HI! I'm a geological sciences student! I like talking about what I learn as I learn it, so why don't you join me on this journey to learning more about the world? ^_^

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I know its supposed to be a joke but the theory of Pangea/continental drift was first developed in 1912 by Alfred Wegener in The origin of continents. It was highly controversial at the time but was later proved in the 50s when we discovered paleomagnetism, and it slowly became more common knowledge in the second half of the century.

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

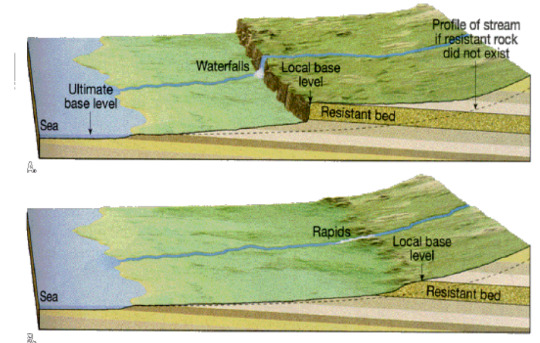

Knickpoints, base level, and waterfalls

I won't go into detail about hydraulics, but hi! Let's talk about rivers a little!

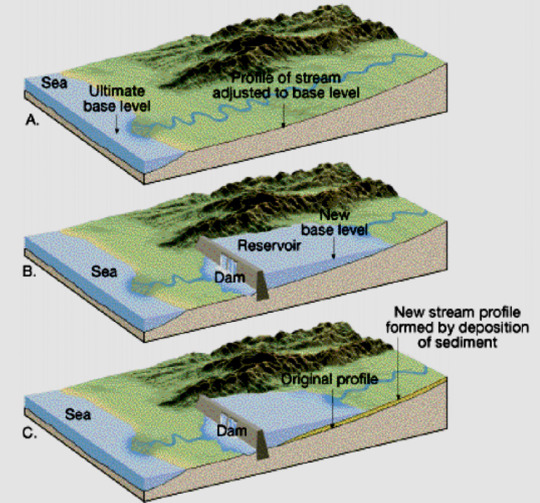

Base level: in geomorphology, the "base level" is the lowest point at which erosion can occur, or in the case of rivers, it's the lowest altitude at which a river can flow. A common base level for most rivers is the sea, though for some of them it might be a lake, a different river that the first river is a tributary to, or a dam.

The base level for any given river can change through time, since sea levels can vary, dams can be built, etc. A variation in base level, causes a variation in the river's energy, which can lead to more erosion, or more sediment deposition depending on if the river has more or less energy than before.

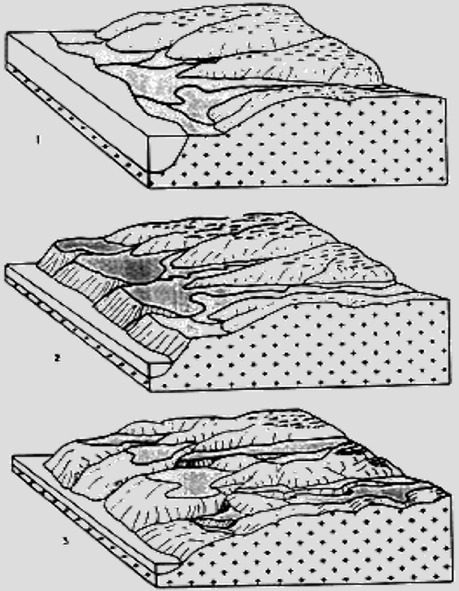

Here are two examples, the first is of a river whose base level dropped lower, it gained more energy and started eroding the substrate more, the second one is of a river whose base level was raised higher, and it started depositing more sediment to compensare with lowered energy.

This was an introduction to explain the concept of base level, now let's move on to knickpoints.

Knickpoint: a sudden and sharp variation of a river's slope, often leading to the formation of waterfalls and/or lakes. Some reasons why a knickpoint might form are: base level drop, tectonic activity, or a later of erosionally resistant rock:

There are generally two types of knickpoints: migrating and fixed.

Migrating knickpoints are mainly caused by base level drop and tectonic activity. They are called migrating because due to the erosion that the river applies on the substrate, the knickpoint is able to travel upstream. In the case of a base level drop type of knickpoint that affects an entire hydrography basins, usually the baisin will have all of its migrating knickpoints at the same altitude:

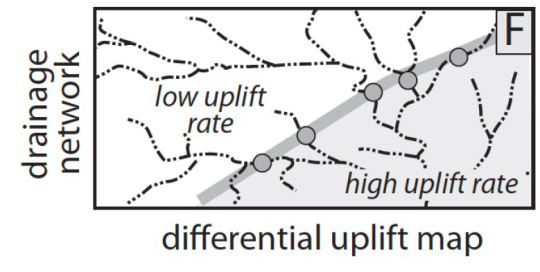

Sometimes, knickpoints are caused by differential uplift (two areas within a hydrographic basin are subject to different rates of tectonic uplift), and this causes a "barrier" of knickpoints that can easily be drawn within the baisin:

Fixed knickpoints instead are caused mostly by the presence of a layer of erosionally resistant rock, as it is something that the river cannot easily erode through, and will remain fixed.

Waterfalls can form from any of these kinds of knickpoints, it really depends on the river's erosion ability, it's energy, it's mass flow rate, the kind of sediments it carries, etc.

#geomorphology#original post#geology#this one was kinda dumb lol sorry but this exact topic kicked my ass yesterday

45 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hiiii I'm very new at geology and I wanted to know if there are any (not too expensive) books you would recommend for beginners?

Okay I've gotten this question before but I feel like I finally answer it properly.

I am personally building a gdrive full of free resources. It's very empty right now but you can find it in my pinned post.

"Introducing Geology: a guide to the world of rocks" by Graham Park is currently on my TBR list. I have not personally read it but it has been recommended to me as a book for beginners + I have read a book in the same series called "Introducing Geomorphology" and found it very well written and easy to understand, so I'm positive that this one might be just as good. Either way it's pretty cheap, I don't know where you live but for me both books are in the 12-15€ range so you should be able to get your hands on a copy fairly easily.

I'm going to say though, even though I have not read it, I have to assume that a basic knowledge of chemistry and maybe physics is required to understand that book simply because geology is very much based in the fundamentals of chemistry. If you do purchase it and some concepts are unclear to you, feel free to come back here and send some asks about it!

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I just found your blog and I LOVE it! Yay rocks!

One question, if it's not too personal, what university do you study at? Just curious :)

Yay! Oh that makes me glad :)))

Not a problem, I don't mind disclosing it. I study at Sapienza University in Rome, Italy!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I honestly want to know what people think, so tell me...

Explanation:

Earth physics: pretty much just earthquakes

Mineralogy: specifically the study of minerals and crystals

Paleontology: the study of non-human biological remains

Petrology/petrography: how rocks are formed, the processes, how do you look at a rock and figure out how it was born

Geomorphology: landforms and the processes that originate them

Geological risks: approaching geology from the perspective of making human life safer

I haven't included all geological sciences (volcanology, hydrogeology, geochemistry etc) because this is for me to see what fields I can personally expand more into, and I only listed the ones I feel comfortable talking about.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

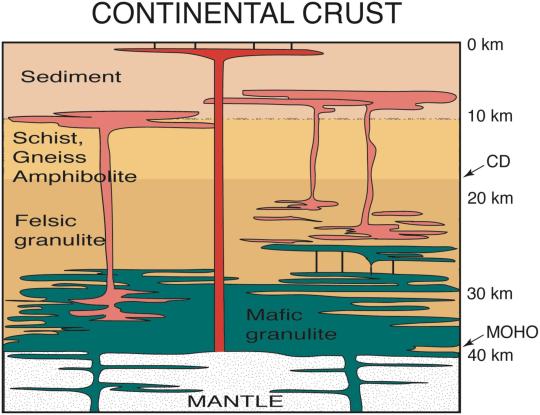

whats more unpredictable about continental crust?

The composition of continental crust really varies significantly because of many reasons, mostly because it's subject to both sedimentation and erosion so we already don't have one type of rock that is uniform to the surface of continental crust in the same way that we know the entire oceanic crust is covered in a layer of mostly clay and less commonly limestone sediments.

The continental crust is also a lot thicker with a larger range than the oceanic crust, between 20 and 70 km of depth with an average of about 36 km, which means there are a lot more of processes happening inside and the 50 km of range really differentiates how the crust is affected by pressure and temperatures.

We know more or less what the average composition of the crust is (granite, which is an intrusive rocks but much richer in quartz than the gabbro i mentioned in the post) and in general it's high in silicates and low in maphic minerals, the complete opposite of oceanic crust.

It's also a lot more difficult to dig into, because of that significant thickness: you might have heard about how this spring Project Mohole successfully drilled into the deepest parts of the oceanic crust, pretty much reaching the mantle - while we have barely managed to drill a hole that reaches 1/3 of the continental crust. Because of this we also know significantly less about the continental crust.

I'll leave a graph about how we think the continental crust might look like in a very idealized and hypothetical rendition:

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

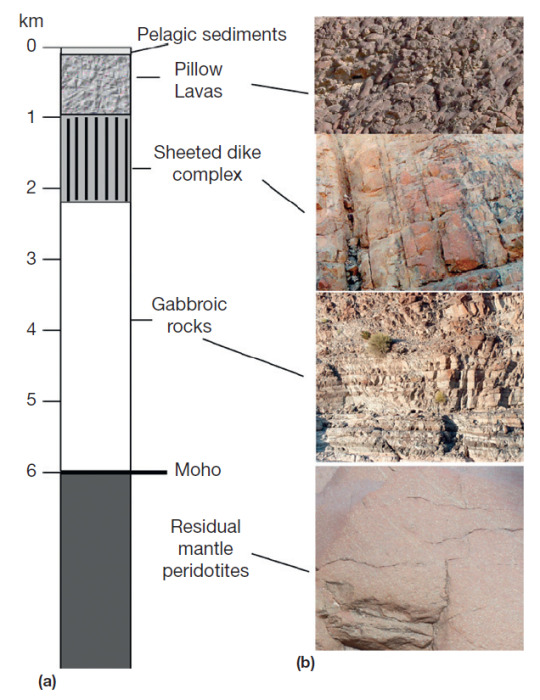

Under the oceans

Have you ever wondered what exactly lies at the bottom of the ocean? Or, well, under the bottom of the ocean.

The oceanic crust is relatively thin, only between 2 and 10 km at most, with a global average of 7 km. Its density is between 2.8 and 3.2 g/cm^3 and it is theorized that it cannot be older than 250 millions of years, as oceanic ridges continuously form new crust, while the earth "reclaims" parts of it through subduction.

What is more interesting to me though, is what is actually inside of it.

The "Ophiolitic Sequence" is a reoccurring series of rock formations that can be consistently found through the oceanic crust. As opposed to its continental counterpart, the oceanic crust is relatively predictable from what is known, and usually the same formations can be found in the same order from surface to mantle.

Keep in mind that all of these formations aren't always found under the oceanic crust, in some areas some of them may be missing.

This is a very idealized rendition of what the ophiolitic sequence might look like:

From top to bottom we have:

Pelagic sediments: at the deepest parts of the ocean, this means mostly clay sediments and silicates. Rarely you can find limestone sediments in the ocean, especially at significant depths.

Pillow lavas: the most superficial ignenous formations, formed by lava emerging from the oceanic ridges. They care called this way because when the lava emerges, it comes into contact with water - water applies a hydrostatic pressure that forced the lava to solidify in a rounded shape, similar to the one of a pillow.

Basaltic dykes/dikes: dykes are vertical or semi-vertical magmatic intrusions, these are made of basalt which means they are particularly rich in plagioclase feldspar minerals, specifically rich in calcium.

Gabbroic rocks: gabbro is an intrusive rock, it is pretty much the intrusive counterpart to basalt, as it is also rich in high-Ca plagioclase feldspar minerals.

Moho: "Moho" is not a rock formation, but a geologic and chemical discontinuity that separates crust and mantle, the full name of the discontinuity is "Mohorovičić discontinuity", but most people refer to it as just Moho. It's definied by a significant change in the velocity of seismic waves that pass through it.

Peridotites: the top of the mantle is made up mainly by dunites and peridotites, which are both "ultramaphic rocks", as in rocks that are particularly rich in magnesium and iron. dunites are significantly rich in olivine minerals, while the term "peridotite" is used to refer to ultramaphic rocks that have both olivine and pyroxen minerals in relatively similar ratios. (There is honestly an entire essay that could be written about these rocks alone but maybe in a different post, they are my favorite rocks lol).

I hope this post was informative and interesting to read, if you have questions please don't hesitate sending asks to my inbox!

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need something to push me to make posts again so I guess I'm going to ask here for interest

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm not a student anymore, didn't study geology in school, and have a full time job. Do you have any recommendations for getting started learning about geology? I'm a big fan of rocks, have a growing collection, and even attended the Tucson Gem and Mineral show for the first time this year, but I don't actually know much. Thanks!

It really depends on which aspects you are more interested in, since geology is a very eclectic and varied field.

Genuinely, if you're an extreme beginner I would just take a look at the wikipedia page for a field that you're interested in, read through it, get a look at the sources and start from there.

If you're interested in mineralogy and petrology specifically though, I would recommend "Earth Materials" by Klein and Philpotts and "Manual of Mineralogy" by Klein. They're pretty expensive though, so DM me so I can tell you where to find them for cheap, wink wink.

The first one I would say is easier to understand for beginners and it includes both petrography and mineralogy elements, as in it talks about how rocks form and the minerals that make them. The second one delves deeper in the mineralogy aspect and is more advanced. My disclaimer here is that I studied on the Italian translations of these books so I can't 100% guarantee that they'll be what I say they are.

Also, you can send me asks about anything and I'll try my best to answer them, though I am not an expert and might simply not know or know very little about certain things, but I might redirect you to a good article if you have a specific question in mind. Alternatively I can just give you a rundown of the main geological sciences and you can decide which one you would like to research more into.

Alternatively alternatively, start from the rocks you have! Do you know what rocks they are? Research those types of rocks, and then branch out. I hope this was helpful in any way, I only started learning about geology once I started studying it in university (I didn't even care about it beforehand I just stumbled upon it) so I'm not sure how a regular non-student could research geology.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

taking some quartzite samples in Sardinia

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

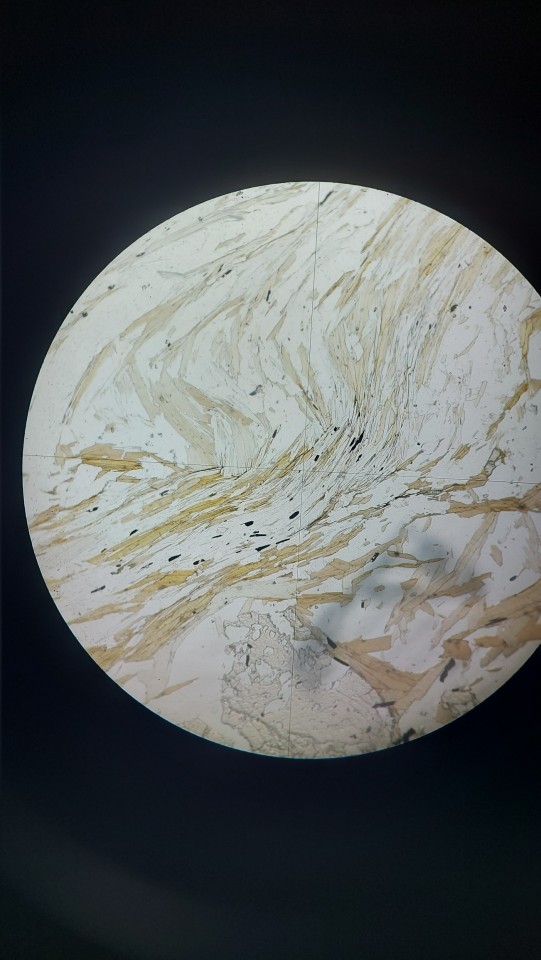

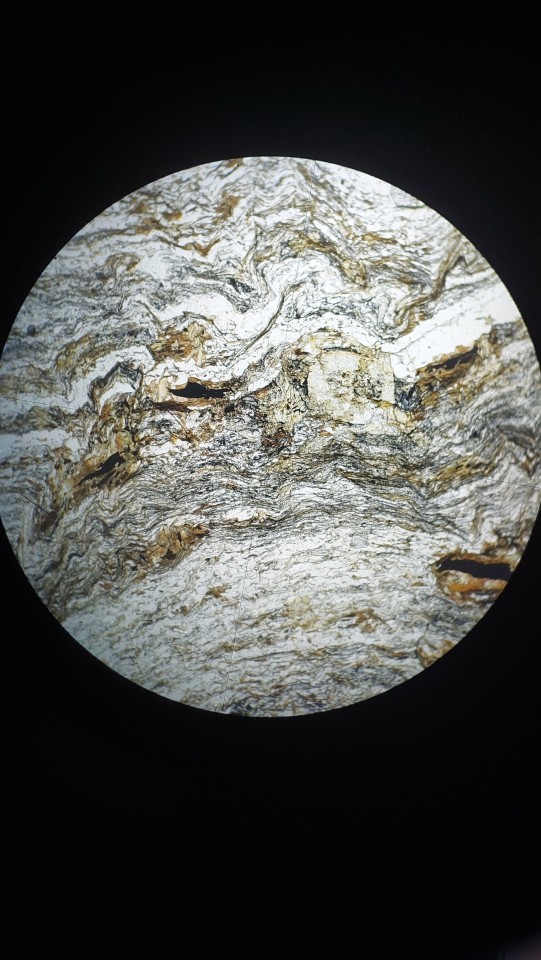

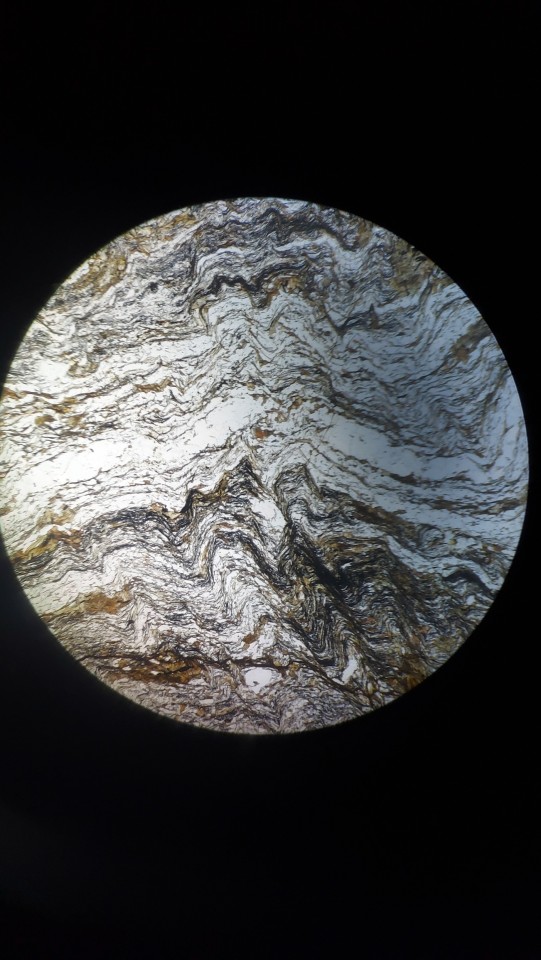

beware - these are not planets, but images of two schists under a polarising microscope!

the first image is one section, and the second and third are a different section, but both of them are thin sections of a schist!

a schist is a metamorphic rock, called this way because it presents schistosity, as in the rock's mineral grains are oriented in a preferential direction, along which the rock breaks more easily!

in this case, the brown stuff you see is biotite, or black mica, some of the white is muscovite (white mica), and some of the other white stuff is quartz!

90 notes

·

View notes

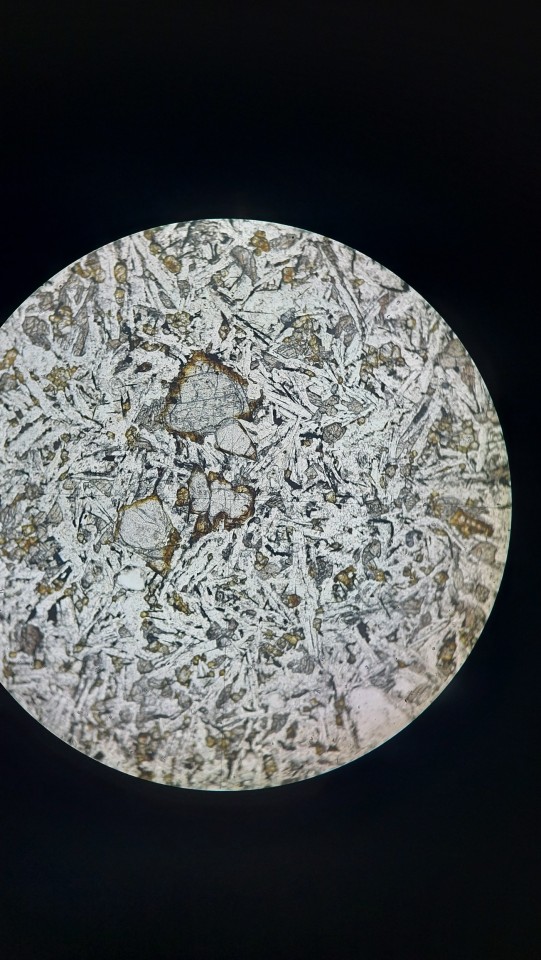

Text

basalt with olivine under a microscope

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

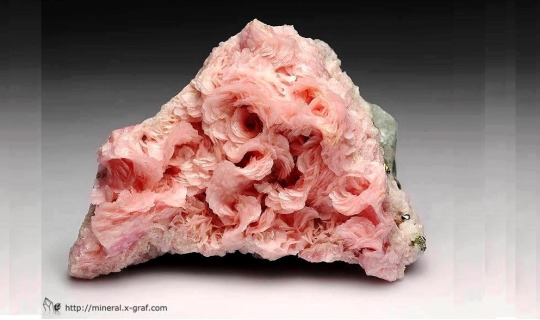

I’m a huge fan of how rhodochrosite can either look like beautiful pink flowers, like pointy red crystals, like little Barbie-pink orbs, or like meat

[ image description: rhodochrosite in each of the previously described forms, ending with some rhodochrosite stalactite chunks that look like breaded hams and one piece that looks like a raw steak growing out of a rock. ]

115K notes

·

View notes

Text

Everybody give it up for columnar jointing

177K notes

·

View notes

Text

ohh this is so nice, i hope you enjoyed it!

Aragonite [CaCO3], Dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2] & other carbonatic minerals

This post is a part two to my "Calcite (CaCO3)" post, you don't have to read that one to understand this one, but it would make more sense to read them in order.

Aragonite [CaCO3]

Aragonite is another one of the most common carbonatic minerals on the Earth's surface, right alongside calcite. Calcite and aragonite share the same chemical formula (CaCO3) because they are both polymorphs of the calcium carbonate compound.

Polymorph: The same chemical compound can present itself naturally under more than one form, depending on temperature and pressure. Multiple forms that share the same chemical formula but are stable at different values of temperature and pressure, are defined as polymorphs. In this case, the formula is CaCO3, which is also known as calcium carbonate.

Aragonite's structure is a lot come compact than calcite's, which means it crystallizes in different shapes. Notably, aragonite is subject to a peculiar type of gemination that is called "hexagonal gemination", in which 3 different crystals grow around the same axis, forming an hexagonal prism.

Gemination: It's a concept that I wish to talk more extensively about in a separate post, but all you need to know is that it happens when crystals grow around, inside, next to and on top of each other.

Aragonite is stable at much higher pressure values than calcite is, so how are we able to see it when it's not subject to that high pressure anymore? Shouldn't all aragonite become calcite when it's brought to armospheric pressures?

This is a particular phenomenon called metastability, the structures of calcite and aragonite are too different for an aragonite crystal to quickly turn into calcite when it's not in stable conditions anymore. Which means, aragonite isn't actually stable in conditions of armospheric pressure, but it takes it too much energy to turn into a stable compoud, and so it stays as it is (I will expand on metastability later on).

Dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2]

Dolomite is another relatively common carbonatic mineral, and it's more or less composed of a 1:1 ratio of calcium and magnesium. It is denser and harder than calcite and aragonite, and its structure can be described as alternating layers of CaCO3 and MgCO3.

Less common carbonatic minerals

Magnesite [MgCO3]

Siderite [FeCO3]

Smithsonite [ZnCO3]

Rhodochrosite [MnCO3]

Cerussite [PbCO3]

Strontianite [SrCO3]

Witherite [BaCO3]

Malachite [Cu2(CO3)(OH)2]

Azzurrite [Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2]

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aragonite [CaCO3], Dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2] & other carbonatic minerals

This post is a part two to my "Calcite (CaCO3)" post, you don't have to read that one to understand this one, but it would make more sense to read them in order.

Aragonite [CaCO3]

Aragonite is another one of the most common carbonatic minerals on the Earth's surface, right alongside calcite. Calcite and aragonite share the same chemical formula (CaCO3) because they are both polymorphs of the calcium carbonate compound.

Polymorph: The same chemical compound can present itself naturally under more than one form, depending on temperature and pressure. Multiple forms that share the same chemical formula but are stable at different values of temperature and pressure, are defined as polymorphs. In this case, the formula is CaCO3, which is also known as calcium carbonate.

Aragonite's structure is a lot come compact than calcite's, which means it crystallizes in different shapes. Notably, aragonite is subject to a peculiar type of gemination that is called "hexagonal gemination", in which 3 different crystals grow around the same axis, forming an hexagonal prism.

Gemination: It's a concept that I wish to talk more extensively about in a separate post, but all you need to know is that it happens when crystals grow around, inside, next to and on top of each other.

Aragonite is stable at much higher pressure values than calcite is, so how are we able to see it when it's not subject to that high pressure anymore? Shouldn't all aragonite become calcite when it's brought to armospheric pressures?

This is a particular phenomenon called metastability, the structures of calcite and aragonite are too different for an aragonite crystal to quickly turn into calcite when it's not in stable conditions anymore. Which means, aragonite isn't actually stable in conditions of armospheric pressure, but it takes it too much energy to turn into a stable compoud, and so it stays as it is (I will expand on metastability later on).

Dolomite [CaMg(CO3)2]

Dolomite is another relatively common carbonatic mineral, and it's more or less composed of a 1:1 ratio of calcium and magnesium. It is denser and harder than calcite and aragonite, and its structure can be described as alternating layers of CaCO3 and MgCO3.

Less common carbonatic minerals

Magnesite [MgCO3]

Siderite [FeCO3]

Smithsonite [ZnCO3]

Rhodochrosite [MnCO3]

Cerussite [PbCO3]

Strontianite [SrCO3]

Witherite [BaCO3]

Malachite [Cu2(CO3)(OH)2]

Azzurrite [Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2]

38 notes

·

View notes