#fallacies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

I think the constant -I’ve been bullied too, I didn’t turn like Snape- is interesting about the marauders fans, they used it so much to negate Severus’s trauma and surely to pat themselves on the back, because who else is going to do it? I don’t think they understand that if the marauders were real, the same people defending them would be their victims

It’s like when millionaires say, “I got rich, I wasn’t born rich,” as if that somehow disproves the existence of structural poverty. It’s a lucky exception fallacy, where you use your individual case to dismiss systemic realities, as if your personal success somehow cancels out the fact that the system is designed to keep most people from getting out of their circumstances. Basically, a shitty argumentative tactic.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

--

Q: What are the three most compelling arguments for the existence of gods - concise answer, name it if it has a formal name. And what are the most straightforward refutations of these arguments - concise answer.

Grok: Arguments for the Existence of Gods:

1. Cosmological Argument:

Description: The argument posits that everything that exists has a cause, and there must be a first cause or "uncaused cause" which is God.

Refutation: The universe might be eternal, negating the need for a first cause, or the cause could be an impersonal force rather than a personal deity.

2. Teleological Argument (or Design Argument):

Description: The complexity and apparent design of the universe suggest a designer, akin to how a watch implies a watchmaker.

Refutation: Complex structures can emerge from natural processes (evolution by natural selection), and the universe might not be precisely "designed" for life, considering most of the cosmos is hostile to it.

3. Ontological Argument:

Description: Proposed by Anselm, it argues that God is the greatest conceivable being; existence in reality is greater than existence in the mind alone, hence God must exist.

Refutation: Existence isn't necessarily a property that can be predicated in this manner; the argument might commit the fallacy of assuming that because something can be thought, it must exist.

Straightforward Refutations:

Cosmological: Challenges the necessity of a personal first cause by suggesting naturalistic explanations like the Big Bang or an eternal universe.

Teleological: Points out that apparent design can result from natural selection and physical laws without a designer.

Ontological: Criticizes the logic by arguing that "existence" isn't a property like "redness" or "largeness" that can be part of a definition.

These arguments and their refutations highlight the ongoing philosophical debate about the existence of deities, showing that each argument has its strengths but also faces significant challenges.

==

This is the best they've got.

#arguments for god#god existence#atheism#fallacies#cosmological argument#teleological argument#ontological argument#religion#religion is a mental illness

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

we live in a world where everyone believes in black and white, when everything is painted in gray. therefore, how can an ideal world be anything but a fallacy?

#writing#writers on tumblr#writers#writing community#writblr#writeblr#creative writing#poetry#original#poem#poems#poems on tumblr#poems and quotes#ideal world#idealism#fallacy#fallacies#black and white#gray#og writing#loss of hope

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate appeals to nature more than I hate other fallacies because they leave an implied "should", often times to things I don't want to do. "But it's natural to want (children, to be a mother, sex, to be pregnant, to be a homemaker etc.), it's part of (your biology/God's design)" Well no, not for everyone.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

overheard some interesting logic from a man on the bus today. first he said he convinced some guy that the bible is true by saying "it's been translated into over 600 languages, do you really think that many people would be lying about it??" then he said he told a woman who said she didn't believe in god because she couldn't see god that "you can't see the air, but you'd be dead without it!" (while this is completely useless as evidence in the whole existence of god question, it does directly address her stated reason for not believing in god, so he gets points for that i guess.) he also said that sasquatch must exist because canada has a law against shooting sasquatches. frankly i think it would have been more consistent for him to argue that sasquatch must exist because you can't see sasquatch, but whatever.

#does he know that translators can lie. i don't think that's the most relevant counterargument but i just really want to know#does he know translators are capable of falsehood#my posts#fallacies

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Luc Picard @SpaceDadSupport You are not obligated to continue social discussions with people who do not engage in good faith. You are allowed to walk away from fallacy-spouters, goalpost shifters, and others more interested in arguing than comprehending. 4:58 PM · Apr 17, 2024

#star trek#star trek the next generation#star trek memes#star trek tng#jean luc picard#support#captain picard#picard#affirmations#spacedad#kindness#what would picard do#fallacies#discussions#debate is not an argument#you are not the fuckface whisperer

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ad Hominem Fallacy

Patreon

#studyblr#notes#writing#writing notes#essay writing#debate#debating#fallacies#logical fallacies#writing fallacies#fallacies in debate#fallacies in writing#latin#latin words#ad hominem#english#research#researching#education#argumentative writing#argumentative essay

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

In a 1969 paper the American economist Harold Demsetz distinguished between two approaches to public policy: the “comparative” approach and the “nirvana” approach. The former presents the choice as being between imperfect real world arrangements, the latter between an ideal world and the existing arrangement. This is known as “nirvana fallacy”: the tendency to measure our proposed solutions against a perfect solution which doesn’t exist. In the real world, we often have to choose between the bad and the even worse. But the politician who uses the nirvana fallacy gains an easy rhetorical advantage. He can gesture towards his perfect world, attack the existing state of affairs for not living up to it, and accuse anyone who doesn’t accept the plausibility of perfection as being heartless, cynical or small-minded. The left has a particular weakness for the nirvana fallacy: its condemnations of capitalism or military actions are often made without reference to concrete alternatives, but to some unarticulated idea of, well, nirvana. As Thomas Sowell liked to say, the question is always “Compared to what?”.

Ian Leslie, Ten Useful Concepts

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sunk Cost Fallacy is weird because it's only a Fallacy if you continue and fail.

If you continue and win though, it becomes Survivorship Bias.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

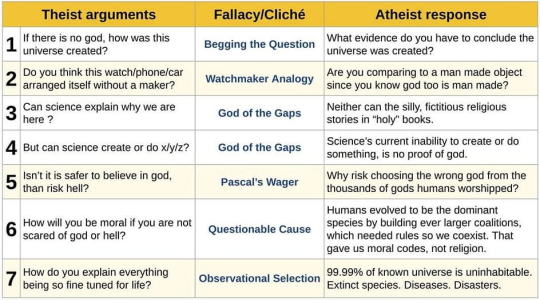

Do better than these, or don't bother.

PRATT: Points Refuted A Thousand Times.

#theist arguments#fallacies#begging the question#watchmaker analogy#god of the gaps#argument from ignorance#pascal's wager#questionable cause#PRATT#points refuted a thousand times#logical fallacies#religion#religion is a mental illness

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

"When you know nothing, you agree with everything."

This phrase came to my mind when I thought about how people who are not Christians (even the professing Christians) don't know things about Christianity, about Jesus Christ, about what is in the Holy Bible yet they just agree with others say because in their worldly wisdom, it makes sense but it couldn't be further from the truth. It's surprising to me how professing Christians, don't even know the Word of God, they don't know the truths it holds and because of that. . . they're led astray by different, demonic doctrines, opinions etc. They end up agreeing because in the end, they didn't even know.

#christianity#jesus christ#christian#christblr#christian faith#jesus#christian doctrine#spiritual enlightment#faith in jesus#demonic doctrines#heresies#fallacies#delusions#indoctrinated thoughts

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fallacies

Readers of this post, what’s your favourite fallacy?

Let me know in the reposts or replies.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I love how they are comparing her solely to those who arrived after her. they can't make their dumb point without erasing thousands of cis women.

really shows these people don't want the crowd to think "real" women can be more successful.

85K notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Jerry Coyne

Published: Dec 30, 2024

Not long ago I mentioned that The Free Press had published a weird piece extolling religion: an atheist beefing that she really missed the goddy parts of Christmas even though she wasn’t a believer. She needed to go to church. With that, I wondered whether softness on religion was becoming part of anti-wokeness, or at least that news site.

Now, with the publication of a new longer piece, The Free Press has buttressed my speculations. For this article not only names and tells the stories of a number of notables who decided to embrace religion (largely Christianity), but also implies that there are good reasons for them to do so. Mostly it’s the “God-shaped hole in our being”: the dubious idea that humans have an innate—and perhaps evolved—need to find a divine being to worship and give then succor. Indeed, several people (including Ayaan Hirsi Ali, whose embrace of Christianity we’ve discussed before) explicitly mention that religion is what gives their life meaning.

If that is the case, good for them. But of course many of us find meaning and purpose without religion. Indeed, as I’ve argued, people often don’t go out looking for meaning and purpose to their lives, but simply enact their lives in a way that winds up giving them meaning and purpose. Those things can be found in children, family, friends, activities (be they physical, intellectual, or humanitarian) and so on.

The biggest issue with this article, though, is that it is completely devoid of any evidence for the truth of the tenets of religion. It’s touting faith as a balm for wounded souls, and, so the narrative goes, one should accept God to get cured–regardless of whether what you believe is true. Indeed, it quotes Andrew Sullivan on the advantage of not having to have good reasons to believe:

The question swirling around all the new believers was: Were they true believers? Or was their conversion mostly or entirely utilitarian—driven by a desire to push back against the forces of technology and secularism and wokeness and an increasingly militant Islam? Did they actually believe that Jesus Christ was the son of God and that he had died for our sins and was resurrected? Or did they think that was a nice story that we should tell ourselves because it encouraged people to treat each other better—because it was a kind of cultural bulwark? And did it really matter in the end? Andrew Sullivan, the writer and podcaster, suggested this might not be easy to answer. “The feeling”—of believing—“will vary,” Sullivan, a Catholic, told me. “Sometimes, there’s no feeling. Sometimes, you’re overwhelmed. The point really is to escape feeling as such—our emotions are not what prove anything.” “The genius of ritual is that it allows us not to articulate our feelings,” Sullivan said. “It allows us to express our faith through an act.”

Well, I don’t find that “genius”. If your faith depends on believing that Jesus died for our sins, was bodily resurrected, and then became the only route to Heaven, then you bloody well better have good reasons for thinking that. It was the achievement of New Atheism to show that peoples’ reasons are not good ones. If your eternal life (and its location) depends on believing the truths espoused by your faith, it’s salubrious to have chosen the right faith. But people don’t worry about that; they usually assume the faith they were taught as children.

[ Archive: https://archive.today/aKxkG ]

Here are the names in each of the “I found God” anecdotes. Excerpts are indented; bolding is mine:

1.) In the beginning, Matthew Crawford believed in nothing. “The question of God wasn’t even on the radar,” the best-selling author told me. . . . .“A lot of very thoughtful people who once believed reason and science could explain everything—why we’re here, what comes after we’re gone, what it all means—are now feeling a genuine hunger for something more,” he said. “There has to be a larger order that comprehends us and makes a demand on us,” Crawford added. “It’s clear that we can’t live without a sense of meaning beyond ourselves.”

Has to be? Why? And of course if you find “meaning and purpose” in things like friends, family, work, and avocation, then that is a “sense of meaning” that doesn’t need the supernatural.

2.) But something profound is happening. Instead of smirking at religion, some of our most important philosophers, novelists, and public intellectuals are now reassessing their contempt for it. They are wondering if they might have missed something. Religion, the historian Niall Ferguson told me, “provides ethical immunity to the false religions of Lenin and Hitler.”

Again, we are supposed to believe that these important intellectuals might have missed out by neglecting God. But the effects of religious belief give no evidence for the truth of its tenets.

3.) In February 2024, podcaster Joe Rogan, in a conversation about the sorry state of America’s youth with New York Jets quarterback Aaron Rodgers, said: “We need Jesus.” Not five years earlier, Rogan had hosted Richard Dawkins on his show and poked fun at Christians.

Why Jesus? Is there evidence that he was who he said he was, and that believing in Jesus is the only way to heaven? Maybe we need Muhammad or Buddha.

Anyway, many of us don’t need Jesus.

Note the swipe at Dawkins. The article makes fun of New Atheists throughout; it’s almost like that contempt was ripped from Pharyngula. There’s even a section called “The Rise and Fall of the New Atheists”. Well, New Atheists aren’t writing their books any more, as they’ve had their say, but the decline of faith in the Western world (not just the U.S.) is sufficient evidence that the anecdotes of this article go against a trend of decreasing religiosity.

4.) In April, the comedian Russell Brand—who has emerged in recent years as a voice of the counterculture and amassed an audience of more than 11 million on X—announced that he was about to be baptized. “I know a lot of people are cynical about the increasing interest in Christianity and the return to God but, to me, it’s obvious. As meaning deteriorates in the modern world, as our value systems and institutions crumble, all of us become increasingly aware that there is this eerily familiar awakening and beckoning figure that we’ve all known all our lives within us and around us. For me, it’s very exciting.”

It’s almost as if his social-media following validates his beliefs. And again, why Christianity? How does Brand, who I thought was smarter than this, know that Christianity is the religion with the “right” claims? Why not Islam or Judaism?

5.) In May, tech mogul Peter Thiel, who had espoused a vague spirituality and had been friends with the late French philosopher and religious thinker René Girard, came down unequivocally on the side of God. “God has some kind of a plan for history,” Thiel said, while being interviewed by a pastor at a former church. “Maybe it’s a hidden plan; it’s a secret plan. He has a plan for your life.” It was a remarkable moment: One of the gods of Silicon Valley, who had long argued that technology could cure death, was now saying that there was one true God, and that human beings were human—limited, mortal, at the mercy of larger forces.

How certain Thiel is about the existence of God! But what is his evidence? And what is this evidence of a “plan for history” and a “plan for your life”? Thiel is just making this stuff up, spinning his wheels.

6). Then in July, Elon Musk—the former “atheist hero,” the king of electric vehicles and space exploration, the champion of free expression—sat down with Jordan Peterson, the Canadian psychologist who has studied the intersection of religion and ideology, to discuss God. “I’m actually a big believer in the principles of Christianity,” Musk said. Soon after, Musk took to X to pronounce that “unless there is more bravery to stand up for what is fair and right, Christianity will perish.”

Note that Musk said he believes in the PRINCIPLES of Christianity, not the actual factual assertions of the faith. Do those beliefs include the principle that if you don’t except Jesus as your savior, you’re going to fry eternally? What about the principle that it’s okay to have slaves, so long as you don’t whip them too hard?

As for Jordan Peterson, what he believes about Christianity is so confused and incoherent that I cannot take his “religion” seriously.

There are more like this, includiong Paul Kingsnorth and Jordan Hall, but again, they are just conversion stories, and say nothing about the truth of Christianity. And for every believer cited I could dig up someone who either gave up faith or refused to adopt it, as shown by the growth of “nones” in America. If it’s a war of anecdotes, the nonbelievers win (see below).

But we’ve neglected the prize specimen of conversion, former atheist Ayaan Hirsi Ali. She was deeply depressed, and nothing worked to help her. Until she found Christianity.

7.) In 2022, she started to come around to the idea of Christianity, going to church, thinking, reading: Who was this Christian God? And what was the nature of one’s relationship with him? How did that change you? Then came Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, 2023. The attack was proof, like the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States, of everything she had long believed about Islam. She was horrified, but she was also amazed by the Israelis’ conviction. “What I find with my Jewish friends was this blind faith in Israel and the existence of Israel—there will be a Zionist movement, there will be a home for the Jewish people,” she said. “They are immersed in these biblical stories. It’s a story of faith.” In November of that year, Hirsi Ali published an essay, “Why I Am Now a Christian”—a response to Bertrand Russell—in UnHerd. “We can’t counter Islamism with purely secular tools,” she wrote. “To win the hearts and minds of Muslims here in the West, we have to offer them something more than videos on TikTok.” The essay triggered an avalanche of conversations in the independent media universe—including a book, which she is now working on, and a debate, in June, between Hirsi Ali and Dawkins in which she argued that Christianity is a bulwark against “the cult of power, Islamism.” The debate felt like a kind of bookend to the four horsemen meeting in Hitchens’s apartment in 2007.

Well, yes, Christianity could make you resist Islam (note that religion is being divisive here), and if it cured Hirsi Ali of her depression, then I won’t fault her for accepting it, so long as she believes its tenets, which she says she does. Here’s the debate between Dawkins and Hirsi Ali. The audience is clearly on Hirsi Ali’s side, but the existence of God can’t be decided by a vote, and of course atheists are generally seen with suspicion compared to lauded “people of faith”. I have always found it curious that it’s considered praise to say someone is a “person of faith”. It could just as well be said that that is a “person of delusion.”

youtube

Another argument for religion adduced in the piece is that religion inspired great art, including all the religious paintings before artists discovered apples and flowers, as well as cathedrals and great music. This is in fact true, for surely we would have no Notre Dame or Chartres without Christianity. (I’m not so sure about music and painting.) But again, Islam too has inspired fantastic architecture as in their many lovely mosques (e.g., the Taj Mahal), as well as painting, and music (well, until recently). But again, none of this attesta to the verity of the revelations given to Muhammad.

And let’s get back to Dawkins:

Dawkins underscored that he, like Sam Harris, is still very much an atheist. He did not see any contradiction in saying, as he had to Rachel Johnson on the Leading Britain’s Conversation (LBC) radio show, that he was “happy” with the number of Christians declining in Britain and that he “would not be happy if we lost all our cathedrals and our beautiful parish churches.” “The tendency you’re talking about,” he told me, alluding to Hirsi Ali, “is, I think, mostly people who don’t necessarily believe Jesus was the son of God or born of a virgin, or rose from the dead, but nevertheless think that Christianity is a good thing, that Christianity would benefit the world if more people believed it, that Christianity might be the sort of basis for a lot of what’s good about Western civilization.” And yet, Dawkins did admit he was worried about losing the world that had been bequeathed to us by Christianity. “If we substituted any alternative religion,” he said in his April interview, “that would be truly dreadful.” It wasn’t just about the danger of what was coming. It was about what we were losing, or might lose. “Some of the greatest music ever written is church music, music inspired by Christianity,” he told me, echoing Roger Scruton. J.S. Bach would never have composed his Mass in B Minor—with all those violins, cellos, sopranos, and tenors weaving together, pointing us toward the heavens—without the divine, he said. Nor would Dostoevsky, as Paul Kingsnorth said, have written The Brothers Karamazov had he not been a believer. Had the world not been changed in countless unbelievable ways by that art? Had that art not changed us? When I mentioned Dawkins’s distinction between cultural and theological Christianity to Kingsnorth, he said he thought Dawkins was deliberately sidestepping a deeper conversation about the nature of belief.

I can’t agree fully with Richard about Christianity having bequeathed us a world we want to live in. We can’t run the experiment, but what kind of world would we have if religion had never arisen? We wouldn’t have cathedrals, but perhaps rationality and science would have taken hold a lot earlier, and surely a lot fewer people would have died in the many religious wars. (They’re still dying in droves, by the way: Jew against Muslim, Sunni against Shia, and so on.)

All I know is that I can’t force myself to believe, to condition my life, on something like this unless I know it is true. And because I see no evidence for a God, much less for the truth of any religion, I cannot force myself to believe. I consider myself a cultural Jew, but my life wouldn’t be that much poorer if I was purely secular. It is very convenient that believers say they don’t need no stinkin’ evidence, for they get to believe and don’t have to explain why they believe beyond “it makes me feel good.” Like this, from Jonah Teller, a New York Catholic priest:

Father Jonah thought that a new fervor, a more authentic connection to the faith, was emerging out of the loneliness of the last few years. There was a “genuine happiness” that he could feel at Mass, “an excitement, a love.” It wasn’t that complicated in the end. It was, he said, a kind of turning away from a radical atomization. “The world many people have grown up in is one in which you have the ability to be your own God,” said Father Jonah. “You should have it simply because you want it, whatever it may be. Or not have it, and that can include your own existence—a rejection of simply being.” But the fact of our existence is a testament to God’s love for us, he said. “We are always wanted,” Father Jonah said. “We are always loved. This is the most important thing. God is not a mindfulness hack or a wellness exercise. It’s not—‘I found this ethical system that gets results, and therefore, I will choose it.’ It’s not a choice. It’s an encounter with an actual, personal love.”

Father Jonah’s evidence is this: we exist, therefore God, and not just God but the loving Christian god. Does God love the Covid virus and mosquitoes, too, which also exist?

I am not going to go into detail about how faith is declining throughout the West, but here are some data from the Gallup organization.

[ Source: U.S. Church Membership Falls Below Majority for First Time ]

[ Source: Have the 'Nones' hit a plateau? ]

[ Source: Catholics' Church Attendance Resumes Downward Slide ]

[ Source: About Three-in-Ten U.S. Adults Are Now Religiously Unaffiliated ]

[ Source: It’s Official: The “Nones”– People Who Profess No Religion–Are Now as Big as Catholics & Evangelicals in the United States ]

Look as you will, all you will find is a continuous decline in religion in America over the last 100 years. But it’s not just America: read the Wikipedia article “Decline of Christianity in the Western World.”

This trend, of course, is downplayed in the article, with only a brief mention about the increase in “nones” under the Hirsi Ali section, but that’s about it. Yet given this trend, in 200 years believers in America will be quite rare. Religion will never disappear, of course, but its decline has been discussed by Steve Pinker in his book Enlightenment Now. with religion adduced as an anti-Enlightenment force throughout history.

But why is the Free Press running pieces like this? I have no idea, and can guess only that Bari Weiss, the editor, is herself religious, a believing Jew. I would love to hear her discuss the reasons for her faith, and why she rejects Christianity as a personal religion. But I haven’t seen that.

ONE MORE POINT: To those who think that societies can’t function well without religion, I have a one-word response: Scandinavia.

==

"There's an inevitable trajectory. … Invariably it starts off 'my faith is true.' After about, I don't know, depends on the person, 10 minutes, 15 minutes, something really interesting will happen. The conversation will go from 'my belief is true' … to 'my faith is beneficial.' … This is the inevitable trajectory of every single conversation, period." -- Peter Boghossian

Funny how they always find a hole-shaped god to fit their "god-shaped hole."

#Jerry Coyne#The Free Press#atheism#no religion#leaving religion#fallacies#god existence claims#logical fallacies#evidence#no evidence for god#religion#religion is a mental illness

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Andrew Doyle

Published: Mar 13, 2025

The accusation of ‘dog whistling’ is one of the most common of activist tactics. The metaphor suggests that someone is disguising their objectionable views by sending signals that only the likeminded will register, much as human beings remain oblivious to the higher sound frequencies that dogs are able to hear. As an argumentative strategy, it must rank among the most infantile. It is the equivalent of saying: ‘I know you haven’t said the nasty thing, but I’m going to pretend that you secretly meant the nasty thing’. It is akin to when social justice activist Titania McGrath argued that J. K. Rowling’s chief tactic was ‘to not attack trans people in order to make it look as though she is not attacking trans people’.

Last September, Telegraph writer Oliver Brown referred to Blair Hamilton, a trans-identified goalkeeper for Sutton United Women, as a ‘biological male’. This happened to be a matter of fact, but that didn’t prevent Hamilton from making a complaint to the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) and claiming that the phrase ‘biological male’ was a ‘transphobic dog whistle’. Hamilton preferred the phrase ‘assigned male at birth’, even though his sex had been recorded at birth, not assigned. This was an attempt not only to compel speech, but to weaponise the regulations so that journalists would have to tell lies in deference to a belief-system they do not share. This week, IPSO thankfully ruled that news outlets are allowed to refer to men as men.

In any given month, one will find multiple opinion columns claiming that this or that politician is blowing whistles for their bigoted dogs. Consider an article from last Thursday’s New Republic entitled: ‘How to decode RFK Jr.’s dog whistle messages on the measles vaccine’. The writer could have simply provided evidence of Kennedy’s inconsistencies, or criticised the arguments that he had made and offer better ones. Instead, she insisted that RFK Jr. was not ‘changing his stance on vaccines so much as cloaking it in code words’.

This kind of amateur telepathy amounts to little more than calling someone a liar. While no-one is surprised when politicians twist the truth, it is always best to avoid any assumptions. Poor arguments will collapse under scrutiny irrespective of whether or not their proponents are sincere. In other words, you have nothing to lose in assuming that they are telling the truth, because if their ideas are weak they will soon be exposed, in spite of any bad intentions that might lie beneath the surface.

It is impossible not to notice that activists only ever seem to insist that their opponents are guilty of dog whistling. For instance, back when Boris Johnson was Mayor of London he had been accused of dog whistling to racists by mentioning Barack Obama’s part-Kenyan heritage. When the Guardian referred to Obama’s dual heritage in relation to an identical topic, there were no complaints whatsoever. Such selective outrage would suggest that – as the adage has it – if you can hear the whistle, you’re probably the dog.

Much of this can be ascribed to a desire to avoid debate at all costs, and it seems to be particularly common among those of a tribalistic nature. For example, while there are excellent liberal arguments against the DEI industry, many commentators are happy to dismiss them on the grounds that – as Slate magazine put it in January – opposition to DEI is ‘a dog whistle for unchecked racism and bias’. Similarly, while the defence of free speech is a cornerstone principle of liberalism, some left-wing commentators are determined to interpret it as the very opposite: a ‘dog whistle for the far right’.

Naturally, those called upon to defend indefensible positions will always resort to smears in lieu of actual arguments. When women make the case that their rights depend upon the recognition of the reality of biological sex, it’s no easy feat to explain why this is wrong and that men should be permitted access to their spaces. Similarly, most free speech sceptics are reluctant to accept the challenge of explaining why censorship is necessary. In both cases, it’s far easier simply dismiss the opposition’s arguments as mere smoke signals to their allies.

Like its close cousin ‘lived experience’, the phrase ‘dog whistle’ is a trick by which opposing views can be discredited without any need to present evidence or formulate a more persuasive case. Genuine bigots tend to be vocal about their views, and so the notion that they are all speaking in code makes little sense. Dog whistles don’t really exist, and we should stop taking seriously those hallucinating critics who are prone to hearing these voices in their heads.

==

"One oddity of the whole business of trying to hear dog-whistles is very basic: if you can hear the whistle, you must surely be the dog." -- Douglas Murray

#Andrew Doyle#dog whistle#dogwhistle#myths#activist tactics#sophistry#fallacies#logical fallacies#manipulation#religion is a mental illness

4 notes

·

View notes