Text

Thank you

Thank you for embarking on this journey with me. I hope you learned as much as I did!

______________________________________________________________

All of my sources for each text post are below as well as at the bottom of each post, recipes, and individual image posts are not included:

Sources:

Agricultural Issues Center, University of California. The Walnut Industry in California: Trends, Issues, and Challenges. 1994.

California Walnuts. 2019. https://walnuts.org/

California Walnut Objective Measurement Report. USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service. 2019.

Del Lungo S, Ciolfi M, et al. Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: Its origins and human interactions. 2017; PLOS ONE 12(3): e0172541

Delaviz H., Mohammadi J., Ghalamfarsa G., Mohammadi B., & Farhadi N. A review study on phytochemistry and pharmacology applications of Juglans regia plant. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2017;11:145–152

Doty, K.. Comparison of Aluminum Mordanted and Nonmordanted Wool and Cotton Dyed with Walnut. 2013. https://www.kon.org/urc/v12/doty.html

Frye, L. The most popular furniture woods: the historic perspective. Wood and Wood Prod. 1996; 100(14):304-307

Leslie C, Hacket W, Robinson R, Grant J, Lampinen B, Anderson K, Beede B, Buchner R, Caprile J, DeBuse C, Elkins R, Hasey J, Vahdati K, Kluepfel D, Brown G, McKenry M, & Preece J. Clonal Propagation of Walnut Rootstock Genotypes for Genetic Improvement 2011. California Walnut Board.

Martínez-García P., Crepeau M., Puiu D., Gonzalez-Ibeas D., Whalen J., Stevens K., Paul R., Butterfield T., Britton M., Reagan R., Chakraborty S., Walawage S., Vasquez-Gross H., Cardeno C., Famula R., Pratt K., Kuruganti S., Aradhya M., Leslie C., Dandekar A., Salzberg S., Wegrzyn J., Langley C., & Neale D. The walnut (Juglans regia) genome sequence reveals diversity in genes coding for the biosynthesis of non-structural polyphenols. Plant Journal. 2016;87(5):507-32. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13207

Municipal Cod, Tehama County, CA, Chapter 6.40 - Purchase and Sale of Walnut Crops: https://library.municode.com/ca/tehama_county/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT6BULIRE_CH6.40PUSAWACR

National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Smart Blast. https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/smartblast/smartBlast.cgi

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Agriculture and the environment. https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/agriculture-and-the-environment/

Jepson P., Radcliffe E., Hutchison W., & Cancelado R. Integrated Pest Management, ed: Chapter 16. Published by Cambridge University Press 2009.

Pollegioni P., Woeste K., Chiocchini F., Del Lungo S., Ciolfi M, Olimpieri I. Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: Its origins and human interactions. 2017; PLoS ONE 12(3): e0172541.

Sande D., Mullen J., Wetzstein M., & Houston J. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011; 8(12): 4649–4661. Published online 2011 Dec 14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8124649

University of California Cooperative Extension Agriculture and Natural Resources Agricultural Issues Center. Sample Costs to Establish and Produce English Walnuts in Sacramento Valley. 2018.

University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Walnut Improvement Program. http://walnutrootstock.ucanr.edu/WIP/

University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. Walnut Propagation. http://fruitandnuteducation.ucdavis.edu/fruitnutproduction/Walnut/Walnut_Propagation/

University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program. Walnut Agriculture: Pest Management Guidelines. https://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/walnut/

University of California. UC Drought Management. Walnuts. http://ucmanagedrought.ucdavis.edu/Agriculture/Crop_Irrigation_Strategies/Walnuts/

USGS. Investigating the Environmental Effects of Agriculture Practices on Natural Resources 2007.

0 notes

Photo

Proposed seven year timeline, subject to change and will differ depending on how long the processes take.

0 notes

Text

Official Walnut Proposal

Upon further research in order to develop my approach to solve the problems I’ve outlined in previous blog posts I realized that the University of California, Davis has already implemented thoroughly developed solutions so I will be “piggy-backing” off their idea. Their Walnut Improvement Program has been around since 1948 and they’ve continuously conducted genetic research and implemented disease resistant scions (Walnut Improvement Program). I’ll outline an integrated approach about how I’d approach the solution, but I’m sure it will coincide with their research so I will be referring back to their timeline to create my own, which you can view on my page.

I’m proposing a seven year research plan to develop new rootstock genotypes to fend off the bacterial infection Brennaria (=Erwinia) rubrifaciens, also known as the deep bark canker infections that causes the scaffolds and trunks to crack while reddish brown ooze seeps through. This plan can be used for any bacterial pathogen, but I am using Brennaria rubrifaciens as an example. Since the disease begins in the trunk and works its way upward, I think it would prove to be beneficial to develop a successful rootstock lineage.

I will begin in January 2020 and expect for my first orchard trials to begin 2024. Since the deep bark canker infections are not occurring in native walnut trees or walnut orchards near the coast I’ll travel to Southern and Northern California with two other individuals to collect cuttings from the wild type black walnuts that are present. I will then work my way back east, stopping at the coastal orchard of Santa Clara Nut Company in San Jose and then move to the orchards where I will have my trials - Concar Ranch and Chiappi Farms to collect cuttings of the Paradox hybrid, English Walnut, and other hybrids present. After returning to campus at UC Davis I will use a greenhouse in orchard park with a few undergraduate students who will help me breed the plants in the greenhouse. While the breeding takes place and the walnut plants continue to grow I will move to Wickson Hall to work in lab 1092 closely with Walnut Improvement Program lab technicians.

I expect the next process will take two years to complete. Next I will extract the DNA from the wild walnut types with the help of lab assistants and once I compare my genes next to the genetic sequence of the walnut genome (A J. regia genome sequence was obtained from the cultivar 'Chandler' to discover target genes and additional unknown genes) (Martinez-Garcia, PJ. et al. 2016) I will use Smart Blast to find the specific location of the gene. Once the gene is isolated I will insert it into a plasmid along with the bacteria Brennaria (=Erwinia) rubrifaciens, which will then be inserted into media to see if a reaction forms. If a reaction does form and the bacteria spreads I will isolate the gene once again and compare against a non-coastal species in Smart Blast. If the gene reacts this means it is not resistant to the bacteria, if it does not react then it means it is resistant. If it is not resistant I will need to find another gene or go through the same process with a different species of walnuts. I anticipate If it doesn’t react then I have found the gene or genes I would like to implement into the non-coastal species and I will splice the gene into a plasmid vector to create a gene construct. Each successful resistant found will be a new genotype that, with the help of a molecular biologist, will be introduced to non-coastal species that do not have the resistant gene through transgenesis.

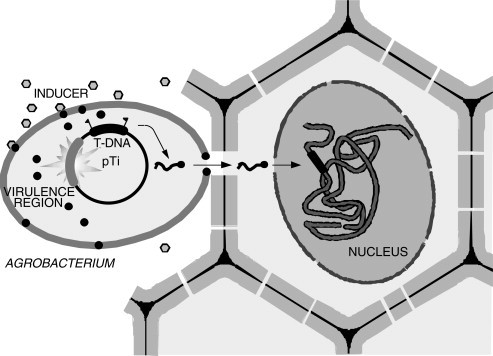

With the help of lab assistants I will transform the non-coastal species with Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Figure 1). Using the non-coastal species of the Northern California Black Walnut (for example) I will infect the plant with Agrobacterium tumefacians which will highlight the T-region, allowing me to integrate the successful genotype into non-coastal Northern California Black Walnut. From here I will continue tissue culture micropropagation with in vitro and ex vitro rooting of microshoots to make the genotypes strong enough to be acclimated to the greenhouse. I will also use dormant hardwood cuttings from the plants in the greenhouse to clonally propagated if they were tested successful for the resistant gene. While the plants are being propagated they will remain in a hormone induced media kept inside rectangular magentas held to a 99% humidity level under constant light. This means that when it’s time to acclimate the plant to the greenhouse we have to place the plants in a dark box for a week so they learn to adjust to a dark setting; this also ensures the plants can go through their respective Calvin cycles.

Figure 1. Scheme of T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to a plant cell

The successful genotypes will remain in the greenhouse for two years before being taken to the field site to test in an orchard setting. I will need all hands on deck at the farm and in the greenhouse to perform these orchard trials. I will need help transporting, transplanting, and monitoring the orchards. Using the UC Davis designated orchard trial areas I will perform my studies at Concar Ranch and Chiappi Farms. Throughout the next two years I will collect bark and nut samples to evaluate in the lab for the disease and evaluate the plants for horticultural performance and natural occurence of bacteria disease. While the orchard trials are occurring a team of lab assistants are in the lab continuing creating tissue cultures of microshoots. Once everything has been tried and true I will contribute cultures on microshoots to any laboratory or nursery that wants them for licensed production of plants (Leslie, C. et al. 2011). The experiment will conclude in September of 2027 after harvest.

Possible Pitfalls

With any experiment or solutions to major problems pitfalls will ensue. I predict a likely pitfall would be that the bacteria I am studying for resistance will mutate before I completed with my trials, creating sub species in a bid to recreate the environment it came from. In order to anticipate for this I will precisely monitor my project for any mutations that will reside. Another pitfall that is likely to occur is that entire lineages of my genotype will become infected with a different bacteria, which would cause me to dispose of the micropropagation plants and start over. This one would be difficult to foresee, but if I plan ahead and have enough plants in the greenhouse to sequence I will have more opportunities to start over.

.

.

.

Sources:

Leslie C, Hacket W, Robinson R, Grant J, Lampinen B, Anderson K, Beede B, Buchner R, Caprile J, DeBuse C, Elkins R, Hasey J, Vahdati K, Kluepfel D, Brown G, McKenry M, & Preece J. Clonal Propagation of Walnut Rootstock Genotypes for Genetic Improvement 2011. California Walnut Board.

Martínez-García PJ, Crepeau MW, Puiu D, Gonzalez-Ibeas D, Whalen J, Stevens KA, Paul R, Butterfield TS, Britton MT, Reagan RL, Chakraborty S, Walawage SL, Vasquez-Gross HA, Cardeno C, Famula RA, Pratt K, Kuruganti S, Aradhya MK, Leslie CA, Dandekar AM, Salzberg SL, Wegrzyn JL, Langley CH, & Neale DB. The walnut (Juglans regia) genome sequence reveals diversity in genes coding for the biosynthesis of non-structural polyphenols. Plant Journal. 2016 Sep;87(5):507-32. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13207

National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Smart Blast. https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/smartblast/smartBlast.cgi

University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Walnut Improvement Program. http://walnutrootstock.ucanr.edu/WIP/

0 notes

Photo

Walnut Grove Standing, Photo by William A. Garnett, 1953

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breeding and Bio-engineering Solutions

A step in the right direction...

Although it is not possible to solve the entire environmental and pest problem we are moving in the right direction. I’m proposing a broader approach to what University of California, Davis is already pursuing. They’re work is nothing short of amazing so I want to make sure I highlight them as much as possible. If we were to combine everything I’m about to tell you we’d be able to set California walnuts up for a long-lasting future.

Using both traditional breeding methods through forward genetics and bio-engineering approaches through reverse genetics I am proposing that F2 plants that were created from a few different walnut species be evaluated for a herbicide resistance gene. Once the right line has been chosen myself and a team will use the gene database software Smartblast to code for the specific gene. Once the sequence has been found we will introduce the gene into plasmid to see what bacteria can metabolize the gene and move forward with transgenesis. Transgenesis will be implemented through tissue cultures and clonal propagation will begin. Using the transgenic plants along with integrated pest management practices, specifically monitoring of pests we can combine a series of solutions.

If it works...

This would be positive for the environment because it is less invasive and leads to a decrease in pesticide use. It’s not harmful to birds, deer, or other wildlife that finds themselves in an orchard time from time. It will be costly, but in the long run once the genetic modifications are implemented for a few years there will be less need for other approaches such as pesticide use and pest management. Although I must say that I think using transgenic plants, biological controls, and pesticides for some time will decrease overall resistance of the pest/pathogen. I foresee a little pushback from politics because of the public’s perception of genetically modified organisms, but if it produces a nut that is larger and creates a higher yield the government will stand behind the product.

If this approach was implemented correctly, the public may steer clear of the crop because it is genetically modified; however, if marketing and publicity begins to be geared in a positive light it may help them see that in the end, it is better than using high levels of pesticides and it is less damaging to wildlife and ourselves. It would be important to have a public relations firm on board to develop marketing plans in order to change the overall perception.

Farmers may be reluctant to use the varieties I create because it is foreign to them and will cost more at first, but after my work is approved by the California Walnut Board and I eventually work with UCD’s Walnut Improvement Program who already have similar plans in action they’ll feel more comfortable working with me.

0 notes

Text

Perfect Dinner Recipe

INGREDIENTS

PICKLED VEGETABLES:

1/2 cup fresh lime juice

1 1/2 teaspoons sugar

3/4 teaspoon sea salt

8 radishes, thinly sliced

2 medium jalapeno peppers, thinly sliced

1 large clove garlic, thinly sliced

CALIFORNIA WALNUT CHORIZO CRUMBLE

1 1/2 cups or (or 15-oz. can) black beans, rinsed and drained

2 cups walnuts

3 tablespoons olive or vegetable oil, divided

1 tablespoon white vinegar

1 tablespoon smoked paprika

1 tablespoon Ancho chili powder

1 teaspoon dried oregano

1 teaspoon kosher or sea salt

1 teaspoon chipotle, ground

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1 teaspoon ground coriander

TACOS

16 whole wheat tortillas

Olive oil or olive oil cooking spray

Thinly sliced romaine lettuce

Fresh cilantro leaves

Lime wedges

PREPARATION

Stir together lime juice, sugar and sea salt in a small bowl. Stir in radish, jalapeno and garlic slices and let stand for 30 minutes to pickle.

Meanwhile, to prepare “chorizo” crumble, place walnuts and beans in a food processor; pulse until coarsely chopped.

Add 2 tablespoons oil and remaining crumble ingredients to food processor and pulse again until mixture is finely chopped and resembles ground meat, stirring several times and moving the mixture from the bottom of the food processor bowl to the top to evenly mix.

Heat 1 tablespoon oil in a very large nonstick skillet over medium heat. Add “chorizo” mixture to skillet and cook for 10 minutes or until mixture is nicely browned and resembles ground meat, stirring frequently. (May be prepared several days ahead and stored tightly covered in the refrigerator.)

Brush each tortilla lightly with oil or coat with cooking spray. Cook briefly on a griddle or skillet over medium-high heat to brown on both sides, keeping warm in foil until all tortillas are cooked.

Remove pickled vegetables from liquid and discard garlic slices. Fill each tortilla with equal amounts of “chorizo” and pickled vegetables. Garnish with lettuce and cilantro and serve with lime wedges.

Source:

https://walnuts.org/recipe/walnut-chorizo-tacos-with-pickled-vegetables/

0 notes

Text

Breeding and Bio-engineering Approach

How do we solve an everlasting problem...the environment?

The hardest answer to swallow is the right one, because we can’t. We can’t save a world that has already reached its peak threshold. We can try to lessen our impact locally to hopefully decrease damage to the environment and hope for a better crop at the same time.

The environment is heavily affected by agriculture in many ways, but I am going to focus on the issue that an increase in pesticide use is occurring due to the developed resistance of pests and pathogens, what’s currently being done in the field, and how the potential uses of plant breeding and bio-engineering will reduce environmental impact and pest resistance. Pests and pathogens damage the roots, stalk, leaves, and nuts themselves, which leads to farmers using integrated pest management, biological controls, conventional methods, and working with plant breeders to develop hybrid rootstocks of walnuts that are resistant to pests and pathogens. The increase in pesticide use to kill off pests also has damaging environmental effects so lets focus on that before diving into solutions. Environmental contamination occurs when pesticides are delivered to the sites of treatment by very inefficient processes including spray application, that result in only a tiny fraction of the applied material reaching the intended target organism while the large proportion of the chemical is wasted (Jepson, P. 2009).

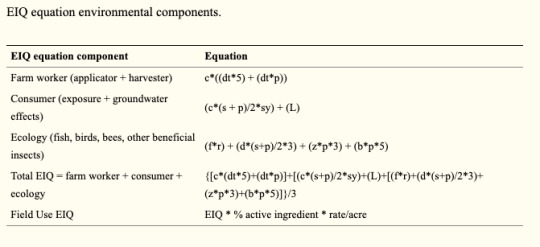

The increase in pesticides leads to increased runoff into the water supply, killing wildlife that drink from puddles or streams nearby and leaching into our water systems. Samples collected from 1992 to 2001 showed that at least one pesticide compound was detected 97 percent of the time in streams and 61 percent of the time in shallow ground water (USGS, 2007). An Environmental Impact Quotient (EIQ) was created by Cornell University’s Environmental Risk Analysis Program to gauge how pesticides affect farm worker (applicator and harvester), consumer (exposure and groundwater effects), and ecology (fish, birds, bees and other beneficial insects). I’ve included the equations used in figure 1 and results from their study in figure 2 below (Sande, D. et al. 2011).

Figure 1. Environmental Impact Quotient equations that has been used to assess pesticide or pest management, including integrated pest management programs environmental damage.

Figure 2. Common fumigants EIQ by environmental category. Workers and beneficial arthropods are the most likely to be affected by all fumigants. All alternative fumigants have the highest impacts on workers and second highest effects to beneficial arthropods.

Pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides are actually a good thing in terms of pest management because they can rid the crop of pests and pathogens, enabling for a faster turnaround in harvest times and the continuation of the crop for another season. Due to a public push to use less pesticides farmers are looking for other methods because there is a problem. If there is only one pesticide that can be used on crops the farmers won’t be able to alternate between different ones once the pest becomes resistant, giving the pest opportunity to spread to the point of no return.

.

.

.

Sources:

Paul C. Jepson, Edward B. Radcliffe, William D. Hutchison, & Rafael E. Cancelado. Integrated Pest Management, ed: Chapter 16. Published by Cambridge University Press 2009.

Doris Sande, Jeffrey Mullen, Michael Wetzstein, & Jack Houston. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Dec; 8(12): 4649–4661. Published online 2011 Dec 14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8124649

USGS. 2007. Investigating the Environmental Effects of Agriculture Practices on Natural Resources https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3001/pdf/508FS2007_3001.pdf

Agricultural Issues Center, University of California. The Walnut Industry in California: Trends, Issues, and Challenges. 1994.

0 notes

Photo

Source:

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/An-unripe-and-young-walnut-fruit-before-its-husk-cracks-and-the-ripe-form-of-the-fruit_fig1_335177625

0 notes

Photo

Source:

https://news.psu.edu/story/572467/2019/05/01/research/walnuts-may-help-lower-blood-pressure-those-risk-heart-disease

0 notes

Text

Social, Political, Economic, and Environmental Impacts

So what’s going on with the control of production and sales of the walnut?

The current board for California walnuts is the California Walnut Board. They are governed by a Federal Walnut Marketing Order and they provide funding for walnut production and post-harvest research. The agricultural commissioner oversees commercial buying and selling of walnut crops and follow a strict municipal code and the United States Department of Agriculture is responsible for developing and executing the federal laws .

Does everyone have access to the luxury of walnuts?

Walnuts are sold at supermarkets nationwide and are available along all demographic groups thanks to the Diversity Committee administered by the CA Walnut Board and CA Walnut Commission. They are typically sold as a snack item or for use as an ingredient in candies, cereals and baked goods making them available at gas stations, supermarkets, restaurants, and you can even harvest them on the side of the road during fruiting season.

Everyone talks about it - what are the environmental impacts?

Walnut crops don’t offer many positives for the environment except for the fact that the native tree, the Northern California Black Walnut offers a habitat for pollinators and natural enemies of pests and that they are improving on their agricultural practices such as using IPM practices over conventional. For negatives there is the potential runoff of the chemical controls in the crops into the water system and the chemicals being released into the air, increased pesticide use to rid the walnut of pathogens and pests, the killing of native wildlife that are considered as pests and disrupting ecosystems, and creating habitat fragmentation and removing habitat from an area

Manual and/or Mechanical Labor Needed?

Yes, the production requires both manual and mechanical labor - pruning, fertilization, irrigation, pest management, and harvesting all require manual and mechanical labor. Propagation is done through sexual and vegetative propagation - sexual propagation is done once seeds are collected after the mechanical shaking process and vegetative propagation is completed using manual labor

How is the cost and price of the walnut influenced?

With China as the leading consumer, trade is a huge influence on pricing around the world. For all of walnuts, the price is effected by supply and demand, policy and exchange rate

.

.

.

Sources:

Agricultural Issues Center, University of California. The Walnut Industry in California: Trends, Issues, and Challenges. 1994.

California Walnuts, Boards and Committees https://walnuts.org/about-us/boards-and-committees/

Municipal Cod, Tehama County, CA, Chapter 6.40 - Purchase and Sale of Walnut Crops: https://library.municode.com/ca/tehama_county/codes/code_of_ordinances?nodeId=TIT6BULIRE_CH6.40PUSAWACR

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Agriculture and the environment. https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/agriculture-and-the-environment/

University of California Cooperative Extension Agriculture and Natural Resources Agricultural Issues Center. Sample Costs to Establish and Produce English Walnuts in Sacramento Valley. 2018.

USGS. 2007. Investigating the Environmental Effects of Agriculture Practices on Natural Resources https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3001/pdf/508FS2007_3001.pdf

0 notes

Text

The Crop

Where did they come from?

I’ll say, after researching the origins of the walnut it is rather difficult to pin down the appropriate timeline, but luckily new data and resources of the crop’s origin, including the development of molecular markers. such as Simple sequence repeats markers, recent advent of landscape genetics, persistence of centuries-old walnut trees in natural reserves isolated from plantations, access to remote uncultivated Asian walnut populations and a rich fossil pollen record in Europe, provide more information as to when the wild plant became domesticated by humans and shaped the evolutionary history of walnut (Pollegioni et al. 2017).

I’ll be focusing on the most commonly used walnut in crops within California is the English walnut also known as the Persian walnut, Juglans regia, and it is believed to be from Asia before being dispersed across several parts of Europe in the late Holocene age (Fig. 1); archaeological evidence of fossil pollen deposits indicates the spread of J. regia. It wasn’t brought to California until the 1700s by Spanish missionaries. Commercial walnut production began in the 1800s. In recent years California grows most of the United States’ walnuts, in 2018 there was 676,000 tons produced in California alone (CA Walnut Objective Measurement Report, 2019).

Fig. 1 - Dispersal routes of walnut during Late Holocene

How is the walnut produced, distributed, and stored?

The walnut industry has nearly 100 handlers and 4,800+ growers spread across California’s Central Valley alone and the California Walnut Board and California Walnut Commission represent them. Walnuts are harvested in late August after their flowers bloom in late Spring. The walnuts require manual labor and shaking machines to remove from the trees. Then the walnuts’ green husk is removed, the nut is washed and air-dried to a certain moisture level, they are then transported to a packing plant where they are selected based on usage before being distributed and sold domestically and through exports.

Propagation and Growing of the Walnut

US Walnuts are grown in the Central Valley of California and in the mid-western United States. Many different types of propagation are used in the walnut nursery industry to create finished propagated trees for orchard planting including sexual propagation (rootstocks only), micro-propagation, cuttings, budding, and grafting. Rootstocks for instance are created using the native Northern California Black Walnut (Juglans hindsii) and the hybrid ‘Paradox’ (J. hindsii x J. regia) and is favored in the industry currently.

UC Davis has a Walnut Improvement Program is where lab propagation through transgenic plants occurs (I’ll go into more detail about their process in an upcoming post) in order to improve the walnut to make it larger and less susceptible to diseases and/or pests.

What pests and environmental conditions do growers need to watch out for?

There are about 18 different pests affecting the Walnut in California and about 12 different diseases making the production of the crop difficult, which is why the University of California has implemented a statewide Integrated Pest Management Program that can be found online. It is indeed very handy! I love to use it when looking at different diseases and to see how to fight them.

Environmentally speaking, the walnut needs plenty of water to grow, drought slows the growth of the walnut tree and can cause die back, decreasing the nut size and lowering its carbohydrate properties. I’ve included a chart showcasing the effects of drought by development in Figure 2.

Figure 2 - Drought effects on the Walnut development

.

.

.

Sources:

California Walnuts, 2019. Walnut Industry. https://walnuts.org/walnut-industry/

California Walnut Objective Measurement Report (August 30, 2019) USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service

F, Del Lungo S, Ciolfi M, et al. (2017) Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: Its origins and human interactions. PLOS ONE 12(3): e0172541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172541https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0172541

Pollegioni P, Woeste K, Chiocchini F, Del Lungo S, Ciolfi M, Olimpieri I, et al. (2017) Rethinking the history of common walnut (Juglans regia L.) in Europe: Its origins and human interactions. PLoS ONE 12(3): e0172541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172541Pollegioni P, Woeste K, Chiocchini

University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. Walnut Propagation. http://fruitandnuteducation.ucdavis.edu/fruitnutproduction/Walnut/Walnut_Propagation/

University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. Statewide Integrated Pest Management Program. Walnut Agriculture: Pest Management Guidelines. https://www2.ipm.ucanr.edu/agriculture/walnut/

University of California. UC Drought Management. Walnuts. http://ucmanagedrought.ucdavis.edu/Agriculture/Crop_Irrigation_Strategies/Walnuts/

0 notes

Text

Orange Turmeric & Vanilla Yogurt Smoothie

Total Time - 5 Mins

Serves- 2

Ingredients

1/2 cup frozen mango cubes

1/2 cup orange juice

1/4 cup vanilla yogurt

2 tablespoons California Walnuts

1 tablespoon honey

1/2 teaspoon turmeric

1/4 teaspoon cinnamon

1/4 teaspoon vanilla extract1 frozen banana

Procedure

Place all ingredients in a high speed blender and blend until smooth.

Source: https://walnuts.org/recipe/orange-turmeric-vanilla-yogurt-smoothie/

0 notes

Photo

Creamy peach & walnut ice cream / vegan, gluten-free.

719 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Industry

I’ve always wondered who was behind the walnut, who are the consumers, stakeholders, and producers? The answer is, is that its whoever touches a walnut, picks a walnut, grows a walnut, researches the walnut, or even manages the walnut. They all have something to do with the industry. The stakeholders include the California Walnut Board, University of California, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), farm advisors, walnut growers, pest control advisors and Integrated Pest Management (IPM) product suppliers. All of those companies and people have a say in what the walnut industry puts forth.

I’d like to highlight the California Walnut Board, established in 1948, because if the walnut crop could have one sole owner, it would be the board. They’re responsible for all of the walnut growers and handlers of California, they oversee rules and regulations, cultural practices, policy, funding for walnut production, and funding for post-harvest research. The California Walnut Board is also responsible for developing promotions for the usage of walnuts in the United States through publicity and educational program

The Consumers

94% of walnut consumers care about finding creative ways to explore a balanced diet and want to use walnuts in a variety of occasions such as cookies, baking mixes, cakes, pastries, salad toppings, and even cocktails. Consumers also practice sustainability by using sponges or even cat litter made from walnut shells. Which brings me to another aspect of the industry…

The Products

What is currently being used with the walnut? It can be used as a variety of products, it is directly used for food, distributed throughout cooked food or eaten raw. Furniture enthusiasts and the lumber industry use walnut because it’s a hardwood. Hardwoods are a broad collection of species with variations in color, density, and other physical properties. Because hardwood lumber demand is influenced by style, different species are dominant at different times (Frye 1996). The eco-friendly, fashion forward consumer can extract dye from the bark and gulls of Juglans nigra, the black walnut tree, to use on cotton as well as wool. The process of using brown dye from the walnut tree has traces all the way back to the Meskwaki tribe of the Great Lakes who used powder from grinding up bark to dye their clothes (Doty 2013). We are currently using walnuts in a variety of products, but I believe there are more uses for the crop.

The Potential

Walnuts are not seen as a potential pharmaceutical plant, but it has a wide range of different properties making it a great contender of therapeutic activities such as antioxidants, anti-diabetic, hypolipidemic, antimicrobial, and antihypertensive activities (Mohammadi et al. 2017). The shells of walnuts are flammable and highly fibrous making it a great option for fuel when combined with peat, when the shells are ground up they can be used for cleaning of cast iron skillets, placed in sponges for a renewable form of cleaning (the sponges can be sanitized through boiling).

Sources

California Walnuts. 2016. Root to Nut with California Walnuts.

California Walnuts. 2019. Consumer Research and Demand.

California Walnuts. 2019. California Walnuts, Boards and Committees.

Delaviz H., Mohammadi J., Ghalamfarsa G., Mohammadi B., Farhadi N. A review study on phytochemistry and pharmacology applications of Juglans regia plant. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2017;11:145–152

Doty, K. 2013. Comparison of Aluminum Mordanted and Nonmordanted Wool and Cotton Dyed with Walnut. https://www.kon.org/urc/v12/doty.html

Frye, L. 1996. The most popular furniture woods: the historic perspective. Wood and Wood Prod. 100(14):304-307

0 notes

Photo

United States. Agricultural Research Service, Putting Wild Bees to Work, 1973

840 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who am I and who are you?

My name is Elizabeth Rennie and I’m here to relay information to you about the walnut industry in California. We will embark on a journey to talk about how the industry operates, how the crop gets into your hands, what exactly is the genome and how can we manipulate the walnut to produce pest-resistant, pathogen-resistant and a higher yielding product.

So - who am I?

I’m an aspiring plant pathologist and I am currently an undergraduate at University California, Davis studying plant sciences.. I am curious to know more about the walnut crop and its susceptibility to pathogens and how transgenic plants are used to boost the crop in the field. I’d also like to see how the industry is currently using the nut to create higher yields, but not jeopardizing sustainability.

Who do I think you are?

Aspiring plant scientists, plant admirers, agriculture enthusiasts and/or people who love walnuts and are looking for more background about the crop. I think you’re interested in learning where the walnut comes from, how it ended up to be a main agricultural crop in the US, how it’s health properties benefit you and how you can use it in the kitchen, sustainable agriculture practices in place and how they can improve in regards to pests and diseases.

0 notes