Text

“God Planning Your Pain to Make a Point” (John 9:1-3) [A Guest Card Talk]

“God Planning Your Pain to Make a Point” (John 9:1-3)

A Guest Card Talk by Matthew E. Henry*

It’s What You See

As [Jesus] walked along, he saw a man blind from birth. His disciples asked him, “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” Jesus answered, “Neither this man nor his parents sinned; he was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him. … When he had said this, he spat on the ground and made mud with the saliva and spread the mud on the man’s eyes, saying to him, “Go, wash in the pool of Siloam”…Then he went and washed and came back able to see. (From The Gospel According to John 9:1-7, NRSV)

As a poet and educator, a quote from Henry David Thoreau is often on my mind: it’s not what you look at that matters, but what you see. There’s a lot in John chapter 9 to be seen, and it would be easy to focus on all of the blindness, the lack of sight in this story:

The man at the center of the story is literally blind. (vs 1)

The disciples’ lack of understanding and metaphoric blindness before the healing takes place. (vs 2-7)

How, after sight is granted to the formerly blind man, the Pharisees and the crowd display a lack of belief (spiritual blindness) by questioning if the man was even really blind to begin with, and then driving his whole family out of their religious community for their dealings with Jesus. (vs 8-41)

All of these elements are fair game, clearly build upon each other, and are a part of the central point of the passage. It’s also what I was taught as a kid in Sunday School. But this was never the first thing I saw. I was always deeply bothered by this flannel graph favorite, but it took me years to understand what was staring me right in the face: the blindness of Jesus.

maybe Jesus needed more time to think

the disciples asked Him whose sin blinded

this man from birth: his, his parents? appalled,

Martha cannot believe in this Jesus

whose deaf answer trembles her Bible closed.

so that you could see the power of God?

she remembers the eyes which accused her

of lapses in prenatal care. questioned

her fidelity. found lawful cause for

his tiny body’s chronic rebellion

against its own good. as the pastor reads

His response, she finds their false blame better—

more acceptable—than sons suffering

for parlor tricks, divine object lessons.

~ MEH

What Do We Deserve?

From the outset, this story is a theological and emotional rollercoaster. Jesus sees a man who is blind, and since this is Jesus, we assume a healing is forthcoming. But before He can open His mouth, His disciples ask a provocative question:

“Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” (vs2)

The disciples see someone in pain and ask a question accusing the man and his family of being so sinful that he deserves his aliment. The implication is plain: natural pain, illness, or sickness is the result of sin. We get what we deserve, which may include bearing the burden of our parents’ sin.

Look, I’m a high school teacher. I have no problem with basic “cause and effect” logic when it comes to consequences. You didn’t do your homework or study, so you failed the test. You tipped back in your chair, so you fell over. You said something racist/sexist/homophobic to the wrong person on the right day, so now you walk with a limp. Speeding can cause an accident. Unprotected sex can result in an STD. Uncritical voting practices can, ironically, lead to the downfall of democracy. These are outcomes easy to understand. But most of us will balk at the idea that we “deserve” an effect that is not a direct result of something we ourselves caused.

To some degree we can begrudgingly accept the reality that the decisions that others make, especially our parents, can have a negative impact on us. Ask the family, significant other, coworker, or employee of abusers, alcoholics, emotional manipulators, gamblers, or any other shitty people. We can all be hurt by the actions of others, but to say we “deserve” that hurt is unhealthy. [Pause: if you don’t think this is true, you are probably in an abusive situation, as your friends have been telling you for years. Listen to them. Get out.]

The beginnings of Jesus’ responses bears out the truth of this:

Jesus answered, “Neither this man nor his parents sinned… (vs 3a)

YES, Jesus! Smack down their highly problematic theological assertion—their backward hamartiology imputing sin on the innocent. This is where the story should: Jesus drops this knowledge, heals the man who is blind, and they all go out to throw loan sharks out of the Temple. But the problem is that Jesus keeps (f**king) talking…

“…he was born blind so that God’s works might be revealed in him.” (vs 3b)

Seriously Jesus: WTF?

Let’s really stop and unpack this.

In answering thier question, Jesus says that this man’s decades of blindness was preordained by God—presumably before the foundations of the earth were lain—as a “parlor trick” or “divine object lesson” for the benefit of the disciples (and presumably everyone else who would come in contact with the healed man, whether in person, or reading his story in the Christian New Testament). Yes. The number of people impacted by this miraculous event is an amazing witness. And no doubt the formerly blind man was very grateful for his healing (you know, save for the whole having his life of pain questioned and his family run out of town thing, which undoubtedly sucked). But, again, let’s really look at what this means.

Let’s propose a new scenario: a mother has a child with a serious physical or cognitive limitation which significantly harms the child’s quality of life. She hears this story being preached by her pastor/priest from the pulpit one Sunday morning. What would she take away from this tale?

It’s one thing to believe an almighty God is doing the Divine’s Best to redeem all our free will actions—that “all things working together for good” (Romans 8:28) means that God is exerting effort in the face of the causes and effects that lead to our pain. Call it “natural evil,” or “a result of The Fall,” or “nature red in tooth an claw,” or “shit happens,” this mother, like many of us, can begrudgingly accept this idea when it comes to “why bad things happen.”

But it is another thing entirely to ask this woman if she is comfortable serving a God who believes that the ends justify the means. Asking her to accept a utilitarian model of theodicy—achieving “the most good for the most people” means that some people have to suffer by divine design. What could she take away other than false hope or anger at the prospect that maybe, hopefully, there is “some good reason” that God has for directly causing her child pain?

That might be a shit-filled pill too large to swallow.

It Gets Worse

I am not the only person who thinks this. Other characters in the Bible do as well. If we continue reading The Gospel According to John, a couple of chapters later we come to a story about Lazarus—a close friend of Jesus—whose situation is placed in relation to this story about the man who was formerly blind.

In John chapter 11, when Lazarus get very very ill, his sisters—Mary and Martha—send word to Jesus that His beloved friend is close to death. Upon hearing this news, Jesus responds, “This illness does not lead to death; rather, it is for God’s glory, so that the Son of God may be glorified through it” (vs 4b) [sound familiar?]. He then hangs out for another two days until he receives word that Lazarus has died. Eventually, Jesus makes the trip to see Lazarus’ body, which has now been in the tomb for four whole days. But, just like with the blind man, Jesus is unfazed because He had a plan, knew what He was doing all along. Yes, healings are great, but by now you should see the pattern and the problem.

If Jesus could heal him, why should Lazarus have to suffer like this—his body wracked with pain, alternating between fever and chills, gasping for each labored breath? And what about the people who love Lazarus and must watch him suffer? They attempted to cool his body, relieve his pain, force him to eat something, tell him everything is going to be alright when they didn’t believe it themselves. Being so concerned for the welfare of their brother, for the first and only time recorded, Mary and Martha try to cash in on their long-standing friendship with Jesus, desperately believing that He had the power to save him (See 21-27; 32).

But it’s not only Lazarus’ family who feels this way, but the friends gathered around who knew the power of Jesus. So much so they reference his previous encounter with the formerly blind man:

Jesus began to weep. So the Jews said, “See how he loved him!”

But some of them said, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?” (vs 35-37)

Again, yes, to exist on this planet means we will suffer in various ways, including our bodies rebelling against us and those we love. Ugly and painful deaths are also built into the system. Thus, the fact that Jesus heals anyone in the Bible is wonderful. But don’t miss the rationale given for the illness, for the death. Don’t be blind to the Bible’s own words. Jesus said Lazarus was sick “…for God’s glory, so that the Son of God may be glorified through it” (vs 4b). God becomes the cause of this effect and it forces one, or at least me to, respectfully, call theological bullshit.

An Uncomfortable Way of Seeing

As I’ve grown older, my Sunday school discomfort has been tempered by my life as a writer and educator. It’s led me to wonder if these self-referential stories have fallen prey to a common literary issue: the narrative plot hole.

Sometimes an author is so wrapped up in the point that they are trying to make that they don’t think through the implications of all the details; They are so focused on the big picture, the major theme and motifs running through a work, the finer point get lost. It’s the same reason why medical shows are eviscerated by doctors, sci-fi movies by physicists, and police procedurals by civil rights lawyers. Some would call this a blasphemous thought. I recommend those people to not read any of the other posts on this website. But I think this way of seeing is better than the alternative.

I won’t dive into the depth of what this way of seeing requires in terms of “the inerrancy of Scripture,” “divine inspiration of Scripture,” and the variety of other hermeneutical concerns some would raise. I am aware of them, but if you’re bothered by this, you’ll probably hate my answers for those. But I will provide one for the Bible nerds: this view of Jesus/God in the Gospels is singular to John. What do I mean? This idea that physical ailments are a result of sin or God’s divine plans in this particular way, only shows up in The Gospel According to John. It is not present in in the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, or Luke).

Neither the Lazarus story in chapter 11 or our principle story in chapter 9 are found in the other gospels. In Mark 8:22-26 there is a blind man being healed story that is similar to the John narrative, but among the many differences there is no mention of sinfulness or the idea that God plans such pain for people. Going for the trifecta, John provides a third story that suggests that disability is tied to sin.

In John 5:1-18, Jesus comes across a man who is paraplegic. Jesus heals the man before going on His merry way, but it’s the aftermath that we see this uniquely Johannine theology of suffering:

Now the man who had been healed did not know who it was, for Jesus had disappeared into the crowd that was there. Later Jesus found him in the temple and said to him, “See, you have been made well! Do not sin any more, so that nothing worse happens to you.” (vs 13-14)

Again, this story is not contained in the other three gospels. Make of that what you will, but it seems pretty clear the writer(s) of John had a way of looking at things that was not shared by the other gospel writers. Maybe three out of four gospels agree that the idea that physical suffering being a part of the divine plan is simply a wrongheaded idea. I guess you get to decide who you agree with.

But, to paraphrase this game’s creators, what do I know? I’m just a poet and you probably think I’m going to Hell.

* Dr. Matthew E. Henry (MEH) is the Boston-born educator, editor, and author of six books of poetry, including The Third Renunciation (New York Quarterly Books, 2023). The Third Renunciation is a collection of theological sonnets, wherein the poem featured above is published.

He was also the editor of A Game for Good Christian’s This Present Former Glory: An Anthology of Honest Spiritual Literature

Dr. Henry received his MFA in poetry from Seattle Pacific University, yet continued to spend money he didn’t have completing a MA in theology (Andover Newton Theological School) and a PhD in education (Lesley University). But he should not be confused with the long dead, white, theologian. His work can be found at www.MEHPoeting.com and on Twitter (he will never call it X) at @MEHPoeting.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Legion of Demons (Mark 5:9)

Starting at the End

We’re coming at this Card Talk from a different angle than most. Consider this more midrash, than exegesis. A “what if?” more than “this is what happened.” So we’ll start with an unusual proposition: What if it was the man questioning Jesus, not the demons?

The Man, The Demons, The Pigs

Here’s the story in Mark 5:1-20: Jesus and His disciples cross the water into the region of Gerasenes. The second His feet touch the shore, Jesus was verbally accosted by a man with “an unclean spirit,” a demon, whose situation was dire.

He lived among the tombs, and no one could restrain him any more, even with a chain, for he had often been restrained with shackles and chains, but the chains he wrenched apart, and the shackles he broke in pieces, and no one had the strength to subdue him. Night and day among the tombs and on the mountains he was always howling and bruising himself with stones. (Mark 5:3-5)

When the man saw Jesus, he ran, threw himself at Jesus’ feet, and screamed, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by God, do not torment me” (vs 7). So Jesus gets into a shouting match with the demon (which He wins), and He tells the demon he’s about to be exorcised from the man. But being a nice exorcist, Jesus asks the demon its name and learns that it is not one demon, but a whole bunch of them when it/they replied, “My name is Legion, for we are many” (vs 9). The demon(s) beg not to be sent too far away because they like the region (they’ve put down roots, it’s on the beach) and asks to be sent into a herd of pigs nearby. Jesus, again being a nice exorcist, says sure and sends the legion of demons into the assembled pigs.

So he gave them permission. And the unclean spirits came out and entered the swine, and the herd, numbering about two thousand, stampeded down the steep bank into the sea and were drowned in the sea. (vs 13)

Needless to say, this pissed off the owners of the pigs, who ran into town and told everyone in earshot what happened, eventually demanding that Jesus get the hell out of the region (exorcism pun!). In the meantime, the formerly possessed man, now clothed and thinking clearly, asked Jesus if he could go with Him on His journey. Jesus tells him to go home to his family and his people, and “tell them how much the Lord has done for you and what mercy he has shown you” (vs.19), which of course he did to the amazement of everyone.

There’s the story. But let’s return to vs 7 and our initial question.

What if this is the man talking,

not Legion the demons?

Who’s Asking?

When he saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and bowed down before him, and he shouted at the top of his voice, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? I adjure you by God, do not torment me!” (Mark 5:6-7)

What are we suggesting? Simple: that it’s the man, not the demons, talking to Jesus in vs 7.

Yes, in vs 8-9 Jesus is talking to the demons and the demons answer in vs 9-12, but we’re asking, what if the initial question was from the man? He isn’t yet “sitting…clothed and in his right mind” (vs 15), but he is briefly lucid in that moment, perhaps because the demons were so scared at the approaching of Jesus. Why would we even propose this question? Re-read verses 3-5 above.

This was a man who had been regularly abused by those in his community who tried everything to cure, save, and help him, but now just try to keep him out of the way: bind him, hold him captive, so he is not a danger to others. He is used to being seen as “other,” as less than. And here comes Jesus. Another in a long line of supposed healers who will only cause him additional pain.

Sure. You think we’re heretics. That’s nothing new. But this reading is not outside the scope of the rest of the chapter. Consider the other pericopes in Mark chapter 5.

The Rest of the Stories

In the rest of chapter 5 of Mark, verses 21-43, Jesus crosses back across the waters and performs two more healings: He brings Jarius’ 12 year old daughter back from the dead, and heals a grown woman with the 12 year old bleeding problem. We won’t spend time with the parallelism (e.g. young and old women, the obvious use of 12 symbolizing the renewal and rebirth of Israel’s 12 tribes heralded by Jesus’ actions). Let’s look at this two women’s stories. Two people who could not find the healing that they needed from those in their community (sound familiar?).

No actions of the religious leaders or politicians saved them. The younger woman was on her death bed, indeed she died and had to be brought back to life by Jesus. For the older women, the text makes it clear that she spent 12 years being taken advantage of by doctors, to the point of her being poverty stricken, while her ailment only got worse.

In addition, she was “unclean” in the eyes of the people, removing her from right worship within the Temple worship [and we’ve written quite a bit about the misconceptions of “clean and unclean” as it relates to the Bible. Read about that here.].

Those in charge of physical, social, and spiritual healing could do nothing for either of these women.

Until Jesus shows up.

All three of these characters know what it is like to have a community think they know what is best and astonishingly fail.

They all have reason to doubt, to question whether healing is possible, whether they will be taken advantage of and hurt by the people who have known them the longest, to say nothing of this stranger.

Which brings to bear another element: the man with legion demons was a gentile, not a Jew (didn’t you wonder why there were so many pigs around? They ain’t kosher.). The man was used to taking it from those in his own community, he didn’t need any more pain from the outside.

Turn on the news and then walk into a church. Listen to things that have been shouted from the pulpit in recent days. Is it really so hard to believe that someone in their right mind might be skeptical of “good christians”?

Perhaps we should not be so quick as to wonder why those on the outside of the household of faith might not be flocking to us for aid or help.

Perhaps we just seem like another in a long line waiting to hurt them.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Being afraid to have sex in your tent, for fear of Phineas breaking in and stabbing you in the back with his spear (Numbers 25:6-8)

Not a Sexy Beginning

Numbers 25:1-15 tells the story of the children of Israel having sexual relationships with the people of Moab. This was a big no-no, because the Israelites were supposed to hate the Moabites (we explain why the Moabites are so hated in another Card Talk. That one is all about the sex.) Needless to say, God is upset by this, not (only) because of all the sex, but because of what the sex brought with it, which was worship of the Moabite gods. Thus, Israel yoked itself to the Baal of Peor who was really, really shitty—literally—and the Lord’s anger was kindled against Israel (vs 2-3).

God’s anger was made known to the people:

The Lord said to Moses, “Take all the chiefs of the people, and impale them in the sun before the Lord, in order that the fierce anger of the Lord may turn away from Israel.” And Moses said to the judges of Israel, “Each of you shall kill any of your people who have yoked themselves to the Baal of Peor.” (vs 4-5)

In addition to this death sentence, 24,000 die in a plague (c.f. Psalm 106:28-31).

But it gets better…well, worse…which is the subject of this card and Card Talk.

Just then one of the Israelites came and brought a Midianite woman into his family, in the sight of Moses and in the sight of the whole congregation of the Israelites, while they were weeping at the entrance of the tent of meeting.

When Phinehas, son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, saw it, he got up and left the congregation. Taking a spear in his hand, he went after the Israelite man into the tent, and pierced the two of them, the Israelite and the woman, through the belly. So the plague was stopped among the people of Israel. (vs 6-8)

Background on Backstabbing

We want to address three (3) points of contention in this passage:

1. Who she was

While it is noteworthy that the woman is a Midianite, not a Moabite, it is clear from the framing of the story that the Midianites are being associated with the evils of the Moabites. Regardless of the reason, Phineas is not having any of it. He takes a spear and stabby stabby stabby.

[For the Bible nerds: In Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic, Frank Moore Cross argues that this is an Aaronite priestly text praising and elevating Phineas—who is from Aaron’s line—, while (possibly) taking a shot at the Mushite priestly line, as Moses was married to a Midianite (201-203)].

2. Where they got stabbed.

As we’ve discussed before Biblical translators can be prudes. Thus, in most English translations, vs 8 say that the spear went through the man and then through the woman’s “belly,” “stomach,” or “abdomen.”

However, the good old, often very literal, Douay-Rheims translation renders קֹבָה a different way

…and thrust both of them through together, to wit, the man and the woman in the genital parts. And the scourge ceased from the children of Israel:

Following suit, renowned Hebrew Bible scholar Everett Fox translates קֹבָה as “private parts.” And if Phinehas was able to stab her through the vagina, that means he also pierced what was thrusting inside of it. In other words, Phinehas’ aim was crazy good. Through the back, through the penis, through the vagina.

3. Where they were having sex

The passage says (vs 6) that the man brought the woman before his family “in the sight” of everyone, while they “were weeping at the entrance of the tent of meeting.” The couple then went into “the tent.” Some argue that this means that the sexy couple walked by everyone in the Tabernacle, and then went and had sex in the man’s tent.

However, others argue that the mention of the man’s family, and the use of the phrase “in the sight of Moses and in the sight of the whole congregation of the Israelites” while they were at “the entrance of the tent of meeting,” means that the couple were publicly having sex in that tent. They didn’t go back to the man’s house, they were doing it in the Tabernacle itself, God’s house.

I wonder why people got so mad…?

The Rabbinic Perspective

Sifrei Bamidbar—the Midrash on Numbers— has quite a bit to say about this passage. Of particular note is the retelling of Phineas’ action itself. The Midrash reports that God performed twelve miracles once Phineas entered the tent with his spear.

In summary:

(1) an angel kept the bodies joined together, and

(2) sealed their mouths so they couldn’t scream.

(3) The spear joined them directly at the genitals, so none of the skeptics could doubt what they were doing, which was made easier because

(4) they did not slide off the spear, even when

(5) the angel lifted the spear so everyone could see. This upset people, so they attacked Phineas, but

(6) the angel fought them off until Phineas told the angel to calm down and the plague ceased.

After this (7) the spear, still holding the bodies, began to grow straight up in the air, but

(8) Phineas, who is now holding the spear again, is granted super-strength to support the load, which is good because

(9) the spear didn’t break. In addition, God protected Phineas from becoming ritually unclean (tame’) during all this because

(10) the blood of the couple did not fall on him, and

(11) the couple was still alive while all of this was happening.

In the end (12) the arrangement of the bodies and the scene itself convinced the people that this was all God’s will.

[Feel free to read the longer version here: Sifre Num 131]

This emphasis on the guresome and fantasitcal nature of their deaths, is not just to turn the text into a biblical snuff film. This midrash contains a lot of commentary on this background and implications of the Hebrews’ interactions with the Moabites.

It explains that this situation is just as terrible as the incident with the golden calf. It describes the people turning their backs on God: a gradual decline into moral (and physical) debauchery. They are selling their bodies and souls into the embrace of the enemy, slowly, but completely.

It reports Elazar b. Shamua as saying “Just as a nail cannot be removed from a door without wood (attached), so, an Israel cannot leave Peor without souls (i.e., without adhesions thereof).”

In other words, even when the people eventually come to their senses, the damage has been done, and there is no clear break with the evils of the past

Phineas’ actions should be seen in light of this.

God-making Sex

Though important, sexual purity is not the main focus of this passage. It isn’t even racial/ethnic identity that is at the center of this, though again, that was also very important. The point is spiritual allegiance to the One True God. And before you get too triggered by that sort of language, just remember, everyone has “a god” they serve. For some people, that is actually a deity.

In The End of Education, Neil Postman equate the word “god” with the word “narrative” in ways we find instructive:

“I use the word narrative as a synonym for “god,” with a small “g.” I know it is risky to do so, not only because the word “god,” having an aura of sacredness, is not to be used lightly, but also because it calls to mind a fixed figure or image. But it is the purpose of such figures or images to direct one’s mind to an idea and, more to my point, to a story. Not any kind of story but one that tells of origins and envisions a future; a story that constructs ideals, prescribes rules of conduct, provides a source of authority, and above all, gives a sense of continuity and purpose. A god, in the sense I am using the word, is the name of a great narrative, one that has sufficient credibility, complexity, and symbolic power so that it is possible to organize one’s life around it…[narrative is] a comprehensive narrative about what the world is like, how things got to be the way they are, and what lies ahead” (5-6).

Postman argues that when we are creating a narrative, we are creating meaning for our lives, we are “god-making” (7).

Phineas was responding to not only the plague, but the assault on the community’s concepts of authority, continuity, and purpose. Their “great narrative” was in danger, and he sought to defend it. The people were flagrantly creating a god he couldn’t abide. In this instance, that god-making, was synonymous with sex.

Putting aside, for one moment, the patriarchal ideas underpinning much of the discussion of sex and sexuality in the Bible, a case could be made that a significant portion of the time, the prohibitions against sex in the Bible are often focused on the outcome, namely the people of God being distracted, enticed, or drawn away from their first love, YHWH. Hence all the “unfaithful wife” imagery employed (c.f. Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Jesus, Paul). The idea that who you sleep with matters because of where those relationships might lead. Not kinky sex dungeons (not that there’s anything wrong with that), but places your heart/mind shouldn’t go. Just look at Samson or David and his sons—esp. Amnon and Solomon—as examples.

But let’s be clear: patriarchal ideas underpin the vast majority of the Bible’s take on sex and sexuality. And as we’ve covered in the past, we’re not saying that this is okay, but it should be taken into account.

Perhaps we should recognize that strange stories in the Bible tend to be a rehashing of the great commandments to “love God” and “love our neighbor.”

This one is no different.

Perhaps we should take more care to see how our actions impact our communities, especially when we are making a god out of things that are harmful.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Death by lion for not punching a prophet (1 Kings 20:35-36)

Note: This card was previously discussed by one of our guest bloggers. We wanted to nerd out about this card and do a deep dive from another perspective. This will include addressing why Card Talks like this one result in us having to read hate mail. Regardless, no prophets were killed in the making of this Card Talk (as far as you know).

Punch or Die

At the command of the Lord a certain member of a company of prophets said to another, “Strike me!” But the man refused to strike him. Then he said to him, “Because you have not obeyed the voice of the Lord, as soon as you have left me, a lion will kill you.” And when he had left him, a lion met him and killed him. (1 Kings 20:35-36)

This is all seems pretty straightforward. Prophet 1 (P1) tells prophet 2 (P2) to hit him. P2 says no and promptly gets attacked by a lion. However, the story continues.

P1 finds another prophet (P3) and makes the same request. P3, possibly knowing what happened to P2, acquiesced and beat the crap out of P1. But this is where things get interesting. Prophet 1 covered some of his wounds with bandages, and disguised himself as a solider coming back from the war that was raging in the area. He then waited for Ahab, the king of Israel, to come along the road. When king Ahab arrived, the prophet told him a story:

In the midst of the battle, an officer told him to guard a prisoner. If the prisoner escaped “the solider” would either be killed, or forced to pay a fine of a talent of silver, which is over 100 times the average cost of slave (c.f. Exodus 21:32). In other words, the fine was tantamount to a death sentence. As with all battles, crap happens and the prisoner escaped. “The solider” asks the king what he should do. King Ahab has no pity on “the solider” and says, “So shall your judgment be; you yourself have decided it” (vs 40) (i.e. “you’re screwed”). At this point, “the solider” drops his disguise and Ahab, recognizing him as a prophet, knows he’s in deep trouble. The prophet condemns king Ahab, saying, “Thus says the Lord, ‘Because you have let the man go whom I had devoted to destruction, therefore your life shall be for his life, and your people for his people’” (vs 42). King Ahab then returned home thoroughly shaken, waiting for the judgment of God to fall.

The end.

Okay, but none of that explains the deal with P2 and the lion attack. But yes, it really does. Ultimately, this is a story about two people “getting what they deserve” for not listening to the voice of God.

King Ahab Gets What He Deserves

A little background might help. Chapter 20 of 1 Kings tells the story of king Ben-Haddad of Aram waging war against the northern kingdom of Israel.

In (brief) summary:

(vs 1-6) Ben-Haddad gathers a huge army, besieges Samaria (the capital of Israel), and tells Ahab “your silver and gold are mine; your fairest wives and children also are mine.” To which Ahab responds, “cool.”

(vs 7-12) The elders/nobles of Israel, not okay with this arrangement, tell Ahab to grow a backbone. So he does, telling Ben-Haddad he politely declines. Ben-Hadad’s reply can be translated to mean either, “I swear by god, my army is so vast, that there will not be enough ground to stand on when we come to level this city!” OR “I swear by god, my army is so vast, that when we finish leveling this city, there will not be enough dust left to fill the hands of my men if they wanted to take home souvenirs!” (#TrashTalking). Ahab swings back with, “one who puts on armor should not brag like one who takes it off” (vs 11). In other words, “run your mouth after you win!” So Ben-Haddad, who is drunk when he gets this message, screams for his men to get into fighting position.

(vs 13-22) A prophet of God gives Ahab a battle strategy involving a lightly armored, special-forces unit. They attack in the middle of the day and catch Ben-Haddad off-guard because he’s still drunk. God leads the Israelites to victory, routing the superior force and their heavy weapons, and lifting the siege. They pursue Ben-Haddad, but he is able to escape. Though victorious, through the prophet, God warns of the another attack.

(vs 23-27) Sure enough, Ben-Haddad has a new battle plan: fight at a new location with more troops.

(vs 28-34) But God is ready for the forces of Aram and says, “wipe them out.” And they do. Mostly. Ben-Haddad gets away again and goes into hiding. His servants convince him to attempt to make a peace treaty. They contact Ahab for parley and make terms for a ceasefire. Ahab accepts. And that’s the problem.

God felt that Ben-Haddad was an evil to be eradicated, not an ally to make a treaty with.

This brings us back to the confrontation and the prophet’s words to king Ahab:

“Thus says the Lord, ‘Because you have let the man go whom I had devoted to destruction, therefore your life shall be for his life, and your people for his people.’” (vs 42)

Ahab went against God’s long-standing commandments about not working with his oppressors, and he is getting what he deserves.

And while we could spend time arguing about what to do with the Bible’s use of God-directed violence in this text (as we do with some others), the lesson of this passage is wrapped up in the biblical assertion that you do what God tells you to do: if God says, “kill them all,” you kill them all. It’s a lesson Ahab should have already learned from history. Ask King Saul: he pissed off God doing pretty much the exact same thing (1 Samuel 15).

What’s more, the prophet gave Ahab a scenario which exposed him as a hypocrite: he was condemning a man while not living up to the same standard. This is exactly what Nathan did to David in regards to his treatment of Bathsheba and Uriah. And is is also the same standard that Jesus holds us to, and says we should hold others to (regardless of how horribly He is misquoted).

And while all of this is well and good, you’re probably (still) asking, “but WTF does this have to do with the death by lion part?!”

Glad you asked. But first, you should know that the lion probably didn’t kill him.

Just messed him up a bit. Maybe a whole lot.

The Prophet (P2) Getting What He Deserved

Let’s start with the job of a prophet: one who presents the word/vision of God to the people. The prophet bears the weight of divine command and responsibility. So when one prophet gives another prophet a divine command, that second prophet knows the authority under which the first prophet is operating. Denying the words of the prophet is denying God.

(Read that again.)

In this story, P2 refused to heed the call of God. Just like Ahab refused his instructions. But, as with most things biblical, things get more interesting (and complicated) when we dive into the diction and definitions of the words employed.

Below we’ve parsed the Hebrew in the passage; notice the highlighted words. Hebrew readers: you’ll see where we are going pretty quickly. Non-Hebrew readers: be patient, we’ll explain.

At the command of the Lord a certain member of a company of prophets said to another, “Strike {נָכָה nakah - hiphil imperative} me!” But the man refused to strike {נָכָה nakah - hiphil infinitive} him.

Then he said to him, “Because you have not obeyed the voice of the Lord, as soon as you have left me, a lion will kill {נָכָה nakah - hiphil perfect} you.”

And when he had left him, a lion met him and killed {נָכָה nakah - hiphil imperfect} him.

Then he found another man and said, “Strike {נָכָה nakah - hiphil imperative} me!”

So the man hit {נָכָה nakah - hiphil imperfect} him, striking {נָכָה nakah - hiphil infinitive} and wounding him.

~ 1 Kings 20:35-37

In case you missed it, “strike,” “striking,””hit,” and “kill”are all the same word in this passage {נָכָה nakah}, but with different parsing of the verb (Non-Hebrew readers: think of all that “hiphil,” “imperative,” “infinitive” stuff as different ways to conjugate the verb).

The Hebrew word nakah means to “hit” or “strike,” but the hiphil imperative in vs 35 and 37 is referring to a very serious blow/attack. This could also be rendered, “beat the ever-living crap out of me!” Which makes sense: the prophet’s disguise only works if he looked like he got wreaked on the battlefield. So props to the prophet for being willing to take a beating for his mission.

This is a form of the prophetic “sign-act”— a physical parable, the action of the prophet is symbolic of a deeper truth. They are common in the Bible and include Jeremiah breaking pottery in front of religious leaders (Jeremiah 19:1–13), walking around wearing a yoke for oxen (Jeremiah 27–28), and offering wine to prohibitionists (Jeremiah 35:1–19), Isaiah walking around naked for three years (Isaiah 20:2), and Ezekiel cooking food over human excrement (Ezekiel 4:9-15).

However, this unnamed prophet was performing a “sign-act” with higher stakes. He will bear the marks of his commitment to God’s message in his very flesh. And maybe that’s part of the point: if he could take the beating, why can’t the other prophet give it? But don’t be too worried about the second prophet: like we said, chances are that he wasn’t killed by that lion.

Notice that in verse 36, the Hebrew for “slew him” is nakah again, however, this time it is the Hiphil perfect. Meaning, we was probably just mauled by the lion, not killed. Which, while not great, is certainly better. But also consider the balance of the image presented by a mauling: because he didn’t do God’s will, he was made to suffer the same injuries as the other prophet. He shared in the first prophet’s pain.

You Don’t Have to Like it to Understand the Message (or Keep your misinformed hate mail to yourself)

The Bible is an ancient text filled with stories that, on first (or second, or third) pass can seem very nasty, brutish, and short. But there is generally an underlying morality that makes perfect sense in an Ancient Near East context. Read that last part again: it fits into the ANE context.

Every once in a while we get hate mail, not because we said something blasphemous and some SOLIDER OF THE LORD has to point out our evil ways, but because someone who was burned by Christianity (or a Christian, or a “christian”) wants to rant about how the passage we’ve explained is proof positive that the God they don’t believe in is evil and not worthy of worship. Generally it’s because of Card Talks like this one, where we explain something that does not fit into our modern sensibilities. So we’ll say it again:

The Bible is an ancient text filled with stories that, on first (or second, or third) pass can seem very nasty, brutish, and short. But there is generally an underlying morality that makes perfect sense in an Ancient Near East context.

However, while this is true, there are often still lesson that can be applied to our lives today (otherwise, what the Hell are all those clergy people doing every week…other than ignoring passages like this one?).

Perhaps we should think about our own hypocrisy: the times we hold others to a standard we do not uphold ourselves.

Perhaps we should think about the ways we do not live up to the calling on our lives, not doing the things what we know we’ve been told to do. Perhaps the resulting consequences, the punishments, actually do fit the crime.

Perhaps we should think about what we are willing to do, the sacrifices we are willing to make, in order to bring the Word of God, a vision of God, to others, remembering that word, that vision, can be a blessing, a hug, a kind word, a song, an encouragement, or countless other positive, life-affirming realities we often makes excuses instead of bringing into the lives of others.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Altar Sex (Amos 2:8) [A Guest Card Talk]

Note: this Guest Card Talk is connected to our other card talk on the Book of Amos.

“The closest I ever came to having sex was right after prayer.”

For many young adults, this observation would serve as a catalyst for a more active prayer life, but for us pious young men at a Christian college, this advice from a graduating senior served as a warning. Intimacy is risky and dangerous and, if you’re not careful, you’ll end up in the wrong holy of holies.

Recent examinations of Christianity’s approach to sexuality have been rather damning with their criticism and deconstruction, from extensive exposes on various church-related sexual abuse scandals, to full-throated takedowns of “evangelical purity culture.” Even the patron saint of courtship, Joshua Harris, has kissed “kissing dating goodbye” goodbye.

But despite Christianity’s well-published and long-running anxiety about all things sex, historical records seem to indicate that few religious traditions are exempt from such tension. The sacred and the sexual may be uncomfortable bedfellows, but they sure can’t be accused of not trying. Long before Augustine began ruminating about the sinful superpowers of semen, fertility cults from Baal to Dionysus were planting their seeds in every known religion. Even texts found within the Hebrew Scriptures - such as Song of Songs - have been known to arouse more than pious hearts.

Which brings us to Amos, the lonely shepherd of Tekoa. In Amos 6:1-7, the prophet makes explicit reference to a marzeah, a cultic ritual attested to widely throughout the Fertile Crescent and beyond. While the origins of the term remain a mystery, widespread attestation across cultures paints a rather consistent picture of marzeahs as cultic festivals that centered on feasting and drinking, sexual lasciviousness, and were often connected to funerary rites. Sort of like an ancient Mardi Gras.

The word itself only appears twice in the Hebrew Scriptures—also in Jeremiah 16:5, with possible allusions in Ezekiel 8:7-13 and Isaiah 28:1-6—but also seems to influence Amos’ earlier criticisms of the northern kingdom of Israel in Amos 2:6-8:

Thus says the Lord:

“For three transgressions of Israel,

and, for four, I will not revoke the punishment,

because they sell the righteous for silver,

and the needy for a pair of sandals -

those who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth

and turn aside the way of the afflicted;

a man and his father go in to the same girl,

so that my holy name is profaned;

they lay themselves down beside every altar

on garments taken in pledge,

and in the house of their God they drink

the wine of those who have been fined.”

There is certainly a temptation here to clutch our pearls at the mere mention of the mingling of altar pieces and body parts. At first blush, Amos’ denunciations wouldn’t seem out of place at a True Love Waits rally. In fact, this passage may even be listed as a Scripture reference on a youth lock-in “covenant agreement.”

Curiously, however, Amos does not seem to condemn such celebrations on their own merits. Rather, Amos’ concerns are primarily with the desecrating division that has devolved religious practice into social exploitation. The ritual has not only superseded the ethical, but been financed by the unethical. In short, the perpetrators have developed a “celebration of discipline” that divorces love of God from love of neighbor (well, some neighbors), a concern most famously expressed in his diatribe against such an unholy division in Amos 5.

Unlike standard prophetic polemics against pagan religious practice, Amos turns his tirade toward Jewish observances specifically endorsed by the Law - festivals (specifically, the hagim prescribed in Exodus 23:15-16), burnt offerings, grain offerings, and fellowship offerings (as prescribed in Leviticus 1-3), and even music. Of particular note is the way the relationship of these ritual practices and acts of justice are structured in relationship to each other. At the foot of Sinai, Moses follows up God’s Greatest Hits (the “10 Commandments”) with a variety of B-sides and album filler material about compensation for knocked-out teeth and singed thorn bushes. Following an extended rumination on property rights, Moses then delivers a robust set of commandments that some Bibles helpfully label as “Social Responsibility” or “Laws of Justice and Mercy,” focusing on the treatment of widows, orphans and aliens, including words that should sound awfully familiar to anyone paying attention to Amos:

“If you lend money to one of my people among you who is needy, do not be like a moneylender; charge him no interest. If you take your neighbor’s cloak as a pledge, return it to him by sunset, because his cloak is the only covering he has for his body. What else will he sleep in? When he cries out to me, I will hear, for I am compassionate.” (Exodus 22:25-27)

Then, and only then, does Moses finally get around to some brief directives on ritual celebrations. For Moses - followed closely here by Amos—the priority is clear: Justice First. Ritual Second. No Justice, No Peace (Offering). In contrast, Amos only finds people who have become experts in ritual and flunked the final exam of righteousness.

Taken collectively, Amos’ striking denunciations of Israelite practices in chapters 2-6 point directly toward a wealthy class whose conspicuous religious consumption was made possible only through exploitation (which, not surprisingly, appears to have been an attribute of marzeahs in other cultures, as well). In addition to the detailed criticisms listed in 2:6-8 and 6:1-7, notice also the following accusations leveled by Amos:

“They do not know how to do right . . . who hoard plunder and loot in their fortresses.” (3:10)

“You women who oppress the poor and crush the needy / and say to your husbands, ‘Bring us some drinks!’” (4:1)

“You trample on the poor / and force him to give you grain.” (5:11)

As one notable prophet would later observe, the house of prayer had been turned into a den of robbers.

The Kentucky poet Wendell Berry has consistently lamented the way Christianity has divorced spiritual and material realities, reflecting a lively Gnosticism-by-another-name habitating inside America’s pulpits and pews. Most memorable perhaps is the following sentiment expressed in “How to be a Poet”:

“There are no unsacred places;

There are only sacred places

And desecrated places.”

Just a wee bit south of Berry, another Appalachian poet was learning this truth in her own characteristically eccentric way. In the tiny Tennessee community of Caton’s Chapel, a young Dolly Parton found “God, music, and sex” coexisting in a small abandoned country church that offered both spiritual and sexual resonance to the developing saint. Between the walls adorned with hand drawn testimonies of youthful sexual escapades and the discarded keys and strings that gave birth to sacred melodies, Parton recalls, she “broke through some sort of spirit wall and found God,” even as she simultaneously experienced an epiphany of sexuality and self-identity. Perhaps taking Berry a step further, Parton offers her witness that even seemingly desecrated places can be sites of sacral revelation.

And none of this would surprise Amos.

Amos does not fear that the sacred has been tainted by the sexual. On the contrary, recognizing the sacredness of both the dwelling of God’s name and the abode of God’s image, what raises the prophet’s ire is that both have been desecrated by the diminishment of the flesh. In the degrading of bodies through exploitation, economic indifference, and greed, Amos writes, what should be a holy celebration has been transformed into a parade of unrighteousness.

To blend the vision of Berry, Parton, and Amos, we might say:

There are no desecrated places;

Only sacred people,

And desecrated people.

Dave McNeely is the Coordinator for the Faith & Justice Scholars Program and an Adjunct Religion Professor at Carson-Newman University in Jefferson City. He is a licensed Baptist minister who spent a decade in youth ministry, and has an undergraduate degree in Religion (Greek minor) from Carson-Newman, an M.Div. with specialization in Christian Education from Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond, and additional study in Justice and Peace Studies at Iliff School of Theology. He was a contributor to A Game for Good Christian’s anthology This Present Former Glory and recently co-authored his first book, Chad and Dave Read the Bible, Vol. 1: The Christmas Story.

1 note

·

View note

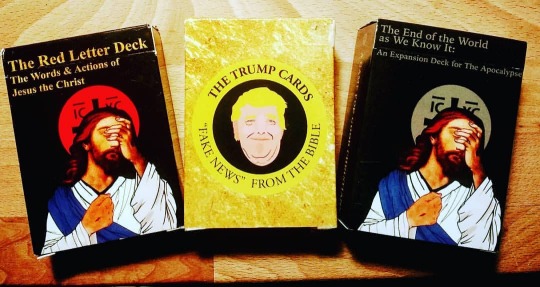

Photo

#happyfathersday ! https://www.instagram.com/p/CQWwbg4BCM1/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

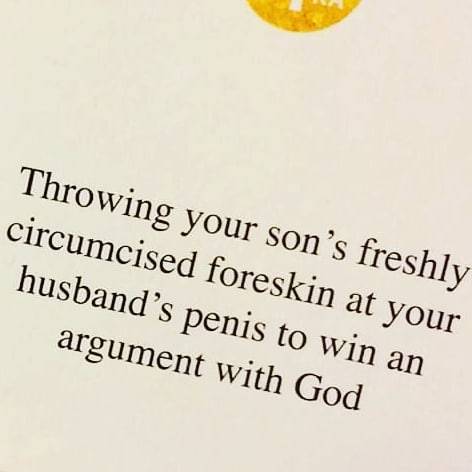

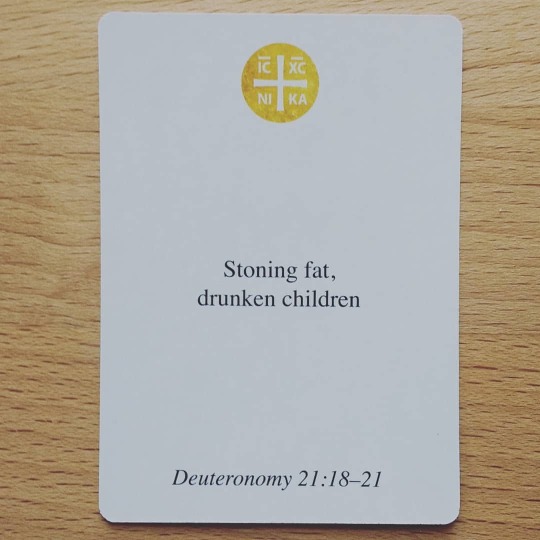

Our #SummerSale is on! The game for people who thought #cardschristianslike was tamer than the #Bible. #agameforgoodchristians = #cardsagainsthumanity for those not afraid of #scripture https://www.instagram.com/p/CQWt7pdhDxJ/?utm_medium=tumblr

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It's that time of the year! #graduation #prom2021 #prom https://www.instagram.com/p/CPvTTLpB5qI/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Text

The Bible’s Nastiest Verse Answers Your Classic White-Person Question [A Guest Card Talk]

Note: this Guest Card Talk is a learned response to our canon card “Babies with their brains dashed against stones (Psalms 137)”

Let’s say you use the psalms as part of your devotions: you read them, or pray them, or chant them, whatever. Maybe you do it on a fixed schedule, the way millions of nuns and monks have for centuries. One day the schedule comes round to Psalm 137. You start to pray it as you pray any psalm, but then you hit verse 9, and you Just. Can’t. Do it.

Happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock.

I couldn’t pray this either, not for the longest time, until the one day I did and it changed something essential in the way I see race. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Why is praying this dreadful verse even a thing?

Pope Paul VI tried to make it not a thing. During the development of the Liturgy of the Hours—the go-to prayer book for Roman Catholics—the pope omitted this verse and about 120 other imprecatory passages (basically, curses), citing the “psychological difficulty” they cause. I get it, and I’ll bet you do too. His Holiness made this omission, however, against the wishes of the very advising commission overseeing the development, and the debate continues to this day.

Skipping the nasties is not limited to the Catholic Church. The Revised Common Lectionary and other Protestant liturgical books omit them as well. Perfectly reasonable, right?

But maybe it’s not that simple. To understand why, we need to look closely at the psalm itself.

Psalm 137 focuses on the most devastating catastrophe to befall ancient Israel: the destruction of Jerusalem (including the Temple) and the seventy-year captivity in Babylon. Somewhere in this disaster, the Babylonian tormentors find yet another way to torment: they ask Israel’s harpists for mirth. “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!” (vs. 3).

It’s easy to gloss over this, for me at least—it was centuries ago, water under the bridge and all that—but think about what’s being asked. A captive harpist could not, under any circumstances, “sing a song of Zion” in Babylon. (Hence the next verse: How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?). Those songs expressed the beating heart of Zion: its culture, its tribes, its Torah, its God, everything the Jews treasured. They’re not fillers for the Saturday night lineup; they’re an act of worship, of Jewishness itself.

Not feeling the horror yet? Try this. Imagine you’re a plantation owner in antebellum America, and you’re putting on a little after-dinner show for some distinguished guests. You’ve heard your slaves singing in the fields, and one of them is very good, so you approach him and say, “Hey, we’re having some people over tonight, and they’ll be expecting entertainment after dinner. So c’mon up to the house and sing us one of those ditties you colored folks sing in your prayer meetings.”

No. Just. No.

Now throw in the Edomites from verse 7:

Remember, O Lord, against the Edomites

The day of Jerusalem’s fall,

How they said, “Tear it down! Tear it down!

Down to its foundations!”

As you may recall, the Edomites originated with Esau, the brother of Jacob. You might think that common ancestry (conflicted as it was) might hold the two countries together, but no. Not only did the Edomites jeer on Babylon’s destruction of Jerusalem, they stationed themselves on the perimeter of the city, caught any fleeing Israelites, and returned them to Babylon’s army for execution or enslavement. Now that I know that, I get furious reading this verse. Verse 8 then turns the attention back to Babylon, starting the call for vengeance that culminates in the child-bashing verse 9.

By this point, verse 9 isn’t so scandalous. It’s not even surprising. The rage here is what so many oppressed people feel every day. Which is why I’ll go out on a limb and say that for certain folks (I’m looking at us, white people) praying it should be a thing.

I say this because of how the verse changed me. As a white person, I haven’t experienced bone-deep rage many times in my life, if ever. I have zero experience with grinding, tormenting, humiliating oppression. By praying this psalm, I came face to face with the tiniest glimpse of what it’s like to be oppressed, and the fury it deserves. That glimpse moved me one step further toward listening long, deeply, with full attention whenever Black people talk about their history and life in America today. I don’t know it firsthand—I can’t—so I must hear them and consider the reality they present.

When you see it this way, Psalm 137 becomes an eloquent and powerful response to the question sometimes asked by white people, “Why are Black people so angry?” If you’re asking that question, start with this psalm—and then go read everything you can find written by Black people about Black experience. After a while happy shall they be who take your little ones and dash them against the rock won’t surprise you either.

*A spiritual director, bigender person, and quasi-hermit, John Backman writes about ancient spirituality and the ways it collides with postmodern life. This includes a book (Why Can’t We Talk? Christian Wisdom on Dialogue as a Habit of the Heart) and personal essays in Catapult and many other journals. John has presented at a range of conferences, including the 2015 Parliament of the World’s Religions.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

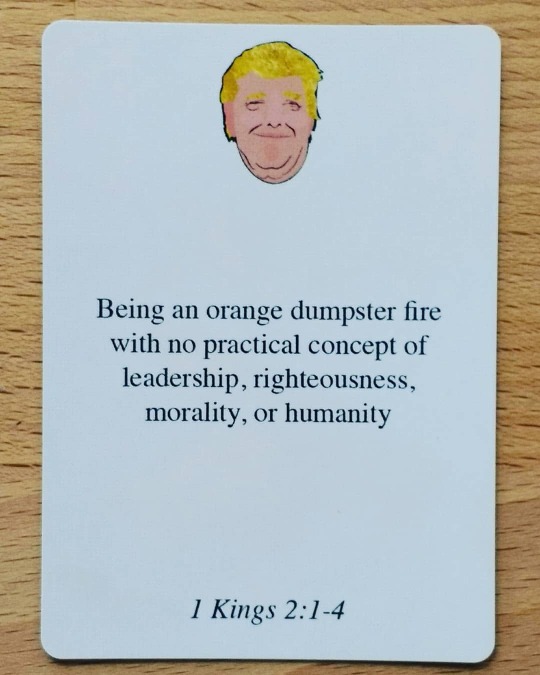

For the people #mad we make fun of #Trump over the past four years: you really just finding out about us now? So sad for you 😭 https://www.instagram.com/p/COi_5o3Bdy0/?igshid=wnquw4a1buym

0 notes

Text

The writing on the wall (Daniel 5:27)

Note: This is our first Card Talk from our The End of the World as We Know It: An Expansion Deck for the Apocalypse.

The Biblical Story

In chapter 5 of the Book of Daniel, the Babylonian king Belshazzar is throwing a feast in his palace. The party is had on the backs of stolen labor and stolen goods. But, in Belshazzar’s “defense,” he didn’t steal the Jewish people (the ones who weren’t murdered outright, or died while being force-marched across the landscape), or steal their material goods: his father did that. Sure, he was still directly benefiting from those horrible actions, and was in no way attempting to address those wrongs, but can you really blame a guy for his inaction, and the perpetuation of a system that oppresses others, when he wasn’t the one to put the whole system into motion?

Belshazzar’s party is disrupted when a ghostly, giant hand writes mystical words on the wall. The festivities are further complicated because they don’t know what the words on the wall mean, they can’t read them. Belshazzar doesn’t know what to do. His friends and advisors and wisest men are no help.

The decision is made to call their token Jewish “friend,” one of those stolen Jews (but remember, that’s their fathers’ fault, not theirs). They hope he will have an answer, as he is wise, and the script looks like something his (lesser) people dabble in. They call Daniel.

And Daniel is able to read the writing on the wall. But Belshazzar is suddenly confronted with his privilege, his family crime. He is being judged for the systemic injustices at the heart of his empire, even if daddy dearest set them in motion.

Condemnation hangs over them.

Chickens are coming home to roost.

The whirlwind is being reaped.

{An Excursus (of sorts)}

A business man in his prime is out celebrating with friends, spending the money he inherited from his father. Money his father earned stepping on the backs of others. Shady land deals. Predatory lending practices. Resources “borrowed” from pensions. The results of unpaid invoices for an honest day’s labor. Lawsuits and insider trading that left people penniless. The business man knows, vaguely, about what his father was into, but doesn’t consider that any of his concern.

A waiter bumps into the table. Spills a glass of water, not on the man, but close enough. From one of the business man’s friends, the waiter receives a racial slur amid the rest of the verbal reward for his clumsiness. This is not an unusual occurrence, but it will be the straw that will break the waiter’s back. He will lose his job, but the things he said have left a mark on the business man.

Sure, maybe (maybe) he should have chided his friend for his use of such language—on this occasion and in the past—but he is certainly not a “racist.” He volunteers in the “ghetto.” He voted for Obama. Twice. He felt Trump should have tweeted less. He’s progressive, educated, and cultured. He loves Beyoncé.

He calls his roommate from freshman year in college, the only Black person in his smart phone that doesn’t work for him. He explains what happened.

Silence.

He then begins to ask him the question, to soothe his aching self-identity.

There’s more silence over the line.

And then a deep sigh.

And then his lone Black “friend,” exhausted, tells him the truth...

The Writing on Belshazzar’s Wall

וּדְנָה כְתָבָא דִּי רְשִׁים מְנֵא מְנֵא תְּקֵל וּפַרְסִֽין׃

MENE TEKEL PARSIN

The writing was in Aramaic which, without the vowel pointing present, could not be read by the Babylonians. But this is common, even today: the oppressor seldom learns the language of the oppressed.

The same three consonants can be used as a noun or a verb, depending on the vowels and the conjugation. In this case, the noun forms of the writing on the wall were types of currency of the day, while the verbs are upon what Daniel is giving his prophetic word.

“This is the interpretation of the matter:

mene, God has numbered the days of your kingdom and brought it to an end;

tekel, you have been weighed on the scales and found wanting;

peres, your kingdom is divided and given to the Medes and Persians.”…

That very night Belshazzar, the Chaldean king, was killed. And Darius the Mede received the kingdom, being about sixty-two years old. (Daniel 5:26-31)

“tekel, you have been weighed on the scales and found wanting” (Daniel 5:27)

A Thought Experiment

Imagine that words have weight. Not metaphorically. Not emotionally (for they already have both). We mean real weight. Actual mass. In pounds or grams or whatever system makes you feel the most at home.

Imagine your words as perfect cubes, blocks of granite. Each word weights exactly the same. It doesn’t matter if the word is kind or cruel, a word of healing or hurting.

Now imagine there is a scale called “outrage.”

Place on one side all the words you’ve said related to treatment of the poor, the widows, the orphans, the stranger, the abused by unjust authority, the exploited, the discriminated against.

Place on the other side all the words you’ve said that ignores the plight of the hurting, so you can justify some personal or political point of view. They might include references to “both sides,” “reverse racism,” or “all lives/blue lives matter.” They might include questions like “what was she wearing?” and “why didn’t he just follow their commands?” They might include xenophobic nationalism masquerading as patriotism, forgetting that Jesus said the Kingdom of God/Heaven is not of this world, is not the United States, or anywhere else pretending it’s a “Christian nation.”

Now ask yourself

Which side weighs more?

Now image you put actions on those scales…

Perhaps now is a good time for you to put the glass down and listen to the silent stylus scratching, the writing on the wall.

Perhaps you should take stock of your complicity in the oppression of others, despite your many reasons for saying, it has nothing to do with you. That you’re not a racist - sexist -homophobe - transphobe - ageist - ableist - elitist - [insert other assholery] because of [insert the ‘close personal friend/relative’ (who really isn’t)].

Perhaps you should figure out what they have been trying to tell you, but you’re too sure of yourself, sure of your ideas, to hear.

Before it’s too late.

But what do we know, we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

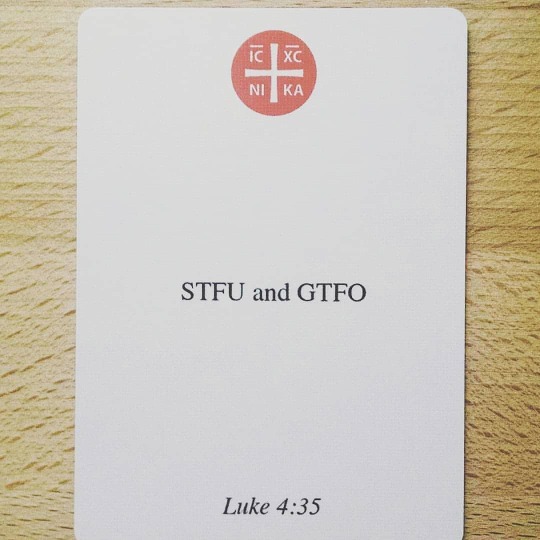

#Pastors writing #sermons for tomorrow, We don't need your words about #prayer and #unity right now. Either directly confront the #racism and #whitesupremacy at the root of the #insurrection in #washingtondc, or kindly: https://www.instagram.com/p/CJ1vf0khW8k/?igshid=1mjdgxy0ykdzp

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dear #Trump supporters: This. Love #democracy and #christianity https://www.instagram.com/p/CJucFbPhtm3/?igshid=geccydogdn8r

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Expanded expansion decks for sale! #christmasgift #christian #games #giftideas #cardgame #losertrump #jesus #apocalypse #endoftheworld #humor #familytime https://www.instagram.com/p/CIxDPLcBPEw/?igshid=g3he1x1g1hgq

#christmasgift#christian#games#giftideas#cardgame#losertrump#jesus#apocalypse#endoftheworld#humor#familytime

0 notes

Photo

The Apocalypse Deck is here in time for #Christmas. #TheEndOfTheWorld #christmasgift #realbibletalk #Bible https://www.instagram.com/p/CID8FCQhINS/?igshid=4hbwfbjmjbzs

1 note

·

View note

Text

This Present Former Glory: An Anthology of Honest Spiritual Literature

A Game for Good Christians is proud to present This Present Former Glory: An Anthology of Honest Spiritual Literature! Through poetry, fiction, creative non-fiction, and dramatic works, 45 modern authors tackle the wide spectrum of spiritual and practical concerns in this 227 page anthology.

Price: $16.95 (includes shipping and handling)

An excerpt from the Editor’s Note:

… A Game for Good Christians put out a call for “honest spiritual literature” grounded in the totality of the human experience: the good, the bad, the salvific, and the sinister. Through drama, fiction, memoir, and poetry, the authors in this collection answered that call and the myriad questions strewn at the feet of our crumbling realities. They engage in the timeless, needed arts of holy doubt and righteous blasphemy. They deftly give voice to multiple facets of humanity’s struggle with the Numinous. They pray, lift praise, accuse, redeem, and accept nothing less than truth. Herein you will see Moses, Sampson, and Jonah alongside Eve, Bathsheba, and multiple Marys. Ancient saints, good Samaritans, and Greta Thunberg share conversational space with slave holders, shit-talkers, and Joel Olsteen. And, of course, Mary Oliver makes an appearance.

This anthology is organized in three sections, with an eye to Walter Brueggemann’s contention that the Book of Psalms captures the emotional ebb and flow of our lives: “orientation,” “disorientation,” and “reorientation.”1 While there are times we live in joy—our equilibrium secure—, our peace can shatter like a fine plate at any moment, and we are forced to construct a new normal if we have any hope of survival.

The Word of the LORD that Haggai received ends with a promise: in a place dedicated to peace, a future glory will outshine the past. But Temples—like communities, like social constructs, like systems— are built by human hands. Any glorious future of peace begins by a person taking a step, saying a word, lifting a pen, and calling others to join in the work. We dare to believe a collection such as this helps usher in the Judaic hope of tikkun olam—the repair of the world, the building of peace…

Until that day, we are here, in the present, trying to capture something old, something beautiful in its purity, something that can propel us into a greater glory…

Click here for more information.

2 notes

·

View notes

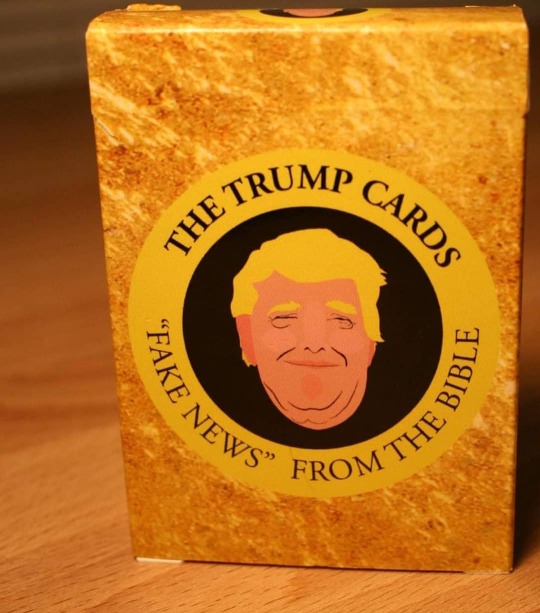

Photo

#realtalk though: how would you feel if we brought this back for a (VERY) limited run? #trumpisanidiot #45 #trumpcards #agameforgoodchristians #dumpsterfire #orangedumpsterfire #vote #limitededition #realbibletalk #expansion #bringitback https://www.instagram.com/p/CGoPrFQhHie/?igshid=fhmtn9kbtvv9

#realtalk#trumpisanidiot#45#trumpcards#agameforgoodchristians#dumpsterfire#orangedumpsterfire#vote#limitededition#realbibletalk#expansion#bringitback

2 notes

·

View notes