Text

Alien: Romulus

I had very high hopes for what Fede Alvarez could do with the psychosexual terror at the heart of Alien. Instead, we get a collection of fan service (oh, here’s the famous shot of Ripley and the Xenomorph from Alien 3, and here’s “Get away from her, you bitch” except it’s said by a Black actor this time, also here’s an AI actor atrocity wearing the face of an actor from Alien, and could we interest you in a couple of references to Prometheus) and absolute nonsense at the climax. David Jonsson makes the most of his role, and he’s the only actor with a character who gets an actual arc.

I really thought that showing how the Company grinds down the young had a lot of potential, and that would make the YA feel of the movie work. Instead, we fall into the YA trap of characters who can be distilled into one-word descriptions (pregnant, bland, Asian, cousin).

One of the most disappointing movie experiences of the year.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Earth

It’s ballsy of Ben Wheatley to make a movie in 2021 during quarantine. It’s even gutsier to open with vague references to a pandemic and all the visual markers of the COVID-19 quarantine without slamming the relevance home (but with tasteful plausible deniability) like Songbird. Using the time to make a folk horror movie that tests the boundaries of viewer photosensitivity is in itself, a bold move.

And to Wheatley’s credit, there is one really good scene built around two men, a woman, an axe, and some toes. But the rest of it - the walking through the woods, the philosophizing about communicating with nature through science vs. with the spirit of nature with art, the ecological theorizing - is bunk.

#in the earth#ben wheatley#reece shearsmith#joel fry#ellora torchia#hayley squires#folk horror#horror#films#movies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuckoo

Well, I saw this week a stylish horror movie starring Maika Monroe, who broke out in The Guest, so I had to round out the week with Dan Stevens, her costar who also broke out with that film.

Where I felt that Longlegs had a really hard time escalating its tension after creating a very creepy atmosphere, I found Cuckoo skillfully ratcheting the tension from setpiece to setpiece until its really entertaining conclusion.

Hunter Schafer has drawn comparisons to Monroe since they’re both blonde, tall scream queens who bring a lanky, athletic physicality to their roles. She conveys Gretchen’s teenage sullenness and vulnerability, and she makes Gretchen’s switch flip to appreciate and protect her sister mostly make emotional sense. I’ve seen her now in a vignette in Kinds of Kindness and this film, and I’ve been impressed both times.

Dan Stevens is as weird and charismatic as ever. His conventional handsomeness helps him hide his character’s sinister oddness really well, and he commits to the performance.

The plot and the nature of the monster don’t make a ton of sense if you dig any further. I suppose that I didn’t care to dig since I was satisfied with how the film laid out its scares so well at the start and connected the dots for Gretchen’s story. If some pieces (like what was the deal with Gretchen’s father and stepmother) got lost, it’s fine.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Longlegs

Can a thriller be scary if it doesn't even try to hide its cards? Can you justify the obvious twist through conjectural justification that the obviousness is the point to building the dread of the inevitable? Is that just giving a movie that fumbles how it handles the third act revelation too much credit?

I went in wanting to like the film first off of the strength of the marketing and second off of my affection for Maika Monroe. Monroe plays FBI special agent Lee Harker with a twitchy distance that reads as neurodivergence. She gives Harker a presence, and her lankiness makes sense with Harker's personality. Unfortunately, Monroe isn't given much to show Harker's interiority. The film is structured for comparison with The Silence of the Lambs and thus Monroe's Harker with Jodie Foster's Clarice Starling, and though we see more of Harker's past, we get less insight into how Harker navigates the world around her. Harker's relationship with her job and her superior, Agent Carter, never rises beyond perfunctory.

There is a lot of effective, creepy mood-establishing camerawork from director Osgood Perkins and cinematographer Andres Arochi, and the costuming and set design have a lot of retro tactile charm. There is a purulent yellow filter over the film, and even the Satanic panic that the film takes absolutely serious resonates with the moral panic I remember over Magic: The Gathering's very existence and cards like Demonic Tutor and Unholy Strength. Kiernan Shipka returns to collaborate with Perkins again after The Blackcoat's Daughter and gives an unsettling performance.

There is also the Nicholas Cage-shaped elephant in the room. I found his character more silly than scary, though Cage devotes himself fully to the performance. It feels like he's channeling his audition for Jeremiah Sands from Mandy in his performance here.

Returning to the earlier question, I don't think Perkins intends to use the lack of mystery as a way of generating the dread of the inevitable. Perkins's script positions the revelation as a significant event for Harker and the film, and the way the revelation is told to us feels like we are supposed to be taken off guard by it. Instead, due to the economy of characters, there isn't much doubt about who the murderous accomplice is.

That said, the obviousness plays into the straightforward way that the film treats Satan's power as a force in the world. We are not invited to doubt that a demonic power is causing the family annihilators to murder their families throughout Oregon. There is something refreshing about that, but that's just not enough.

#longlegs 2024#longlegs movie#osgood perkins#maika monroe#nicholas cage#oz perkins#movies#films#horror

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinds of Kindness

Kinds of Kindness (2024, dir. Yorgos Lanthimos): After a couple of films geared more toward mainstream tastes (The Favourite, Poor Things), Lanthimos (and long-time screenwriting partner Efthimis Filippou) are back with one for the Lanthimos sickos. I thought it was one of the funniest movies I've seen all year, and I'm glad I wasn't the only one in the theater laughing. It has the Lanthimos trademark themes of control, degradation, sudden violence, askew English phrasing, and identity.

0 notes

Text

Suffs

Suffs (2024, The Music Box Theatre): I don’t know if the comparisons to Hamilton that have thrown around in reviews have done the show any favors. It’s an easy comparison to make:

-award-winning musicals that transitioned from off-Broadway to Broadway runs

-helmed by a singular vision

-inspired by a book that the creator read about a moment in American history

-where characters are played by actors who look and speak differently than their historical counterparts.

Obviously, these two works must be paired in conversation. And since the 1776 revival flopped on Broadway after trying some of the same casting tactics as Hamilton (casting all female, transgender, and non-binary actors as the American Founding Fathers), it fell on Suffs, at least to the public, critics, and producers, to prove that Hamilton wasn’t a singular event and that you could make a commercially and critically successful musical based on American history with ahistorical casting. (As I said, the comparison is superficial.) (Furthering the narrative, Phillipa Soo was original cast in Hamilton and in the off-Broadway cast in Suffs.)

Digging below the surface, one can see similar bones upholding Hamilton and Suffs inherited from ancestors like Les Miserables. The story is mostly focused on the brash Alice Paul/Alexander Hamilton, who is contrasted against her more conservative colleague, Carrie Chapman Catt/Aaron Burr. Paul is buoyed by her three friends: Doris Stevens, Inez Milholland, and Ruza Wenclawska/John Laurens, Hercules Mulligan, and the Marquis de Lafayette. Their uphill struggle to gain women the vote is opposed by the tyrannical President Woodrow Wilson/King George III, who has a signature solo in each act. Paul and her colleagues encourage each other to finish the fight/not throw away their shot, and the musical is as much an exhortation to the present and future as much as it is a walk through the past.

And yes, we thus have the setup for easy, smirking barbs about how the one credited to a man about a man’s story is one of the most successful, critically acclaimed musicals in history while the one credited to a woman about women just won two Tony Awards and won’t see any productions in other cities, much less other countries, any time soon.

Beyond that jab, however, is the follow-up uppercut that Hamilton is just a better musical than Suffs. Many actors are making their Broadway debut in Suffs, and you can feel the rawness in the simple choreography (likely affected by the period-appropriate costuming). The play launches jarringly with the ensemble number “Let Mother Vote;” there wasn’t even a reminder to the audience to silence their cell phones to prime the audience, and so of course a phone rang in the second act. The pace fails to give the audience a moment to cheer for the first Woodrow Wilson solo, “Ladies;” instead, the scene transitions right into “A Meeting With President Wilson.”

If we fall into the compare and contrast game, then one might hold Suffs wanting in its lack of songs that stick and work outside of its context; there are no displays of verbal gymnastics like “Satisfied” or “What’d I Miss.” I struggle to hum a melody from Suffs the morning after; I would say that it’s surprising that Suffs won the Tony Award for Best Original Score, but that is also dictated by the level of competition this year.

That’s not to say Suffs is a bad musical; the house was packed for the performance I attended, and I was moved by the story and songs. The American suffrage movement presents fewer moments of bombast compared to the American Revolution and the country’s founding; there’s no Battle of Yorktown to provide a first act closing number. Instead, we have a great and fiery number in the second act focused on the Silent Sentinels, who protest Wilson’s unwillingness to publicly support suffrage and decision to incarcerate Paul, Smith, Burns, and Wenclawska at Occoquan Workhouse.

The cast is strong across the board; standouts were Hannah Cruz, who embodies Inez Milholland’s magnetic personality; Jenn Colella, who gives needed nuance to Carrie Chapman Catt, Grace McLean, who delights in chauvinism and convenient ignorance; Emily Skinner, who lights up the stage as socialite Alva Belmont; and Lucy Bonino who lends a quiet strength and anchor to the show as Paul’s closest friend, Lucy Burns.

And then there is Nikki M. James, who is incredible as Ida B. Wells. Wells is the focal point of Suffs’ departure from comparisons with Hamilton, as how the show directly challenges how the suffrage movement justified compromises to placate southern members at the cost of Black activists seems to be in conversation with how Hamilton tried to make the slave-owning George Washington an abolitionist in “Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down)” by having him answer Laurens’s question:

Laurens: Black and white soldiers wonder alike if this really means freedom

Washington: Not. Yet.

Though Paul is Suffs’s protagonist, Suffs also shows how Paul’s story intersects with Wells’s. The play sides with Wells when she directly criticizes Paul and friends for asking Black activists to wait their turn on racial justice without resolving their hypocrisy. The suffragists who demand that the men who control their political and economic lives stop deferring to hear their call for suffrage because tariffs, war, and campaigning for re-election take priority then tell the Black activists that actually enforcing Black men’s suffrage and stopping lynchings must wait until women’s suffrage has been won. However, Suffs has a refrain on this as well: it’s important to remember who the actual enemy is and not to succumb to these divisions that only benefit conservative forces that want to preserve the status quo.

The play mostly handles these transitions in focus with deftness, and James is able to balance steely resolution, doubt, righteous indignation, sorrow at the future, and hope for the best in her limited time on stage. The play would be greatly diminished if James’ Wells, Anastacia McCleskey’s Mary Church Terrell, and Laila Erica Drew’s Phyllis Terrell had been excised so the focus could be solely on Paul’s story.

Similarly, the play reminds us of how little we know and see about the larger story of the suffrage movement and intersectional need for change by dropping a last moment revelation that Catt was queer and romantically involved with Molly Hay. It might seem like a random point to include in “If We Were Married (reprise),” but it reinforces the point that suffrage is just one direction of necessary change and that our focus on Paul limits what we know about the other activists’ motivations and struggles.

Given the high cost of Broadway tickets (our seats were in the theater’s penultimate upper tier row, and they were still more than $100), we have to be very selective in what we see. Recommendations from Helen Shaw of New York magazine haven’t steered us wrong yet, and we’re glad that we saw Suffs on her advice. If nothing else, it’s led me to teaching myself about the suffrage movement, since my formal schooling was woefully inadequate on this subject.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Quiet Place (2018) and Hereditary (2018)

Trailer for A Quiet Place

Trailer for Hereditary

When the world around you petrifies you with scenes of banal evil, it’s hard to say that a horror film will be the scariest thing that you’ll see this year. After all, what could Ari Aster, writer and director of Hereditary, or John Krasinski, writer (along with Bryan Woods and Scott Beck) and director of A Quiet Place, produce in their horror films about families that would be more shocking than footage of children, forcibly separated from their parents, locked in cages, wailing for their families or at least a friendly and familiar face?

It’s a common notion that art reflects its context, and that horror films provide a particular filter for a culture’s anxieties. What anxiety drives these two films from this wave of “art-horror”? Judging from A Quiet Place and Hereditary, the pressure is on the family unit, which is besieged from within and without. It’s just that Aster has a very different perspective on the family’s odds of making it than Woods, Beck, and Krasinski.

At its heart, the Abbotts in A Quiet Place are a functional unit even though they’re coping with what could be a crippling loss. Father and son go fishing to provide dinner; mother and daughter clean clothes and manage the Abbotts’ home. As Lee Abbott, the muscular Krasinski is a loving, attentive, and infinitely patient father, stoically bearing his teenage daughter’s scorn, probing the airwaves for other survivors, fiddling with hearing devices so the scornful Regan’s hearing can be restored, and dancing with Evelyn, his pregnant wife, played by Emily Blunt. The Abbotts bear the grief of losing their youngest son, Beau, to creatures that hunt by sound, attacking anything that’s louder than a breeze’s murmur. The creatures have devastated the world, leading to apocalyptic breakdowns in civil society. The Abbotts have weathered the violence and have carved out a sustainable life in this world. Things are stable enough that Evelyn can try to home school her son, that they can build systems and contingencies to account for the impending birth of Lee and Evelyn’s child. With a larger support base of four people, they’re more capable of surviving in this world than the crazed old man that Lee and his son, Marcus, meet in the forest. In a world where Lee cannot express himself openly above quietly mouthing words to his family, Lee tells Regan and Marcus in American Sign Language that he loves them before he yells at one of the aforementioned creatures to ensure Regan and Marcus’s to take care of their mother and new brother. His sacrifice and tinkering with hearing devices allows Marcus, Evelyn, and Regan to discover the secret to killing the creatures. The film ends with what viewers actually wanted to see all along: a character played by Emily Blunt cocking a shotgun, ready to blast away any threats to her family.

A unified and functional nuclear family, the Abbotts can do it all. They find the secret to destroying the threat, which no one was able to discover. They destroy one of the creatures, which even organized militaries with superior logistics and firepower couldn’t manage. The trauma within their family unit pales in comparison to the existential external threat, so it doesn’t have the chance to corrode their bonds. They not only survive in this world; they thrive so successfully that they are able to conceive the notion of replacing their dead son with a new baby and to countenance the idea of raising a screaming, crying baby in a world torn apart creatures that hunt sounds. They believe that they control their own fate, that every obstacle can be overcome, that their love for each other is enough to carry them through this crisis. All they’re looking for, if you will, is A Quiet Place.

From Looper to Edge of Tomorrow to A Quiet Place, sometimes you just need to see Emily Blunt brandish a gun.

[As with other horror films, Hereditary’s power comes from its ability to surprise. So, spoilers ahead for Hereditary.]

The Grahams in Hereditary (Toni Collette’s Annie, Gabriel Byrne’s Steve, Alex Wolff’s Peter, and Milly Shapiro’s Charlie) have a quiet, suburban home, but they lack the luck that the Abbotts have. Where the Abbotts are unified, the Grahams are quietly disintegrating, unacknowledged grievances eroding their ability to communicate with, much less trust in, each other. Aster at first encourages us to accept that the corrosive agent is a history of mental illness in Annie’s family: Annie tells us by telling her grief support group that her father starved himself to death; her brother had schizophrenia committed suicide; her mother had dissociative identity disorder and developed dementia in her twilight years. Later, Aster shows Steve drafting an email to a psychiatric institute to express his concern that Annie, possibly not for the first time, is having a mental health crisis. The film’s marketing works hard to lead us to think that the film will be Annie’s descent into madness as her sanity slips thanks to stress and a genetic predisposition toward mental disorders. Instead, the threat that the Grahams inherited is much older, and unlike the Abbotts, there is no last-minute discovery of a secret that will allow them to blow the threat wide apart.

In her eulogy for Ellen, Annie described her as a secretive woman who had “private rituals” and “private friends.” Annie did not learn effective communication skills from her uncommunicative mother. Instead, Annie lies to her husband about going to grief support groups, telling him instead that she went to see movies. She channels her grief and pain into carving miniatures that depict painful moments of her life, like her mother baring her breast and trying to breastfeed Charlie in Annie’s stead, her mother slowly dying in hospice care, or the accident that decapitated Charlie and traumatized her son. She is unable to call the gallery that is expecting to show her miniatures to ask for more time; when they call her and offer an extension, she smashes the miniatures in barely suppressed and unexpressed anger and frustration. She reveals to Joan, a woman she befriends at the grief support group, that she almost burned Charlie, Peter, and herself alive one night while she sleepwalked. She describes to Joan how she and Peter settled into a cycle of blame and argument after that incident, but there are no hints that they ever sought counseling to resolve this through communication. After Charlie’s death, she rants during dinner, in a tour de force performance by Collette, that she cannot communicate with Peter because he will not acknowledge his responsibility in Charlie’s death. Unable to sleep after Charlie’s death, she lies to Steve that she’ll return to their bed. When he later freaks out because she has sleepwalked into his room, she downplays it and never acknowledges to Peter that might is rightfully upset given the last incident when she sleepwalked to him. The idea that the family should enter counseling after Charlie’s death is never considered; given that she learned to be a private and uncommunicative woman from her mother, Annie would probably reject the idea. Whereas the Abbotts could not talk for fear of their lives, the Grahams could not talk to save their lives.

Obviously, there is a difference between what you inherit and what you learn, but the bigger idea is the past’s effect on the future. While the Grahams could have overcome her lack of communication skills, they could not have overcome the demonic conspiracy that Ellen and her private friends had set in motion years ago. Aster plays his thematic hand early; in a classroom, Peter’s classmates and teacher discuss the tragedy of Iphigenia, whom Agamemnon sacrificed to gods in exchange for strong winds on the Mycenean fleet’s journey to Troy. They debate whether it is more tragic if a character causes their own downfall due to a fatal flaw or if it’s worse if their downfall was fated all along, the character stripped of their control of their possibilities. The film then allows the viewer to forget this discussion until it is grounded in the revelations about how Ellen and her circle pledged themselves to the demon Paimon.

The Grahams’ downfall is not due to the mental illness that Annie inherited from her family. Instead, the Grahams never had control at all; Ellen and her friends had arrayed the forces and circumstances to ensure that Paimon would find a corporeal home. (Perhaps Ellen tried Annie’s brother at first; perhaps that’s why he bemoaned that she was trying to “put people in him.”) Strange words and phrases ("satony," "liftoach pandemonium," and "zazas.") are written on the walls throughout the Grahams’ house, and Paimon’s symbol appears on the pole that decapitated Charlie. Steve is not related to Ellen by blood, so he would not have been a suitable host for Paimon. So, Ellen wrestles Charlie away from Annie, wishing that Charlie had been a boy because Paimon prefers male bodies. While the conspiracy to prepare Peter to be Paimon’s host, Paimon inhabits Charlie’s body. After Charlie’s death, someone, possibly Ellen’s fellow conspirator Joan, slips an invitation to a seance into the Grahams’ mail slot. The Grahams don’t attend, so Joan delivers the message to Annie herself one day when she too conveniently meets Annie outside an arts supply store. No outside forces, divine or mortal, intervene in the Grahams’ dissolution. Grief counselors and law enforcement are not concerned with the Grahams after Charlie’s death. Men of God are absent when the demonic plot becomes clear. At least Father Merrin and Father Karras get involved with Regan’s possession in The Exorcist, Katie and Micah invite a psychic to help communicate with the spirit haunting their home in Paranormal Activity, and Ed and Lorraine Warren investigate the spirit that troubles the Perrons in The Conjuring. No help comes for the Grahams; it wouldn’t matter if anyone would have because their dice have already been cast.

Aster deploys a stylistic flourish to reinforce the inevitability of the Grahams’ demise and their helplessness in the face of it. The first scene of the trailer and the film has the camera zoom in on a miniature version of Peter’s bedroom and seamlessly transitions to Steve walking in to wake Peter up for Ellen’s funeral. During Charlie’s funeral, the camera pans downward past the grieving family and into the dirt to imply that they are in a terrarium, a simulacrum of nature that is carefully constructed. Throughout the film, the camera moves horizontally, as though the viewer is viewing a diorama. Aster zooms in on miniatures and movies the camera horizontally to blur the line between the doll and the flesh and blood character throughout the film. By blurring the lines, we are cued to accept that these characters are toys for a larger, unseen, external force.

The sense of helplessness is the heart of the film’s power. We are all manipulated by larger, nearly incomprehensible external forces. Governments with a pretension toward fascism rely on the citizenry feeling cowed into submission and the thought that resistance is futile. Corporations rely on consumers believing that no alternative exists to the services that they provide. Who can realistically fight the powers that be and win? That’s the underlying anxiety that Aster is tapping to power the terror of his film.

The film’s exploration of that abstract anxiety is coupled with the raw family drama of the film’s first half and more traditional scares in the film’s second. Aster loads Chekov’s Gun with an early reference to Charlie’s nut allergy and pulls the trigger in the party scene where she eats a walnut-filled chocolate cake. As an intoxicated Peter races them to the hospital, Charlie struggles to breathe and thrashes in the backseat of the family station wagon. She opens a window and sticks her head out, hoping that the air rushing by could enter her lungs. Peter swerves to avoid a conveniently placed deer in the middle of the road, and Charlie’s head collides with a pole. Wolff is incredible in this scene, as his Peter enters a deep state of denial about Charlie’s death. He drives home and goes to sleep because there’s nothing else his traumatized psyche can manage, and the haunted look on his face as he waits for Annie to discover Charlie’s decapitated corpse in the backseat is magnificent. After Charlie’s death, the family slowly disintegrates. They try to manage with medications and denial, but their inability to communicate grinds away the relationships between husband and wife and mother and son. This first half, built around Charlie’s death and climaxing in the dinner scene, grounds the film in raw grief and is reminiscent of family dramas like Ordinary People and In the Bedroom.

The second half deploys more traditional horror film tricks, from half glimpsed shadows and out of focus scares at the periphery of the frame, to jumpstart the film’s descent into destructive, supernatural inevitability. Watching Hereditary in a packed movie theater meant that there were nervous or dismissive giggles throughout the film, but it was all worth it to hear the audience realize in pockets here and there that Annie, dominated by Paimon, was stalking Peter from the ceiling. Out of focus, the white shape of Annie, clinging to the ceiling like Spider-Man and skittering out of the frame a moment before Peter could turn his head to see her, teases the audience with the scare of when the possessed Annie will make herself known to Peter. You can try to giggle away your nervousness, fellow viewer, but I can feel your tension from here. Here, the emotional rawness of the first half collides with the horror tactics of predecessors like Twin Peaks, The Exorcist, and Rosemary’s Baby. The moment when Annie jumps out of a shadowy corner in the living room and chases Peter to the attic reminded me of when Leland Palmer, possessed by Bob, chases Maddy Ferguson in Twin Peaks, a scene which continues to haunt me. Peter’s desperate dive out of his second story window reminded me of Father Karras’s self-defenestration in The Exorcist. Peter’s ascension as Paimon’s host brought to mind the ending of Rosemary’s Baby, when the Satanic cultists exclaimed that the infant had “his father’s eyes.” Aster ends the film by pulling the camera out one more time to show Peter as Paimon and Paimon’s worshippers in the Grahams’ treehouse as though it were a diorama, and the image is blurry enough that we could think that we were seeing a set of miniatures carved by Annie about this latest tragedy in her family’s unfortunate history.

At first, I was bothered by how much I felt that the film had played a bait and switch game with my expectations. I realized that I’m more to blame for that than Aster. Aster didn’t direct A24’s marketing arm to create trailers that make me think the film is about mental illness and generational demonic possession. That surprise made the raw tension of the film’s first half more striking, which lays the relatable groundwork for the film’s supernatural second half. Aster plays fair with the viewer throughout; there are enough teases in the first half, from Annie’s initial discovery of tomes about spiritualism and Ellen’s haunting postcard that posthumously promised to Annie that all the sacrifices would be worth it, that I didn’t feel blindsided by the supernatural turn. It might feel disjointed; Annie, the film’s grieving fulcrum, meets as subdued a storytelling fate as a scene where she, levitating in the Grahams’ attic, decapitates herself with wire so Paimon can be released from her hijacked body, can ben. Because the film’s storytelling focus had been trained on her, the change in focus to Peter feels abrupt. But there’s power in the realization that the Grahams are all fated for terrible ends and that Peter has arguably the worst fate of all. At least his family members’ demises are swift. Instead, his body is stolen and his soul suppressed, if not consumed, by demonic possession. And, if that’s not the case and it’s all in Peter’s head, as the close shot of his stupefied face in the final scene implies as Joan, offscreen, prays to Paimon, then it’s not a much better end for Peter, who is left orphaned and traumatized.

Krasinski and Aster can take pride in the stylist flourishes and the games that they play with the audience in their respective debut efforts. Krasinski asked the audience to be patient with him for almost a quarter of a film in silence, while Aster led viewers through raw family tragedy before taking a turn into the supernatural. Aster used camera movements to lay the groundwork that his characters are playthings; Krasinski’s cinematography was more workmanlike, but it was effective. The sense of impotence at the center of Hereditary spoke to me more than the optimism springing from love and American pluckiness from Krasinski’s A Quiet Place. There is room for Krasinski’s optimism, and maybe it’s just as important to feel it as it is to acknowledge the external forces that oppress us at which Aster hints. In the face of how easy it would be to give up when one feels so feeble, maybe the optimism and the power of love become even more important.

#a quiet place#john krasinski#emily blunt#bryan woods#scott beck#millicent simmonds#noah jupe#ari aster#hereditary#toni collette#gabriel byrne#milly shapiro#alex wolff#ann dowd#horror

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Only what you take with you”: Extra-textual interaction with Baby Driver, mother!, and Star Wars: The Last Jedi

“What’s in there?”

“Only what you take with you.”

Months ago, I saw Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver, and I couldn’t quite explain my cold reaction to it. As the sum of its parts, it should have been a no-brainer, sure to be favorite. Its soundtrack was full of soulful tracks meticulously curated by Edgar Wright and mixed by editors and the music department. Its stunt driving was breathtaking, orchestrated by a small squadron of stunt performers. Its cast was an alchemical brew of charisma and distance, charm and menace. It should have been one of my favorite films not just of 2017, but of my lifetime of watching movies and haphazardly ranking and re-examining what I can take from them. I admired Baby Driver from a distance, appreciating the stunts, but I couldn’t feel the emotional connection to it that would have anchored it as one of my favorite films. The confusion between this appreciation for the craft and the lack of emotional connection actually kept from writing about the movie because I felt that I had nothing to say about it.

Months later, I saw Darren Aronofsky’s mother! and couldn’t wait to talk about it with the person I saw it with, with anyone who saw it, and with anyone who might be interested in seeing it. It was my mission for a few days to share my passion for this film, something I hadn’t felt since Mad Max: Fury Road. My evangelism for mother! was met by disdain from friends who had hated what Aronofsky was trying to do in that film and his execution; talking about the film with them was the most fun I’ve had in engaging with a film in a while.

Today, I saw Star Wars: Episode VIII: The Last Jedi, with an open mind and low expectations after how listless and small I felt The Force Awakens was. I started tearing up during the opening scrawl; I started sobbing quietly into my coat when Carrie Fisher first appeared on screen. The film itself had done almost nothing to earn this depth of emotion from me at that point, but I felt overcome. When I stepped out, I felt a release and peace; I had needed that experience beyond going to watch a film on a Sunday morning on a whim.

In each case, I concluded that the secret ingredient was in me all along. I didn’t connect with Baby Driver because I didn’t have the anchors to engage with it completely. I didn’t obsess over car-based action movies like Bullitt, The Italian Job, or The French Connection because I didn’t see them during my formative years. I saw them as an adult when I was trying to build a mental library of films that I could reference so I could appreciate the films that came after in context. I didn’t grow up listening to the music that peppered the film’s soundtrack. My point of connection was actually my admiration for Jon Hamm transferring the menace that laid under his performance as Don Draper in Mad Men into violence as Buddy, but admiring an actor’s performance as the film’s antagonist only got me so far. So, without the anchor, my attention was left adrift as I watched the film, left unsatisfied by the relationship between Elgort’s Baby and Lily James’s Debora that never reached the nuclear temperatures that would have provided an emotionally resonant explanation for why they would fall madly in love with each other and why Debora would be devoted to Baby through the years of his prison sentence. I admired the stunt work, but the story felt like it was going through the motions because I didn’t care if Baby was able to ferry his crew safely or survive their betrayals or if Baby would be able to escape Doc’s control. An emotional connection is what helps the viewer close the distance between their eyes and their hearts, and all I had left while watching Baby Driver was the intellectual appreciation for the craft that my brain and my eyes could put together. I’m sure Wright referenced the films, like Vanishing Point or The Blues Brothers that influenced Baby Driver, but I couldn’t play the spot the reference game because I don’t have the contextual knowledge.

With mother!, I could easily identify the game that Aronofsky was playing because he was referencing a fundamental text in Western culture. So, for the first half of the film, I was awed by the audacity that Aronofsky would try to play coy with his retelling of the Book of Genesis and trying to anticipate how he would keep playing the game when he would reach the life of Jesus Christ. I had seen depictions of the relationship between the Judeo-Christian creator God and Mother Nature before in E. Elias Merhige’s Begotten, and I spent years engaging with the idea that the books of the Bible could be treated as literature and with the idea that God could be considered the protagonist of the Biblical narrative through analyses like Jack Miles’s God: A Biography. Aronofsky combined religious caricature with the domestic comedy of a an oblivious husband, a frustrated wife, and guests who outstay their welcome. Because Aronofsky worked with a fundamental text, the film could also be open to interpretation, from a fairly straight retelling of chapters 1-11 of the Book of Genesis and a reinterpretation of Jesus Christ that would fit comfortably along side Miles’s Christ: A Crisis in the Life of God and Begotten to an environmental parable to criticism of organized religion. It could be seen as Aronofsky’s companion piece to his previous film, Noah, which focused on chapters 6-9 of the Book of Genesis, or the latest cinematic step in Aronofsky’s search for spiritual meaning that began with Pi. I am, admittedly, a fan of Darren Aronofsky’s work; we’re alumni of the same summer camp, and seeing his name is often enough to engage my interest in a film. With all these potential points of association, it was easy for me to connect my eyes, my brain, and my heart to the film.

I commented to a friend that I couldn’t believe that it’s been only two years since we saw Mad Max: Fury Road together because it’s felt so much longer. Despair can elongate the sense of time’s passing; 2017 has been full of anger and despair, so it’s no wonder that this year has felt like a decade. When I sat down to watch The Last Jedi, I was unprepared by how badly I needed something to tell me that there was still hope in resisting against oppression, corruption, and the general darkness. I could point to how nonsensical the First Order’s strategy of engagement with the Resistance was, how confusing the First Order’s actual strength of force was, and how tangential Finn and Rose’s story felt to the film’s larger narrative. On the other side, I could point to how Rian Johnson mastered the craft of giving viewers memorable tableaus, from the blinding red of Supreme Leader Snokes’s throne room to how the salt changes color as the First Order and the Resistance battle on Crait. In the end, it was the emotional charge of seeing Carrie Fisher in her last role, wondering how Fisher and Mark Hamill bore aging in front of us, lifting the weight of years to sift through memories of watching Star Wars movies and shows, reading Star Wars books, listening to the music of Star Wars that struck a chord. It was the thought of how popular culture has appropriated Princess Leia into a symbol of resistance, and how that appropriation is tied to the fact that Star Wars is an intellectual commodity marketed and sold by one of the biggest corporations in the world creates a tension that works for and against it. Roger Ebert described movies as “like a machine that generates empathy.” I recognize how silly and naive this sounds, but The Last Jedi, a film that cost hundreds of millions of dollars to make and will nearly billions for The Walt Disney Company, generated hope for me. I think Rian Johnson realizes that tension too; it’s not a coincidence that he ends The Last Jedi with a scene of a child telling two other children the legend of how Luke Skywalker stood up to the First Order alone and how that sparks one of the listener’s hope. Even if the message was made and transmitted for the sake of commerce, the power lies in how the audience receives it and what it inspires the listener to do.

In each case, the secret ingredient was what I was took with me from outside the cinema. I didn’t have the context to play the “spot the reference” game with Edgar Wright’s Baby Driver, so I was left grasping for an emotional connection. Between my appreciation for Darren Aronofsky’s films and years of thinking about religion, I was fully prepared and engaged with the game that Aronofsky was playing with the audience with mother!. And my unsuspected craving for hope with me left me unable and unwilling to nitpick The Last Jedi, to carve it up into its component parts because the sum is too great.

#baby driver#edgar wright#ansel elgort#lily james#jon hamm#elza gonzalez#jamie foxx#jennifer lawrence#mother!#darren aronofsky#javier bardem#michelle pfeiffer#ed harris#star wars#star wars the last jedi#the last jedi#rian johnson#daisy ridley#John Boyega#Oscar Isaac#Carrie Fisher#mark hamill#adam driver#begotten

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Big Sick (2017)

Trailer

Every now and then, I’ll meet a couple whose shared story of how they ended up together seems so outrageous or is well told that one listener will inevitably say that they could make a movie about it. It makes sense that the couple’s story is recited with skill; their delivery is refined with re-telling, and they come to know the story’s beats like they, in theory, know each other.

Here, with Emily Gordon and Kumail Nanjiani’s The Big Sick, we actually have a story about how two people ended up together that was turned into a film, with some liberties taken along the way. Nanjiani, playing a fictionalized version of himself, is charming and disarming in a low key way. His playful and deadpan nature draw you to engage with him while his murmuring delivery makes you want to listen to him even more closely. Zoe Kazan, as Kumail’s girlfriend, Emily Gardner, is vivacious. Her presence is felt by its absence during the middle of the film when she is in a medically induced coma. Ray Romano reminds us with his performance as Emily’s father, Terry, that his dramatic work is underappreciated and that his 2009-2011 television show, Men of a Certain Age, is woefully absent from the many different streaming platforms that are ravenous for content. Holly Hunter, as Emily’s mother, Beth, is her usual force of nature, intimidating but loving. Relationships are about more than one love story. They can be as much about how the couple bonded as much as it is about how people make each other’s family fall into love with them too. Because Hunter’s is so fierce, you root for Kumail to win her over as he processes his regret from breaking up with Emily.

The story is focused on Kumail’s decision to stay with Emily and support her parents as they try to stay sane during Emily’s coma, but it skips over the parts of the story that interest me most. I suppose that the film invites you to draw your own conclusions about why Emily would seek Kumail out in New York after she tells him that they can’t resume their relationship. While she was sleeping, he changed, and she couldn’t process this new information about him. We’ve spent two hours at that point with Kumail, and we saw that he and Emily made a great couple when they were together. We’ve seen his willingness to challenge the pressure from his family to follow tradition and marry a Muslim woman or be separated from his family. The film would have failed if I can’t imagine why Emily would choose to reconnect with Emily.

Instead, the most interesting part of the film is the glimpse of how the Muslim women who are scheduled to meet Kumail feel. They are invited to meet Kumail by Kumail’s and their parents in order to arrange a marriage. The first woman we meet is not named in the film; she is nervous, almost desperate to win Kumail’s approval by making references to The X-Files. Later, we are introduced to Vella Lovell’s Khadija, who impresses Kumail and his family with a magic trick. There was enough of a spark of chemistry between Kumail and Khadija that I thought that the film could explore it as one more source of tension in the story of Kumail and Emily’s relationship. Kumail’s mother invites Khadija and her family to meet Kumail later in the film, and Kumail rejects Khadija. Kumail tries to apologize and tell her that she deserves someone better than him, and she counters, in a tired voice, that she feels like a bruised apple because she has been sent to try to impress many potential husbands and that she just wants to be in a relationship so she can finally relax. The movie finds its tension in how Kumail wants to reject his family’s cultural traditions, but the most interesting story is actually in how the women deal with the pressure from their families to become married and start families. That’s a well-trod topic for romantic comedies, from 27 Dresses to other, much better romantic comedies, but the appeal comes from exploring it from the perspective of Muslim woman who has to make these appointments to meet potential husbands.

Perhaps the resolution would be as low-key as the way that Kumail resolved the tension with his family. His parents confront him after he fails to appear at a dinner to which they invited Shunori Ramanathan’s Sumera, leaving them stumbling to cover for his absence and misunderstandings about her fluency in Urdu with awkward singing and lame excuses. He finally reveals that he had been dating a woman outside of his culture and religion and that he does not pray when they think he does because he does not feel their religious compulsion. Exasperated, he asks questions familiar to adults who emigrated to the United States as children: “Why did you bring me here if you wanted me not to have an American life?” They threaten to disown him, but he rejects that threat because he doesn’t want to leave the family. The threat that hung over Kumail for much of the film is almost too easily defused; even after they disowned him, Kumail’s brother attends one of his one-man shows, while his mother and father come to his apartment to give him a meal for his trip to New York and a request to text them when he arrives. The film requires us to side with Kumail and to root for Kumail and Emily’s relationship to make the narrative choice to defuse the threat this way work and not ask why Kumail couldn’t have just as fulfilling a relationship with, for example. Nonetheless, Khadija’s story deserves to be told, even if the story about how Khadija eventually met her partner might not be so dramatic that it gets made into a film one day.

#the big sick#kumail nanjiani#emily v gordon#zoe kazan#ray romano#holly hunter#anupam kher#zenobia shroff#vella lovell#shunori ramanathan#films#movies

0 notes

Text

The LEGO Batman Movie (2017), Logan (2017), and The Fate of the Furious (2017)

Trailer

Trailer

Trailer

I’m at an age where many of my friends have become or will become parents. Since I was the first person in my peer circle to become a father, they sometimes turned to me to ask what advice, practical or philosophical, I could give about becoming a parent. By this point, I’ve refined my patter to a performance. I will consistently tell my friends, “Don’t have kids.” Either that draws them in further to inevitably ask why, or they take the words on the superficial level and move on with the conversation. If they ask why I, a father of a delightful kid, would say that, I ask if they want the practical or the philosophical reasons. The practical reasons are simple: having a child is a major financial commitment, a guarantee that you will never have a sound night of sleep ever again (and not just because an infant’s needs will interrupt your sleep), and a turning point in the relationship that you and your partner have. You and your partner’s relationship may not survive; the roles that you and you partner played in the relationship before you became parents will not be the roles that you will play after. The philosophical reasons are based in pessimism: if we accept that any actions that lead to the suffering of others is immoral, then having a child is an immoral act because human sentience means that we all live in constant pain born from a terror of knowing that our lives are finite. We are always dying. We die every second. In response to the absurd notion that we are born only so we can live to know that we will die, the most common options are: commit suicide, embrace the absurdity of life, or to recognize how absurd life is and rebel. How could you then morally justify creating life?

What could have been in the creative air to inspire three major blockbuster films (The LEGO Batman Movie, Logan, and The Fate of the Furious) from three different distributors (Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, and Universal Pictures, respectively) to tackle the ideas of family unity and fatherhood in three different ways? (And it’s noted that these three films offer their takes on fatherhood specifically, not parenthood.) I suppose it’s natural that someone will explore the paradoxical idea that characters like Batman and Wolverine, who are so often defined as loners who don’t believe that they deserve human connections to other people would actually have many relationships that form an extended family with characters who choose to be with them. In other words, you could imagine Batman, Wolverine, and Dominic Toretto each saluting their respective families with their beverages of choice.

Colorful and bombastic, The LEGO Batman Movie contextualizes the characters around Batman as his extended family. From Alfred the patriarch (voice by Ralph Fiennes) to Batman (Will Arnett) to Batman’s adopted son, Robin (Michael Cera), to Batman’s co-dependent nemesis, the Joker (Zach Galifianakis), to Batman and Joker’s extended work friends and acquaintances like Harley Quinn (Jenny Slate), Barbara Gordon (Rosario Dawson), and Clayface, the many bonds that Batman has with the world around him are highlighted in bright neon explosions. As Batman’s surrogate father and like a father who worries about his kid’s ability to make the right kind of friends at school or meet the right partner, Alfred worries about his charge’s ability to form social bonds that will sustain Batman if he were to ever die.

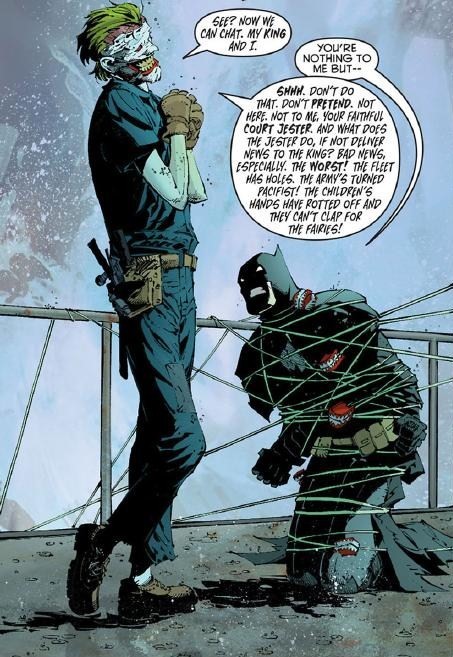

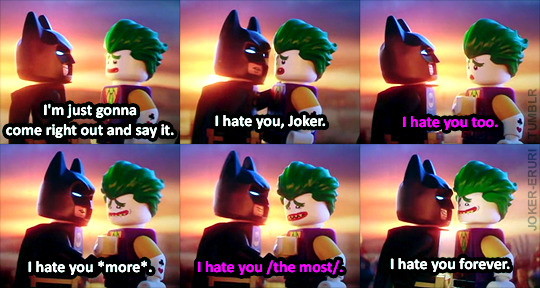

The film’s inciting incident is Batman breaking the Joker’s heart by telling him that he means nothing to him; the movie ends with a play on romantic comedy beats by climaxing with Batman and the Joker telling each other that they hate each other. It’s the psychosexual dynamic between the two that Frank Miller famously explored in The Dark Knight Returns and Scott Snyder years later in “Death of the Family” sanitized for the elementary school set.

The cinematic versions of Batman always come around to embrace the idea that Batman isn’t the loner that he thinks he is. He travels with gods like Superman and Wonder Woman. In The LEGO Batman Movie, he craves the attention from his peers in the Justice League so badly that he has to put up a front to pretend that he doesn’t want it when he doesn’t get it. In other films, he actually founds the Justice League.

He’s also a father figure, whether in the figurative sense (Batman’s vigilantism gives birth to a more demented class of villains, and his rogues slowly transition from mobsters to supervillains) in a more literal sense (Batman becomes the guardian to the various Robins over the years and the central figure in a cohort of vigilantes, from the Huntress to Spoiler to Red Hood to Batwoman to Batwing). Michael Cera’s performance as Robin in The LEGO Batman Movie makes the character guileless and eager to please than normal to contrast with the bravado that Will Arnett infuses into his Batman.

Like his bald counterpart in The LEGO Batman Movie (coincidentally portrayed by Ralph, another Englishman, Fiennes), Patrick Stewart’s Charles Xavier is concerned that Logan (Hugh Jackman) will lose his chance to reforge a connection to the wider world around him in Logan. Bitter, broken-hearted, and betrayed by his body, Xavier insists to Logan that there is still time for him to reconnect with the world after the rest of the X-Men were killed when Logan meets Laura (Dafne Keen). Logan, Laura, and Charles’s adventure across America remind Logan what a warm household full of affection, as the X-Mansion might have been once, looks like compared to the dusty and solitary existence he, Caliban (Stephen Merchant), and Charles lived in Mexico as he tried to raise enough money to go somewhere so he and Charles can die in peace. As Logan undergoes this journey and reforges connections, he travels from a dusty broken down industrial plant to a neon-bathed city to a corn farm and back to nature, his soul undergoing a revival even as his body continues its breakdown.

Both Logan and Batman begin their films as reluctant fathers, each haunted by loss and unable to figure out the hedgehog’s dilemma. Both are convinced that their lonely lives are the only ways that they can pass their days. Both are pushed by their surrogate father figures to bond with children who unexpectedly enter their lives. And both try to demonstrate their acceptance of the responsibility of fatherhood through sacrifice. Logan overdoses on a drug in order to protect Laura and her friends from a physical avatar of his wild past, while Batman volunteers to return to the Phantom Zone to honor the agreement he made with the Phantom Zone’s keeper that allowed him to return to save his fledgling family.

There’s a thrill to seeing Logan cut a bloody swath across the screen, but the film’s melancholy gives it a bitter taste. The shock of Logan cutting off an arm from a man who was trying to steal the tires from his rented limousine is undercut by how hard it was for the legendary Wolverine to fend off those four men. The excitement of Logan bearing his claws at Donald Pierce (Boyd Holbrook) and the Reavers is undermined by how ineffectual Logan is against them. You might be surprised that Logan is casually murdering Reavers who were trying to capture Xavier, but the surprise is subverted by the realization that the Reavers were completely defenseless and neutralized by Xavier’s psychic seizure. Logan facing down goons to help Will Munson (Eriq La Salle), a farmer that he helped on his journey, but his violence against the Reavers and the goons only brings more violence upon the Munsons, which leaves them all dead. In the climax, Logan is temporarily restored to his former vitality due to a healing serum, but by the end of that burst of violence, Logan can barely stand. Violence in Logan is a bittersweet fruit.

Every time Logan fights the Reavers, they come back with more and stronger soldiers. When he faces them in Mexico, the Reavers have heavily armed Mexican police officers riding in SUVs. By the time that he faces them in North Dakota, the Reavers have armored trucks, jeeps with mounted machine guns, and a young feral clone of Logan. Nonetheless, Logan can’t help but feel fatherly pride during the climactic fight against the Reavers. Laura had already saved him once after he collapsed on the side of a highway by getting him medical attention. But he becomes proud of her when she fights to defend her friends against the Reavers, and they coordinate their attacks. They bond through violence because, as Xavier said, they’re very alike.

The price of violence makes explicit the idea that becoming a parent raises the stakes. One might be tempted to quit an unsatisfactory, unfulfilling, underpaying job, but the income or health insurance from that job might be the only thing that protects your family from deprivation. One might be tempted to lash out at the world or to go it alone, but that might be the selfish thing to do.

James Mangold, the director of Logan and one of the screenwriters, along with Scott Frank and Michael Green, unintentionally struck political relevance in the current political climate. The film’s development began in 2013, and the screenplay was complete by early 2016, around the same time that Donald Trump was campaigning for President of the United States on a platform of xenophobia and racism. In the film’s opening scenes, we see Logan chauffering four young white men past a Mexico-US border checkpoint. They’re standing through the limo’s sunroof, chanting “USA!” at the immigrants waiting to pass the border. By March 2017, President Trump’s administration is floating trial balloons to test the idea of separating women and children who are caught crossing the Mexico-US border together. Laura and her friends are Mexican children whose humanity has been denied by a corporation so they can be experimented upon and trained to be weapons. As Donald Pierce references repeatedly throughout Logan, Laura and her friends are commodities, patented intellectual properties of the company that employs him. Whereas other X-Men stories would be metaphors about how the Other is demonized, here the Other is completely dehumanized. Principal photography for Logan ended in August 2016, but the idea that Laura and her friends are not seeking refuge in the United States because the United States is not a hospitable place for children born from Mexican mothers and the image that they are running toward the Canadian border to seek asylum make for accidentally potent juxtaposition.

While The LEGO Batman Movie and Logan present their protagonists in trigenerational families, The Fate of the Furious presents two different types of families. There’s the circle of friends that become a family that Dominic Toretto (Vin Diesel) often toasts with a bottle of Corona. Then, there’s also the son that he and Elena (Elsa Pataky) created during their relationship when he thought that Letty (Michelle Rodriguez) was dead. Dominic accepts fatherhood without reservation and is willing to betray his la familia in order to protect his biological family until he can find a way to save his son from Cipher (Charlize Theron, mostly underutilized in the film), a legendary cyberterrorist who is blackmailing Dominic to steal an EMP device, a Russian nuclear football, and a Russian nuclear submarine for her.

There is, of course, another father in la familia who is noticeably absent. Brian O’Conner (Paul Walker), Mia Toretto, and their son are written out of the film with a line delivered by Letty to explain that they cannot contact Brian for his help in subduing Dominic and capture Cipher. Within the context of the film, this allows Brian and Mia to raise their child in peace, though I cannot imagine that they would feel much peace watching news reports of the theft of an EMP device in Germany, the assault on a Russian defense minister in New York City, or the chaos in New York when la familia attempted to take Dominic down. Outside of that context, this allows Walker, a father himself, to live on through his character.

With Brian removed, The Fate of the Furious screenwriter has to pile the human pathos on to Dominic, Letty, and Elena, and the film creaks and moans under the pressure. Making Dominic a father certainly raises the stakes for him, and the film is focused only on what becoming a father would mean to Dominic. Unfortunately, the film again can only define Dominic’s fatherhood by his sacrifice of his honor and his betrayal of his familia; the film is completely uninterested in Elena’s experience or perspective as the child’s mother. Because the existence of Dominic and Elena’s son is a shock revelation, there’s no time for them to form a connection or for the viewer to form a connection to them. We feel sympathy for Dominic in theory (one can only imagine the horror of someone holding your child hostage and leveraging them to make you commit crimes and betray your loved ones), but the film tries to split our focus by making us feel the pain from Letty’s perspective as the loved one who is abandoned for unexplained reasons. It’s an attempt to give Dominic a shade of humanity, but it’s done only in abstract.

By comparison, we have a better sense of the surrogate paternal relationship between Mr. Nobody (Kurt Russell) and his trainee, Little Nobody (Scott Eastwood) or between Hobbs (Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson) and his daughter, Samantha (Eden Estrella). Hobbs is a devoted father to Samantha and a committed coach to her soccer team; the cinematic appeal of their relationship lies in Johnson’s charm and their characters’ shared history, which dates back to Furious 7. Even the Nobodies evoke a more real emotional reaction than Dominic and his son because we see how they interact with each other and how Mr. Nobody tries to teach Little Nobody the tricks of the trade.

Without the human connection, the spectacle of The Fate of the Furious felt hollow. I should have been wowed by remotely controlled cars barreling through New York City’s streets and raining from parking lots in skyscrapers, but I was bored. I should have been impressed when Dominic and company were racing across ice away from a nuclear submarine, but I was bored and almost nodding off. While the stakes for Dominic as a character were raised with his son’s introduction, the movie itself felt rote, from Cipher’s poorly outlined motivations to a moment that upends the importance of family that is the core of the franchise.

Dominic pays tribute to the bond between his peers that form la familia. However, there is dissonance in the way that Letty, Roman (Tyrese Gibson), and Tej (Chris “Ludacris” Bridges) seemed to have no objection to Deckard Shaw (Jason Statham) joining the team. Shaw murdered Han Lue/Han Seoul-Oh and attempted to kill Dominic, Mia, Brian, and Mia and Brian’s son in Furious 7. Even though Dominic was desperate, contacting Deckard’s mother (Helen Mirren) in order to convince her to persuade Deckard and Owen Shaw (Luke Evans), who has his own disagreeable history with Dominic and company, to save Dominic’s son seemed to betray Han’s memory and to put aside the threats that were made to his family.

The LEGO Batman Movie, Logan, and The Fate of the Furious presented their respective protagonists in non-traditional families. Batman adopts Robin, and they form a trigenerational family with Alfred. Logan becomes Laura’s de facto guardian, and they form a trigenerational family with Xavier. Dominic, Letty, and Dominic’s biological son form a blended family. Indeed, the only traditional nuclear families that we see in these films are the Waynes, which is broken when Batman’s parents are murdered, and the Munsons in Logan.

You could strain to draw a connection between how casually the Munsons are killed to how dystopian the world in Logan is, but the Munsons’ deaths feel almost cruel. From the moment that Logan stops the truck to help them wrangle their horses, the audience begins to wait for the Munsons to die. It gives the otherwise tranquil scenes of Logan, Xavier, and Laura observing what a normal family looks like as they dine together suspenseful tension. Their deaths for doing nothing more than extending hospitality to Logan, Xavier, and Laura felt like a manipulative exercise in cynicism and nihilism. They’re collateral damage in Logan’s violence trap, and the viewer empathizes with Will Munson when he pulls the trigger on Logan after they’ve incapacitated X-24, the younger, feral clone of Logan that was sent to subdue and capture Laura. With his dying breath, Will doesn’t distinguish between X-24 and Logan because they are both monsters that trampled the Munsons’ lives. That the gun’s chamber was empty only emphasizes that violence, even in the cynical world of Logan, isn’t a solution.

Finally, if we accept the notion that becoming a parent is one of the few rites of passage into adulthood left in today’s America, then the other side of that passage is observing your own parents’ decline and eventual death. In Logan, Charles Xavier is suffering Alzheimer’s disease, and Logan and Caliban are Xavier’s sole caregivers. When Xavier doesn’t recognize Logan, he is afraid of him because, to Xavier, Logan is the person who drugs him into unconsciousness. When Xavier is awake and lucid enough to recognize Logan, he berates him for being a disappointment. Xavier’s seizures cause Logan physical pain, and his words cause Logan emotional pain. Xavier is angry at himself and Logan because he needs Logan’s help with something as fundamental as using the bathroom; Logan is resentful for Xavier’s role in the Westchester incident, the physical and emotional pain that Xavier causes him, and the fact that he has to take care of his father figure in his decline.

It was curious to me that three different and big budget films released within two months of each other wove in different ideas about fatherhood into their tales. Each film tried to examine its respective protagonist through the lens of fatherhood and came away with slightly different conclusions. Batman, for as much as he describes himself to be a loner, is character with myriad connections. Logan, another self-professed loner, can’t help but to connect to his daughter when they both do what they do best, even though what they do isn’t very nice and could trap them in cycles of violence. Dominic, a man who talks constantly about his familia, showed that his biological family is ultimately more important to him than the friends and peers around him.

#the lego batman movie#will arnett#michael cera#ralph fiennes#rosario dawson#zack galifianikis#jenny slate#logan#Marvel Studios#warner brothers animation#hugh jackman#patrick stewart#boyd holbrook#dafne keen#eriq la salle#elise neal#the fate of the furious#f8#vin diesel#michelle rodriguez#tyrese gibson#kurt russell#scott eastwood#ludacris#chris bridges#movies#films

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

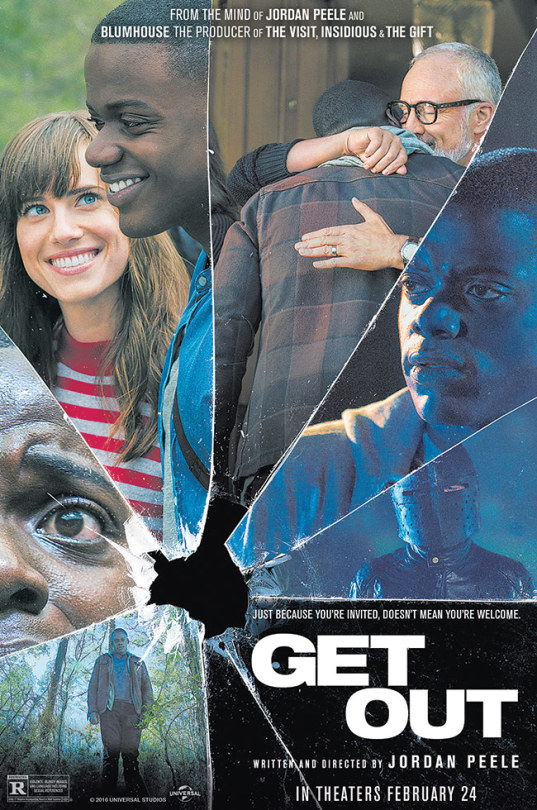

Get Out (2017)

Trailer

It’s taken me a while to process this film and try to figure out what to say about it for no less reason that it feels awkward for an Asian person to comment about a horror film that is couched firmly in the black American experience. Compared to other writers, I felt unqualified to try to analyze what Jordan Peele has extracted from his life and mixed with horror. It was awkward from the start to think that I could feel the danger that LaKeith Stanfield’s Andre Hayworth felt while a car followed him down the street as he tried to walk through a suburban neighborhood at night. I haven’t felt that danger in my life no matter where I am and what time of day it is.

And that’s Peele’s point to a viewer like me.

As an Asian person, I exist in that awkward racial limbo where I’m not perceived as “bad” as black and brown people but will never as good as a white person. I’ll always be considered an outsider in white society no matter how well tailored my clothes are, how expensive my watches and ties may be, how much I try to stay out of the sun to avoid a suntan, or how many different lotions or ointments I use to make my skin “white” and “flawless.”

(And yes, part of the cultural stigma of the suntan is to avoid the connection to outdoor work that the poor do, and fair skin is associated with wealth. But it’s hard to separate race from economic status, especially when you see the range of skin whitening products available elsewhere.)

White remains the standard of beauty for women in America, especially if the woman has Anglicized features (smaller noses, thinner lips, less prominent curves) and straight hair.

Because I’m part of the “good” minority in America, I might be able to date a white woman without causing as many social waves as a black man would. Nonetheless, it is more culturally acceptable for a white man to date an Asian woman than for an Asian man to date a white woman. Except there is no “good” minority in America; there are only short memories and examples from history that are conveniently left out of textbooks. I never read about the Chinese massacre of October 24, 1871 in Los Angeles, in which an estimated 17 to 20 Chinese immigrants were tortured and hanged by a mob of nearly 500 people, in middle school, high school, or college American history texts, even though it is the largest incident of mass lynching in American history. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 gets no more than a paragraph in most textbooks; the Immigration Act of 1924′s ban of Arab and Asian immigrants is not as frequently discussed as the act’s restrictive effects on the immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans. Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, signed into law on March 9, 1942, primarily targeted people of Japanese ethnicity, and over two thirds (almost 70,000) of the 120,000 Japanese men, women, and children who were evicted from the West Coast of the United States to internment camps were American citizens.

Even if you delude yourself into thinking that you’re safe in America because you’re part of the “good” minority, the American media will remind you that the standard #NoAngel playbook for when a member of the minority in America confronts authority in America will still apply to you. Your personal history will be dragged for any crimes to justify the authority’s use of force against you; you’ll be lucky if the police officer or security agent who used force on you is ever identified, much less charged or prosecuted. Forget about hoping for a conviction, especially if that person is a police officer. You will be told that you should have handled the interaction differently because it will always be your fault that the authority had to use force against you. The media will never take the position that use of force was unreasonable or excessive; you deserve to be treated roughly because you’re a minority.

This brings us to the moment in the film when Peele has Yasuhiko Oyama’s Hiroki Tanaka ask Daniel Kaluuya’s Chris Washington, “Is the African-American experience an advantage or disadvantage?” Why have one minority, the only Asian character in the film, ask a member of another minority if there experience is an advantage? It could be that Tanaka is trying to figure out how much he should bid for Chris’s body since we see Tanaka in the bingo game slave auction later in the film. It could be Tanaka, as one of the “good” ones, is curious and blunt enough to ask that question directly; the question is about two steps removed from asking to touch Chris’s hair, and it encapsulates the microaggressions and racist dehumanization that Chris endures during that party scene, from the golf fan’s question about whether Chris swings a golf club like Tiger Woods or the question from the older woman whose husband is dying about the size of Chris’s penis and his sexual prowess.

Though Tanaka disappears from the film after the auction scene, his brief appearance is enough to highlight that Peele deliberately inserted an Asian character into this film because we Asians, as the model minority, are very complacent about our role in the civil rights struggles around us. Tanaka might believe that he would benefit from the subjugation of a black man as much as the other bidders in that auction, but who’s to say that his family wouldn’t be subject to subjugation one day? The Armitages may have chosen black people to be the vessels by which they and their peers can extend their lives by literally exploiting black bodies because they believe that black bodies are physically stronger, but Stephen Root’s Jim Hudson also points out that they’re selected because black people are cool. Would it shock anyone if Asian people were once selected during the peak of Bruce Lee’s popularity in this scenario because East Asian culture was in vogue? Couldn’t you then connect how easily Asian characters can be portrayed by non-Asian actors to how replaceable minorities are to the white majority?

Sometimes, it’s as simple as giving an actor angled eyes or a conical hat to transform a non-Asian actor into an Asian character. After all, black face isn’t in vogue in these times, so you can’t expect a non-black actor to play a black character unless you’re setting out for a deliberate provocation.

Of course, Asians are seen as “the model minority” in part because they’re perceived to be meek and safe. The simple fact that Asians were not forcibly removed from their homes and sold into slavery in America colors the perception that they are a safe minority. There are no distant memories of slave riots. There is no unresolved national shame of slavery. There isn’t the notion that Asians were selectively bred in order to generate the strongest, fastest, and most durable children, which gives Asians a dangerous physical advantage that extends to today. Asian children aren’t referred to as demons or compared to musclebound, larger than life professional wrestlers like Hulk Hogan.

The idea that the Armitages and their peers only want black bodies is directly connected to the idea of slavery, of owning black bodies and counting their labor power and their families as part of the slave owner’s wealth. Peele draws that connection explicitly, whether it’s to extend an Armitage’s life or to replace a failing body for someone’s sexual gratification or simply wanting a black photographer’s eyes because the black person’s artistic skills that were honed through practice and shaped by that person’s experience are irrelevant. Part of the horror lies in how little anything but their physical bodies about Chris and the Armitages’ other victims matter to the Armitages and their peers.

Furthermore, once the Armitages and their peers have taken control of black bodies, those black bodies are then severed from the American black cultural experience. Andre Hayworth is renamed Logan King. Rose’s grandparents assume Georgina’s and Walter’s bodies, but the viewer never sees them interact. Neither Georgina nor Walter interacts with Andre/Logan. The horror also lies in how the Armitages place no value in black culture.

Peele does not invite the viewer to consider the connection between the fact that the United States has both the largest incarcerated population in the world and the highest incarceration rate in the world (USA! USA! We’re #1!) and the disproportionately high rate of incarcerating black Americans compared to white Americans in certain states’ prisons. Nor does Peele invite the viewer to consider the connection between America’s incarcerated population and the economic benefit America extracts by force from its incarcerated population. Nonetheless, a viewer could certainly draw that connection given the context and the information to draw a conclusion about the systemic dependence on black bodies.

The film wouldn’t have stayed with me for this long if it weren’t an effective horror film that subverted expectations in important ways and played horror tropes straight where it counted. Other reviews have focused on how Peele has created a horror film that uses horror storytelling devices to enhance his extrapolation of the terror of the black American experience and punctures the tension with comedy to great effect. This week’s reminder that there is no such as thing as “the model minority” helped to cement what my takeaways from watching Get Out were. It might have been a warning to Chris to save himself, but it’s also an exhortation to me to get out and be active because we’re all in the struggle for civil rights together.

#get out#jordan peele#daniel kaluuya#allison williams#bradley whitford#catherine keener#caleb landry jones#lil rey howery#betty gabriel#marcus henderson#lakeith stanfield#stephen root#erika alexander#keegan-michael key#horror#films#movies#toby oliver

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Wick: Chapter 2 (2017)

Trailer

John Wick: Chapter 2 is the latest zombie film to be released by Hollywood. Though Keanu Reeves did not need to spend hours in the make up chair to be covered in fake rotting flesh, his character, John Wick, is covered in viscera, the results of his battles across the world against his fellow denizens of the underworld. Like the flesh hungry horde of The Walking Dead, Wick strides forward, undeterred by the many injuries to his body, to satiate his appetite for revenge.

The zombie is defined by its single-minded pursuit of bloody, vital meat, and a mere pound of flesh isn’t enough for Wick after Santino D’Antonio (a slimy Riccardo Scarmacio) blew up his house, his treasure trove of memories of his dead wife, Helen Wick (Bridget Moynahan, given nothing to do but to be the object of Wick’s regrets). Santino blew up Wick’s house because Wick refused to fulfill his debt to Santino, claiming that his adventures in the first John Wick did not mean that he was back from the dead (or back among the soon to be dead who don’t know yet that they’re going to be dead, most likely at Wick’s hands). Wick then kills Santino’s sister, Gianna D’Antonio (Claudia Gerini) to fulfill his debt to Santino, which allows Wick to kill Santino for blowing up his house and destroying the last pieces of his civilian life.

Speaking of flesh, it’s said that an eye for an eye makes the world blind. On the contrary, each of Wick’s violent acts in his quest for vengeance turns more eyes toward him until every eye in the world is watching him. He attempted to break the cycle of revenge by offering peace to Abram Tarasov (Peter Stormare), brother of Viggo and uncle of Iosef from the first John Wick, in exchange for his car, the other major fetish of his civilian persona and his wife’s redemptive, life-affirming love. However, he kills Gianna so he can kill Santino. By killing Gianna, he inspires Cassian (Common) to pursue him because Gianna was Cassian’s charge. If Cassian were successful, one of Wick’s acquaintances, such as Aurelio (John Leguizamo), could feel obligated to avenge Wick. Santino assigns his henchmen, including his bodyguard, Ares (a magnetic Ruby Rose), to monitor him and try to kill him after Wick killed Gianna. Wick’s pursuit of Santino ultimately leads him to violate the Continental Hotel’s code, which renders him ex communicado from the world of assassination in which John Wick had played the bogeyman for so long. Wick warns Winston (Ian McShane), the owner and operator of the Continental Hotel in New York and emperor of the world of assassination, that he will kill everyone who tries to hunt him. Nonetheless, it’s an empty threat as every eye, knife, and gun turns to watch Wick as he first walks confidently, then runs in a panic out of New York to try to find sanctuary.

Wick is as much a dead thing as Marvel’s The Punisher, a man who has nothing but his bloodlust for criminals in order to fill the void that his wife’s and children’s deaths left. Santino, like children, shouldn’t have played with a dead thing like Wick. He wanted to resurrect the old death-bringing John Wick so Wick could kill his sister, but he brought back a terrible thing to the world.