#women of sicily

Photo

Vere novo , priori jam mutato consilio , Alienora virgo regia , insignis facie , sed prudentia & honestate prestantior , futura Regina Sicilie , atque cum ea Nymphe obsequiis apte regalibus , accepta benedictione parentum , ab urbe Neapoli gloriosas discessit , per Calabriam , propter maris tedium , usque Regium iter agens : quam discedentem Neapolitane matres , quantum spectantes oculi capere potuerunt , effusis pre gaudio lacrimis affequute sunt.

Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I, p.456-457

Eleonora was born in Naples in the summer of 1289 as the tenth child (third daughter) of Carlo II lo Zoppo of Anjou, King of Naples, Count of Anjou and Maine, Count of Provence and Forcalquier, Prince of Achaea, and of Maria of Hungary.

Nothing, in particular, is known about her childhood, which she must have spent with her numerous siblings in the many castles of the Kingdom.

She is first mentioned in a Papal bull dated 1300 in which Boniface VIII annulled the marriage of 10 years-old Eleonora to Philippe de Toucy, Prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli, (the contract had been signed the year before) on account of the bride’s young age and the fact that family hadn’t asked for the Pope’s dispensation.

Two years later, there were discussions of a match with Sancho, the second son (and later successor) of Jaume II of Majorca, but the engagement never occurred.

Finally, in 1302, Eleonora’s fate was sealed. On August 31st 1302 the Houses of Anjou-Naples and of Barcelona signed the Peace of Caltabellotta, which ended the first part of the War of the Sicilian Vespers and settled (or tried to) the problem of which House should have ruled over Sicily. Following this treaty, the old Norman Kingdom’s territory (disputed between the French and Spanish born ruling houses) was to be divided into two parts, with Messina Strait as the ideal boundary line. The peninsular part, the Kingdom of Sicily, now designed as citra farum (on this side of the farum, meaning the strait, later simply known as the Kingdom of Naples ), and the island of Sicily, renamed the Kingdom of Trinacria, designed as ultra farum (beyond the farum).

The Peace of Caltabellotta stipulated that Angevin troops should evacuate the island, while the Aragonese ones should leave the peninsular part. Foundation of the peace would have been the marriage between princess Eleonora of Anjou and King Federico III (or II) of Sicily (“e la pau fo axi feyta , quel rey Carles lexava la illa de Sicilia al rey Fraderich, que li donava a Lieonor, qui era e es encara de les pus savies chrestianes, e la millor qui el mon fos, si no tant solament madona Blanca, sa germana, regina Darago. E lo rey de Sicilia desemparava li tot quant tenia en Calabria e en tot lo regne: e aço se ferma de cascuna de les parts, e que lentredit ques llevava de Sicilia; si que tot lo regne nach gran goig." in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII). The pact dictated also that once Federico had died, the two kingdoms would be reunited under the Angevin rule. This clause won’t be fulfilled.

The bridal party had to wait until spring 1303 before setting off for her new country since sea storms had damaged part of the fleet and thus delayed the departure. The voyage had cost 610 ounces, where the Florentine bankers Bardi and Peruzzi were asked to advance the payment, and the groom pledged to repay them 140 ounces.

By May 1303, Eleonora and her companions arrived in Messina where she was warmly welcomed and where on Pentecost, May 26th, of the same year she got married to Federico in Messina’s Cathedral (“E a poch de temps lo rey Carles trames madona la infanta molt honrradament a Macina, hon fo lo senyor rey Fraderich, qui la reebe ab gran solemnitat. E aqui a Macina, a la sgleya de madona sancta Maria la Nova, ell la pres per muller e aquell dia fo llevat lentredit per lola la terra de Sicilia per un llegat del Papa, qui era archebisbe, que hi vench de part del Papa, e foren perdonats a tot hom tots los pe cats quen la guerra haguessen feyts: e aquell dia fo posada corona en lesta a madona la regina de Sicilia, e fo la festa la major a Macina que hanch si faes.” in Ramon Muntaner, Crónica catalana, ch. CXCVIII).

After the wedding, most of the bridal party returned to Naples, while the newlyweds proceeded to Palermo.

On July 14th 1305 Eleonora gave birth to the heir, who was called Pietro in honour of the child’s paternal grandfather, Pere III of Aragon. To celebrate his son’s birth, Federico III gifted his bride of Avola castle and the surrounding land, to which will be added the city of Siracusa (in 1314), Lentini, Mineo, Vizzini, Paternò, Castiglione, Francavilla and the farmhouses in Val di Stefano di Briga. This gift would mark the creation of the Camera reginale, which would become the traditional wedding present given to Sicilian Queen consorts, and eventually would be abolished in 1537.

Including Pietro, she would give birth to nine children: Costanza (1304 – post 1344), future Queen consort of Cyprus, Armenia and Princess consort of Antiochia; Ruggero (born circa in 1305 - ?) who would die young; Manfredi (1306-1317) first among his brothers to hold the title of Duke of Athens and Neopatras; Isabella (1310-1349) Duchess consort of Bavaria; Guglielmo (1312-1338) Prince of Taranto and heir to the Duchy of Athens and Neopatras following the death of his brother; Giovanni (1317-1348) Duke of Randazzo, Count of Malta, later also Duke of Athens and Neopatras and Regent of Sicily; Caterina (1320-1342) Abbess of St. Claire Nunnery in Messina; Margherita (1331-1377) Countess Palatine consort of the Rhine.

Through these donations Eleonora became a full-fledged vassal, and had to pay homage to her husband the King. Thanks to official documents, we get the idea that Eleonora tried to manage her lands as much personally as she could do, naming herself vicars, administrators, and granting tariff reductions. Federico indulged his wife as much as he could, although in some cases (like the management of the city of Siracusa) his will was the only one taken into account.

Despite almost every time she was unsuccessful, Eleonora fully embraced her role as mediator between the Aragonese and Angevins. For example, in 1312 her brother-in-law, King Jaume II of Aragon, asked her to dissuade her husband (Jaume’s brother) to ally himself with the Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich VII of Luxembourg since this alliance could generate new friction with the Angevin Kingdom, as well as with the Papacy (with the risk of stalling the Aragonese occupation of Sardinia). After the King of Aragon, it was Pope Clemente’s turn to ask Eleonora to convince Federico to make peace with Roberto of Anjou. In both cases, though, her conciliatory efforts didn’t work.

In 1321 she witnessed her son Pietro being associated to the throne and thus crowned in Palermo (“Anno domini millesimo tricentesimo vicesimo primo, dum Johannes Romanus Pontifex contra Fridericum Regem, & Siculos propter invasionem bonorum Ecclesiarum precipue fulminaret, Fridericus Rex primogenitum suum Petrum, convenientibus Siculis, coronavit in Regem, & patris obitum, inopinatum premetuens, & ut filius qui purus videbatur & simplex, ab adoloscentia regnare cum patre affuesceret patrisque regnando vestigiis inhereret […]” in Gregorio Rosario, Bibliotheca scriptorum ..., I, p. 482). Pietro’s coronation publicly violated the Treaty of Caltabellotta (as the Kingdom should have returned to the House of Anjou), causing the pursuing of warfare between Naples and Palermo. Once again Eleonora’s attempts at peace-making failed miserably, with her nephew, Carlo Duke of Calabria, refusing to even meet her in 1325, after he had successfully raided the outskirts of Messina.

The Queen didn’t have much luck in internal policy too as she failed to appease her husband and her protegé, Giovanni II Chiaramonte. After gravely wounding Count Francesco I Ventimiglia of Geraci (his brother-in-law and one of the King’s trustees), all that Eleonora could do was advise Chiaramonte to flee to avoid the death penalty.

Nevertheless, the Pope still hoped to use the Queen (who, at that time and alone in her Kingdom, was exempted from the Papal interdict) as mediator with her husband, promising to lift the excommunication in exchange for Federico’s backing down. Once again nothing happened.

On June 25th 1337 Federico III died near Paternò. He was buried in Catania since it was too hot for the body to be transported to Palermo (“Feretrum humeris nobiliores efferunt. Adsunt Regii filii, proceresque Regni. Exequias Regina, illustribus comitata matronis, prosequitur.” in Francesco Testa, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis, p.225). After the death of her husband, the now Dowager Queen turned to religion, following the example of those in her family who had consecrated themself to Christ (“At Heleonora certiorem fe de illa consolandi rationem inivit. Ipsa enim , ut Rex excessit e vita, ei, qui omnis consolationis fons est, fese in Virginum collegio Franciscanæ familiæ Catinæ devovit; in hoc Catharinan , & Margaritam filias imitata, quæ in ætatis flore, falsis terrestribus, contemptis bonis, Christ, cui fervire regnare est, in sacrarum Virginum Messanensi Collegio, de Basicò dicto, ejusdem Franciscanæ familiæ fese consecrarant; quod Collegium posteaquam Catharina fancte gubernavit, sanctitatis opinione commendata deceffit” in Francesco Testa, De vita..., p.226).

If Eleonora might have hoped to exert some kind of influence as many other Queen mothers did in the past and would do in the future over their weak-willed royal children, she would soon realize she had a powerful rival in the new Queen consort, her daughter-in-law, Elisabetta of Carinthia. Like Eleonora, the new Queen supported the Latin faction (a group of Sicilian noblemen who opposed the Aragonese rulership over Sicily, hoping the island would be returned under the influence of the Angevins instead). But, while Elisabetta had managed to raise the Palizzis to the highest positions at court, her mother-in-law still supported the Chiaramonte, making it possible for the exiled Giovanni II to return to Sicily, be pardoned by the King and see all his goods be returned. Soon though Chiaramonte resumed his personal feud against the Ventimiglia (also part of the Latin faction) and once again Eleonora's attempt to bring peace failed miserably. Only through Grand Justiciar Blasco II d'Alagona's intervetion, the crisis was averted.

In 1340, the Dowager Queen made a last attempt to appease the new Pope, Benedict XII. Unfortunately, the Sicilian envoys sent to Avignon to take an oath of vassalage (since Norman times Sicily theoretically belonged to the Papacy, who granted it to the Sovereigns who acted as Papal Legates) were treated roughly by the Pope, who declared Roberto of Anjou (Eleonora's brother) as Sicily's legitimate King.

Deeply distraught, the Dowager Queen resolved to definitely retire from public life. She spent what it remained on her life visiting the monastery of San Nicolo' d'Arena (Catania), joining the monks in their religious life. She died in one of the monastery's cells on August 10th 1341. Her body would be buried in the Church of San Francesco d'Assisi all'Immacolata (Catania), the construction of which she had personally promoted in 1329 to thank the Virgin Mary for protecting the city from one of many Mount Etna's eruptions.

Sources

AMARI MICHELE, La guerra del Vespro siciliano

CORRAO PIETRO, PIETRO II, re di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 83

DE COURCELLES JEAN BAPTISTE PIERRE JULLIEN, Histoire généalogique et héraldique des pairs de France: des grands dignitaires de la couronne, des principales familles nobles du royaume et des maisons princières de l'Europe, Vol. XI,

FODALE SALVATORE, Federico III d’Aragona, re di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 45

GREGORIO ROSARIO, Bibliotheca scriptorum qui res in Sicilia gestas sub Aragonum imperio retulere, I,

KIESEWETTER ANDREAS, ELEONORA d'Angiò, regina di Sicilia, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 42

de MAS LATRIE LOUIS, Histoire de l'île de Chypre sous le règne des princes de la maison de Lusignan. 3

MUNTANER RAMON, Crónica catalana

Sicily/naples: counts & kings

TESTA FRANCESCO, De vita, et rebus gestis Federici 2. Siciliæ Regis

#historicwomendaily#historical women#history#history of women#herstory#eleanor of naples#frederick iii of sicily#house of aragon and sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#myedit#historyedit

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

hii you should vote team wisdom :)

#do it FOR THE WOMEN!!!!!!!!!! also apologies if i got something wrong i dont know a lot about zelda yet!! :3#my art#sicily(3)#princess zelda#tloz#zelda tears of the kingdom#zelda#the legend of zelda#splatoon#splatoon 3#agent 3#captain 3#splatfest#power vs wisdom vs courage#humanized#inkling#splatoon oc#digital art#illustration#artists on tumblr

500 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matilda, Eleanor, and Joanna - retrospring request for the Angevin daughters

#Angevin empire#Plantagenets#Matilda of Saxony#Eleanor of England queen of Castile#Joanna of Sicily#12th century#medieval#medieval women#requests#my art

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fra balletten Valkyrien. Bjørn danser med elverpigerne. by Otto Bache

J.P.E. Hartmann's ballet Valkyrien (The Valkyrie) Act 3: Bjørn dances with the Greek girls, who offer him wine.

#otto bache#art#valkyrien#ballet#valkyrie#danish#denmark#norse mythology#bjorn#byzantine#sicily#wine#elf#elves#women#maidens#nordic#germanic#europe#european#dance#dancing#saga#j. p. e. hartmann#vikings#viking#mythology#saxo grammaticus#richard wagner#johan peter emilius hartmann

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

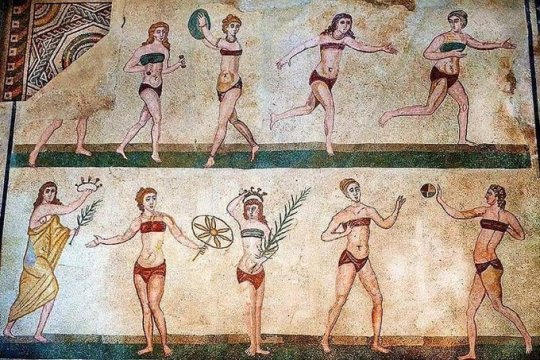

Ancient Roman Mosaic Reveals Women Wore Bikini

It is believed that the bikini was a 20th century invention, but an ancient mosaic reveals women in Rome wore it while playing sports.

The Villa Romana del Casale, located in Sicily, dates back to the early fourth century AD. Among the ruins, archeologists have discovered one of the largest collections of ancient Roman mosaics.

All of them are surprisingly well preserved. One of the rooms of the villa is called Sala delle Dieci Ragazze, which can be translated as “Room of the Ten Girls” – based on the number of those depicted in the floor mosaic.

Eight of them wear what in the modern world would be called a two-piece bikini, another woman wears a yellow translucent dress, while the image of the only one figure has not survived to this day.

The bottom of this set of clothing looks like a terracotta-colored band made of fabric or leather, similar to men’s loincloths. As for the top, it is reminiscent of a modern strapless breastband. Such chest harnesses also have their own history and have been known since the times of Ancient Greece. It is believed that most often the material for this was linen. This piece of clothing was intended for women leading an active lifestyle and partaking in physical exercise.

Thus, it can be assumed that in ancient times such a bikini was not used for swimming, but rather for sports. This is exactly what all the women depicted in the mosaic are doing. Some of them run, and others throw a discus or hold weights in their hands.

Two women are playing with a ball together. Researchers speculate that this could be some kind of early form of volleyball. In general, ball games are considered one of the most ancient. Their mentions can be found in Homer’s Odyssey. One of the girls, standing in the center, holds a palm branch in one hand and is about to place a victory crown on her head – probably a reward for the best performance. All the women look athletic and have noticeable muscle outlines on their arms and legs.

When it comes to sports, women in ancient Rome were permitted to practice physical forms of exercise, but they faced certain restrictions within a patriarchal society. They were not allowed to take part in competitions with men, and public female nudity was frowned upon. Therefore, a kind of prototype of the modern bikini made it possible to play sports without much inconvenience.

By Maria Rybachuk.

#Ancient Roman Mosaic Reveals Women Wore Bikini#Roman Bikini Girls#Room of the Ten Girls#mosaic#roman mosaic#The Villa Romana del Casale#sicily italy#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

put these two in a room together

#shiv roy#siobhan roy#harper spiller#aubrey plaza#sarah snook#succession#succession hbo#hbo succession#the white lotus sicily#the white lotus#the white lotus s2#the white lotus season 2#women on the verge of a nervous breakdown

429 notes

·

View notes

Text

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

🎞️: The Godfather (1972) + 🎬: Frances Ford Coppola

#film#cinema#The Godfather#Italians#the mob#firearms#women#omega#our lady omega#Sicily#i know right?

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sicily Rose

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"I am Manfredi, grandson to the Queen

Costanza: whence I pray thee, when return'd,

To my fair daughter go, the parent glad

Of Aragonia and Sicilia's pride;

And of the truth inform her, if of me

Aught else be told. [...]

Look therefore if thou canst advance my bliss;

Revealing to my good Costanza, how

Thou hast beheld me, and beside the terms

Laid on me of that interdict; for here

By means of those below much profit comes.

Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Purgatory, III, 112-117 & 141-145

Costanza was born around 1249 to Manfredi of Sicily and his first wife Beatrice of Savoy ("et filiam suam Constantiam, quam ex prima consorte sua Beatrice filiam quondam A. Comitis Sabaudiae"). The exact date is unknown, but historian Saba Malaspina attests that when she was born, her grandfather was still alive (“imperatore vivente"). As for the place, it might have been one of the Apulian castles where the Emperor settled down in the last period of his life.

Her wet nurse was Bella d’Amico, mother of admiral Roger of Lauria. Bella, while she was alive, never parted from Costanza, acting like a mother and confidante, especially since Beatrice of Savoy, Manfredi’s first wife, had died when her daughter was just months old.

Nothing is known about Costanza’s childhood. She’s first mentioned when Berthold von Hohenburg asked for her hand on behalf of his nephew Januarius, son of his brother Diepold VIII. Berthold had married Isotta Lancia, cousin of Manfredi’s mother Bianca, and certainly intended to deepen his relationship with the Hohenstaufen’s family. Manfredi, on the other hand, was strenghtening his position (to the point he would be crowned on August 1258 King of Sicily, despite the true heir, his nephew Corradino was still very much alive, although far away in Germany) and so he could afford to reject this marriage proposal.

From a princess of low importance (despite the pretentious name which honored her great-grandmother Costanza I), Costanza soon became a valuable asset and, until Manfredi’s second marriage to Epirote princess Elena Angelina Doukaina, her father’s heir. The Sicilian King then started looking for an important match for his daughter, and ended up selecting Peter, son of Aragonese King James I.

Marriage agreements required that Manfredi supplied his daughter of a dowry of 50000 golden ounces (worth in gold, silver and jewels). On the other hand, the Aragonese crown committed to return the dowry to her family if Costanza were to die without heirs. She would also act as regent for her children (until they were 20 years old) in case Peter were to die before her. In addition, the Sicilian princess was given personal ownership of the city of Girona and the castle of Cotlliure.

Still, the future union presented some problems. First of all, that 50000 golden ounces dowry was indeed a large amount. Manfredi had an hard time collecting it (he had to increase taxes and that spread discontent among the population) and a lot of time passed before the Aragonese crown could collect it (alongside with the bride). The Papacy was obviously against this marriage, and Urban IV asked James I to give up to this union to avoid disgracing his House. Furthermore, in order to save the plans of the future marriage between his daughter Isabella and the heir to the French throne, James had to promise King Louis IX to not support Manfredi in his fight against the Papacy, as well as not helping Provençal rebel Bonifaci VI de Castellana against Charles of Anjou (the King’s younger brother).

Despite all the external pressure, James didn’t give up to the Sicilian match and on July 13th 1262, Peter and Costanza got married in the church of Notre-Dame des Tables (Montpellier). The difference between the lavish Hohenstaufen court and the more simple Aragonese one was huge (“And the said King Manfred lived more magnificently that any lord in the world, and with greater doings, and with greater expenditure”), but thanks to the accounting records of the time, we know that James and Peter tried their best to meet Costanza’s need, purchasing large amounts of luxury items. Since the incomes deriving from Girona and Cotlliure weren’t enough, she was given an annual pension worthy of 30000 Real de Valencia (a type of billon coin) which also soon wasn’t enough to cover the expenses.

Following the death of Manfredi in the Battle of Tagliacozzo (1266) against Charles of Anjou, many of his former supporters (or simply people linked to him, like the former Nicaean Empress as well as his sister Costanza) fled the Kingdom of Sicily and took refuge in Aragon. The death of Corradino (executed in Naples in 1268 by order of Charles after the Battle of Benevento) and the fact that Manfredi’s sons from Helena Doukaina were just children and in French hands (they will die in captivity years later), made Costanza the only legitimate heir to the Sicilian crown. Starting this moment Costanza started being referred as queen (not infanta or madama) in the documents of the Aragonese Chancellery.

In 1276 James I died, and so Peter was crowned king of Aragon. In the meantime, Costanza had already given birth in 1265 (November 4th) to the firstborn and heir, Alfonso. Followed by another male, James (April 10th 1267), and then Isabella, future Queen consort of Portugal (1271), Frederick (December 13th 1272), Yolanda (1273) and finally Peter (1275). According to historian Muntaner, although it wasn’t a love marriage, Peter and Costanza came to care for each a lot and “there were never was so great love between husband and wife as there was between them, and always had been”.

On Easter 1282, Sicilians started their revolt against the French rule, starting the so called Sicilian Vespers. Peter was quick to reclaim the crown of Sicily and Apulia on behalf of his wife. To the eyes of many Sicilian nobles the King of Aragon could be considered their legitimated master due his marriage to Queen Costanza (”nostre natural senyor, per raho de la regina e de sos fills” ). Before leaving headed for Africa (from where he would launch his invasion of Sicily), Peter named Costanza and their son Alfonso regents of the Kingdom of Aragon during his absence. As soon as he took possession of the island, Peter asked his wife and their children James, Frederick and Yolanda to join him. When the Queen arrived in Trapani in the spring of 1283, she received a warm welcome and was saluted by the people as their natural leader (”cela qui era lur dona natural”; Bernat Desclot, Llibre del rei en Pere d'Aragó e dels seus antecessors passats, ch. 103).

It is around this period that her strained relationship with lady-in-waiting and de facto second lady of the Island, Macalda di Scaletta (wife of Alaimo da Lentini, Grand Justiciar of the Kingdom of Sicily), was born. Macalda, who is described by historical sources as an ambitious and greedy woman, had tried to seduce Peter of Aragon, but without success. Since the King had declared himself devoted to his wife, the Sicilian baroness developed a burning hate towards her rival, the Queen.

In Messina, Costanza could finally embrance her husband again, but their meeting only lasted three days and it was their last. The King named his wife Regent of the Kingdom of Sicily (“Quant lo rey hac estat ab sa muller e ab sos infants en la ciutat de Mecina, e hac stablit sos balles e sos vicaris per tota Cecilia, si los feu comandament que tots fessen lo manament de la reyna e de son fill En Jaume, axi com perell, e comana la reyna als homens de Cecilia e de Mecina, e sos fills”) and returned to Aragon as his rival, Charles of Anjou, had proposed a trial by combat (who would never take take place) to be ideally fought in Bordeaux to decide the fate of the contended Kingdom. Peter died two years later in Villafranca del Penedès (Catalonia), on November 11th 1285.

Before leaving Sicily, Peter had declared that the Kingdom wouldn’t be merged into the Aragonese-Catalan territories, mantaining his autonomy, and that in thet future the succession of the two reigns would be handled separately, specifically with the Sicilian throne bequeated to the second son (at that time, James, already named Lieutenant of the Realm).

With Peter dead, Costanza didn’t choose to rule over Sicily by herself despite being its titular queen, but, as it had already been decided, relinquished her rights to her second son James (although she would keep managing the island on his behalf), while Alfonso succeeded his father. In accord to the pre-nuptial arrangements, the Dowager Queen supported her teen son in the matter of ruling the Kingdoms he had inherited.

In 1284, Costanza’s milk brother, Roger of Lauria carried out a successful expedition in the Gulf of Naples. The admiral captured Charles of Salerno, the Angevin heir, and took him in Messina, where he was saved by the angry mob thanks to the intervention of the Dowager Queen. During the same raid, Lauria had freed Princess Beatrice of Hohenstaufen, Costanza’s younger half-sister. The Queen soon put her unfortunate sister under her protection, arranging Beatrice’s marriage with Costanza’s half-nephew, Manfredo IV Marquis of Saluzzo. The wedding was celebrated in October 1286 in Messina, and during the celebration the Princess had to give up on her rights to the Sicilian throne.

In 1290 she deployed troops to defend the city of Acre, but given the excommunication of Pope Martin IV against Peter III of Aragon and the Sicilian people, those troops were sent back. The following year, 1291, Acre would be conquered by Mamluk forces.

Also that year, Alfonso III died heirless. James succeeded him as King of Aragon, Valencia and Majorca, Count of Roussillon, Cerdanya and Barcelona, and, in normal circumstances, his brother Frederick would have inherited the Sicilian Crown, but James had other ideas. The new King kept Sicily for himself, naming Frederick Lieutenant of the Realm. The dispossessed Prince then left the Kingdom headed to Sicily, where he joined his mother Costanza.

Her son’s death represented a turning point in her life. Although already a pious woman, she started pondering about a future in the cloister and retired in a Clarisse nunnery she had personally founded in Messina.

In 1295, James signed the Treaty of Anagni, an accord signed by Boniface VIII, James II of Aragon, James II of Majorca, Charles II of Anjou and Philip IV of France, which should have put to an end to the Vespers War. As part of the terms, the King of Aragon had to return the island of Sicily to the Pope (let’s remember the fact that officially, since Norman times, the Kingdom of Sicily was actually one of the Papacy’s many fiefs, and that its lords were just lieutenants), who would in turn give it to Charles of Anjou, in exchange for the annulment of the excommunication weighing over him and the concession of the licentia invadendi (the permission to invade) concerning the islands of Sardinia and Corsica. The treaty required moreover a double dinastic union, James would have married Princess Blanche of Anjou, while her brother Robert was wed to James’ sister Yolanda.

There was someone in particular, though, who wasn’t happy about this settlements. Backed up by the Sicilian population who refused to return under French domination, Infante Frederick was crowned King of Sicily in Palermo on March 25th 1296, de facto nullifyng any attempt to stop the war.

This had a huge impact in his mother’s life. Unlike her son, Costanza had always recognized the Papal authority. By not accepting the treaty’s terms, Frederick had in fact rebelled against the Pope (not mentioning his own brother). Costanza chose then not to support him and, because of this, she had to leave Sicily since, as Papal emissaries put it, if she stayed she could be considered an accomplice (“E madona la regina Costança fo absolta per lo Papa, é tots aquells qui eren de sa companyia , si que tots dies oya missa; que axi ho hach a fer lo Papa, per convinença a les paus quel senyor rey Darago feu ab ell. Per que madona la regina parti de Sicilia ab deu galees , e anassen en Roma per pelegrinatge” in Crónica de Ramon Muntaner, ch CLXXXV).

Together with her longtime supporters, Giovanni da Procida and Roger of Lauria, in february 1297, she traveled to Rome where the Pope had promised to economically support her staying in Rome (although apparently it was a short-lived promise) and where she witnessed her daughter Yolanda’s marriage to Robert of Anjou. In 1299 the Dowager Queen returned to Catalonia and died in Barcelona on April 8th 1302 (“Non sine cordis amaritudine vobis presentibus intimamus quod die Veneris Sancta, quasi in media nocte, serenissima et karissima domina et mater nostra domina Constancia, fidelis recordacionis Aragonum regina, diem clausit extremum, ex quo tanto nos pungit doloris ictus acerbus quanto per eius obitum sentimus nos tante matris solacio destitutos.” in La muerte en la Casa Real de Aragón..., p.20).

Aside from many donations to various religious houses, in her will (dated february 1st 1299) Queen Costanza would include a small bequest in favor of her son Frederick with the condition he had to make peace with the Pope, observing thus the terms of the Treaty of Anagni.

She was buried wearing the Franciscan habit in the convent of St. Francis in Barcelona (“E a Barcelona ella fina , e lexas a la casa dels frares menors, ab son fill lo rey Nanfos, e muri menoreta vestida ” Crónica de Ramon Muntaner, ch CLXXXV). In 1852 her remains would be moved to Barcelona Cathedral by order of Queen Isabella II of Spain.

Sources

Claramunt Rodríguez Salvador, Alfonso III de Aragón

Corrao Pietro, PIETRO I di Sicilia, III d'Aragona in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 83

Desclot Bernat, Crónica

Ferrer Mallol María Teresa, Constanza de Sicilia

Hinojosa Montalvo José, Jaime II

La Mantia Giuseppe, FEDERICO II d'Aragona, re di Sicilia in Enciclopedia Italiana

La muerte en la Casa Real de Aragón Cartas de condolencia y anunciadoras de fallecimientos (siglos XIII al XVI), ARCHIVO DE LA CORONA DE ARAGÓN

Malaspina Saba, Rerum Sicularum

Muntaner Ramon, Crónica / translation by Lady Goodenough

Sicily/Naples: Counts & Kings

Walter Ingeborg, COSTANZA di Svevia, regina d'Aragona e di Sicilia in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 30

#historicwomendaily#history#women#history of women#historical women#costanza ii#House of Hohenstaufen#house of aragon and sicily#peter iii of aragon#norman swabian sicily#aragonese-spanish sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#vespri siciliani#myedit#historyedit

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great ISIS, also known as Egyptian Juno, sister and wife of Osiris, was a great name among the Egyptians. An epitaph on a column attests to this, which was once carved in these words:

I am Isis, queen of Egypt, educated by Mercury.

What I established by law, no-one will undo.

I am the wife of Osiris.

I am the first inventor of crops.

I am the mother of Horus the king.

I am shining from the star Sirius.

I founded the city of Bubastis.

Rejoice, rejoice O Egypt, who was nursed by me.

He who wants more should read the first and second books of Diodorus of Sicily, On the Legendary Deeds of the Ancients.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

@dilaambeauty #

#luxuryliving#blackwomeinluxury#black girl luxury#black women in luxury#softlifeaesthetic#italian lifestyle#luxury vacation#finedining#dilaambeauty#luxe aesthetic#sicily italy#blacktraveler#summer moodboard#grand hôtel Timeo

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sicilian hydria

* 320-310 BCE

* Lipari Painter

* British Museum

London, July 2022

#hydria#sicily#4th century BCE#ancient#Greek#art#vase#Lipari painter#Greek women#British Museum#my photo

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maryse wears the Denim Cape from Emilio Pucci ($1,680), Large Sicily Handbag in Fuchsia from Dolce + Gabanna ($2,095) and Lupita Denim Mule Sandals from Amina Muaddi ($710)

#maryse#maryse wwe#maryse mizanin#denim cape#cape#capes#emilio pucci#Large Sicily Handbag#handbag#handbags#dolce gabbana#Lupita Denim Mule Sandals#sandal#sandals#amina muaddi#women of wrestling fashion#wwe

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sicilia

#black and white#wordpress#women outdoors#people#bianco e nero#sicilienne#sicily italy#bw#nature#beach

3 notes

·

View notes