Photo

Some of Weegee’s photographs of movie-theater audiences, which he took with infrared film and no flash. Bad spectators. Via ICP.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Janet Malcolm on writer’s block, from The Silent Woman. Need to be content in the “close attic of partial expression.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

summer ‘18 beach looks

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Can’t wait for NYC to be these colors again. (Isabelle Huppert, c. 1980, NYC.)

0 notes

Quote

… Hempstead High School, he tells us, is a hub for MS-13 and Barrio 18. I go cold at hearing this statement, which he delivers in the tone one might use to talk about items in a supermarket. He’s afraid of Barrio 18 but doesn’t want to join MS-13, either, even though they are not as bad. Suddenly, we all suspect Manu and want to ask question thirty-seven: “Have you ever been a member of a gang? Any tattoos?” No, he has no tattoos. And no, he’s never been part of a gang. Indeed, it turns out Manu has good reasons to be afraid. Members of Barrio 18 beat him up. When he tells me about this incident, he is missing his two front teeth. Showing the wide gap and trying to joke about it, he says, I used to laugh at my grandma ‘cause she had no front teeth, and now I look in the mirror and I laugh at me. After the incident with Barrio 18, his aunt Alina worried he would end up in trouble because MS-13 boys saved him from losing the rest of his teeth, and now he owes them something. When I ask him about it, he says MS-13 in Hempstead wants him, yes, but he’s not going to fall for it. He’d rather disappear than joint them. Now more than ever. What do you mean by now more than ever, Manu? I ask. I mean now that my two cousins are here with us and I have to look out for them. Look out for them how. Just look out for them, ‘cause Hempstead is a shithole full of pandilleros, just like Tegucigalpa. Between Hempstead and Teguigalpa there is a long chain of causes and effects. Both cities can be drawn on the same map: the map of violence related to drug trafficking. This fact is ignored, however, by almost all of the official reports. The media wouldn’t put Hempstead, a city in New York, on the same plane as one in Honduras. What a scandal! Official accounts in the United States — what circulates in the newspaper or on the radio, the message from Washington, and public opinion in general — almost always locate the dividing line between “civilization” and “barbarity” just below the Rio Grande. A brief, particularly disconcerting article in the New York Times in October 2014 postulated a series of questions and rapid responses about the child migrants from Central America. The questions themselves has a tendentious tone: “Why aren’t child migrants 'immediately' deported?” one of them said, as if baffled or enraged by the fact that the children are not met at the border with catapults that will return them to their home countries. If the questions themselves showed a light bias, the answers were worse. They seemed like something from an openly racist nineteenth-century magazine or a reactionary anti-immigration serial, not the Times. “Under a statute adopted with bipartisan support, … minors from Central America cannot be deported immediately… [but] a United States law 'allows' Mexican minors 'caught' crossing the border to be sent back quickly.” (Note: the majority of children are not “caught” — they turn themselves over to Border Patrol.) Another question read, “Where are the child migrants coming from?” The answer: “More than three-quarters of the children are from mostly 'poor and violent' towns in three countries: El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.” The italics are mine, of course, but the underscore the less-than-subtle bias in the portrait of the children: children 'caught' while crossing illegally, laws that 'permit' their deportations, children who come from the 'poor and violent' towns. In short: barbarians who deserve subhuman treatment. The attitude in the United States toward child migrants is not always blatantly negative but generally speaking, it is based on a kind of misunderstanding or voluntary ignorance. Debate around the matter has persistently and cynically overlooked the causes of the exodus. When causes are discussed, the general consensus and underlying assumption seem to be that the origins are circumscribed to “sending” countries and their many local problems. No one suggests that the causes are deeply embedded in our shared hemispheric history and are therefore not some distant problem in a foreign country that no one can locate on a map, but in fact a transnational problem that includes the United States— not as a distant observer or passive victim that must not deal with thousands of unwanted children arriving at the southern border, but rather as an active historical participant in the circumstances that generated the problem.

from Tell Me How It Ends by Valeria Luiselli.

Happened to read this book today, after I spent the morning thinking about Trump’s “shithole countries,” and so I paused over Manu’s comment that “Hempstead is a shithole full of pandilleros, just like Tegucigalpa.”

0 notes

Quote

Call this the romance of disappointment. You want something. You have found an object that will give you what you want. This object is a person, or a politics, or an art form, or a blouse that fits. You attach yourself to this object, follow it around, carry it with you, watch it on TV. One day, you tell yourself, it will give you what you want. Then, one day, it doesn’t. Now it dawns on you that your object will probably never give you what you want. But this is not what’s disappointing, not really. What’s disappointing is what happens next: nothing. You keep your object. You continue to follow it around, stash it in a drawer, water it, tweet at it. It still doesn’t give you what you want—but you knew that. You have had another realization: not getting what you want has very little to do with wanting it. Knowing better usually doesn’t make it better. You don’t want something because wanting it will lead to getting it. You want it because you want it. This is the zero-order disappointment that structures all desire and makes it possible. After all, if you could only want things you were guaranteed to get, you would never be able to want anything at all.

from “On Liking Women” by Andrea Long Chu

0 notes

Photo

Something I wrote two years ago! Maybe one day I’ll write something again.

When these strangers described what they’d like to do to their version of me, it felt like making contact.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

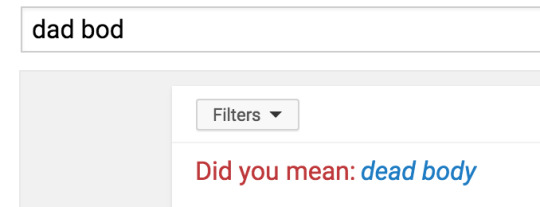

Feeling very “same” re: these spam-email subject lines.

0 notes

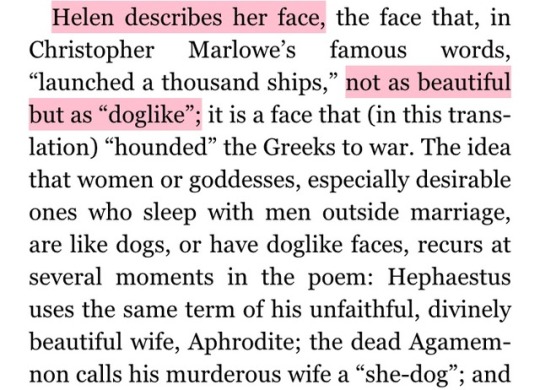

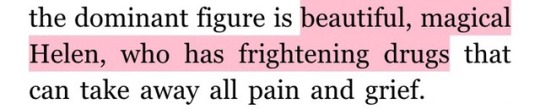

Photo

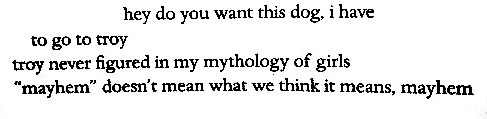

Introduction by Emily Wilson | Homer | The Odyssey

Bernadette Mayer | The Helens of Troy, NY

Introduction by Emily Wilson | Homer | The Odyssey

Anne Carson | An Oresteia | Orestes by Euripides

Kathy Acker | Don Quixote

Introduction by Emily Wilson | Homer | The Odyssey

Simone Weil | ”Let Us Not Begin Again the Trojan War”, quoted in Introduction by Christopher Benfey | War and the Iliad

Alice Notley | Doctor Williams’ Heiresses

Goethe’s Faust, quoted in Christa Wolf | A Letter, about Unequivocal and Ambiguous Meaning, Definiteness and Indefiniteness; about Ancient Conditions and New View-Scopes; about Objectivity | Conditions of a Narrative: Cassandra

Introduction by Emily Wilson | Homer | The Odyssey

2K notes

·

View notes

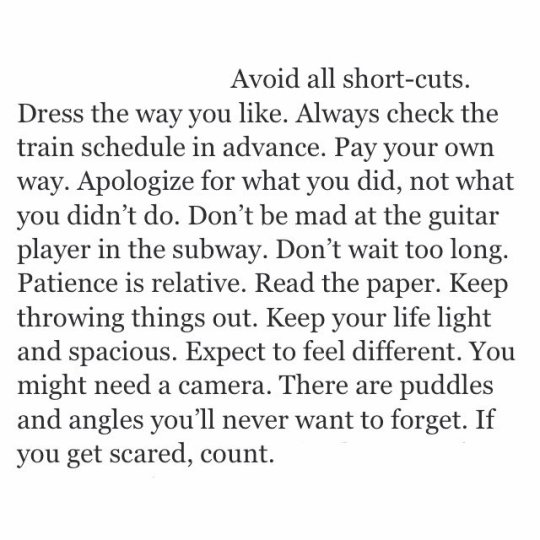

Quote

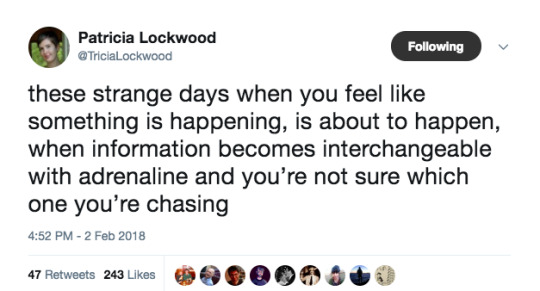

I sat in the computer chair and spun myself around once, twice: the child’s gesture of sudden and unsupervised freedom. Across the front lawn I saw blacktop, then the road, then the train tracks, then the tanks, then the river, then Kentucky. It looked like the seamed side of something — of the country, of industry, of American progress. Old modes of communication raced across the view, old ways of eating the miles. I turned the computer on and listened to the tower rev and wheeze. The monitor was capacious enough to hold a human head. I lifted my hands to the keyboard and opened up a window. I took a breath and eliminated the distance between two points. 'I wrote a poem today,' I typed to Jason, a total stranger who lived in Fort Collins, Colorado. We had met by chance, on a bulletin board devoted to the discussion of poetry, and were now in the grip of a fevered correspondence. 'It’s about Billie Holiday giving herself an abortion in a hot bath.' 'I wrote a poem today too,' he responded, not five minutes later. 'It’s about the splendor and the majesty of the tetons.' The feeling of getting an email! As if the ghost of a passenger pigeon had flown into your home and delivered it directly into your head, so swooping and unexpected and feathered was the feeling. How suddenly full you felt of white vapor. How you set your fingers on the keyboard to write back, and your fingers disappeared almost up to the first knuckle in those clattering beige keys — so much more satisfying than the shallow keys that came later, or the touchscreens that came even after that. The story of any courtship is one of ephemera, dead vehicles, outdated technology. Name cards, canoes, pagers. The roller rink, telegrams, mixtapes. Radio dedications. The drive-in. Hotmail dot com. 'Send me yours,' I wrote him, at the exact moment he responded to tell me to send him mine. Most of my poems were about mermaids losing their virginity to Jesus (metaphor), and most of his poems were about the majesty of canyons, arroyos, and mesas. The West had infected him with some sort of landscape mania — these were essentially poems a cartoon roadrunner would write, after retiring from a career of anarchy. He had, however, written one good image, which stays with me even now: 'the milk bottles burst like scared chickens.' It might strike you as irresponsible, to fall in love on the strength of one image about chickens bursting, but this was a different time. I didn’t even know what he looked like. He was under the mistaken impression that I was 'fifty years old and Latina.' We were all made up of words.

from Patricia Lockwood’s Priestdaddy

More email nostalgia.

0 notes

Quote

I didn’t know what e-mail was until I got to college. I had heard of e-mail, and knew that in some sense I would 'have' it. 'You’ll be so fancy,' said my mother’s sister, who had married a computer scientist, 'sending your e-mails.' That summer, I heard e-mail mentioned with increasing frequency. 'Things are changing so fast, Selin,' my father said when I visited him that August. 'Today at work I surfed the World Wide Web. One second, I was in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. One second later, I was in Anıtkabir.' Anıtkabir, Atatürk’s mausoleum, was located in Ankara, where my parents had gone to medical school. I had no idea what my father was talking about, but he lived in New Orleans and I knew there was no meaningful sense in which he had been 'in' Ankara that day, so I didn’t really pay attention. On the first day of school, I stood in line behind a folding table and eventually received an e-mail address and a temporary password. I didn’t understand how the e-mail address was an address, or what it was short for. 'What do we do with this, hang ourselves?' I asked, holding up the Ethernet cable. 'You plug it into the wall,' the girl sitting at the table said. Insofar as I’d had any idea about it at all, I had imagined that e-mail would resemble faxing, and would involve a printer. But there was no printer. There was another world. You could access it from certain computers, which were scattered throughout the ordinary landscape and looked no different from regular computers. Always there, unchanged, in a configuration nobody else could see, was a glowing list of messages from all the people you knew, and from people you didn’t know, all in the same font, like the universal handwriting of thought. Some messages were formally epistolary, employing 'Dear' and 'Sincerely'; others telegraphic, all in lowercase with no punctuation, as if they were being beamed straight from someone’s brain. And each message contained the one that had come before, so that your own words came back to you—all the words you threw out, they came back. It was as if the story of your relations with others were constantly being recorded and updated, and you could check it at any time.

from Elif Batuman’s The Idiot

One of a few nice instances of email nostalgia I’ve come across recently

0 notes

Quote

Pain is always new to the sufferer, but loses its originality for those around him ... Everyone will get used to it except me.

Alphonse Daudet, In the Land of Pain

0 notes