Text

The Face of War

Salvador Dalí, The Face of War (1941). Oil on canvas, 64 cm x 79 cm. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam.

Salvador Dalí's The Face of War is a profound commentary on the brutality and psychological impacts of war, masterfully executed by one of the most iconic figures of the Surrealist movement. This blog post explores the historical background, artistic elements, and enduring significance of Dalí's striking painting.

Historical Context and Inspiration

Created in 1940, during a tumultuous period marked by the aftermath of the Spanish Civil War and the ongoing horrors of World War II, The Face of War reflects Dalí's response to the widespread suffering and chaos of the time. The painting was completed during Dalí's exile in the United States, a period during which his work took a notably dark turn, focusing heavily on themes of despair, destruction, and decay.

Visual Analysis: Elements of Horror and Surrealism

The Face of War depicts a disembodied head, its features contorted in agony. The skin appears parched and desiccated, symbolizing the desolation of war. What makes this painting particularly haunting are the smaller faces located in the eye sockets, and mouth, each echoing the central expression of torment and fear. This recursive motif enhances the surreal, nightmarish quality of the artwork, emphasizing the endless cycle of suffering caused by conflict.

The presence of serpent-like creatures surrounding the head adds another layer of symbolism and horror to the painting. These sinuous forms may evoke associations with the biblical serpent, representing temptation, evil, and the fall of humanity. Alternatively, they could symbolize the insidious and destructive nature of war, slithering into every crevice of human existence and leaving devastation in their wake.

The background, a barren landscape devoid of life, further reinforces the theme of desolation. The choice of a muted, earthy palette evokes a sense of decay, making the viewer feel the oppressive weight of war’s aftermath.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Dalí often employed complex symbolism in his works, and The Face of War is no exception. The repeated use of faces may symbolize the pervasive and all-consuming nature of war's impact on the human psyche. Each face potentially represents a soul marred by the horrors of war, trapped in a continuous loop of fear and despair. Similarly, the presence of snake-like creatures adds depth to the painting's allegorical meaning, inviting viewers to contemplate the sinister forces at play in times of conflict.

Contemporary Relevance and Legacy

The Face of War remains painfully relevant today, as it continues to resonate with global audiences amidst ongoing conflicts around the world. Dalí's ability to convey the emotional and psychological scars of war challenges viewers to reflect on the lasting impacts of violence and the human capacity for cruelty. It also serves as a stark reminder of the need for empathy and peace in times of turmoil.

Conclusion: A Mirror to the Soul of Humanity

Salvador Dalí's The Face of War is not just a representation of the artist's fears and anxieties about conflict; it is a powerful statement about the universal consequences of war. It stands as a poignant exploration of the depths of human suffering and a compelling call for reflection on the part of all who engage with it.

Reflect and Respond

How does Salvador Dalí's The Face of War influence your understanding of the role of art in expressing and confronting human emotions and experiences? Does Dalí’s depiction of torment and despair alter your views on how art can be used to address serious and profound issues?

#SalvadorDali#TheFaceOfWar#Surrealism#ArtHistory#WarArt#PsychologicalArt#Dalí#ModernArt#ArtisticExpression#HumanConflict#artblogger

0 notes

Text

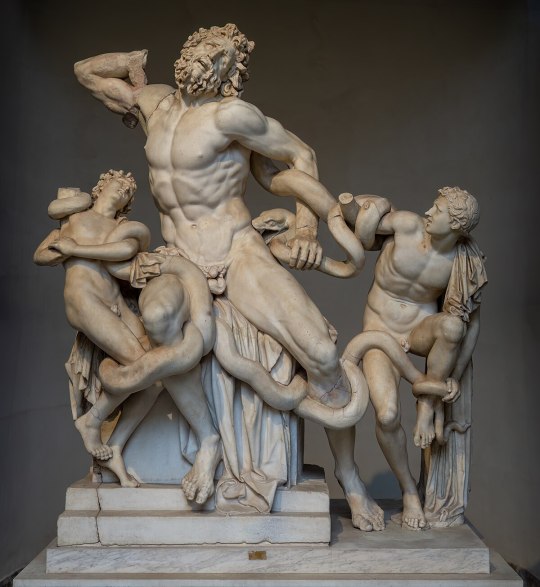

Laocoön and His Sons

Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus of Rhodes, Laocoön and His Sons. Marble, 208 cm × 163 cm × 112 cm. Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

Laocoön and His Sons is one of the most famous and complex sculptures from antiquity, housed today in the Vatican Museums. This masterpiece of Hellenistic art encapsulates the dramatic intensity and emotional depth characteristic of the period, making it a pivotal piece in the study of ancient sculptures. This blog post explores the sculpture's historical context, artistic significance, and the enduring impact it has on viewers and artists alike.

The Tale of Laocoön: Myth and Monument

The sculpture depicts the tragic fate of Laocoön, a priest of Troy, and his two sons, who were attacked by sea serpents sent by the gods. According to legend, Laocoön warned his fellow Trojans against accepting the Greek wooden horse, an act that led to his punishment by the gods who favored the Greeks. The group statue captures the moment of their agonizing death, with the serpents entwining their bodies in a deadly embrace.

Artistic Analysis: Expression and Technique

Laocoön and His Sons is renowned for its dynamic composition and the intense expression of agony. The figures are portrayed in a serpentine pose that suggests movement and struggle, enhancing the dramatic effect. The sculptors, believed to be Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus of Rhodes, masterfully rendered the muscles and emotions of the figures, showcasing their technical prowess and deep understanding of human anatomy and emotion. The sculpture’s scale and the fine detailing of the muscles and sinews contribute to its lifelike appearance and emotional intensity.

Symbolism and Impact on Art History

This sculpture is not just a representation of physical pain but also symbolizes the human struggle against overpowering forces. Its discovery in 1506 near Rome had a profound impact on the Renaissance artists, who were inspired by its expressive power and realism. Michelangelo, in particular, was influenced by its muscular depiction and complex composition, elements that can be seen in his own work.

Contemporary Relevance and Interpretation

Over the centuries, Laocoön and His Sons has been interpreted in various ways, reflecting changing attitudes towards the role of fate and the gods in human life. It continues to inspire contemporary artists and scholars, who see in it themes of resistance, suffering, and the human condition. Its dramatic expression and execution make it a timeless piece that speaks to the fragility and heroism of mankind.

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Human Expression

Laocoön and His Sons remains a pivotal work in the history of art, standing as a monument not only to Hellenistic artistry but also to the timeless themes of struggle and endurance. Its emotional depth and technical excellence continue to captivate and inspire, making it a central piece in the discourse on ancient and modern art.

Reflect and Respond

Considering the intense emotion and dynamic movement captured in Laocoön and His Sons, how do you see this sculpture in relation to modern representations of struggle and resistance in art? Can you think of any contemporary works that evoke a similar sense of drama and emotion?

#LaocoönAndHisSons#AncientSculpture#HellenisticArt#VaticanMuseums#ArtHistory#ClassicalSculpture#MythologyInArt#MichelangeloInfluence#ArtisticExpression#HumanStruggleInArt#artblogger

0 notes

Text

Judith Slaying Holofernes

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (1620). Oil on canvas, 146.5 x 108 cm. Museo Capodimonte, Naples.

Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith Slaying Holofernes stands as one of the most vivid and dramatic works in the realm of Baroque painting, encapsulating themes of courage, justice, and female empowerment. This post delves into the artistic and symbolic nuances of Gentileschi’s iconic painting, offering a deep dive into its historical context, visual analysis, and enduring impact.

The Power and Fury: A Closer Look at Gentileschi's Masterpiece

Artemisia Gentileschi, born in 1593 in Rome, was one of the first women to achieve recognition in the male-dominated world of post-Renaissance art. Judith Slaying Holofernes is often viewed through the lens of Gentileschi's personal history, particularly her experience with sexual assault and the subsequent highly publicized trial. The painting, created in the early 1620s, is interpreted by many as a form of cathartic expression, showcasing her mastery over her traumas and her assailants.

The Art of Contrast: Tenebrism in Judith Slaying Holofernes

The painting depicts the biblical story of Judith, a widow who saves her village from the Assyrian general Holofernes by seducing and then beheading him. Gentileschi’s rendition is remarkable for its intense realism and emotional power. Unlike other contemporary versions of the subject, Gentileschi’s Judith appears strong and resolute in her task, capturing a moment of intense physical and psychological action.

Defiance in the Details: Symbolism in Gentileschi's Narrative

In Judith Slaying Holofernes, Gentileschi aligns herself with Judith, symbolically enacting a narrative of female agency and vengeance. This work is often read as a proto-feminist statement, with Judith’s act representing a broader defiance against patriarchal oppression. The painting challenges traditional gender roles and reflects Gentileschi's own struggles against the societal limitations imposed on women of her time.

Artemisia Gentileschi's Legacy: Reclaiming Space and Narrative

Artemisia Gentileschi's work has experienced a resurgence of interest in recent years, celebrated for its bold thematic content and its reflection of the artist's personal narrative of overcoming adversity. Judith Slaying Holofernes not only contributes to the historical narrative of art but continues to inspire discussions on gender, power, and resilience.

A Canvas of Courage: The Timeless Message of Judith Slaying Holofernes

Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi is not just a depiction of a biblical heroine, but a profound commentary on justice, courage, and the capabilities of women both in art and in life. It remains a powerful image of defiance and autonomy, resonating with audiences centuries after it was painted.

Reflect and Engage

How do you think Judith Slaying Holofernes challenges or reinforces the perceptions of women both in the era it was painted and today? Does the painting's violent imagery detract from or enhance its message of female empowerment?

#ArtemisiaGentileschi#JudithSlayingHolofernes#BaroqueArt#FeministArt#ArtHistory#WomenInArt#PowerfulPaintings#ArtisticExpression#HistoricalArt#ArtAndResistance#artblogger

0 notes

Text

The NewOnes, will free Us

Wangechi Mutu, The NewOnes, will free Us (2019). Bronze. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Wangechi Mutu's sculptures, The NewOnes, will free Us, represent a pivotal moment for both contemporary art and the storied façade of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. These sculptures are the first to adorn the Met’s exterior niches, a space initially intended but never before used for sculpture. In this post, we explore the rich layers of meaning and cultural significance behind Mutu’s work.

Unveiling Modern Caryatids: Mutu's Vision on the Met's Façade

In 2019, Kenyan-American artist Wangechi Mutu was invited to create four sculptures for the Met's façade. Her work, titled The NewOnes, will free Us, consists of four bronze figures that serve as modern caryatids—an ancient architectural form where sculpted female figures replace columns or pillars. These sculptures not only support the physical structure but also carry deep symbolic weight, challenging historical narratives and celebrating transformation and empowerment.

Adornment as Empowerment: The Symbolism of Mutu's Sculptures

The figures are meticulously crafted from bronze, their surfaces textured with patterns that suggest fine jewelry and elaborate headdresses, conveying regality and resilience. Mutu’s caryatids are adorned in such a way that they command respect, reflecting the strength and complexity of women, particularly those from African cultures. This use of traditional adornment techniques highlights the dignity and elevated status of these figures.

Challenging Historical Narratives: Mutu at The Met

Mutu’s sculptures delve into themes of gender, race, and history, with a particular focus on the role of women as both cultural bearers and modern individuals carving new paths. By placing these figures on the façade of one of the world’s leading art institutions, Mutu challenges the traditional Western narrative and integrates African women into a historical dialogue from which they have been largely absent.

The Impact of The NewOnes: A New Precedent for Art in Public Spaces

The installation was widely praised for its aesthetic beauty and its powerful commentary on social issues. As the inaugural artwork for the Met’s façade commission series, Mutu's The NewOnes, will free Us sets a transformative precedent for how art can influence public spaces and cultural institutions toward more inclusive narratives.

Reflecting on Power and Presence: The Lasting Influence of Mutu's Work

Wangechi Mutu’s work is a bold reimagining of the caryatid figure, transforming it into a symbol of empowerment and change. Her sculptures encourage viewers to reconsider the roles traditionally assigned to women in both art and society and to appreciate the dynamic contributions of African cultures to the global historical narrative.

Your Thoughts?

How do you perceive the intersection of art and social change, especially in public and historically significant spaces like The Met?

#WangechiMutu#TheMet#ContemporaryArt#FeministArt#PublicArt#CulturalDialogue#ArtAndSociety#AfricanArtists#SculptureArt#artblogger#arthistory

0 notes

Text

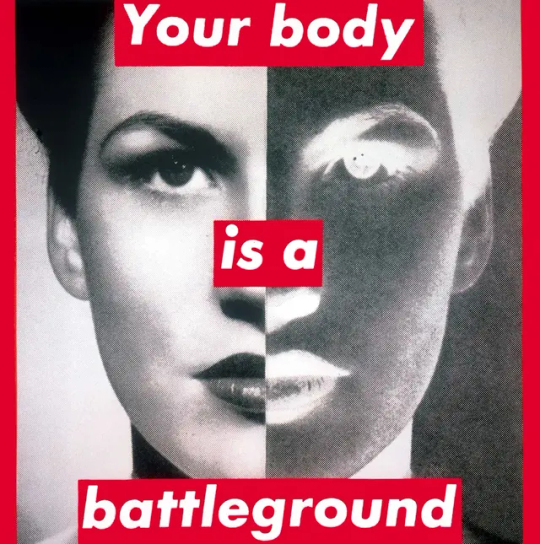

Untitled (Your body is a battleground)

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your body is a battleground) (1989). Photographic silkscreen on vinyl, 284.48 x 284.48 cm.

Barbara Kruger's compelling work Untitled (Your body is a battleground) continues to resonate as a powerful statement in the realm of feminist art. This piece, created for the 1989 Women’s March on Washington, delves deeply into the ongoing debate over women’s bodies and reproductive rights, capturing the enduring struggle through a stark visual medium.

Decoding Kruger's Iconic Visual Statement

Kruger's artwork employs a striking black-and-white photograph of a woman's face, split down the middle into positive and negative exposures. This visual split suggests a dichotomy, reflecting the polarized views on women's autonomy over their own bodies. Overlaying this image are the bold, red words: "Your body is a battleground," a phrase that has become a rallying cry in the fight for reproductive rights and gender equality.

The Power of Symbolism in Feminist Art

Kruger is known for her graphic approach, often merging text with mass media images to challenge viewers and provoke thought. In Untitled (Your body is a battleground), the directness of the textual message combined with the confrontational gaze of the woman’s face compels the audience to consider the personal and political implications of the body in societal debates. The use of red, often associated with danger, power, and passion, enhances the urgency of the message.

Historical Context and Enduring Impact

Created during a time of significant political activism concerning women's reproductive rights, this artwork was part of Kruger’s broader critique of power structures and identity politics. It was not just a piece of art but a part of the visual and textual propaganda used during demonstrations, encapsulating the essence of protest art by blending the boundaries between art and activism.

The Continued Relevance of Kruger's Message

Decades after its creation, Untitled (Your body is a battleground) remains relevant, as debates over reproductive rights continue to be contentious in various parts of the world. Kruger’s work is a reminder of the ongoing struggles and the power of art to influence and reflect societal issues.

Engaging the Viewer: Art as Activism

Barbara Kruger’s work is a poignant exploration of identity, autonomy, and resistance. It challenges viewers to reflect on the implications of viewing the body as a site of conflict and control. As we continue to witness debates surrounding body autonomy and reproductive rights, Kruger's work encourages ongoing dialogue and activism.

Reflect and Respond

What other artworks have you encountered that powerfully address social or political issues? How do they compare to Kruger's method of integrating text and image to communicate a message?

#BarbaraKruger#FeministArt#ContemporaryArt#ArtHistory#VisualAnalysis#ArtActivism#ProtestArt#BodyAutonomy#ReproductiveRights#WomenInArt#PoliticalArt#ArtAsActivism

0 notes

Text

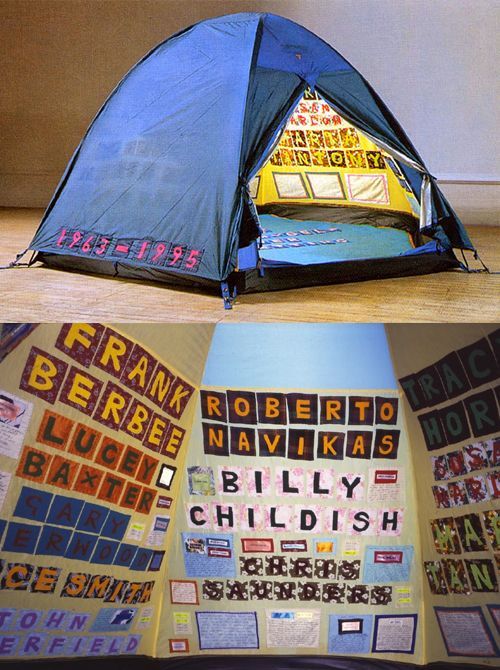

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995

Tracey Emin, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (1995). Fabric, embroidery.

In the constellation of contemporary art, Tracey Emin's provocative oeuvre serves as a beacon of personal and feminist exploration. Among her many works, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 (also known as The Tent) stands out as a landmark in the journey of autobiographical and feminist art. This post delves into Emin's iconic piece through the lens of art history and a woman's perspective, unravelling the layers of intimacy, identity, and rebellion.

Introduction to The Tent:

First unveiled in 1995 at the Minky Manky exhibition at the South London Gallery, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 is a small tent appliquéd with the names of everyone with whom Emin had shared a bed until that point in her life. The list includes lovers, family members, and friends, encapsulating a range of intimate encounters beyond the sexual connotation the title might suggest.

Form and Structure:

The tent, a humble and transient shelter, is transformed into a vessel of profound personal narrative. Its domestic, almost fragile nature contrasts with the boldness of the revelations within. The inside of the tent is a sanctum, each name meticulously handcrafted, inviting viewers into a private emotional landscape. The choice of a tent as the medium challenges traditional art forms, aligning with feminist art practices that embrace everyday objects to convey complex narratives.

Textual Interplay:

The interplay between text and textile within the tent creates a rich tapestry of stories. Each name, carefully stitched, is both a confession and a declaration, marking a departure from impersonal art forms. This interweaving of textuality and materiality foregrounds the feminist emphasis on the personal as political, challenging societal norms around privacy, sexuality, and emotional expression.

Autobiography and Identity:

Emin's work is unabashedly autobiographical, a hallmark of feminist art that seeks to reclaim the female narrative from the margins. The Tent serves not just as a recounting of personal history but as a reclamation of agency over one's body and relationships. It reflects a broader feminist discourse on the ownership of female identity and sexuality, pushing back against patriarchal structures that seek to define and confine women's experiences.

Collective Experience:

While intensely personal, Emin's tent also gestures towards the collective. By including not only sexual partners but also relatives and friends, the work broadens the conception of intimacy. It suggests a shared human experience, resonating with feminist principles of solidarity and the breaking down of public/private dichotomies. Emin's inclusivity invites reflections on the interconnectedness of relationships, both fleeting and enduring, in shaping one's identity.

Reception and Legacy:

Upon its debut, Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995 garnered attention and controversy, emblematic of Emin's career. Some critics dismissed it as narcissistic exhibitionism, while others hailed it as a breakthrough in feminist art. Its destruction in the 2004 Momart warehouse fire only amplified its mythos, preserving its status as a touchstone for discussions around feminist art and personal narrative.

Stitching Connections: What's Your Story?

Inspired by Tracey Emin's journey of intimacy and connection, I invite you to reflect: If you were to create a piece symbolizing your personal connections, what form would it take? Share your ideas and the stories behind them, as we explore the art of living through the lens of our shared and individual experiences.

#TraceyEmin#FeministArt#ContemporaryArt#ArtHistory#PersonalNarratives#ArtisticExpression#IntimacyInArt#WomenInArt#ArtBlog#CreativeConnections

0 notes

Text

The Two Fridas

Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (1939). Oil on canvas, 173.5 cm × 173 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

As an avid enthusiast of art history, Frida Kahlo has always held a special place in my heart. Her bold and deeply personal artworks have captivated me since I first encountered them, igniting my passion for studying art and its ability to convey raw emotion and profound truths. Among her many iconic paintings, The Two Fridas stands out as a powerful testament to Kahlo's resilience and her exploration of identity and emotion in the face of personal turmoil.

The Painting's Context:

Completed in 1939, shortly after Kahlo's divorce from Diego Rivera, The Two Fridas is a poignant reflection of the artist's inner struggles and conflicting emotions during this tumultuous period of her life. The painting portrays two distinct versions of Kahlo, each representing different aspects of her personality and experiences.

The Duality of Identity:

The two Fridas depicted in the painting symbolize the duality within Kahlo herself. On the left, we see the traditional Frida adorned in Tehuana clothing, a representation of her Mexican heritage and cultural identity. This Frida sits with a broken heart exposed, representing her vulnerability and emotional pain following her separation from Rivera. In contrast, the Frida on the right is depicted in modern attire, embodying her independence and strength as a woman.

Symbolism and Imagery:

The imagery in The Two Fridas is rich with symbolism and metaphor. The visible hearts of both Fridas highlight their emotional turmoil, with the heart of the traditional Frida visibly cut and torn open, symbolizing her emotional wounds and vulnerability. The main artery, cut off by surgical pincers, further emphasizes the theme of heartbreak and the potential for emotional destruction. The vein winding around the two Fridas connects their hearts, underscoring their shared pain and emotional bond. Additionally, the miniature portrait of Diego Rivera held by the Frida on the right serves as a profound testament to the complexities of Kahlo's relationship with her husband. It encapsulates the tumultuous nature of their bond, portraying both love and pain intertwined.

The Power of Connection:

Despite their differences, the two Fridas are depicted holding hands, symbolizing a connection between different aspects of Kahlo's identity. This gesture speaks to the artist's resilience and ability to find strength and solidarity within herself, even in moments of profound vulnerability and despair.

Conclusion:

Frida Kahlo's The Two Fridas remains a timeless masterpiece that continues to resonate with audiences around the world. Through its powerful imagery and symbolism, the painting invites viewers to explore themes of identity, resilience, and the complexities of human emotion. As a personal favourite of mine, it serves as a reminder of the transformative power of art to illuminate the depths of the human experience and inspire empathy, understanding, and connection.

Pondering The Two Fridas:

How does Frida Kahlo's The Two Fridas resonate with your own experiences of duality and identity, and what emotions does it evoke in you when you examine its rich symbolism and imagery?

#FridaKahlo#TheTwoFridas#ArtHistory#SymbolismInArt#EmotionalExpression#FeministArt#IdentityInArt#MexicanArt#ArtisticExpression#ArtAnalysis#ArtBloggers

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Splitting

Gordon Matta-Clark, Splitting (1974). Super-8 film, black-and-white and colour, silent, 10:50 min., transferred to video.

Gordon Matta-Clark, trained as an architect at Cornell University, transitioned into an artist renowned for his transformative interventions into derelict urban spaces. Splitting (1974) stands as one of his pioneering works, where he sliced a suburban New Jersey house in two, creating a radical sculptural environment that challenged traditional notions of architecture and space.

A Monumental Act of Subversion:

In the economically depressed and crime-ridden New York City of the 1970s, abandoned buildings were abundant. Matta-Clark's artistic vision led him to explore these neglected structures, seeking to unearth hidden narratives and possibilities within them. Splitting emerged from this exploration, as he received permission from art dealer Holly Solomon to carve into her suburban New Jersey house, slated for demolition.

The Artistic Process Unveiled:

With the assistance of craftsman Manfred Hecht and other helpers, Matta-Clark executed his audacious plan. Using a power saw, they bifurcated the house, meticulously jacking up one side to create a slender central gap, allowing sunlight to filter into the newly revealed spaces. The resulting sculptural environment disrupted conventional architectural forms, inviting viewers to reconsider their relationship with built environments.

Revealing New Vistas and Passages:

Matta-Clark's "cuttings" series, including Splitting, challenged the established boundaries of architecture, merging traditional sculptural elements with contemporary concerns of urban decay and social structures. By slicing shapes into walls and floors, he transformed stagnant spaces into dynamic vistas, liberating individuals from suburban isolation and revealing the hidden layers of domesticity.

The Temporal Nature of Artistic Intervention:

Despite its monumental impact, Splitting was destined to be ephemeral. Demolished three months later to make way for new apartments, it exists now primarily through documentation: photographs, sketches, an artist's book, and a film capturing the transformative act of architectural-sculptural performance. Matta-Clark's legacy lives on not only in the physical remnants of his interventions but also in the enduring dialogue they provoke about the nature of art and space.

Unravelling Spatial Perspectives:

How does Gordon Matta-Clark's Splitting challenge your perceptions of architecture and space, and what implications does it hold for contemporary discussions about urban development and artistic intervention?

#GordonMattaClark#Splitting#UrbanIntervention#ArchitecturalSubversion#ArtisticTransformation#SpatialExploration#EphemeralArt#ContemporaryArt#ArtAndArchitecture#SocialCommentary#UrbanDecay#ArtisticInnovation#ArtHistory#ArtBloggers

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Progress of Love: The Meeting

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love: The Meeting (1771 - 1773). Oil on canvas, 317.5 x 243.8 cm. THE FRICK COLLECTION.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard's The Progress of Love: The Meeting, painted between 1771 and 1773, is a captivating portrayal of a clandestine encounter, capturing the essence of love in its most intimate and secretive form. This analysis delves into the rich history and intricate symbolism of the painting, shedding light on its significance within the context of both art history and the tumultuous era of Louis XV.

A Glimpse into the Realm of Love:

Fragonard's painting is part of a larger series commissioned by the Comtesse du Barry, the last mistress of Louis XV, for a pleasure pavilion designed by architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. The series, known as The Progress of Love, traces the evolution of romantic relationships through four distinct stages: from flirtation and courtship to consummation and finally to the serene bliss of lasting love. The Meeting represents the second stage, depicting a furtive rendezvous between lovers amidst the lush foliage of a garden.

Intrigue and Intimacy:

The painting exudes an aura of secrecy and intimacy, as the lovers steal a moment away from prying eyes. The male figure, dressed in a distinctive red coat, scales the garden wall with agility and determination, his gaze fixed on his beloved waiting below. The female figure, bathed in soft light, reaches out to him with longing, her expression a mix of anticipation and apprehension. The composition brims with tension and emotion, inviting viewers to immerse themselves in the clandestine romance unfolding before them.

A Story of Rejection and Redemption:

Despite the exquisite beauty and emotional depth of Fragonard's masterpiece, the Comtesse du Barry ultimately rejected the series, perhaps due to perceived resemblances between the red-coated lover and Louis XV or the paintings' departure from the neoclassical aesthetic favoured by Ledoux. Yet, this rejection did not diminish the significance of Fragonard's work. After two decades in the artist's possession, the series found a new home in a cousin's villa in southern France before eventually passing through the hands of notable collectors like J. P. Morgan and ultimately landing in the esteemed Frick Collection in 1915.

Unlocking the Symbolism:

The Meeting is more than just a depiction of a romantic encounter; it is a tableau rich in symbolism and allegory. The garden setting, with its lush greenery and blooming flowers, symbolizes fertility and growth, while the clandestine nature of the meeting speaks to the forbidden nature of the lovers' relationship. The figures themselves embody the timeless themes of desire, longing, and the pursuit of true love, inviting viewers to reflect on their own experiences of romance and passion.

Decoding Desire: Unraveling Fragonard's Intriguing Emotions

In Fragonard's "The Progress of Love: The Meeting," what subtle details and emotions do you think the artist intended to convey, and how do these elements contribute to the overall narrative of the painting?

#Fragonard#TheProgressOfLove#TheMeeting#ArtHistory#18thCenturyArt#FrenchArt#LoveInTheArts#RomanticEncounter#SymbolismInArt#EmotionalExpression#ArtAnalysis#BaroquePainting#ArtisticIntrigue#VisualNarratives#ArtBloggers

0 notes

Text

The Entombment of Christ

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, The Entombment of Christ (1603-04). Oil on canvas, 300 × 203 cm. Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City.

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio's The Entombment of Christ, painted between 1603-04, stands as a testament to the artist's mastery of chiaroscuro and his ability to infuse religious subjects with raw emotion and intense realism. In this analysis, we delve into the compelling narrative and artistic techniques that make The Entombment of Christ a cornerstone of Baroque art.

The Drama of Grief and Devotion:

The Entombment of Christ captures the poignant moment of Christ's body being lowered into the tomb after the crucifixion. Caravaggio's composition draws the viewer into the scene, where figures mourn and console one another amidst the harsh realities of death. The central figure of Christ, with his lifeless body, becomes the focal point of the painting, surrounded by grieving disciples and mourners. Caravaggio's portrayal eschews idealized depictions, opting instead for a visceral and emotionally charged scene that resonates with viewers on a deeply human level.

Chiaroscuro and its Emotional Impact:

Caravaggio's masterful use of chiaroscuro, the contrast between light and dark, heightens the emotional intensity of The Entombment of Christ. Deep shadows and stark highlights create a sense of depth and drama, emphasizing the weight of grief and the solemnity of the moment. The interplay of light and shadow draws attention to the figures' expressions, casting them in a dynamic play of emotions that range from despair to quiet resignation.

Realism and Relatability:

One of Caravaggio's hallmarks is his commitment to realism, evident in the meticulous attention to detail and the lifelike portrayal of the human form in The Entombment of Christ. The figures' faces bear the marks of sorrow and exhaustion, their gestures and postures conveying a profound sense of loss and compassion. Caravaggio's ability to capture the human experience in all its complexity invites viewers to empathize with the scene and reflect on the universal themes of suffering, redemption, and hope.

A Testament to Caravaggio's Genius:

The Entombment of Christ exemplifies Caravaggio's revolutionary approach to art, characterized by his rejection of idealized conventions in favour of raw emotion and stark realism. The painting's impact lies not only in its technical brilliance but also in its ability to transcend the boundaries of time and culture, speaking to audiences across centuries with its timeless portrayal of human emotion and spirituality.

Engagement Question:

How does Caravaggio's portrayal of grief and devotion in The Entombment of Christ resonate with you personally, and what aspects of the painting do you find most compelling or thought-provoking?

#Caravaggio#BaroqueArt#ArtHistory#ItalianArt#Chiaroscuro#RealismInArt#ReligiousArt#DramaticRealism#EmotionalExpression#Masterpiece#ArtisticGenius#VisualNarratives#ArtCritique#ArtAnalysis#MuseumArt#ArtAppreciation#TheEntombmentOfChrist

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Olympia

Édouard Manet, Olympia (1863). Oil on canvas, 130.5 cm × 190 cm. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Édouard Manet's Olympia, painted in 1863, stands as a pivotal work in the history of art, not only for its radical departure from traditional representations of the female nude but also for its confrontation with societal norms and the role of women within them. This analysis explores Olympia in depth, highlighting its significance and the controversy it sparked upon its debut.

Olympia and the Challenge to Convention:

Manet's Olympia depicts a nude woman, reclining, staring directly at the viewer with a confrontational gaze. Unlike the passive, idealized nudes of earlier artworks, Olympia's direct gaze and the presence of a black cat at her feet were seen as shocking. Her hand firmly covers her sexuality, not in a gesture of modesty, but as a display of control and autonomy. This portrayal was a stark contrast to the accepted depictions of female nudes as objects of male desire.

Comparison with Titian's Venus of Urbino:

To fully appreciate Manet's revolutionary approach, one must consider Titian's Venus of Urbino (1534), a work that Manet referenced in Olympia. Titian's Venus, also reclining nude, engages the viewer with a softer gaze, her hand passively resting near her pelvis, surrounded by symbols of marital fidelity and domesticity. Unlike Olympia, Venus's environment and demeanour suggest an invitation rather than a confrontation. The comparison highlights Manet's departure from portraying the female subject as an object of desire to a figure of power and defiance.

The Name 'Olympia' and Its Implications:

The name 'Olympia' itself was loaded with connotations. In the Paris of Manet's time, 'Olympia' was a name often associated with prostitutes, adding another layer of scandal to the painting's reception. This choice of name was not accidental; it was a deliberate commentary on the commodification of women's bodies and the blurred lines between respectability and sexuality in 19th-century society. By naming his subject 'Olympia', Manet directly challenged the viewer to confront their preconceptions and the societal norms dictating the representation and treatment of women.

Controversy and Legacy:

Upon its exhibition, Olympia was met with outrage and ridicule, criticized for its "vulgar" subject matter and "unfinished" style. However, this criticism failed to recognize the depth of Manet's critique of societal and artistic norms. Today, Olympia is celebrated for its bold defiance of traditional art, its pivotal role in the development of modern art, and its complex commentary on gender, power, and the gaze.

Olympia's Glance: A 19th-Century Rebellion?

In light of Olympia's unflinching gaze and assertive posture, how do you interpret her representation in the context of 19th-century societal expectations of women?

#Manet#Olympia#ArtHistory#FrenchArt#19thCenturyArt#FemininityInArt#ArtRebellion#EdouardManet#Masterpiece#ArtControversy#ModernArt#ClassicalArtReimagined#ArtAndSociety#FemaleGaze#ArtisticRevolution#MuseeDOrsay#ArtBloggers#ProvocativeArt#ArtCritique#CulturalDialogue

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ophelia

Sarah Bernhardt, Ophelia (n.d.). White marble in a wood frame, 70 x 59 cm. Private collection, Normandy, France.

In the realm of art and literature, few scenes are as hauntingly captivating as Ophelia's tragic demise in William Shakespeare's Hamlet. Sarah Bernhardt, celebrated for her unparalleled prowess on the stage, extends her artistic expression into the medium of sculpture with her rendition of Ophelia. This piece, a rare surviving work signed by Bernhardt, offers a unique visual exploration of one of literature's most poignant figures.

A Fusion of Art and Tragedy:

Bernhardt's Ophelia is not merely a sculptural representation; it is a narrative frozen in marble. Inspired by Shakespeare's vivid depiction of Ophelia's final moments, Bernhardt captures the essence of the character's tragic end through the medium of high relief. The sculpture portrays Ophelia in a bust form, her head elegantly turned, eyes closed, as if in peaceful resignation to her fate.

The Garland of Flowers:

Adorned with a garland of flowers, the sculpture's Ophelia is enveloped by water that seamlessly merges with her tresses. Bernhardt’s attention to detail is manifest in the intricately carved flowers and the delicate waves of the 'glassy stream', creating a texture that contrasts strikingly with the smooth, bulging form of Ophelia's exposed breast. This duality of texture highlights the sculpture's technical mastery and artistic depth.

A Moment Between Life and Death:

Though depicted at the moment of her death, Bernhardt's Ophelia exudes an undeniable eroticism through her sensuous open-mouthed expression, overt nudity, and languid pose. This portrayal suggests not despair but an ecstatic consummation, presenting death not as a moment of loss but as a profound, albeit tragic, fulfillment. It's a bold interpretation that challenges traditional readings of Ophelia's character, suggesting a deeper, perhaps more complex relationship between the heroine and her fate.

Bernhardt's Artistic Legacy:

Sarah Bernhardt's Ophelia stands as a testament to her multifaceted talent and her ability to traverse the worlds of acting and sculpture with equal finesse. The sculpture serves not only as a memorial to Ophelia's tragic story but also as a reflection of Bernhardt's own interpretive genius and her capacity to imbue marble with the breath of life and emotion.

Reflecting on Ophelia:

In Bernhardt's Ophelia, we are invited to reconsider the narrative of the doomed heroine, seeing her not as a victim of circumstance but as a figure of complex emotional and existential depth. The sculpture asks us to ponder the thin line between life and death, the beauty found in the tragic end, and the eternal resonance of Shakespeare's work through the lens of Bernhardt's sculptural vision.

Your Perspective:

How does Sarah Bernhardt's sculptural interpretation of Ophelia challenge or enrich your understanding of the character? Does this portrayal alter your perception of Ophelia's final moments as an act of despair or an embrace of the inevitable?

#SarahBernhardt#Ophelia#SculptureArt#Hamlet#ShakespeareArt#MarbleSculpture#ArtHistory#FrenchArtists#TheatreAndArt#LiteraryArt#TragicHeroine#RenaissanceArt#ClassicLiterature#ArtisticExpression#WomenInArt#Sculptors#ArtBloggers#VisualNarratives#ArtAndLiterature

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le Miracle de Saint Just

Peter Paul Rubens, Le Miracle de Saint Just (circa 1633). Oil on canvas. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux.

In the rich tapestry of baroque art, Peter Paul Rubens' 'Le Miracle de Saint Just' (The Miracle of Saint Justus), painted around 1633, stands as a remarkable narrative painting that encapsulates the fervor and intensity of religious storytelling of the time. This artwork not only showcases Rubens' mastery over color and form but also delves deep into the miraculous tale of Saint Justus, inviting a reflection on faith, sacrifice, and the divine.

Who Was Saint Justus?

Saint Justus' story is set against the backdrop of the Roman Empire under Emperor Diocletian's reign, a period marked by Christian persecution. The narrative unfolds as Justus, alongside his father and uncle, embarks on a perilous journey to France, aiming to rescue a relative facing persecution for their Christian faith. Their mission takes a dramatic turn when Justus is captured by Roman soldiers. Despite the grave threat to his life, Justus confesses his Christian beliefs. When pressed to betray his father and uncle's whereabouts, he refuses, leading to his execution. A testament to his unwavering faith, Justus' body performs a miracle post-mortem, picking up his severed head and continuing to speak, a phenomenon that leads to the conversion of pagan onlookers. This story of steadfast faith and divine intervention is vividly captured in Rubens' painting.

Rubens' Artistic Vision:

Rubens, a towering figure in baroque art, brings the tale of Saint Justus to life with his dynamic composition, rich colour palette, and emotive figures. His ability to convey the intensity of Justus' martyrdom and the subsequent miracle with such vigour and depth is unparalleled. The painting is not just a visual representation but a narrative journey that encapsulates the essence of martyrdom and the power of divine faith.

Symbolism and Interpretation:

In 'Le Miracle de Saint Just,' Rubens explores themes of sacrifice, faith, and the divine through the lens of Saint Justus' martyrdom. The miraculous act of Justus speaking after death serves as a powerful symbol of faith's triumph over persecution and death. Rubens' depiction invites viewers to contemplate the nature of belief, the sacrifices it may entail, and the miracles that faith can bring forth.

The Power of Expression in Rubens' Canvas:

Rubens' skill in 'Le Miracle de Saint Just' extends notably to the depiction of facial expressions, capturing the story's emotional essence. Saint Justus, portrayed with a peaceful resolve, contrasts sharply with the bewildered and astonished onlookers, their faces a canvas of awe and fear. This juxtaposition of serenity and turmoil enhances the narrative, inviting viewers to engage deeply with the themes of faith and the miraculous.

Expressions Unveiled: Your Thoughts?

How do the powerful expressions in 'Le Miracle de Saint Just' by Rubens affect you, drawing you into the painting's narrative without words?

#PeterPaulRubens#LeMiracleDeSaintJust#BaroqueArt#ArtHistory#Rubens#SaintJustus#MartyrdomInArt#DivineMiracles#HistoricalArt#ExpressionInArt#ArtAndEmotion#Masterpieces#MuseumDesBeauxArts#ArtAnalysis#NarrativePainting#BelgianArt#RenaissanceArt

0 notes

Text

The Rape of Europa

Titian, The Rape of Europa (1560–1562). Oil on canvas. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Titian's The Rape of Europa, painted circa 1562, is a masterful representation of a classical mythological story, imbued with the Venetian painter's signature use of colour and emotion. This analysis explores the various dimensions of this celebrated Renaissance artwork.

Mythological Context:

The painting depicts the abduction of Europa, a Phoenician princess, by Zeus, the king of the gods in Greek mythology. In this tale, Zeus transforms himself into a white bull to seduce and abduct Europa. Titian captures the moment of abduction, portraying a blend of fear, surprise, and eventual resignation in Europa's expression as she is carried away across the sea.

Artistic Technique:

Titian is renowned for his virtuosic use of colour, and The Rape of Europa is a prime example. The painting is characterized by vibrant hues and dynamic brushstrokes, creating a sense of movement and drama. The contrast between the serene blues of the sea and sky and the intense reds and whites of Europa and the bull heightens the emotional impact of the scene.

Symbolism and Interpretation:

Europa's abduction can be seen as symbolic of the clash between civilization (Europa) and unbridled natural force (Zeus as a bull). Furthermore, the painting reflects the Renaissance fascination with classical mythology as a means to explore human emotions and experiences.

Composition and Perspective:

Titian's composition in The Rape of Europa is dynamic and fluid. Europa is diagonally positioned, which, coupled with the rearing bull, gives the scene a sense of imminent action and instability. The inclusion of the onlookers, horrified at the scene unfolding, adds a layer of narrative depth and perspective to the painting.

Contemplating the Title: The Rape of Europa

The term 'rape' in the title of Titian's painting, derived from the Latin 'raptus,' primarily signifies 'abduction' or 'carrying away.' In the context of Renaissance art and classical mythology, it often refers to the abduction of a person, typically involving divine or heroic figures. The scene depicted by Titian focuses on the dramatic and transformative aspects of the myth, capturing Europa's fear and astonishment at her realization and journey to a different destiny.

Reflecting on Historical Perspectives:

Understanding The Rape of Europa necessitates a consideration of the historical and cultural context in which Titian worked. The depiction of such stories was often imbued with layers of meaning, exploring themes of power, transformation, and the divine.

Your Interpretation:

In viewing The Rape of Europa, how do you perceive Titian's interplay of emotion and mythology? Does the painting evoke certain feelings or thoughts about the way classical stories are portrayed in Renaissance art?

#Titian#TheRapeOfEuropa#RenaissanceArt#MythologyInArt#ItalianMasters#ArtHistory#ClassicalMythology#VenetianPainting#ArtAnalysis#MasterpieceExploration#ArtBlogger#TitianArt#RenaissancePainting#CulturalInterpretation#HistoricalArt#MythAndArt

0 notes

Text

Fringe

Rebecca Belmore, Fringe (2007). Photography printed on canvas. Global Contemporary Art.

Rebecca Belmore's Fringe is a deeply moving and thought-provoking piece that addresses themes of trauma, healing, and history, particularly in the context of indigenous peoples and women. This analysis delves into the various elements that make Fringe a significant work in contemporary art.

Artistic Concept:

Fringe is a striking piece, depicting a life-sized photograph of a reclining Indigenous woman, her back turned to the viewer. A striking feature of the work is a large wound on her back, from which red threads resembling blood, or perhaps fringe, flow down. This wound and its vivid depiction are central to understanding the piece's emotional and historical depth.

Symbolism and Representation:

The wound in Fringe is symbolic of the historical and ongoing trauma experienced by Indigenous communities, particularly the women. It speaks to the violence inflicted upon these communities and the scars – both physical and emotional – that they bear. The flowing threads can be interpreted as a symbol of bleeding, representing ongoing pain, or as fringe, suggesting a cultural connection and resilience.

Medium and Technique:

Belmore's choice of medium – photography printed on canvas, with the addition of the three-dimensional element of the threads – bridges traditional and contemporary art forms. The use of these materials emphasizes the raw and tactile nature of the subject matter, making it both visually striking and emotionally resonant.

Contextual Importance:

Fringe is not just a piece of art; it is a statement about the resilience and suffering of Indigenous peoples. In the context of Belmore's broader work, which often tackles issues of social and political importance, Fringe stands out as a particularly poignant commentary on the intersection of gender, history, and colonialism.

Reflecting on Trauma and Resilience:

How does Fringe by Rebecca Belmore resonate with your understanding of art as a medium for addressing historical and cultural trauma? What emotions or thoughts does this piece evoke in you about the experiences of Indigenous peoples?

#RebeccaBelmore#Fringe#IndigenousArt#ContemporaryArt#ArtAndHistory#CulturalTrauma#ArtAsActivism#CanadianArt#IndigenousVoices#ArtisticExpression#WomenInArt#HistoricalArt#ArtBlogger#ArtForChange

0 notes

Text

A Forest of Lines

Pierre Huyghe, A Forest of Lines (2008). Art Installation. Concert Hall at Sydney Opera House, 16th Biennale of Sydney.

Pierre Huyghe's installation A Forest of Lines transports viewers into a realm where art and environment intersect, blurring the lines between natural and constructed worlds. This work, displayed at the Sydney Opera House in 2008, is a compelling exploration of space, perception, and the relationship between nature and human creation.

Conceptual Framework:

A Forest of Lines transformed the iconic Sydney Opera House into a dense, immersive forest. Huyghe planted 300 live trees within the concert hall, creating a juxtaposition of natural elements within a man-made, cultural space. This fusion invites viewers to reconsider their perceptions of familiar environments and the boundaries between natural and artificial spaces.

Spatial Dynamics:

The installation challenged traditional notions of space utilization in art. By bringing the outdoors inside, Huyghe disrupted the conventional function and atmosphere of the concert hall. The audience navigated through this forest, experiencing a shift in their usual interaction with both nature and architectural space.

Sensory Experience:

The multi-sensory experience of A Forest of Lines is central to its impact. The visual spectacle of trees indoors, combined with the smells and sounds of a forest, created an immersive experience that transcended visual art, engaging the audience on multiple sensory levels.

Environmental and Artistic Dialogue:

Huyghe's work often engages with environmental themes, and A Forest of Lines is no exception. The installation prompts reflection on our relationship with the environment and the ways in which we compartmentalize nature in our urban and cultural spaces. It also explores the role of art in mediating and redefining this relationship.

Temporal Elements:

The temporary nature of the installation, like a fleeting natural phenomenon, left a lasting impression on its viewers. This ephemerality underscores themes of impermanence and transformation, both in nature and in human experience.

Nature Meets Art: What's Your Take?

In what ways does Pierre Huyghe's A Forest of Lines alter your perception of space and the intersection between nature and human-created environments?

#PierreHuyghe#AForestOfLines#ContemporaryArt#InstallationArt#ArtAndNature#SydneyOperaHouse#ArtisticSpace#EnvironmentalArt#ArtPerception#InteractiveArt#ModernArt#ArtInnovation#SensoryExperience#ArtBlogger#NatureInArt

0 notes

Text

Jupiter and Io

Antonio da Correggio, Jupiter and Io (1532–1533). Oil on canvas, 163.5 cm × 70.5 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Antonio Allegri da Correggio's Jupiter and Io, a masterpiece from the High Renaissance, offers a fascinating glimpse into the amalgamation of divine mythology and sensual expression. This analysis seeks to explore the various facets of this captivating work, painted circa 1530.

Mythological Backdrop:

The painting is based on a tale from Ovid's Metamorphoses, where Jupiter, the king of the gods, seduced Io, a mortal woman. Correggio portrays this mythological encounter with a blend of divine grandeur and intimate tenderness. Jupiter, disguised as a cloud, envelopes Io, depicting the moment of their union.

Artistic Technique and Style:

Correggio is renowned for his skillful use of sfumato, a technique that creates soft, gradual transitions between colours and tones, akin to smoke or vapor. This technique is masterfully employed to render the cloud form of Jupiter, merging seamlessly with Io’s figure. The fluidity and delicacy of his brushwork lend an ethereal quality to the scene, enhancing its dreamlike and sensual ambiance.

The Sensuality of the Divine:

A striking aspect of Jupiter and Io is its explicit sensuality. Correggio does not shy away from portraying a bold, erotic theme, a daring choice for his time. Io's blissful expression and the tangible depiction of her embrace with the cloud illustrate a harmonious blend of the human and divine realms.

Symbolism and Interpretation:

The painting is rich in symbolism. The cloud not only represents Jupiter's disguise but also suggests the elusive and omnipresent nature of the divine. Io’s yielding posture and closed eyes might symbolize the surrender to higher powers or the overwhelming nature of divine encounters.

Contextual Significance:

Created during the High Renaissance, a period known for its humanistic approach to art, Jupiter and Io reflects the era's fascination with classical mythology and its exploration of human emotions and experiences, even in divine narratives.

Myth and Sensuality: Your View

How does Correggio’s depiction of the divine in Jupiter and Io resonate with your understanding of mythology and art? Do you see this painting as a celebration of love and sensuality, or as a reflection of the power dynamics between the mortal and the divine?

#Correggio#JupiterAndIo#RenaissanceArt#MythologyInArt#ItalianMasters#ArtHistory#SensualArt#DivineArt#ClassicalMythology#HighRenaissance#ArtAnalysis#MasterpieceExploration#ArtBlogger#CorreggioArt#SfumatoTechnique#ArtAndMythology

0 notes