Text

A scandal of senators stand over the battered corpse of the Roman republic

Sulla: So. Who broke it? I’m not mad. I just want to know.

Lepidus: I did. I broke it…

Sulla: No. No, you didn’t. Clodius?

Clodius: Don’t look at me. Look at Crassus.

Crassus: What?! I didn’t break it.

Clodius: Huh. That’s weird. How did you even know it was broken?

Crassus: Because it’s sitting right in front of us and it’s broken!

Clodius: Suspicious.

Crassus: No, it’s not!

Pompey: If it matters, probably not…Caesar was the last one to march on Rome.

Caesar: Liar! I sent you four peace offers you rejected!

Pompey: Oh really? Then what was your army doing by the Rubicon earlier?

Caesar: I needed a legion to celebrate my triumph over Gaul. Everyone knows that, Pompey!

Lepidus: Alright let’s not fight. I broke it, let me go into exile for it, Dictator.

Sulla: No. Who broke it?

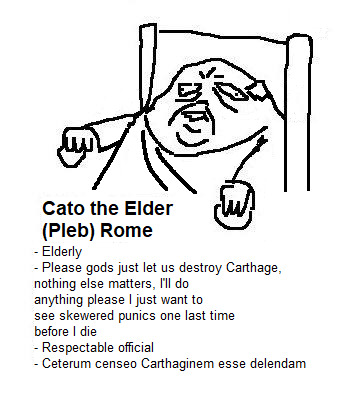

Crassus: [whispering] Dictator Sulla, Cato’s been awfully quiet…

Cato: Really?!

Crassus: Yeah, really!

…

Sulla: I broke it. I rewrote the constitution in a way that set them up for class warfare. I predict ten minutes from now, they’ll be at each other’s throats with blood on their togas and a tribune’s head on a pike. Good. It was getting a little chummy around here.

#the most unrealistic part of this is cato being quiet#reblogging in honor of harriet flower#parks and recreation#just roman memes#incorrect roman quotes

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wrapping Up the Republic with Harriet Flower

Alright! I posted my review of the book overall yesterday, but let's dig into the final chapters of Harriet Flower's Roman Republics anyway, because her arguments here are interesting even apart from the rest of the book. Plus, this is where we get to Marius, Sulla, and other familiar faces for late republic nerds like me.

According to Flower, Julius Caesar wasn't the man who broke the republic. Nor Pompey, or Cato, or anyone in their generation. She doesn't minimize their mistakes, but she believes they grew up in an an already-broken system, thanks to Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

Rewind a bit to the Social War, 91-88 BCE. Flower argues that this was the republic's first true civil war, and that it broke out due to Rome failing to extend citizenship to the Italian allies in peacetime. I think she overstates our certainty for the war's cause - it's not actually clear if most Italians sought citizenship or independence. However, I agree with her that the Social War left deep and lasting wounds at all levels of Roman and Italian society, and the republic never really re-stabilized afterward.

The Social War in turn feeds into the conflict between Sulla and Marius. She also argues that the simultaneous crises of the Jugurthine, Cimbric, and Second Servile Wars lent credence to the idea that one strong leader was more competent and dependable than the unpopular Senate. In this case, said leader was Gaius Marius. His achievements in these wars gave him the base of support needed to make a highly irregular bid for the Mithridatic command - deposing Sulla, who in turn marched on Rome.

Flower portrays Sulla very negatively. And I understand why, but it's odd that she doesn't mention he was Rome's duly elected consul at the time, and that the referendum deposing him was unprecedented, and possibly forced through by violence. He did, in fact, have a legal argument for why he refused to step down, and this was probably one of the reasons his soldiers followed him to Rome. Flower attributes the soldiers' motives to merely wanting the booty of war for themselves - another example of her assuming that poor or working-class men had few political opinions of their own, little love for democracy, and merely acted as extensions of their generals.

(You may have noticed I am not a fan of that assumption.)

I do appreciate that Flower draws a throughline from the violence associated with the Gracchi, to the death of Saturninus, to the Social War, and then to Sulla's first march on Rome, because it helped me see how violence in the city, and shows of force from the Senate, had been escalating since before Sulla had even joined the Senate. This does not excuse his actions, but does help explain why he may have thought it legally justified, along with his own self-preservation. (Flower does not mention that a few weeks before, Sulla had nearly gotten killed by a riot in Rome instigated by the same tribune who then tried to depose Sulla and give the Mithridatic command to Marius!)

So, Sulla marches on Rome, outlaws twelve enemies; Sulla leaves Rome; Marius and Cinna besiege and take over Rome; Marius dies of too many consulships and Cinna, undeterred, proceeds to keep giving himself consulships. Flower doesn't hesitate to criticize the Marians, either. She plausibly argues that Rome was a dictatorship in all but name during Cinna's tenure.

However, she reserves the greatest part of these final chapters for critiquing the new laws Sulla imposed after he retook the city and became dictator. Flower believes that, rather than being a "return to tradition," that "strengthened the Senate," Sulla's constitution was a radical departure in several ways, and this unwelcome novelty undermined the Sullan Senate's credibility.

She makes good points in support of this argument:

That enfeebling the plebeian tribunes was radical, unpopular with the people, and greatly damaged the government's legitimacy in the eyes of the people.

That doubling the size of the Senate while purging the opposition leaders, on top of all those who'd died in the Social War, created a horrific brain drain effect and paralysis.

That few people could take the rule of law seriously after Sulla had imposed it by force of arms, not through voting.

That political discourse in and out of the curia was greatly damaged by the above points. Particularly because the tribunes could not propose and discuss legislation in contios for some time. (I have to wonder if strangling these open-air, traditional forms of discourse may have caused people to turn to violent collegia, and uprisings like Lepidus Senior's and the Catilinarians, as extreme alternatives for people who felt oppressed. But that's just speculation.)

She doesn't talk much about the proscriptions, but I would also add those as a major force of destruction for both public debate and government credibility.

I'm not sure I agree with all her points, though. For instance, she claims that Sulla attempted to assert a government ruled by laws instead of custom, with a greater focus on the court system to enforce these laws on senators. I want to see more evidence to back this up.

Much of Sulla's constitution was dismantled in the decade after his death. Flower calls this the era of Sulla's republic, up till 49, and she sees it as a fundamentally unstable time because of what had happened before. She's rather harsh toward all of Cicero's generation and how they handled the situation, but she especially thinks the first triumvirate shut down republican politics from 59 onward.

I really think she overstated the first triumvirate's power. Robert Morstein-Marx and Erich Gruen have comprehensively demonstrated that Caesar, Pompey and Crassus' alliance only operated intermittently, lost as many elections, plebiscites, and trials as they won, and doesn't seem to have functioned very differently from alliances like Catulus-Piso-Cato. I also think she is flat out wrong in attributing the breakup of Caesar and Pompey's alliance to the deaths of Crassus and Julia in 54 - we don't actually see Caesar and Pompey break apart until four years later. For details, see my liveblogs of Morstein-Marx's Julius Caesar and the Roman People and Gruen's The Last Generation of the Roman Republic.

I am hesitant to use words like "irreversible" when discussing history. My own view of the republic's decline is more probabilistic, such that it became more or less likely that the republic would break as new events happen, before the inertia of Augustus' regime became too powerful to overthrow. However, I do think Flower has made a good case that Sulla's constitution could be seen as a new government in its own right, one that never really stabilized or regained the credibility of the pre-Marius Senate, which made it very difficult for Cicero and Caesar's generation to collaborate and govern the city.

So, those are my mixed thoughts on the final chapters. Some parts I like, some I don't, but I am glad I read it.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think there is not enough slash fanfiction about Marcus Porcius Cato (the Younger obviously). There is homoerotic drama around him in Plutarch's Cato, that goes underutilised.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

RIP Cicero you would’ve loved having Twitter beef

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

shaking that guy who had the herculaneum library really really hard by the shoulders . please please please please please have a copy of all the things i personally want to read. youre nothing

414 notes

·

View notes

Text

woke up and immediately got emotional about the herculaneum papyri again

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just finished Harriet Flower's Roman Republics. I'll write up my notes on the final chapters later, but here's my general thoughts for now:

I like the basic idea of dividing the republic into more than just the early/middle/late periods, but I don't think all of Flower's proposed divisions are well supported.

She brings up some good points that are often overlooked (like the impact of the Servile Wars on Tiberius Gracchus' tribunate and the Cimbric War), but I disagree with others (e.g. characterizing the first triumvirate as a decade-long hegemony).

I wish she'd included a more detailed timeline of milestone laws and events - although doing so may have undermined her argument.

I also believe she understates the impact of the First and Second Punic Wars on Roman politics.

I would've liked to see more concrete, specific examples defining the political culture of each time period as distinct, a la Gruen's systematic, multi-tiered argument in The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. Granted, that's very difficult for earlier time periods, but that should serve to emphasize our uncertainty there. As-is, the book feels more like an outline than an in-depth analysis. Gruen also makes several arguments opposite to Flowers which I don't think she adequately addressed.

The complete skipping of 300-180 BCE, without even acknowledging it, still bothers me. A lot.

On the bright side, I do think she effectively demonstrates that the Roman republic changed greatly from 509-133 BCE, perhaps more than most people give it credit for. And I think she makes a solid case for viewing Sulla's constitution as a new form of government in itself, one that was never fully accepted by the people, and that this made it more vulnerable to coups and harder for the new Senate to work together.

It's an interesting book, and sometimes thought-provoking, but needs to be read very carefully so you can decide which parts you agree and disagree with. I have enough reservations about it that I won't be putting it on my favorites list. Still, I respect the author's work, and might suggest it for people who enjoy reading critically, want to examine an alternative viewpoint, and who already know a fair bit about Roman history.

#i only review/liveblog authors i respect on here. if i detest someone i prefer not to give them free publicity at all#book review#harriet flower#roman republics#jlrrt reads

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

That's one book for every 2.7 years he lived. Given that he didn't do anything notable for the first thirty, I can only imagine what they were about.

Volume I: Baby Lucius and I Find Weird Bugs in the Road

Volume VI: Best Lute Tunes to Pick Up Girls

Volume VIII: Blackjack and Orgies

Volume XII: Don't Ask How I Got the Money to Run for Quaestor

Volume XVVI: I Think I Messed Up Numbering These

Volumes XIX, XX, XXI: War, What is It Good For? (My Career!)

Volume XXII: Blackjack and Orgies

#and you thought cicero never shut up#lucius cornelius sulla#harriet flower#roman republics#just roman memes#jlrrt reads

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

I haven't yet had the chance to read it (I've only briefly flipped through) but I think The Roman Toga by Lilian M. Wilson might be a helpful book. It's quite old (from exactly a hundred years ago, 1924) but I don't think there has been much change in the academic topic of togas recently (forgive me if I'm wrong) and I'm assuming it shouldn't be horribly outdated. It even has a section on how to make a toga! Also the photos of different toga reconstructions are super funny and creepy and black and white.

!! Well, it sure can't hurt! Thank you, one of my favorite hobbies is tracking down obscure books.

#it's like a treasure hunting game for me#togas#just roman asks#to read#lilian wilson#the roman toga

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

By the way, if any of y'all found me because of the weaving/knitting post and y'all know how actual late republican togas were constructed and shaped, I would love to hear it. (My sources are contradictory!) Asking for a tiny, pants-hating friend.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEW INFO NEW INFO NEW INFOOOOO

789 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erich Gruen, The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, pp. 374-375

(Thinking about how the political values and voices of ordinary people are often erased in history books again. This particular passage is part of Gruen's debunking of "client armies" prior to 46 BCE, arguing that the common soldiers had more agency than they're usually credited for.)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

we're all lined up together in the ghost library trying to check out non existant books while the poor harried shade of the villa of the papyri guy has to check if he's got them

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Growth of Political Violence in the Late Republic, According to Harriet Flower

On to the period of 133 to 80 BCE in Harriet Flower's Roman Republics! Flower rightly characterizes this period as one of escalating violence and a breakdown in trust in the republican system. However, I only partly agree with her analysis as to why.

The major events she discusses are:

The conflict between Tiberius Gracchus, the tribune Octavius, and Scipio Nasica Serapio. Flower sees all of them as violating republican norms and being in the wrong somehow, and I appreciate her impartiality here.

She sees the deaths of Gaius Gracchus and Saturninus as escalations in both the scale and kind of violence. Serapio acted as an individual on his own initiative; then the Senate as a collective body vs. the followers of Gaius Gracchus; then the violent gang that killed Saturninus apparently evading control by Rome's consul, Marius. In particular, she interprets Marius' withdrawal from politics as a military defeat as much as a political one.

I agree with her view that the Social War could either be classified as a civil war or an external one, and that the destabilization it caused directly fed into the wars of the Marians vs. Sulla. I particularly like her analysis of the tribune Sulpicius' actions, and how by supporting Marius' (irregular) appointment to the Mithridatic command Sulpicius hoped to advance his own legislative program. It connected a few more dots for me.

On the other hand, I think she overstates the impact of the Marian reforms. She characterizes the post-Marius army as mostly landless, partisan veterans who were willing to resort to arms because they couldn't hope for representation in the Centuriate Assembly.

But the property requirement for the army had been trending downward for decades; there was no sudden, drastic change in the army's composition and incentives yet. And as Flower herself notes, Marius had in fact secured pensions for his veterans, so what would they be agitating about?

Thirdly, it isn't actually clear whether such "client armies" were really more loyal to their generals than to the republic. Both Sulla and Caesar had to make appeals to their soldiers justifying themselves as defending the republic and delegitimizing their opponents before they could march on Rome, and several times Roman soldiers actually refused to fight other Roman armies, e.g. Cinna's men refusing to fight Sulla's, and many of Pompey's deserting to Caesar. It's not even clear whether Caesar employed veterans for violence during his first consulship, as all the allegations of it seem to come from later historians.

I'm not happy about Flower's implication, intentional or not, that poor and working-class veterans were more prone to violence and anti-republican behavior than wealthier veterans were, or that they would automatically follow their generals' power-grabs just for the sake of getting paid. I think there's a strain of classism that sometimes makes us overlook the "Roman mob" and soldiers as gullible and mercenary, rather than as having political values and voices of their own.

(My view here is particularly influenced by Erich Gruen's survey of working-class political life and veteran behavior in The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, and Robert Morstein-Marx's Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic and Julius Caesar and the Roman People. Those books are interesting counterpoints for Flower's.)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

786 notes

·

View notes

Text

I could have fixed Julius Ceasar

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcus Crassus explaining to the judges why he was so interested in a Vestal virgin.

41 notes

·

View notes