hand.

It sickened her. To know her sweet boy, who would fall over his feet in his eagerness to help even the lowest servant with their work, or to soothe any hurt, who greeted all he met with a beaming smile like the sun nigh-forgotten and knew their moods and private griefs better than his own, should be praised for, raised to, made for, not his kindness, but his killing blows. To know that soft body and softer heart would too soon harden with toil and grief. The bright flame quenched, tempered, as beaten steel.

But she could not stop it. Could not keep him by her side, not now nor in the years to come.

“My stalwart defender,” she whispers, and Thorongil smiles, soft and sad.

“May I embrace you, mîrig?” he asks, sitting back on his heels. Always asked, for though Boromir craved touch, he would shy away from it when it came unsolicited, not on his terms. There, too, he was like to her. Like to Thorongil, too, and so they would always ask. It was only right, and Finduilas thought everyone ought to feel the same, afford all the same consideration. Yet so few would ask. And fewer still would listen.

“No,” Boromir says, that fierce scowl he wore as often as the bright smile like sunlight firmly back in place, as he works the sword from the damp earth. “Not yet.”

And with great care, he steps to the side, so none might find themselves within range of the wooden blade as he works it back into his belt. Lays its child’s semblance of a killing point to rest, that he might not hurt his mother or friend.

“Now you may!” he chirps, the scowl giving way to the grin, as the clouds above them part, sunlight shining bright and true just for a moment upon his face as Thorongil draws him into a crushing embrace.

Just for a moment, Finduilas sees not her small son, nor her heart-friend, but the shades of the men they would grow to be. Thorongil with more lines upon his face, darker shadows in his eyes, but the slight pursing of his lips, the careful set to his brow, is just the same: the same reserve, the same gentle concern, the same love thorned with sorrow. And Boromir, her Boromir, hard-eyed and weary and noble and proud, shoulders bowed beneath a strain too great for any one man to bear, a strain she knew he would never let another move to help him bear, not wishing pain on any, face set in a stony mask like Death had touched him. But they both soften, just a little, in the vision’s embrace, weight and shadow lightening beneath the tender touch of another hand yearning to take it from the other.

Just for a moment, she sees it, as they hold each other, and just for a moment she presses her eyes closed. Wishing she had no Sight, to see what the years would do to them. Wishing she had never wished the sight away, for it was as much a gift as a curse, to know those nearest her heart would have some small comfort, to cling to in the hard years to come.

Finduilas opens her eyes. Thorongil has both arms wrapped about Boromir, still, but his eyes are grave, seeking out hers. And Boromir, sensing the way his attention strays, wriggles a little, working one arm free to reach out for his mother.

“Nana, hug,” he begs, butting his head up under Thorongil’s chin, and Finduilas’ heart cracks.

“Hug,” she echoes, smiling through her tears. And when she goes to join them on the ground, Thorongil’s heart beating against her back and Boromir’s hands upon her cheeks to catch those tears, she forces the visions from her mind, banishing them to the shadows the sun burned away, for in that moment, for the first time in longer than she cared to dwell on, she was whole.

I have Feels(TM) about these three. The base concept (baby Boromir knighting Thorongil), as well as the idea that Everyone Is A Flavour Of Neurodivergent, was pulled from a long-running RP with a beloved friend (HELLO YOU KNOW WHO YOU ARE AND WHAT YOU HAVE DONE /silly), and the protective instincts run strong and deep, I absolutely think his mother would’ve been the first person for whom he’d lay down his life. The loss on Finduilas, I think, was Boromir’s final break with childhood, and I like to think in part it’s because she was one of the only people in his life to give him the space and grace to actually be a child, to be himself in a way that he couldn’t be in any other sphere of life. If parts of that self are anathema to the desired image of a perfect son and heir, it only sharpens the prick of tragedy.

Ao3 title from Al Jarreau’s song After All: ‘And the love that heals the wound / after the war is through / is the knight in armour bright / faithful and true to you’

This one was written in a notebook smaller than my thumb while on a train, because I was struck by the urge to Write Words but didn’t want to use my notes app (it drains the phone battery like nobody’s business) and had forgotten to pack an actual notebook. Hope y’all enjoyed reading!

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok NYC there are no easy choices here, every mayoral candidate has serious character questions that should give anyone pause:

-one guy is a serial sexual harasser who killed your grandma

-one guy is a literal criminal who is cutting deals to sell out the city for pardons

-one guy stole a table

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Too many rich people buying medieval castles and then renovating the interior to look like a completely normal 21st century house. Sorry but if you're going to live in a castle you need to commit to the bit. If I lived in a castle I would restore it just enough to be barely liveable and pretend I was a poor but prideful nobleman in his crumbling estate, still clinging to the last vestiges of his family's fading name.

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

i didnt know you were allowed to do things for the sake of wanting to do things. i thought you were just supposed to keep that locked inside your ribcage and let it rot you inside out until youre limping around as the desiccated corpse of who you could have been

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

an author i love just tweeted about how “big joy and small joy are the same” and how she was just as content the other night eating chocolate and cuddling her dog as she was on her Big Trip to new york and honestly. i think that’s it. this morning i was listening to an audiobook while baking shortbread in my joggers and i realised i really didn’t care what Big Things happened in my future as long as i could keep baking and reading at the weekend and maybe that is the kind of bar we have to set to guard ourselves against disappointment. just appreciate and cherish the mundane stuff and see everything else as a bonus.

184K notes

·

View notes