Text

Hiragana Page

Hello everyone! Welcome to my page for the basics on Hiragana!

Hiragana are the gateway into Japanese. It all starts here. The posts below will help you get familiar with these basic Japanese characters. Enjoy!

① The Basic 46 ② Five More Sound Groups (Dakuten & Han-dakuten) ③ Vowel Sound Groups (VSGs) ④ The Last Three Sound Groups

⑤ Long Vowel Sounds ⑥ Small つ

⑦ Pronouncing ん ⑧ Furigana & Okurigana

For matching practice activities, click here.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basic 46

This may be your very first page on your road to learning Hiragana! Either way, welcome!

There are 46 basic Hiragana characters. 6 of them are represented by a single English letter, while 3 of them are represented by three letters. The remaining 37 are all represented by two characters.

【Romaji】

First let’s talk about Romaji. You may have heard that Japanese has 3 sets of characters to express the language – Hiragana, Katakana, and Kanji. While that is true, there is a fourth set of characters and that is Romaji!

If you see the word “sake” you automatically read it as a word that rhymes with “take” and means “for the benefit of someone or something”. However, this is the English reading of the word. If you look at that word as Romaji, it is pronounced as “sah-keh” and it means Japanese alcohol.

Romaji is not English. It is an attempt at writing Japanese words with the English alphabet. There are sounds in each language that are not in the other, so relying on Romaji for too long is not a good idea. It is really only useful when you are beginning to learn Hiragana (and maybe 1 or 2 instances after that).

【Order】

Just like how we have something called “alphabetical order”, there is also an order to Hiragana (and katakana as well). To remember the order, there are several mnemonics that people use but the one I’ve always used is:

Kana Signs, Think Now How Many You Really Want

And with that, now let’s look at those 46 characters!

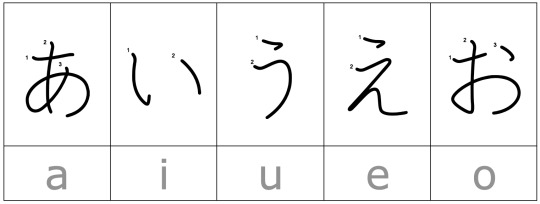

【The Vowel Group (あいうえお)】

These 5 characters are the vowels of Japanese. While English (depending on where you are from) can have anywhere from 24 to 27 different vowel sounds, the GOOD NEWS is that Japanese only has these 5!

【The K Sound Group (かきくけこ)】

At this point we need to be aware of a big difference between Japanese and English. If I asked you to break down the sounds of the word “kid”, you would tell me the 3 individual sounds for each letter. But in Japanese, the ”k” and “i” sounds MUST go together. The majority of Japanese hiragana characters are made up of a consonant-vowel pair.

This is why almost all of our remaining hiragana characters need either two or three English letters. The K Sound Group 2 is simply the consonant “k” sound and each of the 5 vowel sounds.

【The S Sound Group (さしすせそ)】

Our next group is made up of the consonant “s” sound and each of the 5 vowel sounds. However, in this group we have our first irregular character!

According to the pattern so far, you would think that the し character would be pronounced “si”, as in the Spanish word for “yes”. In actuality, it’s pronounced “shi” like the English word “she”. This is something to take a mental note of.

【The T Sound Group (たちつてと)】

The next group is mostly made up of consonant “t” sound and each of the 5 vowel sounds. This time, we have two irregular characters! Instead of sounding like the English word “tea”, the character ち sounds like the second syllable of the English word “catchy”.

Unfortunately, the character つ doesn’t have any equivalent sound in English. Instead of sounding like the Spanish word for you (tu), the closest we can get is trying to make the “t” sound while saying the name “Sue”! This character took me a bit of practice and a lot of time to master.

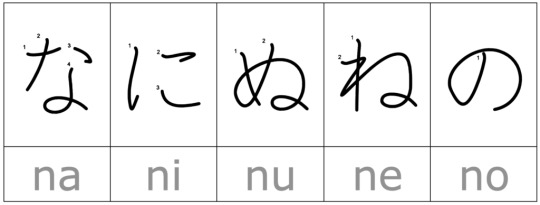

【The N Sound Group (なにぬねの)】

Good news: The next group doesn’t have any irregular characters, so it is pretty straightforward!

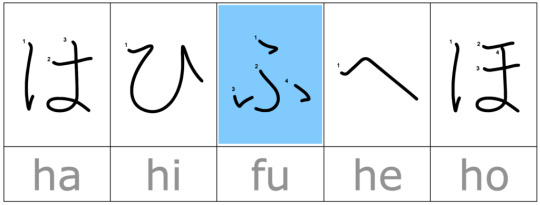

【The H Sound Group (はひふへほ)】

The H Sound Group has one irregular character. You might be tempted to think that ふ is pronounced as “hu”. If you look at the English representation, you might think that it’s pronounced as the first part of the word “fool”. In actuality it is pronounced somewhere in between! Just like つ, this character took me some time to get right.

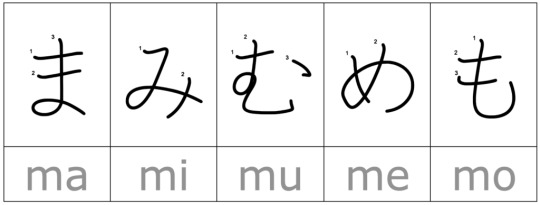

【The M Sound Group (まみむめも)】

This group is also pretty straightforward. No irregular pronunciations here!

【The Y Sound Group (やゆよ)】

You’ll notice that this group only has three characters. There used to be characters for the sounds “yi” and “ye” but they dropped out of modern use.

Also, these 3 characters are very important for making another set of sounds. We’ll get into that in a later post.

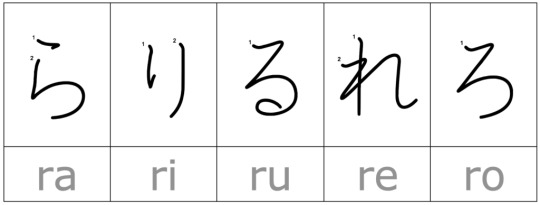

【The R Sound Group (らりるれろ)】

This group appears to be simply the 5 vowel sounds added to the consonant “r” sound, however it isn’t that simple.

As you may or may not know, Japanese people have a very hard time pronouncing and differentiating between the English “r” and “l” sound. The reason is that they don’t have those sounds in Japanese. Unfortunately that also means that these 5 characters are not easy for native English speakers to pronounce. Each character’s pronunciation is actually somewhere between an “r” and an “l” sound. These characters took me the longest time to master (especially in long words!)

【The W Sound Group (わを)】

This group only has 2 characters. The thing of note here is that を sounds almost identical to the character お. を is only used as a particle, so it will never appear in the middle of a word. Also, when it’s used as a particle, you might be able to hear a slight pause after it. These kinds of tricks make it easy to figure out when you are hearing を and when you are hearing お.

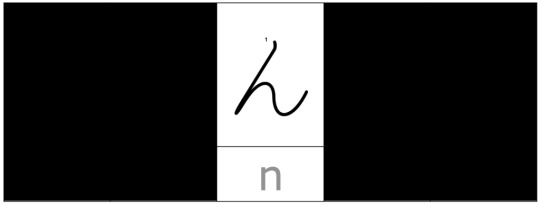

【ん】

The last basic character is ん. This is actually the only character that can be represented by a single consonant. It is mostly easy to tell when you are hearing this character, but there will be times when its pronunciation changes. More on that later.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! Some people say that you can learn all 46 characters in 2 days, others say it should only take a week. It took me longer than that and so I say, take your time! There is no race to learn them so go at your own pace. Make sure that you have a good time while you practice; you’ll be more likely to remember the characters that way. Hiragana are important for learning Kanji down the line so it’s best to do it right the first time. Good luck!

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's learn name of country in Japanese!

ドイツはビールが有名です Doitsu wa bīru ga yūmei desu. Germany is famous for beer

オーストラリアはカンガルーがいます Ōsutoraria wa kangarū ga imasu There are kangaroos in Australia

日本は寿司が美味しいです Nihon wa sushi ga oishii desu Sushi is delicious in Japan

イタリアはピザが有名です Itaria wa piza ga yūmei desu Italy is famous for pizza

インドネシアにはたくさんの島があります Indoneshia ni wa takusan no shima ga arimasu Indonesia has many islands

イは料理が辛いです Tai wa ryōri ga karai desu Thai food is spicy

Learn easy Japanese with CrunchyNihongo.com

Happy learning! ( ˶ˆᗜˆ˵ )

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - している [Part 2]

Hey everyone, welcome to Part 2 of talking about している. This N5 grammar point is very basic but also very important. Let’s get into it shall we!

But first, here is your vocabulary:

【English Helping Verbs】

As I mentioned in Part 1, the “して“ in している can stand for any verb in て form. Sometimes it is actually する, but most times it will be some other verb.

Ok great, but what is the いる part?? Take a look at the following English sentences:

① Traffic accidents often occur here.

② I am eating.

③ The window is open.

Two of these sentences have both a helping verb and a main verb. In #1, there is only a main verb, which is “occur”. In #2 the main verb is “eating” and the helping verb is “am”. In #3 the main verb is “open” and the helping verb is “is”. Notice that one of the main verbs has the -ing suffix while the other two don’t. Make a mental note of this for later. 😉

【The いる in している】

Japanese also has helping verbs. Allow me to introduce you to one of the most common ones: いる!

The いる helping verb* adds nuance to the main verb. But here’s the thing - there are different versions of いる!In the している Part 1 article, you actually saw what I call the いる of Repetition. This いる does not translate to the -ing form of our verbs in English. If you see よく起きている for example, you should think “often occur(s)”. This is similar to example #1 above.

Examples #2 and 3 are not actions of repetition. For them, we need the other いる, which I call the いる of State or Condition. This いる sometimes makes us use that -ing suffix in our English translations. So if you just see 食べている, by default it would mean “started eating and then stayed in that state for some period of time”. Instead of all that, in English we would simply say “is eating”. This is similar to example #2 above.

開く is a different type of verb than 食べる**. Because of this, the いる of State or Condition does not lead to us using the -ing form. In this case, something is open and stays in that state for some period of time. We don’t say “is opening”. Instead we just say “is open”. For verbs like 開く, their English translations won’t use that -ing form. Instead they will be like example #3 above.

The key to the している grammar point is understanding what kind of main verb you have, and then which helping verb いる you are reading/hearing!

【いる of State or Condition】

Here are some examples where the helping verb いる expresses a state or condition.

This is how you say example #3 in Japanese.

= Tom is currently in the Philippines.

Interestingly, you could also say the following:

⑥ トムはフィリピンに来ています。***

⑦ トムはフィリピンにいます。

#5, 6 and 7 all say that Tom is in the Philippines but the nuance is different in each of them!

#5 says that Tom went to the Philippines and stayed there. This means that the speaker is NOT in the Philippines. On the other hand, #6 says that Tom came to the Philippines and then stayed there, meaning that the speaker is also there. #7 simply says that Tom is in the Philippines. We don’t have any information about where the speaker is located.

= Mizuki is wearing a white skirt and hat.

#8 has several things that I want to point out: First is that the て form of a verb can mark the end of a comment. Example 8 has two comments of equal value. This is one version of a Japanese compound sentence.

The second thing is that the ending helping verb can actually apply to TWO DIFFERENT main verbs! Native speakers hear #8 and understand the verbs to be both はいています as well as かぶっています.

The last thing is that verbs connected to clothes are very interesting. When you attach the helping verb いる, they can sometimes express the state of wearing something. However, in some contexts they can instead express the action of putting something on. For the N5 level luckily you won’t have to distinguish between wearing and putting on clothing so no worries. It is good to keep this tidbit in the back of your mind for the future though.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it. Now you know that the している grammar point can express several situations. You could have:

・Repetition - there will be a word/phrase that indicates that the action happens repeatedly. The English translation won’t use the -ing form of a verb

・State or a Condition - there MAY or may not be a word/phrase indicating repetition. The main thing to focus on is whether the verb is an action verb or not. This will help you decide if you need -ing or not.

As always, keep your eyes and ears open for different kinds of examples and try to notice patterns. You can do it!

Rice & Peace,

– AL

👋🏾

*I purposely say “the helping verb いる“because there is also the regular いる verb. It’s the same with the “be”, “do” and “have” verbs in English. “Am” in “I am a teacher” plays a different role than the one in “I am eating.”

** 食べる is a transitive verb while 開く is an intransitive verb. Usually transitive verbs will translate to -ing and intransitive verbs won’t. Of course there are exceptions so keep an open mind.

*** When choosing between 来ている、行っている、and いる think about where the speaker is located as well as if you want to stress the movement of the subject.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - している [Part 1]

している is a grammar point that is very very important in Japanese. The “して” part represents a verb in the て form. The “いる” part is the verb いる, which will change to different forms (for example います、る or ます).

している actually appears in several levels of the JLPTs - from N5 all the way to N2! As for the N5 level, there are 2 main ways that you will see it used. In this post let’s look at one of them!

First, here is your vocabulary.

【Repeated Actions】

First let’s look at how している is used with repeated actions. These actions are mostly physical.

= I climb Mt. Fuji every year.

Notice the two highlighted words, 毎年 and 登って. If 毎年 weren’t there you would almost always translate 登っています as “am climbing”. However, because 毎年 expresses repetition, it forces us to translate 登っています as “climb”.

= Traffic accidents happen on this street often.

起きる is a verb that can mean “to wake up” or “to occur”. If sentence #2 didn’t have the word よく it would be understandable to translate 起きています as “are occurring”. However because of the よくwe understand that there is repetition and so we go with the “occur” translation instead.

= Well you see, Dad has been going to China for work once a month since last year.

This time the word / phrase that expresses repetition is 毎月1回 meaning “once a month”. This tells us that 行ってる is “goes” instead of “is going”. Also, the い in the helping verb いる can be dropped, making 行ってる a more casual way of saying 行っている. It also works for います so that 行ってます is more casual than saying 行っています。

Finally, take a look at the nuance section. This んです is actually a different JLPT grammar point. The gist is that it’s used when you want to answer a question with extra details that you think the listener/reader wants to know. The ん is a shortened version of the particle の.

【Occupation or Social Position】

している is also used to talk about someone’s occupation or social position.

= Taiki teaches Japanese at a Thai university.

There is no period of repetition stated outright, but we understand that teaching is a job that you do over and over. Thus, you should use 教えています instead of 教えます。

= Aya is a trading company manager.

In this case, the しています simply means “is” or “has the position of”.

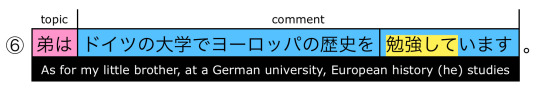

= My little brother studies European history at a German university.

This last example is a good one to remember. Most times, if you say 勉強しています it will mean “currently studying”. However when it comes to being a student, the translation shifts to “studies (for an extended period of time)”. Actions that can be interpreted either way (like studying) will sometimes have time words / phrases like 今 (now) or 2、3時間 (for a few hours). That tells you that it is an action in progress. Other than those kinds of phrases, usually the meaning will be repetitive.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! The first している is associated with repeated actions, occupations, or positions in society or work. It’s fairly easy to figure out if the sentence is talking about an occupation or a position. For repeated actions, the key is to look for words / phrases that express repetition and remember that they cause you to use the している version of your verb. With that, you should be fine!

Rice & Peace,

– AL

👋🏾

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today’s JLPT N4 Word is 体

体がだるいです。 Karada ga darui desu. My body feels sluggish.

運動すると体が元気になります。 Undou suru to karada ga genki ni narimasu. When you exercise, your body feels energized.

彼は体が大きいです。 Kare wa karada ga ookii desu. He has a big body.

寒いときは体を温めましょう。 Samui toki wa karada o atatamemashou. When it’s cold, let’s warm up our bodies.

体にいい食べ物を食べましょう。 Karada ni ii tabemono o tabemashou. Let’s eat food that’s good for the body.

体 - karada - body

運動 - undou - exercise

元気 - genki - energy, health

彼 - kare - he

大きい - ookii - big

寒い - samui - cold (weather)

温める - atatameru - to warm

食べ物 - tabemono - food CrunchyNihongo.com

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kanana is here!

For those who just started learning Japanese hiragana and katakana. This is for you!

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.momologic.kanana

Download with link above

iOS version coming soon!

Features: • Track your learning progress • Fun mnemonics to help you learn easier • Relaxing music to aid you learning • Start a quiz to test your skill • Practice reading with Japanese vocabularies & stories

Download link:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.momologic.kanana

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Counters

When you learn Japanese numbers (一 to 十 plus 百 and 万) you think that you already know how to count in Japanese, right? But this is just the beginning! When you count items, everything from animals to cars and long, cylindrical objects, you have to use different counters.

Two Counters That Will Get You Through Everything

~つ

Not technically a counter, but it can be used to count almost anything. So if you don’t remember the particular counter, use ~つ as a fallback.

~個 (こ)

This counter is almost as versatile as ~つ but it is not for abstract things (ages, number order, etc.)

10 of the Most Common Counters

~本 (ほん)

Counter for long, skinny (usually cylindrical or cylindrical-adjacent) objects.

(一本=いっぽん、三本=さんぼん、六本=ろっぽん、十本=じゅっぽん、百本=ひゃっぽん - special readings)

~枚 (まい)

Counter for flat things (square flat things, round flat things, flat-ish things like art)

~匹 (ひき)

Counter for small animals (smaller than a horse-size animal)

(一匹=いっぴき、三匹=さんびき、六匹=ろっぴき、八匹=はっぴき、十匹=じゅっぴき、百匹=ひゃっぴき - special readings)

~頭 (とう)

Counter for large animals (larger than a horse-size animal)

(一頭=いっとう、八頭=はっとう、十頭=じゅっとう、百頭=ひゃっとう - special readings)

~羽 (わ)

Counter for birds (winged - but not insects) and rabbits (because they have long ears like wings?)

~冊 (さつ)

Counter for books

(一冊=いっさつ、八冊=はっさつ、十冊=じゅっさつ - special readings)

~台 (だい)

Counter for machines, cars, large instruments, platforms

~回 (かい)

Counter for frequency (number of times you do something)

(一回=いっかい、六回=ろっ��い、八回=はっかい、十回=じゅっかい、百回=ひゃっかい - special readings)

~人 (にん)

Counter for people

(一人=ひとり、二人=ふたり - special readings)

~階 (かい)

Counter for floors

(一階=いっかい、六階=ろっかい、八階=はっかい、十階=じゅっかい、百階=ひゃっかい - special readings)

Ready for more counting? Visit the Tofugu counting page for 350 counters.

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

👏you👏won't👏remember👏shit👏if👏you👏try👏to👏learn👏100👏words👏in👏one👏go

323 notes

·

View notes

Text

ways to say "only", "just" in Japanese

When I started learning Japanese, I quickly discovered that “only” translates to だけ (dake). Soon after, I learned about しか (shika) and then ばかり (bakari). This led me to wonder how many ways there are to express the idea of "only" or "just" in the Japanese language. I began exploring the fascinating world of adverbs that convey limitation or exclusivity, each with its own specific nuance.

Here are some of the terms I’ve discovered (which I may continue to expand upon):

だけ (dake): Strongly emphasizes exclusivity, meaning that nothing else is included or considered. Example: 水だけください。 (Please give me only water.)

しか (shika) (used with a negative verb): Often conveys a sense of disappointment or limitation, implying that there’s nothing but the mentioned item, often with a sense of restriction. Example: 私は日本語しか話せません。 (I can only speak Japanese.)

ばかり (bakari): Suggests the dominance or prevalence of something, often with a sense of excess or monotony and a negative nuance. It does not imply strict exclusivity. Example: お菓子ばかり食べている。 (I’m only eating snacks.)

ばかし (bakashi): A casual variant of ばかり, used mostly in spoken language. It conveys a similar meaning but carries a more informal tone. Example: 遊んでばっかしいる。 (He’s only playing.)

のみ (nomi): Used in formal or written contexts, conveying exclusivity. It can sound elegant and refined. Example: 本日のみ有効です。 (Valid only today.)

ばかりか (bakari ka): This expression expands the meaning by introducing additional information, indicating more than just "only." Example: 彼は優しいばかりか、面白いです。 (He is not only kind but also funny.)

だけしか (dake shika) (used with a negative verb): This term combines だけ and しか, emphasizing strong exclusivity when used with negative constructions. Example: これだけしかない。 (There is only this.)

こそ (koso): Indicates that the highlighted item is particularly special or the best choice, often implying that nothing else can compare. Example: 今日こそ勉強する。 (Today, of all days, I will study.)

たった (tatta): Implies that an amount is minimal and often inadequate, highlighting a sense of limitation. Example: たった一人で旅行した。 (I traveled with just one person.)

わずか (wazuka): Emphasizes a minimal quantity or degree, often with a sense of surprise. Example: わずか10分で終わった。 (It only took 10 minutes.)

ほんの (honno): Indicates a small or trivial amount, often used to downplay something. Example: ほんの少しだけ食べた。 (I ate just a little bit.)

に限る (ni kagiru): This expression is used to convey that something is the best or only suitable choice for a situation. Example: 夏はアイスクリームに限る。 (Ice cream is the best for summer.)

だけでなく (dake de naku): Similar to ばかりか , this phrase is used to express that there’s more than just one thing happening. Example: 彼女は賢いだけでなく、優しいです。 (She is not only smart but also kind.)

単に (tan ni): Indicates simplicity; often used to clarify or explain something in a straightforward manner. Example: 単に冗談だよ。 (It’s just a joke.)

あくまで (akumade): Suggests that something is true only to a certain extent or in a specific context. Example: あくまで私の意見です。 (This is just my opinion.)

たかが (takaga): Often carries a dismissive connotation, suggesting that something is not very important. Example: たかが試験一回でどうなるものか。 (It’s just one exam; it won’t change much.)

I love discovering all these subtle differences and nuances, even if it can be frustrating at times. If you know of any more, please share!

#japanese langblr#japanese language#langblr#learning japanese#japanese vocabulary#日本語#nihongo#japanese grammar#japanese#study

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Free PDF Workbooks for Japanese, Spanish, Korean, etc. (30+ languages)

If you’re looking to practice a bit and remember your target language better… here are tons of free worksheets/workbooks for 34 languages (Japanese, Spanish, Korean, French, German, Italian, etc, etc.)

It’s the same type of “fill in the blank” workbook across all of their languages but the magic in actually rewriting things over and over is that the words end up sticking. Plus, there are English sections where you’ll have to force yourself to remember and write the word/phrase in the target language - which is even better for your memory (called active recall - forcing yourself to remember). I’m personally a big fan of this approach and I’d do similar to pass vocab quizzes in my HS & uni language classes.

If you’re interested, give these a go.

Afrikaans— https://www.afrikaanspod101.com/Afrikaans-workbooks

Arabic— https://www.arabicpod101.com/Arabic-workbooks

Bulgarian— https://www.bulgarianpod101.com/Bulgarian-workbooks

Cantonese— https://www.cantoneseclass101.com/Cantonese-workbooks

Chinese— https://www.chineseclass101.com/Chinese-workbooks

Czech— https://www.czechclass101.com/Czech-workbooks

Danish— https://www.danishclass101.com/Danish-workbooks

Dutch— https://www.dutchpod101.com/Dutch-workbooks

English— https://www.englishclass101.com/English-workbooks

Filipino— https://www.filipinopod101.com/Filipino-workbooks

Finnish— https://www.finnishpod101.com/Finnish-workbooks

French— https://www.frenchpod101.com/French-workbooks

German—https://www.germanpod101.com/German-workbooks

Greek— https://www.greekpod101.com/Greek-workbooks

Hebrew— https://www.hebrewpod101.com/Hebrew-workbooks

Hindi— https://www.hindipod101.com/Hindi-workbooks

Hungarian— https://www.hungarianpod101.com/Hungarian-workbooks

Indonesian— https://www.indonesianpod101.com/Indonesian-workbooks

Italian— https://www.italianpod101.com/Italian-workbooks

Japanese— https://www.japanesepod101.com/Japanese-workbooks

Korean— https://www.koreanclass101.com/Korean-workbooks

Norwegian— https://www.norwegianclass101.com/Norwegian-workbooks

Persian— https://www.persianpod101.com/Persian-workbooks

Polish— https://www.polishpod101.com/Polish-workbooks

Portuguese— https://www.portuguesepod101.com/Portuguese-workbooks

Romanian— https://www.romanianpod101.com/Romanian-workbooks

Russian— https://www.russianpod101.com/Russian-workbooks

Spanish— https://www.spanishpod101.com/Spanish-workbooks

Swahili— https://www.swahilipod101.com/Swahili-workbooks

Swedish— https://www.swedishpod101.com/Swedish-workbooks

Thai— https://www.thaipod101.com/Thai-workbooks

Turkish— https://www.turkishclass101.com/Turkish-workbooks

Urdu— https://www.urdupod101.com/Urdu-workbooks

Vietnamese— https://www.vietnamesepod101.com/Vietnamese-workbooks

#learn japanese#japanese grammar#japanese#language#language learning#japanese language#langblr#japanese langblr#nihongo#studying#studyblr

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

ways to say "only", "just" in Japanese

When I started learning Japanese, I quickly discovered that “only” translates to だけ (dake). Soon after, I learned about しか (shika) and then ばかり (bakari). This led me to wonder how many ways there are to express the idea of "only" or "just" in the Japanese language. I began exploring the fascinating world of adverbs that convey limitation or exclusivity, each with its own specific nuance.

Here are some of the terms I’ve discovered (which I may continue to expand upon):

だけ (dake): Strongly emphasizes exclusivity, meaning that nothing else is included or considered. Example: 水だけください。 (Please give me only water.)

しか (shika) (used with a negative verb): Often conveys a sense of disappointment or limitation, implying that there’s nothing but the mentioned item, often with a sense of restriction. Example: 私は日本語しか話せません。 (I can only speak Japanese.)

ばかり (bakari): Suggests the dominance or prevalence of something, often with a sense of excess or monotony and a negative nuance. It does not imply strict exclusivity. Example: お菓子ばかり食べている。 (I’m only eating snacks.)

ばかし (bakashi): A casual variant of ばかり, used mostly in spoken language. It conveys a similar meaning but carries a more informal tone. Example: 遊んでばっかしいる。 (He’s only playing.)

のみ (nomi): Used in formal or written contexts, conveying exclusivity. It can sound elegant and refined. Example: 本日のみ有効です。 (Valid only today.)

ばかりか (bakari ka): This expression expands the meaning by introducing additional information, indicating more than just "only." Example: 彼は優しいばかりか、面白いです。 (He is not only kind but also funny.)

だけしか (dake shika) (used with a negative verb): This term combines だけ and しか, emphasizing strong exclusivity when used with negative constructions. Example: これだけしかない。 (There is only this.)

こそ (koso): Indicates that the highlighted item is particularly special or the best choice, often implying that nothing else can compare. Example: 今日こそ勉強する。 (Today, of all days, I will study.)

たった (tatta): Implies that an amount is minimal and often inadequate, highlighting a sense of limitation. Example: たった一人で旅行した。 (I traveled with just one person.)

わずか (wazuka): Emphasizes a minimal quantity or degree, often with a sense of surprise. Example: わずか10分で終わった。 (It only took 10 minutes.)

ほんの (honno): Indicates a small or trivial amount, often used to downplay something. Example: ほんの少しだけ食べた。 (I ate just a little bit.)

に限る (ni kagiru): This expression is used to convey that something is the best or only suitable choice for a situation. Example: 夏はアイスクリームに限る。 (Ice cream is the best for summer.)

だけでなく (dake de naku): Similar to ばかりか , this phrase is used to express that there’s more than just one thing happening. Example: 彼女は賢いだけでなく、優しいです。 (She is not only smart but also kind.)

単に (tan ni): Indicates simplicity; often used to clarify or explain something in a straightforward manner. Example: 単に冗談だよ。 (It’s just a joke.)

あくまで (akumade): Suggests that something is true only to a certain extent or in a specific context. Example: あくまで私の意見です。 (This is just my opinion.)

たかが (takaga): Often carries a dismissive connotation, suggesting that something is not very important. Example: たかが試験一回でどうなるものか。 (It’s just one exam; it won’t change much.)

I love discovering all these subtle differences and nuances, even if it can be frustrating at times. If you know of any more, please share!

#japanese langblr#japanese language#langblr#learning japanese#nihongo#learn japanese#japanese grammar#japanese#japanese studyblr#studyblr

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

here are a few podcasts I listen to weekly for practice!

Japanese with Teppei and Noriko

short, concise episodes covering various topics! easy to follow along!

Let's Learn Japanese from Small Talk

longer more detailed episodes with very casual Japanese! they explain some of the vocab they use while speaking (especially slang) and have a vocab list at the end that they go over with a link to read along!

Japanese with Kanako

great for shadowing practice with a few listening exercises mixed in. perfect if you are using the genki series!

what are some podcasts you like to listen to? 教えてください!😊

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anybody have, like, a masterpost of free or generally affordable Norwegian resources?

Duolingo is going to be implementing a horrific update that takes away your ability to choose what lessons to review, which new material to learn, and when. It’s going to streamline all learning through an algorithm and will completely nullify the methods I use to learn Norwegian through Duolingo on my own terms. So… I need something new.

I have Memrise, and the first of the Mysteriet om Nils series (second one is a little pricey but I’ll probably get it eventually). But other suggestions would be wonderful 😭

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are the Ryukyuan Languages Endangered?

CW: Mentions of war and violence

All of the native languages of the Ryukyu Islands (Uchinaaguchi, Myaakufutsu, Yanbaru Kutuuba, Shimayumuta, Yaimamuni, and Dunan-Munai) are UNESCO listed endangered languages. This means that the languages are not getting passed down from generation to generation, and are at a high risk of being lost completely without efforts to revitalize them. How did they get to this point?

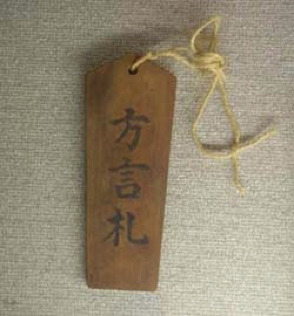

The beginning of the decline of Shimakutuba (Ryukyuan languages) can be traced to 1879, which is when the Ryukyu Kingdom was forcibly annexed, i.e. colonized, by Japan. Upon this act, the Japanese government swiftly enacted assimilationist policies to integrate Ryukyuans into the Japanese nation-state. This involved banning Ryukyuan languages in all public spheres and, educating them only in the Japanese language. To Ryukyuans, Japanese was a foreign language, and if they spoke Shimakutuba in schools, they were punished for doing so. This punishment for speaking Shimakutuba often involved having to wear something called a “Hougen Fuda” (Dialect Tag) around their necks. Calling the Ryukyuan languages “hougen” (dialect) was a psychological tactic, still used even today, to erase and deny the existence of the languages. Even Shimanchu today refer to their native languages as “hougen”, unaware of how harmful and incorrect this term is. I asked several Japanese people and foreigners living in Japan if they knew Okinawa had its own languages- not a single person did.

Going back to the hougen fuda, typically, the unfortunate student who was given this punishment had to keep wearing it until another student was caught speaking Shimakutuba. Sometimes, kids would stomp on another kid’s foot to get them to say “Agaa!” which means “Ow!” in Uchinaaguchi in order to pass off the hougen fuda. As you could imagine, this experience was quite traumatic, and it caused Ryukyuans to associate their native languages with pain and punishment.

In addition, in public buildings (City Hall, etc), Ryukyuans sometimes wouldn’t get served if they spoke in Shimakutuba. They had to speak Japanese to get things done.

These experiences, as bad as they were, don’t even compare to what Ryukyuans went through in the Battle of Okinawa. The Battle of Okinawa was one of the deadliest battles to have taken place during WWII. Nearly one out of every three Ryukyuans died in it. Most of those who died were civilians, or forcibly conscripted into the Japanese army. Japan intentionally built up their troops in Okinawa as a way to delay the US Army from entering “mainland” Japan. Okinawans were dispensable in the eyes of the Japanese state. Some Okinawans were pushed in front of Japanese soldiers to be used as human shields. Okinawans who spoke in Shimakutuba were sometimes suspected to be spies, and then shot.

With all of this trauma from speaking Shimakutuba, it is understandable why many Shimanchu decided not to pass it down to their children. They began developing an inferiority complex towards their own native language, as the Japanese language became more prestigious and economically advantageous. Shimakutuba is generally not taught in schools, and there isn’t much funding available for it. However, this is not to say there isn’t interest in it. In surveys, many Shimanchu youth state that they wish they could speak Shimakutuba in order to understand their grandparents. Without Shimakutuba, this intergenerational connection is getting broken, and young Shimanchu are unable to understand many things in their culture, such as sanshin music, Ryukyuan literature, poetry, historical records, etc. Without the language, we lose an essential component of our culture. The Ryukyuan identity is at stake.

This is why I am learning Uchinaaguchi. This is a language that should have been passed down to me if only my people were allowed to speak it. The more Uchinaaguchi I learn, the more I understand my culture. My grandparents have already passed on, but if I can speak Uchinaaguchi, I could know the sounds that came out of their mouths, and learn their Indigenous way of thinking through the language. I could feel more connected to them, and all of my ancestors.

I am fortunate to have learned why my heritage language is endangered, and to have the ability (time/money) to pursue learning it. However, most young Ryukyuans are unaware of this history, as it isn’t taught much in mainstream Japanese education. I’m not sure exactly how to reverse the cause of the decline in Shimakutuba, but I will do my best to learn it and help other Shimanchu who want to learn it. ちばらやー!

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2012/05/19/national/okinawans-push-to-preserve-unique-language/

https://apjjf.org/-Patrick-Heinrich/3138/article.html

Anderson, M., & Heinrich, P. (Eds.). (2014). Language crisis in the Ryukyus. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

1K notes

·

View notes