Text

The Chinese periodic table

In Chinese, every element has a monosyllabic name with a character assigned to it. This makes the Chinese periodic table really cool, because every box has a unique character.

However, the monosyllabic names may cause confusion because many are homophones. New characters had to be created specifically for the recently discovered elements. Some of them do not exist in Unicode.

Some patterns can be observed in the table:

All gases have the 气 (steam) radical.

The liquid elements (mercury and bromine) have a 水 or 氵(water) radical.

All metals except mercury have a 金 or 钅(metal) radical.

Solid non-metals and metalloids have the 石 (stone) radical.

(Originally posted on Quora.)

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heard this stupid dad joke that killed me: Which Chinese word takes the longest to write? "Friend" (朋友) because it takes two months just to write half of it

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

After More Than Half a Century, a One-of-a-Kind Chinese Typewriter Emerges from Obscurity

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being really into Frankenstein while at the same time being Chinese is so funny because every time Lord Byron gets brought up, the way his name is pronounced always makes me think of the word 白人 (bái rén), which translates into “white guy”. Lord White Guy.

30K notes

·

View notes

Text

the close association between gui 鬼 as in "ghost" and gui 归 as in "to return, to go back to where you belong;" such that ghosts are coming back to the living and the living are coming back to ghostliness. these two states are two sides of the same coin, of the same existence.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pst btw if you've ever wanted to use / look at / make handwriting headcanons about Chinese calligraphy, this site allows you to search a character and then pulls up an image list of that character in tons of famous calligraphers' styles!!

It's also organized by different script styles (standard, seal, semi-cursive, cursive) for different uses!

If you click on the blue names under the pictures, the site pulls up a list of every character it has indexed as written by that particular calligrapher too, so very helpful to find individual styles : )

#ok this a super cool resource#but i am getting light headed thinking about how much i would have liked working on it#every day i encounter things i wish to hell i had thought of first#hanzi

791 notes

·

View notes

Text

May I present, the importance of tones:

382 notes

·

View notes

Text

OP: The Day My "Erciyuan" Identity Was Exposed at the Courier Station

(erciyuan二次元 is similar to otaku, describes people having an intense or obsessive interest with a particular topic especially in the fields of donghua, manhua, animation, manga, computer games, etc. erciyuan literally means two-dimensional space, which means that it is separate from the real world, because the things that erciyuan like usually exist only in two-dimensional space. this term is neutral giving that it doesn’t carry the derogatory sense that "otaku" might have.)

Cnetizens

#omg i love this#what a great way to learn a new word#a word i'm definitely going to need to know lol

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

A beginner-level resource I just learned about is LOTE4Kids: online bilingual picture books. My library sent out an email about it recently. If your library is a member you can search for their name or enter the LOTE4Kids site through your library's site. Simplified Chinese has four levels: 1 (40-90 words), 2 (90-220 words), 3 (220-540 words), and 4+ (540-1200+ words). There's currently 80 available languages. There's no ads on the web version but I don't know about the app. There's more than 100 books in Mandarin. You can take a quiz at the end of the book if you like. You can listen in your target language, or English, or both. I found the English voice actor really annoying but that's a small price to pay, I think.

#language learning resource#free language learning resource#bilingual children's books#bilingual picture books#lote4kids

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

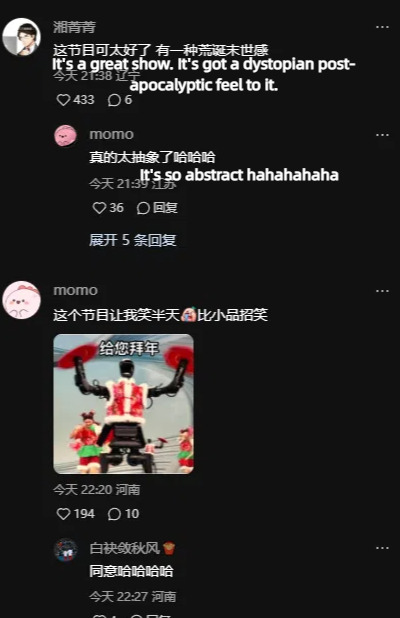

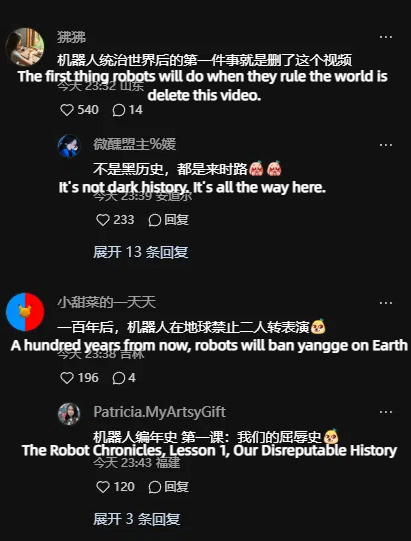

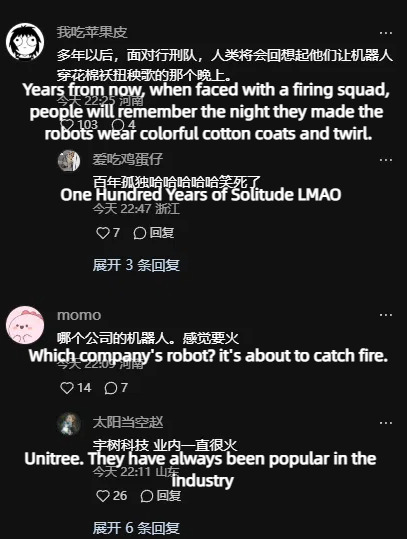

Spring Festival Gala for Chinese New Year tonight, robots and girls perform Northeast folk dance秧歌yangge with rice-planting music

Cnetizens: WTF is this LMAOOOOOO😭😭

Cnetizens say this is most 抽象chouxiang one in this year's SFG (抽象lit. abstract, similar to quirky, funny, weird, describes something so incomprehensible that one doesn't know whether it's serious or funny)

The video of UniTree's robots was posted a month ago HERE, where they tripped and fell in public and kicked a hole in the carpet, so how is it that all of a sudden they're flexible enough to make it to the Spring Festival Gala, omg this timeline is so chouxiang....

#抽象#chouxiang#posts like these are such a great way to learn vocab#you see it again and go OH! that's from the post about the weirdass dancing robots!

621 notes

·

View notes

Text

The known-ish words of intermediate Chinese, or: What does it mean to know a word?

We all have this intuition, especially in languages like Chinese, that there are words we 'kind of know'. These are the known-ish words. In the case of Chinese, most people would recognise at least three axes:

1) Do I know the meaning? 2) Do I know the pronunciation? 3) Do I know how to handwrite it?

You might answer yes to some, but no to others. Voila! You know the word - ish.

And then you can also add the dimension of passive and active knowledge:

1) Do I recognise this word passively? 2) Can I use this word actively?

Great. Even more ways of kind of but not really knowing a word. But that's far from all. There's also the different domains of listening and reading, writing and speaking.

So passively, that looks like:

1) Do I know the meaning when listening? 2) Do I know the meaning when reading? 3) Do I know the pronunciation when reading?

Once we add in the active dimension, it all starts to get a bit more complicated. This is far from an exhaustive list, but consider the follows ways you could define 'knowing' a word:

1) I can read the word out loud (but I don't know what it means, and I can't use it in a sentence) 2) I know what the word means, and I can use it in a sentence (but I can't handwrite it) 3) I can use the word in a spoken sentence (but I don't know how to type it, or which character it uses) 4) I can recognise the word when reading (but don't know how to read it out loud, and can only guess at the meaning) 5) I can use the word in a written sentence (but not a spoken sentence) 6) I can type the word and recognise the word (but I don't know how to handwrite it) 7) …

Okay. What else?

Chinese is a compounding language.

Have you ever had the experience that you can't recognise a character individually, but as soon as you see it in a familiar compound, you know what it means? So:

1) I can recognise the word individually 2) I can recognise the word as part of a compound 3) I can recognise the word as part of an unfamiliar compound

Chinese is also a language with a long and storied tradition of writing in Classical Chinese as a literary language and a lingua franca across the whole of East Asia - even two hundred years ago, people were writing in Literary Chinese. 'Mandarin' as a concept did not exist.

So often the meanings of familiar characters can be quite different in formal language or chengyu in the modern language, which uses more classical / literary structures and grammar.

Take, for example, the character 次. The first layer of meaning in modern Chinese - the most foundational layer - is its meaning as time, like 'I have been to Ghana two times'.

But its second layer of meaning is secondary, or next best, or just next. For example:

1) 次货 - substandard goods 2) 次子 - second son 3) 次年 - next year

And so on. Many common words have this kind of polysemy.

So we can add another dimension:

1) I recognise this word's common meanings 2) I can use this word's common meanings 3) I recognise this word's less common meanings 4) I can use this word's less common meanings

Add in the reading and listening dimensions, and things get even messier. I am familiar enough with this basic secondary meaning of 次 to fairly quickly be able to understand that it means 'next' or 'second' rather than 'time' if I see it in a written unfamiliar compound or chengyu. But I am most definitely not quick enough to do that every single time whilst listening to the news, for example!

And what about pronunciation? Once you know a fair amount of Chinese characters, you can often guess the pronunciation of new or unfamiliar characters. How?

Because of phonetic components.

For example:

请

清

情

Notice how these all have the same component on the right? This tells us that these characters belong to the largest group of Chinese characters, phonetic-semantic characters. That is - some part of the character gives a clue to the meaning, and some part gives a clue to the pronunciation. In this case, we know they are all pronounced some variety of qing.

But it isn't always that easy. Some phonetic components tell you the tone and pronunciation - some tell you the pronunciation, but not the tone (like qing above). Some phonetic components, to go even further, are only really decipherable if you have a particular interest in phonology or historical linguistics, or learn the patterns. Consider:

脸 - lian3 (face)

险 - xian3 (dangerous)

验 - yan4 (test)

剑 - jian4 (sword)

签 - qian1 (to sign)

捡 - jian3 (to pick up)

There are far more. If you look down the whole list on Pleco, they all show a similar pattern of variation. You can see some patterns, but also numerous exceptions - most end in the -ian final, except for those that are yan of various tones. All begin with l, x, y, j, q. Most are pronounced jian3, but that is far from a rule.

All this to say - you can see a character, and know vaguely how it is pronounced. If I know that a character is pronounced qing definitely, 100%, but don't know the tone - does that mean I know the pronunciation? Or would you only say that knowing it 100% means knowing it? And in that case - how can you account for the fact that learning a character when you already know 90% of the pronunciation is significantly easier than not knowing it at all?

Let me add just a few more scenarios. Bear with me!

1) A character has more than one way to be pronounced. For this word, you read it incorrectly (but you usually know it). 2) A character has more than one tone. Some people pronounce it always with one tone, and some alternate between the two pronunciations. You only knew it with one - but you're half right? 3) You make the same mistake that a native speaker would make with tone or pronunciation of a rarer character.

In some way, these are all more knowing than not knowing anything at all.

And none of this is even taking into account different writing systems, traditional and simplified.

Here are some more scenarios:

I recognise the character in traditional (but not simplified)

I can type the character in both, but I can only hand-write in simplified

I know the Taiwanese pronunciation, but not the Chinese

etc

And of course Chinese characters are used across multiple different languages.

So you could conceivably have these kinds of situations:

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Cantonese and Mandarin

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Cantonese, and the meaning in Mandarin

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Mandarin and recognise it in Cantonese, but know it means something different

I know the pronunciation in Mandarin, but don't know what the whole word actually means in Mongolian (Chinese characters used to transliterate Mongolian words)

Plus there's handwriting and calligraphy!

Personally, I can't read a lot of calligraphy and have accepted my happy illiteracy in many styles. All Chinese learners and heritage speakers know the feeling of sitting in a Chinese restaurant or museum and having a well-meaning friend say, 'Oooo, what does that say?' It's depressing! So let's add some more nuances to our known-ish characters:

I can read this character in common fonts

I can read this character in less common fonts

I can read this character when handwritten

I can read this character when handwritten quickly / by a child / by a doctor

I can read this character in grass script / seal script / etc

Then there's the question of naturalness.

I frequently add words to my Anki decks that I would be able to understand, no question, if I were reading or listening - but I probably wouldn't have thought to say it in that way. So:

I recognise this word, and would have said it exactly like this

I recognise this word, but would never have thought to say it like this

I can use this word, but didn't know you could use it in such a metaphorical way

I can use this word in a metaphorical way, but didn't realise it corresponded so closely to English / was so different from English in its meaning

And finally there's the simple question of memory.

I know I've seen this word before, but I can't remember it right now and I want to drown myself pathetically in the vast uncaring sea

I know I used to be able to use this word actively, but now can only use it passively

I can still type it, but have forgotten how to handwrite it

I can still use it in writing, but I wouldn't be able to use it in speaking

I can recognise it in set expressions, but wouldn't remember how to use it on its own

I can remember the simplified character, but not the traditional

…

So how many ways do you know a word?

I often feel embarrassed to post my vocabulary lists, because I feel that people will be surprised that I don't 'know' certain more foundational words. I think they will be confused as to why I have very 'advanced' vocabulary alongside 'simple' vocabulary. I feel a lot of pressure to be 'advanced' because of the amount of followers I have, but there's a lot of more basic characters I still don't fully know in a holistic way.

And the truth is that all of those characters and words are in Anki for different reasons. I might have a vocab list that looks like this:

略

松懈

星光

缕缕

薄雾

博览

I don't know any of these words in exactly the same dimensions as I know the others! Let's look at my reasons for including each in detail.

略 - lve4 - slightly. I have this word here because although I know it well in set expressions like 略有耳闻 'have heard a little about',略有受损 'has suffered slight losses' etc, I wouldn't remember the pronunciation if I saw it alone or with another verb apart from 有. I would still know the meaning - but I wouldn't remember how to pronounce it. So even though I 'know' this word, it's still there in Anki.

松懈 - song1xie4 - to relax, lax, slacken. This is a rare example of a totally 'new' word - most of my Anki words aren't. I know 松 already well, but have never seen the character 懈 before: I didn't know its meaning, or pronunciation.

星光 - xing1guang1 - starlight. I know both characters, pronunciation and meaning, and I can easily understand this word. I just never would have thought to say it so simply. I want to use it actively, so I put it in Anki.

缕缕 - lv3lv3 - fine and continuous (i.e. rain, drizzle). I know 缕 already on its own as a measure word for sunlight, thin hair, gossamer, mist, smoke, fine threads etc - I often forget its pronunciation, but I know its meaning reliably when reading. But together the compound 缕缕's meaning isn't quite extricable from just knowing 缕, so I put it in here.

薄雾 - bo2wu4 - mist, fog. I know 雾 well, but hadn't come across 薄 before (or wasn't sure if I had or not). This is an example where I knew its pronunciation, because of phonetic components, but I didn't know the meaning of the character.

博览 - bo2lan3 - to read widely. I know this word very well. So why is this in there? Literally just because I remembered the pronunciation and meaning of 博览, and when I was racking my brains trying to see if I knew the 薄 in 薄雾, I thought it might be the same character. I looked it up, and it wasn't. So even though I know the word, the meaning and the pronunciation, I had to put it in - because I didn't remember which character was used for the bo2.

When you acknowledge all of the different ways of knowing a Chinese character, it makes sense that your learning after the beginning level is going to be full predominantly of known-ish words.

Accept this! Form your own relationship to it! For me, a huge part in my motivation to return to learning Chinese after a year-long break was just to accept that I was likely never going to 'fully know' most of the characters and words that I partially know.

But that's okay. Think about your native language.

If your native language is English or you speak it very well, consider a word like monadic. Could you say you knew this word? Fully knew it? Like me (I learnt this word in the context of Linguistics yesterday), you might have an idea that it has something to do with one - mono, monorail, monotropism, monologue, monolithic etc. But would you be able to use it in a sentence? Would you be able to explain it to a child?

Or let's say you're learning two new English words: lithology and dreich. (The latter is a Scots word, not English - you would hear it in Scotland frequently.) Neither word you completely know. Which one is going to take you longer to learn?

It's likely going to be lithology. You can form connections with words like monolith or paleothic or maybe even lithium - even if you couldn't say for sure what the Greek element lith means, you're passingly familiar with other words containing it. You also know -ology, and you know how to pronounce the word. If you learn that it means 'the study of rocks', that is probably quite easy to remember.

Dreich, on the other hand - what is there to tell you a) how to pronounce this, or b) that it means 'dreary' or 'bleak', as in, dreary weather? You can't form any connections with similar words at all, and the [x] sound at the end - like in German or Hebrew - might be unexpected to hear if you don't live in Scotland.

That's what Chinese is like in the beginning. All words are like dreich. But the more you learn, the more words begin to be like monadic or lithology.

Learning ten new words a day like dreich would be very difficult. But if you've seen monadic a few times over the last few months, know vaguely when to use it, know how to pronounce it - it's not so hard to imagine that you could learn ten of those a day.

I find all these known-ish words very overwhelming.

And I also find recognising the potential for overwhelm in the Chinese language - because of its unique properties - very helpful in letting me feel less guilty about my current known-ish words. I do know them - ish.

But when I finally get around to properly learning them, all that ish-ness will make them that much easier to remember!

Now I try not to stress out about these types of words. I recognise that, in many ways, they are inevitable. Unless you're a poet who composes out of thin air, you're not going to ever say a literary word for emerald green as frequently as you'll read it in descriptive passages in novels.

It's natural to know certain words in a spiky profile: to know them very well in some ways, but not at all in other ways.

The more you read, the more pronounced this can become.

So here's what I've learnt, and here's the message of all this big, long, rambling post:

Putting 'easy' words that you feel you should know into Anki isn't regressing. It's adding another dimension of knowledge to your understanding of the word. You shouldn't feel ashamed or frustrated when you find you don't know one aspect of an otherwise 'easy' word. I'm still trying to learn this.

Because -

Having lots of known-ish words is not a unique failing on your part. It's a reflection of Chinese as a language and its unique complexity -

And it's part of what makes it so uniquely beautiful.

Have a nice day, everyone. meichenxi out!

#oh boy#this is a little daunting but also so very very interesting#chinese is one of the most fascinating languages i've studied

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

I bought a set of kid's writing practice books on AliExpress to learn some basic 汉字 and their stroke order.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

*The word is comprised of 女 (nǚ; girl) + 哥 (gē; older brother), as the comment of the above douyin is that the man has a girlish face so the user is combining the appellation 姐 (jiě; older sister) and 哥.

My Note: Fascinating! This character, 𡟵, exists in the extended unicode but has no real dictionary definition that I can find anywhere. The most information I have been able to find on this word in both English and Chinese is that it seems to be pronounced gō in Cantonese (which, as one might expect looking at the word, indicates it would be gē in Mandarin). This seems to suggest that it has usage in Cantonese, but I haven't found any further explanation! The unicode character is part of CJK Unified Ideographs Extension B but as far as I can find, it doesn't have any historical usage in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese or as a variant of any kind.

990 notes

·

View notes

Text

important culture exchange happening rn

68K notes

·

View notes