Exploring the text and context of sacred dramatic works by drawing upon expert commentary and Academy of Sacred Drama member contributions.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

NEW YORK BAROQUE INCORPORATED PRESENTS ALIOTTI'S SANTA ROSALIA

Academy Journal Beta.1, 16-17 (2017) Printed in the United States

CC BY-NC-ND

By Christopher Browner June 1st, Trinity Church, Manhattan

There was a palpable sense of anticipation inside Manhattan’s historic Trinity Church as audiences arrived to hear New York Baroque Incorporated’s (NYBI) premiere of a new edition of the resurrected oratorio Santa Rosalia by Italian organist and composer Bonaventura Aliotti. Originally written in 1687 for a festival celebrating Saint Rosalia, patron saint of Palermo, the work survived only as a manuscript in a private collection for centuries. So NYBI’s performance, with music director Lorenzo Colitto leading an orchestra of 13, simultaneously felt like a glimpse into the past and an exciting world premiere.

Aliotti’s score seems to take inspiration from the likes of Monteverdi and Purcell, combining vivid text setting, multifaceted characters, and music of both virtuosic agility and insightful emotion. Throughout, the NYBI orchestra imbued the work with a wealth of instrumental color and conjured vivid imagery with their playing. One striking example came during a scene in which Rosalia etches her vows in stone. Here, Aliotti uses percussive string figures to depict the unmistakable sound of a chisel. Credit also must be given to keyboardist Dongsok Shin and cellist Ezra Seltzer who displayed great artistry in their handling of the continuo accompaniment for recitatives.

The oratorio tells a rather simple story. As the title character, a wealthy noblewoman in 12th-century Palermo decides to forsake her worldly station and become a pious hermit, various allegorical figures—Penitence, Ambition, and Sense—vie for influence over her choice. Each character is given ample music with which to make their case, and in the hands of the NYBI soloists, much of it was quite compelling.

As Rosalia herself, Dutch soprano Johannette Zomer deftly conveyed the character’s inner struggle. In moments of plaintive yearning, her singing became incredibly lyrical, but Zomer also delivered impassioned passages of fiery fioritura. Her rendition of the aria “Infelice, seguire non so,” in which Rosalia is crippled with indecision, kept with 17th-century stylistic conventions while also being instantly relatable to modern audiences.

Molly Netter lent a hauntingly elegant soprano to her performance as Penitence, spinning affecting phrases and skillfully using straight tone. When she returned in the second half as a glorified vision of the Virgin Mary, her singing became more exuberant while still maintaining graceful dignity.

Clad in a striking cape and golden earrings, mezzo-soprano Kate Maroney sang the role of Ambition with a rich, penetrating timbre. She excelled at delivering intricate coloratura lines, but, whenever part of an ensemble, she tended to be overpowered by fellow singers. Likewise, tenor Owen McIntosh brought a light—though bright and focused—instrument to his role as Sense. And as Lucifer himself, Dashon Burton sang with a commanding bass-baritone that contrasted nicely with his colleague’s higher voices.

NYBI should also be commended for its efforts to make this unknown work accessible for audiences. From a full, printed English translation to simple-yet-effective stage direction by Marc Verzatt, the story unfolded naturally from beginning to end. Hopefully, having had success with this presentation, Aliotti’s Santa Rosalia will no longer be an obscure footnote of musical history.

Christopher Browner is the Associate Editor at the Metropolitan Opera and served as Opera Critic for the Columbia Daily Spectator between 2012 and 2016. In addition to his writing, he has directed operas in New York and Connecticut and regularly gives guests lectures for the Columbia University Music Department.

#new york baroque incorporated#nybi#academy journal#academy of sacred drama#christopher browner#review#reviews#santa rosalia#bonaventura aliotti#music

0 notes

Text

TWIN ADVOCATES: HOPE AND OBEDIENCE IN GIONA

Academy Journal Beta.1, 14-15 (2017) Printed in the United States

CC BY-NC-ND

Rev. Kevin K. Wright

The story of the prophet Jonah, as told through his eponymous book, stands as one of the most fantastical mythologies in the Hebrew and Christian scriptures. Set during the reign of the Jewish King Jereboam II (786-746 BC), Jonah’s story subverts the idea that “what goes around come around” and supplants it with the hope that God’s love and compassion are readily available to those who earnestly seek the path of repentance and obedience.

The Book of Jonah was most likely written sometime between the late 5th and early 4th century BCE during a period in which the Jews were led into exile by the brutal Babylonian Empire. This period of exile gave birth to a proliferation of Hebrew writing as Jewish communities sought to secure their history and heritage while they struggled to survive in a strange and foreign land.

The story of Jonah commences with God commanding the prophet to proceed to Nineveh (located on the outskirts of modern-day Mosul in Iraq) in order to exhort the people there to repent of their wicked ways. Jonah does the complete opposite, however, and secures passage on a boat sailing in the opposite direction as a means of escaping his emissarial assignment. God unleashes a storm to harass the boat, and Jonah, realizing that his disobedience is jeopardizing the lives of those around him, insists on being tossed overboard. The sailors fling Jonah into the sea where he is swallowed by a giant fish. Jonah spends three nights in the stomach of the fish where he repents for his disobedience. God hears Jonah’s remorse and commands the fish to spit him up on the shore so that he can carry out his mission. Once on land, Jonah goes to Nineveh where the people repent of their wickedness and are spared God’s wrath.

The irony of Jonah’s story is that it is his disobedience to God that marries his situation to that of the people of Nineveh. The personified character of Hope in Giona pleads with the people of Nineveh to realize that “Eyes full of tears move to compassion the angered Heaven.” Hope echoes this cadence again to Jonah where it says “Console yourself, oh heart of a sinful man: the penalty of Heaven is not as severe.” In the face of certain destruction, it is only hope that stands before God pleading for the fate of both the prophet and the city.

If Hope is the advocate for the haughty, then it is Obedience who instructs them on how to curry favor with the Almighty. Amidst Jonah’s reluctance to go to Nineveh it is Obedience who tells the prophet that “It is not for man to interpret the law laid down by Him who recreated the soul, who holds and sustains them.” After Jonah’s decision to abscond from his duty lands him in the belly of a fish, Obedience and Hope comfort the disheartened prophet by saying, “The Heavens are not harsh and deaf to the supplications of humility.” Obedience advocates for the choosing of God over one’s self and helps individuals to navigate the rocky shoals of their own ego and pride. In tandem effort, Hope and Obedience provide gracious guidance to those seeking the favor and blessing of God.

Contemporary audiences might need to hear Hope’s voice in the midst of our contentious national climate. Hope pleads with each of us to strive for goodness and gracious acceptance of the other while believing in our individual and corporate ability to act with justice and kindness. We might also welcome Obedience in our lives as well as we strive to weld our actions to patterns of love shaped by an adherence to Hope’s dream for us all. Each of us faces the choice between allowing our lives to be shaped by love or allowing our existence to be overrun by selfishness and fear. Hope and Obedience beckon us to the former. Like Jonah, we are fortunate to have such noble advocates on our behalf. Rev. Kevin K. Wright is an ordained United Methodist elder and the Minister of Education at The Riverside Church in the City of New York.

0 notes

Text

JONAH IN ART: CHANGING PERSPECTIVES

Academy Journal Beta.1, 7-13 (2017) Printed in the United States

CC BY-NC-ND license

By Dr. Ann Plogsterth

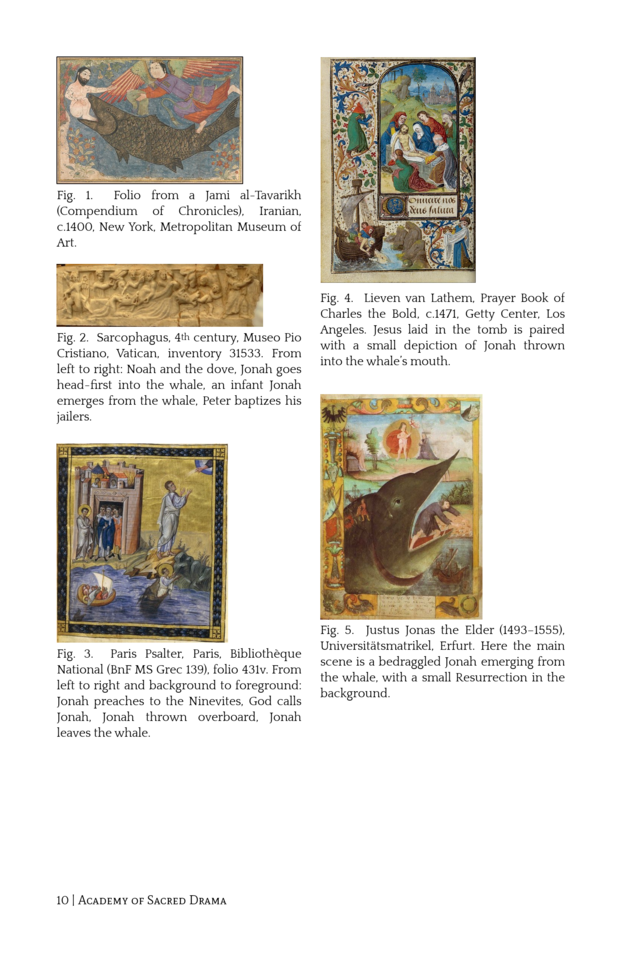

Over time, Jonah has inspired varied religious and artistic interpretations, focusing on different aspects of the complex tale. It is even found in the Quran (37:139) and in Near Eastern art (fig. 1). Only the first part of Jonah’s story is covered in our oratorio, and it focuses on the theme of the prophet’s disobedience.

The first Christians were, of course, Jews, well versed in the Hebrew Scriptures. They knew the book of Jonah, unique among the prophetic books in that it is entirely narrative and contains no real oracle. They also knew the tradition that would later become the New Testament. Both Matthew (12:40–41; 16:4) and Luke (11:29–32) speak of the sign of Jonah, whose three days and three nights in the belly of the whale1 were seen as prefiguring Jesus’s three days in the abode of the dead and his ultimate Resurrection; this connection is explicitly spelled out in the first Matthean passage.

So it should be no surprise that Early Christian sarcophagi and catacomb frescoes are especially fond of Jonah’s story, perhaps adding allusions to baptism, the gateway to resurrection—allusions which would have been apparent only to initiates. Jonah often emerges from the fish naked and bald, with a baby face (as if newly reborn) and in an orant pose, and the scene of him resting under the gourd tree (an incident not included in the oratorio) reflects the blessed soul of the baptized and resurrected Christian.2 In some fourth-century sarcophagi (fig. 2), Jonah under the tree is juxtaposed with a scene of Peter baptizing his jailers: first, baptism in this life, then paradise in the next.

In the sixth to eleventh centuries, Byzantine manuscripts expanded the narrative cycle to include further events: Jonah’s calling, his embarkation, and his preaching at Nineveh (fig. 3). These exquisite works influenced Jonah’s depiction in icons through subsequent centuries.

In the Middle Ages, the connection with Jesus’s Resurrection remains (figs. 4, 5), as do the narrative scenes, but, apart from these, Jonah also appears among group depictions of the prophets. In psalters and books of hours, Jonah and his whale were sometimes placed with Psalm 68/69,3 with its references to rising waters. An Ordo for commending a soul at the time of death prayed, “Sicut liberasti Jonam de ventre ceti, eicias me de morte ad vitam” (As you freed Jonah from the whale’s belly, may you cast me from death into life).4 One curious use of the Jonah theme is on South Italian ambos and preacher’s chairs, where it might be seen as a warning to reluctant preachers: Jonah’s disinclination to address the Ninevites did not work out well for him.

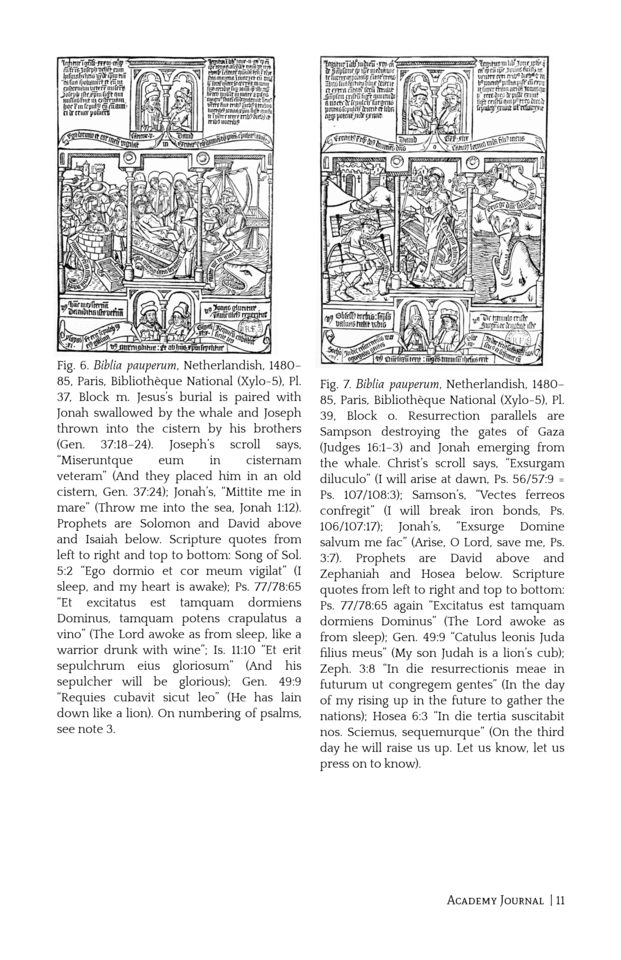

An important new medieval use of the Jonah theme is found in manuscripts and printed books like the Biblia pauperum and Speculum humanae salvationis. Both were collections of New Testament events joined to their Hebrew prototypes, with suitable quotations from the prophets, often in the vernacular (figs. 6, 7). For instance, Jesus’s burial is paired with Jonah swallowed by the whale and Joseph thrown into the cistern; the Resurrection parallels are Sampson destroying the gates of Gaza (as Christ burst the gates of death) and Jonah emerging from the whale.

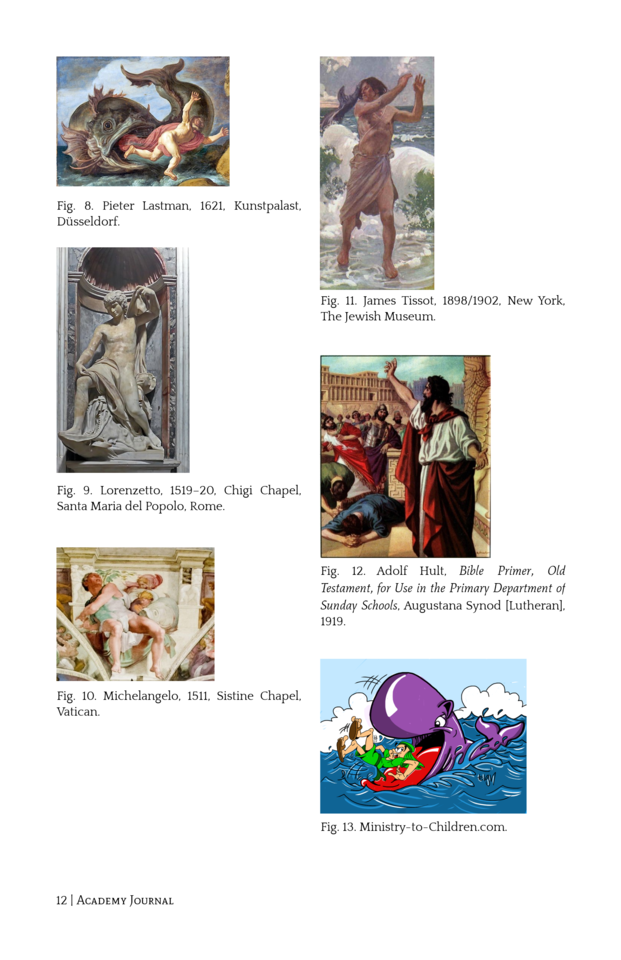

In the Renaissance and Baroque, both narrative cycles and allegorical allusions disappear, and we find more or less realistic depictions of a large fish and a man (fig. 8). Although Jonah is usually shown elderly, befitting a prophet, Lorenzetto portrayed an Apollo-like young Jonah (fig. 9); writing of this work, Vasari noted its allusion to the resurrection of the dead, a symbolism still remembered then. Michelangelo’s massive Jonah in the Sistine Chapel makes, by its placement, a connection between Jonah and the Christ of the Last Judgment (fig. 10), again perhaps reiterating the Resurrection theme.

By the time of our oratorio, the Biblia pauperum was hardly current reading and the scholastic mindset that searched for typologies was no longer prevalent, although probably remaining as a subconscious influence.5 Giona ignores the traditional connections with resurrection and baptism, focusing entirely on the motif of Jonah’s disobedience and subsequent obedience, a theme much harder to depict visually.

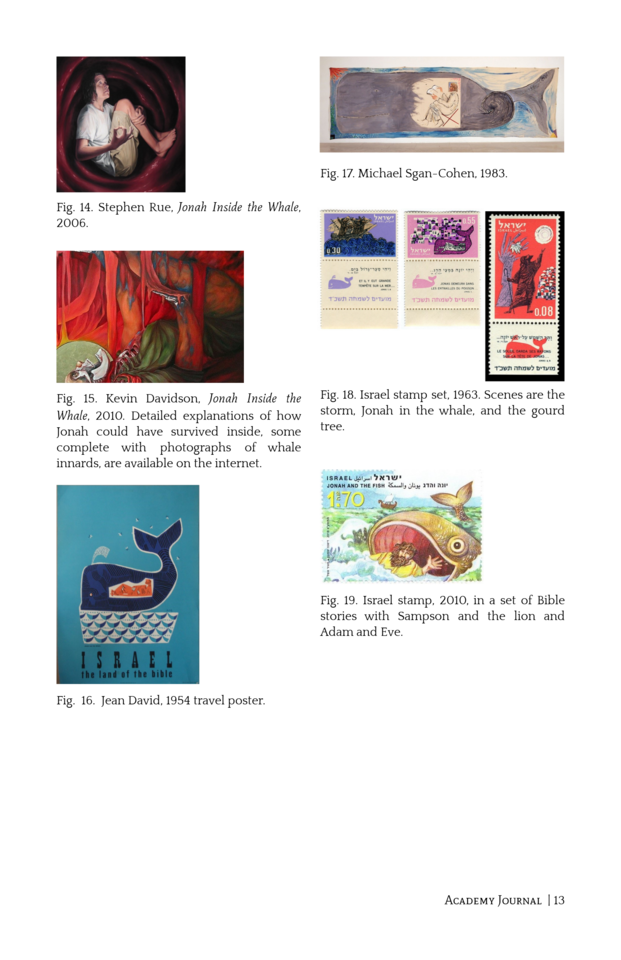

By the nineteenth century, all connections beyond the details of the actual story seem to have been lost, and we are left with a simple adventure story. Perhaps the most significant artist to depict Jonah then was James Tissot in his massive series of watercolors on the Bible (fig. 11). Eventually, the theme is taken over by Sunday-school illustrations (fig. 12), which can come to rival very bad cartoons (fig. 13). Sometimes the depiction reflects a hyper-literal interpretation of Scripture (figs. 14, 15). In Israel Jonah has generally received more serious artistic treatment (figs. 16–18), though, even there, one finds exceptions (fig. 19). Perhaps humanity can no longer deal with miracles or with metaphor; in this modern age we cannot see past the details of whale anatomy to perceive the prophet’s underlying message.

Dr. Ann Plogsterth has a doctorate in art history from Columbia University and a lifelong obsession with religious iconography.

_______________ 1. Actually “great fish” in Hebrew, and variously depicted as fish, seahorse, or sea monster. 2. The Vatican’s famous Jonah Sarcophagus pairs the prophet’s story with several scenes suggesting the saving waters of baptism (Noah in his ark receiving the returning dove [cf. 1 Peter 3:20–21], Moses striking water at Massah and Meribah) and the resurrection of the dead (raising of Lazarus).

3. The Hebrew and Greek Bibles number the psalms differently. Jews, Protestants, academics, and modern Catholics use the Hebrew system; Orthodox and traditional Catholics follow the Greek Septuagint. 4. Louis Réau, Iconographie de l’art chrérien, 1955, Vol. 2, Part 1, p. 415.

5. The connection of Jonah to the Resurrection persists in odd places: a gravestone c.2013 in the Ratzeburg cathedral cemetery depicts Jonah and the whale, and a 2014 Good Friday procession in Malta includes Jonah and his maritime companion.

#academy journal#academy of sacred drama#art#art history#jonah#volume beta#number 1#ann plogsterth#religion

0 notes

Photo

0 notes

Photo

0 notes

Photo

#ann plogsterth#academy journal#academy of sacred drama#figures#cartoon#jonah#volume beta#number 1#religion

0 notes

Photo

#ann plogsterth#academy journal#academy of sacred drama#figures#volume beta#jonah#stamps#paintings#art#religion

0 notes

Text

WHAT ARE THE JEWISH PERSPECTIVES ON THE BOOK OF JONAH?

Academy Journal Beta.1, 4-6 (2017) Printed in the United States Reprinted with permission from Asknoah.org

By Dr. Michael Schulman

The Book of Jonah is read during the services of Yom Kippur, the Jews’ Day of Atonement, because its messages are a fitting inspiration for that time. To understand this scripture, it helps to know the identities of Jonah and the king of Nineveh.

According to the Talmud, Jonah was the boy who was resurrected by Elijah (I Kings 17). He grew up as a prophet and a disciple of Elisha. He is the disciple whom Elisha sent to anoint and prophesy to Yehu (II Kings 9:1-10), and he prophesied to King Jeroboam II (ibid. 14:25). By the time of his prophecy to Nineveh, he was about 100 years old.

A prophet is liable to death by the Hand of Heaven if he suppresses a prophecy that G-d instructs him to deliver (Tractate Sanhedrin 89a). Why did Jonah do this? He recoiled from being the one through whom a criticism would be brought against his fellow Israelites. The Israelites included ten northern tribes that had separated from Judah and Benjamin, and formed the Biblical nation of Israel. They had then been drawn into idolatry, and although G-d sent prophets to warn them, they had not repented. Jonah knew that if he prophesied to the Gentile city of Nineveh, they would fear G-d, repent to Him and be forgiven. Then G-d would turn to the Israelites and say: “The Gentiles of Nineveh heard My warning from a true prophet and repented, so I forgave their sin. I sent many prophets to you, My nation, but you still refuse to abandon idolatry. Now everyone will know that I am justified in sending the Ten Tribes into exile as their atonement, until the End of Days when I will bring them back” (see Deut. 30).

To compel Jonah to obey, G-d first caused him to be willingly cast overboard, thus proving his merit that he cared more for his fellow Israelites than for his own life. Then G-d caused him to be saved by the giant fish that was created for that purpose during the Six Days of Creation (Midrash, Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer 10). The Midrash (ibid.) relates that the fish brought Jonah to view the Leviathan (Job 41). G-d will kill the Leviathan when the Messiah son of David comes, speedily in our days, and its meat will be served at the great celebratory feast that G-d will make for the righteous to welcome in the Messianic Era (Tractate Bava Basra 75a). At that time, G-d will remove everyone’s evil inclination, and Jews and Gentiles will dedicate themselves to serving G-d in unity and peace, as it says (Zephaniah 3:9): “For then I [G-d] will turn the peoples to pure language, so that all will call upon the Name of G-d to serve Him with one purpose.” We can see that G-d reminded Jonah about the universal destiny for mankind by bringing him to view the Leviathan.

But how was Jonah sure that the people of Nineveh would repent? As he said to G-d after they were spared (4:2), “Was this not my contention…? For this reason I hastened to flee…” The answer lies in the identity of the king. Jewish tradition teaches that he had been the Pharaoh whom we read about in the Book of Exodus (Midrash, ibid. 43). As the exodus took place, Pharaoh stood looking over the Red Sea while it split. When his army was drowned, he finally admitted to G-d’s complete control of the world and repented for his sins. He left and went to Nineveh, where he became king and dedicated it as a “great city unto G-d” (3:3). He was then blessed with long life, but eventually he lapsed and allowed his subjects to sin. Jonah knew that Pharaoh, of all people, would head G-d’s warning and lead them in repenting.

Jews have more commandments than Gentiles and are held to higher standards. Gentiles are accountable for the 7 Universal Commandments in the Book of Genesis, which are the foundation of true morality: establishing just courts, and the prohibitions against idolatry, blasphemy, homicide, forbidden sexual relations, theft, and eating meat that was severed from a living animal (cruelty to animals). But an entire population of Gentiles is not liable to collective Divine punishment unless they breach the boundaries of civilized coexistence, like the generations of the Flood and the Tower of Babel, and the metropolis around Sodom. In Nineveh, the rampant crime was theft (3:8). When Pharaoh heard that a prophet of G-d had declared that Nineveh would be overturned (3:4), he led the people in repentance to G-d. Since theft can’t be fully atoned without making restitution to the victims, they returned all stolen items and even tore apart their houses to return the materials they had extorted (Tractate Taanit 16a). Thus it says (3:10), “G-d saw their deeds, that they repented from their evil way,” instead of “G-d saw their sackcloth and fasting.”

After Jonah saw that Nineveh was not destroyed, he was sickened over the comparison with the unrepentant Israelites. To admonish Jonah, G-d provided for him a kikayon plant, which he cherished. The next day it died, which broke Jonah’s heart. G-d then told him, how much more so does He care for all people. For He invests all people with His image (Gen. 1:27), watching them constantly and waiting for them to repent to Him for their sins so they can be forgiven, as proven by the people of Nineveh. There were thousands of prophets in the Biblical Holy Land, but the only prophecies that were canonized in the Hebrew Bible were those which are relevant for all time, as G-d says (Malachi 3:6), “For I, G-d, have not changed…” The Book of Jonah teaches that all people, on account of G-d’s attention and care for them, are obligated to pray to Him to fulfill their needs – including prayers of repentance for their sins, combined with a commitment to actively improve their ways.

The author is grateful to Kate Bresee for the editing and useful comments that she provided.

Dr. Michael Schulman (PhD Physics '88) is an Orthodox/Hassidic Jew who has served since 1999 as Executive Director of the charitable organization Ask Noah International, and its web site Asknoah.org, from which this essay is reprinted with permission. A.N.I. is overseen by leading Orthodox Rabbis in the mission to provide education and guidance to Gentiles in the parts of the Written and Oral Torah tradition that apply universally to all people. Dr. Schulman is co-author of the book Seven Gates of Righteous Knowledge: Spiritual Knowledge and Faith for All Righteous Gentiles.

The content of this article is the property of Ask Noah International and does not carry the same CC BY-NC-ND license as the rest of the magazine.

#academy journal#academy of sacred drama#michael schulman#jewish perspectives#religion#orthodox/hassidic

0 notes

Text

LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER

Academy Journal Beta.1, 2-3 (2017) Printed in the United States

CC BY-NC-ND license

By Jeremy Rhizor

I am very pleased to present the first issue of the Academy Journal. It is a major step in the direction of building a community of thought around the music and stories of oratorios. Over the past year and a half, the Academy of Sacred Drama produced Oratorio Readings of five rarely-heard Baroque-era oratorios with the help of 67 volunteers in order to begin to build this community. These were paired with potluck dinners and experiments from a social game built on the story of Susanna to reflections on excerpts from Ishmael. As the Academy community continued to grow, I revisited some of my original goals for the organization including talks by guest speakers and a publication. I originally intended to include talks on contextually related material in place of the sermons that were placed between the halves of many Baroque-era oratorios. The North American Premiere of Giovanni Battista Bassani’s Jonah (Giona) marks a return to this model with a talk by Dr. Eric Bianchi on the intellectual and cultural context for Baroque-era oratorio.

The performance of Bassani’s Jonah also launches our Amateur Performance Initiative, in which gifted amateurs have the opportunity to participate in the performance of selected movements of the oratorio. An amateur viola da gamba player will participate in select movements of the first half of the Jonah performance. This is one of five new programs that the Academy now offers its members. Our goal with our membership programs is to unite the abilities and skills of professionals and amateurs of various fields in an effort to shed some light on the largely unexplored world of Baroque-era oratorio. The launch of the Academy Journal is the most visible element of the Academy’s renewal and expansion. It is designed to be a central resource for the world of sacred dramatic music.

In order to start to fulfill that function, we are offering a calendar of oratorios and reviews of performances of note. In this issue, Christopher Browner reviews the Modern Day World Premiere of Bonaventura Aliotti’s Santa Rosalia that occurred at Trinity Church, Manhattan on June 1st. The reconstruction and rediscovery of forgotten oratorios is a central component of our mission, and we are excited that New York Baroque Incorporated undertook this project. The second essential part of the Academy Journal is the exploration of the story and themes of Academy Oratorio Readings with articles by members of the extended Academy community. In this inaugural issue, Dr. Michael Shulman explores Jewish perspectives on the Jonah story, and Rev. Kevin Wright approaches themes of hope and obedience in the Jonah story through Christian perspectives. Dr. Ann Plogsterth also offers a narrative on the changing emphasis of visual artists as they sought to depict the Jonah story.

And finally, an exploration of this type would not be possible without a clear and intelligently crafted English translation of the original Italian text which until a couple months ago was unavailable. Dr. Elisabeth Pace created the first English translation of the libretto by Ambrosio Ambrossini which was the basis for Bassani's oratorio. She made it possible for us to undertake this communal and in-depth exploration of Bassani’s Jonah.

We call this first issue of the Academy Journal Volume Beta. It is an experiment in which we are trying out a new Academy Journal website, creating the fresh design of a new printed journal, and going through a new editorial process with our gifted editor, Kate Brecee. The Academy Journal will continue to grow and be refined from this point. Be we are excited about its launch and are happy to finally be able to share the fruit of much labor. We hope you enjoy it.

With gratitude to you for being part of our community, Sincerely yours, Jeremy

#academy journal#letters#letter#jeremy rhizor#volume beta#kate brecee#elisabeth pace#michael schulman#ann plogsterth#kevin wright#jonah#giona#oratorio reading june 10 2017#CC BY-NC-ND license

0 notes

Photo

#cover#academy journal#jonah#volume beta#number 1#academy of sacred drama#hope#obedience#whale#fish#CC BY-NC-ND license

0 notes

Video

youtube

0 notes

Link

Dr. Elisabeth Pace created the first English translation of Ambrosio Ambrossini’s Itialian libretto for the Academy of Sacred Drama. The performance of 10 June 2017 will be the North American Premiere of Giovanni Battista Bassani’s oratorio Jonah (Giona).

#Dr. Elisabeth Pace#Elisabeth Pace#Ambrosio Ambrossini#Ambrossini#Giovanni Battista Bassani#Bassani#oratorio#libretto#academy of sacred drama#academy journal#translation#translations

0 notes