Text

Cypress in the Mirror

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On View

It was evident when I entered the museum that I was the first one there—of the day certainly, of the week perhaps. The young man behind the ticketing desk cast a gaze of both alarm and welcome, the former sentiment only yielding to the latter as I neared and as I spoke confirming myself, I presume, to be of the immediately living rather than the spectrally lingering as he said he did not hear the door when I entered. Though the town of Ellerbe, of which the Rankin Museum is in, declines of late in number, it is far from a ghost town, though perhaps one can imagine many ghosts in the town, leisurely ones probably who “haunt”, in the gentle sense, the spa which first vivified the place, and in the museum, if there is a presence there, it is the founder’s, Dr. Pressley R. Rankin, Jr. (1920-2010), who looks over you from behind as you buy a ticket, lab coat, tie and smile all pressed with an admirable crisp.

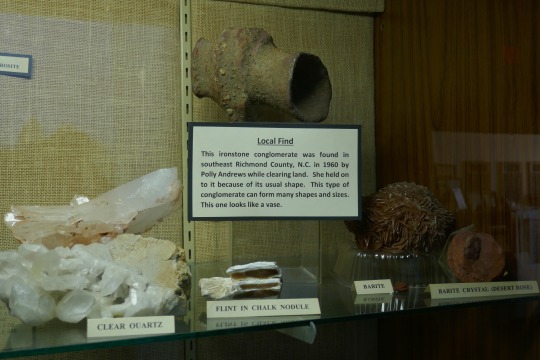

L-, the young man behind the desk, explained to me that the main collection in the hall to my right could be thought of in thirds: one third things the doctor had acquired over his life, one third things donated by local people, one third things acquired; consequently, the division was a third natural history, a third local history, a third Native American history. L-, also apologized if he seemed slow or off, it was just tiredness he said. He seemed ready to explain, but two men entered so I paid my one-dollar fee and began wandering the galleries.

The first thing I saw was a hammerhead shark mounted above display cases of fossils and minerals, its mouth agape. I took it as an allegory of how perception should work in a gallery, for the eyes of the shark, so widely spaced on opposite ends of its head, give it vision in the round, a capacity which fills its belly with food in the sea, but if it, or we, could swim through a museum with such eyes it would fill our thought with inquiry. We could see at once the many minerals on one wall and the display of “First Americans” across from it on the other wall and ponder what the relations between the two could be. We could turn the corner and with one eye look into both eyes of taxidermic mammals expressionless but not quite dead, and with our other eye gaze at fossils of things that lived before nature even considered fur as an option. Swim across the hall and the juxtapositions would continue, shelves of salves, serums and antidotes from early last century—Ramon’s Santonine Wurm Syrup, New Life Pills, The Great Paw Wap Blood Purifier (Infallible Remedy-GUARANTEED)—to your starboard side and to your port side a diorama of the same era’s home entertainments, a stereoscope and cards in a child’s seat and basket serving as another allegory of seeing as the two displays together give some vision of the way the people were at once treated in pain and treated to pleasure.

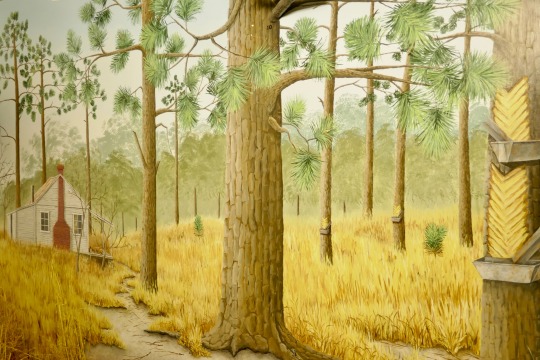

But move a little further and we will want to surrender vision in the round for a narrower kind that stays and stares (or at least I would) coming before the naval stores turpentine still housed behind large glass panes. I did not know it was there (in fact, I knew very little about the museum having only seen it on an old brochure of area attractions left in an even older book back at Weymouth House). Pictures of stills I had seen, but now I could more readily imagine the process of warming the viscose fluid tapped from pines, boiled into spirits of turpentine and the ooze left behind cooled into rosin. The tools of the trade, sifts, spatulas and hacks lay around the still, as do the scarred remnants of long leaf pines which once fueled its profits and fell to its devastation. A fox squirrel, a rattlesnake, a woodpecker and a hornet’s nest also inhabited corners of the display, for these trees supplied not just a place of industry but also provided home for many creatures who, if not for current efforts to plant these pines again, would likely only be seen stuffed and stiff made known by labels.

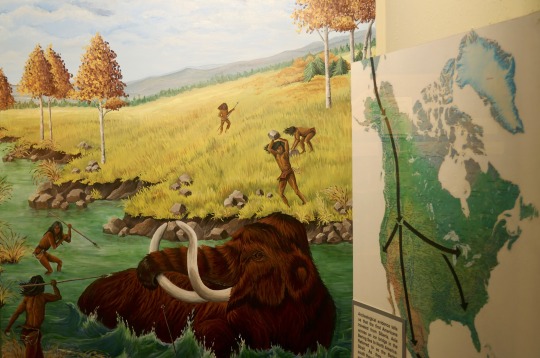

When I did finally turn from the distillery, I was soon stilled again, in the galleries devoted to Native American cultures, for in the middle of the floor was yet another thing I had only known by photograph but never been so close that I could touch it if such were allowed. It was a dugout canoe. You hear the name and think a canoe that has been dug out from the trunk of a tree and the idea seems, at least to me, more fancy than fact even with descriptions of how it was done—fire used to prepare the wood for a hollow, clay to direct the fire, and hard tools of stone or shell to gouge out the flame softened parts. But then to see it, to see the gouges and groves that remain after years and years and years of lying in a lake or in a river after it was no longer ridden in because its makers were ridden away—then fact does not so much suddenly supplant fancy as commingles with it to resuscitate the past, not wholly back into life, but far from its decease.

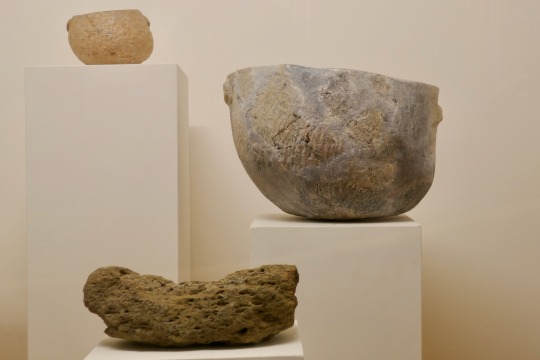

Other of the objects in those galleries had a similar effect though not conveyed through their singularity as much as through their abundance. Like the minerals, and eggs and fossils of the natural history room, the arrowheads, pottery shards and axes of the Native American galleries were arranged in a way that reminded me of salon hangs—walls of pictures aplenty that seem to work more by a kind of engaged distraction rather focused attention, a visual pleasure of variety and abundance rather than individual frames for contemplation. But though both variety and abundance are usually connotative benefits, the tone of each is inflected by what they describe. So many painting on the wall can at times tend toward a feeling of iteration (another nude, another battle, another table full of grapes), while a multitude of minerals each peculiar in color and geometry soon become a chorus chanting of how unknown the earth remains below. The Native American implements hover somewhere between iteration and the unknown, one shard of pottery seems like another until you realize two may have fit together, created something more than fragments, but even if all these fragments could be reconstructed they’d still be just pieces bereft of what they may have meant and all the things they could have held. There are probably more axe handles present and more space in the canoe than there were members of the tribes that made them in their finals years before disease, death or assimilation caused so many to disappear. The abundance of their things can begin to feel as if they are overburdened with a silence that they cannot yet bear to break to talk about.

I wish that I could speak with Dr. Rankin ask him on one of the tours he gave until the very end what first thing did he buy, from where and what meaning did it hold for him, ask him as well what first thing couldn’t he buy, from where and would he still want it now. His obituary recounts a life as varied as his collection, a doctor who still made house calls, “delivered babies; set broken bones and sutured wounds in his office; diagnosed all types of illnesses; and became a family friend to his patients”, and a doctor who traveled the world as a surgeon in the Air Force before serving in the local world of county and state, sitting on the board of banks and brick companies, and also heritage sites, the state archaeological committee and its forestry association—in “1983, Rankin was named N.C. Tree Farmer of the Year” and after other accolades he “was a 2006 recipient of an honor award from the Smithsonian Museum of American Indians.”[1] Maybe everything in the museum made sense to him logically in the way they do visually for the hammerhead shark, the world arranged in a spherical comprehension cohering less by dates and lines of provenance than by desire and particularity. Historians I think are shaped much more like cone headed sharks than hammerhead collectors, but the waters of the past are large enough for both to swim.

An hour and a half had passed where I thought only a third of that would. It had been awhile since there was another in the galleries—a single man who just looked at the local history; the two men who had entered after me had long since left, truly swimming through the rooms, as they had primarily come to see the special exhibition, which was on the other side of the entrance, and where I went last. It is dedicated to the actor and wrestler Andre the Giant, put up about four years ago, it appears now to be permanent. Though he was dead before I was born, I recall him from film and footage. Looking at the life-size seven foot by four-inch cutout of him one sees a body outgrowing being a body, or at least a body that can support itself—the crutches he used in the last years of his short life lean across from the sturdy cut-out. Andre lived in Ellerbe and once he died his things passed to his friends, who eventually passed them to the museum. So, he counts under the local history category of the collections, though it is hard to think the curiosity of natural history doesn’t also inflect fascination with him, a man with hands that could hold a head as if it were a baseball ball, and probably a sufferance much more vast than even his great size as he bore his body’s pains with a somber smile.

As I started to leave, L- asked me what I thought of the museum, but thought was still mostly feeling as yet able to organize itself with the compact facility of an object label. Yet we chatted for much longer than I thought we would; he told me about his studies in industrial design, showed me the full-size patterns of nineteenth century garments he was drawing right then on a side table, preparing to cut them so that he could later sew them so that he and his friends could wear them even if people in the town did not understand why, he told me about his yearning to leave the town to work in a different kind of museum, he told me, suddenly, that I was beautiful and proceeded to show me the outdoor flume where families often flocked so that children could mine for gems a bucket at a time. Out of the refuse pile, as if it had been waiting to be retrieved, he picked out a small fossil and placed it in my hand. I know not of what creature it was a part, but I hold it as the final piece of my time at the Rankin.

Notes:

[1] See: Pressley R. Rankin, Jr. ’42 – Davidson College – In Memoriam. 9 Oct. 2010, https://inmemoriam.davidson.edu/2010/10/pressley-r-rankin-jr-42/.

Image Credit:

Dr. P. R. Rankin teaches museum visitors of all ages about his collections. November 10, 2001, NC Digital Collections, North Carolina Echo Project. https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/rankin-museum-of-american-heritage/50766

0 notes

Text

Rankin Museum

0 notes

Text

Pseudo-Currency of the Republic of Pineland, Rankin Museum

At the end of special forces training, before attaining one’s green beret, the final task is to infiltrate fifteen counties in central North Carolina that have become the People’s Republic of Pineland, the goal of the task is to liberate these people‚—and implicitly their piney lands—from oppression.

0 notes

Text

Soapstone Bowls, Rankin Museum

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Projectile Points, Rankin Museum

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Local Pottery, Rankin Museum

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

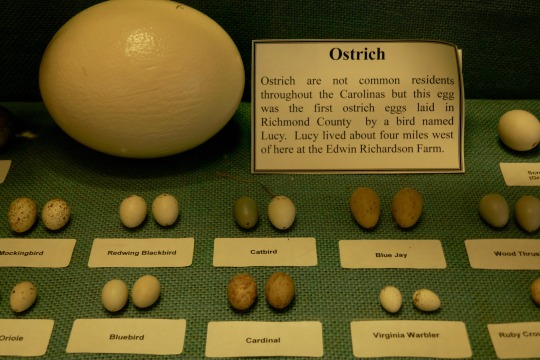

Lucy's Egg and Other Birds Eggs, Rankin Museum

0 notes

Text

Some Animal Mounts, Rankin Museum

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turpentine Still, Rankin Museum

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part of the Turpentine Display II, Rankin Museum

1 note

·

View note

Text

Part of the Turpentine Display, The Rankin Museum

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tree by Tree

It was 9:19am when I arrived, so nineteenth minutes later than planned, yet when I stepped out of the car Tim greeted me with such kindness that I forgot to ask pardon for my tardiness. To my left, a tall stand of pines, loblolly and shortleaf, stood beside the driveway; on the other side, growing in the shade cast by those pines were a few longleaf pines, over fifteen feet tall, over fifteen years old but still not evocative of what one would call a tree—that takes time for longleaf to achieve. I was not the only one visiting Tim that morning, his daughter Brittany and her two children, a nine-year-old boy, and a four-year-old girl, were there as well. We all sat down on the porch, except the kids who went off to “saddle” the cats with plastic water pipes.

I first met Tim a few days earlier at a Longleaf Academy, a two-day course in all things related to the tree hosted by the Longleaf Alliance: planting, tending, tax breaks, easements, history, pine straw selling. Before a site visit to see management practices at the Sandhills Game Lands, everyone was asked to carpool; vehicles with off road capabilities were suggested as the ways were mostly loose sand and gravel, some banked high, some potholed low. So, in most went into pickups, SUVs and the like, save those who road with Tim in his Prius. “When you get stuck,” more than one of the other drivers quipped, “don’t worry I got a good tow.” “It’ll go just fine” Tim assured them and his three passengers: a forester, a teacher and myself— indeed Toyota should consider marketing the off-road capacities of the car more as it did go just fine up sand banks, minimal sliding on the ascent.

From his porch (where I see he owns a truck) amidst wind chimes I tell he and Brittany about my work, in turn Tim tells me about his family land, held since the late 19th century, some of it sold off over the years, though still eighty-six acres; his grandkids are the seventh generation of Martins to roam the land— they live down the road, Martin Road, from him. Brittany, an educator, knew the small towns of my childhood over one hundred and fifty miles eastward having taught there through TFA. Now she was back home leading her own school called Wander and Root, whose classroom is the outdoors. When the floor is the ground, the ceiling the sky, and the walls the nearest pine tree, every lesson can start with a “What’s this” or “Look at that” initiated more likely by the roving curiosity of children than by a teacher as suddenly happened while we were talking for Brittany’s son came over to show us an urticating caterpillar he caught on a leaf, its hairs so dense as to look like a forest miniature hitched to a mound of moving flesh. We took his discovery as a call to move, to wander and root in the Martin woods as it were, where Tim would tell of longleaf’s past and present there.

Only steps from the house we stopped in a stand of well settled loblolly pines, some about a foot thick ascendant in the sun, far below were thin hardwoods waiting for their chance for light many of them sweetgum saplings barely knee height; underneath their wide green leaves and under the layers of years of pine needles, though somewhat obscured and quite softened by time, you could see the ground running still in curves— remnants of field terracing for tobacco. The trees above seemed oblivious to the order with which the old crop was planted, but orange blaze marks on the loblolly pines, and indentations on the sweetgums and other hardwood trunks foretold of a new order to come. An orange marked pines would be a pine spared, a tree with an indentation was not only marked for removal but was already dead or dying even if it still carried leaves. Actually, these marking represented two different plans of order. The loblollies were blazed by foresters who came out to Tim’s property to help him select trees to save as he prepared to thin and clear areas for extensive longleaf planting. After the trees were marked, Tim had a deal with a local timber company to come in and do the cutting, clearing and carrying-away, but just when they would have started the business went bust. Eighty-six acres, by most measures, for a private landowner, is a lot of land, but not as much as to be attractive for logging companies in the area. Tim tried but could not secure another timber contract, so he decided to do the clearing himself. Many of the trees on his land have rings around their trunks—girdled by chainsaw, but even more destined to go have just one or two hacks on them, if you did not know what these marks meant you might mistake them for random cleaves of a tepid ax, but these small indentations are targeted and fatal.

In silviculture and forest management the technique is called the hack and squirt method, because in one hand you carry a hatchet in which you hack into a tree, just deep enough to expose its living tissue, and then you squirt—either directly into the cut or onto the hatchet so that it slides down into the cut—an herbicide. In less than a year the tree will defoliate, opening up light to the ground and in subsequent years as the dead tree decays branches will break off and eventually the whole thing will fall. Much less expensive than logging, and less strenuous than chain sawing, the disadvantage of hack and squirt is that it is slower, and if done when trees are moving sap up they will push the herbicide out and go on living (likewise they can also move the herbicide down and effect trees not selected for removal). Assuming about 200 trees to an acre on his land, means he has look at over 17000 trees and decide at each one whether to leave it or kill and then later on whether to clear what has been killed (and of course in the meantime wherever the canopy opens up something is going to start growing that itself may have to be removed later). I thought about Sisyphus for a moment then I thought about Prius— “It’ll go just fine.”

At the edge of the first woods, we came to a clearing on a hill where the shade abruptly ended and the sun touched strong on the ground, a stand of longleaf pine Tim planted fifteen years ago took every ray that fell on them, all of them eager for their next fifteen years. On the path, Brittany’s four-year-old daughter yelped with equal parts delight and dismay pointing to another hairy caterpillar, dead of life but body vibrant with the work of fire ants who, as they dismantled it also seemed to reanimate it. The path sloped downward into a mixed wood whose density was slowly being decreased by hack and squirt, by girdling and by prescribed fires—pale skeletons of holly, not a particularly flame-resistant tree, abounded, while wild grape carpeted the floor in the aftermath of burning; coteries of mushrooms white, pink, orange, giant, small sized, plump and formless proliferated near and far. Amidst it all nearly everywhere we looked were longleaf stumps and left-over longleaf branch knots. These were from old longleaf, cut maybe a century ago after growing for two, three, perhaps even four centuries before that, remnant now as the fragments of a disbanded museum. It is these pieces of the past forest that Tim’s feels warrants his efforts for taking down so many of the trees that grow there now; it was longleaf land before, and he wants it to be longleaf land again.

But it has been a while since longleaf predominated over any part of North Carolina; by the early 20th century it was almost all gone and in the intervening century, not only have other pines and many hardwoods put down roots where they were once out shaded or out fired by longleaf, but so have many other kinds of plants, some of which only began to settle the land in the same decades as Tim’s ancestor did. Emerging out of the forest, we came to another hill that was a clearing which Tim had put longleaf seedling in a few years ago—"was a clearing” for now it was a lake of Bermuda grass (introduced in the mid-18th century from Eurasia), Chinese lespedeza (introduced in 1896 from Japan) and dog fennel (a highly migrant native) that was taller than either of us. We waded in to try to find any surviving seedlings, the delicate leaves of dog fennel, feathery against the skin, breaking as we passed them releasing their odor of carrots and pepper and sweets and green tang all warming over in the sun—“Why would you want longleaf? Lay, be sweet be soft with us?” the slender poison tresses tried to tempt me. But I kept my eyes on the ground along with Tim’s, looking for the seedling trees, all still in their “grass stage” as it is called which made them nearly indistinguishable from all else around, but by parting deep the waves of green around us, we found some holding out at the bottom like benthic anemones. I was thinking what Tim soon said aloud—that the seedling there, though not dead were foregone, trees potentially one hundred feet tall cut short by herbaceous perennials that only rise to a tenth of that (though a speedy rise it is). He’ll likely have to mow the area down and try replanting the pines again.

When we reemerged from the vegetal waters, stepping onto the dry land of a firebreak, Brittany and the grandkids came to say goodbye to us. She held some of the old longleaf knots in her hand, lightered knots, as they are called, good for starting fires which is what she will do with them. Her little girl had picked scuppernongs and offered one each to us, “Spit out the seeds” she said, her face covered in a make-up of mushroom fuzz, grape juice, char, sweat, soil, pine and whatever she grasped and gathered while wandering the woods—it was a kind of earthy cosmetics that might improve all our faces if we wore it. As they started back, Tim and I started down stopping mid-slope to look at the oldest grove of longleaf on the property, offspring probably from parent trees that were cut in the 19th century. Their airy crowns, unimpeded by anything above them is the way Tim wants all his longleaf to be when he looks up, but looking down to their root crowns presented a much less promising image— layers of pinecones, branches, pine straw, and the leaf litter of midstory trees all bundled up with fresh ground trailing vines. This accumulation is called duff. It occurs on any forest floor, but more accrues in a piney wood as needles decompose much slower than leaves. As a kid I often sank my hands into the duff under our loblolly pines for it was like a layer cake of cool earth, dark, dense, damp and near fully decayed at its deepest level with increasing integrity near the top, tan brown, with spent though still stiff needles interwoven. Our layers were only ever a few years old as we rotated where we raked, but Tim suspects the duff around his old longleaf has not been disturbed since the 1920s. Though certainly good for releasing nutrients back down into soil, once it becomes this thick it will not let much back up from soil, especially longleaf seedings, which need to touch bare mineral soil to germinate. Prior to the 20th century’s anti-burning forestry practices (“Only you…”), whatever duff accumulated on the ground would be burned away every few years by fires set either by storm, or more likely by hand, the hands of Native Americans before contact, and the hands of settles who learned and burned after them. The fire would trace the path of needles on the ground, burning slow and shallow, exposing the sandy soil underneath before dying at a ditch, a creek or damp ground. Setting fire to decades worth of duff however is like throwing a Molotov into a paper mill—fire hotter, higher, longer, deeper and deadlier for trees, even fire-tolerant longleaf pines. Nevertheless, Tim had tired it earlier in the year, blowing some of the duff away from the base of the trees first, in the hope that with fuel removed they would not be gridled by fire. Whether this helped or whether the trees were harmed if not lost he is still waiting to see. Most still had green needles, but we saw several green cones on the ground, cones already larger than all other kinds of pinecones in the southeast but still far from being mature and ready to be released from the tree. Had the fire caused the cones to drop prematurely? Or was it squirrels? Or was it something else entirely. Trees often answer our questions no quicker than they grow.

As we walked further down the hill where the fire had sat before a break, I saw a box turtle’s shell, the pattern orange and brown much like the color of duff; there was no turtle inside—not just rooted life gets eaten by the flame, though while the fire consumes individuals it also produces improved habitat for those that survive. Fire in a house is perhaps always a bad thing, but such destruction (or perhaps better “disturbance” as the ecologist calls it) out of doors almost always aids something else’s creation, spread or, in the case of longleaf, return.

With the hill leveling out into bottomland, I could see several large white oaks. Tim never thins these out, but often the wind does by felling them, breaking the shady vault that they buttrees, light consequently flooding in. In these lambent islands Tim often plants longleaf seedling, some doing alright, though loblolly pines always find a way to sneak in around them, while the mid-story shade of sourwood—another species he is thinning out (though leaving some as a favor to bees)—reduces their growth rate. “A forester would tell you that this part of the land is supposed to be oak, sourwood, hickory and the other hardwoods” Tim said, “but all these stumps say differently.” Longleaf stumps, but also longleaf catfaces, as on the higher ground, were scattered around us, the latter raised off the ground to slow their decay so that that could remain a little longer as signs of the piney woods past—its trees and its people—those who made the catfaces on the pine for turpentine and those who maintained the swampy ground for it so that it would not be outcompeted by trees better adapted to moist sites.

Going up once more, we came to a field of an acre or so, deep brown and dry though at its border forest trees green and crowded stood, I imagined, on their toes, not wanting to get their feet wet in the soil under that field which was all brown because of an herbicide—one of the few places that Tim had spread it broad rather than specifically. His mom, eight years away from a century of living, called him; as they spoke, I looked over the desiccated field, the slightest step into it sounded like tap-dancing on crackers. Herbicided grounds make me think of the reset option on video games, the option you reach for when you are so frustrated by lack of direction or progress on a level and you just want to start over—do it well, do it right, do it done the next time around. If it’s a really difficult level the resets might just mount until you quit, or you might finally succeed, promptly forgetting how long it took as you move to the next level. With land though we cannot quit, nor can we forget it for it always reminds us of how present challenges result from past use.

When he finished his phone call we went back into the woods and took a few steps off the trail to see the pink lady slipper orchids he planted. Only the large, paired, tongue like leaves and spent stems were present by late summer, but he showed me a photo of their very showy flowers from earlier that year. Above us, I asked about his tree stand. Back in the 1980s Tim started bowhunting, something he said was not much done at the time. To kill a deer with a bow you have to get a lot closer to it than you do with a rifle, closer than most people probably ever get near deer because either you have to be very quiet when you approach them or (more likely) when they approach you, unbeknownst to them as you wait in the stand. Once proximity is attained there comes the matter of aim. It’s not that you can aim and shoot a deer anywhere with a rifle and then proceed to catch it once it dies, but a bullet has more places it can enter for a mortal wound than an arrow does. It takes time to learn to aim a bow anywhere let alone directing it (ideally) to the deer’s broadside, between its ribs, piercing its heart and both lungs, the arrow continuing clean through the animal as if the penetration was phantasmic, the deer leaping more startled than stunned, not realizing as it stands, as it stammer, as it sits that it is dead. A record of failure is likely a bowhunter’s bounty long before the attainment of a kill. But each failure is also likely a gain for in having to just “stand and stare” while in the woods observing the ways of the prey, observing the ways of the wood, and observing oneself, one enters a kind of out school, perhaps not unlike Brittany’s. Its and education whose lessons in waiting, watching and life-taking are not dissimilar to learning to plant longleaf pines.

Our walk took us back downward, towards the banks of Drowning Creek, where, true to name, you could see several pieces of old longleaf “drowned” in its waters, sometimes you see less sometimes you see more, Tim told me, depending on what the beavers are doing upstream. As there was lots of rivercane around the creek banks, he asked me if I knew how it, like longleaf, once covered expanses that ground bound eyes could only ever incompletely see, in the depths of which snakes, and insects, large cats and birds like the Carolina parakeet made their lives and later lost their lives as this habitat disappeared. “If all I was doing was just for longleaf, it wouldn’t be worth it. I am doing it for everything that lived with longleaf” he told me.

Where the patch of cane ended and further on, I began to see several glass bottles, as if the remnants of a grand party from a century ago, though actually, as Tim explained, they were used to hold up netting over the tobacco crop that once grew here—now they were accidental terrariums filling with ferns. Mixed with the glass bottles were cans, labels wholly rusted, sides often busted, they once held last century’s pest- and herbicides, though unlike the glass bottles, they held nothing inside as if roots refuse to find homes in them.

Loblolly pines, as would be expected (a loblolly is a mire), grew quite well, straight, and thick in the creek wet lowlands. I do not often like to think of trees in terms of timber but knowing that Tim wants to get rid of them for longleaf, I told him that there must be lumbermen somewhere who would take the trees. “Standing money” is what some of my folks call he said, “could probably get about $200 a trunk.” But at this point the thought of big equipment, their noise, their tracks, and the scene that follows their departure suggested an aesthetic and perhaps ethical expense a lot higher than whatever returns he would get in terms of dollars—“I recently learned about a thing they call forest bathing. When I first heard, I thought it meant literal bathing in the woods which seems strange, then I learned more about it. I feel like that is what I have been doing here all along.” I imagine Tim finishing a shift at hospital where he works as a nurse or waking up early on an off day and going outside. He has a hatchet in one hand, and a bottle in the other filled largely with water, and just a little imazapyr, the name of herbicide sounding like some ancient weapon which is this case prevents plants from ever growing again once it gets inside them. As he listens to the sounds of morning birds, he sees the long gray slight ridges of a sweet gum, two chops paired with two spits of the bottle barely rise about the volume of his next footsteps as he passes a white oak, an old loblolly he passes too, at a sourwood he pauses, ponders then the metal and bottle sound off again as they will do before a copse of red maples, and he goes on, and he goes on. Other days the bottle and hatchet lay unused, he goes out with a dibble bar and longleaf seedlings—find a spot, make a hole, plant the seedling not too low, not too high but just right into the ground to give it a chance to become a tree. He baths in a forest that he is bringing down as he sweats after another forest that he wants to raise up.

We leave the woods for the last time emerging behind the barn that sits at the edge of a large clearing on the other side of which we can see Tim’s house. The barn is made of longleaf, ashen gray as all time leached wood becomes, but still dripping resin decades later as only longleaf does in these parts. Tim’s grandfather’s tractor is in the barn, a John Deere from the 50s. It is parked facing the forest which it must have watched day by day succeed from being the fields which it had tilled, harvested, kept low. I wonder what the tractor thinks sitting there looking. Tim respects the lives his forebearers lived, but he does not think that they were good stewards of the land—letting it erode, leaving much debris, stripping the soil of its seed bank to put something in the other kind of bank with the proceeds from tobacco. Though maybe “but” does not fit above, for respecting our ancestor has to mean also criticizing them so that we can see their shortcomings not as a means to seed blame as much as recognize what the present needs in order make grounds for futures in which something will bloom. Tim knows his task will be nowhere near complete at the end of his life—just one lifetime could be spent either trying to fell and clear eighty-six acres of land or planting and tending eighty-six acres of longleaf—but perhaps that is part of the appeal, getting something started that maybe his children and grandchildren will not just remember him by but in way continue to live with him through. Even if just one longleaf that Tim plants survives to the pine’s maximum life expectancy, the Martin’s of the next four hundred years would have a direct witness to him.

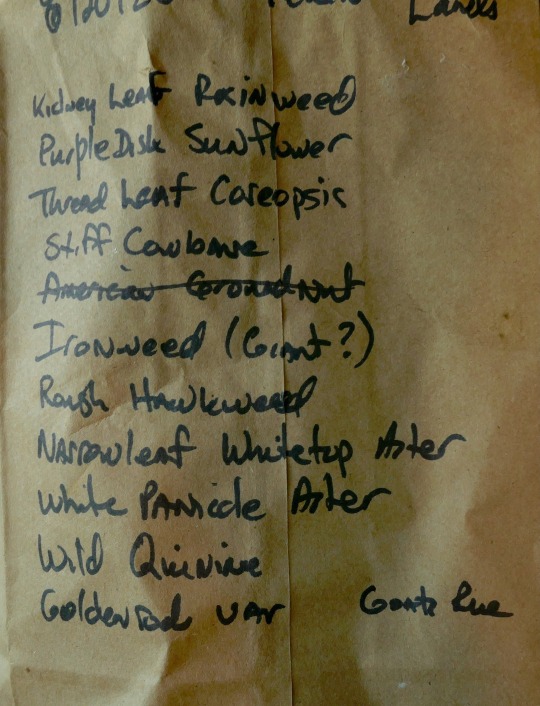

It was half past noon when we returned to his house. Inside, I browsed his bookshelf full of guides on birds, plants, and the cultural history of the sandhills. We sat down and Tim handed me a brown paper bag. Written on the outside were the names of about a dozen plants, all of them associated with longleaf pine savannahs, and on the inside where their seeds and seed pods. Knowing that not much memory remains in his soils, seasonally erased by farming, whenever he can, he collects the seed of forbs and grasses from longleaf lands where that memory still blooms (or blooms anew) and he sows them under the longleaf slowly coming up around his home. A whole garden gathered in a lunch bag awaiting receptive grounds. And that was just one of them. As he had already said, he is doing this work not for a tree but for the forest it made, the forest we unmade, and the forest he is trying to make again, day by day, hack by hack, squirt by squirt, tree by tree...

More Photos

0 notes

Text

Old Tobacco Barn, Martin Family Farm

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barn and Barn Quilt, Martin Family Land

The barn, as the forest which was once around it, is made of longleaf pine, that though long exposed to wind, rain, sun and time, still has a pine smell to it from the remaining resin.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tractor, Martin Family Farm

The tractor in the barn belonged to Tim's mother's father, though I was told even after buying it, he preferred his mule.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bottomland Loblolly Pines, Martin Family Lands

26 notes

·

View notes