CineFiles-Ithaca hopes to engage you in the world of silent film -- the then and now of it. Stay tuned for monthly posts about silent movies from filmmakers, historians, culture critics, and film devotees, CineFiles-Ithaca is brought to you by Wharton Studio Museum, which is preserving and celebrating the role Ithaca, NY played in early American moviemaking,

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

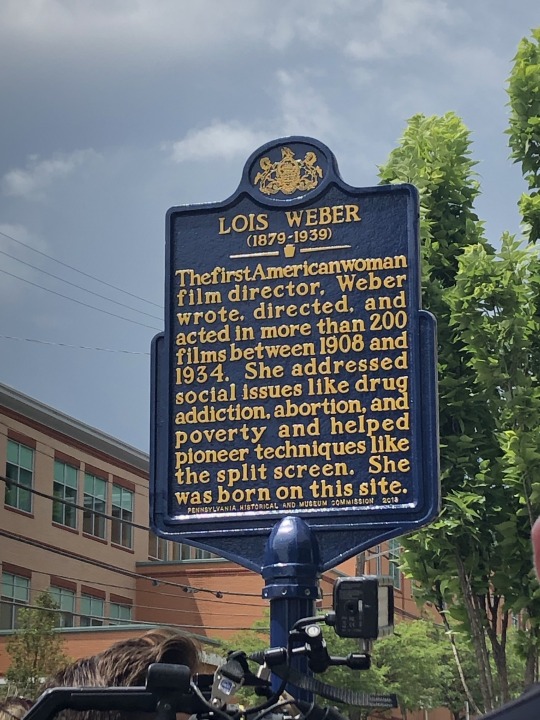

A Film Trail to Pittsburgh

As Silent Movie Month rages on for another week, I’m back at Ithaca College from a trip home to Pittsburgh for Fall Break. While there, I popped in to the Senator John Heinz History Center, where I worked last summer, to interview Lauren Uhl, Museum Project Manager and a curator at the Center, about her love of silent film actress, director, writer, and producer, Lois Weber (1879-1939). Weber, often considered to be one of the first American female directors, was born in Pittsburgh and spent the first twenty years of her life there. Last summer, the city celebrated Lois and her accomplishments in the film industry by putting up a historical marker in front of the Allegheny Carnegie Library where Weber’s house once stood.

Senator John Heinz History Center

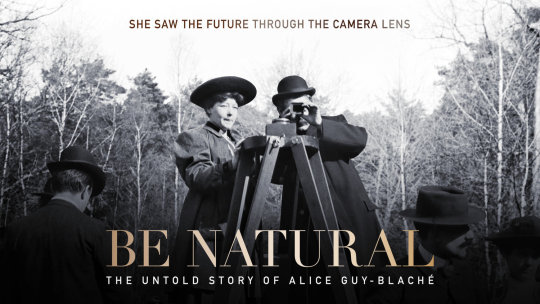

When I showed Wharton Studio Museum's executive director Diana Riesman the first draft of this blog post, she was excited to let me know that Lois Weber figured somewhat prominently in Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blache, the critically-acclaimed documentary directed by Pamela B. Green that WSM showed this past Wednesday night at Cinemapolis for Silent Movie Month. Alice Guy was making films in Paris in the late 1890s for Gaumont Studios, before coming to the States in the early 1900s, establishing her own studio -- Solax -- in Fort Lee, NJ, and writing, directing, and producing hundreds and hundreds of films, working with her husband Herbert Blache on numerous productions. Alice Guy's path coincided with Lois Weber's -- Weber acted in a number of Solax films, and allegedly had an affair with Herbert Blache. Weber is sometimes referred to as "Mrs. Smalley" in the documentary, since she was married to a director named Phillips Smalley.

Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blache, (Pamela B. Green, 2018)

But back to Lois Weber... Throughout our conversation Lauren makes it clear what drew her to Weber, why Weber is such an important person in the history of cinema, and why having communities claim these under-represented people in this industry is important. And she describes how the historical marker came to be plunged in the ground of Pittsburgh’s Northside:

Lois Weber

Rachael Weinberg: What was the process like of creating a historical marker for too many, an unknown person?

Lauren Uhl: Would you like the background? The Heinz Heinz History Center curators have been interested in documenting the film industry for so many years, and it was probably about five years ago I ran across the name Lois Weber. I found that she was one of the first female American directors and she was from Pittsburgh. I just couldn’t believe, I had never heard of her before. I love silent film, and I have been in the Pittsburgh history business for 30 years, and I never heard of her. I found that really fascinating and, at that time, even five years ago, there wasn’t a lot of information about her really anywhere. But, not long after that, I heard through the grapevine that Pitt [University of Pittsburgh] was hosting some women in Silent Film Program, and someone named Shelley Stamp was coming, and she had been in the process of writing a book. I asked if we could go, they agreed, and Shelley said in passing, “I’ve always wanted to get a historic marker for Lois in Hollywood.” When she said that I thought, “Jeez, we should do that here.” That is something the History Center could sponsor, that I could work on, and nobody in Pittsburgh knows who she is. It became a tangible thing to do for this anamorphosis project, this documentation project that we are trying to do. I talked to a few people to my colleagues and boss, because it would cost some money, and I got the green light. I contacted the state about paperwork, and to see what I needed to do and how much money it would cost, but I kept on getting green lights. And that was sort of the genesis of the idea of it. It seemed like a tangible thing, it would last beyond program. It would be a permanent fixture in the city and something we could turn too, and it seemed like a good starting space for the project.

Shelley Stamp

RW: So you say you, “kept on getting these green lights”, but were there any issues along the way?

LU: Surprisingly there weren’t. I think it was because it went under the radar, so it flew over the heads of those in a lot of power. Plus, the cost of the marker was only $1,600, which was not inconsiderable, but in the scheme of things, it wasn’t major money. It was just kinda me sitting in a corner in my spare time. Fortunately, by the time it started to roll out, Shelley’s book came out. I used it as my background source, so I read that as fast as I could. Then I could write about Weber and her importance.

Scene from Suspense (Lois Weber, 1913), showing a custom vignette

RW: Shelley Stamp and Illeana Douglas were the two keynote speakers, what was it like working with them and how did you get that to all come together?

LU: It was marvelous. I look back and call it my Lois Weber day, where everything goes right. Shelley Stamp was the obvious one, because she was the academic and she wrote the book. When we first saw Shelley she was doing an academic lecture on Lois’s film. We wanted this to be a conversation and not a lecture, about not only Lois and her importance in the film industry, and I wanted it to reach beyond that. I had seen Illeana a number of times on TCM, she is an actress, director, and producer as well. But also she is such a good interviewer, that it would be more of the conversation than lecture. I knew Illeana would come with a price tag. I figured that Shelley would just need to come here, but I knew Douglas would come for a pause. I wasn’t sure how much it would cost and how to get in contact with her. I went to her website, I called her personal appearance person and they never responded. A few days later, I emailed her agent and one night he called, and I had a nice conversation with him, and he gave me a price tag, which wasn’t outrageous. I went to education, and said that there was this price tag and they said, “okay, we will give you the money.” So then it was just logistical: making sure they could both come at that time. But she was available to doing it. So everything worked out as best as I could recommend.

Illeana Douglas

RW: How did watching Weber’s work influence you? She is a revolutionary.

LU: She truly was. But it was, at first, hard to find. What I was impressed with was that she was an amazing filmmaker. You always say the first, but she wasn’t just the first she was really good. She was a really good filmmaker. Her films had a lot of heart to them, which is unlike today. She had a way of taking moral tales and thoughtful stories, and hard subjects like abortion or wage inequality and have you think at the end of them. Because they were good stories and good films. She was able to package all of these things I love and lift them up cinematically, and they were silent. She didn’t have sound. And she was able to blaze a trail in how to create film. I was even more amazed that she grabbed this medium and made it her own. By god, she was going to do the stories she wanted to tell, own a studio, and she had this matronly personality that made her easy to love. She was getting her point across, but in a matter that was not offensive, even if you disagree with her.

RW: For sure. She was born in Pittsburgh, but she never worked in Pittsburgh, right?

LU: Yes, she never filmed in Pittsburgh, but she did grow up here. She spent the first 20 years of her life here, so she was formed in Pittsburgh, but never created here.

Poster for The Blot (Lois Weber, 1921)

RW: What does that tie all the way back to the silent era mean to your project?

LU: She is foundational, but she is not the only one. We claim the Nickelodeon, the Warner Brothers get their start in Western Pennsylvania. They figure out that distribution is where the money is. Then as Edison and his patent people come here, they move west. Edwin S. Porter was born here (Great Train Robbery). So it is lovely to have a woman, because it provides balance, but there were a lot of these greats getting their starts here.

RW: That leads me to my next question… Yes, we have all these men, but what does it mean to have a woman. Especially a woman who was talking about sobriety and sex and prostitution, what does it mean to have that voice?

LU: It is interesting to me, because, personally, I am a Christian, so is comes from that world view. She was a missionary and Christian, so that comes into her world view. My understanding was that she was a missionary in Pittsburgh and New York, what that also brings to the table is it gives us an understanding of what Pittsburgh was like when she grew up here. That falls through the cracks of history. It is easy to talk about Andrew Carnegie and immigrants, but Lois could take these real life problems in Pittsburgh, which I’m sure happened everywhere else, but putting them on the forefront. She was able to use her Pittsburgh background to tell these stories. In some way it leaves Pittsburgh into these tales without explicitly saying “Pittsburgh”.

RW: What else are you doing to keep Lois alive in house?

LU: For Lois, physically, nothing in particular, but whenever I have the opportunity, I will try to invoke her. Especially since next year was the centennial for women getting the right to vote. So I will try to fit Lois whenever she fits. The other thing I would love to do, is i would like to honor her on an annual basis by having a lecture or conversation. In my mind it is two things: One would be with a Pittsburgh filmmaker, and the second would be a person who isn’t from Pittsburgh but exemplifies Lois. So that would be the way that we would keep her name in front of the people.

RW: You named a lot of other silent players. How are you incorporating those?

LU: When people say exhibit they think of large objects, but the other curators and I would love to do other things for the exhibit, like blogs and films and events. But right now we are also looking for the tangible pieces of these people, but we also thing “Can we find a photograph? Can we find a lobby card? What are other ways to incorporate these people?” And past. I don’t just want this to end either. I want this to grow into something larger whether that is traveling or putting pieces in our permanent collections. We just want to grow and allow for this to keep spinning.

RW: Why is it important for us to remember these women and these marginalized people in film to allow for their stories to be told, or retell their stories?

LU: I can think of two things. The first was when I was in college and I was working in the Henry Ford Museum. It was still old school, and they just had aisles and aisles of objects. I remember sitting there and thinking, these are my people. What do you learn in history class? Washington, Lincoln, the Depression? And I’m thinking, “My people aren’t even completely marginalized. They’re the German Irish, but they aren’t in the history books.” So I want to tell these stories of all of these marginalized people and give them a sense of belonging. The second part comes down to the fact that other people came before you, and it goes back to something that Shelley said. When Illeana asked Shelley something similar she said, “I’ve got this girl in my screenwriting class who thinks that she nobody has ever done it before, and that she needs to blaze the trail. She doesn’t. Women have been writing for over 100 years. It’s going to be harder for you as a woman. It always will be, but there are people who came before you and people who will come after you.” That’s one of the fascinating things about history. You don’t have to feel bad about being the cog. Lois did this 100 years ago meaning that you can do this too. So let’s keep honoring them and keep reminding people of them, so they can also see how this industry and any industry hasn’t always just been part of hegemony.

Scene from Suspense (Lois Weber, 1913)

-Rachael Weinberg, Museum Division Intern

0 notes

Text

A Walk Through the Park with Wharton Studio Museum!

This past weekend, Wharton Studio Museum helped lead a historic tour through Stewart Park in partnership with Friends of Stewart Park. The guided tour was put on by Historic Ithaca. The lovely and intelligent Diana Riesman and Rick Manning took about 30 people through Stewart Park, showing off numerous bits of history Ithaca has to offer. Interestingly enough, Stewart Park – which was known as Renwick Park a century ago -- was the home of the original Wharton Studio, meaning that we got to see remnants from the past, and document how far we have come in over 100 years.

The tour began at a Trail Head on the Cayuga Waterfront Trail and then moved on to the Picnic Pavilion, built in 1896 and designed by Vivian and Gibb, two young Ithaca architects. Next stop was the Dance Pavilion, sister building to the Picnic Pavilion and where live music would play during the summer and early fall. The pavilion would go one to host Vaudeville acts, and by 1906, it was turned into a roller rink. Drawn by the park’s natural beauty and proximity to beautiful Cayuga Lake, in 1915 the Wharton brothers – Theodore and Leopold – leased over 35 acres of Renwick Park (now Stewart Park) and decided this building would be where they would set up their movie studio. While they built exterior stages and sets, here inside the studio building, they constructed sets, and had enough space to have multiple sets used at the same time. There was no need for “Quiet on the set!” since the films were silent! This is where some of the most popular serials of the day -- Romance of Elaine and Beatrice Fairfax -- were shot. The Whartons attracted some of the best-known actors of the day to Ithaca – Irene Castle, Lionel Barrymore, and a young Oliver Hardy – to work for their studio, locals were hired as set designers, cinematographers, costume designers, etc. and they were asked to work as extras on the films. The Whartons directed and produced dramas, comedies, and WWI propaganda films, and their popular serials were seen throughout the country, Canada and Europe. By 1920, the Wharton Brothers would have moved out of this studio, but they left an important legacy as pioneers in what was a new industry, and they put Ithaca on the map as a center of filmmaking.

Farther down the Waterfront Trail was the Tea Pavilion, which was a trolley stop and concession stand. Here people would be able to enjoy piping hot tea and bread as they looked out at scenic Cayuga Lake. We also stopped by the Cascadilla Boathouse, which was created in 1893 as a gym for the Cascadilla School, and the boathouse is currently the home of the Cascadilla Boat Club. A beautiful building, with balconies, its exterior, which is badly in need of re-painting, will be painted and its trim re-done next year, thanks to a grant from NYS. This building is on the National Register of Historic Places and we are super excited to see what comes from it in the future.

Beyond these sites, the Friends of Stewart Park is continuing to improve upon the park, by creating a more accessible playground for children of all needs and focusing on creating winterized bathrooms. (There are none at the moment!) Wharton Studio Museum is proud to be partnered with organizations like Historic Ithaca and Friends of Stewart Park, which are working to make this beautiful public park a more inclusive and accessible place for everyone.

While we won’t be diving to the bottom of Cayuga Lake any time soon to retrieve any reels of film that urban lore proposes might’ve been thrown in to the lake, WSM does plan on hosting more events in and around the historic Wharton Studio building.

Join us this coming weekend in Stewart Park for The Missing Chapter a headphone walking-play set against the backdrop of the Wharton Studio era. It’s back by popular demand. We would love to see you there. Tickets available at thecherry.org.

As always, please follow us on Facebook and Instagram, and feel free to reach out with any silent film related information or interests you have!

-Rachael Weinberg, Museum Division Intern

0 notes

Text

Welcoming “Silent Movie Month” with a New Exhibition Home

“Romance, Exploits and Peril” presents some of the more prominent players from the Wharton Studio era: from Doris Kenyon, an actress and musician in films like Monsieur Beaucaire (Sidney Olcott, 1924), to Olive Thomas, a silent film actress and model who married Jack Pickford (brother of Mary Pickford, one of the founders of United Artists Studio) and made her screen debut in episode 10 of the popular 1916 Wharton serial Beatrice Fairfax. Of course, the exhibit goes far beyond just these two stars, and quite literally “frames” many other of the studio’s players for the public to uncover them in a new light.Hello Cinephiles and welcome back to CineFiles! To kick-off October and Silent Movie Month — its 8th year — Wharton Studio Museum just re-located our exhibit titled ”Romance, Exploits and Peril” to the Tompkins Center for History & Culture on the Commons in downtown Ithaca.

The exhibit, which spent the summer on display at Gimme! Coffee on W. State St. (it previously hung at Gimme in 2011 when it was first produced), now lives proudly alongside the ramp just beyond the Atrium of the TCHC.

The installation took place this past Monday night with the help of WSM’s amazing designer Joe LaMarre, whose design firm Uncommonplace is in Trumansburg.

“Romance, Exploits and Peril” presents some of the more prominent players from the Wharton Studio era: from Doris Kenyon, an actress and musician in films like Monsieur Beaucaire (Sidney Olcott, 1924), to Olive Thomas, a silent film actress and model who married Jack Pickford (brother of Mary Pickford, one of the founders of United Artists Studio) and made her screen debut in episode 10 of the popular 1916 Wharton serial Beatrice Fairfax. Of course, the exhibit goes far beyond just these two stars, and quite literally “frames” many other of the studio’s players for the public to uncover them in a new light.

Join us this Friday, October 4th from 5-8pm as we will be holding a Gallery Night celebration of this exhibit at the Tompkins Center for History & Culture. There will be very light refreshments, and you can speak to WSM’s executive director, Diana Riesman, meet me, and explore the main Exhibit Hall where The History Center has all its displays, and where Wharton Studio Museum has its permanent exhibit on Ithaca’s role in early filmmaking.

So come celebrate with us, and learn more about the Wharton’s history here in Ithaca and the amazing silent films that were created right under our noses.

Visit whartonstudiomuseum.org for a calendar of all Silent Movie Month events happening this October, such as Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blache screening on October 23rd at Cinemapolis! After the film, director Pamela B. Green will join us via Skype to partake in a Q&A and illuminate us about Guy-Blache’s incredible life as a film pioneer.

- Rachael Weinberg, Museum Division Intern

0 notes

Text

Welcome Back Cinephiles!

Since Silent Movie Month is about to begin, I am thrilled to re-launch the CineFiles blog once again for the fall semester. This blog, sponsored by the Wharton Studio Museum, is about anything and everything silent film related, from the stars scandals, to the technology, the music accompaniment, reviews, and more! Throughout the next few months, I hope to speak with some silent film lovers and experts to illuminate us with even more silent film history.

But first, let me introduce myself. My name is Rachael Weinberg, a junior at Ithaca College getting a dual degree in Art History with the museum concentration and Cinema and Photography with the cinema production concentration. I’m super grateful and excited to spend this semester interning at the Wharton Studio Museum. As someone who describes themselves as a visual storyteller and a scholar, it seemed like a perfect fit for me to work with the Wharton this semester. As a Pittsburgh native, community has always been something I was proud to share. Once I joined the Ithaca College community, the town of Ithaca as a whole, became a community that I deeply cared about. Once I realized that visual storytellers stationed in Ithaca creating film before the creation of sound, it made me realize that I needed to look beyond the campus and learn more about this rich history. That is why I am so excited to work with the Wharton Studio Museum this semester! I have worked as a writer, director, and producer of several short films. I have also written extensively about feminism in horror movies and frontier masculinity, and hopefully soon, about the forgotten female directors of the silent age. Diana Riesman, WSM’s Executive Director, has allowed me to have free rein with this, so I hope to make it interesting and relevant. This blog will be an amalgamation of expanding my scholarship, interviewing experts, and sharing why we still love silent film.

This past summer I worked with the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where I am from, doing research about Pittsburgh’s connection to Hollywood and the movies. During my time there, I helped with presenting a historical marker in Pittsburgh for one of the first silent film directors, Lois Weber. She was a pioneer not only technically, but also through sharing controversial topics on screen like divorce, prostitution, sexual transgression, poverty, and the mistreatment of minority groups in the United States. It was an honor to be a part of recovering Weber’s history and connecting her immense work and influence on the film industry with my own city. A close connection to the makers geographically and historically is yet another reason why I am so excited to work with the Wharton Studio Museum this semester.

Photo 1: Lois Weber Marker

Also -- did you see that we are showing BE NATURAL: THE UNTOLD STORY OF ALICE GUY BLACHE on October 23td at Cinemapolis here in Ithaca?

Guy-Blache was a pioneer as a director and head of a production studio! Similar to Lois Weber, she was a true pioneer and is having a resurgence.

So join me over the next few weeks learning more about cinema, listening to experts gush about their favorite movies, and learn a little more about the history of silent film here in Ithaca!

If you have anything you’d like to share or engage with us, please feel free to email me at [email protected]! I would love to hear from all of you!

Photo 2: Lois Weber impersonator and me at the historical marker

0 notes

Text

Doris Kenyon

March has come to an end which means so has Women’s History Month. We’re closing off our series on CineFiles celebrating Wharton women with none other than Doris Kenyon!

Doris Kenyon was born in Syracuse, NY in 1897 and sang in choirs in Brooklyn when she was recruited to perform on stage, making her acting debut in the opera The Princess Pat in 1915. She then started her film career with the World Film Company and was best known for starring opposite Rudolph Valentino in Monsieur Beaucaire (1924). Kenyon is also notable for The Great White Trail (1917), filmed in Saranac Lake, directed by Leopold Wharton and produced with his brother Theodore Wharton. She smoothly transitioned to talkies in the 1930s and retired after The Man in the Iron Mask (1939). Doris Kenyon died in 1979 in Beverly Hills, California.

0 notes

Text

Marguerite Snow

Marguerite Snow (1889-1958) began her acting career on stage in 1907 before transitioning to the screen with New Rochelle’s Thanhouser Film Corporation in 1910. She played an incidental role in one of its productions and was discovered by a director who wanted her to play the lead in a feature. This skyrocketed her career and Snow became one of the best-known actresses of the silent film era.

Marguerite Snow worked with The Whartons, Inc. before the studio went into financial turmoil. Audiences during the end of World War I was losing interest in war-related content. She played the leads in its last serial The Eagle’s Eye (1918) and The Mission of the War Chest (1918). Snow’s career declined with the introduction of sound to film. She died of kidney complications in 1958.

0 notes

Text

The Modern “It Girl”

Irene Castle (1893-1969) began her career as a dancer and became half of a ballroom dance duo with her husband Vernon Castle. They created their own dances such as the “Castle walk” and also brought social acceptance to others like ragtime jazz. In 1918, Vernon tragically died in a plane accident and Irene married Ithaca local Robert H. Treman a year later.

Irene Castle was also a fashion icon. She wore her hair short which was often stylized with a pearl headband or feathered hat - influencing the flapper look before it became popularized in the 1920s. As if that wasn’t enough, Castle expanded her talents to include acting when she made her film debut in Patria (1917), a 15-part World War I propaganda serial by the Wharton brothers and financed by William Randolph Hearst. Anything but a “Gibson Girl,” Irene Castle was the premier exemplar of a modern 20th-century woman.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heroine of a Thousand Stunts

Pearl White (1889-1938), dubbed “Peerless Fearless Girl” and “Heroine of a Thousand Stunts” was the queen of serial films and notorious for doing her own stunts. She acted in several films prior to being hired by the American branch of Pathé Frères, a French film company, to star as the titular character in The Perils of Pauline (1914). After achieving breakthrough as Pauline, she continued to gain success doing serials. She was also best known for her role as Elaine Dodge in The Exploits of Elaine (1914), The New Exploits of Elaine (1915) and The Romance of Elaine (1915), which were directed by Louis J. Gasnier, George B. Seitz, and Leopold and Theodore Wharton and produced by Wharton Studios. Pathé distributed the films and brought international fame and recognition to Pearl White. Though White’s career didn’t transition well in the 1920s during the rise of feature films, she made enough money to retire and live a luxurious life in Paris until her death.

#pearl white#serials#silent film#whartonbrothers#whartonstudio#elaine#pauline#stunts#womenshistorymonth

0 notes

Text

WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH KICKOFF

Happy Women’s History Month! Throughout the month of March, we’ll be highlighting notable women of the silent film era, who worked with the Wharton Brothers and their studio or was associated with Ithaca in some way.

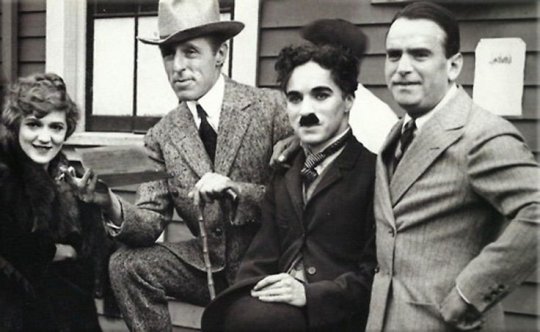

We’re kicking off this series with none other than Mary Pickford, who started in the industry when it was just developing and helped shape it into what it is today.

Mary Pickford (1892-1979) was a pioneer in early cinema as an actress, producer, and businesswoman. Deemed “America’s sweetheart,” Pickford’s stardom began in theatre before going into film after meeting director D.W. Griffith of the Biograph Company. Throughout the 1910s, she worked with various studios, generating fame and success, allowing her to get paid more than the standard at the time and gaining control over the productions of her films. One of her most notable works is Tess of the Storm Country (1914 and 1922) based on the novel by Ithaca native, Grace Miller White. Pickford starred in her last silent film, My Best Girl (1927), before transitioning to making talkies - winning an Oscar for Best Actress in Coquette (1929).

In addition to acting, Mary Pickford was also a film producer and philanthropist. She founded an independent distribution company, United Artists, in 1919 with other early film trailblazers: Charlie Chaplin, D.W. Griffith, and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. She helped form the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and created the Motion Picture Relief Fund, an organization that provided assistance to those with financial needs and limited resources. For all her achievements and contributions to the film industry, Mary Pickford received the Academy Honorary Award in 1976.

#mary pickford#united artists#silent film#wharton brothers#wharton studio museum#ithaca#oscars#academy of motion picture arts and sciences#charlie chaplin#d.w. griffith#douglas fairbanks#pickfair#coquette#tess of the storm country#grace miller white#biograph company#americassweetheart#march#womens history month#mybestgirl

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

WE’RE BACK IN ACTION!!

Hello Fellow Cinephiles!

I’m glad to announce the re-launch of CineFiles, Wharton Studio Museum’s blog about film history and preservation, music and silent film, and anything in-between related to movies.

As an Ithaca College art history major with a concentration in museum studies, I’m excited to be spending my last semester at IC interning at the Wharton Studio Museum! My interest in film began in high school where I took film and animation classes, as I sought to express my thoughts through visual storytelling. Since then, I’ve produced and written several short films. Through interning at WSM and learning more about the Whartons and their movie studio in Stewart Park, I hope to help highlight this significant piece of American film history that brought so much to Ithaca and to people across the country and the oceans who watched the Whartons’ movies a hundred years ago. I’m looking forward to taking on CineFiles as a project! Diana Riesman, WSM’s Executive Director, gave me the title of Production Coordinator, so with that in mind and with this post, I am officially kicking off the re-launch of CineFiles!

I envision CineFiles as a platform to express ideas related to film and the passion for it that we share. So if you’re a film professor, historian interested in culture, fashion designer always paying attention to the costumes in a movie, a musician who loves film scores or someone who just loves watching movies, I hope to hear from you!

Now it is your turn to blog! Send your posts to [email protected] with your name, title (if you want) and email address.

I’ll be generating prompts along the way to engage you in all things silent film, Wharton brothers, Wharton Studio Museum, etc., and hope CineFiles will become an informal but engaging archive of ideas and knowledge.

Looking forward to hearing from you!

Suzanne Tang

Production Coordinator

CineFiles

Wharton Studio Museum

#film#film history#film preservation#silent film#cinephile#ithaca#wharton brothers#whartonstudiomuseum#stewartpark

0 notes

Text

#OscarsSoWhite

THE ACADEMY AWARDS 2016 “WHITE-OUT”

“Tonight we honor Hollywood’s best and whitest—sorry, brightest.”

Neil Patrick Harris, Oscar host, 2/22/15

It has been more than seventy-five years since Hattie McDaniel became the first black movie star to win an Academy Award. She won that “Best Supporting Actress” award for her 1939 performance as Scarlett O’Hara’s “Mammy” in Gone With the Wind. The following spring, the Academy Awards were held at the famed Cocoanut Grove nightclub in the Ambassador Hotel in Beverly Hills, California. It was the 12th Annual celebration of the Academy Awards, and most of Hollywood’s biggest names were there, including her co-star Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, and Olivia de Havilland.

But Hattie, who was a close personal friend of Clark Gable, did not sit at the table with the rest of her Gone With the Wind cast. The hotel was segregated: so Hattie and her escort sat alone, at a solitary table, in the back of the ballroom. In fact, Producer David Selznick had to call in a special favor just to allow her to enter the hotel. Like so many other Oscar-winning actors and actresses, she would go on to have a long and distinguished film career. But unlike her white counterparts, for whom the prestigious acting award provided opportunities to play a wide variety of roles, Hattie found herself cast in the same part over and over again: alongside Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus (1932), with Katherine Hepburn in Alice Adams (1935), with Mae West in I’m No Angel (1933), with Shirley Temple, in The Little Colonel (1935), with Irene Dunn in Showboat (1936), with Oliver Hardy in Zenobia (1939), and in Walt Disney’s Song of the South (1946). And when Hattie finally made the big leap to the new medium of television, she played . . . Beulah, the maid. As a black woman, Hattie became the embodiment of Mammy, the loyal domestic, one of the most enduring—and one of the most pernicious—black stereotypes that limited and restricted excellent and highly-talented black performers to servile roles in Hollywood film

It would be another twenty-three years before Sidney Poitier would become the first black actor to claim the coveted award for Lilies of the Field (1963), and another fifty years before Whoopi Goldberg would become the second woman to win an Oscar, for “Best Supporting Actress” for the blockbuster Ghost (1990). But even those awards were not without their own controversies, with some critics and viewers arguing that Poitier’s role as a self-sacrificing, unpaid handyman to a group of white Belgian nuns who are trying to build a church—like Goldberg’s ghost-fearing con artist Oda Mae Brown—were simply modernized version of old familiar stereotypes. Nonetheless, hopes for long overdue recognition of blacks in the industry were high and they remained high, especially after the 2002 Oscar wins by Halle Berry (as the first-ever African-American “Best Actress”) and Denzel Washington (only the second black actor, after Poitier, to win “Best Actor”—and the only black performer to be a two-time Oscar winner) and the Best Supporting Actress” wins by Mo’Nique (Precious, 2009), Octavia Spencer (The Help, 2011), and Lupita Nyong’o (Twelve Years a Slave, 2013).

While a handful of black actors would be recognized by the Academy for their work—Lou Gossett, Jr., for An Officer and a Gentleman (1982); Cuba Gooding Jr., for Jerry Maguire (1996); Morgan Freeman, for Million Dollar Baby (2004), Jamie Foxx, for Ray (2004), Forest Whitaker, for The Last King of Scotland (2006), Jennifer Hudson, for Dreamgirls (2006)—many more fine performers would be neglected or overlooked. In fact, in Oscar history, it was only in the musical categories (“Best Original Score” and “Best Original Song”) that blacks seemed to make a consistent impact.

Now, the second consecutive year of a complete shut-out of performers of color in the major actor categories has focused renewed attention on longtime Hollywood practices. But in order to appreciate fully the so-called Oscar “White-Out,” it is essential to understand the long history of black representation and misrepresentation in the dominant white industry that gave rise to the disturbing tendency toward black erasure. For years, even decades (and, in some cases far longer than that), the roles that black performers could enact in Hollywood movies were severely restricted. As studies of cinema history have confirmed, the earliest filmic images of blacks derived from the racist minstrel shows and blackface stage performances of the late nineteenth century. Consequently, black actors/actresses were relegated to minor and demeaning types—or, more correctly, to stereotypes, among them self-sacrificing “Uncle Toms,” loyal “Mammies,” tragic and often vengeful mulattoes, brutes, “Jezebels,” and foolish “pickaninnies.” Through their repetition on screen, these stereotypes became etched in the American imagination.

By their very nature, the degrading roles not only relegated black performers to the background; they also contributed further to the sense of black erasure in cinema. In some cases, that erasure was literal: in parts of the South, for example, entire production numbers featuring black performers would be cut from films in order to placate white audiences who did not want to see black entertainers showcased in prominent roles. Similarly, the printed programs and publicity booklets that the studios distributed to promote their releases often excluded photographs of black actors, who might not even be listed in the production credits.

Black absence also extended to the theaters where mainstream white films were shown. Since segregation practices ensured that most movie houses accommodated only white patrons, blacks were restricted to off-hour movie screenings called “midnight rambles”; to the “Colored Only” sections of select theaters—pejoratively called “buzzard’s roosts”—which they entered and exited through separate doors away from the view of whites; or to black theaters, sometimes called race or ghetto theaters, which opened to accommodate the new black audiences but struggled financially to survive. In fact, as late as 1929, when Hallelujah, one of Hollywood’s first all-black-cast musicals, was released in New York City, it premiered simultaneously at two very different venues: the downtown Embassy on Broadway for white filmgoers and the uptown Lafayette Theater in Harlem for blacks. The dual premiere allowed white audiences the comfort of watching scenes of black song, dance, and revivalist religion at a safe remove—that is, without having to engage with actual blacks. (Theater owners typically defended segregation in some utterly outrageous incredible ways: for example, by arguing that black moviegoers had a different “smell” that offended sensitive female patrons, which warranted their separation from white moviegoers.) Discrimination was also evident in the disproportionately low salaries that many black actors were paid by the major studios and in the humiliating treatment they received, both on location, where they would be forced to seek substandard segregated accommodations, and on the lots, where they were consigned to special areas for their breaks and rarely allowed to socialize with their white co-stars.

Early movies in general—and D.W. Griffith’s racist classic The Birth of A Nation (1915) in particular (a film closely allied to the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915)—underscored the racial and social divide, reinforced the racist characterizations, and concretized the impression of blacks as ludicrous, subservient, and cartoonish. Unfortunately, the lack of a strong visual past made it difficult for blacks to counter the gross distortions. So the demeaning and inauthentic imagery of blacks persisted, repeated (albeit sometimes in more subtle or modern ways) by new generations of filmmakers.

One important development (and counter-movement) in cinema history deserves special mention and attention here: the evolution of the “race film” industry in the early decades of the twentieth century. From the mid-1910s through the end of the 1920s, independent race producers committed themselves to addressing the concerns of the neglected but steadily-increasing black market by creating a new genre of films. Their so-called “race films” were—quite simply—films aimed almost exclusively at black audiences, featuring black actors and centering on black themes and issues. Important race filmmakers such as George and Noble Johnson, Oscar Micheaux, and Richard E. Norman determined to present realistic depictions of black Americans by creating an alternate set of cultural referents and by establishing new black character types and situations, particularly those that reflected social changes. As one early race filmmaker observed: unlike white moviegoers, who had long “based their idea of a Negro on the Stepin Fetchit [character,] the Negro himself was tired of seeing that type of picture. He wanted to see himself as he really was.”

As products created by and for their black community, race movies became a way of producing images that didn’t go through white culture. Seen by blacks, largely unseen by whites, race movies featured an all-black world—one with which black moviegoers could readily identify. Through their landmark Lincoln Motion Picture Company, the Johnson brothers produced films such as The Realization of A Negro’s Ambition (1916) and Trooper of Troop K (1917), in which aspiring and well-educated blacks served their community and their country as they pursued—and achieved—their own ambitions of family happiness and professional success. And Norman’s seven feature-length films starred some of the best race actors of the day—many of them drawn from the theatrical ranks of the renowned Lafayette Players—who assumed roles of “uplift and ambition” as teachers, doctors, superintendents, engineers, ranchers, advertising directors, oil men, even aviators.

Unfortunately, race films did not, by any means, shatter the racial clichés or halt the negative imagery that dominated American film. In fact, with the advent of sound in film and the newfound interest of Hollywood in “Negro-themed” pictures in the 1930s, most of the early independent race producers were forced out of the business. Nonetheless, the alternative to contemporary racist depictions that they provided and the challenge that they issued to their fellow filmmakers to create more balanced racial and ethnic portrayals were undeniable—if, regrettably, still not fully realized.

What, then, do these historical lessons about types and anti-types teach us about the color barriers, implicit or explicit, that exist in Hollywood today? This, above all: that change, though slow in coming, is certainly possible—but only if people of color are afforded better opportunities in front of and behind the camera and if black actors are given less restrictive and retrogressive roles. As Viola Davis noted after her historic Emmy win as the first African-American “Best Dramatic Actress “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity. . . . You cannot win an Emmy for roles that aren’t there.” Clearly, that sentiment is true of the Academy Awards as well.

To be sure, the recent Oscar backlash has had a notable effect: the Academy, forced to confront and to address diversity issues, has just committed to doubling the amount of “women and diverse members” by 2020. That is certainly a good start. But the real antidote to the Oscars’ “White-Out” is color-blindness—that is, a long-term concerted effort by producers, directors, writers, and Academy voters to promoting and recognizing talent regardless of race or gender and to creating rich, meaningful, and non-regressive roles that allow all actors, including (and perhaps especially) actors of color, to participate in the wonder that is cinema.

-- Barbara Tepa Lupack

Barbara Tepa Lupack is a former Fulbright Professor, dean at SUNY/ESC, and the author and editor of numerous books on American literature, film and culture. She is a “New York State Public Scholar”. Wharton Studio Museum is thrilled that Ms. Lupack has joined its Advisory Board.

Suggestions for Further Reading

● Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in Films

● Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser, Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African-American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era

● Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence, Writing Himself Into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films and His Audiences

● Gerald R. Butters, Jr., Black Manhood on the Silent Screen

● Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film

● Jane Gaines, Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era

● Daniel Leab, From Sambo to Superspade: The Black Experience in Motion Pictures

● Barbara Tepa Lupack, Richard E. Norman and Race Filmmaking

● Barbara Tepa Lupack, Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema: From Micheaux to Morrison

● Jim Pines, Blacks in Films: A Survey of Racial Themes and Images in the American Film

● Mark A. Reid, Redefining Black Film

● Jacqueline Stewart, Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Modern Modernity

●Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White, From Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson

#whiteout#sidney poitier#hattie mcdaniel#blackartmatters#BlackLivesMatter#OscarsSoWhite#film#filmhistory

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“What’s that, Pearl?”

“Why, it says here that my fair visage will be projected under the stars on a large screen at Taughannock Park! Can you imagine...How divine!”

“I’ll say! Wharton Studio Museum sure has this summer’s best entertainment in the bag.”

Pearl’s got it right! Outdoor screenings are all the rage these days with films projected on to facades of city buildings, on to rooftop screens, on to a white bed sheet in someone’s garden and, in the case of Wharton Studio Museum (WSM), on to a giant inflatable screen in a beautiful lakefront park.

Join WSM next Saturday night, August 29th at 8:15pm at Taughannock Falls State Park for its 5th Annual Silent Movie Under the Stars screening of two Charlie Chaplin short films from Essanay Studios – founded in Chicago in 1906 by George Spoor and Gilbert Anderson – S & A -- from which we get Ess-an-ay. Essany’s Chaplin comedies His New Job ( the first film Chaplin made for Essanay after he left Keystone Studios) and The Champion – are followed by The Vanishing Man, an episode from the Wharton Studio produced serial The Romance of Elaine. All three films will be accompanied by the Cloud Chamber Orchestra which has composed and performed an original score for each of the past four years! What a treat!

Silent Movie Under the Stars is an ongoing collaboration with the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Wilmington Trust is the Presenting Sponsor for the third year in a row! And WSM thanks Wilmington Trust and all the sponsors who are making this evening possible.

WSM selected the Chaplin shorts, not only because of their obvious charm and appeal and the fact they star one of the greatest actors of all time, but because of a connection between Essanay and the Whartons. Essanay is the same studio that sent filmmaker Theodore Wharton on assignment to Ithaca in 1912. So we have Essanay to thank for the fact that Ted Wharton became quite enamored of Ithaca when he visited as he saw infinite potential in its natural beauty and mix of the rustic and urban. Also, there is some thinking that Chaplin may have visited Ithaca in 1916…

The screening on August 29th will also be a night of anniversaries: not only is it the 5th anniversary of Wharton Studio Museum’s Silent Movie Under the Stars, but, more significantly, it is the 100th anniversary of all three films, which were released in 1915, a century ago!

This lucky writer can attest to the fact that last year’s event offered balmy night air of Taughannock Park laced with laughter and applause! The event and was so appealing and inspiring that the aforementioned writer decided she had to get involved with Wharton Studio Museum. It’s been a wonderful year of getting to know Ithaca’s silent movie history and being involved with WSM on a number of projects.

The rain date is Sunday, August 30th but it is NOT going to rain on the 29th! For details, please visit the WSM’s Silent Movie Under the Stars event page on facebook or our website. But all you have to know is that on Saturday the 29th of August, you need to bring yourself, $5 for parking, lawn chairs and blankets and a picnic to Taughannock Park to enjoy the park before the movies begin at 8:15pm. WSM will have a table where you can acquire Wharton Studio Museum information, purchase a cool, black WSM t-shirt, and meet WSM Board Members and me! After that, all that is required of you is to sit back and enjoy yourself as the night sky moves in and the movies and music begin!

Join us to make noise about silent film!

Aurora Ricardo August 2015

0 notes

Photo

Creighton Hale, Pearl White, and Lionel Barrymore outside the Wharton studio in 1915.

0 notes

Text

Visual Music

An Optical Poem, a whimsical short film produced by Oskar Fischinger in 1938, was, like many of his films, created to accompany specific musical pieces. For this MGM short, he chose Franz Liszt's enchanting “Hungarian Rhapsody, No. 2.” The object animation used in this film is in perfect sync with Liszt's orchestration, making it a playful, colorful featurette.

http://youtu.be/they7m6YePo

Fischinger is the grandfather of visual music. Although Walt Disney claimed Fantasia (1940) was the first animated film set to classical music, that's technically incorrect. If you include abstract animation, then Fischinger definitely had them beat. It's interesting to consider these films in relation to silent film.

Silent films guide the chain of emotional reactions of the viewer as a result of the narrative, visual gestures, and facial expressions. Films like Fischinger’s, release the viewer from that obligation, allowing them space to think about how the music actually makes them feel or what it makes them think. Each time you view a Fischinger film, or other abstract films, such as those of Len Lye, you will have a different experience. You may go deep, or stay on the surface; you may permit yourself to think or simply to feel.

In its early days, musical accompaniment to silent film was an integral part of the film-watching experience. A piano player or organist accompanied the films and audiences were sated by this simple effect. Hard to believe that not a word was uttered. Music was often a mixture of popular tunes and known classics and it certainly served – and still serves – to heighten the emotion of the film. But Fischinger’s work was different in that his visuals gave new life to preexisting music, and considered the pairing to be a matter of artistic integrity.

More recently the tables have turned and musicians and groups such as Alloy Orchestra (regulars at Hamilton College) or the Cloud Chamber Orchestra (who have performed the past four summers at the Wharton Studio Museum's Silent Movie Under the Stars screenings at Taughannock Falls State Park) compose music that gives new life to many beloved silent films.

Aurora Ricardo Contributing Writer and Researcher Ithaca, NY

Fischinger Links: http://www.centerforvisualmusic.org/Fischinger/OFBibliography.htm http://www.centerforvisualmusic.org/Fischinger/

0 notes