Text

If they were the only two people in a world without time, he would take Jingyan to Langzhou. He would let Jingyan carry him to the lake, the water so clear you can see your own memories on the bottom. He would tell Jingyan how he likes to be touched. He would let Jingyan show him. At night, when fireflies stream out of summer grass, he would wrap his tattered pennant of a body around Jingyan’s. He would cradle Jingyan’s hands in his own and say, this is all of me now, unarmed, unbound, nothing here but the remains of our long-lost promise to see every mountain and water together, and for thirteen years the duty of righting an impossible wrong kept Mei Changsu alive but it was the thought of your impossible hands that kept Lin Shu alive inside him and I, in this nonexistent time and place, under these dim winged lights, am no longer cursed with a detached heart and false tongue when I chant Jingyan, Jingyan, Jingyan…

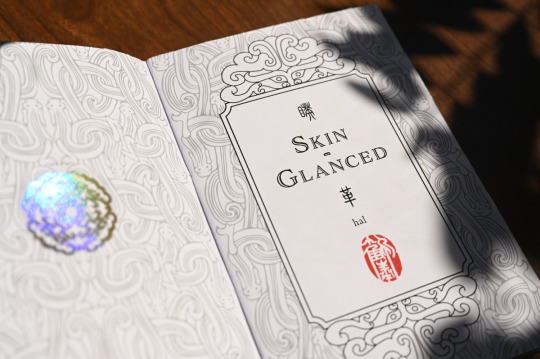

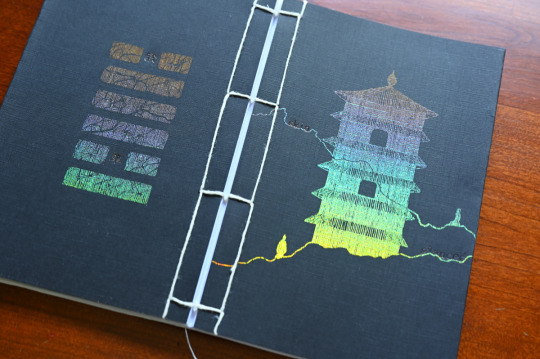

skin-glanced, in the flesh | 《睽革》肉体版 faux four hole bare spine sewn binding | 伪四眼裸脊线装 104 pages | 104页

artist name seal by 忍霖 (@sealrendering)

#book design#sound warning#maybe the real treasure was the rainbow tower we climbed along the way#先生与我,如同一人

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

(the post editor malfunctioned and after a series of unfortunate events the original ask post is gone, so I had to make this screenshot mockup of the ask, sorry)

Thank you for prodding me to finish up a draft that's been sitting there for an inexplicably long time.

I will divide puns into exact homophones, which are pronounced exactly the same, and near homophones, which consist of the same phonemes with different tones. Though exact homophones are much punnier in speech, Internet jokes rely heavily upon text input and most people use phonetic-based Chinese input systems, meaning their autocompletes will often suggest near homophones and people will use them if they're funny enough.

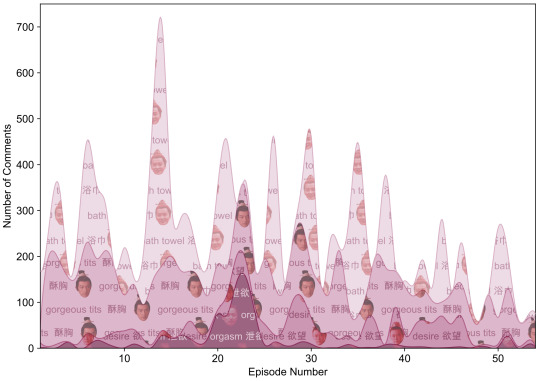

To make this slightly statistically sound and not just me making up random puns, I grabbed 700k viewer comments from the years NiF was available on Youku, 2015 to 2020 (courtesy of danmu box). These danmu/弹幕 comments are timed to a particular moment in the show so they splash across the screen while you watch.

Let's start with the heavy hitters:

Xie Yu/谢玉 is an exact homophone of xièyù/泄欲, literally discharging desire, which means satisfying one’s lust or orgasming. Xie Yu's name occurs 5000+ times in the comments versus almost 900 orgasms.

Prince Yu/誉王 is an exact homophone of yùwáng/欲王, meaning prince of lust, and a near homophone, of yùwàng/欲望, which means desire (or the chaotic evil penis). The latter is far more likely to be autocompleted and shows up 1500+ times versus 200+ for the prince of lust.

Yùjīn/豫津 is a near homophone of yùjìn, 欲禁, or forbidden lust/abstinence. Because bath towel/浴巾 is an exact homophone and again far more likely to come up first in autocomplete, people overwhelmingly refer to him as the towel. In the comments, bath towel is used nearly 7000 times, 10x more frequently than his actual name, which is made up of two not-super-common characters.

Mei Changsu is often addressed as Su-xiong/苏兄 by Jingrui and Yujin in canon, which is an exact homophone of sūxiōng/酥胸, a literary term for supple and beautiful breasts that might have the same old-fashioned connotation as heaving bosom does in English. I'm going to call him gorgeous tits because he does bear a striking resemblance to the azure tit:

I've seen Chinese MCS fans note this resemblance before, but these birds don't have titillating names in Chinese so you can have this bonus joke for English speakers. Anyways, gorgeous tits are invoked in nearly 6000 comments versus almost 1200 for Su-xiong itself.

Now you can enjoy one of the comments from the above screenshot exclaiming over these names:

浴巾裹着酥胸,泄欲,这都什么什么 a bath towel (yujin) wrapped around gorgeous tits (su-xiong), orgasming (xie yu), what is all this

And the following off-color joke retold many times throughout the episodes:

Why is Mei Changsu called Su-xiong and not Mei-xiong? Because he has gorgeous tits, not tiny ones (Méi-xiōng/梅兄 is an exact homophone of flat-chested/没胸).

Here are some rarer-but-still-good puns:

Gōng Yǔ/宫羽 is a near homophone of gòngyù/共浴, bathing together (cue viewer comments about how she and bath towel belong with each other).

Níhuáng/霓凰 is a near homophone of nǐhuáng/你黄, slang meaning you’re perverted.

The emperor lives in Yǎngjū Hall/养居殿, a near homophone of penis hall since yángjù/阳具 is the yang implement, though it's most popularly punned with pigpen (I wrote about this here if you scroll to the end).

The travelogue Mei Changsu wrote annotations in, 翔地记, is an exact homophone of xiángdìjì/降帝记, or records of subduing the emperor (which I can only interpret as MCS’s Dom Diaries on how to conquer Jingyan).

To conclude, here’s a stacked area chart of the four horsemen of punny NiF names and how often they're spammed:

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

134 notes

·

View notes

Note

First of all thank you so much for all the NiF archive, they're like a treasure for me! <3 The comics are unexpectedly fascinated, I'm reading 奇迹琰琰收藏卡 Yanyan Trading Cards by SemiMage and part 06 is deleted :( I tried to search for it, seems like the artist's Weibo may have it, but it's been too long and I don't have an account to scroll back that far :( Do you happen to have this part in your archive somehow? If it's possible I would really like to read it, thank you so much!

Really glad you asked, because I did save this miraculous series but didn't upload it for whatever reason...I've added a SemiMage folder to the archive, and do let me know if you have any other requests. Enjoy <3

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m so glad I found your blog. All your insights into NiF and Mandarin translation are keeping me well fed! Thanks for your hard work.

A belated thank you for your lovely note!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

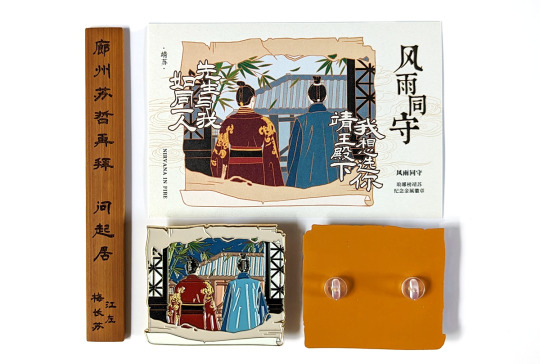

The trouble with collecting merch is it’s difficult to stop once you start. This Jingsu enamel pin is by the prolific 长风万里, who is responsible for some of the most iconic NiF pins (check out the weidian store for a partial selection). Like many fan-made pins, it’s a re-rendering of a scene from canon, in this case episode 52 [x], where Jingsu look on as thunder and wind portend the storm brewing on the horizon after Princess Liyang has agreed to present Xie Yu’s confessed crimes at the Emperor’s banquet.

The pin emphasizes the storm in both design (bamboo leaves scattering in the wind) and name: 风雨同守, loosely enduring the tempest together. As for why the image has been transposed onto a tattered scroll, the pin maker said the inspiration came from rubbings/拓印 and elaborated some more:

Personally, I think of this as an excavated artwork (with the surface damaged in its old age) that was created out of Jingyan’s longing. As if Jingsu actually existed in history and will live on for a long, long time. 我自己把这个当做是一件出土的画作(年岁久远画面有所破损),是景琰怀念所做。就好像历史上真有他们的存在,靖苏真的来日方长。

Historically, rubbings not only create an impression of existing artwork but are themselves artworks that take skill and patience. The typical process starts with adhering paper to a stone carving, then ink is dabbed to the paper such that the flat surface takes on the color of the ink while carved areas remain white (here’s a process video). Collecting rubbings was a popular pastime of the literati, and rubbings of good calligraphy were especially in demand for study and appreciation, serving a similar purpose to block printing in allowing many people to see replicas of an original. The originals may have also come from a non-stone medium: some artworks originally on paper or fabric were replicated onto stone so that rubbings could be made and collected [x]. Nowadays, ancient rubbings are valuable artifacts, especially in cases where the carving has been lost.

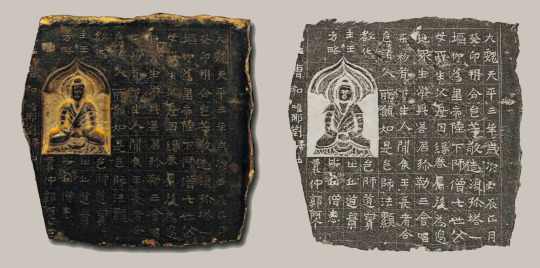

The rubbing influence is very clear in the second version of the pin, here juxtaposed against one of its inspirations:

Though the text on the right rubbing says it’s from the Tianping Era of Eastern Wei, Year 2/魏天平二年 (535 CE), which is contemporaneous with the Liang dynasty that loosely inspired the fictional NiF Liang, I couldn’t find an actual historical artwork corresponding to this rubbing, and the mass antique market is flooded with fabrications (it’s also thoroughly possible I simply failed to find the original). But here’s a real fragment of a stone Buddhist votive tablet and its rubbing that’s now at the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong [x]:

The text says that this was made in Tianping Era, Year 3, one year after the one above, and describes the building of a Buddhist pagoda in offering, which was a common practice at the time. This monochromatic rubbing style was also quite typical; though both black ink and red ink (cinnabar-based) rubbings existed separately, they were not really seen in combination in a single rubbing until much later. What is believed to be the only surviving book of bicolor rubbings before the modern era was made in the Qing dynasty around the 1800s and was itself a copy of a lost multicolor work from the same dynasty [x].

In this context of transference of art and meaning between mediums, it’s all too easy to imagine a backstory for this Jingsu scroll: first there was a stone carving, close enough to the actual scene that the artist must have worked from Jingyan’s memory of that day. Instead of the more common approach of carving the outline or the background, the artist decided to carve the foreground so the figures were sunken into the stone. And later, a rubbing was made and mounted onto a scroll, buried and excavated, then finally rendered from fiction to reality in the form of an enamel pin. Each creation is an act of remembering and reinventing, of placing yourself in the observer’s shoes, of stoking the flames of the original story—the fire burns on through metaphorical wood replaced over the centuries, its appearance ever-changing, its core not forgotten.

That’s enough of reading too much into things—I also like the pin on its own. One thing that 长风万里 does well is not just sell pins but also communicate the entire behind-the-scenes process with the QQ group, which is several months’ worth of iterations that I find at least as interesting as the final product. For this pin, you can trace through chat logs how the pin evolved all the way from the original concept sketch to the pieces of metal that fit in your hand (thanks to 长风万里 for letting me share the draft versions here):

Once the pin maker comes up with an idea and decides to go for it, the initial sketch is given to the commissioned artist (this pin was drawn by Forwrite, on weibo and lofter) along with reference images. The artist turns these into a line drawing following the design rules of enamel pins (each block of solid color should be fully enclosed by lines, for example). Some artists will color in the line art while other pin creators commission only the line art and fill in the colors themselves. The final colors are limited to the available palette at the factory chosen to make the pins, and once the color vector art is handed to the pin factory along with instructions on detailing and finishes, the physical manufacturing process begins in earnest (this could be the subject of its own long post).

You may have noticed that there are some color changes from the vector design to the physical pins, most notably the sky in the top pin. This came about as a serendipitous accident where the factory colored the sky of the sample pin dark blue instead of the requested sunset yellow, but the pin buyers active in the group chat liked the dark blue enough that it was kept as the final color. The light grayish blue variant ended up being chosen for the backing card/背卡 instead:

Though backing cards are nominally named for their purpose in supporting the pin, practically no one sticks their pins through these cards in Chinese fandom; instead, collectors generally buy cases and books to keep each piece in pristine condition. And so unlike utilitarian cards that are meant to serve as a background to the pin, fully designed backing cards that stand on their own are very much a thing. The card also adds back in the iconic Jingsu lines that were in the original concept sketch, I want to choose you, Your Highness Prince Jing/我想选你靖王殿下 from Mei Changsu and Sir and I are as one person/先生与我如同一人 from Jingyan.

And now for the last part of the merch package that comes with the pin: the wooden piece on the left is an inscribed bamboo name slip/名刺 meant to resemble what MCS might have presented Jingyan when he visited his manor in episode 9 [x]. This was a preorder bonus to encourage buyers to get on board early, since the upfront costs to commission the artist and get a sample made at the factory are a significant portion of the overall costs (if not enough people preorder, the pin is canceled and the payment refunded, and the pin maker has to take the loss of at least the artist’s fees).

Name slips were the ancient analogs to modern business cards and an important tool of connection building in the ancient bureaucracy. The tradition of presenting a slip before you visit someone’s residence, especially if you’re lower in status than the person you’re visiting, persisted for many dynasties while the form of the slip evolved over time. Even though the visitation slip in canon appeared to be a bound paper booklet, folded books wouldn’t appear until the Tang dynasty—though paper was invented in the Han dynasty, it took time for the manufacturing process to improve sufficiently for a fundamental shift in writing mediums. Bamboo slips were what they would have used in the real Liang dynasty (plus, the modern-day replica is objectively great merch that can be used as a bookmark/fidget stick/cosplay prop/whatever else you can think of).

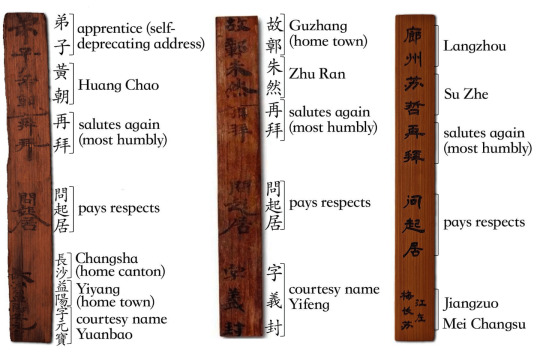

Slips from around the NiF time period generally stated some combination of your given name/名, your courtesy name/字, the region you’re from, and some boilerplate deferential language. Here are two real ones from Huang Chao/黄朝 and Zhu Ran/朱然 of the Three Kingdoms period next to MCS’s, with the meaning of some phrases listed in parentheses after the literal translation (using two of MCS’s names is a good solution for the lack of courtesy names in canon):

To balance out all the white background product photography, I’ll close with some texture shots:

#cost for everything was ¥90 or about $13#overseas shipping not included#先生与我,如同一人#chinese fandom#nirvana in fire#琅琊榜#merch review#long post

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

what does AFD mean when someone says they have uploaded the rest on AFD?

Assuming you’re talking about Chinese fandom lingo, AFD refers to 爱发电/afdian.net, where many writers post their work censored by other platforms because of AFD’s laxer rules and the option to require paid memberships for content (like Patreon). If the creator doesn’t specify where to find them on AFD, you can try going to afdian.net/a/[their username on other platforms].

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Years customs: family feast, offering to ancestors, red envelopes, fireworks, scheming

过年习俗:团圆饭、祭祖、红包、烟火、阴谋

272 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your blog is a treasure and a masterpiece. I'm learning so much about NIF, and this, 7 years too late..but better late than never I guess. Thank you very much.

Thank you, thank you! As Mr. Waited-12-Years might say, it's never too late.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

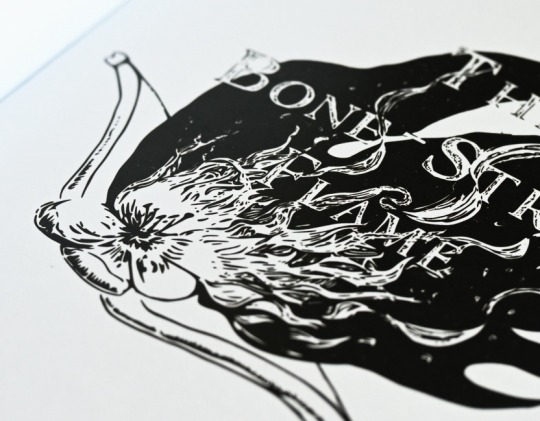

As he lay down at the site of his every nightmare, he decided what he missed the most was waking to Jingyan’s steady breaths and arms.

After the coronation, the new Emperor readily granted Minister Su’s request to spend the rest of his numbered days at the northern border. He swallowed the herb meant for fifteen years ago, said farewell to the few still left, swung the reins toward the dirt road by the pavilion and never looked back.

Who would have thought Jingyan would go before him?

He should know by now fate did not grant favors. But this wound was fresh, and he was surprised he could still feel. His old life—petitions and protocol, ambitious plans half done—bled away in trickles as he rode north, and by the time he was past the last Liang village, he had thoroughly let go of his worries for the country and thought only of holding and being held.

New habits formed in the gashing void. Every time his mind circled back to Jingyan, he rubbed the two lengths of hair looped tight around his finger and each other. The late Emperor, too ill to speak by then, had plucked the grayer strand from his own pillow and dropped it on his palm.

When the route became too steep for his living companion, he found a fallen branch Jingyan would have liked and climbed Meiling’s ridges for the last time. He could see everything from here, and distance was no more.

They say mountains are for the benevolent and waters are for the intelligent, Jingyan once said, but I am neither, and I choose—

He gripped his stick and felt Jingyan squeezing his hand back harder.

#mei changsu#结发为夫夫#先生与我,如同一人#I blame wk not being in more guzhuang for me killing Jingyan#cw death#thanks to a special 太太 for inspo

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those asking about where to buy this:

I got mine from a publisher on Shopee Taiwan/虾皮, who still has a few copies left. If you don’t live in Taiwan or know someone who does, you’ll have to go through a proxy. I used EZSTAR, which doesn't have the fanciest website, but the process went smoothly.

And FYI, my book didn’t come with the bonus preorder postcards from the first printing:

If you really want these, the other alternative is to look for copies on the secondhand app Xianyu/闲鱼, where listings like this one (I recommend opening the link on mobile) occasionally pop up. Both Shopee and Xianyu have a good selection of other NiF fanbooks and merchandise, too. With Xianyu, if you don’t have a mainland Chinese address to ship to, you probably also have to use a proxy since a lot of sellers don't want to bother with international shipping. There are tons of mainland proxies—Superbuy is one I’ve used before, and it offers both parcel forwarding and end-to-end buy it for you + ship it to you service.

It should go without saying that these are just suggestions, I’m definitely not paid to mention these services and can’t guarantee their quality, etc. Happy shopping.

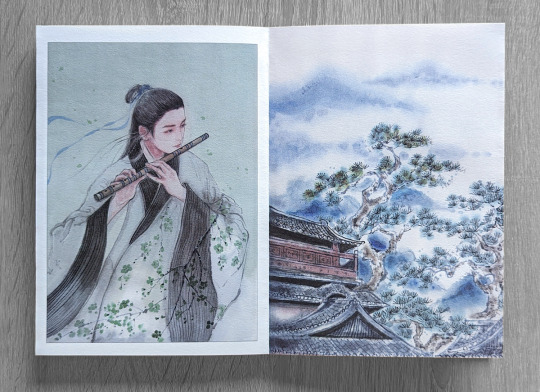

Fanbook Review: 《梅岭千秋》 by 壹染

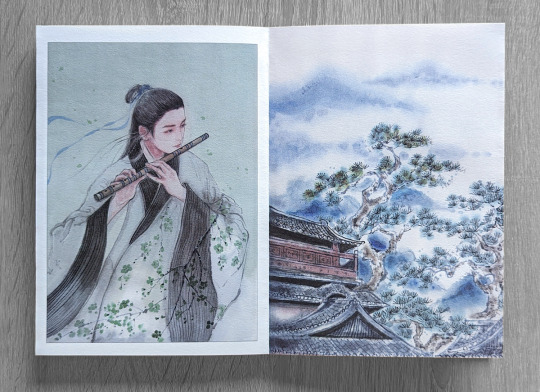

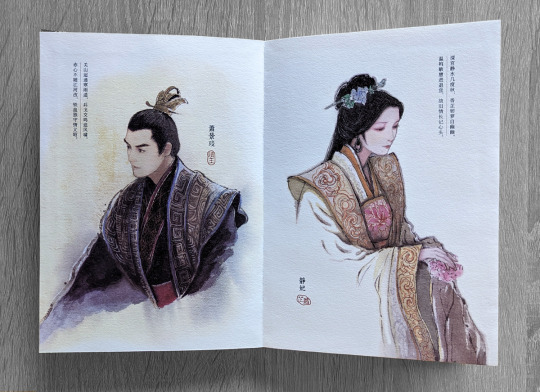

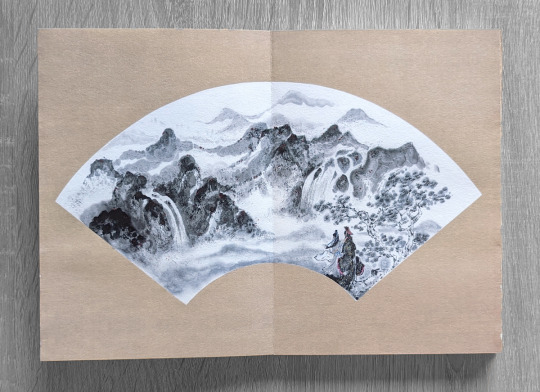

《梅岭千秋》 (roughly Meiling Undying) is a 2016 fanbook with art by Yiran/壹染 and published by 溯年组, depicting scenes and characters from Nirvana in Fire. I had to get my hands on a copy after falling in love with the art.

Yiran paints with ink brushes and watercolor on xuan paper/宣纸, a famous traditional Chinese paper made from the qingtan/青檀 tree especially suitable for calligraphy and painting. Xuan paper is divided into raw/生宣 and processed/熟宣 types, the former more absorbent with a tendency for ink to run free, and the latter processed with alum to be more controllable for precision ink work (the two types of traditional painting, evocative xieyi/写意 and realistic gongbi/工笔, are often split along raw and processed xuan in their choice of medium).

Raw xuan is particularly unforgiving to beginners, but Yiran is a master of her craft, able to achieve both precise lines and textures as well as the misty landscapes so characteristic of Chinese watercolor on this paper (see her Lofter for her process and more art). She often paints an entire series of pieces on a traditional accordion booklet/经折装, a single long sheet of paper folded on itself many times, as she did for this project (photos from her Weibo, which also has more art):

The publisher took care to replicate the original booklet of pieces as closely as possible in the final product. Beneath the outer paper jacket is a cover made of woven Song brocade/宋锦, with 38 accordion-folded A5 pages inside. The pages are textured imitation xuan paper, printed with a lacquered black ink that glows under the light:

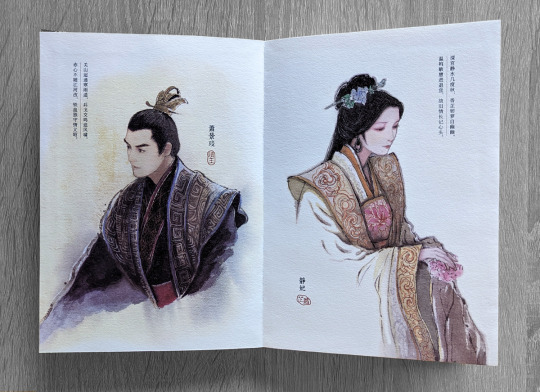

One side of the folded pages is mostly landscapes and scenes inspired by canon: Mei Changsu and Lin Chen in Jiangzuo beside flowers in bloom, an all-smiles Lin Shu embracing Jingyan in the before times. The other is a series of individual character portraits rendered with their attire from the show, their faces referencing the actors’s features but not overly imitative. There’s something revelatory in the way she paints a dreamy, ephemeral scene in one panel and then renders Jingyan’s robes with dramatic, almost impasto-like textures:

Each portrait is also paired with a poem written by 海月. Jingyan’s is

关山诏递寒雨遥,兵戈交鸣追风啸。 赤心不随江河改,铁血独守情义昭。

A possible translation:

Drifting bitter rain in mountains edict-sent, weapons clash as galloping horses scream. A pure heart enduring through shifting tides, alone in his courage, loyalty brought to light at last.

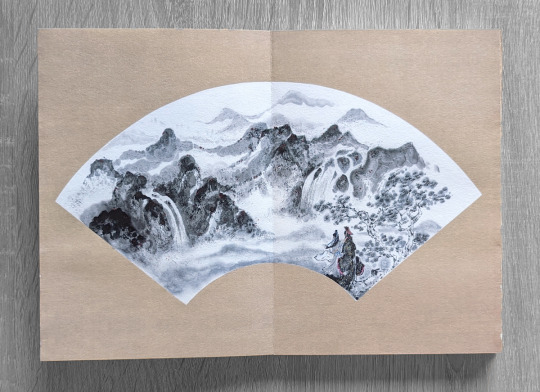

I’ll end with my favorite piece, Chief Mei and His Majesty beholding their mountains and waters:

145 notes

·

View notes

Photo

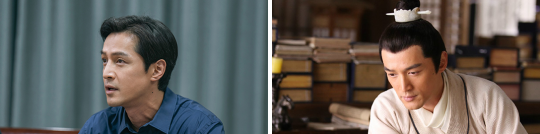

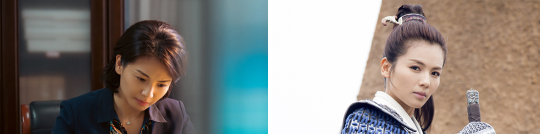

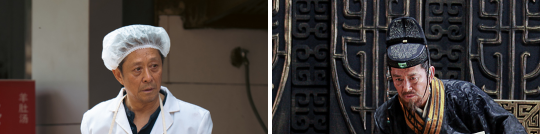

The show is finally airing at the primetime slot tonight (December 7), and the official announcement only came a whopping 12 hours or so before the premiere.

The Daylight Entertainment Cinematic Universe continues with Bright Future/县委大院, starring Hu Ge as local county commissioner Mei Xiaoge/梅晓歌 and featuring many NiF and NiF 2 alumni, including director Kong Sheng. A behind-the-scenes featurette was released at the wrap of principal photography, and it’s expected to air in October this year.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanbook Review: 《梅岭千秋》 by 壹染

《梅岭千秋》 (roughly Meiling Undying) is a 2016 fanbook with art by Yiran/壹染 and published by 溯年组, depicting scenes and characters from Nirvana in Fire. I had to get my hands on a copy after falling in love with the art.

Yiran paints with ink brushes and watercolor on xuan paper/宣纸, a famous traditional Chinese paper made from the qingtan/青檀 tree especially suitable for calligraphy and painting. Xuan paper is divided into raw/生宣 and processed/熟宣 types, the former more absorbent with a tendency for ink to run free, and the latter processed with alum to be more controllable for precision ink work (the two types of traditional painting, evocative xieyi/写意 and realistic gongbi/工笔, are often split along raw and processed xuan in their choice of medium).

Raw xuan is particularly unforgiving to beginners, but Yiran is a master of her craft, able to achieve both precise lines and textures as well as the misty landscapes so characteristic of Chinese watercolor on this paper (see her Lofter for her process and more art). She often paints an entire series of pieces on a traditional accordion booklet/经折装, a single long sheet of paper folded on itself many times, as she did for this project (photos from her Weibo, which also has more art):

The publisher took care to replicate the original booklet of pieces as closely as possible in the final product. Beneath the outer paper jacket is a cover made of woven Song brocade/宋锦, with 38 accordion-folded A5 pages inside. The pages are textured imitation xuan paper, printed with a lacquered black ink that glows under the light:

One side of the folded pages is mostly landscapes and scenes inspired by canon: Mei Changsu and Lin Chen in Jiangzuo beside flowers in bloom, an all-smiles Lin Shu embracing Jingyan in the before times. The other is a series of individual character portraits rendered with their attire from the show, their faces referencing the actors’s features but not overly imitative. There’s something revelatory in the way she paints a dreamy, ephemeral scene in one panel and then renders Jingyan’s robes with dramatic, almost impasto-like textures:

Each portrait is also paired with a poem written by 海月. Jingyan’s is

关山诏递寒雨遥,兵戈交鸣追风啸。 赤心不随江河改,铁血独守情义昭。

A possible translation:

Drifting bitter rain in mountains edict-sent, weapons clash as galloping horses scream. A pure heart enduring through shifting tides, alone in his courage, loyalty brought to light at last.

I’ll end with my favorite piece, Chief Mei and His Majesty beholding their mountains and waters:

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nirvana in Fire Historical Parallels: The Warrior Princess

Hua Mulan/花木兰 is unquestionably the most famous woman warrior of ancient China. But how much of her legend actually happened is of debate, while there were many historical women generals who were more similar to Mu Nihuang in NiF. Here are a few of the most notable, in chronological order:

Fu Hao/妇好 (Hao is her family name; before the Qin Dynasty, family names for women were at the end, reversed from the current name order; Fu means married woman now, but could have referred to priestess then), the earliest woman military leader on record, lived during the Shang Dynasty and died in 1200 BCE. Because her time period predated paper, what we know about her came from oracle bone script and the hundreds of weapons in her tomb, which is a burial rite afforded only to generals. As consort to King Wu Ding/武丁, she led an army of 13,000 to many successful military campaigns against the Shang’s enemies. She was not only a general and high priestess, two of the most important roles in that time era, but also owned her own land, which was extremely unusual for feudal women. After her death, the king made many sacrifices at her tomb in hopes of receiving her spiritual guidance to defeat invading enemies.

Mother Lü/吕母 (name unknown, so she is referred to as a mother of the Lü family) lived during the Western Han Dynasty in Langya Commandery and was the first woman rebel leader in Chinese history. After her son was executed for not punishing peasants who could not pay their taxes, she aided peasants under hard times by giving away her considerable family wealth while plotting revenge on the government. During this time, a consort kin to the Emperor had seized the throne and started his own Xin Dynasty/新朝 (literally New Dynasty), enacting many radical socialist reforms such as land redistribution and abolishing the slave trade. A series of natural disasters and poor implementation of the new policies led to great unrest and suffering among the peasant class. Commoners united around Mother Lü, and three years later, in 17 CE, she amassed thousands of loyal followers and declared herself the leader of the rebellion. They took the city, and she beheaded the county magistrate who had killed her son, sacrificing his head on her son’s tomb. As news of her successful rebellion spread, thousands more joined her even as the government attempted to quash her forces. Though she died from illness a year later, many in her army joined the Chimei Army/赤眉军 (literally red brows), a key force in the eventual downfall of the Xin Dynasty.

The most similar to Nihuang is probably Lady Xian/冼夫人, who lived in the 500s CE and served the Liang (the Liang of NiF is very loosely based on this dynasty), Chen, and Sui Dynasties. She was the daughter of a chieftain of a clan of the Li/俚 people and demonstrated great leadership and political acumen from a young age (women in her family could inherit command). She favored diplomatic solutions over fighting as much as possible and was always loyal to the reign, putting down local rebellions and eliminating corruption. Nihuang’s title of commandery princess/郡主 was also one of her titles, and as thanks for her bringing many minority peoples under unified rule, the Sui emperor gave much of modern-day Hainan to her command, much like Nihuang. She lived to around 90 and was given a posthumous name by the emperor as a sign of great respect. Hundreds of temples in the south were built in her honor, where she was deified and remains worshipped today as the Saintly Mother of Lingnan/岭南圣母.

One of many statues of Lady Xian.

Princess Pingyang/平阳公主 (personal name unknown) was the third daughter of the founding emperor of the Tang Dynasty. Her father was an aristocrat who decided to seize the opportunity during the chaos of the failing Sui Dynasty to raise an army in 617 CE, and she decided to help her father ascend to power. With remarkable leadership and recruitment power, she quickly recruited several Jianghu volunteer armies under her wing. More and more people joined as her reputation spread, such that she had seventy thousand under her command by the end in what was known as the Woman’s Army/娘子军. Her forces registered several victories before rendezvousing with her father’s forces to take Chang’an, which would become the capital of the new dynasty. She was given the title of Princess Pingyang and higher honors than her sisters as a sign of her father’s gratitude for her help in starting his new dynasty.

After the coup of Chang’an, there was nothing in recorded history about her until her funeral. A rite officer had objected to burying her with military honors instead of a princess’s rites, but her father and emperor said she always fought at the vanguard of her army, so there was nothing wrong with full military honors. She is the only woman in recorded Chinese feudal history to be interred by soldiers.

Qin Liangyu/秦良玉 (1574-1648) was born to a civil bureaucrat in the late Ming Dynasty who believed in educating women, and she became skilled at riding, archery, and poetry. She looked up to Lady Xian and Princess Pingyang from a young age, and told her father that she would equal their accomplishments if she had military command (倘使女儿得掌兵柄,应不输平阳公主和冼夫人). She was married to a local county commissioner who often led armies to quash invasions from the neighboring Manchu Jin Dynasty, and he gave her command of part of his army. When he died in prison being falsely accused of wrongdoing, she assumed his role, as their son was still young. She defeated numerous Jin invasions across the country, and the Emperor gave her the title of Marquis in recognition of her actions in defending the homeland. She’s famous for being the only female general recorded alongside men in the official histories of her dynasty.

A portrait of Qin Liangyu.

So, what made these women leaders of armies while most women throughout Chinese history couldn’t even dream of such a thing? Fu Hao lived a very long time ago, well before the later Confucian system where wives are supposed to obey their husbands and serve at home. For the others, there are some common factors: growing up in a well-to-do family that educated daughters, demonstrated interest and skill in fighting and leadership, being around military power (true of a vast majority of male generals as well, of course), and some kind of unusual circumstance that gave them power, whether a husband or father allowing them to do so or an environment of unrest that gave them an opportunity.

The warrior princess trope exists for a reason: it’s the highborn daughters and wives of generals who are most likely to get the opportunity to command an army. And their stories are more well-known than, say, women like Chen Shuozhen/陈硕真, who came from destitute upbringings and called herself the emperor while leading a peasant rebellion that eventually failed. All history is biased, and contemporary Chinese history seems to favor those who quashed rebellions and promoted national unity.

Given these historical examples, it’s not so outlandish to imagine that Nihuang was educated by her father in the military arts from a young age, showed great fighting and leadership ability, and was then able to take command when he died during a crisis and while her brother Mu Qing was still too young. She is an exception in a field of men, as these historical women were. And like these women, she was very much still subjected to the expectations and boundaries of feudal women.

In some sense, show Nihuang is an ideal female Confucian role model. She is the perfect daughter and older sister who assumed the family mantle when there are no capable men, doing her duty under a corrupt regime for twelve years, with the implication that she will give up at least some of her responsibilities to Mu Qing when he’s ready. She is the perfect widow who never strayed from her arranged marriage pact. And she is the perfect potential wife who shed all of her commanding aura whenever she interacted with post-identity reveal Mei Changsu—she may question him but she will always listen to him, in the end. Her first scene is of a warrior princess soundly defeating men, and her last big scene is her telling Feiliu she wants to obey her Lin Shu-gege.

This is a far cry from book Nihuang, who moved on in those twelve years and found someone else to love. To be clear, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with characters displaying period-typical attitudes, and other female characters in canon, like Consort Jing, are compelling without being hidebound by tradition. Within the microcosm of NiF the show, the change to Nihuang’s character may only be due to the creators wanting to increase her screen time in a male-heavy show and add a tragic romance element that they felt the book lacked. But media doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and after some prominent examples of one-sided adaptation changes in recent years—The Rise of Phoenixes taking a book starring a strong female character and dramatically increasing the male character’s screen time for the actor to get top billing, Serenade of Peaceful Joy adapting a book centered around a princess’s futile rebellion against feudal expectations for women into a show about her loving daddy emperor trying to do the best for his daughter by keeping her in line, even Reset giving some of the main female character’s heroic moments in the book to the main male character in the show, to name a few—was Nihuang’s change from book to show a harbinger of the male-dominated Chinese television industry increasingly reshaping strong female characters into what they think women should be like?

This issue of media depictions affects historical women generals, as well. For various reasons, they haven’t gotten their big breaks in modern mainstream media, and the most famous Chinese female warriors remain Mulan and a few other very fictionalized characters who have had popular shows and movies made about their lives. A Qin Liangyu drama was supposed to be filmed a few years ago but never aired, and as typical of this era of Chinese media censorship, no one seems to know what happened to it.

With the lack of extant details for most of these military leaders, one can depict them as either true believers of Confucian values or as women who questioned and struggled against societal conventions. It isn’t hard to guess what’s more likely to be made today, with a slapped-on love story and plenty of screen time for the men to boot. If we can’t give a warrior princess a sword without always making her a dutiful daughter, wife, and patriot, perhaps we shouldn’t be telling her story to begin with.

#mu nihuang#nirvana in fire#琅琊榜#chinese history and culture#long post#a few more women cut for space:#Xiao Yanyan/萧燕燕#Liang Hongyu/梁红玉

389 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just want to add that the meridian surgery was very much inspired by what happened in 风骨同守. Curing MCS’s poison is always going to be contrived to some degree, but I think the way this fic does it is a textbook example of how to write a fix-it (mild spoilers below):

The rare art of regenerating meridians that can cure MCS was passed down through the He family of imperial healers and bureaucrats. The last doctor to perform it successfully was disgraced after the Chiyan case because of ties to Prince Qi—his brother was among Prince Qi’s people who died. The He family left the capital, and the doctor died without seeing the case overturned. His son He Zhengming is the only one who still has records in the form of his notes, but he’s eking out a life in seclusion. After the case was overturned, he wholeheartedly wants to serve Jingyan in gratitude, but a commoner is never going to get his message into the palaces. It’s not until Marquis Yan mentions in passing a palace legend of meridian repair that Jingyan pursues it to the end.

The sequence of events is tight logically:

In canon, Lin Chen says MCS’s plastic surgery is an extreme cure that eliminates the poison, with a side effect being recurring sickness, except then the poison hung around to counteract the Wujin poison and the end of the show is all about how there’s no cure for the poison—it doesn’t make a ton of sense. This story describes the treatment as something that removed most of the poison, with the remnants not a big problem for healthy people but very dangerous for him because his meridians were already ravaged by the poison. And so they have to find medicine that counters both frost and flame parts of the remnant poison, which is doable, while trying to find a root solution for strengthening his lethally weak body, which is much harder. You can plausibly handwave Lin Chen not explaining all this in canon to laypeople because it would take up too much time, and it didn’t matter anyways because there was no solution.

Marquis Yan doesn’t know the details of MCS’s condition, and so he would have no reason to bring up meridian healing before, especially because it was done by a Prince Qi loyalist, and everyone has been conditioned over the years to keep their mouths shut about anything Chiyan-related to stay alive. This is also a great nod to the identity reveal in the novel, even though this fic mostly follows show canon—once again, Marquis Yan spills a crucial fact by accident.

The He family served the palace, far from the Jianghu, and the meridian surgery was never publicized because it involved imperial secrets, so Langya Hall wouldn’t have known of it.

The themes it touches on are A+:

The tremendous loss of the Chiyan case—not just seventy thousand soldiers and everyone who was loyal to Prince Qi or dared to stand up to power, but also the knowledge that they and their families have cultivated over generations. The songs they’ve sung, the jokes they’ve told, their tricks for a bountiful harvest. It’s as if the library of the collective knowledge of the world lost an entire wing overnight, and everyone pretends it never existed. Even after the case was overturned, too much has been forgotten and erased that will never come back.

The insular nature of imperial power and how it’s ultimately detrimental to both the people and the throne. How the He family’s advanced medical art was reserved for the palaces when it could potentially be saving lives out in the world. How He Zhengming wanted to serve Prince Jing but knew he had no chance. Very much reflective of canon as well—nearly everyone we see on screen are at the upper echelon of power or serving it. They speak casually of abstract numbers that can save or devastate so many people’s lives, but the actual people are far out of sight.

Truly good deeds will be rewarded—He Zhengming is willing to pour his heart and soul into saving MCS because he was the one who restored his family’s name. The loyalty that cast his family into darkness fourteen years ago is what restores them back into the light now. MCS being cured by an art that was lost due to the Chiyan case is so poetic.

Speaking of being rewarded, Jingyan’s persistence and sense of duty through the darkest times, bearing the country on his shoulders while never giving up on finding a cure—when we get to the Jingsu happy ending, it feels both earned and deserved.

In conclusion, if you must write a canon-fixing deux ex machina as a significant plot point, consider writing one that brings out themes you want to impart.

Hello from your fallinlangya buddy! I’m in awe of your varied tastes ^^. And command of Chinese, I wish I, too, could read on anything on lofter. Maybe one day… As for what I ship, I go with jingsu most of the times as it has the highest number of fics on ao3. They’re not what I’d normally ship as they are essentially friends to lovers, which I as a rule find not spicy enough, but the identity shenanigans make them fun enough for me. But... (tbc)

Your fallinlangya buddy here again! You are right that having all fics going with the blood of 100 men as an established cure for MCS would be boring as hell. Can you imagine some other cure for him?

--

Unsure if these were the only two asks you sent or if tumblr ate one of them in the middle. If it did, please send it again <3

What are your favourite tropes for a ship, then? what was the ship you thought would be the biggest in this fandom watching the show? Did you see Jingsu then yourself or was it a fandom-induced main ship for you?

My Chinese is really bad, nothing to be impressed about really. I read fanfic because knowing the settings/characters/dynamics is helping me parse things, otherwise I would be even worse. But hey, no getting better if you don't practice, right? So at one point I'll get better, I hope. In the meantime, blessed be pleco.

I had to go through all my WIPs and not-fics and random notes and I don't think I have ever made up an interesting cure for MCS.

Frankly it's because 1. I am deeply invested in the fact that sometimes, there are no cures. Sometimes the only choices you get is how to deal with your palliative care, and agency over your own death. Characters with shortened lifespans and last-minute-saving-cures are dime a dozens in media. Characters living with chronic pain and disability are already rarer. And MCS got agency, and his choices respected, and no one went behind his back to try to save him against his will as if being disabled and dying meant that his choices were not valid. That is so incredibly rare in fiction??? I loved that so much. I've said before that NiF has a happy ending, and I mean that with all my heart. So, in most of my personal fiction, I just don't try to cure him at all.

2. even when I play with the parameters of the Frostfire Poison, the point of divergence is generally earlier in my AUs. Meiling doesn't happen, or happens differently, there is less of the poison in the first place, or immediate treatment available, or different treatment choices were made, etc. And it still tends to be different chronic problems, not a cure. Usually I reverse-engineer the problems, I go from the symptoms I want him to have in that story and I change things so it makes sense for him to have them.

I have one story where he is old, and I just never cared to make up a cure then, because it's not the point of that story, obviously something was found since he is alive, no need to explain how.

3. So after thinking about it for a full day, I'm pretty sure the only time I actually made up a cure was for a story I plotted with @hardwareabstractionlayer where at one point we were like "ok, we actually need him to be cured of the poison". We settled on "extremely risky surgery to reattach forcefully his meridians", because that made the most sense in our set-up, and, once again the cure was not the point of our fic anyway. So that was collaborative work, and chosen purely for the sake of what was convenient for the story we wanted.

4. could I make up other cures? well sure, it's not like we are missing on tropes to do that. Other weird poison to re-introduce equilibrium in his system, or using the fact that Jingyan becomes emperor and emperors have power, or weird plants, whatever. I'm not deeply invested in that cure in general; if i had to make up cures, I would reverse-engineer it: why do I want a cure and what do I want cured? Is it just his shortened lifespan? Is it the chronic pain? Is it all his other symptoms? Do I want him to have new symptoms? Just a few more years? Do I want him to get stronger? Etc. And when I have decided on that, then I will use whatever gets me the results I want.

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

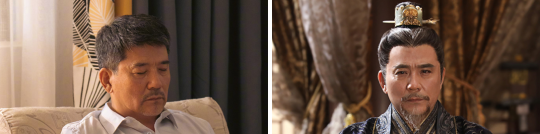

Happy 40th to Cat Dad.

When you’re standing atop a mountain and you want to go, go some place higher, the only thing you have to do is come down first. Only when you’ve descended to ground level can you climb a taller mountain. 当你站到一座山峰上的时候,你想要走,走到更高的地方,你唯一要做的事情就是,你得先下来。你只有先下到平地,你才有可能去攀登更高的山峰。

Happy birthday Hu Ge 胡歌生贺 September 20, 1982

198 notes

·

View notes

Photo

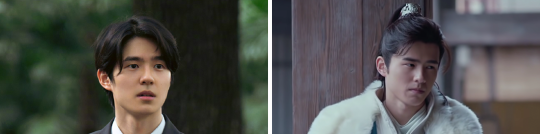

Nirvana in Fire premiered September 19, 2015.

164 notes

·

View notes