#neoplatonism

Text

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola was an odd duck. As a young scholar, he allegedly mastered Greek and Latin by the age of 13. In 1484 he met Marsillio Ficino and fabulously wealthy italian banker Lorenzo De Medici, and promptly charmed the both of them, roping tutelage from the former, and patronage from the latter. During his time in Florence he would write the 900 Theses, a text which claimed that not only were Plato and Aristotle reconcilable, but that they were compatible with Christianity. He was quite confident in the strength of his work. In fact, he was so confident that he ended the 900 Theses with the following announcement:

“THE CONCLUSIONS will not be disputed until after the Epiphany. In the meantime they will be published in all Italian universities. And if any philosopher or theologian, even from the ends of Italy, wishes to come to Rome for the sake of debating, his lord the disputer promises to pay the travel expenses from his own funds.”

His plan was to travel to Rome, have the theses published, hold a conference defending his work, defeat every challenger with Facts and Logic, and ride the wave of success to theological glory. On his way to Rome he stopped in the town of Arezzo, had an affair with the wife of one of Lorenzo de Medici’s cousins, attempted to run away with her, got beaten nearly to death, thrown in prison, and then released by order of Lorenzo himself. While recovering from his wounds, he became obsessed with magic.

More Renaissance Magic on Patreon Today

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

TIL from a podcast featuring historian and Byzantine archaeologist Yannis Theoharis:

Athens was one of the most religiously conservative cities of the Byzantine Empire. It adhered to the ancient Greek religion for longer than most other areas. Contrary to popular belief, its eventual conversion to Christianity did not happen violently. Christianity was getting more and more ground amongst the believers progressively. Meanwhile, the ancient temples and shrines were progressively emptying but as long as there were believers they were functioning properly and had guards and went through restoration works and all, as stated by Neoplatonic philosopher Proklos (with the exception of nude sculptures which had been destroyed already by proto-Christians). The historian also claims the conversion of the temples to churches happened later than what was previously believed, around the 7th-9th centuries. As the vast majority of the population had eventually converted to Christianity, the temples were left abandoned. The empire ordered their conversion to churches so that funding their preservation could be justified. Furthermore, there wasn’t as much of violent banning of ancient schools as it was thought. Justinian did not ban the function of the Neoplatonic school in Athens but ceased the state funding unless the school accepted to add Christian theology to its curriculum. The Neoplatonic school refused but it was not banned. It kept functioning using its own private funds until this wasn’t enough and the school had to close. Evidence for this is that it is documented that the school functioned for several decades or more than a century (don’t remember exactly) after Justinian’s imperial command, which was previously viewed as an immediate or violent shutdown. Meanwhile, the Neoplatonic school in Alexandria (in Egypt) agreed to add Christian theology to its curriculum and it kept functioning undisturbed until the 7th century and the Arab conquest.

Also, he has more insight into the similarities observed between Eastern / Greek and even all Orthodoxy and the Ancient Greek religion, such as idol / icon worship, lesser deity / saint worship, virgin female deity / super saint worship, patron gods / saints etc He says there was an interesting cycle of Christianised Hellenism followed by Hellenized Christianity. Some of these elements of Christian Orthodoxy were emphasized more than in the early years of Proto-Christianity or even exaggerated by the Byzantine Greek Christians in order to attract the pagan Greeks and make them understand more easily the philosophy of the new religion and find common ground between them. It worked.

Lastly, he disputed the dated assumptions that the Visigoth king Alaric I was assisted by monks to destroy Athens during his invasion in 396. This was falsely concluded because in documents it was found that Alaric was accompanied by men clad in black. Theoharis says these were actually Thracian soldiers (Alaric indeed fared long in Thrace and the Thracians were by large mercenaries) and supports it is very unlikely based on historical evidence of the time that Athenian or Greek Christians would collaborate with a Visigoth invader to help him destroy historical areas of Athens, even if they were pagan.

These are the most important bits from memory, I am linking the podcast here, it is in Greek.

#Greece#Europe#history#Greek history#Byzantine history#Christian orthodoxy#Ancient Greek religion#Greek orthodoxy#Eastern Orthodoxy#Byzantine empire#eastern Roman Empire#justinian#Alaric I#proklos#neoplatonism#Athens#attica#central Greece#Sterea Hellas#mainland

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apollo and the Shepherd Daphnis, Pietro Perugino, 1475-1500

#art history#art#italian art#aesthethic#painting#ancient greece#greek mythology#15th century#rinascimento#arcadia#apollo#shepherd#daphnis#apollo and daphnis#louvre#gay art#homoerotic art#flute#couples#pietro perugino#queer history#lgbt history#neoplatonism

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mystic Egyptian Polytheism Resource List

Because I wanted to do a little more digging into the philosophy elements explored in Mahmoud's book, I took the time tonight to pull together the recommended reading he listed toward the end of each chapter. The notes included are his own.

MEP discusses Pharaonic Egypt and Hellenistic Egypt, and thus some of these sources are relevant to Hellenic polytheists (hence me intruding in those tags)!

Note: extremely long text post under this read more.

What Are The Gods And The Myths?

ψ Jeremy Naydler’s Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It dives deep into how the ancients envisioned the gods and proposes how the various Egyptian cosmologies can be reconciled.

ψ Jan Assmann’s Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism focuses on New Kingdom theology by analyzing and comparing religious literature. Assmann fleshes out a kind of “monistic polytheism,” as well as a robust culture of personal piety that is reflected most prominently in the religious literature of this period. He shows how New Kingdom religious thought was an antecedent to concepts in Hermeticism and Neoplatonism.

ψ Moustafa Gadalla’s Egyptian Divinities: The All Who Are The One provides a modern Egyptian analysis of the gods, including reviews of the most significant deities. Although Gadalla is not an academic, his insights and contributions as a native Egyptian Muslim with sympathies towards the ancient religion are valuable.

How to Think like an Egyptian

ψ Jan Assmann’s The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It illuminates Egyptian theology by exploring their ideals, values, mentalities, belief systems, and aspirations from the Old Kingdom period to the Ptolemaic period.

ψ Garth Fowden’s The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind identifies the Egyptian character of religion and wisdom in late antiquity and provides a cultural and historical context to the Hermetica, a collection of Greco-Egyptian religious texts.

ψ Christian Bull’s The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom provides a rich assessment of the Egyptian religious landscape at the end of widespread polytheism in Egypt and how it came to interact with and be codified in Greek schools of thought and their writings.

How To Think Like A Neoplatonist

Radek Chlup’s Proclus: An Introduction is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It addresses the Neoplatonic system of Proclus but gives an excellent overview of Neoplatonism generally. It contains many valuable graphics and charts that help illustrate the main ideas within Neoplatonism.

ψ John Opsopaus’ The Secret Texts of Hellenic Polytheism: A Practical Guide to the Restored Pagan Religion of George Gemistos Plethon succinctly addresses several concepts in Neoplatonism from the point of view of Gemistos Plethon, a crypto-polytheist who lived during the final years of the Byzantine Empire. It provides insight into the practical application of Neoplatonism to ritual and religion.

ψ Algis Uzdavinys’ Philosophy as a Rite of Rebirth: From Ancient Egypt to Neoplatonism draws connections between theological concepts and practices in Ancient Egypt to those represented in the writings and practices of the Neoplatonists.

What Is “Theurgy,” And How Do You Make A Prayer “Theurgical?”

ψ Jeffrey Kupperman’s Living Theurgy: A Course in Iamblichus’ Philosophy, Theology and Theurgy is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It is a practical guide on theurgy, complete with straightforward explanations of theurgical concepts and contemplative exercises for practice.

ψ Gregory Shaw’s Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus demonstrates how Iamblichus used religious ritual as the primary tool of the soul’s ascent towards God. He lays out how Iamblichus proposed using rites to achieve henosis.

ψ Algis Uzdavinys’ Philosophy and Theurgy in Late Antiquity explores the various ways theurgy operated in the prime of its widespread usage. He focuses mainly on temple rites and how theurgy helped translate them into personal piety rituals.

What Is “Demiurgy,” And How Do I Do Devotional, “Demiurgical” Acts?

ψ Shannon Grimes’ Becoming Gold: Zosimos of Panopolis and the Alchemical Arts in Roman Egypt is my top text recommendation for further exploration of this topic. It constitutes an in-depth look at Zosimos—an Egyptian Hermetic priest, scribe, metallurgist, and alchemist. It explores alchemy (ancient chemistry and metallurgy) as material rites of the soul’s ascent. She shows how Zosimos believed that partaking in these practical arts produced divine realities and spiritual advancements.

ψ Alison M. Robert’s Hathor���s Alchemy: The Ancient Egyptian Roots of the Hermetic Art delves deep temple inscriptions and corresponding religious literature from the Pharaonic period and demonstrates them as premises for alchemy. These texts “alchemize” the “body” of the temple, offering a model for the “alchemizing” of the self.

ψ A.J. Arberry’s translation of Farid al-Din Attar’s Muslim Saints and

Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat al-Auliya contains a chapter on the Egyptian Sufi saint Dhul-Nun al-Misri (sometimes rendered as Dho‘l-Nun al-Mesri). He is regarded as an alchemist, thaumaturge, and master of Egyptian hieroglyphics. It contains apocryphal stories of his ascetic and mystic life as a way of “living demiurgically.” It is an insightful glimpse into how the Ancient Egyptian arts continued into new religious paradigms long after polytheism was no longer widespread in Egypt.

Further Reading

Contemporary Works

Assmann, Jan. 1995. Egyptian Solar Religion in the New Kingdom: Re, Amun and the Crisis of Polytheism. Translated by Anthony Alcock. Kegan Paul International.

Assmann, Jan. 2003. The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press.

Bull, Christian H. 2019. The Tradition of Hermes Trismegistus: The Egyptian Priestly Figure as a Teacher of Hellenized Wisdom. Brill.

Chlup, Radek. 2012. Proclus: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Escolano-Poveda, Marina. 2008. The Egyptian Priests of the Graeco-Roman Period. Brill.

Fowden, Garth. 1986. The Egyptian Hermes: A Historical Approach to the Late Pagan Mind. Cambridge University Press.

Freke, Tim, and Peter Gandy. 2008. The Hermetica: The Lost Wisdom of the Pharaohs. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

Gadalla, Moustafa. 2001. Egyptian Divinities: The All Who Are The One. Tehuti Research Foundation.

Grimes, Shannon. 2019. Becoming Gold: Zosimos of Panopolis and the Alchemical Arts in Roman Egypt. Princeton University Press.

Jackson, Howard. 2017. “A New Proposal for the Origin of the Hermetic God Poimandres.” Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism 17 (2): 193-212.

Kupperman, Jeffrey. 2014. Living Theurgy: A Course in Iamblichus’ Philosophy, Theology and Theurgy. Avalonia.

Mierzwicki, Tony. 2011. Graeco-Egyptian Magick: Everyday Empowerment. Llewellyn Publications.

Naydler, Jeremy. 1996. Temple of the Cosmos: The Ancient Egyptian Experience of the Sacred. Inner Traditions.

Opsopaus, J. 2006. The Secret Texts of Hellenic Polytheism: A Practical Guide to the Restored Pagan Religion of George Gemistos Plethon. New York: Llewellyn Publications.

Roberts, Alison M. 2019. Hathor’s Alchemy: The Ancient Egyptian Roots of the Hermetic Art. Northgate Publishers.

Shaw, Gregory. 1995. Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus. 2nd ed. Angelico Press.

Snape, Steven. 2014. The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

Uzdavinys, Algis. 1995. Philosophy and Theurgy in Late Antiquity. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

Uzdavinys, Algis. 2008. Philosophy as a Rite of Rebirth: From Ancient Egypt to Neoplatonism. Lindisfarne Books.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2000. The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

Ancient Sources in Translation

Attar, Farid al-Din. 1966. Muslim Saints and Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat alAuliya. Translated by A.J. Arberry. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Betz, Hans Dieter. 1992. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Copenhaver, Brian P. 1995. Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, with Notes and Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guthrie, Kenneth. 1988. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library: An Anthology of Ancient Writings which Relate to Pythagoras and Pythagorean Philosophy. Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press.

Iamblichus. 1988. The Theology of Arithmetic. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Grand Rapids, MI: Phanes Press.

Iamblichus. 2003. Iamblichus: On the Mysteries. Translated by Clarke, E., Dillon, J. M., & Hershbell, J. P. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Iamblichus. 2008. The Life of Pythagoras (Abridged). Translated by Thomas Taylor. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing.

Lichtheim, Miriam. 1973-1980. Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volumes I-III. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Litwa, M. David. 2018. Hermetica II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Majercik, Ruth. 1989. The Chaldean Oracles: Text, Translation, and Commentary. Leiden: Brill.

Plato. 1997. Plato: Complete Works. Edited by John M. Cooper and D. S. Hutchinson. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Plotinus. 1984-1988. The Enneads. Volumes 1-7. Translated by A.H. Armstrong. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Van der Horst, Pieter Willem. 1984. The Fragments of Chaeremon, Egyptian Priest and Stoic Philosopher. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

#mystic egyptian polytheism#resource list#philosophy#neoplatonism#egyptian polytheism#hellenic polytheism#hermeticism

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Current nonfiction reading is Neoplatonism by Pauliina Remes, part of Acumen's very fine Ancient Philosophies series. I freely admit that I find Neoplatonism difficult, at least compared to, say, Stoicism or Epicureanism, but Remes does a superb job of laying out the key issues the Neoplatonists faced--the ontological hierarchy, intellection vs. sensory perception, will and selfhood, etc. She also pays keen attention to the historical development of the school and demonstrates the evolving nature of Neoplatonist thought, as scholars such as Proclus and Damascius responded both to Plato himself and to the gauntlet laid down by Plotinus and Porphyry. And all this within a span of just over 200 pages (!) As a jumping-off point for further study of the topic, you'd be hard-pressed to do better.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The philosopher’s task is to overcome the human bondage to the physical realm by moral and intellectual self-discipline and purification, and to turn inward to a gradual ascent back to the Absolute. The final moment of illumination transcends knowledge in any usual sense, and cannot be defined or described, for it is based on an overcoming of the subject-object dichotomy between the seeker and the goal: it is a consummation of contemplative desire that unites the philosopher with the One.

Richard Tarnas, The Passion of the Western Mind

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It would be best to sum up the spirit of Gnosticism thus: extending over more than two centuries, it gathers up all the ideas that lingered about the period in order to form an outrageous Christianity, woven from Oriental religions and Greek mythology. But that this heresy was Christian we cannot doubt by a certain raucous resonance that runs through it. It is evil that obsessed the Gnostics. They are all pessimists regarding the world. It is with great ardor that they address a God whom they nevertheless make inaccessible. But Christianity draws from this emotion, incalculable in the face of the divinity, the idea of His omnipotence and of man's nothingness. Gnosticism sees in knowledge a means of salvation. In that it is Greek, because it wants that which illuminates to restore at the same time. What it develops is a Greek theory of grace.

Historically, Gnosticism reveals to Christianity the path not to follow. It is because of its excesses that Tertullian and Tatian check Christianity in its march toward the Mediterranean. It is, to a certain extent, because of Gnosticism that Christian thought will take from the Greeks only their formulas and their structures of thought - not their sentimental postulates, which are neither reducible to Evangelical thought nor capable of being juxtaposed to it but without the slightest coherence. Perhaps it is already clear that Christianity, introduced into the Greco-Roman world at the end of the first century, did not make any decisive development until the milieu of the third century. We understand as well the importance we have accorded to the Gnostic doctrines regarding the evolution we want to recount. Gnosticism shows us one of the Greco-Christian combinations that were possible. It marks an important stage, an experience we could not pass over in silence.” - Albert Camus, ‘Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism’ (1936) [p. 86, 87)

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

As someone fascinated by Roman history, I asked for this book last Christmas and I must say that I wasn't disappointed. The story of the philosopher emperor Julian is told in a detailed and entertaining way. To anyone interested in late antiquity and the history of religion, or simply by the tale of a man of high ideals who came to rule a troubled world, I highly recommend this book.

#ancient rome#roman empire#late antiquity#julian the apostate#hellenic polytheism#christianity#against the odds#neoplatonism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chaldean Oracle Verse 147, Gate of Man and Gate of Immortals, Cancer/Capricorn, and Daniel.

If you speak to me often, you will perceive everything in lion-form. For neither does the curved mass of heaven appear then nor do the stars shine. The light of the moon is hidden, and the earth is not firmly secured, but everything is seen by flashes of lightning.

If you often invoke me all things will appear to you to be a lion. For neither will the convex bulk of heaven then be visible; the stars will not shine; the light of the moon will be concealed; the earth will not stand firm; but all things will be seen in thunder.

Disclaimer: This post is part of my original line of posts of my own blog where I...you guessed I ramble about stuff even if I am wrong because why not. Take it with a grain of salt AND if you actually know what the verse actually mean and want to correct me please go ahead.

In the sixth hour you have the form of a lion; your name is ΒΑΙ ΣΟΛΒΑΙ (BAI SOLBAI), the ruler of time.

"the light of the moon is hidden" reference to Cancer.

Summer tropic is in Cancer, and the winter tropic in Capricorn. And since Cancer is nearest to us, it is very properly attributed to the Moon, which is the nearest of all the heavenly bodies to the earth. But as the southern pole, by its great distance, is invisible to us, hence Capricorn is attributed to Kronos (Saturn)

in On the Cave of the Nymphs by Porphyry:

Homer was not satisfied with saying that it had two gates, but adds that one of the gates was turned towards the north, but the other which was more divine, to the south. He also says that the northern gate was pervious to descent, but does not indicate whether this was also the case with the southern gate. For of this, he only says, "It is inaccessible to men, but it is the path of the immortals

You can kinda see the similar gnosis/insight people have to associate Helios with Hecate in that sense if you attribute this oracle line to Hecate like Psellus did.

Porphyry clearly states that the signs from Cancer to Capricorn, which constitute the descent of a soul into a body, are situated in the following order: and the first of these is Leo, which is the house of Helios (the Sun); afterwards Virgo, which is the house of Hermes (Mercury); Libra, the house of Aphrodite (Venus); Scorpius, of Ares (Mars); Sagittarius, of Zeus (Jupiter); and Capricornus, of Kronos (Saturn).

“But from Capricorn,” he adds, the ascent is naturally “in an inverse order.” That is, in an inverse order on the opposing curve of the wheel of the zodiac. Aquarius is attributed to Kronos; Pisces, to Zeus; Aries, to Ares; Taurus, to Aphrodite; Gemini, to Hermes; and in the last place Cancer to the Selene (the Moon), only upon the soul’s descent into a body is the sun’s sign (Leo) encountered.

This is basically the whole dichotomy of Metatron and Sandalphon, because you get that similar connection between Malkuth/Kether and Enoch/Elijah, what I see personally is this hinting toward merkavah and Hekhalot literature where you descened to the chariot/merkavah. In a way I can definitely say the hints are astrologically coded but the practice itself isn't astrological strictly.

the whole descent into mysteries is in that verse, the curved mass of heaven nor do star shine IS THE LITERAL HEAVEN if you scry them or work through the gates of merkavah. The light of the moon is hidden and earth is not secured because you're reaching a place that's not "here" in the objective sense of the world, everything is seen by flashes of lighting is very apt way to describe how you actually see stuff there! almost very reminiscent of dreamy visions where everything is remembered haphazardly !

In summary the astrological hints are just symbolic not practically invalid but not restrictive into it, since the sun/lion-form is the first thing that come after Saturn in descent and last thing before Moon then you can see the hint THERE. It's not lion, but the sun which when it shine so brightly it will hide the rays of the moon, you can see that the sun is both what we can fall into and we can rise through.

I definitely felt very excited to share my hot take about this oracle line, because it is rather very related to some other blogs that I did work with.

Now...dare I say that these lion forms is what Daniel saw in the pit when he got thrown? notice how Daniel immediately start having visions after the lion pits from Daniel 6 to 7, it is an immediate jump.

Daniel in the Lion's Den c1615 Peter Paul Rubens

#occult#witchblr#invocation#prayer#ritual#magic#theurgy#Chaldean oracle#theurgist#neoplatonism#kabbalah#merkava#judaism#magick#meditation#spirituality#prophet#astrology#angels#archangels#PGM

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wrote about Auras!! Give it a read!!

#mtg#magic the gathering#vorthos#auras#neoplatonism#pseudo-Dionysius#symbolic#symbol#Kor spiritdancer#goethe#literary theory

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

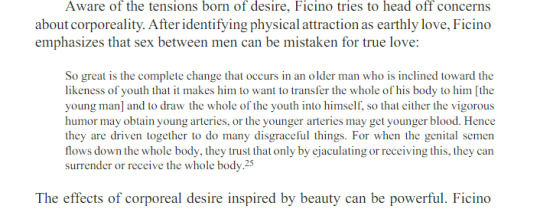

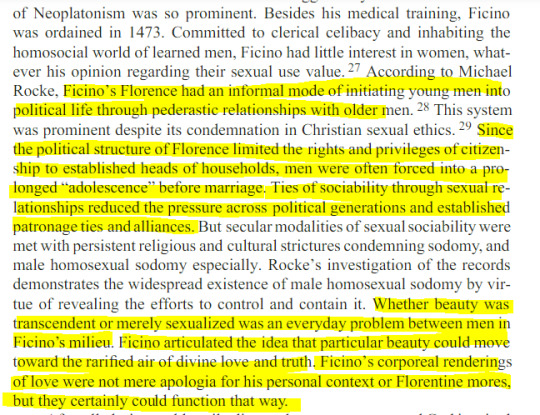

so much on Ficino & Plato & Sex

your daily Marsilio blogging continues, this time with the gentle reminder of the deep misogyny of most homoerotic anything in the medieval and early modern period (among other times as well).

At the same time, I appreciate Marsilio being like: Fuck this, we can do the Petrarchan model of Ideal Love too. Just watch me and Giovanni yearn for twenty years.

I do appreciate that in the whole of Ficino's writing he rarely, if ever, refers to sex between men as sinful. He uses terms of disgraceful, filthy, worthy of disgust, ugliness etc. but he uses those terms equally for heterosexual sex conducted for pleasure alone with no intention of making the babies. Corporality on the whole - in all its forms - is the problem. (And the contemporary medical hang-ups around the expulsion of semen aside.)

But it's still not sinful, it just makes it harder to climb the ladder of love to salvation. Some might think this a small thing (he still reads it as bad!) but there's a huge gulf of difference between a priest from 1478 saying X is disgraceful but never using the language of sin around it.

Granted, Ficino doesn't harp too much on sin in general. I would be very curious to go back in time, get him a little wine drunk, and ask him his actual, not-Church approved views.

Ficino loves trying to reconcile everything through Plato. Marsilio "What if We Applied Plato to This Situation??" Ficino.

The desire/beauty thing - you can just see his struggle in trying to make it all work and never quite succeeding. It's one of the many things he and Pico debated with great animation. Pico was anti-the physical desire part of Ficino's formula while Ficino believed salvation/finding Philosophic Truth (i.e., God) required it.

I do really love Ficino's broadly positive read on humanity. He always goes in with a: People Are Good approach to a situation.

I love this little caveats he gives in his writings. The bit: "Love, even when mixed with an inderior appetite [for sex], does not cease meanwhile to raise the soul as far as it is able."

Giovanni having a panic about the state of their souls as they lie about in the grass and Ficino thinking fast on how to assuage him. "Umm, look, this isn't ideal, and we really should try harder to resist. But ... uh... Love is Good. Right? Our Love is Good and holds no Evil, correct?'

Giovanni, 'Yes, that is correct.'

Ficino, 'Great, so because our Love is Good and our Souls naturally desire Truth and Love is always working to help raise our souls up to Truth - even when we uhhhhh slip up, shall we say--'

Giovanni, 'We purposefully went into a remote field to commit sodomy. This wasn't an accidental slip up, Marsilio. You even checked to make sure you had time enough after this to confess and seek absolution so you can say mass on Sunday.'

Ficino, 'Slipped up. Could have happened to anyone. Anyway, even when that happens Love is still raising our souls up as far as it is able. So what I'm saying is, don't worry about it.'

the knots this man will tie himself in to try and make it ok to accidentally, whoopsie daisy, sleep with men. That full quote from him on how homosexual consorting (sex, that is what he means quite literally) is part of spiritual procreation is really something else.

I also think the caveat he includes of "of course, naturally, when you're horny you should go to your wife to make sure you're doing sex Properly" is doing a lot of interesting work there.

"Giovanni and I loving each other is necessary for OUR PHYSICAL HEALTH OK??"

Technically, he's not wrong. In the sense that being able to openly and honestly love/be loved by who it is you desire - regardless their gender - is incredibly important to mental health which impacts physical health.

mess! mess! mess!

this is super interesting. That Ficino was attempting to figure out how to guide people through reciprocal love in a world where that wasn't normal to navigate.

All of Ficino's back and forth on sex, desire, beauty, love is just so telling of how much he wanted to resolve the issue and how knotted everything was for him (and he wasn't alone, obviously).

--

ok I'm done inundating everyone for now.

#marsilio ficino#marsilio blogging#neoplatonism#early modern history#15th century#giovanni cavalcanti#renaissance italy#renaissance florence#Marsilio sourcing

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

—Henry Corbin, Alone with the Alone: Creative Imagination in the Sūfism of Ibn ‘Arabī

“Perhaps the flower, whose heliotropism proves to be its ‘heliopathy,’ will put us on the path…”

“Proclus ‘listening’ to the flower pray…”

Stunned I’m only reading this after writing THE SUNFLOWER CAST A SPELL TO SAVE US FROM THE VOID and ALIEN DAUGHTERS WALK INTO THE SUN… I’ve fully surrendered to the oneiric heliotropism of the path of mystery! (Maybe I’m ready for my neoplatonist phase?)

#Henry Corbin#mysticism#sufism#islamic mysticism#philosophy#neoplatonism#literature#ibn arabi#ibn ‘arabi#heliotrope#flowers#proclus

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arthur Machen's Idea of Evil

If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to explain one of my favorite ideas in fiction: the idea of positive evil.

The Christian conception of evil is, more often than not, one of negation. Evil is a lack of goodness, a turning away from God. Adam and Eve were born sinless, but acted against God’s will, and so fell from innocence and grace. Thence came Original Sin, an imperfection that was inherited by all humankind. A defect, a blemish—an alteration of what would have been their natural state.

For many people, this is the familiar way of viewing sin and evil, even if they aren’t familiar with all the strange theological offshoots that came from following it to its logical conclusions.

I’m not going to discuss those here, though they’re certainly worth investigating. Rather, I want to talk about how the late Victorian author Arthur Machen, regarded by many as the “grandfather of weird fiction,” created horror and mystery by rejecting this doctrine, and entertaining the possibility of evil with positive substance unto itself.

Picture very much related.

What separates crime from sin, vice from evil, animal fear from existential terror? Much of Machen’s horror fiction follows this line of inquiry in one way or another, but he answers it pretty directly in the prologue of The White People. It’s structured as a short Socratic dialogue between the author stand-in Ambrose and his evening visitor, Mr. Cotgrave:

‘I think you are falling into the very general error of confining the spiritual world to the supremely good; but the supremely wicked, necessarily, have their portion in it. The merely carnal, sensual man can no more be a great sinner than he can be a great saint. Most of us are just indifferent, mixed-up creatures; we muddle through the world without realizing the meaning and the inner sense of things, and, consequently, our wickedness and our goodness are alike second-rate, unimportant.'

'And you think the great sinner, then, will be an ascetic, as well as the great saint?'

'Great people of all kinds forsake the imperfect copies and go to the perfect originals. I have no doubt but that many of the very highest among the saints have never done a "good action" (using the words in their ordinary sense). And, on the other hand, there have been those who have sounded the very depths of sin, who all their lives have never done an "ill deed."'

[...]

'I can't stand it, you know,' he said, 'your paradoxes are too monstrous. A man may be a great sinner and yet never do anything sinful! Come!'

'You're quite wrong,' said Ambrose. 'I never make paradoxes; I wish I could. [...] Oh, yes, there is a sort of connexion between Sin with the capital letter, and actions which are commonly called sinful: with murder, theft, adultery, and so forth. Much the same connexion that there is between the A, B, C and fine literature. But I believe that the misconception—it is all but universal—arises in great measure from our looking at the matter through social spectacles. We think that a man who does evil to us and to his neighbours must be very evil. So he is, from a social standpoint; but can't you realize that Evil in its essence is a lonely thing, a passion of the solitary, individual soul? Really, the average murderer, quâ murderer, is not by any means a sinner in the true sense of the word. He is simply a wild beast that we have to get rid of to save our own necks from his knife. I should class him rather with tigers than with sinners.'

'It seems a little strange.'

'I think not. The murderer murders not from positive qualities, but from negative ones; he lacks something which non-murderers possess. Evil, of course, is wholly positive—only it is on the wrong side. You may believe me that sin in its proper sense is very rare; it is probable that there have been far fewer sinners than saints. Yes, your standpoint is all very well for practical, social purposes; we are naturally inclined to think that a person who is very disagreeable to us must be a very great sinner! It is very disagreeable to have one's pocket picked, and we pronounce the thief to be a very great sinner. In truth, he is merely an undeveloped man. He cannot be a saint, of course; but he may be, and often is, an infinitely better creature than thousands who have never broken a single commandment. He is a great nuisance to us, I admit, and we very properly lock him up if we catch him; but between his troublesome and unsocial action and evil—Oh, the connexion is of the weakest.'

It was getting very late. The man who had brought Cotgrave had probably heard all this before, since he assisted with a bland and judicious smile, but Cotgrave began to think that his 'lunatic' was turning into a sage.

'Do you know,' he said, 'you interest me immensely? You think, then, that we do not understand the real nature of evil?'

'No, I don't think we do. We over-estimate it and we under-estimate it. We take the very numerous infractions of our social "bye-laws"—the very necessary and very proper regulations which keep the human company together—and we get frightened at the prevalence of "sin" and "evil." But this is really nonsense. Take theft, for example. Have you any horror at the thought of Robin Hood, of the Highland caterans of the seventeenth century, of the moss-troopers, of the company promoters of our day?

'Then, on the other hand, we underrate evil. We attach such an enormous importance to the "sin" of meddling with our pockets (and our wives) that we have quite forgotten the awfulness of real sin.'

'And what is sin?' said Cotgrave.

'I think I must reply to your question by another. What would your feelings be, seriously, if your cat or your dog began to talk to you, and to dispute with you in human accents? You would be overwhelmed with horror. I am sure of it. And if the roses in your garden sang a weird song, you would go mad. And suppose the stones in the road began to swell and grow before your eyes, and if the pebble that you noticed at night had shot out stony blossoms in the morning?

'Well, these examples may give you some notion of what sin really is.'

[...]

'You astonish me,' said Cotgrave. 'I had never thought of that. If that is really so, one must turn everything upside down. Then the essence of sin really is——'

'In the taking of heaven by storm, it seems to me,' said Ambrose. 'It appears to me that it is simply an attempt to penetrate into another and higher sphere in a forbidden manner. You can understand why it is so rare. There are few, indeed, who wish to penetrate into other spheres, higher or lower, in ways allowed or forbidden. Men, in the mass, are amply content with life as they find it. Therefore there are few saints, and sinners (in the proper sense) are fewer still, and men of genius, who partake sometimes of each character, are rare also. Yes; on the whole, it is, perhaps, harder to be a great sinner than a great saint.'

'There is something profoundly unnatural about Sin? Is that what you mean?'

'Exactly. Holiness requires as great, or almost as great, an effort; but holiness works on lines that were natural once; it is an effort to recover the ecstasy that was before the Fall. But sin is an effort to gain the ecstasy and the knowledge that pertain alone to angels and in making this effort man becomes a demon. I told you that the mere murderer is not therefore a sinner; that is true, but the sinner is sometimes a murderer. Gilles de Raiz is an instance. So you see that while the good and the evil are unnatural to man as he now is—to man the social, civilized being—evil is unnatural in a much deeper sense than good. The saint endeavours to recover a gift which he has lost; the sinner tries to obtain something which was never his. In brief, he repeats the Fall.'

Emphasis added by me.

Sin, in Machen’s eyes, is a violation of the most fundamental laws of our universe—the principles that determines what is good, what is natural, what is up and what is down. In Platonic terms, it is a violation of the reality that proceeds from ‘God,’ the One, the Good.

To break these laws is not merely to turn away from God, but to turn towards something else. Some entity or principle that is wholly foreign to the Good, and is intruding upon our reality, imprinting itself upon matter and spirit alike.

The sinner turns towards this Evil, just as the saint turns towards the Good, because it induces the same spiritual ecstasy, just in the opposite direction.

You are making contact with a great spiritual Truth, be it supernal or infernal or simply weird, and the very essence of your being is undergoing a process of sublimation in accordance with that principle.

It’s a terrifying idea because it empowers evil in a way that Christian doctrine simply does not allow, and it acknowledges that depravity is, on some level, empowering. It’s not just that we want to get away with breaking the rules. It’s not that we want to follow our appetites without regard for the harm that it may cause. No, sometimes human beings want to commit real violence, spiritual or physical, simply for its own sake—just like we do good things for the sake of goodness.

Attributing that impulse to the influence of a transcendent law or entity, of the same kind as the One, presents an existentially perilous universe. Suddenly we are beset from all sides by forces from outside our reality, as infinite as there are directions, all of which threaten to change the essence of who and what we are. Acknowledging these intrusive powers could mean succumbing to them, and becoming something as foreign to humanity as blossoming cobblestones are to the laws of physics.

Someone beside you, to all appearances human, could be wearing that form only externally, and temporarily. They could in fact belong to something that should not exist in our world at all. And if given the chance, they would discard their human face and show you something that should not be manifested in matter at all.

Chilling, isn’t it?

I was going to talk about this idea in fiction besides Machen’s—I actually see some echoes of it in The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, of all things—but this is already a fairly long post. I’ll save it for another time.

To those who bothered to read this far, what are your favorite examples of ‘positive evil’ in fiction?

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ignudo from the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1508-12

#art history#italian art#xvi century#reinassance#art#art model#michelangelo buonarroti#sistine chapel#vatican#neoplatonism

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

our endeavor is not to be out of sin, but to be a god

Plotinus, in the Enneads, surprisingly almost anticipating what people often take be to the ethos of the Left Hand Path, at least where it is concerned with apotheosis.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demiurgy and How a Confucian Passion for Learning Can be Considered As Such.

What is Demiurgy? As the author of Egyptian Mystic Polytheism so succinctly puts it:

Demiurgy is a type of “devotional act.” A devotional act is any activity outside of direct prayer with a religious purpose and significance. What makes “demiurgy” unique as a type of devotionalism is that it is principally concerned with the act of creation. Like theurgy, to mimic the gods and pursue likeness, one must participate in creativity as a lesser version of God’s creation. Producing, crafting, constructing, and creating are all acts that mimic the “Demiurge” or “Creator Deity.”

So, essentially, these are mundane activities that are performed with the intention to ritualize and devote said craft to the Demiurge, the Creator god of the Cosmos. As the quote above mentions, this is similar to theurgy in that these mundane activities help us mimic the Creator.

With that out of the way, lets take a look at Corpus Hermeticum XI.22, which I think supports such ritualized "demiurgy:

Mind is seen in the act of understanding, God in that act of making.

This sentence refers to God’s literal creation of All Things and how He is seen through His creation, as this whole preceding paragraph refutes the idea that God is entirely invisible and “unseen.” For context, here is the passage:

In Corpus Hermeticum V, we are told God is invisible and entirely visible. For us to understand God, we must become like Him (Corpus Hermeticum XI.20), as so much as that is possible, in each of our Fated predispositions. A way to do so is to create things ourselves through begetting, making music, writing, or exercising, i.e., our own Demiurgy. You can find a list here if the reader wants a more comprehensive list of things that can be considered a devotional act to the Demiurge -- Demiurgy. So essentially, if God is seen in His Creation, we too can see the Demiurge manifests itself via our lesser creations.

Also, possibly a Confucian passion for learning could be considered Demiurgy. Let me explain: To take this principle out of context and apply it to Hermetic thought, I'd like to talk about the Confucian disciple Yan Hui 顏回, who was unmatched in his genuine and effortless love of the Way and learning. In the Analects 6.3 we see a ruler inquiring to Confucius about a "disciple who loves learning":

There was one named Yan Hui who loved learning. He never misdirected his anger and never repeated a mistake twice. Unfortunately, he was fated to live a short life. Since he passed away, I have heard of no one who really loves learning.

Yan Hui is also praised for his love of learning in Analects 2.9 and 5.9. Generally speaking, in Confucian thought, learning, rites, and conforming to cultural adornments 文 do indeed change our native “stuff” 質, which Confucius thought contained inherent flaws that were corrected via rigorously conforming, yet also effortlessly loving social and cultural arts, rites and learning. So, if learning in and of itself can change us for the better; correct our inherent flaws, and make us more like God, then we should all try to emulate Yan Hui and his effortless love for learning because when we learn, we grow. According to Chapter 2 of Effortless Action: Wu-Wei as a Metaphorical Concept and Spiritual Ideal in Early China by Edward Slingerland, learning and instructions (and other things) are essential to constantly strive for and put effort into to abide by the Confucian Way. Learning and instruction change our inherent "stuffs" in a way that makes us effortlessly abide in the Way 道.

So, back to the Hermetica. In Corpus Hermeticum XI.20, we are told to:

“Make yourself grow to immeasurable immensity…”

Arguably, this can be done by a passion for learning (and, of course, many other things)— which cannot be taught but must be realized. And what do we see all throughout the Hermetica? A yearn for Gnosis. Gnosis differs from conventional knowledge, as gnosis is experienced rather than learned. Something that Edward Slingerland argues is the source of Confucius's frustration with the current age of the Zhou Dynasty in Analects 15.13:

I should just give up. I have yet to meet a person who loves ren 仁 as much as he loves the pleasures of the flesh.

Confucius is frustrated by the fact that you genuinely cannot teach a person ren 仁 or "humaneness." Whether we are talking about ren or gnosis (mind you, two completely different things), these things must be experienced and "recollected," as Edward Slingerland argues in Chapter 2. The idea that the gnosis of the gods, God, and the Demiurge is "recalled" is found in passages from Plato's Phaedo 73c-75e and other dialogues I have yet to read, such as the Phaedrus and Meno. Likewise, in Analects 7.30, Confucius exclaims:

Is ren really so far away? No sooner do I desire ren than it is here.

Recollection is also found in the Corpus Hermeticum IV.2:

The man became a spectator of God's work. He looked at it in astonishment and recognized its Maker.

Now that we have established that the Analects, Platonism, and Hermeticism are structured somewhat similarly, let's look at Corpus Hermeticum I.31, we read:

“Holy is God, who wishes to be known and is known by his own people…”

Corpus Hermeticum I.32:

“Grant my request not to fail in the knowledge (gnosis) that befits our essence.

This suggests that God wishes us to know Him as much as possible according to our inherent predispositions to gnosis. So what I’m getting at is that if we can realize and acquire a Confucian-style passion, such as Yan Hui, for learning, this can change us and make us become more like God. The love for learning. The yearning to know God and His creation and the sciences that we have developed to understand his creation is most certainly Demiurgy. We never stop learning, whether we continue education after high school or not.

So, now that we have established that learning can indeed change us and help us mimic and help us recognize God and the Demiurge's creation, here are some examples of how I use my love for learning (but this love cannot be compared to Yan Hui's) as Demiurgy:

Reading academic literature on my beliefs

Learning the mythologies of the Ancient Egyptian gods

Going to college to broaden my knowledge and to establish a career.

Learning about myself: both my corporeality (psychology/body/health) and my incorporeality (soul).

This list goes on and is certainly not limited to those few bullet points. But if it is not clear by now, learning helps us grow as individuals; learning allows us to better understand the world around us, from our own communities to other cultures around the world. Such a whole-hearted pursuit of learning can be considered Demiurgy because we are actively creating a better version of ourselves. Just as in my musings, I consider Demiurgy because I am creating writings that will go on to inform and help other people understand the topics I write about with an intention of devotion to the Demiurge. My active pursuit of learning also is Demiurgy because everything I learn is done in devotion to the Creator of a world I love so much, and He is ultimately responsible for the very things I choose to learn.

So, do you all think the yearn and love for learning in and of itself can be considered Demiurgy?

#hermeticism#confucianism#confucius#plato#platonism#neoplatonism#demiurge#demiurgy#philosophy#chinese philosophy#hermetic philosophy#learning#yan hui

7 notes

·

View notes