Culture, politics and society in the words of Viviana Rizzo, Italian author and blogger.||Website: vivianarizzo.carrd.co||Twitter:p xVivianaRizzo||Instagram: the_white_of_butterflies||Her new book, "Make my hope eternal", is coming out in 8th March on Amazon.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Lenin's colonial question in Soviet history

How it shapes USSR–Sub-Saharan Africa relations

In Summer 1920, Moscow hosted the Second Congress of the Third International (Komintern), which continued the work of definition of the action policies of communist and socialist parties of all Europe (and beyond)[1]. It was in this context that, for the first time, the colonial question (Kolonialny Voproc, in Russian) in the Marxist discourse and the strategies toiling mass parties should have adopted towards national liberation movements in colonial countries were approached officially and systematically[2]. This question was introduced by the same Lenin through the Preliminary Draft Thesis on the National and the Colonial Questions (Pervonachalhy Naprosok Tezisov po Natsionalnomu i Kolonialnomu Voprosam, in Russian), which he made circulate among the international delegates a little less before the opening of the Second Congress, in order to generate a systematic debate on the issue related to the liberation of Eastern countries (which will have been finalised by the Third and Fourth Congress)[3].

In the Draft Thesis, Lenin proposed to offer a reflection on the problems in Eastern countries under imperialist dominion and tried to give an answer to how dealing with such issues and how to approach towards national liberation movement in those contexts that are typically feudal, where the bourgeois hadn’t raised yet, hence they didn’t reach a class system typical of capitalist societies. Fundamental and original in the Colonial Question as it was presented by the upholder of the October Revolution was the integration of the discourse on the East of the world in Marxist thought – established here as a subject[4] – and the introduction of the national question in the colonial one, which had been considered as two distinguished topics by Marx[5]. Such process led to the formulation of a Soviet theory on anti-colonialism[6], that had a central role in foreign policies of the Komintern and in the relations between Soviet Union and anti-colonial countries; moreover, the colonial question and the Draft Thesis had been the foundation to the rise of Soviet African Studies and of further debates on anti-colonialism in this context[7].

The Colonial and National Questions as proposed to the Komintern and object of debates was introduced by Lenin in the Draft Thesis, but finalised in the Report of the Commission of the National and the Colonial Questions (Doklad Komissi po Natsionalnomu i Kolonialnomu Voprosom, in Russian), produced by the debates on the East between Lenin and Roy, the Indian delegate. This question and these works can be considered as the result of previous reflections made by the same Lenin on Imperialism and on the relations between the East and Western powers, which imposed the colonial dominion on them[8].

The colonial question had already introduced by Marx and Marxist thought in general and several debates emerged during the First and the Second International, wherein the colonial dominion was defined as an extension of the power and exploitation perpetrated by the capitalism[9]; there, it was also clarified the necessity of socialist parties to pursue the «complete emancipation of colonies»[10] so that they could «claim for the natives that liberty and autonomy compatible with their state of development»[11], with a clear condemnation expressed by the Stuttgart Congress of the International in 1907[12]. But then, why was Lenin’s Colonial Question considered the foundation of the following anti-colonial debates in the Soviet context? Because «[…] what was being debated and decided were the attitudes European socialists should adopt towards the process of colonization and towards the colonial countries. For many, the non-Western world was still, as in Marx’s time, an object»[13]. In first Marxist theories, the discussion on the colonial dominion was focused on the approaches the socialist movement should have adopted, keeping aside the colonised countries and distinguishing the national question from the colonial one[14]. On the contrary, Lenin reformulated the Marxist thought on the East, putting it at the centre of the debate and giving it an active role, and not just compared to the West or as an incidental reflection to the great events of history[15]. In Imperialism: the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin described the imperialism as a tool of colonial and imperialist powers to expand their own authority and their sphere of influence[16], «characterised by intense competition, by a ‘striving for domination’»[17], and, in this context, the relationship between the West and the East became more and more complex, based on capital relations, and «colonies were important at every stage in the reproduction of capitalism. Not only or primarily as markets, but as sources of raw materials and as fields for the self-expansion of capital, as investment outlets»[18]; in this process, the East entered the orbit of capitalism, without becoming itself capitalist[19]. Imperialism is thus a new step of capitalism, which aims to the expansion of its own power and «which had divided the world into oppressor and oppressed nations»[20]; the colonial question, therefore, became also national, since «if imperialism meant a structural relationship of oppressor and oppressed it followed that any break in that structure was a blow, not only against a particular imperialist power, but against imperialism»[21] and, thus, every kind of struggle against imperialist dominion where colonies were integrated in capitalist system took shape as a struggle against capitalism and, consequently, considerable progressive and revolutionary[22]. «The colonial question came to be regarded as an ally of the proletarian revolution»[23]. Indeed, it was a duty for toiling masses of workers of oppressed nations to struggle for the right of self-determination of nations[24], i.e. the right to secession which must be acquired by the will of the population and through free votes[25], because it wouldn’t have been so, «the recognition of equal rights of nations and of the international society of workers would, in reality, remain an empty phrase, a mere hypocrisy»[26].

Already before the formulation of the imperialist theory Lenin was interested in the colonial question. In the struggle against the dominion of Western powers, he saw a new historical phase, which could have jeopardised the capitalist system as imposed, «characterised by heightened struggle, which began in Russia and Asia»[27], and had serious implications for the class struggle in Europe[28]. Even though national liberation movement from colonial dominion didn’t have all socialist characters, they took shape as revolutionary movements since they’re opposed against capitalist system, and thus, they could have been considered as a first phase of the path towards a socialist system[29]. «Colonial nationalism appears in Lenin’s theory as part of the one revolutionary process; it is a ‘step’ on the march to socialism»[30] and so that they could contribute to the long overdue global revolution, as desired by Lenin and bolsheviks in the aftermath of Russian revolution, which saw the fall of capitalist system and the triumph of the toiling mass of workers[31]. «”[T]he civil war of the working people against the imperialists and exploiters in all the advanced countries is beginning to be combined with national wars against international imperialism”»[32].

Such interest, therefore, derived from the necessity of promoting the socialist revolution and Soviet Russia, in order to assure the socialist victory in a moment of great uncertainty in the aftermath of the civil war and of a major crisis provoked by the Great War[33]. Since he didn’t find support from Western powers, the «Lenin sought popularity among the small and weak states of Europe as well as the colonies by exposing the methods adopted by then great powers to promote their interests at the expense of the small states»[34]. From this the urgency to systematise the colonial question and the approaches towards national movements of liberation.

The Preliminary Draft Thesis on Colonial and National Questions were Lenin’s formulations on the approaches Communist parties and toiling mass movement should apply in the context of anti-colonial struggle. Here, Lenin stated that the duty of the Communist International was to make an alliance with the proletarians of all nations «to overthrow the landowners and bourgeoisie»[35] because only a proletarian revolution and the victory of the Soviet power could liberate the peoples oppressed by colonial dominance[36]. Specifically, communist parties had to collaborate temporarily with national liberation movements in whatever expression they assume, democratic-bourgeois as well[37], in the context of imperialist regime, where the capitalist system typical of Western nations hadn’t developed yet, but rather they showed feudal or patriarchal characteristics[38], without emerging with them though[39]. Thus, it was necessary that the anti-imperialist struggle policies wouldn’t be built on abstract concepts[40], instead they «should first be based on an exact appraisal of specific historical and above all economic conditions»[41], being aware that what one was fighting for were really the needs of oppressed social classes, and not those of the classes in power which support, for the purpose of their interests, the perpetration of the system of dominance by capitalist nations[42], distinguishing «between the interests of the oppressor and oppressed»[43]. Moreover, communist parties had to expose how the colonial powers imposed their dominance, «creating a stage structure that is dependent economically, politically and militarily upon the imperialist powers»[44], and these parties «must give care to the survivals of national feelings un the long-enslaved countries and peoples»[45], in order to create an alliance between the proletarians of all the world[46] and ensure the victory of Soviet system[47].

In the strategies as introduced by Lenin results a critical issue which was useful for the rising of the following debates regarding the colonial question. This critical issue was the the necessity of communist parties to create an alliance with democratic-bourgeois movements for liberation of nations in those colonial countries where there was no class consciousness. Debates on such issue had already raised before the publication of Lenin’s Thesis, because he made circulate the text among the international delegations before the presentation to the Congress[48], and specifically among those who had already had experience in colonial contexts, such as Manabendra Nath Roy, the Indian delegate, who was fundamental for the development of colonial and national questions. Roy, taking India as an example, pointed out the reactionary nature of some democratic-bourgeois movements[49] and the interests of the latter in establishing regimes which didn’t free nation from the colonial yoke or didn’t take action in the interests of the oppressed peoples, but collaborated with the foreign powers to perpetrate the same relations of power of colonial context, to further their own interests and to establish a capitalist system in their nation, now free from a patriarchal or feudal regime[50]. «He refused to accept that the national bourgeoisie was playing a historically revolutionary role in the liberation struggle»[51] because «[…] the nationalist movement was ideologically reactionary in the sense that its triumph would not necessarily mean a bourgeois-democratic revolution»[52]. Moreover, Roy highlighted that the proletariat was already established and mature also in those contexts, so that there were no reasons for an alliance with democratic-bourgeois movements, especially if they may not have had progressive and revolutionary characteristics, but reactionary instead[53]. Thus, it was necessary encouraging a mass action lead by communism parties, so that a real revolutionary force able to establish the Soviet power would rise[54]. In this regard, Roy produced additional thesis for the Congress. There, he asserted that in colonial context emerged two different movements: a nationalist democratic-bourgeoisie movements – which aims to the establishment of a bourgeoise regime – and the mass of working people and peasants; between the two, there was a relationship where the former oppressed the latter. It was useful, Roy asserted, working together with revolutionary democratic-bourgeoise movements, but only if communists parties coordinate and lead the mass of workers and peasants towards the revolution and help to develop the class consciousness, although being aware that revolution, in an initial phase, couldn’t be communist[55], because «[t]he combination of Military oppression by foreign imperialism of capitalist exploitation by the native and the foreign bourgeoisie, and the survival of the feudal servitude creates favourable conditions for the young proletariat of the colonies to develop rapidly and to take its place at the head of the revolutionary peasant movement»[56].

The reason why Lenin didn’t consider that such movements could assume reactionary character can be found in his view on history as evolutionary process, as it was described by the Marxist ideology[57], «where was politically desirable was also found to be consonant with historical progress and was ’progressive’ in this double sense with each notion of progress (the political and the historical/evolutionary) underwriting the other»[58]. Also the colonial question is included in this process, where the imperialist phase and colonial nationalism appear as a step towards the main goal, i.e. socialism[59], but without taking into account if this step result more like a stopping point and «that national liberation in the colonies […] might be resistant to further ‘progress’»[60].

Taking in consideration and embracing Roy’s thesis[61], i.e. democratic-bourgeois movement were not always revolutionary and progressivist, but reactionary as well, Lenin reviewed the content of the Draft Thesis, whose changes he justified in the Report of the Commission on the National and the Colonial Questions, a work he disclosed to the Second Congress. First of all, in this last, Lenin asserted he recognised the nationalist and reactionary characteristics that liberation movements could exhibit, and thus, he decided to substitute the expression “democratic-bourgeois movement” (burzhuaznoe-demokraticheskoe dvizhenie, in Russian) with “national-revolutionary movement” (natsionalnoe-revolyutsionnoe dvizhenie, in Russian)[62], because in colonial nations all national liberation movements are democratic-bourgeois, since «the overwhelming mass of the population in the backward countries consists of peasants who represented bourgeoise capitalist relationship»[63]. This specification was due to the reason that communist parties could support such movements only when they show themselves as really revolutionary[64]. Moreover, Lenin asserted that, as the Indian experience showed, it was possible to inspire an independent political thought also in feudal and semi-feudal countries, where the proletariat lacked[65], and that «peasants […] can easily assimilate and give effect to the idea of Soviet organisation»[66], which is applicable in any context[67], without passing through the capitalism phase[68].

Another interesting review is the explication of the differences between oppressed and oppressor nations (ugnetennye i ugnetayushchie natsii, in Russian), in order to establish «the concrete economic facts and to proceed from concrete realities»[69]. According to Lenin, oppressor countries are those which own «colossal wealth and powerful armed forces»[70], while he meant for oppressed countries those nations that «are either in a stage of direct colonial dependence or are semi-colonies […], or else, conquered by some big imperialist power, have become greatly dependent on that power by virtue of peace treaties»[71].

However, the Fifth Congress rejected Lenin’s thesis on an alliance between communists and national liberation movements[72], despite the reviews Lenin made. Moreover, those who advocated for colonial reforms, rather than the revolution, were silenced of being «national reformist[s]. Soon, those who […] supported anti-colonial revolutions, but not under the banners of the Comintern, were denounced as […] “Trotskvists”»[73], as it was established by the new Soviet leadership, that also rejected the hypothesis of a temporary alliance with democratic-bourgeois movements in colonial nations. Indeed, in Marxism and the National Question already, written before the October Revolution, Stalin (Party Secretary from 1922), had supported the idea that «the proletariat does not support the so called “national-liberation” movements because now all such movements because […] have acted in the interests of the bourgeoisie»[74]. A position that remained as such, and in The International Nature of the October Revolution Stalin emphasised the pivotal and hegemonic role of proletarians in the liberation process, rejecting Lenin’s approach[75]; a rejection that conditioned the Komintern, which, during the Fifth Congress, adopted with a resolution the decision that communist parties should have obtain the support from peasants and oppressed minorities in order to «make them the allies of the revolutionary proletariat of the capitalist countries»[76], whose strategies and exceptions must have been applied depending the conditions of the social and economic system of the nation where the communists wanted to take action in[77]. It’s important to highlight that Stalin, regarding foreign policy, assumed an attitude of closure towards European communist parties and socialist movements. Indeed, «Stalinism required that Communist parties everywhere be parties of a truly new kind with their loyalties due exclusively to Moscow»[78]. The Soviet foreign affair as established by Stalin opened with the rise of fascists parties[79], when the Komintern «directed the communist parties to work for a United Front with social democrats against fascism»[80]. A fundamental decision for the anti-colonial struggle, because communist parties could ally with national liberation movements again, with the purpose of supporting the anti-imperialist struggle and the battle against every Soviet Union’s enemy[81]. This meant the recollection of Leninist thought about Colonial and National Questions, which continued during the post-Stalin era.

If, after the end of the Second World War and the rising of tension between USSR and Western nations, the Komintern and Stalin returned to a closure policy, an about-turn was made by Nikita Khrushchëv, with whom started the Thaw era (Ottepel, in Russian), i.e. an easing in policies of ideological surveillance and an opening toward Western powers. This distancing from Stalinism was also a consequence of 22nd Congress of Communist Party, where the new Party Secretary reported Stalin’s personality cult and Stalinist terror. Moreover, in this context was raising the phenomenon of non-aligned nations, and «Khrushchev began a policy of assiduously courting [them]»[82], in order to create an alliance between these nations and Moscow and gain trust from them towards Soviet Union. A new approach on the colonial question, nevertheless, was adopted, according to which communist and socialist parties should have allied, in order to win over the imperial system and establish a socialist regime, through either armed conflict or non-violent methods[83]. These kinds of policies influenced the relations between Soviet Union and the new nations born from anti-colonial struggle. Many of them adopted socialism, while other ones strengthened their cooperations with the USSR[84]. The result of this was the rise of the concept of national democratic state during the World Conference of Communist Parties in 1960[85], according to which

A national democratic state is one which consistently defends its political and economic independence, struggled against imperialism and its military blocs, against military bases on its territory against new forms of colonialism and the perpetration of imperialist capital, rejects dictatorial and despotic methods of government, and assures to its people abroad democratic rights and freedoms and the opportunity to wok for agrarian reforms and partecipar in the determination of state policy[86].

Also in Sub-Saharan Africa were emerging nations with these characteristics, such as Mali, Guinea, Ghana, where, actually, there were no communist parties[87] (although Ghana was in a good relationship with the Soviet Union)[88].

The USSR started to show an interest in these new nations; indeed, in a report for the 23rd Congress of the Communist Party, Leonid Brezhnev (succeeded Krushchëv as Party Secretary) emphasised the social transformations that were affecting ex-colonial countries, among which Mali, Ghana, Congo and Buma[89]. The close relations with these nation-democratic states was stressed with an article published by the Izvestia, where these nations were defended, because they «are closely linked with the struggles against colonialism and imperialism, and are lead by revolutionary-democratic figures»[90] and they were actively cooperating with the USSR to protect themselves from the attempt of the US to establish a system of economic imperialist dominance there. This cooperation was confirmed by the presence of many delegation from Sub-Saharan Africa in the 23rd Congress of the Communist Party, and when Brezhnev designed the democratic parties of these nations as revolutionary democratic parties in June 1969[91].

Lenin’s Colonial and National Questions had a great impact on the relations between USSR and new nations raised from anti-colonial struggles. Among these, many Sub-Sharan countries, which started arouse interest especially during the decolonial phase. The theoretical basis of Soviet theory on anti-colonialism and the international relations with these countries had an important role in the development of African Studies in Soviet context too[92].

The interest of the Soviet Union towards these nations was born in 20s, with the participation of the communist party of South Africa to the Third International, which followed the creation of an Independent Native Republic there during the Sixth Congress of the Komintern in 1928; this event put the focus on the issues of South Africa and, consequently, of the whole continent[93]. At that time, the Africanist in Soviet Union were few, and fewer those who were expert on the colonial question; among these, we remember Endre Sik, Ivan Izosimovich, Ivan Potekhin-Man and Alexandr Zakharovich[94]. Sik, from the first meeting of African students, undisclosed a first programme for the study of Africa, where anti-colonialism had a pivotal role, that found as theoretical basis the Lenin’s approach[95]. The Hungarian Africanist emphasised the urgency to take more into consideration these issues, «[…] because in the colonial people of Black Africa, who are more exploited and oppressed than any other, we have potential allies in our struggle against the imperialist system»[96]. The same approach was to find in Potekhin and Zusmanovich’s studies, which, in The Labour Movement and Forced Labour in Negro Africa, described, for the first time in the Soviet context, the economic system of Sub-Saharan African, giving ample space to those problematics related to the exploitation of these lands perpetrated by imperialist powers[97], for which the authors adopted the concept of two-phase revolution, according to that the first phase of revolution was constituted by «the struggle for the land and the war for national liberation»[98], while the second occurred «through gradual transformation of this agrarian-nationalist, bourgeois-democratic revolution into socialist revolution»[99]. Regarding these studies, it was necessary to highlight the ideological character, based on socialism, which undermined the scientific nature of these researches[100]. Moreover, these studies weren’t carried out without field work[101].

The era of Stalinist terror slowed down the development of African studies (despite the innovations, original in Western countries) and of the relationship between Sub-Saharan Africa and USSR. The vision that Africanists expressed «were completely subordinated to the ideological dogma and political directives of the Komintern»[102], and consequently, what they wrote resulted to be, more than studies, guidelines for Communist parties and other progressivist forces which took action in the African continent. This tendency seemed to be continued also in the Thaw era and during the years of anti-colonial struggles, although the study produced in this context resulted original and innovative. Africanists’ researches focused more on the «phenomenon of independence as one colony after another changed its status»[103] then, as it was Zhukov’s study, because, during the decolonisation process, it was necessary that the Komintern was led on how to deal with these changes and how to appear as an ally, in order to impose itself in the international relations these countries intended to build[104]. The role of proletarians in national liberation movement didn’t seem to be off the radar of these studies, as it was established by Stalin earlier. The success of these movements was due to the central role of the proletarians[105] , while national bourgeois movements resulted to be the reasons behind the social divisions in the colonial context[106]. A position that remained such also after the experience of United Fronts and after the resolution of the Seventh Congress of the Komintern[107], as these movements were still considered «active accompliance of imperialist monopolies […] suppressors of the oppressed peoples[108], even during Gorbachëv’s Perestroika, when Soviet foreign policy changed positions[109].

Reference

[1] BARTLETT, Roger, Storia della Russia. Dalle origini agli anni di Putin, Milano, Mondandori, 2007, p. 280

[2] AA.VV., The Communist International 1919-1943. Documents, Jane Degras (edited by), p. 383

[3] MAITRA, K., “Lenin and Roy on National and Colonial Question at the Second Congress of the Third International”, in Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 37 (1976), p. 500

[4] SETH, Sanjay, “Lenin’s Reformulation of Marxism: the Colonial Question as a National Question”, in History of Political Thought, 13/1 (Spring 1992), p. 120

[5] ivi, p. 122

[6] FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), in AA.VV., The Study of Africa. Volume 2: Global and Transnational Engagements, Paul Tiyambe Zeleza (edited by), Dakar, Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA), 2006, p. 204

[7] Ivi, p. 203

[8] SETH, Sanjay, “Lenin’s Reformulation of Marxism: the Colonial Question as a National Question”, p. 122

[9] Ivi, p. 110

[10] Ibidem

[11] Ibidem

[12] ibidem

[13] Ibidem

[14] ivi, p. 122

[15] ivi, p. 114

[16] ivi, p. 115

[17] Ibidem

[18] Ibidem

[19] ivi, p. 116

[20] ivi, p. 119

[21] Ibidem

[22] ivi, p. 120

[23] ivi, p. 122

[24] AGRAWAL, N. N., “Lenin on National and Colonial Questions”, in The Indian Journal of Political Science, 17/3 (July-September 1956), p. 236

[25] SETH, Sanjay, “Lenin’s Reformulation of Marxism: the Colonial Question as a National Question”, p. 233

[26] Ivi, p. 236

[27] ivi, p. 112

[28] Ibidem

[29] ivi, p. 125

[30] Ibidem

[31] Lenin on Foreign Policy of the Soviet State, Moskva, Progress Publisher, 1968, p. 163, in SURENDAR, T., “Ideology and Soviet Policy Towards Colonial and Ex-Colonial States with Special Reference to India 1917-1971”, in India Quarterly, 48/3 (July-September 1992), p. 32

[32] SURENDAR, T., “Ideology and Soviet Policy Towards Colonial and Ex-Colonial States with Special Reference to India 1917-1971”, p. 31

[33] ibidem

[34] ibidem

[35] LENIN, N., “Preliminary Draft Thesis on National and Colonial Questions”, in Lenin’s Collected Works. Volume 31 April – December 1920, (trans. En. by Julius Katzer), Moskva, Progress Publisher, 1974 (2nd Edition), p. 146

[36] ibidem

[37] Ibidem

[38] ivi, p. 149

[39] ivi, p. 150

[40] ivi, p. 145

[41] ibidem

[42] ibidem

[43] ivi, p. 150

[44] ivi, p. 151

[45] Ibidem

[46] ibidem

[47] ivi, p. 146

[48] MAITRA, K., “Lenin and Roy on National and Colonial Question at the Second Congress of the Third International”, p. 500

[49] ivi, p. 501

[50] ivi, p. 502

[51] ivi, p. 501

[52] ibidem

[53] ibidem

[54] ivi, p. 502

[55] SURENDAR, T., “Ideology and Soviet Policy Towards Colonial and Ex-Colonial States with Special Reference to India 1917-1971”, p. 34

[56] ivi, p. 36

[57] AGRAWAL, N. N., “Lenin on National and Colonial Questions”, in The Indian Journal of Political Science, 17/3 (July-September 1956), p. 123-124

[58] ivi, p. 124

[59] ivi, p. 125

[60] ibidem

[61] LENIN, N., “Report on the Commission on the National and the Colonial Questions”, in Lenin’s Collected Works. Volume 31 April – December 1920, p. 240

[62] Ibidem

[63] ivi, p. 241

[64] ivi, p. 242

[65] ivi, p. 243

[66] Ibidem

[67] Ibidem

[68] Ivi, p. 244

[69] ivi, p. 240

[70] ibidem

[71] ivi p. 240-241

[72] FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 205

[73] Ibidem

[74] ivi, p. 206

[75] ibidem

[76] SURENDAR, T., “Ideology and Soviet Policy Towards Colonial and Ex-Colonial States with Special Reference to India 1917-1971”, p. 39

[77] ivi, p. 40

[78] ivi, p. 42

[79] ivi, p. 43

[80] ivi, p. 44

[81] Ibidem

[82] ivi, p. 52

[83] Ibidem

[84] ivi, p. 55

[85] Ibidem

[86] ivi, pp. 55-56

[87] ivi, p. 56

[88] TELEPNEVA, Natalia, “The Mediators of Liberation: Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Bureaucratic elite, and the Cold War in Africa”, in Cold War Liberation. The Soviet Union and the Collapse of the Portuguese Empire in Africa 1961-1975, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina, 2021, p. 15

[89] SURENDAR, T., “Ideology and Soviet Policy Towards Colonial and Ex-Colonial States with Special Reference to India 1917-1971”, p. 56

[90] ivi, p. 57

[91] Ibidem

[92] FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 204

[93] ivi, p. 206

[94] Ibidem

[95] ivi, p. 207

[96] SIK, Andre, “K postanovke marksistiskogo izucheniia sotsialno-ekonomicheskikh problem Chernoi Afriki”, in Revolutsionnyi Vostok 8, Pppp 88-89, in FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 208

[97] FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 210

[98] ZUSMANOVICH, Aleksandr Z., POTEKHIN-MAN, Ivan I. & JACKOSN Tom, Prinuditelny trud I profdvizheniie v negritianskoi Afrike, Moskva, 1933, pp. 165-166, in FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 211

[99] Ibidem

[100] FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 216

[101] ivi, pp. 216-217

[102] Ivi, p. 216

[103] ivi, p. 220

[104] Ibidem

[105] Ivi, p. 221

[106] ibidem

[107] ivi, p. 222

[108]MASLENNIKOV, V. A., Uglubleniie krizisa kolonialnoi sistemy imperializma, Moskva, 1952, p.. 44, in FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 222

[109] FILATOVA, Irina, “Anti-Colonialism in Soviet African Studies (1929s-1960), p. 222

#writing#blogging#politics#article#culture#soviet union#sub saharan africa#colonial history#colonial question#vladimir lenin

0 notes

Text

Two stories, one world: The Nutcracker

Originally posted on The Moving Lips

The Christmas imaginary, the holiday, celebrations inspired the greatest European authors since the origin of modenrity, from Nikolay Gogol’, Charles Dickens, Boris Pasternak, Alexandre Dumas pére, becoming each time an opportunity to develop the topics of national folklore in a Christian point of view, or to explore the creative mind in the lens of childhood or through the beauty of brief moments of joy, or even becoming an occasion to critique or describing the social context of a given historical period, narrating the fate of a people, of a certain individual.

How many of us book lovers lose ourselves in Gogol’s irreverent worlds with “The Night Before Christmas”, or travelled in the Christmas of our childhood, present and future together with Scrooge, the main character of “A Christmas Carol”, or even thanks to a timeless tale such as “The Nutcracker”, immortalised by the opera of the great Russian musician, Pëtr I. Chaykovsky. “The Nutcracker” had made thousand and thousand of children dream all over the world and given us magic moments for our Christmas, but this beautiful and apparently simple tale hides a complexity which collects History and the collective imaginary of whole generations, because “The Nutcracker” is not just a Christmas story for children.

The original story, titled “Nutcracker and Mouse King” (Nußknacker und Mausekönig) is a novel by E.T.A Hoffmann, written in 1816, during the Romanticism era, and, indeed, many topics of this literary movements are contained in this tale; nevertheless, the story as it’s known by most readers, and used for the well-known ballet put to music by Chaykovsky, is the one told by the version edited by Alexander Dumas pére in 1844, in Positivist era, titled as “The Tale of the Nutcracker” (Histoire d’un casse-noisette). More edulcorated and detailed is the Dumas’s version, more intimistic and crueler is the one written of Hoffmann, these two works, although similar in the plot, show complex ideological differences, given the different historical contexts. Hoffmann takes the Romantic literary tendencies to tell Nutcracker’s story, this toy hero who challenges the evil forces symbolised by the Mouse King, firstly by not hesitating a more intimate vision of the story, describing Christmas atmosphere in a symbolic way, almost like he wanted to imitate children’s gaze, that «[v]iewed from the perspective of the three children, the Christmas tree is magic, and the events feel them with wonder and terror»[1]. Here, moreover, starting from the tradition begun by Hegel’s “The Phenomenology of the Spirit”, he built the structure of the book on the dualism of the identity of the object (i.e. the mind becoming the object of observation), subject and the thematic of the double.

More detailed and realistic, as positivist tradition ruled, is Dumas’s version, that put on the foreground not the individual, but family and society, moving from a magic imaginary of Christmas to social aspects, describing habits and traditions. The story is projected to the world, denying the existence of the “spirit”; «[u]nlike the Hoffmann story, where everything is part of everything else, Dumas disengages himself from the story (also through the distancing “Once upon a time” opening formula), destroying its credibility, and transforming it into a realist type of narrative with detailed portraits of the characters, on which he passes judgement like an omniscient narrator»[2].

This relation with reality by connecting to the outer and to those historic events which inflamed Europe during 19th Century is one of the elements that makes this tale so unique, so appreciated by both children and adults. “The Nucracker” is a universal story, able to adapt to every historical period, and being always modern in its message; it’s a story that mediates between cultures and makes them connect to each other. It was born in Germany, then it moved to France, change language, and got to Russia, where it became one of the most touching classical ballet, to reach the whole Europe, being part of the fabric of this fragmented, complex, and variegated culture-continent, and going beyond. A world becoming the Konfektburg, the Candyland, in “The Nutcracker”, where different peoples – Greeks, Armenians, Tyrolese – lived together peacefully, where social classes are mixed, discuss and respect each other, where Europe and Asia can communicate in a time when it was not possible yet, when China was still closed within its borders, and Greeks and Armenians were fighting for their independence from the Ottoman Empire. A world in peace and united, an utopia dreamed by Marie, the main character, and everyone, in the innocence of childhood, dreamed that it could be exist. A fictional world, but where still the battle which most characterised the collective and cultural imaginary of humanity, which shaped myths and the knowledge of the world, which made us humans: the one which sees the forces of good fights the evils ones. The good, the Nutcracker, the general, the warrior who sacrificed himself, and the evil, the Mouse King, a nearly apocalyptic creature, a monster with seven heads of serpent, who’s firstly stopped by Marie, that received his crown, – who is the mean between the world of toys and the real one –, and then defeated by the Nutcracker, freeing himself from the malediction.

The Nutcracker symbolises the values of Christmas, i.e. communion, altruism, bravery, a united people, the victory of the good on the evil, the beauty of a world that only children (and artists) can see through the ugliness of this disappointing reality.

Note

1. BARNA, C. R. (2018). Experiments in Pattern Recognition Case study: The Nutcracker. International Journal of Arts and Commerce, Vol. 7 No. 5, p. 42

2. Ivi, p. 43

#the nutcracker#e. t. a. hoffmann#Alexandr Dumas pére#christmas#writing#blogging#literature#politics#article

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Baldwin: «history is literally present in all that we do»

History is not something that exist, something that one can consult, but it’s the question we keep inside ourselves; it’s not something that defines us a priori, but a description we choose for ourselves.

History intende as past is a crystallising of our being to find something that looks like us, to not to deal with the vertigo of the future, to not to fight with our own evilness, to deal with.

James Baldwin wrote that «[…] history is literally present in all that we do. It could scarcely be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations. And it is with great pain and terror that one begins to realize this»[1]. History is, thus, a further tools we can use to give meaning to our existence, a point of view among other points of views that run into and clash between each other. History’s a tale we can still change, and it’s still possible to free the world from that heavy curtain which is racism, but only if we’re brave enough to face our past, not to make it the descriptor of our present, but only a little part, only if we’re brave enough to deal with our evilness, and abandon the fetish of a past that oppressed and to accept that past looks like us very little, that history is our present, something we preserve.

This must be learned by Black people, so that they can tell a different story, to convince themselves their last is not their doom, to learn how to use their history as a tool. «Something more radical had to be done; a different history had to be told. “All that can save you now is your confrontation with your own history […] which is not your past, but your present,” Baldwin said. “Your history has led you to this moment, and you can only begin to change yourself by looking at what you are doing in the name of your history.”»[2]

This must be learned by white people in order to free themselves from their guilt, because «[t]he fact that [the white people] have not yet been able to do this--to face their history to change their lives--hideously menaces this country. Indeed, it menaces the entire world»[3]. The white man’s burden is not, as Kipling wrote, to bring civilisation, i.e. to impose an Eurocentric vision of the world, to distant communities, but it’s history, as Baldwin wrote; or better, it’s the burden to have sewn the heavy curtain of race around themselves to divide “we” from “they”, as if these differences existed and they weren’t a way to keep their power, to never put themselves in discussion[?]. And how to face own history if this means to doubt own position, an identity built to the detriment of other?

To understand what history means is to change world.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Reference

1. BALDWIN, James, “The White Man’s Guilt”, in Collected Essay, New York, The Library of America, 1998, p. 723

2. GLAUDE Jr., Eddie S., “The history that James Baldwin wanted America to see”, in The New Yorker, web, 19.06.2020 (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-history-that-james-baldwin-wanted-america-to-see)

3. BALDWIN, James, “The White Man’s Guilt”, p. 722

Source

1. ALS, Hilton, “The Enemy Within. The making and unmaking of James Baldwin”, in The New Yorker, web, 9.02.1998 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/02/16/the-enemy-within-hilton-als)

2. BALDWIN, James, “The White Man’s Guilt”, in Collected Essay, New York, The Library of America, 1998

3. BALDWIN, James, “Letter from a region in my mind”, in The New Yorker, web, 9.11.1962 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1962/11/17/letter-from-a-region-in-my-mind)

4. GLAUDE Jr., Eddie S., “The history that James Baldwin wanted America to see”, in The New Yorker, web, 19.06.2020 (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-history-that-james-baldwin-wanted-america-to-see)

#James Baldwin#black history month#black lives matter#writing#blogging#history#identity#memory#culture#article#politics#literature

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toni Morrison: «Memory meant recollecting the told story», II part

Magic as cultural device for the construction of collective memory

The recollection of West African tradition and the addition of elements inside the narration are another way to build the collective memory, where the African culture becomes a common ground in which sharing meanings, and also an instrument of resistance against dehumanisation. As the slave-owning people tried to deny the humanity of Black people, the latter communicated, resisted and strengthened each others maintaining the practice of their culture. This recovery, as orality in Toni Morrison’s works, is translated also as the addition of magical or supernatural elements of African cultures; «Morrison seeks to address this insecurity by creating an African American cultural memory with her readership through mutual acts of the imagination. In order to achieve this her writing encourages the imaginative participation of the reader in the text through oral storytelling techniques and, despite Morrison's disclaimer, through magic realist devices»[8]. The magic element is connected to the oral tradition to which Morrison referred, because both orality and the supernatural element represent modalities of transmission of her tradition; indeed, «Morrison's two most notable novels, Beloved (1987) and Song of Solomon (1977), both contain magic realist elements which can be traced to African American myth and both novels focus on the importance of the role of memory in oral tradition to perpetuate African American culture»[9].

In particular, ghost stories and the image of the revenant, both present in oral African tradition and recovered by the Afroamerican one, are more relevant in Morrison’s works and these elements are the ones that collect that sense of connection with the past, the relations between being here and now and memory, a process that creates the collective identity from that history shared by the individuals, by the personal experiences to the common destiny of a collectivity. This happens in her most notable novel, Beloved, where the young girl murdered by her mother comes back as a ghost, as a revenant, a spectre from the past and recollection of memory, of traumas, the personal and shared ones. The tragedy of death, of negation of the self, the horror of slavery and of dehumanisation. «The use of a revenant for this story set during the specific historical period of the end of slavery and the reconstruction era is especially poignant. Eugene Genovese notes that during slavery ghost stories were prevalent on plantations and was one way in which elements of African tradition were retained»[10]. The magic element, and in particular ghost stories, has got a double role in the recovery of cultural issues, i.e. the reversal of coercive elements and the reappropriation of cultural images that were confiscated by owning-slave individuals to culturally oppress slaves. «As Fry explains, one means of control over slaves was for the master to create and spread a ghost story set in an area that was difficult to patrol […]. Through this method the master attempted to increase his control over the slaves by appropriating the transmutable force of a ghostly presence»[11]. Also in Toni Morrison, memory becomes a way to resiste culturally and to affirms the personal identity, as well as liberation from the hegemony perpetrated by white people and from oppression, using the alternative cultural reference and recollect those which were transformed into an instrument of control. Indeed, «the use of a ghost in Beloved – whose ultimate effect in the novel is to draw a community together for self-healing and protection - can be seen as a creative act of resistance to such attempts at control in slave history whilst appropriating the very power associated with ghosts for subversive purposes»[12]. But not only this. The use of ghosts in Beloved has also a negative quality, and so not just this of recovery. The ghost can be defined also as a threatening and negative figure, able to bring chaos, fear and division in the community; it’s the image of a dead that is back, the trauma that comes back to haunt. «Morrison establishes Beloved as a ghost in specifically African American terms and in doing so she brings the symbolism associated with the Ku Klux Klan into a familiar realm where it may be controlled»[13]. The reference to Ku Klux Klan means also the return of a violent past, of oppression, of discrimination. The history of slavery coming back to haunt, to scare and the racism of a certain political wing, racist declarations and action return. And recollect certain images, make them inoffensive, is a way to resist, an example of social response, whose purpose is to heal the trauma of an entire community, which is still dealing with the ghosts of the past. In Beloved, the ghost is «the past, and that part of the past which she represents is the internalised selfhatred by African Americans due to persistent racism against them. Sethe's coming to terms with her past is in part a coming to terms with her own self-hatred which she insists that Denver avoids»[14].

From the piece to the wholeness: memory as a creative process

«Memory, then, no matter how small the piece remembered, demands my respect, my attention, and my trust. I depend heavily on the rude of memory […] because it ignites me some process of invention»[15].

Toni Morrison, Memory, Creation and Writing

We’re almost at the conclusion, with another aspect of memory in Toni Morrison’s work, as it was unveiled by her in the magnificent essay Memory, Creation and Writing, about the memory as a creative process. It’s the memory itself, a fragment of reality showing up in the consciousness, a drop of reality, a revived moment, the perception of something that had been which trigger the creative language of Toni Morrison, that creates narrations, stories, characters she tells about in her books. A fragment to create the wholeness, one memory, or better, what this memory brings in mind emotionally. «The pieces (and only the pieces) are what begin the creative process. And the process by which the recollections of these pieces coalesce into a part (and knowing the difference between a piece and a part) is creation»[16]. This makes clear how much permeated is memory in her works, because this one is the origin of creation, but also what gives meaning to the story, what confers a common sense, signifies and orders the world. It means give a sense. A sense to life, to the past, to the horror, to trauma. It means order the present. And giving a meaning is to connect, as Toni Morrison connects pieces, memories, to create the wholeness, a picture that has a sign, that creates a pairing of figured to make it a different, unique one, transformed in it wholeness. It’s the narration that «is one of the ways in which knowledge is organized […] the most important way to transmit and receive knowledge»[17]. Memory is transmission, is the recovery of identities, is to call ourselves, recognising the Other, what has never been, because last is a lesson, is the path that lead us here and it’s the events that shaped us, and only remembering we can give a meaning to what we will remember. Thus, memory means to tell, is an epiphanic process, of realisation, that provokes the creation of a image. And it’s from this that Toni Morrison creates, because «memory meant recollecting the told story»[18].

First part here

Viviana Rizzo @livethinking

Reference

1. DAVIS, Christina, “Interview with Toni Morrison”, in Présence Africaine, 1er trimestre 1988, no. 145, p. 143

2. MORRISON, Toni, “The Site of Memory”, in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, Boston, Ed. William Zinsser, 1995 (2nd edition), p. 92

3. DAVIS, Christina, “Interview with Toni Morrison”, p. 143

4. NISHIKAWA, Kinohi, “Morrison’s Things: Between History and Memory”, in Arcade. Literature, the Humanities & the World, web, arcade.stanford.edu, 2021 (https://arcade.stanford.edu/content/morrison’s-things-between-history-and-memory)

5. LANIER, Adrienne & TALLY, Justine “Toni Morrison, Memory and Meaning”, in miscelánea: a journal of English and American studies, 52 (2015), p. 155

6. ONG, J. Walter, Orality and Literacy. The Technologizing of the Word, New York, Routledge, 2002, pp. 133-134

7. BOWERS, Maggie A., “Acknowledging ambivalence: The creation of communal memory in the writing of Toni Morrison”, in Wasafiri 13:27(1998), p. 21

8. Ivi, p. 19

9. Ibidem

10. Ivi, p. 21

11. Ivi, p. 22

12. Ibidem

13. Ibidem

14. Ibidem

15. MORRISON, Toni, “Memory, Creation, and Writing”, in Thoughts, vol. 59, no. 235 (December 1984), p. 386

16. Ibidem

17. Ivi, p. 388

18. Ivi, p. 389

Sources

1. BOWERS, Maggie Ann, “Acknowledging ambivalence: The creation of communal memory in the writing of Toni Morrison”, in Wasafiri, 13:17 (1998), pp. 19-23

2. DAVIS, Christina, “Interview with Toni Morrison”, in Présence Africaine, n. 145 (1st trimester 1988), pp. 141-150

3. MORRISON, Toni

“Memory, Creation and Writing”, in Thought, 59/235 (December 1984), pp. 385-390

“The Site of Memory”, in Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, Boston, ed. William Zinsser, 1995 (2ª edition), pp. 83-102

4. NISHIKAWA, Kinohi, “Morrison’s Things: Between History and Memory”, in Arcade. Literature, the Humanities & the World, arcade.stanford.edu, web, 2021 (https://arcade.stanford.edu/content/morrison’s-things-between-history-and-memory)

5. ONG, J. Walter, Orality and Literacy. The Technologizing of the Word, New York, Routledge, 2002, pp. 133-134

6. SEWARD Adrienne Lanier & TALLY Justine, “Toni Morrison, Memory and Meaning”, in miscelánea: a journal of English and American studies, 52 (2015), pp. 155-158

#Toni morrison#memory#beloved#song of Solomon#orality#identity#ghost stories#revenant#magic realism#magic#magic elements#African cultura#Afroamerican culture#Black culture#Black art#black history month#black lives matter

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toni Morrison: «Memory meant recollecting the told story», I part

Memory is an extraordinary instrument, capable of connecting individualities, the personal characters, the subjective experience of things, to link what has been, to what has faded to what has still no existence, is a potential act, what could be. Memory shapes identities, people’s characters, the perceptions of the Other and of things. Memory is an act of personal resistance, that is the creation of cultural value that are not collective or shareable, is a processo of building the person and society. And it’s in this sense that Toni Morrison calls memory to herself, makes it a narrative instrument, a collection of fragments which are not linguistically pronounceable, that she makes them part of a complex narration through building the artistic culture socially shared among the Afroamerican people, through building that cultura which was denied by the cultural hegemony of white people, by the tragedy, of the inhumanity of the slavery, of dehumanisation of Black people. In Toni Morrison’s works, the remembering becomes an act of resistance and social construction, of recollection of the African tradition of Black community to build its history and its human and emotive character of individual to whom was even denied the existence.

The construction of collective (and cultural) memory of Afroamerican community

Memory and construction of a historical and cultural identity of Afroamerican community has always been central in the work of the greatest Black American authors, since che beginning, when they, through their memoirs, tried to regain that human sense as recognised in the American Constitution and denied to the them, and show a certain rationality, a quality that the Western tradition considered as a prerequisite of human beings that white people took advantage of to promote an unreal biological superiority. A rationality they proved, in literary practices, as the absence of emotional frames to the autobiographical constructions. Those role of memory is the one that Toni Morrison recognises and uses to build her story, as she told in an interview:

«You have to stake it out and identify those who have preceded you – resummoning them acknowledging them is just one step in that process of reclamation – so that they are always there as the confirmation and the affirmation of the life that I personally have not lived but is the life of that organism to which I belong which is black in this country»[1].

It’s the same Morrison who tracks the artisti chronology of Afroamerican literature in an essay, The Site of Memory, showing how autobiographies and memoirs had the role not to my to tell a personal story or impressions on events and experiences that build the author’s character, but also the one to show authors’s own rationality and humanity, so much that these productions (and also for not making white people feel guilty and making them feel empathic, than accuse them) lack of the emotional side and the most heinous events the authors faced, taking their Ego and their thoughts off from these memoirs, which, thus, became a report on slavery and its brutality, in order to trigger a positive reaction from the Caucasian public.

Memory and personal experience are a central characteristics Afroamerican people’s literary works, and stil, today these practices are fundamental and come back into those books which are less connected to authors’ biography. But we should focus more on another side now, if we want to fathom the role of construction of collective memory in Toni Morrison’s books. The author focuses on, in the first works of Black authors, not on the personal experience, the brutalities these people faced and from which they build the imaginary and the narration of this ethic group, but on the absence of the emotional sphere in these works, what are most important side of these one for Morrison, what she considered as the starting point from which starts her research and, thus, to build her own poetics. Morrison doesn’t have the access to the interior life of these authors, who chose to eliminate it from their writings, and thus, she tried to build it, to recover it from the fragments, from the process of imagination; «[t]hese ‘memories within’ are the subsoil of [her] work. But memories and recollections won’t give [her] total access to the unwritten interior life of these people. Only the act of the imagination can help [her]»[2]. A process of recollecting from the buried memories, from the what’s not told, from that absence which construct the identity, the real story; no the experience, but the interior loves of these individual that shapes the history, «[…] and in so doing was able to imagine and to recreate cultural linkages that were identified for me by Africans who had more familiar an overt recognition»[3]. A process that Toni Morrison called “rememory”, i.e. the collection of traces, fragments, proofs to build the collective memory and to access to this one, because these fragments (such as pictures, manifestos, images, i.e. microhistory artifacts), «[…] for Morrison, possessed [their] own historical weight and [were] not assimilable to confident determination of the past. […] [H]er intention was not to integrate readers into a discourse of “their history” but to confront them with buried memories—things in which they might not even recognize themselves»[4]. This happened in Beloved, where the heinous action the mother did, Sethe, to free her children from the burden of slavery, of dehumanisation, and where the ghost of her murdered daughter represents the connection between present and past; this past, this history that comes back to haunts the living, those who are here, where the fathers’ pain hurts the sons, as in Song of Solomon, where the latter cannot give to this suffering a meaning, because they don’t remember. Past, history and memory are perceived in the acts of the presente, because it’s their result. Recollect this history and this tradition is to build a denied identity, it’s the recover of humanity. A recollection of past that becomes a literary practice, and thus a political actions, because ««[i]n so doing, Morrison’s oeuvre has fostered new understandings of the black self, bringing it to the fore and reimagining its representation as ‘a central symbol in the psychological, cultural, and political systems of the West as a whole’. […] Morrison's novels address the indefinite substance of such a cross-cultural identity and the difficulties of creating that identity in the face of racist opposition and cultural ambivalence»[5].

Oral tradition as construction of memory

The construction of a collective memory, and thus the redefinition of the historical concept of a community, also means the recollection of traditions, values and symbols of a culture determined ad oppressed and the appropriation of those practices of the hegemonic culture used as instruments of coercion and delimiting as alternative expression. In Toni Morrison, this appears as the recover of certain practices and expression belonging to the African cultura, which Afroamerican people used as the ground to build on their own sociological narration. The most important traditional practiced that Morrison uses as narrative device or as techniques of construction of her own rhetoric are the magic enemy’s and orality, where the latter brings to the former.

In an interview, Toni Morrison describes her creative process, that is the reading; she wrote her novel as they’re read, as they are oral stories, and not modern novels. The musicality, the perception and the participation of the Other, and thus of the reader, the word that has got magic power (i.e. evocative writing), the word as imaginary and instrument of communication, of sharing of meanings, are part of Morrison’s writing process. In oral civilisations (that are those societies where only oral language exists), the communicative system is based on conservation and transmission of facts, events and narrations – than on syllogism – whose purpose is to maintain the cultural processes and social foundations. Orality is, thus, the sharing of symbols, images, ideas but also definition of social characteristics, and so of unity and communion between individuals who share those proactive and answer to them (because this is the aim of communication: unite people). Another fact must be highlighted: communication of post-modern societies is called, by social sciences, as secondary orality, a phenomenon provoked from the raise of social networks, a sort of written orality, that «[…] has generated a strong group sense, for listening to spoken words forms hearers into a groups, a true audience, just as reading written or printed texts individuals in on themselves. But secondary groups immeasurably larger than those of primary oral culture – McLuhan’s ‘global village’. […] [S]econdary orality promotes spontaneity because through analytic reflection we have decided that spontaneity is a good thing. We plan our happenings carefully to be sure that they are thoroughly spontaneous»[6]. In a certain sense, Toni Morrison seems she had anticipated this communicative characteristic of post-modernity, this secondary orality, this written orality. An orality that exists in the poetics and in the narrative rhetoric of her books, thus melody, this music infiltrated into the words, into the stories, this voice that tells, the story says. Not written word, but word said. Orality that’s not only part of the writing, but it’s also part of the same narration, where the characters define themselves through their own stories, they create their own narration, they connect, in this way, the past with the present, they make their children and grandchildren partecipate to that personal memory, that, for being extraordinary, is also collective. Collective because it’s shared, because capable of building a common identity, a story that connects people and from which these individuals recognise themselves. An orality that is not only a storytelling instruments, but the recover of traditions, the catharsis of traumatic events which define the imaginary of a whole community. «Oral storytelling tradition in African American literature has been recognised by many critics as a remnant of West African oral cultures in African American tradition and has been documented as a means of cultural continuation during slavery»[7]

Second part here

Viviana Rizzo @livethinking

#Toni Morrison#memory#collective memory#identity#resistance#beloved#song of Solomon#literature#writing#article#culture#freedom#black history month#black lives matter

1 note

·

View note

Text

#neverforget

The tour of remembrance: testimony what happened

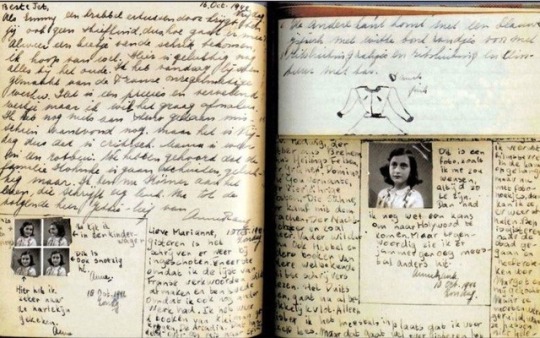

(For more pictures, visit https://spark.adobe.com/page/qv4Rkt2zw9iqD/)

We get used to say violence is inherent in man, it’s imperfect part of humanity, but what happened from 1939 to 1945 - correspondent to that extermination called Shoah or Holocaust - are beyond what’s human and painfully survivors told their testimonies which I’m subscribing for a duty I received and gave who faced this memory trip: testimony what happened.

Principle of the disaster was the ghettos: one of the first was in Cracow (in Poland) which appears like a very normal neighbourhood of any big city: buildings, shops, families who pass their days; although those walls, those buildings don’t communicate quite, serenity but a sensation of heaviness, of a melancholia perceived by soul. The Cracow ghetto, one of the first built, delimited between two natural barriers which are the Vistula river and a cliff, was the principle of the disaster. Like a prison, the Jews who lived there hadn’t chance of going out, they were prisoners without fault when they went out for a walk among their familiar streets, they must have watched back, kept their own gazes down because nazi officers, often, shot and killed men whose names and faults they didn’t know just because it was ordered and because those officers had no consciousness but only evilness.

There were also a kindergarten in the ghetto, which was, unfortunately, place for one of most great tragedies, that is the killing of innocence thus the end of hope. One night, nazi soldiers went to that kindergarten prelating all the children (their parents had left them here during they were at work) to take them to a forest where was a cliff, and there was committed on of the most violent actions: they executed them. Children’s death had been decided due to the loss could limited will of fighting, living and hoping. That place is now a playground rounded of a crag which seems wanting to fall on you. It’s surreal and monstrous and I laid my steps down there, in that quite which was echo of shoots.

The ghetto could be considered the first stop for that train will have conducted thousands of innocents to the end, to concentration camps.

Auschwitz II - Birkenau, 120 hectares of tragedy delimited with barbed wire (electrified at 40 Volt), is one of the hugest concentration and extermination camp. The deported ones were taken, as it’s known, along the railway which extends itself beyond the camp entrance, stored inside freight wagons. They showed us one: more than a wagon, it looks like a rotten wood box without openings, excite some hole in the wood. Freights like food or postal packages ��had to transport inside, instead were stored ten people without food and water. Even not to go into, you can perceive the claustrophobia sensation, the instinct of pushing for getting your own space, for breathing, for living upon the mind. The sensation of losing breath seems real.

Birkenau is impressive even just observing the entrance: immerse in a everlasting fog, it seems the light has never crossed it, the grey which hovers in that zones were the immense pain of all those women, children, men and old people had suffered and even now they still perceive it inside their heart, like Sami, Tatiana and Pietro, who too much young they had to know the whole humanity’s evilness. Birkenstock becomes the hell on earth, not as it shows itself but as appears in survivors’ stories, which seems materialise in those lands. Like Sami who had to watch his father submitted to violence of SS, who had to suffer cold, hunger, his father’s and his 14-years-old sister’s death. Like Tatiana who still child had to see her world falling apart, her childhood go away and grow too soon. Or like Pietro who saw alla his family leaving little by little, was exiled from his Country and people he knew and then came back here, lonely and with nothing.

They took off everything: goods, identities, name, dignity and who was not enough string or necessary to satisfy the sadism of those men who men are not, the nazi soldiers, was directly sent to die in gas chambers, for example old or ill people and pregnant women. Who was enough, they were sent to the Sauna, a building where the deported ones were registered.

At the end the barracks, the wooden ones where men sleeps and masonry ones where were women. 52 horses should have stayed in barracks, instead over 200 people were sleeping. Children stayed alone with a woman who cared of them, surrounded by illustrations made by adults for cheering them up during those long day without sun and during those long night without dreams on bed, cement and wooden holes. Men who were long for women, in distance, a familiar face, their own mother, wife, daughter, sister; women who were looking for their own father, husband, son, brother and they didn’t give up only to remember of being people and not beast, as they were treated.

Who stayed strong or who gave up, who repeated to itself the Divine Comedy (like Primo Levi) to remember to have dignity and consciousness or who abandoned to instinct. So many people were there that you have no idea how many they were from stamped names on history books but from memories they left, from their remains, from their dresses.

In Auschwitz I were set up shreins containing deported ones’ goods found in Canada Barrack (the mane linked to richness of that Country). This second concentration camp is different from Birkenau for the architecture (but not different for suffering). It’s smaller (it’s 12 hectares circa) and previously it was an army camp, indeed you can notice the masonry buildings height two or three floors which fill the camps, where the deported people slept. Now inside there are found goods exposition: entire room containing glasses, suitcases with belogers’ sign, shoes, dresses, hairbrushes and hair. Hundreds, thousands and every object represents an alive or dead person who stayed there. It seemed to me that from each thing the people who had them materialise, and they were too much. There were also pictures: normal people, girls and boys who smiles, families in pose and portraits of lovers. They had joyed and cried, had a story, ideas and memories and now they disappeared because someone took the right of deciding who can live or die for diseases, hunger, killed or in gas chambers.

Gas chambers whicharenhot look like showers but more like a trove, masonry parallelepipeds where you are not able to breath, where there’s no light except from those lamps or filtered by the holes where the gas were introduced, innocent looking greyish green rocks which were been heated. A corridor with grey walls collected thousand people crammed who were not able to dilate lungs, to push. It doesn’t seem a shower, as many tell, flagons are there but are not seen and they’re oxided, the lobby with rooted wood floor scared. You begin to tremble on,y standing ahead the entrance, even the smells in air is different, heavy and acid, even the sky colour, pale and colourless.

Colourless is also the crematorium room on the other side where two or three ovens rises, small and little deep and rusty, and overlying wall is still black for the smoke.

In that place we notice the violence and dangerousness of indifference, what ignorance and not denouncing could provoke, the silence and the cynism,

These trips are organized not only to know new historic facts or understand the deported people’s pain but to realise the duty of never been silent afterward violence,never been submitted by oppressive regimes and believing lies. They have passed us the torch, they have given us the responsibility of making eternal the memory, that stories, not only for us but for the best future we can achieve.

Viviana Rizzo @ilbiancodellefarfalle @livethinking

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pride and Prejudice: the relationships inJane Austen’s novel

The fable of Pride and Prejudice is built on those dynamics developed from the relationships between the characters of the novel, and only this narrative construction can cause the events. Yet, the relationships between characters are not all the same: they can be opposition relations, wherein an opponent hinders a subject’s aim towards an object (speaking in Mieke Bal’s terms), or a supporting relationship between a helper and a subject. Moreover, these relations may be developed between an individual and a power or between the former and his own background; indeed, society becomes an opposing power here, as happens with Elizabeth Bennett, or a helping power (especially with those who are able to adapt themselves to values and norms of that social system). Opposing powers are also pride and predjudice, the two concepts which are in the title of Jane Austen’s novel. Thus, in this sense, we could talk about Pride and Prejudice as a novel of relationships.

Subjects and objects in Pride and Prejudice

«The first and most important relation is between the actor who follows an aim and that aim itself. That relation may be compared to that between subject and direct objection a sentence. The first two classes of actors to be distinguished, therefore, are subject and object: actor x aspires towards goal y. X is a subject-actant, y an object-actant»[1].

Given this definition, if we should think of who the subject is in Pride and Prejudice, we would say that all the main characters of the novel are, because everyone has his or her own goal, that is the object towards every action and every choice aim; the object is here a person or a hope but, overall, a marriage.

Marriage, or better, the ambition of getting married in Pride and Predjudice is the common denominator of narratological relations established among character, is the connection between events. It’s the object to which all subjects of the novel. That was explicated by Mrs. Bennett, wishing all her daughters married «’If I can but see one of my daughters happily settled at Netherfield," said Mrs. Bennet to her husband, "and all the others equally well married, I shall have nothing to wish for’» ; indeed, one of the younger Bennett sisters, Lydia, made an extreme action to reach her goal, as we’ll see in chapter 4 vol.III, when she ran away with Mr. Wickham. Marriage is dignifying to men and the only chance allowed by society for a woman to establish theirselves of the first half of 19th century. And in these dynamics that further subject/object relations develop, always correlated to the desire of marriage. Among these also Mr. Bingley’s wish to marry Jane Bennett; the same for Miss Bingley towards Mr Darcy (but never saying it explicitly) that is in Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s designs, his aunt, who would like seeing him married to her daughter, as Lady herself told Elizabeth «’The engagement between them is of a peculiar kind. From their infancy, they have been intended for each other. It was the favourite wish of his mother, as well as of hers. While in their cradles, we planned the union’»[2].

Elizabeth, the protagonist, soon becomes the object to her father’s cousin, Mr, Collins, who proposed to her, and even to Darcy «’In vain have I struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I admire and love you’»[3].

Beyond subjects and objects: opponent/helper relations

It’s not possible to reduce the interpersonal relationships of the novel into such dialectical relation, the fable of Pride and Predjudice may get too simplified. Further kinds of relation comes into play to set in motion events: not only about wishes and desires. Mieke Bal, in Narratology, also talks about opponents and helpers[4]. The opponents are those who hinders the other characters’ path; on the contrary, the helpers are the supporters. A character can be both and, therefore, an opponent or a helper can also be a power too, – not necessarily a person.

In Pride and Prejudice opposition relations result from the clash between two subplots – i.e., the relation an anti-subject has towards an object, that could be or a same or different one from the principal –, or between two ambitions; this happens more frequently when the object is the same (e.g. Mr Darcy as object to both his aunt for her daughter and to Elizabeth on the last part of the novel, occasion that caused resentments between the two women). The most resolute and principal opponent of the story is surely Lady Catherine De Bourgh, who, by virtue of social norms, rejected the very idea of a supposed marriage between Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth.

«”While in their cradles, we planned the union: and now, at the moment when the wishes of both sisters would be accomplished in their marriage, to be prevented by a young woman of inferior birth, of no importance in the world, and wholly unallied to the family! Do you pay no regard to the wishes of his friends? To his tacit engagement with miss de bourgh? Are you lost to every feeling of propriety and delicacy? Have you not heard me say that from his earliest hours he was destined for his cousin”»[5].

From this example we can introduce the opponent as power, as a non-person. In Pride and Prejudice, the social system, built on classes, is one of the opponents that hinder a subject’s aim; marriage like those between Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy or between Mr. Bingley and Jane are rare because they’re between two people come from different costal class and norms of that system allow complaints such as Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s, or the Bingley sisters’ dislike for Jane Bennett, although subtle. Other opponent of this kind can be considered the two concepts from the title, Pride and Prejudice: Mr. Darcy’s pride, which lead him to not open to a community of a lower social class; and Elizabeth’s prejudice towards Mr. Darcy, which lead her to refuse the man’s proposal (considered offensive by the girl), and the positive one to Mr. Wickham, revealed to be a dissolute. Pride and prejudice, which impede an authentic acquaintance between the principal character of the story written by the great Jane Austen. Particular is the position of Mr. Darcy, who’s both an opponent and a helper. Opponent when he impeded the relationship between his friend mr. Charles Bingley and Jane Bennett, as he will have confirmed in his letter to Elizabeth.

«“But Bingley has great natural modesty, with a stronger dependence on my judgement than on his own. To convince him, therefore, that he had deceived himself, was no very difficult point. To persuade him against returning into Hertfordshire, when that conviction had been given, was scarcely the work of a moment. I cannot blame myself for having done this much”»[6].

He’s a helper when helps to find Lydia across London and pushing Mr. Wickham to marry the girl as to preserve the Bennetts «“He [Mr. Darcy] came to tell Mr. Gardiner that he had found out where your sister and Mr. Wickham were, and that he had seen and talked with them both; Wickham repeatedly, Lydia once.»[7]. A gesture capable of wiping away Lizzy’s prejudice and to help Mr. Darcy to reach his goal, that is to marry the protagonist of the novel. In this way other characters took part to give a support. The most importance of these were maternal Elizabeth’s uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Gardner, who, during a trip, convinced Elizabeth to see Pemberley, Darcy’s residence, where they met Mr. Darcy himself and discover a more affable and kind side of the man. «Her [Elizabeth’s] astonishment, however, was extreme, and continually was she repeating, ’Why is he [Mr. Darcy] so altered? From what can it proceed? It cannot be for me, it cannot be for my sake that his manners are thus softened’»[8]

Notes