ᛟA blog dedicated to Germanic polytheism, European traditions, mysticism, and all things religion and esoterica ᛟ

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Acts of Devotion: Leaving Offerings as a Pagan

Part 2!

What Offerings Are

Another question I’ve encountered frequently on the internet is how exactly offerings should be disposed of. There are many ways to do this, such as burning it or even submerging it in some kind of body of water (or vessel of water). Burning is the most common method of disposal that I’ve seen, but you can utilize any of the elements to get rid of the offering. If the offering is perishable, burying it on your property is an excellent option, especially for land spirits and ancestors. For offerings of food, I believe that eating the offering is also a perfectly acceptable way of disposing of it, due to the examples previously given in which the sacrificed good was eaten by the community anyway. I’ve seen many wonder if throwing the offering in the trash is acceptable due to living in a more urban environment, and I personally do not see any issue with this. After understanding what an offering is, one can consider when they should be given.

When to Give Them

As previously mentioned, our ancestors often gave offerings with a specific goal in mind, such as a good harvest. Therefore, if you are looking to ask the Gods for something or for guidance, leaving an appropriate offering would be an excellent idea. These offerings should be tailored to the specific God and/or the occasion, and I will be providing a list of suitable offerings for each God in my next post! Holidays are also great days to leave more elaborate offerings. They may also be tailored to the God and the occasion, but generally suitable offerings for these days are meals and libations of mead or another beverage. Offerings can technically be left as often or infrequently as one wishes, but I would advise to leave an offering for each of the Gods at least once a week. Leaving an offering for a God each day (such as leaving something out for Mona on Monday, then Tiw on Tuesday, etc) will also strengthen your connection to the divine with that specific deity in mind. As for the time of day, giving the offering during the planetary hour that corresponds to said God or Goddess allows the experience to be particularly potent. There are a number of calculators online for planetary timing. For moon deities specifically, leaving offerings and/or performing rituals based upon the specific phase of the moon may also be helpful. For instance, the full moon is considered the most metaphysically significant, and the waning phase is great for banishing. The crescent moon is typically the most important for Eastern traditions. In general, the timing of an offering can greatly strengthen the experience of interacting with the divine, though it is always important to leave offerings based around your specific schedule so that the relationship may be sustained.

Conclusion

Offerings are imperative for cultivating a relationship with the divine, spirits, and ancestors. Despite this, their significance has been greatly watered down by many individuals online. Acting as a symbol of devotion, our ancestors left both elaborate and simple offerings for the divine. A high level of care and connection is expressed when time is taken out of the day to prepare an appropriate gift. Our ancestors also understood the importance of context, leaving suitable offerings when in times of need or to express appreciation to the Gods. Timing was also understood as having a great influence over the reception of the offering. By enacting all of this knowledge, it is possible to experience great spiritual progress while fitting this important action into daily life.

#esotericism#occultism#germanic paganism#anglo saxon#paganism#norse paganism#anglo saxon paganism#neoplatonism#platonism#offerings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Acts of Devotion: Leaving Offerings as a Pagan

Part 1!

An important part of developing a practice as a pagan is understanding what offerings are and how to utilize them. In an age where neopaganism is on the rise, many see the process of leaving offerings to deities as instant and transactional, the Gods acting as no more than ATMs. However, this concept is not only immensely self-serving but also very fruitless when attempting to establish a relationship with the divine. The goal of offerings is to give back to the divine (as well as ancestors and lower spirits), not to simply give with the hopes of receiving something. Another crucial element to giving an offering is the principle of sacrifice. In all historical sources, offerings required some extent of effort. Large feasts would be held to honor a God, and animals would often be sacrificed as well as prepared as an offering. In order to cultivate a sustainable relationship with the Gods, it is imperative to understand when, why, and how to leave offerings. This post delves into the historical and spiritual significance of offerings, in what contexts they should be utilized, and how often one should leave them.

What Offerings Are

There are many examples of offerings in a variety of both written and archaeological sources. While I will not be diving into all of those here, I will briefly describe a few instances of offerings from around pagan Europe. In each instance, the principle of giving something up is obvious. Offerings were not something randomly given with minimal effort. Rather, they were carefully selected with the divine in mind and often involved the individual gifting it giving up something valuable, such as time or a resource. A prominent example of this can be found in the blóts of the Germanic world. The term blót itself translates to sacrifice, and the Gothic form of blotan specifies the act of serving God. These were often performed for a specific reason, such as for victory or a good harvest. During a blót, a sacrificial animal would be killed and offered to the divine before being prepared and eaten during a feast. Relatively well-known instances of these blóts include those at the temple of Uppsala described by Adam of Bremen. Here, horses were often sacrificed, with the heads typically being given up as the offering. During these blóts, blood was often in some way incorporated, usually sprayed upon altars or participants. The Romans also had quite an elaborate method for sacrificial killings and offerings which parallel those of the Germanic peoples in many ways. These sacrifices were also performed for similar reasons, such as to give back to the divine and ask for help in some area of life, or even as a way to make amends with the divine, so to speak. However, offerings of items such as wine and incense were also common and regularly left at altars. These two examples highlight many key points for giving offerings. Firstly, you need to actually be giving something up. I’ve seen many people buy something premade and then give it to the Gods, and in my opinion, this is not the best option for many reasons. Our ancestors had to take time out of their day to make whatever they were using as an offering. They had to kill and prepare the livestock or bake the cake that they would then leave at the altar. Not only was this a necessity, but you are then doing your part in giving something up. Additionally, by putting the effort into manually creating an offering, you are also showing a higher level of care. Even amongst humans, a handmade gift is often regarded as more meaningful and sentimental. By making something yourself, you are showing a high level of dedication. However, there are also records of jewelry and other items being given as offerings across Europe. So this is not to say that in every instance you must make something from scratch, but it certainly shows a deeper connection to the divine and immaterial realm. Furthermore, you do not need to have some elaborate ritualistic process to leaving offerings all of the time. This is simply unrealistic in the modern world, and this was also not even done daily in the ancient world, so reserving this dedication for holidays is advisable. If you wish to give offerings each day or even weekly, a happy medium would be something such as a meal, because this requires time and labor, but it is not going to take several hours out of your day.

#esotericism#germanic paganism#anglo saxon#norse paganism#paganism#occultism#anglo saxon paganism#platonism#neoplatonism#offerings

1 note

·

View note

Text

Plotinus: Father of Neoplatonism

Plotinus is arguably one of the most influential figures of the occult mysteries, having inspired early church fathers, gnostic sects and polytheists alike. A pupil of Ammonius Saccas, he later went on to futher the ideas of Plato with his own profound insight. Having garnered the support of both emperors and religious authorities from a plethora of traditions, the thoughts of Plotinus still shape mystical practices today. Moreover, Plotinus was not just a great philosopher, but an experienced mystic and friend to many all over Rome, promoting education as well as generosity. The teachings of Plotinus are perhaps the most inspiring and thought-provoking works that have shaped my own understanding of cosmology. Still, there are many facets of Plotinus that are vastly under discussed within esotericism. This post will delve into the life, the works, and the legacy of Plotinus.

The Life of Plotinus

Plotinus was born in 204 CE in Roman Egypt, either in Asyut or modern day Segin al-Kom according to the Greek historian Eunapius, though this is not confirmed by the documenter of Plotinus’s life, Porphyry. It is likely that he was of Greek descent and he wrote as well as spoke Greek primarily. Few details about Plotinus’s early life are confirmed by him or Porphyry as he preferred to remain mostly unperceived. In 232, Plotinus began his philosophical studies in Alexandria. He did not particularly enjoy his time here, not exactly finding the teachings of any of the scholars he encountered very agreeable. Taking up the suggestion of a fellow pupil, he began to study the teachings of Ammonius Saccas, a significant philosopher of early Platonism. For the next 11 years, Plotinus would dedicate himself to the teachings of Saccas while also growing influenced by Aristotle, Heraclitus, and Stoicism. After his studies had ended, Plotinus decided to join Emperor Gordian’s journey to Persia, most likely to study the philosophies of the Eastern scholars. However, the expedition did not go as planned when Gordion was killed in Mesopotamia. Plotinus was left with no choice but to flee to Antioch after being stranded in perilous and unknown territory. At the age of 40, Plotinus traveled to Rome where he would spend the rest of his life teaching and compiling various metaphysical writings. It is around this age that he began to write his first works on the spirit which would later become the third and fourth tractates of the Enneads. In Rome, Plotinus gained a number of followers including Senators and doctors, as well as his life-long friend Porphyry. A woman named Gemina was also a pupil and dear friend of Plotinus. The teachings of Plotinus at this time were based heavily on contemplation, a stoic mindset, and detachment from the material realm. These sentiments are also strongly reflected in the Enneads. Porphyry wrote that he was essentially a friend to everyone in his community, assisting families and teaching children. Despite his view of the material as “lower,” he still strongly valued those around him. However, not all took a liking to him; it is reported by Porphyry that an individual known as Olympius attempted to cast harmful spells upon him, though quickly found that the spells seemed to be reflected back to him with much more power. Emperor Gallienus was so fond of Plotinus that he considered building a Platonic city in a region of Campania, though ultimately declined due to issues with Rome’s Senate. Another brief tale of Plotinus that illustrates his altrusim that I wish to include is an incident recorded by Porphyry in which he was considering suicide, but was sent out of Rome by Plotinus, ultimately saving his life. Plotinus would later die in a Sicilian estate, his last words being “I long been waiting for you; I am striving to give back the divine to the divine in the All” as attested by Eustochius.” He was 66 years old.

The One, The Nous, The Soul

The One, the Nous and the Soul are very complex concepts integral to Neoplatonism, and it is unlikely that my summaries will do them justice. I simply suggest reading the works of Plotinus, but I may create a more in depth post on these ideas in the future. According to Plotinus, the One is both undefinable and unknowable. It is beyond human comprehension. In fact, to name it is somewhat innaccurate because the One cannot be indentified by reason. It cannot be differentiated or distinguished because it is beyond both. However, it is possible to know the unknowable One through contemplation. The One is often regarded as the source, a somewhat accurate word due to it’s emanationist nature, but also misleading. It is not the source because it is not a being, though other things come into being through imperfect contemplation of it. The One is mostly an omnipotent active force. Secondly, the Nous is regarded as the Intellect. It is the transcendent force of a contemplative nature. The Nous is the greatest power and gives differing identities to things. Primarily, the Nous is the cognitive force of the Cosmos, operating like the mind (and also referred to as such.) It is both thought and the generator of thought, unified as both. Lastly, the Soul gives more objective, tangible shape. It generates the material, more specifically the material image of the inteligible. There are two parts of the soul, the higher and the lower. The higher part of the Soul is closer to the noetic, and one’s soul may ascend through noetic activities. The lower part is what gives shape to the cosmos and is closely associated with the senses. The lower part may be corrupted while the higher is untouchable.

The Works of Plotinus

Plotinus is mostly known for his Enneads. The third and fourth tractates, or Our Tutelary Spirit, discusses the generative soul in every form of life. He states that everything begins formless, and that there is a duality between things on the further side of the soul, the imageless, and those nearer that have more form. The lower soul is primarily driven by the material and the senses while the higher soul is comprised of a divine intellectual nature. The tutelary spirit is rational, and it is stated that the spirit behind man is the secondary spirit, which is guided by this higher spirit. The Enneads also heavily focuses on the aforementioned One, Nous, and Soul. It discusses emanationism, as well as the metaphysics of love and virtue, reason, and evil. This work is very complex and again, I cannot even attempt to give a thorough summary. Plotinus also wrote a treatise against the Gnostics, essentially arguing against Gnostic philosophy and cosmogoly. For instance, Plotinus advocated for spiritual ascent through purification rather than ritual. He also did not view the material world as inherently evil and disagreed with the Gnostics on the number of principles of origin. Plotinus argued that the Gnostics confuse the functions of each principle and that they view the generative functions of the One very shallowly. Of course, there are many conflicts between the Abrahamic and Polytheist worldviews.

Mysticism

Aside from being a skilled philosopher, Plotinus was also an experienced mystic. He discusses his experiences with ascension in the Enneads. Meditation and moral virtue are methods Plotinus advocated for as well as participated in, and he further develops the Platonic methods of ascent. His last words also reflect his spiritual experiences.

Conclusion

Plotinus is not only a significant figure of the esoteric due to his development of Platonic thought, but his promotion of education as well as philosophy during his time in Rome. He also partially shaped the culture of Rome through his interactions with political figures. Lastly, his personal anecdotes of mysticism demonstrates the practicality of his teachings and informed a number of religions today.

“ℌ𝔢 𝔴𝔞𝔰 𝔤𝔢𝔫𝔱𝔩𝔢, 𝔞𝔫𝔡 𝔞𝔩𝔴𝔞𝔶𝔰 𝔞𝔱 𝔱𝔥𝔢 𝔠𝔞𝔩𝔩 𝔬𝔣 𝔱𝔥𝔬𝔰𝔢 𝔥𝔞𝔳𝔦𝔫𝔤 𝔱𝔥𝔢 𝔰𝔩𝔦𝔤𝔥𝔱𝔢𝔰𝔱 𝔞𝔠𝔮𝔲𝔞𝔦𝔫𝔱𝔞𝔫𝔠𝔢 𝔴𝔦𝔱𝔥 𝔥𝔦𝔪. 𝔄𝔣𝔱𝔢𝔯 𝔰𝔭𝔢𝔫𝔡𝔦𝔫𝔤 𝔱𝔴𝔢𝔫𝔱𝔶-𝔰𝔦���� 𝔶𝔢𝔞𝔯𝔰 𝔦𝔫 ℜ𝔬𝔪𝔢, 𝔞𝔠𝔱𝔦𝔫𝔤, 𝔱𝔬𝔬, 𝔞𝔰 𝔞𝔯𝔟𝔦𝔱𝔢𝔯 𝔦𝔫 𝔪𝔞𝔫𝔶 𝔡𝔦𝔣𝔣𝔢𝔯𝔢𝔫𝔠𝔢𝔰, 𝔥𝔢 𝔥𝔞𝔡 𝔫𝔢𝔳𝔢𝔯 𝔪𝔞𝔡𝔢 𝔞𝔫 𝔢𝔫𝔢𝔪𝔶 𝔬𝔣 ��𝔫𝔶 𝔠𝔦𝔱𝔦𝔷𝔢𝔫.” - 𝔓𝔬𝔯𝔭𝔥𝔶𝔯𝔶

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Intuitive Approach to Polytheism & Ritual in 2025

In one of my first Instagram posts of 2025, I mentioned that I believe intuitive practices are “in” while ceremonial practices are “out.” For the past couple of years, I have incorporated relatively complex rituals into my religious practices, however, I find that this is no longer beneficial in my current life circumstances. The world is extremely fast-paced and work-centric; I believe many pagans in the modern day struggle to find the time to dedicate to religious observance and worship. Moreover, there are swarms of individuals online screaming from the rooftops what they believe to be the “right” practices for a pagan. In this post, I will be defining the difference between an intuitive and ceremonial practice, my approach to my religion in 2025, and why the opinions of those online don’t really matter.

It seems appropriate to first define what a ceremonial practice is in comparison to an intuitive practice. This is not to say that the two are opposites, but they are unique approaches that may sometimes overlap or not at all. A ceremonial practice often involves lengthy planning and is typically more formulaic in nature. This is often seen in blóts or other pagan holidays. Personally, I pay attention to various correspondences and have a specific structure that I follow during a ritual. I pay attention to the color of the garments I wear, the incense I burn, what direction I’m sitting, the hour of day, etc. However, this has made it exceedingly difficult to remain consistent with my faith. I have found that my strictness surrounding day and time of day has particularly disrupted my practice; I simply don’t have the time to dedicate to ritual some days. As a result, veneration and religious acts of any kind grew extremely spotty with me. I realize now the crucial point of this post: if it’s not working, then stop.

An intuitive practice is not necessarily bound to the structure or requirements of a ceremonial ritual. The entire flow of your practice is much more natural and conforms to your life. One’s religious knowledge and knowledge of ritual should certainly still inform what this practice looks like, but it is different from a ceremonial practice in the way that it is flexible. For instance, I often no longer consider the color of the garment that I wear or the exact time of day that I perform a ritual, leave an offering, or pray. The strict formula seen within a religious rite is disrupted. Oftentimes, this kind of practice is not as elaborate but pulls from the key elements of our ancestor’s faith (as well as their purpose of performing them.) I also feel that a more intuitive approach is inviting to those still exploring polytheism. It is incredibly easy to become overwhelmed by historic sources describing the temples of antiquity or the celebratory precessions of yore. Furthermore, neopagans and reconstructionists alike do not shy away from sharing what they believe to be the correct and incorrect way to practice polytheism- an easy source of stress in today’s digital age. However, both of these pressures have taught me two things; first, we must follow our religion in the context of our time. Our ancestors did not have an immensely ornate schedule that they followed regarding work and life, and they were not bound to the environment of an office or cubicle. The values and teachings of our ancestors are timeless; we can apply them efficiently within the constraints of our own lives. Secondly, there is certainly a correct way to follow the faith of our ancestors, though this has less to do with the tangible characteristics of such. For instance, there is absolutely zero reason to go out and buy hundreds of dollars worth of materials to create an altar. I would argue that you could actually have an extremely fulfilling and correct religious practice without anything at all. It is important to not disregard the elements central to the beliefs of our forefathers- the worship of nature and love for the Gods.

Observing nature’s cycles has helped me develop a more consistent and stress-free practice. During the winter I took a large step back and thought about what my relationship with the Gods looked like then and what I wanted it to look like in the future. With the return of the sun, I’ve made it a large priority to continue evaluating how I practice my religion. I have found that praying regularly, burning incense, and spending a few moments in meditation is a suitable routine for me. The goal of following my religion in this way is solely to further my connection with the divine, the Earth, and myself, so again one’s practice should be tailored to their own goals. I also like to engage in activities that allow me to feel closer to a specific God or Goddess (or other spirits) on corresponding days of the week. Historical sources such as the Eddas or the Sagas are great for getting a grasp on this, as well as reading up on planetary remediation. Paying attention to the holidays and celebrating a bit more elaborately is a great way to dedicate more time towards your faith while having quite a few sources to assist you in deciding which festivities you may partake in. These are also opportunities to leave offerings for the Gods, though I advise you to generally try and do this a bit more often. Moreover, I encourage others to “play” with their practice a bit more- as in, do not be afraid to change what you’re doing if it is not working. Read historical attestations, research archaeological findings and historic sites, try runic meditations, or write metaphysical poetry (especially in the language of your ancestors). It is simply nonsensical to continue doing something that is not productive for your personal growth and relationship with divinity.

In summary, I encourage both experienced and new polytheists to critically analyze their current practice and how it impacts their lives. In today’s busy world between careers, family, and school, it is essential to cultivate a sustainable and fulfilling practice, as well as a persevering dedication to one’s faith. Take every opportunity to learn about the divine and other spirits, your ancestors, and the land. What is real- nature, ontological truths and good- is the most significant, not the words of strangers online. As a polytheist, you are not obligated to stick with one kind of practice. You are, however, obligated to uphold traditional pagan values and love for the divine through your lifestyle and actions.

#germanic paganism#anglo saxon paganism#norse paganism#occultism#esotericism#anglo saxon#neoplatonism

1 note

·

View note

Text

Living in Tune With The Seasons as a Pagan

One of the most central beliefs to polytheism is living in tune with nature and the worship of nature. This includes not only the tangible aspects of nature, but the more obscure qualities such as its various cycles. The seasons are crucial to this. While each month is lunar, the yearly calendar of the Germanic peoples is solar. We see that the sun was crucial to the Germanic peoples not only through their concept of the year, but throughout the many holidays within the lunar months. This is understandable as the sun is a life giving force; it allowed for a good harvest, the blooming of flowers, and a general sense of vigor. As a result, many of the holidays and rituals of the Germanic peoples focus on the celebration of the sun or awaiting its return. All of this strongly guides my observation of the seasons- a practice I also wish to improve on throughout the winter as well as the coming year. This blog post will outline what each season means to me as a Germanic polytheist and how I strive to live more cyclically.

Firstly, it should be noted that the seasons tie in with the ever-present birth-death-rebirth theme within every pre-Christian religion. This is also observed in many heathen holidays. For instance, the celebration of the spring equinox is associated with fertility and worship of the Goddess. Meanwhile, the prevalence of bonfires in nearly every holiday emphasizes the aspect of solar worship and return of the sun (in addition to birth/rebirth as the solar principle is embodied by the Goddess Sunne). It should also be noted that the Germanic tribes had a different concept of the seasons than us. Winterfylleth or “Winter Nights” in October marked the beginning of winter while summer began in June. The full moon of winter indicated the new year. With this in mind, I will be starting my discussion in winter and move into the following months.

Winter

Winter is a month of death. This is the coldest season, the most barren season as trees lose their leaves and vegetation dies off. This would have been a crucial time for our ancestors as they survived through the cold. Sacrifices were made at this time with the hopes of having a fruitful year. Goddess worship on Winter Nights indicates that our ancestors were not only seeking protection throughout these trying times, but that they were looking forward to the growth which takes place during the warmer months. Worship of the ancestors resting deep inside burial mounds, the womb of the Earth, highlights the preparation for rebirth which takes place at this time. Bonfires act as the warmth of the sun. As a pagan, I view the death of the vegetation around me as an opportunity to let go of circumstances that no longer suit me. The hibernation of many species indicates that as much as this is a time of survival, it is also a time for rest. There will be a lot of work to be done in the warmer months which requires slowness and ease now. This is a time about looking ahead: longing for the vitality of the sun as well as the growth which begins with the return of Sunne. I would embrace a slower lifestyle at this time and use this as an opportunity to prepare. Welcome the changes in your life; all that leaves you at this time is meant to. This is a wonderful time for purification as we prepare for a time of growth. It is also important to make goals and promises to yourself and others during this time of preparation- it was common to take oaths during Geolmonath. I speculate that creating New Years resolutions has its roots in this tradition.

Spring

Spring is a month of new life emerging. This is the transition from death to rebirth. The slowness of the winter will begin to ease into the vivaciousness of summer. For our ancestors, fertility and health were central during this time. Fertility of crops and the land allowed our ancestors to thrive. Similar to Winter Nights, Goddess worship will take place during the spring equinox. Lovers would often attempt to conceive as they were blessed by the Goddesses at this time. Wildlife begin to wander out of their comfortable homes and we see flowers bloom as Sunne’s radiance returns. As a pagan, I take this as an opportunity to wake up alongside the Earth. This is a time to begin pursuing change and incorporating new goals into your life. Begin to put into action all that you prepared during the winter. For couples, of course this is a wonderful time to conceive if this is a hope of yours. Otherwise, this is an excellent time for a relationship to grow. This can be applied to romantic, familial or platonic relationships. Take time to nurture the bonds with loved ones in your life. Begin to undertake creative projects as we begin to see the principle of birth and generation. Overall, it is time to spread your wings! Wake up and leave your nest- put your new energy to use.

Summer

Summer is the month of life. The sun’s vitality is in full swing. Fresh crops are flourishing and the trees are once again dressed in their green foliage. Animals roam freely for food while livestock graze on grass beneath the sunlight. The sparkling waters were a place our ancestors would visit to find a reprieve from the scorching heat. The summer solstice celebrates the return of Sunne; she’ll be around for a while seeing as this is the longest day of the year. Dagr rides through the sky on Skinfaxi, alerting all of us to Sunne’s presence. Bonfires reflect the energy and strength of this time. Water from sacred wells and rivers may have been sprinkled over the land. This water, symbolic of amniotic fluid, signals the rebirth of nature. I see this as a time to be as active as possible. This may seem difficult if you are like me and can hardly spend any time outdoors during the summer due to the heat, but this may apply to several other areas of one’s life. Sunne’s vitality can be directed into one’s personal, creative, or professional life. Moreover, the solar principle embodies creativity and the arts. This is a great time to try out a new artistic hobby or focus on a project near and dear to you. However, the solar principle is also strong, harsh even- this is a time to take on challenges. Testing your mental and physical endurance will come more naturally at this time. We also see the importance of purification once again at this time of new birth. Purification rituals are particularly beneficial as well as spiritual initiation. Life was busy to our ancestors at this time- managing the land, hunting, raising animals, looking after the children while the men were away. This is the time to put your all into everything you do.

Fall

Fall is a month of maturity. It is the journey towards death. The trees are beginning to lose their leaves. The grass is drying out and a cool breeze begins to permeate the air. However, our ancestors would have been looking towards this time of harvest. It is once more time to say goodbye to Sunne. All were hoping for an abundant harvest for the upcoming winter months, so this is also a wonderful time to ask for blessings from the Gods. Despite the cool temperatures at this time, there is a sense of warmness to the autumn. Our ancestors celebrated their hard work during the summer and rejoiced with their families during the autumn equinox. All would gather around the bonfire, instilling a sense of community which would be especially important during the perils of winter. If spring is the time to ease into activity, fall is certainly the time to ease into slowness. I find this to be a great time for focusing on all things which soothe the mind, soul and body. However, enjoying the fruits of your labor at this time is also a large theme. This is a period of gratefulness for the efforts of both yourself and others. Spending time with those close to you and helping those around you in any way possible is especially beneficial during this time. Overall, there is an emphasis on family and community as well as the results from the several months of hard work. This season is about giving your thanks to the Gods, to your ancestors, and to the Earth.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simon Magus: Great Power of God or Father of All Heresies?

Simon Magus is certainly one of the most controversial figures in Christian history as suggested by the title “father of all heresies” given to him by Irenaeus. He is considered the founder of Gnosticism and his story is told in the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament. Justin Martyr also wrote on Simon Magus quite extensively in his First Apology. There is a wonderful quote from Chapter 26 that introduces the figure of Simon Magus quite well and I will copy it here in it’s entirety: “There was a Samaritan, Simon, a native of the village called Gitto, who in the reign of Claudius Caesar, and in your royal city of Rome, did mighty acts of magic, by virtue of the art of the devils operating in him. He was considered a god, and as a god was honored by you with a statue, which statue was erected on the river Tiber, between the two bridges, and bore this inscription, in the language of Rome: "Simoni Deo Sancto," [which means] "To Simon the holy God." And almost all the Samaritans, and a few even of other nations, worship him, and acknowledge him as the first god; and a woman, Helena, who went about with him at that time, and had formerly been a prostitute, they say is the first idea generated by him. And a man, Menander, also a Samaritan, of the town Capparetaea, a disciple of Simon, and inspired by devils, we know to have deceived many while he was in Antioch by his magical art. He persuaded those who adhered to him that they should never die, and even now there are some living who hold this opinion of his.” However, Simon as portrayed in the Acts and the writing of Justin Martyr is not definitive. This post will discuss the story and teachings of Simon Magus.

The Life of Simon Magus

Justin Martyr’s quote on Simon Magus introduces his life rather thoroughly. The New Testament states that Simon Magus resided in the village of Gitta in the city of Samaria. Some sources attest that he had previously studied Greek in Alexandria. Phillip the Deacon arrived in Samaria after the persecution of Saint Stephen, the first Christian martyr, in order to preach and perform baptisms. It is stated that Simon had already garnered a following at this time. In fact, he was deified by his followers. In the Acts, it is written that Simon was “the power of God which is called Great” according to his followers. Simon and his wife Helene were also associated with the images of Jupiter and Minerva. This is highlighted in Justin Martyr’s claim that his followers declared the woman to be his first idea. It was believed that the creation of Helene from Simon’s mind spawned various angels who then transformed Helene into a human. It should be noted that this attestation comes from Irenaeus who also stated that this occurred after the events recorded in the Acts of the Apostles. This tale parallels the story of Jupiter and Minerva in which Minerva is born from Jupiter’s head. Simon is baptized by Phillip before Peter journeyed to Samaria so that those who had been baptized may receive the Holy Spirit. This was to be performed through the laying on of hands. It is said that Simon viewed this as a way to further his power and attempted to purchase the Holy Spirit from the apostles. Of course, this was refused by Peter. According to the New Testament, this is all to be said about Simon. A text known as the Pseudo-Clementina describes a dispute between Simon and Peter. The work which was attributed to the bishop Clement, one of Peter’s successors, portrays Peter as arguing for the observation of Jewish law while Simon opposes it. It must be noted that in some instances, it appears that Simon is conflated with Paul. This text highlights the historical disagreement between Christians who followed Jewish law and those who believed this to be incorrect. Clearly rivals at this point, the pair feud once again in the apocryphal work known as the Acts of Peter. Like many apocryphal texts, it features particularly absurd happenings such as Simon being able to fly and being impaled by a stick (though completely unaffected, of course). Aside from this, they debate various topics such as the goodness of God. At the end, Simon is gravely injured and subsequently killed by two physicians at Terracina. In a similar story, Simon travels to Rome where he gains the support of Nero before falling to his death after taking flight. There are a number of other tales about Simon Magus, though I’ll finish this section here for the sake of length.

The Teachings of Simon Magus

The Great Declaration is a text attributed to Simon Magus which has influenced groups such as the Valentinian and Sethian Gnostics. The text draws from a variety of esoteric schools of thought, especially Platonism. This influence on the text is obvious in its discussion of a sort of metaphysical hierarchy. It states that from one root, the Power, stems the Universal Mind and Great Thought. These aspects combined are regarded as the Father, the creator of all things. The root of Power, also called the Boundless Power, is contained within man. This Boundless Power is referred to as a Fire. As if it wasn’t complex enough, the Fire is twofold in the sense that some of its aspects are perceivable while the others are hidden. The cosmos was generated due to the intelligent nature of these qualities within the Fire. Moreover, the text refers to the six Roots of the Principles of Generation, which are paired off. These consist of Voice and Name, Mind and Thought, and Reason and Reflection. Voice and Name are associated with Sun and Moon. Reason and Reflection correspond to Air and Water, and Simon explains all of these ideas using the creation story in Genesis. He also makes reference to a seventh root which we can presume to be Spirit. According to the text, Fire can also take on male and female forms. This explains the story of Helene as Simon’s first idea. The female form of Thought was caused by angels to create new life using the Fire. These angels, along with lesser metaphysical forces, created material reality. We begin to see the Gnostic idea that the material world is evil in this text as the angels supposedly created it in order to control humanity. Overall, we see heavy Platonic influences in the explanation of the Power and roots that govern the world. These ideas are blended with biblical scripture, and it is not uncommon for Neoplatonism to be blended with biblical tales by theologians. The text clearly illustrates the Fire as a primary generative principle- Simon is the anti-Thales of Miletus. This work inspired an entire sect of Gnosticism named after Simon Magus, the Simonians, along with the Sethians and Valentinians.

His Legacy

Aside from inspiring Gnosticism, Simon became a long-standing enemy of the Catholic Church. The act of “simony” or attempting to buy a service considered to be holy was named after him and prohibited by the Council of Chalcedon during the 5th century. Irenaeus, a Greek bishop, wrote that Simon’s followers practiced magic through incantations and potions. He also discusses Menander, a disciple of Simon and claims that he believed himself to be a Christ-like figure as well. Justin Martyr believed that Simon was an evil force sent to subvert the teachings of Christ and prevent them from being taught.

Conclusion

Simon Magus, whether he’s the father of all heresies or great power of God, is one of the most influential figures in esotericism. To the Christians, his actions warned against blasphemous greed in the Acts of Apostles. Meanwhile, the apocryphal works illustrated him as a much more epic figure. The teachings attributed to him spawned Gnosticism and its various sects, and affirmed his position as an enemy to the Church.

"𝔜𝔬𝔲𝔯 𝔪𝔬𝔫𝔢𝔶 𝔭𝔢𝔯𝔦𝔰𝔥 𝔴𝔦𝔱𝔥 𝔶𝔬𝔲, 𝔟𝔢𝔠𝔞𝔲𝔰𝔢 𝔶𝔬𝔲 𝔱𝔥𝔬𝔲𝔤𝔥𝔱 𝔱𝔥𝔞𝔱 𝔱𝔥𝔢 𝔤𝔦𝔣𝔱 𝔬𝔣 𝔊𝔬𝔡 𝔠𝔬𝔲𝔩𝔡 𝔟𝔢 𝔭𝔲𝔯𝔠𝔥𝔞𝔰𝔢𝔡 𝔴𝔦𝔱𝔥 𝔪𝔬𝔫𝔢𝔶. 𝔜𝔬𝔲 𝔥𝔞𝔳𝔢 𝔫𝔢𝔦𝔱𝔥𝔢𝔯 𝔭𝔞𝔯𝔱 𝔫𝔬𝔯 𝔩𝔬𝔱 𝔦𝔫 𝔱𝔥𝔦𝔰 𝔪𝔞𝔱𝔱𝔢𝔯, 𝔣𝔬𝔯 𝔶𝔬𝔲𝔯 𝔥𝔢𝔞𝔯𝔱 𝔦𝔰 𝔫𝔬𝔱 𝔯𝔦𝔤𝔥𝔱 𝔦𝔫 𝔱𝔥𝔢 𝔰𝔦𝔤𝔥𝔱 𝔬𝔣 𝔊𝔬𝔡” 𝔄𝔠𝔱𝔰 8:20

#esotericism#occultism#gnosticism#gnostic christianity#gnostic gospels#christian history#early christianity

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sexuality in Saxony: The Germanic Perspective on Promiscuity, Love and Lust

One frequently misrepresented aspect of Germanic society is the view on promiscuity, marriage and sex. The attitude of the Germanic peoples as represented in secular culture is vastly different than its historic counterpart. Television and cinema depict the Germanic peoples, especially the Norse, as unchaste, polyamorous and sexual. However, we have a variety of literary sources such as law codes and sagas which highlight the true perspective of these topics at the time. The entertainment industry often focuses on the Viking era (8th-11th centuries), so this post will focus on what we know from this period. It should be noted that the Viking Age is not necessarily the “golden age” of thriving Germanic paganism. Nonetheless, sources show that the society still had very strict moral guidelines in this realm. This post will provide some insight into the authentic attitude of the Germanic peoples in regard to marriage and procreation, as well as how these misrepresentations may have come about.

Tacitus

The Roman historian Tacitus dedicates an entire portion of his work “Germania” to the marital and sexual lives of the Germanic tribes. He wrote this piece during the 1st century when the peoples were still strongly traditionally pagan. This work highlights how strongly valued marriage between one man and woman was. Additionally, both men and women were expected to remain celibate until they become wife and husband. Intimate relations were viewed as having one purpose- procreation. It was also viewed as “extremely wicked” to limit the number of one’s children through abortion. Remaining chaste until marriage allowed the tribe’s youth to maintain their mental and physical strength as well as learn how to turn away from lustful temptations. When a couple was wedded, they were both mature and prepared enough to engage in an activity which may result in an offspring, furthering the legacy of the clan. Prostitution was forbidden and women who had intimate partners outside of marriage were shunned from society as well as ineligible to marry. Adultery was a highly punishable offense and any woman who betrayed her spouse in such a way would have her hair cut off by her husband as well as humiliated in front of the entire village. Tacitus concludes this section by writing “Good morality is more effective in Germany than good laws are elsewhere.”

Marriage

Fathers had a heavy say in who their daughter would marry. Marriages were often times arranged, though the father would have to approve of the young woman’s spouse in order for the marriage to go through anyway. If the woman’s father had passed then another male figure would have to grant approval, such as an uncle or brother. In some cases, a widow who would like to remarry would seek the approval of her son. Both parties were expected to be monogamous and faithful to one another. However, it was not uncommon for men of a higher status to seek concubines and have extramarital relations. A concubine would never be eligible to marry due to the great class difference between her and the man. Women were not permitted to have relations outside of the marriage and this was grounds for divorce. A man would also be punished if he slept with another man’s wife. Some marriages were strategic. Fathers would marry off their daughters to the man he felt would most bring the family economic prosperity or political influence. Despite this, a woman’s opinion on her potential partner was still taken into account and acknowledged. This is clearly an important element to a relationship, especially with concern of longevity, as reflected in the sagas. From Iceland to England, we also have a number of romantic poetic pieces from this time (though English poetry was especially heavily Christianized by this time.) Cultic veneration of love and fertility Gods and Godessses also highlights the importance of romance, sensuality, and family. The sanctity of love is reflected in the mythology, runes, and other literature from that time.

Promiscuity

As mentioned previously, any act of promiscuity brought great consequences. For women, it meant being extremely socially stigmatized, unable to marry, and humiliation. For men of a higher status, it was not encouraged but it happened, as was the case in a variety of cultures. Although prostitution was penalized according to Tacitus, there is no historical documentation of prostitution being an issue at all among the Germanic peoples, so it is unlikely that this was a widespread occurrence. In a saga of a later date, there is a tale of noble women being sold into prostitution under the reign of a new king. Promiscuity was extremely frowned upon primarily due to the view of sex being an act for the purpose of procreation and having a child outside of wedlock was viewed as abhorrent. Additionally, marriage and love was conceived as a divine act between one man and one woman, anything different is transgressing against divine law.

Conclusion

The entertainment industry portrays our ancestors as immoral, lustful hedonists, though sources from that time illustrate the opposite. Tacitus demonstrates the strict societal customs pertaining to relationships and intimacy among the Germanic tribes of the 1st century. Later sources show that much of these ideas were still intact even towards the decline of authentic paganism. To our ancestors, marriage and intimacy were linked while ensuring the success of the tribe. Promiscuity was an anomaly, though strongly punished when it occurred. Literary attestations disprove the modern narrative surrounding such topics.

#paganism#germanic paganism#norse paganism#norse mythology#polytheist#norse polytheism#anglo saxon#esotericism#occultism

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Neoplatonic Influence on Early Christianity: The Cappadocians, Mysticism and Orthodoxy

A particularly fascinating aspect of Christianity is its Neoplatonic characteristics which shaped it during the beginning of its development. Neoplatonism is a philosophy that emerged during the 3rd century with Plotinus, a follower of Plato. It is characterized by monist thought, asserting that all things such as our material reality are emanations of the One, an omnipotent yet obscure force. Although I am not a Christian myself, I would consider myself a Neoplatonist. After all, Neoplatonism has its origins in the philosophy of Hellenic polytheists. However, not all Neoplatonists are polytheists, leading us to today’s exploration of Early Christianity and its philosophy as well as key figures. Neoplatonism may not be as prominent in Christianity as it once was due to the rise of protestantism but we can still see remnants of it in Eastern Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Like all religions, Christianity was heavily shaped by the cultures that it interacted with. Despite it being birthed from Second Temple Judaism, numerous great European thinkers of classical antiquity contributed to its theological growth.

The Nature of God

Of course, the belief in God is at the forefront of any religion. The Neoplatonists and many early Christians are in agreement on several aspects of the nature of God, such as God’s qualities (or lack thereof) and relationship with man. Gregory of Nyssa, a key figure in the creation of Christian mysticism and a saint recognized within Eastern Orthodoxy heavily advanced the notion of God being an unknowable force. The human mind simply cannot begin to understand God while his existence surpassing all earthly characteristics makes him impossible to define. This sentiment is shared by Augustine of Hippo, a Christian theologian that is continually discussed today. I generally don’t share direct quotes in my posts in order to prevent them from being too long, but this excerpt from Augustine’s “On the Nature of Good” is too beautiful to pass up: “For He (God) is so omnipotent, that even out of nothing, that is out of what is absolutely non-existent, He is able to make good things both great and small, both celestial and terrestrial, both spiritual and corporeal.” This description is spot on with the Neoplatonic conception of God with Plotinus arguing that God’s rather simple nature allows him to be the cause and creator of all things. This can be traced back to Plato’s view of God as being eternal and inspiring all life forms through archetypes in the physical realm. To both the Neoplatonists and theologians of Early Christianity, God is inherently good and beautiful yet completely beyond our comprehension. Despite God being seemingly unknowable, we learn a lot about pursuing union with God, or theosis, from a variety of Christian allegorical readings. Pseudo-Dionysius, arguably one of the most famous figures in Christian esotericism, makes an allegory of Moses’s journey to mount Sinai in order to obtain the ten commandments. His journey is interpreted by Pseudo-Dionysius as an internal contemplative one which allows him to level with God. I have briefly discussed such a contemplative journey in my post about theurgy. Specifically, Porphyry advocated for deep contemplation and intellectualization which would purify the individual and allow him to reach communion with God. Gregory of Nyssa claimed that the journey to unify with God is an endless one as God himself is limitless.

Hesychasm

Within Eastern Orthodoxy is the movement of hesychasm, a contemplative mystical practice which can be traced back to the monks of Mount Athos during the 14th century. It is also one of the most overtly Neoplatonic traditions within Christianity. Hesychasm stems from the Greek word ‘hesychia,’ meaning “tranquil” or “still.” As the translations indicate, it is characterized by not only physical stillness but mental stillness as well. Saint Thalassio of Libya argued that Hesychasm allows for the Nous to become free from any impurities which may hinder it from becoming one with the divine. The Nous may be referred to as the intellect and according to Plotinus, it is the cosmological mind as well as existence. It is the reflection of the One. An aspect of physical hesychia is adopting certain positions during prayer or meditation and these positions may further assist in purifying the Nous. It may also refer to avoiding all that is corporeal as well as abstaining from temptations, paralleling Porphyry’s ascetic contemplation. Additionally, the foundation for Hesychasm is developing virtues by way of the commandments. This ties into Pseudo-Dionysius’s allegory in which Moses receiving the ten commandments is more of an introspective quest. This idea is also expounded by Saint Symeon the New Theologian who stated that to acquire the ten commandments is to acquire God.

The Trinity

When I first began reading about Orthodoxy after learning about Neoplatonism, I immediately compared the triad of the two: surely, the Father must correspond to the One, the Son corresponding to the Nous, and the Holy Spirit must correlate to the Soul. Initially, this makes sense when we think of the Father as the origin of all things, the Son being a reflection of the Father (in the way that the Nous may reflect the One) and the Holy Spirit being the essence of the world. However, we must consider the nature of the Trinity. It is important to note that God is worshipped as the Unified Trinity, meaning God is one, but is also distinguishable by various beings. The Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father and the Son. God is equally one as he is three. This disrupts the emanationism of Neoplatonic thought. However, another overlooked similarity may be considered: in the Enneads, Plotinus said to even name the One would draw distinctions upon it. Orthodoxy and Neoplatonism are both characterized by apophatic theology in this way. The Early Christians also borrowed several terms from Neoplatonism and incorporated it into trinitarian writings.

The Cappadocian Fathers

The Cappadocian Fathers were church fathers in Cappadocia, Turkey who furthered the development of Orthodox and trinitarian theology, as well as mysticism. They include Gregory of Nyssa, Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nazianzus. Firstly, Gregory of Nyssa served as the bishop of Cappadocia until his death at the very end of the 4th century. He was especially notable for his writings on God’s unknowable nature and the mystic ascent towards unification. Additionally, some believe that he studied in Athens where Neoplatonism had began to flourish due to Plutarch reestablishing Plato’s Academy. Basil of Caesarea was Gregory of Nyssa’s older brother and was also a bishop during the 4th century. It is recorded that he studied in Athens and went on to produce a number of works on monasticism. Basil also compiled the writings of Origen of Alexandria, a follower of Platonism. Finally, Gregory of Nazianzus was an archbishop and theologian. He contributed heavily to the Orthodox formulation of the trinity. Gregory also studied in Athens where he crossed paths with Julian the Apostate, a Neoplatonist who would later become the emperor and attempt to reestablish paganism. Gregory published “Invectives Against Julian” after the emperor’s rise to power. Macrina the Younger, the sister of both Gregory of Nyssa and Basil of Caesarea, is a saint recognized within Orthodoxy who is known for her ascetic lifestyle.

Conclusion

Much of the theology and developments in Christianity, especially that of Orthodoxy, is heavily rooted in Neoplatonic philosophy as a result of interactions with the Hellenic world. Figures such as Plotinus and Origen certainly guided the thinking of numerous theologians and church authorities. The influence is especially prominent in the conception of God and the trinity while inspiring the practice of mysticism. Finally, The Cappadocian Fathers heavily built upon many of these aspects.

#esotericism#occultism#neoplatonism#platonism#early christianity#orthodox christianity#catholiscism#christian history#paganism

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dark Ages: Apocalypticism, Aeons and Chaos in Paganism

Something that has always fascinated me about the study of religion is the common themes among many of them, especially the various forms of polytheism. Of course, many forms of paganism share the same origin point but it’s nonetheless incredible that so many cultures, some of which have never even interacted, share the same perspectives and similar myths. One of these common themes is that of the cyclic nature of our existence. In paganism, we are constantly going through the process of creation and destruction on a loop. We emerge from a great primeval void, chaos, before transitioning to a period of development and sophistication. In some cases, the process of this cycle is much more distinct, such as the Satya Yuga to the final Kali Yuga in Hinduism. For others, the cycles are less clearly defined. Among the North, our reality was built from the generative substance of the Ginnungagap. Out of this chaos though before its return, the Gods bring order, truth, and beauty. This blog post will explore the significance of birth and rebirth or creation and destruction, the concept of cosmological chaos, as well as “end of the world” events in paganism.

Chaos

The creation of the world is an important aspect to any religion. Germanic paganism explains this from the beginning with the Ginnungagap, or the “yawning void.” This void is first introduced in Gylfaginning, where sparks from Muspellheim enter the void and are then dispersed throughout the many realms of existence. In the Voluspa, we learn that Woden and his brothers built the world from the material of the Ginnungagap. Among the Anglo-Saxons, the word “dwolma” refers to chaos and can be linguistically traced to the Old Saxon word “dwalm” which means confusion. This may illustrate the void possessing the matter which will construct all life. Additionally, some scholars believe that the term Ginnungagap has its origins in Old High German with more mystical connotations. This strongly parallels the perspective of the ancient Egyptians. Like our Germanic ancestors, the Egyptians believed that all life was created from cosmological chaos. Similar to Ginnungagap, this chaos was an empty void; nothingness with the ability to create. They also believed that it was watery, an idea tied to the primeval waters of Nun. Again, water as the prima materia is a widespread philosophy. Aristotle wrote that Thales argued for water being the progenitor of all things. Later, the alchemists claimed that mercury was the prima materia and also referred to it as sacred water. This may be compared to the mercurial force of Woden creating the world from nothingness. I won’t delve into this too much in this post, but it’s clear that ancient polytheists recognized that the potential for all life was conceived out of mystic primordial emptiness by the creator.

The End of the World

If you’re following this blog, then I’m sure you have heard of Ragnarok. Ragnarok, or “the twilight of the Gods”, is essentially the apocalypse of Norse paganism. It should be noted that Ragnarok is specifically attested among the Northern Germanic peoples. Despite this, the return to primordial chaos is certainly rooted in the Indo-European faith, so it is likely that all of the Germanic peoples had some idea of this. Etymologically, the word Ragnarok is very interesting. The first half of the word, “Ragna,” is in reference to the Gods. The second half may be derived from either “Rok” or “Rokkr.” The term “Rok” is striking because it means origin. This may suggest that return to primordial chaos and this will be further propounded by the myth itself. We get the word twilight in the phrase “twilight of the Gods” from “Rokkr.” The word “Ragnarokkr” is found in Lokasenna, though the term “aldarrok” is found in Vafthrudnismal, and this roughly translates to “end of an age.” This also indicates the recognition of metaphysical ages among the Norse. The tale of Ragnarok can be found in Voluspa. Roosters from all over crow and many jotnar begin to approach. The hound Garmr breaks loose. As a result, humanity begins to degrade. It is said that brothers go to war with one another, familial betrayal occurs, as well as lust and violence growing rampant. Ragnarok commences with Heimdall blowing the Gjallarhorn. The Gods then go to battle against the jotnar with the aid of different creatures. The battle results in many of the Gods being killed. Odin is swallowed by the great wolf Fenrir, though is later avenged when his son Vidarr stabs the beast in the heart. Thor slaughters Jormungandr but soon dies from the serpent’s venom. Finally, Freyr is killed by a jotunn called Surtr. The sun blackens and the heavens go up in flames. The Earth is then submerged beneath the sea. As a result of the battle, the Earth soon remerges from the sea and the surviving Gods congregate together. The Earth begins to revive as vegetation grows. We also learn that the brothers Hodr and Baldr will return along with Njord. Two humans, Lif and Lifthrasir will have survived Ragnarok and repopulate the Earth. Again, we can draw parallels between Ragnarok and the return of the primordial waters in Egypt. Chaos will return after the mighty serpent Apophis defeats the sun God Ra, swallowing up the Earth while the creator grows too old and weary to reinstate order. This serpent is associated with natural disasters as well as general disorder and we come across many myths in which the Gods must reckon with Apophis. Moreover, Ra must encounter Apophis every night during his journey to Duat, the underworld. Apophis is extremely similar to the serpent Jormungandr who plays an important part in Ragnarok and the myths as a whole. This serpent is also associated with the water and engulfs the Earth by biting its tail, much like Apophis who swallows it whole. The Gods, specifically Thunor, are frequently disturbed by this serpent. Most importantly, Ragnarok or any apocalyptic event in paganism does not depict the end of the world, but rather a return to the beginning. Woden created the Earth using the body of the jotunn Ymir, meanwhile many of the Gods die due to the jotnar. There is no end- only birth, death and rebirth.

The Yugas

One cannot discuss apocalypticism without talking about the Yugas, specifically Kali Yuga. It may seem that discussing Hinduism does not fit in with this article or this account’s theme as a whole but seeing that it is the Indo in Indo-European, as well as its comparison to metaphysical ages, I feel it’s still important to mention. The four Yugas all together span 4,320,000 years. Each Yuga is a multiple of the other, with the longest being Satya Yuga at 1.7 million years and the shortest being Kali Yuga at 432,000 years. There’s a lot of debate among Hindu thinkers on which Yuga we’re in now, but many believe that we are in the Kali Yuga. If I may interject my opinion, I believe they likely aren’t far off when you take a look at the world. Satya Yuga is often referred to as the Golden Age and overall the greatest time for human civilization. Truth, religiosity, morality, and beauty are at its peak. The first manifestation of Vishnu appears with Mastyadeva. Mastyadeva must battle the demon Hayagriva who attempts to steal the Vedas from Brahma. The Vedas are crucial because with the degradation of the Vedas follows the degradation of civilization. This decline begins to show during Treta Yuga. Truth and religiosity slowly begins to slip. Some humans grow physically weaker while some elevate to almost a godlike status due to enlightenment. Dwapar Yuga, also called the Bronze Age, shows an increase in materialism, violence and lust. The forces of good and evil are at a tie. The Vedas are divided into four. This is also when Krishna recites the Bhagavad Gita which is very important to the coming age. Kali Yuga is the Iron Age. It is the last age before the cycle repeats. The family unit deteriorates, humanity is divided and the Earth is polluted. Out of Kali Yuga, the next Satya Yuga emerges and the continual cycle repeats once more.

Conclusion

The cycle of life, death and rebirth are central to any form of paganism. Across the globe, many different cultures have their own conceptions and myths revolving around this cycle that share common themes and principles. Whether it be the Ginnungagap or primordial waters of Nun, all things come from a dark cosmic emptiness. Moreover, we all must return to that place of nothingness. Among the Norse, Ragnarok resets the universe while the world’s order slowly disintegrates due to an aging creator according to the Egyptians. Perhaps the most popular example of this life-death-rebirth loop is that of the Yugas among Hinduism. From East to West, we are chained to this mystical sequence.

#esotericism#germanic paganism#paganism#norse paganism#occultism#anglo saxon#hinduism#kali yuga#ancient egypt#egyptology

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Germanic Paganism Sources

I can’t list these sources without first going through a million different caveats. I’m going to keep this introduction brief due to the length of this post, but be aware that these sources have been subjected to Christianization, speculation, mistranslation, etc. Many of these sources were copied down by Christian authors who may have altered the truth in order to fit their perspective. Some may have vague terms or phrases that we can no longer understand because they existed in an entirely new context. Essentially, approach all of these texts from a speculative and critical lens. This doesn’t mean we can’t decipher the truth. We can decipher the truth by comparing texts from the same time, countries, etc with each other and finding the common threads. Pairing these attestations with archaeological records is also immensely helpful and I hope to compile a list of archaeological records some time in the future. You can find many free records and studies by simply typing, for example, “anglo-saxon burials archaeological excavations.”

This list consists of records of various Germanic peoples, histories, as well as semi-legendary sagas and poetry. By exploring a variety of texts instead of just ethnographic works, we can understand the history, culture, customs, traditions, values, and more. These are all crucial in approaching paganism with the goal of accurate and thorough understanding. I wanted to focus primarily on sources from close to the pagan period, but I have also included current sources in the grimoires and runes section. For the contemporary study of Germanic paganism, I always recommend Stephen Flowers!

Happy researching

The Eddas

https://www.norron-mytologi.info/diverse/ThorpeThePoeticEdda.pdf

http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/EDDArestr.pdf

England

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/657/pg657-images.html

https://ia804700.us.archive.org/31/items/exeterbookanthol00goll/exeterbookanthol00goll.pdf

https://langeslag.uni-goettingen.de/oddities/texts/Aecerbot.pdf

https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/03d/0627-0735,_Beda_Venerabilis,_Ecclesiastical_History_Of_England,_EN.pdf

https://www.ragweedforge.com/rpae.html (this website also has the norwegian and icelandic rune poems)

https://www.dvusd.org/cms/lib/AZ01901092/Centricity/Domain/2897/beowulf_heaney.pdf

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/ascp/

https://ia601403.us.archive.org/12/items/bede-the-reckoning-of-time-2012/Bede%20-%20The%20Reckoning%20of%20Time%20%282012%29.pdf

Germany

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/nblng/index.htm

https://www.germanicmythology.com/works/merseburgcharms.html

Frisia

https://www.liturgies.net/saints/willibrord/alcuin.htm

Denmark

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/saxo/index.htm

Iceland

https://archive.org/details/booksettlementi00ellwgoog/page/n4/mode/2up

Finland

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/kveng/kvrune01.htm

Germania

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7524/7524-h/7524-h.htm

The Sagas

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/598/598-h/598-h.htm

http://vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Heimskringla%20II.pdf

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/heim/05hakon.htm

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/vlsng/index.htm

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/egil/index.htm

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/ice/is3/index.htm

https://sagadb.org/files/pdf/eyrbyggja_saga.en.pdf

https://sagadb.org/brennu-njals_saga.en

Grimoires

https://archive.org/details/GaldrabokAnIcelandicGrimoire1

https://handrit.is/manuscript/view/is/IB04-0383/9#page/3v/mode/2up

https://galdrastafir.com/#vegvisir

Runes

https://www.esonet.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Futhark-A-Handbook-of-Rune-Magic-Edred-Thorsson-1984.pdf

*Due to link limits on tumblr, i cannot link all of these. Please paste them into your browser.

*Also, sadly I could not find some of the sources I wanted for free. I will continue to update this post with new links and it will be pinned to my profile always!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood for Wotan: Animal & Human Sacrifice

As Christianity spread throughout Northern Europe, a crucial component to the culture and religion of the Germanic tribes was stomped out: sacrifice. Moreover, this practice became immensely demonized during the medieval period and continues to be so today. Sacrifice was no longer an act performed out of love and reverence for the divine, but rather an act demanded by a merciless, savage God who’s insatiable appetite could only be appeased with mortal flesh. In today’s post, I will be disputing some misconceptions and illustrating what sacrifice actually looked like among the Anglo-Saxons and other Germanic peoples of pre-Christian Europe.

Animal Sacrifice

Sacrifice was so prominent among the Anglo-Saxons that Pope Gregory specifically mentioned it (along with human sacrifice, but more on that later…) in a letter to Priest Mellitus who was sent to preach to them during the 6th century. In this letter, he detailed the slaughtering of oxen and the consumption of their meat in worship to the Gods. This description was actually not too far off, excluding Gregory referring to the Gods as the devil. Firstly, Bede explicitly stated that the Anglo-Saxons made sacrifices during Hrethmonath (March) and Blodmonath (December), however it is very likely that they sacrificed all throughout the year, such as during Eostremonath (April), Modranecht (Mother’s Night) and Yule. Snorri also noted that the Germanic peoples would make sacrifices during the beginning of winter, the middle of winter, and during the summer. Once more according to Bede, the Anglo-Saxons would slaughter cattle during Blodmonath. Cows were a particularly common animal to sacrifice. For instance, a number of cattle skulls have been uncovered in Iceland. Analysis of the remains indicate that they were beheaded with a type of axe, leaving some scholars to speculate that this method of killing was used due to it producing a large stream of blood in a theatrical fashion. Furthermore, the Germanic peoples were also known to collect the blood of sacrificed animals. Axes have been uncovered at several Anglo-Saxon settlements and it is very likely that they also used the axes for this purpose. An ox’s head has also been excavated in Cambridgeshire where it had been buried in a seemingly ritualistic fashion. Sacrifices could take place in a number of locations in dedication to a number of different beings. Among the Anglo-Saxons, they were most commonly performed in sacred groves, burial mounds, and in halls. In some cases, they took place at temples. They were also most often dedicated to the Gods, but one may also carry out a sacrifice for the different spirits such as the land wights or house wights. There was always a distinct reason behind these sacrifices. Haakon the Good’s Saga describes a sacrifice in which toasts were made to Odin for power and Njord and Freyja for peace. I highly recommend this saga for further readings on sacrifices as it truly describes it wonderfully and sagas are generally always an excellent source. Sacrifices were initiated by a variety of different prominent figures within the community in various parts of Northern Europe. It was customary for a king or jarl to host the sacrifice, though priests may have also led them. Upon slaughtering the animal, the priest would redden his golden arm ring with the blood of the sacrificed animal. As previously stated, this blood was collected and referred to as hlaut. Throughout various texts, you may encounter the word hlaut in conjunction with another word, such as hlaut-staves, or bundles of twigs that would be used for sprinkling this blood around the altar and on participants. The blood may have also been drank during the feast of the animal’s flesh. After the sacrifice and other festivities, the animal’s skull may have been displayed at whatever hall or location the sacrifice took place at. One of these such halls is Hofstadir in Iceland where over 20 skulls were excavated. The unique removal of certain parts of the skull as well as the location of erosion suggests the skulls could have been arranged outside of the hall for display purposes. An animal could have also been sacrificed and buried in its entirety such as in the case of accompanying the dead into the afterlife and there are many excavations similar to this.

Human Sacrifice

There is actually little to no evidence that the Anglo-Saxons ever practiced human sacrifice. The little evidence could perhaps be ritualistic human burials and the fact that human sacrifice is documented amongst the Germanic peoples. Most notably, Tacitus wrote of human sacrifice among the Semnones during the 1st century. He also noted that Mercury, or Woden, is whom they most often made their sacrifices to. Additionally, there is literary documentation of the Norse-Rus peoples sacrificing the most prized slave girl during the burial of her master. There are many, many other attestations of human sacrifices among the various Germanic tribes, but there are also some archaeological findings that may provide some insight into the subject. The bog bodies of Denmark are the first thing to come to mind with many scholars believing that the rather brutally injured bodies uncovered belong to individuals who were sacrificed. Despite no literary records confirming the existence of human sacrifice among the Anglo-Saxons, there are several rather peculiar burials which do appear similar to the human sacrifice recorded among other tribes. The first of which somewhat aligns with the documentation of the Norse-Rus burying a slave girl with her master. In Surrey, a grave containing the remains of two men and a woman were found. It is questioned whether or not this was a slave girl, or more broadly, if this woman was killed as a sacrifice to the men due to her body being positioned in an intentional downward facing direction. Sutton Hoo is one of the most important historical sites of Anglo-Saxon England, and it is even debated whether some of the bodies located there were hanged as a sacrifice. We cannot definitively say that the Anglo-Saxons practiced human sacrifice, though we have great evidence that many other tribes did. Finally, it’s important to note this: most often, these individuals who were sacrificed were not necessarily sacrificed against their will. It is well known that the Germanic peoples did sacrifice prisoners, but many viewed being sacrificed as a great honor and gave themselves up to the Gods. The idea that our ancestors sacrificed one another out of any reason besides love and reverence for the Gods is false.

Goals

There is a very clear answer as to why our ancestors performed sacrifices. When researching sacrifice, you begin to notice that the discussion or records of sacrifices can most often be placed into two camps: those out of necessity and those out of worship. Also, it isn’t necessarily black and white as these purposes will overlap in almost all cases. It is well known that the Germanic tribes would initiate a sacrifice for a good harvest, or as mentioned previously, victory granted by one of the Gods. However, a large problem in the contemporary study of paganism is too much of an emphasis on the Gods. Our ancestors venerated a plethora of other beings and likely viewed themselves as interacting more closely in day-to-day life with them. We had briefly discussed the sacrifices made to land and house wights, though they were also made to one’s ancestors and any topographical feature which may have been significant to the community. By reading up on these various entities, it becomes more understandable why sacrifices were made to them and you can learn more about these beings here. To put it simply, the Germanic peoples loved the Gods. In some instances, they wished to gain a favor for the Gods by doing a favor for them. In others, they simply wished to express that love.

Conclusion

Although often highly misrepresented in the secular world, sacrifice was a beautiful rite performed by the Germanic tribes out of love for the Gods. They were dedicated to both the Gods, deceased ancestors and other spirits, while occurring for a variety of different purposes which were important to the tribe. Human sacrifice is also recorded among many of these tribes, most often killing a prisoner of war or a volunteer. Moreover, there was always a thought-out goal of the sacrifice whether it be crop fertility or to express one’s admiration to the Gods, with the two frequently blending. Sacrifice is a ceremonial and deeply metaphysical interaction with the divine.

#germanic paganism#anglo saxon#paganism#norse paganism#europe#metaphyics#esotericism#animal sacrifice#human sacrifice#occultism#religion

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Devotion to the One: Theurgy, Neoplatonism & Ritual

Theurgy is derived from the Greek words “theos” meaning “God” and “ergos” meaning “working”, resulting in “God-working.” The word was first used in the Neoplatonist text the “Chaldean Oracles” and refers to the process of working through the several divine emanations in order to achieve henosis, or unity with the One. I personally find theurgy to be an extremely fascinating though equally as complex topic, and I aim to explain it’s origins, philosophy, and practical application in this blog post.

Origins

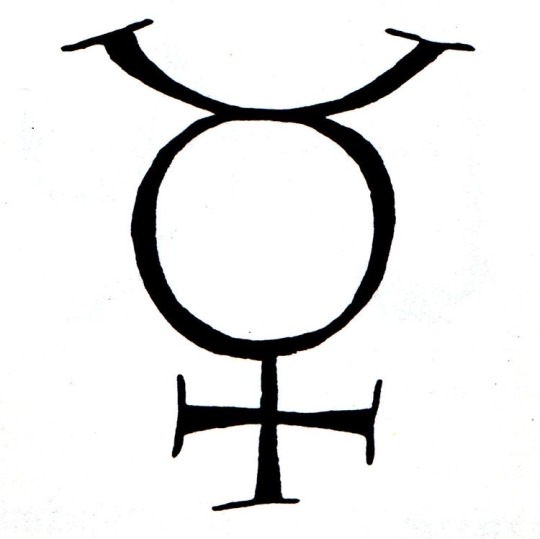

Theurgy itself is rooted in early Neoplatonism and each emanation is described by its founder, Plotinus. The One, also referred to as God or in some cases the Godhead, is the origin point of all things. A popular neoplatonist symbol is that of a dot encircled by a larger circle- the One is that dot and the larger circle is all other multitudes of emanation. The one is inherently good and beautiful and this goodness may descend through each level. The Nous, also referred to as the Intellect, is the conscience of the cosmos, and the Soul may refer to that of the individual or the universe. The Soul is the unified life-form of all living things. Theurgy was an essential element of the Hellenic faith, though can also be found in various sects of Christianity as well as Gnosticism.

Philosophy, Porphyry vs. Iamblichus

Perhaps the most prominent figure contributing to the practice and philosophy of theurgy is the Syrian philosopher Iamblichus. He was a Neoplatonist, although he differed from earlier Platonic thinkers as he emphasized the necessity of ritual for union with the divine. Porphyry, another Neoplatonist philosopher whom Iamblichus studied under, argued for a more ascetic approach and the salvation of the soul. He also believed that unification with the One was a contemplative, introspective process, and that ritual was a distraction from this goal. Porphyry along with Plotinus felt that material was impure and could essentially corrupt the immaterial. Plotinus also stated that matter was an ontological evil. Matter was a product of the Soul which generated all life, and through the action of creation, generated matter as well. Iamblichus adopts a somewhat different approach to theurgy, arguing against Porphyry’s view of solitude and intellectualization as being what motivates the outcome of theurgy while highlighting the practical use of rituals. Furthermore, he opposes Porphyry’s denunciation of the Hellenic and Egyptian rites, which he writes of extensively in his work “On the Mysteries of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and Assyrians.” Iamblichus reasoned that one can reach this synthesis with God by purifying oneself and navigating the various multitudes of emanation through devotional acts towards the divine and the use of symbols, characterizing this process as being cosmogonic and anagogic in nature.

Ritual