Text

Critical Literacy in Accessing Internet Reference Resources

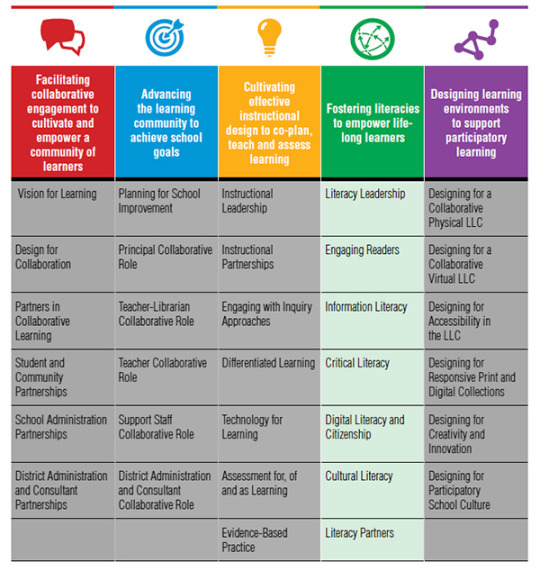

Teaching critical literacy skills is a top priority for a teacher librarian. “Fostering literacies to empower life-long learners” is one of the five themes in the Leading Learning Framework (page 10), and half of the bullet points in that theme are about critical literacy. In my experience this can be challenging stuff to teach for elementary students, who use the internet all the time, but aren’t very good at it.

Different strategies are needed depending on the age of the students. As with most things, it’s going to be easier to lay the groundwork for primary students by starting offline rather than on Google. “Understanding what they’ve read and making it their own” seems to me to be enough of a learning goal to keep students busy for most of their primary years. This can be done through reading response, writing activities, or research, and all of these are valuable, curriculum-supported areas of study. But at least as far as critical literacy is concerned, I think it’s very important that the research aspect be given special attention. For another course we read a paper by Daniel Willingham which made the case that critical thinking skills don’t transfer well between disciplines. So how much the ability to hear a story and then summarize it in your own words transfers to reading a book or a website and then recording facts from it is an open question. If research skills are the goal, that’s what needs to be taught and practiced.

For both primary students and intermediate students, whether they are using books or the internet as their source, I would set up a series of small, stand-alone activities for them to practice the skills of finding answers to questions and then rephrasing the material into their own words, recording facts in note form and then turning those notes back into sentences or into some other format (diagrams, pictures, infographics, etc.). These activities could be done in collaboration with classroom teachers, but most importantly, they ought to be done shortly before a class does any sufficiently sized research project in class. Communication with classroom teachers early in the year is key, in order to know those teachers’ plans and how best to schedule around them. Using library prep time to support classroom teachers in this way fulfills the core themes of the teacher librarian position, justifies this time to other staff, and sets students up for success going forward.

For intermediate students, we can incorporate additional goals as well. To note-taking skills I would also add internet searching skills (how to use keyword searches in search engines as well as in district-curated online resources, how to sift through the results to find likely useful resources, judging author intent, etc.) and media literacy in weighing the validity of a source (including cross-referencing and checking for citations or author info). As with note-taking skills, I think the best way to approach these topics is in isolation first, teaching them explicitly with short, focused activities, before immediately putting them to use in more authentic learning activities such as research projects. I’ve been the classroom teacher trying to fit in basic Google skills or a visit to the Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus page or kidsboostimmunity.com before jumping into research projects, and I know how much I would appreciate having another teacher who can take on some of that important work and give it the time that it deserves.

Resources used

Canadian Library Association (2014) Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada 2014.

Public Health Association of BC. “Kids Boost Immunity.” 2024. https://kidsboostimmunity.com

Willingham, Daniel. T. (2019). How to Teach Critical Thinking. Education: Future Frontiers: Occasional Paper Series. New South Wales Department of Education.

Zapato, L. “Help Save the Endangered Pacific Northwest Tree Octopus from Extinction!” 1998-2022. https://zapatopi.net/treeoctopus/

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Evaluation Plan for Reference Services

Current State of the Reference Collection

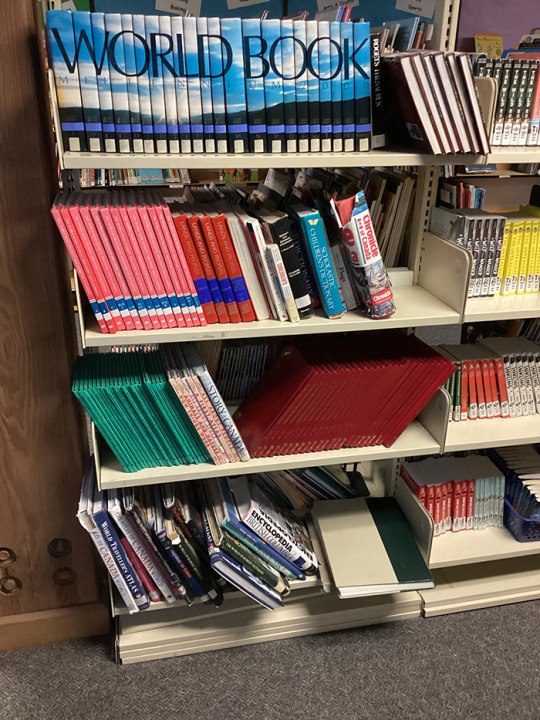

The physical reference section at my school currently consists of:

- Three different encyclopedia sets from within the last 25 years

- Smaller sets of encyclopedia focused on animals, geography, and science and humanities

- Several single volume reference books on music, art, geography, Canadian history, etc.

- Several atlases

- Some dictionaries and thesauruses.

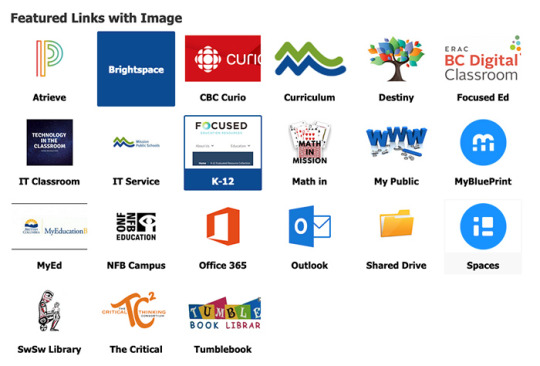

There is also a district-wide page of digital reference resources available online with a student or staff ID, which includes:

- A variety of online encyclopedia aimed at various age levels or with different focuses (science, history, humanities) and in French and English

- An Indigenous themed online magazine

- Useful subscription-based resources in science, French, and history

- Math games

- NFB videos

- News for kids

- Tumble Books (ebook and audiobook site)

Let’s judge the collection as a whole, including the digital side, by the evaluation criteria in Riedling and Houston (page 23). This is not the intended use of these criteria, which are intended for individual resources, but they can provide a set of priorities for next steps.

Content scope: The print collection does well here. I can see no egregious gaps in topic. It could perhaps do with more art themed resources (for an arts-based school), and more Indigenous materials. The digital collection is more spotty. It has encyclopedic resources, but largely sticks to general knowledge in science and history, without anything in depth, and with nothing on language arts or art.

Accuracy, authority, and bias: High marks here. All of these resources, physical and digital, are produced by established publishers with no obvious, unconventional biases.

Arrangement and presentation: I would argue that both types of reference are underused at the moment, in part because of how they are presented to users (teachers and students). More on this later.

Relation to similar works: There does seem to be some significant overlap in the digital collection, with a lot of very similar encyclopedia resources. I assume this is the result of sets of resources having been purchased together, so may be unavoidable.

Timeliness and permanence: The physical reference section is largely out of date. Riedling and Houston (page 18) suggest expiry dates on the order of five years for all but the history resources (which get 15), and Mardis (page 150) suggests similar dates. This section of the library has been gradually shrinking as books get weeded out, but there has been little new investment in it. The digital collection is of course up to date and updated regularly.

Accessibility/diversity: Having the digital collection accessible outside of school certainly helps here. The French language resources might not be a huge benefit to our school, but given that these resources are district-wide, they are vital to French immersion students.

Cost: Many of the limitations on the current state of the collection come down, I’m sure, on cost issues.

What Needs to Change

Budgetary limitations and the limits of what digital resources actually exist are probably always going to keep us from achieving even the “acceptable” standard of 7000 nonfiction or reference resources from Achieving Information Literacy for a school of our size (Page 28). But nevertheless, the physical reference section needs to continue to be weeded, and new resources need to be acquired to replace old ones so it doesn’t shrink forever. I’m told by the teacher librarian that the physical reference section doesn’t get a huge amount of use, so while there wouldn’t be circulation data either way on books that don’t leave the library, this indicates to me that usage patterns aren’t enough of a defence to keep the least up to date books from being removed and replaced. What most needs to go depends on checking the publication dates for each resource (which I can’t do at the moment since it’s spring break), and what needs to be acquired is likewise dependent on what goes. One thing that I think should rise to the top of the list, though, is encyclopedias. We don’t need as many encyclopedias as we’ve got when we also have so many digital encyclopedias. And for resources to acquire, I mentioned art resources (an encyclopedia of famous artists, for example, or something similar) and resources on Indigenous people. I think it might also be worth considering some bilingual dictionaries, French because intermediate students take French, and perhaps some other languages that fit with languages that have strong representation in our school like Korean, Punjabi, or Spanish. This would support diversity and accessibility, and there is no digital equivalent in the online collection.

The digital collection is district-wide, so making changes there is more challenging, but still a good idea. There are gaps that could be filled compared to the curriculum as a whole, in art, language arts, math, ADSL, and Indigenous topics. The main change I would like to see to the digital collection, though, is to make it more accessible to students. Based on casual conversations with other teachers, I suspect many don’t ever use this page or know what’s there. It is not well organized, nor is there an easy way to get to it. You can access it from home, but our students don’t generally know how. The resources in our digital collection don’t come cheap, I’m sure, and most would be an annual subscription. We are not getting our money’s worth if the resources languish on a hidden webpage.

A Plan of Action

Especially with the digital collection, other parties will need to be involved in order to change anything. My first step would be to talk to every teacher at my school to get a more factual understanding of how the current digital resources are being used. My initial impressions might well prove to be wrong, or there might be a need I hadn’t even considered. This might be a good time to bring out the Concerns-Based Adoption Model to chart the results. Armed with that survey data, I would then talk to other teacher librarians in the district. The digital resource collection is district-wide so I wouldn’t get very far without their support. This would also be an opportunity to find out more about how the existing collection was selected in the first place. If there is a procedural document on this topic, I haven’t been able to find it. Any changes I might propose could involve conversations with IT staff or district administrators, and I want to be able to talk to the right people.

At the very least, I think all of these steps are worth going through so that other teachers are aware of what resources we have and are thinking about them. If I can’t get other parties on board with looking for resources that can be added, then promoting what we have is my next best option. I could create a page of my own that has links from our collection as well as links to free online resources that seem useful, and make that page available to teachers and students at my school. But that’s a back-up plan. Broadening and redesigning the interface for our digital resources is the best possible outcome. Each step of the process, once progress is being made, can be shared with staff at staff meetings.

For the physical resources, the path forward is much clearer. That is, continue to weed out books on an annual basis, keep records of when I notice those resources being used throughout the year (since circulation data won’t be generated for them), and allocate some of the budget towards adding about as many new materials as I’m removing. There doesn’t need to be as much participation from other people in this process, but keeping staff and students aware of changes made to the collection is always a good idea. No one will ask for resources they don’t know are there.

It’s difficult to set a timeline for any of this. The goal, if I were teacher librarian tomorrow, would be to start as soon as possible so that changes might be possible by September. The main thing would be to start moving forward and then deal with obstacles as they come. At the end of a year at the most, it would be good to have concrete progress towards improving the reference collection.

Resources used:

Asselin, M., Branch, J.L., Berg, D. (2006) Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Canadian Association for School Libraries.

Loucks-Horsley, Susan. (1996). Professional Development for Science Education: A Critical and Immediate Challenge. National Standards and the Science Curriculum. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co.

Mardis, Marcia A. (2021) The Collection Program in Schools: Concepts and Practices (Seventh Edition). Libraries Unlimited.

Riedling, Ann Marlow; and Houston, Cynthia. (2019) Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools and Tips (Fourth Edition). Libraries Unlimited.

0 notes

Text

Using the Concerns-Based Adoption Model to Elevate Genius Hour Research

At my school, February and March means it’s time to build genius hour projects. This is the perfect opportunity for teachers to look at how they help their students develop the skills they need for inquiry-based learning, and the perfect opportunity for some collaboration with a (future) teacher-librarian.

Teacher #1

Sarah is a grade 3 teacher who has been teaching for about 20 years. Because she has such a wealth of experience, it’s not easy to find something I can help her grow with. Her approach to teaching research skills with her students for their genius hour projects is scaffolded, multi-platform, and developmentally appropriate. She starts with a carefully-structured research project where she walks students through finding and highlighting the key information in an article about an animal (squirrels, for example), assesses them on their comprehension, and gets them to write point-form facts and then a paragraph about the animal. She then lets them choose an animal for their individual genius hour projects and asks them to go through similar steps. She provides them with materials from Epic Books, the school library non-fiction shelves, and Youtube. She doesn’t concern herself too much with whether or not they plagiarize passages, or whether they cite their sources, as she wants to focus on the level her students are at.

(from Loucks-Horsley) Stages go from 0 to 6.

Looking at the stages of concern, Sarah is well into stage 4, “Consequence,” when it comes to improving her students’ inquiry skills. She has materials she’s happy with, and knows what she’s doing and why. If there is room for growth, it must be in refining her approach, using colleagues as resources, and refocusing her efforts into new areas.

I would like to work with her on the question-building stage of her students’ research. Inquiry is built on the asking of questions, and while I really like the workflow she’s developed for her students on these projects, I think it should be possible to add in more room for them to come up with questions on their topics and go searching for the answers. I would like to collaborate with her on a lesson on “green light” and “red light” questions, based on School Library Media Activities Monthly, focusing not just on what sorts of questions fit those criteria, but also what to do when the answers won’t be found in the order that they ask them in. I think she’s right to keep her students in the walled gardens of a handful of research venues, given that most grade threes aren’t ready to be set loose on the whole internet and go any deeper than the first page of Google. But the consequence of this is that students will have to learn the really valuable lesson that finding answers in finite resources takes some techniques (such as writing down answers as you find them while reading, searching indexes and skim reading, and what to do if there is no answer available).

Teacher #2

Allison is a grade 4/5 teacher who has been teaching for about ten years, although this is the first year she has taken the lead on her own classroom for a whole year. Her class is also doing genius hour projects, although they’re a little further up the spiral of developing their inquiry skills. Allison lets her students pick their topics and allows them full access to the internet for research, albeit with support. She models research skills, presents a variety of possible sources for students to use including books from the library and video, uses a template for their note-taking, and encourages them to take notes that aren’t copying and write down sources.

She finds two elements most challenging during these projects. The first is time. She wants to be able to spend more time prepping students ahead of the start of their projects, modelling good research strategies, and giving them smaller projects to work on before throwing the school-wide genius hour projects at them. She feels the all too common squeeze between the breadth of the curriculum’s expectations and the stage her students are at when she gets them. The second thing she wants more of is resources at a level appropriate to her students’ reading level (she mentioned Epic as a source she wished she had access to). This sounds to me like she’s at the “management” level on the Concerns-Based Adoption Model, at least in the areas she has concerns about.

There is of course room for professional development here. But I think the best way to approach how to help her help her students is to provide her with what she lists as her biggest want, which is time. As a teacher-librarian, I can, and should, use the prep coverage time I would have with her class to do some of the prep work she wishes she had time for. A few heavily scaffolded, smaller inquiry projects done earlier in the year before genius hour starts would give her students a head start on the skills they need for larger projects. If we collaborate on the language and expectations used for this instruction, the move from one project to the next can be more seamless.

The other need she has is more resources. I could take the time to go through with her the alternate resources that we do have, such as the online encyclopedias we have access to, to see if she is aware of them or how useful she thinks they would be. But this also seems like a direct request for resources our library currently doesn’t have. Knowing that two teachers have spontaneously expressed a need for a specific resource by name (Epic), tells me it would be worth investigating whether it can be acquired for the whole school. It would definitely get used.

Upon investigation there is a free version of Epic that classrooms can access during school hours. I think it’s worth investigating whether the full version could be acquired out of the district budget, but at the very least, I will have to let Allison know that the free version is already an option for her. Even without being a teacher librarian yet, perhaps some good can come out of these conversations immediately.

Resources

Epic! Creations, Inc. Epic! https://www.getepic.com/

Loucks-Horsley, Susan. (1996). Professional Development for Science Education: A Critical and Immediate Challenge. National Standards and the Science Curriculum. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co.

School Library Media Activities Monthly. (January 2009). Assessing Questions. School Library Activities Monthly. Vol. 25, No. 5.

0 notes

Text

What Would Be the Five Reference Tools That Your School Learning Commons Should Have for Staff and Students?

It’s a fair question to ask what would be the key pieces in a successful reference collection, but it’s not an easy one to answer. None of our resources get so specific as to describe a list of can’t-do-without items. So the best place to start is with what the purpose of a reference collection is. Riedling and Houston define a reference resource as “any material, regardless of form or location, which provides necessary answers.” (Page 3) In describing an exemplary collection, Achieving Information Literacy says among other things, that “All resources are catalogued, inventoried, organized and circulated through the school library, and they are available to all users.” (Page 26) So we need resources that provide a lot of facts to answer questions, and resources that are maximally accessible to users. We have a lot of lists of possible resources that a reference collection MIGHT have, but no authoritative list of what specific resources a reference collection MUST have.

Rather than look up specific books or other resources, I think it’s much more useful to create a wish list of ideal (but likely to exist) resources, and then leave filling those slots to what can be sourced when those decisions need to be made. Here, then, is my list, with a description of each item and why it’s necessary.

The Encyclopedia

There is no greater fulfilment of the stated criteria than an encyclopedia, specifically an online encyclopedia that gets updated regularly and is written at an appropriate reading level. Assuming staff and students already have access to the internet at large, the internet can go a long way towards filling the need to answer any question with an ease of access. But librarianship is curation, and an online encyclopedia with a breadth of curated knowledge (and a subscription fee) is something that needs to be actively acquired. Not acquiring one seems like neglecting the single best tool to fulfill the objective.

The Indigenous Curriculum

Classroom teachers are often left to their own devices to find resources to teach specific subjects within the curriculum. In my experience if there is one area where the gap between teacher and assessable resource is widest, it’s the various points throughout the BC curriculum that puts Indigenous knowledge front and centre. If I only get five items to make the tentpoles of my reference collection, one of them needs to work to close that gap. Collection mapping always emphasizes the need to match the collection with the curriculum. So resources for students on Indigenous people and culture are important. But I’m going to rank resources for teachers higher on my list. Most of us don’t have the general background knowledge to teach Indigenous content. Nor is the internet a reliable source. When an expert isn’t available we need an authoritative book, or set of books, or online resource.

The Canadian History Overview

The second most difficult resource to find without the aid of a school library, I find, is good resources on Canadian history. For this subject I’m going to prioritize student needs over teacher needs, as this is an easier area for teachers to access their own background knowledge, and the bigger challenge is to find reference sources that are written with students in mind. Whether it’s a book, or an online source, or a documentary series, or an up to date textbook, this is another gap that needs filling.

The Atlas

You won’t find any dictionaries or thesauruses on my list. The free online equivalents make their print counterparts… if not obsolete, then at least less essential. But one type of resource that I don’t feel the internet can do a better job at is atlases. A mapping app is a useful tool, but it has a very different (and not superior) functionality to a good print atlas.

The Fun Fact Book

None of my tentpole items so far directly address inquiry-based learning, which is one of the main needs a reference collection fills. There is no way that any single resource can answer every question that a student might ask. But a resource that can answer some unexpected questions, and more importantly one that is browsable and fun, seems to strike at the heart of self-directed inquiry. I would go so far as to say that at least one good resource of this type is an essential in a collection.

Obviously no reference collection would be complete with just these five items. But they each do a disproportionate job at filling the needs of students and staff, and I would say that no reference collection can be complete without them.

Sources:

Asselin, M., Branch, J.L., Berg, D. (2006) Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Canadian Association for School Libraries.

Canadian Library Association (2014) Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada 2014.

Riedling, Ann Marlow; and Houston, Cynthia. (2019) Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools and Tips (Fourth Edition). Libraries Unlimited.

0 notes

Text

Evaluation of a Resource

Amazing Animals of the World is a set of encyclopedia with entries about a wide variety of animals. It was published in 1995. It comes in 24 slim volumes. Each volume has one-page entries for animals in alphabetical order, with photos, maps, basic facts, and writing about behaviours, lifestyles, and habitats. There are about 1000 entries total. The final volume also includes a glossary of terms and an index of all the animals listed. It’s in the reference section of my school’s library, so there isn’t circulation data on it.

My first impression of the series was that there is no way it could compete in breadth with the internet. But I considered the specific species of animals that students in my class have picked for their current genius hour projects, some of which are quite obscure (such as an axolotl or a proboscis monkey), and from that list there were only two animals I couldn’t find entries on: dogs, because the encyclopedia doesn’t include any domesticated animals; and narwhals. So maybe 1000 entries is enough for the purposes of most of this resource’s audience. The organization of the entries is also about as well done as a print collection could be. The entries themselves are in alphabetical order by the full name listed (so “plains zebra” is under P, not Z), but the index has double listings with and without adjectives, and also sorted by family. Any student who knows how to use an index should be able to find what they’re looking for, if indeed there is an entry for it. The age of the resource is also not a huge concern. Achieving Information Literacy recommends a shelf-life of ten years for the average book, and the CREW method (see: The Collection Program in Schools), which gets more granular by subject, also recommends a shelf-life of ten years for natural history books. For the level of depth the entries get into, though, not much can have changed for most of these species in the past 30 years. They are likely to still be factual, and this resource would have been a big investment when it was purchased. It deserves some leeway.

The main shortcoming of this resource that I can see, then, is the brevity of each entry. One page of information, even one page that is written at the right reading level, presented in a consistent, easy to understand format, with reasonably current information, is not enough to spin a whole research project out of. This resource cannot replace the internet, and would not serve intermediate students for much more than casual browsing. Perhaps its biggest asset would be for primary students. Despite being written at a more intermediate level, it is definitely easier to read for primary students than Wikipedia could ever be.

Let’s test it against some criteria. These are obviously based on Riedling and Houston.

Accuracy/Authority: Published by Grolier. Seems legit. Also it’s in the library so at some point it was vetted by a professional.

Currency: 20 years behind CREW. Willing to give it leeway for the sake of merit.

Format: Relatively easy to navigate.

Indexing: As good as print will allow (entries are triple indexed by noun, adjective, and animal family).

Objectivity: No biases evident on casual inspection, or rather, biases seem in line with the same biases students might have in terms of which animals interest them.

Scope: Age appropriate, intermediate reading level, 1000 entires.

Curricular fit: K (animal basic needs, adaptations), 1 (animal classifications), 2 (metamorphosis), 3 and 4 (biomes), All (inquiry— animals are a popular topic).

A New Resource

Even if it’s not time to weed out Amazing Animals of the World, the age of the series that I’m willing to give it leeway on will only grow with time, so a supplementary resource, at least, seems appropriate. Finding a resource that can replace (or supplement) this series is a challenge. Our library already has the online resources National Geographic Kids and Worldbook Kids. Online resources like these are best suited to the task of providing age-appropriate information on a wide range of searchable topics. Both resources seem to have a similar level of breadth and depth to Amazing Animals. So what we don’t have, then, is a resource that can fulfill Amazing Animals’ other assets, its browsability and its visual appeal to younger students.

Arcturus publishes a series of animal resources that might fit that bill.

Children’s Encyclopedia of Animals (by Dr. Michael Leach and Dr. Meriel Land) ISBN: 1788285069

Children’s Encyclopedia of Ocean Life (by Claudia Martin) ISBN: 1789506018

Children’s Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs (by Clare Hibbert) ISBN: 1784284661

Children’s Encyclopedia of Birds (by Claudia Martin) ISBN: 178950600X

Focused Ed, CM Magazine, and Quill and Quire don’t have reviews on any of these books. Goodreads has little, and the reviews that Amazon has are positive, but written by parents rather than educators. Nevertheless, from what I can see of the books, they look appealing. Collected together these books won’t have as many entries as Amazing Animals. But what they lack in breadth they make up for in visual appeal and in currency. Amazing Animals does have some entries on extinct animals, and that is one area where the 20 years of additional research between its publication and Children’s Encyclopedia is likely to make a significant difference. According to the Arcturus catalogue, they have two additional encyclopedias to be released this year: Children’s Encyclopedia of Biology, and Children’s Encyclopedia of Prehistoric Life. They also have other books in the series that are not about animals. On Amazon each title is listed for $20, and in the Arcturus catalogue they’re each listed for 10 pounds (about $17 CDN).

To put this series up against the same criteria, then:

Accuracy/Authority: Published by Arcturus. The collection in their current catalogue looks professional.

Currency: Publishing dates between 2017 and 2020. Well within CREW standards.

Format/Indexing: Unknown. Well-designed interior pages, though.

Objectivity: Unknown, but no obvious problems evident.

Scope: Age appropriate, intermediate reading level, 128 pages per book, maybe 250 entries total in the set of 4.

Curricular fit: K (animal basic needs, adaptations), 1 (animal classifications), 2 (metamorphosis), 3 and 4 (biomes), All (inquiry— animals are a popular topic).

So while I don’t recommend weeding Amazing Animals out of the collection yet, I do recommend adding a set of Children’s Encyclopedia to the reference section in anticipation of the former eventually needing to be removed.

Sources:

Amazon.com Inc. (2024) Amazon. http://www.amazon.ca

Arcturus Publishing. Arcturus Children’s Catalogue. (Spring 2024). https://arcturus.egnyte.com/dl/usGr7upzWQ

Asselin, M., Branch, J.L., Berg, D. (2006) Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Canadian Association for School Libraries.

Gale. Nat Geo Kids. https://go-gale-com.bc.idm.oclc.org/ps

Grolier Inc. (1995) Amazing Animals of the World. Grolier Educational Corporation.

Mardis, Marcia A. (2021) The Collection Program in Schools: Concepts and Practices (Seventh Edition). Libraries Unlimited.

Province of British Columbia. (2023). BC’s Curriculum. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/

Riedling, Ann Marlow; and Houston, Cynthia. (2019) Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools and Tips (Fourth Edition). Libraries Unlimited.

World Book Inc. (2024) World Book Kids. https://www-worldbookonline-com.bc.idm.oclc.org/kids/home

0 notes

Text

Digital versus print reference

The other day I went to check out the reference section of my school’s library, because I don’t think I ever had before, and I wanted to see how practice met theory with the small sample set of my own elementary school. The reference section is one bookshelf wide, with a single set of encyclopedia, some atlases, some themed reference book sets, and assorted other non-fiction resources. The teacher librarian mentioned that it had been steadily shrinking over the years, as old books get weeded out. She also mentioned that it gets very little use from students compared to other parts of the library. We also have, in our district, access to a variety of online websites, apps, and periodicals.

All the theory we’ve read so far encourages a balanced approach to library reference, with both hard copy and digital tools available. Riedling and Houston call this “maximization of information sources in all formats.” This seems right to me. I would take this as the main test for making decisions on what resources to include in a “reference section.” Or to put it another way, the best resource should get the job. An atlas in print and an atlas online have different strengths. Google Earth or Google Maps can convey information that no book could ever do. But a good print atlas can also be browsable and curated in a way that Google apps are not. They both have merit, and would have a place in my library (when I have a library). A general encyclopedia set, however, has a much harder time bringing something to the table that an online encyclopedia can’t do better. World Book in print, especially an out of date edition of World Book, isn’t necessarily more accurate than Wikipedia. And while Wikipedia isn’t written at an elementary student reading level, we also have multiple online encyclopedia (including World Book) that are. Dictionaries and thesauruses might still get use, and I can see value in spending the time to train students in how to navigate them. But at the same time, I don’t expect them to get as much use as free online alternatives.

If my primary motivation is utility, I can’t see a reason to actively dismantle a library’s reference section. We have profession-wide criteria for judging the utility of any given resource, such as MUSTIE or the recommended shelf-life of resources suggested in Achieving Information Literacy. A reference section can be held to the same standard as the rest of the library’s resources. But reference sections as a concept are highly vulnerable to replaceability by digital resources, simply by the nature of the kinds of material they contain. That is, large collections of quick and up-to-date facts.

Other sections of the library hold up much better when compared with digital media. Most of the libraries I’ve seen do not have as many non-fiction books (or digital equivalents) as the Canadian Association for School Libraries recommends (they recommend 70-85% non-fiction or reference). CASL also recommends an array of audio and visual resources that we don’t have, and I worry that in the rush to move to audio and video sources online, we’ve lost an opportunity. Our school library doesn’t have any DVDs or CDs, for example. Meanwhile, Netflix is blocked in our district (upon the request of Netflix, over public performance rights), as teachers we are not provided with access to online music resources that we haven’t subscribed to ourselves, and moreover streaming services have gotten into the habit of pulling content on a whim. We have no librarian-curated audio or video resources at all, in media where hard copies suddenly seem like the longer-lasting option.

In the end the biggest threat to a print reference section in my future library is more likely to be the need to allocate resources to fill out the gaps in the rest of the library, rather than the utility of the reference section on its own merits.

Sources:

Asselin, M., Branch, J.L., Berg, D. (2006) Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Canadian Association for School Libraries.

Riedling, Ann Marlow; and Houston, Cynthia. (2019) Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools and Tips (Fourth Edition). Libraries Unlimited.

0 notes

Text

Korea to Kentucky: 7000 Miles for the Freedom to Read

Here's the whole story of my 7000 mile journey from Korea to Kentucky to salute librarians and fight for the freedom to read. I even got to solve a mystery at the end!

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

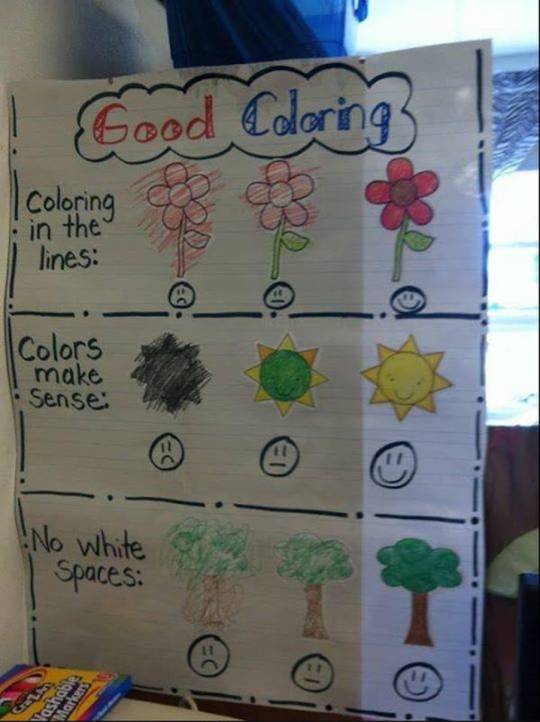

Once a little boy went to school.

One morning

The teacher said:

“Today we are going to make a picture.”

“Good!” thought the little boy.

He liked to make all kinds;

Lions and tigers,

Chickens and cows,

Trains and boats;

And he took out his box of crayons

And began to draw.

But the teacher said, “Wait!”

“It is not time to begin!”

And she waited until everyone looked ready.

“Now,” said the teacher,

“We are going to make flowers.”

“Good!” thought the little boy,

He liked to make beautiful ones

With his pink and orange and blue crayons.

But the teacher said “Wait!”

“And I will show you how.”

And it was red, with a green stem.

“There,” said the teacher,

“Now you may begin.”

The little boy looked at his teacher’s flower

Then he looked at his own flower.

He liked his flower better than the teacher’s

But he did not say this.

He just turned his paper over,

And made a flower like the teacher’s.

It was red, with a green stem.

On another day

The teacher said:

“Today we are going to make something with clay.”

“Good!” thought the little boy;

He liked clay.

He could make all kinds of things with clay:

Snakes and snowmen,

Elephants and mice,

Cars and trucks

And he began to pull and pinch

His ball of clay.

But the teacher said, “Wait!”

“It is not time to begin!”

And she waited until everyone looked ready.

“Now,” said the teacher,

“We are going to make a dish.”

“Good!” thought the little boy,

He liked to make dishes.

And he began to make some

That were all shapes and sizes.

But the teacher said “Wait!”

“And I will show you how.”

And she showed everyone how to make

One deep dish.

“There,” said the teacher,

“Now you may begin.”

The little boy looked at the teacher’s dish;

Then he looked at his own.

He liked his better than the teacher’s

But he did not say this.

He just rolled his clay into a big ball again

And made a dish like the teacher’s.

It was a deep dish.

And pretty soon

The little boy learned to wait,

And to watch

And to make things just like the teacher.

And pretty soon

He didn’t make things of his own anymore.

Then it happened

That the little boy and his family

Moved to another house,

In another city,

And the little boy

Had to go to another school.

The teacher said:

“Today we are going to make a picture.”

“Good!” thought the little boy.

And he waited for the teacher

To tell what to do.

But the teacher didn’t say anything.

She just walked around the room.

When she came to the little boy

She asked, “Don’t you want to make a picture?”

“Yes,” said the little boy.

“What are we going to make?”

“I don’t know until you make it,” said the teacher.

“How shall I make it?” asked the little boy.

“Why, anyway you like,” said the teacher.

“And any color?” asked the little boy.

“Any color,” said the teacher.

And he began to make a red flower with a green stem.

~Helen Buckley, The Little Boy

238K notes

·

View notes

Text

something my mum always taught us was to look for the resources we're entitled to, and use them. public land? know your access rights and responsibilities, go there and exercise them. libraries? go there and talk to librarians and read community notice boards, find out what other people are doing around you, ask questions, use the printers. public records offices? go in there, learn what they hold and what you can access, look at old maps, get your full birth certificate copied, check out the census from your neighbourhood a hundred years ago. are you entitled to social support? find out, take it, use it. does the local art college have facilities open to the public? go in, look around, check out their exhibit on ancient looms or whatever, shop in their campus art supply store. it applies online too, there is so much shit in the world that belongs to the public commons that you can access and use if you just take a minute to wonder what might exist!!!

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello. I'm expected to create a series of blog posts for the course I'm taking in the teacher librarian program. I have blogs. I've been blogging since before we'd settled on for sure using the word "blogging" for what this activity is (I remember being opposed, at the time, because "blog" is an ugly-sounding word, but language development is a collective effort and I was outvoted, so). But my other current blogs and social media are almost entirely about comics, or politics, or history, or some combination of all of those. I don't often blog about school or education, since I don't want to interact with any of my students or their parents online on my free time, and I certainly can't post about what happens day to day. That's not the world's business. But here you go, here is a blog about my impending teacher librarianship. There will be some posts here.

It's library time!

0 notes