Text

#trump's attempted coup against democracy#trump the tyrant#this is why character matters#being a good person#more than ideology#trump's egotism was always corrosive#to the entire constitutional order#it's just that it's finally coming out into the open#now that he has nothing to lose

42K notes

·

View notes

Text

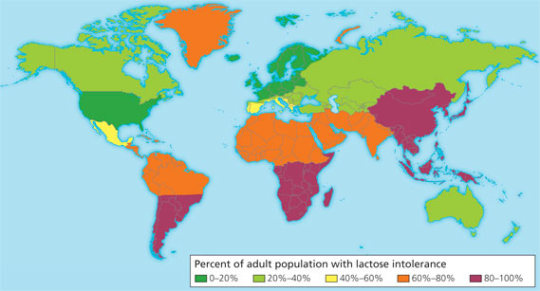

omg why do white ppl love cheese so mu-

291K notes

·

View notes

Text

to my friends in red states, please stay safe and watch out for each other. stay inside and avoid going out if you don’t need to. not to stir up fear in the wake of victory, but there are numerous watchdog organizations warning people — especially black and trans folks — to expect a sharp uptick in violence and tension. the naacp has issued a warning to black people in missouri to STAY INSIDE, STAY TOGETHER, STAY SAFE. check on your friends. stay informed. if you aren’t following them already, check out the naacp website and watchdog organizations to keep an eye on things in your area.

to white folks, this is a time for you to celebrate as well, but things are far from over. reach out to your poc and trans friends, particularly your black and trans friends, and check on them and make sure they feel safe. DO NOT STOP DONATING TO PAYPALS AND GOFUNDMES. CONTINUE SHARING RESOURCES AND INFORMATION. CONTINUE PARTICIPATING IN COMMUNITY AID. electing biden did not simultaneously wipe out the issues many marginalized communities are facing. YOUR PART IN THIS IS NOT OVER BECAUSE THIS FIGHT IS NOT OVER. continue spreading

to succinctly sum up the energy we need to cultivate going forward:

you can reblog this. white people can and should reblog this. likes do nothing for us.

34K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Dallas police was acting as an agent provocateur and leaving bricks out.

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

THE PRESIDENT HAS ANNOUNCED MATRIAL LAW. POLICE WILL BE MORE AGRESSIVE. MILITARY FORCE WILL BE USED AS THREATS.

WE ARE IN DANGER. STOP BEING SILENT FOR TODAY. SPREAD THE NEWS, TELL YOUR FRIENDS, DONT TRUST EVERYTHING THE MEDIA TELLS YOU, STAY INSIDE AND MOST IMPORTANTLY;

STAY SAFE.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

If you are someone who likes to watch a lot of cop shows, I want you to ask yourself a few questions.

Why do all TV cops, even the good ones, hate Internal Affairs? Isn’t the job of Internal Affairs to root out the “bad cops”? Isn’t their job to make sure police follow the rules? Why is that presented as inherently evil or antagonistic?

Why do all TV cops, even the good ones, hate defense attorneys? Isn’t the defense attorney’s job to protect the rights of all citizens? Isn’t it their job to make sure police follow the law? Isn’t it their job to make sure everyone is treated fairly under the system? Why is that presented as inherently evil or antagonistic?

Why do all TV cops, even the good ones, get upset when citizens invoke their constitutional rights? Don’t those rights exist to ensure all citizens are treated fairly? Don’t they exist to ensure innocent people are not wrongfully incriminated? Why are citizens who invoke their rights presented as dishonest, untrustworthy, or antagonistic?

To be clear, I’ve watched Brooklyn 99 and enjoyed it. I was watching Elementary the other day. But even when I watch shows I like, I make a mental note every time a cop lies, breaks the law, subverts someone’s basic rights, or just generally acts like an asshole to the people the are meant to serve and protect.

How often are they called out on their behavior? How often are they punished for it? How often is it reinforced as correct by the narrative?

When I tell people to be critical of the media they consume that is what I mean. Not simply calling it terrible and moving on, but actually engaging thoughtfully, asking questions, and forming conclusions about what that media is trying to say to you. Then decide whether you want to keep listening, or if it will be better for you in the long run to move on.

111K notes

·

View notes

Text

this is fascism.

trump is threatening to kill the protesters in minneapolis. he is publicly encouraging violence against them.

this is fascism.

trump is attempting to shut down twitter for fact checking him.

this is fascism.

trump and the gop are trying to stop mail-in voting during a global pandemic. they’re trying to make it harder for people to vote.

this is fascism.

cops at minneapolis arrested a cnn crew on live air for reporting on the protests. even though the crew complied with the cops’ directives and gave their reporter credentials.

this is fascism.

if you don’t stand up right now and use your voice then you are part of the problem. if you don’t get out and VOTE you are allowing the problem to continue. we have seen these stories play out before… remember tiananmen square? don’t be a silent bystander.

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Administrative Statecraft

Administrative Authority

Possession of the inalienable natural right to pursue the quest of human flourishing according to their own deliberations (i.e. the freedom of rational conscience) inherently entails with it the authorization to put these deliberations into effect, and to protect this right against obstruction, on one’s own behalf and for others. Yet such wide private discretion at the same time also enables irrational obstruction of the pursuits of others for offense to mere personal sensibilities, even if by mere error on the part of self-righteous executors. This contributes to the twin motives of entering into civil society, as protection from self-serving “punishments” on the part of their victim and to lessen the possibility of “righteous” error in execution. Tyranny is the domain not only of those without integrity, but also of the self-righteous.

Hence, in civil society this prerogative is delegated to the administrator(s) which have been empowered to enforce the public will by the mutual reasoning of the people, in order to enable a more perfect protection of their rights and pursuits. For this reason, the duly-delegated administrator(s) of civil law is/are rightfully invested with significant discretion in the fulfillment of their public duties, granted the power to act or not act where no convention has been established by the public nor is ever likely to be by a wise public given the highly specific nature of particular cases. (This discretion extends to the granting of exceptions to these conventions to second parties, as the various exigencies of existence that might press one into violation against one’s choice can hardly be systematically covered by deliberation.) Finally, this administrative prerogative may, in cases of imminent emergency, itself take exception to the established conventions of the public, if doing so becomes incumbent on them in their fundamental duty of preserving the natural rights of the public, as it cannot be presumed that a public intended to thus harm itself.

Natural Right and Administrative Prerogative

Yet administrative action should not be seen as synonymous with civil law, as if the natural rights to “life, liberty, and estate” existed at the discretion of the administrative behemoth, or incorporated within its sovereign will, pace Hobbes. While on its face, such a doctrine may seem to conserve the stability and security of the public insofar as construction of civil convention is subject to the pragmatic understanding of their administration, in the end this simply favors administrative innovation in accordance with the irrational sensibilities of the administrator(s), as under such conditions they will function like anyone else outside of civil society. One cannot expect the public will to be administered with the strict economy of a private interest, for then civil society would need to become the private estate of the administrator(s), and so under an arbitrary absolutism. Hence, administrative prerogative is precisely limited to securing the natural rights on which condition the public is properly constituted, and should not be pursued in violation of this by the wise public officer, as doing so will ultimately be deleterious to the office. While such exercises are not inherently wrongful usurpation, nevertheless such convention-breaking acts must be subject to public deliberation after they occur, lest they extend beyond these limitations through error or wanton desire. In particular, administrators cannot appropriate resources from the public to fulfill their personal sensibilities, but only in accordance with the direction of the public will, or the post hoc indemnification by such. (Without these boundaries, administrative prerogative becomes equivalent to a self-pardon, hopeless mired in self-attachment.) Thus, such exertions are wise only to the degree that they hasten the end of palpable emergency conditions and contribute to the restoration of tempering deliberation. For energetic administration is a friend of liberty, but overly energetic its enemy.

Reserved to the public itself is the higher, revolutionary prerogative to resist the tyrannical exertion of administrative power when it usurps public deliberation, as it is emphatically the right of the people to preserve society from deteriorating back into irrational anomie, and such administrators void their civil authority. However, as a famous declarer of liberty in his more impartial moments once noted: “Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are suffer-able than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.” An overly-paranoid stance towards administrative office on account of this problem, while on its face protective of the public will, in reality has a tendency to foment insurrection on account of offense to atomic interests substituted for the public good, and tends to encourage the very degradation into lawlessness it perceives itself as avoiding. Thus, the assumption of this revolutionary prerogative by the people is a method of last resort for the prudent public officer, and furthermore, is simply incredible without any concrete re-delegation of administrative authority, as this only generates a vacuum of unenforced decisions which inevitably promote reversion to uncivil anomie.

Intrinsically offensive to the natural expectation that civil society will secure ‘life, liberty, and estate,’ though, is any generalized authorization of administrators to search and seize personal estates, without reasonable evidence of commission of a specific violation of public convention sufficient to convince a third party. Doing so places the concrete standing for the operation of the liberty of conscience (i.e. the security of personal estate) at the peril of the atomic sensibilities of the enforcer, the people permitted or denied their quest according to the discretion of any given administrator. (As such liberty is a necessary consequence of general human nature, it applies just as much to peoples foreign to one another as it does to those in civil society; search-and-seizures simply must be warranted by sufficient evidence of a person acting on behalf of a foreign administration rather than violating conventions, if and only if the primary end shifts to foreign scrutiny.) For similar reasons, the detention at the sole discretion of administrators of persons deemed particularly offensive, is an especially egregious violation of the natural rights of the detainee, aimed as such action is at rendering one compliant with the enforcer’s sensibilities by breaking one’s ability to question their reasoning. Hence, continued resistance to subjection to the unreasonable sensibilities of despots requires people be forcibly detained only when evidence exists of violation of public convention reasonably convincing to a third party. While administrators may temporarily detain individuals as an immediate response to general insurrection against public convention or invasion at their discretion, insofar as this may be reasonably reckoned to be necessary to secure the public safety, nevertheless their decisions are subject to public review after the fact, when the public can deliberate over the protracted use of force against the unruly or the foreign invader. Executive suspension of this right against detention by sheer force amounts a contradiction in terms, placing restriction of executive discretion at their discretion rather than public determination of exceptional circumstance, thus making executive decisions on who may resist their sensibilities “inherently” conventional. (Like freedom from search-and-seizures without specific warrant, freedom from discretionary detention by administrators is a necessary consequence of general human nature, and applies as much to peoples hostile to one another as to those in civil society, however difficult fellow-feeling may be towards them.)

Likewise characteristic of despotic administration is the compulsion of its own dictates as necessary conditions of any “permissible” public deliberation (whether direct or that of a select legislature), as doing so erases the delegated nature of all administrative authority and so its prior reliance on the public will. In particular, occupation of personal estates by forces raised for foreign defense during times of peace without individual consent, or without public constraint on its implementation in times of extended conflict, is an implicit declaration of hostility towards civil society originating from a despot’s paranoia of their enmity. Another manner by which this goal might be achieved, is the attempted denial of any reserved capacity to provide for the common defense to the public beyond the limits of their prerogative. By disarming the public of this basic capacity, overly-energetic administrators clear the field for the unrestrained use of force typical of the irrational anomie civil society was formed to escape on behalf of their dictates, and so ultimately undercut the reason for their own rule. Fully consonant with this is the promotion of unrestrained license to use force on the part of some privileged interests, insofar as this nevertheless undermines the public’s right to its own defense in such a way that said interests are likely to combine behind the despot.

The Executive In Chief

While mature deliberation over the project of rational flourishing is aided by participation in a joint process of mutual reasoning with the entire public, good administration of the results of this public process is subject to the opposite demands of vigor in execution (despite non-compliance out of atomic interest) and responsibility to the public (for negligence of office or for violation of their rights). Instrumental towards vigorous execution is the division of labor along clear lines of administrative responsibility, all answerable to a preeminent executive themself responsible only to the public for ensuring that their will is carried out; one person is more able to provide a consistent definition to an administration than a collective. Therefore, it is the prerogative of the chief executive to appoint individuals in subordinate roles and likewise to remove them when they no longer carry the confidence of the supervising chief. Yet these roles and the directness of their relationship to the chief are themselves defined by public convention (including the personal determinations of any select legislature), and so any executive attempt to supplant these definitions by the use of such powers is necessarily an usurpation. The authority to supervise does not inherently grant the right to execute the prerogative directly by the supervisor rather than their appointees, as this may well dissolve the public defined aims of the division of administrative responsibility. Nevertheless, if public officers conspire to undermine the enforcement of public convention out of atomic interest (i.e. commit acts of bribery or extortion), a single chief supervisor is more answerable for the mislabors of subordinates and more capable of vigorously removing them from their roles. Further, one chief is more clearly responsible to the public for any abuse of the authority of their public office for the sake of their atomic interests, compared to members of a premier group. Likewise, if a chief executive is innocently but permanently incapable of fulfilling the functions of their office, the necessity of their removal and replacement will be much more clearly perceived than if they were merely members of an executive group.

In addition to these concerns, a singular executive is even more crucial in foreign affairs, as those who never participated in the process of joint reasoning remain in a state of natural liberty unbound by the conventions of that public. For this reason, the delegated chief administrator stand in as free a relation to the chiefs of other publics as did their various people in the formation of civil society, and therefore must be just as capable of self-responsibility as a single individual. Hence, the initiation of new civil conventions with foreign people or enforcement of the status quo towards them, and the maintenance of a consistent standard of officer communication needed to do so, are the prerogative of the chief, as is the vigorous defense of the public from infringement by other peoples, except as this discretion is specifically limited by convention. Even public convention may be taken exception to in the case of immediate responses to sudden attack or insurrection, as by forcing administration to abdicate its duties such deliberative overreach would oblige the public to give up their liberty. Nevertheless, such actions are subject to public deliberation concerning their necessity after they occur, and for this reason revenue for extended wars cannot be compelled from the public or its select legislators, lest war be irresponsibly pursued. Likewise, no extended commitments initiated or voided between administrations may be compelled from the public or select legislators, lest public flourishing be unreasonably entangled in foreign events or civil relations with foreign peoples unreasonably revert to anomie.

Violence directed against the functioning of delegated authority, above all in the person of the chief, by members of the public that delegated said authority and so to whom they owe allegiance, is an attack on the integrity of open deliberation and the public will, as is any concrete aid to foreign people who seek to do likewise. (The same is true of an attack on the authority of subordinate personnel, but to a lesser degree, as only the chief supervises administration of the whole public will.) Anyone who enters under the scope of regulation by the conventions of the public, even those who are so situated only temporarily may be guilty of the same offense, for they are still under the protection of the chief’s administration. A violent breach of public faith in the most fundamental pro-social commitment, such treachery nevertheless occurs within a single civil society rather than between peoples, and should be dealt with as such if responsible self-government is to be truly restored. Conversely, those who oppose delegated authority to protect a people, without ever coming under its protection are simply foreign enemies; even if they do so covertly, they are not guilty of a basic breach of faith, but merely act from a state of nature. But it is the height of irresponsible warfare for one administration to incite treachery against the delegated authority of another, for when their people have not yet resolved to avail themselves of their revolutionary prerogative against executive usurpation, this only serves as an abortive usurpation of domestic deliberation. For unless the chief usurped their position of authority in toto (as in the case of a violent coup), it is a matter of serious deliberation whether the authorized person has exceeded their delegated office and robbed civil society of the ability to govern itself. lest by imprudence one treacherously attack the prerogative of a civil servant.

#natural rights and executive prerogative#administrative government#administrative government and civil society#the administrative branch#separation of the deliberative branch from the administrative#hobbesian philosophy#authoritarianism#authoritarian absolutism#anti-authoritarianism#lockean philosophy#whig politics#classical republicanism#the revolutionary prerogative of the public#authoritarianism and general warrants to search and seize#the right against search and seizure without specific warrant#the reserved right of the public to provide for the common defense#the right against stationing of public defense forces in private estates#executive prerogative and foreign affairs#responsible administration and the singular chief executive#the chief executive's prerogative of appointment and dismissal of subordinates#subordinate administrative roles as defined by the public will not the chief executive#subversion of public definition of subordinate roles as executive usurpation#the single executive as capable of more vigorously removing corrupt subordinates#the single executive as more clearly answerable to the public for personal corruption#the single executive as more clearly physically or mentally incapable to the public#the definition of treason

0 notes

Text

The Liberty of Conscientious Association

The Right of Personal Estate

The inalienable right of every person to the freedom of rational conscience necessarily entails the corollary right to use any resource acquired by their own labors for whatever pursuit they see fit, except insofar as the acquisition of such is predicated upon obstructing the natural right of another person to do likewise. Without this subordinate right, the right to freedom of conscience lacks concrete standing for its operation but remains an abstraction; no species of resource can be affixed concrete value for human flourishing independent of such pursuits, without subordinating the natural right of free evaluation to some arbitrary sensibility.

Precisely due to the fact that resources cannot be affixed value apart from use, the spoilage of resources for one’s purposes due to accumulation beyond personal utility represents an obstruction of the right of others to affix value, offering a natural limit on the extension of concrete standing for one’s personal view of flourishing. Conversely, no one can lay claim by natural right to the seizure of resources in which the labor of another was independently invested, as doing so amounts to materially obstructing another in their use of their liberty of rational conscience. Parental dominion extends only as far as is necessary to guard the maturation of the immature, aiming at promoting their eventual flourishing on their own terms according to natural right, earned solely by fellow-feeling for their humanity, not by the usefulness of their labors to the one who claims dominion, contra Calhoun. (If parents are incapable of providing such guardianship, provision by others in civil society is therefore earned by fellow-feeling for their humanity, lest a category error be committed by not preserving their independent flourishing until maturity.)

Civic Duty And Atomic Preference

Through voluntary participation in a joint process of mutual reasoning with the rest of the public, each person thereby consents to the direction of the public will of their own decision-making as pertains to the protection of their natural rights to ‘life, liberty, and [personal] estate’ (to paraphrase Locke), and only on the understanding that every other person who so participates is similarly subject to its direction. Such is the liberty of conscientious association, the concrete social operation of the freedom of rational conscience that is the inalienable right of every person; compelling participation in the process of reasoning on any further stipulations is to commit a category error, denying the actual character of one’s fellow persons. On this basis, civil society obtains the power to develop legislative conventions to preserve the lives of those participating in it, and to minimally secure for its members a reasonable opportunity to acquire property for their personal pursuits. This remains true even against what the preferences of some participants might be as atomic individuals; in this capacity, their associates simply serve as an aid to their own project of rational flourishing against their irrational sensibilities, and if they do not desire such controls, then they must also abandon the aid of such. Attempting to retain these benefits of association while imposing individual preference on them against the direction of the public will by force, represents the disintegration of civil society into anomie and not liberty (in any responsible sense).

As such, the opportunity to employ one’s labor in good conscience cannot become merely a matter of another’s discretion within society. For a civil society is already a voluntary conscientious association, and the discretion of individuals or voluntary associations within it cannot be privileged over civic fellow-feeling, as if their atomic sensibilities were absolute. Thus, civil society may generate legislation regulating the discretionary use of property by its members to insure the natural rights of other members against the adverse impacts of such, as long as the members regulated thereby are permitted to join in the process. Likewise, if by such public convention a select body of the public is dedicated to legislation, then this body has every right to raise the revenue necessary to fulfill these functions from the property of the entire public (regardless of the personal preferences of participants as atomic individuals), as long as the constitution of select body is subject to the joint deliberation of the taxed public. Further, as a derivative of the aforementioned liberty of association, such a select body and their deliberations must be free from prior executive stipulation, or else their legislation can’t be given substance by a free conscience.

The Liberty of Association and Unqualified Incorporation Within A Collective

Yet this directing power cannot rightfully consist of an unqualified dominion over human beings, but rather must be tailored towards securing these natural rights to the greatest degree actually possible. Because these rights are possessed by virtue of our questioning nature and not mere social construction, they are neither incorporated in the public’s legislative will nor at its own sovereign discretion, pace Rousseau. While on its face, that doctrine may seem radically republican because it renders all things subject to the construction of the will of the people, in the end it becomes criminal, because it wrongly assumes that our fellow human being does not and cannot meaningfully exist for us prior to public determination, denying them any true liberty of conscientious association. In doing so, Rousseau’s doctrine undercuts the very sympathy necessary for civil society, while substituting in its name the passing sensibilities of mere combinations, foolishly ‘constructing’ new humanities out of whole cloth while denying the bivalent nature of what really exists. The ability of individual human beings to responsibly define their own existence is only undercut by the idea that they are defined without qualification by a collective that cannot exist apart from them, whatever Rosseau thought to the contrary.

Hence, while civil society may as an end-result of public deliberation choose to assert the eminent dominion of the public over the personal estate of any one of its members and seize it for public use, such legislative action cannot rightfully be performed without fully compensating the private owner or owners for its use. Failing to do so renders the concrete base for the operation of the inalienable liberty of conscience in peril of the passing whims of combinations of actors. Civil society may not, any more than a private person, rightfully claim parental dominion over its members’ labors and reduce the measure of the value of their labors to their social utility, and a fortiori may not allow the seizure of their estate by another private person whose labor is attributed greater social utility, as this denies their prior humanity. While parental dominion over private labor will rarely be claimed as long as the deliberative body is coterminous with the entire public (as it nearly lacks any meaning), when by convention a select body of the public is dedicated to explicit legislation, then the claim of that select body to such dominion over the society they represent appears more feasible, if still lacking any basis on natural right. More generally, a civil society will not compel its members to directly act or not act in that which does not deny to others their natural rights or leave them a matter of private discretion; the power to raise revenue for fulfillment of the public will regardless of atomic sensibilities does not extend to making people labor against conscience.

Likewise, it offends natural right for any revolutionary society to retroactively change the civil status of a person’s behavior in the aftermath of its commission, or to define a person or association as guilty of violation of the public will by mere convention. For in neither circumstance had the person concerned at the time of the action actually removed themselves from subjection to the direction of the public will, though they may perhaps be hoodwinked into believing they had done so during the process of deliberation or after by a deft enough hand. Rather than the individual being guilty of breaking the implicit, inviolable compact under-girding all civil deliberation, in such a case the legislators are guilty of denying to the individual the liberty of not violating their own conscience as a precondition of association. Furthermore, even when such uncivil means seem to accomplish civic ends by bringing those suspected of finessing away defiance of the public will under its power, they in fact only reinforce the conspiratorial intransigence of such by rendering taking civic responsibility for one’s actions impossible by definition.

A particular creed about human flourishing can therefore only be maintained in the last instance by persuasion and not by compulsion; it violates natural right for any particular creed to be proscribed by convention, or for revenue from the property of the public to be prescribed for the promotion of a particular creed. Any duties entailed by a specific creed may be promoted only by means which avoid doing violence to the conscience, but rely on prior voluntary acceptance. Sincere civic motives concerning joint subordination to the direction of the public may indeed lead societies naive to power to the mistake of expecting exclusive patronage by public officials of specific ends of rational flourishing over others, because on its face this seems conducive to enforcing the results of discussion. However, official prescription of any particular creed by its very nature places it above the social context where it was shown to merit special consideration, consequently isolating itself from ongoing public discussions and inadvertently ensures that it fade from future public interest. As a result, continued devotion to the one-time civic creed seems to demand that heedlessness of the creed be understood as intransigence of public convention, mercilessly laying added conditions for civil society on the rational conscience. Such imprudence only becomes destructive of the very roots it seeks to protect, innovating trivialities it imagines as important memories, catching itself up in a vicious cyclone from which it can’t escape intact; the creed may be exposed to renewed interest and reborn in a new context, but only in spite of such activity. Regardless of how illuminating it is, no creed can deny conscientious objection without harming itself, and so the public officer must prescribe the creed of natural right to be free from such compulsion as necessary (if not sufficient) for wisdom, and proscribe any creed acting to usurp coercive office as if its own estate. (Naturally, nothing prohibits a wise public officer from promoting a particular creed with their own personal estate, or personally arguing for the merits of that creed or against others, provided that this creed of natural right restrains their public office.)

Common Education

Thorough instruction in the civic conventions governing one’s society and their anthropological context, is necessary to participation in public deliberation, lest substantive preceding deliberation be nullified by ignorance or misinformation. Hence, a minimal common standard of education, developed by prior public deliberation on the relevant facts, is essential to the common good, and so must be raised in accordance with increasing participation in the process of public deliberation, if needless destruction of opportunity and life are to be avoided. While such instruction can never extract human sympathy from its admixture with self-serving motives brought to education, it can ameliorate their corrosive effects by tempering individual judgement against tyranny via investigation of past personal and collective heedlessness, and thus informing social construction piecemeal.

#natural rights#property rights#property rights and universal human solidarity#public deliberation#the participatory public#the deliberative branch#the legislative branch#the liberty of conscientious association#separation of the deliberative branch from the administrative#Lockean Philosophy#Whig Politics#Rousseauian Philosophy#Collectivism#Classical Republicanism#Eminent Domain and Just Compensation#ex postfacto law#bills of attainder#prohibition of compulsory support of a particular creed by proscription or prescription#Whig Politics and A Common Standard of Civic Education As A Positive Right

0 notes

Text

On The Nature of Federation

The Differences Between Confederation and Federation

A confederation forms when the conventional representatives of different publics seek to leave behind the state of natural right and enter into civil society with one another, by participating in a joint process of mutual reasoning and consenting to submit any further executive discretion to the common direction of the alliance. The conventions of such a system are loosely maintained by continued support of representatives who support such participation by their discrete publics, for self-preservation and the desirability of civil relations between representatives. Such an alliance lacks the strength to enforce its conclusions on any recalcitrant publics, as distinguished from particular representatives; any people party to a confederacy may unilaterally dissolve their ties by replacing its representatives the moment it is in their interest to do so, without internal reversion to anomie. Likewise, they may unilaterally nullify individual decisions by a similar method, without other peoples in the alliance having any civic reason for using force. Conversely, a federation forms when the common direction of the alliance is in turn itself directly supported by public convention within each discrete public. Hence, a federal union of pre-existing peoples must in fact constitute a new federal public will, which lays the same claim upon its constituent peoples on the condition of their voluntary entry, as they lay upon their constituent individuals.

Mutual subordination to the direction of the will of the federal public is incumbent on all constituents; unilateral nullification of federal convention or secession from the federal public is manifestly insubordinate to the rule of (current, positive) law, as much as it would be for their constituents to similarly pursue atomic interest. To suggest either as a conventional remedy is, in reality, to covertly suggest the extra-conventional remedy of revolution under a disguise; the very opaqueness of its use to civil society suggests an attempt to finesse the risk of reversion to uncivil anomie such that the dangers involved largely accrue to other peoples. (Both in the eyes of federal civil society but also in the minds of its purveyors.) Furthermore, the implementation of either serve as an attempt to wield such dangers against these peoples in order to coerce their passivity before added terms for “pure” civil society at the federal level, betraying fool-hardy designs to suppress the interests of other peoples as if they had no natural right to them. A wiser people would first seek recourse to more temperate nullification by mutual agreement, or that failing, the dissolution of their ties to the will of the federal public and so secession by mutual convention among all constituent parties. If such civil dissolution of ties is sought after yet denied, then the natural right of each people to defend their public interest may no longer be protected from inimical combinations by conventional means, revolution transparently justified. Pretense towards unilateral nullification or unilateral, “conventional” secession in their place manifests proud unruliness, innovation uprooted from human nature.

The Differences Between Federation and Unitary Government

In a unitary state, its constituent peoples are made as one by force and finesse; their combination is treated as an involuntary, passive product of the stately, and the reality of their discrete interests as ultimately dependent upon the prior authorization of an always already existing Union, subject to its final abrogation. The federation of pre-existing peoples is not synonymous with such a One, as federal civil society is produced by voluntary convention within and between them, and continued administration is conditioned on acknowledgement of this. Yet conspirators tend to encourage confusion and slow erasure of federal civil society in favor of such a One out of illusionary sympathy and against incivility exaggerated, as well as the more jarring over-transformation of confederacies after the endangerment of the self-interest of its strongest member peoples. Such an attitude may appear (usually in its early stages) in the form of populist demagoguery and mystification of the liberty of rational conscience at the federal level, or at the behest of an insubordinate faction claiming synonymy of its best interests with the federal public’s (usually, the former in a later stage). In either case, it betrays the corrosion of societal wisdom concerning the inalienable liberties human beings possess by nature from too long giving general license to their violation, out of public self-satisfaction with its current range of flourishing. The natural, unfortunate, inevitable consequence of this is the development of a habitual, vicious intemperance which successfully masks its authoritarian nature towards other members of the federal society by affecting an entire people, and by deflection via castigation of the differing license of other people.

In the particular case of American history, the Decline of Whiggery in federal politics was therefore a significant prelude to the War Between The States. Having too long given license to estate in other human beings and associated denial of the freedom of association in favor of resisting only the exceptionally authoritarian individual, they were unable to deal the conspiratorial unitary-statism within Jacksonian populism a blow at its roots. Due to this un-owlish lack of subtlety, the Era of Federal Whiggery was inevitably replaced by hypocritical populism and unitary-statist mystification from “National Unionist” Yankees, and covert aristocratic insubordination to federal civil society from Dixie “Rebels”. The pervasive lack of the necessary sincere, deep appreciation for the liberty of rational conscience itself among National Unionists is evident from the “War Jacksonian” license to the actual insubordinate estates, and from “Radical” extraction of solemn affirmation of retro-activating convention for civil re-entry. The play of these dual influences against each other only encouraged further intransigence on the part of those they had once jointly defeated, allowing mystification of the Great Slaver Insurrection as a “Lost Cause” of noble liberty to take root instead of the federal public going beyond this unfortunate heritage.

#Systems of Government#Confederacy#Federation#The Unitary State#The Constitution of A Federal Public#Unilateral Nullification as Insurrection#Unilateral Secession as Insurrection#The Legitimacy of Mutual Nullification#The Legitimacy of Dissolution of Federal Unification By Mutual Convention#Unitarism#Conspiratorial Unitarism#Unitarism and Populist Mystification#Unitarism and Aristocratic Insubordination#The War Between The States#The Decline of Whiggery and the War Between The States#The Populist Unitarist Mystification of the National Unionist Yankees#The Covert Aristocratic Insubordination of Dixie Rebels#The Great Slave Insurrection#War Jacksonian License Towards Unruly Estates#Radical Coercion of Solemn Affirmation of Ex Postfacto Law Before Civil Reentry#Lockean Philosophy#Whig Politics#Anti-Authoritarianism#Classical Republicanism

0 notes

Text

The Freedom of Honest Discussion

Seditious Speech and Prior Administrative Clearance

The administrator of the public will would be wise to avoid suppressing public discussion, unless there is a palpable risk that it will incite imminent action in violation of specific contemporary public convention. Going beyond this is to exceed the proper office of the administrator, by attempting to subject the social employment and development of rational conscience to the prior condition that it may not exhibit any general tendency to seriously discredit any contemporary convention — morally presumptuous to the point of incredulity upon analysis. The former is (openly or covertly) seditious, encouraging atomic individuals to consider themselves above the public will; the latter risks indirectly encouraging such action, yet is necessary for the public will to be constituted in a manner that enables pursuit of rational flourishing, as humans have a natural right to expect.

The requirement of prior administrative clearance before a certain matter or specific information pertaining to it may be publicly discussed, is particularly inimical to this natural end of civil society, more so than subsequent punishment. The task of censorship of public discussion is both thankless in its unalloyed contradiction to (and constant innovation over) the most basic liberty of rational conscience, as well as utterly debilitating in its infantilization of the discussion still authorized. Likewise, any attempt to covertly administer such censorship through enjoinment by third-party adjudicators esteemed impartial by the public, fails to avoid these dual consequences; irreparable damage may be done to this esteem if such preening be conventionally permitted, the public good trivialized, the damage done being all the more insidious for all its systematic narrowing. Doing so risks contributing to later public licensure of anomie antithetical to all creeds in the lightest of disguises for its obscenity, despite the opposite intent; the effects may be less immediately obvious than for direct intimidation, but degeneration of civility cannot be finessed away.

Only if there is a palpable risk of imminent endangerment of the public interest by the very exposure of administrative procedural secrets to forces inimical to their liberties (e.g. syndicated crime or warring peoples), can this ever be truly justified. The mere embarrassment of administrative sensibilities, concerning the public interest or otherwise, in the public eye via such exposure can never justify its censorship, however it may demoralize them in their fight against such forces; this is needful so any tendency towards innovation remains in reasonable limits. Only the restriction of the activities of the characteristically unreasonable officer, and the chastening of the characteristically reasonable one gone astray, is likely to ever come from this liberty, and so it is essential to a well-constituted society.

Identitarian Speech, Sedition, And Good Faith Discussion

Identitarian speech is particularly perverse, tending to undercut reasonable and fair discussion by attempting to rhetorically rig the free play of civil discussion in favor of certain participants, on account of something about themselves they did not choose. This has the effect of reducing everyone to solely a victim and/or a beneficiary of inadvertent circumstance, slowly eroding any social possibility for employing the liberty of rational conscience and glossing over the complex inter-relationship between choice and circumstance. Yet despite its demonstrable and perverse tendency to undermine discussion of any truly public or common good, it is still most wise for the public officer to tolerate (if not encourage) all identitarian speech. For such speech is the irrepressible natural response to embrace of the beguiling idea that the liberty of rational conscience is employed in a social vacuum, and a final refuge from the rhetorical smothering of their specific interests by combinations claiming to embody the whole public de facto. Conversely, deliberate encouragement of identitarian speech betrays a certain authoritarian grandiosity on the part of the public officer and/or their cohorts, a willful heedlessness of any conscientious use of liberty that lies outside of their personal sensibilities. (Intemperate license/permissiveness tends to exist on the underside of intemperate idealism, needing only the right conditions to surface.) The starkest example of this is the toleration of identitarian speech which enters into incitement of imminent violation of the public will (typically, of aggression); this conveys demonstrable disrespect for the rule of law, and is incredibly foolish in its undermining the very authority by which their office is made most secure.

Rather than identitarian speech, premised solely or primarily on conditions that people cannot choose, the wise public officer would encourage good faith discussion, the discovery of deeper meaning in standards of value personally and actively chosen between as the fruit of the sacred liberty of conscience. Furthermore, they would disown all bad faith, and every combination beguiling the public with the notion that their standards and interests command universal assent by every conscientious person, while suppressing real dissent by force. Only if the public remains on guard against such presumptuous “politicking”, and their officers do not abuse their delegated authority by the willful confusion of the terms of discussion, is identitarian behavior ultimately avoidable for civil society. Otherwise, the discovery of social meaning through standards of value actively chosen will be discouraged among those smothered through such connivance, convincing them that only that in themselves that is non-compliant to such abuse has public value, while in reality rendering them fools of the rank authoritarian (appeals to a phantasmagorical “pure atomic individualism” non-withstanding).

Defamation of Public Officers And Energetic Administration of the Public Will

A well-constituted society will establish conventions to hold accountable those defamers who disregard truth out of malice towards due authority, for the exposure of the reputation of public officers to public infamy erodes their delegated authority and so paralyzes the very energies by which the public will is properly administered. However, the liberty of all honest discussion is necessary for the employment of the sacred liberty of rational conscience, and thus is fundamental to civil society; swift exposure of unfortunate truths about the maladministration of public officers paralyzes precisely that over-stepping energy of their administration, and thus prevents the incidental violation of rights from becoming habitual intemperance. Owing to the finite capacity of human beings to ascertain the truth of any matter, a certain level of reasonable misunderstanding is an inevitable corollary of this, and would not be liable to administrative retaliation in a well-constituted society; allowing public officers to dictate what misunderstandings are reasonable, is to permit them to covertly rationalize the public will as synonymous with their private sensibilities.

The Unexceptional Nature of The Obscene

Obscenely sexual or violent expression (i.e. ”fighting words”), because of how either provokes the implosion of joint deliberation into uncivil anomie by direct appeal against reasonability to the non-reasonable sensibilities of humankind, may seem on its face to self-justify suppression in a way other forms do not. Yet the category cannot be censured from mature discussion beforehand, because such sensibilities tend to be unconventional by nature, such that which once shocked the public unreasonable may later seem rather domestic, and that which once seemed unworthy of notice may later cause tensions to boil over. As a result, any such censorship attempts must necessarily be left to administrative discretion, and so exhibit the related tendency to innovate irrational commands with no ground in human nature on the basis of atomic sensibility (or interest). This only serves to expose the public office involved to embarrassment, and to the unnecessary wasting of precious energies on trivial matters rather on than on the pursuit of submitting all genuine violators to the interests of civil society. Furthermore, it tends to fool the public into a false sense of security over rising injustices or those deemed vanquished, allowing the belief to develop that those in the know have already taken of such things and so stranding them without the crucial calibration mechanism of a fundamentally informed and analytical public. For this reason, the only form of obscenely sexual or violent expression that temperance ever censures is that which already involves violation of human nature in other ways (e.g. media sexually or violently exploiting the immature). Other than this, no sexual or violent expression of any kind should be placed beyond the bounds of mature discussion; if specific cases of expression can be shown to be proximate causes of violation of civic relations, then they may still be punishable after expression, but only by posterior agreement of the public. The persistence of ideological flagellation for the general public on definitions mistakes the basic issue, and distracts from tackling more covert exchanges.

#The Freedom of Honest Speech#Freedom to Question Contemporary Custom#Prohibition of Inciting Imminent Lawless Action#Sedition As Imminent Lawless Action#Freedom From Administrative Preclearance#Freedom From Censorship By Judicial Injuction#The National Security Exception#Prohibition of Exposing The Public Interest To Imminent Danger#Identitarian Speech#The Perverse Tendencies of Identitarianism#The Necessary Public Toleration of Identitarian Speech#Identitarianism As The Natural Response to Neoliberal/Neoconservative Vacuity#Official Encouragement of Identitarian Speech as Betraying Authoritarian Grandiosity#Wise Statesmanship and The Encouragement of Good Faith Discussion#Identitarianism and Discussion in Bad Faith#Defamation of Delegated Authority#Defamation as Paralyzing The Energetic Administration of the Public Will#Defamation as Malicious Disregard For The Truth#Defamation Versus Infamy by Honest Misunderstanding#Defamation Versus Infamy by Exposure of Unfortunate Truths#Lockean Philosophy#Whig Politics#Anti-Authoritarianism#Obscenity#Fighting Words#The Unexceptional Nature of The Obscene In Itself

0 notes

Link

Following Doug Jones’s victory over Roy Moore in Tuesday’s special election, black women’s celebrated status as the Democratic party’s most reliable voting bloc reached its zenith. Jones’s win is widely attributed to overwhelming black voter support and higher-than-average black turnout. Thus, for some, the takeaway from Jones’s victory was obvious: trust black women.

Hillary Clinton memorably referred to minority voters as her “firewall”, but it seems black women have become more than simply a political bulwark: we’ve evolved into a symbol of ideological righteousness – America’s moral compass.

That sentiment reached a fever pitch on Tuesday, when the hashtag #blackwomen trended along with gushing praise for black female voters, peaking perhaps with the author Molly Knight’s tweet arguing that “black women [should] run everything”, followed by the actor Mark Ruffalo’s cosign: “I’m definitely ready for that. I said a prayer the other day and when God answered me back she was a Black Woman.”

However flattering it may be to feel integral to the party’s success (and Mark Ruffalo’s prayers), this characterization presents a problem. Black women don’t need a hagiography: we need a voice.

The reality is that the political determinism emblemized by the #trustblackwomen hashtag isn’t so much a compliment as much as it is a gilded cage. Black women aren’t electoral talismans. We don’t have intrinsic moral authority, nor should our votes be taken as an imprimatur of virtue for the Democratic party – a party which fails us more often than not. What the homogenous nature of the black voting bloc does represent, however, is a deficit of options.

In politics, black women, heralded for our diversity, aren’t allowed any diversity of self

Unlike white voters, who have the luxury of weighing a range of individual political concerns, personal beliefs, and material needs at the ballot box, black voters are united by the constant threat of political disenfranchisement, state violence, and economic exploitation.

Thus constrained by existential vulnerability, black women have become masters at assessing the lesser of the evils presented. We aren’t messiahs, we’re merely experts in risk mitigation. Case in point: the reality TV villain and Trump adviser #Omarosa was trending at the same time as #blackwomen. And it wasn’t because she saved the Democratic party.

By treating black women as political bellwethers, Democrats transform a choice made under duress into a ringing endorsement, and even worse, by idolizing our party commitment, they flatter us into forgetting we’re in a cage without bars.

As one savvy tweeter noted: “If we make black women into gods, we can continue to ignore polices that benefit their material needs since only mere mortals worry about those things.” Put another way: there’s is no pride in being a firewall. Perhaps it’s time for black women to withhold fealty to a party that would treat it as a shield rather than something worth fighting to protect.

(Continue Reading)

#Partisanship#Partisanship and Moral Corrosion#The Alabama Senate Election#The False Dualism of Partisanship#Fealty to Party for Party's Sake#The Speciousness of Treating Any Group as Possessing Intrinsic Moral Authority

140 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

22 Minute Documentary on Charlottesville

Watch this video.

#white supremacism#The Klu Klux Klan#Neo-Nazism#racist terrorism#domestic terror#recent events#Charlottesville#The Charlottesville Attack#Non-Political Philosophy Post

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

On Adjudication

Human Capacity for Rational Judgement and Impartial Third-Party Adjudication

Possession of the right to freedom of rational conscience entails with it the capacity to judge for oneself what the natural law requires in matters of dispute between oneself and others; while one might voluntarily defer to individuals who in one's estimation possess a more mature understanding, none possess the capacity to judge for others by natural right. Yet, much like in the case of the enforcement power, such wide private discretion tends to serve as license for judgments biased in favor of the interest of the adjudicator in question to the exclusion of that of the other party. Hence, in civil society such discretion is transferred to publicly-designated adjudicators to act as an indifferent third-party without atomic interest involved in the conflicts reviewed, to settle their claims according to established convention. As a legal method of reducing the necessity of recourse by the public to their revolutionary prerogative to avoid the manifold dangers of uncivil anomie, an independent system for the adjudication of wrongs not only by private persons but also by public officials is the wisest of measures; if the adjudicators are not esteemed independent of the administrative and the deliberative power, they will not be able to impartially judge public officers, as they will have to curry their favor.

Implicit in submission to the public will and the third-party adjudicators it designates, is the civil expectation that 'life, liberty, and [personal] estate' will not be deprived arbitrarily on the irrational whims of others (of whatever position) but only according to fair procedures due to every member of society. The intrinsic nature of fair dispute requires the person to be afforded timely notice of the legal offense under prosecution and allowing them the chance to have their own viewpoint heard (or it is no dialogue at all), before a final decision can be adjudicated to form a solemn compact between the disputants without bias towards either, and an explicit communication of the reasoning and facts grounding the verdict is necessary. (In addition, if the convention the person is accused of violating is not explicit in its mandate or includes un-clarified terms publicly agreed to be otherwise ambiguous, the person can hardly be considered to have received truly fair warning that they would possibly offend other parties.)

For this reason, the detention of persons deemed particularly offensive at the sole discretion of administrators, is an especially egregious violation of the natural rights of the detainee, aimed as it is at rendering one compliant with their personal sensibilities by breaking down the ability to question their reasoning. Hence, continued civil resistance to subjection to the unreasonable sensibilities of despots requires an independent adjudicative system capable of commanding any and all administrators to produce the detained for a fair trial. That being said, temperate judgement demands a policy of deference to assertion of administrative prerogative to temporarily detain individuals as an immediate response to insurrection or invasion, insofar as this may be reasonably reckoned to be necessary to secure the public safety. As refusal by the chief administrator of the adjudicative command to produce the detained in such cases is within the bounds of their prerogative, over-eager defense of such only diminishes their prestige and encourages future despotism. Yet adjudication still has the right of review, its use being suspended only by the circumstances and not by administrative determination; in times of protracted rebellion or war, administrative prerogative is therefore no longer owed such deference, insofar as mature judgement may determine detention to no longer have a reasonable basis on appeals for inspection after the immediate crisis. Executive suspension of this right amounts a contradiction in terms, placing the restriction of executive discretion at executive discretion, thus making executive decisions on who may resist their sensibilities “inherently” conventional. (Like freedom from search-and-seizures without specific warrant, freedom from solely discretionary detention by administrators is a necessary consequence of general human nature, and so applies as much to peoples foreign and hostile to one another as to those in civil society, however difficult fellow-feeling is toward them.)

Natural Right and The Infamy of Immature Judgement

However, when adjudicators assume the power to overrule convention solely on the grounds of substance, civil society is subverted and justice undercut in the long term. In the short term, such assumption may seem necessary for those at risk and for sympathetic judges to fulfill the important end of protecting the inalienable rights of individuals from the attacks of irrational faction, on the grounds that the public could not have convened together in a fair manner if such policies resulted. Yet such a move inherently grants that public office plenary power to define which rights are "fundamental to civilized liberty" and (more importantly) which are instead disorderly license, according (to what ultimately amounts) to their own personal sensibilities on the morals the people ought to have regulated, thereby contributing to civil society's factionalization. This is hardly to argue that the publicly-designated adjudicators have no capacity to review the conventions that have been established, that they are constrained to follow positive law regardless of appeals concerning their injustice; rather, it is to say that the adjudicator may only override established convention on the basis of inequity, insofar as they judge equality before the law to outweigh established legal precedent in that specific case. More specifically, the wisest course of action is to strictly scrutinize any legislation accused of bias towards a specific class, inquiring whether there is any public interest which compels an override of the general presumption of their equality before the law. As for any other accused violation of right, the law in question is properly judged an illegitimate product of a mere faction only if it cannot reasonably have been reckoned as truly tailored toward the conventional ends of the government when formulated; denial of law for any reason short of this will result in faction, and so tends to reduce the very esteem of the public on which adjudicative power must rely (as the long history of counter-conventional judgments attests).

Precisely because the power of an independent judiciary is solely that of the prestige which is voluntarily attached to mature judgement, rather than the coercive power delegated to administrative officials or the control of resources which may attach to select legislatures, it is entirely dependent on public esteem for the adjudicators and for the quality generally. Despite the (self-interested) paranoia of administrators and select legislators to the contrary, out of the three powers transferred over by the individual to civil society and (indirectly) the public officer the adjudicative is the least dangerous to the rights of the public, and is more likely to be too impotent to resist the pressuring of factions or of despots than to be too powerful for their liberty. On account of natural impotence of mature judgement in the face of irrational faction, the wisest policy is to render the office of the adjudicator unassailable except on account of misbehavior, as conventionally defined; as a practical matter, any judge of law will necessarily be guided to some degree by their personal sensibilities, without such a bias amounting to a corrupting atomic interest. By the same token, it is unwise to focus much to the personal sensibilities of potential candidates rather than on their behavioral record as a determinant of immoderate judgement; doing so will only stoke the factionalization of civil society, until it finally become subject to despotism. The independence of the adjudicative office necessitates a grant of power to interpret the public will coordinate with that of administrative officialdom and select legislatures, which to the dismay of the sword and the purse will often afford them practical supremacy among any people esteeming the rule of law; however, it is foolish to formalize this esteem as settled law, lest such offices then become a caste rationalizing conspiracy against the common good. (As the judicial officers would in practice have to be granted some direct power over “the sword” or “the purse” in order for such formal supremacy to have any effect, this covertly violates the separation of mature judgement from the deliberative and administrative powers, and only by that method affords license for conspiracy.)

Dispensing with the fair procedures inherent to free disputation is a violation of natural right, as is the appeal of either party to the atomic interest of the adjudicator (i.e. through bribery or blackmail); a society which fails to conventionally identify either as misuse of adjudicative office will in due time corrode the liberties of its members, whatever other protections it may otherwise devise. Likewise, the compulsory communication of evidence of a crime is inherently a violation of the so-coerced subject's inalienable freedom of rational conscience: such an imposition tortures the human conscience, by pitting their personal self-interest in not being convicted of crime against the broader motives of fellow-feeling involved in solemn affirmations as compacts, an internal contradiction from which they cannot escape without facing the contempt of the adjudicator. However impartial an adjudicator may perceive themselves to be and may be perceived by others in relation to atomic interest, such an imposition nevertheless represents a radicali subversion of the conditions prerequisite for a properly constituted public will, based as it is on a denial of the dual motives grounding all civil discourse and thus also criminal disputation. (Yet this does not inherently extend to the compulsory provision of incriminating communications voluntarily made, as no subversion of the grounds of discourse has occured.) Furthermore, subsequent prosecution of someone after a final verdict has been reached for violation of the same convention is inherently and always a clear violation of the so-prosecuted subject's rational and civil expectation that the solemn compact of a final verdict direct the prosecuting parties as much as the prosecuted. The violation of this expectation is a violation of basic human sympathy, which forces dehumanizing supplication of their person before irrational prosecutors which adamantly refuse to heed the inviolability of such compacts unless they happen to serve their atomic interest – flagrantly unjust.

There is a certain civil right of appeal consequent upon this rightful expectation of due process, as this is essential to attend to violations of proper legal procedure. An independent system for adjudication of appeals is therefore necessary to complement the ordinary judicature, as a bulwark preserving rational adjudication on the whole from becoming a pliant tool of despotic sensibilities and user of the above despotic means, as well as from corruption. (Needless to say, reversal of decisions made on this basis do not inherently violate the prohibition on prosecution after a final verdict, regardless of any party’s atomic interest to the contrary, because a verdict made in violation of proper legal procedure is hardly a binding compact on either, and because both have a public interest in its proper disputation.) However, in the end the final court of appeals is public opinion, or in other words, the constitutional will of the public; for this reason, wise public officers would render the public conventions regarded as most fundamental explicit (i.e. generating an explicit constitution to serve as the supreme law of the people), while simultaneously providing an equally conventional method for its later amendment by the public. If public officers are too immoderate to provide both, the result is inevitably either an adjudicative system too confused by the transitory whims of faction to settle legal disputes consistently, or else preservation of policies in oligarchical resistance to the direction of the public will, generating common unruliness; in either case, such rash new ventures inevitably collapse from their internal vices.

The same principle applies to the adjudication of information relevant to conviction for offenses against the public; while especially wise judgement is necessary and helpful in properly adjudicating the relative weight of different conventions and the delicate matter of balancing equality before the law against the stability of precedent, such exceptional powers are unnecessary in the simple matter of fact. What is more, such powers even become a liability when adjudicating empirical information, as they easily lend themselves to the rationalization of predetermined conclusions, commonly in deference to administrative interests but also in service to atomic corruption. The social compact therefore demands that the public will of the community in which the apparent offense occurred be properly represented (the manner defined by convention) in the adjudication of information relevant to the perceived offense, so that the administration of law in specific cases is subject to public examination of the facts. For this reason, the publicly-designated adjudicators cannot rightfully assume a grant of power to coerce the representatives of the public will into agreeing to the applicability of any convention to any case, in spite of their roles as adjudicators and expounders of the meaning of the law and no matter how certain they personally are that certain conclusions must be deduced from the evidence. Their grant extends to the power to command such figures to honestly apply the convention to the information relevant to the specific case, and to punish any dishonesty for which they can produce specific warrant to the public, and no further; any assumption of power beyond this, renders disputation of offenses subject to despotism or atomic corruption.

Likewise, the adjudication system can rightfully have no grant of power to impose punishments on those convicted of offense which are without durable precedent, whether individually or cumulatively; such punishments are (at best) poorly tested in their effects as a corrective (assuming transitory precedent), and inherently could not have been foreseen by the offender and cannot fairly be deemed preventative. Furthermore, their relatively unprecedented nature is a sure sign of subjection to administrative power, if not personal corruption, and opens the civic door-way to an increasingly arbitrary despotism. Finally, adjudicating officers taking cases or appeals outside of the sphere of adjudication which has been designated for them by the public cannot but violate proper legal procedure, just as much as disputants questioning their right to officiate claims in the sphere which has been designated for them; in either circumstance, either assumption can scarcely be deemed impartial, as neither follows public direction. While the latter is a certain mark of a contemptuous disputant, the former is in the long run more dire, as it signals a tyrannical desire which knows no bounds other than its own sensibilities, unless it be that of the administration on which the power play of such a Star Chamber might depend; such a violation of proper legal procedure is among the most pressing, calling for the officers’ removal for their vicious behavior. (Judicial overstepping of any significant duration is likely to be dependent on despotic administration, as it is too clearly immoderate to be given more than transitory support by the public.)

#the adjudicative body#the adjudicative branch#the judicial branch#adjudicative co-ordinancy#the prestige of mature judgement#the infamy of immature judgement#the independent judiciary#relative harmlessness of an independent judiciary#de facto judicial supremacy#illegitimacy of de jure judicial supremacy#civil expectation of fair procedure#procedural due process#the fallacious doctrine of substantive due process#judicial review#equality before the law#precedential nature of law#balancing precedent and equity#strict scrutiny#reasonable basis test#legal security for judicial opinions#judicial removal for misbehavior#compulsory self-incriminatiion#the cruel trilemma of conviction perjury or contempt#prohibition of subsequent prosecution#double jeopardy#the civil right of appeal#appeal against unfair procedure#explicit constitutions#constitutional amendment#conviction on judicial determination of information

0 notes

Text

On the Public Will, Inheritance of Merit, and Liberty of Contract

The Principles of Oligarchy

On account of the natural limit to accumulation of resources previously mentioned, industry over a longer duration is only rendered practical by the affixing of enduring value generally to some article of exchange, commonly known as money. However, such affixing requires mutual submission to joint arbitration of its value, as it cannot endure naturally apart from use. As an inherent result of the underlying nature of acquired value, then, it is not inheritable from generation to generation, except by civil convention; in a complete reversion to nature, private estates would revert back to the world at large for any other person to appropriate as they will, as the merits of personal labor are not inherited by the subsequent generation simply by nature. That it is nevertheless commonly conceded that private estates may be inherited by the original acquirers' descendants in most societies, is a sure sign of the usual power of the desire to secure the welfare of one's personal posterity to motivate industry and its many indirect benefits for the general public. Yet, the inheritance of estate, so understood, hardly occurs by some absolute atomic dominion over such, but on account of its increasing the value of the common human estate. Hence, this general custom does nothing to dispel the reserved public power to regulate inheritance for the common good, should it become counterproductive.(Thus, the consolidation into the hands of a few lines of estates by inheritance may be regulated by the public to the extent that this may affect the general opportunity to acquire property, if perhaps practically unnecessary if their ancestors cannot consolidate property by obstructive or conspiratorial means.)

While public officers may merit special privileges and honors beyond the basic rights of private individuals for their services to the people, the inheritance of distinction is not natural, and the establishment of civil conventions to this end tends towards irrational obstruction of the public will, by suggesting that such a portion has greater natural right to determine its course. Yet societies have tended to establish civil conventions of hereditary privilege nonetheless, mistaking the civic grooming that commonly comes with being raised by those publicly distinguished for inheritance of meritorious character by being born to them. But by formalizing "merit" that is left untested, the necessity of their descendants meriting these special distinctions through their own labor on behalf of society is lessened, and the inclination to press their interests to the exclusion of others thus correspondingly increased, transforming them into a parasitical caste tending to conspire against the public good. Furthermore, while any class of society may justly enjoy the public prestige its members may collectively acquire by private industry valued highly by the public, it is similarly destructive of the common good to establish the inheritance of such prestige by the members of that class by convention. This principle remains true even if this "upper caste" is also the preponderant part of society.

The Market In An Open Society

As mentioned before, the affixing of enduring and general value to any given article of exchange requires mutual submission to joint arbitration of value, as it cannot endure naturally apart from use. Hence, while a civil society would not generally impose prohibitions on open deliberation in the market-place (as such is the principle of special privilege), neither should public administrators provide force to any agreement to waive natural liberties if it later becomes involuntary. For the liberty of contract is not an inherent liberty possessed by all simply by virtue of human nature, but rather a civil liberty presupposing that both parties have left the uncivil anomie of nature and entered into civil society with one another, if agreement is to mean anything more than one’s mere acquiescence. The civil liberty of contract, properly understood, cannot encompass an absolute license on the part of principal estates to require unconditional waiver of liberty of association from their contractors, and enforcing such presumption is foolish insofar as it indirectly privileges certain interests at the expense of others’ liberty. For if their presumption is supported by administrators, it is in the private interest of principal estates to tacitly combine to deprive contractors of bargaining power via mutual association, subjecting them to the despotism of their sensibilities. Conversely, if so supported, it is in the interest of bargaining associations to tacitly combine to deprive other contractors of the liberty of not associating with them, and so enforcement of either is in reality inimical to market openness and undermines its equilibration of value. (The contractual terms bargained for may regulate only those who participate in such associations, and conversely only participants may contractually benefit; the latter unreasonably forces participants to support non-contributors to the detriment of the association, while the former imposes terms on contractors without consent.)