Thoughts on #creativity, #digitalculture, #newwork and #designthinking

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Japan's Disposable Workers

I saw “Net Cafe Refugees“ at the World Press Photo 2015 in Amsterdam and all three sections - Overworked to Suicide, Net Cafe Refugees & Dumping Ground - are a must see!

After the recession of the 1990s, Japan’s white collar salarymen increasingly must work arduous hours for fear of losing their jobs. This often leads to depression and suicide.

Watch all videos here:

http://mediastorm.com/clients/japans-disposable-workers-for-pulitzer-center

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

What we actually want from those in creative roles is courage… The courage to break through boundaries, to see things differently, the daring to not conform.

Sharon Salzberg answers the question: “Does creativity have to come from suffering?” (via creativesomething)

195 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Agency culture is the result of many factors and influences, but a healthy environment is one that encourages team members to speak up; that fosters inspiration through collective brainstorming and problem-solving; that doesn’t micro-analyze the way time is spent; and that enables employees to listen to and learn from one another.

Great read: "Resetting Agency Culture" A List Apart - http://alistapart.com/article/resetting-agency-culture

2 notes

·

View notes

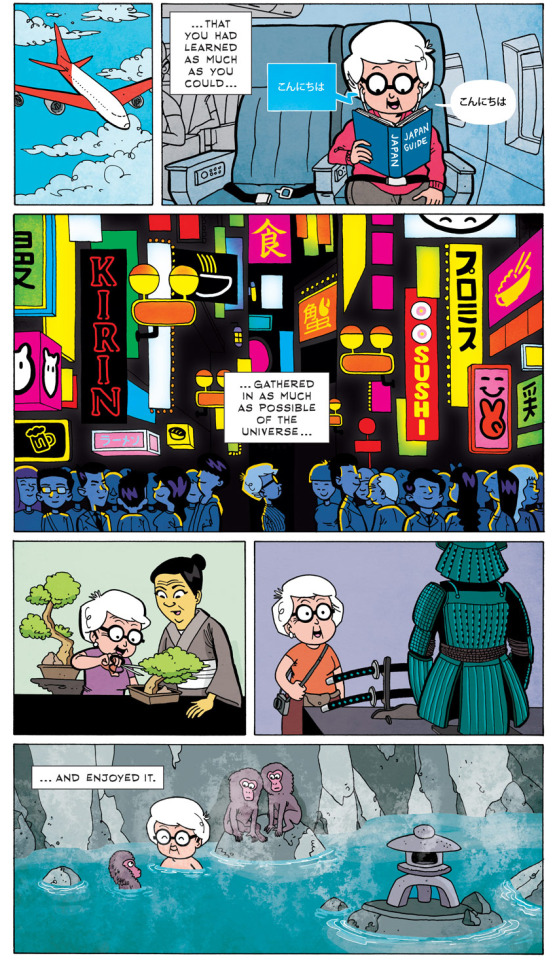

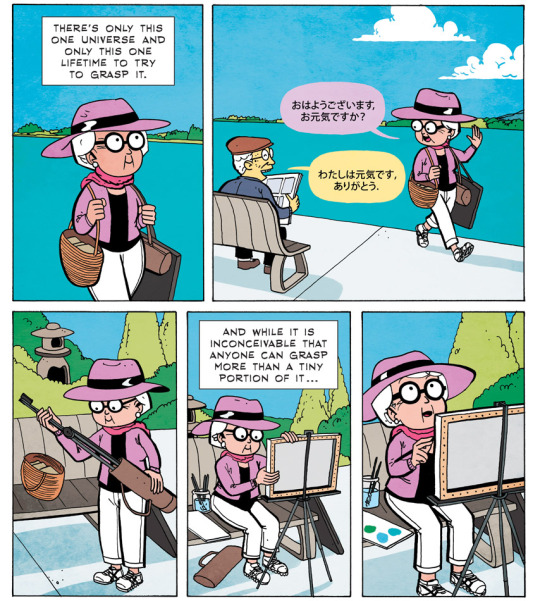

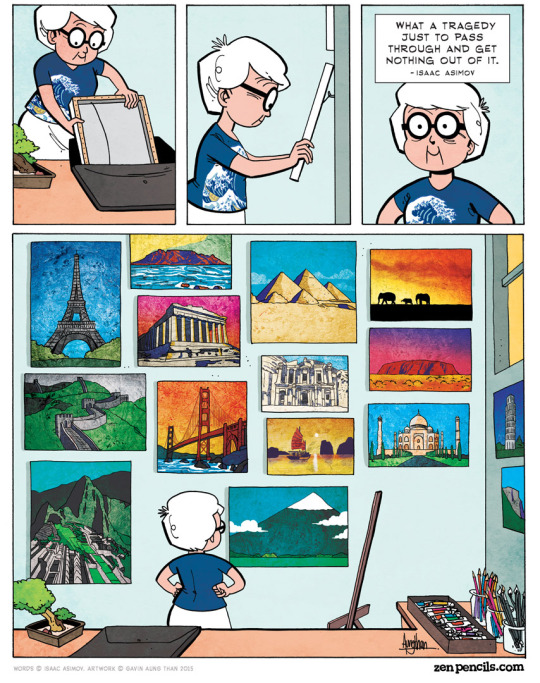

Photo

Always remember :)

“The world is your playground - not your prison”

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

8,024 Post-It Notes Cover Drab Office Walls in Pixelated Superheroes

805 notes

·

View notes

Quote

We are people first. We are not our jobs.

Great read: http://99u.com/articles/41671/you-are-not-your-job

0 notes

Text

Being wrong is right for creativity

“A man’s errors are his portals of discovery.” – James Joyce.

Too often the fear of failure–of being wrong, of missing the mark, or of embarrassing ourselves–prevents us from uncovering creative ideas. Even when the likelihood of insight is high and the result of discovering that insight could be big for us.

We “play it safe” as a result of fearing a negative outcome from our actions or explorations.

This fear is natural, particularly in cultures like that of America where we’re taught from an early age to cherish “right” answers and avoid anything that might be “wrong.”

But the best creative insights come when we embrace the possibility of failure and view our actions not as something with a right or wrong, but as an experiment.

Work to be wrong, creative author Paul Arden says, and you’re likely to uncover everything those who are too afraid of exploration are missing. In his book, It’s Not How Good You Are, It’s How Good You Want to Be Arden writes:

“Being right is being boring. Your mind is closed. You are not open to new ideas. You are rooted in your own rightness, which is arrogant…So it’s wrong to be right.”

Exactly how can we get past the difficulty of acknowledging that it’s right to be wrong if we want to discover new possibilities?

Over on The Creativity Workshop, Shelley Berc explains that possibly the most ideal method for fueling creativity in moments of doubt is to simply dive-into the creativity and exploration without thinking much about what it is you’re diving into:

“The creating comes first and the analyzing later. That leaves the creator in a place of uncertainty, an exhilarating position for a creator, but a situation our inner critic can’t stand—a good reason for her to stay out of our way at this point in the creative process. Creativity thrives on uncertainty. If we always knew the outcome of our creative endeavors we would probably be too bored to complete them.”

The next time you find yourself pausing before taking on an endeavor where new discoveries would benefit you, remind yourself that being right is boring and dive-in anyway.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creativity is not a symptom, it's a system

To be creative is not the same as creating a painting, writing a book, or performing on Broadway, and it’s well past time we stopped treating it as such. To be creative is to create change in the world around you.

The famous Kelley brothers (founders of IDEO) said that last line, and I think it’s worth reiterating: Creativity means creating change in the world around you.

It’s with this phrase that we can see creativity as a system of thinking. Not a symptom of artistic ability or other-worldly genius.

Your brain itself is a system, a set of complex moving parts that together form a larger whole. Your entire body is a system, as is your social circle, your school or job, your city, and so on.

These systems work by having each individual part making movements toward a wider whole.

Today there are ample arguments that state creativity is little more than a buzz word, that it’s no different from “ordinary thinking,” or that it is an act reserved for only a select few of artists or geniuses born with the ability.

I’d like to argue against those points and help clarify what creativity actually is, based on my decade-long endeavor to research and write about it.

Creativity is a system of thinking that has been recorded for thousands of years. It’s not merely ordinary thinking, it’s beyond that (otherwise we would view every surprisingly novel idea or solution as “just another idea”). Creativity is also something anyone can experience, not only a small group of talented individuals, because it’s something that can be learned and trained as we’ve seen in both research studies and real-world examples scattered across the web, in movies, and in books.

To treat creativity for what it is–a system of thinking–is to see it as something we can not only learn and teach, but something we can manipulate and increase as necessary.

If creativity is a system, what are the elements that make it up? Creativity entails many different areas that contribute to our overall ability to generate new and worthwhile ideas and to solve problems. The system itself is comprised of mental modals, but there are some areas outside of the mental system that affect it as well. To name a few of the components that play a part in creative thinking: our experiences and our ability to recall them, our empathetic intelligence, our physical energy, our curiosity, our ability to endure, our imagination, our levels of stress, and many other components.

To utilize the creative process of thinking we merely must rely on these components together. We should have many diverse experiences and inspirations to pull from, we should learn to meditate or otherwise guide our thinking, we must pay attention to when biases or assumptions are standing in our way, and so on.

To think creatively is to utilize these methods of thinking and observing in proactive ways.

Neuroscientist Paul King explains:

“…The brain adapts according to use. So if the brain is used extensively in a certain way…then it will get better at that. So what you are exposed to and what your brain spends its time doing really does shape who you become and what mental skills you (and your brain) have.”

Those we view as being “more creative” than us simply have used the necessary parts of the creative system more often than we may have. They aren’t necessarily more intelligent or even fortunate, they’ve simply trained their brain to think creatively. They have surrounded themselves with inspiration, they have developed a keen eye for unique information, they continue to press forward even after amounting failures, and they hold tightly to a curious mentality through their work.

In her book, Mastermind, Harvard psychologist Maria Konnikova elegantly echoes the point:

“Insight may seem to come from nowhere, but really, it comes from somewhere quite specific: from the attic and the processing that has been taking place while you’ve been busy doing other things.”

The creatively trained mind is one that works in a way it has been trained to: by imagining solutions to problems, by being acutely aware, and playfully dreaming of possibilities whenever possible.

Often we find ourselves struggling to think creatively due to one or more “blocks” in our thinking that prevent the creative system from being fulfilled. That’s the downside of creativity as a system: if one part of the system isn’t working, the whole system struggles. You can have all of the experiences in the world, but unless you are capable of ruminating on them and diligently working on a problem, you’re not likely to come up with any way to change your world.

In these instances it makes sense why working in a group or stepping away from the work can help us re-spark the system. Things like going for a walk or a long drive, or calling up a friend, can help fill in the creative gaps of your mental system.

For example, over on Harvard Business Review, creative author David Burkus explains the value of stepping away:

“When you work on a problem continuously, you can become fixated on previous solutions….Taking a break from the problem and focusing on something else entirely gives the mind some time to release its fixation on the same solutions and let the old pathways fade from memory. Then, when you return to the original problem, your mind is more open to new possibilities – eureka moments.”

And in my article What a group can do for creativity I explained:

“Working in a group, for example, means you not only have your experiences to build up your creativity, you also have the experiences of everyone else in the group too. If creativity is just connecting ideas from past experiences (which a part of it is), then working in a group is undoubtedly helpful.”

The point of all this is simply that creativity is not an end-result, or a symptom. Creativity is a system of thinking in order to create change in your world.

Your world can be as small as your personal life or as big as the physical world itself. The context doesn’t matter.

What matters is grasping the concept of creativity being a system of thinking that all of us can utilize, strengthen, and share, as needed.

When you think about creativity is a system–involving many different components that affect how you think–how does that affect the type of creative work you’re doing now or want to be doing?

If you find yourself creatively stuck, evaluating where your thinking system is getting stuck is a good place to go in order to get unstuck.

Photo via Flickr.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

The enemy of all bad ideas: someone to talk to

When it comes to ideas, quantity impacts quality: the more ideas you have, the more likely you are to have a good idea.

However, if you are going to avoid the trap of thinking that some of your bad ideas are actually good (which is a trap we all fall into from time-to-time), you need to have someone you can rely on for honest feedback.

We all have bad ideas. Einstein thought the universe was static. It may be worthwhile to try and have less bad ideas, but it’s futile to try and constantly have only good ones.

The reasons for bad ideas are often complex: we don’t fully understand the context of what our idea entails, we misunderstand it, we’re too optimistic about aspects of it, or we’re thinking too short-term or long-term about it.

One of those points creates a huge problem for even the most successful and intelligent among us: sometimes we don’t know when a bad idea is bad (and that’s bad). By fighting for a bad idea, or working diligently on an idea that is doomed from the start, we waste time, energy, and even a little piece of ourselves—in the form of ego.

To combat this common shortfall of identifying bad ideas, we need to get used to sharing our ideas early and often, at least to one other person we can rely on to give us open and honest feedback.

Author Scott Berkun details how explaining the reasoning behind an idea to someone else can help us identify holes in our thinking or reasons why the idea might be bad:

“Your best defense starts by breaking an argument down into pieces. When [you] say ‘It’s obvious…’ [They] say, ‘Hold on. You’re way ahead of me. For me to follow I need to break this down into pieces.’ And without waiting for permission, [they] should go ahead and do so.”

Because the idea will be broken down into explorable chunks by the other person during discussion, it’s much more likely that logical problems or other issues with the idea will float to the surface.

Of course, this approach goes both ways: when someone approaches you with an idea, pause and take a moment to evaluate the reasoning behind it—breaking it down into smaller chunks you can easily understand, as necessary—in order to determine whether or not it’s really a good idea.

To better manage your bad ideas, find at least one reliable person you can count on to give you honest feedback on them and push you to develop them further when necessary or drop them when appropriate.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

You don't need a toolkit to think creatively, just the right conditions

Creativity thrives under certain conditions, while it is debilitated under others.

Knowing what those conditions are and how they influence us can help us to think more creatively, even if our intent isn’t to do so.

Unfortunately we often get stuck on attempting to circumvent the circumstances that promote creativity. We want a quick way to generate the perfect idea or to uncover the best solution to a problem without having to put in the work necessary to formulate the right types of ideas.

The result of this approach to thinking creatively? We pay for books and “programs” we don’t need. A self-help book or a “creative toolkit” isn’t likely to make you think more creatively unless it promotes that form of thinking itself. Most of these types of resources are instead focused on the act of creative expression, not the creative process itself. I think this partially explains why so many books on the topic of creative thinking are full of little but hot air.

In a recent blog post, Author Matthew E. May introduces us to the keys to creative conditions by stating:

“Want real creativity? Stop paying for ideas, in any form. Think about removing the obstacles you’ve put in the way of innovative thinking up and down the line. And stop coddling people with smile training and personality-based kid gloves.”

What May means here is that we don’t need to buy a fancy toolkit or subscribe to a certain system in order to think creatively. Those things rarely helps us because they don’t have any influence on the conditions required to think creatively. Instead, we should pursue ways to introduce the proper conditions for creative thinking, removing anything that stands in our way of meeting those conditions if possible.

I’ve written about the ideal conditions for creativity before:

“The most ideal condition is one in which we are mentally stimulated with a task, but at the same time free to explore possibilities unhindered.”

May echoes this statement in his own words by explaining how toolkits for creativity typically fall flat of being able to provide the wider conditions we need to think creatively.

I want to empahsize this point, the reason toolkits and how-to-guides struggle to help us be more creative is simple: the only way to build an environment where creativity can thrive is to change the system or environment itself, not to introduce a new tool or mentality into the mix. Whether that means physically moving yourself, or changing how you work, you have to ensure you have the right conditions for creativity to bubble-up in order for it to do so. May writes:

“Mostly, you’ll need to focus on undoing what you now do, not doing more. You’ll need to break the current habit, and a starter kit won’t do that.”

To summarize May’s keys to creativity:

We must have clear and dramatic goals. Attempting to think creatively without a clear problem or goal in mind is like attempting to put a puzzle together without having any idea of what the final picture will look like.

Establish a clear role as you move forward. Are you going to play the part of an artist or an innovator? Knowing your role can help you set the right mentality for tackling the problem or task at hand.

Ensure you have total freedom to tinker and innovate as needed. If you can’t test ideas out, your creativity will be stifled. You need to have boundless freedom to explore ideas as necessary.

That’s it. As long as the conditions for creativity are met–through May’s three keys” we will find ourselves readily stumbling on new and worthwhile ideas.

You don’t need a self-help guide to thinking creative. You also don’t need the perfect tool (or even a toolkit) to discover your creative potential.

All you need is a goal, the belief that you can be creative, and the freedom to be so. Some tools and books exist to help you do just that, but most are too focused on the outcome and less about the conditions.

Which of the three keys are missing from your life today? What one thing could you change to get all three keys into your life? What’s stopping you from doing that one thing right now?

Photo by Matilde Zacchigna.

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lovely idea from Peter Rossetti, one of the participants in the workshop after my talk at The Design Gym in NYC last week: collect ‘best wishes’ notes from colleagues for a parting employee - instead of the often so soulless and cold boilerplate going-away emails.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Scratch your own itch." — Jason Fried. Watch the video at http://creativemornings.com/talks/jason-fried/1

42 notes

·

View notes

Link

In Whatever You Think, Think The Opposite Paul Arden tells us why we so often struggle to think creatively:

“[You feel] trapped. It’s not because you are making the wrong decisions, it’s because you are making the right ones. We try to make sensible decisions based on the facts in front of...

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Your work is a gift. Get your copy here: James Victore for Holstee

69 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The happiest people are those who think the most interesting thoughts. Those who decide to use leisure as a means of mental development, who love good music, good books, good pictures, good company, good conversation, are the happiest people in the world. And they are not only happy in themselves, they are the cause of happiness in others.

William Lyon Phelps (thinkexist.com)

78 notes

·

View notes