politics broadcast from land that was stolen and never ceded.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

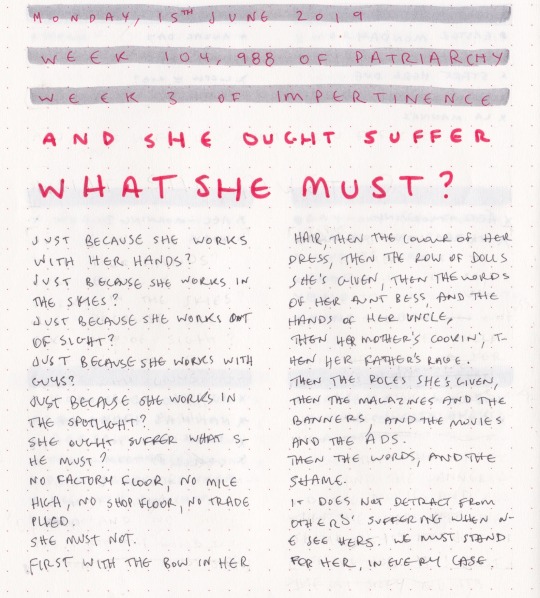

And She Ought Suffer What She Must?

Just because she works with her hands? Just because she works in the skies? Just because she works out of sight? Just because she works with guys? Just because she works in the spotlight? She ought suffer what she must? No factory floor, no mile high, no shop floor, nor trade plied. She must not.

First with the bow in her hair, then the colour of her dress, then the row of dolls she’s given, then the words of her Aunt Bess, and the hands of her Uncle, then her mother’s cooking, and her father’s rage. Then the roles she’s given, then the magazines and the banners, and the movies and the ads. Then the words and the shame.

It does not detract from others’ suffering when we see hers. We must stand for her, in every case. From one bears all – the whole is built from smaller parts. What’s evil permeates not just the worst but much of the mundane.

It’s not okay. It’s not okay in public, it’s not okay in private, near or far, wherever: it is our concern. Her home must be safe. Her street must be safe, her commute must be safe, her work must be safe.

It’s not a matter of personal preference or performance, it’s seeing others with full humanity. We must side with her when she’s yelled at, when she’s cornered, when she’s leered at, and when she’s groped, cut, raped, bashed or slaughtered.

I wrote these words more than a year ago. Reading over them again I feel a bit embarrassed by their forced nature, and my attempt at a poetic structure. I stand by the feelings behind them, and what I think my argument was - that misogyny should be met at all levels with resistance, no matter how trivial. This is because the social structure is pervaded by an ideology of masculine supremacy. There is a connectedness between the trivial and the hyperviolent, and recognising that makes it imperative to alter our behaviour at all levels, if we truly are concerned about the cause of gendered violence.

The context of what I wrote bears analysing too. I put pen to paper after having a heated discussion with a co-worker in 2019, regarding allegations made by an actor, who claimed a co-worker of hers at the time, Geoffrey Rush, had acted inappropriately towards her. It is here that I would link an article describing the allegations, but Australia’s defamation laws are so skewed that none exist and, strictly speaking, I too am beholden to those laws. Suffice to say that the discussion I had with the colleague assumed the allegations true, but this does not detract from the impetus for my writing, after having that discussion.

My recollection is that my co-worker felt that the complainant had overreacted by making a complaint about the alleged conduct. She felt not only that it was not worth making a complaint about, but also that by making that complaint the accuser was detracting from other, presumably more ‘real’, conduct and behaviour perpetrated against women. My colleague also seemed vaguely suspicious of the then emerging ‘#metoo movement’. As I hope is apparent from what I’ve written, I did not (and do not) agree with her arguments. As far as I see it, the victim in this instance, as well as those who spoke up about their own experiences during that time and since, are workers demanding safe working conditions. The end goal of which is not merely to demand that bosses improve those conditions (albeit, this is extremely important), but the end goal should also be worker control of the arts and the banishment of capital’s hold in the industry.

Thinking on the discussion now, my co-worker’s arguments remind me of Helen Garner’s book, The First Stone, which I would recommend to all interested in these issues (even if I do not particularly agree with Garner on much of what she says in that book). In her book Garner investigates allegations made by two students of the University of Melbourne, who alleged that the head of a prestigious college had sexually harassed them. Garner’s book still attracts controversy for some of the conclusions she entertains, and some utterances she makes (particularly in regard to the claimants).[1]

Garner is frank about her initial response to the news,[2] her past encounters with men acting inappropriately,[3] and her feelings about the players involved (the accusers, the accused, and everyone around them). She sways between wanting to understand the young women’s intentions,[4] feeling that they were overreacting,[5] and perversely extolling the polite virtue of the accused and lamenting his lost career. It can make hard reading for the converted feminist (or ally thereof) who believes both in sexual liberation and the existence of a patriarchal social structure. It should also be said, for me at least, the book offers important insight into how a woman, longing for the days of sexual playfulness, has come to feel increasingly invisible.

I recommend it, despite it’s challenging subject matter and defense of arguments I don’t agree with, because it is a well-written and complex analysis of competing schools of thought in modern feminism and criminology. Garner offers compelling arguments in favour both of my co-worker’s view and the more radical approach (I like to think I inhabit).

I share the feelings well summed up by Rachel Hennessy, writing 20 years later for Overland (hard copies of which can be found on many Melbourne university campuses including the one in question). Hennessy describes the experience of reading The First Stone as ‘being betrayed by a good friend’.[6] It is important to read the book because Garner’s ultimate conclusions represent an alternative view of sexual equality that many still hold, and clearly, the dialogue with my colleague is precisely what Garner was grappling with herself, and continues to be debated among those of us who deign to call ourselves feminists.

It is also tangentially an important book for its criminological content. Garner analyses what institutional response ought be taken against sexual violence, and makes interesting arguments about proportionality. We often argue for harsher penalties and sanctions for perpetrators (and understandably so), but this can be uncomfortable for those of us who know that our penal institutions are woefully inadequate to deal with any form of anti-social behaviour. It can be easy to argue for the end to the carceral state and defunding the police when we talk about the wrongly convicted and racialised policing (for instance), but it is far more challenging to argue for those things in the face of what is clearly objectionable conduct. If the state is to be involved in preventing harm (which it should be), does the argument against imprisonment hold true for all crimes or just some of them? Exploration of that question is best left for another time.

What we see from Garner’s book, and what I learnt from my discussion with my co-worker, is that, generationally, as well as politically, we are still divided on the issue. For those of us who have a more absolutist approach against sexual misconduct, it can be confronting to have these discussions. My writings above were an emotional response to what was a challenging dialogue. An attempt to elucidate the thinking that sexual violence is a part of a wider culture, one of misogyny, which finds expression not only in depraved acts of violence (like rape) but also in the mundane gender distinctions (like a man badgering a woman on public transport). If we act on principle that we ought be treated equitably as well as that all are inherently equal, then how is that we justify not resisting the trivial expressions of inequity as well as the more dangerous.

[1] Gay Alcorn, ‘Helen Garner’s The First Stone is outdated. But her questions about sexual harassment aren’t ‘, The Guardian (7 January 2018) <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jan/08/helen-garners-the-first-stone-is-outdated-but-her-questions-about-sexual-harassment-arent>.

[2] Helen Garner, ‘The First Stone’, page 16.

[3] See, eg, ibid page 62.

[4] Ibid page 78.

[5] Ibid 16.

[6] Rachel Hennessy, ‘ Why Helen Garner was wrong’, the Overland (24 July 2015) < https://overland.org.au/2015/07/why-helen-garner-was-wrong/comment-page-1/>.

#auspol#week 5#feminism#criminology#cw assault#tw assualt#cw harassment#tw harassment#sexism#misogyny#patriarchy#intergenerational

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remove All Borders

Our borders are a means for exclusion. It is not by accident that they are deployed as a means to abuse, and, peremptorily, that they attract fear-based politics. Borders, by design, they create an ‘us’ and a ‘them’, and to confer on the ‘us’ certain privileges—to make something valuable about membership of that community and, conversely, undesirable about being excluded. This dynamic is inherent in borders; the solution is in their absolute removal (physically, virtually).

Borders are arbitrary lines, drawn to demarcate a community from others. They are not inherent, a given, nor fixed. Rather, they are created, and usually, designed by the politically powerful. This is true of all borders, whether they cut through Palestine, or divide up Africa. As products of vested interests, it is incumbent on us to analyse the border’s existence and utility.

In our country, the border is a hotly contested political point, and a continuing battleground in the so-called culture wars. For migration purposes, our border is the creature of a legal fiction known as the ‘migration zone’ (s 5 of the Migration Act 1958), devised in response to the Tampa ‘crisis’[1] and to deny the right to seek asylum. The political class uses the border to define the permissible culture as opposed to a deviant one. It is being used to dehumanise and exclude communities on the basis of ethnicity, religion, social class, disability, and political opinion. Our role is to demand the removal of any such demarcation.

Borders as a Means to Withhold

Borders are used to justify withholding rights and justice to communities on the basis of a constructed status. Politicians are fond of saying that it is a privilege for non-citizens to live in the country. In the sense that it is not a guarantee, but a gift, and one that could be taken away. But a privilege differs only from an entitlement symbolically and politically; functionally, they are the same.

It can be said that the privilege to reside in Australia as a noncitizen is conditional on certain circumstances (for example, paying a (sometimes exorbitant) fee,[2] having certain skills, or not having a substantial criminal background). But this does not differentiate it from an entitlement. All entitlement is conditional. It is a political question as to what is deemed an entitlement and what is a privilege, in as much as it is a political question as to what the conditions are for granting either.

Something is described as a privilege when those in power want to withhold it or use it as a means of exclusion. This is because a privilege can be seen as something over and above what is ordinary, and in that sense, is not permanent. For example, social security payments can be split between those that are considered entitlements and those that are deemed privileges. The aged pension is an entitlement (for now), albeit it is conditional (it is asset and means tested, and certain age and residency requirements must be met) but otherwise citizens are so entitled to it. This is because, proverbially, those who receive it, worked for it. Whereas it is considered that unemployment payments ought to be restricted because those who receive it are thought of as idle and lazy (leaners, not lifters, or, in the new parlance, they haven’t had a go so they don’t get one). The mere language of what we call these types of payments tells you how they’re viewed: temporary states, the purpose of which is to exit you ought of them, to get a new start or to find a job. You are told that you’re not meant to be on them, and they can be (and often are)[3] taken away from you.

Similarly, migration visas are said to be privileges. They are deemed to be gifts, given to migrants from the executive (ie, the government as opposed to the courts or the parliament). This is because thinking of it as a privilege allows those bestowing the gifts to decide worthiness and make value judgments about those who are ‘deserving’. It also makes them seem like something extraordinary, not the usual situation and not be considered permanent or continuing. Similar moves have been tried by the government to make citizenship a non-permanent state, this is in regard to dual citizenship holders who might have their citizenship cancelled if it is later found they lied on their applications.

The task for the left is not to give in to the rhetoric of privilege, which exacerbates the notion of worthy and unworthy classes, often demarcated by the person’s birth on either side of an arbitrary border. A privilege is the creature of the prerogative and executive power (which relies on vague notions of ‘sovereignty’ and ‘community expectations’, see, eg, Direction 79).[4] This kind of power is akin to benevolent despots, quite literally described as ‘God Powers’ (see the report by Liberty Victoria, and discretionary powers in the Act summarised on page 6 at footnote 26).[5] The growth of such powers is untenable in a democratic society, in which the people are meant to be sovereign, but increasingly abdicate decision-making to discretion and mercy.

Borders are Undemocratic

The approach to treating migration as a privilege was summed up by John Howard when he asserted: ‘we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come’ (stated in an election speech in 2001, see here).[6] The power to grant a visa allowing a person to lawfully remain in the country, and the control of our ‘borders’ is said to be the ‘prerogative’ of the government. That is, a right exclusive to a particular class — the white settler government meant by the word ‘we’ in Howard’s assertion (indigenous peoples ought to roll in their graves at the thought of this ‘prerogative’).

Conceptualising migration as the function of executive grant, and a privilege (not entitlement) of those on visas, leads to a system of insecurity for migrants, and extraordinary power, for those who grant it (ultimately, the minister within a government only very indirectly elected by the people). Much more than with social security, receiving and maintaining the gift is the product of the whim and fancy of a singular man.[7] And it is ever-subject to being withheld or revoked for political expediency and fear-mongering (although this is not to say social security doesn’t have some of the same problems). Ceding this power to the realm of discretion belies the dignity of the people subject to it, and squarely on the basis that they are not citizens.

This power relationship, between omnipotent minister and second-class resident, is actively encouraged and protected by the major political parties and most media organisations. One of the powers of the minister has, is that people’s visas can be refused or cancelled for crimes that they’ve either committed years in the past or for which they’ve served their sentence for. Sometimes, the person has lived in and grown up in this country for the substantial part of their life, and yet somehow, we have no responsibility to rehabilitate them nor do we accept any responsibility for having helped produce the conditions in which they were led to criminal behaviour. We are told that such powers are necessary to protect us, that we must spend millions of dollars on military equipment, private security firms, secret international deals, legal battles and publicity stunts, all this because we’re supposedly under threat. But we can’t be told by what, and from whom, we are under threat because those are national security matters. All the while knowing that the target audience for this doom-saying will hear the dog-whistle and draw their own conclusions.

Borders are a Distraction

The idea that we need borders is a function of our political system and the design of a political class that likes to tell us that we have to protect some perceived ‘way of life’ from the supposed undeserving, dangerous and opportunity-seeking migrants. Acting Minister for Immigration, Alan Tudge, recently gave a speech (here) in which he extolls the virtues of ‘social cohesion’, and Australia’s supposed strength in this regard.[8] But that’s a farce. Even the Acting Minister can’t help but remind us that the benefits of that cohesion are only for those ‘who have a go’ (‘lifters’). Migration is transactional for Tudge, the born-Australians must benefit from the arrived-Australians (there must be a tit for tat). And yet we are reminded of apparent ‘egalitarianism’ that those European settlers brought here, but it goes without saying that that egalitarianism wasn’t expanded to those already living in this country nor is it delivered to the younger generation (now paying more for uni fees and with less money).[9]

Leaving aside those hypocrisies, Tudge’s speech tells us that we are being protected from threats to ‘cohesion’ including: the global pandemic and the obliquely styled ‘foreign interference’ (read: China). On par with these threats, amazingly, is ‘poor English skills’. The Big Other rears its ugly head again. Participation in society is conflated with getting a job (those pesky leaners again), and we are told that lack of English will dampen participation in democracy (although he neglects to state how). One can only assume participation in democracy, in Tudge’s mind, has been reduced to the mere act of voting and choosing between two parties (predominantly made up of individuals from outside the communities of these newly arrived migrants, both culturally or economically-speaking). It is not established what level of English proficiency is required in Tudge’s mind, more importantly, how lack of English is getting in the way. I ask, can they make demands with their fellow workers for better conditions? Can they share ideas with their friends and family? Can they meet new people at festivals or shops and the like? Can they tell medical, legal, and other professionals what they need? If yes, then they are participating in our democracy.

This way of life that is supposedly under threat, it is nowhere near as good as claimed. Whether that border is the literal one (somewhere off the coast of Australia, but meticulously legally defined), or in our pockets, through a device beaming information via a tunnel of wiring (albeit a sub-par mix of copper and fibre wiring), it is not worth defending. The threat comes from within, not from outside culture or any apparent overpopulation. In particular, the threat is from a political consensus on corporate-led growth (primarily, the pillage of non-renewable and damaging resources), austerity (for the ‘leaners’), privatisation, and a valorisation of the individual contra society. The border hasn’t protected us from any of that (nobody tries to tell us that Milton Friedman or Friedrich Hayek are outside agitators). Conveniently, there appears to be no border strong enough to keep companies’ tax obligations within it. We can’t even seem to exercise democratic control over the use (and abuse) of our natural resources and sacred sites.

Conclusion

The border is a construct (figuratively and literally), the purpose of which is to convince us that resources ought to be spent on maintaining it, so that we may preserve some unnamed prosperity—sometimes it even protects ‘liberal, democratic values’ although I’m not sure which ones—and so we don’t ask for that money to be spent elsewhere. What good are liberal values if the people cannot choose what language they speak or religion they practice. And what good is democracy if the people can’t collectivise their workplace or stand in concert to demand action on the existential global crisis, to democratically control their cultural resources, or withhold public resources from agents of social control.

1. Australian Parliament House, Bills Digest No. 69 2001-02, Migration Amendment (Excision from Migration Zone) Bill 2001, 26 September 2001 < https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd0102/02bd069>.

2. Department of Home Affairs, (Subclass 143) Contributory Parent visa < https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/getting-a-visa/visa-listing/contributory-parent-143>.

3. Luke Henriques-Gomes, Jobseekers had payments suspended for breaching rules in faulty job search plans, The Guardian, 25 October 2019 < https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/oct/25/jobseekers-had-payments-suspended-for-breaching-rules-in-faulty-job-search-plans>.

4. Direction 79 isn’t publicly released, but is used to deny people rights and remove them from the country.

5. Playing God, 4 May 2017 <http://libertyvic.rightsadvocacy.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/YLLR_PlayingGod_Report2017_FINAL2.1-1.pdf>.

6. John Howard, Speech deliver at Sydney, 28 October 2001 <https://electionspeeches.moadoph.gov.au/speeches/2001-john-howard>.

7. For instance, see n 3 above, the job provider network where corporations receive millions in public funds to ‘breach’ recipients who have permanent disability on the basis that they failed to lodge 20 job applications that would never have been read and for jobs they’d never be able to perform.

8. Alan Tudge, Keeping Australians together at a time of COVID, Address to the National Press Club, 28 August 2020 <https://minister.homeaffairs.gov.au/alantudge/Pages/Adress-to-the-National-Press-Club---.aspx>.

9. Leo Crnogorcevic, Stop Dan Tehan’s efforts to gouge students, Green Left, 27 August 2020 <https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/stop-dan-tehans-efforts-gouge-students>.

0 notes

Photo

Every war, conflict, disaster. What use is progress and its principles, if countless have been exploited by an invisible, objective violence? A true humanitarian approach, with respect for the inalienability of others, must begin with criticising the past and end with commitment to a better way.

0 notes

Photo

History and Background

The Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (the Act) was introduced on 21 March 1984 by the Hawke Labor Government. It makes up part of Australia’s sparse legal framework for protections from discrimination, including on the basis of sex, race, age and disability (and religion, if the current government gets its way).

The Act gives effect to Australia’s obligations as contained in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and seeks to

‘eliminate discrimination against persons on the ground of sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status, marital or relationship status, pregnancy or potential pregnancy or breastfeeding in the areas of work, accommodation, education, the provision of goods, facilities and services, the disposal of land, the activities of clubs and the administration of Commonwealth laws and programs’ (section 3 of the Act).

In 2013 the then Gillard Labor Government amended the Act to introduce the words ‘sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status, marital or relationship status’, replacing the previous version which only referred to ‘marital status’. At the time, the Attorney-General, Mark Dreyfus MP, explained that the intention was to introduce three new grounds of discrimination that would be protected: sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status.

However, at the same time the amendments also extended the exemptions to these prohibitions, which Dreyfus called ‘legitimate’ differential treatment, in the aid of protecting the right to freedom of religion for parents and educational institutions established for religious purposes (as found under article 18(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)).

The result was that while protections existed for Australians on the basis of these attributes, extension was also granted to the existing exemptions for bodies established for religious purposes, including religious schools. Sections 35, 36 and 50 of the Sex Discrimination Amendment (Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Intersex Status) Act 2013 (the Amendment Act) allowed for single-sex educational institutions and educational institutions established for religious purposes (under subsection 21(3) and section 38 of the Act) to discriminate against students (or prospective students) on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status or pregnancy.

On 29 November 2018 Senator Penny Wong introduced an amendment, titled Sex Discrimination Amendment (Removing Discrimination Against Students) Bill 2018 (the Bill), which sought to undo these exceptions for education institutions established for religious purposes.

Clause 1 in Schedule 1 of the Bill limits the exception in section 21 of the Act, which makes it unlawful for bodies established for religious purposes (that are also educational authorities) to refuse, or fail to accept, a person’s application for admission as a student on the ground of the person’s sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, intersex status, marital or relationship status, pregnancy or potential pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Clause 2 of Schedule 1 of the Bill removes entirely subsection 38(3) of the Act, which would make it unlawful for an educational institution to discriminate against students because of those attributes regardless of the religious susceptibilities of adherents of the doctrines, tenets, beliefs or teachings of the particular religion or creed of the school.

Current Controversy

As Senator Wong explained, the Coalition Government, the Labor Party, the Australian Greens and cross-bench parliamentarians agreed that the Act must be changed to prevent any school from discriminating against students (Paul Karp, The Guardian, 13 Oct 2018). Wong acknowledged that the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee looked into these provisions and received evidence from schools that they did not want the exemptions that allowed them to discriminate against LGTQI+ students (Legislative Exemptions that Allow Faith-based Educational Institutions to Discriminate against Students, Teachers and Staff, November 2018, pp 27-30).

Despite this, the changes introduced were met with fierce criticism and outrage by religious fanatics and conservative commentators (here, here, here, here and here to name a few). No semblance of liberalism or pluralism was to be found; and no concern for the health and well-being of LGBTQI+ children was to be found. Despite evidence that LGBTQI+ kids are harmed by such discrimination (see Lynne Hillier et al, ‘Writing Themselves in 3: The Third National Study on the Sexual Health and Wellbeing of Same Sex Attracted and Gender Questioning Young People’, 2010). Despite the overwhelming public support for removing the exceptions; 74 per cent of ‘voters oppose laws to allow religious schools to select students and teachers based on their sexual orientation, gender identity or relationship status’.

I have seen dozens of emails - and received a few phone calls - from people virulently opposed to any changes to the Sex Discrimination Act. They mistakenly believe that the changes are an assault on the power of religious schools to teach their faith. They screech about the rights of parents to exercise their religious beliefs. They demand, in capital letters, to be given an explanation for this incursion. Nobody considers the rights of the children to access education safely. And the conservative media, with the Government and its flurry of amendments, perpetuate the misrepresentation that the amendments proposed by Wong would remove the right of schools to teach religion. As demonstrated above, Senator Wong’s amendments are targeted to one purpose: removing the right to discriminate against students on the basis of their LGBTQI+ status.

But Labor Senator Kimberly Kitching, speaking on the Bill, thought it necessary to appease these people:

‘An essential part of religious freedom is the right of parents to send their children to religious schools. It must follow from that that religious schools, whether those schools are Christian, Jewish, Islamic or indeed anything else, have a right to educate their students in a way that encourages them to adhere to the faith and practices of the religious denomination which established them’.

Senator Kitching supports the Bill, obviously, but made no mention of the impact that such protections of the sensibilities of religious people (and institutions) has on the physical and mental health of the students and children who would be subject to discrimination. The children, after all, are the ones with the least amount of power to control their lot; with the weakest capacity to stand up for themselves; and are the least equipped to be resilient in the face of violence and discrimination. In short, they are the most in need of protection by the power of the law.

On the other hand, Senator Janet Rice of the Australian Greens reminds us of the need for:

‘every child and teacher in Australia [to have] the comfort to know that they will be respected and loved and treated equally, simply because of who they are, not because of some outdated legislation that sends a message, not just to them but to all people, that somehow the way they are is wrong or different’

And importantly, that ‘harmful attitudes, made acceptable to some in the guise of religious ethos, effectively destroy LGBTQ lives’.

Citing a study conducted by the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society at La Trobe University, the Human Rights Law Centre, in its submission to the Senate inquiry into these exemptions, stated that ‘same-sex attracted and gender questioning young Australians with a religious background were more likely than their non-religious peers to’:

report self-harm and suicidal ideation;

feel negatively about their same-sex attraction;

have experienced social exclusion;

have been subjected to homophobic language from friends; and

report homophobic abuse and feeling unsafe at home (pp 8-9).

There is no doubt in my mind that these alterations to the Sex Discrimination Act, and many more, are absolutely necessary to protect and improve the well-being of LGTQBI+ kids and teachers. No right to believe something, even if it is a religious belief, should trump society’s obligation to the most vulnerable and to the health of its constituents. The right to freedom of conscience contains more than one part: it includes the right to act (or refrain from acting) in accordance with the conscience, as well as the right to hold a particular belief. But those parts are protected differently. When the right to religion collides with the rights of another, as rights so often do, what occurs should depend on the nature of the right.

As a society, it is beholden on us to commit to protecting the right to health of one before the protection of religious susceptibilities of another. There is no doubt that the spiritual, inner life of everyone deserves to be protected, but the basic right to survival is paramount. Surely this is especially so in the case of children who, by their nature, have a reduced capacity to fend for themselves and whose trauma will irreparably alter the rest of their lives. Because of this, if the right of one person to act according to their religious beliefs is at risk of harming another person, that action must be prohibited. The right to health trumps the right to act according to a religious belief, but not the right to hold that belief (albeit, the belief is probably hideously outdated if acting on it risks harming people).

Critique of Rights

While I believe in the absolute necessity of changing the Sex Discrimination Act to protect the well-being of students, it must be acknowledged that the law (even with Wong’s amendments) and all of Australia’s anti discrimination acts are wholly inadequate to deal with social inequality.

Legal rights, such as human and civil rights like those found in international treaties like the ICCPR or CEDAW, are primarily liberal, bourgeois rights. They offer formal protection for individuals from Government action on the basis of certain statuses or attributes, and largely do not provide for positive actions to undo material power imbalances. As such, they are loathed by both the right and left of the political spectrum.

From the socially conservative right because they seek to remove formal barriers for groups of people, such as women, people with disability, people of colour, to liberal, bourgeois institutions. For example, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (US) which attempted enfranchise African Americans in state and local elections provided for access to voting to a previous marginalised group on the basis of race. For the economically progressive left human and civil rights are preoccupied with providing equality within existing liberal institutions and capitalist structures, and do not offer much in terms of empowering workers on the basis of class status. Returning to the Voting Rights Act, while removing legal barriers for African Americans to vote in state and local elections in the US, it is wholly inadequate to remove the structural inequities of the US economic and political system which remained - there were no reparations for the horrors of slavery, and no alterations to the electoral college system (an antidemocratic and racist institution which grants undue power to the less populace states).

The Sex Discrimination Act can be criticised in the same way. It merely provides for the legal right for individuals to sue the Government, a Government agency or body, or certain government funded institutions, for discrimination on the basis of certain attributes and statuses. This preserves the institutions of the judiciary, the courts and their conservative judges and legal professionals; ignores the material disadvantage of individuals most harmed by sex discrimination and their inability to enforce any legal right; and provides for no positive obligation on the Government to rectify existing imbalances that may exist as a result of decades of discrimination that had previously been permitted.

Going Forward

The conservative Morrison Government has announced that it will refer the question of discrimination against students to a review by the Australian Law Reform Commission, and instead will focus on creating a Religious Discrimination Act, akin to the Sex Discrimination Act and others, which will provide for standalone protections for freedom of religion. This is supposedly in response to recommendations within the Ruddock Review into Religious Freedom (handed to Government on 18 May 2018, and publicly released seven months later on 13 December 2018). It’s disgusting that these amendments were made in the first place - a mere five years ago by what’s meant to be the more progressive of the major Australian political parties. But the current Government is being even more duplicitous. In order to win voters who lent more socially progressive in one electorate, the Prime Minister promised action. After losing the by-election anyway, the PM has dropped the promise altogether. We can’t be surprised though that Morrison doesn’t see the urgency in protecting the well-being of children and the right to health - this is the same PM who prays and cries for people he put into detention and subjects to cruel punishment. Despite his sorely and fiercely protected Christian beliefs (which he will sell out at every opportunity he can), Morrison is the person with the most power to stop the suffering of both LGTBQI+ kids and the children of asylum seekers on Manus and Nauru, and yet he does nothing. Save your fucking prayers. I’ll defend your right to conscience (and those religious parents and schools) when you find it.

#lgbtqia+#lgbtq#lgbt#lgbti#sex disxrimination act#sex discrimination#australia#auspol#human rights#civil rights#socialism#week 2

0 notes

Photo

The intention of this blog will be to document a leftist critique every week that centers on an issue of Australian or world politics that has angered me over that week. Wherever relevant and applicable, I endeavour to embody my critique with socialist, and feminist values, and to avoid racism, ableism, ageism, homophobia, and transphobia. I fully expect to falter on this endeavour. I will be impertinent until I am satisfied.

2 notes

·

View notes