#great operatic disasters

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@mercipourleslivres (at least I think it was her) recommended The Eldest Daughter In Law [Reborn] and I am reading it now and so so so so so good!

I highly recommend it.

Our FL was a dutiful wife in her last life but as she lay there dying from illness she realized none of it mattered - her in laws, birth family and husband all took her efforts for granted and never really showed any appreciation beyond politeness and now she’s dying they all calmly plan to marry in her half sister to her husband after she dies to continue the family running smoothly. Her husband doesn’t even come to see her much as she’s ill and seemingly has no issue with the plan of taking a new wife when his family and her birth family urge him showing she might as well be an interchangeable cog.

As she dies, bitter at her whole life wasted and her love and care and goodness wasted, she wakes up years before all of this. Her marriage is fairly new (they just had their first child) and she resolves to live this life for herself.

This novel is very much a slice of life with no huge drama (mostly). Why do I love it? It’s the realism that makes it relatable.

Unlike in a lot of these rebirth web novels, there is no huge villain or some grand vengeance she wants to seek. The people in the first life weren’t monsters, they were just self absorbed or poor communicators or driven by the values of the period. Her father isn’t some abusive monster, he’s just a man who didn’t pay much attention to her, the same as any of his daughters. Her sisters in law and brothers in law and parents in law didn’t hate her and make her life a misery, they just took her for granted and only cared for what she could do for them. Her husband (who she dies believing plans to marry her half sister) was always distant and emotionally uninvolved but polite and gentle and very capable in court. It’s not a Blossom situation where he was fooling around with the half sis or anything - he has no interest in her either.

The tragedy of FL’s first life isn’t some sort of grand operatic disaster but having spent her whole life surrounded and pouring out her love towards a bunch of polite strangers. But that is what makes it so real.

Her goals in the second life are also nothing grand - to live for herself and to make sure eg her brother has good life and doesn't meet with an accident and her half sister doesn't get to marry in etc. It's relatable.

Also, I am a sucker for second chance romances especially slowburns and this is such a good example. The ML's arc is so great because he was never a villain, he was just very much a man of his era who believed that a proper marriage is one where you fuck twice a month on specified dates and are courteous and barely talk and are at best remote acquaintances. Watching him slowly, oh so slowly, be drawn to his wife who is changing and distancing for reasons he cannot follow is so delicious. His pining for a woman who doesn't hate him but, other than family standing problems it would create, would not care if he fell down a well and died is DELICIOUS.

PS Points to this novel for not being explicit but still so bluntly portraying the discomfort and awkwardness of sex for both parties when you are supposed to do it to have children but barely know each other and are trying to be polite throughout.

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

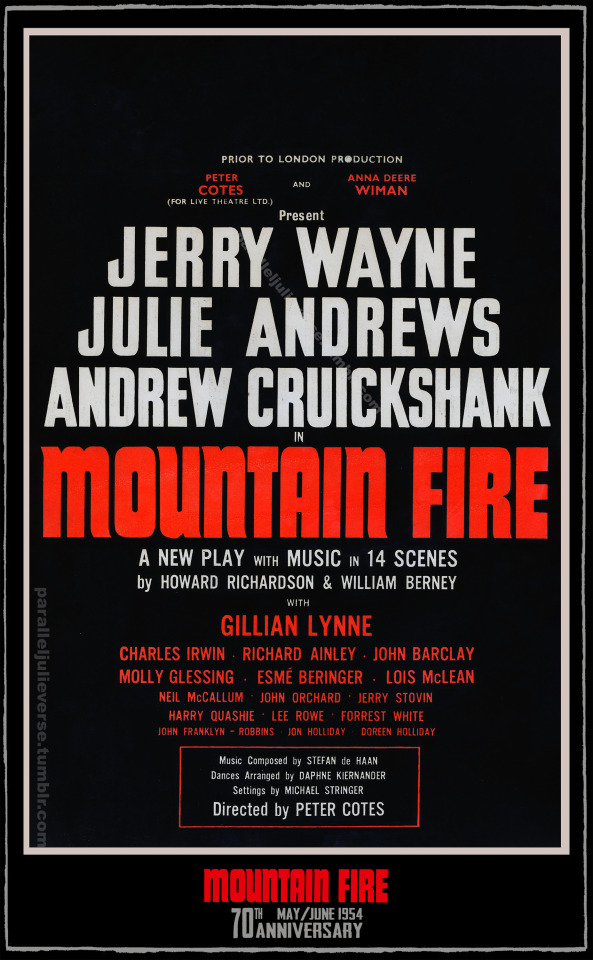

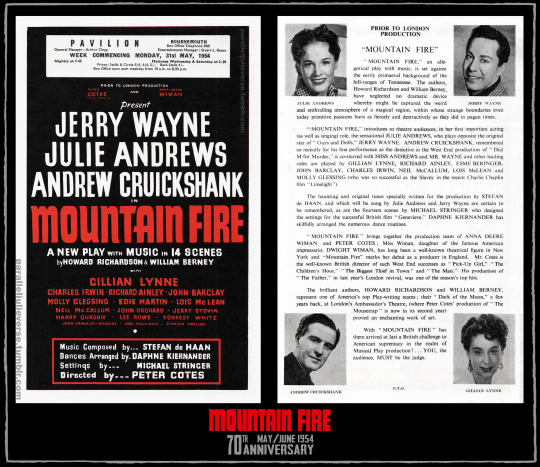

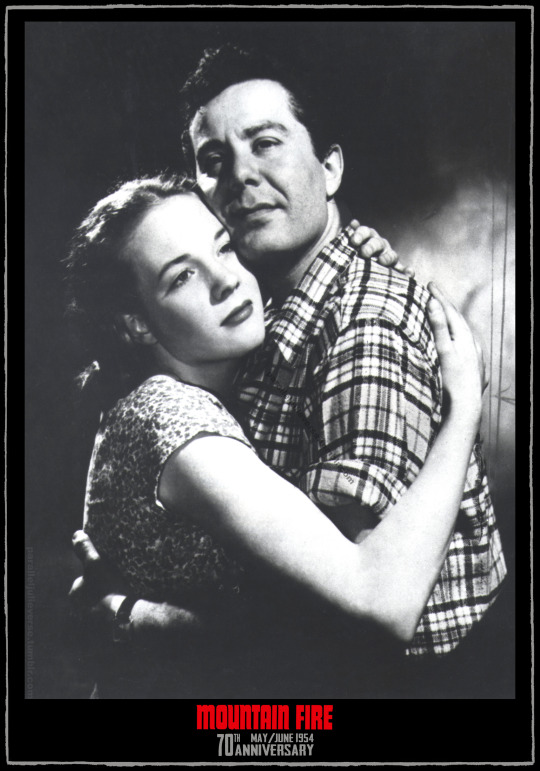

70th anniversary of Mountain Fire Liverpool / Leeds / Bournemouth / Birmingham 30 performances (18 May 1954 - 12 June 1954)

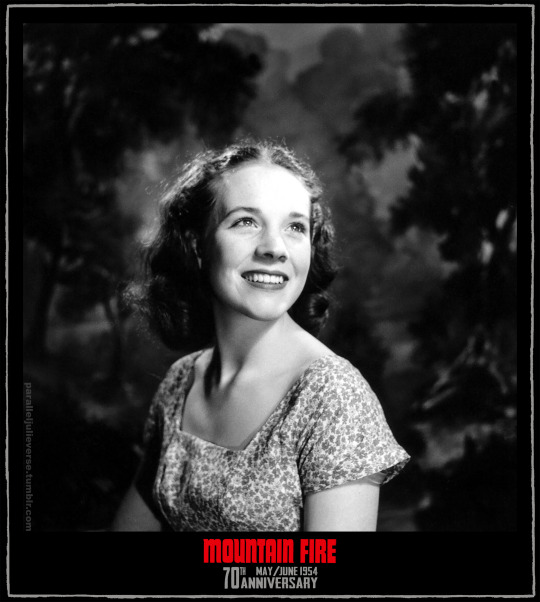

This month marks the 70th anniversary of a significant, if curious, milestone in the early career of Julie Andrews: her 'straight' theatrical debut in Richardson and Berney's Mountain Fire. A notorious flop, Mountain Fire lasted barely 30 performances in a month-long provincial tryout, closing ahead of a planned West End bow. The play would likely have sunk without a trace were it not for the fact that its female lead was on the cusp of international stardom.

While the ill-fated Mountain Fire was on the road, it was formally announced that Julie Andrews had been signed to helm the Broadway cast of The Boy Friend (Chit Chat 1954, p. 8; Mackenzie 1954, p. 4). The stark contrast between the disastrous failure of Mountain Fire and the star-making success of The Boy Friend has become part of the mythology of Julie Andrews' career. Even the Dame herself is fond of playing up the angle. "I had done one bomb in England," she recounts in a 1966 interview, "an incredible disaster...between Cinderella and The Boy Friend. I accepted a very limited engagement, thank God, and played a Southern belle from Tennessee...I can't tell you what went on. It was a disaster" (Newquist 1966, p. 141).

Four decades later in her 2008 memoirs, Julie was still cringing over the experience:

"The truth was, the play was not good, and although the company tried to make it work, we all sensed it was going to be a flop. I also knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that had the eminent London critic Kenneth Tynan seen my performance, it would have been the end of any career I hoped to have. Mercifully, Mountain Fire folded out of town" (Andrews 2008, 160).

Legitimate, at last!

Self-deprecatory humour aside, Julie actually received very good notices for her efforts in Mountain Fire. The Stage declared: "Julie Andrews scores a particularly fine dramatic success in her first serious portrayal, as the ill-starred Becky, bringing rare maturity to the difficult and exacting role" ('American folk play' 1954, p. 10). The Liverpool Echo similarly enthused: "Julie Andrews scores a personal triumph as the young girl and, in her first 'straight' role, reveals herself as accomplished an actress as she is a singer" (H.R.W. 1954, p. 5). The Yorkshire Evening Post opined: "Julie Andrews gives a beautiful and moving performance as the luckless Becky" (Bradbury 1954, p. 8). While the Bournemouth Daily Echo wrote: "Pretty Julie Andrews...does remarkably well and brings rare maturity and charm to the trying role" (G.Y. 1954, p. 6). Though the production might not have panned out as anticipated, Mountain Fire was a strategic step in Julie's ongoing pivot from child stardom to adult performer. Much was made in show publicity about Julie’s "graduation" from juvenile entertainment to mature dramatic fare:

"Brilliant stage and film children are always a little heartbreaking. So few of them amount to anything after they have reached the colt stage...One of the most happy exceptions is Julie Andrews--the once plain little girl with buck teeth, a slight squint and pigtails who astonished us all by singing operatic numbers in a sweet, clear coloratura when she had reached the ripe age of 12...Now, Julie is to make her debut as a straight actress in a new American play to be presented here by Peter Cotes...called Mountain Fire...Cotes says: 'Julie has a wonderful role and I believe her to be a young actress with great possibilities.'...[A]s she has both singing and dancing to do in her first straight play, this might well be the chance of a lifetime for grown-up Miss Andrews" (Frank 1954, 6).

'A hill-billy Bible story'

Mountain Fire couldn't have represented a more "grown-up" change for Julie. Billed as a "new play with music in 14 scenes", it was the latest offering from rising American playwrights -- and cousins -- Howard Richardson and William Berney. The pair had scored an early success with Dark of the Moon (1945), a fantasy verse play about witchcraft, love, and social intolerance in colonial-era Appalachia. They followed with a second collaboration, Design for a Stained Glass Window (1949) about religious persecution and martyrdom (Duncan 1966, p. S-7; Fisher 2021, p. 248-49).

Mountain Fire trod similarly heavy dramatic ground with a mix of religion, Southern Gothic stylings, and social commentary. Described by one critic as "a hill-billy Bible story", the play was an allegorical retelling of the Abrahamic legend of Sodom and Gomorrah with the "cities of the plains" transposed to "rival colonies of mountain dwellers" in the backwoods of eastern Tennessee (Mackenzie 1954, p. 4).

The scriptural elements of human wickedness and divine retribution were adapted into a laundry-list of stock Southern vices: a Hatfield-McCoy style feud, moonshine, teen pregnancy, arson, murder and, even, a Ku-Klux-Klan lynching ('New American Musical' 1954, p. 12). Punctuating this cavalcade of backwoods iniquity was a series of Greek choric tableaux where Lucifer and the Archangel Gabriel, dressed in mountainfolk mufti, debate the spiritual problems of the characters on stage.

At the heart of this heady mix, Julie was cast in the "Lot's wife" role of Becky Dunbar, a winsome but headstrong teenage mountain girl described in the script as "grow'd up wild as onion weed" (Richardson and Berney, 1954, Act 1, Scene 2, n.p.). Becky finds herself pregnant after a brief dalliance with Joe Morgan, a charming but unscrupulous travelling salesman. She is torn between her passion for Joe and her moral duty to Lot Johnson, a virtuous widower who marries her because "it's the Christian thing to do" (Richardson and Berney, 1954, Act 1, Scene 5, n.p.).

Julie often jokes that "You've never heard a worse Southern accent than mine" (Newquist 1966, p. 141) -- and the script's hillbilly argot certainly would have proved a challenge to her crisp Home Counties consonants and rounded vowels. Becky's very first line, for example, is: "I ain't been gallivantin', just skimmin' rocks at Turkey Creek" (Richardson and Berney, 1954, Act 1, Scene 2, n.p.). Not exactly typical RP phraseology!

On a less challenging note, the show also featured a series of musical interludes with ritual dances and allegorical songs. Sporting titles like "Lullaby to an Unborn Child", "The World is Wide" and "Oh, It's Dark in the Grave", the musical numbers may not have been cheery toe-tapping ditties, but reviewers typically singled out Julie's singing as an all-too-rare highlight.

"Julie Andrews..prov[es] her undisputed musicianship by taking one song on high E flat, solus, and in perfect tune," marvelled one reviewer (Bradbury, 1954, p. 8). Another chimed: "We are inclined to think poorly of Becky until we realise how well she is to be played by Julie Andrews...Sodom and Gomorrah...seem to sweeten because of her presence... and she sings very pleasantly on the few occasions afforded to her" ('Midland entertainments,' 1954, p. 17). Given the Biblical source material, the story of Mountain Fire could only end in grand tragedy. And, lo, by play's end the backcountry villages have been consumed by fire and our poor Julie is turned to salt. If naught else, the last scene of Mountain Fire certainly gave Julie a scenery-chewing finale for her straight dramatic debut:

LOT (Offstage): Remember the warning, Becky! Don't look back! The hoot of the owl is heard. BECKY starts up the hill. She stops, hesitates, almost looks back. Music builds. Again she goes forward, stops, almost looks back. Music continues to build. The third time she turns and does look back. Music crescendo. The lights dim, then rise again. BECKY has become salt. She lies motionless reaching towards JOE. Blackout CURTAIN (Richardson and Berney, 1954, Act 1, Scene 2, n.p.)

From Sodom, Tennessee to the Scepter'd Isle

The background saga of bringing Mountain Fire to the stage was almost as feverish as the storyline. The play began life in 1950 when Richardson and Berney completed their first working script under the original title of Sodom, Tennessee.

The play was initially optioned by Jack Segasture, a 23-year-old would-be Broadway producer who had managed Richardson and Berney's previous work, Design for a Stained Glass Window. That production proved a misfire, closing after just 8 performances, but Segasture was keen to back the playwrights for a second attempt at Broadway success (Watt, 1950, p. 47).

In the summer of 1950, Segasture mounted a series of workshops of Sodom, Tennessee at various regional Pennyslvania theatres (Talley 1950, p. VI-13). Reviewing one of these early work-in-progress performances, the critic for Variety ventured that "with some doctoring, [it] may have possibilities for Broadway, where it is headed" ('Review: Sodom Tennessee', 1950, p. 40). In late-1950, Segasture announced that Sodom, Tennessee was set to start rehearsals the following January ahead of an anticipated New York opening in the spring ('Set Broadway", 1950, p. 26). Robert Perry was contracted to direct, with Robert Lowery and Jean Parker in discussions for the leads ('Film player,' 1951, p. 57). However, in April 1951, Segasture was suddenly drafted into the Army, and plans for the production were promptly scuttled ('Producer drafted,' 1951, p. 15C).

Over the next few years, various attempts were made to resurrect Sodom, Tennessee, but with little progress. In mid-1953, a lifeline came in the form of a pair of second generation producers: David Aldrich, son of famed producer, Richard Aldrich -- a.k.a. Mr Gertrude Lawrence to fans of STAR! -- and Anna Deere Wiman, daughter of Dwight Deere Wiman and heiress to the John Deere family fortune (Shanley, 1953, p. 10). Wiman had come into a sizeable inheritance on her father's death and she effectively bankrolled much of the production's initial $80,000 investment (Franklin, 1953, p. 9-E). Wiman and Aldrich tapped Peter Cotes -- a British director who had scored a recent New York success with A Pin to See the Peepshow -- to take on directorial duties (Calta, 1953, p. 14). They also invited Pulitzer-prize winning composer, Lamar Stringfield, to write the musical score ('Stringfield asked,' 1953, p. 7). At one stage, the producers were allegedly in discussions with none other than Marilyn Monroe to make her Broadway debut in the role of Becky but, wisely perhaps, she declined (Winchell 1953, p. 19).

In early 1954, plans for Sodom, Tennessee underwent a dramatic change. For reasons unknown, Aldrich was suddenly out of the production team. In his place, director Peter Cotes was promoted to co-producer status with Wiman. Possibly because Cotes was British, it was decided to relocate the production across the Atlantic and launch the show in the UK ('News of the theater' 1954, p. 6). Another factor was that production costs were lower in the UK than New York, something which would see the American Wiman remain as a London-based producer for several years (Hatwell 1957, p. 19; Wilson 1956, p. 10). Additionally, Richardson and Berney's earlier work, Dark of the Moon had enjoyed a fairly successful West End run in 1949, so the producers possibly reasoned that the new show might fare similarly well with English theatregoers (Darlington, 1949, p. 5).

Either way, Sodom, Tennessee was now set to make its world premiere in England -- though still with hopes of an eventual New York transfer ('Romantic comedy,' 1954, p. 17C).

'Not fit for the marquee of a British theatre'

Once the production team hit London, they set about preparing the play for its British bow. The first thing to go was the title.

Up until 1968, British censorship laws required all plays intended for public performance to be submitted to the Lord Chamberlain's Office for review and approval (Shellard et al, 2004). It seems the Lord Chamberlain did not approve of a play called Sodom, Tennessee, "an immoral name not fit for the marquee of a British theatre". Initially, the production team toyed with Brimstone as an alternative title, but finally settled on Mountain Fire (Talley, 1954, p. VI-5).

It was also decided that the show needed a musical overhaul. Some incidental music had been composed for earlier iterations, including piecemeal efforts by Lamar Stringfield. One or two of these pieces were retained but, for the most part, the producers opted for a new score. For this task, they contracted Stefan de Haan, a young German musician and composer who had come to study in the UK after the war and stayed on to work with various regional orchestras. De Haan not only composed a new score for Mountain Fire, including three new songs for Julie, but also signed on as music director and conductor (Bradbury 1954, p. 4).

Other key creative appointments were Michael Stringer as set designer and Daphne Kiernander as choreographer. Stringer came to the project fresh from working on the hit Rank comedy, Genevieve (1953), and a host of other film and theatre productions. He designed darkly stylised sets for all 14 scenes of the play, as well as orchestrating special effects for the final destruction sequence (Bishop 1954, p. 8). Kiernander was a classically trained ballerina who had performed as a principal in many West End shows and revues before shifting to choreography. For Mountain Fire, she created two set dances, broadly patterned on 18th century folk dances, and oversaw general staging for the songs ('Chit Chat', 1954, p. 8).

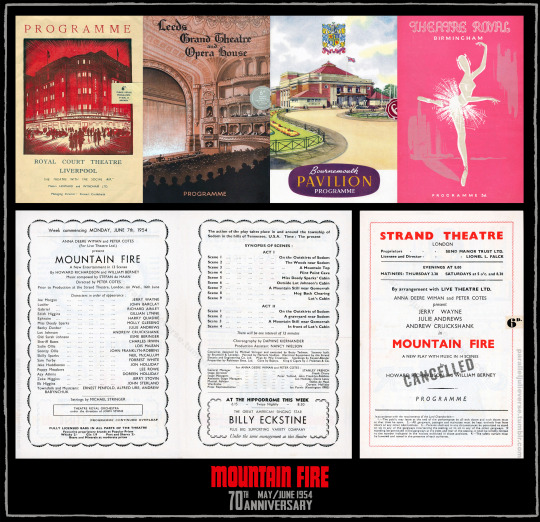

In early April 1954, Howard Richardson and William Berney arrived in London to help make revisions to the script. They also served as dialect coaches for the cast (Talley 1954, p. VI-5). During this early rehearsal period, Julie worked closely with Cotes' actress wife, Joan Miller who, as Julie relates, "tried to help me find the nuances that were needed for the part" (Andrews 2008, p. 171). Indeed, to hear Cotes tell the story, "Julie Andrews...was taught how to act by Joan Miller" and it was "Mountain Fire and Joan Miller between them [that] gave Julie the much needed groundwork..to erupt onto the Broadway stage" (Cotes 1993, p. 23). Not sure Moss Hart would agree, but anyway... Later that month, Cotes and Miller hosted an official launch party for Mountain Fire at their South Kensington home with local theatre and high society luminaries in attendance (Candida, 1954, p. 2). The show's schedule was set with a month-long tryout starting on 17 May in Liverpool, followed by one week runs in Leeds, Bournemouth, and Birmingham. The show's London opening was scheduled for Wednesday, 16 June at the Strand Theatre, Aldwych.

In mid-April, the tour was formally announced with ticket sales opening immediately:

"On May 17 at the Royal Court, Liverpool, Peter Cotes and Anna Deere Wiman will present the world premiere of Mountain Fire by Howard Richardson and William Berney. Making her debut as a straight actress in this play will be 18-year-old Julie Andrews. Other leading roles will be played by Jerry Wayne, Andrew Cruickshank, Gillian Lynne and Charles Irwin. Music for this production has been composed by Stefan de Haan. Decor will be by Michael Stringer, and choreography Daphne Kiernander. Peter Cotes is directing, and following a short tour the play will be presented in the West End" ('Chit Chat: Mountain Fire' 1954, p. 8).

'Every night it was a new show...'

The function of an out-of-town tryout is to put the finishing touches on a show ahead of its official "big city" opening. Cast and crew get to see how the play is working with live audiences and revise things accordingly. In happy cases, the tryout is a relatively easy process of fine-tuning elements and smoothing out wrinkles. In other cases though, the process can be far more tumultuous. Seth Rudetsky (2023) relates that New York theatre-folk popularly joke, "if Hitler were alive today, his punishment should be doing an out-of-town tryout with a show that's in trouble" (p. 152). Even Adolph might have blanched at the Mountain Fire tryout. A sign of early trouble came days out from opening when the producers suddenly announced a 24-hour postponement of the Liverpool premiere from Tuesday 17 to Wednesday 18 May (H.W.R. 1954, p. 4). Rehearsals had revealed serious structural issues with the show and the production team needed every hour they could muster to hammer it into shape.

Worse still, the key creatives couldn't agree about the source of the problems and how to fix them. Director Cotes believed the biggest problem was the script and he wanted major rewrites. For their part, Richardson and Berney felt the musical sequences were at fault.

Jerry Wayne, who took the male lead of Joe Morgan, recalled:

"[W]e ran into trouble with the American authors. They objected to the musical numbers that had been written into their story. We opened at Liverpool on a Thursday night as a musical. Then we were told to cut out the musical numbers. On Friday night we opened at 7.30 as a straight play. With the music cut, the curtain ran down at 8.15" (Greig 1955, p. 9)

The songs were duly reinstated, but competing revisions were trialled to staging and orchestration. In her memoirs, Julie relates:

"Our director couldn't decide whether he wanted the orchestra in the pit or onstage, or no orchestra at all. This was a play, after all, so he then thought maybe one instrument, a guitar, would be enough. We tried the show a different way every night" (Andrews 2008, p. 160).

Another member of the cast, Neil McCallum, similarly recalled the snowballing desperation of the tryout tour:

"Everyone hoped it would get better, so the authors and the director got together and decided to revamp the whole show. They kept writing new scenes every day...every night it was a new show until not even the cast recognized it...Pretty soon the authors and the director weren't speaking. Two days later the authors and the backer weren't speaking. Finally, no one was speaking" (Tesky 1954, p. 6).

A comparison of scene synopses printed in programmes for Mountain Fire across its month-long tryout reveals the extent to which the production altered across performances. During its first night in Liverpool, the show was comprised of three acts and fourteen scenes. The following week in Leeds, it was still three acts but down to only ten scenes. In Bournemouth, it was back to three acts with fourteen scenes. By the time it got to Birmingham, the play was suddenly just two acts with thirteen scenes!

'Call down fire and brimstone...'

Given the panicked disorganisation that plagued the tryout, it should not surprise that reviewers took a rather dim view of Mountain Fire. Indeed, other than praise for Julie and fellow cast members, critics were mostly scathing in their assessment of the show -- with notices getting progressively more brutal as the tour continued:

The Liverpool Echo: "When the new play, Mountain Fire, opened with a dissertation by the Angel Gabriel and Lucifer on the delights of being good and bad, it was obvious that this world premiere at the Court Theatre last night would provide something unusual -- and so it proved. But whether this modern parable of Lot's wife will meet with general approval is problematical, because in attempting to lighten high drama with a smattering of musical numbers plus one or two dances, the American authors, Howard Richardson and William Berney, have achieved a curious hotch-potch which is neither one thing nor the other" (H.W.R. 1954, p. 5).

The Stage: "The Liverpool audience could be forgiven for their puzzlement over this provocative, somewhat bewildering, production, which rather inclines to fall between the two stools of allegorical drama and musical entertainment, lacking the virtue of anything in the way of a hit tune" ('American folk play' 1954, p. 10).

The Yorkshire Observer: "Symbolism on the stage is meat only for those who can stomach such food and, it is difficult to live on meat alone. So it might be that Mountain Fire which, in the second week of its production, is now at the Leeds Grand Theatre, might easily die as quickly as the symbolical fire it portrays, no matter how brilliant the cast" ('Symbolistic musical' 1954, p. 6).

Bournemouth Daily Echo: "Bournemouth Pavilion audience last night was bothered and bewildered -- but never for one moment bewitched -- by the new musical play Mountain Fire…The play opens with the body of a parson being buried on the hilltop, and proceeds through a welter of hell-fire and brimstone, religious fervour and an atmosphere reminiscent sometimes of Tobacco Road, sometimes of Annie Get Your Gun, and sometimes of The Quaker Girl on thin ice…Most of last night's audience were wondering what it was all about. I am still wondering" (G.Y 1954, p. 6).

Birmingham Daily Gazette: "Mountain Fire, a somewhat disastrous item which arrived at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, last night, is an odd mix of sex and religiosity which, I fear, will prove seriously offensive to many...The whole thing is meant to be an allegory, with a deep application to our atom-bomb age. But it is all expressed in such appallingly banal language that it leaves one convinced that the underlying thought must be equally banal...One can only have sympathy for the very talented performers who struggle with this material" (Mackenzie 1954, p. 4).

Evening Despatch: "Howard Richardson and William Berney are evidently generous-minded men. In their play, Mountain Fire, at Birmingham Theatre Royal, they include murder, two burials, the Ku Klux Klan..., Lucifer, the Archangel Gabriel, religion and, of course, sex...Directed by Peter Cotes, this is a bewildering story of sin among the backwoodsmen of Tennessee...Somewhere in all this there may be a moral. At first I found it difficult to keep up. Eventually I gave up trying" (Holbrook 1954, p. 6).

The Birmingham Mail: "The conscientious critic of the drama will find that there are certain troublesome questions which are created in the mind by Mountain Fire, the new play by Howard Richardson and William Berney. How, for instance, did it come about that it reached the stage of the Theatre Royal at all and how is it that next week it is to occupy the stage of a West End theatre, however short its tenure there may be? What is more to the immediate point is how one ought...to deal by way of notice with so poor an offering. Ought one to call down fire and brimstone or, refusing to treat the piece seriously, as did many of the audience last night, rend it with ridicule?" (C.L.W 1954, p. 4).

'Mountain Collapses'

With this level of bad press, the prognosis for Mountain Fire was bleak. Ticket sales were sluggish and the cast often found themselves playing to half empty houses. Even worse, audience members were increasingly audible with their displeasure. As Neil McCallum relates:

"One of the lines at the last of the play is 'Lot, don't turn back.' Came a voice from the audience, 'I don't know about turning back -- I want my bloody money back.' In the interval, the ushers were mingling with the audience saying, in ringing tones, 'isn't it terrible...don't you wish you hadn't come?'" (Tesky 1954, p. 6).

By the final week in Birmingham, the writing was on the wall and producers decided to avoid what would surely have been a critical and commercial bloodbath in London. On Thursday 10 June, barely 5 days before the show was scheduled to open at the Strand, Wiman and Cotes issued a joint statement saying they were cancelling the West End premiere of Mountain Fire:

"In view of the inadequate public response during the tour of the play, it would be unfair to the authors and the actors and other members of the production that it should open in London, at least without substantial variations" ('Play is off', 1954, p. 3).

The decision to cancel a major production so close to its premiere was not without precedent, but it was sufficiently rare to garner widespread press attention, generating a slew of punning headlines. "London douses 'Mountain Fire'," trumpeted the New York Times (1954, p. 13). "Mountain Collapses" blared the Kensington News ('Theatre Notes' 1954, p. 2). And "Mountain Fire Out!" declared the Daily Post (Daily Post London Reporter 1954, p. 1)

Mountain Fire had two further performances to complete its Birmingham run, and once the curtain came down on Saturday night of 12 June, the production staggered to its sorry close. Richardson and Berney had already taken early departure back to the US, unable to watch the show's final demise. Cotes similarly retreated to London and refused for many years to even discuss the play. Producer Anna Wiman insisted on staying to the very end. "No cast has been more loyal than this one," she declared, valiantly talking up a future for the show. "[I]t's not the end...I believe in this play and I am determined that it shall have a successful run in London. It will have a new director and a new atmosphere" (Mercury Staff Reporter 1954, p. 1.) The following March, a 'news in brief' snippet claimed Wiman was "still trying to lease or buy a theatre, with the Bill Berney-Howard Richardson play, Mountain Fire, as first on her production schedule" (Walker 1955, p. 61). But a year later, she would admit defeat, having lost the full extent of her £40,000 investment in the show (Wilson 1956, p. 10).

In the end, it wasn't just the UK production of Mountain Fire that sank. The play itself effectively vanished with little appreciable after-life. The script was never published, nor is there any record of it being registered with a theatrical licensing company. Only one further staging of the show ever seems to have taken place: a brief five performance run in May 1962, under the play's original title of Sodom, Tennessee, at the Little Theatre of the West Side YMCA in Manhattan ('Premiere,' 1962, p. 14). Billed as the show's "New York premiere", it didn't attract much attention and there are no published reviews. After that, the play's trail comes to a complete halt.

If it weren't for the show's status as a footnote to the career of Julie Andrews, Mountain Fire would likely have been completely lost to history. Even at the time of its cancellation, reports were already framing Mountain Fire as a blip on the way to Broadway success for Julie:

"Julie may have missed a West End appearance, but she is to be compensated by a Broadway lead in The Boy Friend when the show goes to New York in the autumn" ('Theatre Notes' 1954, p. 2).

Within a year or two, Julie's stardom was the principal frame of reference for any mention of Mountain Fire. It even became something of a boast for those behind the ill-fated production .

In 1956, when Julie was riding high on the success of My Fair Lady, an Alabama newspaper crowed that local playwright William Berney "discovered Julie Andrews [when] he was in London...casting his play Mountain Fire...Julie 'was it' so far as Berney was concerned, and a happy unknown made her bow" (Caldwell 1956, p. E-1). Not to be outdone, Howard Richardson was also soon talking up how his "plays have sent many actors and actresses on their way to fame including...Julie Andrews...who played one of her first roles in Richardson's Mountain Fire during its London [sic] run" ('New York playwright' 1959, p. 14).

All of which only proves the popular adage that, where failure is an orphan, success has many fathers!

____________________________

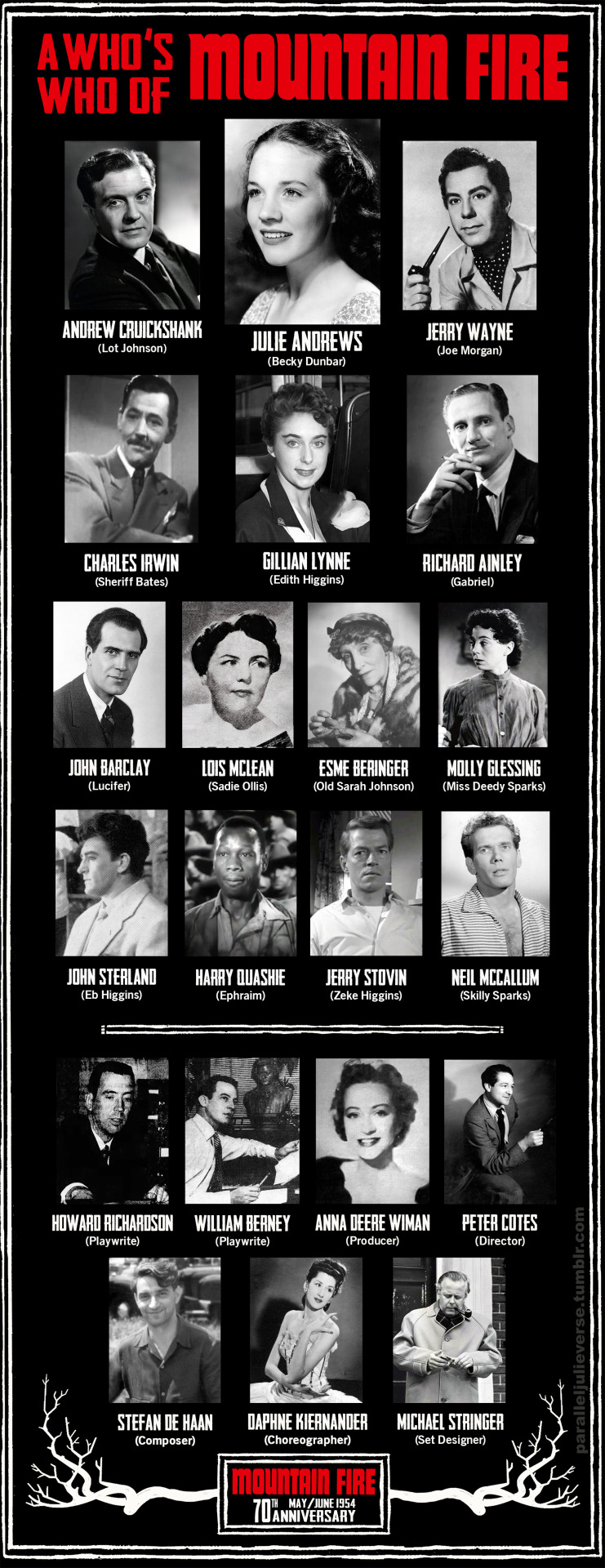

Who's Who of Mountain Fire

While Julie was undoubtedly the biggest star associated with Mountain Fire, the show included a roster of established and upcoming theatre talents, many of whom went on to bigger and better things:

Principals

Jerry Wayne as Joe Morgan (1919-1996): Born in Buffalo, New York in 1919, Wayne was a recording vocalist of some note who even hosted his own CBS radio show in the 1940s. He came to London in 1953 to play the lead role of Sky Masterson in the West End production of Guys and Dolls, marking the start of a British career. He appeared in the 1955 film musical, As Long as They're Happy and made several TV appearances in the 1960s. In 1967, Wayne married the novelist Doreen Juggler and graduated to a second career as a theatre and recording producer. Collaborating with his son Jeff, Wayne had notable success with the 1978 concept album, Jeff Wayne's Musical Version of The War of the Worlds. Wayne passed away in Hertfordshire in 1996 ( 'Jeff Wayne' 1996, p. 24).

Andrew Cruickshank as Lot Johnson (1908-1988): Born in Aberdeenshire, Cruickshank initially pursued civil engineering before turning to the stage. He made his professional debut in Shakespeare repertory and joined the Old Vic in 1937, playing notable roles such as Banquo in Macbeth, opposite Olivier. During WWII, he served in the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, earning an MBE. His varied career included significant roles in the West End production of Inherit the Wind (1960) and the National Theatre's Strife (1963). His best know role came courtesy of television as Dr. Cameron in the popular BBC series, Dr. Finlay's Casebook (1962-71). In later life, Cruickshank wrote a number of plays, and was president of the Edinburgh Fringe Society. He died in 1988 ('Andrew Cruickshank' 1988, p. 310).

Charles Irwin as Sheriff Bates (1908-1984): Born in 1908 in Leeds, Irwin began his career in variety shows and became a comedian and vocalist on radio in the 1930s. He worked extensively in regional theatre and appeared as a character actor in films such as The Third Man (1949), A Tale of Five Women (1951), and Mystery Junction (1951). In later decades, he transitioned to television, appearing in popular series like Danger Man (1960), International Detective (1961), and The Saint (1962). Irwin passed away in November 1984 in Salisbury.

Gillian Lynne as Edith Higgins (1926-2018): An influential figure in British theatre and dance, Lynne was born in 1926 in Bromley, Kent. She began her career as a ballerina, dancing with Sadler's Wells, the English National Opera, and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Lynne subsequently moved into choreography, working on many successful West End musicals. She was best known for her collaborations with Andrew Lloyd Webber, where her choreography was instrumental to the success of shows such as Cats and The Phantom of the Opera. In recognition of her contributions to dance and musical theatre, Lynne was made a Dame Commander in 2014. She passed away in 2018 at the age of 92 (Dex 2018, p. A13).

Richard Ainley as Gabriel (1910-1967): Ainley was born in Middlesex in 1910, the son of famed Shakespearean actor Henry Ainley. He debuted on stage with Martin Harvey's company, before going on to work with the Old Vic and Sadler's Wells. His first film role was in As You Like It (1936), followed by notable roles in The Tempest (1939) and Above Suspicion (1941). Severely wounded in WWII, Ainley had to abandon his film career and could only continue with occasional stage roles. Later, he focused on broadcasting and adjudication, briefly leading the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School in the early 1960s. He passed away in 1967 at age 56 (Coe 1967, p. 23).

John Barclay as Lucifer (1892-1978): Barclay was born in 1892 in Bletchingly, Surrey. A tall man with a booming basso baritone, he trained as an opera singer and toured widely with various companies, including D'Oyly Carte. He appeared in several films, including The Mikado (1939) and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941). In the late 1950s, Barclay moved to the US, where he pursued a late career playing strong and menacing character parts in film and TV. He passed away in 1978 at the age of 86.

Supporting Players

Molly Glessing as Miss Deedy Sparks (1910-1995): Midlands-born Glessing began her career in variety in the 1930s as a singer, dancer, and comedienne. She rose through the ranks to become a featured player in comedies and pantomimes. During the war, she gained popularity as a radio player and ENSA entertainer. After marrying a US serviceman, she relocated to California. Dividing her time between the US and the UK, Glessing continued to work in stage productions and amassed numerous character credits in films such as Charlie Chaplin's Limelight (1952), and TV shows, including The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1962) ('Glessing" 1996, p. 33).

Lois McLean as Sadie Ollis (1927-2013): Canadian-born McLean studied drama at the University of Alberta and performed for several years with the Everyman Theatre Company in Vancouver. In 1950, she moved to the UK where she continued to perform, while studying theatre production with the Glasgow Citizen's theatre. In 1953, McLean started work as a manager for Peter Cotes and he cast her in various productions including Mountain Fire (Narraway 1954, p. 34). The pair also collaborated on a book, A Handbook of British Amateur Theatre. In the late-50s, she wed Indian-born lawyer, Birendra Jha and returned to Canada to start a family. McLean continued to perform and teach drama in Edmonton.

Esme Beringer as Old Sarah Johnson (1875-1972): Born in London to artist parents, Esme Beringer was a celebrated stage actress who made her professional debut in 1888. Known for her athletic physique and swordsmanship, she excelled in breeches roles, including playing Romeo, Little Lord Fauntleroy and The Prince and the Pauper. An enthusiastic fencer, she taught classes during WWI and starred in Shakespearean roles post-war. In later life, Beringer moved into character parts both on stage and in film. She died in 1972 at the grand age of 96 ('Esme Beringer' 1972, p. 16).

Neil McCallum as Skilly Sparks: (1929-1976) Born in Canada in 1929, McCallum moved to the UK to study at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Following graduation he appeared in a number of stage shows, scoring his greatest theatrical success in 1956 with the West End production of The Rainmaker opposite Sam Wanamaker. In the 1960s, McCallum became a familiar face on British television in series like The Saint (1963-64) and Department S (1969), as well as voicing characters on Thunderbirds Are Go (1966). Transitioning behind the scenes, McCallum became a scriptwriter and producer of some note, helming a number of TV series for the BBC before his untimely death from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1976, aged only 46 ('Neil McCallum', 1976, p. 11). As detailed by Julie in the first volume of her memoirs, she and McCallum embarked on a serious, if short-lived, romance during the production of Mountain Fire (Andrews, 2008, p. 161ff).

Jerry Stovin as Zeke Higgins (1922-2005): Born in Unity, Saskatchewan in 1922, Jerry Stovin served in the Canadian Army where he got the acting bug performing in military entertainments. Following the war, he went to Carnegie Tech to study drama, and moved to Britain in 1955. There he carved out a successful career in radio, television, and film, often playing American roles. He passed away in 1978 at the age of 86 (Peacock 1975, p. 7).

Harry Quashie as Ephraim (1914-1982): Born in Ghana, Quashie originally came to the UK to study law in 1939. He started to act in university theatricals and soon gave up his studies to pursue an acting career. He performed in a wide range of stage, radio and TV dramas and was a founding member of the Negro Theatre Company which helped pave the way for Black theatre artists in Britain. In the 50s, Quashie had character parts in several big screen features notably, Simba (1955), Safari (1956), and, The Passionate Summer (1958) ('Gave up law' 1947, p. 1; Bourne 2021).

John Sterland as Eb Higgins (1927-2017): Another Canadian actor, Sterland was born in Winnipeg to English parents. He came to the UK on a RADA scholarship, before joining the West of England Theatre Company. In a long career, Sterland racked up scores of stage and screen credits including A Countess from Hong Kong (1967), Performance (1970), Ragtime (1981), Bad Medicine (1985), Batman (1989), and The Tudors (2007). Married for many years to fellow actor, June Bailey, Sterland passed in 2017 ('John Sterland' 2017, p. 12).

Creatives

Howard Richardson (1917-1984): Born in Spartanburg, South Carolina, Richardson graduated from the University of North Carolina in 1938 and earned his M.A. in drama in 1940. After serving in the Army, Richardson co-wrote Dark of the Moon with cousin and frequent collaborator, William Berney. The play opened on Broadway in 1945, running for 318 performances. Despite frequent efforts, both in collaboration with Berney and as an individual playwright, Richardson would never match this initial success. In 1960, he earned a doctorate in 1960 and embarked on a career as a drama professor, working at various colleges throughout the US. He passed away in 1984 ('Howard Richardson', 1985, p. 34).

William Berney (1920-1961): Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Berney graduated from the University of Alabama, where he was active in drama. He later attended graduate school at the University of Iowa, where he started writing plays with Richardson. After graduation, Berney worked in advertising in New York, while pursuing his scriptwriting career on the side. During this period, he co-wrote several plays with Richardson, including Design for a Stained Glass Window (1950) and Protective Custody (1956). Berney moved to California around 1960 to write for television, but sadly passed away in Los Angeles in 1961 after a brief illness, aged 40 ('William Berney' 1961, p. 23) .

Peter Cotes (1912-1998): A theatrical polymath, Cotes -- who was born as Sydney Boulting in Maidenhead, Berkshire -- was part of a noted artistic family. His parents ran a theatre company and his brothers John and Roy Boulting became important filmmakers in British cinema. Initially an actor, Cotes shifted his focus to theatre production and directed the original production of The Mousetrap, the world's longest-running play. Other notable successes as director included the West End productions of The Children's Hour (1951) and A Pin to See the Peepshow (1952), and, in film, The Right Person (1955) and The Young and the Guilty (1958). In later years, Cotes wrote books and helmed a number of theatre companies. He passed away in 1998, at the age of 86 ('Peter Cotes' 1998, p. 35).

Anna Deere Wiman (1920-1963): Born in Illinois, Wiman was the daughter of successful theatre producer Dwight Deere Wiman, and heir to the John Deere family fortune. Educated by private tutors, she trained as a ballerina in Paris until a cycling accident ended her dance career. She then shifted to theatre management, initially working under her father. After his sudden death, she inherited a fortune, allowing her to become a self-funded theatre producer. Moving to London in 1954 with Mountain Fire, Wiman remained in the UK where she produced several West End productions, including The Reluctant Debutante (1955), Dear Delinquent (1957), and The Grass is Greener (1958). Despite her professional successes, Wiman struggled with alcoholism. She tragically died in 1963 at her holiday home in Bermuda from a fall down the stairs while under the influence. She was only 43 years old. ('Obituary: Anna Deere Wiman' 1963, p. 27.)

Stefan de Haan (1921-2010): Born in Darmstadt, Germany, de Haan was a gifted musician who trained in Berlin and Florence, before coming to the UK to study composition at the Royal College of Music. Following graduation, he initially gained prominence as a bassoonist, performing with various ensembles and orchestras. His compositional work includes a range of chamber music and orchestral pieces, often highlighting his expertise with woodwind and brass. His influence extended into music education, where his works are still performed and studied today. De Haan passed away in 2010, aged 89 (Bradbury 1954; 'Stefan de Haan' 2024).

Daphne Kiernander (1921-1998) Born in 1921, in East Preston, West Sussex, Kiernander was an accomplished dancer who rose to fame performing in various West End reviews and musicals such as Bobby Get Your Gun (1938), Let's Face It (1942), and Piccadilly Hayride (1946). She moved into choreography working on a number of stage and TV productions, including Such Is Life (1950) and Puzzle Corner (1953) for the BBC, and the Old Vic's 1955 production of The Taming of the Shrew. In the 1960s, Kiernander retired from dance to marry and start a new career in business and marketing (Powell 1962).

Michael Stringer (1924-2004) One of Britain's most successful film art directors, Stringer developed a passion for cinema early on. After serving as a RAF pilot in WWII, he trained with Norman Arnold at Rank Studios. There he scored notable success with one of his first independent assignments, Genevieve (1953), and followed it up with other popular Rank titles like An Alligator Named Daisy (1955) and Windom's Way (1957). His success in Britain led to international offers, working on big productions such as The Sundowners (1960), In Search of the Castaways (1962), and A Shot in the Dark (1964). Stringer went on to a distinguished Hollywood and UK career, bringing his talents to a long and diverse list of films, including Fiddler on the Roof (1971), which earned him an Oscar nomination, The Greek Tycoon (1978), The Awakening (1980), The Mirror Crack'd (1980), and The Jigsaw Man (1983). Stringer passed away in 2004. (Eyles 2004, p. 43).

Sources:

'American folk play: Mountain Fire bewilders.' The Stage. 20 May, p. 10.

'Andrew Cruickshank.' (1988). The Stage. 26 May, p. 10

Andrews, J. (2008). Home: A memoir of my early years. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bishoff, T. (1963). 'Playwright Richardson turns professor.' The Eugene Register-Guard. 6 October, p. 2E.

Bishop, G.W. (1954). 'Theatre Notes: an American play to start in London'. The Daily Telegraph & Morning Post. 3 May, p. 8.

Bourne, S. (2021). Deep are the roots: Trailblazers who changed Black British theatre. History Books.

Bradbury, E. (1954). 'Music Notes: Former YSO player as a theatre composer.' The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury. 22 May, p. 4

Bradbury, E. (1954). 'Mountain Fire at the Grand Theatre.' Yorkshire Evening Post. 28 May, p. 8.

Caldwell, L.M. (1956). 'Julie Andrews: Birmingham man discovered "my fair lady".' The Birmingham News. 28 October, p. E-1.

Calta, L. (1953). ‘Cotes will direct “Sodom, Tennessee”: drama based on Biblical story to open on Broadway early in February -- 26 in cast.’ New York Times. 7 November, p. 14.

Candida. (1954). Theatre Notes: Peter Cotes and party. The Kensington News and West London Times. 23 April, p. 2.

'Chit Chat: Mountain Fire'. (1954). The Stage. 22 April, p. 8.

'Chit Chat'. (1954). The Stage. 20 May, p. 8.

C.L.W. (1954). 'Modern morality play.' The Birmingham Mail. 8 June, p. 4.

Coe, J. (1967). 'Obituary: Mr. Richard Ainley." Evening Post. 23 May, p. 23.

Cotes, P. (1993). Thinking aloud: Fragments of autobiography. Peter Owen Publishers.

Daily Post London Reporter. (1954). 'Mountain Fire out'. Liverpool Daily Post. 11 June, p. 1

Darlington, D.A. (1949). 'First Night: A triumph of production, play about witches.' Daily Telegraph. 10 March, p. 5.

Dex, R. (2018). 'Cats choreographer Gillian Lynne dies at 92.' Evening Standard. 2 July: p. A13.

'Drake in Village'. (1952). Daily News. 10 November, p. 17C.

Duncan, R. (1966). 'They know the old-time religion.' Independent Star-News. 20 February, p. S-7.

'Esme Beringer.' (1972). The Stage. 6 April, p. 16.

Eyles, A. (2004). 'Obituary: Michael Stringer.' The Independent. 2 April, p. 43.

'Film player gets lead with Parker.' 1951. Daily News. 14 February, p. 57.

Fisher, J. (2021). Historical dictionary of contemporary American theater. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Frank, E. (1954). 'Julie Andrews graduates.' News Chronicle. 15 April, p. 6.

Franklin, R. (1953). 'On Broadway.' Miami Daily News. 19 July, p. 9-E.

'Gave up law for stage.' (1947). Evening Telegraph. 13 October, p. 1.

'Glessing, Molly". (1996). The Spotlight. January, p. 33.

Greig, R. (1955). 'Mr. Wayne will not rush this script.' Evening Standard. 22 June, p. 9.

G.Y. (1954). 'Mountain Fire is not volcanic." Bournemouth Daily Echo. 1 June, p. 6.

Hatwell, D. (1957). 'Anna becomes a powerful force in British theatre.' Evening Post. 12 December, p. 19.

Holbrook, N. (1954). 'The devil gets good parts.' Evening Despatch. 8 June, p. 6.

'Howard Richardson is dead; co-author of "Dark of Moon".' (1985). The New York Times. 1 January, p. 34.

H.W.R. (1954). 'And on the stage.' The Liverpool Echo. 7 May, p. 4.

H.W.R. (1954). 'Mountain Fire: world premiere in Liverpool' The Liverpool Echo. 19 May, p. 5.

'Jeff Wayne'. (1996). The Stage. 26 September, p. 24.

'John Sterland.' (2017). Wandsworth Times. 30 December, p. 12.

'London Douses "Mountain Fire'". (1954). New York Times. 12 June, p. 13.

Mackenzie, K. (1954). 'Show News: She's on her way to Broadway.' Birmingham Daily Gazette. 4 June, p. 4.

Mackenzie, K. (1954). 'A hill-billy Bible story.' Birmingham Daily Gazette. 8 June, p. 4.

Mercury Staff Reporter. (1954). 'Miss Wiman admits a failure.' The Sunday Mercury. 13 June, p. 1.

'Midland entertainments: Mountain Fire.' (1954). Birmingham Daily Post, 8 June, p. 17.

Narraway, M. (1954). 'Actress is happy again.' The Vancouver Province. 27 March, p. 33.

'Neil McCallum.' (1976). The Stage and Television Today. 29 April, p. 11.

'New American musical at Theatre Royal.' (1954). The Birmingham Post. 4 June, p. 4.

Newquist, R. (1966). 'Julie Andrews: An overnight success -- after 22 years.' McCalls. March, pp. 83, 140-43.

'New York playwright visits town.' (1959). Johnson City Press-Chronicle. 15 July, p. B-4.

'News of the theater.' (1954). Brooklyn Eagle. 16 March, p. 6.

'Obituary: Anna Deere Wiman.' (1963). The Stage. 28 March, p. 27.

Peacock, B. (1975). 'Jerry Stovin is busy.' The Leader-Post. 18 July, p. 7.

'Peter Cotes, 86, producer and director of 'Mousetrap'." (1998). The New York Times. 18 November, p. 35.

'Play is off: inadequate support during tour.' (1954). Daily Mail. 11 June, p. 3.

Powell, E. (1962). 'She turns from show business to shops.' The Liverpool Echo and Evening Express. 30 March, p. 18.

'Premiere of "Sodom" Friday. (1962). New York Times. May 12, p. 14.

'Producer drafted, 2 plays in doubt.' (1951). Daily News. 28 March, p. 15C.

'Review: Sodom Tennessee, Guthsville, Pa. Aug. 29.' (1950). In Beckhard, R. & Effrat, J. (Eds). Blueprint for summer theatre: 1951 supplement. John Richard Press, pp. 40-41

Richardson, H. & Berney, W. (1954). Sodom, Tennessee: A play in three acts. British Library, Lord Chamberlain’s Collection of Plays 1954/37.

'Romantic comedy set for October.' (1954). Daily News. 12 March. p. 17C.

Rudetsky, S. (2023). Musical theatre for dummies. John Wiley & Sons.

'Set Broadway showing of "Sodom, Tennessee".' The Chattanooga Times. 19 November, p. 26.

Shanley, J.P. (1953). 'New team follows in fathers' steps: David Aldrich, Anna Wiman to offer "Sodom, Tennessee" as first play in Fall.' New York Times. 3 July, p. 10.

Shellard, D., Nicholson, S., & Handley, M. (2004). The Lord Chamberlain regrets : a history of British theatre censorship. British Library.

'Stefan de Haan'. (2024). Musicalics: The classical composers database. [Website].

'Stringfield asked to pen music for "Sodom, Tennessee".' (1953). The Knoxville News-Sentinel. 4 June, p. 7.

'Symbolistic musical at Leeds Grand.' (1954). The Yorkshire Observer. 26 May, p. 6.

Talley, R. (1950). 'An imaginary Tennessee won is site for "wicked" new play.' The Commercial Appeal. 8 October, p. VI-13.

Talley, R. (1954). 'British actors must learn how Tennessee hillbilly talks.' The Commercial Appeal. 18 April, p. VI-5.

Testy, H. (1954). 'New twist to success story: Neil McCallum on ladder to acting career.' The Saskatoon Star-Phoenix. 11 August, pp. 3, 6.

'Theatre Notes: Mountain Collapses.' (1954). The Kensington News and West London Times. 18 June, p. 2.

Watt, D. (1950). 'Ailing Harrison can't stage play.' Daily News. 7 February, p. 47.

'William Berney, 40, Coast playwright.' (1961). The New York Times. 25 November, p. 23.

Wilson, C. (1956). 'Now Miss Wiman is on "The Ball"." Daily Mail. 20 April, p. 10.

Winchell, W. (1953). 'The Main Stem Lights: Marilyn rejects role.' The Pittsburg Sun-Telegraph. 8 December, p. 19. ©2024, Brett Farmer. All rights reserved.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I just Played Star Fox Assault For the First time in Years and I have some thoughts...

So Star Fox, a franchise that needs no introduction when it comes to weird directions for a franchise to take. What started out as another classic Miyamoto title that fit perfectly alongside the likes of Mario and Zelda. Star Fox kinda fell into the unenvieable position of Mid tier Nintendo franchise: Iconic enough to have a bunch of devoted fans and not be lumped in with the weirder more niche releases like Geist, Chibi Robo, and Pushmo, but not quite enough a sales juggernaut to become a core pillar of Nintendo that will almost always get an new game with each console like Pokemon, Animal Crossing, and of course, Mario. With the GameCube being a particularly tumultuous time for the furry space mercenaries.

I'll admit though, GameCube is where I come into the Star Fox story. As I was actually not really a fan of the original SNES game or Star Fox 64. This was because as flight based rail shooters where the cool animals were bound to their ships for most the game, I just didn't really get the appeal. But around the sixth generation with the advent of... Star Fox Adventures I was willing to give the franchise another chance. And while Star Fox Adventure is literally not a Star Fox game, I still enjoyed it as it focused a bit more on something I wanted-actual control of Fox McCloud the character (Of course then I played Smash Melee and basically got the same experience). But ultimately after the GameCube generation Star Fox never really stuck with me the way it had with its fanbase. But there was one more game on the GameCube that I hadn't played for a while. Like... almost 20 years ago. Star Fox Assault.

Star Fox Assault feels like a weird middle child of the franchise no one really wants to talk about even though before the disaster that was Star Fox Zero on the Wii U, this was basically the last home console Star Fox game. And it looked to appease long-time fans of the franchise that wanted an in-depth 3D rail shooter and newer fans like me that wanted more direct character involvement gameplay. Assault originally started as an expansion of the Star Fox 64 multiplayer on-foot death match with the single-player story mode eventually being added later after poor reception to an E3 2003 showcase focusing on just the multiplayer aspect according to Electronic Gaming Monthly. This would also be a Star Fox that would be handled by Namco instead of Nintendo in-house. So did they manage to make that perfect Star Fox that would appease old and new fans and provide a fun multiplayer experience?

Well... its complicated.

Star Fox Assault, even now with my 20 extra years of developing my video game tastes still hits me oddly. The flight sections feel really slick and operatic, honestly Assault really made get the space opera vibes that fans often praised 64 for. The Arwing sections running on a much smoother frame rate than 64 also helps. Add on the damn great score after Adventures pretty generic one, and you might just have one of the best openings of the series. Seriously, even as someone who doesn't really like the flight combat sections, the presentation is strong.

But that's just the flight sections, what about the ground sections? While these section have been controversial, I actually like them. Fox being able to just get out of the vehicle and interact with these planets on a smaller scale is something that kept me from really enjoying the 64 game, but the problem with Adventures is that when they did this, their style of gameplay was closer to Ocarina of Time, with melee based combat and emphasis on exploration and puzzle solving. But Assault giving Fox a gun and making the levels being more open with little platforming honestly feels way more true to the series. Fox run and gunning through Aparoids feels like something out of Starship Troopers, and that's the kind of gameplay I think Fox and co should have and not a magic staff.

However, these on foot missions sadly are hampered by the controls. The tank-ish controls are just not conducive for me, and I would've preferred a more Star Wars Battlefront 2 style of third-person shooting. Also the GameCube controller is just annoying to play a shooter on. It always feels like when I need to get that one precise shot, I'm fighting with the control stick. Still though after all these years, this is still the part of the game I remember the most, and had hoped to see more of with some level of tune ups in future installments, but that ended up being a different story.

Speaking of the story, how is it? Honestly, the story is fun, introducing this new race of cyber insects that assimilate machines and people becoming such a threat the Fox and Wolf need to team up to beat them. Its simple, but lends itself to a lot of epic moments. Aparoids going for a more existential horror than Andros changes up the vibe of what we're fighting being a "Bug Hunt" (yes, I did just go there) and allowed us to put all of our characters under intense pressure. As well as have our banter with Wolf and his crew.

However, one thing it lacks from Star Fox 64 is branching paths, rather they opt for one much longer singular narrative which isn't a bad thing, but that leads into I think the biggest problem with this game, its single player mode is really short. All told-with cutscenes-I spent somewhere between 4 to 5 hours playing the main campaign. This is a shame because the branching pathways of 64 allowed for more replayability and unique play experiences. Now knowing that this game's single player mode came later while the emphasis on was making a great multiplayer experience first and that Assault would see multiple delays across its development cycle, its safe to assume the story treatment of the campaign didn't have enough time.

This is especially bad when we were in the sixth generation of console gaming. See, small tangent, I think one of Star Fox's problems is at its core its a very arcade-y style game, and by the time of the PS1, lots of arcade style games were getting left behind by console gamers. Stuff like Daytona USA, Pac-Man, and Virtua Fighter were more made to be quick quarter munching experiences that got pretty note-for-note home ports just weren't really justifying a purchase with what the amount of content they were offering. By now, gamers were looking for longer games, that were more ambitious in scope and story, and more complex in level design. They didn't have to be played over and over again, they were just a completely filling experience for gamers. This only got more prevalent going into the PS2.

Take for example, Panzer Dragoon by Sega, which started as a Rail Shooter like Star Fox in 1995, but by 1998 would convert in to a more traditional RPG to compete with the likes of Final Fantasy 7 on the Playstation.

But Nintendo being their usual unusual selves didn't really commit hard either way. You got arcade style games like F-Zero GX and WarioWare Micro Mini Games, but then you have games like Metroid Prime and Super Mario Sunshine that open the player up to these diverse 3D worlds and environments that you could sink hours into. Star Fox Assault sadly felt like it was stuck in the middle. You get some space sections that feel right at home with Star Fox 64, but clearly they wanted you to have something more than just being in the Arwing. But the story around those outside the Arwing or Land Master is so minimal it leaves a lot of Star Fox Assault feeling like potential was left on the table.

I know Assault isn't pure Star Fox like a lot of fans want. The on-foot sections were going to be divisive no matter what. There are fans who just want to continue the story of the Lylat Warriors but through the mechanics of 64. However, as a non purist and more casual enjoyer of the Star Fox franchise, I can say having a more intimate character levels can go a long way for people wanting to engage with the game and its world. Instead of just seeing Fox as a little talking head in the corner of the screen, being on the ground as fox fights for life is attractive. But its clear that these sections had a lot of potential just left on the table. Instead of taking the formula of Assault that mixed flying rail shooting sections with ground combat peppered with story and character moments and improving upon it and drawing out new stories or game ideas for it, Nintendo opted to basically just remake 64 again and again.

I guess we'll never know what it look like if Nintendo invested in a game that mixed the air and ground combat in a fun and slick fashion that offered a lot of content. Wait... they did do that it was called Kid Icarus Uprising!

Yeah, its kinda crazy going back to Star Fox Assault as someone who really enjoyed Kid Icarus Uprising and seeing what almost felt like prototype DNA for gameplay. Made even more surreal when researching that Masahiro Sakurai was originally considering making a Star Fox game for 3DS that would utilize the third person shooter style game play to highlight the handheld's 3D technological capability. However, Sakurai would apparently find the "Star Fox style" to be too restrictive for the gameplay he wanted to implement. So he went with Kid Icarus a franchise that had been much longer dormant.

Now look, I know this was supposed to be about Star Fox Assault, but believe when I say Kid Icarus Uprising is a fantastic game. Levels were split up into three parts: a flight rail shooter that would put your trigger finger to the test, an on-foot combat section that utilized stylus based movement, and a huge boss battle. Intersperced throughout a level is main character Pit bantering with his Goddess Palutena and villains that flesh out the characters and serve as a does of comedy.

It's crazy to say, and I'm sure it was unintentional, but I feel like I can see this game being built on the skeleton of Star Fox Assault's core mechanics. Making a character driven story of large scale proportions in the sky that would then become more intimate detailed levels on the ground that has a major focus on character interaction. Except, it manages to improve in the sections of Assault that needed more polish like its story length, its controls, and replayability.

I'm really glad we got a modern Kid Icarus game that fleshed out these characters that I guarantee most had only heard about for the first time through Smash Bros Brawl, and even though it aesthetically and gameplay wise was a soft reboot, still acknowledges the Kid Icarus games before it and the events that would appease older fans and intrigue newer ones to look into. All done in a very presentable and fun package. But it's a shame knowing that this could've been an opportunity for another franchise. A franchise that would've honestly slotted in perfectly with this style of gameplay and who have been having an identity crisis for years and seems to be now on Nintendo's self.

Going back to Star Fox Assault, while I don't think it would've converted me into the type of fan of Star Fox that waits with baited breath of hoping to see it mentioned once in a Nintendo Direct, I do see a lot of potential for it to become a thing I like. The world of the Lylat System and the anthropomorphic space-farers that inhabit it has definite appeal to reach a wide audience. The epic space battles of a Mass Effect, but with the soapy furry drama of Sonic. But it seems like the barrier of entry for Star Fox is finding that fresh idea that gets both fresh and iterative, but also attractive to new players that will grow the brand and please the existing players. And when I see how that it can be done for Kid Icarus and how close it is to Star Fox Assault, it makes me lament that we may have found that direction for franchise and let it slip away.

Sooooo yeah. Replaying Star Fox Assault after so long. I'd say the game is mostly fine to good. With the key decider, I think, for players is going to be if you got enough fun out of 5 hours worth of gameplay. Since Assault is a GameCube game, that means that its only available through second hand like eBay. And because the price for GameCube games is really jacked up, I do think its hard for me to fully recommend this game when I don't think it has one hundred dollars worth fun.

It also is just not "pure" Star Fox. Its not 64 2. Bt it isn't as radical a departure as Adventures. So I know that there's just going to be a bunch of people who don't like the new sections period, I do think it fits enough in the series that it makes its inclusion justifiable as opposed to Adventures. At the very least, I can say this is a game with a lot of potential. And we may probably never see that potential implemented in the Star Fox universe.

#star fox#star fox assault#star fox 64#star fox adventures#kid icarus uprising#fox mccloud#pit kid icarus#falco lombardi#nintendo#video games#discussion#slippy toad

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

god is a Woman

god is a woman I see this in every curving mountain range in every simple shimmering pool of clear life

I see it in every flower Popping with bright color to shine the world And make it all a little more worthwhile

I see her in the creatures the harmony of natural disaster escape plans an ensemble of unknown instruments

She's in the face of infant children the stages before they become human The cry and suffering that we learn right after birth Everyone's terrified as a newborn

I hear her in notes The composer's works of operatic tales Music is the language we've come to love

She's in the paintings Of the great kings and queens of acrylic masters of color blindness I wonder if the world is different in their eyes?

god is a woman The world is too beautiful for her to be a man

#my poem#spilled poem#writers and poets#poems on tumblr#original poem#poem#poems#short poem#poems and poetry#words words words#poetry#poetblr#dark poetry#spilled thoughts#spilled feelings#spilled writing#artists on tumblr#writing#my writing#poets on tumblr#spilled poetry#spilled ink#spilled emotions#spilled words#spilledink#writers on tumblr#poets and writers#writeblr#dark writing#creative writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

#alexanderbirchelliott#americansymphony#angelameadesoprano#brernarddamonholcomb#brianmhenry30#christefftsings#danielchiubaritone#guanchenliustudio#johnmatthewmyers#kshort111#njmattingly#Openingnight.Reviews#rhettburgen#rorothetenor#thefrontrownyc

0 notes

Text

"Ah, I truly can only imagine." He gave a wry chuckle and perhaps cracked a small grin. "Though I surely doubt you or any other have much reason to visit a land as barren as my own." The only faces that passed through were soldiers and merchants and he was grateful for that. Any more and it may spell disaster on his end. But she was correct...after all he was back here after swearing so long ago he'd never return for too long. "Manuela," Once again he seemed overtaken by a nostalgia. Back then, both had joked about the woman's voice being enough to steal them away from one another. "To be more extravagant than even that? Adrestia truly leaves no energy to spare when it comes to the events it puts on. I don't recall ever having seen such beautifully decorated outfits in my life...that there was even more past that.." For a moment he hums and then stifles back another chuckle. "Unless you'd count the crude actings of soldiers around a fire, we have no such institute. The castle does have its dancers but hardly is it ever to the tune of our stories." "I imagine it'd be a difficult feat. Not to say that the stories told by Adrestian operas are simple, by no means are they...but take for example, my ancestor, Laetitia Zoe Gautier." He hand a hand over his chest fondly. "A woman of no house, simply a knight of many balancing between where ever the King or Duke Fraldarius needed her. Fighting so fiercely without even her relic at the time. Between the true history behind her, the rumors spread and the secrets of hers kept by our house, there would be a great number of ways to tell her story...more than that, the battles... goddess, to present anything of that sort to a Faerghan crowd, the production would most certainly need to appeal to them there. Grand moves that captivated even the eldest viewer yet things children themselves could replicate. Songs not too far from the tales heard long before yet not so reminiscent as to be moot to hear again." There was a fondness in the way he swayed as he spoke. "But perhaps the biggest hurdle of all...convincing any of the greats who craft the instruments used in such things to make their way to Faerghans." A hand rested on his hip and he grimaced. "I've a collection of my own and perhaps out of all...only one or two are properly in tune. It's far too precious a selection to be carted off to Enbarr to be fixed but all contacts I've had regarding such things have either not responded or treated such inquiries as a joke." He snapped his fingers and now, it truly was a smile that he lent her way. "If you wish to bring about such a renaissance, such problems must be ironed out. An opera can't well function without the ensemble. Tailors and armorers already have such intertwined relationships that costuming for our tales would be of no issue and with the cities having been so recently rebuilt, there are many a venue to choose from should it be a traveling affair..." A thought crosses his mind and he hesitates for a moment before his eyes close. "Should it be in the spirit of the Mittlefrank...I suppose my ill used villa would be of use. Not so close to the castle that it might dissuade commoners, yet not so far that noblemen and women alike would see it as too beneath them to check out." He couldn't help but laugh at himself. What an absurd idea. Of course it was possible but it'd take years between teaching and recruiting as well as organizing such things. Faerghan stories were not hard to find but few were written in such a way that it was easy to turn into an operatic affair. "Ah...what a wonderful idea it would be. Such a grand stage in Fhirdiad is much too far off."

♫ 𝄈 an operatic appraisal of high regard.

#[ic]#[an operatic appraisal of high regard]#[support: dorothea]#//you said yap and matthias said o7

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Many operas end like Tosca with the sudden descent of the hero to some nether realm. Don Giovanni, however, (as in Zeffirelli's production for Covent Garden), tends simply to disappear amid whirling clouds of stage smoke as the chorus of off-stage demons promise him worse torments below. In Vienna, however, Cesare Siepi ended his admirable interpretation standing on a stagelift which, as so often happens, stuck halfway down, leaving his head and shoulders visible to the audience but not the rest of him. The technicians' efforts merely revealed the operation of one of the great laws governing opera disasters -- that the most that can be hoped for is to restore the status quo ante -- that is, they merely brought him back up again. Siepi then amazed the public by refusing simply to walk off and with courageous professionalism challenged the lift operator to a second attempt. Of course exactly the same thing happened, and amid the shocked silence of the Staatsoper a single voice rang out -- it is said in Italian -- ‘Oh my God, how wonderful -- hell is full.’

Great Operatic Disasters, Hugh Vickers (x)

#great operatic disasters#don giovanni#cesare siepi#theatre history#or lore#dispatches from the opera dumpster#cabinet of queue riosities

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

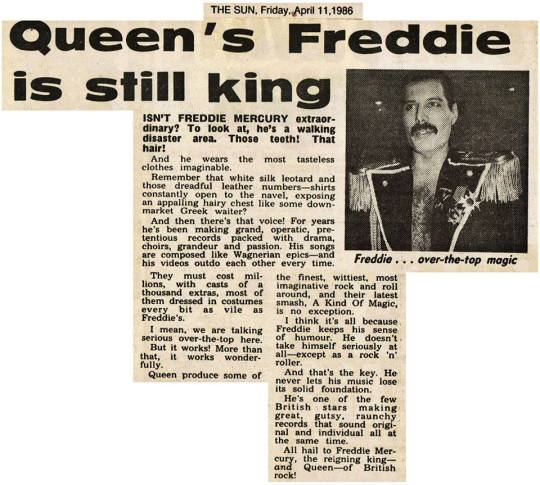

The Sun - April 11, 1986

(x)

Queen’s Freddie is still king

ISN'T FREDDIE MERCURY extraordinary? To look at, he's a walking disaster area. Those teeth! That hair!

And he wears the most tasteless clothes imaginable.

Remember that white silk leotard and those dreadful leather numbers — shirts constantly open to the navel, exposing an appalling hairy chest like some down-market Greek waiter?

And then there's that voice! For years he's been making grand, operatic, pretentious records packed with drama, choirs, grandeur and passion. His songs are composed videos like Wagnerian epics — and his videos outdo each other every time.

They must cost millions, with casts of a thousand extras, most of them dressed in costumes every bit as vile as Freddie's.

I mean, we are talking serious over-the-top here.

But it works! More than that, it works wonderfully.

Queen produce some of the finest, wittiest, most imaginative rock and roll around, and their latest smash, A Kind Of Magic, is no exception.

I think it's all because Freddie keeps his sense of humour. He doesn't take himself seriously at all — except as a rock 'n' roller.

And that's the key. He never lets his music lose its solid foundation.

He's one of the few British stars making great, gutsy, raunchy records that sound original and individual all at the same time.

All hail to Freddie Mercury, the reigning king — and Queen — of British rock!

[Photo caption: Freddie… over-the-top magic]

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

okay but imagine these two possible aus.

one. order 66 didn't happen and palps was overthrown and killed by Fox who was tired of his shit, clones get their rights and attachment is allowed in the order.

two. Obi-Wan as Anakin's padawan and the disaster lineage in chaos like Ahsoka being Anakin's master and Obi-Wan being thirteen or fourteen when the war starts and beibg taken as a padawan by Anakin at the age of seven or eight and again no order 66.

I love the AU where Anakin doesn’t turn, and I think about it every day, though I do think for the sake of operatic tragedy the story has more value as it is

I love the idea of the disaster lineage being inverted—Ahsoka would be a GREAT master, but I have a hard time imagining Anakin being Obi-Wan’s master 😅😅 I feel like 13 year old Obi-Wan would still be trying to parent Anakin

#hayden christensen#anakin skywalker#obi wan kenobi#star wars#star wars prequels#ewan mcgregor#anakin#kenobi series#star wars fandom#obi wan and anakin#answered asks#ask me anything

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sleuth of Ming Dynasty: A Primer

Aren’t you missing a “the”?

Depends on which promo material you look at. The Chinese title is The Fourteenth Year of Chenghua (Chenghua = the current Emperor’s reign), which is also the name of the BL novel the show is based on.

It’s based on a BL novel, you say? Is it Gay?

Yes and no. This is a Chinese production, so as with The Untamed they have to have plausible deniability of gayness for the censors. That said, the two main characters quickly end up living together, they risk their lives for each other, and at one point they run towards each other in slow motion while a highlights reel of their relationship plays. There’s kabedon, a bath-time encounter, and domesticity up the wazoo. From interviews it sounds like the actors fully expected their characters to be shipped together and were happy to encourage that.

Will this fill the aching void in my heart left by The Untamed?

Possibly? It doesn’t have the operatic levels of emotional intensity of The Untamed—there’s less soul-searching and more mystery-solving. The tone is often humorous, and while there are definitely moments of angst, you probably won’t be weeping into your popcorn. On the other hand, the production design is gorgeous (except that the city apparently only has one street—but it looks great!) and the cast is good-looking and have great chemistry, so it might just scratch that itch.

What makes this show special?

In short, food and found family. There are many loving close-ups of food being prepared, cooked, and eaten. And there are people who come together and make a family and then they all eat happily around a big table and it’s just ... sniff. Throw in some characters you’ll want to hug and protect, and you’ve got yourself a new obsession show.

Who are these characters?

Tang Fan is a foodie, a brilliant scholar, and a human disaster. His job is investigating court cases as a local magistrate, and he supplements his meagre salary by writing erotic novels on the sly. He whines about literally everything, but he also has a big heart and a sunny smile.

Sui Zhou is the taciturn ex-soldier to Tang Fan’s effusive string bean. His time in the army gave him impressive martial-arts skills and also PTSD. Now he’s part of the Emperor’s police force (the Embroidered Uniform Guards, who are not nearly as colourful as that sounds), so naturally he and Tang Fan end up investigating cases together. For all his grumpy eye-rolling, at heart Sui Zhou is a big softie who wants to make sure everyone is well fed.

Wang Zhi is the youngest palace eunuch ever to rise to his position (he’s supposed to be 17(!), but clearly the actor is in his 20s) as the Emperor’s right-hand man. He’s morally flexible (to put it nicely) in his pursuit of the Emperor’s interests, and at first you’ll think he’s sketchy AF. But before too long he’ll have schemed his way into your heart somehow.

Dong-er is my perfect child a cheeky preteen servant who basically gets adopted by Tang Fan and Sui Zhou (though it might be more accurate to say she adopts them). She has a genius brain, a bottomless stomach, and a fearless streak that sometimes gets her into dangerous situations. This is Not Okay, because Dong-er must be protected at all costs. Fortunately, Sui Zhou and Tang Fan seem to understand this.

Duo Erla is a hard-riding Oirat plainswoman who’s come to the city with her liegeman-translator-bodyguard Wuyun and a sizeable chunk of the show’s horse budget. For a tiny woman, she packs a lot of menace. But even her annoyance and Wuyun’s scorn prove to be no match for the power of Tang Fan’s puppy eyes.

Pei Huai is a local doctor who’s a fan of illegal dissection and New World vegetables. As a friend of Tang Fan’s, he often gets called in to determine the victim’s cause of death. He and Tang Fan bicker like a pair of friends who’ve known each other longer than they can remember.

Ding Rong is Wang Zhi’s underling and a one-man Ming Dynasty CSI. To be honest I barely noticed him at first, but then in one ep he turned up in a black ninja outfit and beat up some baddies, and I thought, “Ding Rong, you interest me strangely.”

Mama Cui is the madam of the well-appointed Huanyi (“Joyous”) Brothel, in which Wang Zhi happens to own shares. This photo, of course, is not her. This is Tang Fan pretending to be Mama Cui for a case. It’s not very convincing—he’s so much prettier than she is.

There are lots of other great characters, but I’ve only got so much space here.

Okay, I’m sold. Where can I watch this?