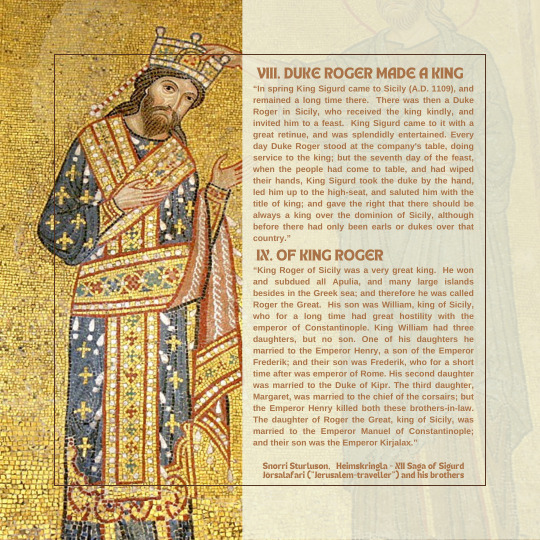

Text

#snorri sturluson#heimskringla#roger ii of sicily#history#vikings#sigurd the crusader#house of hauteville#norman swabian sicily#people of sicily#myedit

1 note

·

View note

Text

November 8th 1934, the Swedish Academy assigns del Nobel Prize in Literature to Luigi Pirandello.

Luigi Pirandello, (born June 28, 1867, Agrigento, Sicily, Italy—died Dec. 10, 1936, Rome), Italian playwright, novelist, and short-story writer, winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize for Literature. With his invention of the “theatre within the theatre” in the play Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore (1921; Six Characters in Search of an Author), he became an important innovator in modern drama.

[from Encyclopedia Britannica]

"I take deep satisfaction in expressing my respectful gratitude to Your Majesties for having graciously honoured this banquet with your presence. May I be permitted to add the expression of my deep gratitude for the kind welcome I have been given as well as for this evening’s reception, which is a worthy epilogue to the solemn gathering earlier today at which I had the incomparable honour of receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1934 from the august hands of His Majesty the King.

I also wish to express my profound respect and sincere gratitude to the eminent Royal Swedish Academy for its distinguished judgment, which crowns my long literary career.

For the success of my literary endeavours, I had to go to the school of life. That school, although useless to certain brilliant minds, is the only thing that will help a mind of my kind: attentive, concentrated, patient, truly childlike at first, a docile pupil, if not of teachers, at least of life, a pupil who would never abandon his complete faith and confidence in the things he learned. This faith resides in the simplicity of my basic nature. I felt the need to believe in the appearance of life without the slightest reserve or doubt.

The constant attention and deep sincerity with which I learned and pondered this lesson revealed humility, a love and respect for life that were indispensable for the assimilation of bitter disillusions, painful experiences, frightful wounds, and all the mistakes of innocence that give depth and value to our experiences. This education of the mind, accomplished at great cost, allowed me to grow and, at the same time, to remain myself.

As my true talents developed, they left me completely incapable of life, as becomes a true artist, capable only of thoughts and feelings; of thoughts because I felt, and of feelings because I thought. In fact, under the illusion of creating myself, I created only what I felt and was able to believe.

I feel immense gratitude, joy, and pride at the thought that this creation has been considered worthy of the distinguished award you have bestowed on me.

I would gladly believe that this Prize was given not so much to the virtuosity of a writer, which is always negligible, but to the human sincerity of my work."

Luigi Pirandello’s speech at the Nobel Banquet at the City Hall in Stockholm, December 10, 1934

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tre Piscine Cala del Cuore, Capo Zafferano, Bagheria, Palermo, Sicily

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best holy water fonts ever! These 17th century marble sculptures are inside the main entrance to Chiesa di San Giuseppe dei Teatini in Palermo, Sicily. They are the work of Ignazio Marabitti and his pupil Filippo Siracusa. Each one measures about 6 feet (1.8 meters) high.

Photos by Charles Reeza

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borgo Parrini. Partinico

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

palermo

sicilia (italia)

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Vere novo , priori jam mutato consilio , Alienora virgo regia , insignis facie , sed prudentia & honestate prestantior , futura Regina Sicilie , atque cum ea Nymphe obsequiis apte regalibus , accepta benedictione parentum , ab urbe Neapoli gloriosas discessit , per Calabriam , propter maris tedium , usque Regium iter agens : quam discedentem Neapolitane matres , quantum spectantes oculi capere potuerunt , effusis pre gaudio lacrimis affequute sunt.

Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I, p.456-457

Eleonora was born in Naples in the summer of 1289 as the tenth child (third daughter) of Carlo II lo Zoppo of Anjou, King of Naples, Count of Anjou and Maine, Count of Provence and Forcalquier, Prince of Achaea, and of Maria of Hungary.

Nothing, in particular, is known about her childhood, which she must have spent with her numerous siblings in the many castles of the Kingdom.

She is first mentioned in a Papal bull dated 1300 in which Boniface VIII annulled the marriage of 10 years-old Eleonora to Philippe de Toucy, Prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli, (the contract had been signed the year before) on account of the bride’s young age and the fact that family hadn’t asked for the Pope’s dispensation.

Two years later, there were discussions of a match with Sancho, the second son (and later successor) of Jaume II of Majorca, but the engagement never occurred.

Finally, in 1302, Eleonora’s fate was sealed. On August 31st 1302 the Houses of Anjou-Naples and of Barcelona signed the Peace of Caltabellotta, which ended the first part of the War of the Sicilian Vespers and settled (or tried to) the problem of which House should have ruled over Sicily. Following this treaty, the old Norman Kingdom’s territory (disputed between the French and Spanish born ruling houses) was to be divided into two parts, with Messina Strait as the ideal boundary line. The peninsular part, the Kingdom of Sicily, now designed as citra farum (on this side of the farum, meaning the strait, later simply known as the Kingdom of Naples ), and the island of Sicily, renamed the Kingdom of Trinacria, designed as ultra farum (beyond the farum).

The Peace of Caltabellotta stipulated that Angevin troops should evacuate the island, while the Aragonese ones should leave the peninsular part. Foundation of the peace would have been the marriage between princess Eleonora of Anjou and King Federico III (or II) of Sicily (“e la pau fo axi feyta , quel rey Carles lexava la illa de Sicilia al rey Fraderich, que li donava a Lieonor, qui era e es encara de les pus savies chrestianes, e la millor qui el mon fos, si no tant solament madona Blanca, sa germana, regina Darago. E lo rey de Sicilia desemparava li tot quant tenia en Calabria e en tot lo regne: e aço se ferma de cascuna de les parts, e que lentredit ques llevava de Sicilia; si que tot lo regne nach gran goig." in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII). The pact dictated also that once Federico had died, the two kingdoms would be reunited under the Angevin rule. This clause won’t be fulfilled.

The bridal party had to wait until spring 1303 before setting off for her new country since sea storms had damaged part of the fleet and thus delayed the departure. The voyage had cost 610 ounces, where the Florentine bankers Bardi and Peruzzi were asked to advance the payment, and the groom pledged to repay them 140 ounces.

By May 1303, Eleonora and her companions arrived in Messina where she was warmly welcomed and where on Pentecost, May 26th, of the same year she got married to Federico in Messina’s Cathedral (“E a poch de temps lo rey Carles trames madona la infanta molt honrradament a Macina, hon fo lo senyor rey Fraderich, qui la reebe ab gran solemnitat. E aqui a Macina, a la sgleya de madona sancta Maria la Nova, ell la pres per muller e aquell dia fo llevat lentredit per lola la terra de Sicilia per un llegat del Papa, qui era archebisbe, que hi vench de part del Papa, e foren perdonats a tot hom tots los pe cats quen la guerra haguessen feyts: e aquell dia fo posada corona en lesta a madona la regina de Sicilia, e fo la festa la major a Macina que hanch si faes.” in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII).

After the wedding, most of the bridal party returned to Naples, while the newlyweds proceeded to Palermo.

On July 14th 1305 Eleonora gave birth to the heir, who was called Pietro in honour of the child’s paternal grandfather, Pere III of Aragon. To celebrate his son’s birth, Federico III gifted his bride of Avola castle and the surrounding land, to which will be added the city of Siracusa (in 1314), Lentini, Mineo, Vizzini, Paternò, Castiglione, Francavilla and the farmhouses in Val di Stefano di Briga. This gift would mark the creation of the Camera reginale, which would become the traditional wedding present given to Sicilian Queen consorts, and eventually would be abolished in 1537.

Including Pietro, she would give birth to nine children: Costanza (1304 – post 1344), future Queen consort of Cyprus, Armenia and Princess consort of Antiochia; Ruggero (born circa in 1305 - ?) who would die young; Manfredi (1306-1317) first among his brothers to hold the title of Duke of Athens and Neopatras; Isabella (1310-1349) Duchess consort of Bavaria; Guglielmo (1312-1338) Prince of Taranto and heir to the Duchy of Athens and Neopatras following the death of his brother; Giovanni (1317-1348) Duke of Randazzo, Count of Malta, later also Duke of Athens and Neopatras and Regent of Sicily; Caterina (1320-1342) Abbess of St. Claire Nunnery in Messina; Margherita (1331-1377) Countess Palatine consort of the Rhine.

Through these donations Eleonora became a full-fledged vassal, and had to pay homage to her husband the King. Thanks to official documents, we get the idea that Eleonora tried to manage her lands as much personally as she could do, naming herself vicars, administrators, and granting tariff reductions. Federico indulged his wife as much as he could, although in some cases (like the management of the city of Siracusa) his will was the only one taken into account.

Despite almost every time she was unsuccessful, Eleonora fully embraced her role as mediator between the Aragonese and Angevins. For example, in 1312 her brother-in-law, King Jaume II of Aragon, asked her to dissuade her husband (Jaume’s brother) to ally himself with the Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VII of Luxembourg since this alliance could generate new friction with the Angevin Kingdom, as well as with the Papacy (with the risk of stalling the Aragonese occupation of Sardinia). After the King of Aragon, it was Pope Clemente’s turn to ask Eleonora to convince Federico to make peace with Roberto of Anjou. In both cases, though, her conciliatory efforts didn’t work.

In 1321 she witnessed her son Pietro being associated to the throne and thus crowned in Palermo (“Anno domini millesimo tricentesimo vicesimo primo, dum Johannes Romanus Pontifex contra Fridericum Regem, & Siculos propter invasionem bonorum Ecclesiarum precipue fulminaret, Fridericus Rex primogenitum suum Petrum, convenientibus Siculis, coronavit in Regem, & patris obitum, inopinatum premetuens, & ut filius qui purus videbatur & simplex, ab adoloscentia regnare cum patre affuesceret patrisque regnando vestigiis inhereret […]” in Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum ..., I, p. 482). Pietro’s coronation publicly violated the Treaty of Caltabellotta (as the Kingdom should have returned to the House of Anjou), causing the pursuing of warfare between Naples and Palermo. Once again Eleonora’s attempts at peace-making failed miserably, with her nephew, Carlo Duke of Calabria, refusing to even meet her in 1325, after he had successfully raided the outskirts of Messina.

The Queen didn’t have much luck in internal policy too as she failed to appease her husband and her protegé, Giovanni II Chiaramonte. After gravely wounding Count Francesco I Ventimiglia of Geraci (his brother-in-law and one of the King’s trustees), all that Eleonora could do was advise Chiaramonte to flee to avoid the death penalty.

Nevertheless, the Pope still hoped to use the Queen (who, at that time and alone in her Kingdom, was exempted from the Papal interdict) as mediator with her husband, promising to lift the excommunication in exchange for Federico’s backing down. Once again nothing happened.

On June 25th 1337 Federico III died near Paternò. He was buried in Catania since it was too hot for the body to be transported to Palermo (“Feretrum humeris nobiliores efferunt. Adsunt Regii filii, proceresque Regni. Exequias Regina, illustribus comitata matronis, prosequitur.” in Francesco Testa, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis, p.225). After the death of her husband, the now Dowager Queen turned to religion, following the example of those in her family who had consecrated themself to Christ (“At Heleonora certiorem fe de illa consolandi rationem inivit. Ipsa enim , ut Rex excessit e vita, ei, qui omnis consolationis fons est, fese in Virginum collegio Franciscanæ familiæ Catinæ devovit; in hoc Catharinan , & Margaritam filias imitata, quæ in ætatis flore, falsis terrestribus, contemptis bonis, Christ, cui fervire regnare est, in sacrarum Virginum Messanensi Collegio, de Basicò dicto, ejusdem Franciscanæ familiæ fese consecrarant; quod Collegium posteaquam Catharina fancte gubernavit, sanctitatis opinione commendata deceffit” in Francesco Testa, De vita..., p.226).

If Eleonora might have hoped to exert some kind of influence as many other Queen mothers did in the past and would do in the future over their weak-willed royal children, she would soon realize she had a powerful rival in the new Queen consort, her daughter-in-law, Elisabetta of Carinthia. Like Eleonora, the new Queen supported the Latin faction (a group of Sicilian noblemen who opposed the Aragonese rulership over Sicily, hoping the island would be returned under the influence of the Angevins instead). But, while Elisabetta had managed to raise the Palizzis to the highest positions at court, her mother-in-law still supported the Chiaramonte, making it possible for the exiled Giovanni II to return to Sicily, be pardoned by the King and see all his goods be returned. Soon though Chiaramonte resumed his personal feud against the Ventimiglia (also part of the Latin faction) and once again Eleonora's attempt to bring peace failed miserably. Only through Grand Justiciar Blasco II d'Alagona's intervetion, the crisis was averted.

In 1340, the Dowager Queen made a last attempt to appease the new Pope, Benedict XII. Unfortunately, the Sicilian envoys sent to Avignon to take an oath of vassalage (since Norman times Sicily theoretically belonged to the Papacy, who granted it to the Sovereigns who acted as Papal Legates) were treated roughly by the Pope, who declared Roberto of Anjou (Eleonora's brother) as Sicily's legitimate King.

Deeply distraught, the Dowager Queen resolved to definitely retire from public life. She spent what it remained on her life visiting the monastery of San Nicolo' d'Arena (Catania), joining the monks in their religious life. She died in one of the monastery's cells on August 10th 1341. Her body would be buried in the Church of San Francesco d'Assisi all'Immacolata (Catania), the construction of which she had personally promoted in 1329 to thank the Virgin Mary for protecting the city from one of many Mount Etna's eruptions.

Sources

AMARI MICHELE, La guerra del Vespro siciliano

CORRAO PIETRO, PIETRO II, re di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 83

DE COURCELLES JEAN BAPTISTE PIERRE JULLIEN, Histoire généalogique et héraldique des pairs de France: des grands dignitaires de la couronne, des principales familles nobles du royaume et des maisons princières de l'Europe, Vol. XI,

FODALE SALVATORE, Federico III d’Aragona, re di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 45

GREGORIO ROSARIO, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I,

KIESEWETTER ANDREAS, ELEONORA d'Angiò, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 42

de MAS LATRIE LOUIS, Histoire de l'île de Chypre sous le règne des princes de la maison de Lusignan. 3

MUNTANER RAMON, Crónica catalana

Sicily/naples: counts & kings

TESTA FRANCESCO, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis

#historicwomendaily#historical women#history#history of women#herstory#eleanor of naples#frederick iii of sicily#house of aragon and sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#myedit#historyedit

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sicilia: Val dos Templos

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“In the year of the Incarnation of the Savior 1089, Count Roger took a new wife, his former one, Eremberga, daughter of Count William of Mortain, having died. Her name was Adelaide and she was the niece of Boniface, that most renowned marquis of Italy; to be precise, she was the daughter of Boniface’s brother. She was a young woman with a very becoming face.”

Goffredo Malaterra, The Deeds of Count Roger of Calabria and Sicily and of his Brother Duke Robert Guiscard, book 4, ch. 14

Adelasia (or Adelaide) was born around 1074 in Northwestern Italy. Her parents were Manfredi (or Manfredo) Incisa del Vasto, a member of the Aleramici House, and his unnamed wife. From her paternal side, she was the niece of Bonifacio, Marquis of Savona and of Western Liguria, “the most renowned marquis of Italy” (in Goffredo Malaterra, The Deeds of Count Roger ..., book 4, ch. 14). Adelasia had a brother, Enrico, and two unnamed sisters.

Following their father’s tragic death (killed together with his brother Anselmo during a popular uprising in 1079), the siblings were entrusted to the guardianship of their uncle Bonifacio, although quite soon Enrico decided to travel all the way to Southern Italy to help the Norman leaders Robert and Roger Hauteville in their conquest.

The Aleramic scion was gifted with the counties of Butera and Paternò for his services. But the del Vasto family fortunes were destined to grow as Enrico’s sisters married into the newly established Hauteville comital dynasty. His unnamed sisters were betrothed to the Great Count Roger’s bastard sons Goffredo (who would die young without getting the chance to marry) and Giordano, while Adelasia married the Great Count himself.

In 1089 Roger was at his third marriage. His first (and beloved) wife Judith d'Évreux had given him only daughters before dying in 1076. The following year, he married Eremburge de Mortain, who bore him his first legitimate son, Malgerio, and died in 1089. With just a son (who would die young around 1098) as heir, it isn’t surprising Roger remarried. The choice of an Italian wife (his previous ones had been fellow Frenchwomen) was part of the Hautevilles’ strategies to latinize Southern Italy by welcoming Gallo-Italic immigrants with the hoped result to counter the already existing Greek-Arabic majority.

Adelasia would bore Roger two sons: Simone (born in 1093) and Ruggero (born in 1095 – although Malaterra records “in the year of the Incarnation of the Lord 1098, Countess Adelaide became pregnant again by Count Roger” in Goffredo Malaterra, The Deeds of Count Roger ..., book 4, ch. 26) and at least one daughter: either Matilda (born between 1093-1095, future Countess consort of Alife) or Maximilla (birth date unknown, future wife of Count Palatin Ildebrandino VI Aldobrandeschi), or perhaps both of them.

The Great Count died on June 22nd 1101 in Mileto (Calabria). Following her late husband’s wishes, 27-years old Adelasia assumed the regency of the county for her 8-years old son, Simone, who became the new Count of Sicily. She smartly surrounded herself with capable and trusted men, like her brother Enrico, or Christodulos, a Greek Orthodox (possibly a Muslim convert) admiral who had been nominated amiratus (Grand Dignitary) of Sicily already under Ruggero I.

Little Count Simone’s rulership was tragically shortlived as the child died in Mileto, on September 1105, at just 12 years old. He was succeeded by his younger (and, according to the sources, better-suited) brother, Ruggero. As the new Great Count was even younger (10 years old), Adelasia resumed her role of Regent. It is in this period, precisely in 1109, that the Warrant of Countess Adelasia, Europe’s oldest known paper document, was issued.

Although a more generous patron for the Latin clergy, Adelasia maintained a good relationship with the Muslim and Greek communities, granting them freedom of worship and a relevant administrative autonomy (so that in a Greek-Arab charter dated 1109 she is called malikah). She was well aware that, following the change of ownership, her adoptive country was in need of a stabler bureaucratic apparatus, justice administration and a proper capital city. Mileto had been dear to her late husband, but Adelasia had different ideas. Although she preferred Messina for its strategic position, she realised Palermo, having been the capital of the Sicilian Emirate and thus adorned with splendid buildings, was better suited to become the capital of the Hauteville counts. In 1112 she moved the capital from Mileto to Palermo and that same year she stepped back from the Regency, allowing her son Ruggero to start ruling by his own right.

Not used to sitting around and willing to increase her son’s power and fortunes, the dowager Countess accepted to marry in 1113 the childless and older Baodouin I, King of Jerusalem. Prenuptial agreements stated that, in the absence of issue, the Kingdom of Jerusalem would have been inherited by Ruggero and his descendants. This royal marriage proved to be a faux pas as Boudouin was still legally married to his second wife, Arda of Armenia. The King had merely decided to chase her away, sending poor Arda to live in a nunnery, but then simply allowed her to go back to her father’s home in Constantinople without properly annulling the marriage and casting the shadow of bigamy over the new marital union. Moreover, always in need of money to pay for the troops, soon Baodouin spent all of Adelasia’s dowry. Taking advantage of a temporary illness, Papal Legate Arnoul de Chocques convinced the King to annul the marriage so that his wife could be sent back to Sicily. Despite complying, the King was not the least happy as he wished to milk some more the of his Norman wife’s riches, but as the royal union was still childless, Pope Pasquale II could not risk seeing the Hauteville expand their influence over the Holy Land in a possible near future.

In 1117, after four dissatisfying years as Queen Consort of Jerusalem, Adelasia returned back to Palermo. She spent the last year of her life devoting herself to religion. She died in Patti (near Messina) on April 16th 1118 and was buried in the city’s cathedral, where she still lies.

In 1130, her beloved son Ruggero would be crowned the first King of Sicily. According to chronicler William of Tyre, Ruggero never forgot the humiliation his mother had to suffer in Jerusalem so that he and his heirs never truly reconciled with the Kingdom of Jerusalem (“Qua redeunte ad propria, turbatus est supra modum filius; et apud se odium concepit adversus regnum et ejus habitatores, immortale” William of Tyre, Chronicon, XI.29)

Sources

Brugnoli Alessio, La tomba di Adelasia del Vasto

Catlos Brian A., Infidel kings and unholy warriors : faith, power, and violence in the age of crusade and jihad

Curtis Edmund, Roger of Sicily and the Normans in Lower Italy, 1016-1154

Edgington Susan B., Baldwin I of Jerusalem, 1100-1118

Garulfi Carlo Alberto, I documenti inediti dell'epoca normanna in Sicilia

Hayes Dawn Marie, Roger II of Sicily. Family, Faith, and Empire in the Medieval Mediterranean World

Houben Hubert – Loud Graham A. - Milburn Diane, Roger II Of Sicily: A Ruler Between East And West

Malaterra Goffredo, The Deeds of Count Roger of Calabria and Sicily and of his Brother Duke Robert Guiscard

Pontieri Ernesto, ADELAIDE del Vasto, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 1

Tocco Francesco Paolo, Ruggero I, conte di Sicilia e Calabria, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 89

Tocco Francesco Paolo, Ruggero II, re di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 89

William of Tyre, Chronicon

#women#history#historicwomendaily#women in history#historical women#Adelasia del Vasto#House of Hauteville#ruggero i#Ruggero II#baldwin i of jerusalem#simone di sicilia#norman swabian sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emilio Pucci's bikini inspired by the mosaics of Piazza Armerina in the 1950s

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Palermo, Sicilia, Italia. 04/2023

962 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agrigento. Tempio di Giove Olimpico

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaic Greek terracotta antefix in the form of a Gorgoneion. Artist unknown; 6th century BCE. Now in the Museo archeologico regionale, Gela, Sicily. Photo credit: Sailko/Wikimedia Commons.

416 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Et quia solum Guilielmum Capuanorum Principem habebat superstitem, veritus ne eumdem conditione humanae fragilitatis amitteret, Sibiliam sororem Ducis Burgundiae duxit uxorem, quae non multo post Salerni mortua est, et apud Caveam est sepulta. Tertio Beatricem filiam Comitis de Reteste in uxoris accepit, de qua filiam habuit, quem Constantiam appellavit.

Chronicon Romualdi II, archiepiscopi Salernitani, p. 16

Beatrice was born around 1135 in the county of Rethel (northern France) from Gunther (also know as Ithier) de Vitry, earl of Rethel, and Beatrice of Namur.

On her mother’s side, Beatrice descended from Charlemagne (through his son, Louis the Pious), while on the paternal side she was a grandniece of Baldwin II King of Jerusalem (her paternal grandmother Matilda, titular Countess of Rethel, was the King’s younger sister). The Counts of Rethel were also vassals of the powerful House of Champagne, known for its successful marriage politics (Count Theobald IV of Blois-Champagne’s daughter, Isabelle, would marry in 1143 Duke Roger III of Apulia, eldest son of King Roger II of Sicily).

In 1151, Beatrice married this same Roger. The King of Sicily was at his third marriage at this point. His first wife had been Elvira, daughter of King Alfonso VI the Brave of León and Castile and of Galicia, who bore him six children (five sons and one daughter). However, when four of his sons (Roger, Tancred, Alphonse and the youngest, Henry) died before him, leaving only William as his heir, Roger II must have feared for his succession. In 1149, the King then married Sibylla, daughter of Duke Hugh II of Burgundy. She bore him a son, Henry (named after his late older brother), and two years later died of childbirth complications giving birth to a stillborn son. As this second Henry died young too, Roger thought about marrying for a third (and hopefully last) time.

It is possible that Roger’s choice of his third wife had been influenced by the future bride’s family ties with the Crusader royalties as Beatrice was related with both Queen Melisende of Jerusalem and the Queen’s niece Constance of Hauteville, ruling Princess of Antioch. Constance was also a first cousin once removed of Roger, who had (unsuccessfully) tried to snatch the Antiochian principality from her when her father Bohemond II was killed in battle 1130, leaving his two years old daughter as heir.

Beatrice bore Roger only a daughter, Constance, who was born in Palermo on November 2nd 1154. This baby girl (who would one day become Queen of Sicily) never knew her father as he died on February 26th.

Nothing certain is known about her widowed life, although we can suppose she took care of her only daughter. Beatrice died in Palermo on March 30th 1185, living enough to see Constance being betrothed to Emperor Frederick Barbarossa’s son, Henry.

The body of the Dowager Queen was laid to rest in the Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, together with her predecessor, Elvira, and her step-children, Henry, Tancred, Alphonse and Roger. Through her daughter, Beatrice would become Emperor Frederick II’s grandmother.

Sources

Cronica di Romualdo Guarna, arcivescovo Salernitano Chronicon Romualdi II, archiepiscopi Salernitani Versione di G. del Re, con note e dilucidazione dello stesso

Garofalo Luigi, Tabularium regiae ac imperialis capellae collegiatae divi Petri in regio panormitano palatio Ferdinandi 2. regni Utriusque Siciliae regis

Hayes Dawn Marie, Roger II of Sicily. Family, Faith, and Empire in the Medieval Mediterranean World

Houben Hubert, Roger II Of Sicily: A Ruler Between East And West

SICILY/NAPLES: COUNTS & KINGS

Walter Ingeborg, BEATRICE di Rethel, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 7

#historicwomendaily#women#history#women in history#historical women#House of Hauteville#Roger II of Sicily#Beatrice of Rethel#norman swabian sicily#costanza i#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Agrigento (by Luca Franzoi)

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

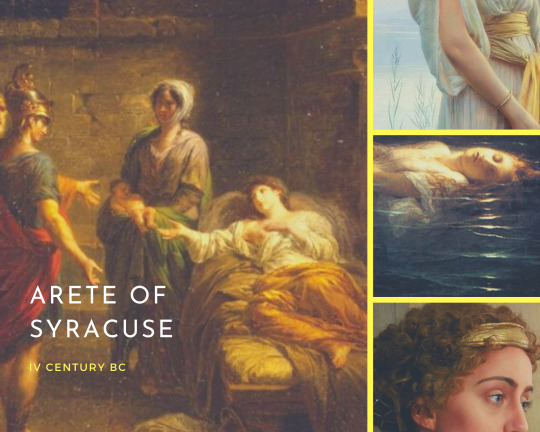

Dionysius had three children by his Locrian wife, and four by Aristomache, two of whom were daughters, Sophrosyne and Arete. Sophrosyne became the wife of his son Dionysius, and Arete of his brother Thearides, but after the death of Thearides, Arete became the wife of Dion, her uncle.

Plutarch, Life of Dion, 6-1

Arete was the daughter of Syracuse tyrant, Dionysius I, by fellow Syracusan Aristomache, in turn, the daughter of a rich and distinguished nobleman, Hipparinus. After his first wife (the unnamed daughter of politician and general Hermocrates) had been killed during a popular uprising in 405 BC, Dionysius shocked his people by simultaneously marrying two women, the Locrian Doris and the Syracusan Aristomache, in 397 BC ("Then Dionysius, after resuming the power and making himself strong again, married two wives at once, one from Locri, whose name was Doris, the other a native of the city, Aristomache, daughter of Hipparinus, who was a leading man in Syracuse, and had been a colleague of Dionysius when he was first chosen general with full powers for the war. It is said that he married both wives on one day, and that no man ever knew with which of the two he first consorted, but that ever after he continued to devote himself alike to each; it was their custom to sup with him together, and they shared his bed at night by turns " in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 3.3-4).

For a long time, Aristomache couldn't bear Dionysius any child, while Doris gave soon birth to future tyrant Dionysius II, and later to two other children, Hermocrates and Dikaiosyne. Thinking his Syracusan wife was under some spell, the tyrant identified Doris' mother as the culprit and put the poor woman to death ("And yet the people of Syracuse wished that their countrywoman should be honoured above the stranger; but Doris had the good fortune to become a mother first, and by presenting Dionysius with his eldest son she atoned for her foreign birth. Aristomache, on the contrary, was for a long time a barren wife, although Dionysius was desirous to have children by her; at any rate, he accused the mother of his Locrian wife of giving Aristomache drugs to prevent conception, and put her to death." in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 3.5-6). Later on, Aristomache would finally give birth to four children: Hipparinus, Niseus, Arete and Sophrosyne.

While for his sons Dionysius chose propagandistic names (the younger Dionysius after Dionysius himself to continue the dynasty; Hermocrates after his paternal grandfather as well as Syracusan general Hermocrates; Hipparinus after his maternal grandfather; Niseus could refer to one of the god Dionysius' epithets as a way to honour the divinity the tyrant was named after and towards whom he felt deeply connected), for his daughters he might have meant to present himself as the giver of righteousness (Dikaiosyne), virtue (Arete), and temperance (Sophrosyne). It is interesting to note that, in that same period, another Arete was living at the tyrant's court, Arete of Cyrene, daughter of philosopher Aristippus of Cyrene, and herself a philosopher. Some claim Dionysius called his daughter after Aristippus' daughter, but it might have just been a coincidence since Arete was a common name in ancient Greece. While in Syracuse, Aristippus wrote "On the Daughter of Dionysius", perhaps to ingratiate himself with the tyrant.

To strengthen his position and that of his dynasty, Dionysius had his daughters marry at a young age within the same family. Sophrosyne married her half-brother Dionysius the Younger, Dikaiosyne married her paternal uncle Leptines, while Arete married another one of her paternal uncles, Thearides. After Thearides' death, Dionysius married his daughter to her maternal uncle, Dion ("Dionysius had three children by his Locrian wife, and four by Aristomache, two of whom were daughters, Sophrosyne and Arete. Sophrosyne became the wife of his son Dionysius, and Arete of his brother Thearides, but after the death of Thearides, Arete became the wife of Dion, her uncle." in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 6.1). Arete bore him two sons, Hipparinus also called Aretaeus (it's not certain if – he was called like this at all - the second name was just a nickname to distinguish him from his maternal uncle and his paternal grandfather), born between 370-368 BC, and another unnamed son, born around 354 BC.

Like his sister Aristomache, Dion was the son of the wealthy and influential Hipparinus. After his sister married Dionysius, Dion became his brother-in-law's most trusted adviser. One of Plato's most brilliant pupils as well as his friend, Dion had tried (unsuccessfully) to convert the tyrant to Platonism. While Dionysius was on his deathbed in 367 BC, Dion wanted to convince the dying man to favour Andromache's sons (aka Dion's nephews) in the succession to the tyranny. Unfortunately for him, Dionysius died before settling the succession matter and so he was succeeded by his elder son, Dionysius the Younger. Some authors like Timaeus of Tauromenium or Cornelius Nepos report the version that the tyrant was conveniently poisoned by the doctors, who sided with the young Dionysius II.

Since the elder Dionysius had lived with the constant fear of being betrayed and overthrown, he hadn't let his son and heir leave the palace and the area of the acropolis nor he taught him anything about politics or state government, leaving his son unprepared when he finally came to power. As the late tyrant's closer adviser, Dion kept governing the city, allowing Dionysius II to keep enjoying his life, without worrying about the care of the state. In an attempt to educate the young tyrant, Plato was called once again to Syracuse. The philosopher's teaching affected Dionysius so much, he declared his intention to stop being a tyrant. This statement shocked Dionysius' supporters (and among them historian and military commander Philistus, who had married into the family), who feared Syracuse would have lost her strength and supremacy under a philosopher's rule (and, of course, they knew they would have to say goodbye to their influence over the weak-willed tyrant).

Thanks to a stroke of luck on their part, they managed to intercept a letter meant for the Carthaginian government. In the said letter, Dion (as a Syracusan ambassador) was asking the Carthaginians to interact only with him in regard to peace talks. This was exactly what they needed. It was easy to persuade Dionysius his half-uncle was plotting together with their long-time Carthaginian enemies to put himself on the Syracusan throne. Perhaps considering his honourable status, Dion was just exiled from Syracuse and was allowed to keep to himself his riches and servants. With Dion's expulsion, Plato became well aware of the failure of his dream project to transform Dionysius into a philosopher king. It was hard to convince the tyrant to let him return to Greece, but in the end, he managed it with the promise to return to Syracuse once the Syracusans'd stop their war against Carthage.

Dionysius' good disposition towards his half-uncle (as well as brother-in-law) was short-lived though as he grew more and more envious of the praises and receptions Dion was receiving now that he had moved to Athens.

"Now, as long as there were many hopes of a reconciliation, the tyrant took no violent measures with his sister, but suffered her to continue living with Dion's young son; when, however, the estrangement was complete, and Plato, who had come to Sicily a second time, had been sent away in enmity, then he gave Arete in marriage, against her will, to Timocrates, one of his friends" (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 21.5-6).

Moreover, during his Greek exile, Dion received three letters, one from his (now ex) wife, one from his sister Aristomache, and one allegedly from his son. Hipparinus' letter turned out to be "[...] from Dionysius, who nominally addressed himself to Dion, but really to the Syracusans; and it had the form of entreaty and justification, but was calculated to bring odium on Dion. For there were reminders of his zealous services in behalf of the tyranny, and threats against the persons of his dearest ones, his sister, children, and wife; there were also dire injunctions coupled with lamentations, and, what affected him most of all, a demand that he should not abolish, but assume, the tyranny; that he should not give liberty to men who hated him and would never forget their wrongs, but take the power himself, and thereby assure his friends and kindred of their safety." (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 31.5-6).

These menaces spurred Dion to action. Despite Plato's attempts to dissuade him, the Syracusan philosopher decided to leave his golden exile and start, on August 357 bC, a war against Dionysius.

At that time the tyrant was sailing through the Adriatic sea, having left his city in the hands of his son Apollocrates. By the time Dionysius had reached Syracuse, only the citadel on the tiny island of Ortygia had to be yet conquered by Dion's forces.

Dionysius' fleet, commanded by Philistus, was destroyed and the same commander died during the battle. "Ephorus, it is true, says that when his ship was captured, Philistus slew himself; but Timonides, who was engaged with Dion in all the events of this war from the very first, in writing to Speusippus the philosopher, relates that Philistus was taken alive after his trireme had run aground, and that the Syracusans, to begin with, stripped off his breast-plate and exposed his body, naked, to insult and abuse, although he was now an old man; then, that they cut off his head, and gave his body to the boys of the city, with orders to drag it through Achradina and throw it into the stone quarries." (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 35.4-5) Soon Apollocrates saw that there was no hope to resist and flew away to reach his father now exiled, de facto handing over Ortygia to Dion.

"After Apollocrates had sailed away, and when Dion was on his way to the acropolis, the women could not restrain themselves nor await his entrance, but ran out to the gates, Aristomache leading Dion's son, while Arete followed after them with tears, and at a loss how to greet and address her husband now that she had lived with another man. After Dion had greeted his sister first, and then his little son, Aristomache led Arete to him, and said: "We were unhappy, Dion, while thou wast in exile; but now that thou art come and art victorious, thou hast taken away our sorrow from all of us, except from this woman alone, whom I was so unfortunate as to see forced to wed another while thou wast still alive. Since, then, fortune has made thee our lord and master, how wilt thou judge of the compulsion laid upon her? Is it as her uncle or as her husband that she is to greet thee?" So spake Aristomache, and Dion, bursting into tears, embraced his wife fondly, gave her his son, and bade her go to his own house; and there he himself also dwelt, after he had put the citadel in charge of the Syracusans." (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 51)

Arete then went back to live with her former husband and son, but she wasn't destined to a happy forever after. In 354 BC Dion and Arete's son, Hipparinus, died. It is unclear the exact dynamics of his death. Cornelio Nepos writes the youth died after falling from a roof while intoxicated ("But when he learned that the exile was levying a force in the Peloponnese and planning to make war upon him, Dionysius gave Dion's wife, Arete, in marriage to another, and caused his son to be brought up under such conditions that, as the result of indulgence, he developed the most shameful passions. For before he had grown up, the boy was supplied with courtesans, gorged with food and wine, and kept in a constant state of drunkenness. When his father returned to his native land, the youth found it so impossible to endure the changed conditions of his life - for guardians were appointed to wean him from his former habits - that he threw himself from the top of his house and so perished" Cornelio Nepos, De Viris Illustribus – X. Dion, 4.3-5), while Plutarch writes Hipparinus killed himself jumping off a roof "in a fit of angry displeasure caused by some trivial and childish grievance" (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 55.4) and Claudius Aelianus mentions that "As Dio son of Hipparinus, a Disciple of Plato, was treating about public affairs, his Son was killed with a fall from the house top into the Court. Dio was nothing troubled at it, but proceeded in what he was about before." (in Claudius Aelianus, Various History, book III, chap. IV)

During that same period, both Arete and her mother Aristomache grew suspicious of Callippus, an Athenian who had welcomed Dion in his home and later followed the Syracusan in his war against Dionysius. The two women suspected he was the one who had spread the false rumour that now childless, Dion intended to nominate Apollocrates (who was still his wife's nephew) as his heir. Their attempt to alert Dion proved to be vain as the man (who had previously allowed the death of his former ally Heracleides, an action he considered a stain on his life) thought he deserved to be killed, even at the hands of a friend.

"But Callippus, seeing that the women were investigating the matter carefully, and taking alarm, came to them with denials and in tears and offering to give them whatever pledge of fidelity they desired. So they required him to swear the great oath. This was done in the following manner. The one who gives this pledge goes down into the sanctuary of Demeter and Persephone, where, after certain sacred rites have been performed, he puts on the purple vestment of the goddess, takes a blazing torch in his hand, and recites the oath. All this Callippus did, and recited the oath; but he made such a mockery of the gods as to wait for the festival of the goddess by whom he had sworn, the Coreia, and then to do the murder." (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 56.4-6)

On June 354 BC Dion was ambushed in his home by assassins from Zacynth while he was indeed celebrating Demeter and Persephone. The attacker tried at first to strangle him, but when it proved ineffective they cut his throat as if he were the festival's sacrificial victim. No one among the friends who were previously celebrating with him attempted to help him and they all left him to his fate.

As for Arete (who was pregnant at that time) and her mother, they were incarcerated. While prisoner, the poor woman gave birth to her second (unnamed) son and was allowed to bring him up taking advantage of the fact that Callippus was busier governing the city as its new tyrant.

In 353 BC Callippus was defeated and forced to leave the city by Hipparinus, son of Dionysius the Elder and Aristomache, who became Syracuse' new tyrant. The two women and the child were so freed and entrusted to one of Dion's friends, Hicetas of Leontini.

His initial kindness towards his late friend's family soon gave way to murderous intents. "Afterwards, having been persuaded by the enemies of Dion, he got a ship ready for them, pretending that they were to be sent into Peloponnesus, and ordered the sailors, during the voyage, to cut their throats and cast them into the sea. Others, however, say that they were thrown overboard alive, and the little boy with them." (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Dion, 58.9). In his Life of Timoleon (a general from Corinth who had been sent to Syracuse – a Corinthian colony – to chase away Dionysius, who had reconquered the city in 347 BC), Plutarch adds that Dion's family was later avenged when, later on, Hicetas' wife, daughters and friends were put to death by the Syracusans (in Plutarch, Parallel Lives - Timoleon, 33.1).

Sources

CLAUDIUS AELIANUS, Various History

CORNELIUS NEPOS, De Viris Illustribus – X. Dion

MOMIGLIANO ARNALDO, DIONISIO II il Giovane tiranno di Siracusa in Enciclopedia Italiana (1931)

MUCCIOLI FEDERICOMARIA, Dionisio II: storia e tradizione letteraria

PLUTARCH, Parallel Lives – Dion

PLUTARCH, Parallel Lives – Timoleon

The collected dialogues of Plato, including the letters

ZANCAN PAOLA, DIONE tiranno di Siracusa in Enciclopedia Italiana (1931)

#women#historicwomendaily#historical women#history#women in history#arete#House of Dionysius#dionysius II#Dionysius I of Syracuse#dion#Aristomache#Greek Sicily#siracusa#province of siracusa#people of sicily#women of sicily#historyedit#myedit

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Castelmola, Italy (by Anna Biasoli)

2K notes

·

View notes