18F. Chinese Singaporean. I write about music, identity and the Internet.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

eight lines about the united states of america - yh huang

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

TWO WRITERS WALK INTO A ROOM

with no exit. Two writers walk into a room the wrong way around. Two writers stand in front of two doors, and only one of the doors will save you, and only one of the writers is telling the truth. That's how the puzzle goes, right? You are a writer. You are a door. You are the thing waiting at the end of the choice, the full stop snarling and waiting to pounce.

Two writers walk into a room, and one of them says, You know as well as I do that I don't want to be saved.

The other one says, I never said I wanted to save you.

The first one says, I wanted you to try.

Two writers walk into a room and they don't say anything. Two writers walk into a room and they can't meet each other's eyes. Two writers sit in a silent room, and they can't hear anything but the sound of their own voices.

Two writers walk into a room, and one of them says, Would you say yes if I asked if the door behind you leads me to where I want to go?

The other one says, Well, would you?

One of the writers wants to be loved. One of the writers wants to be pitied. One of the writers hates the other one's guts. One of the writers thinks they'll both win the Pulitzer. One of the writers is putting words into the other's mouth. One of the writers is unhinging their jaw. One of the writers is laying out the rules. Only one of the writers is telling the truth.

Two writers stand in front of two doors. Only one of the doors can save you, and one of the writers can't do anything but lie. But how do you know that's true? Maybe both of them are the liars, and maybe neither of them are:

Maybe they're just trying, despite everything, to tell each other what they think the truth to be. Trying to say the right thing, trying to solve the puzzle, trying, trying, trying to fumble for each other's faces in the dark. Two writers walk into a room, and one of them says, I love you, and the other one says, I'm sorry. Two people walk into a room, and they write right past each other.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

old thing from the Situationship Trenches of 2023. transcript below cut

HOW TO FALL IN LOVE WITH AN AMERICAN BOY

for AL

So let's define x as falling, as love, as boy. The most important rule of loving an American boy is this: to call what you have anything else but what it is.

2. Think about him in a supermarket aisle, holding a pack of cup noodles in the flavour he likes. Think about him as you're rifling through fifty-dollar sweaters with his college crest on them. Think about him in a Subway, a Safeway, a somewhat-kind of-okay well very obsessive way.

3. Tell him that you're in America for Christmas. Make a joke about Walmart, about the weather. Reread his text back a thousand times. Giggle. Twirl your hair. Kick your legs a little, just because you can. So it feels familiar? Of course it does. That's the whole point. ¹

[1: To fall in love with an American boy you have to first resign yourself to cliché. But that's not really right, is it? Resign's such a funny word: both reluctant compliance and forceful withdrawal. To fall in love with an American boy is to willingly make yourself a cliché. To shrink yourself into something easy to define, easy to swallow, a three-act story with a rise and fall. Maybe that's better for everyone involved, you included. Maybe it's better to be Butterfly. Because Butterfly, despite everything, is still a part people want to play.]

4. Buy an extravagant peppermint-gingerbread-mistletoe concoction at an overpriced hipster cafe, just for the hell of it. When they ask for your name—this is important—don't give them your legal name (they'll butcher it) or your English one (you've always hated it). Instead, give them his nickname for you. Pay attention: you don't want to miss them calling it out. An actress always watches for her cue.

5. On long road trips, draft and redraft lines of poetry in your head. Maybe this time you won't forget them the moment you open your notes app. Maybe this line will finally be The One, whatever The One means. Maybe you'll finally be able to explain yourself to him, autopsy yourself, sell yourself like a story: blurbs and back-flaps and signatures and movie tie-in covers. (Plus a pronunciation guide at the back, just in case.) Good poetry, like everything else, has a little bit of performance to it. A little bit of acting. A little bit of lying. ²

[2: So, okay, fine. Let's say it's not love. Let's say it never was. Let's say you just wanted your own personal Beatrice, the wizened mentor who dies to make way for the second act. So what? You can't write about yourself forever, a snake eating its own tail. You used to have real friends. You used to be a good writer. You used to be a good person. Now the most interesting thing that's ever happened to you is a boy. What happened to the Bechdel test, babe? What happened to being a strong female character? Are you even a character at all?]

6. Try and figure out when you stopped being a person and started being a trope. Give up halfway through, and settle for the small stuff instead: When you overhear snatches of accented conversation in the Target aisle, try not to jump to the conclusion that someone’s turned up their Tiktok a little bit too loud. Walk through streets like movie sets and feel a little bit like you've slipped through a silver screen, an unreal thing in a real place. Try not to think that this is the most real you've felt in the last few years.

7. On the morning of Christmas Day, have a spirited conversation with him about your favourite species of dinosaurs. You didn't even know he knew anything about dinosaurs, but apparently the dream-version of him does. You don't know anything about dinosaurs, either, but you would learn everything about them if it meant he would keep talking to you. You don't know when you started talking to your friends more in dreams than in real life.³

[3: He'd kill you if he knew you were thinking of him like this. He'd kill you if he knew you dreamt of him the way you did, the way you still do. Well. Probably not kill, but something close to it. Maybe one of these days you'll stop. Maybe one of these days your predictive text will forget who he is. Maybe one of these days you'll have something to live for that isn't the fact he knows your name.]

8. Wake. He's gone, of course. You're in a sofa bed in a motel somewhere in San Jose. The morning light’s filtering through the blinds. Look at them and think The morning light’s filtering through the blinds, and think, or maybe not filtering, maybe slicing, maybe leaching— in your head open up your notes app, rifle through Dictionary.com. Try and figure out when you stopped writing for yourself and started writing for him.

9. Your parents are still asleep on separate ends of the big bed. For the first time in a week they're not yelling. The room is quiet. Nobody in the world knows you're awake. Nobody's looking at you. Nobody's watching you. This moment is entirely yours, and yours alone. What do you do with it? ⁴

[4: The world is so vast and so small and none of it is real in any meaningful way except for him. You're twelve hours away from home and still every road leads back to the only person you've ever known how to love. Or at least you think you love him. Probably. If not— if not—

What do you do with it? What a stupid question. Is there anything else you know how to do? Despite all appearances to the contrary, this is a story written in past tense: You rolled over. You checked your phone. He hadn't texted you. Some part of you wasn't surprised. The rest— well, figure that out.]

10. Write him a story. Tell it to him.

#i put a lot of this into love songs in a foreign language so im not sure if there's anything new here#actually i don't even think this was a situationship at this point this was just a Situation#writing#poetry#now back to uni apps 🫡

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyone else up thinking about the carter family and the modernisation of 30s america and technology and also immortality. or is it just me

#i could not get william out of my mind unfortunately this is the result william if youre reading this Pls Drop Lore We're Starving#old time#1930s#americana#folk#the carter family#zine#art zine#digital zine#Web weaving

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

LOVE SONGS IN A FOREIGN LANGUAGE | YH HUANG

With apologies to A.L.

When I'm seventeen, I put a picture of Loretta Lynn in the back of my clear phone case. With the same care my best friends take in decorating trading cards of Jungkook and Jisoo, I get a pair of tweezers and my most expensive stickers, and make an afternoon out of sticking little daisies all over a glossy black-and-white printout of Loretta in the 70's. In the picture she's leaning against a tree, her dark hair long and thick, smiling at the viewer with the same unshakable confidence she's always had.

The next day, I slap my phone face-down on the cafeteria table. My friends go oh-my-god and you-actually-did-it and wait-that's-kinda-cute. We propose swapping some of our cards–I get Minho, she gets Randy– until the conversation derails to exams and teachers and the presentation that's due on Wednesday but none of us have started.

Then it's two weeks later, and when I wake up, thirteen hours after Kentucky does, I read that Loretta Lynn has passed away. A clickbait news site uses the same picture for her obituary.

Sometimes I feel like everything I love is already gone and I just don't know it yet.

-

so why do you like country music, my friend Alex asks me once.

Alex is American, but the South is as alien a place to him as it is to me– he grew up in suburban New Hampshire, after all, in an impossibly huge house bursting with beach-themed paraphernalia. America, to him, is Dunkin' Donuts and perfectly manicured lawns and the pale foam of the Atlantic cutting itself open over and over again against the sharpness of the rocks.

I squint at my phone. It's late, and I'm probably supposed to be asleep by now, but I'm fifteen and the year is 2020 and time stopped mattering somewhere in the middle of March. It's not like I have school tomorrow, anyway.

I type and retype my message for a while. Then, because it sounds about as good a reason as any, I say, idk i just like the fiddles

It's true. I do like the fiddles, and the steel guitar and the autoharp and the banjos too– the joyful clatter of it, the melody so much like flight. During quarantine, I spend a lot of time lying on the bedroom floor with my headphones on, blaring bluegrass at ear-destroying volumes. Maybe if I play it loud enough, if I squeeze my eyes shut hard enough, I can transport myself into the real thing: a honky-tonk with wood-panelled walls, heat and whiskey in the air, some familiar rhythm reverberating through the floorboards. Sometimes I even imagine myself there in the crowd, singing along.

–

In 1957, a song called Geisha Girl by Hank Locklin topped the country and western charts. It's about this American guy who arrives in Japan, falls in love with the titular Japanese geisha, and leaves his American wife for her. Well-trodden ground, both in art and in reality– after World War 2 ended, tens of thousands of Japanese women married American men for love, for money or for everything in between. Locklin's Geisha Girl became so popular that a song was released in reply to it–Skeeter Davis' Lost to a Geisha Girl, in which Davis takes on the persona of the man’s lover back home, scorning her fickle-hearted husband. As is common in reply songs, lyrics from the original are changed to fit the new perspective:

Locklin sings, Have you ever heard a love song that you didn't understand / when you met her in a teahouse on the island of Japan?

Davis sings: Why a love song with no meaning makes you happy, I don't know / I've lost you to a geisha girl where the ocean breezes blow.

A song you don't understand. A song with no meaning. A song in a language you don't speak. What's the difference, anyway?

In post-war Japan, a whole plethora of country music bands sprung up around the country, playing American hits for homesick soldiers: Tennessee Waltz, Lovesick Blues, Your Cheatin’ Heart.. The closer they were to the originals, the better. They'd bill themselves as the Japanese Hank Williams or John Denver or Patsy Cline. The catch? Some of these singers barely spoke English. painstakingly memorising each lyric until their L's and R's sounded just right. Yet, every Friday night they'd get up on that stage and sing songs they didn't understand about a country they'd never been to.

Just a few years ago, America had been Japan's worst enemy. But here their sons and daughters were, singing American songs, working in American jobs, marrying American men. In the present day, you could almost argue that the tables’ve turned: middle-schoolers debate anime at the cafeteria table; red-blooded blue-collar workers drive Toyotas and ride Kawasakis.

One thing that's stayed the same, though– American boys, Japanese girls. Love songs in a foreign language. Kind of a funny thing.

–

For hundreds of years, the West has been fascinated by the geisha. In Puccini’s 1904 opera Madama Butterfly, fifteen-year-old Butterfly is making her living as one when she’s bought by an American soldier named Pinkerton. He marries her, knocks her up, then ditches her in Japan while he marries an American woman. The whole time, Butterfly’s left to pine for him, and when Pinkerton returns to Japan with his wife, Butterfly stabs herself so that her son will be able to live in America with his father.

(Pinkerton, as you can probably tell, is kind of an ass.)

I keep thinking about Butterfly in that lonely, empty house in Japan, waiting for someone who didn’t love her back. I keep thinking about Alex: Alex and his horrible stupid round glasses and his old embarrassing love of Panic! at the Disco and his stupid cringe emojis, Alex who’s still the smartest person I know, Alex who was the first guy to ever pay attention to me. When I’m sixteen, I think about him almost constantly, a constant hum of obsession in the back of my head. I know I’m in love with him because that’s how all the songs go: Randy Travis declares that it’s deeper than the holler / stronger than the river; Deana Carter says it’s bittersweet / green on the vine; Keith Whitley confesses that it’s what I hear when you don’t say a thing.

Alex asks me, so what do you like about country music? And I don't know what to say to him, so I say nothing at all.

–

They read it in the tea leaves and it's written in the sand

I found love by the heart-full in a foreign distant land

–

Alex likes Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, the outlaws and the jailhouses and the pistols at the hip. My classmates like the feminist murder ballads, where they think she did it but they just can't prove it, where afterwards the girls sell Tennessee ham and strawberry jam / and they don't lose any sleep at night. I personally have a fondness for the silly and unserious: Alan Jackson extolling the virtues of grape snow cones, George Strait selling me the Golden Gate.

In the end, though, what I end up listening to most are the old songs– the really old ones, all the way back to the dawn of recording, the Golden Age of the radio. These songs, collected in the 1920s and 30s, are impressively varied in lyrical content: you’ve got the ones that are basically a soap opera stuffed into three minutes flat (Lorena, My Heart’s Tonight In Texas); the religious ones (Anchored in Love, Will the Circle Be Unbroken); the relatable ones (Give Me Your Love); the unrelatable ones (The Dying Soldier, No Depression In Heaven). What I like about them, I guess, is the familiar hiss of the vinyl, the way the lyrics are both specific and universal at once, their ability to make a time and a place that you’ve never been to before feel, inexplicably, like home.

Alex and I aren't anywhere near poor– his parents are both surgeons, and I spend my evenings trying not to fall asleep in increasingly expensive private lessons. But then again, neither were the Japanese country singers of the fifties and sixties, mainly college kids from elite families who could afford custom-made cowboy hats and genuine guitars. Hell, even the prince of Japan was said to be a country music fan in his youth. None of us have worked in the fields or in the mines, none of our parents have had to tell us here's your one chance, Fancy, don't let me down. We're the people Garth was referring to when he sang about that black-tie affair, those social graces, the ivory tower.

What does it mean to understand a song? How do you sing something and really, truly mean it?

–

When I'm sixteen, my fun fact on the first day of school is that I listen to country music. When I go out with my friends, I wear ankle-length denim skirts and lacy blouses and tie my hair in twin ponytails. I beg and beg them to listen to Loretta, to Dolly, to Patsy. In response, they buy me a Cowboy of the Month calendar and save me in their phones as "the horse girl". In one inexplicable picture that we've since lost, I've got my face in my hands, trying to hide my laughter, as my friends gleefully blast a Fox News clip about Randy Travis' drunken escapades.

So maybe my taste in music is the most interesting thing about me. What else is there? I'm not very pretty, only sometimes funny, and, to my eternal embarrassment, not good at all at being Asian. If I was smarter– fine, if I was Alex, Alex with his books and essays and critical theory– I might say that I do everything I do because I don't want to be the whitest girl in a room full of Asians (lame, boring, suck-up) but the most interesting thing in a room full of white people (exotic, rare, unique). A geisha girl, dressed in Oriental style.

Even so, I don't like to think that that's all there is to it. You can shrink the world down to words on a page, map out the complicated intersections of nations and culture and war that make up the popular imagination of America, call it pentatonic scales, the mixolydian mode. Of course there's value in that, I know– but all that stuff's a foreign language to me. You can try to explain why music sounds the way it does, but in the end you just have to hear it for yourself.

–

For a genre obsessed with authenticity, modern country music's chock-full of performers: Toby Keith singing We'll put a boot in your ass, it's the American way, Hardy singing My small town is smaller than yours, Jason Aldean singing, I sit back and think about them good ol' days / The way we were raised and our southern ways.

A geisha's a performer, too, in a way. She trains her whole life to sing, to dance, to entertain. In yet another adaptation of Madama Butterfly, David Henry Hwang's play M. Butterfly, a Communist actor seduces a French man by pretending to be a woman for years. When the actor's finally caught, he's asked how he got away with it. He responds: Because when he finally met his fantasy woman, he wanted more than anything to believe that she was, in fact, a woman.

Don't tell this to anyone else, but when I curl my hair and put on lip-gloss and toddle around in heels, wondering if Alex would like what he sees, I feel like I'm a walking caricature in the shape of a girl. When I’m online with him I simper, I preen, I ask stupid questions just to keep him talking to me– and he likes it, or at least I really hope he does. Sometimes, in the middle of the night, I wonder what'll happen if I stop performing. I wonder if there’s anything left of me below the performance.

I used to worry that I fell in love with something that doesn't exist: the myth of America, the barbeques and the cornfields and the porches, the honky-tonk and the church social and the choir all singing, the cowboys on their vast, empty ranches. A place that's already gone, or else never existed at all– but what does that matter? An unreal place for an unreal girl. If everyone's performing, then no one is.

–

How much of this is true, then?

It's true as backroads and cold beer and pickup trucks. True as private jets and cowboy hats and exaggerated drawls. True as Nashville and Wallen and the CMAs. Which is to say, it's as true a story as you want it to be.

–

Tell the home folks that I'm happy, with someone that's true I know

I love a pretty geisha girl where the ocean breezes blow

–

In the months around my eighteenth birthday, my parents start screaming at each other. Suffice to say, they never really stop. I take up temporary residence in the school library instead, and spend my afternoons staring at maths textbooks while regretting every decision I’ve ever made. My exams are drawing closer. I’m sure I’ll fail them. It doesn’t feel real. Nothing does. I can’t bring myself to look at my future, I can’t, and yet like the long black train / coming down the line I know what’s going to happen when it hits me, and I know, I know– it’s not gonna be good. I start learning how to fall asleep to the background noise of things getting thrown. When my friends come over to study, they call the house beautiful. I guess it is.

On the way back from school, pressed into a corner of a sardine-packed bus, I put one earphone in and watch the sunset fall over the expressway, the heat turning the sky a gorgeous, deadly pink. Loretta Lynn sings: Well, I look out the window and what do I see? / The breeze is a-blowing the leaves from the trees / Everything is free, everything but me. The Chicks sing: She needs wide open spaces / Room to make her big mistakes. John Prine sings: Make me an angel that flies from Montgomery / make me a poster of an old rodeo / Just give me one thing that I can hold on to / To believe in this livin' is just a hard way to go.

Meanwhile, in my headphones, a thousand different stories unfold, familiar missives from some far-off place: a son buries his parents. A wife kills her husband. Two childhood friends fall in love. A girl convinces her father to let her marry her boyfriend. A woman pins a runaway to a motel wall. Somebody calls his ex, even though he shouldn’t. A mother sells her daughter to an older man. A traveller gets on a train. The unfamiliar place names rush past. Amarillo, Charleston, Jackson, Cheyenne, Chattahoochee: evidence of an existence outside of calculus and grammar and pushing my desk against my door to block it. In my head I picture as if through a window some wide, sprawling prairie, some open starry sky, and think of Mary Oliver – so this is the world. I’m not in it. It’s beautiful.

–

(Meanwhile, online: it’s a different story.)

–

If it was a breakup, would it have been better? There's no shortage of breakup songs in country music, after all. Like, What right does she have to take you away / when for so long, you were mine? Like, I'm crazy for loving you / Crazy for thinking that my love could hold you Like, Nothing much for us to say / One last goodbye and you drove away.

Instead, it’s the stupidest, most mundane of reasons: we just stop talking. I couldn’t tell you exactly why. For me, I’m wrapped up in exams, family stuff, a clown car full of childhood friends crashing their way back into my life without warning; for him, he’s busy at Harvard, busy with his new friends and new projects and new–

Okay. Fine. His new girlfriend.

I can’t blame him. I don’t have any right to. I still don’t know whether I actually loved him or I was just sixteen, lonely and looking to write myself into a song. Still, after I learn that he’s dating her, I fall into a haze of social-media stalking: I scroll through their Instagrams, their Twitters, anything that’ll tell me more about who he was, who they are. She’s cute, I’ll give her that, and they’re cute together, the kind of forever and ever, amen couple whose profiles are full of heart-shaped chocolates, of candid kisses and in-jokes I’ll never get to hear.

(A love song with no meaning. A language you don't speak.)

For weeks and weeks on end I dream of him, but the really funny thing is that even in these dreams he’s nothing but a spectre: texting me, calling me, writing long-winded letters in the mail. The closest I ever get is this dream where I’m walking through his hometown, the one I looked up in Google Earth in a fit of desperation. It’s just like I thought it would be, every house gorgeous and stately and ancient, the trees barren but still grand. My hometown’s always been warm. It’s the one thing I have in common with the people in the songs, that overwhelmingly oppressive heat, the kind that sucks all the energy out of your bones. Even though Alex lives at the edge of America, Stephen King and sweaters country, in the dream it’s not cold at all– Georgia hot, hometown hot. As I run from house to house, ringing every doorbell, the roads seem to stretch out beneath my feet until the next door seems oceans and continents away. Nobody’s home. Nobody’s there. In the dream, I’m not surprised.

Sometimes I worry that everything I love is already gone, but I guess I knew that already. That doesn’t mean I didn’t love it.

–

When I'm eighteen, my parents spend a small fortune on a family holiday to America, some last-ditch effort at holding the household together. I miss most of it, however, because the moment I step off the plane I come down with the worst cold I've ever had in my life. Thankfully, during the last couple of days I begin to feel a little bit more like a human being and not just a collection of symptoms, so I manage to go down with my family to the shore.

Maybe it's the ghost of the fever coming back to haunt me, or maybe it's just December, but the beach is bitingly cold, the evening light only just poking through the clouds. Standing there, I find myself thinking– predictably– of Alex. We haven't talked in months, at this point: the last thing I texted him was im in the us lol to which he responded Haha enjoy, and that's about it.

On some other shore, so far away we might still be in different countries, Alex is at Harvard writing essays about America– learning how to understand it, how to shape it, how to make it somewhere he can love without reservation. But I'm not him. I know, now, that I know nothing at all about America: not the blue and far-off one in my songs. but the real place, full of contradictions, land of guns and welfare and Walmart and the Free.

I keep going back to what Alex asked me when I was fifteen, when we barely knew each other: so why do you like country music? And it's only here, now, freezing in a down jacket on the California coast, that I finally have an answer for him.

I think: because every good country song is a love song in its own way.

I think: because country music is the only thing I've ever known how to love.

I think: I have stood and watched the sun rise from the waters of the sea / and I've wondered how much beauty in this cruel world can there be / My dreams are all worth dreaming and it makes my life worthwhile / to see my pretty geisha girl dressed in oriental style.

I think: does there really need to be a reason, A?

From somewhere behind me, I hear someone call my name. I turn. It's my mother yelling: “Come back to the car! It's getting cold!”

“Coming!” I yell back, and run to her.

–

Before I have to go back home, I manage to get my hands on a Shania Twain t-shirt, which honestly makes the entire trip worth it.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rock me mama like the wind and the rain Rock me mama like a southbound train

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

SIX OBSERVATIONS ON VISION / YH HUANG

1. I've always had bad eyesight. That’s just how it is. My mom and my siblings are shortsighted too, but mine has always been the worst. I was the first kid in my kindergarten class to get glasses--and the only one, for a minute, but that didn't last long. By the time I was sixteen, there were only a handful of kids I knew who didn't wear them. I read this article once that said that one in every three children in this country develops myopia. It's genetic. Inherited. We can't help it. Or so it said.

2. Lately I've been thinking about inherited things: what’s our fault, what isn’t, what can and can’t be changed. Lately it feels like everything I touch I change for the worse. Lately I've been holding my screens too closely to my face, squinting to make out the signs on the train, unable to make out the leaves on each tree. Lately it feels like I'm blurring out of my own grasp.

3. Your eyesight is supposed to stop declining when you’re sixteen. But that's not really true, not for me. A lot of things that were supposed to get better from sixteen didn't, and anyway I've never gone six months without my prescription increasing. When I was a kid I used to stare out the window as my mom drove back home from the eye clinic, wallet a hundred dollars lighter and disappointment so thick that even I could see it. Too much phone, she'd mutter to herself. Too much device. I'd try to apologise, but she'd always keep her eyes on the road. For what? she'd say. It's not my problem. Be sorry for yourself.

4. So Father, forgive me, I've sinned again: my phone’s a square in the darkness an inch from my face. My glasses are somewhere on the floor, collecting dust. In time I'd come to regret this, but that’s no matter: here you are, painted in cubist smears and squares, boy crowned with bokeh like a Hollywood flick. Untouchable, lovely boy-- not in spite of, but because: lovely like the far-off blue shadows of the hills, lovely like street lamps stretching into starlight, lovely like an old film movie, the floating dust shifting and changing when the light hits your skin.

5. I don't know how to look at you without seeing myself. I don't know how to look at the world without seeing you. Maybe that means the two of us are what's left of the world: brains in neighbouring jars, sharing the same fluid. Or maybe that just means that I've been selfish all my life-- that this is just, has always been, me finding my reflection in the angles of your face. Boy in pixels, boy in frames, boy sharper on screen than in real life: everything beyond you’s a blur. When I try to look out the window, all I see staring back is me, me, me. I'm sorry I love you. I'm sorry I don't. I've never loved a thing that wasn't bad for me. That’s just how it is.

6. So my prescription's increased again. I'll have to get it checked.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's one thing I can't understand

Some women get pleasure pleasin' like a man

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

O I wish I was white marble Cold and white on some far shore This poor heart would cease from troubling And I’d feel the pain no more

#watched tbosas and have 30s music on the brain so#also. this song is so#ambrose bassford#coded#sorry but it's the truth#self upload#adamandi#I guess#Spotify

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

a paranormal investigator asks for directions // 28.10.23

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are songs that I've heard my whole life and think of as children's songs or just plain dumb, but there can still be gold in them if you get past the hackneyed way they're treated. For example, the spiritual "Do Lord." Do Lord, do Lord, do remember me (repeat three times) Way beyond the blue Or variants of the above. I actually used to sing this in church once in a while, but essentially thought of it as a children's song, one that was too repetitive and shared its melody with too many other songs. Then the other night, I heard Willi Carlisle doing what was essentially Mississippi John Hurt's arrangement and a few stanzas caught my attention: Remember all Your dying groans, and then remember me When the world's on fire, Lord, remember me Surprisingly poignant. I got out my guitar and played it and have been playing it for a couple days.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The autoharp as we know it today was invented by Charles Zimmerman in the 1870s, and is not a harp at all, but a chorded zither. ("Autoharp," like Band-Aid and Kleenex, is actually a trademark.) Zimmerman hoped to use the instrument to establish his own system of music notation. The notation was not a success, but the instrument was, becoming hugely popular in the Gay 90s. In the first few decades of the 20th century it was introduced to rural Southerners via mail-order catalogs and traveling teacher-salesmen. The primary attractions of the autoharp to rural musicians were its novelty, initial ease of playing, and its playing of chords, a novelty to musicians used to the melody of fiddle and voice or the melody and drones of the banjo. The most important group in the early history of commercial country music, The Carter Family, mixed the new sound of the autoharp with the equally-new guitar. Less attractive was lack of expression due to fixed strings, the instrument's quietness, seated playing position, and need for frequent, skilled tuning. (Pop Stoneman: "People were lost when they went out of tune. I bet there are thousands of 'em up in garrets for that reason.")

Ernest "Pop" Stoneman was the first to record with the autoharp, using the instrument solely as accompaniment. The most important musician to play lead on the 'harp was Maybelle Carter, the guitarist and harmony vocalist for the original Carter Family, who took a few clearly melodic breaks on the early 50s recordings with her daughters, "Fair and Tender Ladies" and "I Never Will Marry." Maybelle also evolved the style of playing the autoharp held vertically against her chest so she could stand and work a microphone, a style used by practically everyone today. (Autoharps are designed accordingly, with the chord bars positioned toward the wide end of the 'harp.)

If you're interested in the autoharp, a good place to start is the Smithsonian Folkways reissue Masters of Old-time Country Autoharp. This contains music originally released in the 60s by the Folkways record company, featuring Pop Stoneman, Kilby Snow, and Neriah and Kenneth Benfield, and has excellent, extensive notes.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The Greenbriar Boys were part of the urban folk revival that had the distinction of being one of the first, maybe the first, urban, northern bluegrass groups. Such a good band. This song is a version of that old familiar tune "White House Blues," and I think their source was Riley Puckett, who recorded it as "McKinley's Rag."

Say, Mr McKinley, why didn't you run? Seen that man a-comin' with a Johnson .41 From Buffalo to Washington Doctor, doctor, Do all you can A man just shot my husband with a handkerchief over his hand

Doctor comes a runnin, takes off his specks says Mr McKinley, you done cashed your checks Ms McKinley in Brooklyn dressed all in red weepin' and a mournin' for her husband was dead

Roosevelt's in the whitehouse doing his best McKinleys in the graveyard, he's taking his rest

Hush little children, don't you fret, you know you'll draw a pension at your papa's death

Jailer said to Czolgosz, "whatcha doing here?" "Took and shot McKinley, gonna take the electric chair" Czolgosz told the jailer, "Treat me like a man, "You know that when I die I got to go to Dixieland."

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

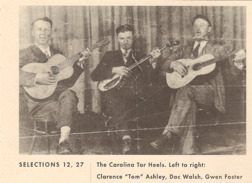

Clarence Ashley (1895-1967), known as Tom, accompanied by a young Doc Watson.

Ashley grew up in Tennessee in his grandfather's boarding house, where he learned songs, ballads, and how to play the banjo, first from his mother and aunts, then from itinerant lumberjacks and railroad workers lodging at the home. In his own words, he was "always crazy about the show business," and around 1911 began to travel with medicine shows as a singer and comedian. When not touring, he supplemented his farming and sawmilling income through busking.

Ashley began his recording career in the late 20s, eventually recording as part of Byrd Moore and his Hot Shots, the Blue Ridge Mountain Entertainers, and, the best known, the Carolina Tar Heels. The Tar Heels consisted of Ashley, Dock Walsh on banjo, and Gwen or Garley Foster (no relation) on harmonica.

Many rural recording artists knew songs of considerable antiquity that they didn't offer to record company A&R men because they had strong family or community associations, or were thought too old, too long, or not entertaining enough. Ashley's recordings like "House Carpenter" and "1929's "Cuckoo Bird" are important examples that link "pure" folk music with early commercial recording. During one session, Ashley was asked if he had more material, and asked the A&R man if he had ever heard any "lassie makin'" songs. (Some have found the term "lassie makin'" suggestive; it simply means a song associated with the making of molasses!)

Tom's lassie makin' tunes were backed by a rippling, archaic-sounding banjo accompaniment that he used a special tuning for, which he called "sawmill." The discs sold well and eventually captured the attention of northern record collectors in addition to Tom's southern neighbors. Both "Cuckoo Bird" and "House Carpenter" were issued in 1952 as part of Harry Smith's seminal six-record set, Anthology of American Folk Music. By then, Tom had retired from the medicine show circuit and was earning a living as a trucker. By the 1960s, he still performed occasionally, but as a comedian with Charlie Monroe and the Stanley Brothers, unaware of the nascent folk music revival and growing interest in his music.

In 1960, northern musician and folklorist Ralph Rinzler of the Greenbriar Boys happened to meet Ashley at the Union Grove Fiddlers' Convention in North Carolina. The meeting led to Ashley recording for the Folkways label, a concert appearance in New York, and American and European tours. Ashley proved to be a driving old-fashioned entertainer who, between his solos with the banjo, sang to the accompaniment of a band of talented neighbors he'd recruited, which included the then-unknown Doc Watson. He spoke about his career resurgence by comparing his life to a rose that had bloomed in summer and bloomed again in the middle of winter.

Plans for a second European tour were canceled upon Ashley's diagnosis with cancer. He died in 1967.

youtube

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Another from the repertoire of my favorite guitar player, Mississippi John Hurt. The ever-popular See See Rider.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Listening to transistor radios

(Ralph Morse. 1959?)

142 notes

·

View notes