A space for all lesbian, bisexual, and other women-loving women of color. (Read the rules before following.)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

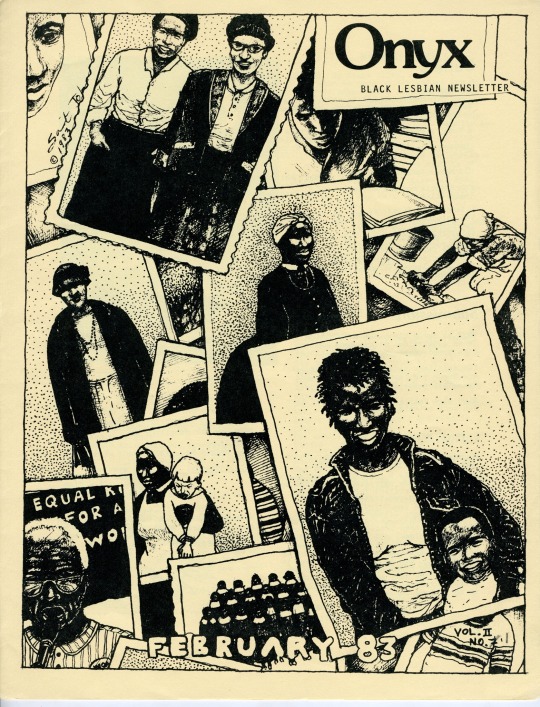

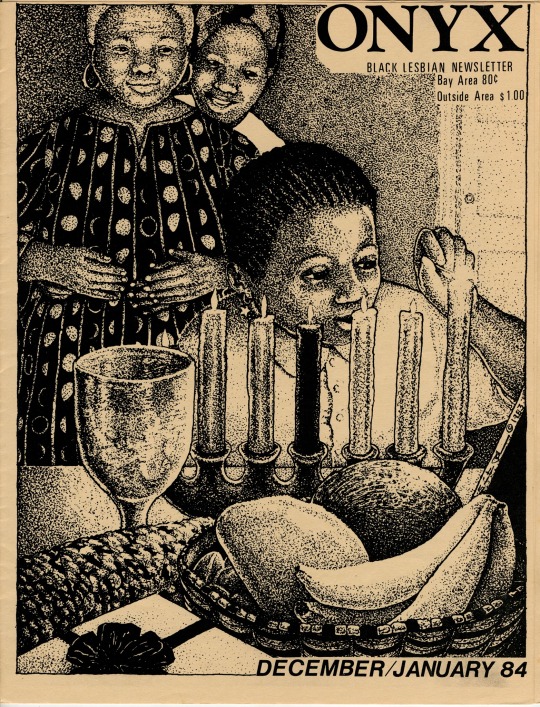

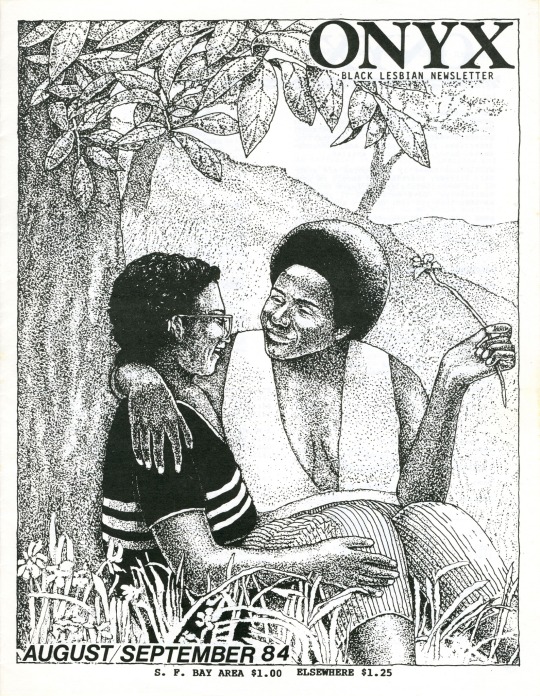

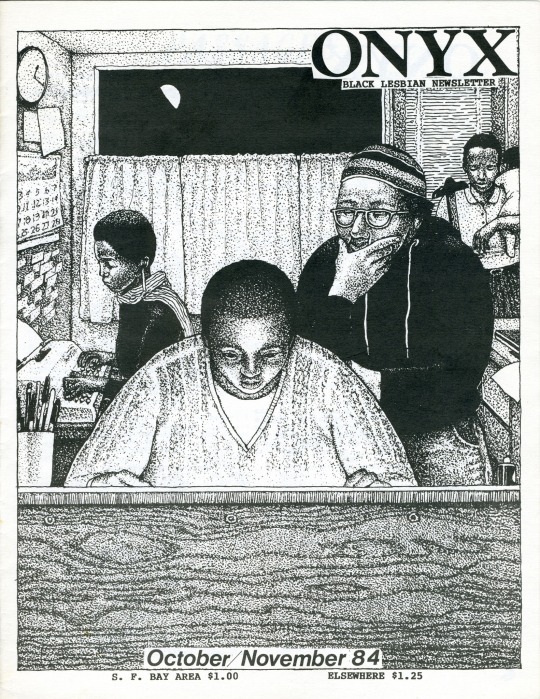

ONYX: Black Lesbian Newsletter was a bimonthly magazine focusing on Black lesbian life, published in the Bay Area from 1982 - 1984. All issues are available to read here.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Each one of us had been starved for love for so long that we wanted to believe that love, once found, was all-powerful. We wanted to believe that it could give word to my inchoate pain and rages; that it could enable Muriel to face the world and get a job; that it could free our writings, cure racism, end homophobia and adolescent acne. We were like starving women who come to believe that food will cure all present pains, as well as heal all the deficiency sores of long standing.”

— Audre Lorde, from Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

335 notes

·

View notes

Text

The North African Queer Film Festival is streaming films about queer experiences in North Africa for 2 more days, till August 20.

The films in this program serve as a window into the historical presence of queer people in the region who have always been here despite marginalization, criminalization and erasure by the current systems of oppression in North Africa inherited from colonization.

The films seem to be free to stream but you can donate of your own volition. From the website:

100% of the festival's proceeds will be distributed among organizations in the region that strive to provide essential aid and services to LGBTQ + people in North Africa with a portion of the proceeds will go to support cultural and artistic initiatives in the region that cater primarily to the local queer community.

980 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Across generations and places, queer romance existed anywhere, anytime. 40 years ago, Myeongdong. If the Pagoda Theatre area in Jong-Ro is the place for a gay community, cafes and restaurants in Myengdong in the 70s were the place for a lesbian community. “Cafe Chanel”, which was a woman-only cafe in Myeongdong in the 70s, was the meet-up place, the community, and the sanctuary for the lesbians of the time. Without the internet, the importance of a safe place where they could have a community was even bigger than now. We are sharing the yet-discovered narrative of the Korean queer community’s history with the theme of “Space” 🌈

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the morning of February 16, 2017, a group of queer and trans activists convened a press conference to denounce Moon’s position on homosexuality and comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation. They then rushed over to a public forum where Moon was to make an appearance. As the frontrunner in the presidential race, Moon was to announce his “blueprint for gender equality policy” at this forum. After waiting for Moon to finish the main part of his speech, during which he declared himself a “feminist president,” the protesters disrupted the event. They suddenly stood up, each holding up A-4 size protest messages that read, “Human rights are a matter of life for sexual minorities” and “Sexual minority rights are not up for negotiation.” They urged Moon to explain – and reverse – his position on human rights for sexual minorities.

This moment was captured in numerous photographs and on video. In a video recording edited and distributed by an independent online media project called Dot Face (.Face), one sees at the center Gwak I-gyeong [Kwak Ekyeong] and several other queer and trans activists, human rights attorneys, and disability activists disrupting the forum. In a scene that has now become an indelible moment in queer political history in South Korea, Gwak shouts in a trembling voice: “I am a woman and a lesbian. How is it that you can slice my human rights in half? How is it that my right to equality can be sliced in half? If you are the frontrunner for the presidency, please answer me. Why is it that in this policy of gender equality, you can not include equality for sexual minorities?”

[…] The scene captured on video was widely shared on social media, but the video went viral not only because of the moving image of Gwak I-gyeong trembling with anger or the reason behind this political disruption. What was most remarkable about the protest was the response by Moon and the audience. Moon is heard telling Gwak, when she and others continued to press for his response, “[l]ater, I will give you a chance to speak later.” Then, a few voices from the audience can be heard repeating Moon’s words – “Later!” (najung-e). This catches on and before long, the audience chants in unison, “Later! Later! Later!”

It is a scene of a crowd silencing the voice of one, almost cheery chants that contrast the urgency of the protesters. Gwak and other protesters are seen in the video looking aghast at their surroundings, their voices soon drowned out by the collective chants of an auditorium full of women, many of them feminists and leaders of women’s organizations. After all, this was a gathering of leaders of women’s groups, and Moon had just declared himself as a feminist ally. “Later” was the message carried through in the menacing chants of this dominant majority against sexual minorities’ rights.

The tension between now and later soon became a key recurring theme in sexual minority politics. What emerged from this tension was a renewed emphasis on the present and a refusal to accept postponement of social change and rights protections. On the heels of the Candlelight Protests, sexual minority activists articulated with urgency their repudiation of a future promised at the expense of the present. It was no surprise that the annual Korea Queer Culture Festival that year in 2017 adopted as its slogan, “Right now! Not later!” Several other political campaigns followed this emphasis on the urgency of the now – labor rights now, anti-discrimination laws now, minimum wage now. While many celebrated the successful end of the Candlelight Protests, sexual minority activists experienced the political moment as a somber and disheartening reminder of the ongoing political challenges to advancing and developing their rights. They had anticipated the possibility that political concessions – especially during elections – would be made at the expense of minorities whose rights were considered dispensable or at least deferrable. Many left-progressives had already predicted that Moon would shift to the right to court centrist and conservative voters. Whatever euphoria of collective action and hopes for radical social change might have been in the air for the millions of participants throughout the Candlelight Protests, human rights for sexual minorities appeared to be indefinitely excluded from the imagined future of collective action for social change, relegated to the territory of “later.”

“The Politics of Postponement and Sexual Minority Rights in South Korea” by Ju Hui Judy Han in Rights Claiming in South Korea

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984-1992 (Dagmar Schultz, 2012)

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Within the Japanese sociocultural context, female homosocial bonding was first ‘recognized’ and became a topic for public discussion at the beginning of the modernization period. After the national isolation policy was withdrawn in 1857, the advent of modernist consciousness produced new and different perspectives on issues surrounding female subjectivity; among these, what is called S (pronounced esu, standing for sister) culture, a direct influence on contemporary yuri manga, was established. Jennifer Robertson, a scholar of female participation in performing arts, asserts that the advent of the Takarazuka review in 1914 provided a solid foundation upon which S culture could develop (1998: 246). In this all-female form of performing art, women play all of the male roles, and these female otokoyaku (male-role performers) possess a bisexual attractiveness (in Helen Cixous’ sense) in relation to primarily female audiences. Imada Erika’s study of shōjo culture in modern Japan points out that the term S is mentioned as early as 1926 in a section of Shōjo gahō magazine (a magazine for girls) titled 'Joshi gakusei kakushi kotoba jiten’ (Dictionary of Shōjos’ Secret Terms, 2007: 190). Kawamura Kunimitsu concludes that S culture began under conditions of oppression, as the principal modernist ideal in relation to women’s social status was ryōsai kenbo (good wife and wise mother). This ideal compels women to fulfil the functions of (heterosexual) mother and wife in the interests of national development, as epitomized by the term fukoku kyōhei (rich country strong army — meaning that raising strong soldiers contributes to the development of the nation) (Kawamura 2003: 63). Several cases of double suicide among girls believed to be involved in S relationships also reflect the general societal persecution of S girls which occurred at this time. According to Hiruma Yukiko (2003), in terms of Japanese gender history, the 'discovery’ of female homosexuality may be dated to the sensational double suicide of two female students in 1911.

“The Sexual and Textual Politics of Japanese Lesbian Comics: Reading Romantic and Erotic Yuri Narratives” by Kazumi Nagaike

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

The genesis of pure yuri manga in the field of Japanese popular culture came in 2003, when a Japanese publishing company, Magazine and Magazine, started publishing a yuri manga magazine, Yurishimai (Yuri Sisters), directed exclusively at female readers. Yurishimai ceased publication in 2005, due to the publisher’s decision to follow a new marketing strategy. Right after the discontinuation of Yurishimai, another Japanese publishing company, Ichijinsha, began publishing Yurihime, having recruited the artists who used to publish in Yurishimai for this new yuri magazine. Yurihime thus resumed publication of a number of serialized works which had originated in Yurishimai.

[…] One of the origins of yuri writing can be traced back to a female Japanese writer, Yoshiya Nobuko (1896-1973), who actively produced lesbian narratives concerning shōjo (girls) during the early 20th century. One of her most popular novels, Hana monogatari (Flower Tales), was serialized from 1916-24 in a magazine titled Shōjo gahō, which was mainly directed at young women. This work is set in a girls’ dormitory and depicts, in very romanticized language, the emotional (but also more overtly sexual) bonding between girls. The development of a particular shōjo bunka (girls’ culture) in Japan has been strongly influenced by Yoshiya Nobuko’s writings (Honda 1982: 172, Dollase 2003: 724). Another influential novel, Yaneura no nishojo (Two Virgins in the Attic) demonstrates the semi-autobiographical nature of much of Yoshiya’s writing. One of this novel’s primary themes involves her confession of her lesbian desires and relationships (Dollase 2001).

The genealogy of yuri manga can also be analyzed in relation to the genre of shōjo (girls’) manga, which became popular during the 1970s and is predominantly characterized by a juvenile boy-meets-girl narrative motif. Many shōjo manga artists have also developed the theme of (sexually) romantic relationships between girls. Explicit sexual scenes are usually excluded from stereotypical shōjo manga narratives, partly because the majority of readers are believed to be shōjo (girls). Thus, the lesbianism represented in shōjo manga remains fundamentally distanced from women’s corporeal desires for other women; instead, these texts emphasize the spiritual side of female-female (or girl-girl) relationships. Fujimoto Yukari (1998), a manga scholar, comments that lesbian narratives in shōjo manga first appear in the early 70s; one example is Yamagishi Ryōko’s Shiroi heya no futari (Two in the White Room, 1971). According to Fujimoto, many early lesbian narratives in shōjo manga have rather tragic conclusions, internalizing the disillusionment which was felt at the failure of previous attempts to challenge heterosexual conventions. The genuinely revolutionary wave of lesbian-themed works in shōjo manga occurred during the 1990s, when the number of works dealing with female characters’ lesbian-oriented self-revelation and with the idea of playing with gender roles started to increase.

“The Sexual and Textual Politics of Japanese Lesbian Comics: Reading Romantic and Erotic Yuri Narratives” by Kazumi Nagaike

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

This pictorial of a korean lgbt couple is so gorgeous. And the hanboks are so pretty too😭

Source 📌belowmyrainbow / photos and description

13K notes

·

View notes

Video

tumblr

wedding chinese hanfu for lesbian couples by 临溪摄影

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Poem for Haruko” by June Jordan

I never thought I’d keep a record of my pain or happiness like candles lighting the entire soft lace of the air around the full length of your hair/a shower organized by God in brown and auburn undulations luminous like particles of flame But now I do retrieve an afternoon of apricots and water interspersed with cigarettes and sand and rocks we walked across: How easily you held my hand beside the low tide of the world Now I do relive an evening of retreat a bridge I left behind where all the solid heat of lust and tender trembling lay as cruel and as kind as passion spins its infinite tergiversations in between the bitter and the sweet Alone and longing for you now I do

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

What would a queer version of this diasporic history look like? What would it mean to discuss sexuality as an integral and defining part of this story about governments, wars, capitalism, and migration? How would one go about investigating a queer Korea? And why would this be important? Reclaiming a history in a diasporic homeland is even more complicated for those of us who are queer. Being multiply displaced makes the process more difficult to research and more fraught with needs and desires. How do people construct a homeland that not only includes but might possibly also even embrace their queer selves? Cherrie Moraga describes such a space for queer Chicanos:

“Queer Aztlan” had been forming in my mind for over three years and began to take concrete shape a year ago in a conversation with poet Ricardo Bracho. We discussed the limitations of “Queer Nation,” whose leather-jacketed, shaved-headed white radicals and accompanying anglo-centricity were an “alien-nation” to most lesbians and gay men of color. We also spoke of Chicano Nationalism, which never accepted openly gay men and lesbians among its ranks. Ricardo half jokingly concluded, “What we need, Cherrie, is a “Queer Aztlan.” Of course. A Chicano homeland that could embrace all its people, including its jotería . (147)

[…] I think our efforts to reclaim queerness in the homeland need to avoid some common dangers. First, many claim to pursue this effort in order to reconcile "two worlds”: the diasporic and the queer. The separation of queer practices and cultural identities is easily labeled as a cultural/ ethnic/racial divide, although even for those who are white, being queer usually means leaving home. Rakesh Ratti’s introduction to A Lotus of Another Color states, “We stand with one foot in the South Asian society, the other in the gay and lesbian world. It is natural then that we should support one another in sorting out these conflicts” (14). The language of “two worlds” homogenizes each side, as if there were not multiple and multiply divided South Asian societies and gay and lesbian (and bisexual and transgender and queer) communities. And, as the quote illustrates, this “binarization” usually sets up the worlds as naturally opposing categories, which must inevitably conflict.

The dichotomy easily lends itself to racist and imperialist uses, specifically the idea that Asian, Third World, or people-of-color cultures are “sadly” more homophobic than are white Western societies. Not surprisingly, this is related to the idea that these cultures are inherently more patriarchal and sexist. This view of the world casts Other cultures as fixed, monolithic, unchanging, backward, and unreasonable, in contrast to an enlightened, modern, liberal humanist Western civilization with an infinite capacity for rational tolerance. It also assumes that homophobia is a single quantifiable phenomenon, with a range of “more” and “less.” It is clear to me that these are absurd assumptions, perpetuated by a self-serving white Western pretense to superiority. Carmen Vazquez says, “Challenging homophobia in the Latino community is no more and no less a challenge than it is to challenge it in any other ethnic community” (54). People in Asia, the Third World, or racial minority communities are not more homophobic, they are differently homophobic, in ways conditioned not only by beliefs, values, and circumstances but also by histories of Western imperialism and U.S. racism.

Towards a Queer Korean American Diasporic History, 1998 by JeeYeun Lee

18 notes

·

View notes

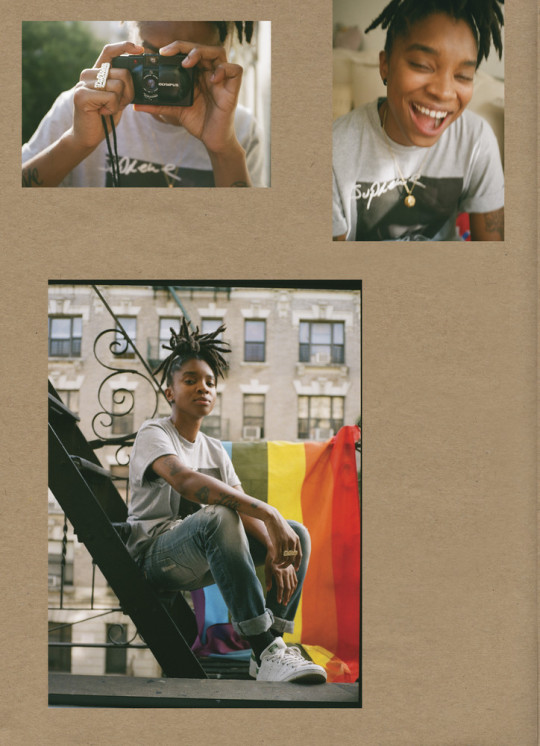

Photo

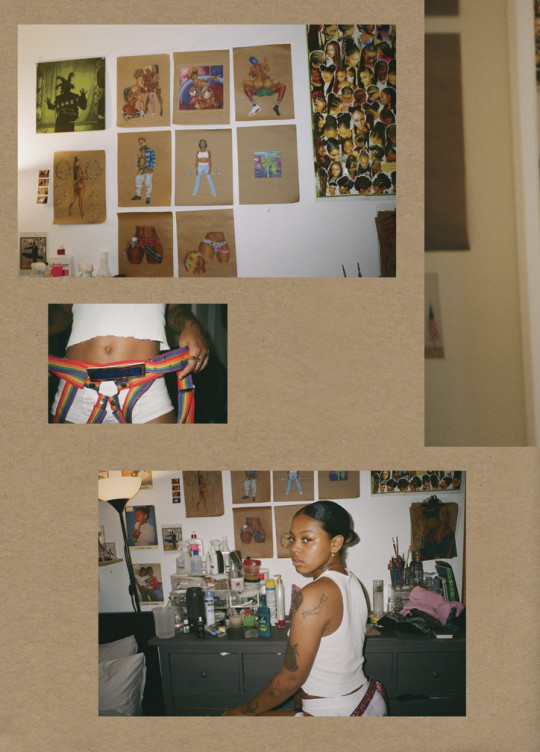

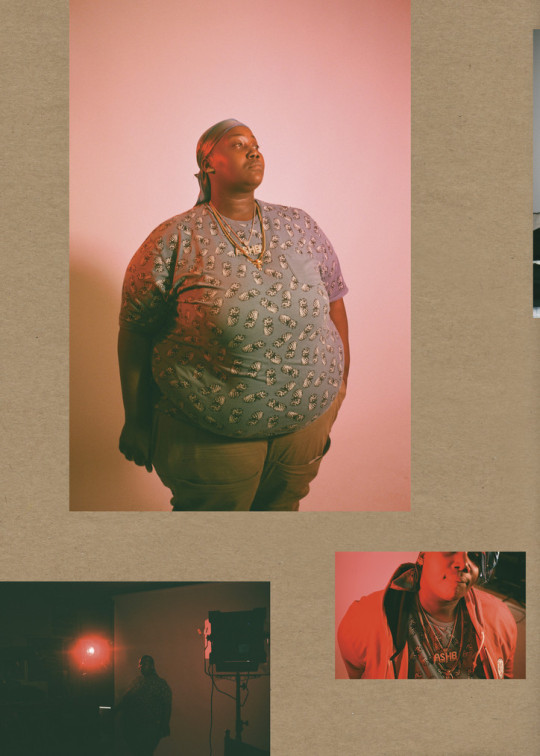

Aya [Brown]’s scenic depictions beam with ghetto nuance and seduction. Her work is intersectional—she takes artifacts from Black and queer culture and fuses them, putting a face to the often unseen. Aya’s art suggests that lowbrow is the latest highbrow response to boring straight white male culture. Her style draws upon figures both living and deceased, from Missy Elliott to Toni Morrison. It’s nasty foreplay and sensual love. It’s Black Lesbian pride. “It is one of my biggest missions in life to document my own history, BLACK LESBIAN history,” she tells office. “This is not a game of telephone. I don’t want a little Black girl to learn about us, from anyone but us.”

Harder Than Ever Before

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Saving Face (2004) dir. Alice Wu vs. The Half of It (2020) dir. Alice Wu

10K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“one day, i was reading a book about lesbians and my son came into the room and asked me to read from the book to him. so, i began to read to him, and the word lesbian came up somewhere in the few paragraphs that i read, and he said, “what’s a lesbian?” and i told him, “a woman that loves women and makes a life with a woman as a companion.” so he said, “oh, so that’s what you do.” i said, “yeah.” he said, “so that means you’re a lesbian.” and i said, “yeah.” and he said, “but mommy, i thought you were a virgo” from the documentary film choosing children: launching the lesbian baby boom, 1985

25K notes

·

View notes

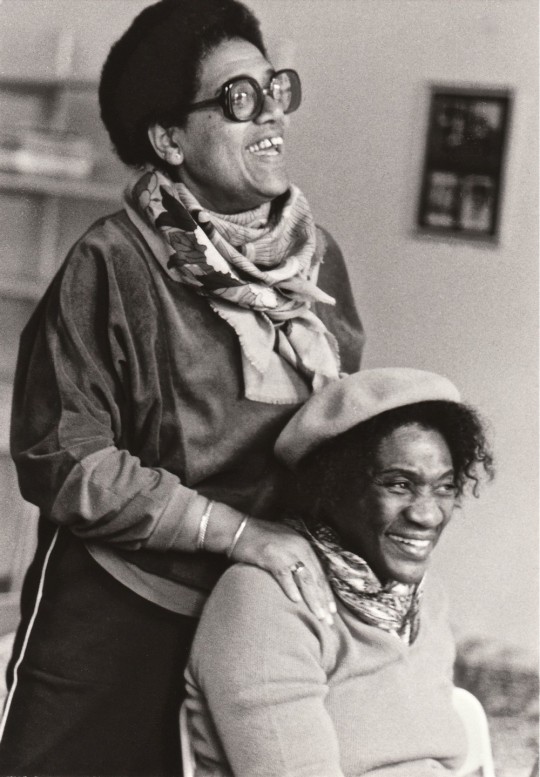

Photo

Three photos of Black lesbian writer and activist Audre Lorde and her partner and fellow activist Gloria Joseph. Audre and Gloria lived together in Gloria’s home of St Croix in the Carribean until Audre’s death in 1992. The last thing Audre wrote was a note reading “Gloria, I love you.”

Learn more about Audre Lorde with our podcast

[images: Audre (left) and Gloria (right) wearing leis; Audre (left) standing behind Gloria (right), both laughing; Audre (right) and Gloria (left) seated, leaning on each other and laughing with their eyes closed]

5K notes

·

View notes