o-uncle-newt's detective fiction sideblog. Mostly Holmes, will likely include other authors, Sayers will probably stay on my main just from force of habit (except for her Holmesian scholarship of course)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I have to say, people who read the Sherlock Holmes canon and ship the two of them should be forced at gunpoint to read the Raffles stories

Like, genuinely. There is nothing remotely subtle about this- completely and proudly blatant, I don't even know.

I largely enjoy the stories themselves, though I don't think Hornung was at his best when writing the action sequences that the scenarios generally required- but their relationship just freaking sparkles in such a fun way and it's not even as though it's subtext, or if it is it's very near-the-surface subtext, it's just that every single goshdarned opportunity Hornung has to show how obsessed Bunny is with Raffles or how devoted Raffles is to Bunny or how annoyed either one is when the other shows any interest at all in a third party, he takes. And it's not just obsession or devotion or jealousy, they just clearly love each other and are proud of each other and want to be with each other. I'd say it's romance novelesque but so many romance novels don't even really bother with that bit.

I mean (spoiler warning) the whole saga literally ends with Bunny's ex-girlfriend writing him a letter saying "I get that you burgled my house because you followed Raffles because you were in love with him, he came by and told me so and I totally get it, he's super great, but now that he's dead and you're not with him anymore maybe we can get back together someday." Who DOES this.

I know I'm not saying anything here that freaking WIKIPEDIA doesn't already say, but I'd only read some of the stories in no particular order before and didn't realize what the full cumulative impact of it would be til I binge-read all three short story collections together. Unreal. Still not over it. I'm a canon fan/shipper as a general rule for stuff and this is just canon.

#raffles#aj raffles#bunny manders#ew hornung#sherlock holmes#i don't even ship holmes/watson#except POSSIBLY in the granada version#but like... the only objection to the raffles stories i can think of for holmes/watson shippers#is that it's so blatant and obvious that it doesn't leave as much room for creative interpretation#but honestly in return it provides so much opportunity for shenanigans#i have to assume that much has been written on this subject (queer themes/aestheticism/other things like that)#and now i kind of want to find all of it#apparently the tag for raffles/bunny- or rather the raffles stories- is#crime and cricket#but seriously i assume someone has already written about how#even when one of them has a(n ex-) girlfriend mentioned#it's ALWAYS in a way that comes across as reinforcing how gay they are#/how important they are to each other and how different their relationship is from either's with anyone else#man or woman really#the last time i mentioned raffles in a post i was like “eh not such a fan”#“don't love antihero stories”#and like that's TRUE but#maybe not as specifically true in this case? though the fact that they fail sometimes makes it more fun for me#i do think overall i like holmes stories better#but like...

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clearly I need to watch full Granada Holmes episodes more rather than just clips... completely missed out on the context of this moment

So, this clip is great, and I see it come up all the time on the compilations that I watch when I'm in a Granada Holmes mood but don't have time for a full episode:

youtube

It's great, really sweet, and has the benefit of coming basically straight out of a bit of the source story, The Norwood Builder. The scene expands on it (Holmes is more openly depressed, Watson specifically encourages him to eat) a bit but the core ideas are all there.

So all that's great, but I was just watching The Norwood Builder (and incidentally, SPOILERS for this episode below!) and maybe it's the fact that I was also literally chopping a shitton of onions at the time but I completely had not contextualized this with the scene immediately before (about 32 min in):

youtube

The thing with the original Norwood Builder story is that it's one of ACD's stories that doesn't really have an actionable crime to prosecute at the end, unless either "wasting police resources" was criminalized back then or they had a REALLY strict definition of "attempted murder." This episode decides that, instead of having there be no real crime, there will instead be one of the darkest crimes in the series, and it's actually an improvement on a somewhat unconvincing detail in the story in addition to really changing the tone.

So this episode decides to include a particularly cruel and craven murder of an extremely vulnerable person, but doesn't only do that- it conveys that information to us in an extremely emotionally evocative and moving way. Again, I was literally chopping onions which probably didn't help, but it was devastating to see the scene in which we see Holmes disguised as a vagabond, talking to a man who clearly feels betrayed by this sailor who promised to share in (what he thought was) his good fortune but, as far as the man can tell, skipped off without keeping his promise, and we watch Holmes's face as his horrible theory is confirmed about what REALLY happened to the sailor while the other man has no clue.

The immediate next scene is Holmes frozen, his hair and room a mess, and the juxtaposition is stark. His hair isn't messy because he hasn't gotten around to fixing it in the morning, it's the same as it was the night before when he mussed it up for his disguise but the realization of the brutal crime- and what will clearly be tremendous difficulty in both proving it and preventing another innocent's death- has paralyzed him. He knows exactly what happened, he knows exactly how horrific this all is, and he believes that circumstances (including Lestrade's new clue) have lined up to not only allow Oldacre to get away with his crime but to allow Holmes's client to hang for it. Everything is fucked and Holmes can, he believes, do NOTHING to prove it. He can turn over his theories to McFarlane's attorney to use for reasonable doubt but he can't solve it.

He asks Watson for his support that day because, as Watson smugly tells Lestrade at the end after they emerge victorious, his work is its own reward, but there's not much reward when the work cannot produce what it needs to. Success may provide enough intrinsic motivation that Holmes doesn't need publicity, but conversely failure to accomplish his goal- not just to discover what happened but to prove it and thus solve a crime/save a life- is enervating. Watson has understood this throughout the case, taking his own initiative to help support Holmes's hunch that McFarlane is being set up, and Holmes knows he can count on him for this.

Anyway... super dark episode with that edit, but an excellent one.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#holmes#the adventure of the norwood builder#granada holmes#jeremy brett#incidentally- another episode that makes a plot change that makes the whole thing darker (that deserves its own post) is lady frances carfa#much larger plot changes but i don't even really mean those#i mean the fact that they spell out the ending#there's actually some real body horror there imagining her stuck immobile in the care of a man who's been wanting her for so many years#but who also isn't getting her in the way that he'd have wanted her#just gives chills#Youtube

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not exactly!

Phrenology is specifically the skull bump thing. There were SOME influences of that that popped up in early anthropology, but it's not quite the same thing. Dr Mortimer's skull obsession was definitely anthropological, and while he does very indirectly imply correlation between Holmes's skull shape and his mental abilities, it is not in the same way that phrenology did it, even if, in retrospect, we find it also unconvincing. (Though most of the terms that Dr Mortimer uses are still technically used in anthropology today, IIRC- but with different use cases.) His discussion of skull types re different races is a branch of 19/e20c anthropology whose principles were used (though not in text by Dr Mortimer as far as I can tell!) to develop "scientific racism," which had many forms but of course culminated in Nazi race theory.

Moriarty in The Final Problem says something similar to what Holmes said in The Blue Carbuncle, assuming that head size/skull shape is connected with brain development/intelligence. That, too, is more about assumptions made re physiognomy spurred by early anthropology, not phrenology per se. If Moriarty had looked at Holmes and said "your organ of philoprogenitiveness is underdeveloped," then THAT would be phrenology.

Why is it a truism right now on Bsky that Sherlock Holmes was into phrenology, when it literally never comes up in canon to my recollection

Sure, he has an overreliance on old fashioned ideas about physiognomy (but not even as often as people think), and his forensics can be pre-scientific (though I think a lot of people would be dismayed at what modern-day forensics is like), but not phrenology. That was a highly specific insane thing that was largely out of vogue before Holmes was ever (fictionally) born and which, while it slightly poked its head into early anthropology, was not really one of Holmes's vices. (MAYBE Dr Mortimer's, though?)

Incidentally: you want a book with weird phrenology? Jane Eyre.

"Criticise me: does my forehead not please you?” He lifted up the sable waves of hair which lay horizontally over his brow, and showed a solid enough mass of intellectual organs, but an abrupt deficiency where the suave sign of benevolence should have risen. “Now, ma’am, am I a fool?” “Far from it, sir. You would, perhaps, think me rude if I inquired in return whether you are a philanthropist?” “There again! Another stick of the penknife, when she pretended to pat my head: and that is because I said I did not like the society of children and old women (low be it spoken!). No, young lady, I am not a general philanthropist; but I bear a conscience;” and he pointed to the prominences which are said to indicate that faculty, and which, fortunately for him, were sufficiently conspicuous; giving, indeed, a marked breadth to the upper part of his head: “and, besides, I once had a kind of rude tenderness of heart."

Now THAT's phrenology.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#holmes#sherlockiana#phrenology#the hound of the baskervilles#the final problem#the blue carbuncle#NOTE- i am not an anthropologist and while i've studied the topic it's been from a historical lens#anyone with actual anthropological background can feel free to correct me

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it a truism right now on Bsky that Sherlock Holmes was into phrenology, when it literally never comes up in canon to my recollection

Sure, he has an overreliance on old fashioned ideas about physiognomy (but not even as often as people think), and his forensics can be pre-scientific (though I think a lot of people would be dismayed at what modern-day forensics is like), but not phrenology. That was a highly specific insane thing that was largely out of vogue before Holmes was ever (fictionally) born and which, while it slightly poked its head into early anthropology, was not really one of Holmes's vices. (MAYBE Dr Mortimer's, though?)

Incidentally: you want a book with weird phrenology? Jane Eyre.

"Criticise me: does my forehead not please you?” He lifted up the sable waves of hair which lay horizontally over his brow, and showed a solid enough mass of intellectual organs, but an abrupt deficiency where the suave sign of benevolence should have risen. “Now, ma’am, am I a fool?” “Far from it, sir. You would, perhaps, think me rude if I inquired in return whether you are a philanthropist?” “There again! Another stick of the penknife, when she pretended to pat my head: and that is because I said I did not like the society of children and old women (low be it spoken!). No, young lady, I am not a general philanthropist; but I bear a conscience;” and he pointed to the prominences which are said to indicate that faculty, and which, fortunately for him, were sufficiently conspicuous; giving, indeed, a marked breadth to the upper part of his head: “and, besides, I once had a kind of rude tenderness of heart."

Now THAT's phrenology.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#holmes#sherlockiana#phrenology#jane eyre#charlotte bronte

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was watching Soviet Holmes E1, where Watson starts off thinking that Holmes is actually a master criminal and thief, and was like "oh, that would be cool, a Holmes adaptation where actually it's Holmes who's a gentleman master criminal and Watson goes along as the accomplice and documents his adventures."

And then of course I realized I was reinventing freaking RAFFLES.

Which was literally written by ACD's brother in law, 125 years ago, basically to be that exact thing. A series of stories that literally includes Hornung's own version of the Reichenbach Fall and subsequent return.

Maybe I need to watch a Raffles adaptation. Or just reread Raffles.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#holmes#watson#john watson#soviet holmes#russian holmes#raffles#ew hornung#arthur conan doyle#i do prefer holmes to raffles all things being equal#just bc i'm not the biggest lover of antihero stories#i'm a simple soul- i like to root for the good guy#but they are extremely fun

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let my mind wander after my previous post and the above resulted! Question though, for the Sherlockian-minded on here- there is no chance that someone hasn't already asserted this and written it up, and while I don't think I've ever read anything of the kind I have no doubt that, in a field in which (to quote Christopher Morley) "never has so much been written by so many for so few," someone has previously written about this.

If anyone is familiar with the BSJ (or other local societies' journals) backlogs and has any idea if when this has previously been posited, I'd be fascinated to know!

I just did a post on my Holmes blog about Rex Stout that mentioned what was clearly his magnum opus, "Watson was a Woman," which claims that Watson was a woman, Irene Adler in particular, who was married to Holmes- and that the two of them produced Lord Peter Wimsey.

Stout's allegation about Wimsey being born of Sherlock Holmes and Irene Adler/Norton/Watson (!?!?) is obviously garbage, as contrary to the scrupulously researched and deathly serious rest of the article /s, this statement is based on Stout vaguely assigning Wimsey a birthdate around the turn of the century, when The Second Stain was published- presumably because that connotes a clear point when Holmes and Watson were no longer actively solving cases, and presumably their removal to the Sussex Downs to raise bees was also intended to provide a place for them to raise their son away from the hustle and bustle of the city. Or something.

The problem here, of course, is that Wimsey was, per his author, born in 1890, when both Holmes and Watson were in the public eye solving cases. And, like, we know who Wimsey's parents are. So that's a wash.

...or is it?

There is another possibility. Wimsey's birthdate of 1890 is mentioned a number of times, one of which is in DLS's radio story written for the Holmes birthday centennial. In this story, she helpfully situates that Wimsey's birth came just before Holmes's apparent death, and that Wimsey's father was a "minor member of Cabinet" during the period of The Naval Treaty, and thus was involved in the affair at the time. It is implied that he may have met Holmes at this juncture.

The Naval Treaty is dated, in-story, as the July after Watson's marriage. Watson becomes engaged to Mary Morstan in 1888, and has married her by June 1889, per Twisted Lip. Ergo, Naval Treaty takes place in July 1889.

Apropos of nothing... let's consider Sherlock Holmes's hands. We're told over the course of the stories that he has "long, white, nervous fingers" and a "delicacy of touch," which he obscures by the fact that he always has punctures and chemical stains all over them. We'll of course get back to this.

So it's July 1889. Mortimer Wimsey, Duke of Denver (or Viscount St George, unclear), is a minor cabinet minister, a position he has most certainly fallen upward into. He is in a marriage of more or less friendly detente with his wife Honoria, much cleverer than he is, on whom he is constantly cheating. She's already given birth to the heir, a clear chip off the old block. One day, Mortimer comes home and tells Honoria of the calamity of the disappearance of the treaty. A month or so later, he excitedly comes home to share that the great Sherlock Holmes has found the treaty, solved the case, and saved the empire. Honoria is, of course, pleased to hear this, and even more impressed by this Mr Holmes than she already had been from other tales of his exploits which had made their way to high places.

We know that Holmes did not shy away from connections with nobility and royalty, and that for all his protestations that he did not discriminate by class in his detective practice (clearly true), in his private life he did not object to being feted by the upper classes. It was probably not that difficult for Honoria to invite him for dinner, or get herself invited to a party celebrating Holmes's accomplishment. Or perhaps it was Mortimer, respecting intelligence greater than his own, who invited Holmes. It could have happened pretty much anytime over the next few months- and, somehow, and without my attempting to explain exactly HOW, because the mind recoils, Honoria's second child resulted without her husband's involvement.

We know that Mortimer had no idea, as he seemed uncomplicatedly joyful when, as DLS noted, he came home to Honoria to tell her the news of Holmes's return. We wonder if Holmes knew- Wimsey's narration makes clear that he's not sure why Holmes let him into the 221b rooms, but what else would he do for his secret son? And, of course, the Wimsey hands, the only positive trace of Wimseyness that wasn't quite overcome by Delagarditude, were in fact Holmes hands, delicate and sensitive. (But Gherkins had the same ha- shut up.)

And no, in case you're wondering, I have absolutely no shame. After all, as DLS herself said, the Game "must be played as solemnly as a county cricket match at Lord's; the slightest touch of extravagance or burlesque ruins the atmosphere." And two can play that Game.

#sherlock holmes#arthur conan doyle#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#lord peter wimsey#dorothy l sayers#sherlockiana#the game#the great game

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mid-Nero Wolfe kick, read the Arnold Zeck trilogy, and it is actually wild how In The Best Families is basically just The Final Problem/The Empty House, His Last Bow, and Charles Augustus Milverton shoved in a blender.

What else would one expect, after all, from an irreverent* yet devoted Sherlockian and Baker Street Irregular like Rex Stout?

*I defy anyone to apply another term to the writer and deliverer of the 1941 BSI dinner keynote, Watson was a Woman, in which Stout claimed that Watson was a woman, that she was married to Holmes, that this female Watson was also Irene Adler, and that they, improbably, were the parents of, for some reason, Lord Peter Wimsey of all people.

That said... and spoilers for the book itself below the cut...

The funny thing is, though, that while it's hard to read In The Best Families any other way once you make that Holmesian connection, I actually didn't much like the way the book handled all this. Arnold Zeck was fun in the prior two books, when he was just an unseen influence and we didn't know quite who he was or what he was doing, let alone how; in the same way, we only got a very general idea from ACD about how Moriarty achieved his status as Napoleon of Crime, and certainly never got a real sketch of his organization or how it functioned, which allowed him not just to maintain an air of mysterious menace but also a camouflage of very vague plausibility. But in the third book, Stout makes the mistake of not just going into detail on how the organization functions, not just introducing us to Zeck in the flesh, but also having Wolfe do a very very implausible and unconvincing undercover job (even Holmes's undercover job in His Last Bow took him years to accomplish to establish his identity!) and penetrate the organization in a way that makes no sense. Then, even on its own terms, the whole structure that Stout made the mistake of sketching out gets punctured by Zeck openly telling Archie the score in a way that would make him quite dangerous in a courtroom, unless I'm missing something.

The smidge of Milverton I did enjoy- that said, I think what I most liked was the idea of the book as "what if we'd seen Watson go about his real life over the hiatus." Obviously, Holmes being dead vs Wolfe just being missing make the dynamics of the various hiatuses different, but at the same time, ACD does have Watson allude to his continuing his interest in crime without Holmes around, and adaptations take it even further (with Granada showing Watson as a police doctor in the Ronald Adair case). Archie, of course, is not quite Watson in his role or personality and it's therefore fun to see how he takes to independence, but being able to follow the hiatus throughout it (with of course Marko Vukcic as Wolfe's Mycroft and, arguably, Fritz as his Mrs Hudson). It was really entertaining, and whether intentional or not (and I can't imagine it wasn't) it was a fascinating homage to Holmes- but I do feel like it got away from Stout a bit, and I don't get the impression that he ever took a departure like this again.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#holmes#sherlock holmes canon#sherlockiana#baker street irregulars#bsi#rex stout#nero wolfe#archie goodwin#arnold zeck#in the best families#the final problem#the empty house#his last bow#the adventure of charles augustus milverton#watson was a woman#lord peter wimsey#irene adler#worth noting that- while of course the wimsey parentage allegation went nowhere- some sherlockians went on to maintain that...#sherlock holmes and irene adler norton were the parents of- drumroll please- nero wolfe#others claim that wolfe's father was instead mycroft holmes given certain common predilections presumably genetically inherited

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Was just reading Richard Lancelyn Green's The Uncollected Sherlock Holmes and he makes a really good point in the introduction that I hadn't thought about in quite this way- that the Golden Age of detective fiction, in all its variety, was kick-started in the early 20c by a bunch of writers (EC Bentley, Baroness Orczy, Agatha Christie, etc) reacting to Sherlock Holmes by creating detectives who were as different from him as it was possible to be.

I find it a really interesting thought (and I'm sure there are other writers who can be said to have done the same, though Green doesn't mention them)- the idea that a very varied and creative genre could spring from writers all being so influenced by one particular character that they wrote something as distinctive as possible from it. If Holmes's existence spurred creativity enough to give us the Old Man in the Corner and Poirot (I'll admit, I never really got into Trent's Last Case), not to mention the other varied detectives who would arrive over the coming decades, then that's a great legacy in its own right. To be fair, the cultural penetration of Holmes and ACD was so massive that it's almost impossible for subsequent writers not to have been influenced by the canon, but the idea of the reaction to him triggering this 1910s-30s flourishing of creativity does tickle me.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#holmes#sherlock holmes canon#sherlockiana#hercule poirot#agatha christie#baroness orczy#the old man in the corner#lady molly of scotland yard too i guess#though green didn't mention her#ec bentley#trent's last case#arthur conan doyle#i will say#as someone who for a long time knew nothing about green except for the stuff about his tragic and dramatic death#while this isn't the first of his writings i've read it's still nice to engage more with the work he was so passionate about in life#richard lancelyn green

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the topic of Sherlockiana... a highlight of my visit to London!

It was a pretty jam packed trip that, yes, included plenty of the standard touristy things, but I also took a second to take a photo here.

So where am I?

See if you can guess- I'll give you a minute.

*

*

*

*

*

I'm actually only a few doors down from the Sherlock Holmes Museum (which I will admit I did not visit- time was tight and tickets were not cheap- but I did get a photo there too). I am, instead/in addition, at Abbey House, the former home of the Abbey National Bank- an institution with a storied Sherlock Holmes history.

Now, when I thought I'd have more time for the Sherlockian part of my sojourn (I also needed, among other more typical touristy activities, to get to Poirot's and Lord Peter Wimsey's respective apartment buildings at various points, not to mention my Gaudy Night Oxford walking tour), I had serious plans to walk the area and stop at every address that has been pointed out, by different Sherlockian scholars, to possibly have been the location of 221B Baker Street.

But why are there multiple places where 221B might be? I didn't have the same question, after all, when I went to the vague general location of 112A Piccadilly to visit Lord Peter Wimsey (now a Sheraton hotel, but ah well). For a different reason, nor did I when I visited Poirot's residence, because Whitehaven Mansions doesn't exist and so I went to the TV show exterior location (Florin Court, near the Barbican). But with 221B Baker Street it is a very real problem (and not least because the Granada exterior was a set in Manchester and I can live without a photo in front of the BBC Sherlock one).

It's also a problem that's been written about extensively in a variety of books and articles. I won't go through all of them here, partly because I don't have all the material in front of me and partly because it would take QUITE a while, but the gist is that 221B Baker Street did not exist when the stories were written. The highest house number on the street was 84, and the part that now has the 200s was called Upper Baker Street. In between Baker Street and Upper Baker Street was York Place, and if you ask Sherlockian scholars, 221B could have been at several different houses on any three of these streets, meaning all the way up and down the modern-day Baker Street. In fact, for those interested in interrogating where 221B must have been based on landmarks, the location of the current 221B (the Sherlock Holmes museum) is actually blocks away from where Holmes himself must have lived- partly because ACD could never have known that the three streets would merge, and partly because of the kinds of landmarks that ACD gives in stories like The Empty House.

And so, in essence, the fact that a 221B (more or less) Baker Street exists today is basically a coincidence.

A separate post would go more into the various different addresses that have been posited by a variety of commentators based on London geography and Sherlockian canon over the last hundred or so years- such as 49 Baker Street by TS Blakeney, 61 Baker Street by Gavin Brend, 111 Baker Street (formerly on York Place) by Dr Gray Chandler Briggs (with the approval of Vincent Starrett), and 31 Baker Street by Bernard Davies (with the approval of William S Baring-Gould). I am still a bit mad I didn't get to visit and pace out their accuracy for myself, though I know London has changed a lot since many of them made their determinations. But all this to say that 221B is still clouded in fog, but that for all practical purposes Abbey House, for several decades, was a lighthouse within it.

After all, once 221B DID exist, who would be getting Holmes's mail? The answer- the Abbey National Bank, which built as its headquarters Abbey House at 219-229 Baker Street, where it resided from 1932-2002 (the building is now residential as I understand it- Abbey National Bank is now part of Santander and HQ is elsewhere). As of 1932, this block had only been part of Baker Street for two years, and while 221 was technically not its own address, it was clearly within the area designated for Abbey House. Some businesses, placed in one of the most famous addresses in the world, would see this as a burden- Abbey National Bank, for over fifty years, took the exact opposite approach, including:

In 1951, they hosted an exhibit in cooperation with the Conan Doyle family celebrating the world of Sherlock Holmes, which can now be seen (but sadly not by me due to an unfortunate wrong-tube-related incident) at the Sherlock Holmes pub in Charing Cross

They put up a plaque, unfortunately now lost, at their building to commemorate Holmes's, well, home

They employed a secretary to answer mail sent to Holmes at 221B Baker Street (and there was plenty of it)

They published or were part of publishing multiple Holmes-related books, including one edited by Richard Lancelyn Green featuring letters written to 221B

They helped fund a statue of Holmes that still stands today at Baker Street

They also objected when, in 1990, the Westminster City Council put up a blue plaque (a London staple commemorating the heritage of local buildings) at the new Sherlock Holmes Museum, farther down the street, calling it 221B. This made the street numbering out of whack and angered Abbey National, which by all accounts had the actual location where 221B WOULD be re street numbering and had spent years investing in its Sherlock Holmes connection. The museum spent nearly a decade trying to get the rights to the 221B street number so that it would receive all of Holmes's mail, only winning the rights to the out-of-sync street number when Abbey vacated the premises in 2002, ending its seventy year long relationship with Sherlock Holmes.

Abbey National is a legend, and I was thrilled to visit its former site. Definitely worth a quick stop by anyone already heading 221B-ward!

#acd holmes#holmes#sherlock holmes#sherlock holmes canon#sherlockiana#221b baker street#dorothy l sayers#lord peter wimsey#agatha christie#hercule poirot#arthur conan doyle

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I feel like The Six Napoleons is one of the best Granada episodes, and part of why is, of course, That Scene.

By which of course I mean this one:

youtube

All genius, but of course, even more specifically, the bit starting at about 5:52. You know the scene I mean, and if you don't by all means watch it!

Honestly, it's an in-a-nutshell demonstration of the greatness of both canon and the Granada adaptation.

Here's the scene from the book:

“Well,” said Lestrade, “I’ve seen you handle a good many cases, Mr. Holmes, but I don’t know that I ever knew a more workmanlike one than that. We’re not jealous of you at Scotland Yard. No, sir, we are very proud of you, and if you come down to-morrow there’s not a man, from the oldest inspector to the youngest constable, who wouldn’t be glad to shake you by the hand.” “Thank you!” said Holmes. “Thank you!” and as he turned away it seemed to me that he was more nearly moved by the softer human emotions than I had ever seen him. A moment later he was the cold and practical thinker once more. “Put the pearl in the safe, Watson,” said he, “and get out the papers of the Conk-Singleton forgery case. Goodbye, Lestrade. If any little problem comes your way I shall be happy, if I can, to give you a hint or two as to its solution.”

And here's the dialogue from the show:

Lestrade: I’ve seen you handle a good many cases in my time, but I don’t know that I ever knew a more workmanlike one than this. We’re not jealous of you, you know, at Scotland Yard. No, sir, we are proud of you, and if you come down to-morrow there’s not a man, from the oldest inspector to the youngest constable, who wouldn’t be glad to shake you by the hand. Holmes: Thank you! Thank you! Would you get down the Conk-Singleton forgery case please, Watson? Goodbye, Lestrade. If any little problem comes your way I shall be happy, if I can, to give you a hint or two as to its solution.

Not many differences! ACD knew what he was doing- he knew how to write a good yarn, he knew how to write good characters, and he knew how to write a good interaction. Granada wasn't filmed in canon order, so we don't get to see the progression of Holmes's relationship with Lestrade per se, but after a number of excellent, more "foiled again!" type Holmes-Lestrade interactions since A Study in Scarlet, ACD decided to do something cool and different here and pulled it off beautifully.

And when the director and writer of this Granada episode put this one together, they decided that the relationship between Holmes and Lestrade should be a focal point in this episode, and not only did they barely need to change a dang thing in the ending to do it, what small things they did change were all beautifully in the service of the tone of the original ending, taking advantage of the brilliant material they had to work with. I was just relistening to the excellent episode of the Jeremy Brett Sherlock Holmes Podcast discussing The Six Napoleons, and one of them points out that one of the few text changes is removing the word "very"- going from "we are very proud of you" to "we are proud of you." And it works so well- it accentuates the contrast with the previous suggested notion that they would otherwise be jealous, between what Holmes might have expected to hear (and, indeed, perhaps expected to WANT to hear) and the actuality, and how much more meaningful it turns out that is to Holmes.

The creators here- and I of course include the actors, as both Colin Jeavons and Jeremy Brett act the fuck out of this- are so smart with how they pull this off. They know that what they have on the page is gold, but they also know how they can buff it up for a stronger shine. They know that Brett will absolutely eat up all of ACD's stage directions about his response, he knows the character inside and out at this stage, so let's keep the scene the way it is and, instead, build the rest of the episode around setting up this scene in such a way that it will have maximum impact as written.

There is one thing that is added- and that's the handshake at the end, that Holmes offers to Lestrade. We don't know what happens after Holmes's final words in the story, but in the episode, the physical acting continues telling the story only implied in the text of the short story- Lestrade is a bit thrown by Holmes's reversion back to his old, casually cutting self, but rolls with it, only for Holmes to extend his hand to him. Lestrade seems, even, slightly surprised- this is, perhaps, Holmes's rare gesture of pride in him.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#holmes#sherlock holmes canon#canon holmes#the six napoleons#granada holmes#sherlock holmes granada#jeremy brett#colin jeavons#lestrade#Youtube

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

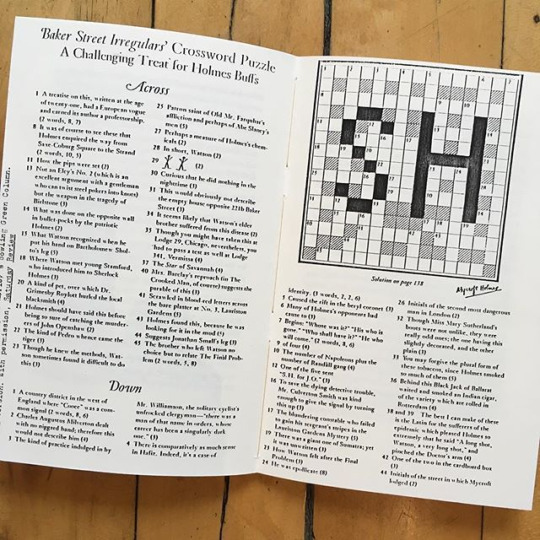

Can you solve this Sherlockian crossword puzzle?

Image source

If you can, and a) you're a man and b) you can go back in time more than 90 years to May 1934, then you're eligible to be among the founding members of the Baker Street Irregulars, a brand-new Sherlock Holmes fan club!

How it worked- be a reader of the Saturday Literary Review, a magazine cofounded by Christopher Morley; notice that in the May issue, a crossword had been printed (created by Morley's brother Frank) testing Sherlock Holmes knowledge; attempt to solve it, and submit results to the SRL; and, not long after, be invited by Morley to the first ever Baker Street Irregulars Dinner.

But, again, only if you're a man (yes, some women did submit correct answers and were passed over). Morley was a perennial club-founder, some of which were for both men and women, others of which were solely "stag" (as he put it)- he decided that the first BSI dinner would be stag and they stayed that way for sixty years, even though that first dinner was one of only two which Morley himself ran, before the event was taken over by Edgar Smith.

Apparently, per the website of the I Hear of Sherlock Everywhere podcast, there used to be an online version of the puzzle which was much easier to solve than the blurry photo above, for those not fortunate enough to have their own copy! That said, hopefully the above isn't too hard on people's eyes.

#sherlock holmes#acd holmes#holmes#sherlock holmes canon#sherlockiana#bsi#baker street irregulars#crossword#christopher morley

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I enjoy this but also- "conventionally attractive" is a kind of meaningless term. I agree that it's weird to imagine Holmes looking like Henry Cavill, but there's a difference between that and weird-looking. Though- have people SEEN Jeremy Brett in My Fair Lady (or Rebecca, where he is marred only by that stupid mustache)? That dude was definitionally "conventionally attractive." The kind of attractive that he was just happens to go well with descriptions of Holmes in canon, and a lot of it came down to makeup and costuming.

As in, Holmes has some distinctive facial features mentioned in canon, but there's nothing that says that he isn't also attractive in whatever that very distinctive way is. (I'd also add that I've seen some tags mentioning Holmes needing to be super-thin, which is admittedly canonical, and this was a notion that really hurt Jeremy Brett when he was in the later years playing the character- he had a lot of water retention due to health problems/medications and literally apologized to fans for not being the thin Holmes that they expected, which is kind of heartbreaking.)

Lord Peter Wimsey is described early (as is noted) and often as odd-looking, but not unattractive per se- lots of people critical of the Wimsey-Vane relationship will talk about Sayers de-uglifying him by Gaudy Night, such as by making him taller and more attractive to women, but that doesn't really follow from the books because a) Wimsey is established as a respectable-if-not-tall-per-se 5'9" as of Clouds of Witness and b) in Gaudy Night Wimsey is seen through the eyes of Harriet... who loves him, even if she won't admit it. Sayers is very willing to write in the Vane Quadrilogy exactly what it is that Harriet finds attractive physically about Peter- in a way that, incidentally, she doesn't really have Peter do about Harriet. Of course, the person who plays Wimsey should be able to be interesting-looking as he's described in canon, but if they erred on the side of better-looking I don't think it would be the worst thing in the world, especially with hair and makeup. It's not about how good-looking the actor naturally is, but how their look is designed for the screen.

Now Poirot... yeah, he needs to look dorky, there's no two ways about it. He needs to look like someone whom only Vera Rossakoff could, well, I won't say love- let's say find endearing.

if there's one thing about classic literary detectives it's that they are not conventionally attractive. doyle told sidney paget to stop drawing holmes so pretty. christie was like "let me introduce you to this short pudgy balding man who is retirement age and i hate him." sayers compares wimsey to maggots on literally the FIRST PAGE

i love it. i love them. stop casting hot people in these roles. we need our detectives to be Charmingly Weird-Looking

#sherlock holmes#jeremy brett#hercule poirot#lord peter wimsey#in general the role of hair and makeup in this is really underestimated#edward petherbridge is distinctive looking but he doesn't inherently look like wimsey- most of that was done by his hair and makeup#it's more about actors of the right general physical type than their “conventional attractiveness” level#i can't get used to ian carmichael in the role not bc he's too “conventionally attractive” but bc he doesn't look like the book description

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Working on a longer Sherlockian text post (or three), but in the meantime, for no reason at all, something that never fails to make me smile when I need it:

youtube

My sincere and everlasting thanks to Rena Sherwood, whoever you are!

#sherlock holmes#jeremy brett#granada holmes#granada sherlock#sherlock holmes granada#only one of several granada holmes compilation videos that i have in my youtube recommendations panel at pretty much any time#jeremy brett was a genius#Youtube

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Different Kind of Queen of Crime- five ways that Dorothy L Sayers changed the way we see Sherlock Holmes

For my first Holmesian post- a crossover with one of my more usual subjects on my other blog! For when one is talking about Sherlock Holmes, in particular Sherlock Holmes scholarship, there are nor many more pivotal names than Dorothy L Sayers. Sure, Christopher Morley may have had a greater impact on Sherlockian culture, and Richard Lancelyn Green on Holmesian scholarship, to name only a few- but Sayers's contributions to scholarship and "the game" were early and underratedly pivotal.

If you're a Sherlock Holmes fan who is unfamiliar with Sayers's influence, or a Sayers fan who had no idea she had any interest in Holmes, keep reading! (And if you're a Sherlock Holmes fan who wants to know what I think about Sayers, check out her tag on my main blog, @o-uncle-newt. Or, more to the point, just read her fantastic books.)

There's a great compilation of Sayers's writing and lecturing on the topic of Holmes called Sayers on Holmes (published by the Mythopoeic Press in 2001), though some of her essays are also available in her collection Unpopular Opinions, which is where I first encountered them. It's not THAT extensive, and it's from an era in which Sherlock Holmes scholarship, such as it was, was still very much nascent. While a lot may have happened since Sayers was writing and talking about Holmes, she got there early and she made an immediate impact- and here's how:

She helped create and define Sherlockian scholarship: Don't take this from me, take it from the legendary Richard Lancelyn Green! At a joint conference of the Sherlock Holmes Society and Dorothy L Sayers Society, he said that "Dorothy L. Sayers understood better than anyone before her the way of playing the game and her Sherlockian scholarship gave credibility and humor to this intellectual pursuit. Her standing as an authority on the art of detective fiction and as a major practitioner invigorated the scholarship, and her...Holmesian research is the benchmark by which other works are judged. It would be fair to say, as Watson said of Irene Adler, that for Sherlockians she is the woman and that …she 'eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex.'" We'll go into a bit more detail on some specific examples below, but one important one is that, as Green notes, Sayers was not only a mystery writer but an acknowledged authority on mystery fiction, whose (magisterial) introduction to The Omnibus of Crime, a then-groundbreaking history of the genre of mystery fiction, included a highly regarded section on the influence of Holmes on mystery fiction. She was able to write not just literate detective stories but literate critiques of others' stories and the genre (as collected in the excellent volume Taking Detective Stories Seriously), and as such, the writing she did on Holmes was well received.

She cofounded the (original iteration of) the Sherlock Holmes Society of London: While the current iteration of the Society lists itself as having been founded in 1951, a previous iteration existed through the 1930s, founded as a response to the creation of the Baker Street Irregulars in New York and run by a similar concept- the meeting of Sherlock Holmes fans every so often for dinner at a restaurant. Sayers, who seems to have been much more clubbable than Mycroft Holmes, helped run the Detection Club on corresponding lines as well. (Fun fact, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was invited to be the first president of the Detection Club! However, he refused on grounds of poor health and, either right before or right after he died, the Detection Club met for the first time with GK Chesterton as president.) While the 1930s society didn't last, and Sayers didn't decide to join the newly reconstituted club in 1951, her presence from the beginning was key to the establishment of Holmesian scholarship.

She helped define The Game: Sayers didn't invent The Game, as the use of Higher Criticism in the study of Sherlock Holmes came to be called. (The Game now often refers to something a bit broader than that, but it's a pretty solid working definition to say that it is the study of Holmes stories as though they took place in, and can be reconciled with, our world.) Her friend Father Ronald Knox largely invented it almost by accident- as Sayers described it, he wrote that first essay "with the aim of showing that, by those methods [Higher Criticism], one could disintegrate a modern classic as speciously as a certain school of critics have endeavoured to disintegrate the Bible." This exercise backfired, as instead of finding this analysis of Holmes stories silly, people found it compelling and engaging- and this style of Sherlockian writing lives on to this day in multiple journals. Sayers, with her interest in religious scholarship as well as Holmes, was well equipped to both understand Knox's original motivations as well as to carry on in the spirit in which further Game players would take his work, as we'll see. She also wrote the line that would come to define the tone used in The Game- that it "must be played as solemnly as a county cricket match at Lord's; the slightest touch of extravagance or burlesque ruins the atmosphere." While comedic takes on The Game would never vanish, her establishment of tone has lingered, and pretty much any in-depth explanation of The Game will include her insightful comment.

Some of Sayers's ideas became definitional: Here's a question- what's John Watson's middle name? If you said "Hamish," guess what- you should be thanking Dorothy L Sayers. (When this middle name was used for Watson in the BBC Sherlock episode The Sign of Three, articles explaining its use generally didn't bother to credit her, instead saying that "some believe" or a variation on that.) She was the one who speculated that the reason why a) Watson's middle initial is H and b) Mary Morstan Watson calls Watson "James" instead of "John" in one story is because Watson's middle name is Hamish, a Scottish variant of James, with Mary's use of James being an intimate pet name based on this nickname. It's as credible as any other explanation for that question, but more than that it became by far the most popular middle name for Watson used in fan media. Others of Sayers's ideas include that Watson only ever married twice, with his comments about experience with women over four continents being just a lot of bluster and him really being a faithful romantic who married the first woman he really fell for (the aim of this essay being to demolish HW Bell's theory of a marriage to an unknown woman between Mary Morstan and the unnamed woman Watson married in 1903, mentioned by Holmes in The Blanched Soldier); that Holmes attended Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge (she denied that he could have attended Oxford, having gone there herself- fascinatingly, Holmesians who went to Cambridge usually assert that he attended Oxford! Conan Doyle of course attended neither school); and reconciling dates in canon (making the case that one cannot base a claim for Watson's mixing up on dates on poor handwriting as demonstrated in canonical documents, as it is clear from the similarity of different handwriting samples from different people/stories that they were written, presumably transcribed for publication purposes, by a copyist).

She wrote one of the only good Holmes pastiches: Okay, fine, I'm unusually anti-pastiche, and genuinely do like very few of them, but this is one that I love- and even more than that, it's even a Wimsey crossover! On January 8 1954, to commemorate the occasion of Holmes's 100th birthday (because, of course, he was born on January 6 1854- Sayers was more in favor of an 1853 birthdate but thought 1854 was acceptable), the BBC commissioned a bunch of pieces for the radio, including one by Sayers. You can read it here (with thanks to @copperbadge for posting it, it's shockingly hard to find online), and I think you'll agree it's adorable. The idea of Holmes and Wimsey living in the same world is wonderful, the way she makes it work is impeccable, and it's clearly done with so much love. Also you get baby Peter, which is just incredibly sweet!

I got into Dorothy L Sayers, in the long run, because I loved Sherlock Holmes from childhood and that later launched me into early and golden age mysteries- but it was discovering Sayers that brought me back full force into the world of Holmes. Just an awesome lady.

#hm holmes quotes from shakespeare's twelfth night a lot#he must have an affinity for the play.#sherlock holmes#john watson#john hamish watson#holmes#acd holmes#sherlock holmes canon#sherlockiana#the game#watsonian#biblical higher criticism#dorothy l sayers#lord peter wimsey#ronald knox#sayers on holmes#so why was sherlock holmes born on january 6?#if you think you know why#no it's stupider than that#so this guy christopher morley who basically invented sherlockian scholarly fandom#as in he started the baker street irregulars which is the org from which pretty much all other scholarly fan societies got inspiration#was like “hm”#“holmes sure does quote from twelfth night a lot”#“he must have an affinity for the play.”#“and why would he have an affinity for the play? because the twelfth night (jan 6) is his birthday.”#and so it has remained ever since#making clear the advantages of being first

224 notes

·

View notes

Text

I said I was going to start a Holmes sideblog- here's the closest thing to it!

Too antsy to truly commit to a blog about just one series/writer, but I definitely anticipate a nice chunk of Holmes stuff. Canon, Sherlockiana, some adaptational stuff. Will probably also talk a bit about my journey into the Golden Age. Let's see what happens.

To kick it off- a tiermaker I did of canon stories. All on instinct, did not spend more than two seconds considering each one. I haven't looked at it since I finished it and yet I stand behind it completely.

#sherlock holmes#holmes#acd holmes#acd canon#sherlock holmes canon#sherlockiana#as mentioned in my blog description:#i'm a canon diehard#granada holmes devotee#surprisingly taken with the soviet one#not SUPER au courant with all adaptations#but may do a post sometime to discuss the ones i do know

19 notes

·

View notes