#Economic Decoupling

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

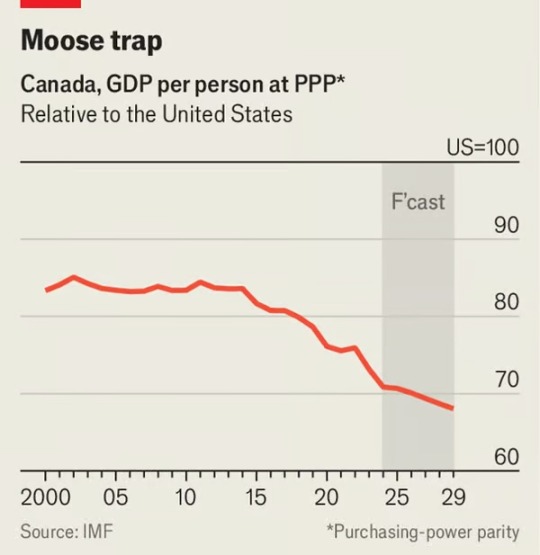

Why Is Canada’s Economy Falling Behind America’s? The Country Was Slightly Richer Than Montana In 2019. Now It Is Just Poorer Than Alabama

— September 30, 2024 | The Economist

Photograph: Associated Press (AP)

The economies of Canada and America are joined at the hip. Some $2bn of trade and 400,000 people cross their 9,000km of shared border every day. Canadians on the west coast do more day trips to nearby Seattle than to distant Toronto. No wonder the two economies have largely moved in lockstep in recent decades: between 2009 and 2019 America’s gdp grew by 27%; Canada’s expanded by 25%.

Yet since the pandemic North America’s two richest countries have diverged. By the end of 2024 America’s economy is expected to be 11% bigger than five years before; Canada’s will have grown by just 6%. The difference is starker once population growth is accounted for. The imf forecasts that Canada’s national income per head, equivalent to around 80% of America’s in the decade before the pandemic, will be just 70% of its neighbour’s in 2025, the lowest for decades. Were Canada’s ten provinces and three territories an American state, they would have gone from being slightly richer than Montana, America’s ninth-poorest state, to being a bit worse off than Alabama, the fourth-poorest.

The performance gap owes little to covid-19 itself. Canada did have a deeper recession than America after covid struck, partly because of stricter and longer lockdowns. Its gdp fell by 5% in 2020, compared with 2.2% in America. But Canada soon caught up. The country’s national income grew by 4% between 2019 and 2022, nearly on par with America’s, which expanded by 5% over the period.

The first of these is the services industry, which makes up about 70% of Canada’s gdp. In the aftermath of the pandemic Americans splurged on goods, which boosted manufacturers north of the border (American consumers gobble up around 40% of Canadian factories’ output). But they have since switched back to spending on domestic services. “The composition of American growth hasn’t been favourable to Canada,” says Nathan Janzen of Royal Bank of Canada (rbc), a bank. The job of powering Canada’s economy, therefore, falls even more to its own services sector, which relies on demand from Canadian households and the government.

Instead the divergence is more recent: since 2022 America’s economy has motored ahead, leaving Canada’s in the dust. The reason is not some bump on the road but what lies under the bonnet. Two drivers of Canadian growth have sputtered.

Chart: The Economist

Unfortunately, that demand has been throttled by higher interest rates. Monetary policy has had more “traction” in Canada than in America, says Tiff Macklem, the central-bank governor. In the latter, most mortgages are fixed for 30 years, whereas in Canada they are typically set for five. A greater share of Canadians than Americans have already seen their mortgage payments rise. This is all the more painful as Canadian households bear more debt, relative to income, than anywhere in the g7 club of large, rich countries. They now fork out an average 15% of their income to pay back debt, up one percentage point since 2019. And unlike Uncle Sam, Canada’s government has not tried to soften the blow by loosening the purse strings. It ran a deficit of just 1.1% of gdp in 2023, compared with 6.3% in America.

The second faltering growth driver is Canada’s petroleum industry, which accounts for 16% of exports. Canada underinvested in new production for years after 2014, when a collapse in oil prices hurt its fuel-dependent economy. In America, by contrast, oil-producing states suffered but consumers cheered. When prices spiked after Russia invaded Ukraine, investors did more to support American shalemen; the country’s crude output has rocketed. It was one-quarter higher in the first seven months of 2024 than it was during the same period six years ago. Canada’s has grown by only 11% over the same period.

Oil’s decline penalises Canada’s economy at large, because it is one of the country’s most productive sectors. That adds to a long-standing productivity problem. Growth in output per hour worked across Canada has been sluggish for two decades. It increasingly resembles Europe rather than America, which has benefited from a tech boom that has largely eluded Canada. Its gdp per capita since the pandemic has risen more slowly than that of every other g7 country bar Germany.

What Canada lacked in productivity it could long make up by having more workers, thanks to high immigration. Between 2014 and 2019 its population grew twice as fast as America’s. Canada has historically been good at integrating migrants into its economy, lifting its gdp and tax take. But integration takes time, especially when migrants come in record numbers. Recently immigration has sped up, and the newcomers seem less skilled than immigrants who came before. In 2024 Canada saw the strongest population growth since 1957. Many arrivals are classified as “temporary residents”, including low-skilled workers and students. They are more likely to be unemployed or in low-earning jobs, dampening growth in income per person. Canada’s unemployment rate rose to 6.6% in August, from 5.1% in April 2023.

Take all this together and it is clear that the seeds of the decoupling were sown much earlier than the pandemic, with sagging services the latest in a series of ailments. There are no quick fixes. Canada’s central bank has cut interest rates three times so far this year, from 5% in May to 4.25% today. But many borrowers will still feel worse off because they have yet to renew their mortgages. Immigration restrictions have been introduced, including a cap on international students, but that won’t solve Canada’s chronic productivity problem. Catching up to Alabama may soon seem like a distant dream. ���

#Finance & Economics#Economic Decoupling#Canada 🇨🇦 🍁#United States 🇺🇸#Canadian Economy#Montana#Alabama

1 note

·

View note

Text

This is an older article (from 2021), but I'm posting it here because I realize a lot of people don't know this is happening. There seems to be a narrative in certain corners of the internet that we haven't made any measurable progress on climate change at all when the opposite is true--while we need to do more as quickly as we can, we have already significantly moved the needle on the amount of warming in our collective future.

It wasn't all that long ago that it was debated whether it was even possible to meaningfully decouple emissions from economic growth--now it is beginning to happen for several countries and more are headed in that direction.

To compensate for instances where wealthy nations might be "exporting" their emissions to other countries, this data attributes emissions from imported goods to the importing country (and subtracts them from the exporting country).

Here are some graphs from a more recent analysis done in 2024 by the International Energy Agency, where you can see that this is also beginning to happen even in countries seeing rapid development like China and India.

While decoupling at this rate is not sufficient to get where we need to be to properly address climate change (and there is an argument to be made that slowed growth or degrowth may be necessary to fully curb unsustainable emissions and resource consumption especially in wealthier countries) the fact that it's happening at all shows remarkable progress beyond what many expected to be possible not so long ago.

#decoupling#emissions#carbon emissions#hope#good news#hopepunk#solarpunk#climate change#global warming#fossil fuels#economics#economy#environment#data#environmental issues#ecogrief#climate grief#climate anxiety#climate crisis

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

One simple way to look at it is to take the rate of emissions reductions achieved in countries that have successfully decoupled, and see how long it would take for them to fully decarbonize. That’s essentially what Jefim Vogel and Jason Hickel — researchers at the University of Leeds and the Autonomous University of Barcelona, respectively — did in the Lancet Planetary Health study. They found that, if 11 high-income countries continued their achieved rates of emissions reduction, it would take them more than 220 years to cut emissions by 95 percent — far longer than the net-zero-by-2050 timeline called for by climate experts. “The decoupling rates achieved in high-income countries are inadequate for meeting the climate and equity commitments of the Paris Agreement and cannot legitimately be considered green,” the authors wrote. In an interview with Grist, Vogel likened optimism around gradual decoupling to saying, “Don’t worry, we’re slowing down,” while the Titanic races toward an iceberg.

[...]

“Absolute decoupling is not sufficient to avoid consuming the remaining CO2 emission budget under the global warming limit of 1.5 degrees C or 2 degrees C and to avoid climate breakdown,” concluded the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in its most recent assessment. Instead of making growth greener, some economists call for a whole new economic paradigm to address converging social and ecological crises. They call it “post-growth,” referring to a reorientation away from GDP growth and toward other metrics, like human well-being and ecological sustainability. Essentially, they want to prioritize people and the planet and not care so much what the stock market is doing. This would more or less free countries from the decoupling dilemma, since it eliminates the growth imperative altogether. Raworth, the professor at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, calls her version of the post-growth agenda “doughnut economics.” In this visual model, the inner ring of the doughnut represents the minimum amount of economic activity needed to satisfy basic needs like access to food, water, and shelter. The outer ring signifies the upper limits of natural resource use that the Earth can sustain. The goal, she argues, is for economies to exist between the inner and outer rings of the doughnut, maintaining adequate living standards without surpassing planetary limits. “Our economies need to bring us into the doughnut,” Raworth told Grist. “Whether GDP grows needs to be a secondary concern.” Vogel and Hickel go a little further. They call for a planned, deliberate reduction of carbon- or energy-intensive production and consumption in high-income countries, a concept known as “degrowth.” The rationale is that much of the energy and resources used in high-income countries goes toward carbon-intensive products that don’t contribute to human welfare, like industrial meat and dairy, fast fashion, weapons, and private jets. Tamping down this “less necessary” consumption could slash greenhouse gas emissions, while lower energy demand could make it more feasible to build and maintain enough energy infrastructure. Some research suggests that reducing energy demand could limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C without relying on unproven technologies to draw carbon out of the atmosphere.

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The European Union’s greenhouse gas emissions fell 8.3% in 2023 as a surge in renewable energy installations helped displace coal.

This means the bloc’s emissions have declined 37% since 1990, while its economy has grown 68% over the same period.

The divergence indicates “the continued decoupling of emissions and economic growth,” the European Commission said in an update, adding that the region is on track to reach its target of reducing emissions by at least 55% by 2030.

According to an analysis by the European Environment Agency, based only on existing climate measures and planned actions, the EU will reduce its emissions by 49% by 2030.

Electricity and heating lead the way

Emissions from electricity production and heating under the region’s emissions trading system (ETS) dropped 24% in 2023, compared to the previous year, per the Commission.

Set up in 2005, the ETS is widely viewed as a key driver of the bloc’s decarbonisation. In 2023, it generated revenues of €43.6 billion in 2023 for climate action investments.

However, some sectors are still moving in the wrong direction. For instance, aviation emissions grew 9.5% last year as the sector continued to rebound in the wake of the pandemic.

More to be done

“The EU is leading the way in the clean transition, with another year of strong greenhouse gas emission reductions in 2023,” said Wopke Hoekstra, commissioner for climate action.

“As we head off soon to COP29, we once again demonstrate to our international partners that it is possible to take climate action and invest in growing our economy at the same time,” Hoekstra added. “Sadly, the report also shows that our work must continue, at home and abroad, as we are seeing the harm that climate change is causing our citizens.”

In a separate statement, Leena Ylä-Mononen, executive director of the European Environment Agency, said climate change impacts were “accelerating”, meaning the bloc needed to become more resilient to extreme weather while also slashing emissions.

In the second quarter of 2024, renewables accounted for 52% of all electricity generated in the EU, a 6 percentage point increase in a year. Nuclear generation was up slightly and comprised 24% of the mix, meaning clean sources made up 76% of the region’s total electrical output.

-via The Progress Playbook, November 1, 2024

#europe#eu#carbon emissions#renewables#clean energy#solar power#wind power#environment#climate news#climate action#climate hope#climate change#good news#hope#european union

860 notes

·

View notes

Text

The West’s self-deception over the crisis in Ukraine is of immense significance. Russia’s reaction to the coup in Ukraine should not have been a surprise to anyone. Moscow had warned for years that making Ukraine an anti-Russian bastion and a NATO member was an existential threat. Such warnings were repeated in 2008 when NATO promised future membership to Georgia and Ukraine.

The profound consequences of the coup in Ukraine were also largely missed, as it went largely unnoticed that Russia ended its efforts of integrating with Europe. The West largely deceived itself by dismissing Russian security concerns and framing Russian motivations rooted in anti-Western sentiments and desire to restore the Soviet Union. Even after the West rejected Gorbachev’s concept of a Common European Home in favour of NATO expansion, Russia still had ambitions for gradual integration with the West to create a Greater Europe. The Western-backed coup in Ukraine ended the illusions of any gradual integration with the West and subsequently led to the abandonment of the Greater Europe initiative.

Greater Europe was replaced with the Greater Eurasia Initiative in partnership with China, which entails reducing reliance on the West and reorganising Russia’s economic connectivity towards the East (Diesen, 2017). This represented a tectonic shift as Russia abandoned its 300-year-long Western-centric foreign policy, while China gained a strategic partner in its rivalry with the US. The failure to recognise Russia’s objectives resulted in the West embracing counter-productive policies. After Russia abandoned Greater Europe in favour of Greater Eurasia, sanctions merely intensified Russia’s economic decoupling from the West.

Russophobia: Propaganda in International Politics by Glenn Diesen.

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

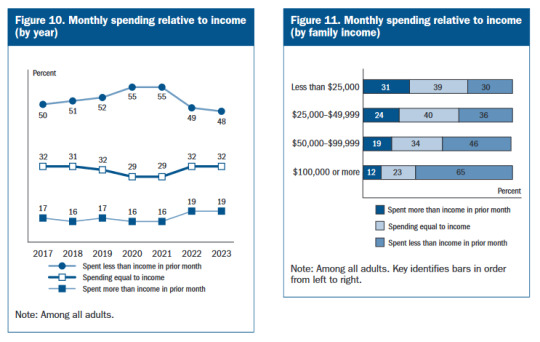

if we're like, showing graphs and stuff, this is the type that i think a lot of people on tumblr are thinking of when they think about the economy.

Only one third of people with family incomes below $50k spent less than their income each month. I would guess that a lot of people on tumblr who get aggro about this topic (and the vast majority of people on r/povertyfinance, who discuss this sort of thing a lot) fall into this earning category.

Real wage increases only matter if you got a raise (one third of workers got a raise last year, which means that 2/3rds didn't - included in the economic wellbeing report linked above). Whether or not rent is outpacing wages only matters if you're not going to be rent burdened (more than a third of renter households are cost burdened in every state and 12 million rental households spend more than half their income on rent). Employment rates lose a lot of meaning when you're working multiple jobs to make ends meet (the percentage of multiply employed workers was falling in the US from 1996 to the 2010s, when it plateaued, then it started rising slightly then collapsed in 2020 and has been rising steeply since then and it's too soon to tell if it's going to go back to the plateau or keep going up).

Four in ten adults in the US is carrying some level of medical debt (even people who are insured) and 60% of people with medical debt have cut back on food, clothes or household items; about 50% of people with medical debt have used up all their savings.

Tumblr is the broke people website and yeah, people who are working two jobs to afford $900 for one room and utilities in a three bedroom apartment are not going to feel great about the economy even if real wages are raising and inflation-adjusted rents are actually pretty stable. "The Rent is too Damn High" has been a meme for 14 years so, like, yeah. Even if it's pretty stable when adjusted for inflation it is stable and HIGH.

It's hard to feel good about the economy when you're spending the last few days of the pay period hoping nothing unexpected hits your account, and it's VERY frustrating to be told that the economy's doing well when you've had to start selling blood to buy groceries.

Sure, unemployment is low, that's neat. It's good that inflation has stabilized (it genuinely has; prices are not likely to fall back to pre-inflation rates and eventually you'll likely be paid enough to reach equilibrium, but a lot of people aren't there yet).

But, like, it costs eight thousand dollars a year out of pocket to keep my spouse alive. I'd guess that we've paid off about a third of the 40-ish thousands of dollars he's racked up since his heart attack. His medical debt is why I don't have a retirement plan beyond "I guess I'll die?" So talking about how good the economy is kind of feels like being chained in the bottom of a pit that is slowly filling with water while people on the surface talk about the fact that the rain is tapering off. Neat! That's good! But I can't really see it from where I'm standing.

Inflation really is getting better. My state just enacted a $20 minimum wage for fast food workers. The Biden administration has worked hard to reduce many kinds of healthcare costs. A lot of people have had significant portions of their student debt cancelled.

But a lot of people are still having trouble affording groceries and it doesn't seem helpful to say "your perception of the economy is decoupled from the reality of the economy" on the "can I get a few dollars for food today?" website.

560 notes

·

View notes

Text

🧵 WHAT YOU'RE NOT HEARING: The Chinese cannot replace the U.S. market. Without it, the Chinese economy collapses.

Here's why… China's entire economic miracle was built on ONE thing - being America's cheap manufacturing hub.

The "Chinese miracle" playbook was simple:

• Open markets to the West

• Offer dirt-cheap labor

• Ignore safety standards

• Let Western companies rake in profits

This worked for decades. But China forgot something crucial: others can do this too.

MASSIVE MISCALCULATION: Beijing thought the American leaders they made rich would protect them forever. They believed these corporate puppet masters would never let the US stand up to China.

WRONG. Along came Donald Trump, who owes them nothing.

The numbers don't lie

• US exports to China: $143.5B

• Chinese imports to US: $438.9B

They flood our markets while closing or restricting THEIR markets.

But Trump said: NO MORE

Meanwhile, countries like India, Vietnam, and Bangladesh are CELEBRATING. They're ready to take China's place, AND open their markets to the U.S. - and Trump's willing to deal.

HERE'S what the Enemedia WON'T tell you:

Chinese exporters are PANICKING

• Abandoning shipments mid-voyage

• Factory orders FROZEN

• Container volume DOWN 90%

And this is just the beginning. China can't replace the U.S. market that made it rich.

Reports flooding in:

• Factories shutting down

• Amazon canceling orders

• Stores closing

• Warehouses overflowing

The house of cards is falling. But the Enemedia gives you nothing but Chinese propaganda.

CRUCIAL FACT: America buys 3X more than Japan (China's next biggest customer).

Without us, they're FINISHED. And they were already on the ropes.

Will this affect US consumers? Sure, briefly. You might struggle to find cheap plastic junk for a few months.

But other countries will step up. And TRILLIONS in new investment are flowing into America, while countless factories LEAVE China.

Will this affect US consumers? Sure, briefly. You might struggle to find cheap plastic junk for a few months.

The bottom line: China picked a fight they can't win. While America adjusts, the CCP will face the consequences of their refusal to truly open their own markets, or to abandon aggression against their neighbors. Game over. The decoupling is under way.

Rod Martin, Founder and CEO Martin Capital

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Holy shit that’s terrifying

Is there anything that can be done??? It sounds like these people really should not be in premed

Or in college at all, if I’m being honest

Many of these classes are for older students so these people are 21-23 yrs old, calling their TAs "daddy" to their face/taking creep shots of them and slamming doors when you wont accept work thats 8 weeks late, outside of the much more serious instances of stalking and physical threats. In the past 6 months I've had two undergrads straight up say "I wish that fucking TA would just give me the answers" and another student telling me to fuck off while class was in session in front of other students. i try not to talk about this aspect of teaching to preserve some semblance of separation in my work life, but this quarter absolutely and holistically broke me.

the hardest part for me is i can still empathize. when i hear what these students go through in their classes its like...if you put people in insane situations, people will become insane too. When they have extreme expectations and are constantly critiqued, it creates a highly antagonistic relationship with learning and when you push people that hard they will often lash out at people more sympathetic/closest to them, since its the weakest "pressure overflow valve". Theres an added angle of many of them dont want to be there. There was some form of cultural or social pressure that pushed them to pursue this degree that they dont want because they feel like its the only economically viable option- which induces a lot of resentment and frustration.

another hypothesis i have is how socialization changed depending on what stage of development the pandemic hit for the person. i have to believe that these people do not understand what theyre doing. when we had the guy harassing a teacher for months on end eventually culminating in him saying he was going to go to her house and murder her, he genuinely did not understand why that was bad and not 'a super funny joke'. especially since outside of teaching, i will have people commenting "slather him in oil and put him on my table stat" or doing sex RP under videos where I'm literally just standing there doing a crafting demo- the whole concept of what is and isnt appropriate was never established for a large age demographic. its horrible, but i have to decouple the impact of those words from what i was taught to the impact of those words based on what they were never taught. to me its sickening and disturbing, but to them its just a flippant joke with no deeper meaning.

#theres literally so much more i could say about this but i dont want to release the dam of built up teaching feelings all in one go#like babygirl#dont even get me started on chatGPT or bullshit tutoring services

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decoupling of GDP growth from resource use, whether relative or absolute, is at best only temporary. Permanent decoupling (absolute or relative) is impossible for essential, non-substitutable resources because the efficiency gains are ultimately governed by physical limits.

[...]

Growth in GDP ultimately cannot plausibly be decoupled from growth in material and energy use, demonstrating categorically that GDP growth cannot be sustained indefinitely. It is therefore misleading to develop growth-oriented policy around the expectation that decoupling is possible.

Is Decoupling GDP Growth from Environmental Impact Possible?

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve found a lot of your posts about autonomy and infantilization helpful.

Do you have any advice for how to break out of self-infantilization, especially when you’ve been sheltered?

I grew up with strict parents and always thought I’d figure out how to be confident and independent when I went off to college.

But for a number of different reasons (including the pandemic) , I socially isolated myself and talked myself out of going out and trying new things, ex. I put off driving until I was 23, which limited where I could go.

And now for financial reasons I live with my parents while looking for a job.

I feel very immature for my age, like I don’t know how to start making decisions for myself without always asking for advice from someone else. I feel like I’m struggling with the transition to independence that most people go through from 15-18.

I can relate to some of this, and yeah, the aspect of financial and material dependence makes it difficult. One thing I would point out is that there's noting wrong with asking for advice, including from your parents (if you trust their advice!). Being autonomous doesn't mean figuring everything out on your own. Outside perspectives are good! But if you're asking ME for advice, I would suggest just being mindful of the difference, in your mindset, between asking for advice and asking for permission.

I think a lot of young people, even when they physically separate from their parents, get stuck in the "needing An Adult's Permission" mindset, and basically turn their boss/landlord/professor/doctor/therapist/partner into their substitute parent. And then if you do live with your parents as an adult (which I did! I still do, despite interludes of being elsewhere!), it's even easier to slip into the childhood mentality of submitting and needing permission. And it can take time and effort to break out of that mentality.

So I think my advice for keeping your advice-seeking from slipping into self-infantalization would be: -seek advice from multiple sources and use your own judgment to filter through it -seek advice from sources other than older people and authority figures. seek advice from people younger than you! -interact with people both older and younger than you as peers. tumblr is great for this! I never check anyone's ages, so I interact with 15 year olds and 50 year olds equally! I volunteer to be your middle-aged friend! -try to decouple money from decision-making in your mind. this is hard, because we live in a classist, capitalist, economically exploitative world. this was hard for me as a broke, dependent, unemployed young adult -- to break free of "I'm not a real adult yet because I don't have money" (an attitude actively encouraged by my family at the time) to "I don't have money to do most of the things I want, but of the things I can do, the things I don't actually need money for, I deserve to be in charge of." -if you don't have kids (you don't mention having any, so I'm assuming you don't), go make friends with people your age who have kids. offer to babysit, if that's something you're into. it's hard to think "I'm baby" when your peers have actual babies. That's all I can think of for now, but I mean, this is really hard. Life transitions are always hard, but we live in a world that makes this especially hard. And expensive. And that constantly lies to us about it. So just. Stay strong. Be yourself. All that good stuff. Oh, and one final thing: As you get older (which is inevitable, because time passes) do not forget everything you learned about ageism and youthlib. Older people have such selective memories and lack of empathy for their younger selves. To fight ageism, we have to align with our own younger selves.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The super-rich got that way through monopolies

Catch me in Miami! I'll be at Books and Books in Coral Gables on Jan 22 at 8PM.

Just in time for Davos, here's 'Taken, not earned: How monopolists drive the world’s power and wealth divide," a report from a coalition of international tax justice and anti-corporate activist groups:

https://www.balancedeconomy.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Davos-Taken-not-Earned-full-Report-2024-FINAL.pdf

The rise of monopolies over the past 40 years came about as the result of specific, deliberate policy choices. As the report documents, the wealthiest people in America funneled a fortune into neutering antitrust enforcement, through the "consumer welfare" doctrine.

This is an economic theory that equates monopolies with efficiency: "If everyone is buying the same things from the same store, that tells you the store is doing something right, not something criminal." 40 years ago, and ever since, the wealthy have funded think-tanks, university programs and even "continuing education" programs for federal judges to push this line:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/08/13/post-bork-era/#manne-down

They didn't do this for ideological reasons – they were chasing material goals. Monopolies produce vast profits, and those profits produce vast wealth. The rise and rise of the super rich cannot be decoupled from the rise and rise of monopolies.

If you're new to this, you might think that "monopoly" only refers to a sector in which there is only one seller. But that's not what economists mean when they talk about monopolies and monopolization: for them, a monopoly is a company with power. Economists who talk about monopolies mean companies that "can act independently without needing to consider the responses of competitors, customers, workers, or even governments."

One way to measure that power is through markups ("the difference between the selling price of goods or services and their cost"). Very large companies in concentrated industries have very high markups, and they're getting higher. From 2017-22, the 20 largest companies in the world had average markups of 50%. The 100 largest companies average 43%. The smallest half of companies get average markups of 25%.

Those markups rose steeply during the covid lockdowns – and so did the wealth of the billionaires who own them. Tech billionaires – Bezos, Brin and Page, Gates and Ballmer – all made their fortunes from monopolies. Warren Buffet is a proud monopolist who says "the single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power… if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business."

We are living in the age of the monopoly. In the 1930s, the top 0.1% of US companies accounted for less than half of America's GDP. Today, it's 90%. And it's accelerating, with global mergers climbing from 2,676 in 1985 to 62,000 in 2021.

Monopoly's cheerleaders claim that these numbers vindicate them. Monopolies are so efficient that everyone wants to create them. Those efficiencies can be seen in the markups monopolies can charge, and the profits they can make. If a monopoly has a 50% markup, that's just the "efficiency of scale."

But what is the actual shape of this "efficiency?" How is it manifest? The report's authors answer this with one word: power.

Monopolists have the power "to extract wealth from, to restrict the freedoms of, and to manipulate or steer the vastly larger numbers of losers." They establish themselves as gatekeepers and create chokepoints that they can use to raise prices paid by their customers and lower the payout to their suppliers:

https://chokepointcapitalism.com/

These chokepoints let monopolies usurp "one of the ultimate prerogatives of state power: taxation." Amazon sellers pay a 51% tax to sell on the platform. App Store suppliers pay a 30% tax on every dollar they make with their apps. That translates into higher costs. Consider a good that costs $10 to make: the bottom 50% of companies (by size) would charge $12.50 for that product on average. The largest companies would charge $15. Thus monopolies don't just make their owners richer – they make everyone else poorer, too.

This power to set prices is behind the greedflation (or, more politely, "seller's inflation"). The CEOs of the largest companies in the world keep getting on investor calls and bragging about this:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/03/11/price-over-volume/#pepsi-pricing-power

The food system is incredibly monopolistic. The Cargill family own the largest commodity trader in the world, which is how they built up a family fortune worth $43b. Cargill is one of the "ABCD" companies ("Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus") that control the world's food supply, and they tripled their profits during the lockdown.

Monopolies gouge everyone – even governments. Pfizer charged the NHS £18-22/shot for vaccines that cost £5/shot to make. They took the British government for £2bn – that's enough to pay last year's pay hike for NHS nurses, six times over,

But monopolies also abuse their suppliers, especially their employees. All over the world, competition authorities are uncovering "wage fixing" and "no poaching" agreements among large firms, who collude to put a cap on what workers in their sector can earn. Unions report workers having their pay determined by algorithms. Bosses lock employees in with noncompetes and huge repayment bills for "training":

https://pluralistic.net/2022/08/04/its-a-trap/#a-little-on-the-nose

Monopolies corrupt our governments. Companies with huge markups can spend some of that money on lobbying. The 20 largest companies in the world spend more than €155m/year lobbying in the US and alone, not counting the money they spend on industry associations and other cutouts that lobby on their behalf. Big Tech leads the pack on lobbying, accounting for 82% of EU lobbying spending and 58% of US lobbying.

One key monopoly lobbying priority is blocking climate action, from Apple lobbying against right-to-repair, which creates vast mountains of e-waste, to energy monopolist lobbying against renewables. And energy companies are getting more monopolistic, with Exxonmobil spending $65b to buy Pioneer and Chevron spending $60b to buy Hess. Many of the world's richest people are fossil fuel monopolists, like Charles and Julia Koch, the 18th and 19th richest people on the Forbes list. They spend fortunes on climate denial.

When people talk about the climate impact of billionaires, they tend to focus on the carbon footprints of their mansions and private jets, but the true environmental cost of the ultra rich comes from the anti-renewables, pro-emissions lobbying they buy with their monopoly winnings.

The good news is that the tide is turning on monopolies. A coalition of "businesses, workers, farmers, consumers and other civil society groups" have created a "remarkably successful anti-monopoly movement." The past three years saw more regulatory action on corporate mergers, price-gouging, predatory pricing, labor abuses and other evils of monopoly than we got in the past 40 years.

The business press – cheerleaders for monopoly – keep running editorials claiming that enforcers like Lina Khan are getting nothing done. Sure, WSJ, Khan's getting nothing done – that's why you ran 80 editorial about her:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/14/making-good-trouble/#the-peoples-champion

(Khan's winning like crazy. Just last month she killed four megamergers:)

https://www.thesling.org/the-ftc-just-blocked-four-mergers-in-a-month-heres-how-its-latest-win-fits-into-the-broader-campaign-to-revive-antitrust/

The EU and UK are taking actions that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. Canada is finally set to get a real competition law, with the Trudeau government promising to add an "abuse of dominance" rule to Canada's antitrust system.

Even more exciting are the moves in the global south. In South Africa, "competition law contains some of the most progressive ideas of all":

It actively seeks to create greater economic participation, particularly for ‘historically disadvantaged persons’ as part of its public interest considerations in merger decisions.

Balzac wrote, "Behind every great fortune there is a crime." Chances are, the rapsheet includes an antitrust violation. Getting rid of monopolies won't get rid of all the billionaires, but it'll certainly get rid of a hell of a lot of them.

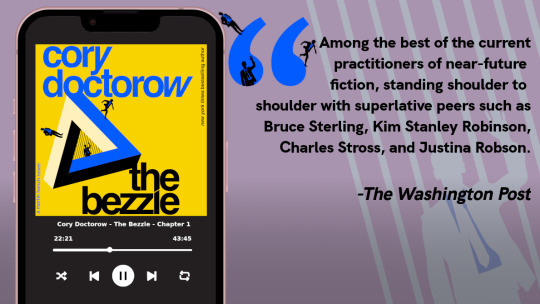

I'm Kickstarting the audiobook for The Bezzle, the sequel to Red Team Blues, narrated by @wilwheaton! You can pre-order the audiobook and ebook, DRM free, as well as the hardcover, signed or unsigned. There's also bundles with Red Team Blues in ebook, audio or paperback.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/01/17/monopolies-produce-billionaires/#inequality-corruption-climate-poverty-sweatshops

#billionaires#wef#climate#monopoly#world economic forum#competition#antitrust#consumer welfare#inequality#corruption#davos#guillotine watch

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from this New York Times story:

Last year was the hottest on record, and global average temperatures passed the benchmark of 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial times for the first time. Simultaneously, the growth rate of the world’s energy demand rose sharply, nearly doubling over the previous 10-year average.

As it turns out, the record heat and rapidly rising energy demand were closely connected, according to findings from a new report from the International Energy Agency.

That’s because hotter weather led to increased use of cooling technologies like air-conditioning. Electricity-hungry appliances put a strain on the grid, and many utilities met the added demand by burning coal and natural gas.

All of this had the makings of a troubling feedback loop: A hotter world required more energy to cool down homes and offices, and what was readily available was fossil-fuel energy, which led to more planet-warming emissions. This dynamic is exactly what many countries are hoping to halt through the development of renewable energy and the construction of nuclear power plants.

Put another way, the I.E.A. estimated that if 2024’s extreme weather hadn’t happened — that is, if weather was exactly the same in 2024 as in 2023 — the global increase in carbon emissions for the year would have been cut in half.

It’s not all bad news: Increasingly, the global economy is growing faster than carbon emissions. “If we want to find the silver lining, we see that there is a continuous decoupling of economic growth from emissions growth,” said Fatih Birol, the executive director of the agency.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

observations on fundraiser dynamical system

I think anyone who has used regularly used Tumblr (or Bluesky or similar networks) in the past few years has seen hundreds, if not thousands, of fundraisers from people in extremely desperate situations - mainly, people trying to survive the ongoing, extraordinary genocide in Gaza, but also people in countries like South Sudan which are suffering in similar ways.

a general observation with fundraisers is that no matter how good the cause, the dynamic ends up being that hammering on the "social media call to action" button saturates fast, and people rapidly develop the habit of tuning out fundraisers - both for epistemic reasons (it is difficult to tell who is genuine, and although tumblr users like 90-ghost have been doing admirable and thankless work verifying people, ultimately you have to decide where the chain of trust should terminate) and emotional ones (broadly speaking, someone goes on social media for some purpose which is not to see genocide victims asking for help).

the human brain is a very powerful pattern-detector, and it is quickly able to identify 'this looks like another Gaza fundraiser, I know what I have seen here and I've made up my mind already about whether to donate money'.

like other forms of advertising, fundraisers 'succeed' by two means: convincing people who weren't going to donate money to donate money instead of spending it on something else (positive-sum), and winning out over other fundraisers (finite-sum).

this all leads to a very bad feedback loop where fundraisers must push harder and harder to get over that wall of indifference: posting shocking pictures of injured or dying children, bait-and-switch tactics with social media fluff like polls, etc. etc.; it is an optimisation process that seizes on whatever works. this is equally true for genuine fundraisers and scams: they both have the exact same buttons available to them. nobody wants to post pictures of their starving children to strangers on a blogging website speaking a foreign language, but if it might just get them another month, they will. on the flipside, users more and more aggressively tune their instincts for filtering them out, in order to preserve whatever activity they came to the website for.

and we can morally decry this, it should not be this way, but this is the dynamics of the situation as I observe it.

there is also, as far as the specific situation in Gaza is concerned, a problem where the supply (of food, medicine, passage out of Gaza) is incredibly limited by non-monetary factors - namely how much aid Israel (and to an extent, Egypt) decide to let through the border on any given day. in economic terms, this makes it highly (but not totally) inelastic. with finite supply, the price will grow to whatever people can afford. if all the food that gets in is always eaten, paying one family directly to buy food means that it doesn't go to another family. that said, it's not totally inelastic: if money can be made moving food into Gaza, people will do it as much as they can. and in practice I don't think the amount of money raised from social media fundraisers is so large as to drastically affect the prices in Gaza.

theoretically, problems like these are supposed to be solved by organisations such as charities and government orgs, which can act as a mediating layer: you pay your taxes and put aside whatever amount of money you see fit to good causes, and someone whose actual job it is does the unpleasant work of figuring out who needs it most and helping those they can. however, I think anyone who's worked in the NGO space can say what a fucking mess that all is: under various dynamics (supply of willing volunteers vs. rate of burnout, ability to appeal to sources of funding, ability to sustain a narrative in their members, charisma of central figures) orgs survive or not largely decoupled from whether they accomplish their ostensible mission. as for taxes, they are more likely to be spent killing people in Gaza than saving them.

and meanwhile, of course, there are problems like 'getting sick person to functioning hospital that hasn't been blown up' that NGOs presently can't solve. in a sense, the infrastructure that has sprung up on here - spreadsheets of fundraisers, people verifying them - is something like a proto-charity.

those caveats acknowledged, I believe there is an advantage for donating to e.g. mutual aid projects over individuals, at least as far as food. at least theoretically, an organisation is better able to make links with suppliers outside of gaza and take advantage of bulk orders.

still, whatever scale they operate on, fundraisers alone cannot save more than a few people in Gaza. they must be part of a broader strategy, also involving other political means to undermine the capacity of the state of Israel to carry on its genocide and shift the geopolitical situation. but goddamn do I not have any fucking clue what a viable strategy is.

just introspecting my own habits, I put aside a certain amount of money every month to go to specific people and orgs I've chosen to support long-term, and occasionally and largely randomly I am moved to donate some extra to someone who appears in front of me (which means a fundraiser worked on me).

as far as using my blog, on the occasions I've reblogged fundraisers or shared asks, they've gotten almost no engagement, and I have come to think this is not really the function of my personal blog - or at least if I do, I need to do it sparingly, in balance with the original content that hopefully interests people in my writing in the first place. but i'm not sure if this is an excuse or rationalisation for the psychological factors discussed above. on the occasions I've written posts in my own words to support a fundraiser, primarily on behalf of refugee Peter Kats ( @queercommunitysblog ) in South Sudan, they've spread further and managed to bring some money his way. however, I am neither qualified to verify whose fundraiser is real, nor do I have the energy to be a social media manager.

I observe people having different habits with respect to how they interact with promoting fundraisers. some people share a batch every day. some people almost never post fundraisers, but do occasionally, based on some factor of mood. some people have a specific person they know personally whose cause they champion; others do it reactively in response to asks. I suppose I have currently ended up with a policy that's something like 'share mutual aid projects' and occasionally writing posts like this one where I encourage you to decide on your own strategy for 'what the fuck do you do when your country is supporting a genocide'. I don't think this is particularly optimal. but I don't think it helps to be dishonest.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

In macro-economics it's generally always a good idea to remember that production is and has been completely decoupled from consumption.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Clay Shirky

Published: Apr 29, 2025S

Since ChatGPT launched in late 2022, students have been among its most avid adopters. When the rapid growth in users stalled in the late spring of ’23, it briefly looked like the AI bubble might be popping, but growth resumed that September; the cause of the decline was simply summer break. Even as other kinds of organizations struggle to use a tool that can be strikingly powerful and surprisingly inept in turn, AI’s utility to students asked to produce 1,500 words on Hamlet or the Great Leap Forward was immediately obvious, and is the source of the current campaigns by OpenAI and others to offer student discounts, as a form of customer acquisition.

Every year, 15 million or so undergraduates in the United States produce papers and exams running to billions of words. While the output of any given course is student assignments — papers, exams, research projects, and so on — the product of that course is student experience. “Learning results from what the student does and thinks,” as the great educational theorist Herbert Simon once noted, “and only as a result of what the student does and thinks.” The assignment itself is a MacGuffin, with the shelf life of sour cream and an economic value that rounds to zero dollars. It is valuable only as a way to compel student effort and thought.

The utility of written assignments relies on two assumptions: The first is that to write about something, the student has to understand the subject and organize their thoughts. The second is that grading student writing amounts to assessing the effort and thought that went into it. At the end of 2022, the logic of this proposition — never ironclad — began to fall apart completely. The writing a student produces and the experience they have can now be decoupled as easily as typing a prompt, which means that grading student writing might now be unrelated to assessing what the student has learned to comprehend or express.

Generative AI can be useful for learning. These tools are good at creating explanations for difficult concepts, practice quizzes, study guides, and so on. Students can write a paper and ask for feedback on diction, or see what a rewrite at various reading levels looks like, or request a summary to check if their meaning is clear. Engaged uses have been visible since ChatGPT launched, side by side with the lazy ones. But the fact that AI might help students learn is no guarantee it will help them learn.

After observing that student action and thought is the only possible source of learning, Simon concluded, “The teacher can advance learning only by influencing the student to learn.” Faced with generative AI in our classrooms, the obvious response for us is to influence students to adopt the helpful uses of AI while persuading them to avoid the harmful ones. Our problem is that we don’t know how to do that.I

am an administrator at New York University, responsible for helping faculty adapt to digital tools. Since the arrival of generative AI, I have spent much of the last two years talking with professors and students to try to understand what is going on in their classrooms. In those conversations, faculty have been variously vexed, curious, angry, or excited about AI, but as last year was winding down, for the first time one of the frequently expressed emotions was sadness. This came from faculty who were, by their account, adopting the strategies my colleagues and I have recommended: emphasizing the connection between effort and learning, responding to AI-generated work by offering a second chance rather than simply grading down, and so on. Those faculty were telling us our recommended strategies were not working as well as we’d hoped, and they were saying it with real distress.

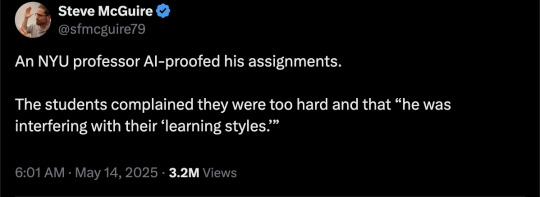

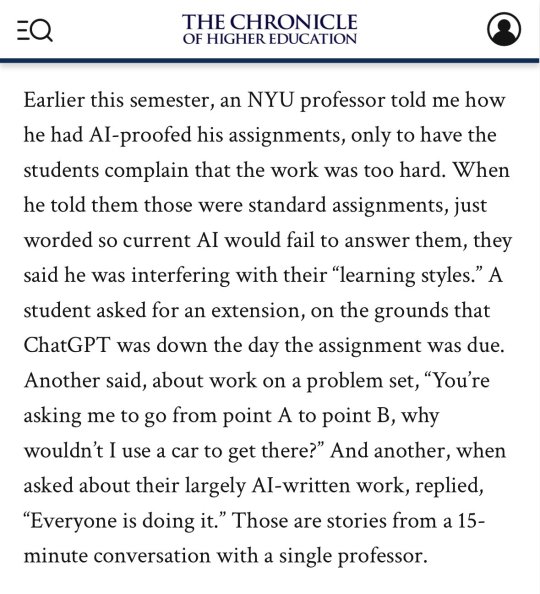

Earlier this semester, an NYU professor told me how he had AI-proofed his assignments, only to have the students complain that the work was too hard. When he told them those were standard assignments, just worded so current AI would fail to answer them, they said he was interfering with their “learning styles.” A student asked for an extension, on the grounds that ChatGPT was down the day the assignment was due. Another said, about work on a problem set, “You’re asking me to go from point A to point B, why wouldn’t I use a car to get there?” And another, when asked about their largely AI-written work, replied, “Everyone is doing it.” Those are stories from a 15-minute conversation with a single professor.

We are also hearing a growing sense of sadness from our students about AI use. One of my colleagues reports students being “deeply conflicted” about AI use, originally adopting it as an aid to studying but persisting with a mix of justification and unease. Some observations she’s collected:

“I’ve become lazier. AI makes reading easier, but it slowly causes my brain to lose the ability to think critically or understand every word.”

“I feel like I rely too much on AI, and it has taken creativity away from me.”

On using AI summaries: “Sometimes I don’t even understand what the text is trying to tell me. Sometimes it’s too much text in a short period of time, and sometimes I’m just not interested in the text.”

“Yeah, it’s helpful, but I’m scared that someday we’ll prefer to read only AI summaries rather than our own, and we’ll become very dependent on AI.”

Much of what’s driving student adoption is anxiety. In addition to the ordinary worries about academic performance, students feel time pressure from jobs, internships, or extracurriculars, and anxiety about GPA and transcripts for employers. It is difficult to say, “Here is a tool that can basically complete assignments for you, thus reducing anxiety and saving you 10 hours of work without eviscerating your GPA. By the way, don’t use it that way.” But for assignments to be meaningful, that sort of student self-restraint is critical.

Self-restraint is also, on present evidence, not universally distributed. Last November, a Reddit post appeared in r/nyu, under the heading “Can’t stop using Chat GPT on HW.” (The poster’s history is consistent with their being an NYU undergraduate as claimed.) The post read:

I literally can’t even go 10 seconds without using Chat when I am doing my assignments. I hate what I have become because I know I am learning NOTHING, but I am too far behind now to get by without using it. I need help, my motivation is gone. I am a senior and I am going to graduate with no retained knowledge from my major.

Given these and many similar observations in the last several months, I’ve realized many of us working on AI in the classroom have made a collective mistake, believing that lazy and engaged uses lie on a spectrum, and that moving our students toward engaged uses would also move them away from the lazy ones.

Faculty and students have been telling me that this is not true, or at least not true enough. Instead of a spectrum, uses of AI are independent options. A student can take an engaged approach to one assignment, a lazy approach on another, and a mix of engaged and lazy on a third. Good uses of AI do not automatically dissuade students from also adopting bad ones; an instructor can introduce AI for essay feedback or test prep without that stopping their student from also using it to write most of their assignments.

Our problem is that we have two problems. One is figuring out how to encourage our students to adopt creative and helpful uses of AI. The other is figuring out how to discourage them from adopting lazy and harmful uses. Those are both important, but the second one is harder.I

t is easy to explain to students that offloading an assignment to ChatGPT creates no more benefit for their intellect than moving a barbell with a forklift does for their strength. We have been alert to this issue since late 2022, and students have consistently reported understanding that some uses of AI are harmful. Yet forgoing easy shortcuts has proven to be as difficult as following a workout routine, and for the same reason: The human mind is incredibly adept at rationalizing pleasurable but unhelpful behavior.

Using these tools can certainly make it feel like you are learning. In her explanatory video “AI Can Do Your Homework. Now What?” the documentarian Joss Fong describes it this way:

Education researchers have this term “desirable difficulties,” which describes this kind of effortful participation that really works but also kind of hurts. And the risk with AI is that we might not preserve that effort, especially because we already tend to misinterpret a little bit of struggling as a signal that we’re not learning.

This preference for the feeling of fluency over desirable difficulties was identified long before generative AI. It’s why students regularly report they learn more from well-delivered lectures than from active learning, even though we know from many studies that the opposite is true. One recent paper was evocatively titled “Measuring Active Learning Versus the Feeling of Learning.” Another concludes that instructor fluency increases perceptions of learning without increasing actual learning.

This is a version of the debate we had when electronic calculators first became widely available in the 1970s. Though many people present calculator use as unproblematic, K-12 teachers still ban them when students are learning arithmetic. One study suggests that students use calculators as a way of circumventing the need to understand a mathematics problem (i.e., the same thing you and I use them for). In another experiment, when using a calculator programmed to “lie,” four in 10 students simply accepted the result that a woman born in 1945 was 114 in 1994. Johns Hopkins students with heavy calculator use in K-12 had worse math grades in college, and many claims about the positive effect of calculators take improved test scores as evidence, which is like concluding that someone can run faster if you give them a car. Calculators obviously have their uses, but we should not pretend that overreliance on them does not damage number sense, as everyone who has ever typed 7 x 8 into a calculator intuitively understands.

Studies of cognitive bias with AI use are starting to show similar patterns. A 2024 study with the blunt title “Generative AI Can Harm Learning” found that “access to GPT-4 significantly improves performance … However, we additionally find that when access is subsequently taken away, students actually perform worse than those who never had access.” Another found that students who have access to a large language model overestimate how much they have learned. A 2025 study from Carnegie Mellon University and Microsoft Research concludes that higher confidence in gen AI is associated with less critical thinking. As with calculators, there will be many tasks where automation is more important than user comprehension, but for student work, a tool that improves the output but degrades the experience is a bad tradeoff.I

n 1980 the philosopher John Searle, writing about AI debates at the time, proposed a thought experiment called “The Chinese Room.” Searle imagined an English speaker with no knowledge of the Chinese language sitting in a room with an elaborate set of instructions, in English, for looking up one set of Chinese characters and finding a second set associated with the first. When a piece of paper with words in Chinese written on it slides under the door, the room’s occupant looks it up, draws the corresponding characters on another piece of paper, and slides that back. Unbeknownst to the room’s occupant, Chinese speakers on the other side of the door are slipping questions into the room, and the pieces of paper that slide back out are answers in perfect Chinese. With this imaginary setup, Searle asked whether the room’s occupant actually knows how to read and write Chinese. His answer was an unequivocally no.

When Searle proposed that thought experiment, no working AI could approximate that behavior; the paper was written to highlight the theoretical difference between acting with intent versus merely following instructions. Now it has become just another use of actually existing artificial intelligence, one that can destroy a student’s education.

The recent case of William A., as he was known in court documents, illustrates the threat. William was a student in Tennessee’s Clarksville-Montgomery County School system who struggled to learn to read. (He would eventually be diagnosed with dyslexia.) As is required under the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, William was given an individualized educational plan by the school system, designed to provide a “free appropriate public education” that takes a student’s disabilities into account. As William progressed through school, his educational plan was adjusted, allowing him additional time plus permission to use technology to complete his assignments. He graduated in 2024 with a 3.4 GPA and an inability to read. He could not even spell his own name.

To complete written assignments, as described in the court proceedings, “William would first dictate his topic into a document using speech-to-text software”:

He then would paste the written words into an AI software like ChatGPT. Next, the AI software would generate a paper on that topic, which William would paste back into his own document. Finally, William would run that paper through another software program like Grammarly, so that it reflected an appropriate writing style.

This process is recognizably a practical version of the Chinese Room for translating between speaking and writing. That is how a kid can get through high school with a B+ average and near-total illiteracy.

A local court found that the school system had violated the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, and ordered it to provide William with hundreds of hours of compensatory tutoring. The county appealed, maintaining that since William could follow instructions to produce the requested output, he’d been given an acceptable substitute for knowing how to read and write. On February 3, an appellate judge handed down a decision affirming the original judgement: William’s schools failed him by concentrating on whether he had completed his assignments, rather than whether he’d learned from them.

Searle took it as axiomatic that the occupant of the Chinese Room could neither read nor write Chinese; following instructions did not substitute for comprehension. The appellate-court judge similarly ruled that William A. had not learned to read or write English: Cutting and pasting from ChatGPT did not substitute for literacy. And what I and many of my colleagues worry is that we are allowing our students to build custom Chinese Rooms for themselves, one assignment at a time.

[ Via: https://archive.today/OgKaY ]

==

These are the students who want taxpayers to pay for their student debt.

#Steve McGuire#higher education#artificial intelligence#AI#academic standards#Chinese Room#literacy#corruption of education#NYU#New York University#religion is a mental illness

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry if this is a dumb question, but could you clarify how tariffs work? So, if Trump imposes a tariff on China, does that mean that if someone from the US purchases something from China, they pay an additional fee? And if China has tariffs on American products, those consumers pay a fee when they buy something from the US? I'm hesitant to Google it lest I find nothing but left-wing hysteria.

This is going to be very quick and dirty and it's not going to take into account certain things, but to highlight tariffs I think it will suffice. Okay, so say China wants to export smart phones to the United States. Shipping one cell phone from China to the US has one price, let's say it's $10. To ship 10,000 phone to the US then costs $100,000, which means those phones need to be priced high enough that selling most of them brings in much more than 100k to make a profit. That's with no tariffs. But if a 100% tariff is put on smart phones from China, the cost to ship each phone now doubled to $20, which means it costs $200,000 to ship 10,000 of them, which means the price those phones are sold at gets increased for the US consumer. But, because that money comes from a tariff, that extra $100,000 goes into the government's pocket.

So that's bad, right? Tariffs just mess up our economy even more? Not so fast.

Permanent tariffs with no other change will be bad long term. But Trump isn't interested in long term tariffs with no other change. He has two potential goals, with the first being what's happening now and the second what he would like to happen long term.

The first is he's using tariffs to bring other countries to the negotiating table to end their decades long tariffs against us as well as negotiate trade deals favorable to the US and bring manufacturing back to this country. Since the US is the largest economy in the world, and it's a deficit economy (which means it buys more than it sells), and most other countries in Europe are surplus countries (they sell more than they buy, mostly to us) this gives Trump a lot of negotiating power. It means these countries need us more than we need them. We already see this working since 75 countries have said they want to negotiate with Trump since he put his tariffs into effect, with some offering to get rid of all tariffs against the US.

The one exception to this seems to be China, which Trump wants to defeat economically with tariffs. Which I think he can do, since the much vaunted Chinese economy is mostly a paper tiger. China can't afford a long trade war with the US. It depends on the rest of the world pouring money into it to stay solvent, and part of Trump's negotiations with the countries surrounding it, like Japan and South Korea, will no doubt have provisions for decoupling them from the Chinese economy at least somewhat and coupling them more strongly to the US Economy.

The second is he wants to repeal the income tax and replace that revenue with tariff revenue, with the idea that the extra money in people's pockets from no longer stealing 40% of their paychecks will offset the rise in prices from the tariffs. This probably won't happen, since the income tax was put into the constitution via an amendment and it would take 2/3rds of congress voting to repeal it, or a constitutional convention of the states, neither of which are likely at all. There's a possibility that this isn't even a real goal of his, just something he's said publicly so the rest of the world thinks he's serious about long term tariffs.

16 notes

·

View notes