#cohere prompt engineering

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Prompt Engineering से पैसे कमाएँ |Unique way to earn money online..

Prompt Engineering : online सफलता के लिए प्रभावी Prompt डिज़ाइन करना | Online संचार के तेजी से विकसित हो रहे परिदृश्य में, Prompt Engineering एक महत्वपूर्ण कौशल के रूप में उभरी है, जो जुड़ाव बढ़ाने, बहुमूल्य जानकारी देने और यहां तक ��कि डिजिटल इंटरैक्शन का मुद्रीकरण करने का मार्ग प्रशस्त कर रही है। यह लेख Prompt Engineering की दुनिया पर गहराई से प्रकाश डालता है, इसके महत्व, सीखने के सुलभ…

View On WordPress

#advanced prompt engineering#ai prompt engineering#ai prompt engineering certification#ai prompt engineering course#ai prompt engineering jobs#an information-theoretic approach to prompt engineering without ground truth labels#andrew ng prompt engineering#awesome prompt engineering#brex prompt engineering guide#chat gpt prompt engineering#chat gpt prompt engineering course#chat gpt prompt engineering jobs#chatgpt prompt engineering#chatgpt prompt engineering course#chatgpt prompt engineering for developers#chatgpt prompt engineering guide#clip prompt engineering#cohere prompt engineering#deep learning ai prompt engineering#deeplearning ai prompt engineering#deeplearning.ai prompt engineering#entry level prompt engineering jobs#free prompt engineering course#github copilot prompt engineering#github prompt engineering#github prompt engineering guide#gpt 3 prompt engineering#gpt prompt engineering#gpt-3 prompt engineering#gpt-4 prompt engineering

0 notes

Text

Jatan Shah Skill Nation | limitless uses of ChatGPT

The limitless uses of ChatGPT are only possible through its appropriate advanced prompt engineering techniques. Once you have learned how to create well-articulated, relevant and coherent prompts, you can turn Chat GPT to great use in accomplishing any of your objectives.

#jatan shah reviews#jatan shah skill nation reviews#jatan shah skill nation#jatan shah#skill nation reviews#skill nation student reviews#coherent prompts#advanced prompt engineering#uses of ChatGPT

0 notes

Text

On a blustery spring Thursday, just after midterms, I went out for noodles with Alex and Eugene, two undergraduates at New York University, to talk about how they use artificial intelligence in their schoolwork. When I first met Alex, last year, he was interested in a career in the arts, and he devoted a lot of his free time to photo shoots with his friends. But he had recently decided on a more practical path: he wanted to become a C.P.A. His Thursdays were busy, and he had forty-five minutes until a study session for an accounting class. He stowed his skateboard under a bench in the restaurant and shook his laptop out of his bag, connecting to the internet before we sat down.

Alex has wavy hair and speaks with the chill, singsong cadence of someone who has spent a lot of time in the Bay Area. He and Eugene scanned the menu, and Alex said that they should get clear broth, rather than spicy, “so we can both lock in our skin care.” Weeks earlier, when I’d messaged Alex, he had said that everyone he knew used ChatGPT in some fashion, but that he used it only for organizing his notes. In person, he admitted that this wasn’t remotely accurate. “Any type of writing in life, I use A.I.,” he said. He relied on Claude for research, DeepSeek for reasoning and explanation, and Gemini for image generation. ChatGPT served more general needs. “I need A.I. to text girls,” he joked, imagining an A.I.-enhanced version of Hinge. I asked if he had used A.I. when setting up our meeting. He laughed, and then replied, “Honestly, yeah. I’m not tryin’ to type all that. Could you tell?”

OpenAI released ChatGPT on November 30, 2022. Six days later, Sam Altman, the C.E.O., announced that it had reached a million users. Large language models like ChatGPT don’t “think” in the human sense—when you ask ChatGPT a question, it draws from the data sets it has been trained on and builds an answer based on predictable word patterns. Companies had experimented with A.I.-driven chatbots for years, but most sputtered upon release; Microsoft’s 2016 experiment with a bot named Tay was shut down after sixteen hours because it began spouting racist rhetoric and denying the Holocaust. But ChatGPT seemed different. It could hold a conversation and break complex ideas down into easy-to-follow steps. Within a month, Google’s management, fearful that A.I. would have an impact on its search-engine business, declared a “code red.”

Among educators, an even greater panic arose. It was too deep into the school term to implement a coherent policy for what seemed like a homework killer: in seconds, ChatGPT could collect and summarize research and draft a full essay. Many large campuses tried to regulate ChatGPT and its eventual competitors, mostly in vain. I asked Alex to show me an example of an A.I.-produced paper. Eugene wanted to see it, too. He used a different A.I. app to help with computations for his business classes, but he had never gotten the hang of using it for writing. “I got you,” Alex told him. (All the students I spoke with are identified by pseudonyms.)

He opened Claude on his laptop. I noticed a chat that mentioned abolition. “We had to read Robert Wedderburn for a class,” he explained, referring to the nineteenth-century Jamaican abolitionist. “But, obviously, I wasn’t tryin’ to read that.” He had prompted Claude for a summary, but it was too long for him to read in the ten minutes he had before class started. He told me, “I said, ‘Turn it into concise bullet points.’ ” He then transcribed Claude’s points in his notebook, since his professor ran a screen-free classroom.

Alex searched until he found a paper for an art-history class, about a museum exhibition. He had gone to the show, taken photographs of the images and the accompanying wall text, and then uploaded them to Claude, asking it to generate a paper according to the professor’s instructions. “I’m trying to do the least work possible, because this is a class I’m not hella fucking with,” he said. After skimming the essay, he felt that the A.I. hadn’t sufficiently addressed the professor’s questions, so he refined the prompt and told it to try again. In the end, Alex’s submission received the equivalent of an A-minus. He said that he had a basic grasp of the paper’s argument, but that if the professor had asked him for specifics he’d have been “so fucked.” I read the paper over Alex’s shoulder; it was a solid imitation of how an undergraduate might describe a set of images. If this had been 2007, I wouldn’t have made much of its generic tone, or of the precise, box-ticking quality of its critical observations.

Eugene, serious and somewhat solemn, had been listening with bemusement. “I would not cut and paste like he did, because I’m a lot more paranoid,” he said. He’s a couple of years younger than Alex and was in high school when ChatGPT was released. At the time, he experimented with A.I. for essays but noticed that it made easily noticed errors. “This passed the A.I. detector?” he asked Alex.

When ChatGPT launched, instructors adopted various measures to insure that students’ work was their own. These included requiring them to share time-stamped version histories of their Google documents, and designing written assignments that had to be completed in person, over multiple sessions. But most detective work occurs after submission. Services like GPTZero, Copyleaks, and Originality.ai analyze the structure and syntax of a piece of writing and assess the likelihood that it was produced by a machine. Alex said that his art-history professor was “hella old,” and therefore probably didn’t know about such programs. We fed the paper into a few different A.I.-detection websites. One said there was a twenty-eight-per-cent chance that the paper was A.I.-generated; another put the odds at sixty-one per cent. “That’s better than I expected,” Eugene said.

I asked if he thought what his friend had done was cheating, and Alex interrupted: “Of course. Are you fucking kidding me?”

As we looked at Alex’s laptop, I noticed that he had recently asked ChatGPT whether it was O.K. to go running in Nike Dunks. He had concluded that ChatGPT made for the best confidant. He consulted it as one might a therapist, asking for tips on dating and on how to stay motivated during dark times. His ChatGPT sidebar was an index of the highs and lows of being a young person. He admitted to me and Eugene that he’d used ChatGPT to draft his application to N.Y.U.—our lunch might never have happened had it not been for A.I. “I guess it’s really dishonest, but, fuck it, I’m here,” he said.

“It’s cheating, but I don’t think it’s, like, cheating,” Eugene said. He saw Alex’s art-history essay as a victimless crime. He was just fulfilling requirements, not training to become a literary scholar.

Alex had to rush off to his study session. I told Eugene that our conversation had made me wonder about my function as a professor. He asked if I taught English, and I nodded.

“Mm, O.K.,” he said, and laughed. “So you’re, like, majorly affected.”

I teach at a small liberal-arts college, and I often joke that a student is more likely to hand in a big paper a year late (as recently happened) than to take a dishonorable shortcut. My classes are small and intimate, driven by processes and pedagogical modes, like letting awkward silences linger, that are difficult to scale. As a result, I have always had a vague sense that my students are learning something, even when it is hard to quantify. In the past, if I was worried that a paper had been plagiarized, I would enter a few phrases from it into a search engine and call it due diligence. But I recently began noticing that some students’ writing seemed out of synch with how they expressed themselves in the classroom. One essay felt stitched together from two minds—half of it was polished and rote, the other intimate and unfiltered. Having never articulated a policy for A.I., I took the easy way out. The student had had enough shame to write half of the essay, and I focussed my feedback on improving that part.

It’s easy to get hung up on stories of academic dishonesty. Late last year, in a survey of college and university leaders, fifty-nine per cent reported an increase in cheating, a figure that feels conservative when you talk to students. A.I. has returned us to the question of what the point of higher education is. Until we’re eighteen, we go to school because we have to, studying the Second World War and reducing fractions while undergoing a process of socialization. We’re essentially learning how to follow rules. College, however, is a choice, and it has always involved the tacit agreement that students will fulfill a set of tasks, sometimes pertaining to subjects they find pointless or impractical, and then receive some kind of credential. But even for the most mercenary of students, the pursuit of a grade or a diploma has come with an ancillary benefit. You’re being taught how to do something difficult, and maybe, along the way, you come to appreciate the process of learning. But the arrival of A.I. means that you can now bypass the process, and the difficulty, altogether.

There are no reliable figures for how many American students use A.I., just stories about how everyone is doing it. A 2024 Pew Research Center survey of students between the ages of thirteen and seventeen suggests that a quarter of teens currently use ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the figure from 2023. OpenAI recently released a report claiming that one in three college students uses its products. There’s good reason to believe that these are low estimates. If you grew up Googling everything or using Grammarly to give your prose a professional gloss, it isn’t far-fetched to regard A.I. as just another productivity tool. “I see it as no different from Google,” Eugene said. “I use it for the same kind of purpose.”

Being a student is about testing boundaries and staying one step ahead of the rules. While administrators and educators have been debating new definitions for cheating and discussing the mechanics of surveillance, students have been embracing the possibilities of A.I. A few months after the release of ChatGPT, a Harvard undergraduate got approval to conduct an experiment in which it wrote papers that had been assigned in seven courses. The A.I. skated by with a 3.57 G.P.A., a little below the school’s average. Upstart companies introduced products that specialized in “humanizing” A.I.-generated writing, and TikTok influencers began coaching their audiences on how to avoid detection.

Unable to keep pace, academic administrations largely stopped trying to control students’ use of artificial intelligence and adopted an attitude of hopeful resignation, encouraging teachers to explore the practical, pedagogical applications of A.I. In certain fields, this wasn’t a huge stretch. Studies show that A.I. is particularly effective in helping non-native speakers acclimate to college-level writing in English. In some STEM classes, using generative A.I. as a tool is acceptable. Alex and Eugene told me that their accounting professor encouraged them to take advantage of free offers on new A.I. products available only to undergraduates, as companies competed for student loyalty throughout the spring. In May, OpenAI announced ChatGPT Edu, a product specifically marketed for educational use, after schools including Oxford University, Arizona State University, and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business experimented with incorporating A.I. into their curricula. This month, the company detailed plans to integrate ChatGPT into every dimension of campus life, with students receiving “personalized” A.I. accounts to accompany them throughout their years in college.

But for English departments, and for college writing in general, the arrival of A.I. has been more vexed. Why bother teaching writing now? The future of the midterm essay may be a quaint worry compared with larger questions about the ramifications of artificial intelligence, such as its effect on the environment, or the automation of jobs. And yet has there ever been a time in human history when writing was so important to the average person? E-mails, texts, social-media posts, angry missives in comments sections, customer-service chats—let alone one’s actual work. The way we write shapes our thinking. We process the world through the composition of text dozens of times a day, in what the literary scholar Deborah Brandt calls our era of “mass writing.” It’s possible that the ability to write original and interesting sentences will become only more important in a future where everyone has access to the same A.I. assistants.

Corey Robin, a writer and a professor of political science at Brooklyn College, read the early stories about ChatGPT with skepticism. Then his daughter, a sophomore in high school at the time, used it to produce an essay that was about as good as those his undergraduates wrote after a semester of work. He decided to stop assigning take-home essays. For the first time in his thirty years of teaching, he administered in-class exams.

Robin told me he finds many of the steps that universities have taken to combat A.I. essays to be “hand-holding that’s not leading people anywhere.” He has become a believer in the passage-identification blue-book exam, in which students name and contextualize excerpts of what they’ve read for class. “Know the text and write about it intelligently,” he said. “That was a way of honoring their autonomy without being a cop.”

His daughter, who is now a senior, complains that her teachers rarely assign full books. And Robin has noticed that college students are more comfortable with excerpts than with entire articles, and prefer short stories to novels. “I don’t get the sense they have the kind of literary or cultural mastery that used to be the assumption upon which we assigned papers,” he said. One study, published last year, found that fifty-eight per cent of students at two Midwestern universities had so much trouble interpreting the opening paragraphs of “Bleak House,” by Charles Dickens, that “they would not be able to read the novel on their own.” And these were English majors.

The return to pen and paper has been a common response to A.I. among professors, with sales of blue books rising significantly at certain universities in the past two years. Siva Vaidhyanathan, a professor of media studies at the University of Virginia, grew dispirited after some students submitted what he suspected was A.I.-generated work for an assignment on how the school’s honor code should view A.I.-generated work. He, too, has decided to return to blue books, and is pondering the logistics of oral exams. “Maybe we go all the way back to 450 B.C.,” he told me.

But other professors have renewed their emphasis on getting students to see the value of process. Dan Melzer, the director of the first-year composition program at the University of California, Davis, recalled that “everyone was in a panic” when ChatGPT first hit. Melzer’s job is to think about how writing functions across the curriculum so that all students, from prospective scientists to future lawyers, get a chance to hone their prose. Consequently, he has an accommodating view of how norms around communication have changed, especially in the internet age. He was sympathetic to kids who viewed some of their assignments as dull and mechanical and turned to ChatGPT to expedite the process. He called the five-paragraph essay—the classic “hamburger” structure, consisting of an introduction, three supporting body paragraphs, and a conclusion—“outdated,” having descended from élitist traditions.

Melzer believes that some students loathe writing because of how it’s been taught, particularly in the past twenty-five years. The No Child Left Behind Act, from 2002, instituted standards-based reforms across all public schools, resulting in generations of students being taught to write according to rigid testing rubrics. As one teacher wrote in the Washington Post in 2013, students excelled when they mastered a form of “bad writing.” Melzer has designed workshops that treat writing as a deliberative, iterative process involving drafting, feedback (from peers and also from ChatGPT), and revision.

“If you assign a generic essay topic and don’t engage in any process, and you just collect it a month later, it’s almost like you’re creating an environment tailored to crime,” he said. “You’re encouraging crime in your community!”

I found Melzer’s pedagogical approach inspiring; I instantly felt bad for routinely breaking my class into small groups so that they could “workshop” their essays, as though the meaning of this verb were intuitively clear. But, as a student, I’d have found Melzer’s focus on process tedious—it requires a measure of faith that all the work will pay off in the end. Writing is hard, regardless of whether it’s a five-paragraph essay or a haiku, and it’s natural, especially when you’re a college student, to want to avoid hard work—this is why classes like Melzer’s are compulsory. “You can imagine that students really want to be there,” he joked.

College is all about opportunity costs. One way of viewing A.I. is as an intervention in how people choose to spend their time. In the early nineteen-sixties, college students spent an estimated twenty-four hours a week on schoolwork. Today, that figure is about fifteen, a sign, to critics of contemporary higher education, that young people are beneficiaries of grade inflation—in a survey conducted by the Harvard Crimson, nearly eighty per cent of the class of 2024 reported a G.P.A. of 3.7 or higher—and lack the diligence of their forebears. I don’t know how many hours I spent on schoolwork in the late nineties, when I was in college, but I recall feeling that there was never enough time. I suspect that, even if today’s students spend less time studying, they don’t feel significantly less stressed. It’s the nature of campus life that everyone assimilates into a culture of busyness, and a lot of that anxiety has been shifted to extracurricular or pre-professional pursuits. A dean at Harvard remarked that students feel compelled to find distinction outside the classroom because they are largely indistinguishable within it.

Eddie, a sociology major at Long Beach State, is older than most of his classmates. He graduated high school in 2010, and worked full time while attending a community college. “I’ve gone through a lot to be at school,” he told me. “I want to learn as much as I can.” ChatGPT, which his therapist recommended to him, was ubiquitous at Long Beach even before the California State University system, which Long Beach is a part of, announced a partnership with OpenAI, giving its four hundred and sixty thousand students access to ChatGPT Edu. “I was a little suspicious of how convenient it was,” Eddie said. “It seemed to know a lot, in a way that seemed so human.”

He told me that he used A.I. “as a brainstorm” but never for writing itself. “I limit myself, for sure.” Eddie works for Los Angeles County, and he was talking to me during a break. He admitted that, when he was pressed for time, he would sometimes use ChatGPT for quizzes. “I don’t know if I’m telling myself a lie,” he said. “I’ve given myself opportunities to do things ethically, but if I’m rushing to work I don’t feel bad about that,” particularly for courses outside his major.

I recognized Eddie’s conflict. I’ve used ChatGPT a handful of times, and on one occasion it accomplished a scheduling task so quickly that I began to understand the intoxication of hyper-efficiency. I’ve felt the need to stop myself from indulging in idle queries. Almost all the students I interviewed in the past few months described the same trajectory: from using A.I. to assist with organizing their thoughts to off-loading their thinking altogether. For some, it became something akin to social media, constantly open in the corner of the screen, a portal for distraction. This wasn’t like paying someone to write a paper for you—there was no social friction, no aura of illicit activity. Nor did it feel like sharing notes, or like passing off what you’d read in CliffsNotes or SparkNotes as your own analysis. There was no real time to reflect on questions of originality or honesty—the student basically became a project manager. And for students who use it the way Eddie did, as a kind of sounding board, there’s no clear threshold where the work ceases to be an original piece of thinking. In April, Anthropic, the company behind Claude, released a report drawn from a million anonymized student conversations with its chatbots. It suggested that more than half of user interactions could be classified as “collaborative,” involving a dialogue between student and A.I. (Presumably, the rest of the interactions were more extractive.)

May, a sophomore at Georgetown, was initially resistant to using ChatGPT. “I don’t know if it was an ethics thing,” she said. “I just thought I could do the assignment better, and it wasn’t worth the time being saved.” But she began using it to proofread her essays, and then to generate cover letters, and now she uses it for “pretty much all” her classes. “I don’t think it’s made me a worse writer,” she said. “It’s perhaps made me a less patient writer. I used to spend hours writing essays, nitpicking over my wording, really thinking about how to phrase things.” College had made her reflect on her experience at an extremely competitive high school, where she had received top grades but retained very little knowledge. As a result, she was the rare student who found college somewhat relaxed. ChatGPT helped her breeze through busywork and deepen her engagement with the courses she felt passionate about. “I was trying to think, Where’s all this time going?” she said. I had never envied a college student until she told me the answer: “I sleep more now.”

Harry Stecopoulos oversees the University of Iowa’s English department, which has more than eight hundred majors. On the first day of his introductory course, he asks students to write by hand a two-hundred-word analysis of the opening paragraph of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.” There are always a few grumbles, and students have occasionally walked out. “I like the exercise as a tone-setter, because it stresses their writing,” he told me.

The return of blue-book exams might disadvantage students who were encouraged to master typing at a young age. Once you’ve grown accustomed to the smooth rhythms of typing, reverting to a pen and paper can feel stifling. But neuroscientists have found that the “embodied experience” of writing by hand taps into parts of the brain that typing does not. Being able to write one way—even if it’s more efficient—doesn’t make the other way obsolete. There’s something lofty about Stecopoulos’s opening-day exercise. But there’s another reason for it: the handwritten paragraph also begins a paper trail, attesting to voice and style, that a teaching assistant can consult if a suspicious paper is submitted.

Kevin, a third-year student at Syracuse University, recalled that, on the first day of a class, the professor had asked everyone to compose some thoughts by hand. “That brought a smile to my face,” Kevin said. “The other kids are scratching their necks and sweating, and I’m, like, This is kind of nice.”

Kevin had worked as a teaching assistant for a mandatory course that first-year students take to acclimate to campus life. Writing assignments involved basic questions about students’ backgrounds, he told me, but they often used A.I. anyway. “I was very disturbed,” he said. He occasionally uses A.I. to help with translations for his advanced Arabic course, but he’s come to look down on those who rely heavily on it. “They almost forget that they have the ability to think,” he said. Like many former holdouts, Kevin felt that his judicious use of A.I. was more defensible than his peers’ use of it.

As ChatGPT begins to sound more human, will we reconsider what it means to sound like ourselves? Kevin and some of his friends pride themselves on having an ear attuned to A.I.-generated text. The hallmarks, he said, include a preponderance of em dashes and a voice that feels blandly objective. An acquaintance had run an essay that she had written herself through a detector, because she worried that she was starting to phrase things like ChatGPT did. He read her essay: “I realized, like, It does kind of sound like ChatGPT. It was freaking me out a little bit.”

A particularly disarming aspect of ChatGPT is that, if you point out a mistake, it communicates in the backpedalling tone of a contrite student. (“Apologies for the earlier confusion. . . .”) Its mistakes are often referred to as hallucinations, a description that seems to anthropomorphize A.I., conjuring a vision of a sleep-deprived assistant. Some professors told me that they had students fact-check ChatGPT’s work, as a way of discussing the importance of original research and of showing the machine’s fallibility. Hallucination rates have grown worse for most A.I.s, with no single reason for the increase. As a researcher told the Times, “We still don’t know how these models work exactly.”

But many students claim to be unbothered by A.I.’s mistakes. They appear nonchalant about the question of achievement, and even dissociated from their work, since it is only notionally theirs. Joseph, a Division I athlete at a Big Ten school, told me that he saw no issue with using ChatGPT for his classes, but he did make one exception: he wanted to experience his African-literature course “authentically,” because it involved his heritage. Alex, the N.Y.U. student, said that if one of his A.I. papers received a subpar grade his disappointment would be focussed on the fact that he’d spent twenty dollars on his subscription. August, a sophomore at Columbia studying computer science, told me about a class where she was required to compose a short lecture on a topic of her choosing. “It was a class where everyone was guaranteed an A, so I just put it in and I maybe edited like two words and submitted it,” she said. Her professor identified her essay as exemplary work, and she was asked to read from it to a class of two hundred students. “I was a little nervous,” she said. But then she realized, “If they don’t like it, it wasn’t me who wrote it, you know?”

Kevin, by contrast, desired a more general kind of moral distinction. I asked if he would be bothered to receive a lower grade on an essay than a classmate who’d used ChatGPT. “Part of me is able to compartmentalize and not be pissed about it,” he said. “I developed myself as a human. I can have a superiority complex about it. I learned more.” He smiled. But then he continued, “Part of me can also be, like, This is so unfair. I would have loved to hang out with my friends more. What did I gain? I made my life harder for all that time.”

In my conversations, just as college students invariably thought of ChatGPT as merely another tool, people older than forty focussed on its effects, drawing a comparison to G.P.S. and the erosion of our relationship to space. The London cabdrivers rigorously trained in “the knowledge” famously developed abnormally large posterior hippocampi, the part of the brain crucial for long-term memory and spatial awareness. And yet, in the end, most people would probably rather have swifter travel than sharper memories. What is worth preserving, and what do we feel comfortable off-loading in the name of efficiency?

What if we take seriously the idea that A.I. assistance can accelerate learning—that students today are arriving at their destinations faster? In 2023, researchers at Harvard introduced a self-paced A.I. tutor in a popular physics course. Students who used the A.I. tutor reported higher levels of engagement and motivation and did better on a test than those who were learning from a professor. May, the Georgetown student, told me that she often has ChatGPT produce extra practice questions when she’s studying for a test. Could A.I. be here not to destroy education but to revolutionize it? Barry Lam teaches in the philosophy department at the University of California, Riverside, and hosts a popular podcast, Hi-Phi Nation, which applies philosophical modes of inquiry to everyday topics. He began wondering what it would mean for A.I. to actually be a productivity tool. He spoke to me from the podcast studio he built in his shed. “Now students are able to generate in thirty seconds what used to take me a week,” he said. He compared education to carpentry, one of his many hobbies. Could you skip to using power tools without learning how to saw by hand? If students were learning things faster, then it stood to reason that Lam could assign them “something very hard.” He wanted to test this theory, so for final exams he gave his undergraduates a Ph.D.-level question involving denotative language and the German logician Gottlob Frege which was, frankly, beyond me.

“They fucking failed it miserably,” he said. He adjusted his grading curve accordingly.

Lam doesn’t find the use of A.I. morally indefensible. “It’s not plagiarism in the cut-and-paste sense,” he argued, because there’s technically no original version. Rather, he finds it a potential waste of everyone’s time. At the start of the semester, he has told students, “If you’re gonna just turn in a paper that’s ChatGPT-generated, then I will grade all your work by ChatGPT and we can all go to the beach.”

Nobody gets into teaching because he loves grading papers. I talked to one professor who rhapsodized about how much more his students were learning now that he’d replaced essays with short exams. I asked if he missed marking up essays. He laughed and said, “No comment.” An undergraduate at Northeastern University recently accused a professor of using A.I. to create course materials; she filed a formal complaint with the school, requesting a refund for some of her tuition. The dustup laid bare the tension between why many people go to college and why professors teach. Students are raised to understand achievement as something discrete and measurable, but when they arrive at college there are people like me, imploring them to wrestle with difficulty and abstraction. Worse yet, they are told that grades don’t matter as much as they did when they were trying to get into college—only, by this point, students are wired to find the most efficient path possible to good marks.

As the craft of writing is degraded by A.I., original writing has become a valuable resource for training language models. Earlier this year, a company called Catalyst Research Alliance advertised “academic speech data and student papers” from two research studies run in the late nineties and mid-two-thousands at the University of Michigan. The school asked the company to halt its work—the data was available for free to academics anyway—and a university spokesperson said that student data “was not and has never been for sale.” But the situation did lead many people to wonder whether institutions would begin viewing original student work as a potential revenue stream.

According to a recent study from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, human intellect has declined since 2012. An assessment of tens of thousands of adults in nearly thirty countries showed an over-all decade-long drop in test scores for math and for reading comprehension. Andreas Schleicher, the director for education and skills at the O.E.C.D., hypothesized that the way we consume information today—often through short social-media posts—has something to do with the decline in literacy. (One of Europe’s top performers in the assessment was Estonia, which recently announced that it will bring A.I. to some high-school students in the next few years, sidelining written essays and rote homework exercises in favor of self-directed learning and oral exams.)

Lam, the philosophy professor, used to be a colleague of mine, and for a brief time we were also neighbors. I’d occasionally look out the window and see him building a fence, or gardening. He’s an avid amateur cook, guitarist, and carpenter, and he remains convinced that there is value to learning how to do things the annoying, old-fashioned, and—as he puts it—“artisanal” way. He told me that his wife, Shanna Andrawis, who has been a high-school teacher since 2008, frequently disagreed with his cavalier methods for dealing with large learning models. Andrawis argues that dishonesty has always been an issue. “We are trying to mass educate,” she said, meaning there’s less room to be precious about the pedagogical process. “I don’t have conversations with students about ‘artisanal’ writing. But I have conversations with them about our relationship. Respect me enough to give me your authentic voice, even if you don’t think it’s that great. It’s O.K. I want to meet you where you’re at.”

Ultimately, Andrawis was less fearful of ChatGPT than of the broader conditions of being young these days. Her students have grown increasingly introverted, staring at their phones with little desire to “practice getting over that awkwardness” that defines teen life, as she put it. A.I. might contribute to this deterioration, but it isn’t solely to blame. It’s ��a little cherry on top of an already really bad ice-cream sundae,” she said.

When the school year began, my feelings about ChatGPT were somewhere between disappointment and disdain, focussed mainly on students. But, as the weeks went by, my sense of what should be done and who was at fault grew hazier. Eliminating core requirements, rethinking G.P.A., teaching A.I. skepticism—none of the potential fixes could turn back the preconditions of American youth. Professors can reconceive of the classroom, but there is only so much we control. I lacked faith that educational institutions would ever regard new technologies as anything but inevitable. Colleges and universities, many of which had tried to curb A.I. use just a few semesters ago, rushed to partner with companies like OpenAI and Anthropic, deeming a product that didn’t exist four years ago essential to the future of school.

Except for a year spent bumming around my home town, I’ve basically been on a campus for the past thirty years. Students these days view college as consumers, in ways that never would have occurred to me when I was their age. They’ve grown up at a time when society values high-speed takes, not the slow deliberation of critical thinking. Although I’ve empathized with my students’ various mini-dramas, I rarely project myself into their lives. I notice them noticing one another, and I let the mysteries of their lives go. Their pressures are so different from the ones I felt as a student. Although I envy their metabolisms, I would not wish for their sense of horizons.

Education, particularly in the humanities, rests on a belief that, alongside the practical things students might retain, some arcane idea mentioned in passing might take root in their mind, blossoming years in the future. A.I. allows any of us to feel like an expert, but it is risk, doubt, and failure that make us human. I often tell my students that this is the last time in their lives that someone will have to read something they write, so they might as well tell me what they actually think.

Despite all the current hysteria around students cheating, they aren’t the ones to blame. They did not lobby for the introduction of laptops when they were in elementary school, and it’s not their fault that they had to go to school on Zoom during the pandemic. They didn’t create the A.I. tools, nor were they at the forefront of hyping technological innovation. They were just early adopters, trying to outwit the system at a time when doing so has never been so easy. And they have no more control than the rest of us. Perhaps they sense this powerlessness even more acutely than I do. One moment, they are being told to learn to code; the next, it turns out employers are looking for the kind of “soft skills” one might learn as an English or a philosophy major. In February, a labor report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reported that computer-science majors had a higher unemployment rate than ethnic-studies majors did—the result, some believed, of A.I. automating entry-level coding jobs.

None of the students I spoke with seemed lazy or passive. Alex and Eugene, the N.Y.U. students, worked hard—but part of their effort went to editing out anything in their college experiences that felt extraneous. They were radically resourceful.

When classes were over and students were moving into their summer housing, I e-mailed with Alex, who was settling in in the East Village. He’d just finished his finals, and estimated that he’d spent between thirty minutes and an hour composing two papers for his humanities classes. Without the assistance of Claude, it might have taken him around eight or nine hours. “I didn’t retain anything,” he wrote. “I couldn’t tell you the thesis for either paper hahhahaha.” He received an A-minus and a B-plus.

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Authors Can Use AI to Improve Their Writing Style

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming the way authors approach writing, offering tools to refine style, enhance creativity, and boost productivity. By leveraging AI writing assistant authors can improve their craft in various ways.

1. Grammar and Style Enhancement

AI writing tools like Grammarly, ProWritingAid, and Hemingway Editor help authors refine their prose by correcting grammar, punctuation, and style inconsistencies. These tools offer real-time suggestions to enhance readability, eliminate redundancy, and maintain a consistent tone.

2. Idea Generation and Inspiration

AI can assist in brainstorming and overcoming writer’s block. Platforms like OneAIChat, ChatGPT and Sudowrite provide writing prompts, generate story ideas, and even suggest plot twists. These AI systems analyze existing content and propose creative directions, helping authors develop compelling narratives.

3. Improving Readability and Engagement

AI-driven readability analyzers assess sentence complexity and suggest simpler alternatives. Hemingway Editor, for example, highlights lengthy or passive sentences, making writing more engaging and accessible. This ensures clarity and impact, especially for broader audiences.

4. Personalizing Writing Style

AI-powered tools can analyze an author's writing patterns and provide personalized feedback. They help maintain a consistent voice, ensuring that the writer’s unique style remains intact while refining structure and coherence.

5. Research and Fact-Checking

AI-powered search engines and summarization tools help authors verify facts, gather relevant data, and condense complex information quickly. This is particularly useful for non-fiction writers and journalists who require accuracy and efficiency.

Conclusion

By integrating AI into their writing process, authors can enhance their style, improve efficiency, and foster creativity. While AI should not replace human intuition, it serves as a valuable assistant, enabling writers to produce polished and impactful content effortlessly.

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Tossing my prompt request out to the wind for Steter : Stiles breaks Peter out of Eichen house

Oh, man, I love this concept, and entire novel length stories have been written on it. 100-300 words is just going to feel sad next to that, but here’s a bit of an Eichen House breakout anyway. 😀

-

Peter’s not coherent when it happens.

The drugs the Eichen House staff pump into his veins are bad enough, but they also make consistently avoiding Valack’s gaze impossible. Peter’s not thinking clearly enough to figure out when to turn, to close his eyes, to lash out. Occasionally, Valack catches him and he’s plunged into disjointed visions of flames and family and past mistakes.

Ultimately, all Peter has is a collage of sensations: Blood blooming against a concrete wall. The thud of Valack’s body tipping over. A scent, faintly medicinal but familiar. His feet scuffing through powder, but not ash. A rush of air. The crinkle of a tarp. Stiles’s voice, casual and friendly even though he stinks of anxiety.

After that, the rumble of an engine and the hum of wheels over asphalt soothe Peter to sleep.

When he wakes, he’s on an air mattress in an unfamiliar garage. It smells musty. The scent of bacon drifts towards him, so he climbs to his feet and looks around, finding the door into the house and heading that way.

The rest of the house smells musty, too. No one has used this place in years. But the lights are on, and Peter can hear Stiles in the kitchen. When he spots Peter, Stiles looks relieved. “Oh, good, you’re awake. It’s been two days. I was starting to wonder if I was going to regret dragging you to the middle of nowhere.”

“Why help me?” Peter asks.

Stiles is silent for a long time. Peter waits. “Because you’re the only person who ever consistently took me seriously,” he says eventually. “And I’m done playing comic relief.”

That is… not the answer Peter expected. Compassion would have been his guess, given Stiles’s own experiences with Eichen.

He finds he likes this reason better.

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Game Reactions: Out of the Fold & Other Games (x4 playing card TTRPGs)

Link: https://ratwave.square.site/product/out-of-the-fold-and-other-games/62?cp=true&sa=true&sbp=false&q=false

This is one of the books I picked up at UKGE 2025, from Kayla Dice of Rat Wave Game House. It contains four separate games, all using a deck of regular playing cards, among a couple of other tools. Kayla is behind Transgender Deathmatch Legend II, which also uses primarily a deck of regular playing cards. I’m a big of fan of using playing cards. Tarot decks are quite popular within TTRPGs, especially solo ones, for obvious reasons. I enjoy tarot decks, but I’ve got such strong memories of playing cards with my family as a kid, there’s a real nostalgia to handling a deck. On top of that, they’re a nice size to hold and having a hand of cards gives you a constant tactile connection to the game, as well as a fun stim toy honestly.

Each game has its own vibe and aesthetics within the book, but there’s a consistency maintained throughout. As a collection, the games show an abundance of ways to use cards - even a single game can use them in multiple ways.

Out of the Fold

The title game is a GM-less story of magicians escaping from the secret society that trained them. Classes are represented by the face cards and jokers. Players meet a series of obstacles to their escape. Each one has a level of poker hand required to beat it, with escalate in difficulty.

Players collaborate to play cards into a central hand that forms the spell (poker hand) required to beat the obstacle. I got Balatro vibes as I was reading, and sure enough it was shouted out as a big inspiration. The game has great flavour, and I love using poker hands for the mechanics. This one seems fun and I’ll be keen to play it.

Save Our Souls

This has an incredible premise: the players all traded their souls to a dark power in exchange for something, and they’re going on a heist to the underworld to steal them back. It’s so fucking cool.

It’s a hack of Steal the Throne by Nick Bate, which I know of but haven’t read or played. The group sets up the dark power and their domain together. There’s a structure to this, but I wonder whether more prompts and mechanisation would be a benefit. Though with a creative group, I think you could have a lot of fun coming up with some wild stuff here.

From there, players rotate roles between the thieves, the dark power itself, and saviours, who can have a variety of impacts on the process. It’s a really cool engine for some outrageous stories. There’s a lot asked of all the players in terms of generating interesting obstacles and other elements of the world though. I’d suggest finding the best group of weirdos you know to play with, and you’ll probably have a great time.

Once again, we are defeated

A map-making game about a village that is going to be attacked, so the villagers persuade a group of skilled outsiders to defend them. Every premise in this book is just great.

To start with, players create the village, ensuring they’re hopefully invested in its safety. To do this you pull cards which link to prompts. After, you create the outsiders and their motivations - I really felt like you could go melodramatic and ham it up here, really have some fun with it.

The premise is strong enough that the game gets to be genre agnostic and still feel coherent and like it has a voice. This means you could get quite a bit of replay doing different genres, settings, and tones.

Planning the defense is achieved by taking roles of the outsider, a nay-sayer, and a judge. This is a structured debate on the merits of the defensive idea, with the judge determining the chances of success (which has a mechanical impact later). It’s a nice setup, and the game even gives you an additional optional process for the argument, to more structure if that feels better.

From here, you resolve the attack on the village and see the ending. There absolutely will be heavy losses, and the fate of the village as a whole is precarious. Vibes are good, and I think it’s a type of story that is easy for a lot of people to latch onto.

Illustrator’s Guide to the Dreamtlands

The last game is a solo journaling and sketching journey through a surreal landscape. You have an actual flask of coffee and a real tea light, which factor into the game as you play. Playing cards are used mainly for prompts in this one.

Each spread in the book is one step of the journey, and contains one page of text and one that is entirely art. Combined with the coffee and the tea light, a lot of effort is being put into creating the right atmosphere, getting your mind in the right space to generate elements of this surreal land. Getting the right playlist for this would be good as well!

It’s a straightforward (as much as this kind of surreal thing can be straightforward) solo road trip from here, and I don’t want to spoil any specific elements. The quality of the prose is critical though, and it delivers here, it’s very evocative.

Overall

I’m a big fan of the book and all of these games. They’re all really creative, and as a whole they’re varied but still have a coherent and consistent voice to them. It’s also a bargain as a book, for four fully-realised games.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

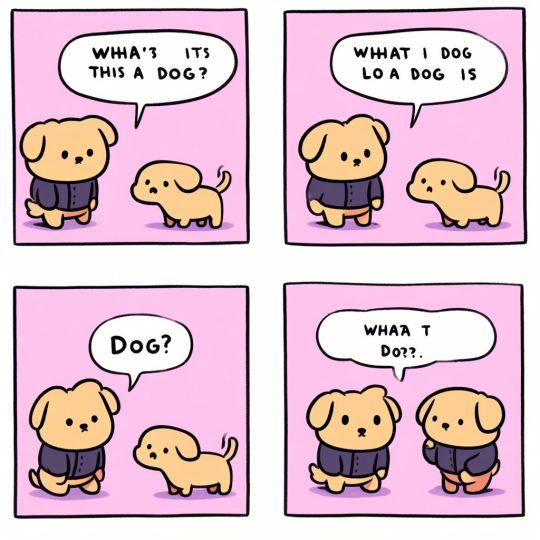

What is a Dog?

Playing around with Dall-E 3. It has some very impressive coherence but I think we're going to see the leapfrogging happen pretty quick.

But to play with that coherence, especially around text, I asked it to make me:

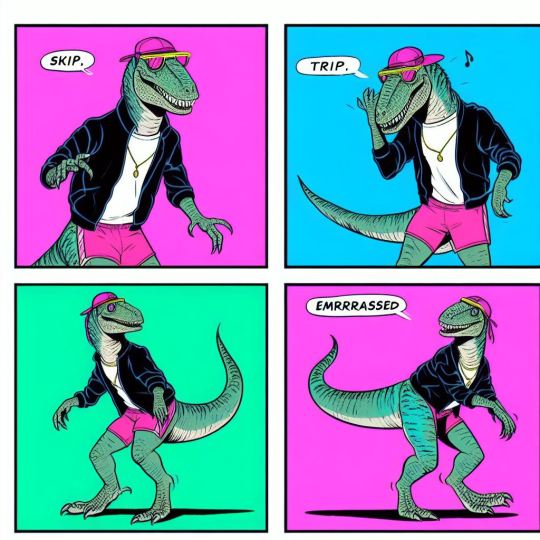

Prompt: a four-panel comic. a cute kid-sized velociraptor dinosaur trying to figure out what a dog is. Cute and quirky.

The results are beautifully surreal. Some examples in varying levels of weirdness:

This is the closest one to land near an actual idea (by chance, it's still a pareidolia engine), as our dinosaur seems to spot a dog, sees that there's both a dog and and anthro dog, and then has an existential crisis.

This cute little guy with the nostril-sized mouth is taken in by an inconsistent dog, but doesn't know what it does.

"is this a dog?" "What things' a dog?" "What's its quality?" AI's comin' for the anticomedy first.

Robot's like "screw the dinosaurs, I want to explore the Goofy/Pluto conundrum"

And this one's a different prompt entirely, but dang I love how it messed up here

(Prompt: a four-panel comic featuring a humanoid velociraptor in 80s clothing dancing, then tripping, and being embarrassed)

Skip, trip... emrrrrassed indeed.

These images are unmodified and were not adjusted with extensive iteration or other methods, as such they do not meet the minimum human creativity threshold, and are in the public domain,

#dall-e 3#ai experiments#comic strips#what is a dog#unreality#ai artwork#generative art#dogs#dinosaurs#public domain#public domain art

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

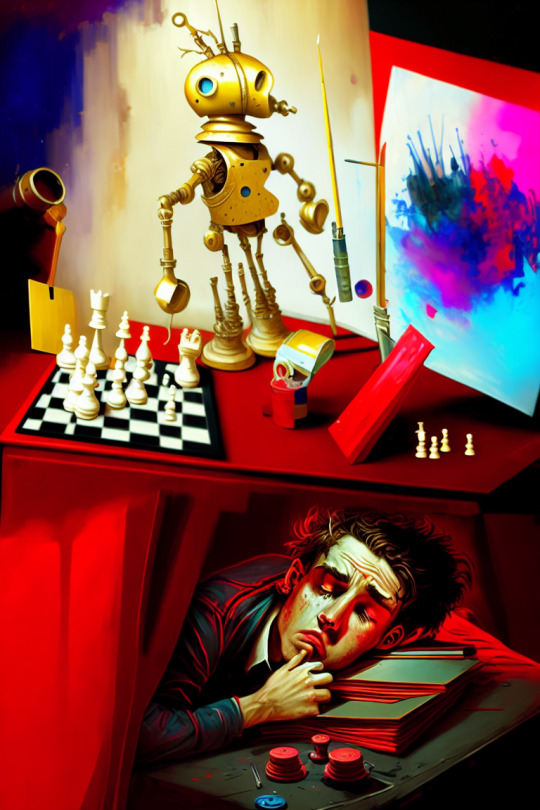

The AI Boom and the Mechanical Turk

A hidden, overworked man operating a painting, chess-playing robot, generated with the model Dreamlike Diffusion on Simple Stable, ~4 hours Created under the Code of Ethics of Are We Art Yet?

In 1770, an inventor named Wolfgang von Kempelen created a machine that astounded the world, a device that prompted all new understanding of what human engineering could produce: the Automaton Chess Player, also known as the Mechanical Turk. Not only could it play a strong game of chess against a human opponent, playing against and defeating many challengers including statesmen such as Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon Bonaparte, it could also complete a knight's tour, a puzzle where one must use a knight to visit each square on the board exactly once. It was a marvel of mechanical engineering, able to not only choose its moves, but move the pieces itself with its mechanical hands.

It was also a giant hoax.

What it was: genuinely a marvel of mechanical engineering, an impressively designed puppet that was able to manipulate pieces on a chessboard.

What it wasn't: an automaton of any kind, let alone one that could understand chess well enough to play at a human grandmaster's level. Instead, the puppet was manipulated by a human chess grandmaster hidden inside the stage setup.

So, here and now, in 2023, we have writers and actors on a drawn-out and much needed strike, in part because production companies are trying to "replace their labor with AI".

How is this relevant to the Mechanical Turk, you ask?

Because just like back then, what's being proposed is, at best, a massive exaggeration of how the proposed labor shift could feasibly work. Just as we had the technology then to create an elaborate puppet to move chess pieces, but not to make it choose its moves for itself or move autonomously, we have the technology now to help people flesh out their ideas faster than ever before, using different skill sets - but we DON'T have the ability to make the basic idea generation, the coherent outlining, nor the editing nearly as autonomous as the companies promising this future claim.

What AI models can do: Various things from expanding upon ideas given to them using various mathematical parameters and descriptions, keywords, and/or guide images of various kinds, to operating semi-autonomously as fictional characters, when properly directed and maintained (e.g., Neuro-sama).

What they can't do: Conceive an entire coherent movie or TV show and write a passable script - let alone scripts for an entire show - from start to finish without human involvement, generate images with a true complete lack of human involvement, act fully autonomously as characters, or...do MOST of the things such companies are trying to attribute to "AI (+unimportant nameless human we GUESS)", for that matter.

The distinction may sound small, but it is a critical one: the point behind this modern Mechanical Turk scam, after all, is that it allegedly eliminates human involvement, and thus the need to pay human employees, right...?

But it doesn't. It only enables companies to shift the labor to a hidden, even more underpaid sector, and even argue that they DESERVE to be paid so little once found out because "okay okay so it's not TOTALLY autonomous but the robot IS the one REALLY doing all the important work we swear!!"

It's all smoke and mirrors. A lie. A Mechanical Turk. Wrangling these algorithms into creating something truly professionally presentable - not just as a cash-grab gimmick that will be forgotten as soon as the novelty wears off - DOES require creativity and skill. It IS a time-consuming labor. It, like so many other uses of digital tools in creative spaces (e.g., VFX), needs to be recognized as such, for the protection of all parties involved, whether their role in the creative process is manual or tool-assisted.

So please, DO pay attention to the men behind the curtain.

#ai art#ai artwork#the clip linked to in particular? just another demonstration of how much work these things are

191 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think people immediately jump to conspiracy theories because we're just not used to seeing Lewis struggling with a car/not winning? Or is it more a nature of 2024 social media (or a combo of both).

Thank you so much for calling out the bullshit though, I was starting to feel like the only well-balanced Lewis fan on my dash.

I don't know these things are multifactorial and very complicated. Here are some factors I think may play into it from the top of my head.

Lewis has been pinned the victim since ad21 (imo rightfully) and I think some people are struggling to move past that. Now everything that happens that doesn't go his way is just a confirmation that people have it out for him. It made some level of sense early on (we saw how the sport at large reacted to the idea of his 8th title in dts in particular and many of them didn't make it a secret that they would rather he didn't win it) and now it's becoming harder and harder to find him a bully as we move away from the original event and so it's becoming more and more absurd. It was Masi's fault and then Max's and then George's and then Toto's and then the team's in general and now it's his own mechanics and engineers' or whatever... We're five minutes away from people saying Bono himself is sabotaging him. (Actually nevermind we're already past that he's been accused of not giving him the info he needed that one time George changed startegy or something like that.)

I do also see it as a trend for fans in general to try to make up story lines even when there might not be any. That might be in part due to dts but more generally to the fact that I believe a lot of people are watching F1 like a show rather than like a sport. Like I once said, this isn't Hollywood, stories in real life rarely wrap up definitively and prettily with a bow on top, there's no such thing as redemption arc, and because your fav has been done dirty at some point doesn't mean he's necessarily gonna come out on top afterwards to balance it out. There's no such thing as deserving a win or deserving a good car or deserving a proper farewell. Because it's not a story. It's reality. And reality is messy. But a lot of fans will rather weave a plot together to try to make it make sense to themselves and try to find that happy ending at all cost or try to explain why it's not a happy ending in any possible way that has a narrative rather than accepting that that's life at the end of the day. Which is human to some extent and we all do the same thing with our daily lives btw. It's a normal coping mechanism to put events together into something that resembles a coherent story even when that implies disregarding some parts of said events to make them fit together like we want them to.

I think a lot of Lewis fans (including me) are very frustrated with the way things have gone because it's truly annoying and it makes us more prompt to point fingers and try to make the problem simpler than it is by pinning it on someone or something specific because it's just easier to deal with that way than admit that F1 just like the real life that it is, is fucking complicated and "unfair" (in that no guaranteed happy ending way I described earlier).

And honestly that's fine I too vent my frustration during races and jump on things that make me tick and only afterwards think them through but the fact that Lewis has to make such a post to tell people that no, his team isn't sabotaging him, and that yes, he did relent to their tyre suggestion, shows that's it's been indubitably been taken way too far for everyone's comfort and his own first and foremost. And that's just honestly kinda embarrassing for us all imo.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some unfinished Proto RAM thoughts from last night

When Alastor dumps Vox’s body in the lobby of V Tower, there’s hardly anything left of him— just a bunch of wires/cables attached to a faintly beating synthetic heart, and once-body parts so mangled that they’re as good as scrap metal now.

The doctors/engineers try to get Vox to connect to a backup body he had on standby. Blind, disoriented, and operating only on instinct, Vox hooks in when prompted, only to freak out once the body powers on. Everything’s loud and bright and wrong wrong WRONG, and he immediately abandons the new body.

The team tries for days to find/create a body that Vox will actually stay in, but nothing works. He stays hidden inside his heart, unable to communicate or process the world around him. However, as the engineers work in vain, Vox begins to regenerate. The mass of wires slowly begin to knit together, reforming his original, rubbery body. Val, Vel, and the team are baffled, but have no choice but to let it happen as Vox rejects model after model.

Eventually, once Vox has formed enough of a body for it to be clear what’s happening, Velvette takes the initiative and presents Vox with an ancient, 1950s television set. He connects to it and, at last, doesn’t immediately flee. His (old) face appears on the screen and he regains his sensory capacities. Vox is confused when he wakes up on a work bench, surrounded by people he doesn’t recognize, but he can’t verbally express it; his audio is scrambled and he can’t make himself understood. Additionally, his body doesn’t have enough structural integrity to support his head, so he’s stuck on the bench, able to move his body, but not his head.

When Vox gets the okay to leave the repair room, Val has to carry him out. For the next couple weeks, Vox slowly regains his ability to walk and speak understandably. However, the whole time, Val was unknowingly digging his own grave. Vox was already completely disoriented in time, and having someone who looked not unlike his old overlord carry him like she once had was reinforcing the belief that he was actually back in her compound in the late 50s-early 60s. Once Vox could speak coherently again, Val was baffled, then horrified at the realization that Vox wholeheartedly believed he was some long-dead overlord. He hoped it was just a side effect of the old body, but when they resumed trying to get Vox to inhabit his updated body, they were just an unsuccessful as ever. It slowly became clear that Vox could not and would not abandon his old body, and whatever was going on with him mentally to make him act so strange would not be going away any time soon.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

lol nsfw text

part of the reason i'm focusing on the water shader now is uh one of the clarifying effects of messing around w/ ai art was "okay yes if i want some kind of desert scene i will definitely need oases and flooded ruins and all that kinda stuff". b/c i kept generating big monsters fucking in pools of oily black ichor.

i am still waffling on how pornographic i want to make this game, not the least b/c 24x36 pixel sprites are not exactly a good medium for sexual arousal, but the advantage a game has over other media is, like, the interactivity. you can choose to get yr character baptized in black slime and climb out the other side some kind of bizarre shadow monster. that's erotic!

(it's not really surprising, but when i started prompting the ai art it was like, oh right as i revise the prompts and focus down on a concept i want to express it's something that's full of uhhh lets say my own idiosyncrasies. there's a lot of humans being debased/transformed by groups of looming monsters in some kind of ecstatic religious ritual. okay okay i'll break the rule i just made and post one. lightly edited to remove the one visible dick.)

this was me just kind of noodling around thinking about the position of magic and weird monsters in the game setting, and if nothing else generating several dozen bits of monster porn along that theme did help clarify some of my thoughts there.

or like, the thing with the ai art is that even though all of it was muddy and indistinct it did make me a little... envious, i guess? in the sense of, i'm working on this game thing and that will never look like the bizarre lurid landscapes in the ai art. in fact, ai art is nothing but the most lurid signifiers you can throw at it; there's a reason why 'ai artists' just throw in boilerplate like 'exquisite composition; excellent visual detail; superb design'. meanwhile i'm limiting my visual design b/c i am not actually very good at art & i want to be able to make the entire thing all the way through, which means all the art needs to be art i'm capable of drawing. isometric 32-color pixel art is about as far away from that kind of lurid sensationalism as you can get.

but the ai art has its own drawbacks, such as, that it's pretty impossible to generate, like, setting? coherency? i gotta actually be responsible for ensuring coherency and structure in my little pixel art sprites. the ai art is just blobs of suggestive shape, whereas pixel art has to be clear

a game world has to be rigorous or else there's nothing there, & the one thing i can do is add things that can be rigorously simulated & presented. like water!! or coherent narratives for why anybody is doing anything. i mean it would be very funny to finish the lighting engine so i can have that kind of bright specular haloing/rim lighting effect, but, nothing that intense is in the cards for my pixel art game unfortunately.

i have been debating actually working on that 'the new hive' 1.2 patch tho. maybe add a weird ruined temple in there somewhere, that kind of thing. i've already decided i was gonna add the void shadow goatman (noktiĝo) to w/e patch, so maybe i should just do that. or water shader, or other fiction, or more fanfic, or more prompts... ultimately, i gotta pick a specific thing to work on or else i won't make any progress on anything, which is part of why i've been doggedly working on this game for nearly a year now. games take a lot of work! but ooof the sheer amount of work keeps hitting me. all this just for some dinky little thing that i don't even have a clear concept for. but i guess that's the fundamental uncertainly of making anything.

like, ai art does kinda hit me in the little of "why bother making anything", like, sure generative ai is no good at doing anything currently, but there is a bit of the invention of the photograph vs. realistic painters situation happening. the spectre of 'the perfect ai' looms: what does it look like if ai is good, and anybody can just have it generate endless novelty forever? so much of existence is about the friction of doing, the ways in which, well, you gotta slog away at a project for years, often times with dozens-to-hundreds of other people slogging away with you, in order to accomplish anything. what happens if that's no longer the case? so much of the business/management drive to put ai in everything has to do with them having never seen the value in making things; it's all just 'monetizable content' to them, & they're aiming for a world where they control the monetizable content taps themselves. that seems doomed to failure, but stupider things have happened. capital seems labor as a threat and wants to use the increasing automation provided by technology to freeze the shape of the world forever, with them frozen at the top forever. who can say if that's possible, but it's a vision people are working to enact. and with all that looming it's always been a little difficult to be like, here, here's my little game-thing! pinned under the gaze of the nightmarish world of authority and domination.

anyway i think i'm done messing w/ ai art generators. time to outline more of the water shader pipeline i guess!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Memory and Context: Giving AI Agents a Working Brain

For AI agents to function intelligently, memory is not optional—it’s foundational. Contextual memory allows an agent to remember past interactions, track goals, and adapt its behavior over time.

Memory in AI agents can be implemented through various strategies—long short-term memory (LSTM) for sequence processing, vector databases for semantic recall, or simple context stacks in LLM-based agents. These memory systems help agents operate in non-Markovian environments, where past information is crucial to decision-making.

In practical applications like chat-based assistants or automated reasoning engines, a well-structured memory improves coherence, task persistence, and personalization. Without it, AI agents lose continuity, leading to erratic or repetitive behavior.

For developers building persistent agents, the AI agents service page offers insights into modular design for memory-enhanced AI workflows.

Combine short-term and long-term memory modules—this hybrid approach helps agents balance responsiveness and recall.

Image Prompt: A conceptual visual showing an AI agent with layers representing short-term and long-term memory modules.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ask AI: Get Accurate, Useful Answers From Artificial Intelligence

Have you ever wished you could simply ask AI anything and get an instant, intelligent response? That future is not only here, but it's rapidly evolving, transforming how we access information, solve problems, and even create. The ability to ask AI has moved from science fiction to an indispensable daily tool, democratizing knowledge and empowering individuals across virtually every domain. In a world brimming with information, the challenge often isn't finding data, but sifting through it, understanding it, and extracting actionable insights. Traditional search engines provide links; conversational AI provides answers. This fundamental shift is what makes tools that allow us to ask AI so revolutionary. They act as a sophisticated bridge between complex data and human comprehension, solving problems ranging from mundane daily queries to intricate professional challenges. This comprehensive guide will delve into what it means to ask AI, why it has become such a pivotal technology, the profound problems it solves for its diverse users, and the leading platforms making this capability a reality. We'll explore practical applications, best practices for effective prompting, and even peek into the ethical considerations and exciting future of this transformative technology.

What Does It Mean to "Ask AI"?

At its core, to ask AI means to engage with an artificial intelligence system, typically a Large Language Model (LLM) or a similar generative AI, using natural language (like English, Spanish, or any other human language) to pose a question, request information, or issue a command. Unlike traditional computer interactions that often require precise syntax or keywords, modern AI systems are designed to understand and respond to the nuances of human speech and text. Imagine having a conversation with an incredibly knowledgeable expert who has processed a vast amount of the world's accessible information. You can inquire about historical events, request a poem, seek advice on a coding problem, or even brainstorm business ideas. The AI processes your input, analyzes its extensive training data, and then generates a coherent, relevant, and often highly insightful response. The Technology Under the Hood: More Than Just a Search Engine When you ask AI, you're interacting with a complex interplay of advanced artificial intelligence techniques, primarily: - Natural Language Processing (NLP): This is the AI's ability to understand, interpret, and generate human language. NLP allows the AI to decipher your query, recognize its intent, and extract key information. It's how the AI knows you're asking about "the capital of France" and not just the word "Paris." - Large Language Models (LLMs): These are the brains of modern conversational AI. LLMs are neural networks trained on colossal datasets of text and code (trillions of words and lines of code). Through this training, they learn patterns, grammar, facts, common sense, and even stylistic nuances of language. When you ask AI, the LLM predicts the most probable sequence of words to form a coherent and relevant answer based on its training. - Generative AI: This refers to the AI's capability to create new content, rather than just retrieve existing information. When you ask AI to write a story, generate code, or summarize an article, it's using its generative abilities to produce original output that aligns with your prompt. - Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF): Many advanced LLMs are fine-tuned using RLHF, where human evaluators provide feedback on the AI's responses. This process helps the AI learn what constitutes a helpful, accurate, and safe answer, making it more aligned with human expectations and values. This sophisticated technological foundation is what distinguishes simply searching for information from being able to ask AI to synthesize, explain, and create. It moves beyond keyword matching to a deeper understanding of context and intent. Why It Matters: A Paradigm Shift in Information Access and Productivity The ability to ask AI is more than just a convenience; it represents a significant paradigm shift with profound implications for individuals, businesses, and society as a whole. Its growing importance stems from several key factors: - Instantaneous Access to Synthesized Knowledge: In an age of information overload, the bottleneck isn't usually a lack of data, but the time and effort required to find, evaluate, and synthesize it. When you ask AI, you bypass this bottleneck. Instead of sifting through dozens of search results, you get a concise, organized, and often comprehensive answer almost instantly. This accelerates learning, decision-making, and problem-solving. - Democratization of Expertise: Specialized knowledge often resides behind paywalls, in academic journals, or requires years of study. While AI doesn't replace human experts, it can make a vast amount of specialized information more accessible to the average person. Need a simple explanation of quantum physics? Want to understand the basics of contract law? You can ask AI to provide an understandable overview, effectively democratizing access to complex concepts. - Personalized Learning and Support: Unlike static textbooks or generic online tutorials, AI can adapt its responses to your specific needs and level of understanding. You can ask AI to explain a concept in simpler terms, provide more examples, or even tutor you step-by-step through a problem. This personalized approach makes learning more efficient and engaging. - Boost in Productivity and Efficiency: From drafting emails and generating ideas to summarizing lengthy documents and writing basic code, the ability to ask AI to handle routine or time-consuming tasks frees up human cognitive resources. This dramatically boosts productivity for individuals and teams, allowing them to focus on higher-value, more creative, and strategic work. - Innovation and Creativity Catalyst: AI isn't just for factual queries. It can be a powerful creative partner. You can ask AI to brainstorm ideas for a novel, suggest plot twists, generate marketing taglines, or even compose music. It acts as a springboard for human creativity, pushing boundaries and sparking new ideas that might not have emerged otherwise. In essence, the power to ask AI is transforming how we interact with information and technology. It's shifting us from passive consumers of data to active collaborators with intelligent systems, unlocking new potentials for learning, productivity, and creative expression across almost every facet of life.

The Problems It Solves: Real-World Applications of "Ask AI"