Global perspectives on Black cinema and entertainment.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

TRAILER: "BLACK ICE"

Black Ice, the award-winning UNINTERRUPTED documentary that exposes a history of racism in hockey through the untold stories of Black hockey players, both past and present, in a predominantly white sport.

youtube

Roadside Attractions will release BLACK ICE exclusively in AMC Theaters nationwide on July 14th, 2023

Directed by Academy Award®- and Emmy-nominated filmmaker Hubert Davis, Black Ice masterfully navigates the challenges, triumphs, and unique experiences faced by these athletes through poignant firsthand accounts from Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) hockey players past, including Willie O’Ree, the first Black player in the National Hockey League, and former professional hockey player Akim Aliu, with the stories of present stars, including P.K. Subban and Wayne Simmonds. The film explores the deep BIPOC roots of the game, dating back to 1865 and the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes (CHL), the first all-pro league, which not only introduced the slapshot but shaped the game of hockey we know today. Davis exposes racist patterns that span generations, even highlighting stories of how sports institutions have exerted pressure on players seeking change to remain silent.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trailer: "The League", directed by Sam Pollard

Magnolia Pictures will release THE LEAGUE exclusively in AMC Theaters starting July 7, and will be available on digital July 14.

Directed by acclaimed filmmaker Sam Pollard (MLK/FBI), executive produced by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson (Oscar-winning SUMMER OF SOUL), Tariq Trotter (DESCENDANT), and produced by RadicalMedia, THE LEAGUE celebrates the dynamic journey of Negro League baseball's triumphs and challenges through the first half of the twentieth century.

The story is told through previously unearthed archival footage and never-before-seen interviews with legendary players like Satchel Paige and Buck O’Neil – whose early careers paved the way for the Jackie Robinson era – as well as celebrated Hall of Famers Willie Mays and Hank Aaron who started out in the Negro Leagues.

From entrepreneurial titans Cumberland Posey and Gus Greenlee, whose intense rivalry fueled the rise of two of the best baseball teams ever to play the game, to Effa Manley, the activist owner of the Newark Eagles and the only woman ever admitted to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, THE LEAGUE explores Black baseball as an economic and social pillar of Black communities and a stage for some of the greatest athletes to ever play the game, while also examining the unintended consequences of integration.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Celebrating Akosua Adoma Owusu! "...Owusu explores the colliding identities of black immigrants in America through multiple forms, ranging from cinematic essays to experimental narratives to reconstructed Black popular media." Visit her website for more information about her work: https://akosuaadoma.com/home.html

Explore Short Films by Akosua Adoma Owusu streaming now on Criterion Channel.

"Blurring the boundaries of experimental, narrative, and documentary filmmaking, her stylistically freewheeling shorts...address racism, postcolonialism, and white supremacy."

https://criterionchannel.com/short-films-by-akosua-adoma...

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

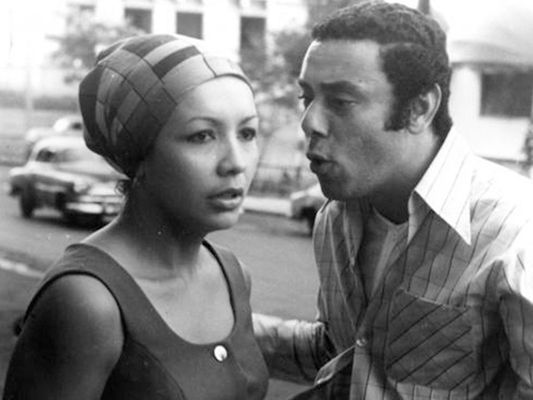

Celebrating Sara Gómez! "In black and white, she addresses racial prejudice, discrimination, marginalization and the consequences for families, machismo, breaking with the past and social programs aimed at improving life and dignifying Cuban men and women."

Learn more in Cuba 50's article Sara Gómez: Cuba’s first female film director.

'“One Way or Another” is so brimming with life and ideas that it is shattering to learn that Gómez died, at just 31, while editing it — she succumbed to a severe asthma attack amid complications giving birth to her third child.

The postproduction was completed by her colleagues, and the movie was not shown until 1977. Since then, it has been recognized as a landmark of feminist, neorealist, Communist, Cuban, Latinx, Third World and simply world cinema.' J. Hoberman, A Feminist, Neorealist, Communist Film, and a Plain Great Movie (NY Times)

Explore her filmography on MUBI:

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resounding success of ‘Black Panther’ franchise says little about the dubious state of Black film

by Phillip Lamarr Cunningham, Assistant Professor, Media Studies, Wake Forest University

When Marvel Studios released “Black Panther” in February 2018, it marked the first Marvel Cinematic Universe film to feature a Black superhero and star a predominantly Black cast.

Its estimated production budget was US$200 million, making it the first Black film – conventionally defined as a film that is directed by a Black director, features a Black cast, and focuses on some aspect of the Black experience – ever to receive that level of financial support.

As a scholar of media and Black popular culture, I was often asked to respond to the resounding success of that first “Black Panther” film, which had shattered expectations of its box office performance.

Would it lead to more big-budget Black films? Was its popularity an indication that the global marketplace – the real source of trepidation about the film’s potential – was finally ready to embrace Black-cast films?

With the release of the massively successful “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” in November 2022, I expect those questions to reemerge.

Yet as I review the cinematic landscape between the original and its sequel, I am inclined to restate the answer I gave back in 2018: Assumptions should not be made about the state of Black film based on the success of the “Black Panther” franchise.

Reason for optimism

Prior to its release, the producers of “Black Panther” faced questions about whether there was a market for a Black blockbuster film, even one ensconced in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

After all, since the Wesley Snipes-led “Blade” trilogy, which came out in the late-1990s and early 2000s, Black superhero films had experienced diminishing returns. There was one notable exception: the commercially successful, though heavily panned “Hancock” (2008), starring Will Smith.

Otherwise, Black superhero films such as “Catwoman” (2004) and “Sleight” (2016) either flopped or had a limited release.

Furthermore, until “Black Panther,” no Black film exceeded a $100 million budget, the average benchmark for modern Hollywood blockbusters.

Nonetheless, despite these early concerns, “Black Panther” earned the highest domestic gross, $700 million, of all films released in 2018, while earning $1.3 billion in worldwide gross, second only to “Avengers: Infinity War.”

“Black Panther” emerged at the tail end of what many industry experts considered to be a surprisingly successful run of Black films, which included the biopic “Hidden Figures” (2016) and the raunchy comedy “Girls Trip” (2017). Despite their modest budgets, they earned over $100 million apiece at the box office – $235 million and $140 million, respectively.

However, both films were mostly reliant on the domestic box office, especially the R-rated “Girls Trip,” which was only released in a handful of foreign markets. Conventional wisdom has long held that Black films will fail abroad. International distributors and studios typically ignore them during the presale process or at film festivals and markets, reasoning that Black films are too culturally specific – not only in terms of their Blackness, but also their Americanness.

Films like “Black Panther” and the Oscar winning “Moonlight” (2016), which earned more on the international market than the domestic market, certainly challenged those assumptions. It has yet to upend them.

Black films after ‘Black Panther’

What do those Black films released in theaters in the nearly five years between “Black Panther” and “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” tell us about the former’s impact?

The simple answer is that the original “Black Panther” has had no discernible influence on industry practices whatsoever.

Since 2018, no other Black blockbuster has emerged, save for the sequel itself. Granted, Black filmmaker Ava DuVernay’s remake of “A Wrinkle in Time” (2018) reportedly cost an estimated $100 million; however, while Black actors portrayed the protagonist and a few other characters, the film features a multicultural ensemble cast – which, as scholars such as Mary Beltran have pointed out, has become the primary strategy for achieving diversity in film.

Even if one were to include “A Wrinkle in Time,” the grand total of Black films with budgets exceeding $100 million is three, with the two “Black Panther” films being the others – all during an era in which there have been hundreds of mainstream films with budgets exceeding $100 million.

Otherwise, most of the Black films released in theaters between 2018 and 2022 typically were low budget by Hollywood standards – $3 million to $20 million in most cases – with only a handful, such as the 2021 Aretha Franklin biopic “Respect,” costing $50 million to 60 million.

Perhaps the most notable change has been the medium. Many Black films now appear on either cable networks that cater to a Black audience – namely Black Entertainment Television and, more recently, Lifetime – or on streaming services such as Netflix. Tyler Perry, the most popular and prolific Black filmmaker of the modern era, has released his latest films – “A Jazzman’s Blues” (2022), “A Madea Homecoming” (2022) and “A Fall from Grace” (2020) – directly to Netflix.

Furthermore, no other Black film has approached the financial success of “Black Panther.” Granted, several Black films have fared well at the box office, especially relative to their production costs. Foremost among them is Jordan Peele’s “Us” (2019), which cost an estimated $20 million, yet earned approximately $256 million worldwide despite its R rating and the fact that it was never released in China.

Whither Black film

Without question, large budgets and commercial success are not the only measures of a film’s value and significance.

As has historically been the case, Black film has managed to do more with less. The critical acclaim afforded to films such as “BlackKlansman” (2018), “If Beale Street Could Talk” (2019) and “King Richard” (2021) reflect this fact. All reflect trends in contemporary Black filmmaking – comedies, historical dramas and biopics abound, for instance – and were made for a fraction of the cost of both “Black Panther” films.

In truth, the zeal with which some cast “Black Panther” as a bellwether for Black films is part of continued haranguing over their viability, particularly after the #OscarsSoWhite movement that drew attention to the lack of diversity at the 2016 Academy Awards.

However, its positioning as a Disney property within Marvel’s transmedia storytelling effort makes it so atypical that its success — and that of its sequel — portends little about Black film.

#wakanda forever#marvel cinematic universe#Black Panther#oscars so white#Hollywood#Marvel#Diversity#filmmaking#featured#representation

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OscarsSoWhite still plagues Hollywood’s highest achievement awards

by Frederick Gooding, Jr., Dr. Ronald E. Moore Professor of Humanities and African American Studies at Texas Christian University

Four Black actors were nominated for Oscars in 2022, six years after the Twitter campaign #OscarsSoWhite rocked Hollywood.

In the long history of Hollywood snubs, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gets some credit for at least trying to diversify the Hollywood film industry.

After all, it’s not a complete shutout for Black actors, as it was in 2016 when #OscarsSoWhite castigated the Academy for not having a single Black actor nominated for an Oscar in any acting category, despite riveting performances by Michael B. Jordan in “Creed”, Will Smith in “Concussion” and Corey Hawkins in “Straight Outta Compton”.

When the 94th Academy Awards take place on March 27, 2022, its efforts for diversity – and its shortcomings – will be just as much on display as the designer gowns and outstanding performances.

The four Black actors nominated for the Academy’s highest honor this year are longtime Hollywood stars Denzel Washington and Smith, in addition to Aunjanue Ellis and Ariana DuBose – who is also Latina.

These recognitions come on the heels of intensified scrutiny of equitable representation within Hollywood – and concerted efforts by the Academy to diversify. Although there have been winners of color, no Black person has won an Oscar for directing, and only 20 acting awards have gone to performers of color in 94 years.

Given the 336 Oscars for acting that have been awarded over the ceremony’s lifetime, actors of color account for roughly 6% of overall wins.

“While the Academy has made strides, we know there is much more work to be done in order to ensure equitable opportunities across the board,” Academy CEO Dawn Hudson said in 2020. “The need to address this issue is urgent.”

Her response was in stark contrast to former Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, the Academy’s first Black president, who was elected in 2013. When asked about the #OscarsSoWhite campaign in 2015 and whether the Academy had a diversity problem, she responded, “Not at all.”

As a scholar of American pop culture and race in media, I can say Hollywood has come a long way.

Hollywood diversity

On Jan. 15, 2015, Twitter user and activist April Reign first tweeted “#OscarsSoWhite they asked to touch my hair.” Within that day, the hashtag became viral and many Black actors and social activists used the tweet to protest Hollywood’s longstanding racism.

To the Academy’s credit, it responded to #OscarsSoWhite criticisms by making steps to reconfigure its nomination process that had resulted in such a lack of Black inclusion.

In 2020, for instance, the Academy established new representation and inclusion standards that take effect in 2024. According to its official statements, the new standards were designed to “encourage equitable representation on and off screen in order to better reflect the diversity of the movie-going audience.”

But critics have observed how films with virtually no Black characters like “The Irishman” still meet inclusion standards by employing a white female casting director and a Mexican cinematographer.

Racist Hollywood history

Racial drama started early in Hollywood.

The first groundbreaking feature-length movie, “The Birth of a Nation,” released in 1915, celebrated the Ku Klux Klan. The first talking film ever released in 1927, “The Jazz Singer,”, featured white actors in blackface.

The Academy kept alive this tradition, with echoes of racist minstrel shows from the early 20th century, in 2008 when Robert Downey Jr. received a Best Supporting Actor nomination for his role in blackface in “Tropic Thunder.”

Indeed, during the early history of Hollywood, Black characters were openly denigrated by the stereotypical images that they portrayed. Black actors were usually given badly written roles portraying weak, poor or otherwise disadvantaged characters who were dependent on white characters’ heroism.

Hattie McDaniel, for example, became the first nonwhite actor to ever win an Academy Award in 1939 with a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her sassy, but servile “Mammy” figure in “Gone with the Wind.”

In this 1938 photograph, Hattie McDaniel is seen in her role as Mammy in the movie ‘Gone with the Wind.’ Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

Despite McDaniel’s breakthrough Oscar in 1939 and Sidney Poitier’s 1963 Best Actor win for “Lilies of the Field”, it took more than 40 years before Halle Berry claimed the Best Actress prize in 2002 for her role in “Monster’s Ball” – a role that Oscar nominee Angela Bassett rejected due to her refusal to “be a prostitute on film.”

In 2011, Octavia Spencer won an Oscar – also for playing a maid like McDaniel – for her role as Minny in “The Help.”

Still, in 2002, when Berry won, diversity was center stage in Hollywood. That same year, the Best Actor winner was Washington for his uncharacteristically villainous role in “Training Day.”

In addition that year, Poitier received a lifetime achievement award, an acknowledgment for many of his groundbreaking roles throughout his career.

Actors Denzel Washington and Halle Berry pose while holding their Oscar statues in 2002. Lee Celano/AFP via Getty Images

A little progress

Yet, five years after #OscarsSoWhite, British actress Cynthia Erivo represented the lone Black acting nomination in 2020 for her role as Harriet Tubman in “Harriet,” leaving Berry as the only Black female to ever be awarded Best Actress.

Overall, of the 86 Black acting nominations over the Academy’s 94-year period, over 40% of the nominations have been circulated among repeat contenders like Washington and Smith. Major studios often favor established, sure bets at the expense of new Black talent when it is time to recoup their investments at the box office.

With only a handful of the same Black names garnering nominations, the pool of Black talent celebrated is actually smaller than what it appears.

While in today’s movie climate the quantity of nonwhite images has undoubtedly improved, it is the quality of such roles that remain problematic.

The struggle continues

For the same industry that can reproduce exacting replicas, orchestrate mass battles and fashion accurate costumes, it is alarming that such a creative industry cannot figure out how to create substantive diversity onscreen.

Alternative outlets like Hulu and Netflix are demonstrating that viable audiences are willing to support a wide range of diverse products featuring increasingly diverse casts – with “Bridgerton” and “Squid Game” as a couple of recent examples.

But six years after #OscarsSoWhite, the Academy is still struggling to diversify the Hollywood film industry – perhaps a simple lack of imagination is to blame.

0 notes

Text

Sidney Poitier – Hollywood’s first Black leading man reflected the civil rights movement on screen

by Aram Goudsouzian, Bizot Family Professor of History at the University of Memphis

In the summer of 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. introduced the keynote speaker for the 10th-anniversary convention banquet of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Their guest, he said, was his “soul brother.”

“He has carved for himself an imperishable niche in the annals of our nation’s history,” King told the audience of 2,000 delegates. “I consider him a friend. I consider him a great friend of humanity.”

That man was Sidney Poitier.

Poitier, who died at 94 on Jan. 7, 2022, broke the mold of what a Black actor could be in Hollywood. Before the 1950s, Black movie characters generally reflected racist stereotypes such as lazy servants and beefy mammies. Then came Poitier, the only Black man to consistently win leading roles in major films from the late 1950s through the late 1960s. Like King, Poitier projected ideals of respectability and integrity. He attracted not only the loyalty of African Americans, but also the goodwill of white liberals.

In my biography of him, titled “Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon,” I sought to capture his whole life, including his incredible rags-to-riches arc, his sizzling vitality on screen, his personal triumphs and foibles and his quest to live up to the values set forth by his Bahamian parents. But the most fascinating aspect of Poitier’s career, to me, was his political and racial symbolism. In many ways, his screen life intertwined with that of the civil rights movement – and King himself.

Sidney Poitier, center, marches during the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C., in May 1968. Photo by Chester Sheard/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

An age of protests

In three separate columns in 1957, 1961 and 1962, a New York Daily News columnist named Dorothy Masters marveled that Poitier had the warmth and charisma of a minister. Poitier lent his name and resources to King’s causes, and he participated in demonstrations such as the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage and the 1963 March on Washington. In this era of sit-ins, Freedom Rides and mass marches, activists engaged in nonviolent sacrifice not only to highlight racist oppression, but also to win broader sympathy for the cause of civil rights.

In that same vein, Poitier deliberately chose to portray characters who radiated goodness. They had decent values and helped white characters, and they often sacrificed themselves. He earned his first star billing in 1958, in “The Defiant Ones,” in which he played an escaped prisoner handcuffed to a racist played by Tony Curtis. At the end, with the chain unbound, Poitier jumps off a train to stick with his new white friend. Writer James Baldwin reported seeing the film on Broadway, where white audiences clapped with reassurance, their racial guilt alleviated. When he saw it again in Harlem, members of the predominantly Black audience yelled “Get back on the train, you fool!”

King won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. In that same year, Poitier won the Oscar for Best Actor for “Lilies of the Field,” in which he played Homer Smith, a traveling handyman who builds a chapel for German nuns out of the goodness of his heart. The sweet, low-budget movie was a surprise hit. In its own way, like the horrifying footage of water hoses and police dogs attacking civil rights activists, it fostered swelling support for racial integration.

Sidney Poitier, Katherine Houghton and Spencer Tracy in the 1967 film ‘Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.’ Photo by RDB/ullstein bild via Getty Images

A better man

By the time of the actor’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference speech, both King and Poitier seemed to have a slipping grip on the American public. Bloody and destructive riots plagued the nation’s cities, reflecting the enduring discontent of many poor African Americans. The swelling calls for “Black Power” challenged the ideals of nonviolence and racial brotherhood – ideals associated with both King and Poitier.

When Poitier stepped to the lectern that evening, he lamented the “greed, selfishness, indifference to the suffering of others, corruption of our value system, and a moral deterioration that has already scarred our souls irrevocably.” “On my bad days,” he said, “I am guilty of suspecting that there is a national death wish.”

By the late 1960s, both King and Poitier had reached a crossroads. Federal legislation was dismantling Jim Crow in the South, but African Americans still suffered from limited opportunity. King prescribed a “revolution of values,” denounced the Vietnam War, and launched a Poor People’s Campaign. Poitier, in his 1967 speech for the SCLC, said that King, by adhering to his convictions for social justice and human dignity, “has made a better man of me.”

Exceptional characters

Poitier tried to adhere to his own convictions. As long as he was the only Black leading man, he insisted on playing the same kind of hero. But in the era of Black Power, had Poitier’s saintly hero become another stereotype? His rage was repressed, his sexuality stifled. A Black critic, writing in The New York Times, asked “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?”

President Barack Obama presents Academy Award-winning actor Sidney Poitier with the Medal of Freedom in 2009. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

That critic had a point: As Poitier himself knew, his films created too-perfect characters. Although the films allowed white audiences to appreciate a Black man, they also implied that racial equality depends on such exceptional characters, stripped of any racial baggage. From late 1967 into early 1968, three of Poitier’s movies owned the top spot at the box office, and a poll ranked him the most bankable star in Hollywood.

Each film provided a hero who soothed the liberal center. His mannered schoolteacher in “To Sir, With Love” tames a class of teenage ruffians in London’s East End. His razor-sharp detective in “In the Heat of the Night” helps a crotchety white Southern sheriff solve a murder. His world-renowned doctor in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” marries a white woman, but only after winning the blessing of her parents.

“I try to make movies about the dignity, nobility, the magnificence of human life,” he insisted. Audiences flocked to his films, in part, because he transcended racial division and social despair – even as more African Americans, baby boomers and film critics tired of the old-fashioned do-gooder spirit of these movies.

Intertwined lives

And then, the lives of Martin Luther King Jr. and Sidney Poitier intersected one final time. After King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, Poitier was a stand-in for the ideal that King embodied. When he presented at the Academy Awards, Poitier won a massive ovation. “In the Heat of the Night” and “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” captured most of the major awards. Hollywood again dealt with the nation’s racial upheaval through Poitier movies.

But after King’s violent murder, the Poitier icon no longer captured the national mood. In the 1970s, a generation of “Blaxploitation” films featured violent, sexually charged heroes. They were a reaction against the image of a Black leading man associated with Poitier. Although his career evolved, Poitier was no longer a superstar, and he no longer bore the burden of representing the Black freedom movement. Yet for a generation, he had served as popular culture’s preeminent expression of the ideals of Martin Luther King.

0 notes

Video

youtube

AAFCA Remembers Sidney Poitier

0 notes

Video

youtube

2021 AAFCA TV Honors

Here’s the entire run of The 3rd Annual African American Film Critics Association TV Honors Awards, celebrating the best performances in Television.

This years ceremony was hosted by Yvette Nicole Brown.

0 notes

Text

Why Nollywood is obsessed with remakes of classic movies

by Ezinne Ezepue, Lecturer at the University of Nigeria

Since the record-breaking success of Ramsey Nouah’s 2019 sequel to the Nollywood classic, Living in Bondage, the Nigerian film industry has been overtaken by a frenzy of remakes and sequels of classics from the 1990s. These new nostalgia-driven movies have recently proved popular among viewers, becoming top earners at the local box-office.

Successful examples include Living in Bondage: Breaking Free, which has won major continental awards. Funke Akindele’s Omo Ghetto: The Saga is a sequel to Abiodun Olarenwaju’s Omo Ghetto. It is currently the highest grossing film in Nigeria. The sequels to Kemi Adetiba’s The Wedding Party and Toke Mcbaror’s Merry Men have earned nearly as much as their prequels.

Netflix has also joined in the action. The streaming company is currently distributing remakes of Zeb Ejiro’s Nneka the Pretty Serpent (1992) and Amaka Igwe’s RattleSnake (1995). It has also commissioned two new remakes of Ejiro’s Domitilla (1996) and Chika Onukwufor’s Glamour Girls (1994). Both releases are planned for late 2021.

These Nollywood classics have stayed popular due to their unique original storytelling, creativity and accessibility. They were cultural productions reflecting the lived experiences of Nigerians. They also expressed societal and cultural aspirations, while providing relatable entertainment.

1990s Nollywood classics also introduced a crop of talented actors who delivered performances that turned them into household names and international stars. Actors such as Omotola Jalade-Ekeinde, Genevieve Nnaji, the late Sam Loco, Sam Dede, Nkem Owoh, and others rose to prominence in that era.

These films were largely made by trained professionals. Prominent names include the late Amaka Igwe, the Ejiro brothers – Zeb and late Chico, Chris Obi-Rapu (Vic Mordi), Tunde Kelani, Andy Amenechi, Tade Ogidan, Okechukwu Ogunjiofor, Kenneth Nnebue, among others. Their works provided the growing industry with templates for effective storytelling. They inspired production houses to invest in similar storylines and plots.

For instance, after the success of Living in Bondage in 1992, the local market was flooded with multiple releases exploring satanic cult storylines and money ritual themes. Zeb Ejiro’s Nneka The Pretty Serpent (1992) inspired a string of movies stereotyping pretty young ladies as evil seductresses.

Among Nollywood films of the 1990s, Living in Bondage stands out. Not only did it contain enduring emotional resonance, its financial success also advanced the industry, providing a template for the Nollywood economic model, commonly referred to today as ‘old Nollywood’.

As Nollywood continues to grow and improve on output and professionalism, these old movies still retain a strong influence on the industry, except in terms of technology and budget size.

History of Nigerian filmmaking

The film industry in Nigeria can be traced to the colonial era. The first film (not video film) was exhibited in August 1903 at the Clover Memorial Hall in Lagos. Most early productions favoured documentaries and propaganda films designed to foster cohesion and orientation in the colonial framework. In the early films, local talents largely played only minor roles and transfer of technology was limited.

youtube

In 1947, a Federal Film Unit was established by the colonial administration, with the bulk of releases supplied from London, and distributed via the British Council and missionary efforts. These films were screened in makeshift centers, including school premises, village halls, open spaces, and civic centers. All it needed was a mobile film unit comprising a van, a 16mm projector, a reel of 16mm and a collapsible screen.

The 1960s saw the rise of feature films, with movies such as Moral Disarmament (1957) and Bound for Lagos (1962) produced for the Nigerian government. An oil company, Shell-BP of Nigeria Limited, also released a full length feature film titled Culture in Transition in 1963. And in 1970, Kongi’s Harvest, a version of a play by Wole Soyinka, was released.

After Nigeria gained independence in 1960, the federal government opened the distribution circuit to private Nigerians, while remaining the major producer, distributor and exhibitor. This led to the rise of cinema culture in Nigeria due to the influx of independent operators into the industry.

By mid to late 1980s, cinema in Nigeria began to decline for a number of reasons. These include, the rising television culture and the emergence of the Video Home System (VHS), oil boom, economic recessions, drop in cinema patronage (resulting from insecurity), rising cost of living and cost of film production in comparison to yield.

By early 1990s, cinemas were either closing down or being converted for other uses. This contributed to the birth of the video-film era which began in the late 1980s but became popular with the success of Living in Bondage (1992). Along with a number of other titles produced in the 1990s, Living in Bondage became a classic.

Why Nollywood classics still appeal to audiences

Nollywood critic Rosemary Bassey notes that a large number of films made in Nigeria in the early stages of video-filmmaking in Nigeria still appeal to a large majority of Nigerians. They told didactic stories which are deeply rooted in Nigerian culture. According to Nollywood researcher, Francoise Ugochukwu, this is the second major attraction for Nollywood diaspora audiences after language.

The nostalgia for these films therefore stems from their story-driven narratives, as opposed to the contemporary aesthetics-driven new Nollywood productions.

After a period of artistic impasse in the 2000s, today’s film industry in Nigeria is in a near-constant experimental phase to find new stories in a saturated industry. And central to this experimentation is a backward gaze to the past, when the classics dominated. Movie enthusiasts continue to discuss these old films with fond recollections. The opportunity presents itself. Why not cash in?

What this means for the industry

The most significant impact of Nollywood’s nostalgic obsession will be concerns over the industry structure and intellectual property protection. With a good economic structure, these remakes and sequels have the potential to revive earnings for the old films. I believe contemporary filmmakers will be motivated to take this seriously going forward.

Pursuing remakes and sequels also means there are less resources needed to develop and produce new stories. It also raises questions over the socio-cultural relevance of these stories in the global arena. Are contemporary Nollywood film re-makers too profit-driven by the opportunity of transnational distribution, to begin to reclaim and repair Africa’s lost identity and damaged repute? Now is the time for the government and corporate bodies to intervene to further make Nollywood films globally competitive.

0 notes

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

‘The Underground Railroad’ attempts to upend viewers’ notions of what it meant to be enslaved

by William Nash, Professor of American Studies and English and American Literatures, Middlebury

Above: Making the series changed Barry Jenkins’ views on how his ancestors should be described and depicted. Atsushi Nishijima/Amazon Studios

Speaking on NPR’s Fresh Air, Barry Jenkins, the director of “The Underground Railroad,” noted that “before making this show … I would have said I’m the descendant of enslaved Africans.”

“I think now that answer has evolved,” he continued. “I am the descendant of blacksmiths and midwives and herbalists and spiritualists.”

As a scholar interested in how modern representations of enslavement shape our understanding of the past, I am struck by the ways Jenkins seeks to change the way viewers think about – and talk about – Black American history.

In doing so, he takes the baton from scholars, activists and artists who have, for decades, attempted to shake up Americans’ understanding of slavery. Much of this work has centered on reimagining slaves not as objects who were acted upon, but as individuals who maintained identities and agency – however limited – despite their status as property.

Pushing the boundaries of language

In the past three decades there has been a movement among academics to find suitable terms to replace “slave” and “slavery.”

In the 1990s, a group of scholars asserted that “slave” was too limited a term – to label someone a “slave,” the argument went, emphasized the “thinghood” of all those held in slavery, rendering personal attributes apart from being owned invisible.

Attempting to emphasize that humanity, other scholars substituted “enslavement” for “slavery,” “enslaver” for “slave owner,” and “enslaved person” for “slave.” Following the principles of “people-first language”– such as using “incarcerated people” as opposed to “inmates” – the terminology asserts that the person in question is more than just the state of oppression imposed onto him or her.

Not everyone embraced this suggestion. In 2015, renowned slavery and Reconstruction historian Eric Foner wrote, “Slave is a familiar word and if it was good enough for Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists it is good enough for me.”

Despite such resistance, more and more academics recognized the limitations of the older, impersonal terminology and started to embrace “enslaved” and its variants.

The new language reached another pinnacle with the publication of The New York Times’ 1619 Project. In the opening essay, project editor Nikole Hannah-Jones eschews “slave” and “slavery,” using variants of “enslavement” throughout. However controversial the series may be, it is setting the terms of current discussions about enslavement.

“Enslaved person” – at least among people open to the idea that a fresh look at American chattel slavery necessitated new language – became the new normal.

What, then, to make of Barry Jenkins’ saying he wants to push past this terminology?

In that same NPR interview, Jenkins notes that “right now [Americans] are referring to [Black slaves] as enslaved, which I think is very honorable and worthy, but it takes the onus off of who they were and places it on what was done to them. And I want to get to what they did.”

I think that Jenkins is onto something important here. Whichever side you take in the ongoing terminology debate, both “slave” and “enslaved person” erase both personality and agency from the individuals being described. And this is the conundrum: The state of enslavement was, by definition, dehumanizing.

Above: Caesar, played by Aaron Pierre, and Cora, played by Thuso Mbedu, escape from the plantation where they were held as slaves in ‘The Underground Railroad.’ Kyle Kaplan/Amazon Studios

For artists, writers and thinkers it’s difficult to reflect on the dehumanization of masses of people without diminishing some of the characteristics that make them unique. And once you step onto that path, it’s a short journey to reducing the identity of the collective group – including their ancestors – to one that’s defined by their worst experiences.

Seeing slaves on screen

In some ways, because of the nature of their medium, filmmakers have fared better than their fellow artists at balancing the challenges of portraying the horrific experiences of enslaved people as a whole and elevating the particular experiences of enslaved individuals.

So where does Jenkins fit in the lineage of cinematic depictions of enslavement?

From the start, comparisons to “Roots” – the first miniseries about American chattel slavery – abound.

“Roots,” which appeared in 1977, was the first miniseries on American television to explore the experiences of slavery on multiple generations of one Black family. It also created powerful opportunities for interracial empathy. As critic Matt Zoller Seitz notes, for “many white viewers, the miniseries amounted to the first prolonged instance of not merely being asked to identify with cultural experiences that were alien to them, but to actually feel them.”

Some Americans might remember those eight consecutive nights in January 1977 when “Roots” first aired. It was a collective experience that started and shaped national conversations about slavery and American history.

By contrast, “The Underground Railroad” appears in an age replete with representations of enslavement. WGN’s underappreciated series “Underground,” the 2016 remake of “Roots,” 2020’s “The Good Lord Bird,” “Django Unchained,” “12 Years a Slave” and “Harriet” are just a handful of recent innovative portrayals of slavery.

The best of these series push viewers toward new ways of seeing enslavement and those who resisted it. “The Good Lord Bird,” for example, used humor to dismantle ossified perceptions of John Brown, the militant 19th-century abolitionist, and opened up new conversations about when using violence to resist oppression is justifiable.

A delicate dance between beauty and suffering

Looking at “The Underground Railroad,” I can see how and why Jenkins’ vision is so important in this moment.

In Jenkins’ films “Moonlight” and “If Beale Street Could Talk,” the director made a name for himself as an artist who can push past narrow, constraining visions of Black identity as one marked solely by suffering. His films are not free from pain, of course. But pain is not their dominant note. His Black worlds are places where beauty abounds, where the characters in the stories he tells experience vibrancy as well as desolation.

Jenkins brings that sensibility to “The Underground Railroad” as well.

Critics have commented on how Jenkins uses the landscape to achieve this beauty. I was struck by how the sun-soaked fields of an Indiana farm create a perfectly fitting backdrop for the rejuvenating love Cora finds there with Royal.

In “The Underground Railroad,” slavery – for all its horrors – exists in an environment nonetheless imbued with beauty. The curtain of Cora’s vacant cabin flapping in the breeze and framed by the rough timbers of the slave quarters evokes the paintings of Jacob Lawrence.

Above: Barry Jenkins’ Black worlds are places where beauty abounds. Atsushi Nishijima/Amazon Studios

In other scenes, Jenkins juxtaposes radically different landscapes and actions to emphasize the complexity of these characters’ experiences. For example, Cora works as an actor at a museum, where she plays an “African savage” for visitors; in one scene, she changes out of the costume and into an elegant yellow dress. Walking the clean, orderly streets of Griffin, South Carolina, she transforms into a picture of middle-class propriety.

Scenes portraying the manners and reading lessons offered by the faculty of the Tuskegee-style institute where Cora and other fugitives find shelter demonstrate the allure of these middle-class values. On first glance, it all appears promising. Only later, when Cora’s pushed by her mentor to undergo forced sterilization, does it become apparent that she’s landed in a horror show.

These vignettes are but a few examples of the thoroughgoing power of Jenkins’ aesthetic. Every episode yields moments of beauty. And yet at the flip of a switch, serenity can devolve into savagery.

Living with the recognition that calm can instantly and unexpectedly become carnage is part of the human condition. Jenkins reminds viewers that for Black Americans – both then and now – this prospective peril can be particularly pronounced.

#film#tv streaming#television#amazon studios#african americans#african american history#slavery#enslavement#underground railroad#featured#thoughts

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lupita Nyong’o in the 2017 Pirelli Calendar. Photographed by Peter Lindbergh.

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jordan Peele has revealed the title and the main cast for his next film. “Nope” will star Daniel Kaluuya, Keke Palmer, and Steven Yeun.

That’s pretty much ALL he’s revealed with this poster he dropped on Twitter today. We’ll see what’s up in July of 2022!

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Trailer: “The HARDER THEY FALL” (Netflix, 2021)

0 notes

Text

Banning African films like Rafiki and Inxeba doesn’t diminish their influence

by Gibson Ncube, Associate Professor at the University of Zimbabwe

Social media and internet forums function as an important space of contestation for issues relating to queer identities. This is evident in reactions to two fairly recent queer-themed African films, one from South Africa – Inxeba/The Wound – and the other from Kenya – Rafiki.

The films were met with diverse responses, from government bannings and cultural backlash to enthusiastic viewers and international awards. On social media and internet forums, reactions differ from those of state institutions.

These various responses should be understood against the background that in many African countries, with the exception of South Africa in this case, queer sexualities are criminalised and deemed ‘unAfrican’. Many argue that homophobia itself is unAfrican and a relic of colonial laws and mores.

In my research, I have explored the fact that African queer lives are complex and don’t tell a single story. By viewing these films as popular social texts it became clear that government censorship has been unable to stop support for them or the kinds of discussions they generate, especially online.

Films as popular social texts

In Africa, films have become popular social texts. They are readily accessible and easily distributed, thanks to the internet and hand-held screen devices as well as the large-scale sale of pirated DVDs. The informality of circulation, coupled with the affordability of pirated films, has ensured that film has overtaken literary or text-based genres in influence in many parts of Africa.

Films like Inxeba (2017) and Rafiki (2018) can function as popular social texts in that they can ask questions about social issues – in this case queer lived experiences on the continent. Popular social texts appeal to large audiences. It is against such sociocultural and political backgrounds that the reception of the films Inxeba and Rafiki should be understood.

youtube

Inxeba was directed by John Trengove and was released in 2017. It tells the story of how queer sexuality is negotiated within the cultural space of ulwaluko, the Xhosa people’s rites of initiation into manhood. Two young minders engage in a gay relationship and a love triangle develops.

Rafiki was directed by Kenyan filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu. It centres on two young women who fall in love in Nairobi after meeting because their fathers are contesting the same election.

Inxeba presents picturesque images of the natural world. Rafiki offers a kaleidoscopic depiction of urban spaces. These vibrant and picturesque depictions contrast with the gloomy lived experiences of the protagonists.

State bannings

On its release, the South African Film and Publication Board banned Inxeba. The reason given, through a series of tweets, was “the perceived cultural insensibility and distortion of the Xhosa circumcision tradition (and) strong language in the film”.

Rafiki met a similar fate when it was released. The Kenya Film Classification Board said in a statement banning the film that its ending was “not remorseful enough, (making) it seem as if LBGT people can be accepted in Kenya”. The films were perceived as socially incorrect.

youtube

The reactions of these state boards highlight a reproduction of nationalist ideas that queer sexuality threatens African values. In thinking of these homophobic institutional reactions, it is important not to dismiss Africa as homophobic and primitive especially in relation to the West. In his book Kenyan, Christian, Queer, theology scholar Adriaan van Klinken explains that by considering Africa as backward and conservative there is a failure to reflect on the complex sociopolitical realities on the continent.

The upshot is that the legal measures of banning the films affected their circulation – both low budget films with seemingly limited distribution channels.

Viewers and festivals

Although Inxeba and Rafiki were banned in their home countries, they have received critical acclaim and numerous awards at film festivals the world over. In the case of Inxeba, there were vociferous threats and demonstrations, mainly by Xhosa-speaking men, who felt the film divulged the secrets of a sacrosanct ceremony.

The comments posted on social media platforms also make it possible to examine the reactions of viewers to the films. I illustrated this by focusing on the reactions expressed on Inxeba’s Facebook page. here’s a sample:

Reaction 1: “This is a disgrace to our culture…”

Reaction 2: “I didn’t like the story shame, I didn’t see the relevance. Sorry for being a party pooper.”

Reaction 3: “Thank you Lord … you have shown that you love us all regardless of what people are painting others to be, as if they do not belong or are just nothing.”

Using its YouTube page, Tuko TV Kenya interviewed Kenyans about Rafiki. Here is a sample of the diversity of views canvassed:

Reaction 1: “I think we are over exposing our children and our community … As a country, we are not ready for this.”

Reaction 2: “It’s a movie trying to include everybody into the society and bringing inclusion and diversity.”

Reaction 3: “I feel like the argument that it is influencing or promoting homosexuality to me feels ridiculous because that is not something that can be promoted.”

These reactions show that audiences are more complex than governments admit. Moreover, the reactions – and many others like them – prove that the films are popular social texts which operate to shape queer life and responses to it.

The screening of the two films (both were ‘unbanned’ on appeal – Rafiki for a brief period) has been important in initiating overdue conversations. Both films gesture towards the need for open discussion of queer sexualities and genders in Africa. They demand viewers to rethink not what it means to be queer in Africa, but what it means to be human.

Asking questions

Inxeba and Rafiki are invaluable additions to the growing corpus of African films courageously depicting queer lived experiences. Although initially banned, their reception by viewers in and outside Africa has shown that they can start conversations on diverse social issues relating to non-normative African gender and sexual identities.

Through evoking emotions of discomfort, the films compel audiences to question their own views and biases on gender and sexual identities. The films thus have the capacity to subvert homophobic tendencies embodied in state responses.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nollywood: how professionalism – and a new elite audience – is affecting it

by Ezinne Ezepue, Lecturer at the University of Nigeria

Director Kunle Afolayan and actress Genevieve Nnaji discuss the international rise of Nollywood at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival. Tara Ziemba/Getty Images

The Nigerian film industry, fondly called Nollywood, became popular in the early 1990s, although with more negative attributes than positives. Over the years, the industry has attracted a lot of criticism.

Some critics believe that the industry is quantity driven, while shunning quality. Others slated the industry for its budget restrictions, weak plots and repetitive dialogue.

But the most alarming criticism was focused on fatigue caused by movie overproduction. This fatigue was created by profit-driven filmmakers who churn out cheap, rushed movies on the regular. This wasn’t surprising given the fast growth of the industry. In the early 2000s, Nollywood went producing up to 50 films per week, with an annual total of over 2,500 movies.

This overproduction caused a saturation of the market and film professionals began to seek alternatives in order to produce quality films. Starting as early as 2006 the industry began to make movies with a new approach to everything. Films like The Amazing Grace, Ije and Through the Glass started a change in the diaspora. And on the home market, the new wave was domesticated with Kunle Afolayan’s The Figurine. Some filmmakers described this as their attempt to rescue the dying industry.

Filmmakers – among them Afolayan, Chineze Anyaene, Obi Emelonye, Stephanie Linus, Jeta Amata and Mahmod Ali-Balogun – began to adopt a different marketing strategy to amplify earnings. Previously, Nollywood was largely produced for the small screen and consumed mostly straight to video on VCD/DVD. The new marketing strategy took the consumption of Nollywood back to the cinema.

This marked a turning point for the industry.

The big changes

In 2013 President Goodluck Jonathan’s administration launched a 3 billion naira fund named Project ACT Nollywood, to support filmmakers. The fund was to help with capacity building and training for actors and filmmakers. It was also a vehicle for the establishment of film distribution platforms. This rejuvenated the industry, attracting young professionals in droves.

Nollywood’s transformation has since become huge, with films such as Kemi Adetiba’s The Wedding Party (2016) grossing record breaking figures at cinemas.

In my recent paper, I explore these seismic changes. I set out to answer what impact this revamping – from producing straight to VCD/DVD films consumed mostly by the masses, to an elite-targeted theatre distribution – has had on the industry.

Since 2010, some dramatic developments have changed the nature of Nollywood. They include an influx of professional filmmakers, the rise in international festival and cinema tours, international premieres, collaborations with multinational companies, Pan Africanism and distribution via multiplexes. In this time, a film’s release on VCD/DVD began to happen later in its life, effectively disenfranchising Nollywood’s traditional mass-market consumer base.

The questions I was interested in answering were: was the industry professionalising – in other words have Nollywood’s film makers become more specialised in their art? And was it gentrifying? Gentrification refers to the renovation and transformation of a neighbourhood, previously occupied by the working class, to suit the tastes of middle and upper class. I use the word metaphorically to explore whether Nollywood increased in grandeur, appeal and acceptance among Nigeria’s upper class.

The ability of Nollywood filmmakers to receive specialised training and improved knowledge meant that filmmakers’ perception of film and the creative process changed. It led to a new outlook – filmmakers became quality rather than quantity driven.

Veteran Nigerian filmmaker, Tunde Kelani poses for a portrait in Mumbai, India. Abhijit Bhatlekar/Mint/Getty Images

Budgets also got bigger. More money began circulating in the industry as corporate and institutional funders stepped in. Corporate funders became interested in the industry due to its increasing formalisation of practice and rising professionalism among practitioners. They also saw the potential of high profitability and return on investment. State and Federal governments are also showing increased interest in the industry.

The effects soon become apparent. Producers could now hire the best cast and crew. Nollywood films appeared more often at international film festivals. Filmmakers increasingly began to target the diaspora, as well as unlocking new strategies to garner international audiences. Overseas premiers became more common.

Media anthropologist Alessandro Jedlowski notes that targeting diaspora audiences was a way to overcome the fatigue in the industry which began to manifest from 2017. Entertaining the elite, diaspora and non-African audiences came with its own activities. They include the exposure of filmmakers through film schools, international workshops and personal developments, interaction with Nigerian filmmakers in the diaspora, as well as the exploitation of linkages and contacts.

But did this these transformations mean the gentrification of the industry?

Gentrification

The gentrification process generally increases cost of living as well as housing, forcing original residents of the neighbourhood to relocate to less expensive areas. This invariably leads to their displacement.

The use of gentrification as a metaphor is deliberate. I wanted to avoid exploring the rise in the cost of production as a result of the influx of new and wealthy film professionals. Or the displacement of filmmakers or audiences. Instead, I wanted to explore whether the acceptance of Nollywood among the upper class or elite had led to a loss of dominance among poor people.

I did not find any displacement of either filmmakers or audiences.

But I did find that Nollywood had moved to catering to upper classes as much as it catered for the masses.

I concluded that gentrification in Nollywood wouldn’t lead to any permanent displacements as two disparate filmmaking models co-exist. If any, I anticipate a temporary displacement at the point of consumption. But, since films eventually end up on DVDs, audiences that have been displaced from consuming films distributed via the theatres will finally get to consume them when they’re released on DVD.

The old and the new Nollywood

Nollywood currently has two broad business models – one that has come to be called the Old Nollywood. And the other, New Nollywood.

While some have confused these to be classifications for films and filmmakers, in reality, they are both business choices available to the Nollywood filmmaker.

Director-General of the WTO, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and Nigerian actress and filmmaker, Omotola Jalade Ekeinde. Jemal Countess/TIME/Getty Images

These models cater to different audiences while some filmmakers continue to explore and experiment with new distribution channels.

The interesting question is: can the changes be sustained?

At the University of Nigeria we’re trying to ensure that they are. We’re doing this by guiding students to create authentic African stories. Chris Obi-Rapu, director of the classic film Living in Bondage (1992), maintains that story is the bedrock, the foundation of every film. A film created from a faulty foundation is doomed, no matter how large its budget is.

As one of the recurrent points of criticism against the industry, we are contributing to Nollywood’s transformation by ensuring that future industry players and scriptwriters are equipped with creative ingenuities to conceive and produce screenplays which are authentically African, well researched and thoroughly entertaining.

0 notes