Dedicated to the land and language of Tepat, and its neighbors DeviantArt / Website

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I also have sometimes used descriptors like "orthodox," "traditionalist," "classical," and "progressive," etc. but I dislike these kind of terms because these are, (1) not specific enough - they have some of their own views which are important but not captured by these broad terms and (2) they are commonly used in English political discourse and come with their own assumptions about those terms that are often not accurate or simply irrelevant in Tepat.

There is also (eventually) a third group, which DOES have its own name, Qomism, because it becomes closely associated with the Kingdom of Qom, their dynasty, and their policies.

Elephants and Zebras

Concerning Tepatic ideologies: I have another interesting naming problem now.

Years ago I read writing advice to the effect: “If you’re writing and you don’t know the right word for something, don’t break the flow! Just write ‘elephant’ & keep writing. Later you can search-and-replace ‘elephant’ with the right word.’

I took that advice.

In Tepat, one of the main intellectual currents, during the Shattered Land Period, is mentioned repeatedly, so I needed some way to refer to them, but didn’t have a good, consistent name. I called them “The Elephants.” It stuck. Soon they had their ideology, Elephantism, their adjective, Elephantine, etc.

It gets worse. The other main intellectual current of this timeframe, opposed to the Elephants, also needs to have some DIFFERENT way of referring to them, contra the elephants, and also doesn’t have a good clear name. Guess what? I called them Zebras. Zebraic Zebraist Zebraites. The usage has become so thorough and consistent, I feel like I’m stuck with them, with a putatively serious document full of zebras and elephants.

Another problem? There aren’t elephants or zebras in Tepat. And probably not anywhere near them. Tepat doesn’t have a tropical savanna. Also even if there were, I don’t really have any explanation for why they would get associated with these intellectual currents. There’s no reason for Tepatites to be calling anyone these things.

And yet I’m not really sure about this, even if I do think up new, better names. How am I ever going to replicate a joke about someone wearing false stripes?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elephants and Zebras

Concerning Tepatic ideologies: I have another interesting naming problem now.

Years ago I read writing advice to the effect: “If you’re writing and you don’t know the right word for something, don’t break the flow! Just write ‘elephant’ & keep writing. Later you can search-and-replace ‘elephant’ with the right word.’

I took that advice.

In Tepat, one of the main intellectual currents, during the Shattered Land Period, is mentioned repeatedly, so I needed some way to refer to them, but didn’t have a good, consistent name. I called them “The Elephants.” It stuck. Soon they had their ideology, Elephantism, their adjective, Elephantine, etc.

It gets worse. The other main intellectual current of this timeframe, opposed to the Elephants, also needs to have some DIFFERENT way of referring to them, contra the elephants, and also doesn’t have a good clear name. Guess what? I called them Zebras. Zebraic Zebraist Zebraites. The usage has become so thorough and consistent, I feel like I’m stuck with them, with a putatively serious document full of zebras and elephants.

Another problem? There aren’t elephants or zebras in Tepat. And probably not anywhere near them. Tepat doesn’t have a tropical savanna. Also even if there were, I don’t really have any explanation for why they would get associated with these intellectual currents. There’s no reason for Tepatites to be calling anyone these things.

And yet I’m not really sure about this, even if I do think up new, better names. How am I ever going to replicate a joke about someone wearing false stripes?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

General info about Tepat coming along well. Lots of work sorting / organizing information about Tepat the last couple days.

Normally, whenever I get an idea about Tepat / other nations/languages, I write it down in one big document. It usually gets deposited at the end, “to be sorted later,” which I have rarely done, so the entire thing is kind of a mess. It is entirely inconveniently organized for reference, although it has become a sort-of-chronological record of my thoughts about worldbuilding. And it’s not completely unnavigable, because I do tend to give each new note a good heading. But basically it’s a huge dump of assorted pieces of information about anything, not in any order of relatedness.

It became a headache because at one point I copied it to removable media to work on another device, and ended up with two copies, slightly differing. Before they diverged more I decided to compare and recombine. I’ve taken the opportunity of reading the whole thing to organize the info. So the plus side is that it will be more consistent and sensible & a lot better information on Tepat will probably be available soon.

The people of Sopih have a wider variety of hair and eye colors than humans on earth. In addition to brown, green, and blue eyes, gray, yellow and pink or purplish eyes are also common. Like humans on earth, humans’ hair turns gray and finally white with age. Sopih has a fair number of people with naturally gray or white hair from birth. This is often considered a sign of wisdom, and that a person should become a shaman or sorcerer. It is particularly common in the priestly castes of societies which have them.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ear > Money

Today’s weird etymology is “ear” > “money” in Swira.

To make things more interesting, this is not exactly the Swira word for “ear,” but the word from a related language, borrowed into Old Swira as a doublet, because there are numerous tribes interacting on the plains, with shifting dominance. So in a Towic language *a-kiŋku-we > *akunkuwe > *akunkō or something like that which is cognate with Swira tigu-i.

The reasoning is the evolution of currency systems in Tiptum. Many cultures have used gold and silver as money, such as Tepat, before it switched to paper. Not all though - Muqali, which is in mountains far from the sea but has valuable mines, traded metals to the east coast for seashells, and an east coast word for “shell” entered Muqali as ilsak ‘money.’ Many different kinds of currency are possible, alongside or instead of metals. In the northern regions wealth was counted in animals, and hides or pelts were common trade items. Anyway, as usual the barbarians were ahead of civilization in certain practices, including paper money, or rather leather money.

It is pretty common for hunters to provide just part of an animal, such as a tail or ear, as proof for bounties. Some nomadic tribes cut a part of an animal - such as the ear or tail - to represent an entire hide, essentially as proof of having a whole such hide, and was taken as having the value of a standard pelt, and traded as such. The ear would be branded with the brand of the herder, and additional trust could be assured by the reputation of the herder. As livestock were absorbed into larger and larger herds, and the herders confederated into larger and larger hordes, the personal brand of the overall chief of the confederation became a de facto official currency, long before chiefs got around to enforcing currency with legal mechanisms. Hence, “ear” meant money, or a unit of money, and “brand” meant “mint.”

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Straits and the Southwest Corner

Twin lighthouses, Tôqhaw Lam and Pok, are found at each end of the strait known as Tôlman, "Fog Turn," where ships from the south turn into the Inner Sea. Lôkh i-Mûn, Warning Island is nearly midway between the prongs of Tiptum at the entrance to the Sea. The fog that rolls in at night vanishes by noon without ever touching the ground, leaving the sun with perfect clarity for the rest of the day. Following the glow, ships from the Outside dock safely for the night at Tôlman, have their cargo inspected by Tepat in the morning, and wait for the clarity of afternoon to round the point into the Inner Sea. Such is the whole west coast, south and north of it.

South of the straits is the desert peninsula Pet. Despite the millions of water droplets hanging over it each morning, this is the driest region of Tiptum. Some plants do actually grow here, all of these which are efficiently exploited by the native Heiepe, who inhabited the peninsula before it was colonized by Tepat in its attempt to control shipping through the strait.

The ubiquitous ground cover, in distant patches, is needle grass (Yuktepat: /khut-chut/), which fends off all foragers with stiff, sharp-pointed leaves. Brave humans have nevertheless collected it in order to sew clothes. Other residents include the only slightly more appetizing spiky fatleafs (/ti-yôp-phuk/) and bladeleafs (/ti-yôp-lam/). The fatleafs’ bulbous leaves are covered with short thorns that spiral upward toward the tip of the leaf. Every few years they produce flowers on a single tall stalk. Those patient enough to gather the leaves and cut off the thorns can eat them, or pulp them to make juice or beer. Bladeleafs’ leaves are nested within each other, with edges so sharp the natives have used dried ones as hunting weapons. The Heiepe make bowls out of the clustered plant leaves, which they cover with cloth and set outside at night. The fog condenses in the cloth and the leaves as dew, by which the people obtain a very useful substance known as water.

The southwest desert areas of Tiptum are typically dry and receive little rain, but are affected by neighboring tropical weather systems. The region receives most of its precipitation in brief and sudden torrents from west-moving tropical storms that begin in the Inner Sea. These storms often dissipate when they reach the desert, but sometimes they reform and gain strength on the other side of the ocean, swelling into hurricanes that end up blasting the coasts of Aipura and Tricunia.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

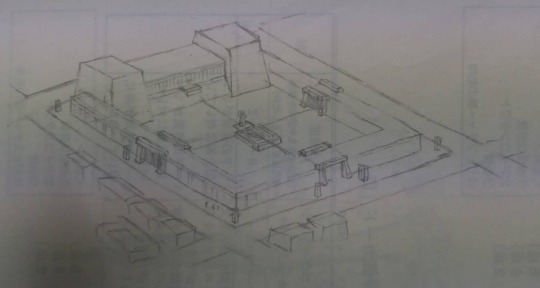

Tepatic-style public square - in Qom capital?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Qom Homeland

Western Tepat is the heartland of Qom, one of the Tepatic Nyow successor kingdoms, and the one that ultimately reunited the realm. Although Qom itself is extinct, the region remains colloquially known as Qom. It may be divided roughly into coastal, highland, and interior regions. The interior region, to the east of the mountains, fades into the general Tepatic plain and the land of the Three Rivers.

Coast - The seaward west coast is dry and hot during the summer, when almost no rain falls. It receives almost all its precipitation during the winter months. The mountains just inland force the winter clouds to drop almost all their rain, leading to sporadic torrential rains in the foothills, which the sandy soil struggles to absorb, with sometimes disastrous consequences. Thin capillaries of rivers completely overflow, and sleeping riverbeds suddenly awaken, usually very rapidly, leading to flooding.

Because of the hot dry summers, the main growing season is over winter. Qom’s massive public works focused on preventing winter flooding through creating artificial lakes. As a bonus, these stored enough water to irrigate some places during the dry periods, making summer agriculture possible, and increasing the region's food base (for awhile at least, before environmental degradation happened).

On rarer occasions, the region may be struck by unusual hurricanes, like the Desert. Hurricanes usually travel west, and veer away from Tiptum, but sometimes they may be blown northeast, most commonly striking the Heiepe region.

The Mountains - actually, a mixture of hills and valleys - tend to be drier, although small rivers make agriculture possible in the valleys. The old Qom capital, Ngemyam, was located in one such valley near one of the major passes over the mountain. Mountains on the western side tend to be wetter, and are often covered with shrubby woodland. The mountainous terrain itself tends to be fairly rounded and not steep or jagged, such that they are not particularly difficult mountains to cross, or to live amongst. A fair amount of hunting, for rabbits, deer, and other game animals, is possible in this region. In some places, snow is possible on mountaintops in the depths of winter.

Yôntluq - the dry strip - or Yônikhut - the Grass Belt - Interior Qom, toward the eastern side of the mountains, is relatively flat, and somewhat drier year-round. The winds that cross the mountains have usually spent their moisture before crossing, and when they barrel downhill, blow strong, dry, and hot over the land. On the other hand, these places can suck moisture from interior Tepat, and in turn the Inner Sea. Most precipitation occurs in the summer from occasional thunderstorms. Rangeland and shrubland occur here, often used for grazing. Grass and trees get higher as one moves eastward away from the mountains, and this fades into the general environment of interior Tepat. This area was inhabited by some Swiric and Towic peoples in ancient times, before being assimilated by Tepat. They practiced semipastoral lifestyles, alternating between grazing on the foothills and gardening in villages along waterways. This region was the original “home” of Qom, but Qom was pushed back by defeats by Thûp, and this region was incorporated into Thûp briefly, leaving Qom Proper only the foothills and the regions beyond. Hence Qom border stations and guard towers were built in a line along the foothills, at the start of roads and rivers.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tepat

The lifeline of Tepat is the great river valley cutting diagonally through its center. The two major rivers of the north, the Pemet and Phitim, merge in the center of the country at Xhangtyel, the 'Meeting of Waters,' to form the Yot Klun, 'Wide River.' The /Klun/ is also Tyel Kyet or Yot Kyet, possibly meaning 'Braided River' and referring to the fact that the waters of the two rivers are ‘twisted’ together here - or that the lower reaches of the river, winding and surrounded by oxbow lakes, resemble braided hair.

Different regions of Tepat have different seasonal patterns of precipitation. The eastern part, with a humid subtropical climate, gets precipitation mainly in the summer in the form of thunderstorms, with less in winter. The western regions with more Mediterranean climates have dry summers with rain in the winter. Where the two climate zones transition, there is a zone with two annual peaks in precipitation, in the summer, and the winter. By coincidence, this area corresponds largely to the drainage basin of the Klun River. The availability of so much water year-round made it ideal for agriculture and transport, however, floods were also a risk. The eastern branch of the upper part of the Phitim River, through which most of the country’s thunderstorms and tornadoes pass, was known as the Winds’ Road, or Khat i-Xyul.

Hanam: Southern Tepat

The southern part of Tiptum is known Hanam. The Klun River exits here in a vast delta, with a family of small muddy lakes around it. This is the muggiest part of Tepat. The Lenuk people who lived here in ancient times lived primarily in boats, traveling the labyrinth of lakes and rivers.

Western Tepat

The far western parts of Tepat (including Qom) have a Mediterranean climate and a largely chaparral vegetation, which gets sparser toward the southwest as it merges into desert. Oak is a big component of the chaparral in the dry hills. It is also full of dark green, thick-leaved or scaly evergreen shrubs. In the state of nature, these shrublands are subject to periodic burns. Some of the plants reproduce with seeds encased in very thick, hard hulls that do not open until scorched by flames. Volatile oils in the leaves facilitate combustion. They are also valued as medicines and flavoring in wines and sauces.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The North

Nowek

Fog fills the cliffs and fjords to the latitude of the Conciliarity’s northern border, and further. At that point, the clouds are nigh continuous, such that the sky over the forests is just gray on green - faint gray above, dark green below. Prior to Tepatic colonists, most of the inhabitants were Taknic, suggested by the lack of labial sounds other than [w] in placenames.

The Northern Interior

The fog stops when it hits the mountains. Past them, clear, cold, and dry skies observe the progression of airy pines to burly shrubs and finally mere bristles of grass. By that time though, it has reached the Eastern Range and Tumpen, and pines reclaim their rank. Cold desert appears on the slops of the Tumpen mountains as they approach the steppes. Further north, in the Lake-and-River region, dense forest predominates, criss-cut by ziggy rivers with paths so turning that they themselves barely know which way they drain. This area is centered on one huge lake, Lake Súli, the largest lake in Tiptum and one of the largest in the world. Most of the Lake and rivers are edged by wetlands. Not exactly great for human settlements, but they host many migrating birds, which people depend on to hunt seasonally. The far north is mostly tundra, with humans turning to the sea for sustenance. The large northern peninsula known as the ‘Far Handle’ (Lepthel) is barren, and some areas are almost continuously covered with ice. Impossible though it may seem, Taknic hunters occasionally venture even here.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Inner Sea

The Yuk Sôl or Inner Sea is a very large salt-water body situated just north of the equator and enclosed almost entirely by the continent of Tiptum. As part of the continental plate of Tiptum, it is much shallower than the open ocean, and has its own circulation patterns. Nourished by the heavy discharge of Tiptum’s rivers, and tropical rain, it is less salty than the open ocean. It is also home to many unique species of fish, and the coastal areas are rimmed by vast undersea sponge forests. The lack of exchange with the ocean traps heat, making the Sea the warmest one in the world. Numerous hurricanes spawn in or near the Yuk Sôl, but because they follow westerly paths out of the sea, they rarely threaten areas of Tiptum itself.

On a geological time scale, the Sea itself has been an ephemeral feature, and may not have existed all even recently. During previous ice ages, as ocean levels fell, the sea was cut off from the outer ocean, and nearly evaporated, leaving behind a vast desert dotted with salty lakes, and with many of the great rivers flowing into them.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiptum

Tiptum, the continent on which Tepat sits, is the easternmost and second largest continent. The continent as a whole stretches from the tropics to the polar regions. Tiptum is divided roughly into two half-continents, known as Lamnûm (the South) and Poknûm the North). The area where they join, running through Notoq, is sometimes referred to as Nûmtip, the ‘navel’ or ‘waist’ of the continent, or Yôntip, its ‘belt.’ The continent is also divided into east and west by the Tiptum Cordillera, which mostly runs parallel to the eastern coast. It includes the Notoq, Muqali, and Wasak Plateaux, the Muqali mountains, and the interconnecting Amtom Ranges in the northeast. Tepat claims all land south of 37 degrees latitude, as well as land within 50 km on either side of the Pemet, Lower Phitim, and Luqtal rivers not otherwise within that range.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nok

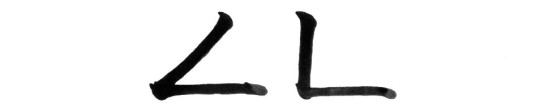

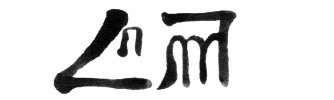

Nok is one of the simplest glyphs - two forms shown above.

Nok [nɔk˺] means ‘angle.’ Another meaning, going back into prehistory, is any major bendy part or joint of the body - particularly the knee, but others as well. Hence, nok i-noq ‘knee, leg-angle’ or nokh û-qaw ‘elbow, arm-angle.’

Above: nokh û-qaw

Nok also means ‘corner.’ From this sense it has extended to mean ‘area,’ ‘region,’ especially a peripheral, local place in contrast to a main, central place. This can be seen in expressions like yuk nok ‘regional speech - dialect’ or phan nok ‘regional cuisine.’

Left: Yuk nok Right: Phan nok

Nok2, written as a mountain over an angle, is another word, but possibly related to the first one. Now found in Yuk Notoq, and reflecting Tepat’s past in hill people, the nok of a mountain is a point on the ridge of a mountain, such as were a trail reaches the ridgeline, where the slope changes or the trail bends, and a good view is often possible.

EDIT: changed chip nok > phan nok

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! Yes, most likely, I'm interested to see someone try writing something in my conworld. Plenty of (unposted) random info to share. I don't really know how this works either though so I'll go mull a bit & get back

Hi Avatar, I saw you posting asking for story requests. What kind of stories? What's your rate?

Hey there—sorry about the delay. In this case, I hadn't really thought about a rate, at least not yet. But if you want a story set in your world, or my world, or someone else's world—be it a fairytale, or a war story, or a slice-of-life, or what-have-you—I'd very much like to give it a try. Get myself writing again, as it were.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

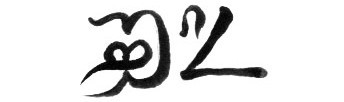

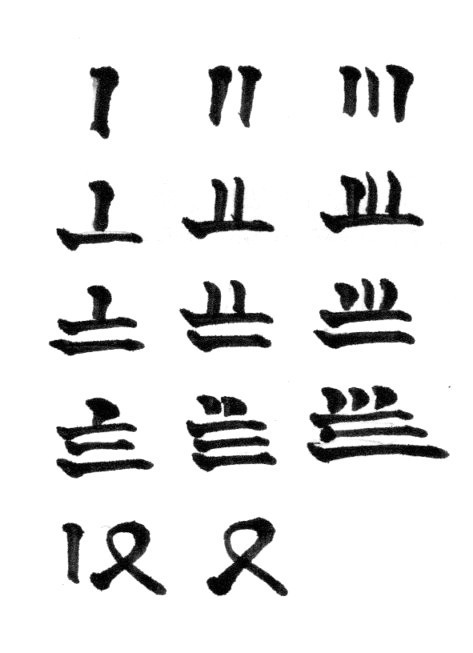

Tepatic Numerals

Tepat also has a system for writing numbers. It uses a system of vertical and horizontal bars, similar in concept to tally marks for keeping track of things in English.

One is represented by a vertical bar. Two is two vertical bars, three is three vertical bars.

After three though, each group of three is turned into a horizontal stroke. Then additional ones are placed on top. Hence, four is represented by a vertical stroke on top of a horizontal stroke. Five places two strokes on top of the horizontal bar. Six has three vertical strokes.

Then at seven, six is converted to two horizontal strokes and another vertical stroke placed on top.

Three groups of three become three horizontal strokes. This continues until we get to twelve.

Twelve is written with one vertical stroke, and then a zero, because this is base twelve. The zero is a loop that looks like a little ribbon - the same as the negative operator stroke.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

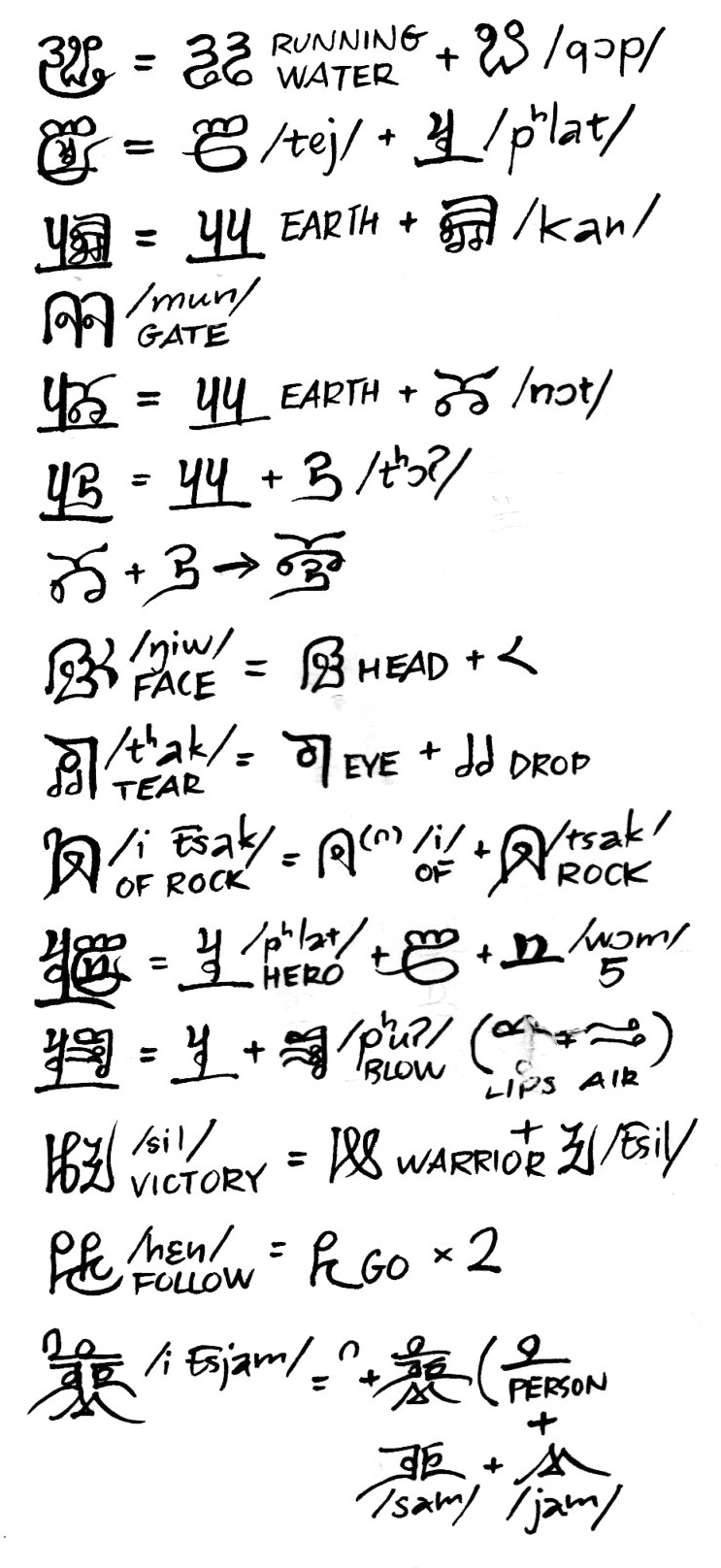

Further explanation of the glyphs

Facing the Tears

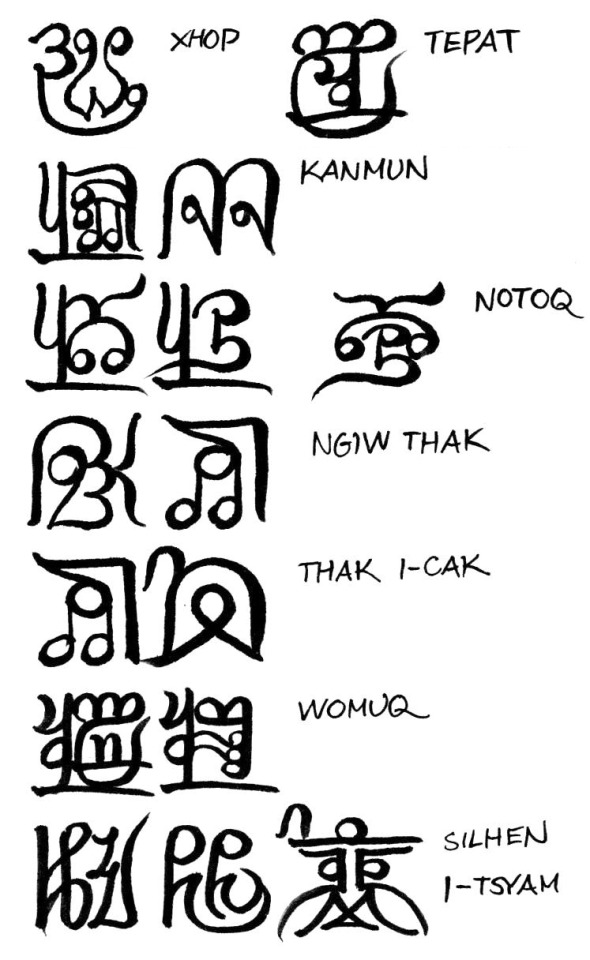

In Luk, the easternmost of the petty states of former Tepat, the hills of Kanmun form the southernmost extension of the small highland at the very edge of the flat Plain of Tepat.

One prominence looks east, across the river Xhop, with the first rise of the Notoq highlands visible far behind. Beyond lay Notoq, the cradle of what would become Tepatic culture, now cut off from its cultural progeny. Once this hill was known as Ngiwthak, because it was directly across from Thak i-Tsak, the Tears of the Rock, in Notoq. The name had gradually slid downhill onto the drab town that squats between the hills and the river, although you could not see the tears themselves from the town.

Another, the western one looks across the whole plain of Tepat. Here Womuq once stood, when he came to Tepat, seeing the rich vastness which he would come to own, and now a schoolboy had this same view.

In the valley, when Silhen i-Tsyam received lessons, his father made him sit in a courtyard facing the river. He made him gaze out and try to discern the Rock, as he listened, even though the rock and even its location were invisible from this point.

He had never seen the Rock, but had heard that water sprung forth ex nihilo from the rock itself like tears, dripping down into the river. The homeland was crying for its lost children.

Sometimes Tsyam’s father took him up the near eastern hill to look at Notoq: A distant and dim smudge of higher hills. Pale green and yellow blocks of farmland. The river, a shining silver knife cutting them, cleaving plain and hill and separating Notoq from its cultural progeny.

He found a small yellow flower on a rock atop the hill.

“This flower is shorter than your ankle, but it grows on the rocks at the top of mountains. Though it is tiny, it sees more than any of us. It is not the flower’s own greatness, that gives it this advantage, but the place it has chosen to grow,” father said, remembering the Book.

Silhen bent over and turned his head around upside down until he was looking at exactly the flower at its own height. But he could not see the rock, with the flower in the way. He was disappointed. He wanted to see as far as his dad said he could see. He got down on his knees right at the flower’s level, and saw the grass, too close to see. He blurred his eyes and saw the grass, then the distant hills, then the grass, then the hills, the grass, the hills, grass, hills…

Father continued, “I am but a small child. But I can see far because I stand on the shoulders of my father and grandfather. That is learning. That is culture.”

“Daddy, pick me up!”

“You’re getting too big now.”

They trekked over to the Western hill, looking out to the Plain of Tepat, now shattered.

“None of these small kingdoms could overcome their own selfishness to bring the whole back together.”

It did not occur to Silhen then why they should all need to be brought together.

“Daddy, I will never be selfish.”

“That is the first step on the path to become a wise man.”

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tepatic words / names found in the passage:

Facing the Tears

In Luk, the easternmost of the petty states of former Tepat, the hills of Kanmun form the southernmost extension of the small highland at the very edge of the flat Plain of Tepat.

One prominence looks east, across the river Xhop, with the first rise of the Notoq highlands visible far behind. Beyond lay Notoq, the cradle of what would become Tepatic culture, now cut off from its cultural progeny. Once this hill was known as Ngiwthak, because it was directly across from Thak i-Tsak, the Tears of the Rock, in Notoq. The name had gradually slid downhill onto the drab town that squats between the hills and the river, although you could not see the tears themselves from the town.

Another, the western one looks across the whole plain of Tepat. Here Womuq once stood, when he came to Tepat, seeing the rich vastness which he would come to own, and now a schoolboy had this same view.

In the valley, when Silhen i-Tsyam received lessons, his father made him sit in a courtyard facing the river. He made him gaze out and try to discern the Rock, as he listened, even though the rock and even its location were invisible from this point.

He had never seen the Rock, but had heard that water sprung forth ex nihilo from the rock itself like tears, dripping down into the river. The homeland was crying for its lost children.

Sometimes Tsyam’s father took him up the near eastern hill to look at Notoq: A distant and dim smudge of higher hills. Pale green and yellow blocks of farmland. The river, a shining silver knife cutting them, cleaving plain and hill and separating Notoq from its cultural progeny.

He found a small yellow flower on a rock atop the hill.

“This flower is shorter than your ankle, but it grows on the rocks at the top of mountains. Though it is tiny, it sees more than any of us. It is not the flower’s own greatness, that gives it this advantage, but the place it has chosen to grow,” father said, remembering the Book.

Silhen bent over and turned his head around upside down until he was looking at exactly the flower at its own height. But he could not see the rock, with the flower in the way. He was disappointed. He wanted to see as far as his dad said he could see. He got down on his knees right at the flower’s level, and saw the grass, too close to see. He blurred his eyes and saw the grass, then the distant hills, then the grass, then the hills, the grass, the hills, grass, hills…

Father continued, “I am but a small child. But I can see far because I stand on the shoulders of my father and grandfather. That is learning. That is culture.”

“Daddy, pick me up!”

“You’re getting too big now.”

They trekked over to the Western hill, looking out to the Plain of Tepat, now shattered.

“None of these small kingdoms could overcome their own selfishness to bring the whole back together.”

It did not occur to Silhen then why they should all need to be brought together.

“Daddy, I will never be selfish.”

“That is the first step on the path to become a wise man.”

30 notes

·

View notes