Text

An Interactive Element

For the last several weeks, I’ve been iterating upon and fleshing out the general concept of an AI capable of generating audio. Initially, the goal was to create machine-made music in the style of existing human recordings; recently, the aim has shifted more towards an examination of how a computer comes to understand any given soundscape when asked to create its own.

The working prototype for the project is featured here, fully capable of providing 4 concurrent sources of sound with variable volume levels, executable within the browser:

https://editor.p5js.org/tobij622/present/yGOn6HJez

To use the applet, toggle between the level of coherence for any soundscape, toggle the sound on with the small checkbox next to the coherence selector, and adjust the volume to your liking.

Before delving into how this prototype works and addressing where it excels/falls flat, I’ll walk through my design process and provide resources used to inform the prototypes general creation and form. In the moments immediately following last class, I plunged deep into a pit of despair and panic knowing fully well I would be unable to collect a meaningful dataset and train an AI in under two weeks. Nonetheless, I set out to do exactly that, contacting my two best resources for direction on where to start. One of them reassured me I was right to believe creating an AI in such a timespan was impossible, and the other pointed me in the direction of WaveNet, Google’s proprietary text-to-speech generator trained via raw waveforms. WaveNet’s general documentation, in all of its horrifically dense glory, can be found here.

I spent several days reading up on WaveNet, its required processing power, and a number of alternatives capable of producing similar results with less training time. I stumbled across what should’ve been my holy grail, a full Python-based iteration of WaveNet made entirely free out of a passion project, but nonetheless struggled for several days with implementing the system on my 2015 Macbook Pro. In the interest of time and actually having something to show for, I elected to approximate AI-generated sound on my own.

While doing research into AI-generated soundscapes, I found a thoroughly-documented Medium page deep within the well of Google’s boundless knowledge that provided incredible examples of simulated speech and music built on the same free iteration of WaveNet I intended to use. Some examples of generated sound from the article follow:

A generated piano.

What can only be described as “a Christmas-themed death song.”

A fake forest with a genuinely convincing AI-creek.

Ambient clicking.

and an AI’s understanding of “Happy” music.

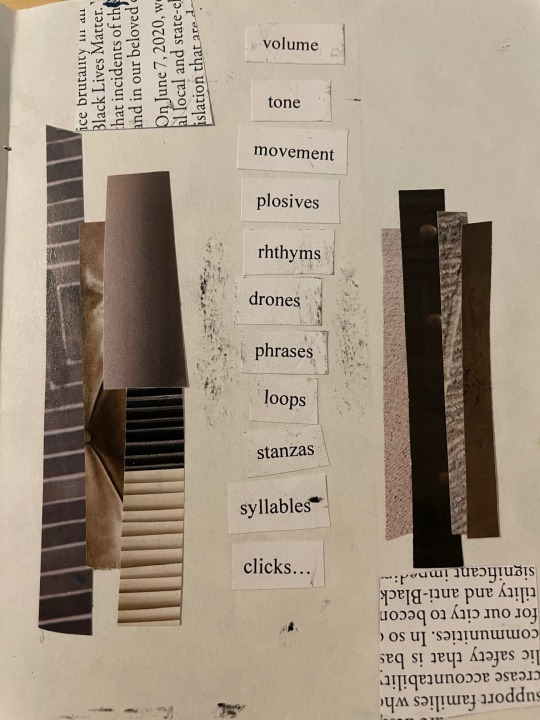

The article proved indispensable and was the basis upon which I built all of the audio samples used in my functioning prototype. Among the more striking features of all pieces of AI-generated sound provided by the article is the pointillism present throughout the recordings best represented in low clicks, subtle plosives, and almost speech-like rapidity in nonsensical musical phrases. These recordings immediately brought to mind the practice of granular synthesis, a form of sound design that takes audio samples, typically at least under a second long, and uses them to build clouds of sound. Just for reference, here’s a link to Iannis Xenakis’ Concret PH, the piece Xenakis himself righteously claimed invented the notion of granular synthesis.

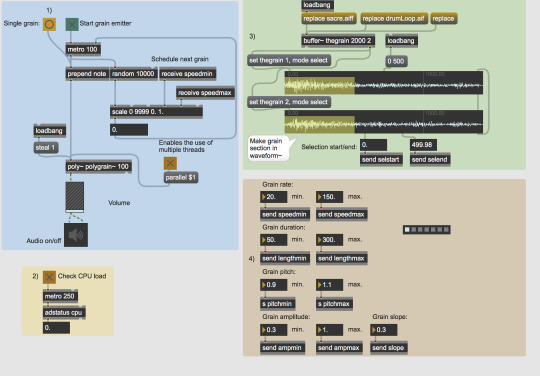

Running with this idea, I made some rudimentary edits to Max/MSP’s demo granular synthesizer and rigged it to have audio recording capability, shifting a few parameters around to provide a level of control for the synth’s given output. A feature I found to come up often in the articles and documentation concerning AI-sound is the variance in coherence of any given output file, with more coherence owing to more of a reliance on an existing dataset rather than pure synthesis of new material. For this reason, I elected to use four existing sound files and create, for each of them, two different levels of coherence akin to real AI sound parameters. The four sounds I used I largely sourced from findings on the internet: the bird sound is of an existing Mockingbird recording, the forest sound is of a rain forest, the vox sound is of a well-loved interview between Levar Burton and Rickie Lee Jones, and the cityscape was my own recording of 5th Avenue right next to the main Parsons building.

For each of the four recordings, I tailored my granular synth to produce vaguely coherent and entirely incoherent iterations upon the original provided sound. The results vary and, unlike actual AI-generated sound, all share the same audio fidelity and snippets of data inherent to their original sound file.

The online prototype itself is the product of three days of tinkering in p5.js and was the result of what seemed to be an endless headache regarding p5′s innate sound library. The end product seeks to emulate what a real application capable of generating AI-sounds would look like and how it would handle, serving both as a sample serving of generative sound and a small-scale audio mixer with the bonus ability of constructing hybrid sonic realities. The small modulating Bezier curve present in the background is exclusively to provide visual stimuli.

0 notes

Text

Physical Object

I’d be lying if I said I had a cohesive plan throughout this assignment. The idea of creating a physical object of any sort for an entirely digital project seemed borderline impossible at best and entirely futile at worst. Luckily, my girlfriend happens to be a spectacular DIY artist and walked me through how I’d implement my idea in a zine. I’m the luckiest boyfriend alive on truly all fronts.

To preface, I have no experience with zines, collage, or using oil pastels, all of which are the entirety of my physical object. Moreover, I have essential hand tremors and had to use a very sharp, very precise Exacto knife to get the cuts I sought, so my edges are, put kindly, rough.

I began documenting the project the moment I came home with the necesarry supplies to start it. The original intention for the project was to use an old color printer to print out images fit for inclusion into the zine; I forgot that the printer was about $50 and printed out color images of roughly the same low quality. This radically changed the design parameters and I found myself in another 7-in-7-esque project, using only found materials the attempt to convey an extraordinarily complex topic.

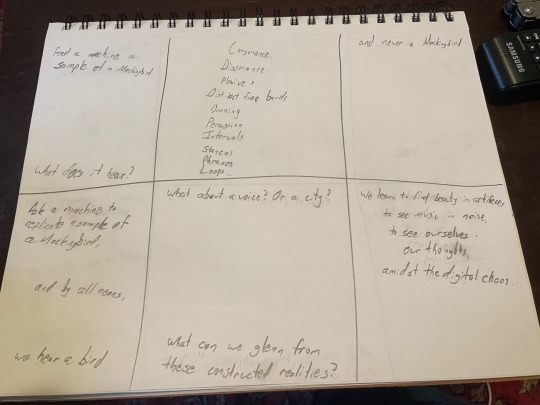

Before mustering the strength to dig through the old Bon Apitite magazines and political pamphlets that made up my entire collage canvas, I wrote the prose that I structured the zine’s flow around. The task at hand was to narrate how I came upon the idea of using an AI to generate audio, emphasizing computational understanding of things like “nature” and “sound” and how these relate to people semantically. The final text is as follows:

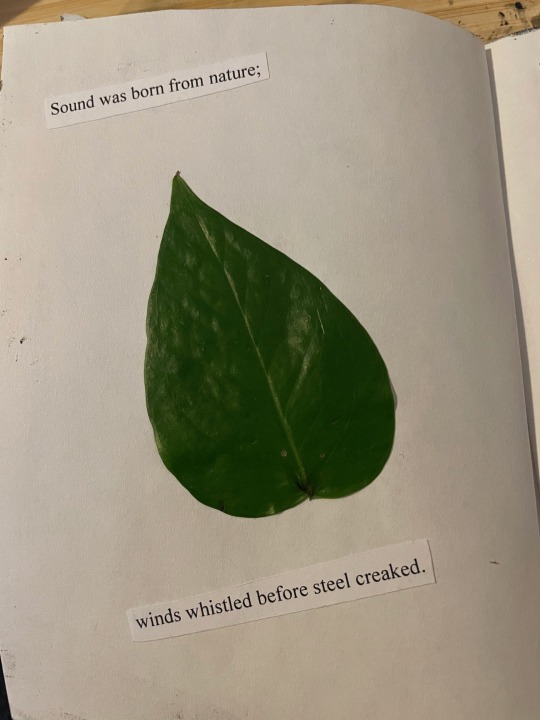

Sound was born from nature;

winds whistled before steel creaked.

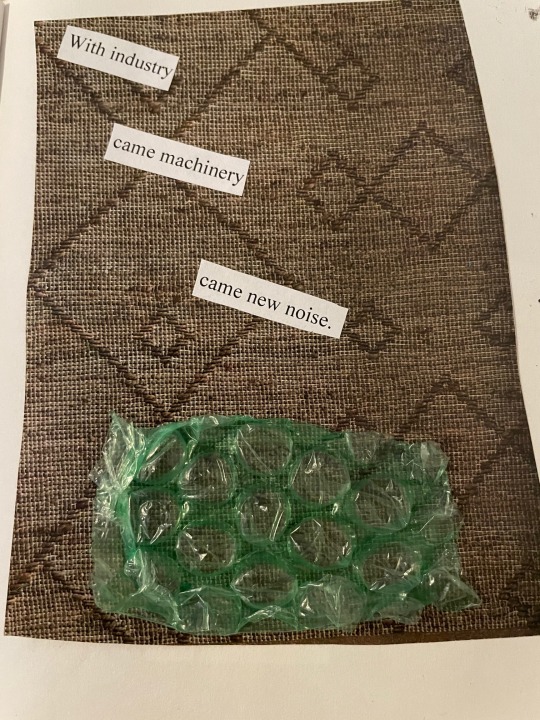

With industry came machinery came new noise.

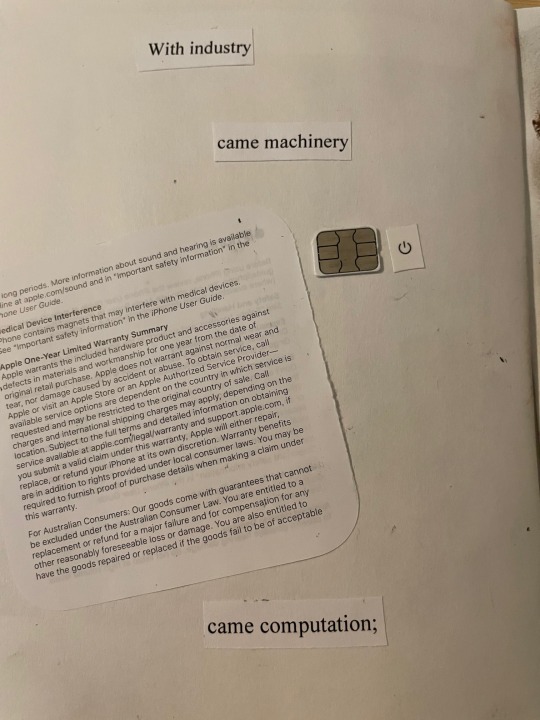

With industry came machinery came computation;

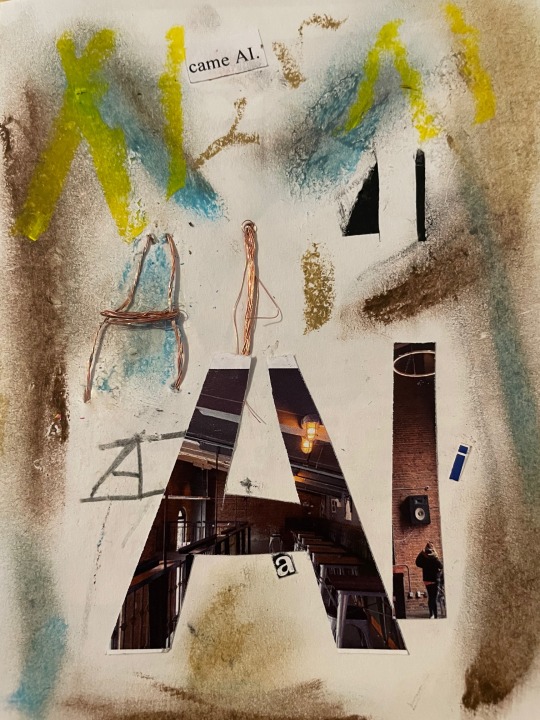

came AI.

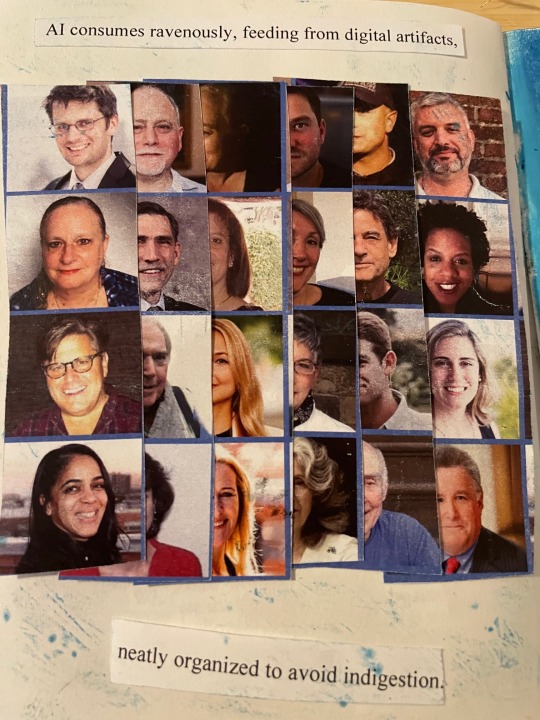

AI consumes ravenously, feeding from digital artifacts,

neatly organized to avoid indigestion.

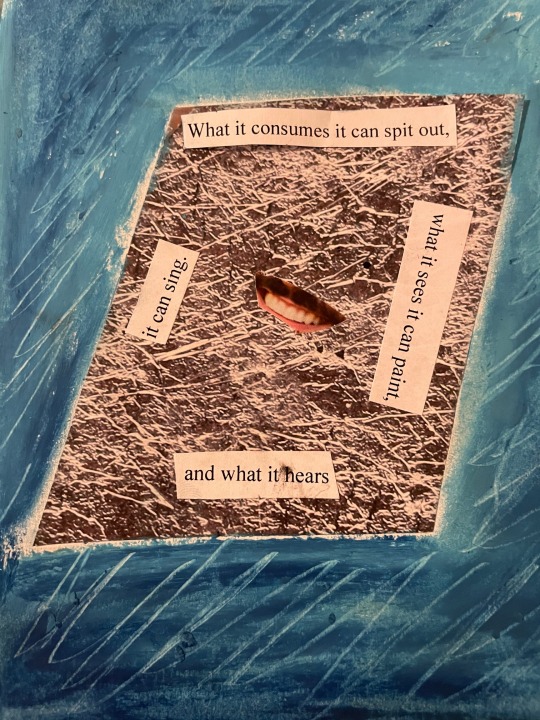

What it consumes it can spit out,

what it sees it can paint,

and what it hears

it can sing.

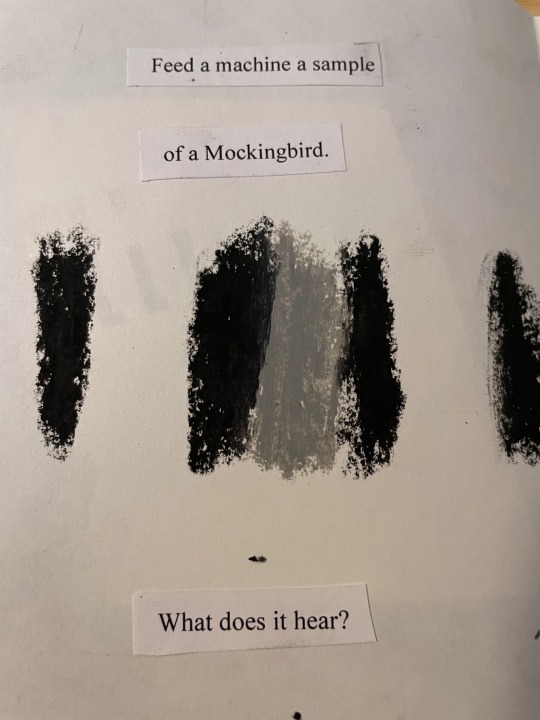

Feed a machine a sample

of a Mockingbird.

What does it hear?

volume

tone

movement

plosives

rhthyms

drones

phrases

loops

stanzas

syllables

clicks…

but never a Mockingbird.

Ask a machine to recreate a sample

of a Mockingbird,

and by all means,

we hear a bird.

What about a voice? A forest? An entire city?

What can we glean from these constructed environments?

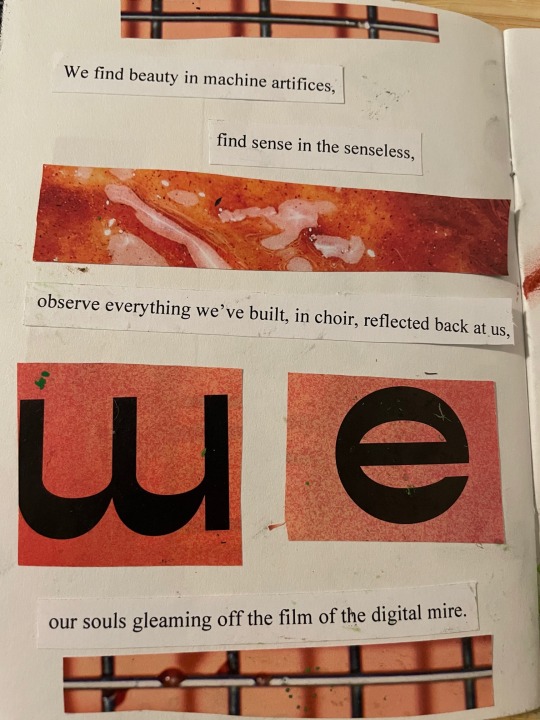

We find beauty in machine artifices,

find sense in the senseless,

observe everything we’ve built, in choir, reflected back at us,

our souls gleaming off the film of the digital mire.

When writing this, I was almost certain I would be able to dig up an image of a Mockingbird somewhere among my dozen of birding books. Deciding I held those books too close to my heart to mutilate them in good faith, I turned to abstraction (for better or for worse).

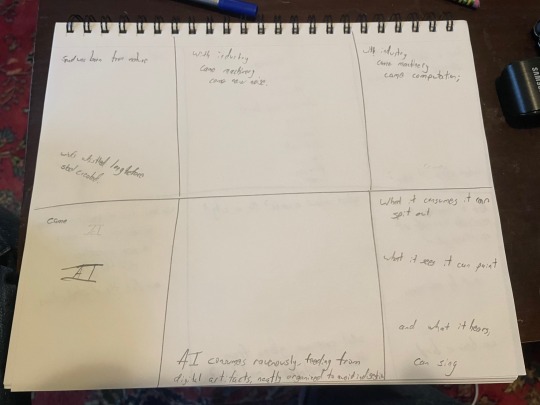

The prose was loosely based off the following storyboard I wrote at roughly the same time. The final prose differed a bit from the placeholder text I used mostly for visualization purposes, but the message is more-or-less the same:

After some proofreading and a bit of cutting to build a little pamphlet out of sketchbook paper, I printed the prose and set out on cutting out each line to best fit the meter I hoped for:

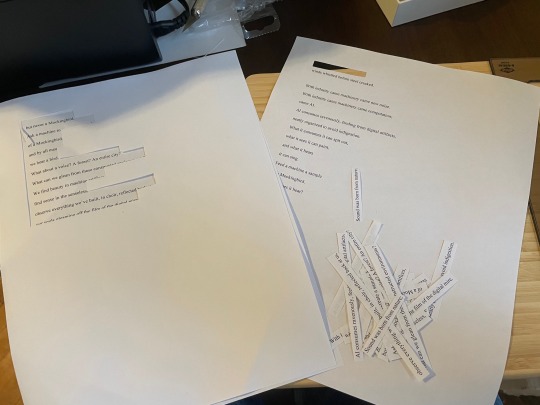

I then put together all the found materials I could muster, from collected magazine scraps to bubble wrap, copper wire, and an old SIM card. I just recently got a new phone after using the same one for 7 years, so some materials are likewise from the new iPhone’s packaging. Of note here is my abstraction of a Mockingbird, using its general wing color and notable white wing bars to make up for the fact that I can’t draw:

After 6 hours of cutting, ripping, meticulous pasting, weaving, taping, ruining, fixing, and ultimately covering my hands in oil pastels, I had the final product and some additional handiwork from my saving grace of a girlfriend to show for. Here are pictures of all pages of the zine, front to back:

As can be clearly seen, my aesthetic’s hand was forced by the natural bleed of pastels, so I elected to commit to oil bleed in the finished product. I use found materials throughout the zine to highlight the nature of datasets, compiled of odds and ends spanning the gambit of tangibility, living and dead. I use a live Pothos leaf collected from a particularly healthy plant of mine for use on the first page, the best possible inclusion of nature I could find that would simultaneously provide an organic texture. Throughout the zine, I use found objects that literally produce sound (like bubble wrap) and weave with copper wire to contrast nature with the man-made, complimented by contrived shreds of old magazines used for their textural value and sparse pops of color. I carry the allegory of the Mockingbird throughout the zine until its last page, featuring a pastel illustration done lovingly by my girlfriend. The Mockingbird holds a special place in the kingdom of birds in its ability to learn and replicate, not unlike machine learning, through exposure and iteration.

I enjoyed executing this project far more than I anticipated, and I feel it does a much better job conveying my curiosity towards AI-generated soundscapes than something like a graphic poster or academic paper could. Though I have a massive mess I still need to clean up, I managed to find a new niche to delve into with collage while, in my opinion, creating the most thorough amalgam of natural and artificial I could.

0 notes

Text

Developing an Idea

- What makes this project special?

- It’s technological anti-art – think Dada but with HAL. Machine learning is ubiquitous in daily life, with its ease-of-use contested only by its ethical flexibility. Machine learning (often shortened to ML) has recently made its break into non-experimental art in dozens if not hundreds of subtle applications, the most personally prominent example being the Izotope Ozone sweet of ML-trained mixing and mastering plugins. Once a several dozen thousand-dollar ordeal, ML made mastering feasible for bedroom musicians – it is, however, still astronomically expensive. Here, I’m using ML to work backwards from the subjective, electing to give AI a musical voice rather than reign it in for human use or consumption. In essence, my project will be building an alien pop-star.

- What hardships do you expect?

- I have to leap over the spectacularly high hurdle of teaching myself how to use ML in a musical application. To do so, I’ll not only have to build my own program from scratch in Python, but also create and annotate datasets myself to get an end product I feel comfortable calling mine. The ML algorithm may full-well develop music that either directly harms hearing or is beyond the bounds of human hearing; since I’m reluctant to exert control over the AI’s voice, I’m still deciding how best to handle this situation when it almost inevitably occurs.

- Who will use it?

- Foremost, me. Additionally (or perhaps adjacently), anyone I know or anyone who reaches out to me to take the algorithm and feed it their own little datasets, or those who stumble upon the project and manage to make something more creative and palatable than I ever could.

- How will it be used?

- Assuming all goes well, it’ll take the form of a healthy chunk of executable code. Interaction will be limited to feeding the algorithm data and asking it for an output. Everything else the algorithm handles itself, much like an actual performer provided with a score of sheet music.

The Story

I spent the final year of undergrad trying to turn trash into music. The concept seemed simple enough: take an object detector, point it at a mound of plastic or metal garbage, and get a song. In reality it was a test of faith in myself as I dug through dozens of Machine Learning theory books and steadily lost faith in my reading comprehension. The final product was a sonification of John Conway’s game of life (with my first ever animated visuals!) with a pre-determined set of notes, chords, and progressions to choose from. While the end product sounded nice enough, it fell far short of my greater intentions for an AI songwriter.

This project takes a more direct approach: rather than use an intermediate factor to create a piece of work with a greater cultural context, my goal is to get a Machine Learning algorithm to make noise. I’ve created and annotated my own datasets before and spent at least 200 hours trying to make sense of ML in Python, so I’m again setting out to find a foothold trying to reconcile AI with “art.”

Four years of education pursuing a degree in generative music and tech-centric sound hammers in a notion that tech is a beast of burden built to be wrangled. Within the same degree program, all projects were massive departures from music theory going back thousands of years, emphasizing things like the semantics and sonic properties of sound itself rather than adherence to classical music formulas. With this AI project, I’ve found I’ve come to an impasse as an artist: should I make pretty music with elements of AI. or should I attempt to give AI a voice regardless of how it might turn out?

Against the wishes of my ears, I’m electing to pursue the latter.

I know, for a fact, that the end result of the AI songwriter will be something I would never consciously choose to listen to; rather, the project will stand as an exercise in formulating an idea, seeing it through, and restraining myself from making additional tweaks to fit my personal taste. The individual at work in this project will be the AI, something I’ll have to grapple with as its creator, and it will operate largely beyond my will.

The hope is to finally execute an AI that writes music. How I get there, how many challenges I’ll face, and how it’ll turn out remain to be discovered.

0 notes

Text

Brainstorming Assignment

To preface the actual content of the assignment, all of this is entirely fictional, particularly the “testimony” surrounding my hypothetical grandmother. That being said:

Research Report: The questions surrounding AI in music.

Among my three ideas was a proposal for a user-level artificial intelligence trained on musical data that can be used as a personal musical assistant for composers and students alike. Beyond the raw concept, an endless list of questions exist that I will attempt to document and try answering here.

What do you mean by “AI?”: Artificial intelligence is the product of exhaustive algorithms iterated thousands of times over the same set of data. For this particular use case, the AI will use a machine-learning algorithm to analyze pre-existing musical compositions.

What does a musical dataset look like? : Any number of things, from a collection of sound files to a spreadsheet of text data breaking down song structure, harmonic progression, song length, and the less tangible “feelings” songs inherently possess. It could take the form of a collection of classical music from the most esteemed dead whites who compose the music canon, or use any data from any culture or background to attempt to understand what makes music music.

Is this not just an automatic composer? : …yes and no. After being trained specifically to recognize, critique, and suggest musical content, the AI will absolutely possess the capabilities to compose its own pieces of music. That, however, is not the goal of the project: the AI is meant to act as a guiding hand for those unable to afford formal music education and a drawing board for professional composers to best sonify their endless compositional ideas.

How much is it? : For a subscription fee of a few dollars, you get the AI pre-trained in one genre of existing music (additional genres accrue additional costs). Alternatively, the AI itself is a free download that’s compatible with user-made libraries and datasets, as well as user-handled training. If you have a big enough computer, you can train the AI however you want to.

Why would I want this? : You’re interested in learning how to play guitar but can’t afford an in-person tutor on top of the cost of the guitar itself. You’re a composer struggling with writers block in need of a creative jumping-off point. You’re a creative coder interested in using the AI to generate autonomous music to your parameters with only a few code tweaks. You’re a parent who wants a cheap means to which your child can learn an extremely creative hobby. The use cases are nearly endless and its low cost allows for accessibility beyond the limited spectrum of professional musicians.

What would it look like? : The finished product will take the form of a downloadable software able to run on any modern computer, with a Lite version tailored around use on mobile phones. A physical prototype emphasizing portability is in the works.

Project Story: Companionship for end-of-life.

My grandmother, towards the end of her life, suffered from dementia. Dementia is more than forgetting your loved-ones’ names – it’s forgetting how to eat, bathe, breathe, forgetting who and where you are and losing higher functioning entirely. Dementia is an extremely expensive condition that, even with the best care, remains fatal.

My family knew that my grandmother’s dementia had come to a tipping point when she needed 24/7 supervision. My parents both worked exhausting jobs and I was too young to be able to fully support them, so the only option we were left with was hiring personal aids to constantly monitor and take care of her. We struggled for months to pay the bills, keep the aids hired, and keep my grandmother safe and healthy.

After a few months, we couldn’t afford to keep the nurses and we moved my grandmother in with us. Life was though: we had to take turns staying home to be sure my grandmother would eat or in case any emergencies were to happen. When something went wrong, like a short tumble down some steps, it always ended in a trip to the emergency room. Our bills piled up and soon we struggled to keep the lights on.

That’s when we discovered Columbia Automated Care, a system made in tandem with the country’s leading physicians to provide constant care at an affordable price. All it took was a small camera to bring our lives back to normal and provide the constant care my grandmother desperately needed. With a lump sum of a few hundred dollars for installation, CAC is covered by most health insurances and comes with cost-effective options to maximize care for the elderly. My family rests assured knowing my grandmother’s vitals are being monitored by the top doctors in the country, equipped to shuttle her to the nearest hospital at a moment’s notice should the need arise. Moreover, visits from on-plan doctors are partially covered by insurance and cost us about the same the bi-weekly check-ins we would bring my grandmother two on a regular basis.

We can finally afford to return to normalcy and be assured that our most treasured relative is in good hands with CAC.

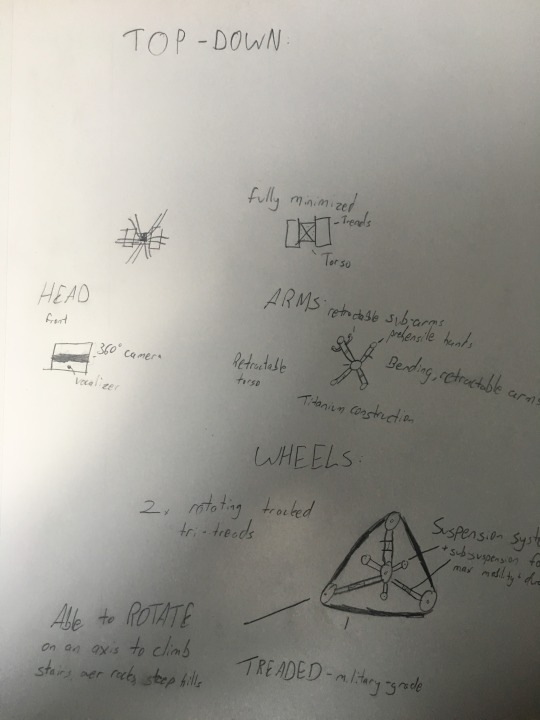

Specs/Sketch for mobile companion:

- Triangular, treaded wheel design allows for maximum mobility and ability to climb stairs.

- Collapsible design for easy storage

- Titanium construction for great weight-to-strength ratio

- 6 retractable arms to maximize carrying capacity

- Prehensile grip

- 360-degree camera for full awareness

- Vocalizer in any number of languages

The goal with the mobile companion is for EASE OF LIVING, particularly for prospective buyers who struggle with mobility-related disabilities. The mobile companion is capable of carrying hundreds of pounds in essential and non-essential cargo and folds down into a compact design to minimize its profile while indoors. Some very rough sketches are below:

0 notes

Text

Week 3 Response

“How to think differently about doing good as a creative person,” while still relevant now, is something a ton of white people should have seen in June and July. Within the last few months, nearly all artists, bands, or creators in general pledge to donate some or all of the income their work makes to bail funds, memorial GoFundMe’s, or community fridges. All actors carried through, to my knowledge, with their donations, and ultimately I’m leaning in their favor concerning whether or not the end result of their actions benefit those most in need.

There exist many glaring caveats concerning donations to a cause concurrent with a new work or product. I had this debate right as Elijah McCain’s memorial fund was announced: I planned on releasing a collection of music on on of Bandcamp’s free Fridays and giving all my profits to his fund. For about 2 hours, I was entirely convinced I was doing “good;” after the smallest shred of self-reflection, I realized I absolutely was preying on those mourning a Black death for my own benefit (even if it wasn’t financial). Social capital is (unfortunately) a very real and meaningful metric that establishes footholds across broad audiences just through outreach and good PR. Releasing any form of work, as a white, and promising to send funds raised to good causes is an act of social venture capitalism regardless of pure intentions.

Good acts are almost always fraught with innocent misunderstandings that massively jeopardize at-risk populations. The article does a great job in highlighting that there exist endless possible consequences that absolutely need to be addressed before one group attempts to act for the benefit of another. Going further than condemning the white saviorism rampant in neo-liberal culture, “How to think differently” asks the simple question of whether those who plan on helping are actually equipped to do so; if they aren’t, the article crucially points out that the risk of harm begins to outweigh the chances of doing good.

0 notes

Text

7 in 7 Reflection

I’d be amiss if I didn’t start this post by getting the obligatory out of the way: 7 in 7 was exhausting, extraordinarily challenging, and, at least for the day after, left me feeling like a hollow, idea-less shell.

That being said, I desperately needed something like 7 in 7 to get me back to being creative. Since high school, I’ve struggled immensely to create any work that wasn’t specifically for a class. The issue stemmed from extraordinarily toxic expectations I alone place upon myself when I start any creative project; over the course of about 10 years of not making anything for myself, the expectations were more paralyzing than they were a guiding creative force. 7 in 7 unwound years of my fear of making by mandating rapid, roughly-polished prototypes at least once a day. The only expectations at play were for deliverables at the end of each day, entirely up to us to dictate.

I managed to make something in 7 in 7 (my day 7 video audiofier) that I considered building an entire thesis around in undergrad. I proved to myself that prototyping is absolutely necessary to see any project through, undoing years of preoccupation with a finished product that kept me from starting any projects whatsoever. I managed to create a framework, in one day, for something I nearly spent a year making; I motivated myself to build what I wanted on my own terms and the end result, much to my surprise, was something I was proud of.

Just two days ago, I made an audio/visual piece that I submitted to an art showcase set to run mid-November. I brainstormed, prototyped, prototyped again, and came to a final iteration that, prior to 7 in 7, would have taken at least months if I ever overcame my fear of creativity at all. The piece I made will be shown in Manhattan in my first physical showcase I’ve ever participated in.

7 in 7 was brutal and a test of creative stamina, but in 7 days alone I found the courage to start creating for myself again. I thought that, for as long as I lived, the hurdle of creative fear would stop me from making my own art ever again.

After 7 in 7, that’s changed.

0 notes

Video

7 in 7, final day(!)

So.

I’d been meaning to make some engaging audio/visual work for 7 in 7, and I’m glad I finally found an excuse to on the last day. Something I’ve wanted to build for quite a while is a video audiofier - something that takes video and translates it into sound. The inverse is common among visual artists and takes the form of simple visualizers to entire music videos.

To do so within the bounds of my 7 in 7, I chose the most uncontrollable variable known in the realm of computing: noise. I generated reflective visuals that move and pulse to instructions provided by a 3D noise function. A reflective material spawns lumps and refracts light accordingly, random in theory and akin to a lava lamp in practice. Using noise as a parameter in visuals is common, but with these particular visuals, I chose to make noise the only real parameter that remains visible. The objective here is to provide little more than a visual account of the flow and movement of noise along its axes, in line with my documentary approach for 7 in 7.

The audio side of the work is a Max patch that averages the red, green, and blue values of a given video. First, the video is parsed into 3 equal columns, effectively dividing the video into a left, center, and right. Max then averages the RGB values in real time and uses the data it collects to control the volume on an assigned oscillator, all playing sustained variations on a C chord. The effect, with this video, is the sonification of noise without implementation of audio noise. I chose the sound to be consonant to challenge the idea that noise is an uncontrollable, chaotic force - rather than attempt to exert fruitless influence over noise itself, I chose to mic it with my own musical background in mind and let it speak through a set of strict limitations.

This prototype is absolutely something I’ll continue using and might just be the first big step in my larger goal of marrying audio and video in as non-novel a way as possible. The data gathered by the patch is used to control volume, but since the data is only a stream of numbers, it can be used to influence any imaginable digital device in as many ways as one could conjure. While the sine tones may be simplistic to the point of grating, the prototype itself is the creation I poured my heart into, and is the essence of my 7 in 7 bundled into one quiet package.

0 notes

Audio

7 in 7, day 6

Today presented me with the first moderately clear skies I’d seen in about a week. I’ve been meaning to go out into nature and document it living and breathing firsthand, and I found my perfect opportunity to do so. I had the initial thought of bringing with me a notebook and pen to document what birds I saw where, and maybe to produce some form of graphic score with who/what I found. After climbing down from my three-story walk-up, I noticed I forgot my journal. Too winded to go back and retrieve it, I walked to the park anyways to do what I typically do on days after rainstorms: bird watch.

Birds absolutely adore moist ground and soaked tree-trunks due their incredible abundance of worms, giving birders an opportunity to see clusters of rare creatures in a bundle, collectively pecking at the mud. Today was the first dry day after nearly a week of rain, and birds were everywhere: everything from tiny kinglets to massive, patrolling ospreys were out in droves enjoying the sun and their free meals. All means of exotic animals made their appearances, including a small black cat, but what particularly caught my eye was a rather unimpressive sparrow.

White-throated sparrows are notable for their particularly melancholy call, heard by some as “Poor Sam Peabody, Peabody, Peabody” or “Oh Sweet Canada, Canada, Canada” (these are the same people who argue fiercely about what exactly constitutes Canadian bacon). The song is a favorite of mine as its particularly sing-songy nature breaks through the din of vaguely-industrial park life to provide an entire psalm in a few short phrases. For such an unremarkable-looking sparrow, its song is one of the most well-known across the northern hemisphere.

Today, I decided to draw out the musical potential in the song of white-throated sparrows as an exercise in highlighting the music that exists beyond humanity, out of our control. The little song is meant to be simultaneously meditative, like bowed glass, and an example of how the white-throated sparrow’s song can be interpreted in numerous different ways.

0 notes

Video

7 in 7, Day 5

Today proved to be even more miserable and damp than yesterday, so my grand plans for finally getting decent documentation of the outside world were once again put on hold. Instead, I elected to document fire, the movement of light, and extraordinarily tiny changes as they occur in real time.

I was in luck as I managed both to lose my camera’s charger _and _cause my girlfriends camera to malfunction, so I was forced to film on my 7-year-old phone. To film, I propped my iPhone up on the sides of two other candlesticks that I originally intended on likewise documenting. The subject of the shot is a Ms. Myer’s candle that’s burnt about halfway through, burning for at least an hour before I started filming so as to get a good layer of transparent, liquid wax. The video here is about a minute, but it’s true runtime is 1 hour and 38 minutes; I chose to massively speed the shot up to give a sense of reward to anyone viewing without them having to sit through nearly two hours of a burning candle (something that would’ve made for a great and spectacularly obnoxious Fluxus piece).

Documented is the melting of wax, dancing of flame, typical goings on in my apartment, and first-hand account of my lack of proper recording gear. I also intended to make this video a much shorter GIF, but when I did so, it somehow managed to take up an entire gigabyte of space.

0 notes

Text

7 in 7 lookback in progress, how the readings influenced my process.

The readings this past week ranged from esoteric and near-meaningless postmodern musings of a white man to an entire book on playful design. The article on design justice, however, was most formative to my approach in its topical nature. I read the article before looking to see when it was published and, surprisingly, it was published within the last several months. Many of the issues covered in it were likewise topics of discussion in D4TC, but a particular nuance was the acknowledgement of white supremacy and heteropatriarchy ingrained in any tech mogul that willingly participates in capitalist exploitation (which is to say, any and all tech firms).

The reading analyzed the notion of intervention on others’ behalf and the monetization of diversity and inclusion in tech’s larger voice. The conclusions it reached were phenomenal and brilliantly thought out, but I found that I took a different message from the reading as a byproduct of several of its arguments.

I’m a white cis male. I exist in a world strangled by fellow white cis males, where populations fall and locations disappear due to white cis male ambition. Control and power is something we’re born into and firmly believe is our god-given right to exercise at everyone’s expense. Our voices are the loudest, our footprints the largest, our mass graves brimming with bodies browner than ours.

Art and design history, as its formally taught, is an index of white, patriarchal ideology in practice. The world as it is came to be from the perpetuation of a narrative of white saviorism that forgets its own genocides and forgives its own atrocities. We preach the power of productivity, fetishize and economize the workers most willing to be exploited, monetize culture and call it “exotic,” “foreign,” or, worst of all, “authentic.”

Hence, my 7 in 7 turned into an exercise in passivity. I documented and continue to document the things around me that proceed without human intervention; I exert no influence over my subjects and let their voices speak for themselves. Documentation, at its mechanical core, should not speak over its subject but instead amplify it. I like to hope that, with my 7 in 7, I’m taking the article’s straightforward address of white supremacy and patriarchy and doing what I can to undo it wherever I can in my daily life, starting from small prototypes and working up to larger, systemic change.

0 notes

Text

7 in 7, Day 4

Today was the day I’d been dreading: analog medium day. I’d been wanting to paint the sky since 7 in 7 began, but managed to rationalize that the sky as only worth painting on a sunny day. Now that New York’s rapid transition from Summer directly into Winter started as of this balmy morning, the sun is a commodity only the tops of skyscrapers can afford.

I knew, from the start, that I would end up having to paint something. My girlfriend, a journalist, came from an art background (which is to say her public schools didn’t cut funding to the arts and she understands how to draw a line) that I desperately lack. When she moved in, she brought her plethora of painting and illustrating goodies with her and has been encouraging me to use them for at least months. Now that I have, I grieve for the loss of a set of watercolor markers and a painting notebook put to waste with remarkably horrible work.

Since it’s particularly cold and wet today, I chose to paint the outdoors from the comfort of the indoors. I set out to document the exact view from my window using watercolors, capturing the brief burst of autumn color on the trees and the glum overcast behind it. My canvas was a sheet of 4x6 watercolor paper torn from the dregs of a well-used notebook. The watercolor at hand was in the form of soft-tipped markers. Within seconds, I ruined my documentary draft by failing to properly blend colors to best illustrate the shades of the leaves outside my window. Below is the image I used for reference until I lost patience:

I started the painting seeking to document a very small and mostly unimportant moment in time, putting the ever-changing and indifferent sky in the forefront to offer a futile attempt at painting something that never stays the same. Instead, I documented my coping mechanisms as I did my best to finish a painting on a thoroughly soaked canvas.

I unintentionally documented my spectacular lack of education when it comes to watercolor and painting in general far better than I documented the sky and trees outside my apartment. The exercise soon became a learning moment for accepting something I couldn’t change - this god awful painting - as something that exists as much as I do.

I called my girlfriend and desperately asked for tips, to which she suggested I think more abstractly. I tore another mini-canvas out of the same old sketchbook and tried only to depict the breadth of colors present in the previous painting. Using the same set of markers, a gratuitous amount of finger blending, and a faucet now stained in a sickly dark green that I’m sure my girlfriend will appreciate, I painted this:

The end result depicts more of a brilliant sunset than it does a cloudy Brooklyn day, but in terms of original documentary intent, it more-or-less hit the mark. The colors didn’t bleed into each other as I hoped they would, but it captured the palette of the sky nonetheless. In the process of drying the painting, I covered my hands in watercolor and managed to create a negative of the painting on a sheet of Bounty paper towel.

After all the damage I’d done, I decided to call it a day at this point. Unfortunately, today’s 7 in 7 is as much of a documentation of my lack of traditional art skills as it is a recording of an afternoon sky.

0 notes

Text

7 in 7, Day 3

Today was long. I got into a car and headed home, about an hour north, for the first time in 8 months. I then spent the majority of the day waiting on an endless line to cast my early vote.

My plans were to document the line, that I already expected to be massive, in some artistic medium that could best convey how the tide of voters swept across the entirety of Westchester county. I saw my two brothers for the first time since the pandemic began and I did my best to pick up where I left off in February. I saw my cat, who failed to recognize me for several hours. I caught my reflection in the mirror of the bathroom in the house I grew up in and found I aged 10 years since the year started. One brother spoke to me about his recent trip to the Berkshires with his fiance (they were just dating when I last left home) and the other seemed to be sure Dr. Fauci was, in reality, coming to conclusions he already reached months ago.

Exhaustion isn’t a word for what I’m feeling. It’s far deeper, a pinging and resonant sorrow knowing that I’d become a different person since the last time I was home. Trump memorabilia flanked the windows of my favorite places growing up; my family was full of stories about those lost in the pandemic. My cat did eventually recognize me and, naturally, threw himself onto the carpet expecting to be doted over as he was for the last 12 years. I couldn’t bring myself to touch him and instead only apologized.

There are an endless number of things at play that I can’t change. Worst of all, I can’t change that today proceeded as it did, and how a trip back to class in February ended in a homecoming after nearly a year. I’m realizing now my degree was within arm’s reach and never crossed my mind.

I can’t change how this is the human experience. My story isn’t unique, and that nauseates me. A pain that isn’t personal is a pain with no purpose, no payoff or moral to be milked into a greater work expressing the angst of one depressed white man. Everyone alive feels the same slow burn I do, a tepid iron growing hotter the longer you spend in the presence of the people you love without being able to live life as it was. Change is often for the better, but this one time at this particular moment, I want to document that I, against my better judgement, am actively wishing things would return to how they were before COVID. I want to note that watching my cat swat to get my attention was devastating then and I want to note that I hope to any god listening that it’ll be a bitter-sweet memory in the future. I want to note that life up north is greener: the autumnal tree canopy paints the gray skies a shade of flaming auburn this time of year. I want to note that standing in the same place for 3 hours is exhausting. I want to note that I’m noting all of this as a futile attempt at catharsis, praying things will soon get better.

They won’t. But the sentiment is worth documenting.

0 notes

Link

For day 2 of 7 in 7, I chose to address the particularly obnoxious phenomenon of my incredibly crowded and claustrophobic local grocery store. It’s near the top of my list for things I wish I could change: bumping shoulders with strangers in a pandemic is one of the last things I want to spend time doing. Unfortunately, the grocery store is the only one around me with any good, regional produce, so every time I run low on food, I have to go down the street to play COVID bumper cars with the neighborhood.

The idea to document the unchanging, permanently-full and close-quarters nature of my local store came to me as I spent my morning preparing myself for the shopping trip to come. In Critical Computation, the midterm requires us to make a playable game using p5 to the best of our ability. I figured that, since practice programming a game would be invaluable and particularly timely, I would make a game that best conveyed how deeply uncomfortable my local produce store is.

The objective of the game is simple: collect all 3 of the food items highlighted, all in the difficult-to-reach nooks that best characterize the store, and navigate around or through people to do so. The layout of the game is as close a scaled model of the real store as I could make, complete with shoulder-to-shoulder interactions and corridors that are far too small to navigate easily. Once you finish your shopping list, you can head to the exit and ruminate on how social distancing is a privilege while shopping.

The act of documenting, for this assignment, meant capturing an experience as best I could while providing as many objective realities I could feasibly fit within a game. There are always 20 people in the cramped store, and the shelves are lined up exactly as they are in reality; the user experiences the store first-hand without having to delve into a real sea of people to buy some garlic.

0 notes

Audio

One of the few prayers I remember from an exhaustively traumatic Catholic childhood reads:

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.”

My 7 in 7 attempts to embody such a sentiment in as many ways as creatively possible. Using a documentary approach, I plan on recording the events and goings on of daily life that lay far beyond my (or really any individual person’s) control. The challenge I face is defining the bounds both of what I can’t change and how I far I can stretch the idea of documentation before it loses its most generally prescribed meaning.

My first day, after a good morning of brainstorming, concerns the documentation of water: soft, fluid, malleable and simultaneously immensely destructive, capturing water as it exists in a specific moment in time leaves nearly all avenues of documentation open for use. I dug my heels in and decided today’s process of documentation would include no direct references to water, my subject, and would instead be using the process of documenting water as an exercise in data collection and manipulation.

At its most machined, humanless form, documentary is the collection of data. Documentation brings with it formal notions of objectivity (a spectacularly loaded term) and matter-of-fact-ness that unromanticizes a given subject for the greater goal of unfettered observation. With this in mind, I elected to take this approach of data collection and throw in a curveball - instead of photographing and recording the movement and habits of water, I used water as a source of raw data with which I could sonify an objective event.

The process proceeded as follows: I expected it to rain where I live today and was heartbroken when it didn’t. Instead, I used my handy leaking faucet as an access point to water-as-data, put a contact microphone into a Ziplock bag (this ended well for me but nonetheless was an incredibly bad idea), and positioned the mic under the faucet’s unceasing drip. I used the gathered recording as a source of input for a Max patch, effectively giving water, at least as it existed in a tiny microcosm in my bathroom, a harmonic voice.

The Max patch functions as follows: translating the amplitude of the recorded sound file into a stream of numbers, I set a threshold that, when reached, would send a message to the rest of the program to play a note. The note played is based off a drunk walk algorithm, a sequential series of numbers roughly influenced by each other to create a vaguely coherent pattern of numbers, and its duration is set entirely randomly. Using a favorite synth plugin of mine, I passed the note along into the source of noise-making, using a preset that claimed to embody water (again, this proved to be an exercise in accepting what I can’t change and picking my battles). The approach in mind with this patch was to push the bounds of what constitutes documentary and objectivity, ignoring straightforward documentation in favor of something more creative and interesting.

The project was also intended to have a visual compliment with a similarly generative structure. I learned, after 3 hours of fruitless work, that I was working with two unchangeable things: water as a permanent force of nature, and my underestimation of time and effort requirements that I absolutely knew would hinder me. Though I’m a bit disappointed I could only iterate on the audio for today, I’m glad I learned the hard lesson of setting realistic goals now rather than later in the week when time will be more of a commodity.

0 notes

Text

A Statement

So.

Just last week, for D4TC, I polished my manifesto as best I could. Now that an assignment calls for further fleshing-out, I figured I may as well post the manifesto in its entirety for reference.

A Manifesto for Makers

Good intentions aren’t enough.

Creatives possess the power to change the world – whether we do so for better or for worse is entirely within our control. We can choose to improve life for the many, for the few, or for the individual. Though betterment isn’t always benevolent: look, for example at American billionaires, living opulently at the expense of their hordes of mistreated laborers.

Betterment must never come at the cost of others. The golden rule, proposed in the New Testament[1] and later refined empirically by Kant[2], is flawed: interactions and iterations between individuals cannot improve reality for the whole. Creatives, again, face a forked path: view humanity as a conscious whole, or Otherize[3] entire masses into a means towards a paycheck. While we can’t escape the system of capital, we can do our best to mitigate the damage it wreaks.

Consequences must always be considered. If you create, you do so beyond the critical academic vacuum. To create is to do so for people, and to do anything for people is to know how your race, origins, past, class, belief, and goals can potentially cause harm. To be a creator is to think before you act, down to the most minuscule of minutiae; to know where you can, where you cannot, and where you must help. Creation for oneself is good practice, but creation for and only for others is where we, collectively, stand a chance against anti-human interests actively silencing and strangling us.

[1]So whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets (English Standard Version, Matthew 7:12).

[2] So act that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or in the person of any other, always at the same time as an end, never merely as a means (Kant 1785: 429).

[3] “The anthropological other […] is based on the notion of perceived differences and is a cognitive process involving observation, collection of data and theorizing (Sundar, 1997).” Distilled, the other is anyone deemed alien by virtue of differing ideology, background, or culture.

Reflecting on this, with the assigned David Graeber reading in mind, I’ll take a shot at writing a statement that best encapsulates me.

I justify myself by doing my absolute best to act as a reprieve. Living, regardless of the recent hellish pandemic that doesn’t seem to end, is a painful, exhausting process. My art, my work, exists as something to provide solace to anyone who happens to come across it. Solace itself is a loaded term, and from what I try to provide respite from differs from moment to moment and person to person. But I figure, in the spirit of acknowledging and accepting that reality seems to defy sense, that working towards easing the daily struggles of those around me is the only tangible reason I have motivating me to work at all.

1 note

·

View note