Text

Well. Ten years since Cascade. Wild, huh?

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think you'll ever incorporate the classpects of the hiveswap characters into your analysis, or at least the aspects since they are confirmed?

I would probably have to play it first, and I’m not sure I still want to do that.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I figured it out after all

My new year’s resolution is to get the Tumblr app to start sending me notifications again

Spoilers: I’ve made no progress whatsoever

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

My new year’s resolution is to get the Tumblr app to start sending me notifications again

Spoilers: I’ve made no progress whatsoever

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey, I was wondering if you'd mind asks about your classpect theories? About things that I'd like elaborated or questions I have? I understand if it's a just for fun thing and you're not up to answer things ✌️

Go for it. Theory posts are pretty much the whole reason this blog even still exists.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classes and aspects from top to bottom

At the request of a certain person, this is a summary of my theories in one giant post, including stuff I previously wrote in notebooks or said in private conversations. I’ve tried to keep it clear, yet brief. A lot of my reasoning is abridged. Most examples and evidence are simply left out.

General approach

The title system became a visible part of the story in Act 3, but serious speculation only took off in early 2012 with Act 6 Act 2. Since that time, the discussion has been dominated by two general approaches. The first, which I’ll call Model A, defines titles strictly as the means by which players get “flashy powers” and concerns itself with how those powers differ. This approach was specifically refuted in canon, prompting the development of Model B, which still defines titles as a means by which players obtain power, but interprets “power” in a slightly more abstract way. Almost all class and aspect guides and quizzes currently derive from Model B. Model A persists as its main competition (and main source of criticism) despite being essentially debunked.

The theories I describe here operate under a different approach, which I’ll call Model M. It defines the title system primarily as a tool for writing distinct characters, even in a story with a gigantic cast, and for building a story around them. The flashy powers seen in Homestuck are totally secondary to these functions. They can do essentially anything the plot demands. As long as the plot remains sufficiently character-driven, they will be thematically appropriate to the characters who display them. Characters who lack superpowers can still have titles. The rules of the title system apply to other stories, and can be used to analyze them, but this does not extend to superpowers, since writers other than Hussie would almost certainly invent powers according to a different set of themes.

Classes mainly govern the habits and actions of a character. In addition to physical motions that impact the direction of the plot, these also include habits of thought, speech, and social interaction. Hussie has been praised consistently for his ability to create and maintain distinct voices for different characters. He accomplished this in part by developing a system to track subtle differences in how each character thinks and speaks. We can see it in action by comparing characters of the same class. For example, if we swap upper and lower case in a conversation between Dave and Karkat (both Knights) we can see uncanny similarities between their mannerisms that aren’t shared with most other characters, even accounting for Homestuck’s deliberate and frequent reuse of sentence structures.

Aspects mainly govern the values and worldview of a character. These include their understanding of the fundamental rules of reality, and their personal definitions of concepts like good and evil (if they believe in such things) that they tend to consider factual and immutable. Any such beliefs can be completely mistaken. Characters of the same aspect tend to have the same preconceptions, and characters of paired (or “opposite”) aspects tend to have opposite preconceptions. A common pattern we see in Homestuck (but not an ironclad rule) is for characters to be confronted by their mistaken preconceptions, gain maturity by overcoming them, and then end up with powers that work as if their old beliefs were accurate. See Terezi’s comment about how “we’re all crazy.”

Lunar sway (affectionately “moon wiggle”) is a Homestuck-specific hint about the difficulty curve a character faces as they grow into their title. Each of the two moons (Derse and Prospit) influences certain personality traits which may be treated by each class or aspect as either a weakness or a strength. The details are unclear, but I discuss some of the interactions below.

The granularity of the title system seems very well suited for character creation. For comparison, the Hogwarts hat system can only describe four personality types; the D&D alignment system, only 9; and MBTI, only 16, all with boundaries that are vague at best. With 12 aspects and 14 classes, the title system can comfortably describe 168 personality types, even assuming no variation between characters of the same title. This is slightly higher than Dunbar’s number (150), a commonly cited estimate of the maximum number of social relationships that an average human being can maintain. To put it another way, a writer could (theoretically) use each title exactly once and still create a cast as convincingly varied as the set of all the people the reader knows in real life.

Combining a class and aspect into a title does not automatically make a character. Rather, a title provides a writer with a block of material from which a character can then be sculpted. Just as lunar sway can contradict any part of a title, any title will contain countless possibilities for contradictions between class and aspect. By exploring these contradictions, focusing on some over others, and finding ways to balance them or make them interact, a writer can create unique challenges for a character that are thematically consistent with the rest of their personality. For example, a character might value physical might (due to his aspect) but procrastinate rather than work out (due to his class), so that his self worth suffers. This then might cause him difficulty with tasks that wouldn’t otherwise be an issue, or prompt coping mechanisms like boasting or denial. If he finds a new way to express his title without this contradiction, he overcomes some of his problems and grows as a person. A skilled writer should have no trouble developing a combinatorial explosion of growth challenges for the entire cast.

Note that many writers can create a rich, varied cast without the use of a character creation framework. By the same token, many writers don’t bother, since the audience can’t necessarily tell the difference. An introspective novel might showcase only one aspect (that of the protagonist), while a Hollywood action movie might portray only one or two classes (eg. Heir and Maid) that we’ve seen a million times in all the other movies. Our ability to view other stories through the lens of the title system depends on the capacity of the storytellers to portray characters with sufficient depth and consistency. The same character might read as different titles between different adaptations of the same story, or from prequel to sequel, owing to a change in actors, directors, editors, and obviously writers. See the “Han shot first” controversy in the Star Wars fandom.

Analyzing any character’s aspect can be difficult without extensive access to their private thoughts. A character might monologue, but this itself is an action, meaning we have to account for their class. Furthermore, characters can embrace some “facets” of their aspect while rejecting or ignoring other parts. They almost always understand some parts better than others. They may even reverse their own progress, going in circles while trying to satisfy the demands of both their aspect and their class. Fortunately, Homestuck gives us a wealth of hints about aspects in the form of characters explicitly discussing the weird laws of nature, magic, and society that got them where they are. They contradict each other all the time, like two people seeing the same glass and arguing over whether it’s half empty or half full.

Aspects can be analyzed as having central themes, plus facets that “apply” those themes to different conceptual domains. In the case of some aspects, we are told the central theme, such as Time’s theme being “inevitability.” In some others, we are only told about a small sample of facets and must infer a theme; and in the worst cases, we must infer all themes and facets from a small handful of ambiguous observations. We can rely somewhat on reasoning by analogy: Any domain visited by one aspect should have corresponding facets from all the others.

Many theories assign two aspects the same theme and many of the same facets, and only distinguish them from each other by different rules for their flashy powers. Model M does not permit this whatsoever. If two aspects have the same theme (which would imply they yield the same personality traits) then they are the same aspect. If they are not the same aspect, they must differ in theme. Likewise, where many theories focus on abstract concepts and inanimate objects as symbols of an aspect, Model M forces us to include interpersonal interactions in the analysis of every class and aspect. Such actions comprise the overwhelming majority of all plot points in all stories, and Homestuck is no exception.

Classes can be analyzed as an expression of a verb, or method. Each method yields exactly two classes that differ only in their passivity (+ for passive, - for active). A difference in passivity is just as important as a difference in method, by the same logic as aspect themes above: If two classes were defined by the same behavior, they would be the same class.

Model M places several restrictions on what methods we can propose. First, they must describe actions that can be performed intentionally, not just the outcomes of such actions: “Search” and “listen” are more appropriate than “find” or “hear.” Second, they must be doable in some sense using bare hands, thoughts, or spoken words: “Push” is more appropriate than “imagine” or “vaporize.” Third, they must be distinct from other methods in both active and passive reflex: “Change,” “use,” and “exploit” are all useless, since they encompass almost anything any character can do. Finally, words that suggest personality traits are preferable to words that don’t. Model B theories often replace “steal” with “redistribute” as if to suggest that all fictional characters have equal regard for the law. We should avoid repeating that mistake.

The active/passive distinction works uniformly across different methods; if a contrast is valid for one pair of classes, it should be valid for all others. The contrasts are numerous: Proactive/reactive action, offensive/defensive combat roles, internal/external aspect expression, self-oriented/team-oriented goals, and so forth. From observation and discussion, I add reflexive actions directed towards oneself (eg. a Thief “stealing” from herself) vs. reciprocal actions exchanged amongst members of a group (eg. a Rogue stealing something, having it stolen from her, and seeing it passed around like a game of hot potato).

Classes are not purely active or passive. Each falls somewhere on a sliding scale, depending on which markers are most compatible with its method. Even a single action can measure as active in one respect and passive in another. For example, a Rogue can be simultaneously selfish and reactive, and some other class might be altruistic yet proactive while taking an offensive combat role. Aspects have a smaller influence on a character’s expressed passivity. Lunar sway may have a larger one: Derse players and Prospit players tend to be respectively more active and more passive than their classes suggest.

Note that some theories interpret “passive” as “inactive” (ie. taking no action at all) or “more active” as “stronger in combat.” Both of these interpretations have been thoroughly refuted.

Specific claims about classes

The canon method for Thief and Rogue is “steal” and the canon method for Prince and Bard is “destroy.” The characterization of these classes is worth reviewing briefly.

A Thief is clever, short-sighted, and unscrupulous. She cheats to get ahead using forces outside her understanding or control, and has trouble realizing that stealth would serve her better than violence. A Rogue, meanwhile, is generous to a fault. She has such a habit of repressing her own wants and needs that she barely registers ordeals that would ruin someone else’s day. Both classes lie as easily as they breathe. Both live by words like “fake it ’til you make it” and have a lot of trouble remembering the second part.

A Prince is obsessive and calculating. He studies his opponents’ weaknesses and leads them into the perfect ambush. When he can’t satisfy his need to constantly outdo himself, he melts down and becomes completely useless. A Bard is useless by default. He’s standing right there when things go sideways, but it’s not actually his fault, because he doesn’t even understand what’s going on… or does he? Both classes punch so far above their weight it’s unfair. Both get wrapped up in insanely risky master plans that fail as spectacularly as possible.

Bards are rarely the angry menaces that the fandom portrays them as. The loudest and most aggressive classes are typically Lord, Knight, and Thief, in that order; Bards barely register. While the Thief is prancing on tables, cackling and lighting fires, the Bard is just standing around, minding his own business. Nobody even hears him say “Whoa, what does this button do?”

From canon observations, I have proposed “guide” for Seer, and “serve” for Page. The latter has been especially contentious among Model A and Model B adherents, but Model M embraces the concept that methods can have double meanings just as “active” and “passive” do. On top of the obvious meaning of allying oneself to a cause, I like to suggest visualizing “serve” as the physical act of throwing or shoving unwanted stuff in people’s faces. Pages, throughout their development, are characteristically the recipients of difficult truths they aren’t ready to face, and expectations they don’t know how to live up to. Those who overcome such challenges can lead armies. Thus, I read Page as passive (being served) and Knight as its active (self-serving) counterpart.

We have plenty of exposition on how exactly a Seer works. Her role is essentially to steer the party away from risks and into safety. Hussie confirmed early on that Seer is passive, and we are shown many times that to succeed in her party-guiding role, she relies on her party members to guide her in turn. She doesn’t know everything; she just asks the right questions.

Most theories tag Mage as the corresponding active class. I find, however, that Mage and Seer are a very poor match. Mages are risk takers who experiment with their aspect for the sake of trying new things. They sometimes gain knowledge as a side effect when their experiments blow up in their faces. This seems to work for them. If they were really the active counterpart of Seers, I would expect them to make self-preservation a very high priority (ie. steering oneself to safety), take more of an interest in “common sense” than forbidden knowledge, and not suck so much at explaining things with their words. A far better fit for that description is the class second-most-closely associated with the word “guide” — the Maid.

Outside of Homestuck, the most common role for Mage-type characters is as quirky mentor figures who go their separate ways after blessing the actual heroes with a tiny bit of wisdom or a secret technique. Slightly less common is the wizard/monk/scientist who goes around inventing his way out of trouble and occasionally having moral quandaries about whatever he just did. Both variants have a tendency to kick the bucket (or at least look like they did) only to come back miraculously with weird powers from beyond the grave. I unite all of these patterns under the verb “sacrifice” and read Mage as the active sacrifice class.

I identified Witch and Sylph as a class pair, and had a clear mental image of how they worked and were connected, long before I found words to describe them. Eventually I took the verb “summon” from careful rereading. There are two especially important (though seemingly opposite) meanings: Retrieving something from a hidden place to put it on display; and capturing something to bring it under one’s control, eg. by putting a leash on it. A Witch is a deeply wild person with a bottomless appetite for her aspect, as well as a magnetic charisma through which she brings others under her sway. She empowers herself both by leveraging her underlings and by developing greater control over the talents she already has. A Sylph, meanwhile, has a delicate balancing act to maintain. She can cut loose as the party animal from hell, plunging the world around her into chaos, or she can conceal these wild urges with Proper Conduct, and become so uptight that nobody can enjoy anything in her presence. This act is as frustrating for her as for those around her, and without some kind of release valve, she tends to explode.

The Heir represents such a commonly used archetype that I almost get bored trying to describe him. He is a regular guy, a nobody, and then a crisis happens. He runs into danger and saves people not because he knows what he’s doing, but because it’s what anybody would have done. In fact, everything he does is what anybody would have done. He’s supposed to be the blank slate character that anyone can relate to, the hero defined almost wholly by his heroism. The Heir is the Mage’s counterpart, the passive sacrifice class.

It is implied that Lord and Muse, the “master classes,” are an active/passive pair, but not specifically stated what their method is. My proposals include the verb “master” more as a placeholder than a serious suggestion. Characters of both classes are more common than they seem. A Muse is at the center of everything, trapped in one cage after another, prevented from doing much of anything herself, yet under immense pressure to resolve the entire plot. A Lord is under similar pressure, but by his own doing, because he just does whatever he wants and puts himself in a position of power by throwing his weight around. Both are so busy, it seems like they never sleep.

Before I move on, some notes on gender: I tend to use the “default” pronouns for each class, because all of them (and all aspects, for that matter) go hand in hand with personality traits that western culture reads as masculine or feminine. However, I’m convinced that none of the classes are really gender-exclusive, and my example set includes characters I read as female Princes and male Witches.

Specific claims about aspects

The twelve aspects are arranged in pairs that represent opposing forces in the weird dynamics of paradox space. Both this principle, and the pairs themselves, have been confirmed many times over. However, the logic behind the pairings resists analysis under both Model A and Model B.

Early theories often failed to anticipate the canonical pairings. For example, when speculating about Doom, they tried to pair it with Hope (contrasting optimism vs. pessimism) or Light (contrasting “good” fortune with misfortune). These pairs try to unite “opposing” players under the same worldview, so that they reign over opposite ends of a single scale operating by a single set of rules. Under Model M, however, we find that the players’ mental processes themselves must be as different as possible (and thus represent rulesets as different as possible) in order for their aspects to form a pair. For example, whereas Hope players constantly get lost in thought about an idealized future, Rage players seem to reject both thought and ideals altogether. They instead perceive reality as raw sensory input, and react to it impulsively without reasoning about their actions. Viewed through this lens, Hope and Doom are more alike than different: They both prioritize expectations over observations of reality.

I see this dichotomy in every pair. Here’s a breakdown assigning “O” or “E” labels to all twelve aspects:

Rage (O) and Hope (E)

Life (O) and Doom (E)

Void (O) and Light (E)

Blood (O) and Breath (E)

Mind (O) and Heart (E)

Space (O) and Time (E)

(This list is otherwise unordered. I would have liked to arrange it according to some kind of sliding scale, but I’ve never found one that actually worked.)

Previously, I’ve described these concepts in other terms. If you’re surrounded by piles of philosophy books, you might read “O” aspects as those espousing metaphysical materialism, and “E” as metaphysical idealism. If you’re a literary critic you might instead say that O aspects are concerned with Watsonian logic, and E aspects with Doylist logic. In Homestuck, concepts like these blend together as confusingly as possible, with the added wrinkle of lunar sway, which seems to nudge players towards either O (Derse) or E (Prospit) regardless of what makes sense for their aspect.

Now, for a really fun ball of cats to untangle, look at aspects from a theological perspective: “Aspect” is then short for aspect of divine presence, so that each one is a different type of evidence for divinity. A Heart player just “feels” that the gods exist, but a Mind player explains it clearly with a bulletproof logical argument. Time players see a divine plan controlling all of history; Doom players are trying to figure out whether they’re going to hell. Blood players stand on the battlefield and scream “God is dead,” and ascended Void players turn invisible because they don’t believe in themselves. As for Light players, of course they see literally everything that happens as a personalized message about how important they are.

As eye-opening as this explanation might be, it’s also fiendishly self-obfuscating in a story where the heroes run around committing apotheosis. We don’t have to go quite that far. The names of the aspects are fairly common words that appear in numerous English-language figures of speech, and we can gain some insight just by listing those. For example, here are some common “blood” idioms that other theories tend to overlook:

Blood from a stone: An impossible or frustrating task

Blood sport: A fight to the death for entertainment purposes

Blood feud: Ongoing hostility or conflict between clans or families

Bloodbath: An incident involving extensive violence or death

Bloodlust or bloodthirst: Murderous or violent intent

Out for blood: Attempting murder and/or revenge

Bloodstained: Guilty of murder or wrongdoing

Blood players think in such terms. They see the makings of harm and violence wherever they go, and weigh decisions in terms of what’s worth killing or dying for, because life is just fucking hard. They’re difficult to get along with on a good day, and their trust is not easily earned, but those who earn it receive their ironclad loyalty. Breath players, meanwhile, are the type that can instantly get along with anybody, but abandon relationships as easily as they create them.

Many theories get hung up on Life and Doom as literal life and death, forcing themselves to ignore the death symbolism that crawls all over Time players like locusts munching on their leather jackets. As much as the comic likes to leave us in the dark, it makes some things clear: Time is the aspect of the inevitable end, and Space is the aspect of beginnings, birth, motherhood, and all the growing things in nature. (Yes, even plants.) What the Life aspect revolves around is how to handle day-to-day situations. It addresses death by including it in the cycle of life: These things happen, they’re normal, and life goes on. As for Doom, it deals in scary prophecies that are only useful precisely because they are not inevitable — which also means they can be wrong, and that by itself is a great reason to run around screaming.

A final note

I’m wrapping up this post on the same day Homestuck 2 begins. I've left a lot out. At this time of writing, I have not read the epilogues, and I definitely haven’t seen what the sequel will bring. Much of this post is liable to end up debunked, but to me, even a wrong analysis has been worth it, because it helped me slay an inner demon that tormented me for years. I am easily twice the writer I used to be.

Let’s see where we all go from here.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m getting a lot of anon messages today.

How did you all know.

I will find out who’s responsible for this.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The original post is six years old

I don’t even know how anybody found it but it’s almost doubled its note count in the past week

A brief, incomplete, and mostly right summary of Homestuck

Some people hate Homestuck because they think it’s about a boy who just stands around in his bedroom. I will not try to tell these people that they are wrong, but at least with my help they can easily lie to their friends by pretending that they have actually read Homestuck and enjoyed it.

Here are some choice plot points from acts 1 through 6, in no particular order:

Mark Twain is killed by a newborn baby dual-wielding flintlock pistols

Somebody chops a meteor in half with a sword

One of the villains builds a tall building full of staircases just to torment a guy in a wheelchair

About 90% of the characters are time travelers

Somebody attacks a planet by dropping a moon out of orbit

A video game destroys all life on Earth

One of the characters makes Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff

Charles Dutton can see into the future

A god shows up and literally juggles a bunch of planets

A Prohibition-era mobster plows through a wall Kool-Aid Man style

The whole universe blows up

A completely different universe also blows up

The author jumps into the story and engages in melee combat with the devil himself

The creators of the universe track down the main characters to scream at them over the internet

Betty Crocker lands her alien spaceship on Earth

There are dinosaurs

I apologize for how much was left out of this summary. By the time it reaches completion, Homestuck will be longer than Leo Tolstoy’s famous novel War and Peace. If anyone wants to try writing a better summary, I wish them luck.

7K notes

·

View notes

Note

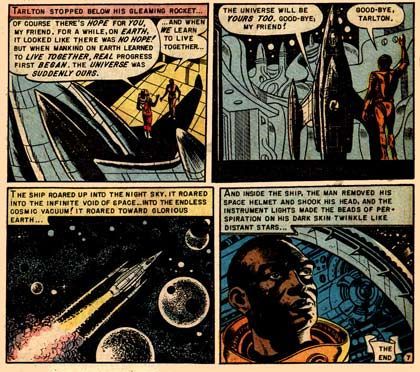

oooh have you ever done a post about the ridiculous mandatory twist endings in old sci-fi and horror comics? Like when the guy at the end would be like "I saved the Earth from Martians because I am in fact a Vensuvian who has sworn to protect our sister planet!" with no build up whatsoever.

Yeah, that is a good question - why do some scifi twist endings fail?

As a teenager obsessed with Rod Serling and the Twilight Zone, I bought every single one of Rod Serling’s guides to writing. I wanted to know what he knew.

The reason that Rod Serling’s twist endings work is because they “answer the question” that the story raised in the first place. They are connected to the very clear reason to even tell the story at all. Rod’s story structures were all about starting off with a question, the way he did in his script for Planet of the Apes (yes, Rod Serling wrote the script for Planet of the Apes, which makes sense, since it feels like a Twilight Zone episode): “is mankind inherently violent and self-destructive?” The plot of Planet of the Apes argues the point back and forth, and finally, we get an answer to the question: the Planet of the Apes was earth, after we destroyed ourselves. The reason the ending has “oomph” is because it answers the question that the story asked.

My friend and fellow Rod Serling fan Brian McDonald wrote an article about this where he explains everything beautifully. Check it out. His articles are all worth reading and he’s one of the most intelligent guys I’ve run into if you want to know how to be a better writer.

According to Rod Serling, every story has three parts: proposal, argument, and conclusion. Proposal is where you express the idea the story will go over, like, “are humans violent and self destructive?” Argument is where the characters go back and forth on this, and conclusion is where you answer the question the story raised in a definitive and clear fashion.

The reason that a lot of twist endings like those of M. Night Shyamalan’s and a lot of the 1950s horror comics fail is that they’re just a thing that happens instead of being connected to the theme of the story.

One of the most effective and memorable “final panels” in old scifi comics is EC Comics’ “Judgment Day,” where an astronaut from an enlightened earth visits a backward planet divided between orange and blue robots, where one group has more rights than the other. The point of the story is “is prejudice permanent, and will things ever get better?” And in the final panel, the astronaut from earth takes his helmet off and reveals he is a black man, answering the question the story raised.

89K notes

·

View notes

Note

2classpect4this is an owl?

Wiser men than me still cannot answer such a question

1 note

·

View note

Note

Are you familiar with 2claspect4this' analyses based on your theories?

Yeah we go way back the guy’s a hoot if you know what I mean

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

if two dudes were on the moon

And one of them said “your waifu a shit”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got around to updating my spooky web novel with lots of skeletons

I should probably use some kind of actual chapter theme for this nonsense so people can read with "next" and "previous" links

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It begins

EDIT: Nothing happened

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Driving with class

A few months ago I posted an aspect "test" that made some of you laugh. Here's the other half of it: A class "test" based on the way people drive.

Lord: Honks and screams throughout his two hour commute. Randomly floors the gas pedal or slams the brakes. Cuts people off without signalling. Bribes and blackmails his way out of speeding tickets. Has a vanity license plate that reads "NMR1 BOSS."

Witch: Hauls scrap metal in a flatbed truck with an engine she's rebuilt five times. Sings and dances to rap and country while waiting in the drivethru. Pulls over sobbing uncontrollably after seeing a dead deer on the side of the road.

Prince: Weaves in and out of traffic. Tailgates people who won't let him pass. Drifts into a U-turn at full speed while sipping a latte and booking plane tickets on his phone. Never wears a seatbelt. Never looks in the rear view mirror except to fix his hair.

Thief: Pulls up behind you and leans on the horn just as the light turns green. Speeds past you on the wrong side of the road to beat you to the next red light. Opens her sunroof so she can give you the finger. There are no other cars on the road.

Knight: Stays up late restoring his '67 Mustang. Revs the engine loud enough to wake the entire neighborhood. Wears eleven different Mustang T-shirts in rotation. Joins conversations just so he can change the subject to Mustangs. Rides the bus to work.

Maid: Pulls over to ask a stranger for directions. Gets upset that their explanation was insufficiently clear and spends the next half hour lecturing them about interpersonal communication. Owns a GPS. Has no idea how to use it.

Mage: Wanders around back roads for two hours looking for a shortcut. Gets lost while daydreaming about Pokemon. Has fuzzy dice on the rear view mirror, an anime figure on the dashboard, decals on the hood, and a bumper sticker that says "my other car is a cdr."

Sylph: Shows up unannounced to take you to the farmer's market. Buys exactly one sweet potato. Decides, upon dropping you off, that the sweet potato belongs to you. Remains in your driveway with her engine idling and balances her checkbook.

Rogue: Drives a 1986 Toyota with missing wipers, missing seat cushions, two burnt out taillights, a broken muffler, a huge crack in the windshield, and a radio stuck on a Spanish-only news station. Doesn't speak a word of Spanish. Sleeps in the back seat with the garbage.

Heir: Heads down the road at a normal speed like a normal person. Notices you standing on the curb. Stops and waits for you to cross. Rolls down his window to smile warmly and tell you he hopes you have a nice day. You've never met this guy.

Seer: Takes a taxi. Breathes in sharply when the driver forgets to signal, speeds up to catch a light, or gets within ten feet of another car. Keeps asking if they're lost. Can't understand the driver's accent and constantly asks him to repeat himself.

Bard: Drives in the fast lane at half the speed limit. Cuts across three lanes of traffic with his left blinker on to get in the right lane. Misses his exit. Shifts into reverse to go back to it. Parks in the wrong driveway. Falls asleep at the wheel with the engine running.

Page: Gets a used Volkswagen with the steering wheel on the wrong side. Doesn't understand what the clutch is for. Stalls the engine at every stop sign. Learns to parallel park just so he can stay out of the parking garage.

Muse: Owns three thousand pairs of roller skates. Never leaves the house.

509 notes

·

View notes

Text

god this campus (where there’s no excuse for anything to happen) and this city seem so lively and intense, even (especially) compared to Concordia (it doesn’t feel like “fun” just means increasingly esoteric and refined alcohol and drug combinations to these people) - I almost feel like Momus visiting Korea from Japan (cool clothes and Kpop everywhere really round out this analogy)

it will feel like a huge waste of spoons if I spend the rest of my year only interacting with the post-Protestant white beardmonks in my program

I know I should have had this phase in undergrad but I am 22, is that too old to do something other than the kind of low-investment cuddly Netflix-heavy Adulting everyone in my social circles seems to be retreating into? because if so fuck off to everyone who talks about “prolonged adolescence” tbh

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

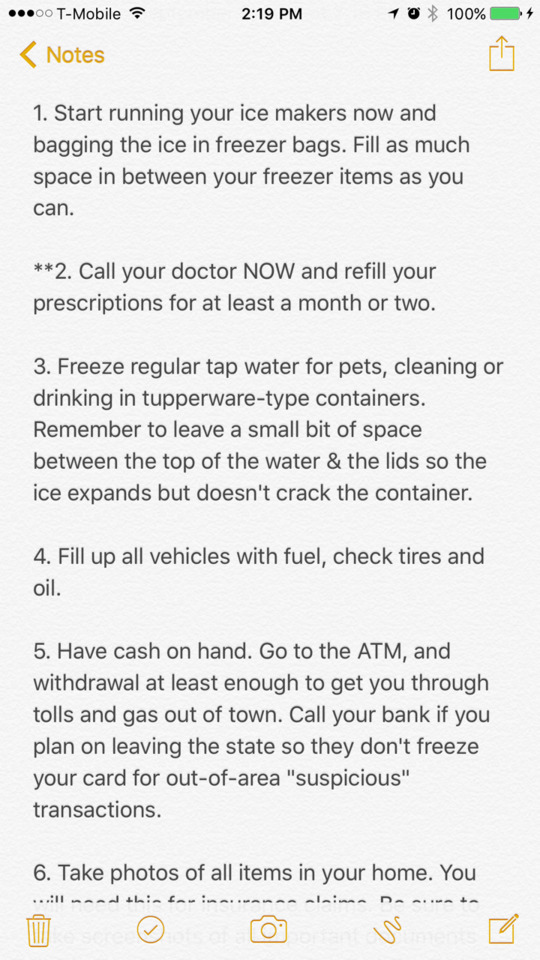

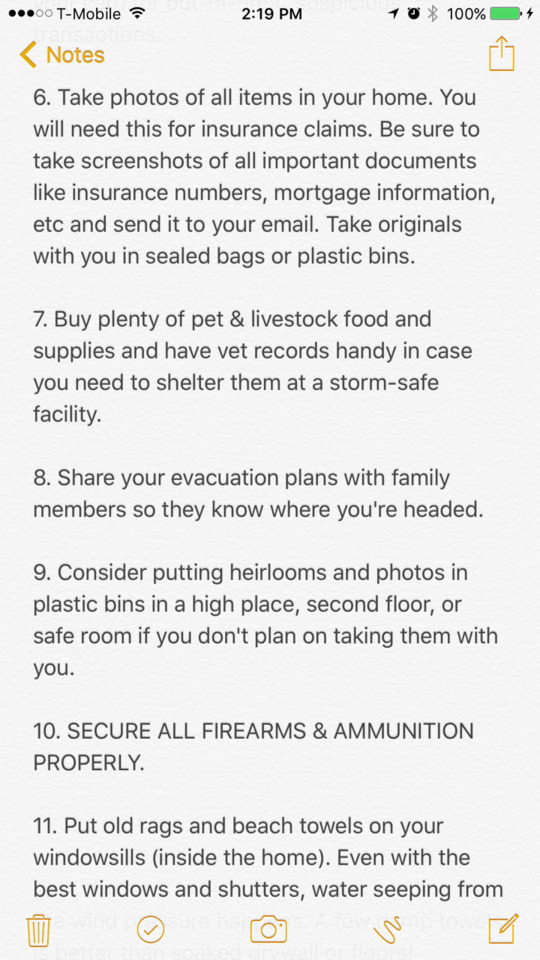

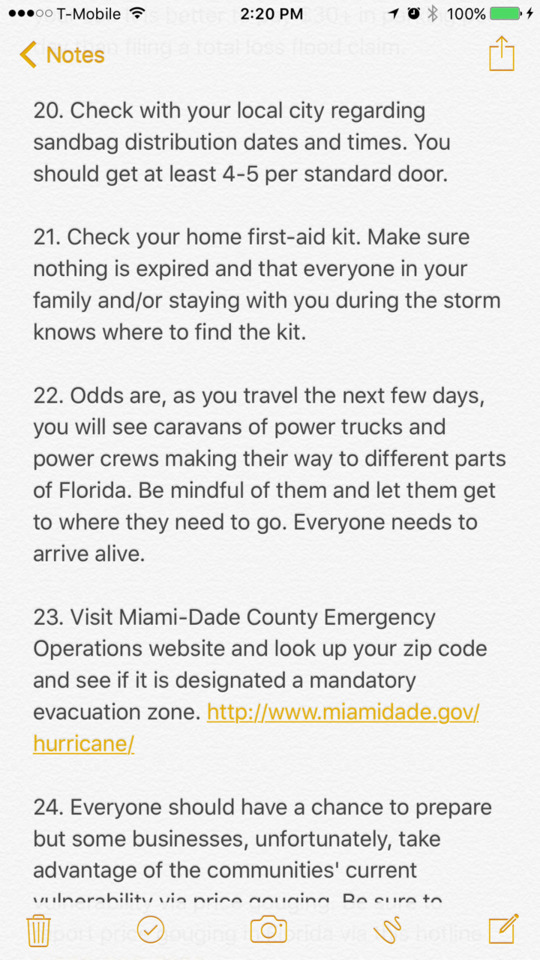

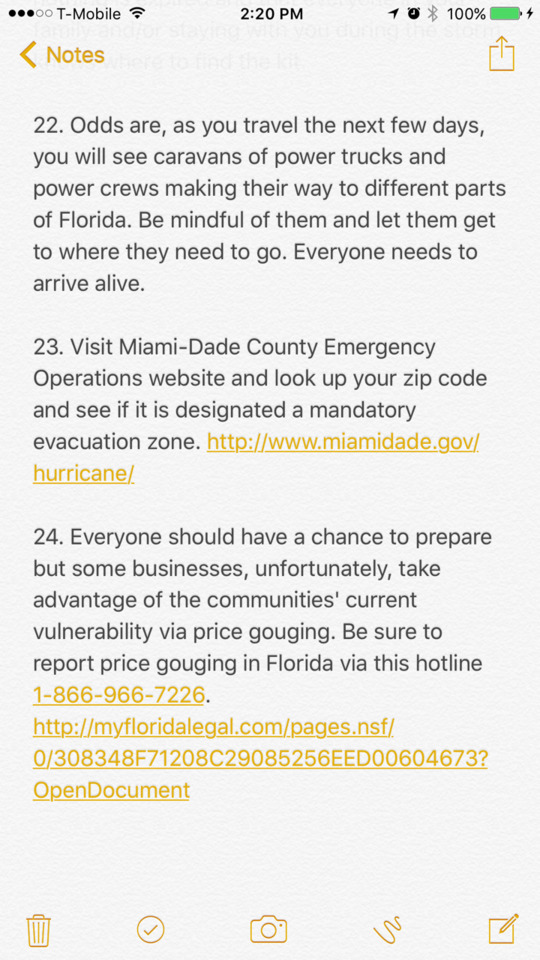

TIPS FOR HURRICANE IRMA. STAY SAFE MY FLORIDA FRIENDS! Gas prices are already up to $3 and water is hard to find until new deliveries come in. I have to drive much farther out for supplies.

77K notes

·

View notes