I answer questions to help you create accurate depictions of horses, riding, and horse-adjacent subjects in your stories.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

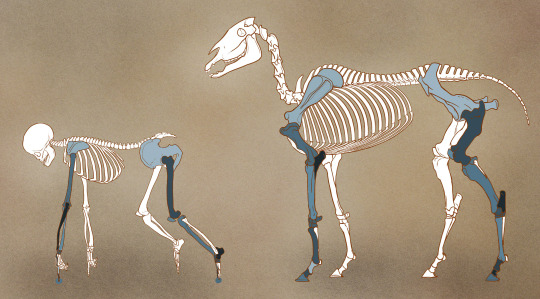

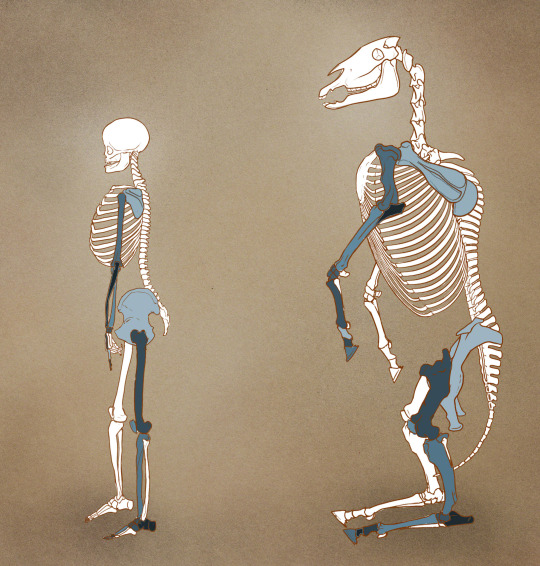

comparative anatomy

actual, useful reference under the cut

Keep reading

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Ever since I've put on weight I've been told I can't ride because I'd "break the horses back." I'd never want to harm a horse, but is this true? I've been slowly losing weight, but it doesn't seem to be enough. I know skinny is ideal, but can bigger people ride? I'd love to get back on a horse again (while still working towards my weightloss goals.) (I'm around 270lbs)

First of all, a hug for you ❤️ and a face punch to whoever told you that. 🤜😑

Not all horses are suitable for every size of rider, but there are horses that can carry you comfortably. I hope that if you are willing to explore different programs you will find a lesson situation. I truly believe that people who want to love and be around horses deserve to love and be around them.

1 note

·

View note

Note

While searching for horse breeds my character can use to ride a long distance (most of the story's world, if the world building keeps growing) and I came across this. "While not technically a horse, Mules aren’t Donkey’s either. They are the result of a male donkey (a Jack) crossed with a female horse (a mare)." Cue AOL dial up noises as my brain tries to cope with this information. MARES AREN'T DONKEYS?? HOW?? WHY?? but.. but... they look like donkeys?? HELP IS THIS REALLY TRUE???

Google would never lie to you!

0 notes

Text

I know I’ve been quiet a while but I just bought a book with horses in it so hold tight, I’ll be back soon.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: riding arenas aren’t raked by hand.

I think some information about arenas might come in handy for you, so here’s an overview:

Many facilities where horses are kept for riding or working purposes have arenas, which is a term for an area that is used for riding which generally has a sandy soil footing (though there are all kinds of surfaces of varying levels of sophistication, this is the most common one) and often has a fence, but not always. The term “arena” is not interchangeable with “corral” or “paddock”; these are usually terms for pens where horses are housed, and an arena is where they’re ridden/exercised.

Arenas are usually oval or rectangular, and they’re large. Even on the small side they’re likely at least forty feet wide. Most arenas are outdoor. Some are covered with just tall supports and a roof, so that the surface doesn’t get muddy or snow-covered, and to provide shade in hot seasons. Some are indoor, and are fully enclosed. Some premiere indoor facilities have heat, and some are even air-conditioned. (The famous Spanish Riding School indoor arena even has chandeliers!)

Even an outdoor arena is an elaborate installation. First, the area has to be leveled with heavy equipment. Then, a base may need to be constructed, depending on the conditions. A good base is solid and porous; gravel screenings or composite material are common opinions and several inches of depth may be necessary. Finally, over the base the footing is applied. Even a simple sand arena on the smaller side will require hundreds of tons of footing. Having recently installed my own outdoor arena I can tell you, the process is arduous!

Finally I’ve come full circle. It’s not only inhumane to ask someone to hand rake an arena, it’s not necessary. While there are elaborate arena grooming tools that require a fancy tractor and cost as much as a luxury car, a simple harrow dragged behind an ATV or even a regular pickup truck will do the job better than a hand rake and in a small fraction of the time.

The other aspect of basic arena maintenance in addition to dragging is watering. There are treatments for footing that can eliminate dust, but the majority of facilities still apply water to their arena if it gets dry. Some fancy implements can drag and water at the same time, but at most places, watering is a separate process. Like with drags, watering options can be elaborate or simple. Some places use a dedicated water truck. Some small or home facilities might just have an ATV attachment or tank with a spraying system that can rest in the bed of a pickup. There’s a system for every budget, including mine, wherein I just put my hose and lawn sprinkler out, set a timer, and move it at intervals. ;)

#writing reference#writing tips#writingofriding#writing resources#I read this in a book#arenas#horse facilities#horse care

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Something I see a LOT. A character has never been on a horse before & expresses some nervousness to ride. An experienced rider character helps them up, spouts something instructional, then half a moment later encourages a run. So then the new rider is on a cantering or galloping horse, essentially going 'woooo! so fun!'. Or even sighing like 'ahh so relaxing'. I took riding lessons for a year or two & have never even been on a cantering horse. Am I just missing something or is this unrealistic?

Hi anon! Thanks for the ask. I agree with your instincts on this one... A first-time rider is unlikely to have a good experience at a canter or gallop.

I will say that it’s not impossible! If a person has good natural balance and is hard to scare, they might find their first ride on a horse—at speed—thrilling. But generally speaking, the faster a horse goes, the more finesse is required from the rider to keep the horse under control. A first-time rider might be able to hang on while their running horse follows another ridden horse (which horses are likely to do—when one starts running the other(s) will tend to follow unless their own rider tells them otherwise) without a disaster, but guiding the running horse themselves is not very realistic.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your character probably wouldn’t ride a stallion

Nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: most people don’t ride stallions.

I’m not saying NO ONE rides stallions, I’m just saying that it’s unusual.

Why? Because stallions are strongly driven by an urge to mate, and they’re easily preoccupied by said urge. They’re also more territorial and can be harder to manage around unfamiliar horses. Unless the horse is being kept as a stallion for the purpose of breeding many mares year in and year out, the typical (and frankly, kinder) thing to do is to have him castrated at an early age, which is referred to as “gelding” him. Most male horses are gelded in their first few years of life, and many people prefer to geld them before their developing hormones result in “stud-like” behaviors, before they’re even a year old.

Many people seeking a horse for competition or pleasure work are only interested in geldings, even over mares. Mares have more hormonal fluctuations that can result in more variable moods, and can be more aggressive with other horses, although these are just generalizations. There are plenty of finicky geldings and sunshiny mares out there.

Most competitive associations won’t permit young children to show stallions. Some facilities don’t allow stallions at all. Even on his best behavior, a stallion may be susceptible to the responsive behaviors of other horses--like mares in heat, or another stallion that isn’t being controlled by its handler. For dozens of reasons, most of the horses throughout history that are put to hard work have been geldings and mares.

There are exceptions, sure. One of the best-behaved horses I’ve ever met was a breeding stallion, but his very experienced owner was always alert about his surroundings to keep him, and other horses, safe, especially when they were away from home. But what I find reading fiction is that people assume that their tough character’s tough horse is a stallion, and it always makes me sigh inside. No! It’s probably a gelding or a mare. :)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

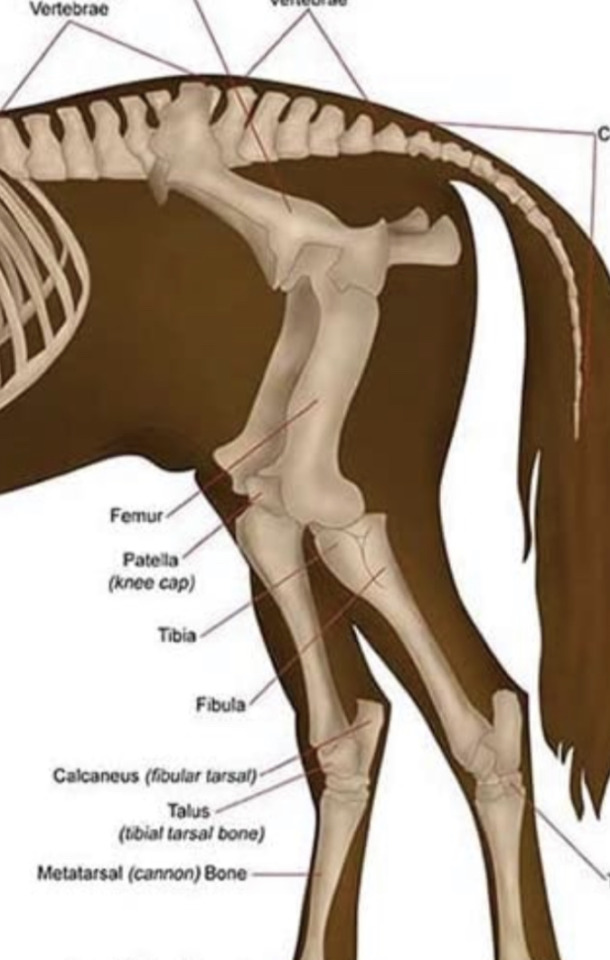

Nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: horses don’t have thighs.

I’m not saying I’ll DNF a book for mentioning someone has put his hand on a horse’s thigh, but I will definitely WTF at a book.

Horses actually do have femur bones, but they are not part of the lower limb that most people picture as the hind leg of a horse. Here’s a picture for reference:

The part of the horse that would be the skeletal equivalent of a human thigh is more commonly called a hip or haunch, or maybe sometimes a flank, depending on the particular spot. The part of the horse that would be the visual equivalent of a human thigh is lower in the hind leg, above the hock (which is NOT a knee) and would probably be described in relationship to the horse’s hock, although the muscle there, called the gaskin, is a point of conformation that most horse people are familiar with, so it’s possible they’d talk about touching the gaskin.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi I'm sorry this isn't like, an actual question. And might not be news to you idk. But I just discovered that "horseling" is an actual word. Horseling!! Next time someone mistakes a foal for a pony, I'm gonna just "Nah that's not a pony at all. But it IS a horseling." I have never wanted to use a word in a fic so badly. I need to write about a horseling right this moment.

Never apologize for being the herald of such important information! Horseling!!!

0 notes

Note

Hi! I'm going around and liking all of your posts because I started Western riding lessons! I love doing research for my fantasy writing, and this kind is REALLY fun. However, a couple of things the instructors told me are prodding my "weird" buttons, considering my thirteen-year-old self has many horse books telling me NOT to do them: They sometimes tell students to give our horse a "kick," or to "yank" the reins if they aren't responding fast enough to cues. Any reason why?

Hello! Thank you for your patience (I think? I mean maybe you’ve actually been super impatient and/or you have forgotten about this ask altogether, lol) while I mulled over an answer to this question and also found the time to give it the complete, detailed answer it deserves. I hope it’s okay that I answered publicly. If not, shoot me a DM and I’ll take it down. I grew up as a western rider, so it’s all too easy for me to imagine the environment that you are in within your lesson program. I was a horse-crazy kid whose parents didn’t know a lot about riding, and my grandpa and aunt took me riding with them from a young age, but just on trails. When I first got into a formal lesson environment with western riders, I was quickly introduced to the theories that are central to a big part of that riding tradition... that if a horse doesn’t listen, you jerk and kick. And if you hesitate, you’re told things like...

He’s not a pet! He’s a lot bigger than you. You can’t hurt him! His friends bite him and kick him harder than a kid ever could, and it doesn’t hurt him. That’s how horses communicate! He needs to respect you!

A part of me sympathizes with people who are teaching riding lessons. Because it’s their business to make people feel like they’re making progress, or their students will quit. Because some of those students would be bored and frustrated if the nuances of riding were explained to them, instead of them having the artificial thrill of getting a horse from point A to point B, which may be the only level of skill that they understand or care to understand. Also, horses in a lesson program do tend to get kind of shut down, so used to filtering out all the small signals from people that they’ve been punished for noticing and rewarded for ignoring, that it seems like they DON’T respond any more to anything but yanked reins and spurs in their sides. I still consider myself a western rider, but with rare exceptions, I would generally encourage friends and family to first experiment with english riding lessons. At some point in most competitive western riding, it became a sin to engage a healthy rein aid; and at some point in most competitive western riding, it became a requirement that you ride entirely with one hand. Now, riding one-handed is not a BAD thing, but it is a very ADVANCED thing, and to place an artificial requirement on beginning riders “because tradition” grates on my nerves. I could go on for a very long time about the chronic illnesses of most competitive western riding sports. And I should say that there are myriad problems in other disciplines, too, but some of what’s at the root of the problem with most western competitions also manifests in what I consider bad instruction of even beginning riders, which is why I said you might be better served by an english riding program. What I want to tell you foremost is that you should listen to your gut. Every time I hear someone tell a child to toughen up, to ignore their emotions, I feel sick to my stomach. Why do we do that to adults? If you’re being asked to do something that makes you feel fundamentally uncomfortable, that takes away the joy and harmony that you were seeking when you went to this person to learn about horses, then reconsider who you’re learning from. I know that’s very hard to hear, and your instructors are likely people who mean well, and love horses... but they were once taught the same things that they’re trying to teach you right now. And eventually that inner voice inside them that protested, just like yours is doing now, went quiet. My advice is that you don’t let that happen to you. <3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: it takes a long time to fully train a horse.

In fiction, written and on-screen, I often see depictions of a horse that’s wild or at least unstarted one day, then it’s the best horse on the ranch/cavalry/space ship the next.

Just—no.

Even when a gifted horse trainer and a willing horse are involved, the process of teaching a horse to be a reliable mount in a variety of conditions and environments takes many months, and that’s assuming the training sessions are frequent and intensive. I’ve heard professional horse trainers say that it takes about two years of full-time training to “finish” a horse in some disciplines, and in others, the expectation that the horse would be a top performer doesn’t come until the horse has been under saddle and ridden regularly for several years.

If your story needs a horse transformation, you could make it a trained horse with dangerous habits—maybe she’s thrown everyone who’s tried to ride her for a year, or maybe he’s anxious and bolts. Horses with these kinds of “vices” sometimes blossom relatively quickly with an empathetic, experienced rider who knows how to restore their trust and confidence.

#writingofriding#writing resources#writing tips#writing advice#no one asked#riding#training#horse behavior

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: you should look your gift horse in the mouth.

You can estimate the age of a horse by looking at its teeth. Horses have what are called deciduous teeth, which means they are constantly growing, and are ground down constantly by a horse’s chewing. The angle, shape, and growth rings on certain teeth change as the horse ages.

So, looking at a horse’s teeth can be a way to tell if you’re being sold a twenty-year-old horse advertised as a ten-year-old, for example.

But if you got the horse as a gift, you shouldn’t care how old it is. Thus, an idiom was born.

Except actually taking care of an older horse is a big responsibility! So the responsible person would totally want to check out that gift horse’s teeth.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: because Reasons, most* people lead horses and mount them exclusively from the left side.

In countries with a strong European influence on their riding tradition, horses are taught to lead and stand to be mounted primarily, if not exclusively, from the left side.

This practice dates back to when gentlemen and soldiers, who were mostly right-handed, wore swords on their left hip, which made it easier to swing over their right leg as they mounted, rather than their left. For no reason I can figure out, it’s a tradition that stuck, so much so that the majority of horses and riders I encounter still follow it.

I’d love to hear if this varies in other parts of the world, as it seems as though it would!

Certainly there are people who make an effort to familiarize the horse with being led and mounted on each side, but most people seem to keep to the left, sometimes called “the near side,” without ever thinking of why. Their horses might be totally comfortable being led and mounted from the left but might completely fail to tolerate the same thing from the right, and at best would be uneasy.

#writing reference#writing tips#writing resources#writingofriding#horseback riding#left side#near side

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: a pony is not a baby horse

Seriously. "Pony” is used to refer to certain breeds of horse that are generally smaller in size. There’s no hard and fast rule for what constitutes a pony between different breeds, regions of the world, or even different riding traditions. A baby horse OR pony is called a foal. Female foals are sometimes called fillies. Male foals are sometimes called colts. Young horses are often referred to as “filly” or “colt” (but not foal) until they’re a few years old.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

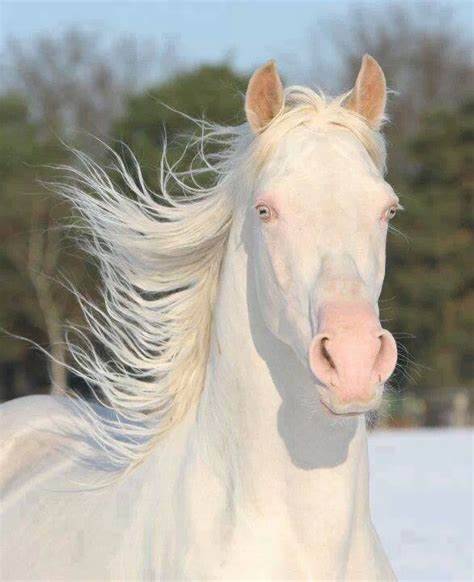

nobody asked me, but I’m telling you anyway: there IS such thing as a white horse

Person: “And then the prince rode up on his white horse and--” People with just enough knowledge to be obnoxious (and also the nerve to interrupt): “--there’s no such thing as a white horse!” Actually, there are white horses. Especially if you’re writing a fantasy story where people can call coat colors whatever you want them to. In the Real World, what would technically be considered a white horse IS rare. The definition is that the horse has unpigmented (pink) skin over its entire body, and white hair. That genetic combination is unusual, but these horses exist. Sometimes they have dark eyes, and sometimes their eyes are blue. The genetics of these horses are usually “dominant white” or “sabino white,” but there isn’t a visual difference between the two types. (Pictured below: a rare “dominant white” horse that happens to be a Thoroughbred.)

The obnoxious person was probably about to say that horses that look white are actually grey or gray. And sometimes, that’s true. In the Real World, gray refers to a horse with a gray gene, which is fairly common in most breeds. Gray horses are generally born a darker color, but “whiten” as they age. Their skin is pigmented. Some of them turn completely white when they’re still very young, and some never completely whiten. But most commonly a horse with a gray gene will be totally white by its middle age. One acute difference between most gray horses and most white horses is the appearance of the horse’s head, especially around the eyes and muzzle, with pigmented versus unpigmented skin. (Pictured below, a mature gray stallion.)

But grays aren’t the only horses that can appear white or mostly white. Appaloosa, paint or pinto markings in certain breeds sometimes result in horses that appear white. A famous example is the “medicine hat” tobiano, which is born with white markings over so much of its body, that many lay people would describe them as white.

(Pictured below, a medicine hat tobiano stallion. The skin around his nostrils, mouth and eyes is pigmented.)

Another example of horses with unpigmented skin that can appear white but aren’t, are the double-dilutes, which are the result of horses that carry two copies of the gene that dilutes other coat colors. When two single-dilute horses mate, they have a 25% chance of creating a double-dilute offspring. An example of a horse with one dilute gene, specifically the creme gene, is a palomino (chestnut + one dilute gene) or buckskin (bay + one dilute gene). A horse with two creme genes is called a cremello, and can range in color from light gold to creamy white. Cremellos have blue eyes or sometimes amber eyes. (Pictured below, a very light-colored cremello stallion. Note the unpigmented skin on his face and how it affects his appearance.)

One thing to note about unpigmented skin is that horses can sunburn in these areas, and are more susceptible to skin conditions including cancerous conditions. If I’m reading a book and horse-savvy, contemporary characters describe a horse as “white,” I might roll my eyes, but there ARE white horses out there. If you really want to include one, you can have the character acknowledge that their color is rare. But for a “white horse” aesthetic without the complications, it’s true that gray is probably a safer bet. You can use additional description to make it clear that the gray horse in fact has a pure “white” coat, like the example above.

#writingofriding#writing resources#writing reference#Writing tips#horse coat colors#white horses exist#end white horse erasure

46 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the dumbest description of a horse you’ve ever read in a published novel?

One I’ve read isn’t coming to mind, but I’m constantly running into illustrations where the hind legs bend the wrong way. 😂

Thank you for the opportunity for a non sequitur into cover illustrations. Please don’t assume your artist knows how horses’ bodies work! Ask your friendly local horse person to have a look at it. You probably know one of us, even if you don’t realize it. We’re everywhere.

2 notes

·

View notes