#language

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"English isn't my-"

Hush now my friend, and let me read the absolute beauty of a fic that you have bestowed this world and humiliated the first English speakers with

#x reader#fanfic#bakugou x reader#bucky x reader#dabi x reader#dean winchester x reader#draco x reader#hawks x reader#peter parker x reader#steve rogers x reader#tony stark x reader#sherlock x reader#x men#sebastian stan x reader#avengers x reader#deadpool x reader#wolverine x reader#english#writer stuff#writing#language#descendants x reader#love it#fantastic#incredible#majestic#awesome#funny#entertainment#one direction

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

Furry fanfic filled with very puzzling descriptions of what various characters are doing with their penises until you realise it's taking place in an alt-historical linguistic milieu where the Latin pēnis never became a genital euphemism and it's just talking about their tails.

#media#fandom#fanfic#aus#alt history#furry#anthro#language#linguistics#word nerdery#penis mention#(technically)

531 notes

·

View notes

Text

jury-rigged. even keel. by the board. three sheets to the wind. loose cannon. son of a gun. pipe down. taken aback.

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

Similar to when we were going for a walk and my child was lagging behind and told us to stop being a fast-poke.

Six year old, bouncing up and down with glee as desserts are unpacked: "I'm so appointed!"

Took me a moment to realize she had logically assumed "appointed" must be the opposite of "disappointed" and used it as a synonym for "excited."

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Semantic drift versus ethical drift

Support me this summer in the Clarion Write-A-Thon and help raise money for the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers' Workshop! This summer, I'm writing The Reverse-Centaur's Guide to AI, a short book for Farrar, Straus and Giroux that explains how to be an effective AI critic.

More than a quarter-century ago, a group of hackers decided that, as a label, "free software" was a liability, and they set out to replace it with a different label, "open source," on the basis that "open source" was easier to understand and using it instead of "free software" would speed up adoption.

They were right. The switch from calling it "free software" to calling it "open source" sparked a massive, unbroken wave of adoption, to the point where today it's hard to find anyone who will profess enmity for "open source," not even Microsoft (who once called it "a cancer").

Two motives animated "open source" partisans: first, they didn't like the ambiguity of "free software." Famously, Richard Stallman (who coined "free software") viewed this ambiguity as a feature, not a bug. He liked that "free" had a double meaning: "free as in speech" (an ethical proposition) and "free as in beer" (without cost). Stallman viewed the ambiguity of "free software" as a koan/conversation-starter: a normie, hearing "free software," would inquire as to whether this meant that the software couldn't be sold commercially, which was an opening for free software advocates to explain the moral philosophy of software freedom.

For "open source" partisans, this was a bug, not a feature. They wanted to enlist other hackers to develop freely licensed codes, and convince their bosses to adopt this code for internal and public-facing use. For the "open source" advocates, a term designed to confuse was a liability, a way to turn off potential collaborators ("if you're explaining, you're losing").

But the "open source" side wasn't solely motivated by a desire to simplify things by jettisoning the requirement to conscript curious bystanders into a philosophical colloquy. Many of them also disagreed with the philosophy of free software. They weren't excited about building a "commons" or in preventing rent extraction by monopolistic firms. Some of them quite liked the idea of someday extracting their own rents.

For these "open source" advocates, the advantage of free software methodologies – publishing code for peer review and third-party improvement �� was purely instrumental: it produced better code. Publication, peer review, and unrestricted follow-on innovation are practices firmly rooted in the Enlightenment, and are the foundation of the scientific method. Allowing strangers to look at your code, critique it, and fix it is a form of epistemic humility, an admission that we are all forever at risk of fooling ourselves, and it's only through adversarial peer review that we can know whether we are right.

This is true! Publishing code makes it better, and prohibitions on code publication make code worse. That's the lesson of the ransomware epidemics of the past decade: these started with a series of leaks from the NSA and CIA. Both agencies have an official policy of researching widely used software in hopes of finding exploitable bugs and then keeping those bugs secret, so that they will be preserved in the wild and can be exploited when the agencies wish to attack their enemies.

The name for this practice is NOBUS, which stands for "No One But US": we alone are smart enough to find these bugs, so if we discover them and keep them secret, no one else will find them and use them to attack our own people. This is a provably false proposition, and a very dangerous one.

The Vault 7, Vault 8, and NSA cyberweapon leaks blew a hole in NOBUS. Failures in the agencies' own security protocols resulted in the release of a long list of defects (mostly in versions of Windows, but other OSes and programs were affected). Malicious software authors used these as can openers to pry open millions of computers, enlisting them into botnets and/or shutting them down with ransomware.

These leaks also provided some "ground truth" for researchers who study malicious software. Once these researchers had a list of which defects the spy agencies had discovered and when, they were able to compare that list of defects that malicious software authors had discovered and exploited in the wild, and estimate the likelihood that a spy agency defect would be independently discovered and abused by the agency's enemies, who they were supposed to be protecting us from. It turns out that the rediscovery rate for spy agency bugs is about 20% per year – in other words, there's a one in five chance that a bug that the CIA or NSA is hoarding will be used to attack America and Americans within the year.

NOBUS is a form of software alchemy. Alchemy is the pre-Enlightenment version of scientific inquiry, and it resembles science in many respects: an alchemist observes phenomena in the natural world, hypothesizes a causal relationship to explain them, and performs an experiment to test their hypothesis. But here is where the resemblance ends: where the scientist must publish their results for them to count as science, the alchemists kept their findings to themselves. This meant that alchemists were able to trick themselves into thinking they were right, including about things they were very wrong about, like whether drinking mercury was a good idea. The failure to publish meant that every alchemist had to discover, for themself, that mercury was a deadly poison.

Alchemists never figured out how to transform lead into gold, but they did convert the base metal of superstition into the precious metal of science by putting it through the crucible of disclosure and peer-review. Both open source and free software partisans claim transparency as a key virtue of their system, because transparency leads to improvement ("with enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow").

At the outset, "open source" and "free software" were synonyms. All code that was open was also free, and vice-versa. But over the ensuing decades, that changed, as Benjamin "Mako" Hill explained in his 2018 Libreplanet keynote, "How markets coopted free software’s most powerful weapon":

https://mako.cc/copyrighteous/libreplanet-2018-keynote

As Hill explains, the philosophical differences between "open" (making better code) and "free" (making code to enhance human freedom) may not have mattered at the outset, but they each served as a kind of pole star for its own adherents, leading them down increasingly divergent paths. Each new technology and practice represented a decision-point for the movement: "Is this something we should embrace as compatible with our project, or should we reject it as antithetical to our goals?" If you were an "open source" person, the question you asked yourself at each juncture was, "Does this new thing increase code-quality?" If you were a "free software" person, the question you had to answer was, "Does this make people more free?"

These value judgments carried enormous weight. They influenced whether hackers would work to improve a given package or pursue a use-case; they determined who would speak or exhibit at conferences, they created (or deflated) "buzz," and they influenced the direction that new license versions would take, and whether those licenses would be permissible on influential software distribution channels. For a movement that runs on goodwill as much as on dollars, the social acceptability of a practice, a license, a technology or a person, mattered.

Hill describes how chasing openness without regard to its consequences for freedom created a strange situation, one in which giant tech monopolists have software freedom, while the rest of us have to make do with open source. All the software that powers the cloud systems of Facebook, Google, Apple, Microsoft, etc, is freely licensed. You can download it from Github. You can inspect it to your heart's content. You can even do volunteer work to improve it.

But only Google, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook get to decide whether to run it, and how to configure it. And since nearly all the code our users depend on takes a loop through a Big Tech cloud, the decisions made by these Big Tech firms set the outer boundaries of what our code can do. They have total freedom while we make do with the crumbs they drop from on high.

In other words, the freedom mattered, and when we forgot about it, we lost it.

Which is not to say that free software doesn't benefit from open source's popularity. The vast cohort of people who have been won over by open source's instrumental claims to superior code are the top of a funnel that free software partisans can operate to convince these people to consider the ways that their lives have been made more free through open code, and to prioritize freedom, even ahead of code quality.

The free/open source movement is actually a coalition of people who share some goals even if they differ on others. Coalitions are politically powerful. Nearly everything that happens, happens because a coalition has been pulled together:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/01/06/how-the-sausage-gets-made/#governing-is-harder

But coalitions are also brittle, because after they get what they want (transparency for code), then they have to resolve their differences, which means that some members of the coalition are going to be bitterly disappointed.

After all, there's code that we don't want to make better – at least, not if we care about human freedom. For example: code that helps ICE kidnap our neighbors. Code that powers drones. Code that spies on us, both for governments and for private-sector snoops, like the data-broker industry. Code that helps genocidiers target Gazans. Code that helps defeat adblockers. Code that helps locate new sites for fossil fuel extraction, and code that helps run fossil fuel extraction operations. Human freedom has an inverse relationship to this code: the better this code is, the worse off we all are.

Periodically, some free software advocate will follow this to its logical conclusion and propose a new free software license that prohibits use for some purpose: "you may not use my code in the military," or "you may not use my code for ad-tech," or "you may not use my code in ways that despoil the environment."

It's not surprising that this is a recurring event. After all, if you care about software as a tool for enhancing human freedom, and you notice that your code is being used to make people less free, it's natural to want to do something about it.

And yet, every one of these efforts have foundered – and I think every one will. This isn't because ethics clauses in license are a foolish idea, but because they are logistically transcendentally hard to get right.

First, there is the problem of writing good "legal code." Free software licenses are extraordinarily hard to get right. Not only do the terms have to spell out the rights and obligations of participants in the software project, but the whole system needs to be designed so that these clauses can be enforced. The right to sue for breaching a license is determined by "standing" – only people who have been injured by a license violation have the right to seek justice in court. This has proven to be a serious technical challenge in free software licensing, and if you screw it up, you'll end up with an unenforceable license:

https://pluralistic.net/2021/10/20/vizio-vs-the-world/#dumbcast

Even if you figure out all that stuff, it's possible for even extremely talented lawyers working in collaboration with the most ethical of technologists to make subtle errors that take years or decades to surface. By that time, there might be millions or even billions of works that have been released under the defective version of the license, and no practical way to contact the creators of all those works to get them to relicense under a patched version of the license.

This isn't a hypothetical risk: for more than a decade, every version of every flavor of Creative Commons license had a tiny (but hugely consequential) defect. These licenses specified that they "terminated immediately upon any breach." That meant that if you made even the tiniest of errors in following the license terms, you were instantly stripped of the protections of the CC license and could be sued for copyright infringement. Many billions of works were released under these older CC licenses.

Today, a new kind of predator called a "copyleft troll" exploits this bug in order to blackmail innocent Creative Commons users. Multimillion dollar robolawyer firms like Pixsy represent copyleft trolls who release timely images under ancient CC licenses in the hopes that bloggers, social media users, small businesses and nonprofits will use them and make a tiny error in the way they attribute the image. Then Pixsy helps the troll extort hundreds or thousands of dollars from each victim, under threat of a statutory damages claim of $150,000 per infringement:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/01/24/a-bug-in-early-creative-commons-licenses-has-enabled-a-new-breed-of-superpredator/

Creative Commons spent millions over years, working with a who's-who of international copyright and licensing experts, and it took them more than a decade to fix this bug, and the billions of works released under the old licenses are ticking time-bombs. After all, the copyright in those works will last for 70 years after their authors die, which means that anyone who acquires the copyright to those older images could turn troll and go hunting.

There's a reason that old FLOSS hands react with instant derision whenever someone proposes making up a new software license. It's the same reason cryptographers are so hostile to the idea of people rolling their own ciphers: no matter how smart and well-intentioned you are, there's a high likelihood that you will screw up and irrevocably place innocent people at risk. Yes, irrevocably: getting all those creators to relicense their works under a modern CC license is effectively impossible. Even projects with a relatively small number of contributors – like Mozilla – had to resort to throwing away chunks of code whose authors couldn't be located and paying someone to rewrite them under a new license.

Those are reasons not to come up with new free and/or open licenses, period. But on top of that, there's a special set of perplexities and confounders that arise when ethics clauses are added to free/open licenses.

The first of these is the definitional problem. Even seemingly simple categories can elude consensus on definition. Again, the Creative Commons licenses are instructive here: from the outset, CC licenses let creators toggle an ethics clause, called the "NonCommercial" (NC) flag. Works licensed under "NC" couldn't be used commercially. Seems simple, right?

Wrong. For years – and to this day – CC creators and users have been unable to consistently agree on what constitutes a "commercial use." If you post something, in your personal capacity, to a commercial service, is that "commercial?" Well, it had better not be, because anything you find online is going to have some kind of commercial enterprise involved in getting that file to you: a long-haul fiber provider, a data-center, a hosting company, a cloud company, a social media service, etc, etc. If "noncommercial" means "no one can make any money as a result of the distribution of this work," then an NC license would mean that works couldn't be distributed at all (even if you're just printing off copies of a cool image at home and stapling them to telephone poles, the printer ink company and the staple company are making money off of every copy you post).

The CC organization did extensive polling, conducted seminars, consulted experts, and produced a 255-page document that is fascinating and subtle:

https://mirrors.creativecommons.org/defining-noncommercial/Defining_Noncommercial_fullreport.pdf

And even with this document, CC users and creators still argue about whether some users are in and out of bounds.

Now, the CC NC ethics clause is the best case for an ethics clause in a license. CC is a centralized organization that has total authority over the text of CC licenses and exercises near-total control over their interpretation.

Now imagine how a hypothetical ethics clause in a software license would perform, given the CC NC experience. Compared with, say, "military/nonmilitary," the "commercial/noncommercial" distinction is trivial to draw. Is Ford – whose cars are in DoD motor-pools – a "military" user? What if Ford decides to boycott the Pentagon, but the Navy still buys a bunch of used Ford Focuses from a wrecking yard and fixes them up with Ford parts they buy at an Autozone: does Ford now become a "military" user of free/open software?

Categories are clusters, not shapes. This is why the right wing troll mantra "What is a woman?" is so effective: women aren't whats; they are whos, and if you try to come up with a definition that encompasses all the people who are women, it will stretch to dozen of pages and still miss people out. This isn't unique to women – almost every category defies exhaustive definition. Famously, there is no such thing as a fish:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/No_Such_Thing_as_a_Fish#Title

Neither is there any such thing as a name, an address or a date:

https://github.com/kdeldycke/awesome-falsehood

Obviously, the fact that "name" is a slippery concept doesn't stop us from introducing ourselves and referring to one another. But imagine now that we are going to create billions of works whose copyright will endure for more than a century, and if any of them fails to refer to someone by their name correctly, then any of millions of people, some of them not even born yet, could ruin some software contributor's life and maybe the lives of thousand or millions of users of their software.

And "name" – like "noncommercial" – is an easy case. The hard cases are things like "military/nonmilitary," "fossil fuel-sector/non-fossil fuel sector" etc etc. Big, distributed projects with informal institutions and leaders are poorly suited to adjudicating any of these definitional questions, but toothy ethics clauses require these loose ad-hocracies to create and enforce definitions of the most pernicious and slippery concepts of all.

I want to be clear that I'm not opposed to the idea of an ethics clause in free/open licenses. I make extensive use of both the NC and commercial CC licenses, after all. My objections are practical, not philosophical.

A couple weeks ago, I traveled to Rochdale in Greater Manchester to give the opening keynote at the 2025 Coop Congress. After my talk, I was on a panel with Chris Croome, who has been campaigning for a co-op software license:

either enforce co-operation and sharing and do not allow code to be privatised (made proprietary) or code that is released under terms that dictate that if the code is used to run a business the nature of the business must be a co-operative.

https://community.coops.tech/t/co-operative-software-licenses/4421/10

I've been thinking about this ever since and I think all my concerns about other ethics clauses apply here. Admittedly, there is a widely accepted and mature definition of "co-op," the seven "Rochdale Principles":

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rochdale_Principles

These have been around since 1937, and many of the seeming ambiguities in the language have been resolved through debate over the past 88 years. But there are plenty of entities that are recognizable as "co-ops" that exist outside of the UK, the Anglosphere and the global north that don't embrace all of these principles, or embrace them in ways that fit into the consensus as to their meaning that has emerged among Rochdale-derived co-ops. It's not merely that a "co-op" license might exclude these co-ops, but also that the enforcement mechanism for software licenses is that individual software authors retain the copyright to their lines of code, and use copyright law to threaten and punish people who violate the license terms.

This means that you could have a pool of potentially thousands of software authors, and their literary estates, who would have the right – for more than a century – to attack co-ops that use "co-operatively licensed" software on the grounds that the differ in their interpretation of what is – and is not – a co-op.

What's more, there are plenty of groups that could organize as a co-op and satisfy the software license's definition, who might nevertheless not be "ethical" by the lights of the co-op movement. Think of a firm of mercenaries that set up as a worker co-op (if this strikes you as implausible, I remind you that the most vicious, human-rights-abusing cops in the world are mostly members of "unions").

So a co-op license creates three risks:

Excluding co-operators because of small differences in which co-op principles they adopt;

ii. Including co-operators who are structured as compliant co-ops, but do terrible things; and

iii. Putting license users at the risk of copyleft trolls who exploit ambiguity in the definition of "co-op" to extort massive "settlement fees" from software users.

That all said, a co-op license has positive aspects as well. Remember what happened when we stopped stressing "freedom" in our software licenses: we got the code quality of "open," applied to all kinds of code, including code that destroys freedom. I've been involved with co-ops since I was a pre-teen, and I've experienced firsthand what happens when a co-op forgets its ethical basis in favor of instrumental goals.

Take the Mountain Equipment Co-Op, Canada's most beloved and successful consumer co-op. MEC was inspired by the US outdoor gear co-op REI, and it served Canadians proudly for decades. But like most consumer co-ops, MEC had very low member involvement, so a cabal of MBA-poisoned looters were able to take over MEC's board, change the bylaws, and then flip the co-op to a ruthless American private equity fund:

https://pluralistic.net/2020/09/16/spike-lee-joint/#casse-le-mec

MEC isn't a co-op anymore. The board's argument was that keeping MEC a co-op wasn't as important as infusing it with capital so it could source the goods its members wanted and offer them at reasonable prices. Joke's on them: after five years of PE looting, MEC's quality sucks and its prices are sky-high.

Institutional structure (like whether you are a co-op or not) can influence the kind of activity an organization engages in, but it can't control it. Keeping enshittification at bay requires multiple, overlapping constraints that prevent the institution from caving into the worst instincts of its worst members. That's why I'm rooting for Bluesky to become more federated. It's nice that they're structured as a B-corp, but that alone won't stop a dedicated investor class from replacing the current management with enshittifiers who destroy the lives of tens of millions of Bluesky users. However, if a large plurality of Bluesky users weren't actually on Bluesky, but on federated servers, they could credibly threaten Bluesky's business by defederating with it if it enshittified:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/01/23/defense-in-depth/#more-10160

So maybe the prospect of losing access to all of its business-critical software could have acted as a check on MEC's board and prevented them from sleazing up to private equity vampires. This is certainly a possible benefit to a co-op ethics clause in a software license. I'm not convinced that it outweighs the risks, though.

I'm a free software person. There are bitter free software partisans who think that the open source people stole our revolution. I understand their outrage. But I also think we left an open goal. In retrospect, choosing a deliberately confusing name in the hopes of sparking conversations was a tactical error. The cohort of potential movement supporters who also enjoy word-games is smaller than the cohort who are put off by being deliberately confused.

I also don't think it's a problem that the software freedom coalition includes people who value software freedom for purely instrumental reasons – because open code is better code. I do think it's a problem that they are the senior partners in the coalition and have steered it for a quarter-century. After all, they steered it into this ditch where tech monopolists have free software and we all make do with open source.

Coalitions, though, are hugely important. Take the as-yet-nameless coalition lined up against corporate power, which has defied political science's laws of gravity, pushing antitrust enforcement across the world, against the world's largest and most powerful corporations:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/06/28/mamdani/#trustbusting

This coalition needs a name. I often cite James Boyle's explanation of the role the word "ecology" played in bringing together thousands of disparate issues (spotted owls, ozone depletion) under a single banner and turning them into a movement. The anti-corporate-power movement doesn't have a name that can unite labor, climate, environment, antitrust, anticorruption, antigenocide, antiracist, antisexist, antitransphobic groups under one banner. Almost all of our definitional terms are "anti-something," from "antitrust" to "antifascist." We have no end of words to describe what we stand against (even "enshittification"'s opposite is "disenshittification"), but we still lack a word to express what we're for.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/07/14/pole-star/#gnus-not-utilitarian

Image: Muhammad Mahdi Karim https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blue_Wildebeest,_Ngorongoro.jpg

GNU FDL https://www.gnu.org/licenses/fdl-1.3.html

--

EC https://www.flickr.com/photos/baumderjustiz/4797771263/

CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#language#activism#floss#foss#free software#gnu#open source#oss#open source software#technology#pluralism#mako#benjamin mako hill#benjamin hill#copyleft trolls#semantics#semantic drift

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

We ask your questions anonymously so you don’t have to! Submissions are open on the 1st and 15th of the month.

#polls#incognito polls#anonymous#tumblr polls#tumblr users#questions#polls about language#submitted june 1#ikea#pronunciation#language

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐂𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧-𝐭𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫

A person who observes other people's activities from his or her window, esp. in a furtive and prying manner; a nosy neighbour.

#english language#langblr#words#spilled words#spilled ink#writing#creative writing#writeblr#writers on tumblr#resources for writers#writers and poets#writing prompt#definition#vocabulary#writer#writing inspiration#vocab#language

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

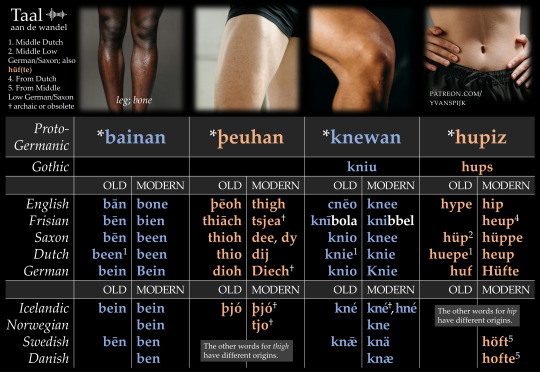

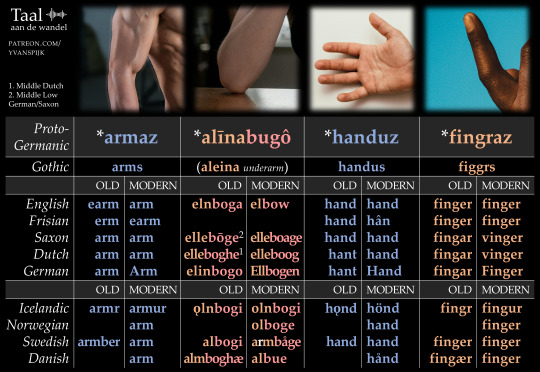

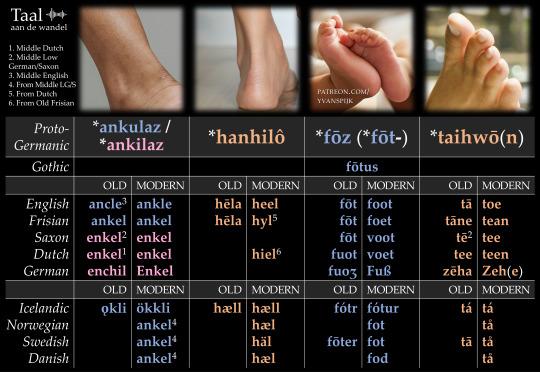

A Proto-Germanic body check - part 2

What's your *alīnabugô? It's the reconstruction of what people speaking Proto-Germanic, the distant ancestor of English, called an elbow 2000 years ago. Here's my second and last set of four graphics showing sixteen body parts in Proto-Germanic and its major medieval and modern daughter languages.

Please note that these graphics focus on etymology instead of meaning. Some of the modern words have (slightly) different meanings than their ancestor. An example of this in English is hide, which now denotes animal skin. As a word for human skin, it was supplanted by the Norse loanword skin, which ironically meant 'animal skin'.

Tier 2 patrons and people who make a one-time purchase of € 3 / $ 3 have access to a huge audio file: 115 words recorded in reconstructed Proto-Germanic and the reconstructions of its medieval daughter languages! Click here to access the file on Patreon.

#historical linguistics#linguistics#language#etymology#english#dutch#lingblr#german#swedish#danish#icelandic#norwegian#low saxon#frisian#proto-germanic

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a quick note, because I've seen this a lot recently and it's been annoying me:

If you're referring to a belief or principle of something - usually a religion, but I've seen it used in reference to secular ideologies as well - then the word you are looking for is 'tenet'.

Not 'tenant'. Tenet.

36 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[An] expression of doubt by no means always makes sense, nor does it always have a point. One simply tends to forget that even doubting belongs to a language-game.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology

#philosophy#quotes#Ludwig Wittgenstein#Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology#doubt#skepticism#meaning#language

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wonder if the issue is that using "ee" and "oo" isn't something that native-English-speaking adults usually productively apply, since they already know how to spell most words that use those letter combinations, and any new word an adult encounters is likely to be from a foreign language (which usually don't use those combinations) or else a combination of familiar elements (compound word or word with affixes).

And more generally, encountering a new word as a native-speaker adult that feels like the sort of word everyone here would have learned as a child but isn't familiar at all seems kind of weird (but such a word could have been made up by a child, who doesn't yet see that as weird). "Spief" would be a bit better, since German is probably the most likely language that English would borrow from that has words of that shape.

(I think my intuition would be that foreign borrowings tend to have more open syllables (or at least more restrictions on codas) and/or more than one syllable, or are recognizable as being from a specific language, maybe. Probably something a bit more complicated than that.)

Also, I was just looking for the original post and found this: https://www.reddit.com/r/KindleUnlimited/comments/1l8f14l/from_the_depths_of_my_heart_i_changed_the_name_of/

Speef is real to me. I'm sorry for that.

52K notes

·

View notes

Note

omg all your languages?? i'm impressed AND jealous 😩 what's your first language and how did you learn the others? i really want to learn another language but i have no idea where to start

also what other languages are you learning?

YESS my friends call me miss global cause i know so many, and cause it seems my dna is from like everywhere- my native language is French and English but i grew up half in Australia then moved back to France, so i then learnt Italian there, and Russian was just a thingy i did from like primary school i think??

I mostly learnt Italian by just visiting Italy and like observing, obviously French and English were my home languages so I’m at an advantage there, the languages I’m currently learning are danish, portuguese and I just started Afrikaans recently since I’m going to South Africa again (10/10 country, do visit) but yaaa.

and don’t use Duolingo use LingQ 🙏

#f1#formula 1#formula one#language#bilingual#trilingual#whatever the term for 6 languages is#languages#italian#French#English#afrikaans#danish#portuguese#Russian#australia

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Actually, nevermind. im making my own post instead of waiting for some rando's permission to info dump. tags exist for a reason.

Why is no one talking about this scene except for the critics???

Superman 2025 spoilers below; please engage with me in this discussion please, i feel like im going feral over this. lol

The scene I am specifically talking about is the criticism about the writing choice to have Luthor broadcast to the world Superman's Kryptonian parents' message in full.

Critics think this is the writers deciding to demonize Clark's biological parents.

I personally think anyone who says that is missing the point of the scene.

If we back up, the audience is specifically made aware that Luthor is determined to dig up dirt on Superman, at any and all cost. We see his absolute hatred of Superman be underscored and emphasized over and over from the beginning to the end of the movie. So when he went into the arctic fortress and he saw the first half of the message and that the file was corrupted, he KNEW that Superman had only ever heard the first half. It was OBVIOUS the first half that Superman only ever got to see had zero indications of some ulterior motive. Saying otherwise was a blatant lie. He knew that the second half couldnt possibly affect Supermans behaviour or motives. He. Did. Not. Care.

Instead he subjected a woman into physical and memtal distress to force her to recover what was very corrupted data with zero concerns for her well being because Luthor was laser focused on his hatred of Superman. We see this obsession highlighted later when he risked the destruction of planet earth itself just so he could have a chance to kill Superman. Its even the one thing that made him start the war: his hatred for Superman. He wanted an excuse to kill him and he didnt care how many human lives were killed or ruined in his determination to do so.

Then we hear the second half and it is very clearly spoken in Kryptonian. This is not just a foreign language, this is a language that didnt even originate on Earth. This message is the only known Kryptonian media for translation teams to work with.

To fully understand the gravity of how cruel and deliberate Luthor's 'exposé' on Superman's parents was, you also need to understand how language and translation actually works.

Do you know why Google Translate is so bad at actually translating from language to language? Its because of word for word translations. Its because it is a robot that cannot understand tone or linguistic mannerisms or language culture. It is over literal and cannot translate with any nuance.

now dont get me wrong, translating word for word absolutely has benefits, namely for learning a new language and to help you understand the way that language culture thinks. But it is trash for actually conveying true meaning. All word for word is, is a STARTING place for translating. Thats it.

We see the issue of language culture and mannerisms clearly when we compare the English language from the United States to Europe to Australia. The same word can mean drastically different things, but it is all still English. Thats because culture has a massive influence to the actual meaning of the individual words.

This is true of ALL. LANGUAGES. And then on top of that, you have individual mannerisms and tonal inflections. In some cultures, talking loudly is considered normal communication style while in a different person or language culture, speaking loud is rude and indicates anger and conflict. Even pacing of the syllables can change a meaning and so can facial expressions!

All these are nuances within just the languages on earth where there is (usually) a very great abundance of material for translators to work with.

But Krypton has only one known living person in existence (until Kara shows up, but thats neither here nor there). This lone survivor knows NOTHING about his own people. planet. Culture. If not even HE knows anything, there is no way possible to form an iron clad translation of the only kryptonian material they have to work with.

So when Lex Luthor told the interviewer and the world that Superman's "secret goal" was to build a harem and rule the world.... thats the interpretation he was looking for. Not the actual intent behind the message. The interviewer even ASKED Luthor if there was any room for an alternative interpretation. But Luthor, despite everything he should know about linguistics that i stated above, LIED and said no.

FYI, there is ALWAYS room for interpretation, even in your own native language. Thats why we have dictionaries! and the thesaurus! Thats why you have to be certified to become a language interpreter! Thats why its called spinning a story in your favour- which, by the way, is exactly what Luthor was doing.

He made the most disingenous interpretation of the message he possibly could. A much more likely and KINDER interpretation of the footage would be something to the effect of "You are the last survivor of Krypton. Please, do not let us go extinct. Get married and have children so that the legacy of Krypton will live on. The people we sent you to are of a much simpler civilization, they are very far behind technologically. you must help guide them to a better way of life."

So what Luthor effectively did was destroy Superman's reputation, self esteem, sense of identity, sense of purpose, AND stripped away from him the one and only thing that tied Superman to his birth world and people, parents, and culture.

The movie didnt ruin his parents. That was solely Luthor's manufacturing.

#superman 2025#superman spoilers#discourse#translation#translation scene#language#linguistics#translator#etymology#info dump

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you cooked up the written form of the angelic language of Lishepus before, like an alphabet?

No, I didn't figure that would ever require a written form. It was used at a time when humans didn't really have writing, so why would they have come up with one for what was essentially a human pidgin?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Huh, well, that's what language does!

I’ve been listening to the people in the apartment below me have arguments for two years now and I still can’t figure out what language they’re speaking. The best I can narrow it down is like if Portuguese and Hebrew had a baby. Is that a common pidgin combination

47K notes

·

View notes