#p. cotter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

F.8.4 Aren’t the enclosures a socialist myth?

The short answer is no, they are not. While a lot of historical analysis has been spent in trying to deny the extent and impact of the enclosures, the simple fact is (in the words of noted historian E.P. Thompson) enclosure “was a plain enough case of class robbery, played according to the fair rules of property and law laid down by a parliament of property-owners and lawyers.” [The Making of the English Working Class, pp. 237–8]

The enclosures were one of the ways that the “land monopoly” was created. The land monopoly referred to feudal and capitalist property rights and ownership of land by (among others) the Individualist Anarchists. Instead of an “occupancy and use” regime advocated by anarchists, the land monopoly allowed a few to bar the many from the land — so creating a class of people with nothing to sell but their labour. While this monopoly is less important these days in developed nations (few people know how to farm) it was essential as a means of consolidating capitalism. Given the choice, most people preferred to become independent farmers rather than wage workers (see next section). As such, the “land monopoly” involves more than simply enclosing common land but also enforcing the claims of landlords to areas of land greater than they can work by their own labour.

Needless to say, the titles of landlords and the state are generally ignored by supporters of capitalism who tend to concentrate on the enclosure movement in order to downplay its importance. Little wonder, for it is something of an embarrassment for them to acknowledge that the creation of capitalism was somewhat less than “immaculate” — after all, capitalism is portrayed as an almost ideal society of freedom. To find out that an idol has feet of clay and that we are still living with the impact of its origins is something pro-capitalists must deny. So are the enclosures a socialist myth? Most claims that it is flow from the work of the historian J.D. Chambers’ famous essay “Enclosures and the Labour Supply in the Industrial Revolution.” [Economic History Review, 2nd series, no. 5, August 1953] In this essay, Chambers attempts to refute Karl Marx’s account of the enclosures and the role it played in what Marx called “primitive accumulation.”

We cannot be expected to provide an extensive account of the debate that has raged over this issue (Colin Ward notes that “a later series of scholars have provided locally detailed evidence that reinforces” the traditional socialist analysis of enclosure and its impact. [Cotters and Squatters, p. 143]). All we can do is provide a summary of the work of William Lazonick who presented an excellent reply to those who claim that the enclosures were an unimportant historical event (see his “Karl Marx and Enclosures in England.” [Review of Radical Political Economy, no. 6, pp. 1–32]). Here, we draw upon his subsequent summarisation of his critique provided in his books Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor and Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy.

There are three main claims against the socialist account of the enclosures. We will cover each in turn.

Firstly, it is often claimed that the enclosures drove the uprooted cottager and small peasant into industry. However, this was never claimed. As Lazonick stresses while some economic historians “have attributed to Marx the notion that, in one fell swoop, the enclosure movement drove the peasants off the soil and into the factories. Marx did not put forth such a simplistic view of the rise of a wage-labour force … Despite gaps and omission in Marx’s historical analysis, his basic arguments concerning the creation of a landless proletariat are both important and valid. The transformations of social relations of production and the emergence of a wage-labour force in the agricultural sector were the critical preconditions for the Industrial Revolution.” [Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, pp. 12–3]

It is correct, as the critics of Marx stress, that the agricultural revolution associated with the enclosures increased the demand for farm labour as claimed by Chambers and others. And this is the whole point — enclosures created a pool of dispossessed labourers who had to sell their time/liberty to survive and whether this was to a landlord or an industrialist is irrelevant (as Marx himself stressed). As such, the account by Chambers, ironically, “confirms the broad outlines of Marx’s arguments” as it implicitly acknowledges that “over the long run the massive reallocation of access to land that enclosures entailed resulted in the separation of the mass of agricultural producers from the means of production.” So the “critical transformation was not the level of agricultural employment before and after enclosure but the changes in employment relations caused by the reorganisation of landholdings and the reallocation of access to land.” [Op. Cit., p. 29, pp. 29–30 and p. 30] Thus the key feature of the enclosures was that it created a supply for farm labour, a supply that had no choice but to work for another. Once freed from the land, these workers could later move to the towns in search for better work:

“Critical to the Marxian thesis of the origins of the industrial labour force is the transformation of the social relations of agriculture and the creation, in the first instance, of an agricultural wage-labour force that might eventually, perhaps through market incentives, be drawn into the industrial labour force.” [Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy, p. 273]

In summary, when the critics argue that enclosures increased the demand for farm labour they are not refuting Marx but confirming his analysis. This is because the enclosures had resulted in a transformation in employment relations in agriculture with the peasants and farmers turned into wage workers for landlords (i.e., rural capitalists). For if wage labour is the defining characteristic of capitalism then it matters little if the boss is a farmer or an industrialist. This means that the “critics, it turns out, have not differed substantially with Marx on the facts of agricultural transformation. But by ignoring the historical and theoretical significance of the resultant changes in the social relations of agricultural production, the critics have missed Marx’s main point.” [Competitive Advantage on the Shop Floor, p. 30]

Secondly, it is argued that the number of small farm owners increased, or at least did not greatly decline, and so the enclosure movement was unimportant. Again, this misses the point. Small farm owners can still employ wage workers (i.e. become capitalist farmers as opposed to “yeomen” — an independent peasant proprietor). As Lazonick notes, ”[i]t is true that after 1750 some petty proprietors continued to occupy and work their own land. But in a world of capitalist agriculture, the yeomanry no longer played an important role in determining the course of capitalist agriculture. As a social class that could influence the evolution of British economy society, the yeomanry had disappeared.” Moreover, Chambers himself acknowledged that for the poor without legal rights in land, then enclosure injured them. For “the majority of the agricultural population … had only customary rights. To argue that these people were not treated unfairly because they did not possess legally enforceable property rights is irrelevant to the fact that they were dispossessed by enclosures. Again, Marx’s critics have failed to address the issue of the transformation of access to the means of production as a precondition for the Industrial Revolution.” [Op. Cit., p. 32 and p. 31]

Thirdly, it is often claimed that it was population growth, rather than enclosures, that caused the supply of wage workers. So was population growth more important than enclosures? Given that enclosure impacted on the individuals and social customs of the time, it is impossible to separate the growth in population from the social context in which it happened. As such, the population argument ignores the question of whether the changes in society caused by enclosures and the rise of capitalism have an impact on the observed trends towards earlier marriage and larger families after 1750. Lazonick argues that ”[t]here is reason to believe that they did.” [Op. Cit., p. 33] Overall, Lazonick notes that ”[i]t can even be argued that the changed social relations of agriculture altered the constraints on early marriage and incentives to childbearing that contributed to the growth in population. The key point is that transformations in social relations in production can influence, and have influenced, the quantity of wage labour supplied on both agricultural and industrial labour markets. To argue that population growth created the industrial labour supply is to ignore these momentous social transformations” associated with the rise of capitalism. [Business Organisation and the Myth of the Market Economy, p. 273]

In other words, there is good reason to think that the enclosures, far from being some kind of socialist myth, in fact played a key role in the development of capitalism. As Lazonick notes, “Chambers misunderstood” the “argument concerning the ‘institutional creation’ of a proletarianised (i.e. landless) workforce. Indeed, Chamber’s own evidence and logic tend to support the Marxian [and anarchist!] argument, when it is properly understood.” [Op. Cit., p. 273]

Lastly, it must be stressed that this process of dispossession happened over hundreds of years. It was not a case of simply driving peasants off their land and into factories. In fact, the first acts of expropriation took place in agriculture and created a rural proletariat which had to sell their labour/liberty to landlords and it was the second wave of enclosures, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that was closely connected with the process of industrialisation. The enclosure movement, moreover, was imposed in an uneven way, affecting different areas at different times, depending on the power of peasant resistance and the nature of the crops being grown (and other objective conditions). Nor was it a case of an instant transformation — for a long period this rural proletariat was not totally dependent on wages, still having some access to the land and wastes for fuel and food. So while rural wage workers did exist throughout the period from 1350 to the 1600s, capitalism was not fully established in Britain yet as such people comprised only a small proportion of the labouring classes. The acts of enclosure were just one part of a long process by which a proletariat was created.

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

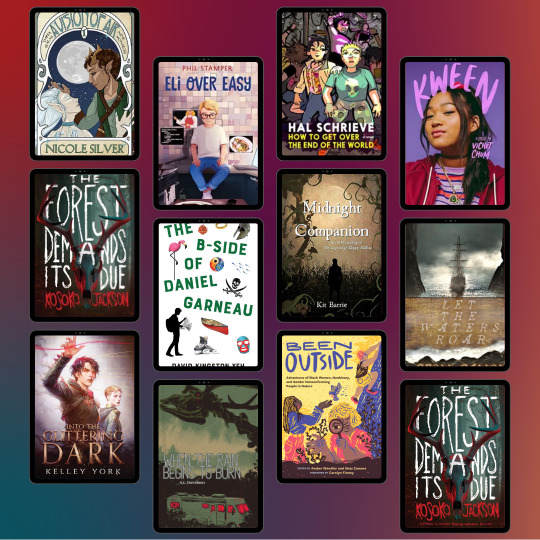

🌈 Good morning and happy Wednesday, my bookish bats! You didn't think that tiny "queer books coming out this fall" guide was ALL there was, did you? Here are a FEW of the stunning, diverse queer books you can add to your TBR this month. Happy reading!

❤️ A Vision of Air by Nicole Silver 🧡 Eli Over Easy by Phil Stamper 💛 How to Get Over the End of the World by Hal Schrieve 💚 Kween by Vichet Chum 💙 The Forest Demands its Due by Kosoko Jackson 💜 The B-Side of Daniel Garneau by David Kingston Yeh ❤️ Midnight Companion by Kit Barrie 🧡 Let the Waters Roars by Geonn Cannon 💛 Into the Glittering Dark by Kelley York 💙 When the Rain Begins to Burn by A.L. Davidson 💜 Been Outside by Amber Wendler & Shaz Zamore 🌈 The Forest Demands Its Due by Kosoko Jackson

❤️ A Necessary Chaos by Brent Lambert 🧡 The Spells We Cast by Jason June 💛 Pluralities by Avi Silver 💚 Salt the Water by Candice Iloh 💙 Beholder by Ryan La Sala 💜 This Pact is Not Ours by Zachary Sergi ❤️ Dragging Mason County by Curtis Campbell 🧡 Menewood by Nicola Griffith 💛 Mary and the Birth of Frankenstein by Anne Eekhout 💚 The Dead Take the A Train by Cassandra Khaw & Richard Kadrey 💙 Bloom by Delilah S. Dawson 💜 Let Me Out by Emmett Nahil and George Williams

🌈 In the Form of a Question: the Joys and Rewards of a Curious Life by Amy Schneider ❤️ Songs of Irie by Asha Ashanti Bromfield 🧡 A Haunting on the Hill by Elizabeth Hand 💛 Being Ace by Madeline Dyer 💚 Charming Young Man by Eliot Schrefer 💙 The Glass Scientists by S.H. Cotugno 💜 The Fall of Whit Rivera by Crystal Maldonado ❤️ By Any Other Name by Erin Cotter 🧡 Brooms by Jasmine Walls and Teo DuVall 💛 Stars in Your Eyes by Kacen Callender 💚 Shoot the Moon by Isa Arsen 💙 The Bell in the Fog by Lev A.C. Rosen

🌈 Brainwyrms by Alison Rumfitt ❤️ Family Meal by Bryan Washington 🧡 A Murder of Crows by Dharma Kelleher 💛 A Light Most Hateful by Hailey Piper 💚 Love at 350° by Lisa Peers 💙 Greasepaint by Hannah Levene 💜 The Christmas Swap by Talia Samuels ❤️ Mate of Her Own by Elena Abbott 🧡 Mistletoe and Mishigas by M.A. Wardell 💛 Elle Campbell Wins Their Weekend by Ben Kahn 💚 All That Consumes Us by Erica Waters 💙 If You’ll Have Me by Eunnie

❤️ Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Lillah Lawson and Lauren Emily Whalen 🧡 10 Things That Never Happened by Alexis Hall 💛 It’s a Fabulous Life by Kelly Farmer 💚 Let the Dead Bury the Dead by Allison Epstein 💙 These Burning Stars by Bethany Jacobs 💜 The Goth House Experiment by SJ Sindu ❤️ Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant by Curtis Chin 🧡 Mudflowers by Aley Waterman 💛 Here Lies Olive by Kate Anderson 💚 Fire From the Sky by Moa Backe Åstot, trans. by Eva Apelqvist 💙 Iris Kelly Doesn’t Date by Ashley Herring Blake 💜 On the Same Page by Haley Cass

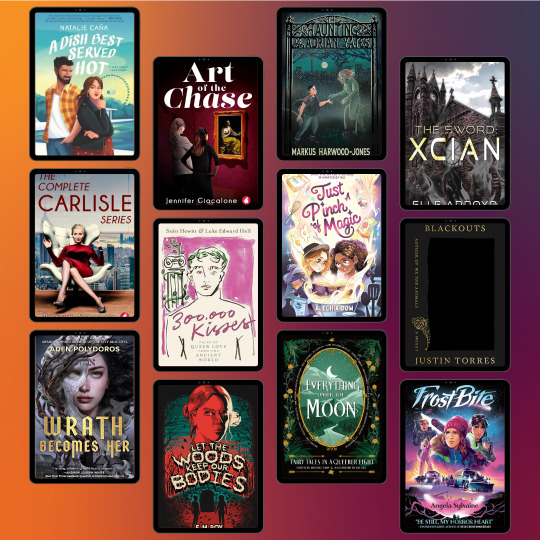

❤️ A Dish Best Served Hot by Natalie Caña 🧡 Art of the Chase by Jennifer Giacalone 💛 The Haunting of Adrian Yates by Markus Harwood-Jones 💚 The Sword: Xcian by Elle Arroyo 💙 The Complete Carlisle Series by Roslyn Sinclair 💜 300,000 Kisses by Sean Hewitt and Luke Edward Hall ❤️ Just a Pinch of Magic by Alechia Dow 🧡 Blackouts by Justin Torres 💛 Wrath Becomes Her by Aden Polydoros 💚 Let the Woods Keep Our Bodies by E.M. Roy 💙 Everything Under the Moon: Fairy Tales in a Queerer Light edited by Michael Earp ❤️ Frost Bite by Angela Sylvaine

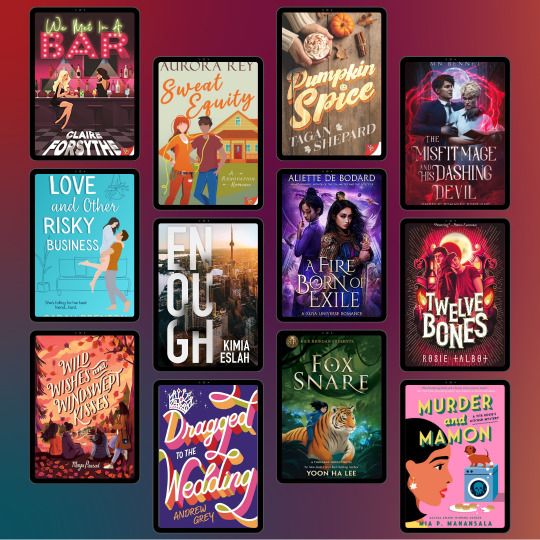

🧡 We Met in a Bar by Claire Forsythe 💛 Sweat Equity Aurora Rey 💚 Pumpkin Spice by Tagan Shepard 💙 The Misfit Mage & His Dashing Devil by M.N. Bennet 💜 Love and Other Risky Business by Sarah Brenton ❤️ Enough by Kimia Eslah 🧡 A Fire Born of Exile by Aliette de Bodard 💛 Twelve Bones by Rosie Talbot 💚 Wild Wishes and Windswept Kisses by Maya Prasad 💙 Dragged to the Wedding by Andrew Grey 💜 Fox Snare by Yoon Ha Lee ❤️ Murder and Manon by Mia P. Manansala

#queer book recs#queer fiction#queer books#queer#books#book list#books to read#lgbt writers#batty about books#battyaboutbooks

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

🔬 High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Brain Health: Mechanisms and Benefits 🧠 --- A recently published review article titled "HIITing the brain with exercise: mechanisms, consequences and practical recommendations" in The Journal of Physiology explores the profound impact of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) on brain health. This comprehensive review elucidates the underlying mechanisms and practical applications of HIIT, highlighting its potential cognitive benefits. --- Key Highlights: Neurovascular Function: HIIT significantly enhances neurovascular function by improving blood flow and nutrient delivery to the brain, which is crucial for maintaining cognitive function and overall brain health. --- Neuroprotective Factors: The training method increases the production of neuroprotective factors, such as Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF). BDNF supports the growth, survival, and differentiation of neurons, playing a critical role in brain plasticity and cognitive function. --- Cognitive Benefits: Regular HIIT sessions are associated with improvements in memory, executive function, and processing speed. These cognitive enhancements are particularly beneficial for aging populations and individuals at risk of neurodegenerative diseases. --- Practical Recommendations: The review provides detailed guidelines for safely and effectively incorporating HIIT into fitness routines. It emphasizes the importance of tailoring programs to individual fitness levels and health conditions to maximize benefits and minimize risks. -- Future Research Directions: The article suggests various areas for future research to further explore the neurobiological mechanisms behind HIIT's cognitive benefits. It highlights the need to optimize training protocols for different populations to achieve the best outcomes. --- Importance of the Study: The findings underscore the potential of HIIT as a non-pharmacological intervention to enhance cognitive function and prevent cognitive decline. Incorporating HIIT into regular exercise routines can significantly contribute to brain health, making it an invaluable tool for both healthcare professionals and fitness enthusiasts. --- 1. Calverley, T.A., Ogoh, S., Marley, C.J., Steggall, M., Marchi, N., Brassard, P., Lucas, S.J.E., Cotter, J.D., Roig, M., Ainslie, P.N., Wisløff, U. and Bailey, D.M. (2020), HIITing the brain with exercise: mechanisms, consequences and practical recommendations. J Physiol, 598: 2513-2530. doi: 10.1113/JP275021. Epub 2020 Jun 1. PMID: 32347544.

#HIIT#BrainHealth#CognitiveFunction#Neuroprotection#FitnessScience#ExercisePhysiology#HealthAndWellness#Research#Neuroscience#HealthyAging#ScientificResearch#BrainFitness#PhysicalExercise#CognitiveHealth#Neuroplasticity#HealthResearch#WorkoutScience#ExerciseResearch#SportsScience#Physiology#MentalHealth#ScientificStudy#BrainTraining#neurogenesis#ResearcherLife

0 notes

Text

Read More 2024 Curious Incident of the Dog on the Cover.

A book with a dog on the cover.

Classics White Fang by Jack London

Fiction A Dog's Purpose by W. Bruce Cameron The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon Dog Boy by Eva Hornung The Lucky Dog Matchmaking Service by Beth Kendrick

Mystery Two Parts Sugar, One Part Murder by V.M. Burns Murder, She Barked by Krista Davis Murder at the Beacon Bakeshop by Darci Hannah Arsenic and Adobo by Mia P. Manansala The Department of Sensitive Crimes by Alexander McCall Smith The Right Side by Spencer Quinn The Dog Park Club by Cynthia Robinson

Romance The Happy Ever After Playlist by Abby Jiminez Maggie Moves On by Lucy Score

Biography Hyperbole and a Half by Allie Brosh

Non-Fiction All Creatures Great and Small by James Herriot Olive, Mabel & Me by Andrew Cotter Marley and Me by John Grogan

0 notes

Text

Walking with Music by Sam Cotter

‘Walking with Music’ is a personal account of walks around Cardiff’s musical venues, whilst listening to music. The areas to, from and around these places gave me expansive coverage of Cardiff as well as extensive visual, olfactory and, occasional, audible data. I am an avid listener to music and wondered whether my perception, awareness, emotion (mood), and my tempo would change depending on the type of music, the surroundings, and the behaviours and actions I saw en route. Certain observations of my walk could have been attained without the need for headphones, this is in part to me making a mundane activity more enjoyable, but as Sloboda and O’Neill (2001, p. 421) suggest “Music becomes part of the construction of the emotion itself through the way in which individuals orientate to it, interpret it, and use it to elaborate.” With that in mind, certain observations involving memory recall, nostalgia and awareness were of particular interest.

I restricted auditory awareness and heightened my internalised experience of the walk. I act as a flâneur and rhythm-analyst, who does not listen to the streets, but who picks his own “narrative” conducted by the rhythmic sounds of the music, the “audio drift.” (Moles 2015, p.3) I join the pedestrian flows, wander and respond to the sights and smells on offer whilst acknowledging “Anachrony” of places I have visited before. (Walter 1999) I follow this planned musical route and I am led to points of interest, of personal association, where they “become entangled with other lines both past and present, real and imagined, and this entanglement… is both part of and productive of place” (Moles and Saunders 2015, p.17)

Given the nature of my walks, I will indebt to keep a chronological descriptive account, but this may not be the same-day experience. Italicised field-notes, images, and a playlist will be used to provide you with a detailed account of the walk.

I am located on Mundy Place a literal stone’s throw away from the Mackintosh Pub. I take a right, away from the pub, and head down Woodville Road. I adjust my headphones on my door-step and hit play when I start my walk, the cloud cover gives a greyish hue which enwraps the surrounding buildings with a displeasing taint.The terraced housing, letting agencies, food outlets and smaller business are located along the walk and the smell of uncollected rubbish, strewn on the pavement, was instantly noticeable. Back (2017) suggests a certain ‘personification’ can be established on walks, I note: Today I notice some students are leaving their house with bags on their backs, there’s up for rent signs dotted around, rubbish discarded outside front door steps and house viewings. This sort of day to day action and behaviour are not uncommon and my attention only averts when an elderly couple appear, noting that they do not ‘fit in’ to the surrounding environment. I have to be pretty attentive whilst I am doing this, on two of the days I note that the music does not seem to be conducting my movements or emotions down Woodville and realise I have to be conscious of slip roads and the main road as I am not able to hear oncoming traffic. Bunt and Pavilcevic (2001) suggest that music can “trigger” an emotional response as it becomes associated with a certain action or behaviour. In my case, the music seems to play in the background on these occasions: I am much more concerned with how I should navigate the environment than paying attention to the music; however, I do note that on one occasion the classical music, my work playlist, keeps me focused down Woodville today.

I walk off from Woodville Road and make the walk along Crwys Road heading to Albany Road. I have only frequented Albany a handful of times; I am struck with how busy it becomes on Albany Road, a combination of the busy shops that spill with bodies onto the pavement and the swathes of people negotiating their bodies around others. It is a stop – start pace down Albany and on two occasions note: I am no longer setting a pace, but rather, caught between families, groups and individuals and Today I feel like I am flowing with pedestrians a lot more. Even with the music in my ears, I am happily manoeuvring with strangers, as Bauman (1994, p. 141) suggests “playing the game of I-see-you-you-see-me-not.” Yet, when the upbeat tempo of a track called ‘Ivoire’ starts to play, I sync along to the beat, experiencing a joyous break from those around me. I stride without consequence, joining in with the singing and nod along appreciatively. ‘Ivoire’ internalises my movement, emotion and perception as I “disengage [with] my surroundings” (Sloboda and O’Neill 2001, p. 422).

There’s a contrast when the outside world creeps in. The bustling tarpaulin above the church catches me off guard and between the occasional skipping of tracks, and quieter moments in songs, the outside world creeps in. The congestion, the smell of traffic and the conversations can sometimes be unnoticed by the music. When noise could be heard, it unfastens my private thoughts and quickly situates me. Such a scene is evident in the following notes: There is a guy across the road with a megaphone, I hear a few words before the next track begins. He is protesting and some are caught, including myself, idly watching. When the next track hits, there’s a weird juxtaposition – I’m observant of those who are caught up in his action, yet I can no longer hear what he is saying. A track called ‘Discovery at Night’ plays, I note the scene is ‘ugly’ not to say Albany is ugly but the gesticulated protest, a scattering of bodies and worn stone backdrop contrasts to the serene music which over-powers and leads me to tail-off towards the Globe. For a moment, the noise crept through and grabbed my ‘autonomy’ (Kusenbach 2003, p.476). I, like others, became interested in the scene unfolding and was “disturbed” (Scherer and Zetner 2001) when the megaphone infiltrated between the tracks. However, the music did not surrender my attention any longer and allowed me to disembark from the scene.

I carry on down Albany. The Globe is a brown painted building which sits into the pavement, looking down from the traffic lights it is hidden and impossible to recognise. During the day, it blends into the buildings on the walk and can go easily unnoticed. The Globe is the first venue on my walk which has some historical relevance for me. As Moles and Saunders (2015, p.8) put it, “Place… is a product of what people did there that made the place significant.” On one of the days where I strolled towards the globe, I reflected on this – It reminds me of gigs I have gone to in the past. I remember seeing a band called ‘cabbage’ in the venue. It takes me to a time and situation when I participated in the activity of the venue. It becomes particularly poignant on my walk as place, particularly these venues I pass, are in the make-up of my social milieu.

I try to stick closely to my route through Glenroy Street, Kincraig Street, and Northcote Street which leads me to Salisbury Road. At times I am confident listening to my music, muttering chorus lines and verses, but realise I have taken a wrong turn. I look out above for signs and take a minute to reset myself. Over the next few days I familiarise myself with school playgrounds, corner shops, food outlets and the town hall clock. Distinct features lead to a type of disconnection to my walk, on the last day I happily walk the streets; it is quiet en route and I enjoy Gerry Cinnamons album which makes me wander aimlessly. Along the route, however, I bumped into a friend as I neared Salisbury Road. I have become so engaged with my walk that I do not anticipate this. It ‘intrudes’ on my activity (Kusenbach 2003) – I bump into a friend and have a quick chat, not anticipating this, noise from cars pass-by and I hesitantly join in on conversation. The music seemed to put me into a trance on this journey and it is the first time where I see it being a hindrance to such social encounters.

I head under the bridge and join up to Salisbury Road: A track called ‘Devoted to U’ comes on, a particular favourite of mine and I am suddenly much more engaged with my music, I take a break from note taking until I get to Guildford Crescent. It was a conscious decision and one of putting my “body in motion” (Knowles 2017, p. 197) without the overbearing need to take notes.

This is the first encounter of Gwdihw I’ve had following the closure in late January. I took part in the picketing, the protest march and wrote an article of disdain against the closure of businesses on Guildford Crescent. I did so because it meant a lot to a musical community in Cardiff. I wrote at the time that “Gwdihw… had represented a place for punters of all ages to dance, listen and share life-stories within the colourful walls.” (Quench 2019) My fieldnotes illustrate this further: To see it still recognisable but not operating as it did brought on some nostalgia and sadness. The music upbeat, a familiar sound in the venue, is only heard in my ears. The RIP etched on the whiteboard looks like the last act on the ‘What’s On” sign.

The overriding sense that Gwdihw is left standing, empty and uneventful leaves me disheartened. Such abandonment, as Glass (Holgersson 2017, p. 76) illustrates are “Ghost[s]… of everyday life, reminding him of seemingly good old days” this description resonated with me on that day.

I make my way down Bute Terrace towards Jacob’s (Jacob’s Antiques). The rumble of the train overhead echoes and for a split second replaces the song ‘belter’. Jacob’s holds the greatest significance on my walk-through Cardiff. I have worked here, organised various nights and been a party-goer here. I was first drawn here by the music and now it has played a huge part into who I have met, worked with, and other experiences in Cardiff. I am moved slightly by the song here, a slow reflexive song called ‘experience’ takes hold and allows me to enjoy the quieter surroundings. I could be going too far by saying it has shaped me as an individual, but I certainly would not disagree that borne out from the music here, as Scherer and Zetner (2001) suggest, “it has shaped social encounters in my life.”

Womanby Street stands as the alternative, you have to go and find it amongst the busy streets of Cardiff and the allure of popular spots. These areas, as Hall and Smith (2017) alludes to, are “squirreled away.” Hidden away from St Mary’s Street is Womanby St, towered by the principality stadium in the background, it is quiet, cobbled and vibrant. I plodded down the street, admiring the mural that sits on Clwb Ifor bach, I feel at ease. I’m immersed in the tunes of Folamour. Up ahead a dancer performs outside the gatekeeper, it seems appropriate to how I find this area: niche and exciting. As I move up the street, I am regurgitated back onto Castle Street: Leaving behind Womanby St, I head onto Castle Street with the cars, tourists and pedestrians collecting in the environment. Womanby St doesn’t spill onto the road, instead it lets you exit its street unprepared by the invasion of activity.

I decided to finish my walk through Bute Park. The contrasting venues, streets and sights have all had everything in common: music. The music commands, distracts, and comforts on this walk and what ‘Walking with Music’ keyed into was the ‘imagination’, the emotional and physical interpretation of sound and the self-reflexive experience. (Walter 1999) I note finally: I take off my headphones to adjust the strap, I hear the birds, the wind and the conversation between runners. I put my headphones back on, ‘That’s Entertainment’ by the Jam plays - it uplifts me, I smile and tap away on the way home.

Playlist

01/03/2019 Folamour - Umami Album & Ordinary Drugs A mixture of soul, funk, hip-hop and jazz influences on a predominantly House - disco producer record.

02/03/2019 Ludovico Einaudi Classical music with introspective undertones and blissful structures

04/03/2019 *Gerry Cinnamon Working class Singer - Songwriter from Glasgow. Poetic - anthems with upbeat folk writing. Followed by a mixture of rock, indie and alternative bands.

*To note on this day the selected music ran short of the walk. Spotify selected previous favourites of mine.

Bibliography

Back, L. 2017. Marchers And Steppers: Memory, City Life and Walking. IN Walking Through Social Research.

Bauman, Z. 1994. Desert Spectacular. IN The Flâneur by Keith Tester.

Bunt, L. and Pavilcevic, M. 2001.Music And Emotion: Perspectives From Music Therap. IN Music and Emotion.

Hall, T. and Smith, R, J. 2017. Urban outreach as sensory walking. IN Walking Through Social Research.

Holgersson, H. 2017. Keep Walking: Notes on How to Research Urban Pasts and Futures. IN Walking Through Social Research.

Knowles, C. 2017. Walking W8 In Manolos. IN Walking Through Social Research.

Kusenbach, M. 2003. Street Phenomenology: The go-along as ethnographic research tool. Ethnogaphy.

Moles, K. & Saunders, A. 2015. Ragged Places and Smooth Surfaces: Audio Walks as practices of making and doing the city.

Quench & Cotter, S. 2019. https://cardiffstudentmedia.co.uk/quench/music/gwdihw-closure/

Scherer, K.R. & Zentner, M.R. 2001. Emotional Effects Of Music: Production Rules.IN Music and Emotion.

Sloboda, J.A. And O’Neill, S.A. 2001. Emotions in Everyday Listening to Music. IN Music and Emotion.

Walter, B W 1999. The Arcades Project (Passagen-Werk). Cambridge Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Williamson, V. 2017. Music and Mind Wandering. Music Psychology.

0 notes

Photo

Hayduke Intermission: In the interest of allowing water levels in Grand Canyon National Park to drop (there are multiple creek crossings without straightforward alternatives that the Hayduke navigates), I take a week off of the Hayduke Trail to raft Desolation and Gray Canyons on the Green River (in Utah). Highlights from the trip include: -Finally being photographed (the photo featured here) by @tommycoreyphoto - am I a thru-hiker now? I have a @kulacloth too if that helps tip the scale in my favor. -Two boats popping and immediately losing oar locks (due to janky cotter pins). Followed by our outfitter heroically dropping new oar locks and pins OUT OF AN AIRPLANE over our campsite. Legend. -Reuniting with nearly half of the members of my Grand Canyon rafting trip from the beginning of last year (the other half are dead to me). -Being a passenger on a river trip which has helped me to understand why I was so much more stressed than nearly everyone else on my Grand trip. -Enjoying a river trip during a month where the days are long and dry suits and/or huddling around a fire at night aren’t mandatory (that said, I'm doing another winter Grand trip). -Not being in charge of planning the entirety of the trip and instead just showing up last-minute and going along for the ride (the worst part of a river trip). -Having access to my vehicle which was driven out from California by @tommycoreyphoto. This means I have an easy means of returning to the Hayduke post-river and also an easy means of returning home post-Hayduke. It was nice to be able to chill for a bit on the river and I’m hoping that my time off will prove more beneficial than detrimental to my hike. I’m not big on taking time off in the middle of a thing like this but this ended up being too good an opportunity to pass up. Hopefully, I can link back up with the Hayduke Bubble (most of who also took time off) between now and the supposedly-maybe-hopefully-not-sketchy creek crossings to come. Back to Jacob Lake I go and into the Grandest of Canyons I now must descend to meet my fate. #greenriver #desolationgray 📸 @tommycoreyphoto

0 notes

Text

Judith told Gerard she realized she'd actually rather not be in a relationship, so she's back to being "Single and Lovin' It" after all. He's still one of her closest friends, though.

#the sims#ts4#sims screenshots#sims gameplay#s4 screenshots#ts4 screenshots#Patterson save#Patterson gen 2#Judith Kibo#Gerard Cotter#judith make up your mind lmao#no spoilers but since I'm playing them in the 'future' I *know things* and... this might not be the end#I still ship it :P#image desc in alt text#ts4 gameplay

1 note

·

View note

Text

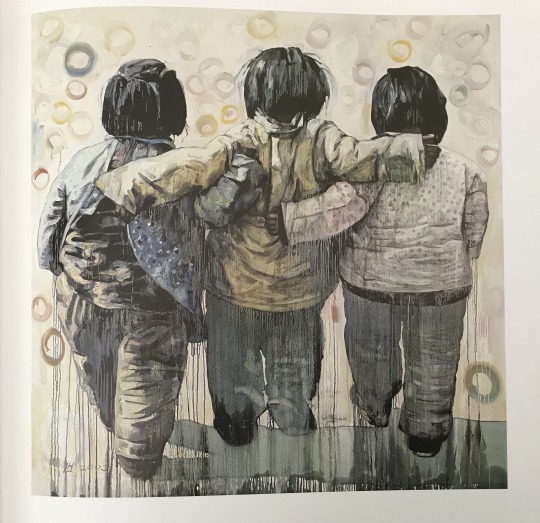

In memory of Hung Liu who passed away last August and in honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

Hung Liu was a Chinese American artist who once said her goal was “to invent a way of allowing myself to practice as a Chinese artist outside of a Chinese culture.”

Liu was born in 1948 during the revolutionary era in Changchun in northeast China,. Her father was a teacher imprisoned for his involvement in anti-Communist politics. During the Cultural Revolution, she was sent by the government to the countryside to work on farms for “re-education.”

In the 1970s, Liu studied at Beijing Teachers College and Central Academy of Fine Arts, and earned a graduate degree in 1981. But she grew restless with the officially-sanctioned Socialist Realist style and subjects. In 1984, she was given a permission to travel to the United States and enrolled in the MFA program at the University of California, San Diego.

Liu settled permanently in the Bay Area. She started teaching at Mills College in Oakland in 1990, eventually retiring in 2014.

Her death in August 2021 came less than three weeks before the scheduled opening of a career survey, “Hung Liu: Portraits of Promised Lands,” at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. She was the first Asian American woman to have a solo exhibition there.

Her work incorporated photo-based images that combined the political and the personal. Many of these images were of figures forgotten by history such as laborers, immigrants, prisoners, and prostitutes. (From “Hung Liu, Artist Who Blended East and West, Is Dead at 73” by Holland Cotter, The New York Times, August 22, 2021)

Image: “Sister Hoods”, 2003, Oil on canvas, 72”x 72” Summoning ghosts : the art of Hung Liu Oakland Museum of California. Liu, Hung, 1948-2021 招魂 Berkeley : University Of California Press, 2013. 216 p. : ill. ; 28 cm. English 2013. HOLLIS number: 990136645170203941

#HungLiu#ChineseAmericanartist#ChineseAmericanWomenartist#womenartist#asianamericanartist#asianamericanwomenartist#painter#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary#harvardfineartslibrary#fineartslibrary#harvard#harvard library#harvardfineartslib#harvardlibrary#painting#aapi#aapiheritagemonth#aapi heritage month#aapi artist#asian american

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jane Kaufman was making minimalist paintings in the early 1970s, spraying automobile paint on huge canvases. To be sure, the paint was sparkly, so the canvases shimmered �� “lyrical abstraction” was how one reviewer described her art and that of others doing similar work — but they were firmly of their reductive minimalist moment. Hilton Kramer of The New York Times approved, giving Ms. Kaufman a nod as a “new abstractionist” in his mostly dismissive review of the Whitney Biennial in 1973.

Then Ms. Kaufman made a sharp turn.

She began stitching and gluing her work, using decorative materials like bugle beads, metallic thread and feathers, and employing the embroidery and sewing skills she had been taught by her Russian grandmother. By the end of the decade, she was making first luminescent screens and wall hangings, then intricate quilts based on traditional American patterns.

In celebrating the so-called women’s work of sewing and crafting, she was performing a radical act, thumbing her nose at the dominant art movement of the era.

Ms. Kaufman died on June 2 at her home in Andes, N.Y. She was 83. Her death was confirmed by Abby Robinson, a friend.

Ms. Kaufman was not alone in her focus on the decorative. Artists like Joyce Kozloff and Miriam Schapiro were inspired, as she was, by patterns and motifs found in North African mosaics, Persian textiles and Japanese kimonos, as well as by homegrown domestic crafts like quilting and embroidery. It was feminist art, though not all its practitioners were women. (One of the more prominent ones, Tony Robbin, is a man.)

The movement came to be known as Pattern and Decoration. Ms. Kaufman curated its first group show in 1976, at the Alessandra Gallery on Broome Street in Lower Manhattan, and called it “Ten Approaches to the Decorative” (there were 10 artists). For the exhibition, she contributed small paintings she hung in pairs, densely striped with sparkly bugle beads.

“The paintings are small because they are not walls, they are for walls,” Ms. Kaufman wrote in her artist’s statement.

Other galleries, like Holly Solomon in New York, began showing the Pattern and Decoration artists’ work, and it also took off in Europe before falling out of favor in the mid-1980s. Decades later, curators would scoop up artists like Ms. Kaufman in a series of retrospectives, starting in 2008 at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, N.Y.

“It’s funky, funny, fussy, perverse, obsessive, riotous, accumulative, awkward, hypnotic,” Holland Cotter wrote in his review of that show in The Times. The Pattern and Decoration movement, he wrote, was the last genuine art movement of the 20th century, with “weight enough to bring down the great Western Minimalist wall for a while and bring the rest of the world in.”

Ms. Kaufman was born on May 26, 1938, in New York City. Her father, Herbert Kaufman, was an advertising executive with his own firm; her mother, Roslyn, was a homemaker. She earned a B.S. in art education from New York University in 1960 and an M.F.A. from Hunter College. She taught at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., in 1972, one its first female professors. “She was famous for telling her female students, ‘You are all brilliant and you are all going to end up at the Met,’” said the arts writer Elizabeth Hess, a Bard graduate.

From 1983 to 1991, Ms. Kaufman was an adjunct instructor at the Cooper Union in New York. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian Institution. She was a Guggenheim fellow in 1974 and in 1989 received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her “Crystal Hanging,” a glittering sculpture that looks like a meteor shower, is in the Thomas P. O’Neill Federal Building in Boston.

In 1966 she married Doug Ohlson, an abstract painter. The marriage ended in divorce in the early 1970s.

No immediate family members survive.

While Ms. Kaufman was extremely serious about her work, she was also a prankster dedicated to political activism; for decades, a pink penis poster she created was featured at marches for abortion rights and other women’s issues. Its last outing was at the Women’s March in New York City in January 2017.

She was a member of the Guerrilla Girls, the art-world agitators, all women, who protested the dearth of female and minority artists in galleries and museums by papering Manhattan buildings in the dead of night with impish posters like “The Guerrilla Girls’ Code of Ethics for Art Museums,” which proclaimed, “Thou shalt provide lavish funerals for Women and Artists of Color who thou planeth to exhibit only after their Death” and “Thou shalt keep Curatorial Salaries so low that Curators must be Independently Wealthy, or willing to engage in Insider Trading.”

Membership was by invitation only, and most members’ names were a secret (they wore gorilla masks in public). Many Guerrilla Girls used the names of dead female artists, like Käthe Kollwitz and Frida Kahlo. But Ms. Kaufman did not.

“Jane had a wicked sense of humor, the ability to get right to the center of an issue and the courage and principles to confront the powers that be,” the Guerrilla Girl who calls herself Frida Kahlo said in a statement. “We will never forget her. We hope that Jane is also remembered as a wonderful artist who tirelessly worked to break down the conventions of ‘craft vs fine art’ and later combined her meticulous handwork with biting political content.”

Ms. Kaufman’s later work, Ms. Hess said, was as political as her decorative work had been, and dealt with religious and social divisions. But she was unable to find a gallery that would show it. An embroidered piece from 2010 announced, in metallic thread on cutwork velvet, “Abstinence Makes the Church Grow Fondlers.”

“She was an artist who floated under the radar,” Ms. Hess said. “She was underacknowledged, though she had curated the first Pattern and Decoration show. Her work came out of her interest in women’s labor, but I think the real revelation to me about Jane’s work was its sumptuousness and beauty.”

In late 2019, a retrospective called “With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972 to 1985” opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (it is now at Bard through Nov. 28). Anna Katz, the show’s curator, chose a multicolored velvet quilt by Ms. Kaufman for the exhibition. Inspired by traditional crazy-quilt patterns, Ms. Kaufman had used over 100 traditional stitches, some dating back to the 16th century, in the piece, which she finished in 1985.

#Rest in Power Jane Kaufman#Women in the art world#Textiles and art#Pattern and Decoration#Guerrilla Girls

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

In light of the cotter situation, two game suspension is reasonable. I don’t care how much you like your fave, this is a high pace and high contact sport where many dangerous injuries can happen.

He could’ve seriously hurt this dude. He deserved the suspension.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

F.8.3 What other forms did state intervention in creating capitalism take?

Beyond being a paymaster for new forms of production and social relations as well as defending the owners’ power, the state intervened economically in other ways as well. As we noted in section B.2.5, the state played a key role in transforming the law codes of society in a capitalistic fashion, ignoring custom and common law when it was convenient to do so. Similarly, the use of tariffs and the granting of monopolies to companies played an important role in accumulating capital at the expense of working people, as did the breaking of unions and strikes by force.

However, one of the most blatant of these acts was the enclosure of common land. In Britain, by means of the Enclosure Acts, land that had been freely used by poor peasants was claimed by large landlords as private property. As socialist historian E.P. Thompson summarised, “the social violence of enclosure consisted … in the drastic, total imposition upon the village of capitalist property-definitions.” [The Making of the English Working Class, pp. 237–8] Property rights, which favoured the rich, replaced the use rights and free agreement that had governed peasants use of the commons. Unlike use rights, which rest in the individual, property rights require state intervention to create and maintain. “Parliament and law imposed capitalist definitions to exclusive property in land,” Thompson notes. This process involved ignoring the wishes of those who used the commons and repressing those who objected. Parliament was, of course, run by and for the rich who then simply “observed the rules which they themselves had made.” [Customs in Common, p. 163]

Unsurprisingly, many landowners would become rich through the enclosure of the commons, heaths and downland while many ordinary people had a centuries old right taken away. Land enclosure was a gigantic swindle on the part of large landowners. In the words of one English folk poem written in 1764 as a protest against enclosure:

They hang the man, and flog the woman, That steals the goose from off the common; But let the greater villain loose, That steals the common from the goose.

It should be remembered that the process of enclosure was not limited to just the period of the industrial revolution. As Colin Ward notes, “in Tudor times, a wave of enclosures by land-owners who sought to profit from the high price of wool had deprived the commoners of their livelihood and obliged them to seek work elsewhere or become vagrants or squatters on the wastes on the edges of villages.” [Cotters and Squatters, p. 30] This first wave increased the size of the rural proletariat who sold their labour to landlords. Nor should we forget that this imposition of capitalist property rights did not imply that it was illegal. As Michael Perelman notes, "[f]ormally, this dispossession was perfectly legal. After all, the peasants did not have property rights in the narrow sense. They only had traditional rights. As markets evolved, first land-hungry gentry and later the bourgeoisie used the state to create a legal structure to abrogate these traditional rights.” [The Invention of Capitalism, pp. 13–4]

While technically legal as the landlords made the law, the impact of this stealing of the land should not be under estimated. Without land, you cannot live and have to sell your liberty to others. This places those with capital at an advantage, which will tend to increase, rather than decrease, the inequalities in society (and so place the landless workers at an increasing disadvantage over time). This process can be seen from early stages of capitalism. With the enclosure of the land an agricultural workforce was created which had to travel where the work was. This influx of landless ex-peasants into the towns ensured that the traditional guild system crumbled and was transformed into capitalistic industry with bosses and wage slaves rather than master craftsmen and their journeymen. Hence the enclosure of land played a key role, for “it is clear that economic inequalities are unlikely to create a division of society into an employing master class and a subject wage-earning class, unless access to the means of production, including land, is by some means or another barred to a substantial section of the community.” [Maurice Dobb, Studies in Capitalist Development, p. 253]

The importance of access to land is summarised by this limerick by the followers of Henry George (a 19th century writer who argued for a “single tax” and the nationalisation of land). The Georgites got their basic argument on the importance of land down these few, excellent, lines:

A college economist planned To live without access to land He would have succeeded But found that he needed Food, shelter and somewhere to stand.

Thus anarchists concern over the “land monopoly” of which the Enclosure Acts were but one part. The land monopoly, to use Tucker’s words, “consists in the enforcement by government of land titles which do not rest upon personal occupancy and cultivation.” [The Anarchist Reader, p. 150] So it should be remembered that common land did not include the large holdings of members of the feudal aristocracy and other landlords. This helped to artificially limit available land and produce a rural proletariat just as much as enclosures.

It is important to remember that wage labour first developed on the land and it was the protection of land titles of landlords and nobility, combined with enclosure, that meant people could not just work their own land. The pressing economic circumstances created by enclosing the land and enforcing property rights to large estates ensured that capitalists did not have to point a gun at people’s heads to get them to work long hours in authoritarian, dehumanising conditions. In such circumstances, when the majority are dispossessed and face the threat of starvation, poverty, homelessness and so on, “initiation of force” is not required. But guns were required to enforce the system of private property that created the labour market in the first place, to enclosure common land and protect the estates of the nobility and wealthy.

By decreasing the availability of land for rural people, the enclosures destroyed working-class independence. Through these Acts, innumerable peasants were excluded from access to their former means of livelihood, forcing them to seek work from landlords or to migrate to the cities to seek work in the newly emerging factories of the budding industrial capitalists who were thus provided with a ready source of cheap labour. The capitalists, of course, did not describe the results this way, but attempted to obfuscate the issue with their usual rhetoric about civilisation and progress. Thus John Bellers, a 17th-century supporter of enclosures, claimed that commons were “a hindrance to Industry, and … Nurseries of Idleness and Insolence.” The “forests and great Commons make the Poor that are upon them too much like the indians.” [quoted by Thompson, Op. Cit., p. 165] Elsewhere Thompson argues that the commons “were now seen as a dangerous centre of indiscipline … Ideology was added to self-interest. It became a matter of public-spirited policy for gentlemen to remove cottagers from the commons, reduce his labourers to dependence.” [The Making of the English Working Class, pp. 242–3] David McNally confirms this, arguing “it was precisely these elements of material and spiritual independence that many of the most outspoken advocates of enclosure sought to destroy.” Eighteenth-century proponents of enclosure “were remarkably forthright in this respect. Common rights and access to common lands, they argued, allowed a degree of social and economic independence, and thereby produced a lazy, dissolute mass of rural poor who eschewed honest labour and church attendance … Denying such people common lands and common rights would force them to conform to the harsh discipline imposed by the market in labour.” [Against the Market, p. 19]

The commons gave working-class people a degree of independence which allowed them to be “insolent” to their betters. This had to be stopped, as it undermined to the very roots of authority relationships within society. The commons increased freedom for ordinary people and made them less willing to follow orders and accept wage labour. The reference to “Indians” is important, as the independence and freedom of Native Americans is well documented. The common feature of both cultures was communal ownership of the means of production and free access to it (usufruct). This is discussed further in section I.7 (Won’t Libertarian Socialism destroy individuality?). As Bookchin stressed, the factory “was not born from a need to integrate labour with modern machinery,” rather it was to regulate labour and make it regular. For the “irregularity, or ‘naturalness,’ in the rhythm and intensity of traditional systems of work contributed more towards the bourgeoisie’s craze for social control and its savagely anti-naturalistic outlook than did the prices or earnings demanded by its employees. More than any single technical factor, this irregularity led to the rationalisation of labour under a single ensemble of rule, to a discipline of work and regulation of time that yielded the modern factory … the initial goal of the factory was to dominate labour and destroy the worker’s independence from capital.” [The Ecology of Freedom p. 406]

Hence the pressing need to break the workers’ ties with the land and so the “loss of this independence included the loss of the worker’s contact with food cultivation … To live in a cottage … often meant to cultivate a family garden, possibly to pasture a cow, to prepare one’s own bread, and to have the skills for keeping a home in good repair. To utterly erase these skills and means of a livelihood from the worker’s life became an industrial imperative.” Thus the worker’s “complete dependence on the factory and on an industrial labour market was a compelling precondition for the triumph of industrial society … The need to destroy whatever independent means of life the worker could garner … all involved the issue of reducing the proletariat to a condition of total powerlessness in the face of capital. And with that powerlessness came a supineness, a loss of character and community, and a decline in moral fibre.” [Bookchin, Op. Cit.,, pp. 406–7] Unsurprisingly, there was a positive association between enclosure and migration out of villages and a “definite correlation … between the extent of enclosure and reliance on poor rates … parliamentary enclosure resulted in out-migration and a higher level of pauperisation.” Moreover, “the standard of living was generally much higher in those areas where labourer managed to combine industrial work with farming … Access to commons meant that labourers could graze animals, gather wood, stones and gravel, dig coal, hunt and fish. These rights often made the difference between subsistence and abject poverty.” [David McNally, Op. Cit., p. 14 and p. 18] Game laws also ensured that the peasantry and servants could not legally hunt for food as from the time of Richard II (1389) to 1831, no person could kill game unless qualified by estate or social standing.

The enclosure of the commons (in whatever form it took — see section F.8.5 for the US equivalent) solved both problems — the high cost of labour, and the freedom and dignity of the worker. The enclosures perfectly illustrate the principle that capitalism requires a state to ensure that the majority of people do not have free access to any means of livelihood and so must sell themselves to capitalists in order to survive. There is no doubt that if the state had “left alone” the European peasantry, allowing them to continue their collective farming practices (“collective farming” because, as Kropotkin shows, the peasants not only shared the land but much of the farm labour as well), capitalism could not have taken hold (see Mutual Aid for more on the European enclosures [pp. 184–189]). As Kropotkin notes, ”[i]nstances of commoners themselves dividing their lands were rare, everywhere the State coerced them to enforce the division, or simply favoured the private appropriation of their lands” by the nobles and wealthy. Thus “to speak of the natural death of the village community [or the commons] in virtue of economical law is as grim a joke as to speak of the natural death of soldiers slaughtered on a battlefield.” [Mutual Aid, p. 188 and p. 189]

Once a labour market was created by means of enclosure and the land monopoly, the state did not passively let it work. When market conditions favoured the working class, the state took heed of the calls of landlords and capitalists and intervened to restore the “natural” order. The state actively used the law to lower wages and ban unions of workers for centuries. In Britain, for example, after the Black Death there was a “servant” shortage. Rather than allow the market to work its magic, the landlords turned to the state and the result was “the Statute of Labourers” of 1351:

“Whereas late against the malice of servants, which were idle, and not willing to serve after the pestilence, without taking excessive wages, it was ordained by our lord the king … that such manner of servants … should be bound to serve, receiving salary and wages, accustomed in places where they ought to serve in the twentieth year of the reign of the king that now is, or five or six years before; and that the same servants refusing to serve in such manner should be punished by imprisonment of their bodies … now forasmuch as it is given the king to understand in this present parliament, by the petition of the commonalty, that the said servants having no regard to the said ordinance, .. to the great damage of the great men, and impoverishing of all the said commonalty, whereof the said commonalty prayeth remedy: wherefore in the said parliament, by the assent of the said prelates, earls, barons, and other great men, and of the same commonalty there assembled, to refrain the malice of the said servants, be ordained and established the things underwritten.”

Thus state action was required because labourers had increased bargaining power and commanded higher wages which, in turn, led to inflation throughout the economy. In other words, an early version of the NAIRU (see section C.9). In one form or another this statute remained in force right through to the 19th century (later versions made it illegal for employees to “conspire” to fix wages, i.e., to organise to demand wage increases). Such measures were particularly sought when the labour market occasionally favoured the working class. For example, ”[a]fter the Restoration [of the English Monarchy],” noted Dobb, “when labour-scarcity had again become a serious complaint and the propertied class had been soundly frightened by the insubordination of the Commonwealth years, the clamour for legislative interference to keep wages low, to drive the poor into employment and to extend the system of workhouses and ‘houses of correction’ and the farming out of paupers once more reached a crescendo.” The same occurred on Continental Europe. [Op. Cit., p. 234]

So, time and again employers called on the state to provide force to suppress the working class, artificially lower wages and bolster their economic power and authority. While such legislation was often difficult to enforce and often ineffectual in that real wages did, over time, increase, the threat and use of state coercion would ensure that they did not increase as fast as they may otherwise have done. Similarly, the use of courts and troops to break unions and strikes helped the process of capital accumulation immensely. Then there were the various laws used to control the free movement of workers. “For centuries,” notes Colin Ward, “the lives of the poor majority in rural England were dominated by the Poor law and its ramifications, like the Settlement Act of 1697 which debarred strangers from entering a parish unless they had a Settlement Certificate in which their home parish agreed to take them back if they became in need of poor relief. Like the Workhouse, it was a hated institution that lasted into the 20th century.” [Op. Cit., p. 31]

As Kropotkin stressed, “it was the State which undertook to settle .. . griefs” between workers and bosses “so as to guarantee a ‘convenient’ livelihood” (convenient for the masters, of course). It also acted “severely to prohibit all combinations … under the menace of severe punishments … Both in the town and in the village the State reigned over loose aggregations of individuals, and was ready to prevent by the most stringent measures the reconstitution of any sort of separate unions among them.” Workers who formed unions “were prosecuted wholesale under the Master and Servant Act — workers being summarily arrested and condemned upon a mere complaint of misbehaviour lodged by the master. Strikes were suppressed in an autocratic way … to say nothing of the military suppression of strike riots … To practice mutual support under such circumstances was anything but an easy task … After a long fight, which lasted over a hundred years, the right of combing together was conquered.” [Mutual Aid, p. 210 and p. 211] It took until 1813 until the laws regulating wages were repealed while the laws against combinations remained until 1825 (although that did not stop the Tolpuddle Martyrs being convicted of “administering an illegal oath” and deported to Tasmania in 1834). Fifty years later, the provisions of the statues of labourers which made it a civil action if the boss broke his contract but a criminal action if the worker broke it were repealed. Trade unions were given legal recognition in 1871 while, at the same time, another law limited what the workers could do in a strike or lockout. The British ideals of free trade never included freedom to organise.

(Luckily, by then, economists were at hand to explain to the workers that organising to demand higher wages was against their own self-interest. By a strange coincidence, all those laws against unions had actually helped the working class by enforcing the necessary conditions for perfect competition in labour market! What are the chances of that? Of course, while considered undesirable from the perspective of mainstream economists — and, by strange co-incidence, the bosses — unions are generally not banned these days but rather heavily regulated. The freedom loving, deregulating Thatcherites passed six Employment Acts between 1980 and 1993 restricting industrial action by requiring pre-strike ballots, outlawing secondary action, restricting picketing and giving employers the right to seek injunctions where there is doubt about the legality of action — in the workers’ interest, of course as, for some reason, politicians, bosses and economists have always known what best for trade unionists rather than the trade unionists themselves. And if they objected, well, that was what the state was for.)

So to anyone remotely familiar with working class history the notion that there could be an economic theory which ignores power relations between bosses and workers is a particularly self-serving joke. Economic relations always have a power element, even if only to protect the property and power of the wealthy — the Invisible Hand always counts on a very visible Iron Fist when required. As Kropotkin memorably put it, the rise of capitalism has always seen the State “tighten the screw for the worker” and “impos[ing] industrial serfdom.” So what the bourgeoisie “swept away as harmful to industry” was anything considered as “useless and harmful” but that class “was at pains not to sweep away was the power of the State over industry, over the factory serf.” Nor should the role of public schooling be overlooked, within which “the spirit of voluntary servitude was always cleverly cultivated in the minds of the young, and still is, in order to perpetuate the subjection of the individual to the State.” [The State: Its Historic Role, pp. 52–3 and p. 55] Such education also ensured that children become used to the obedience and boredom required for wage slavery.

Like the more recent case of fascist Chile, “free market” capitalism was imposed on the majority of society by an elite using the authoritarian state. This was recognised by Adam Smith when he opposed state intervention in The Wealth of Nations. In Smith’s day, the government was openly and unashamedly an instrument of wealth owners. Less than 10 per cent of British men (and no women) had the right to vote. When Smith opposed state interference, he was opposing the imposition of wealth owners’ interests on everybody else (and, of course, how “liberal”, never mind “libertarian”, is a political system in which the many follow the rules and laws set-down in the so-called interests of all by the few? As history shows, any minority given, or who take, such power will abuse it in their own interests). Today, the situation is reversed, with neo-liberals and right-“libertarians” opposing state interference in the economy (e.g. regulation of Big Business) so as to prevent the public from having even a minor impact on the power or interests of the elite. The fact that “free market” capitalism always requires introduction by an authoritarian state should make all honest “Libertarians” ask: How “free” is the “free market”?

#faq#anarchy faq#revolution#anarchism#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#climate change#climate crisis#climate#ecology#anarchy works#environmentalism#environment#solarpunk#anti colonialism#mutual aid#cops#police

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Found in the Archives! This rare Yiddish book “Negro Poetry in America” was published in 1936 in Moscow, is from our International Workers Order/ Jewish People’s Fraternal Order collection and contains works of Harlem Renaissance writers including Langston Hughes’ poems, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, Dream Variations, Good Morning Revolution, and Song for a Dark Girl. The IWO commissioned one of Langston Hughes most famous works, his anthem “Let America Be America Again.” This work has been continually performed and is very much part of a contemporary repertoire. Only one of 7 known copies, this edition includes a handwritten dedication by the translator to Itche Goldberg, head of the JPFO's Educational department. Other writers in the volume include Langston Hughes, Thomas T. Fletcher, Joseph S. Cotter, Countee Cullen, Anita Scott Coleman, Richard Wright, Claude McCay, and many more. Thanks to Cornell Jewish Studies Professor Elissa Sampson for this rare and amazing find. * * * #CornellRAD #InternationalWorkersOrder #LangstonHughes @rarecornell @cornell_library @cornellpublichistory @cujewishstudies @cornellilr https://www.instagram.com/p/CbNdjRGrgJP/?utm_medium=tumblr

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cats of Ulthar

The Cats of Ulthar is a short story by H. P. Lovecraft.

This story is about how the town of Ulthar settled on the choice to prohibit anybody from murdering felines. The storyteller reviews that in the time under the steady gaze of the law was passed, there was an old cotter and his significant other who caught and killed their neighbors' felines. The locals, too unfortunate to even think about facing the old couple, chosen to simply keep their felines inside and in the clear.

At that point, a parade of bizarre explorers showed up one day to Ulthar. They were wearing unusual garments and performed unfamiliar petitions that the townspeople couldn't comprehend. Going with the drifters was a little vagrant kid named Menes and his pet cat. Visit hp lovecraft cat name

On the third day of the convoy's visit, Menes couldn't discover his cat. He looked through the entire town and ultimately surrendered and began crying. The townspeople realized what had happened to Menes' feline, and had compassion for him and advised him of the cotter and his significant other's feline executing binge. After becoming aware of the old couple's vicious demonstrations towards felines, Menes quit crying and summoned a petition that made the mists in the sky change shape and obscure with an obscure power.

The band left that evening, gone forever, and the residents got back to their homes to find that the entirety of the felines had vanished from the whole town. The townspeople accepted that the procession had reviled them and taken their felines in an attack of vengeance, however by morning every one of the felines were back in the homes. Strangely, every feline was truly fat, and they all would not eat their nourishment for quite a long time. After seven days, a couple of townspeople had seen that the old cotter and his better half had not been seen by any stretch of the imagination, and that their home's lights were rarely lit. A couple of individuals got sufficient mental fortitude to stand up to them and visited the old couple's home, poor down the entryway, and headed inside. All they discovered were a couple of skeletons on the ground, totally spotless, substance chewed off the bone...

Thus, another law was passed: "In Ulthar, no man may execute a feline."

That law is referenced in passing in Lovecraft's other Dreamworld stories. When Randolph Carter gets to Ulthar on his Dream-journey, the roads are loaded with glad, very really liked kitties.

10 notes

·

View notes