Link

story about music #8

Winter-Spring, 2013: In order to graduate, I needed a capstone. I chose to do deep reporting project I’d been threatening to do since 2009, and looked into the noise and experimental scene of New England. I recorded seven interview with experimental artists about their lives and work. These are five of them. They were taken in a variety of locales in the Boston area: Cambridge, Somerville, Lowell, and Salem.

In the last year, I’ve been thinking a lot about this period and these conversations as I ask myself, why keep doing this?

above: Ron Lessard, as Emil Beaulieau, performs in someone’s basement in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Music

Music for this episode was created using the following household objects: a desk lamp, a can of beer, a record player, a radiator, and a vacuum cleaner.

With the exceptions of “Fog in the Ravine” by Lejsovka and Freund as well samples from their songs “From Royal Ave” and “Nothing, Just Looking at the Moon” and the song “Blue Line Homicide” by Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck.

The soundtrack was created with advice from musician Jacob Rosati. It will be made available for download later in the summer. For more info please subscribe to the podcast, tumblr, or follow us on twitter.

Links

Crank Sturgeon still performs and tours regularly. He also builds contact microphones and other circuit bent sundries, one of which was used in the production of this episode. A full recording of his set used in this episode is available here.

Crank Sturgeon, 2012, from Wikimedia.

Shane Broderick spent most of his twenties making music with his friend Ted (and later, their friend Josh Hydeman) under the name Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck. Their music is a good example of the subgenres Grindcore and Power Electronics. The name is also exemplary of those subgenres. The performance video which is referenced in the documentary, taken in the mid-00s, has been removed from Youtube. A video from that period is visible here, uploaded by the band’s Ted Sweeney. (contains nudity)

Shane Broderick, from Existence Establishment

Ron Lessard still runs RRRecords in Lowell, Massachusetts. He previously performed under the name Emil Beaulieau. A collection of performances, including the one used in the documentary, can be seen in the video compilation below.

youtube

Emil Beaulieau: America’s Greatest Living Noise Artist, from Youtube

Andrea Pensado still makes music and performs live. She composes in Max/MSP. Her most recent release is a pair of live collaborations with Id M Theft Able. Her former project, with Greg Kowalski, is QFWFQ.

youtube

Andrea Pensado live performance, 10-13-13, from Youtube

Angela Sawyer owned Weirdo Records until it closed in 2015. She now performs comedy and experimental music around Boston.

Angela Sawyer, from her personal website.

The interview with Andrea Pensado was recorded along with my friend Samira, who was producing her own documentary of Boston’s experimental music scene, below. It includes footage from the Andrea interview as well as her own separate interview with Angela Sawyer.

youtube

“The Noise” by Samira Winter, from Youtube

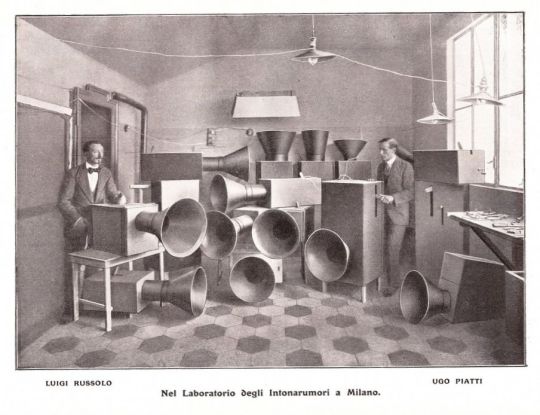

Luigi Russolo’s manifesto is The Art of Noises

Luigi Russolo and the Intonarumori, with his asst. Uglo Piatti, from Wikimedia

Transcript

Brendan: Would you mind telling me about the show at [withheld] , from six years ago, down the street?

Shane: Yeah, um, I was setting up a show with some old-school Detroit noise dudes. When we showed up, the owner was there instead of the doorman, and he was just upset cause he was there on, like, a Tuesday night.

So what ended up happening was is, uhh, two bands played and he came up to me a said, “show’s over.” “Well there’s still two bands to play,” and he’s like, “I don’t care, the show’s over.” I’m like, “the show’s been booked for two months.” Just because you want to go home and, like, jerk off into a kleenex or whatever it is that you fuckin’ do. It has nothing to do with me. And he got upset, and I was like, well listen dude, how about the last two bands play at the exact same time.” So that’s what we did. Warmth and Twodeadsluts collaborated. It lasted about fifteen seconds, and the owner came over and kicked a table with everyone’s gear on it. So the only logical thing for me to do as a Bostonian–– and I have pride being a Bostonian–– is I just looked at this guy and I was like, “I don’t care how big he is, or how Italian he is, I’m gonna wind up, and I’m gonna punch this guy right in the fucking face.”

Brendan: And what happened?

Shane: That guy hit me back––I-I lost a little bit of time there. He’s a lot bigger than me. Uh, clocks went still. I kinda woke up, I was on the ground, and he was smashing everyone’s gear. Cops came in, they put me in a car, they, y’know told me to leave and blah blah blah.

Brendan: Is that the only time cops have been called on you?

Shane: No. Not even close.

music: “Blue Line Homicide” | Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck

You’re listening to Stories About Music, a podcast on the subjects of music, journalism, and memories, and how the line between those three things is often not as clear as I’d hoped.

My name is Brendan Mattox, and this is story about music number eight, “Who’s Afraid of the Art of Noise?”.

Room 1 (Crank Sturgeon)

Cars pass by on Massachusetts Avenue, seen out the front window of Weirdo Records in Cambridge. It’s night time. A few young men in their twenties sit on the floor of the small storefront, waiting as Crank Sturgeon sets up in a corner.

Crank: Cool. So, do you think this is our show? Shall we wait, or?

Angela: I think…What time is it? It’s not eight-thirty, that’s probably most of our show. Let me turn that off.

Crank: Not that uh, four’s a wonderful audience, I’ve played for two. One of them was my brother who never saw me before that point…and Id Em Thft Able and I had some very bizarre sexual ritual in front of my brother, involving instant powdered milk and a plastic poster from 1970 of this naked woman holding a stuffed animal…And I had a penis helmet at the time… but alright, well I will perform for you hello, my name is Crank Sturgeon everybody… (6:37) We could do a performance where I have everyone sing introductions of themselves to each other. Everyone up on your feet.

Crank: Hello! My name is Craaaaaaannnk Sturrrgeon!

Angela: Hello! My name is Angela Sawyyyyyeerrrrrr!

Crank: All at once now!

Brendan: And I am Brendan Mattox!

Crank: Hi Brendan Mattox, my name is Crank, it’s a pleasure to meet you, you have a really firm handshake. And this man in the corner, what’s your name? Andrew, another Andrew, Brendan, Angela.

Angela: Wow, we’re nearly phonemes.

Crank: Ahh, phonies…

Crank Sturgeon sits down behind his instruments: a few tape recorders, a sharpie, and a loudspeaker full of tacks and jelly beans.

Crank: First Piece, oh, wait. My brand new fish helmet, so I can lose even more water to my body. There we go. First piece is improvisations with the letter D. Delirious, Delightful, Delicious, Dumb, Dumbfounded, Dimwit, Diplodocus, Dinosaur, Diana, Dagnasty, Dagnabbit, Diddling, Dawdling, Doodling, Dude Ranch (buzzing noise) Dick, Doofus, Dammit, Darn, Dangle, Drink, Drunk, Dank, Dork, Dusty, Dunce, Distinguished! Development! Duplicitous.

Crank is wearing a black garbage bag over his head, adjusted so his face and white goatee peek through the hole he’s cut in it for air. On either side of the bag are two enormous fish eyes, drawn on card stock, with marker.

I’m here tonight reporting a story about a couple of loosely associated experimental musicians from Boston, a story whose meaning is starting to exceed my grasp.

Brendan: How would you describe Crank Sturgeon?

Crank: In uhh, a sentence?

Brendan: I have no idea. How would you describe the experience of being Crank Sturgeon?

Crank: Well it’s, uh, it’s not a party.

Angela: It is so.

Crank: It is a party. It’s funny because, I’ve survived for awhile, through the many phases of experimental music.

Brendan: What do you mean the many phases?

Crank: The many phases. You’d go to a show in 1996 in a basement in Allston and it was like, a tough guy scene.

Angela: People sitting on the floor, like indian style, and a dude looking at his belly button going “doonk-doonk-doonk.”

Crank: (laughs) Very true…

Angela Sawyer, the owner of Weirdo, jumps in. She and Crank know each other going back to the nineties, when they were at the beginning of the path that has led to the three of us standing in a circle in her record store.

Brendan: what’s the trick to growing old with grace within the experimental community?

Crank: Oh that’s a really fun question, because I’m still figuring it out. I think…did you want to say something?

Angela: Well I feel like no one– when I was twenty, or eighteen, and I met people who were much older than me, it never occurred to me to look at myself from their point of view, ever. So I only ever thought, “oh, that person is as old as my mom and my dad, but they’re doing what I want instead of what my parents are doing. Once you get to be–– I’m in my forties…then is when you’re like, oh, I have been there so many times and they have no idea where I am. So that’s when you start to feel marginalized a little bit

Room 2 (Shane Broderick)

The TV in Shane Broderick’s living room is on mute. A weather man gestures in to a map of New England in shades of blue and purple. At the top of the screen is a red banner with the words “Blizzard Warning.” It’s mid-afternoon. Shane and I are drinking cans of beer that Shane brought out of the fridge.

Shane: I was always playin’ music and stuff since I was a little kid. Even when I was, like, twelve years old I’d be up late smokin’ weed and messing with drum machines and stuff like that.

Brendan: Where’d you get your hands on a drum machine at age twelve.

Shane: Uhh, Christmas present.

Brendan: Christmas present?

Shane: Yeah.

Brendan: That’s pretty cool.

Shane: Yeah, I had my beginner guitar and a drum machine. Y’know once I was like, fifteen and stuff I got a job, started collecting equipment…I thought I’d make a career out of it but I ended up just being, like, a lifelong mailroom guy.

When he was 19 years-old, Shane dropped out of college in Florida and moved back to Massachusetts. He started making abrasive music with a friend he knew while working at a gas station in high school.

Shane: We worked together and every time we finished a shift it would be like a hundred and something dollars under, and I was like, what the fuck this kid man.

They called themselves Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck.

Shane: We joked around on the internet about how we were going to start the most extreme band ever and how the first record we’d just put a bunch of contact mics in a blender and throw a rabbit in it and whatever it sounded like, that was the first LP. Which we never did. [music in]

Brendan: But what instead came out of it was…

Shane: I stuck my boner in a blender. Which was a demo that we did which was me and him coaching eleven of our friends, we were just trying to make circus music with grindcore parts.

Shane: We got reviewed in something like Metal Maniacs, that was like a magazine that when I was ten years old and my mother would drag me to CVS to grab things, I would sit in the aisle and look at, like, pictures of like, Slayer looking sexy and stuff like that, so I was like “oh shit, I’m in this magazine now.” After that, me and him decided to keep the name and go forward with it.

Shane is in his early thirties and he still makes music, although Twodeadsluts hasn’t been active for awhile. He also still plays shows sometimes, though he doesn’t really enjoy it.

Shane: I don’t know I think it’s just, like, nerves. It was easier with the other guys because we were more like a wrecking crew. Y’know, get blind stinkin’ drunk and it didn’t really matter what happened.

Brendan: What would one night at a TDS show end up being like?

Shane: It would start off sloppy and then I wouldn’t remember then end of it.

(Indiscriminate yelling)

Shane: We’re Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck from Boston, and we need the drum machine way fucking louder. Get that shit way the fuck up.

Brendan: When you guys got onstage, there seems to be sort of a pattern. You start off with some harsh feedback, and then it progresses into stuff getting knocked over.

Shane: There was definitely a lot of feedback and definitely a lot of things knocked over.

They were also usually naked.

Shane: I think we were probably more performative over substance, to be quite honest. In those early shows we were just using five or six microphones, a bunch of fx pedals running back into each other, and just whatever sounds were happening, were happening

[music]

Shane: Either people really liked it or found it very entertaining, and on the flipside– we’d have people picket our shows, feminists thinking that we were, like, um, promoting sexism… Just that band name wipes off at least 70% of the population from even giving you a chance. It’s probably a higher percentage than that…

Brendan: So the choice of the band name then, was it to…

Shane: It was kind of like, a filtering mechanism and also it was like an inside joke that just kept going and going, and no one was really in on it but us. The band wasn’t supposed to last ten years either.

Shane: I can’t even give you any rationale behind it…it really might look pretty forced, but it was actually pretty natural for the people involved in the band.

Brendan: Why was it so natural?

Shane: I don’t know. That’s a question for a therapist. I don’t know.

I sip from my can of beer even though it’s empty. Shane plays with the pull tab on his. On the television, the weatherman predicts a foot of snow is going to cover Boston over the next two days. Shane, still dressed in scrubs from the hospital where he works, says,“I got to work tomorrow no matter what.”

There’s a half-open ironing board against a wall. In the bathroom, the sink is plastered with shavings. Next to the un-flushed toilet sits a stack of musical notation paper. I stare at it, because it says something specific about the person I’m speaking to. I can’t figure out what, or why.

Brendan: If you could maybe, like, point me in the right direction of some people in the area to talk to…

Shane: I think you should definitely talk to Ron in Lowell. He runs triple-R records. He’s kind of, America’s greatest living noise artist. Like a godfather type…

Room 3 (RRRon)

I walk out Shane’s front door and into Ray Robinson’s café in downtown Lowell. Ron Lessard waits for me in a yellow booth along the window. Through the rain on the glass, the world outside is a blur of different shades of gray.

Brendan: Where should we begin?

Ron: (chewing noises) So. Today is Wednesday. I’m eating lunch. I’m almost through with my fries, soon I’ll be starting on my burgers. Fuckin’ awesome.

Ron is the noise expert, one of the engines driving America’s experimental music scene since the 80s. Ron has released about 1000 recordings on Triple-R’s in-house label.

Ron: I was the source. And everybody who ever learned how to play a tape backwards or make feedback decided to send me a demo. And man, I heard so much crap like you wouldn’t believe…I mean, how many Rock’n’roll bands are awesome, and how many suck beyond belief?

Ron first got into noise music around 1981, after he left the Air Force and came home to Lowell.

Ron: There was a mail-order outlet out of Colorado called Aeon A-E-O-N. When I got their catalog, I couldn’t believe the stuff they had listed. They had, like, Whitehouse albums, New Blockaders, Maurizio Bianchi, and it’s like who the fuck are these guys? So I started buying that stuff and I was like, woah, this is what I’ve been looking for all these years. The guy that ran it became a survivalist kind of guy, y’know, living out in the woods with his gun type of thing and, actually, he eventually sold me his entire inventory, I bought him out.

Ron: When I first opened I tried to specialize in all the really weird imports, bizarre bands and that kind of stuff, y’know. But at the same time, I knew enough to know that pedestrians, your average everyday person, has no freakin’ clue. They just want to listen to a Barry Manilow or whatever the fuck they like, y’know.

His store, RRRecords, opened in 1984.

Ron: After Aeon, I was the guy that was thoroughly obsessed, and I just devoted myself to it…Day in day out noise, morning, noon, and night. Listening to tapes, checking out bands all day every day. At that time Heavy metal wasn’t heavy enough, punk rock wasn’t extreme enough, Noise did it for me, it really did.

Ron started performing noise music himself under the name Emil Beaulieau. Footage from from the nineties, like this, show him using vinyl records and their accessories as instruments.

This is another way to look at noise music: instead of using something like a trombone, or a tuba, a guitar, or a piano, you take whatever you can find, whatever objects appeal to you, and you refashion them into something expressive. The screeching noise you hear is coming from a modified turntable, which Ron stands behind with a goofy look on his face, pretending to polish record.

Ron: Remember to always, always use the circular motion when cleaning your records.

From that perspective, noise is a positive, creative philosophy, and I can see how people get so obsessed with it.

Ron:A lot of people, y’know, they can’t play guitar, they can’t play the drums–– but twisting knobs and screaming your brains out, getting out that primal scream, whatever it is…it’s inside everybody.

Brendan: And speaking of which, what’s your personal experience with it.

Ron: (Darkly) What do you mean?

Brendan: I mean with Emil Beaulieau.

Ron: Yeah.

Brendan: Well you just said that Noise music was this personal experience. How did you get stuff out through Emil Beaulieau?

Ron: I–I’m not sure where your leading, as far as recording or getting the name out?

Brendan: Why did you start Emil Beaulieau?

Ron: ––you know, I just wasn’t any good at sports (laughter).

The uncomfortable moment sticks in the back of mind for the rest of our interview. Though Ron’s eloquent and energetic, as I was warned he would be, he’s also a little guarded. Maybe that’s because I showed up looking for someone to answer the criticisms of noise music or its culture, which he brushes off with a simple:

Ron: Lately? Lately I’m out of it.

Brendan: When was the last time you were in it?

Ron: Seven years ago (laughs)

Brendan: So let’s go back seven years, because this is something that keeps coming up in interviews with people. Seven years ago, things were very…

Ron: Active.

Brendan: Active.

Ron: Wicked, wicked, wicked active.

Brendan: What’s happened?

Ron: The bands that are making noise today sound like the bands that were making noise ten years ago, that sound like the bands making noise twenty years ago, y’know they sound exactly the same, they’re doing the same freakin’ feedback, they’re still screaming the same lyrics, y’know, it’s just the same thing over and over and over and over again. Which is fine, y’know, punk rock exists for a reason, y’know. The young people, they’re totally into it because it’s new for them. It’s like wow this is freakin awesome these guys are screaming their brains out! They’re talking about killing people! But then ten years later it’s the same thing all over again…I mean do you want to listen to that same band for freaking ten years in a row? I mean do you still want to hear Aerosmith? No you don’t (laughs).

He seems tired in a way that I’ve not seen before. As we talk, I get the sense that what Ron and I are doing has become an exit interview.

Ron: I did what I had to do. I did what I had to do and just to keep doing it because somebody else wants me to? Wrong freakin reason. That’s how bands start to suck. So fuck that y’know.

Y’know there was a time when I couldn’t wait to get on stage and scream my brains out. It’s like, well I mean y’know, you ever had a girlfriend? You make out with her it’s like the best! And then one day, you don’t want to make out with her anymore. It’s no different.

I mean, it’s been seven years. I stopped performing seven years ago, March of ’06. It’s now March ’13. It’s seven freaking years that I’ve stopped. Chances are you’re not doing the same thing you were doing seven years ago. And I’m willing to bet, seven years from now, you’re not going to be doing the exact same thing you’re doing now. People change, they move on. Been there, done that, why do it again?

music: “Fog in the Ravine” | Lejsovka & Freund

The scene dissolves. In the darkness, I think of the question that I wish I’d asked. This isn’t just some thing Ron was doing, it was the thing – what can you do when you lose touch with the something that was core to your identity?

Room 4 (Andrea Pensado)

Andrea: I think it’s very important to not to be scared of being in a place of not knowing. To be in a place of uncertainty, is excellent! Even if it is uncomfortable. Honestly, I don’t want a comfortable life.

I’m sitting in a cozy loft apartment in Salem, while my friend Samira chats with a small, owlish woman in her late 40s named Andrea Pensado.

Andrea: Well if you feel it at twenty than you cannot imagine in your forties.

Samira: I just taste it and I’m like, ‘wow, I’m just feeling all the sugar.’

Andrea: I ate a lot of chips, it was a bad idea. With beer, y’know, not good.

Samira is working on her own documentary about experimental music.

Andrea first got interested in music when she was a little girl, growing up in Buenos Aires.

Andrea: Eh, I was living in an apartment building, and a friend of mine, she started taking piano lessons. She showed me her music and I saw the notation, ehh, and I was fascinated. Honestly I was not aware of such a rich experimental music background until when I was in Poland…

She left Argentina to study composition in Krakow as an adult. But the music she composed on paper was so complex, that she often had trouble finding people to play it. Andrea likes to think about timbre–– the color of sound, what differentiates one instrument from another. To wring out some really interesting timbre with traditional instruments, you’ve got to do some out there stuff.

Andrea: Like, I don’t want to be just writing for the drawer.

And then, Andrea went to the Audio Art Festival, a meeting of the minds held in Krakow every November. The festival focuses on objects used to produce sound: musical instruments, but also computers.

Inspired, Andrea taught herself to program and began using electronics in her work.

Andrea: So I create a wifi for myself just to avoid latency, you can work with any wife…So my controllers are! An iPod–– I say, I look like an apple merchandise stand, which is quite depressing, but you know, what can I do? So this is an iPod with a special application I use to… [iPod click]. Well, first I have to set up the wifi, I show you…

Andrea is wearing a a headset like the kind people use to play video games. She’s sitting at her computer with an iPod Touch in her right hand.

Andrea: This is a simple wave, just a simple low tone. So if I move it like this, I change the pitch. And then if I do like this, the distortion is the direct result of–

She twists and bends her arm manipulating the sine wave into a complex pattern.

Andrea: And I can do the same if I had my voice…

Then she flicks on her mic.

Andrea: Hey, hah, that’s my voice! (noise) hello! Hah! (pause, noise ends). So you know it’s quite dramatic.

Andrea: Maybe for somebody who is not a lot in music, this seems harsh. I don’t think this is harsh at all, this is just the way new music is going. I do believe that, even though I don’t think what we do now is better than what was done in the Renaissance, ok, I do believe that there is constant change, and that artistic languages keep having a need of refreshing themselves, ok?…yeah?

Brendan: (18:49) Why do you think music is shifting in that direction?

Andrea: To explore timbre…Because now, thanks to the technology, we have access to it. It’s easier to manipulate. We are like kids, we are, like, playing. (12:26) I compare it to the beginning of the baroque, where they became aware of chords, of verticality, and then for 300 years, they explore that.

Andrea’s grandiosity reminds me of the document that first inspired me to pursue this project. In 1913, a young painter named Luigi Russolo wrote a letter to a composer he admired. The two of them were part of an Italian movement known as Futurism. Russolo’s letter ended up as one of the movement’s major manifestoes, The Art of Noises.

In The Art of Noises, Russolo laid out a framework for the music of the new industrial world, in which the city itself is both the inspiration and the instrument.

For centuries life went by in silence, at most in muted tones…Amidst this dearth of noises, the first sounds that man drew from a pieced reed or stretched string were regarded with amazement…and the result was music, a fantastic world superimposed on the real one…

We Futurists have deeply loved and enjoyed the harmonies of the great masters. Now, we are satiated and find far more enjoyment in the combination of the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than in rehearsing the “er-O-i-ca” or the “Pastorale”.

We cannot much longer restrain our desire to create finally a new musical reality, with a generous distribution of resonant slaps in the face. Discard violins, pianos, double-basses and plaintive organs…

I am not a musician, I have therefore no acoustical predilections, nor any works to defend. I am a Futurist painter using a much loved art to project my determination to renew everything. And so, bolder than a professional musician could be, unconcerned by my apparent incompetence and convinced that all rights and possibilities open up to daring, I am able to initiate the great renewal of music by means of the Art of Noises.

It is, and I am one to talk, very pretentious. And yet, I kind of sympathize with the guy. When I started making a podcast, I was intent on remaking a whole sector of journalism with my own bold incompetence.

A man of his word, Luigi built these giant boxes called the Intonarumori, whose purpose was to make a bunch of noise. A photo of them often accompanies The Art of Noises, and you can see Russolo standing behind one, this thin guy with a mustache, a hand placed on the crank handle at its back.

Like most manifestoes, The Art of Noises says very little about its writer, except what he wanted to be: a great destroyer come to remake the world in his image. If you’re a certain type of young person, that idea is very attractive, and you can embrace it without really thinking about what other things you might put to the side to achieve that.

Samira: What’s your, I know you’ve done a lot of work with visual, audio and visual.

Andrea: Well that’s with my ex-husband (laughter). Greg, whom I met in Poland, he comes from video, from cinema. We had a duo, eventually, I stopped doing my own to work for our duo, which we worked together for ten years. Greg did the images and I did the sound. And we work on interactivity. Then we split, so now I work just with sound.

Brendan: How is your music different working with your ex-husband, than after?

Andrea: The main goal of our duo was to have real time interaction between images and the sound. So if there was something onstage like a movement or, whatever, it had simultaneously a result in both. It gave some rigidity. So now that the interaction isn’t so important, I have much more freedom to just to improvise. It’s like much, much more freedom.

Room 6 (Angela Sawyer)

Angela: One of the first people I ever met who was interested in experimental music was Ron Lessard.

I’m standing at the counter in Weirdo Records one afternoon, talking with Angela Sawyer again She’s telling me how she first got involved with the experimental scene, just after she started at U-MASS LOWELL in the early 90s.

I had never been to New England at all, I just flew here on a plane from Denver and I wanted to meet some people, and I didn’t really know what to do, and I heard some other kids saying that they wanted to join the college radio station. They said at the meeting to join up, you have to show up and volunteer…I went back the next day, and there no one was there.

Brendan: How long were you there for?

Angela: Probably an hour (laughs). Finally someone came by…I was just like, “hey, hey, I’m here to volunteer, what should I do?” And they just looked at me like I had three heads. They were like, “why don’t you clean something?” So I found a vacuum and I just started vacuuming…

And I went through all the rooms, and finally I got to a room that I hadn’t been in yet, and there was a person in there, and it was kind of dark in there…So I waited for him to notice me. I said hi, I’m trying to vacuum. I had no idea that it was the air studio and, um, Ron, of course, he’s like a firecracker going off. So he’s like, “OH YES COME ON IN,” he was mic-ing the vacuum cleaner, and I’m just like “oh hi,” and he’s like tell me about yourself, who are you? And uhh, he was really awesome to me

As we walk down memory lane, Angela starts talking about a world that I was once very interested in, the network of noise and experimental artists who connected in the early days of the internet, after decades of being little feudal kingdoms.

Angela: There was definitely a feeling at one point of there being a first-world wide, at least, community, if not worldwide, of people who were listening to the same releases, and they were seeing the same bands, they’d heard some Throbbing Gristle records, and they had a common language and finding out about cool stuff and figuring out how it worked, and they knew what happened when you stuck a clarinet underwater and put delay on it.

I’ve been thinking a lot about what Angela said at the Crank Sturgeon show, about choosing to live on the Island of Misfit toys without thinking about it very hard. Because I feel, in a lot of ways, that that’s become my life. I’m more devoted now than ever to completing the work I set out for myself, but I’m also deeply unhappy, and more isolated.

Angela: Every town has the person who is like, I’ll become the nun, I’ll sacrifice myself and do all this work and…y’know, I have a store, that’s what I do.

Brendan: Can you talk a bit about sacrificing–– about becoming a martyr for the scene?

Angela: I’m not trying to do that, I actually really dislike that.

Brendan: How did you fall into the role?

Angela: If you have some job related to underground music, that’s what you’re doing. ‘Cause there’s no money. But that’s one of the only ways you can spend your whole life surrounded by it.

music: “Fog in the Ravine” | Lejsovka and Freund

Angela: Everything I know about politics and geography and sociology and psychology, and how to sort of figure out how to deal with the world at large, I mostly learned them from records. It’s been a very long time since I’ve had a conversation about anything else. I’m a very narrow person outside of records. Basically, records are sort of my defense system and or window for everything, I think of every record as like a pair of of tinted glasses, and you can look at the whole world through that and see it in a new way, and each good record has a slightly different shade on it, so you never get done figuring out how things work and enjoying new wrinkles in how things are. The bad news is that if you take the glasses off things look terrible, then you have to function like a regular person. And that’s not something I’m very good at.

If I’m being honest, neither am I. I’ve agonized over these interviews for a long time, afraid of saying the wrong thing about the people in them. To call it a “cautionary tale of loving something– an idea– that cannot love you back,” sounded unkind, both to them and to myself. I can’t help but feel at the end that that’s exactly what it is.

I avoided revisiting these interviews for almost five years because they held up a mirror to the shaky logic I built ambitions on. They pointed out, in no uncertain terms, that art cannot save me. It can help me find a way to save myself, by learning to communicate things that I feel deeply in a way that’s truthful, accurate, and honest. But that’s all that it can do.

And it took losing someone I loved very much to understand that.

Room 7 (Somerville Ave)

Shane Broderick and I stand on the sidewalk of Somerville Avenue on a cool spring evening. Shane’s arm is in a cast. He’s just finished telling me a story about the time he punched a club owner at a venue up the block. As we’re talking about the reputation that Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck had amongst Boston’s club owners, some of Shane’s friends emerge from the bar where he’s just finished a gig.

Shane: it’s funny because we never actually gave any of the venues our actual performances, it was more like basement parties and shit like that that they were scared of, that they’d heard about.

Brendan: I can’t remember if I got this on tape last time, would you mind describing what the actual performances were?

Shane: Can’t really do that, I don’t know, you can ask these guys.

Friend 1: What’s that?

Friend 2: You gotta lighter? I just realized I left my backpack down there, I got good beer in there but whatever fuck that shit.

Brendan: Would you guys mind describing to me what a normal show by Twodeadsluts Onegoodfuck was like?

Friend 2: Is this an interview? I wasn’t ready for an interview man I can’t do that! My voice cannot be heard on tape.

Friend 1: (makes jerk-off motion) It’s like this.

Friend 2: Can I get a lighter from somebody?

Shane: (shouting) It’s like looking at something, and gettin’ so excited and just BAM! And then it’s kind of like aww fuck.

Friend 1: I don’t have a lighter!

Friend 2: Do you have a lighter?

Shane: We need to go home. Need to hide under a blanket.

Friend 2: Do you have a lighter buddy?

Brendan: Nah, I’m sorry.

Friend 2: Motherfucker! How can you do an interview without a lighter? (distant) Fuck! Amateur!

Brendan: So, just so I don’t take up the rest of your time, there was something you said during the last interview. You said that, for TDS, there was this joke that you guys…when the joke stopped being funny, you guys were like, ‘alright, I’m gonna do something else.’

Friend 1: The joke didn’t stop being funny.

Shane: Well ok I’m not sure the joke ever stopped being funny but…

Brendan: So, what, in your opinion what was the joke?

Friend 1: The band was the joke.

Brendan: What specifically about the band was the joke?

Friend 1: I don’t know…

Friend 2: (strike lamppost) Do a funny voice c’mon what the fuck! We’re supposed to be entertained by this shit.

Shane: Alright, you can cut my voice here.

Friend 2: It doesn’t matter what you say so long as it’s in a funny voice it’s cool.

Shane: There are a lot of Boston noise bands and people from Jamaica Plain and Allston and they want everyone to be like, onboard with, ‘hey, we’re all friends, this is a scene! come down to our house play a show blah blah blah.’ And what Twodeadsluts was more like, was just like, ‘We’re not even invited. We’re playing a show, we’re trashing your fuckin’ house.’

Brendan: Do you ever miss it?

Shane: Yeah, of course I do. It is what it is.

Brendan: I feel like that’s a pretty good place to end.

Shane: There you go.

I walk off into the night. A block away, I come to a stop on a concrete island in the middle of Somerville Avenue and look back at Shane and his friends. They were still down by the bench we were sitting on, drunk, being loud, but their noise is drowned out by the cars flying past me, headed for the outskirts of Boston.

Standing here, it occurs to me that need room tone, the sound of the place I’m in. Room tone helps smooth out transitions in editing, makes a radio documentary sound more natural. I’ve forgotten to get it for almost every other interview with the noise artists. But that I remember now seems significant to me, an promise to myself that someday I’ll figure what made this experience worth telling.

Credits

Today’s episode was produced with help from Wes Boudreau and Samira Winter. Editing help by Kyna Doles and Jon Davies. Special thanks today to Lejsovka & Freund, Jacob Rosati, Sean Coleman, Elissa Freeden, Brittany Rizzo, Tyler Carmody, and Birgit from Denmark.

Visit our website, investigating regional scenes dot org, for more episodes and, this summer, some bonus materials. You can find Stories About Music on your local podcast provider. Please leave a review to helps us find new listeners.

From Philadelphia, I’m Brendan Mattox, back soon with more stories about music.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

story about music #7

Season one concludes with a story about Taraka Larson, her band Prince Rama, and her first manifesto, The Now Age.

music

04:12 “Bahia” | Xtreme Now

05:35 “Breaking the Kitsch Barrier” | Architecture of Utopia

08:41 “Those Who Live for Love” | Top Ten Hits for the End of the World

12:36 “Rest in Peace” | Trust Now

15:46 “Portaling” | Trust Now

24:20 “Your Life in the End” | Xtreme Now

or listen to it as a single playlist here.

links

The Now Age manifesto

Prince Rama and Taraka’s new manifesto.

Thank you to Kyna Doles for being our editor. Kyna currently reports on the New York real estate market.

transcript

Intro

Brendan: Ok, so, before we get started, who are you, and what do you do?

Taraka: (pause) Who are you and what do you do?

Brendan: No one’s ever done that to me before.

April 10, 2015

I’m once again sitting in the side chapel of the First Unitarian Church two weeks after I recorded my interviews with a Winged Victory for the Sullen, and about fifteen minutes after Prince Rama just brought the house down in the church basement.

Brendan: I’m Brendan, and I’m a journalist––well, kind of.

Taraka: So, I’m actually trying to practice not being anything, and not doing anything. So I almost feel like this is a trick question you just asked me that

Since she never actually said it and I’m feeling kind of crunched for time, I’m talking to Taraka Larsen of the band Prince Rama.

Taraka: It’s like an ego removal, but also like, a time removal. I feel like time mostly exists when you are doing something because all of the sudden, you don’t ever have enough time to complete the task or you’re always fifteen minutes late, or whatever. If you can get rid of the doing aspect, it’s just like you’re, you’re just here, and there’s always plenty of time, it’s just floating all around.

You’re listening to Stories About Music, a podcast on the subjects of music, journalism, and memoir, and how the line between those three things is often not as clear as I’d hoped.

music: “Bahia” | Extreme Now

My name is Brendan Mattox, and this is story about music number seven, “Ouroboros.”

The Now Age Manifesto

Brendan: So you have this, like, very complex manifesto of sorts online.

Taraka: Is it complex?

Brendan: Well, I feel like I finally understand it and I think this is the third time I’ve read it.

Taraka: Cool––wow! Thanks for reading it three times! That’s great.

During my last few months in Boston, in 2013, I found the website now dash age dot org. The site carries the subtitle “meditations on sound and the architecture of utopia,” and what follows are few pages of homemade diagrams, thoughts on music and eternity, and kitschy internet gifs.

Taraka: Well it’s kind of a funny story. I was born and raised Hare Krishna and…When were first kind of starting the band, I was really deeply into it. I mean to the point where like, I was out living on an Ashram in––actually in Pennsylvania, and I just––I had this like realization when I was there that I couldn’t be a monk.

music: “Breaking The Kitsch Barrier” | The Architecture of Utopia

Taraka: It just didn’t feel honest––it felt very like, this was how I was raised, even though I really connect so deeply with, the music especially, of the Hare Krishna movement and stuff. I just felt really, like, constricted in this organized religion. The world is so disorganized. When you try to organize it it doesn’t make any sense any more, there’s all these contradictions.

The Now Age website, of course, belongs to Taraka, and they mark the end of what could be called the first phase of Prince Rama.

Taraka: This guy actually, he gave me this keyboard, he was like, “you should play this,”…And I wrote the first Prince Rama song and…I just had this intense realization, I was like…there’s other ways of being a monk. You don’t have to be in an Ashram and washing dishes and gardening.

When it began Prince Rama consisted of Taraka, her sister Nimai, and her boyfriend Michael, whom she’d met as a teenager while near Gainesville Florida. Not long after three recorded their first album, The Architecture of Utopia, and hit the road.

Taraka: I remember I was in Paris, we were, like, on tour, and I’m just like, “What––what do I believe, right now?”

And then, in the midst of a tour in 2010, Michael and Taraka split up.

Taraka: I think we had been on tour for like, 80 days straight or something crazy and I wasn’t feeling connected with this religion. And I kind of had dug myself in a hole here, I named my band Prince Rama…So I just started writing out everything I don’t believe, and all of the sudden this thing started forming.

Brendan: Did all come out in just one piece like that?

Taraka: Yeah, pretty much, I mean, I did some google image search for the pictures later. It’s not like, y’know, anything just happens spontaneously, it’s like you’re obviously chipping away at this ice block for a long time, and like you read something and that gives you another little chip and then you read this other thing and then all of the sudden you’ve got this ice sculpture and you’re like––I didn’t even realize that!

This was the first draft of the Now Age manifesto, born out of a period where the group was living on the road, functionally homeless by their own account. It wasn’t all bad––at SXSW that year they impressed Avey Tare of Animal Collective, who gave them their first label contract.

The trio recorded their first record for Paw Tracks, Shadow Temple, in their new home of Brooklyn, New York. Then Michael went on a hiatus that became permanent. Prince Rama is now a duo of Taraka and Nimai.

music: “Those Who Live for Love for Love” | Top 10 Hits of the End of the World

Taraka was an art student at the MFA school in Boston. Her time there, especially the year or so she apprenticed with painter Paul Laffoley. Some his terms and ideas influenced the Now Age Manifesto, which launched in 2011 with a series of happenings in New York City.

Taraka: We were doing this residency for Issue Project Room where we needed to form this fake cult. The Now Age kind of sprung out of that because any cult needs a manifesto, and so, we’re the Now Age cult, and this is our manifesto! We really ran with it, we were handing out pamphlets on the subway and, yknow, really creating each of the shows to be like this sort of bordering the line between cult ritual practice and musical experience.

In practice, this meant stuff like a fifteen minute exercise routine that doubled as an exorcism, which the sisters performed for eight hours straight.

Taraka: We were exploring utopia through music and looking at the concert space as utopian architecture. It’s like this temporary autonomous zone that has its own kind of government.

All of these ideas figure heavily into the Now Age manifesto, which grew out of an attempt by Taraka to square the music she was making with the reason made it in the first place.

Taraka: This was in 2011 so on 11/11/11, we like, staged this apocalypse. I feel like utopia and the apocalypse, y’know, the end of the world and beginning of the world, it’s all in this space. I feel like the end of the world would be like a karaoke bar.

music: “Those who Live for Love Will Live Forever”

Taraka: I looked through some billboard charts at various times the world has ended…all these different apocalyptic dates the world was supposed to end. I looked to see what was the billboard number one hit single, and then we made this, like, karaoke book of all these pop songs. And we slowed them waaaaay down I mean so slow. People were like “Oh, I’ll do Alicia Keys!” and then they were up there for like, fifteen minutes.

music: “Those who Live for Love Will Live Forever”

Taraka: Karaoke is…I feel like that is the closest to witnessing zombies that I’ve ever come. It’s like if you’re really good at it and you’re really feeling it, you’re like, channeling Elvis. You’re willingly opening yourself up to being possessed.

Krishna Consciousness

Possession, Zombies, Elvis––these things are like symbols for the ideas that fuel Prince Rama, a combination of outsider art, critical theory, and pop culture.

Of course, Taraka and Nimai also draw from their upbringing in the Krishnas. Like other ex-religious kids, Taraka still sees mysticism in the world, even though it takes its form in ways that our ancestors might not have understood it.

The Now Age Manifesto is built on an idea that I was quite keen on for a long time, that a concert is its own form of worship, part of the long tradition of ecstatic religious experiences.

Taraka: In Krishna culture its like, all call and response kirtans. There’s never really like this performer-audience boundary. It’s like, someone’s saying their prayers, you’re responding, and then it kind of works itself up and then this third voice comes in, and that’s what you really want to go for. ‘Cause that, that’s the space voice. I feel like I try to create a space where I can experience that and other people can experience that too. That’s all you can do––you can do what you can with love and hopefully that space will resonate and respond, and yeah that third voice can come in.

Brendan: There’s like this intense spiritual element to what you’re doing, um, how does that interact with the financial realities of being a musician living in Brooklyn in 2015?

Taraka: Well it’s pretty simple really. We make a six-digit salary a year, but all of the digits are zeros.

(laughter)

music: “Rest in Peace” | Trust Now

Taraka: I mean the thing is, it’s like being a monk because you’re a beggar when you’re on stage.

Taraka and Nimai have spent the last several years traveling, like pilgrims, from one art project to the next. They put such an emphasis on crafting a live experience partially because that’s widely accepted as the last way to make money as a musician.

Taraka: To this day we haven’t really ever made a profit. So it keeps us humble. Even those we’ve always been, like, pretty broke, we’ve never been, like, bottomlined. We’ve always been take care of. We always have exactly however much we need.

Brendan: How does that happen?

Taraka: That’s where the spiritual comes in.

And so the manifesto itself is like a religious text, a guide by which to remind herself of why she’s doing it. Going into this, I wanted to find out where Taraka’s genuine beliefs ended and Prince Rama’s Taraka’s aesthetics began for one particular reason.

The Now Age manifesto takes visual cues from the weirder, unhinged corner of the internet––the kind of websites that explains that the earth is really flat or that time is divided into four equal quadrants.

The manifesto reminds me of those websites because I read a lot of those websites in 2012, after the end of my second blue period. In recovery, the anxiety that I had about “the end of things” manifested itself in trying to figure out why people so obsessed with apocalypse that year.

I was aggressively protective of my hope that the future could be stable, a belief those theories––the mayan calendar, peak oil, political revolution––all seemed to criticize.

Taraka: I think that apocalypses are extremely healthy for culture to have. But it’s like a fantasy, y’know? Like, I think it’s healthy in the sense that you bring yourself to this emotional place where you’re ready to let go of everything and start new. But it’s like a fantasy.

I first read Taraka’s manifesto a year later, just after I graduated.

Brendan: I think I discovered it around the time that I was, like, aware of what you talk about as Ghost Modernism in it.

Taraka: Oh, yeah.

Ghost Modernism––a pun off the art movement, post-modernism––is an idea that I was quite keen on during that period. Essentially, Taraka proposed, culture has become an Ouroboros, a snake eating its own tail.

Taraka: The thing with zombie aesthetics and ghost modernism is like, the past is eating the present, consuming it like flesh, y’know?…

Brendan: Was there anything that you were noticing happening that happening that caused you to jot that idea down?

Taraka: Yeah, I just feel like every band is a pun off of something that happened decades ago. Everything is just a parody, every band is just a pun off of something that happened decades ago, a way cooler band or a way cooler actor or whatever. I just feel like that originality is just being degraded and degraded.

Brendan: Did that make you angry, at first, when you saw that?

Taraka: I’m not critical of it, necessarily. It doesn’t make me angry but I’ve noticed it. Like, well…that’s not where I’m at, but, it’s interesting that’s where other people are at, and what does this mean. ’Cause I feel like being angry about it, it’s not that productive. It’s annoying, maybe, but like…I don’t have to listen to those bands.

But I did. Well, I didn’t. But I did force myself to as part of the hoops I jumped through to maintain my identity as a certain kind of person.

Up until 2013, I had just assumed that I was bound for Brooklyn, to become a writer and join up with the cultural force that is New York City. But when the time came to take the plunge, I couldn’t do it.

Instead I spent that summer wandering around Boston trying to figure out what was me. I barely looked for jobs. I decided, maybe too quickly, that I really should move back to Pennsylvania and figure out just what it was I wanted to make, so that when I made it, it would be absolutely, 100% me.

music: “Portaling” | Trust Now

My guide for all of this was, in some way, Taraka’s manifesto. The Now Age was her attempt to make some sense of her own identity even as the things that had composed it for so long were coming apart.

Taraka: Once you’re in that place of having an identity crisis it just kind of happens. It’s like, you can’t harmonize with fear, fear is like this dissonant tone that comes in, I don’t even think it’s produced from this world. So it’s like trying to find that other more natural note that’s like…know what I mean?

The Grand Finale

I kind of do. The blue periods, I’ve realized after all this, are long, sustained identity crises. They happen when I realize that time has passed and the I am not the person I hoped I would be.

I feel like it used to be so much easier to know who I was, or at least what made me special. When I was a teenager, coming to shows at the First Unitarian, it was this music that I loved. When I was in college, surrounded by TV journalists who wanted to host the nightly news, it was the radio documentaries I wanted to create.

But I’ve never felt at home amongst the communities that surround these things. In fact, I’ve pitted myself against them, trying to defend my own sense of authenticity.

Taraka: When we went to the UK for the first time, everyone was like, “you’re like Kate Bush.” And I’m like, who’s Kate Bush? I was like mad, I’m not gonna look into her and then I actually like really loved her. But y’know it’s weird, people just like, read references into things. And you feel like your constantly referencing. I mean people were referencing people in the past, it’s like, the Rolling Stones loved blues. They started out as a Blues cover band! Those people were referencing people in the past, too. But because there wasn’t this like––you have to go and travel to go see that person, so you’re having this spiritual experience when you’re seeing them, and then you take that inner experience with you! And so when you’re inspired by that, you’re inspired in a way more honest way. The manifestation is a more honest thing, because it was like this thing that you couldn’t really capture…it was like a moment in time and you can’t replay it. There’s nothing necessarily original. But originality stems from the idea that, like, your in touch with your origin, y’know? If you’re doing this from an honest place, you’re in touch with your origin, and so your original.

Moving home has given me a better sense of myself, and my, I guess people call it “aesthetics.” I always thought that word was synonymous with “vibe” until I was stuck on this story and decided to go to the gym one morning. In the midst of doing a pec fly I had an sudden epiphany that true aesthetics are something like a muscle stretch, deep and subtle, to the point where you can no longer figure out where the work ends and the artist begins.

I think that sums up a lot of music that I love, and especially the people who I interviewed during the course of the first season of Stories About Music. Part of reaching that honest place requires laboring for years, usually in obscurity, with the intention of making something true, and not empty. The competing desire to be known for what you do, or even just to survive making art––it can mess with your sense of self.

I certainly can’t claim to have been an unbiased journalist for much of this season. I’ve looked up to and admired so many of my subjects from a distance. But with Taraka, I feel like I’m looking in a mirror. Our career trajectories started around the same time, and while Prince Rama is massively more popular than I am at the moment, we’re both struggling to capture that small slice of attention that people have left for music. Me, in the town I grew up in, and her, out on the road.

Taraka: You’re pretty much just in this weird other time. You’re coming up to a venue after driving like thirteen hours and your like oh my god, load all the stuff in, they’re like, “you’re late for soundcheck!” and you’re like “i knoww sorry!” And then there’s just some chick in the place across the street getting, like, highlights done in her hair. And this is just so bizarre to me. There’s people just having a day. There’s some old dude eating a sandwich, waiting for the bus. Like, we’re just in such a different zone right now.

Brendan: Is it hard having to put all your energy into forty-five minutes a day?

Taraka: Playing the show is great! I don’t have any problems with that, it’s like the rest of the day. Everything leading up to is hard. I’m like a very outward person, it’s like, we’re in a new city! Let’s go on an adventure! I’ve had to be like, ‘Nope, Taraka. If you want to do this tour, you have to not do anything.’ Which brings us back to the beginning.

Which brings us back to beginning. Can you separate the art from the artist, for her own good?

Taraka: Your brain is constantly thinking of things to do, and then when you’re not doing anything it’s like ‘Why aren’t you doing anything?’ And I feel like I’m at this weird place right now where I feel like part of my sickness is that I was trying to do too much. I have to switch something up about my life, what should I do right now? Maybe I should go back and read the Now Age manifesto.

There are people to which things come with great facility, and the art they produce is the noise that gets made as their life is lived. Then there are the rest of us, the people for whom art is an impulse based half in the noble pursuit of understanding ourselves, and half in pursuit of the things you’re not supposed to make art for: fame, money, influence.

I tell myself that my worry is that I’ll never reconcile those things, but really, I worry that I won’t resolve it before my “chance” to succeed disappears. I have always seen time as my enemy, and yet time allowed me to find meaning in music.

At the end of our interview, I was probing Taraka’s belief trying to understand just what the Krishnas are all about, when she hit on this summary that I think explains what it is the two of us are reaching for, even when we get lost in the details.

Taraka: This is obviously, volumes and volumes of books, but in a nutshell, time originates from Vishnu, who’s just lying on this––somewhere in outer space, on an ocean of milk, on this bed of serpents. And he’s just sleeping very peacefully, and he’s just breathing in and breathing out. And when he breathes in, all the universes contract and go back into him, into his pores. And then we he breathes out, the universes just expand. That’s the relativity of time. Just for him, one inhalation and exhalation is, like, our eternity. But he’s just breathing in and out. He’s not going to stop breathing because he always is. He was never born, he’s not going to die. So we’re always just dipping in and out eternity.

If this is the noise I made while my life was lived, then so be it. At least for now I don’t feel like I’m chasing my tail anymore.

music: “Your Life in the End” | Xtreme Now

Credits

Brendan: Taraka Larsen, lives in Brooklyn. Prince Rama’s latest record is Xtreme Now, out on Carpark Records. A new manifesto under the same name is due out in October from Perfect Wave.

Today’s episode was produced by myself and edited by Kyna Doles, who sounds a little bit like this:

Kyna:You’ve been listening to Stories About Music. All songs in today’s episode were written by Prince Rama, with the exception of “Return to Emptiness” by Lejsokva and Freund. A list of those songs, in order of appearance, can be found at our website “investigating regional scenes dot org,” where you can find this, and other stories about music. If you haven’t already, please follow us on your local podcast provider.

Stories About Music is an independent production, but that could change in the future. If you or a loved one are involved with public media or podcasting companies––or if you have your own story about music––please get in touch via info [at] investigatingregionalscenes [dot] org.

Thank you to Kyna, to Taraka and Nimai, to Michaela, and to you for your patience.

I’m Brendan Mattox, back soon with more stories about music.

#prince rama#the now age#taraka larson#nimai larson#radio documentary#music journalism#stories about music#podcast

1 note

·

View note

Link

story about music #6

A story about love, music, Europe, and memory, sparked by a Winged Victory for the Sullen concert last March.

(above: the town of Well. below: Michaela, 2011; the Emerson College European Center a.k.a. “The Castle”)

music

00:00 | “Candy Shoppe” by Emeralds from Does It Look Like I’m Here?

03:14 | “All You Are Going to Want to Do Is Get Back There” by The Caretaker from An Empty Bliss Beyond This World

05:16 | “Atomos I” by A Winged Victory for the Sullen from Atomos

06:33 “We Played Some Open Chords and Rejoiced” from A Winged Victory for the Sullen

11:36 | “Atomos VI” from Atomos

13:13 | “Atomos I” (recorded live)

14:23 “Libet’s Delay” by the Caretaker from An Empty Bliss Beyond This World

16:24 | “I feel as if I might be vanishing” from An Empty Bliss Beyond This World

18:32 | “Strelka Update” by Trouble Books & Mark McGuire from Trouble Books & Mark McGuire

21:41 | “Steep Hills of Vicodin Tears” from A Winged Victory for the Sullen

26:46 | “Atomos V” from Atomos

30:00 | “All Flowers” by Trouble Books from Love At Dusk

links

A Winged Victory for the Sullen

The Caretaker (Leyland Kirby)

Emeralds

Trouble Books

transcript

music: “Candy Shoppe” | Does It Look Like I’m Here?

You’re listening to Stories About Music, a podcast on the subjects of music, journalism, and memoir, and how the line between those three things is often not as clear as I’d hoped. I’m Brendan Mattox

I avoid listening to some music out of fear that I’ll lose the memories I associate with it. Like this one, “Candy Shoppe” by Emeralds. It reminds me of the time I listened to it most, when I spent a few months living in a castle in a small Dutch town by the German border.

I had a job chauffeuring professors to and from a nearby train station. “Candy Shoppe” reminds me of the countryside out there: the tree-lined highway through golden fields of dry grass, the sun on the water as the car rose over the river Maas. I was busy falling in love again, and as the cutoff filter descends, I remember just what that felt like.

This is story about music number six, “To Dream of Another Continent.”

music: “All You Are Going to Want to Do…” | An Empty Bliss Beyond This World

March 26, 2015: I’m sitting in the empty sanctuary of the First Unitarian Church. It’s a large room, made more cavernous by the haunted ballroom music playing through the P-A system.

A few feet away, four members of the R5 productions concert staff ignored me as they ate Chinese food. I’m used to this by now. My interview forgot about me, it only made sense for everyone else to do so.

I’ve been coming to shows here since I was 16, going on 17. I’ve been in every room in the old stone building, sat in its pews, slipped on its basement floor, stared up at its high ceiling in the darkness. I am now twenty-four.

And yet, I’m not bothered by that tonight. It’s a whispery evening in late March, cool air blowing in through the open doors. The sound guy is playing An Empty Bliss Beyond This World, an album by Leyland Kirby under the name “The Caretaker.” It’s a bunch of old 78s, looped and filtered to increase the pops and clicks, the signs of age. It’s an album about the way memory degrades, the way time slips out from underneath of us. I recognized it the second I set foot in the church.

I’d like to stay here forever in this moment, but I have a place to be and a job to do. Soon my girlfriend Michaela will be here, and then I have to make sure she can get in.

Through a doorway, I saw Dustin O’Halloran in the vestibule. Before the staff could say anything, I power-walked backstage.

Brendan: Peeling back layers of paint, I guess, do you think about the work that way? Do you see it like a painting?

Dustin: Yeah, I think. Adam and I are never really...

(noise, talking)

Dustin: Uhm, they’re about to show up.

(door opens)

Dustin: Hey! We forgot about the interview!

Adam: Lucky me, I got tacos instead.

Dustin is forty-three, and the voice in the background belongs to his friend, Adam Wiltzie, forty-five.

Together, they make music as A Winged Victory for the Sullen.

music: “Atomos I” | Atomos

Unless you’re into neoclassical or ambient music, you probably don’t know Dustin’s name, but you do know his work if you’ve ever watched Transparent or Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette. He composed the original score for both, as well as a number of indie dramas.

He met Adam in two-thousand-and-seven, when a mutual friend introduced them at a concert Adam was playing in Bologna.

Dustin: And we ended up, sort of, bonding backstage over our illegal European status.

Dustin had moved to Italy in 2000, around the same time that Adam moved to Brussels.

Dustin:…the dream, the ex-pat dream– most people make it a year and then they go back home. I persevered. Adam and I have both been living out of the country for about thirteen years. I actually don’t meet a lot of Americans who have stuck it out, to where you really feel like you’re at home there.

And just to be clear––this was part of the reason why I arranged to interview a Winged Victory: to figure out how these two guys have managed to pull off something that I would very much like to do.

Dustin: Both of us lived under the radar for a while, and then we both got married and got visas, finally.

Brendan: So it was like, uh, so you had, like, a couple years where you were, not outlaws, y’know, but illegal immigrants.

Dustin: Yeah, we were, when you see a cop behind you, you started sweating a little bit.

Brendan: So how did you say that you resolved that? You guys got married?

Dustin: Yeah.

Brendan: I mean, obviously not to each other.

Dustin: Yeah, no, that would’ve done no good.

music: “We Played Some Open Chords” | A Winged Victory for the Sullen

Dustin was starting to pick up more film work and so he moved to Berlin shortly after he met Adam.

Dustin: I was living in a small town outside of Bologna, and it’s a pretty small place. It was really beautiful and idyllic. I had a studio in an old farmhouse, and, sort of living this really classic, Italian situation that people, sort of, dream of...but what I found was, for me, I just found that missed the ability to collaborate or have people come through––I started to feel very isolated.

They spent the next few years recording together between Berlin, Brussels, and Northern Italy.

Their self-titled record A Winged Victory for the Sullen dropped in September of 2011, just as I was returning to Boston for my junior year of college. It moves at the pace of a sleeper’s chest, rising and falling slowly. Ever since I was 18 I’ve had trouble falling asleep without music, and I ended up listening to A Winged Victory for the Sullen a lot at night, just trying to drift off…

I can’t remember if I latched onto A Winged Victory so heavily because I knew Dustin and Adam lived in Europe, or because it reminded me of the spring I’d just spent living there.

Brendan: Does it feel like A Winged Victory would’ve done quite as well as its done here in America, or do you feel like it’s something that Europe really helped blossom?

Dustin: Definitely Europe. We’ve had a lot more opportunities to play…Musically, y’know, we probably could’ve––well I don’t know if we could’ve written the same music. The states are––it’s marginal. There’s the coasts, there’s different places we can play. We’re not a rock band. There’s just pockets of places that really we can go. But the tour has been really good…

Tonight, A Winged Victory for the Sullen and is on on tour with a few string musicians from Brussels to promote the release of their second album, Atomos. The music was commissioned by a British choreographer named Wayne MacGregor, for a dance piece in 2013.

Dustin: He sent us a lot of weird old science videos…beautiful photographs of shapes changing to spectral lights and there was like a small inspiration from an 80s sci-fi film… The big concept is how atoms inside the body relate to atoms in space, and this interconnection to humanity and the cosmos and it…Brendan: That’s huge.

Dustin: Yeah, it’s kind of, it’s a heady project

Brendan: I mean you and Adam in your individual projects already make, like, music that goes for big feelings in a way, but did this feel like it was bigger?

Dustin: No, I think that’s why he asked us to do it, because he listened to our first record and he felt that. Especially the first record, there’s a lot of human elements to it, but it’s also a lot of getting away from just individual feelings, if that makes sense?

It didn’t.

Dustin: At least for me and what I feel, I don’t feel that it’s–– people will feel alone in the music?

music: “Atomos VI” | Atomos

Dustin: It’s not going for the heartstrings or anything, to me. This is probably the most horrible reference I can make right now, but if the plane was going down, and you suddenly felt at peace…and that duality. Or maybe another feeling is the passing of time… and the passing of time is, when you’re in the moment, a really wonderful moment, there’s also the duality of a feeling that that moment is also now gone, because you’re living it.

Brendan: That–the Japanese mono no aware thing.

Adam: Excuse me…

And it was right here that Adam broke in to ask Dustin a question about something.

Dustin: You wanna just tie it up?

Brendan: Yeah, let’s tie it up.

Dustin: That was a good conversation. I thought that was solid.

nat | Violin warm ups

Back in the sanctuary, the concert was getting ready to start. I found Michaela waiting for me in a row of pews off to one side. The wet evening breeze was still wafting in, so she kept her jacket on.

The lights dimmed and A Winged Victory for the Sullen took their place at the front of the First Unitarian. Their concerts are subdued affairs, the only illumination emanating from from a stand lamp in the center of their equipment. It turned the shadows of the rafters into spider legs, like a giant arachnid watching from behind the altar.

As the music deepened, I closed my eyes and felt time slip backwards

music: “Libet’s Delay” | An Empty Bliss Beyond this World

Brendan: When did we meet?

Michaela: Uhhh…we met four years ago studying abroad in the Netherlands

Brendan: But how did we meet?

Michaela: (exasperated laugh) How did we meet. We met at a bar, um, and we were listening to Kanye West and dancing in the local bar and I think, did I come up to you?

Brendan: I think you came up to me.

Michaela: I guess I picked you out because I’d seen you a couple days earlier hanging around the castle, so I asked if you had––if you listened to Sufjan Stevens. I suggested we go back to your dorm and listen to that instead of what we were listening to at the bar.

Brendan: You’re such a floozie

Michaela: (laughter) I guess, yeah.

This is Michaela, and to just save face right now, she is not a floozie. I was just very nervous about turning the mic on her.

We met while studying abroad in the spring of our sophomore year, at the Emerson College European Center, a fourteenth century castle in the Dutch countryside.

Michaela: I rented a bike, I don’t think you did. Yeah, biked around, and I got to see the fields and the farms. As you first come into town, there’s a bunch of little baby goats that will run up to you and bleat.

I grew up in the near suburbs of Philadelphia. The town of Well was and still is the most remote place I have ever lived. Life there moved at this unhurried pace that was so pleasant.

I thought Europe, as a whole, was a pretty wonderful place, and I often wish I could go back, something Michaela knows very well.

Michaela: Well I thought you might have some questions about your plans with Europe and then I could follow up on that.

Brendan: What are my plans with Europe?

Michaela: Your plans with Europe. It seems like you would really like to start a writer’s colony and get some friends together, get some people to write and, like, maybe put together a literary magazine or, like, compilation of things. So that’s your grand scheme.

Brendan: And what do you think of my grand scheme?

Michaela: It’s a little stressful to think about but it’s definitely a nice idea.

It’s a nice idea that I cling to pretty heavily, because I connected with a happier part of myself while I was in Europe. I’ve always felt like an outsider no matter where I’ve been; and while I was there, that was actually very true on a basic level––meaning I was able to find the things that made me belong much more easily.

As our short semester drew to a close I started to realize that there were places here where I might never walk again. I started creating mental maps, trying to remember every single detail about my time in Europe: every afternoon, every trip to the train station, every meal, and for the rest of the year, I gravitated towards music that reminded me of those things, like Emeralds, or A Winged Victory, or the Caretaker’s An Empty Bliss Beyond This World.

I was hoping to save some that warmth for myself…but only found myself progressively more miserable as the weather got colder and my friends started to drift apart.

music: “I feel as if I might be vanishing” | An Empty Bliss Beyond this World

This was the beginning of the second blue period.

It’s hard, even now, to describe what happened, but I feel like I’ve been living with it ever since.

I came out of high school eager to prove that he was better than everyone else by create some kind of grand powerful work and achieve success at a young age. Suddenly, I realized that the clock for being the first to succeed was starting to run down, and I had no idea what I was going to do.

And with this experience of a place where I’d felt more at home than ever before in the rearview, I suddenly saw my life stretching out before me: so vast, so many paths, none of which necessarily led back to the happy place I had been.

Finally, in what I can only describe as a concerted effort to hit the lowest point possible, I broke up with Michaela right as autumn turned to winter.

I want to explain that this kind of music I’ve been playing all episode, I didn’t listen to it until the blue periods came into my life. These albums provide a place to hide, a womb I can augment by pulling a blanket over my head, a place where I can dive deep into my memories as I drift off to sleep. I used to go to bed listening to whatever. Sometimes music that it’s kind of insane to imagine falling asleep to now. But as time went on, the practice became so utilitarian that I limited myself to quiet, ambient records.

Until one night, I really couldn’t sleep. I tried listening to a Winged Victory for the Sullen, I tried the Caretaker, I tried Emeralds. But nothing of it sounded right. Every time my head hit the pillow, I just lay there, thoughts racing, sadness building.

music: “Strelka Update” | The Trouble Books & Mark McGuire

Music has a mystical quality to me: it hides in plain sight only to emerge at the moment I need it most. That night I stumbled across a record I’d downloaded several weeks earlier, a collaboration the guitarist of Emeralds had recorded with an unknown band from Ohio called Trouble Books. And as I lay there, soaking it in I recognized the loneliness in the singer’s voice. It sounded like mine.

That night I found you out in the street, tearing through the trash near St. Basil’s Cathedral , your fur was filled with old coffee grounds. Half frozen in the five p.m. twilight…Oh Strelka, I made a huge mistake. I let those men send you up into space. The only place colder than the motherland…

Listening to Trouble Books, I realized I had cast Michaela off into space, and along with her, an optimistic part of me that I wanted to hold onto. And with that revelation, I finally passed out.

Oh Strelka I love the way. You push your face up against mine and how we both passionately hate...smoke alarms and cheap electronics.

Not long after, I reached out and pulled her back. And in the process, all that wordless music that I’d put so much of my energy in slipped from my rotation.

With all due to respect to Dustin’s intention that people feel interconnected when they listen to A Winged Victory for the Sullen, the way that I used it left me feeling very lonely. I trapped myself in my memories, building up a pressure of anxiety and sadness that I told myself I could use it to make something, only to never find the release valve.

And yet, music is plastic. My associations with it can change.

music: “Steep Hills of Vicodin Tears” | A Winged Victory for the Sullen

The room was warmer now. Everyone sat with their heads bowed while outside, the shadows of the tree branches danced across the stained glass. I put my arm around Michaela’s waist and gave her a squeeze.

Michaela’s been the closest person to me over a period where I’ve struggled between holding onto some romanticism and feeling crushed under the weight of my own ambition and lack of success.

While I was in Europe was I able to shut up this part of me that either lives too far in the future or too far in the past, chronically trying to rob myself of the joy of what’s in right front of me.

I was able to tap back into that after college by living here at home and giving myself over entirely to making art. But now, I’m starting to worry that, just like five years ago, the weight of what I want and what I have will never balance out. In trying to make something that captures these moments, I get lost in the process.

I keep hoping for some assurance that being able to create is enough, that making something that’ll outlast me will help me survive, and yet––what had I learned from all the people I’d spoken to that winter? Art resonates, but it does not guarantee food in the stomach or adequate vision care.

When I dream of another continent, I dream of a place and time outside of this one, surrounded by people I love, where I have figured out this adulthood thing to the point where it no longer feels frightening, where I can feel as unconcerned as I used to.

These were just some of the things I thought about during the show that night. And then they passed, and I was left with the moment, with my hand on Michaela’s side, and the warmth of the church.

Until that too ended. I sent Michaela back to the AirBnB. I had one last piece of business to take care of.

Brendan: I actually wanted to start with, why did you move to Europe?

Adam: Better quality of life...taxes, healthcare, language...cultural significance, feeling detached, looking for a new life, lookin for something more than we were given here, as American citizens.