Inverts need a little love. If you have ever thought that anything without a backbone is a little bit boring - I just want to say that I was you once, too. Give me a little bit of time, and I hope to change your mind.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

How can a molecular analysis include a taxon that’s been extinct for 250 million years?

Excellent question! They can’t.

I should not have said genetic, I should have said phylogenetic. The analyses I was talking about use morphological characters in leiu of DNA.

Thank you for calling me out - I have corrected the post!

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

@drawingwithdinosaurs

If they are sister groups, wouldn’t that still leave them as stem-horseshoe crabs in the wider sense?

To further elaborate after a bit more reading…

If eurypterids and horseshoe crabs are more closely related to each other than they are to the rest of the chelicerates (Merostomata), then yes, eurypterids would be considered stem-horseshoe crabs. It’s common to still see this theory floating around.

However, phylogenetic analyses now suggest that Merostomata is an unnatural grouping, and that eurypterids are more closely related to arachnids than to horseshoe crabs (e.g. Lamsdell et al. 2015).

Are eurypterids still considered stem-horseshoe crabs?

No - I think they are usually considered sister groups, instead. It’s also debated as to whether eurypterids are more closely related to horseshoe crabs or arachnids.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you recommend any general audience books on arthropod evolution?

TBH... no...

I have been more of a journal reader than a book reader, but I am in the process of trying to change that. So if I come across anything I will be sure to share it!

Do any other followers have any recommendations?

1 note

·

View note

Note

Don’t pentastomidans sometimes end up as non-arthropod ecdysozoans?

I’ve not heard that before. Maybe they used to?

A quick google scholar search seems to suggest most molecular analyses agree they are of the class or closely related to the class maxillopoda.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Are eurypterids still considered stem-horseshoe crabs?

No - I think they are usually considered sister groups, instead. It’s also debated as to whether eurypterids are more closely related to horseshoe crabs or arachnids.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can we have a series on invertebrate taxa & clades with lazy, unfortunate or otherwise bad names? *cough*Vaginoceras*cough*

This is such a great idea! Absolutely!!

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can we have a series on echinoderms & invertebrate chordates?

Of course!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Giants - Part 11/11

Synapta maculata - also known as the snake cucumber. Despite looking like a snake, it is in fact a giant (or at least very long) sea cucumber. It can grow up to 3 meters long and lives in the Indo-Pacific Ocean. Sea cucumbers are pretty famous for ejecting their internal organs to scare off or distract predators, however S. maculata instead just splits in two and re-grows the rest of its body at a later date.

Ꞓ - O - S - D - C - P - T - J - K - Pg - N

Image Credit: NOAA 2010

#palaeontology#invertebrate palaeontology#palaeoblr#paleontology#neogene#the giants#sea cucumber#holothurian#echinoderm#science#sciblr#biology#bioblr#marine biology

256 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are pentastomidans?

They are a subclass of parasitic crustaceans also known as “tongue worms” because they all look a lot like worms and a few of them kinda look like tongues. Their formal name (pentastomida) comes from their five appendages - one of which is actually a mouth and the other four are hooks that they use to cling to the respiratory tracts of their vertebrate hosts.

Like other crustaceans, they are chitinous - so even thought they might look kinda squishy, they aren’t (at least I don’t think they are, I haven’t touched one). They are in the class Maxillopoda along with copepods (think Plankton from Spongebob) and barnacles.

Images from Tappe & Büttner 2009: [x] [x]

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Giants - Part 10/11

Titanomyrma - a Paleogene ant the size of a hummingbird. Well, the queen could grow to the size of a hummingbird, i.e. around 6 cm. Worker ants of this genus are yet to be discovered in full. Members of this genus have been found in the Green River Formation in Wyoming and the Messel Shales of Germany.

Ꞓ - O - S - D - C - P - T - J - K - Pg - N

Image Credit: U. Kiel 2011

#palaeontology#paleontology#invertebrate palaeontology#palaeoblr#fossil#fossils#paleogene#the giants#ants#hymenoptera#science#sciblr#geology#biology#bioblr

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

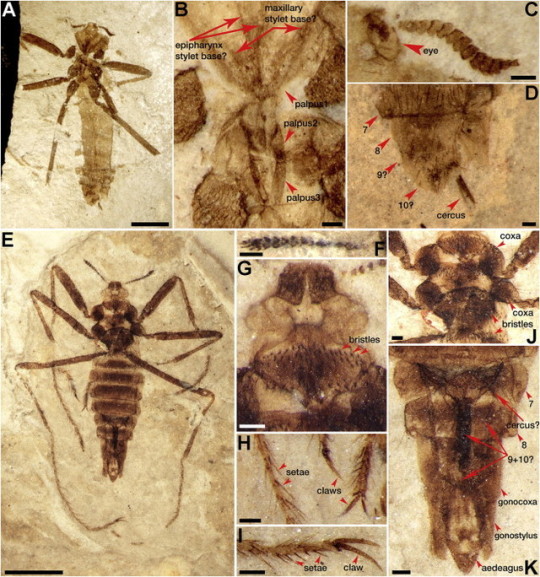

The Giants - Part 9/11

Saurophthirus - at 2.5 cm long, Saurophthirus is not actually very big. But when you realise that Saurophthirus was a flea (!) from the Cretaceous that fed on the blood of dinosaurs and pterosaurs... it kind of changes your perspective. Saurophthirus was the largest flea to have ever existed (for reference, extant fleas can grow up to 2.5 millimetres). Although I don’t know an estimate for how high they could jump, their long legs suggest that like their extant descendants, they were also very good jumpers.

Ꞓ - O - S - D - C - P - T - J - K - Pg - N

Image Credit: T. Gao & team 2013

#palaeontology#paleontology#invertebrate palaeontology#palaeoblr#fossil#fossils#the giants#arthropod#cretaceous#insects#science#sciblr#biology#bioblr#geology

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Giants - Part 8/11

Inoceramus - an extinct genus of bivalves that originated in the Jurassic, within which is the subgenus, Platyceramus, aka. the largest bivalves of all time. They could reach up to 3 m wide, meaning they could grow considerably larger than the giant clam (Tridacna) which is know to grow up to 1.14 m.

Ꞓ - O - S - D - C - P - T - J - K - Pg - N

Image Source: [X]

#palaeontology#invertebrate palaeontology#palaeoblr#paleontology#Jurassic#mollusc#bivalve#fossil#fossils#the giants#science#sciblr#biology#bioblr#geology

115 notes

·

View notes

Note

How did cephalopod beaks evolve?

I have not forgotten bout this question - sorry it has taken so long for me to get back to you.

Cephalopod beaks are readily found throughout the Mesozoic in fossil coleoids (i.e. octopus, squid, belemnites), but there doesn’t appear to be many beaks preserved in more basal cephalopods.

Beaks allow cephalopods to break open prey, i.e. crustaceans and other cephalopod shells. So if we consider the fact that nautiloid cephalopods were among the top predators in the Ordovician, and throughout the period we have plenty of evidence of shell crushing, we can make the assumption that a beak or some kind of hardened jaw was present in Ordovician nautiloids.

Exactly what happened between the beaks (or beak-like jaws) of the Ordovician and the beaks of the Mesozoic (which are very similar to the beaks of extant cephalopods) is still unclear... to the best of my knowledge.

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

It’s also worth noting that scaphopods have tentacles…

Absolutely - the Variopoda clade is certainly not without its merits.

Early scaphopods and cephalopods share the obvious similarities such as the elongated shell and tentacles, but also strong similarities in their nervous system architecture.

They are also a little bit different in that scaphopods have two shell openings, while cephalopods only have one. Cephalopods also have a well defined head region, while scaphopods do not.

Re: this post about mollusc cladistics

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

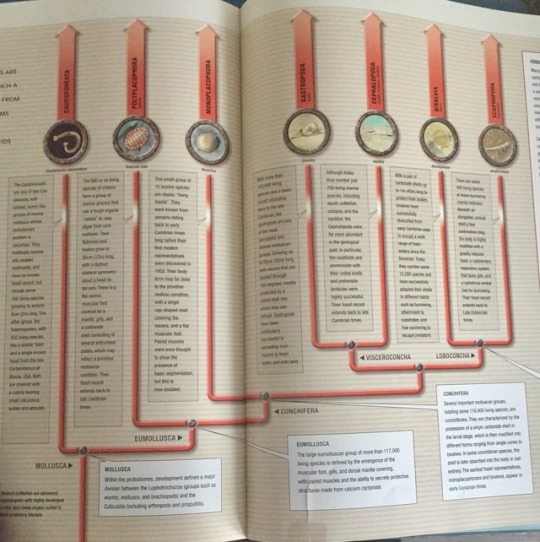

Adam asks:

How does this mollusk cladogram hold up?

As a disclaimer: molluscan cladistics is a rabbit hole that we will probably never escape from. It get’s messy. So the very short answer would be: who knows?

But that isn’t helpful. So instead I will say: it’s not proposing anything that hasn’t already been proposed, and you could definitely find a paper with evidence (not necessarily good evidence) for why that is a very reasonable cladogram. It is very much based on morphology, and we have new genomic data that suggest differently, so I would say it is quite outdated.

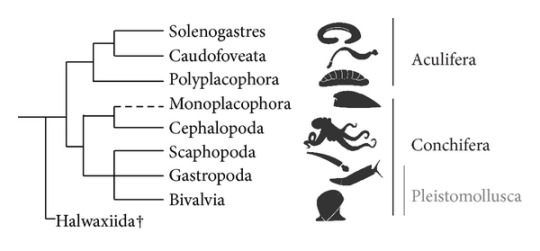

I have never heard “Eumollusca” as a clade before, but it is the same as Testaria, which I have seen proposed. It was formed based on the idea that aplacophora (caudofoveata) don’t have shells, while the rest of the molluscs do. But that isn’t really supported by genomic data. It would be better if caudofoveata and polyplacophora were put into their own clade, Aculifera, besides Conchifera.

The way they divided up Conchifera is also questionable, but not unreasonable. It’s pretty common to see cepahlopoda, scaphopoda, gastropoda and bivalvia put into their own clade, excluding monoplacophora. Likewise, a clade consisting of cephalopoda and gastropoda is supported by features such as their well defined head region (cephalisation). However, there is growing evidence that monoplacophora and cephalopoda are sister taxa - firstly this has been suggested by some genomic studies, but also by the fossil record that suggests they had very similar shell strucutres.

(From Stöger et al. 2013)

The above cladogram currently seems to be the most well supported, e.g. Smith et al. 2011 and Kocot et al. 2011 (both using a genomic analysis). Kocot et al. further proposed Pleistomollusca (labelled), consisting of gastropoda and bivalvia, while Smith et al. instead proposed that scaphopoda and gastropoda should form their own clade.

We can mess things up a bit more if we consider a study by Stöger et al. (2013) that instead came up with this...

Unfortunately, analysing different genes gets you different results. Then I guess we have to ask which genes are going to get you the most accurate results? At that point I have absolutely no idea. I have done very little genomics and wouldn’t even know how to start assessing the accuracy of different methods.

#palaeontology#invertebrate palaeontology#palaeoblr#paleontology#science#fossil#cladistics#cladogram#phylogenetics#biology#genetics#evolution#mollusc#submission

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Giants - Part 7/11

I struggled to find a giant for the Triassic, so thought instead I would explain why there were no giants in this period. It’s thanks to a phenomenon known as the Lilliput effect. Following a mass extinction or disturbance event, we see a reduction in the relative body size of the surviving organisms. In some cases, larger species were just more likely to go extinct than smaller species. However, it is also observed that animals just start growing smaller (e.g. the Permian extinction was the result of global warming. Global warming = ocean acidification = less carbonate ions in the water = calcifying organisms, i.e. gastropods and bivalves, can’t grow as big as they could before). This phenomena is not just limited to invertebrates. For example, land mammals saw a reduction in size during the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum.

So then why do we see giants during other periods following mass extinctions? The Triassic begins after the end-Permian mass extinction, the largest ever mass extinction which resulted in a species loss of up to 90%. While some groups of taxa were certainly affected more than others, it was pretty devastating across the board. Meaning there were no groups that came out relatively unscathed and the Lilliput effect is observed in a huge range of species.

Ꞓ - O - S - D - C - P - T - J - K - Pg - N

Image Credit: R. Twitchett 2007

#palaeontology#paleontology#invertebrate palaeontology#palaeoblr#mass extinction#triassic#biology#science#bioblr#sciblr

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@lokeroze

can u explain how the shells effect boyancy?

Not all of the shell is taken up by tissue, only the outermost chamber (which I guess I should have mentioned is the other thing that separates cephalopods from other molluscs). The rest of the chambers are filled with gas, making it buoyant. The siphuncle (a tube of tissue running throughout the shell) is used to exchange gases throughout the shell and enable the cephalopod to have a bit more control over its movement.

Eleven days of cephalopods

Plectronoceras - a Cambrian organism proposed to be the first cephalopod. Cephalopods likely evolved from a monoplacophoran-like ancestor, sharing characteristics such as having a benthic habitat, restricted movement ans a single shell. What sets cephalopods apart from monoplacaphora and other molluscs is the siphuncle in their shell, used to control boyancy.

Ꞓ - O - S - D - C - P - T - J - K - Pg - N

Image Credit: Apokryltaros 2014

If you have an invertebrate clade you particularly like and want me to cover their evolution next, I am open to suggestions!

280 notes

·

View notes