#and write incredibly analyses of it apparently

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I know Dc has always proclaimed Tim Drake as the best detective and the smartest Robin and he is. By conventional measurements he is the best detective and he’s very smart but I wish they would acknowledge that each Robin is incredibly smart in their own way.

Dick Grayson is a master manipulator. He’s a genius when it comes to reading people and honestly whenever I need to write young him in fanfiction I literally just do Missy for Sheldon.

He’s smart. Book smart, but also people smart and people need to acknowledge this more it pains me to see DC forget this in exchange for a far more fannon. Far less complex version of him. He’s smart! Let him be smart.

Jason Todd is also book smart, though less mathematics and science and more classical literature. That man knows his way around the collections of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and that’s not even mentioning his street smarts.

He may not be the best conventional detective but he knows how to distinguish different gangs and their territories. He knows where dealers like to run their shops and he knows when a crime is too messy to have been caused by any of the rogues in the area.

Stephanie of course is a mix of the two. She’s good with people and she’s good on the streets but she’s also for very obvious reasons amazing at puzzles. Any tricky, seemingly impossible sort of quiz she’s got it, which is especially useful when the criminals of Gotham enjoy sending their hero’s on a wild goose chase.

She’s incredibly good at seeing through riddles and word vomit and she’s an amazing detective in her own right which should be used more.

Cass has been proven to be a great detective on so many occasions and of course do we even have to mention how adept she is at reading body language?

Her knowledge of combat is obviously unmatched and I’d love to see comics take this and apply it to her detective skills. How cool would it be for her to analyse a corpse and tell the fighting style of the assailant just by noting where on the body the strikes landed?

Realistic? No, but this is comics. Let me have my fun.

Damian was obviously trained in a dozen forms of martial arts, but he’s obviously knowledgeable about other things. The LoA are eco terrorists. You’re telling me that kid doesn’t know plants?

And that’s not even mentioning his knowledge of weapons and how he knows the ins and outs of organised crimes after living surrounded by it for a decade.

Plus his undercover skills.

Duke is new to me so I don’t know as much about him, but like Jason and Steph he grew up in the narrows and was part of gang, plus he apparently survived the riddler at like age 7 (pls don’t quote me on this I know practically nothing about zero year). So I can assume he’s incredibly intelligent. Street smarts! Also his powers let him look into the past which as evidenced in WFA can be used to help solve crimes.

Like I don’t want them to be conventional detectives. Let Tim be the Sherlock Holmes of the family. He’s already shown to be very observant.

I want to see more of the batfam using their own unique skill sets to solve crimes. They’re all good detectives they just have different ways of solving crimes.

Pls Dc, they would look so cool. If WFA can do it so can you! 😭😭

#batfam#dc#dc comics#batman#dick grayson#jason todd#stephanie brown#cassandra cain#damian wayne#duke thomas#they’re all so smart#but DC barely acknowledges that#if you have any evidence of them doing so however please send it to me#I’m actually begging you I’m so starved for content of my favs getting to show of their big brains#Robin#look they’re all autistic let them blab about their special interest

313 notes

·

View notes

Text

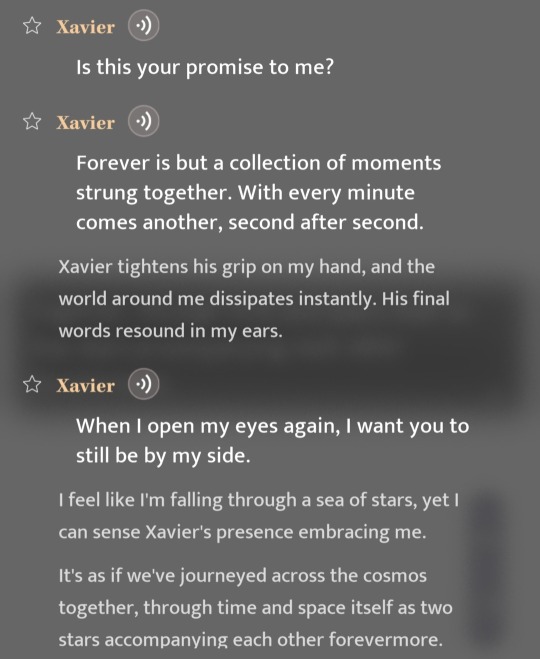

"floral blessings" ; a braindump from yours truly because this card is absofuckinglutely my most favorite xavier card on the face of the planet and i am. going. to talk about it <3

like with all my 5* card "analyses" (but also more like a wordvomit really 😭) this will contain spoilers for: (a) this card itself, (b) the lightseeker myth, (c) the lumiere myth, (d) anecdotes, main story, and world underneath !

[ this is also very long............ you have been warned 🤲 ]

first of all...... MY GOD...... FHSNNFBSJFJSJFK YELLING SCREAMING THROWING UP IM NEVER GETTING OVER THE KINDLED CARD FOR THIS BECAUSE. BECAUSE HELLOOOO??? HELLOOOO???

anyway..................

timeline-wise, the card pretty much implies a very solid relationship between the two, so while i don't know where i'd place it between 21 days and no restraint, it's definitely still after 21 days! but with that said, rather than more focus on their individual development like in no restraint, this one seems to focus more on their relationship as a whole, i think?

overall this braindump won't be as organized as what i wrote for no restraint (i think...) because my brain is still so completely absolutely mush over this card, but i needed to write SOMETHING or i'd explode to smithereens 😭 so nevertheless...!!!! i'll section off a couple scenes so if you want an outline, it'd be something like:

[1] general setup (an overview of parallels); [2] "reunion" (parallels and relationship development); [3] xavier's forwardness (the courtyard meetings, lessons, giving of the mask); [4] day of the festival; [5] the wish

but bear with me;;; there is SO MUCH that goes on here, and i really wish i had the patience and coherency to point out every little thing because holy shit 😭

firstly though, and i just found this really cool, but apparently the flower goddess festival is (was) an actual thing!

from what i've found (and correct me in i'm wrong) it's apparently a very ancient festival that's not widely celebrated these days, so it's not super popular or well-known, but it has many names such as: "Flower Goddess Festival (花神节 huāshén jié)" "Hundred Flowers’ Birthday (百花生日 bǎihuā shēngrì)" and "Flower Goddess’ Birthday (花神生日 huāshén shēngrì)" !!! i couldn't find much information about it though, but it seems that what was in the card such as the flower cakes and the dance really were actually part of the festival~ and i've also seen people say that xavier and mc's outfits feel to be from the tang dynasty, which a lot of people speculate is the time period that this festival originated!

BUT, MOVING ON...

i. general setup — an overview of parallels

i think honestly what's most interesting to me here is how much the overall card mirrors xavier's lightseeker myth so incredibly well. with all of xavier's cards, and how he's grown as a person and how their relationship has developed overall... so much of all of that ties to who he was as a lightseeker, to who he was as the prince of philos. in fact, it goes without saying that lumiere's myth story itself is so bound to the lightseeker myth. because, and i've said this so often and repeat myself a lot with it, lumiere is a direct reflection of the princely persona xavier has grown up with. that the reason he's always been so averse to who he becomes as lumiere is because he essentially channels prince xavier, someone who he's never thought to be truly him, someone who he's been wanting to push aside and no longer be. (i talk about it in my lumiere myth braindumps and touch on it in my no restraint braindump!)

and there's something about that reflection that transfers here, too, because there are two things that all three situations have in common: (1) a position of importance, and (2) a duty to do or fulfil something.

of the prince of philos and heir to the throne, of lumiere as the strongest hunter expected to protect the citizens, of the young master—usually the son of a wealthy family, however, in this case xavier claims he was "adopted" due to his calligraphy skills—with the task of seeing the festival through and teaching the flower goddesses calligraphy.

yet, at the same time, there's something different about the way xavier assumes this role of the "young master":

he's able to say no.

the role is lighter, likely because it's not a true role and, like mc as a flower goddess, he knows that it's temporary—but the way that their first meeting in the courtyard can remind you so much of prince xavier is almost jarring.

it's reminiscent of the very first time mc sees him with his bodyguards, in our most favorite anecdote "when shooting stars fall":

"They aren't clad in all black as one would expect, and they keep a respectable distance away from Xavier. Still, these people exude an air of oppression. Xavier, with his bag, is at the center of their group. It seems he's used to being stared at. The only difference is that rather than being his usual expressionless self, he appears slightly upset."

lt's reminiscent of that time they staged a spar, only for the royal messenger and his guards to interrupt it:

"The royal decree he brought today was related to the future of Philos ... Xavier was taken away by the Royal Messenger. Our duel ended with no clear winner, and the crowd quickly left."

and you can see how his progression grows, from prince xavier, to lumiere, to this role he plays as the young master—if as the prince of philos he had no choice but to follow the path laid out for him until he had enough of it, as lumiere he was more free to choose who he saved and when he saved them. now, as the young master, he's able to say no, sir, something urgent came up. he's able to say right now, i have something that i want to do first.

which, also interestingly, but in the more 'passive' role he played as part of the special task force, he wasn't quite one to say "no" either—though he kept a low and nonchalant profile, he's never outright refuted anyone, even if he might disagree, such as the party gathering or whatnot.

(also, slight segue, but it's notable that he's likely grown into a habit of a little selfishness due to what appears to be some kind of aversion to "serving the people". i do talk a little bit about that here—but it's the fact that (a) all he really cares about is mc, and (b) he likely still doesn't want to fall back into his patterns as prince xavier where he felt chained to think of the people more than the woman he loves. it does bring a little bit of question to his morality, but we know that mc has very much been something like his moral compass throughout.)

but, more than just the ability to say what he thinks and say no to certain things he doesn't put as a priority... he also feels light enough to goof around a little. dozing off/doodling during class, cheekily vying for mc's attention without concern about showing "favor"... something about xavier in this little persona he's taken on is an air of confidence. this was a kind of confidence you didn't see from him as the prince, as lumiere, even as the task force member. and it's not the confidence in his abilities, which has always been there—

it's the confidence in himself.

it takes a certain level of sureness to be able to do things on your own terms, or to be able to voice the fact that you want to.

i believe that throughout the parallels strewn throughout this card with how the setup is, it's this confidence that shines through and really makes things different.

because this time, xavier is different.

he's growing as a person.

ii. the "reunion"

this part of the card had me gasping out loud, i kid you not 😭😭😭 because the parallels really the fuck parallel in here 😭

"The Chen residence is far away. And I can't exactly leave as I'm one of the Flower Goddesses. So, I had to let Xavier investigate himself."

"He said he'd be back after four days. Why isn't he here ... Worried, I sit on the grass and gaze at the night sky. I'm barely in the mood to appreciate the fragrant blooms above."

first of all, the setting very much feels like the meteor shower scenario in "when shooting stars fall", but also...

"Xavier would always leave me like this. At times he joined the expedition team. Other times he was returning to the palace with the Royal Messenger. I'd always ask when he could return. He always returned within the timeframe given to me.Before the Prince entered the Forest, everyone was praying for his safety. At that time, Xavier whispered into my ear... 'Seven days.'"

"He's always lied, again and again and again and again. He said hope would follow when spring arrived. He said he'd take me to the new planet he discovered.He said he didn't want to be King but also refused to let me stand by another's side. He said he'd return when I miss him. He said when I become the Queen of Philos, he'd be my knight. The song he made up is now a reality. Yet as thousands cheer my name, he abandons me... At that moment, a spaceship soars across the sky like a shooting star, disappearing into the night. My footsteps echo in this empty room. No one will be by my side. My star has left me. And this time... he will not return home."

everyone's favorite scene from the lightseeker myth.

while at the same time...

"For some reason, seeing Xavier quietly admiring the nebula, I suddenly feel a wave of panic and instinctively reach out to grab his hand."

^ that's from "shining traces", but only one out of the many examples wherein mc feels as it xavier is someone she could lose at any second—not particularly because she doesn't trust him, but because there's a nagging feeling in her chest that they could be separated for longer than either of them would have hoped to be. after all, it's happened before already, she just doesn't know it. but whatever it was that happened in her previous lives, i've no doubt that the anxiety from back then had likely transferred over anyway.

and this is what this reunion feels like.

a sense of discomfort around his absence, that nagging "what if" he doesn't come back.

but it doesn't stop there—

because xavier does return, albeit very tired-looking (again i'd call this reminiscent of That Moment in "when shooting stars fall" where he brings her the protocore in hopes to keep her from dying).

and more than that, he explains. again, like what happened in the no restraint card, he explains. he doesn't keep things vague on purpose, or makes it seem like he's hiding something from her. he explains, and he takes the initiative to, if only to soothe her worries.

to soothe her worries.

that's an important point.

(and also on a side note:)

HDJJAJDJSJ I HAD TO AND THIS IS A DIRECT PARALLEL TO "No matter how many times it takes, no matter where you are... I will find you." BY THE WAY

anyway......!!!!!!!!! again, it doesn't stop there.

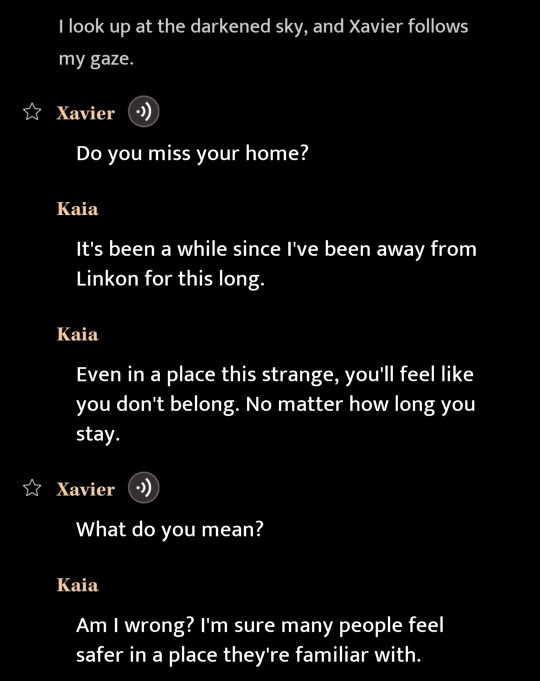

because this scene and this conversation also directly talk about home.

and this conversation means a lot more to xavier than, i think, generally one would realize. mostly because—and i remember kay making a really good point about it here—xavier has gone through a lot to get to where we see him now, and so much of change that he's had to get used to... time traveling so far only to get stuck? the different lifetimes he and the backtrackers would have had to witness this whole entire time?

like i mentioned, our brain's natural instinct is to strive for stability—you can even see it in what we know from our high school biology lessons a la homeostasis. yet, what xavier went through, what the backtrackers went through, is one hell of a shock of a change. it's the kind of change that needs processing, but isn't easy to process, and especially not quickly. and xavier had little to no one to lean on for support, to lean on to guide him through it. the result of which being that, as established even in his earlier cards... change isn't something he likes.

and as also established in world underneath, we know he just simply wants a neat little mundane life with mc.

keyword: with mc.

he doesn't really know what home is, because he has a distorted perception of it—the xavier now, in this moment, still recalls his home planet, the life he has ties to, back in philos. but as he is now, his home is in linkon. and then it comes to the conclusion that the answer is, really truly, neither.

his home is with her.

he says it, this time, explicitly.

it's his declaration that it's okay if things change, as long as he has her—as long as she remains the constant. then change is something he can deal with.

yet, even as he reveals all this to her, the conversation starts with him asking her. the conversation starts about her. and it's she who's able to give the opening back to him, by touching on things like change and belongingness.

"Even in a place this strange, you'll feel like you don't belong. No matter how long you stay ... Am I wrong? l'm sure many people feel safer in a place they're familiar with."

mc isn't a stranger to change, either—she's had a lot of it in her life, specifically the life she lives now as a hunter. the chronorift catastrophe, her family... it's not as if she doesn't know how jarring change can be, and she expresses that here—having to "start again" in a place she's unfamiliar with... it's not easy, and it's easy to feel out of place.

humans are social creatures. we were made to be social, we were made to interact with others. but from that need and that inherent desire (because no matter how small, it's always going to be there) stems the need to belong. a human emotional need to affiliate with and be accepted by members of a group.

this is something that is so prominent in mc that it is a place of solace for her to feel like she belongs somewhere. but this sense of belongingness is something that xavier has NOT experienced for a long, long time. it's only something he's been learning to experience again with her, and the people that surround them in this life that want nothing but the best for them both.

it goes back:

his home is wherever she is.

and i think that it's beautiful that, after hearing xavier's side, mc then chooses to agree with it:

"Maybe... the sense of belonging I have is like yours."

if his home is wherever she is, then her home is with him.

ALSO— while we're talking about this scene... the little banter they have with the flower cake?????? AND THE FACT THAT HE KISSES HER?!!?!?!?! JUST LIKE THAT!!!???!?!?!?!?!! (if you can't tell, i yelled about it)

AND THIS SCENE;?!

—"His eyes are a little red, maybe because of how exhausted he's been lately. Even his blinking has slowed down ... 'I'm a little tired. Can I lie down for a bit?'"

—"Before I can answer, Xavier rests his head on my lap."

DIRECTLY plays out the mutual reliance they have on one another for comfort and rest, because it parallels that line in lightseeking ovsession that we're all familiar with:

"You rest, I’ll be by your side. Always. If you have nowhere to go, nowhere to rest your weary self… you can stay with me."

i think that as much as they have been growing in to their own persons, they're both so closely intertwined, and so much of their love for each other really just pours out all the time.

iii. xavier's forwardness

granted, one thing that's interesting in this is that they do start out pretty tame. there's a little bit of a vague area concerning their relationship at the start of the card, especially since mc seems back into her old habits of starting something and not following through—or otherwise, unintentionally starting something, and then shying away afterwards. she does get noticeably flustered, but she pushes the fluster away... almost as if old habits die hard.

...but xavier, on the other hand, is more consistently bold with whatever he's doing.

there's no hesitation on his part at all, even.

in fact, xavier is the one who initiates most of these things, and doesn't shy away from it. his cheekiness really shines through—he's the one who kisses her suddenly (and for all the other kisses he initiates in the card); he's the one who fixes her clothes, her hair; he's the one playing around while teaching her calligraphy; he's the one who's so eager and unbothered about showing off their relationship:

—"Did we need to hide? Or can the Young Master not chat with a Flower Goddess?"

—"It was going to be awkward... And I heard one of the hosts of this ceremony is the mansion's owner. Since you're an organizer and the Young Master, it wouldn't look good if I was biased, right?"

—He touches the small of my back, which makes me stand up straight. "But you always have special place in my heart."

and:

"Well, I guess everyone knows now. Does this mean I can officially play favorites?"

like he's actually being SUCH a menace i had to pause and take a deep breath

but he's very consistently bold, and it, again, goes back to the confidence that he's gained in himself. he seems a little less of the uncertain, almost shy ish xavier who didn't quite know how to make proper advances... this time, he knows mc is comfortable with his advances, and he gets to play around with that. they're comfortable around each other, to this point that he can be a little more free with his words and his actions.

and eventually, we see mc beginning to reciprocate that again—especially during the festival itself, and in the kindled moments.

which brings me to...

iv. the festival day

i'd specifically talk about, here, the moment before the dance and during the dance.

because it's alao the exact moment that we see mc begin to actually reciprocate and throw back her own advancements—it's the exact moment we have a confirmation that she loves him, that she adores him, that he means so so so so much to her.

and on the day of the festival, we go back to what i highlighted earlier:

he soothes her worries.

the first instance we see this is their little "reunion" that we talked about—it's his very presence, and his added explanation, that calms her down in that moment.

and now is not so different:

—"The most important part of the ceremony, the Flower Goddess Dance, is about to begin. I glance again at the crowd. 'Where will you be during the dance?'"

—"Xavier gently takes my hand that's holding the petal. 'That flower from the roadside will wilt if you keep touching it.'"

—"'I'm just a little nervous.'"

—"'Scared of dancing, hunter? Actually, I got you a gift ... It was meant to be a surprise. But since you're feeling nervous, I figured I should tell you."

—"'That works. Now, my focus has shifted to the excitement about your gift.'"

(which, another side note, but "Scared of dancing, hunter?" had me GASPING because???? the way he teases her in this?! it's so unabashedly him without holding anything back, no coyness about it but he's being a cheeky little shit 😭 i adore him...)

a few things to note here is that out of context, it does feel like a little bit of an awkward way to be comforting someone—yet, it works extremely well. what xavier does here is not provide reassuring sugarcoated words like "it's going to be okay", he distracts her from the problem instead by giving her something to look forward to. which, in this case, is the gift.

interestingly, in a way the 'distracting' is also reminiscent of something he does when he tries to hide something from her—cutting the conversation short when she asks about lumiere, in the lumiere myth asking her to go check on the 'wanderer' so as not to let her see what he had to inject from the ship...

in his lightseeker myth, they talk briefly about his fight with the king, and the possibility of him no longer taking the throne. this conversation proves vague and a little bit one-sided, and in the end he pushes forward the idea of eloping to uluru almost as if to avoid further discussion about the fight itself.

but this time, that's not particularly where he stops: he addresses her question as well, just to find a fallback, an extra little bit of reassurance.

—"'See that tree over there? I'll be standing under it.'"

—"I follow Xavier's gaze. Nearby is a tree covered in red silk ribbons and wooden plaques by the bridge. 'So if I mess up the dance, you'll see everything, huh?'"

—"'I promise I'll forget about them after a good sleep.' His gaze remains on my face, appearing indifferent. Yet I sense a passion about to overflow. 'The only thing l'll remember today is your beauty.'"

FIRST OF ALL. "The only thing I'll remember today is your beauty." A BEAUTIFUL FUCKING LINE, BY THE WAY. IT GAVE ME LITERAL BUTTERFLIES I HAD TO PAUSE FOR A MOMENT. (1) more proof that in the end she's really all he cares about, (2) he's being unabashedly bold with his words again—no filter moment, but zero hesitation, (3) "i sense a passion about to overflow"? he's not being coy about this either, he's saying what he truly feels. he's opening up and expressing himself more, expressing his love for her more, and being genuine about it!

but also, in terms of additional comfort, it's a widely known tactic in states of panic to ground yourself by using your senses to register something familiar: you see something familiar to you, hear something familiar to you, touch something familiar to you, smell something familiar to you. such as, the ground beneath your feet. the air around you, the vague sound of chattering around you, maybe even the touch of your bag, or the fabric of your clothing, the window you know has always been there, etc. panic brings about a sense of derealization, and grounding yourself is usually the first step to calming down.

what xavier is doing now is offering the knowledge to her that he will be there. that she knows exactly where to look for him if she needs to during the dance. she has the opportunity to ground herself with his presence whenever she needs to.

(and again, it's a direct reflection of that line: "You rest, I’ll be by your side. Always. If you have nowhere to go, nowhere to rest your weary self… you can stay with me.")

and it's exactly what she does.

though she ends up enjoying the dance and the crowd does block her direct view of the tree during the dance itself, she takes comfort in the fact that she knows he's there.

she trusts him; she doesn't need to see him to know that he'd there.

and then she thinks something beautiful:

"Engrossed in the dance's rhythm, my mind is strangely at peace. After all, I know there's someone in the crowd whose eyes are only on me."

once again, it goes back—his presence offers her comfort.

the first thing she does once she's received all the flowers is run to him, and he waits for her gladly. like he's always waited for her, like he always will wait for her.

"A lot of people wanted to give you flowers. I couldn't get past them, so I decided to wait for you here. Seems they're quite fond of you, just like me."

a note: the peach blossom

i figured this deserved a section on its own actually, particularly because the whole theme is this whole "flower goddess" thing... and in the beginning, we see mentions of the "goddess of daffodils" and the "goddess of peonies".

yet, we never really truly find out what mc's potentially assigned flower was—

the only mention of a flower that we do see, directly related to her, is when the little kid compliments her hair and places a peach blossom into her basket.

and while i wouldn't know if this means it's her flower or not, but the specific mention of the peach blossom is adorable, because in chinese floriography, the peach blossom represents love.

it's used in a lot of chinese literature and often associated with the arrival of spring—which, "according to the rites of zhou, the middle of spring is a period when men and women fall in love freely." therefore, a lot of chinese literature and poems also allude peach blossoms to romance, being that spring does as well. but, it's also associated with beauty: "after the wei and jin dynasties, beauties were portrayed in a more detailed way with words like taohua mian (peach-blossom-like face) or tao sai (peach-blossom-like cheek)." and there are other things it represents too, like prosperity, growth, and longevity.

when xavier gives mc the hairpin at the end, mc describes it as "pretty and adorned with pink flowers as if they are on a branch", and while not explicitly stated, i do believe that they are also peach blossoms.

whether or not that's the case, and whether or not the peach blossom was mc's flower (or maybe that it's just generally part of the festival), i think it's a really cute detail! i think it perfectly represents their growing relationship, and essentially the beauty with which xavier always sees her~

BUT, MOVING ON.....

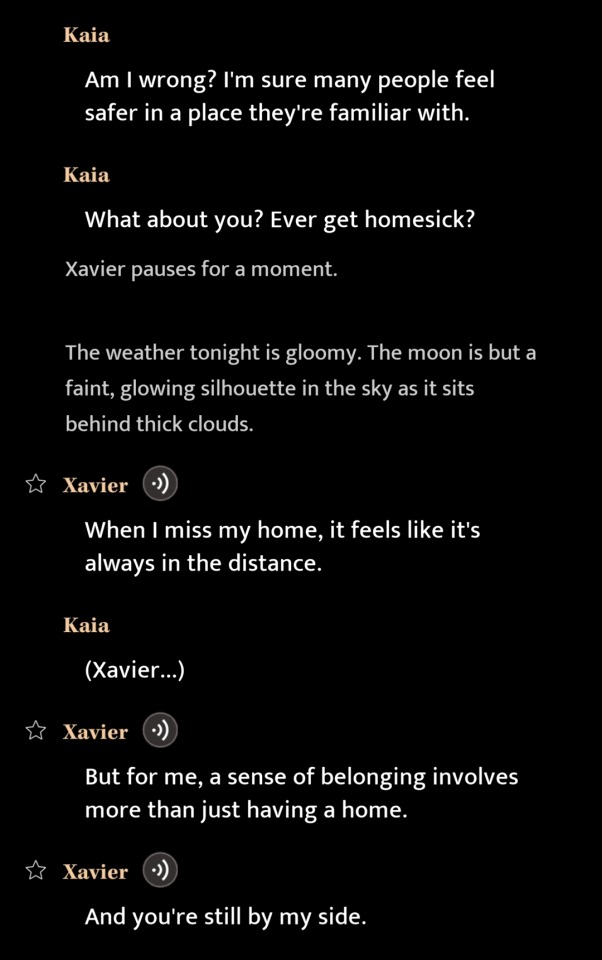

v. the wish

the final stretch boils down to this.

"A gentle breeze stirs the wooden plaques hanging from the branches. A faint, melodic sound dances in the air. 'They say a Flower Goddess can bless people's wishes. And if the person making the wish is someone she favors, it's more likely to come true.'"

it's where the kindled moment falls, as xavier proposes for them to make a wish together.

and, mind you, this whole entire scene is ADORABLE AND LIVES RENT FREE IN MY HEAD ... the playfulness between their words, the "if i tell you my wish, it won't come true", the way xavier CARRIES HER??? AND THE WAY HE CATCHES HER WHEN SHE FALLS AND PINS HER AGAINST THE TREE AND AND AND AND.

everytime i think of it i end up keysmashing in my head IT'S JUST SO CUTE i could burn it into my head 😭😭😭😭

but, AHEM, he also says...

"Throughout history, humanity has always made the same wishes. Perhaps it's because those feelings we have... are timeless."

i think it's a really pretty line, but more than how pretty it is, i think it represents xavier perfectly.

xavier has lived long enough, and he's likely also made similar wishes along the way. for mc to be safe, for mc to be happy... things along those lines. and for him to describe that as "timeless" also represents his love for her—because it is timeless. he loves her more than anything else in the world. it transcends space, and time, and anything else; to him, she is love. she is timeless.

it's worth noting that everytime xavier and mc get scenes where they wish together, xavier never really says what his wishes are.

in "when shooting stars fall", mc wishes for many things. for xavier's freedom and happiness, for her to be healthy, for time to stop in their moment together... for xavier's freedom, xavier's happiness, and, in her final moments—"i wish to meet you in my next life." but he's never said explicitly what he wished for at all.

in "warm wishes", mc also mentions a lot of wishes:

"I wished I could pass all my tests with flying colors and go to a good university. I wished for Grandma to be healthy. I wished for my neighbor's cat to come home..."

and her actual wish that night was:

"l wish.... everyone can have snowflakes fall on their shoulders when they're lonely, and see the stars when they're lost."

yet that night, xavier didn't make a wish. he explicitly stated:

"l didn't make a wish. I want to save my wish for when I need it the most. Plus, everything I want right now has come true."

...but this time is different.

he did make a wish.

and, this time around, he specified what it is.

"I wish I can be your sanctuary until the end of time, in your eyes."

this is a wish that's important to him. he chooses to make this wish, and he chooses to tell her about it.

there's a lot to dissect in just one statement alone, because it's so imbued into the xavier that's loved her for thousands of years.... the xavier that has grown and developed into who he is in this moment.

a sanctuary is a place of refuge and protection; a place of safety. a place of comfort. a place of rest.

and multiple times throughout this card, it highlights how xavier has been able to offer mc a certain sense of comfort. even right when the results are announced, one look at him calms her down—this part really got me.

"I glance nervously at Xavier. He makes eye contact with me, and his gaze conveys a steadfast reassurance."

it's a recurring theme in the card—comfort. peace. the peace that you can find in someone. the safety that you can find in someone. in this case, mc with xavier, and vice versa.

...and i've always associated xavier with comfort, but peace and safety have been attributes i've been hesitant to associate with him, because it's different. for you to feel safe with someone, for you to feel at peace with someone, they need to communicate, as well, a certain sense of steadfast reassurance. xavier has always been soft and comfortable, but he hasn't always exuded that steadfast type of aura.

i think that this is something that he himself realizes.

i've mentioned it before, but his wish is also a direct parallel to That Line from lightseeking obsession.

"You rest, I’ll be by your side. Always. If you have nowhere to go, nowhere to rest your weary self… you can stay with me."

yet there's also a striking difference.

what is different?

the person that he's developed into.

prince xavier, lightseeker xavier—as i mentioned earlier, there's a certain kind of confidence in himself that isn't present, and it shows. i would argue that he was at his most vulnerable that time, likely more vulnerable than when they first landed on earth, because he didn't know how to treat his relationships at all. he was too bound by the confines of what everyone, and i mean everyone, including mc at the time, wanted him to be. there was never clear communication with anyone, and it mostly seems as if he's been going through the motions—as opposed to more freedom that he's been granted on earth.

and it shows, because, that line in lightseeking obsession—does not exude confidence.

it's a comforting statement, sure...

but it's not even something that mc herself believes.

"you always lie."

it's as if xavier, as much as he's trying to comfort mc, is trying to reassure himself, too—he tries too hard to make himself appear reassuring to her that it falls short, all this on top of the times that she feels she's been let down by him.

it's ironic, almost. he says such a bold declaration despite knowing that there's a chance he wouldn't be able to keep it.

but this is different.

this time, xavier has grown to he sure of who he is and who he wants.

he said it in 21 days—"every version of me belongs to you, and only you."

yet despite the confidence that he now has in himself, notice how different this is to lightseeker's line—

he's wishing.

and he specifies that he wants it to be true in her eyes.

it's as if he's saying, i'm not sure if this is what you think about me, but i do know that i want it to be what you think about me.

he's not reassuring her; he's not making a bold declaration. he's not saying, you will think of me as a sanctuary. neither is he saying, i will be your sanctuary.

he's saying, i want to be your sanctuary.

the final decision falls to her.

the confidence lies in stating what he wants, and there's no fear in it—there's no hesitation, nothing that implies that he's scared to say it. he's confident in what he says, and either confident that she'll accept it, or confident that no matter what her choice is in the matter it's okay.

that's why this wish is so strong.

and it's mc who then says, at the end;

"I wanted to tell you that your wishes will always come true."

because she reciprocates.

and this whole moment, everything that happens from hereon—the results, the hairpin...

—"'If you meet a Flower Goddess you like, give her fresh flowers. It's a local custom here. But there are many people who admire you, and all of them have given you flowers. My flower wouldn't be special enough. So, I made a flower hairpin. This is the first time I made one, though. Don't judge it too harshly.'"

—"Xavier's hand is warm. Like petals being carried on the wind, his smile descends and touches my heart. 'What makes you say that? It's amazing. Besides, even if you just gave me flowers, they'd be the most special ones l've ever received.'"

it's worth noting that the scene where xavier gives the hairpin is also very much the same way he makes the wish. he does admit that he doesn't know if she'd appreciate flowers—but he takes it a step forward. he knows he wants to be extra special, he knows he wants her to have something she'll remember, so he does something different. he makes, and gives her, a flower hairpin. of his own accord.

it doesn't stop at his insecurities, which he still has—he takes those insecurities and spins them into something he can be sure of himself.

and there it is again.

the steadfast reassurance.

and it's what makes the moment so much more memorable to mc, so much more meaningful.

and it's why, then, he can say things like this:

"No matter what happens, I'm always blessed to have someone by my side, who makes my gaze never feel alone."

"Forever is but a collection of moments strung together. With every minute comes another, second after second. When I open my eyes again, I want you to still be by my side."

it's in a way wherein xavier is able to take some lead in their relationship, because he's more sure of himself this time. and it progresses their relationship in a way that it wouldn't have if he never learned—he's learning. he's growing. and he's really truly turning out to be someone that can love with his whole heart, without holding back.

i think this card showcases that the most, and maybe that's why i love it so much <3

ALSO, P.S., ONE MORE PARALLEL—

xavier says that the flowers are blooming beautifully this season—"it smells like spring". in his lightseeker myth, he says: "With spring's arrival, hope is soon to follow."

and its just a neat lil thing, i think <3 spring is always so closely associated with xavier, and the card really does end on such a light and hopeful note.

#GOOD ALMOST-AFTERNOON#to me and my love for this card#love and deepspace#love & deepspace#lnda#lads#l&ds#xavier#love and deepspace xavier#love & deepspace xavier#lnds xavier#lads xavier#l&ds xavier#lndthonks 🌹#lnds garden 🌹

118 notes

·

View notes

Note

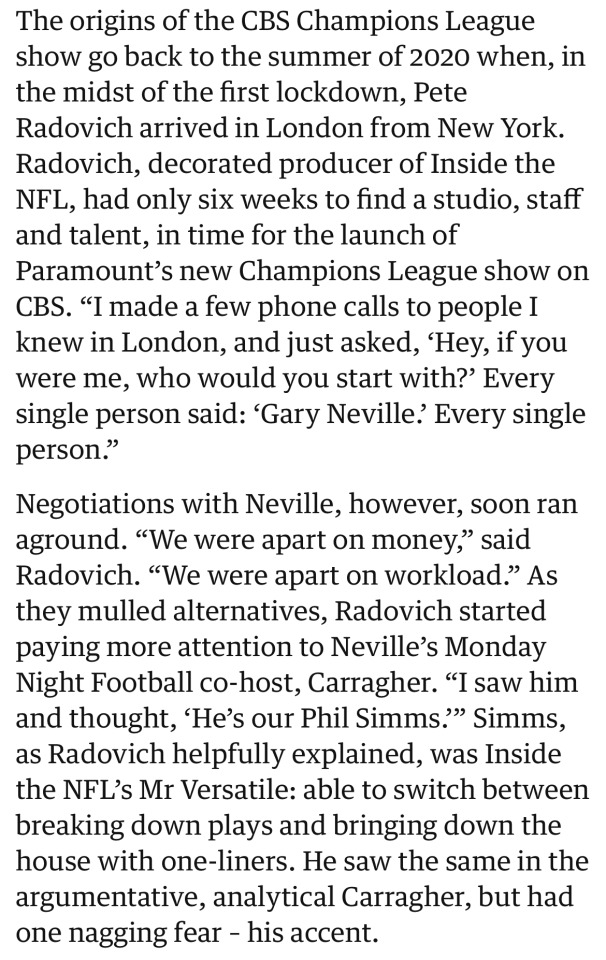

theguardian dot com /football/ng-interactive/2025/may/22/extremely-loud-and-incredibly-scouse-how-jamie-carragher-conquered-football-punditry

i didn't think philly would be so protective of jamie tbh... it's a nice article, i really liked it, but no one analyzes this annoying scouser like you do asdakdhsh

I WAS READING THIS LAST NIGHT Oh my godddd I was losing my mind

He doesn’t carry a wallet fkkwkfkwndjw

unglamorous utility player what if I cried he was just an afterthought in his club I

3. Kate calling him a professional rage baiter/troll basically. He knows exactly what he’s doing and enraged footy fans fall for it every single time.

4. Carra….carra just being at home in Liverpool, doing things in the community all the time…

5. Clawing at my hair. Okay…. Oh my god.

6. Absolutely insane Carravile early days lore. Jamie WANTED to be on MNF with Gary specifically. 7. “In a tone that didn’t sound like joking.” So. Gary did think of ending Jamie’s career? Like for real? Cruel man 😭😭😭

8. Baby….

9. “A cutting and patronising ‘James’ to bring Carragher back to heel” WHO IS WRITING THIS

10. CBS wanted Gary Neville instead but he was apparently too expensive. So. Is Jamie just a cheap whor-

11. Peter and Jamie apparently giving each other stick for 45 mins until someone is like can we start the meeting now fiejskwjs @storyshark2005 for your Peter x Jamie agenda

ANYWAYS sorry I raved too much I was a bit excited abt article and noooooo anon you flatter me. It’s not that I analyse Jamie a lot I don’t djjsjsks fucking like him I want to shoot him like prey but cskiwkskskwks I really liked this article too…. Thank you sm for sharing

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

If Batfamily members were part of the Avatar (The Last Airbender) universe. Which element would each be able to bend?

It’s probably been done before by other creators, but I will write each one of my headcanons and why I think they’d bend that element. You’re free to think otherwise about these.

Water: as Uncle Iroh explained to Zuko, water is the element of change. The people of the water tribes are capable to adapting to many things. They have a sense of community and love that holds them together through anything.

•Dick - had to evolve many times in order to fit, whether from an orphan to a billionaire, a sidekick to forming his own team (the titans), or even moving cities altogether and becoming his own hero.

•Bruce - the original evolving character. He had to adapt from having loving parents to being an orphan. From being a one man show to having sidekicks and a whole team formed of superheroes. Whether he realizes it or not. He’s build a community around him to help the people that are part of it, feel loved and understood.

Earth: Earth is the element of substance. The people from the earth kingdom are diverse and strong. They are persisting and enduring.

•Cass - to begin and try to explain how enduring Cass is would be a whole essay on its own. She was raised from the minute she was born to be a living weapon. Endured years of abuse towards that goal. And much like Toph, she concentrates, analyses and concludes before she attack.

•Jason - I know Jason could arguably be added as part of the fire element as well. But he’s been one of the Batfamily members that has had to endure a lot. His parents abused and neglected him, he never adapted to Bruce’s moral code, he was killed by the joker and brought back only to be another soldier for the League. He is strong in more ways than just physical strength and has never stopped persisting about what his beliefs are, even if that has created a breach with his family at times.

Fire: Fire is the element of power. The people of the fire nation have desire and will and the energy and drive to achieve what they want.

•Damian - a lot like Zuko, Damian’s drive and will was at first conducted by anger, superiority and desire for power. But the more he has immersed himself in achieving his own goals, and not the ones that were imposed to him by other people, he has been one of the most strong willed and powerful members of the Batfamily.

•Kate - Since childhood, Kate has been someone that felt she lacked power over her own life. The kidnapping, the loss of her mother and sister, her expulsion from the military, and overall control of her destiny. But this hasn’t stopped her from achieving what she wants. The will she has is enormous.

Air: Air is the element of freedom. The Air nomads detached themselves from worldly concerns and found peace and freedom. Also, the apparently had pretty good senses of humour.

•Steph - having to detach yourself from your own blood is something incredibly difficult. But Stephanie proved this can be done in order to achieve freedom when she took the mantle of spoiler and helped Robin and Batman take down her own father. She forged her own path.

•Alfred - One of the greatest characteristics from air nomads is their ability to remain peaceful. With every single thing the bat kids have put him through, he remains one of the more sarcastic and empathetic members of the family, and also a true guide for each of them.

Non-benders: Having no bending abilities has never been an impediment for the people of the four nations. We’ve seen them being great combatants, logical thinkers and overall, people that had earned their place amongst the people that seem to be ‘most powerful’.

The following three are listed as non-benders is mainly the result of their efforts to prove themselves in order to be a part of the Batfamily.

•Tim - His own strength has always proven to be his intellect. No combat, threats or anything physical at all was needed in order for him to use his mind to act as the greatest detective of this family and find out Batman’s identity. His brain has proven more useful than any violent action. He earned his spot inside the family.

•Barbara - Much like Tim, Barbara proved her own way into the family. She started out as a potential casualty in Batman’s book, but she quickly proved herself to the family. Even after being incapacitated to deal with criminals hand to hand, her logical thinking has helped the family perhaps even more with her role as Oracle.

•Duke - after losing his parent’s sanity at the hands of the joker, Duke also proved himself with the ‘we are Robin’ movement. He couldn’t care less about how powerful anyone else was, because he knew that what the movement represented was far more important than walking amongst heroes.

*All of the above could arguably be moved from one element to the other, but this is my personal headcanon.

#batfam#avatar the last airbender#bruce wayne#dick grayson#damian wayne#batman#jason todd#tim drake#stephanie brown#cassandra cain#kate kane#barbara gordon#duke thomas#alfred pennyworth#batman and robin#headcanon#fandom#crossover#water earth fire air#elements#four nations#uncle iroh#zuko#atla

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

A John Herschel Character Study

I have a lot of feelings about John that go into how I characterize him so I decided to organize them in an “essay” for Day 14: Family of @pulpmusicalsfortnight2024. This is my deep dive into how John's family and childhood affect him today, going into his character arc in the three published episodes of Pulp Musicals. Obviously your mileage may vary but this is the basis for my characterization of John when I write him. Inspired by @eggingtontoast's wonderful analyses of Karen Chasity and Jeri from the Hatchetfield series. Huge thanks to @snarky-wallflower for betaing this for me!

So starting in his childhood:

In the few lines we get about him, John's father is described as being firm and no nonsense.

In Polaris, John says that his father would be “unamused” by him playing a game with his astronomy knowledge and that would say “[You're] just tracing lines 'round things [I] spent [my] life to find.” Specifically, John noted that his father would be against it as it provided “no real benefit to society.” To me, these quotes are just a little too specific to be speculation; I bet William Herschel said this to John before, especially since John knows all the constellations despite his father apparently believing them to be unimportant.

I speculate that William Herschel has constantly reinforced this concept in John, that science isn't fun, it's important and respectable, and that John needed to be important and respectable in turn. And I think John took it to heart over the years. John's reputation is clearly incredibly important to him. He is also deeply concerned about what his father thinks of him, almost to the point of terror, in my opinion.

He moved his entire project thousands of miles away and constructed it in total secrecy just so his father wouldn't learn if he failed. Samuel is so sure John's dad must be proud of him, but all John seems to feel is afraid.

His reputation is tied so tightly together with his father's, that John's own failings will reflect onto him, and John's life is a constant comparison to his father's works. John even says that people consider his actions to be an extension of his father's “dreams... hopes, and fears” in Through a Glass. The shadow is long and all-encompassing, and John seems to feel the weight of it heavily. “The apple doesn't fall far from the tree, when they put a glass to me.”

Whether William Herschel intended this or not, the constant pressure from both his father and society has led John to develop an unhealthy fear of failure and being seen as lacking, and all of this ties into his public persona. He needs to be taken seriously, and puts on this front of being stern and unflappable.

His isolation only adds to this. He claims that he prefers being alone when he speaks to Rose in It's a Hoax (Reprise)/Carry On. “I should be in another hemisphere alone with the milky way.” We know he gets letters from Anna, his exception, the one person (so far) that he lets his walls down around, but other than that, he is utterly alone. He is “away from the world, but close to [his] heart.” He even admits this was intentional in the Shifts Reprise, that he “built a wall ten miles high of essays, books, and quips.” All John needs is his studies and the sky. He has removed himself from humanity entirely, and has been that way for three years.

This is the John we meet in Before the Storm and It's a Hoax (Reprise)/Carry On.

John comes in and is immediately uptight and no nonsense. This makes sense, given the ramifications of the hoax; John's reputation and most likely his father's opinion are highly on the line. He seems unpleasant at first, an antagonist to the twins’ writing dreams but... He is very quickly taken with Rose.

He doesn't want to be, initially seeming confused and standoffish towards her questions about his work, but she barrels through his defenses. He enjoys that connection, softens, calls her Rose.

Until he learns what she's done and that persona snaps right back in place, his commitment to his reputation and the validity of his name superseding that genuine human connection.

Then, John witnesses something impossible. Margaret glowing. The Radiance. A scientific marvel straight out of a fairy tale.

And we've reached John's Choice.

Because in my opinion, it is not just John's Choice for the story, but of what kind of man he is going to be.

This is where Benjamin comes in. Benjamin serves as John's foil in the Great Moon Hoax. We've witnessed his story; of Benjamin's initial wonder with Hoax, the way the writing moved him enough that he risked everything and gave it a platform, only to betray both it and the Stratfords in the end.

Benjamin loved the story but there was always that undercurrent of greed and a focus on the money and social status that could be gained, i.e. his “We'll be rich by the end of the day.” in Is it True?

On the other hand, though John came in upset over the story and the damage it could do to his reputation, he has always been a little enamored with the Hoax. He says it was good! He mostly focuses on the science, but also says that in another life, he and the writer could have gotten along. He likes it, despite himself.

The Hoax lit that spark in him again, the one William Herschel saw no value in. Margaret's Radiance fanned the flames.

And so, when push comes to shove, John chooses the Hoax, the story. He chooses the whimsy and creativity and a world with no laws of gravity. He laughs. He becomes the story teller for a theoretical Great Astronomical Discoveries #4, and he “gives it all” to the crowd gathered. He even assists in getting Chester Thomas to continue publishing fiction!

As Benjamin writes himself out of the story, John writes himself into it.

And we see a whole different side to John in the Brick Satellite as this shift in his values continues! He has moments of that initial stuffiness, when he gets all huffy over the Moon Hoax (but never truly mad, not in the way Margaret is), but he shows more of himself, removing bricks from his own personal walls as they add the bricks to the Satellite.

He plays games with Rose on the ship during Polaris, he reveals his vulnerabilities to Samuel in Through a Glass. Samuel even recognizes him as one of their own during this song. When John says, “Imagining’s what you do,” Samuel replies, “A trait I share with you.” John isn't just a scientist, he's a dreamer who imagines a better world, just like the Stratfords.

This culminates in John and the Earth, the tipping point. Because, the roles are fully reversed from so long ago in South Africa. John looks down at the Earth, at all the people he had walled himself away with for so long, and he loves them so fiercely he cries. He stands in the gift he created for humanity on his own dime with no recompense expected and he says “Heaven's not up here in the sky, heaven’s down there.”

He has looked to the heavens his whole life. It was what was expected of him, the footsteps he was supposed to follow. But looking at the Earth, he sees it. Sees what matters. He has never “felt so small”, away from all the fame and status his name and reputation give him. But he has also never felt “more part of it all.” Because that is John's story, the astronomer who falls in love with the Earth again.

(And falls in love with Rose, but he's still working on that one.)

#john herschel#pulp musicals#Pulp Musicals Fortnight 2024#Pulp Musicals Fortnight Day 14: Family#Character Study#my writing

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Haunting of Bly Manor as Allegory: Self-Sacrifice, Grief, and Queer Representation

As always, I am extremely late with my fandom infatuations—this time, I’m about three years late getting smitten with Dani and Jamie from The Haunting of Bly Manor.

Because of my lateness, I’ll confess from the start that I’m largely unfamiliar with the fandom’s output: whether fanfiction, interpretations, analyses, discourse, what have you. I’ve dabbled around a bit, but haven’t seen anything near the extent of the discussions that may or may not have happened in the wake of the show’s release, so I apologize if I’m re-treading already well-trod ground or otherwise making observations that’ve already been made. Even so, I’m completely stuck on Dani/Jamie right now and have some thoughts that I want to compose and work through.

This analysis concerns the show’s concluding episode in particular, so please be aware that it contains heavy, detailed spoilers for the ending, as well as the show in its entirety. Additionally, as a major trigger warning: this essay contains explicit references to suicide and suicidal ideation, so please tread cautiously. (These are triggers for me, and I did, in fact, manage to trigger myself while writing this—but this was also very therapeutic to write, so those triggering moments wound up also being some healing opportunities for me. But definitely take care of yourself while reading this, okay?).

After finishing Bly and necessarily being destroyed by the ending, staying up until 2:00 a.m. crying, re-watching scenes on Youtube, so on and so forth, I came away from the show (as others have before me) feeling like its ending functioned fairly well as an allegory for loving and being in a romantic partnership with someone who suffers from severe mental illness, grief, and trauma.

Without going too deeply into my own personal backstory, I want to provide some opening context, which I think will help to show why this interpretation matters to me and how I’m making sense of it.

Like many of Bly’s characters, I’ve experienced catastrophic grief and loss in my own life. A few years ago, my brother died in some horrific circumstances (which you can probably guess at if you read between the lines here), leaving me traumatized and with severe problems with my mental health. When it happened, I was engaged to a man (it was back when I thought I was straight (lol), so I’ve also found Dani’s comphet backstory to be incredibly relatable…but more on this later) who quickly tired of my grieving. Just a few months after my brother’s death, my then-fiancé started saying things like “I wish you’d just go back to normal, the way you were” and “I’ve gotten back on-track and am just waiting for you to get back on-track with me,” apparently without any understanding that my old “normal” was completely gone and was never coming back. He saw my panic attacks as threatening and unreasonable, often resorting to yelling at me to stop instead of trying to comfort me. He complained that he felt like I hadn’t reciprocated the care that he’d provided me in the immediate aftermath of my brother’s loss, and that he needed me to set aside my grief (and “heal from it”) so that he could be the center of my attention. Although this was not the sole cause, all of it laid the groundwork for our eventual breakup. It was as though my trauma and mourning had ruined the innocent happiness of his own life, and he didn’t want to deal with it anymore.

Given this, I was powerfully struck by the ways that Jamie handles Dani’s trauma: accepting and supporting her, never shaming her or diminishing her pain.

Early in the show—in their first true interaction with one another, in fact—Jamie finds Dani in the throes of a panic attack. She responds to this with no judgment; instead, she validates Dani’s experiences. To put Dani at ease, she first jokes about her own “endless well of deep, inconsolable tears,” before then offering more serious words of encouragement about how well Dani is dealing with the circumstances at Bly. Later, when Dani confesses to seeing apparitions of Peter and Edmund, Jamie doesn’t pathologize this, doubt it, or demean it, but accepts it with a sincere question about whether Dani’s ex-fiancé is with them at that moment—followed by another effort to comfort Dani with some joking (this time, a light-hearted threat at Edmund to back off) and more affirmations of Dani’s strength in the face of it all.

All of this isn’t to say, however, that Dani’s grief-driven behaviors don’t also hurt Jamie (or, more generally, that grieving folks don’t also do things that hurt their loved ones). When Dani recoils from their first kiss because of another guilt-inspired vision of Eddie, Jamie is clearly hurt and disappointed; still, Jamie doesn’t hold this against Dani, as she instead tries to take responsibility for it herself. A week later, though, Jamie strongly indicates that she needed that time to be alone in the aftermath and that she is wary that Dani’s pattern of withdrawing from her every time they start to get closer will continue to happen. Nonetheless, it’s important to note that this contributes to Dani’s recognition that she’s been allowing her guilt about Eddie’s death to become all-consuming, preventing her from acting on her own desires to be with Jamie. That recognition, in turn, leads Dani to decide to move through her grief and beyond her guilt. Once she’s alone later in the evening after that first kiss, Dani casts Eddie’s glasses into the bonfire’s lingering embers; she faces off with his specter for a final time, and after burning away his shadow, her visions of him finally cease. When she and Jamie reunite during their 6:00 a.m. terrible coffee visit, Dani acknowledges that the way that she and Jamie left things was “wrong,” and she actively tries to take steps to “do something right” by inviting Jamie out for a drink at the village pub…which, of course, just so happens to be right below Jamie’s flat. (Victoria Pedretti’s expressions in that scene are so good).

Before we continue, though, let’s pause here a moment to consider some crucial factors in all of this. First, there is a significant difference between “moving through one’s grief” and simply discarding it…or being pressured by someone else to discard it. Second, there is also a significant difference between “moving through one’s grief” and allowing one’s grief to become all-consuming. Keep these distinctions in mind as we go on.

Ultimately, the resolution of the show’s core supernatural conflict involves Dani inviting Viola’s ghost to inhabit her, which Viola accepts. This frees the other spirits who have been caught in Bly Manor’s “gravity well,” even as it dooms Dani to eventually be overtaken by Viola and her rage. Jamie, however, offers to stay with Dani while she waits for this “beast in the jungle” to claim her. The show’s final episode shows the two of them going on to forge a life together, opening a flower shop in a cute town in Vermont, enjoying years of domestic bliss, and later getting married (in what capacities they can—more on this soon), all while remaining acutely aware of the inevitability of Dani’s demise.

The allegorical potentials of this concluding narrative scenario are fairly flexible. It is possible, for instance, to interpret Dani’s “beast in the jungle” as chronic (and/or terminal) illness—in particular, there’re some harrowing readings that we could do in relation to degenerative neurological diseases associated with aging (e.g. dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, progressive supranuclear palsy, etc.), especially if we put the final episode into conversation with the show’s earlier subplot about the death of Owen’s mother, its recurring themes of memory loss as a form of death (or, even, as something worse than death), and Jamie’s resonant remarks that she would rather be “put out of her misery” than let herself be “worn away a little bit every day.” For the purposes of this analysis, though, I’m primarily concerned with interpreting Viola’s lurking presence in Dani’s psyche as a stand-in for severe grief, trauma, and mental illness. …Because, even as we may “move through” grief and trauma, and even as we may work to heal from them, they never just go away completely—they’re always lurking around, waiting to resurface. (In fact, the final minutes of the last episode feature a conversation between older Jamie and Flora about contending with this inevitable recurrence of grief). Therapy can give us tools to negotiate and live with them, of course; but that doesn’t mean that they’re not still present in our lives. The tools that therapy provides are meant to help us manage those inevitable resurfacings in healthy ways. But they are not meant to return us to some pre-grief or pre-trauma state of “normality” or to make them magically dissipate into the ether, never to return. And, even with plenty of therapy and with healthy coping mechanisms, we can still experience significant mental health issues in the wake of catastrophic grief, loss, and trauma; therapy doesn’t totally preclude that possibility.

In light of my own experiences with personal tragedy, crumbling mental health, and the dissolution of a romantic partnership with someone who couldn’t accept the presence of grief in my life, I was immediately enamored with the ways that Jamie approaches the enduring aftereffects of Dani’s trauma during the show’s final episode. Jamie never once pressures Dani to just be “normal.” She never once issues any judgment about what Dani is experiencing. At those times when Dani’s grief and trauma do resurface—when the beast in the jungle catches up with her—Jamie is there to console her, often with the strategies that have always worked in their relationship: gentle, playful ribbing and words of affirmation. There are instances in which Dani doesn’t emote joyfulness during events that we might otherwise expect her to—consider, for instance, how somber Dani appears in the proposal scene, in contrast to Jamie’s smiles and laughter. (In the year after my brother’s death, my ex-fiancé and his family would observe that I seemed gloomy in situations that they thought should be fun and exciting. “Then why aren’t you smiling?” they’d ask, even when I tried to assure them that I was having a good time, but just couldn’t completely feel that or express it in the ways that I might’ve in the past). Dani even comments on an inability to feel that is all too reminiscent of the blunting of emotions that can happen in the wake of acute trauma: “It’s like I see you in front of me and I feel you touching me, and every day we’re living our lives, and I’m aware of that. But it’s like I don’t feel it all the way.” But throughout all of this (and in contrast to my own experiences with my ex), Jamie attempts to ground Dani without ever invalidating what she’s experiencing. When Dani tells her that she can’t feel, Jamie assures her, “If you can’t feel anything, then I’ll feel everything for the both of us.”

A few days after I finished the show for the first time, I gushed to a friend about how taken I was with the whole thing. Jamie was just so…not what I had experienced in my own life. I loved witnessing a representation of such a supportive and understanding partner, especially within the context of a sapphic romance. After breaking up with my own ex-fiancé, I’ve since come to terms with my sexuality and am still processing through the roles that compulsory heterosexuality and internalized homophobia have played in my life; so Dani and Jamie’s relationship has been incredibly meaningful for me to see for so, so many reasons.

“I’m glad you found the show so relatable,” my friend told me. “But,” she cautioned, “don’t lose sight of what Dani does in that relationship.” Then, she pointed out something that I hadn’t considered at all. Although Jamie may model the possibilities of a supportive partnership, Dani’s tragic death espouses a very different and very troubling perspective: the poisonous belief that I’m inevitably going to hurt my partner with my grief and trauma, so I need to leave them before I can inflict that harm on them.

Indeed, this is a deeply engrained belief that I hold about myself. While I harbor a great deal of anger at my ex-fiancé for how he treated me, there’s also still a part of me that sincerely believes that I nearly ruined his and his family’s lives by bringing such immense devastation and darkness into it. On my bad days (which are many), I have strong convictions about this in relation to my future romantic prospects as well. How could anyone ever want to be with me? I wonder. And even if someone eventually does try to be with me, all I’ll do is ruin her life with all my trauma and sadness. I shouldn’t even want to be with anyone, because I don’t want to hurt someone else. I don’t want someone else to deal with what I’ve had to deal with. I even think about this, too, with my friends. Since my brother’s death and my breakup, I’ve gone through even more trauma, pain, grief, and loss, such that now I continue to struggle enormously with issues like anhedonia, emotional fragility, and social anxiety. I worry, consequently, that I’m just a burden on my friends. That I’m too hard to be around. That being around me, with all of my pain and perpetual misfortune, just causes my friends pain, too. That they’re better off not having to deal with me at all. I could spare them all, I think, by just letting them go, by not bothering them anymore.

I suspect that this is why I didn’t notice any issues with Dani’s behavior at the end of Bly Manor at first. Well…that and the fact that the reality of the show’s conclusion is immensely triggering for me. Probably, my attention just kind of slid past the truth of it in favor of indulging in the catharsis of a sad gay romance.

But after my friend observed this issue, I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

I realized, then, that I hadn’t extended the allegory out to its necessary conclusion…which is that Dani has, in effect, committed suicide in order to—or so she believes, at least—protect Jamie from her. This is the case regardless of whether we keep Viola’s ghost in the mix as an actual, tangible, existing threat within the show’s diegesis or as a figurative symbol of the ways that other forces can “haunt” us to the point of our own self-destruction. If the former, then Dani’s suicide (or the more gentle and elusive description that I’ve seen: her act of “giving herself to the lake”) is to prevent Viola’s ghost from ever harming Jamie. But if the latter, if we continue doing the work of allegorical readings, then it’s possible to interpret Bly’s conclusion as the tragedy of Dani ultimately succumbing to her mental illness and suicidal ideation.

The problems with this allegory’s import really start cropping up, however, when we consider the ways that the show valorizes Dani’s actions as an expression of ultimate, self-sacrificing love—a valorization that Bly accomplishes, in particular, through its sustained contrasting of love and possession.

The Implications of Idealizing Self-Sacrifice as True Love

During a pivotal conversation in one of the show’s early episodes, Dani and Jamie discuss the “wrong kind of love” that existed between Rebecca Jessel and Peter Quint. Jamie remarks on how she “understands why so many people mix up love and possession,” thereby characterizing Rebecca and Peter’s romance as a matter of possession—as well as hinting, perhaps, that Jamie herself has had experiences with this in her own past. After considering for a moment, Dani agrees: “People do, don’t they? Mix up love and possession. […] I don’t think that should be possible. I mean, they’re opposites, really, love and ownership.” We can already tell from this scene that Dani and Jamie are, themselves, heading towards a burgeoning romance—and that this contrast between love and possession (and their self-awareness of it) is going to become a defining feature of that romance.

Indeed, the show takes great pains to emphasize the genuine love that exists between Dani and Jamie against the damaging drive for possession enacted by characters like Peter (who consistently manipulates Rebecca and kills her to keep her ghost with him) and Viola (who has killed numerous people and trapped their souls at Bly over the centuries in a long since forgotten effort to reclaim her life with her husband and daughter from Perdita, her murderously jealous sister). These contrasts take multiple forms and emerge from multiple angles, all to establish that Dani and Jamie’s love is uniquely safe, caring, healing, mutually supportive, and built on a foundation of prevailing concern for the other’s wellbeing. Some of these contrasts are subtle and understated. Consider, for instance, how Hannah observes that Rebecca looks like she hasn’t slept in days because of the turmoil of her entanglements with Peter, whereas Jamie’s narration describes how Dani gets the best sleep of her life during the first night that she and Jamie spend together. Note, too, the editing work in Episode 6 that fades in and out between the memories of the destructive ramifications of Henry and Charlotte’s affair and the scenes of tender progression in Dani and Jamie’s romance. Other contrasts, though, are far more overt. Of course, one of the most blatant examples (and most pertinent to this analysis) is the very fact that the ghosts of Viola, Peter, and Rebecca are striving to reclaim the people they love and the lives that they’ve lost by literally possessing the bodies and existences of the living.

The role of consent is an important factor in these ghostly possessions and serves as a further contrast with Dani and Jamie’s relationship. Peter and Rebecca frequently possess Miles and Flora without their consent—at times, even, when the children explicitly tell them to stop or, at the very least, to provide them with warnings beforehand. While inhabiting the children, Peter and Rebecca go on to harm them and put them at risk (e.g. Peter smokes cigarettes while in Miles’s body; Rebecca leaves Flora alone and unconscious on the grounds outside the manor) and to commit acts of violence against others (e.g. Peter pushes Hannah into the well, killing her; Peter and Rebecca together attack Dani and restrain her). The “It’s you, it’s me, it’s us,” conceit—with which living people can invite Bly’s ghosts to possess them, the mechanism by which Dani breaks the curse of Bly’s gravity well—is a case of dubious consent at best and abusive, violent control at worst. (“I didn’t agree,” Rebecca says after Peter leaves her body, releasing his “invited” possession of her at the very moment that the lake’s waters start to fill her lungs).

Against these selfish possessions and wrong kinds of love, Jamie and Dani’s love is defined by their selfless refusal to possess one another. A key characteristic of their courtship involves them expressing vulnerability in ways that invite the other to make their own decisions about whether to accept and how to proceed (or not proceed). As we discussed earlier, Dani and Jamie’s first kiss happens after Dani opens up about her guilt surrounding her ex-fiancé’s death. Pausing that kiss, Jamie checks, “You sure?” and only continues after Dani answers with a spoken yes. (Let’s also take this moment to appreciate Amelia Eve’s excellent, whispered “Thank fuck,” that isn’t included in Netflix’s subtitles). Even so, Dani frantically breaks away from her just moments later. But Jamie accepts this and doesn’t push Dani to continue, believing, in fact, that Dani has withdrawn precisely because Jamie has pushed too much already. A week later, Dani takes the initiative to advance their budding romance by inviting Jamie out for a drink—which Jamie accepts by, instead, taking Dani to see her blooming moonflowers that very evening. There, in her own moment of vulnerability, Jamie shares her heart-wrenching and tumultuous backstory with Dani in order to “skip to the end” and spare Dani the effort of getting to know her. By openly sharing these difficult details about herself, Jamie evidently intends to provide Dani with information that would help her decide for herself whether she wants to continue their relationship or not.

Their shared refusal to possess reaches its ultimate culmination in that moment, all those years later, when Dani discovers just how close she’s come to strangling Jamie—and then leaves their home to travel all the way back to Bly and drown herself in the lake because she could “not risk her most important thing, her most important person.” Upon waking to find that Dani has left, Jamie immediately sets off to follow her back to Bly. And in an absolutely heartbreaking, beautiful scene, we see Jamie attempting the “you, me, us,” invitation, desperate for Dani to possess her, for Dani to take Jamie with her. (Y’all, I know I’m critiquing this scene right now, but I also fuckin’ love it, okay? Ugh. The sight of Jamie screaming into the water and helplessly grasping for Dani is gonna stay with me forever. brb while I go cry about it again). Dani, of course, refuses this plea. Because “Dani wouldn’t. Dani would never.” Further emphasizing the nobility of Dani’s actions, Jamie’s narration also reveals that Dani’s self-sacrificial death has not only spared Jamie alone, but has also enabled Dani to take the place of the Lady of the Lake and thereby ensure that no one else can be taken and possessed by Viola’s gravity well ever again.

And so we have the show’s ennoblement of Dani’s magnanimous self-sacrifice. By inviting Viola to possess her, drowning herself to keep from harming Jamie, and then refusing to possess Jamie or anyone else, Dani has effectively saved everyone: the children, the restive souls that have been trapped at Bly, anyone else who may ever come to Bly in the future, and the woman she loves most. Dani has also, then, broken the perpetuation of Bly’s cycles of possession and trauma with her selfless expression of love for Jamie.

The unfortunate effect of all of this is that, quite without meaning to (I think? I hope—), The Haunting of Bly Manor ends up stumbling headlong into a validation of suicide as a selfless act of true love, as a force of protection and salvation.

So, before we proceed, I just want to take this moment to say—definitively, emphatically, as someone who has survived and experienced firsthand the ineffably catastrophic consequences of suicide—that suicide is nothing remotely resembling a selfless “refusal to possess” or an act of love. I’m not going to harp extensively on this, though, because I’d rather not trigger myself for a second time (so far, lol) while writing this essay. Just take my fuckin’ word for it. And before anybody tries to hit me with some excuse like “But Squall, it isn’t that the show is valorizing suicide, it’s that Dani is literally protecting Jamie from Viola,” please consider that I’ve already discussed how the show’s depiction of this lent itself to my own noxious beliefs that “all I do is harm other people with my grief, so maybe I should stop talking to my friends so that they don’t have to deal with me anymore.” Please consider what these narrative details and their allegorical import might tell people who are struggling with their mental health—even if not with suicidal ideation, then with the notion that they should self-sacrificially remove themselves from relationships for the sake of sparing loved ones from (assumed) harm.

Okay, that said, now let’s proceed…‘cause I’ve got even more to say, ‘cause the more I mulled over these details, the more I also came to realize that Dani’s self-sacrificial death in Bly’s conclusion also has the unfortunate effect of undermining some of its other (attempted) themes and its queer representation.

What Bly Manor Tries (and Fails) to Say about Grief and Acceptance

Let’s start by jumping back to a theme we’ve already addressed briefly: moving through one’s grief.

The Haunting of Bly Manor does, in fact, have a lot to say about this. Or…it wants to, more like. On the whole, it seems like it’s trying really hard to give us a cautionary tale about the destructive effects of unprocessed grief and the misplaced guilt that we can wind up carrying around when someone we love dies. The show spends a whole lot of time preaching about how important it is that we learn to accept our losses without allowing them to totally consume us—or without lingering around in denial about them (gettin’ some Kübler-Ross in here, y’all). Sadly, though, it does kind of a half-assed job of it…despite the fact that this is a major recurring theme and a component of the characterizations and storylines of, like, most of its characters. In fact, this fundamentally Kübler-Rossian understanding of what it means to move through grief and to accept loss and mortality appears to be the show’s guiding framework. During his rehearsal dinner speech in the first episode, Owen proclaims that, “To truly love another person is to accept that the work of loving them is worth the pain of losing them,” with such eerie resonance—as the camera stays set on Jamie’s unwavering gaze—that we know that what we’re about to experience is a story about accepting the inevitable losses of the people we love.